Investigation of the Synergistic Aromatization Effect During the Co-Pyrolysis of Wheat Straw and Polystyrene Modulated by an HZSM-5 Catalyst

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

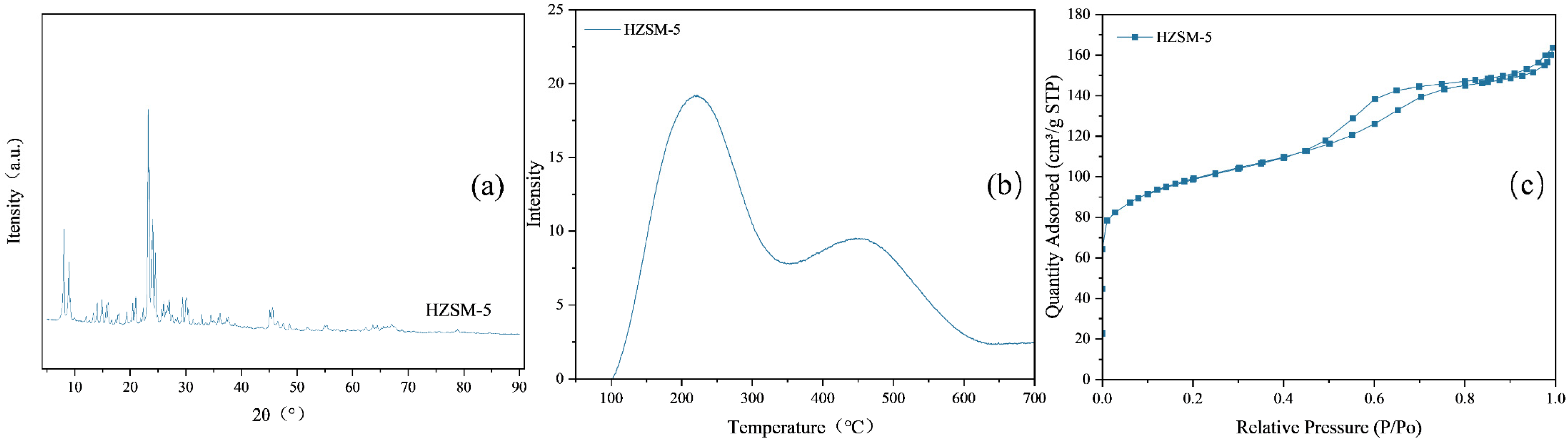

2.1. Characterization of the Catalyst

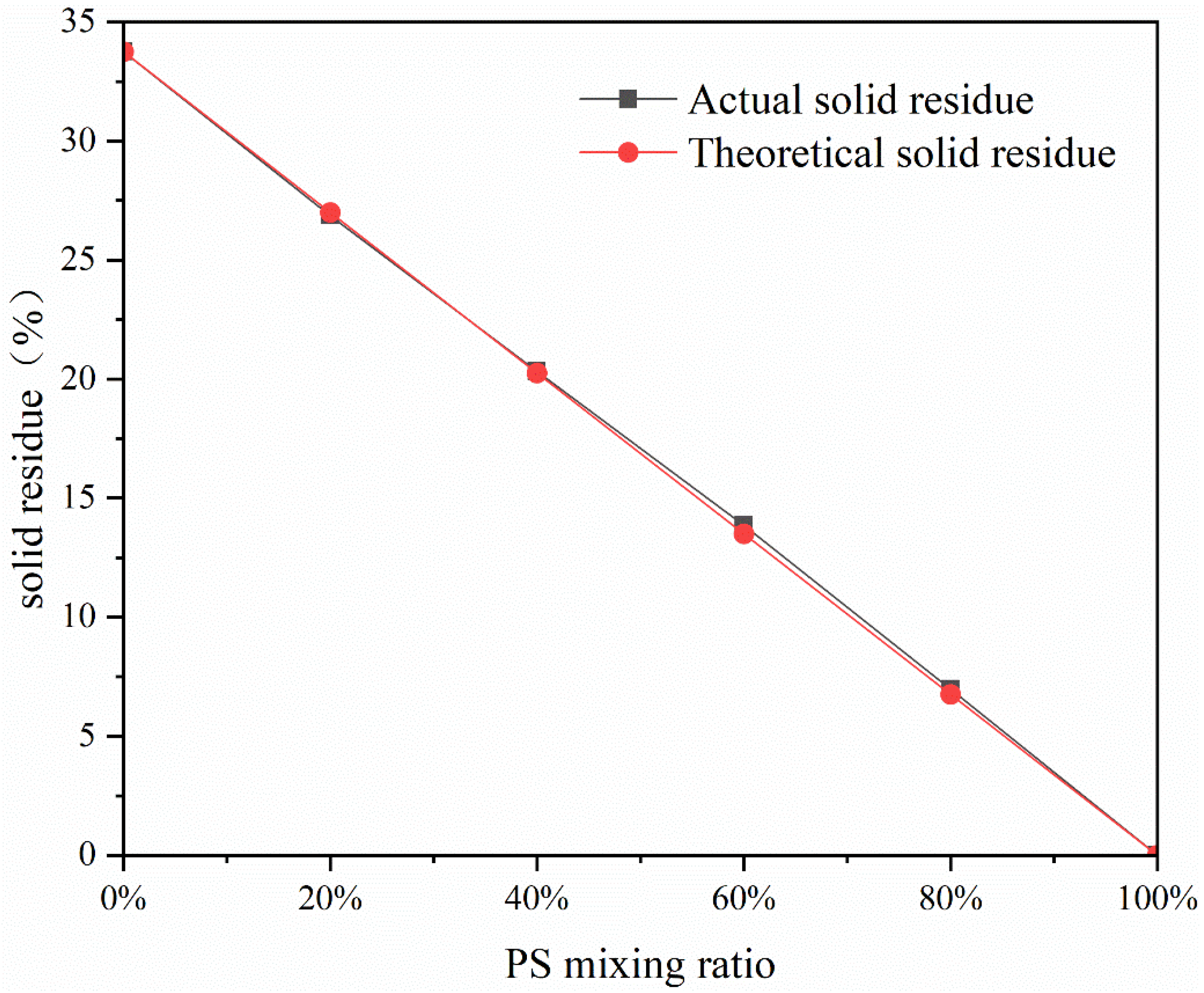

2.2. Solid Residue Analysis

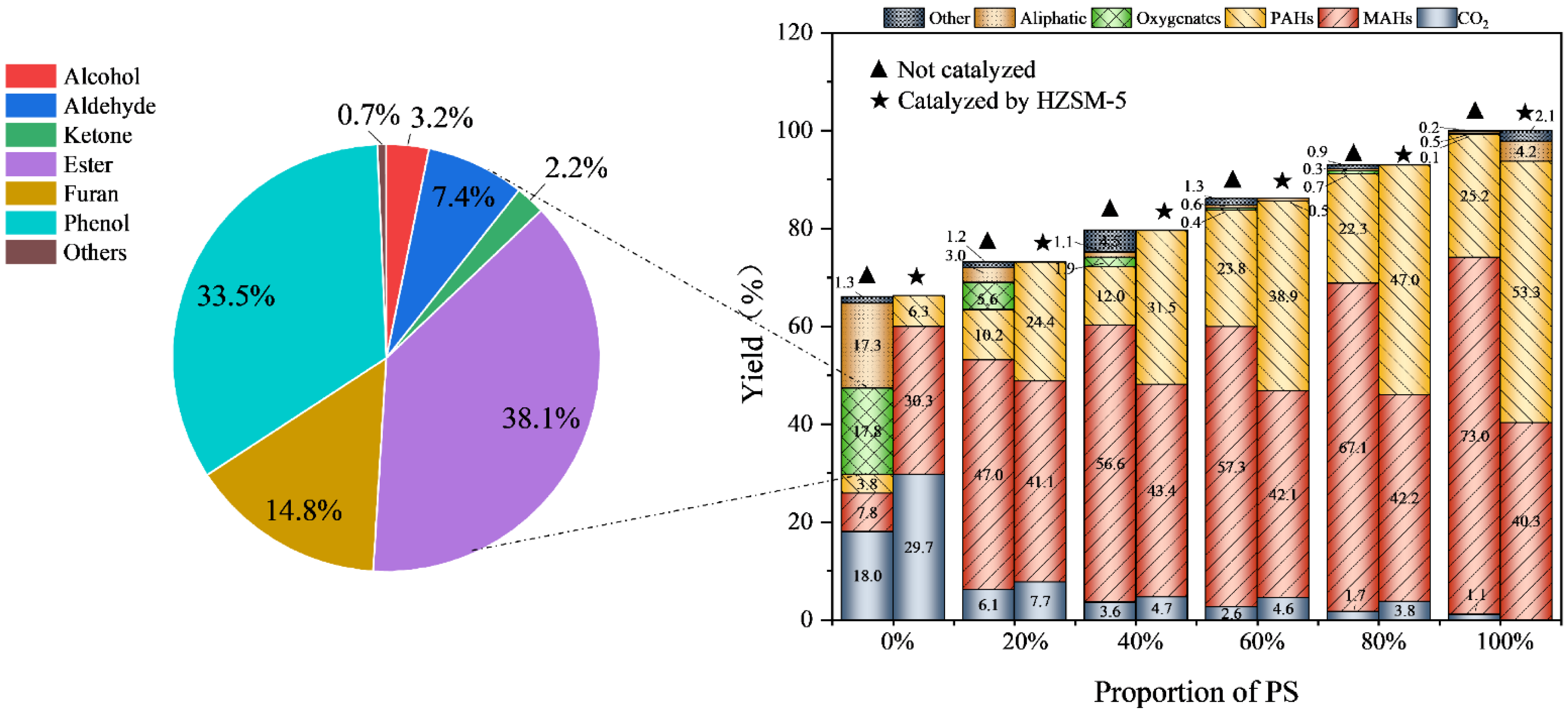

2.3. Effect of HZSM-5 on Product Distribution

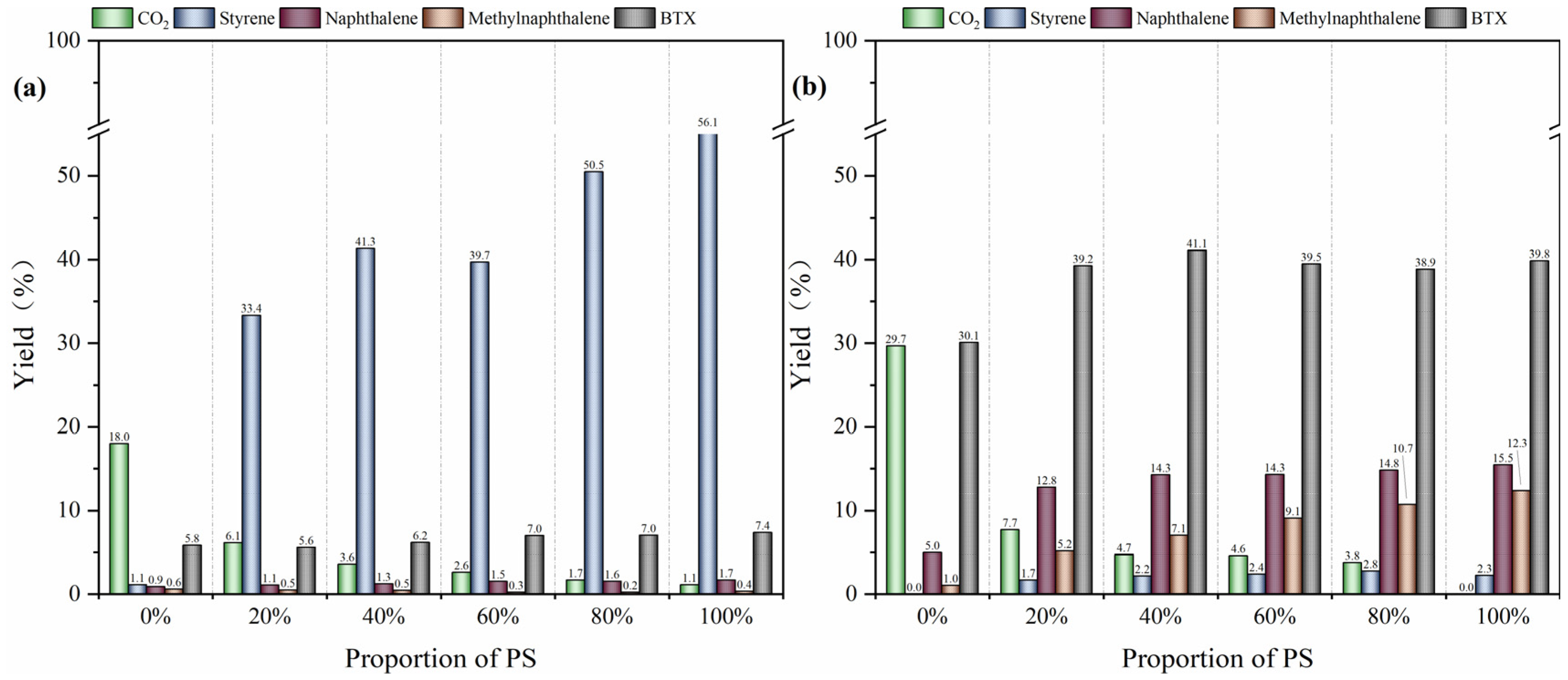

2.4. Analysis of the Synergistic Effect of HZSM-5 on Products

2.5. Effect of Catalytic Temperature on Product Distribution

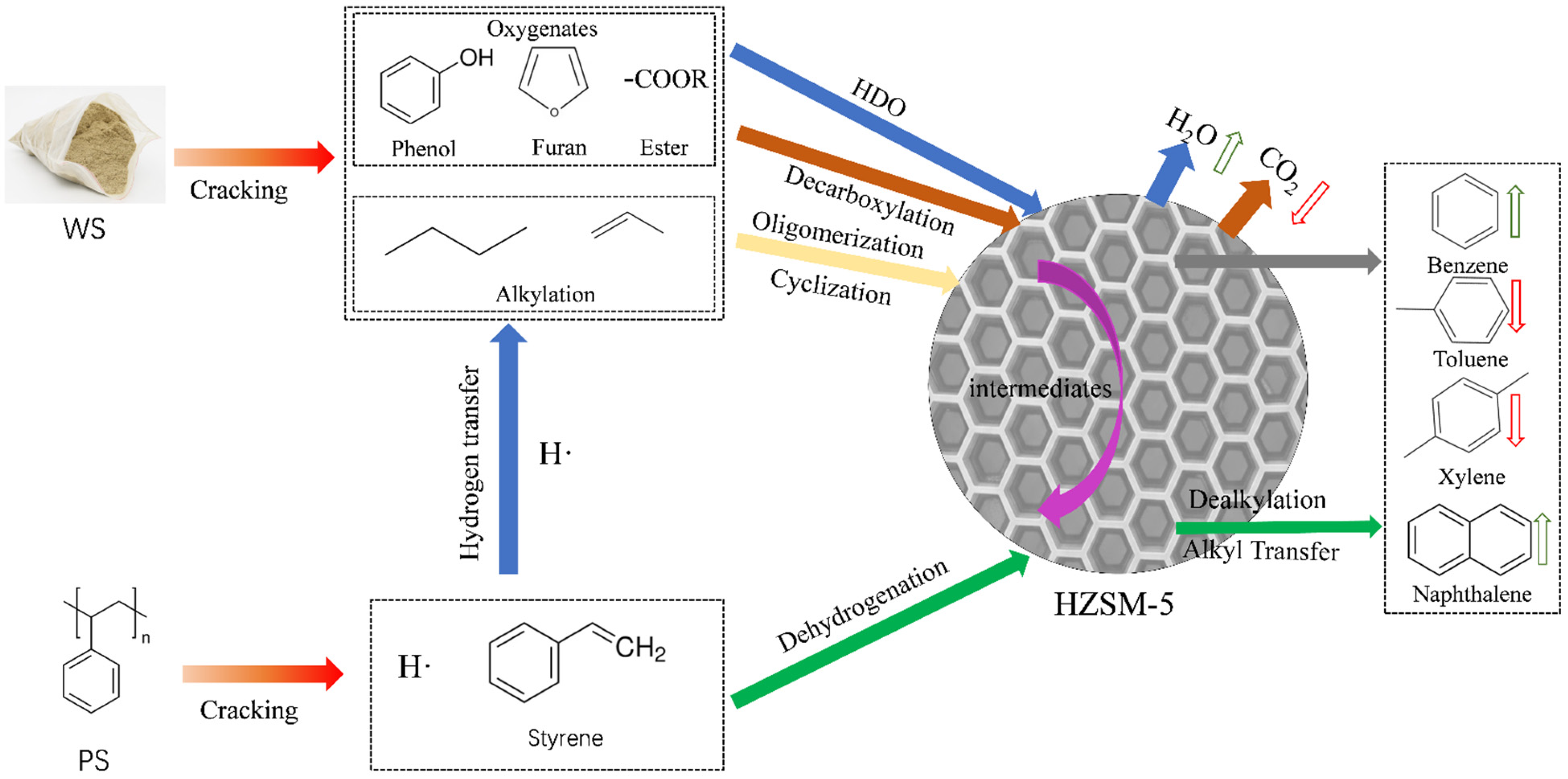

2.6. Derivation of Reaction Pathways

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Experimental Materials

3.2. Catalyst Preparation and Characterization

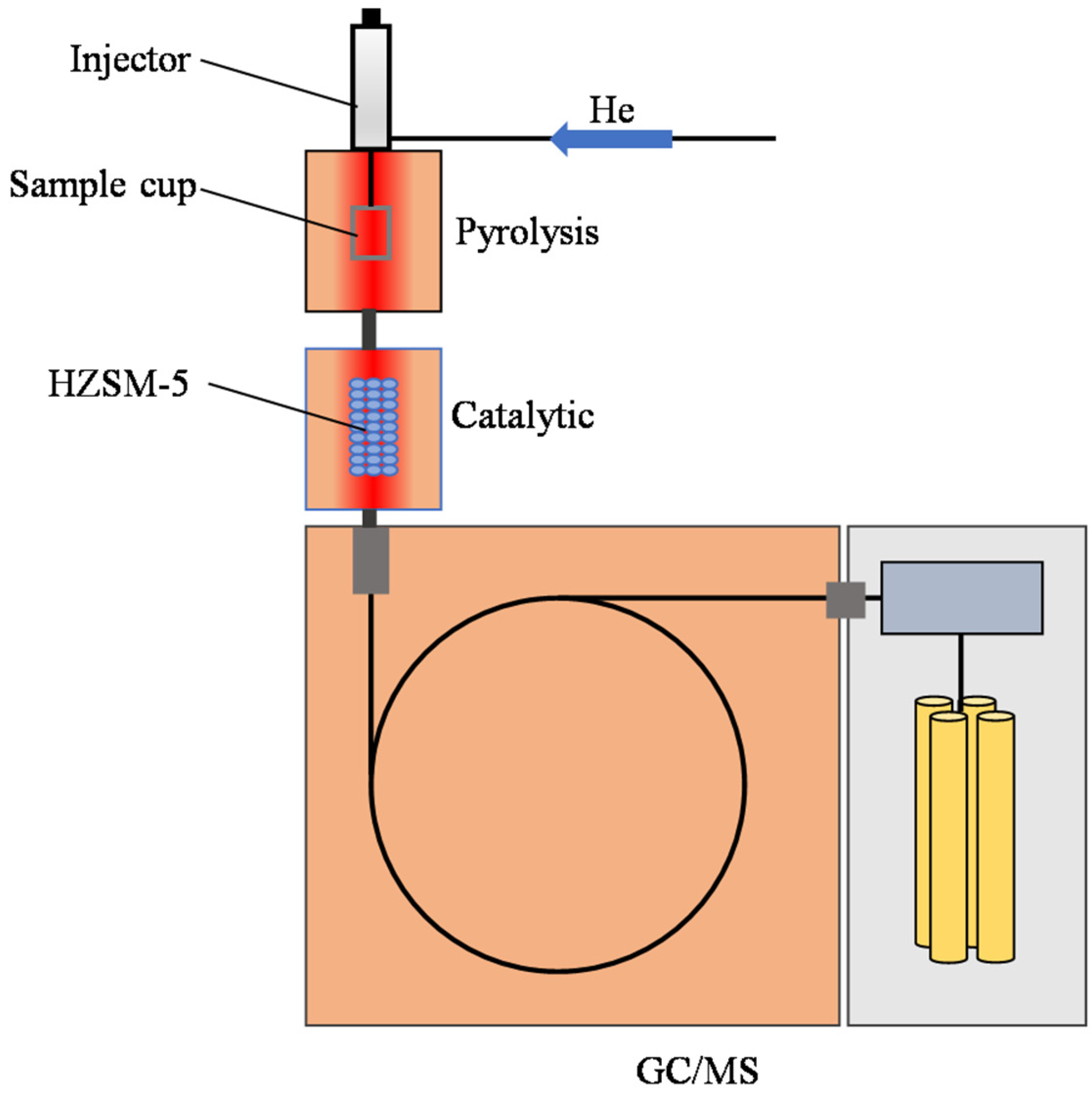

3.3. Catalytic Experimental Apparatus

3.4. Product Analysis Method

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Naqvi, S.R.; Jamshaid, S.; Naqvi, M.; Farooq, W.; Niazi, M.B.K.; Aman, Z.; Zubair, M.; Ali, M.; Shahbaz, M.; Inayat, A.; et al. Potential of Biomass for Bioenergy in Pakistan Based on Present Case and Future Perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 1247–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, G.W.; Iborra, S.; Corma, A. Synthesis of Transportation Fuels from Biomass: Chemistry, Catalysts, and Engineering. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 4044–4098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Energy Outlook 2024—Analysis. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2024 (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Cui, B.; Rong, H.; Luo, S.; Chen, Z.; Hu, M.; Yan, W.; He, P.; Guo, D. Pyrolysis Characteristics of Camellia Oleifera Seeds Residue in Different Heating Regimes: Products, Kinetics, and Mechanism. Renew. Energy 2025, 238, 121972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fertilization, feed, energyization, binder, raw materials. China forms a new pattern of straw multi-use. Available online: https://www.agri.cn/zx/nyyw/202405/t20240514_8632898.htm (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Kumar, A.; Jamro, I.A.; Rong, H.; Kumari, L.; Laghari, A.A.; Cui, B.; Aborisade, M.A.; Oba, B.T.; Nkinahamira, F.; Ndagi-jimana, P.; et al. Assessing Bioenergy Prospects of Algal Biomass and Yard Waste Using an In-tegrated Hydrothermal Carbonization and Pyrolysis (HTC-PY): A Detailed Emission-to-Ash Characterization via Diverse Hyphenated Analytical Techniques and Modelling Strategies. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 492, 152335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plastics—The Fast Facts 2024 • Plastics Europe. Available online: https://plasticseurope.org/knowledge-hub/plastics-the-fast-facts-2024/ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Jambeck, J.R.; Geyer, R.; Wilcox, C.; Siegler, T.R.; Perryman, M.; Andrady, A.; Narayan, R.; Law, K.L. Plastic Waste Inputs from Land into the Ocean. Science 2015, 347, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, M.; Arp, H.P.H.; Tekman, M.B.; Jahnke, A. The Global Threat from Plastic Pollution. Science 2021, 373, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, F.; Ullah, H.; Zada, N.; Shahab, A. A Review on Catalytic Co-Pyrolysis of Biomass and Plastics Waste as a Thermochemical Conversion to Produce Valuable Products. Energies 2023, 16, 5403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, H.; Lim, J.K.; Hameed, B.H. Recent Progress on Biomass Co-Pyrolysis Conversion into High-Quality Bio-Oil. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 221, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yang, J.; Wu, G.; Gao, W.; Silva Lora, E.E.; Isa, Y.M.; Subramanian, K.A.; Kozlov, A.; Zhang, S.; Huang, Y. Benzene, Toluene, and Xylene (BTX) Production from Catalytic Fast Pyrolysis of Biomass: A Review. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 11700–11718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, B.; Takács, M.; Domján, A.; Barta-Rajnai, E.; Valyon, J.; Hancsók, J.; Barthos, R. Liquid Phase Pyrolysis of Wheat Straw and Poplar in Hexadecane Solvent. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2019, 137, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao Thi, H.; Van Aelst, K.; Van Den Bosch, S.; Katahira, R.; Beckham, G.T.; Sels, B.F.; Van Geem, K.M. Identification and Quantification of Lignin Monomers and Oligomers from Reductive Catalytic Fractionation of Pine Wood with GC × GC—FID/MS. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonsky, S.T.; Hogan, N.R.; Toraman, H.E. Effect of Pyrolysis Operating Conditions on the Catalytic Co-pyrolysis of Low-density Polyethylene and Polyethylene Terephthalate with Zeolite Catalysts. AIChE J. 2024, 70, e18548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Dai, Y.; Yang, H.; Xiong, Q.; Wang, K.; Zhou, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, S. A Review of Recent Advances in Biomass Pyrolysis. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 15557–15578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gu, J.; Shan, R.; Yuan, H.; Chen, Y. Advances in Thermochemical Valorization of Biomass towards Carbon Neutrality. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 212, 107905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Wu, S.; Lou, R.; Lv, G. Analysis of Wheat Straw Lignin by Thermogravimetry and Pyrolysis–Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2010, 87, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, Z.C. Essential Quality Attributes of Tangible Bio-Oils from Catalytic Pyrolysis of Lignocellulosic Biomass. Chem. Rec. 2019, 19, 2044–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Wang, X.; Zhu, Z.; Kumar, R.; Nana Amaniampong, P.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Z.-T. Synergetic Effects in the Co-Pyrolysis of Lignocellulosic Biomass and Plastic Waste for Renewable Fuels and Chemicals. Fuel 2023, 353, 129210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvilla, J.N.V.; Ofrasio, B.I.G.; Rollon, A.P.; Manegdeg, F.G.; Abarca, R.R.M.; De Luna, M.D.G. Synergistic Co-Pyrolysıs of Polyolefin Plastics with Wood and Agricultural Wastes for Biofuel Production. Appl. Energy 2020, 279, 115668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, N.; Wang, Z.; Chen, G.