Abstract

The nano-metal oxide-catalyzed oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) with sodium hypochlorite (NaClO) is an effective and mild technique for synthesizing 2,5-furanediformic acid (FDCA). However, the rapid and large-scale separation of nanocatalysts remains a major challenge. In this study, we developed a magnetic and recyclable copper oxide-based catalyst supported on the mechanochemically synthesized Fe3O4. Benefiting from the introduction of the Fe3O4 carrier and cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) surfactant, the CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 catalyst owns smaller CuO particle sizes, which endows it with excellent catalytic activity in the oxidation of HMF, achieving a high FDCA yield of 90.3%. Furthermore, the rapid magnetic separation of the catalyst effectively inhibits the excessive conversion of FDCA. The recovered catalyst can be reused for at least five cycles without significant loss of catalytic performance, confirming the promising application prospect of the CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 catalyst.

1. Introduction

With the depletion of fossil fuels and the worsening of environmental issues, developing catalytic technologies to produce carbon-neutral fuels and chemicals from renewable biomass has received widespread attention [,,]. As one of the top 12 value-added biomass-derived platform chemicals, 2,5-furanediformic acid (FDCA) serves as a key monomer for synthesizing various bio-based products, including polymers, fine chemicals, pharmaceuticals, etc. [,,]. Among these products, poly (ethylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate) (PEF) with excellent physical properties is identified to be a promising alternative for petroleum-based terephthalate poly (ethylene terephthalate) (PET) []. In light of environmental protection and sustainable development, large-scale synthesis and application of PEF are essential, and thus the efficient synthesis of FDCA is a fundamental prerequisite for this goal.

Currently, the selective oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF), a versatile compound derived from abundant biomass carbohydrates, is widely regarded as the most straightforward and effective approach for the industrial production of FDCA [,,]. To date, various catalytic systems have been developed and studied for HMF oxidation to FDCA, including stoichiometric oxidations (e.g., nitric acid, potassium permanganate as oxidants), homogeneous metal salt catalysis (Co/Mn/Br catalyst), heterogeneous metal or metal-oxide catalysis (e.g., Pd, Au, Ru, CuO, Co3O4 catalysts), electrocatalysis, photoelectrocatalysis, and enzyme catalysis [,,,,,,,,,,,,]. Among these approaches, HMF oxidation catalyzed by metal oxides using NaClO has attracted significant attention due to its advantages of low cost, mild reaction conditions, short reaction time, and high FDCA selectivity [,,,]. For example, Ren et al. [] employed a CuO catalyst for HMF oxidation in NaClO solution, obtaining a remarkable FDCA yield of 99.8% after reaction at 40 °C for 2 h. Liu et al. [] reported that a NiOx catalyst exhibits outstanding activity and stability in HMF oxidation, achieving a FDCA yield of 97% at 25 °C for 30 min. Jiang et al. [] demonstrated that, compared with CoOx and CuOx catalysts, the bimetallic CuCoOx catalyst affords superior performance with a FDCA yield of 96.4% at room temperature for 15 min. It is worth noting that these high-performing metal oxides are mostly nanoscale catalysts, which face difficulties in separation and regeneration during practical applications []. Therefore, developing catalysts that combine easy separation with high oxidation activity for FDCA synthesis in NaClO systems is highly desirable.

Nano-magnetite (Fe3O4) is a highly versatile material, extensively studied in different fields such as biomedicine, environmental science, and energy applications [,,]. Particularly, due to its excellent magnetic properties for separation and active surfaces for metal immobilization, Fe3O4 nanoparticles are highly suitable as catalyst carriers []. Generally, Fe3O4 nanoparticles can be synthesized through various methods, including hydrothermal, sol–gel, precipitation, extraction-pyrolytic and mechanochemical processes [,,,,]. Among these, the mechanochemical method possesses a relatively simple preparation process and avoids using solvents and generating liquid waste []. Zhao et al. [] successfully synthesized mesoporous Fe3O4 via a mechanochemical method and showed that its pore structure could be easily tuned by varying the amount of cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB). Moreover, mechanochemistry has been proven applicable for synthesizing a range of materials, such as iron oxide nanoparticles, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), covalent organic frameworks (COFs), zeolites, nitrogen-doped nanoporous carbons, etc., confirming its utility in catalytic material preparation [,,,,]. In this work, magnetic mesoporous Fe3O4 was first synthesized via a mechanochemical approach, followed by the preparation of CuO-supported catalysts using Fe3O4 support. The effects of copper oxide loading and CTAB surfactant on the physicochemical properties of the catalysts were systematically characterized, and the performance of the synthesized catalysts in HMF oxidation to FDCA was investigated in detail.

2. Results

2.1. Catalyst Characterization

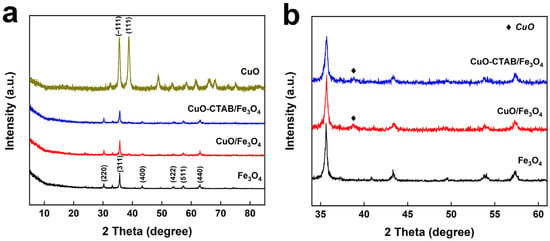

The crystalline phases of the synthesized samples were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD). As shown in Figure 1a, the pattern of Fe3O4 exhibits distinct diffraction peaks at 2θ = 30.2°, 35.6°, 43.3°, 54.7°, 57.3°, and 62.9°, which could be ascribed to the (220), (311), (400), (422), (511), and (440) planes of cubic Fe3O4 (JCPDS 72-2303), respectively []. For the synthesized CuO sample, two traditional diffraction peaks at 2θ = 35.5° and 38.7° were labeled as the (−111) and (111) lattice planes of CuO, respectively []. With the loading of copper oxide onto Fe3O4 support, a tiny diffraction peak located at 38.7° belonging to the (111) lattice planes of CuO appeared on the CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 and CuO/Fe3O4 samples, meaning that the CuO was successfully loaded on the Fe3O4 support (Figure 1b). Moreover, the CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 and CuO/Fe3O4 samples maintained the diffraction peaks of the Fe3O4 supporter, indicating that the loading process has a negligible impact on its crystalline structure.

