Abstract

The pyridylamines 2,6-Me2C6H3NHCR2-C5H5H-2 (R = H, L1H; Me, L2H) on treatment with Me3Al (one equivalent) afforded the complexes [Al(Me)2(L1)] (1) and [Al(Me)2L2] (2), respectively. Use of excess L1H led to [Al(Me)(L1)2] (3). The molecular structures of 1–3 are reported, and the three complexes, as well as the parent compounds L1H and L2H, have been screened, in the presence of benzyl alcohol (BnOH), as catalysts for the ring opening polymerization (ROP) of ε-caprolactone and δ-valerolactone. Results revealed that these ROPs proceed in a controlled nature (Đ ≤ 1.33 for ε-CL and ≤1.48 for δ-VL) in the process without catalyst deactivation, whilst the products formed were predominantly linear with OBn/OH end groups; L1H and L2H exhibited little or no activity.

1. Introduction

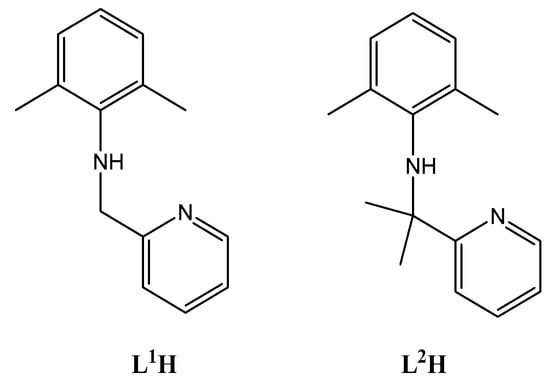

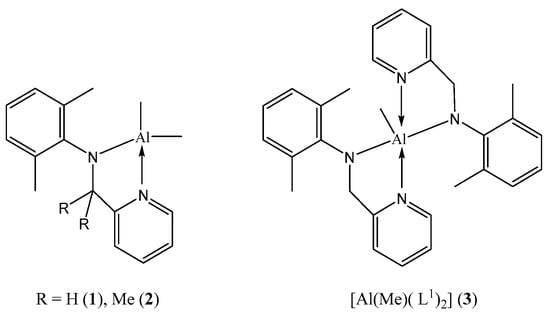

Plastic pollution continues to be a significant global issue. With this in mind, much research is being devoted to exploring methods of accessing more environmentally friendly polymer products. One possibility that is attracting the attention of coordination chemists is the use of metal-catalysts in the ring opening polymerization (ROP) of cyclic esters [,,,,,]. In such a process, the ability to modify the ligation at the metal not only allows for control over the catalytic behaviour of the catalyst but can also greatly influence the resulting polymer properties. For such a catalytic system, it is useful to employ an earth-abundant element as the catalytic centre, with favourable toxicity and Lewis acidity. For example, metals such as magnesium, potassium, calcium, iron and zinc have received recent interest [,,,,,]. With this in mind, we and others have also been exploring the use of aluminium-based catalysts as the catalytic centre in ROP systems; aluminium is the third most abundant element in the earth’s crust [,,,,,,,,,,]. It is also noteworthy from previous studies that the use of chelate ligation is highly beneficial. In this study, we have chosen to employ two pyridylamines, namely 2,6-Me2C6H3NHCR2-C5H5N-2 (R = H, L1H; Me, L2H; Figure 1), as the precursors in order to employ 2-pyridylmethylanilido ligation at the aluminium centre (see 1–3, Figure 2). The presence of the additional methyl in the backbone of L2 (versus L1) allows for a comparative study of the influence of the sterics associated with the ligand backbone. We note that L1 has previously been employed with titanium and zirconium to form catalysts capable of cis-1,4-polymerization of 1,3-butadiene [], and we have reported that the use of ligation based on L1 results in active ethylene dimerization/polymerization catalysts based on vanadium [,,] and niobium []. Moreover, we note that pyridyl-alkylamide aluminium catalysts bearing naphthyl substituents (see I and II, Figure S1, SM) have been utilised for the ROP of ε-caprolactone (ε-Cl) [], whilst catalysts bearing 2,6-diisopropylphenyl motifs at nitrogen centres are efficient for the block copolymerization of L-, D- and rac-lactide and ε-Cl (M = Zn, see III–VI, Figure S1, SM) [], the ROP of ε-CL (M = Fe) [], and for the ROP of δ-alkyl-δ-lactones and ε-lactones [].

Figure 1.

Pyridylamines employed herein.

Figure 2.

Complexes 1–3 reported herein.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis of Ligands and Complexes

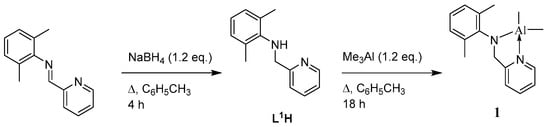

The pyridylamine L1H is readily available via reduction (NaBH4) of the parent pyridylimine, as shown in Scheme 1 [,,]. The complex [Me2Al(L1)] (1) is formed in good yield (>60%) following subsequent treatment with trimethylaluminium (1.2 equiv.) in refluxing toluene. The 1H NMR spectrum of 1 is shown in Figure S2 in the SM.

Scheme 1.

Synthetic route to complex 1.