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, H.; Wang, Q.; Guo, S.; Su, F.; You, Z.; Yang, S.; et al. Co-Pyrolysis Kinetic Characteristics of Wheat Straw and Hydrogen Rich Plastics Based on TG-FTIR and Py-GC/MS. Energy 2024, 312, 133683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, C.A.; Boateng, A.A. Catalytic Pyrolysis-GC/MS of Lignin from Several Sources. Fuel Process. Technol. 2010, 91, 1446–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, B.; Tao, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Chu, H. Research Progress in the Preparation of High-Quality Liquid Fuels and Chemicals by Catalytic Pyrolysis of Biomass: A Review. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 261, 115647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.; Bi, D.; Qin, Z.; He, Z.; Huang, J.; Liu, S. Co-Pyrolysis of Wheat Straw with Polyester-Based Polyurethane for Nitrogenous Compounds: Pyrolysis Kinetic Properties and Synergistic Effects. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2024, 182, 106662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wu, S.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, R. Cellulose-Lignin Interactions during Catalytic Pyrolysis with Different Zeolite Catalysts. Fuel Process. Technol. 2018, 179, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtkamp, M.; Renner, M.; Matthiesen, K.; Wald, M.; Luinstra, G.A.; Biessey, P. Robust Downstream Technologies in Polystyrene Waste Pyrolysis: Design and Prospective Life-Cycle Assessment of Pyrolysis Oil Reintegration Pathways. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 205, 107558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qian, J.; Wang, J. Pyrolysis of Polystyrene Waste in a Fluidized-Bed Reactor to Obtain Styrene Monomer and Gasoline Fraction. Fuel Process. Technol. 2000, 63, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Zhu, R.; Zhu, G.; Wang, J.; Cheng, Y. Hierarchical HZSM-5 Catalysts Enhancing Monocyclic Aromatics Selectivity in Co-Pyrolysis of Wheat Straw and Polyethylene Mixture. Renew. Energy 2024, 233, 121150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Wang, Z.; Chen, G.; Chen, Y.; Wu, M.; Zhang, M.; Li, Z.; Yang, S.; Lei, T. Catalytic Co-Pyrolysis of Poplar Tree and Polystyrene with HZSM-5 and Fe/HZSM-5 for Production of Light Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Energy 2024, 298, 131433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter Type | Data |