Figure 1.

XRD patterns of the synthesized samples ((a): overall view; (b): local enlarged view).

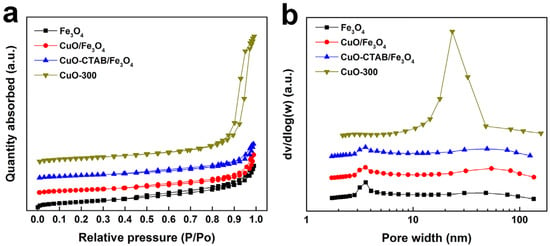

Nitrogen adsorption–desorption characterization was used to explore the pore structure of the samples. As shown in Figure 2a, the Fe3O4 sample exhibited the characteristics of type IV isotherms with a distinct hysteresis loop, which was associated with the capillary condensation of nitrogen in mesopores []. The CuO/Fe3O4 and CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 samples showed similar isotherms, preserving the mesoporous nature of the Fe3O4 supporter. In contrast, although the CuO sample also displayed a type IV isotherm, its hysteresis loop appeared at a higher relative pressure range (P/P0 = 0.8~1.0) than that of the Fe3O4 sample. The Barret-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) pore size distribution is presented in Figure 2b. The CuO sample showed a broad mesopore distribution between 10 and 50 nm, centered at 23 nm, whereas the Fe3O4-based samples exhibited a relatively narrow distribution in the 3~5 nm range. As summarized in Table 1, with the loading of copper oxide, the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) specific surface area (SBET) of CuO/Fe3O4 and CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 decreased from 53.8 m2·g−1 to 35.3 m2·g−1 and 33.1 m2·g−1, respectively. Meanwhile, the corresponding pore volume also declined, likely due to the partial blockage of mesoporous channels by copper oxide species [].

Figure 2.

Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms (a) and BJH pore size distribution (b) of the samples.

Table 1.

Physicochemical properties of the synthesized samples.

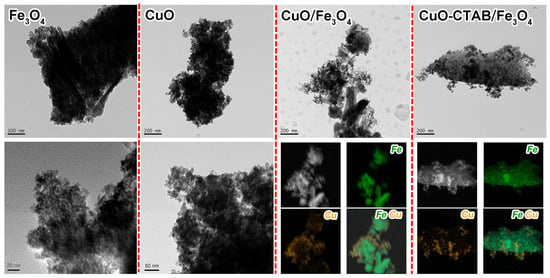

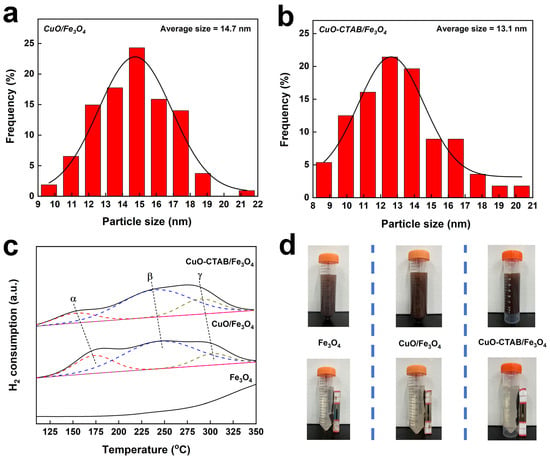

The morphology of the synthesized samples was investigated by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). As seen in Figure 3, the Fe3O4 sample revealed an irregular rod-shaped morphology. The high-resolution TEM imaging showed that these rod-shaped structures were composed of dense nanoparticles with an average diameter of 5.5 nm (Table 1, Figure S1). The CuO sample exhibited smaller irregular spherical particles, and the average diameter of these particles was 16.0 nm. It is worth noting that in both Fe3O4 and CuO samples, abundant interparticle voids can be clearly observed, which might lead to the formation of mesoporous structures. High-angle annular dark field-scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) analysis confirmed the successful loading of CuO particles onto the Fe3O4 carrier in both CuO/Fe3O4 and CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 samples. Inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) results further demonstrated that the actual CuO content in these samples closely matched the theoretical values (Table 1). Notably, the average diameters of CuO particles in CuO/Fe3O4 and CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 samples were 14.7 nm and 13.1 nm, respectively, smaller than that of the pure CuO sample (Figure 4a,b). This phenomenon indicates that the presence of Fe3O4 supporter could help to alleviate the sintering of CuO particles in the roasting process. Moreover, in the CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 sample, the addition of CTAB further improved the dispersion of active components on the carrier, contributing to an even smaller CuO particle size [].

Figure 3.

TEM and HAADF-STEM images of the samples.

Figure 4.

Copper oxide particle size distribution (a,b), H2-TPR profiles (c), and magnetic adsorption test (d) of the samples.

H2 temperature-programmed reduction (H2-TPR) was employed to analyze the reduction behavior of the samples. As exhibited in Figure 4c, the significant consumption of H2 on the Fe3O4 carrier mainly began at temperatures above 300 °C. In contrast, both CuO/Fe3O4 and CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 catalysts displayed three distinct reduction peaks in the range of 150~300 °C. The low temperature peak α (150~200 °C) was attributed to the reduction of highly dispersed copper oxide species, while peaks β (225~250 °C) and γ (275~300 °C) correspond to the reduction of larger CuO nanoparticles or copper species strongly interacting with the support [,,]. Notably, all reduction peaks of the CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 sample shifted to lower temperatures than the CuO/Fe3O4 sample. In general, the tiny CuO particles with a higher specific surface area exposed to H2 are more readily reduced than the bulk CuO particles [,]. Therefore, the observed peak shift further confirms that CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 possesses a smaller CuO particle size. Each sample was added to water and thoroughly dispersed to assess the magnetic separation performance, after which an external magnet was applied. As illustrated in Figure 4d, Fe3O4, CuO/Fe3O4, and CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 could all be efficiently separated from the solution via magnetic adsorption, demonstrating their excellent retrievability.