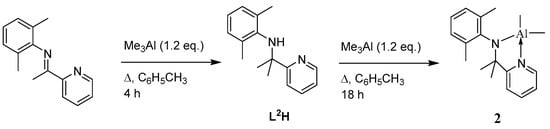

In the case of L2H, the synthetic method (Scheme 2) involves methyl transfer to the imine backbone via the use of trimethylaluminium. Such a method has proved fruitful in the formation of a variety of bi- and tridentate ligand sets [,,,]. Subsequent treatment of the pyridylamine with a second equivalent of trimethylaluminium affords [Me2Al(L2)] (2) in high yield (>90%). The 1H NMR spectrum of 2 is shown in Figure S3 in the SM.

Scheme 2.

Synthetic route to complex 2.

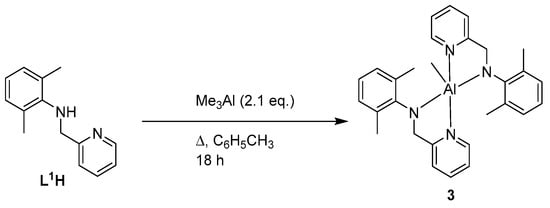

We then decided to explore if changing the reaction stoichiometry would affect the nature of the product formed. Using L1H as an example, it was found that on increasing the amount of L1H to 2.1 equivalents (Scheme 3), work-up as for 1 afforded large colourless blocks in good yield (>90%). Spectroscopic and analytical data were consistent with the formula [Al(Me)(L1)2] (3). The 1H NMR spectrum of 3 is shown in Figure S4 in the SM.

Scheme 3.

Synthetic route to complex 3.

2.2. Molecular Structures of Complexes

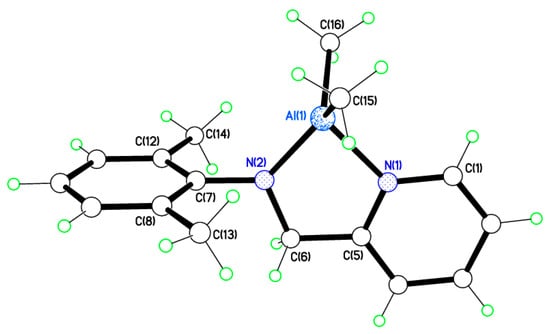

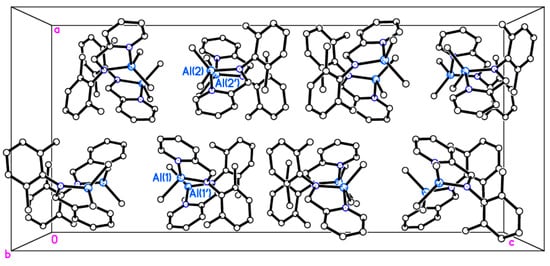

Single crystals of [Al(Me)2(L1)] (1) suitable for X-ray crystallography were obtained from a saturated solution of acetonitrile on standing at 0 °C. A view of the molecular structure is shown in Figure 3 and in the packing is shown in Figure 4. Selected bond lengths and angles are given in the caption. There are two very similar molecules of 1 in the asymmetric unit. One chelating pyridylamine binds to an AlMe2 motif, and the geometry at Al is distorted tetrahedral. The dihedral angles between ring systems in each molecule are N(1)/N(2)/C(1) > C(6) vs. C(7) > C(12) = 87.51(7)° and N(3)/N(4)/C(17) > C(22) vs. C(23) > C(28) = 80.08(7)°. Thus, in both cases they are almost perpendicular but a few degrees different. In the packing, molecules are arranged in anti-parallel stacks, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Molecular structure of [Al(Me)(L1)] (1), one of two very similar molecules in the asymmetric unit. Selected bond lengths (Å) and bond angles (°): Al(1)–N(1) 1.982(2), Al(1)–N(2) 1.838(2), Al(1)–C(15) 1.971(3); N(1)–Al(1)–N(2) 84.60(10), N(1)–Al(1)–C(15) 106.70(11).

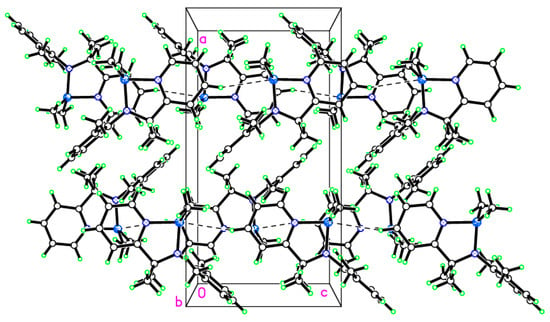

Figure 4.

Packing in 1 with anti-parallel stacks.