|---|---|

| Weak Acid Peak Temperature (°C) | 219 |

| Strong Acid Peak Temperature (°C) | 431 |

| Weak Acidity (mmol/g) | 0.526 |

| Strong Acidity (mmol/g) | 0.358 |

| Total Acidity (mmol/g) | 0.884 |

| Weak/Strong Acid Ratio | 1.47 |

| Catalyst | SBET m2/g | Smicro m2/g | Smeso m2/g | Vmicro cm3/g | Vmeso cm3/g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HZSM-5 | 330.55 | 169.33 | 132.52 | 0.08 | 0.15 |

| Products | 20% PS | 40% PS | 60% PS | 80% PS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAHs | + | + | + | + |

| PAHs | + | − | + | + |

| Oxygcnatcs | − | − | − | − |

| Aliphatic | − | − | − | − |

| CO2 | − | − | − | − |

| Benzene | − | − | − | − |

| Toluene | + | + | + | + |

| Xylene | − | − | − | − |

| Styrene | + | + | + | + |

| Naphthalene | + | + | + | + |

| Methylnaphthalene | − | − | − | − |

| BTX | − | − | + | − |

| Products | 20% PS | 40% PS | 60% PS | 80% PS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAHs | − | − | − | − |

| PAHs | + | + | + | + |

| Oxygcnatcs | \ | \ | \ | + |

| Aliphatic | − | − | − | − |

| CO2 | − | − | − | − |

| Benzene | + | + | + | + |

| Toluene | − | − | − | − |

| Xylene | − | − | − | − |

| Styrene | + | + | + | + |

| Naphthalene | + | + | + | + |

| Methylnaphthalene | + | + | + | + |

| BTX | + | + | + | + |

| Sample | WS | PS |

|---|---|---|

| Proximate analyses (wt%) | ||

| Moisture | 8.2 | 0.1 |

| Ash | 14.2 | 0 |

| Volatile | 58.1 | 99.9 |

| Fixed Carbon | 19.5 | 0 |

| Ultimate analyses (wt%) | ||

| C | 25.52 | 92.11 |

| H | 2.78 | 6.85 |

| O | 55.94 | 0.32 |

| N | 0.92 | 0.07 |

| S | 0.64 | 0.65 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cai, Z.; Ye, Y.; Kumar, A.; Rong, H.; Cui, B.; Zhang, F.; Guo, D. Investigation of the Synergistic Aromatization Effect During the Co-Pyrolysis of Wheat Straw and Polystyrene Modulated by an HZSM-5 Catalyst. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1121. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121121

Cai Z, Ye Y, Kumar A, Rong H, Cui B, Zhang F, Guo D. Investigation of the Synergistic Aromatization Effect During the Co-Pyrolysis of Wheat Straw and Polystyrene Modulated by an HZSM-5 Catalyst. Catalysts. 2025; 15(12):1121. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121121

Chicago/Turabian StyleCai, Zhenhong, Yongkang Ye, Akash Kumar, Hongwei Rong, Baihui Cui, Fang Zhang, and Dabin Guo. 2025. "Investigation of the Synergistic Aromatization Effect During the Co-Pyrolysis of Wheat Straw and Polystyrene Modulated by an HZSM-5 Catalyst" Catalysts 15, no. 12: 1121. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121121

APA StyleCai, Z., Ye, Y., Kumar, A., Rong, H., Cui, B., Zhang, F., & Guo, D. (2025). Investigation of the Synergistic Aromatization Effect During the Co-Pyrolysis of Wheat Straw and Polystyrene Modulated by an HZSM-5 Catalyst. Catalysts, 15(12), 1121. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121121