2.2. Catalytic Performance

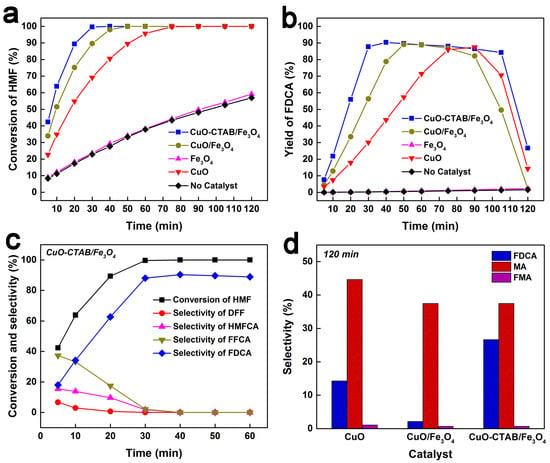

The catalytic performance of the catalysts was evaluated for the oxidation of HMF to FDCA. As shown in Figure 5a,b, in the absence of a catalyst, HMF conversion increased slowly, and no significant FDCA yield was detected throughout the reaction, suggesting that NaClO alone was insufficient in catalytic oxidation of HMF to FDCA. When Fe3O4 was used as the catalyst, both the curves of HMF conversion and FDCA yield profiles remained similar to those without any catalyst, implying a negligible catalytic role of Fe3O4 in this reaction. In contrast, the CuO catalyst enabled a gradual increase in HMF conversion to 100% within 75 min, accompanied by a slow rise in FDCA yield to 87.5% at 90 min, demonstrating its effectiveness in catalytic oxidation of HMF to FDCA. Notably, both CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 and CuO/Fe3O4 catalysts exhibited superior activity, achieving the complete conversion of HMF at 30 min and 50 min, respectively. Furthermore, the FDCA yield over CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 rapidly reached 90.3% within the first 40 min, while the maximum yield over CuO/Fe3O4 was 89.1% at 50 min, confirming the high efficiency of these catalysts in promoting HMF oxidation to FDCA. Our previous work had observed that both the HMF conversion rate and the FDCA formation rate decreased progressively as the particle size of nano copper oxide increased []. In the present work, the CuO particle size followed the order: CuO > CuO/Fe3O4 > CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4. Therefore, the superior catalytic performance of CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 can reasonably be attributed to its smallest CuO particle size. Notably, a significant decline in FDCA yield was observed during the later stage of the reaction, suggesting that FDCA was unstable in the current reaction system. Analysis of the reaction solution at 120 min (Figure 5d) revealed the presence of substantial maleic acid (MA) along with trace amounts of fumaric acid (FMA), indicating that FDCA could be further converted to MA, FMA, and other unidentified products.

Figure 5.

Catalytic performance of the catalysts in the oxidation of HMF to FDCA ((a): Conversion of HMF; (b): Yield of FDCA; (c): HMF conversion and product selectivity of the CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 catalyst; (d): Product selectivity of the catalysts at 120 min). (Reaction condition: 0.63 g HMF, 1.575 g catalyst or 0.1575 g CuO, 0.52 g NaOH, 45 mL NaClO solution, 80 mL water, 30 °C).

Figure 5c illustrates the evolution of HMF conversion and product selectivity over time using the CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 catalyst. After reaction for 5 min, the conversion of HMF reached 42.4%. The corresponding selectivities toward 2,5-diformylfuran (DFF), 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furancarboxylic acid (HMFCA), 5-formyl-2-furancarboxylic acid (FFCA), and FDCA were 6.7%, 15.4%, 37.3%, and 18.0%, respectively. Further extending the time to 30 min, the selectivities of DFF, HMFCA, and FFCA gradually declined, while FDCA selectivity increased constantly, suggesting that DFF, HMFCA, and FFCA act as intermediates in the oxidation of HMF to FDCA. Generally, the oxidation of HMF to FDCA contains two reaction routes, i.e., HMFCA pathway (route A) and DFF pathway (route B) (Scheme 1) []. The detection of both HMFCA and DFF in the products confirms the coexistence of Route A and Route B in the catalytic process. We also analyzed the product selectivity over time in the absence of catalyst. As seen in Figure S2, the trace selectivities toward FFCA and DFF were detected, and the selectivity of HMFCA was maintained around 29%. This also led to a gradual decline in the carbon balance over time (Figure S3). These phenomena indicate that although the NaClO itself can catalyze the conversion of HMF, both the oxidation activity and selectivity are not ideal. In addition, similar product and carbon balance change trends were observed on the Fe3O4 catalyst, which further confirms that the catalytic effect of Fe3O4 can be ignored. By contrast, the CuO, CuO/Fe3O4, and CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 catalysts maintained the higher carbon balance until the FDCA began to further convert, indicating that the HMF was oxidized efficiently on these catalysts.

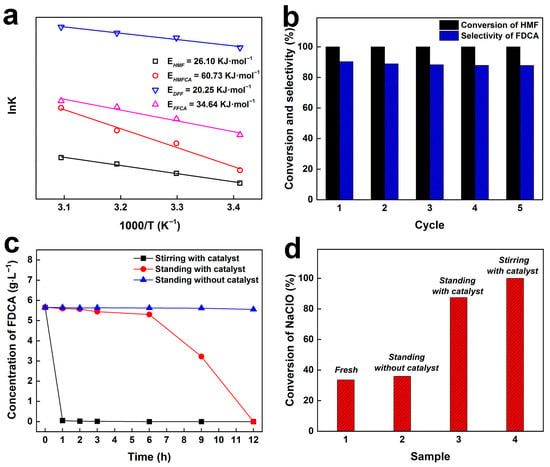

Scheme 1.