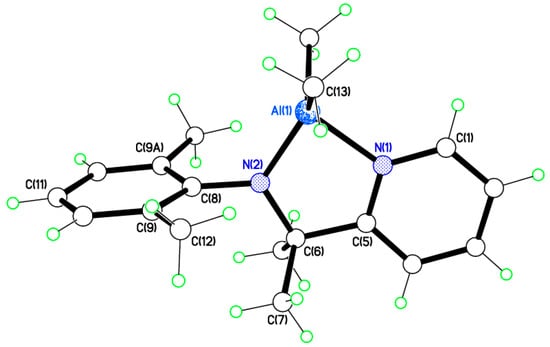

In the case of 2, crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were again grown from acetonitrile at 0 °C. A view of the molecular structure is shown in Figure 5, with selected bond lengths and angles given in the caption. The presence of the extra methyl groups on the chelate backbone again led to the formation of a structure with one chelate bound to an AlMe2 motif. We note that other studies have shown that changing the bulk of nitrogen-bound substituents in alkyl-2-pyridinamine diethyl aluminium complexes allows for monomer, dimer, or trimer formation []. Half of the molecule of 2 is unique. The atoms Al(1), N(1), C(1) > C(6), N(2), C(8) and C(11) are positioned on a mirror plane. The xylene group on N(2) is perpendicular to the pyridyl moiety of the chelating ligand to avoid Me group steric clashes.

Figure 5.

Molecular structure of [Me2Al(L2)] (2). Selected bond lengths (Å) and bond angles (°): Al(1)–N(1) 1.9579(8), Al(1)–N(2) 1.8422(8), Al(1)–C(13) 1.9772(7); N(1)–Al(1)–N(2) 85.26(3), N(1)–Al(1)–C(13) 107.51(3).

In the packing (Figure 6), there is a weak H-bonding interaction from C(3)–H(3)···Al(1′) = 3.13 Å {symm. operator ′ = x, y, z + 1}, and this does seem to have pushed the Me groups on Al(1) slightly towards N(1) {See Figure S5 in the Supplementary Materials}. Molecules are arranged in anti-parallel stacks {See Figure 5 and Figure S6}.

Figure 6.

Weak C–H∙∙∙Al interactions in the packing of 2 giving rise to chains in the c direction.

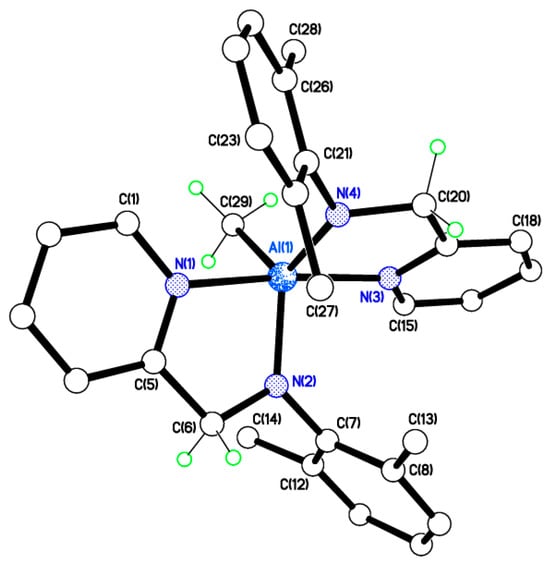

Single crystals of [Al(Me)(L1)2] (3) suitable for X-ray crystallography were obtained from a saturated solution of acetonitrile on standing at 0 °C. There is one molecule in the asymmetric unit (Figure 7) with the two pyridylamines binding to an AlMe centre which is closer to trigonal bipyramidal with N(1) and N(3) axial than to square-based pyramidal at the Al3+ ion, with τ = 0.82 []. The two chelating ligands coordinate anti-parallel to avoid methyl group steric clashes.

Figure 7.

Molecular structure of [Al(Me)(L1)2] (3). Selected bond lengths (Å) and bond angles (°): Al(1)–N(1) 2.0698(11), Al(1)–N(2) 1.8671(11), Al(1)–N(3) 2.0811(11), Al(1)–N(4) 1.8703(11), Al(1)–C(29) 1.9982(13); N(1)–Al(1)–N(2) 81.45(4), N(3)–Al(1)–N(4) 81.12(4), N(1)–Al(1)–C(29) 93.65(5).

3. Ring Opening Polymerization (ROP)

3.1. Ring Opening Polymerization of ε-Caprolactone (ε-CL)

Complexes 1–3 and the parent compounds L1H and L2H have been screened for their ability to act as catalysts for the ROP of ε-caprolactone (ε-CL), and the results are presented in Table 1. Runs were recorded at both 50 °C and 80 °C, and it was evident that better conversions were achieved at the elevated temperature. For example, at 80 °C over 30 min, the conversions observed for 1 (98%, run 5), 2 (77%, run 11) and 3 (81%, run 20), are somewhat higher than those observed at 50 °C over the same time period (34% for 1, run 3; 11% for 2, run 7, 5.8% for 3, run 15). The molecular weights (Mn) of the products were higher at the elevated temperatures albeit with similar control, i.e., narrow polydispersities (Mw/Mn = Ð = 1.17–1.33). A 13C NMR spectrum of a representative sample of PCL is provided in the SM (Figure S7).

Table 1.

The ROP of ε-CL catalysed by 1–3, L1H and L2H a.

Kinetics

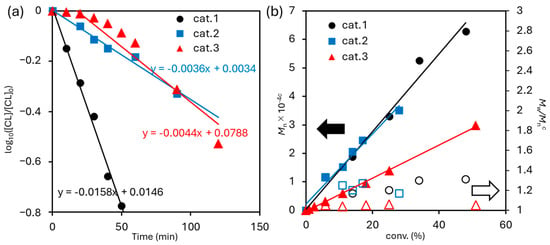

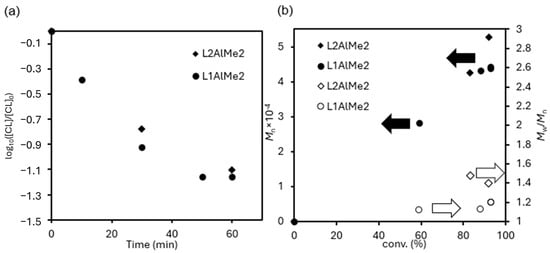

As shown in Figure 8a, the monomer consumption rate showed first order dependence toward the monomer concentration, expressed as [CL], suggesting that these ROPs by 1–3 proceeded without catalyst decomposition. Moreover, linear relationships between Mn values in the resultant polymer vs. polymer yield (conversion of CL) were demonstrated in Figure 8b, whereas the PDI (Mw/Mn) values were low in all cases, strongly suggesting that the ROPs proceeded in a living manner.

Figure 8.

(a) Time course plots of log10[CL]/[CL]0. [CL] = concentration of CL in mmol mL−1. The conditions are described in Table 1 (polymerization at 50 °C, runs 1–5; runs 6–10; run 13–19). (b) Mn and Mw/Mn vs monomer conversion in the ROP of ε-caprolactone initiated by L1AlMe2/BnOH (cat. 1); L2AlMe2/BnOH (cat. 2) and L12AlMe2/BnOH (cat. 3) catalyst systems. The detailed conditions are summarised in Table 1.

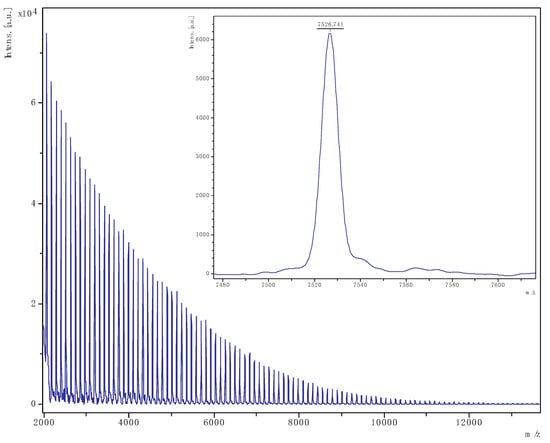

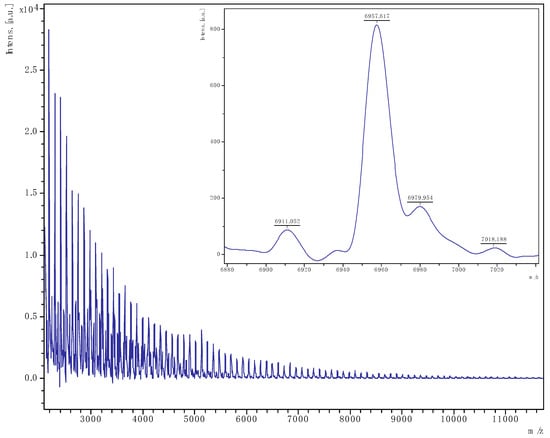

To further verify the end groups present, the PCL samples were analysed by MALDI-ToF mass spectrometry. Representative examples are shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10 (see also Figure S8, SM), and in each case, one main family of polymers was evident as sodium adducts with end groups comprising OBn/OH.

Figure 9.

PCL obtained from run 4 (Table 1). The main family is chain polymer terminated by OH and BnO end groups); [M = 107.13 (OBn) + 1.008 (H) + n × 114.14 (CL) + 22.99 (Na)] (e.g., for n = 65, calc. 7527.2 obsv. 7526.7).

Figure 10.

PCL obtained from run 12 (Table 1). The main family is chain polymer terminated by OH and BnO end groups); [M = 107.13 (OBn) + 1.008 (H) + n × 114.14 (CL) + 22.99 (Na)] (e.g., for n = 60, calc. 6956.5 obsv. 6957.6).

Given the interest in transition metal-free ROP catalysts [], the parent pyridylamines were also screened under more robust conditions (80 °C over 1 h, see runs 22 and 23, Table 1). However, little or no polymer was obtained.

3.2. δ-Valerolactone (δ-VL)

Data for the ROP of δ-VL is presented in Table 2. Runs were recorded at 50 °C, and for 1 it was evident that best results were obtained for a catalyst loading of 40 μmol for ≥30 min (runs 16–18, Table 2). Under similar conditions, conversions using 2 were similar (runs 19, 20, Table 2); however, the observed molecular weights (Mn) were somewhat lower. Also, in the case of 3, conversions were comparable over 60 min (run 32), though somewhat lower over 30 min (run 31); in each case, molecular weights (Mn) were lower than those observed for 1 and 2. A 13C NMR spectrum of a representative sample of PVL is provided in the SM (Figure S9).

Table 2.

The ROP of δ-VL catalysed by 1–3.

As for ε-CL, use of either L1H or L2H with δ-VL under more robust conditions (80 °C) failed to afford any polymeric products.