Reaction pathway of HMF to FDCA [].

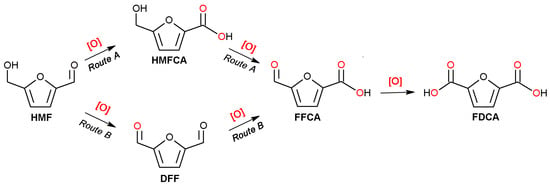

The dynamics experiment was conducted to investigate the rate-determining step on the CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 catalyst. As depicted in Figure 6a, the apparent activation energies for HMF, DFF, HMFCA, and FFCA were determined to be 26.10, 20.25, 60.73, and 34.64 kJ·mol−1, respectively, indicating that the oxidation of HMFCA is the rate-determining step. However, in terms of actual product distribution, the selectivity toward FFCA was markedly higher than that of HMFCA, which might be attributed to that a large amount of HMF was transformed into FFCA via the DFF route. Notably, the activation energies of both HMF and the intermediate species on the CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 catalyst were similar to those reported on the nano CuO catalyst []. This suggests that the intrinsic catalytic mechanism of CuO was preserved after the loading of CuO onto the Fe3O4 supporter.

Figure 6.

Apparent activation energies of different reactants on the CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 catalyst (a), stability test of CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 catalyst (b), concentration variations of FDCA (c), and conversion of NaClO (d) in the samples stored under different conditions.

Considering that reusability is also a key property of a catalyst, we tested the stability of the CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 catalyst. As demonstrated in Figure 6b, the catalyst maintained its excellent oxidation activity and FDCA selectivity even after five recycles, suggesting that the CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 catalyst has excellent stability and reusability. Given that the target product FDCA could be further transformed under the current reaction system, the influence of storage conditions on the FDCA concentration was investigated. As seen in Figure 6c, when the reaction mixture was continuously stirred at room temperature for 1 h, the FDCA concentration decreased to almost zero. In contrast, under static storage at room temperature, FDCA degradation was significantly slower within the first 6 h, though extended storage still led to a rapid decline in concentration. Notably, after magnetic separation of the catalyst, the reaction solution remained stable for up to 12 h, indicating that timely removal of the catalyst effectively suppresses the excessive transformation of FDCA. As is well known, an excess of NaClO is typically employed in the reaction system to ensure the full oxidation of HMF and its intermediates [,,]. We observed that the maximum FDCA yield over the CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 catalyst was attained at 30 °C for 40 min, while the NaClO conversion at this point was only 33.6% (Figure 6d, marked as Fresh), indicating that a substantial amount of NaClO remained in the mixture. For the obtained fresh reaction solution, after stirring or directly standing with the catalyst at room temperature for 12 h, the NaClO conversion increased to 100% and 87.4%, respectively. In contrast, the reaction solution obtained by the catalyst separation showed only a marginal rise in NaClO conversion after standing at room temperature for 12 h. These results strongly suggest that the coexistence of the catalyst and NaClO promotes excessive conversion of FDCA. Hence, replacing hard-to-separate nanocatalysts with readily separable magnetic catalysts is particularly important. To further evaluate the applicability of the catalyst, the CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 catalyst was applied for the oxidation of other furan derivatives. As listed in Table 2, the CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 catalyst exhibited outstanding performance in the oxidation of BHMF, FAL, and FFA, affording the desired products in yields of 90.5%, 82.2%, and 84.9%, respectively, indicating a promising future for the catalyst.

Table 2.

Catalytic performance of CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 catalyst in the oxidation of different furan derivatives.

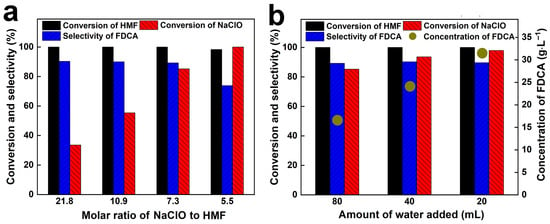

To improve process economics and address the inefficient utilization of NaClO in the current system, we increased the HMF mass to reduce the NaClO/HMF molar ratio while maintaining constant mass ratios of HMF to catalyst and NaOH. As shown in Figure 7a, with the decrease in NaClO/HMF molar ratio from 21.8 to 7.3, the complete conversion of HMF was still achieved, and the selectivity of FDCA was always higher than 89%. Meanwhile, NaClO conversion significantly increased from 33.6% to 85.2%, confirming a much more effective use of the oxidant. However, when the ratio was further reduced to 5.5, NaClO was completely consumed, but both HMF conversion and FDCA selectivity dropped to 98.3% and 73.8%, respectively. This should be ascribed to the fact that the residual HMF and intermediates cannot be further converted to FDCA without an oxidizing agent. Therefore, a slight excess of NaClO was necessary to achieve the FDCA product with a high yield.

Figure 7.

Effect of NaClO/HMF molar ratio (a) and water addition amount (b) on the performance of CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 catalyst in the oxidation of HMF to FDCA.

Notably, with the decrease in NaClO/HMF molar ratio to 7.3, the maximum concentration of FDCA also increases to 16.7 g·L−1. This higher FDCA concentration is clearly beneficial, as it helps enhance production efficiency and reduce wastewater generation. To further increase the FDCA concentration, the influence of the water addition amount on the performance of CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 catalyst was studied. As shown in Figure 7b, when the water volume decreased from 80 mL to 20 mL, HMF conversion remained at 100%, and FDCA selectivity was maintained above 89%, thereby raising the FDCA concentration to 31.6 g·L−1. Meanwhile, the conversion of NaClO also increased to 97.9% (Table 3). This might be attributed to the fact that the decrease in water amount slightly improved the temperature of the reaction liquid from 32.4 °C to 33.8 °C, which promoted the decomposition of NaClO.