3.2.1. Kinetics

As demonstrated in the ROP of CL, the monomer consumption rate in ROP of VL showed first order dependence toward the monomer concentration (Figure 11a), expressed as [VL], suggesting that these ROPs by 1 (and maybe 2) proceeded without catalyst decomposition. As shown in Figure 11b, a linear correlation between Mn values in the resultant polymer vs. polymer yield (conversion of VL) by catalyst 1 suggests a quasi-living nature of the ROP.

Figure 11.

(a) Time course plots of log10[VL]/[VL]0. [VL] = concentration of VL in mmol mL−1. The conditions are described in Table 1 (polymerization at 50 °C, runs 15–19; runs 20–21). (b) Mn and Mw/Mn vs monomer conversion in the ring opening polymerization of ε-caprolactone initiated by L1AlMe2/BnOH (1; ●,○); L2AlMe2/BnOH (2; υ,◇) catalyst systems. The detailed conditions are summarised in Table 2.

3.2.2. MALDI-ToF Spectra

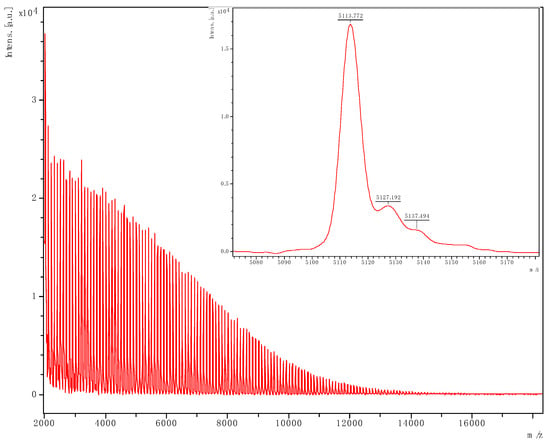

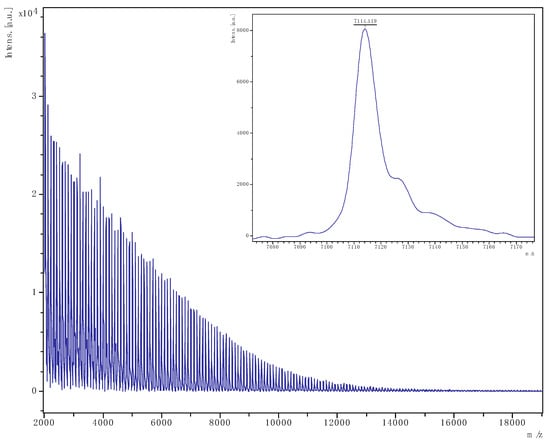

As for the PCL, analysis of the polymers by MALDI-ToF (Figure 12 and Figure 13, see also Figure S10, SM) revealed the formation of chain polymers with end groups comprising OBn/OH.

Figure 12.

PVL obtained from run 25 (Table 2). The main family is chain polymer terminated by OH and BnO end groups); [M = 107.13 (OBn) + 1.008 (H) + n × 100.11 (VL) + 22.99 (Na)] (e.g., for n = 50, calc. 5113.6 obsv. 5113.8).

Figure 13.

PVL obtained from run 26 (Table 2). The main family is chain polymer terminated by OH and BnO end groups); [M = 107.13 (OBn) + 1.008 (H) + n × 100.11 (VL) + 22.99 (Na)] (e.g., for n = 70, calc. 7114.1, obsv. 7114.1).

4. Experimental

4.1. General

The reactions were conducted under a nitrogen atmosphere using standard Schlenk techniques unless specified otherwise. Toluene was dried over sodium, acetonitrile dried over calcium hydride, and solvents were degassed prior to use. The known compound L1H was prepared using the method proposed in the literature []. The reagent Me3Al was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Gillingham, UK) and was used as received. ε-Caprolactone (Fisher Scientific, Loughborough, UK) and δ-valerolactone (Sigma Aldrich, Gillingham, UK) were dried (CaH2) and distilled prior to use. NMR spectra were recorded at 400.2 MHz on a JEOL ECZ 400S spectrometer (Peabody, MA, USA), using residual protic solvent as the internal standard. Chemical shifts are provided in ppm (δ) with coupling constants (J) given in Hertz (Hz). Combustion analyses were performed by the elemental analysis service at London Metropolitan University or the Xi’an Rare Metal Materials Research Institute Co., Ltd. Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionisation Time of Flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry was performed using a Bruker autoflex III Smart beam in linear mode, and the spectra were acquired by averaging at least 100 laser shots. The matrix used was 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid with THF as the solvent. The ionising agent used was sodium chloride dissolved in methanol. Samples were prepared by mixing 20 μL of matrix solution in THF (2 mg·mL−1) with 20 μL of matrix solution (10 mg·mL−1) and 1 μL of a solution of ionising agent (1 mg·mL−1). Following this, 1 mL of these mixtures was deposited on a target plate and allowed to dry under air at ambient temperature. OmniSEC software (Malvern Panalytical Ltd., Malvern, UK, v11.35) was used to calculate the molecular weights from the experimental traces.

4.1.1. Synthesis of L2H

A mixture of 1-(pyridin-2-yl)ethan-1-one (7.60 g, 62.7 mmol), 2,6-dimethylaniline (7.55 g, 62.3 mmol) and p-toluenesulfonic acid (615 mg, 3.24 mmol) in toluene (30 mL) was refluxed for 16 h. On cooling, the reaction mixture was then extracted with AcOEt and washed with brine. The organic layer was dried over Na2SO4 and the solvent removed under vacuum, to afford 11.7 g (52.2 mmol, 83%) of the intermediate. AlMe3 (12.5 mL, 25.0 mmol, 2M solution) was added to the resulting intermediate (5.00 g, 22.3 mmol) in toluene (120 mL) and the system was refluxed for 4 h. The reaction mixture was quenched with 3M NaOH aq. at 0 °C and then extracted with AcOEt and washed with brine. After the solvent was removed from the organic layer under vacuum, the crude product was purified using silica gel chromatography (AcOEt/Hex 4/1). L2H was obtained as orange oil. Yield: 3.63 g, 68%. 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6 298 K) δ: 8.46 (m, 1H, arylH), 7.36 (m, 1H, arylH), 7.13 (m, 2H, arylH), 7.10 (m, 1H, arylH), 6.63 (m, 1H, arylH), 4.09 (s, 1H, N-H), 2.07 (s, 6H, o-CH3), 1.50 (s, 6H, C-Me2).

4.1.2. Synthesis of [Me2Al(L1)] (1)

To L1H (1.00 g, 4.71 mmol) in toluene (20 mL) was added the AlMe3 (2.83 mL, 5.66 mmol, 2M solution) and the system was refluxed for 18 h. On cooling, the volatiles were removed in vacuo, and the residue was extracted into MeCN (20 mL). Standing at 0 °C afforded 1 as colourless prisms. Yield: 0.77 g, 61%. Found: C 71.39, H 7.90, N 10.83%. C16H21AlN2 requires C 71.62, H 7.89, N 10.44%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6, 298 K) δ: 7.58 (m, 1H, arylH), 7.22 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H, arylH), 7.08 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, arylH), 6.68 (m, 1H, arylH), 6.37 (overlapping m, 2H, arylH), 4.37 (s, 2H, CH2), 2.48 (s, 6H, o-CH3), −0.27 (s, 6H, Al-CH3).

4.1.3. Synthesis of [Me2Al(L2)] (2)

As for 1, but using L2H (1.00 g, 4.16 mmol) and AlMe3 (2.50 mL, 2 M, 5.00 mmol), affording 2 as colourless prisms. Yield: 1.13 g, 92%. Found: C 72.56, H 8.68, N 9.40%. C18H25AlN2 requires C 72.94, H 8.50, N 9.45%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6, 298 K) δ: 7.60 (m, 1H, arylH), 7.25 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H, arylH), 7.06 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H, arylH), 6.82 (m, 1H, arylH), 6.68 (m, 1H, arylH), 6.29 (m, 1H, arylH), 2.48 (s, 6H, o-CH3), 1.27 (s, 6H CMe2), −0.28 (s, 6H, Al-CH3).

4.1.4. Synthesis of [MeAl(L1)2] (3)

As for 1, but L1H (2.00 g, 9.42 mmol) in toluene (20 mL) was added to AlMe3 (2.25 mL, 4.50 mmol, 2M solution), which afforded 3 as colourless blocks. Yield: 1.69 g, 81%. Found: C 73.55, H 7.25, N 12.23%. C29H33AlN4 requires C 74.97, H 7.16, N 12.06%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6, 298 K) δ: 7.40 (m, 1H, arylH), 7.17 (m, 2H, arylH), 6.86 (m, 3H, arylH), 6.73 (m, 2H, arylH), 6.65 (m, 2H, arylH), 6.41 (overlapping m, 2H, arylH), 6.10 (overlapping m, 2H, arylH), 4.49 (d, J = 20.0 Hz, 2H, CH2), 4.29 (d, J = 20.0 Hz, 2H, CH2), 2.57 (s, 6H, o-CH3), 2.02 (s, 6H, o-CH3), −0.28 (s, 3H, Al-CH3).

4.2. Procedure for ROP of ε-Caprolactone or δ-Valerolacone

A toluene solution of pre-catalyst (0.010 mmol, 1.0 mL toluene) was added into a Schlenk tube in the glovebox at room temperature. The solution was stirred for 2 min, and then the appropriate equivalent of BnOH (from a pre-prepared stock solution of 1 mmol BnOH in 100 mL toluene) and the appropriate amount of ε-CL (or δ-VL), along with 1.5 mL toluene, was added to the solution. For example, for Table 2, entry 1, a toluene solution of pre-catalyst 1 (0.010 mmol, 1.0 mL toluene) was added into a Schlenk tube, then 2 mL BnOH solution (1 mmol BnOH/100 mL toluene) and 20 mmol ε-CL along with 1.5 mL toluene was added to the solution. The reaction mixture was then placed into an oil/sand bath pre-heated at 130 °C, and the solution was stirred for the prescribed time (24 h). The polymerization mixture was quenched on addition of an excess of glacial acetic acid (0.2 mL) to the solution, and the resultant solution was then poured into methanol (200 mL). The resultant polymer was then collected on filter paper and was dried in vacuo.