Table 3.

Catalytic performance of CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 catalyst in the oxidation of HMF to FDCA.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

2,5-Diformylfuran (DFF, 98%), 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furancarboxylic acid (HMFCA, 98%), 5-formyl-2-furancarboxylic acid (FFCA, 98%), 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid (FDCA, 98%), copric chloride dihydrate (99.99%), fumaric acid (FMA, 99.5%), furfuryl alcohol (FAL, 98%), furfural (FFA, 99%), furoic acid (FA, 98%), and sodium thiosulfate solution (0.10 mol/L) were bought from Aladdin Industrial Inc. (Shanghai, China). Ethanol (99.7%), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 96%), cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB, 99%), potassium iodide (≥99.0%), and sulfuric acid (95.0–98.0%) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Maleic acid (MA, 99%) was obtained from J&K Chemicals (Beijing, China). Sodium hypochlorite solution (7.5% active chlorine basis) and ferric nitrate nonahydrate (98.5%) were purchased from Macklin Biochemical Company (Shanghai, China). 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF, 99%) and 2,5-bis(hydroxymethyl)furan (BHMF, 99%) were obtained from Zhejiang Sugar Energy Technology Co., Ltd. (Ningbo, China).

3.2. Catalyst Preparation

Mesoporous Fe3O4 was prepared using the mechanochemical method []. Initially, 4.0 g of ferric nitrate nonahydrate and 0.8 g of CTAB were successively added to a 100 mL zirconia ball mill jar equipped with zirconia balls. Subsequently, the ball mill jar was moved to a planetary ball mill and mechanochemically treated at 30 Hz for 30 min. The obtained mixtures were first collected into a crucible and then calcined in a muffle furnace at 300 °C (rate: 2 °C/min) for 2 h. Eventually, the solid product after roasting was ground to obtain the mesoporous Fe3O4 powder.

The nano copper oxide was prepared using the precipitation method. In a typical run, 9.55 g of copric chloride dihydrate and 350 mL of ethanol were added to a 2 L three-neck flask equipped with a mechanical stirrer and a cooling jacket (5 °C). Then, 4.76 g of sodium hydroxide was dissolved in 916 mL of ethanol, and the formed clear solution was dropped into the copric chloride dihydrate solution under an N2 atmosphere. After adding the sodium hydroxide solution, the mixed solution was continuously stirred for 2 h. The solid product in the reaction solution was filtered and washed with deionized water three times to remove sodium chloride. The filter cake was first dried at 50 °C for 4 h and then calcined at 300 °C (rate: 2 °C/min) for 4 h. The obtained solid product was ground into a fine powder and named CuO.

The copper-supported magnetic Fe3O4 was prepared using the CTAB-assisted precipitation method. In a typical run, 1.07 g of copric chloride dihydrate and 40 mL of ethanol were added sequentially to a 250 mL three-neck flask equipped with a cooling jacket (5 °C) and controlled N2 atmosphere. After stirring the mixture (350 rpm) to form a clear green solution, 5.0 g of Fe3O4 and 0.5 g CTAB were successively added. Subsequently, 0.52 g of sodium hydroxide was dissolved in 100 mL of ethanol. The formed clarified solution was slowly added to the three-neck flask under stirring. The mixed solution was first continuously stirred for 2 h and then filtered and washed with deionized water three times. The filter cake was placed into a crucible and dried in an oven at 50 °C for 2 h. The dry filter cake was calcined in a muffle oven at 300 °C (rate: 2 °C/min) for 2 h. The obtained solid product was ground into fine powder and named CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4. The direct copper-supported magnetic Fe3O4 was prepared using the precipitation method. Except for not adding CTAB, the overall synthesis process is the same as that of CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4. The final obtained solid powder was named CuO/Fe3O4.

3.3. Characterization Methods

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of samples were recorded on a Bruker D8 Advance (Karlsruhe, Germany) X-ray diffractometer using Cu Kα radiation. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis was performed on a FEI Tecnai F20 microscope (Hillsboro, OR, USA) equipped with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) and elemental mapping capabilities. The N2 physisorption isotherms at 77 K were measured using a Micromeritics ASAP-2020 HD88 instrument (Norcross, GA, USA). The content of copper and iron in the samples was quantified using inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) on a SPECTRO ARCOS instrument (Kleve, Germany).

The reduction behavior of the samples was tested on a Xinzhiheng XNXF560 chemical adsorption instrument (Yantai, China) via the hydrogen temperature-programmed reduction (H2-TPR) experiments. Typically, 100 mg of the sample was placed in a U-shaped quartz tube and pretreated at 200 °C for 1 h under a He flow (50 mL/min). After cooling to 50 °C in a He atmosphere, a 10% H2/Ar mixture (50 mL/min) was introduced to stabilize the baseline. Then, the temperature was raised from 50 °C to 800 °C with a rate of 10 °C/min, and the H2 consumption was detected and recorded by a TCD detector.

3.4. Catalytic Activity Test

The evaluation experiments were conducted in a 250 mL double-layer glass reactor equipped with a mechanical agitator and circulating water. In a typical run, 0.52 g of sodium hydroxide and 80 mL of deionized water were sequentially added to the reactor. Then, the temperature of the circulating water was set to 30 °C and the speed of the mechanical agitator was set to 200 rpm. After the sodium hydroxide was completely dissolved and the temperature of the mixed solution rose to 30 °C, 45 mL of sodium hypochlorite solution (stored at 5 °C), 0.63 g of HMF, and 1.575 g of catalyst (<200 mesh) were sequentially added into the mixed solution and the reaction timing was started. The reaction mixture was collected from the reactor using a pipette gun. After the catalyst was removed by filtration, the filtered solution was first cooled by an ice-water bath and then diluted with deionized water for further product analysis.