4.2.1. Kinetic Studies

The polymerizations were carried out at 130 °C in toluene (2 mL) using 0.010 mmol of complex. The molar ratio of monomer to initiator was fixed at 500:1, and at appropriate time intervals, 0.5 μL aliquots were removed (under N2) and were quenched with wet CDCl3. The percent conversion of monomer to polymer was determined using 1H NMR spectroscopy.

4.2.2. Crystallography

Diffraction data for 1–3 were collected at low temperature on rotating-anode Rigaku XtalLAB AFC11 (RCD3), FRE+ or 007HF diffractometers, respectively, equipped with HyPix detectors (Neu-Isenberg, Germany). The data were corrected for Lp effects and absorption. All structures were solved via dual-space, iterative, charge-flipping methods [] and refined routinely on F2 values []. Further details are given in Table 3 below. CCDC, 2414170 {1}, 2385189 {2} and 2385188 {3} contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures (accessed on 10 November 2025).

Table 3.

Crystallographic data for 1–3.

5. Conclusions

The pyridylamines 2,6-Me2C6H3NHCR2-C5H5H-2 (R = H, L1H; Me, L2H) upon reaction with equimolar amounts of Me3Al undergo a methyl transfer to the imine backbone to afford the complexes [Al(Me)2(L1)] (1) and [Al(Me)2L2] (2) in good yield (>90%). Use of excess L1H led to the isolation of the bis-chelate complex [Al(Me)(L1)2] (3). These aluminium-based systems are active as catalysts for the ROP of ε-caprolactone and δ-valerolactone when employed in solution (toluene) under N2. The products are of medium to high molecular weight for PCL (1.15–12.4 × 104 Da) and medium molecular weight for PVL (1.59–5.27 × 104 Da), and generally have narrow Ð (1.15–1.33 for PCL; 1.05–1.48 for PVL). MALDI-ToF mass spectra of the polymers indicated that linear polymers with BnO/H end groups were formed. Kinetic profiles revealed the living nature of the process without catalyst deactivation. Whilst direct comparisons with the majority of the pyridyl-alkylamide aluminium catalysts bearing naphthyl substituents (see I and II, Figure S1, SM) mentioned earlier are not possible given the differing ROP conditions, we note that the system bearing II (R = iPr) was screened at 50 °C over 30 and 60 min (250:1:1 for ε-CL:Al:BnOH in toluene) which afforded conversions of 86 and 100%, respectively. The catalysts herein only matched such conversions at 80 °C. In terms of the products formed, the naphthyl complexes afforded PCL with Mn 20270 Da (30 min) and 28880 Da (60 min), which are results comparable with those observed for 1 (see entries 3 and 4, Table 1) at the same temperature, whilst the control, as evidenced by the Đ values, was better in the case of 1. The parent compounds L1H and L2H used in this work were virtually inactive for the ROP of ε-CL and δ-VL under the conditions employed.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/catal15121119/s1: Figure S1, Literature compounds I–VI. Figures S2–S4, 1H NMR spectrum of complexes 1–3 (400 MHz in C6D6 at 20 °C. Figures S5–S6, Additional figures for crystallographic analysis of 2. Figures S7–S9, 13C NMR spectra of representative polymers, Figures S8–S10, MALDI-ToF spectra of ring opened polymers.