For the stability test of CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 catalyst, after reaction at 30 °C for 1 h, the catalyst was quickly separated from the reaction mixture by magnet adsorption and subsequently washed with 300 mL deionized water for three times. The recovered catalyst was first dried in an oven at 50 °C for 4 h and then thoroughly ground and sieved. The obtained catalyst (<200 mesh) was applied for the next evaluation. The performance comparison of the recycled catalysts was uniformly based on the data at 40 min of reaction.

Quantitative analysis of HMF, HMFCA, FFCA, FDCA, BHMF, FFA, FAL, and FA was performed using an Agilent Technologies 1260 II high-performance liquid chromatography instrument (Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with an ultraviolet (UV) detector and an Agilent Poroshell 120 EC-C18 column (Santa Clara, CA, USA). HMF, HMFCA, FFCA, and FDCA were detected by the wavelength of 265 nm, and BHMF was detected by the wavelength of 220 nm. A mixture of 5 mM ammonium formate aqueous solution and methanol (90:10, v/v) was employed as the mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.8 mL·min−1, and the column temperature was maintained at 40 °C. For the quantitative analysis of FFA, FAL, and FA, a mixture of 5 mM ammonium formate aqueous solution and methanol (80:20, v/v) was used as the mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.8 mL·min−1, and the column temperature was maintained at 40 °C. FAL was detected by the wavelength of 220 nm, while FFA and FA were detected by the wavelength of 265 nm.

Quantitative analysis of DFF, MA, and FMA was conducted on an Agilent 1260 HPLC Infinity instrument (Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a UV detector and an Aminex HPX-87H column (Hercules, CA, USA). A solution of 5 mM sulfuric acid aqueous solution was used as the mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.6 mL·min−1. DFF was detected by the wavelength of 285 nm with the column temperature of 60 °C. MA and FMA were detected by the wavelength of 210 nm with the column temperature of 40 °C.

The available chlorine concentration (NaClO concentration) was measured using the chemical titration method []. Typically, the hypochlorite (ClO−) in an acidic solution could be reduced by excessive potassium iodide to form the equivalent amount of iodine. Then, the iodine was titrated with the sodium thiosulfate (Na2S2O3) solution. In the titration process, starch was selected as the indicator, and the vanishing of the blue starch-iodine complex was marked as the end point of titration. In this work, the conversion of NaClO was calculated by the detected available chlorine content in the actual reaction system, and the molar ratio of NaClO to HMF was calculated by the marked available chlorine content of NaClO reagent and HMF mass.

4. Conclusions

In this study, a magnetic Fe3O4-supported copper oxide catalyst was prepared using mechanochemically synthesized Fe3O4 as the carrier. The effect of CuO loading on the physicochemical properties of the catalyst was systematically examined, and the catalytic performance was comprehensively evaluated in the oxidation of HMF to FDCA using NaClO as the oxidant. The results revealed that the introduction of an Fe3O4 carrier and CTAB surfactant could help to obtain the CuO particle with a relatively smaller size. The catalytic activity increased as the CuO particle size decreased, while the intrinsic oxidation mechanism of CuO remained intact after being supported on Fe3O4. Moreover, the coexistence of NaClO and the catalyst was found to promote the excessive transformation of FDCA, and such side reactions could be effectively suppressed by rapidly separating the catalyst from the reaction system. In addition to its high catalytic performance, the CuO-CTAB/Fe3O4 catalyst exhibited excellent magnetic separability, reusability, stability, and broad applicability. This study offers a valuable reference for the rational design of efficient and economical Cu-based catalysts for large-scale FDCA production.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/catal15121120/s1, Figure S1: Particle size distribution of the Fe3O4 (a) and CuO (b) samples; Figure S2: Catalytic performance of the NaClO and Fe3O4 catalyst in the oxidation of HMF to FDCA; Figure S3. Carbon balance of the different catalysts in the oxidation of HMF; Figure S4. HPLC chromatograms (C-18 column) of reactants and main products (a), and standard curves of different products (b: HMF; c: HMFCA; d: FFCA; e: FDCA; f: DFF); Table S1. Summary of apparent activation energies parameters; Table S2. The space time yield and specific productivity of different catalysts in the oxidation of HMF to FDCA using NaClO.

Author Contributions

P.Y.: methodology, experimental, testing, data curation; H.H.: conceptualization, data curation, writing—original draft preparation; Y.Y., Q.F. and G.L. (Guowen Lu): methodology, formal analysis; C.C., S.I.E.-H., G.L. (Guojun Lan) and J.Z.: writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LY24B060004), Ningbo Municipal Bureau of Science (2019B10096, 2023J359), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22072170, U23A20125), the Advanced Materials-National Science and Technology Major Project (2025ZD0614502) and the President Foundation of Ningbo Institute of Materials Technology and Engineering.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Corma, A.; Iborra, S.; Velty, A. Chemical routes for the transformation of biomass into chemicals. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 2411–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mika, L.T.; Cséfalvay, E.; Németh, A. Catalytic conversion of carbohydrates to initial platform chemicals: Chemistry and Sustainability. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 505–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, J.; Martínez-Salazar, I.; Maireles-Torres, P.; Alonso, D.M.; Mariscal, R.; Granados, M.L. Advances in catalytic routes for the production of carboxylic acids from biomass: A step forward for sustainable polymers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 5704–5771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozell, J.J.; Petersen, G.R. Technology development for the production of biobased products from biorefinery carbohydrates-the US Department of Energy’s “Top 10” revisited. Green. Chem. 2010, 12, 539–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, R.A. Green and sustainable manufacture of chemicals from biomass: State of the art. Green. Chem. 2014, 16, 950–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chícharo, B.; Fadlallah, S.; Moraru, D.; Darney, L.; Sangermano, M.; Aricòa, F.; Allais, F. Bio-based epoxy thermosets from 2,5-furan dicarboxylic acid derivates with tunable chain length. Polymer 2025, 336, 128880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, S.K.; Leisen, J.E.; Kraftschik, B.E.; Mubarak, C.R.; Kriegel, R.M.; Koros, W.J. Chain mobility, thermal, and mechanical properties of poly(ethylene furanoate) compared to poly(ethylene terephthalate). Macromolecules 2014, 47, 1383–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.H.; Sun, G.H.; Xia, H.A. Aerobic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to high-yield 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furancarboxylic acid by poly(vinylpyrrolidone)-capped Ag nanoparticle catalysts. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 6696–6706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totaro, G.; Sisti, L.; Marchese, P.; Colonna, M.; Romano, A.; Gioia, C.; Vannini, M.; Celli, A. Current advances in the sustainable conversion of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural into 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid. ChemSusChem 2022, 15, e202200501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Cibin, G.; Walton, R.I. Selective oxidation of biomass-derived 5-hydroxymethylfurfural catalyzed by an iron-grafted metal-organic framework with a sustainably sourced ligand. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 5575–5585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partenheimer, W.; Grushin, V.V. Synthesis of 2,5-diformylfuran and furan-2,5-dicarboxylic acid by catalytic air-oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. Unexpectedly selective aerobic oxidation of benzyl alcohol to benzaldehyde with metal/bromide catalysts. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2001, 343, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.E.; Houk, L.R.; Tamargo, E.C.; Datye, A.K.; Davis, R.J. Oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural over supported Pt, Pd and Au catalysts. Catal. Today 2011, 160, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, B.; Gupta, D.; Abu-Omar, M.M.; Modak, A.; Bhaumik, A. Porphyrin-based porous organic polymer-supported iron(III) catalyst for efficient aerobic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethyl-furfural into 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid. J. Catal. 2013, 299, 316–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerdi, F.; Rass, H.A.; Pinel, C.; Besson, M.; Peru, G.; Leger, B.; Rio, S.; Monflier, E.; Ponchel, A. Evaluation of surface properties and pore structure of carbon on the activity of supported Ru catalysts in the aqueous-phase aerobic oxidation of HMF to FDCA. Appl. Catal. A-Gen. 2015, 506, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, X.B.; Venkitasubramanian, P.; Busch, D.H.; Subramaniam, B. Optimization of Co/Mn/Br-catalyzed oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to enhance 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid yield and minimize substrate burning. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 3659–3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.H.; Huber, G.W. Catalytic oxidation of carbohydrates into organic acids and furan chemicals. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 1351–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Sun, X.Z.; Zheng, Z.H.; Zhang, L. Nanoscale center-hollowed hexagon MnCo2O4 spinel catalyzed aerobic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid. Catal. Commun. 2018, 113, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.B.; Cheng, Y.W.; Ban, H.; Zhang, Y.D.; Zheng, L.P.; Wang, L.J.; Li, X. Liquid-phase aerobic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid over Co/Mn/Br catalyst. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 17076–17084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Zhang, W.Z.; Li, Q.F.; Xia, H.A. Visible-light-driven photocatalytic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid over plasmonic Au/ZnO catalyst. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 8778–8787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.Z.; Liu, H.; Tang, X.; Zeng, X.H.; Sun, Y.; Ke, X.X.; Li, T.Y.; Fang, H.Y.; Lin, L. Efficient synthesis of 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid from biomass-derived 5-hydroxymethylfurfural in 1,4-dioxane/H2O mixture. Appl. Catal A-Gen. 2022, 630, 118463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, M.; Mariyaselvakumar, M.; Tothadi, S.; Panda, A.B.; Srinivasan, K.; Konwar, L.J. Base free HMF oxidation over Ru-MnO2 catalysts revisited: Evidence of Mn leaching to Mn-FDCA complexation and its implications on catalyst performance. Mol. Catal. 2024, 554, 113811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Wang, Q.G.; Wang, J.G.; Yu, X.; Zhang, J.; Chen, C.L. Co@NC Chainmail nanowires for thermo- and electrocatalytic oxidation of 2,5-bis(hydroxymethyl)furan to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid. ChemSusChem 2025, 18, e202401422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Hu, H.L.; Yang, Y.; Lu, G.W.; Fang, Q.Q.; Lan, G.J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, C.L. Efficient oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid by nanocopper oxide catalysts. ChemPlusChem 2025, 90, e202500181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Song, K.H.; Li, Z.H.; Wang, Q.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.X.; Li, D.B.; Kim, C.K. Activation of formyl C-H and hydroxyl O-H bonds in HMF by the CuO (111) and Co3O4(110) surfaces: A DFT study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 456, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, W.L.; Zuo, M.; Tang, X.; Zeng, X.H.; Sun, Y.; Lei, T.Z.; Fang, H.Y.; Li, T.Y.; Lin, L. Facile and efficient two-step formation of a renewable monomer 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid from carbohydrates over the NiOx catalyst. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 4895–4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Wang, D.J.; Deng, X.L.; Gao, Y.X.; Wang, W.Z.; Ge, T.J.; Zhao, C.K.; Sun, Y. Oxygen vacancy boosted oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2, 5-furandicarboxylic acid over CuCoOx. Mol. Catal. 2024, 556, 113917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.Y.; Ye, Y.Y.; Ye, J.M.; Gao, T.; Wang, D.H.; Chen, G.; Song, Z.J. Recent advances of magnetite (Fe3O4)-based magnetic materials in catalytic applications. Magnetochemistry 2023, 9, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawande, M.B.; Branco, P.S.; Varm, R.S. Nano-magnetite (Fe3O4) as a support for recyclable catalysts in the development of sustainable methodologies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 3371–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, M.D.; Tran, H.V.; Xu, S.J.; Lee, T.R. Fe3O4 Nanoparticles: Structures, synthesis, magnetic properties, surface functionalization, and emerging applications. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahdar, A.; Taboada, P.; Aliahmad, M.; Hajinezhad, M.R.; Sadeghfar, F. Iron oxide nanoparticles: Synthesis, physical characterization, and intraperitoneal biochemical studies in Rattus norvegicus. J. Mol. Struct. 2018, 1173, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajpu, S.; Pittman Jr, C.U.; Mohan, D. Magnetic magnetite (Fe3O4) nanoparticle synthesis and applications for lead (Pb2+) and chromium (Cr6+) removal from water. J. Colloid. Interf. Sci. 2016, 468, 334–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daou, T.J.; Pourroy, G.; Bégin-Colin, S.; Grenèche, J.M.; Ulhaq-Bouillet, C.; Legaré, P.; Bernhardt, P.; Leuvrey, C.; Rogez, G. Hydrothermal synthesis of monodisperse magnetite nanoparticles. Chem. Mater. 2006, 18, 4399–4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yang, H.B.; Fu, W.Y.; Du, K.; Sui, Y.M.; Chen, J.J.; Zeng, Y.; Li, M.H.; Zou, G.T. Preparation and magnetic properties of magnetite nanoparticles by sol-gel method. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2007, 309, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.Y.; Zhang, B.Z.; Chen, D.; Li, Y.; Feng, C.D.; Du, W.A. Mechanochemistry strategy in metal/Fe3O4 with high stability for superior chemoselective catalysis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 66219–66229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serga, V.; Burve, R.; Maiorov, M.; Krumina, A.; Skaudžius, R.; Zarkov, A.; Kareiva, A.; Popov, A.I. Impact of gadolinium on the structure and magnetic properties of nanocrystalline powders of iron oxides produced by the extraction-pyrolytic method. Materials 2020, 13, 4147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friščić, T.; Mottillo, C.; Titi, H.M. Mechanochemistry for synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 1018–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.H.; Shu, Y.; Zhang, P.F. Solid-state CTAB-assisted synthesis of mesoporous Fe3O4 and Au@Fe3O4 by mechanochemistry. Chin. J. Catal. 2019, 40, 1078–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimakow, M.; Klobes, P.; Rademann, K.; Emmerling, F. Characterization of mechanochemically synthesized MOFs. Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 2012, 154, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzehpoor, E.; Effaty, F.; Borchers, T.H.; Stein, R.S.; Wahrhaftig-Lewis, A.; Ottenwaelder, X.; Friščić, T.; Perepichka, D.F. Mechanochemical synthesis of boroxine-linked covalent organic frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202404539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, H.; Ochoa-Hernández, C.; Nürenberg, E.; Kang, L.Q.; Wang, F.R.; Weidenthaler, C.; Schmidt, W.; Schüth, F. Insights into the mechanochemical synthesis of Sn-β: Solid-state metal incorporation in beta zeolite. Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 2020, 309, 110566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneidermann, C.; Jäckel, N.; Oswald, S.; Giebeler, L.; Presser, V.; Borchardt, L. Solvent-free mechanochemical synthesis of nitrogen-doped nanoporous carbon for electrochemical energy storage. ChemSusChem 2017, 10, 2416–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Yue, Y.H.; Miao, C.X.; Hua, W.M.; Gao, Z. Mesoporous silica-encapsulated Cu nanoparticles with enhanced performance for ethanol dehydrogenation to acetaldehyde. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 1401–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.K.; Sun, J.M.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.Q.; Wan, H.Y.; Hu, J.Z.; Wang, Y.; Peden, C.H.F.; Nie, Z.M. Solvent evaporation assisted preparation of oriented nanocrystalline mesoporous MFI zeolites. ACS Catal. 2011, 1, 682–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.L.; Xue, T.T.; Zhang, Z.X.; Gan, J.; Chen, L.Q.; Zhang, J.; Qu, F.Z.; Cai, W.J.; Wang, L. Direct conversion of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to furanic diether by copper-loaded hierarchically structured ZSM-5 catalyst in a fixed-bed Reactor. ChemCatChem 2021, 13, 3461–3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Jia, X.H.; Liu, R.; Liu, F.F.; Zhang, H.; Hou, D.; Wang, L.; Luo, Y.K.; Huang, B.C.; Huang, H.; et al. CTAB-Assisted, controlled preparation of a CeZrOx/CuSAPO-34 catalyst and its performance for the synergistic removal of NOx and toluene from flue gas. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 118561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witoon, T.; Chalorngtham, J.; Dumrongbunditkul, P.; Chareonpanich, M.; Limtrakul, J. CO2 hydrogenation to methanol over Cu/ZrO2 catalysts: Effects of zirconia phases. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 293, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.X.; Huang, H.J.; Kong, L.X.; Ma, X.B. Effect of calcination temperature on the Cu-ZrO2 interfacial structure and its catalytic behavior in the hydrogenation of dimethyl oxalate. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2022, 12, 6782–6794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.G.; Han, X.; Zhang, F.; Sun, Z.Y.; Chai, R.Y.; Xu, F.; Du, S.G.; Jiao, X.L.; Chen, D.R.; Zhang, J. Synergistic role of Cu0 and acidic sites in Cu/Al2O3 catalysts for enhanced furfural hydrogenation to furfuryl alcohol. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 522, 167587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, F.F.; Zhu, W.; Xiao, G.M. Promoting effect of zirconium oxide on Cu-Al2O3 catalyst for the hydrogenolysis of glycerol to 1,2-propanediol. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 4889–4900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.X.; Hu, H.L.; Zhou, H.; Li, G.Z.; Chen, C.L.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Hu, Y.P.; Zhang, Y.J.; Wang, L. The effect of potassium on Cu/Al2O3 catalysts for the hydrogenation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-bis(hydroxymethyl)furan in a fixed-bed reactor. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2018, 8, 6091–6099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid, M.; Zhao, X.B.; Liu, D.H. Production of 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid (FDCA) from 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF): Recent progress focusing on the chemical-catalytic routes. Green. Chem. 2018, 20, 5427–5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).