Author Contributions

S.S.: Investigation. I.M.: Investigation. M.R.J.E.: Investigation, Writing—review and editing. K.N.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. C.R.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We thank the Royal Society for support (grant number IECR32113010).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Labet, M.; Thielemans, W. Synthesis of polycaprolactone: A review. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 3484–3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbaoui, A.; Redshaw, C. Metal Catalysts for ε-caprolactone polymerisation. Polym. Chem. 2010, 1, 801–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.M. Stereo-controlled ring-opening polymerization of cyclic esters: Synthesis of new polyester microstructures. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhu, D.; Zhang, W.; Solan, G.A.; Ma, Y.; Sun, W.-H. Recent progress in the application of group 1, 2 & 13 metal complexes as catalysts for the ring opening polymerization of cyclic esters. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2019, 6, 2619–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, O.; Zhang, X.; Redshaw, C. Synthesis of biodegradable polymers: A review on the use of Schiff-base metal complexes as catalysts for the Ring Opening Polymerization (ROP) of cyclic esters. Catalysts 2020, 10, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.-J.; Lee, W.; Ganta, P.K.; Chang, Y.-L.; Chang, Y.-C.; Chen, H.-Y. Multinuclear metal catalysts in ring-opening polymerization of ε caprolactone and lactide: Cooperative and electronic effects between metal centers. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 475, 214847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Auria, I.; D’Alterio, M.C.; Tedesco, C.; Pellecchia, C. Tailor-made block copolymers of L-, D- and rac-lactides and e-caprolactone via one-pot sequential ring opening polymerization by pyridylamidozinc(II) catalysts. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 32771–32779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, J.; Sarker, A.; Panda, T.K. Alkali and alkali earth metal complexes as versatile catalysts for ring-opening polymerization of cyclic esters. Chem. Rec. 2021, 21, 1898–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, O.H.; Capet, F.; Visseaux, M.; Champouret, Y. Homoleptic and heteroleptic substituted amidomethylpyridine iron complexes: Synthesis, structure and polymerization of rac-lactide. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 2022, e2022000073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W.; Sun, W.-H. Progress of ring-opening polymerization of cyclic esters by iron compounds. Organometallics 2023, 42, 1680–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravina, G.; Pierri, G.; Pellecchia, C. New highly acive Fe(II) pyridylamido catalyst for the ring opening polymerization and copolymerization of cyclic esters. Mol. Catal. 2024, 555, 113891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasa, N.; Fujiki, M.; Nomura, K. Ring-opening polymerization of various cyclic esters by Al complex catalysts containing a series of phenoxy-imine ligands: Effect of the imino substituents for the catalytic activity. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2008, 292, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasa, N.; Katao, S.; Liu, J.; Fujiki, M.; Furukawa, Y.; Nomura, K. Notable effect of fluoro substituents in the imino group in ring-opening polymerization of ε-caprolactone by Al complexes containing phenoxyimine ligands. Organometallics 2009, 28, 2179–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Iwasa, N.; Nomura, K. Synthesis of Al complexes containing phenoxy-imine ligands and their use as the catalyst precursors for efficient living ring-opening polymerisation of ε-caprolactone. Dalton Trans. 2008, 3978–3988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, K.-Q.; Elsegood, M.R.J.; Prior, T.J.; Sun, X.; Mo, S.; Redshaw, C. Organoaluminium complexes of o-,m-,p-anisidines: Synthesis, structural studies and ROP of ε-caprolactone. Cat. Sci. Tech. 2014, 4, 3025–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuoco, T.; Pappalardo, D. Alkyl aluminum complexes bearing salicylaldiminato ligands: Initiators in the ring-opening polymerization of cyclic esters. Catalysts 2017, 7, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhao, K.-Q.; Mo, S.; Al-Khafaji, Y.; Prior, T.J.; Elsegood, M.R.J.; Redshaw, C. Organoaluminium complexes derived from Anilines or Schiff bases for ring opening polymerization of ε-caprolactone, δ-valerolactone and rac-lactide. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 2017, 1951–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Valle, F.M.; Cuenca, T.; Mosquera, M.E.G.; Millone, S.; Cano, J. Ring-opening polymerization (ROP) of cyclic esters by versatile aluminum diphenoxyimine complexes: From polylactide to random copolymers. Eur. Polym. J. 2020, 125, 109527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Han, M.; Wang, X.; Solan, G.A.; Wang, R.; Ma, Y.; Sun, W.-H. Phenoxy-imine/-amide aluminum complexes with pendant or coordinated pyridine moieties: Solvent effects on structural type and catalytic capability for the ROP of cyclic esters. Polymer 2022, 242, 124602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar, S.; Nath, P.; Bano, K.; Karmakar, H.; Sharma, J.; Sarkar, A.; Panda, T.K. Binunclear and mononuclear aluminum complexes as quick and controlled initiators of well-orderd ROP of cyclic esters. ChemCatChem 2024, 16, e202300972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumrit, P.; Kamavichanurat, S.; Joopor, W.; Wattanathana, W.; Nakornkhet, C.; Hormnirun, P. Aluminium complexes of phenoxy-azo ligands in the catalysis of rac-lactide polymerisation. Dalton Trans. 2024, 53, 13854–13870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Lόpez, J.D.; García-Álvarez, A.-C.; Hernández-Balderas, U.; Gallardo-Garibay, A.; Jancik, V.; Martínez-Otero, D.; Moya-Cabrera, M. Ligand-directed assembly of multimetallic aluminum complexes: Synthesis, structure and ROP catalysis. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 27, e202400466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, L.; Pragliola, S.; Pappalardo, D.; Tedesco, C.; Pellecchia, C. New (anilidomethyl)pyridine Titanium(IV) and Zirconium(IV) catalyst precursors for the Highly Chemo- and Stereoselective cis-1,4-polymerization of 1,3-buadiene. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 1934–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Katao, S.; Sun, W.-H.; Nomura, K. Synthesis of (arylimido)vanadium(V) complexes containing (2-anilidomethyl)pyridine ligands and their use as the catalyst precursors for olefin polymerization. Organometallics 2009, 28, 5925–5933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Nomura, K. Highly efficient dimerization of ethylene by (imido)vanadium complexes containing (2-anilidomethyl)pyridine ligand: Notable ligand effect toward activity and selectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 4960–4965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, K.; Mitsudome, T.; Igarashi, A.; Nagai, G.; Tsutsumi, K.; Ina, T.; Omiya, T.; Takaya, H.; Yamazoe, S. Synthesis of (Adamantylimido)vanadium(V) Dimethyl Complex Containing (2-Anilidomethyl)pyridine Ligand and Selected Reactions: Exploring the Oxidation State of the Catalytically Active Species in Ethylene Dimerization. Organometallics 2017, 36, 530–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuboki, M.; Nomura, K. (Arylimido)niobium(V) Complexes Containing 2-Pyridylmethylanilido Ligand as Catalyst Precursors for Ethylene Dimerization That Proceeds via Cationic Nb(V) Species. Organometallics 2019, 38, 1544–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, A.P.; Boyron, O.; Champouret, Y.D.M.; Patel, M.; Singh, K.; Solan, G.A. Dimethyl-Aluminium Complexes Bearing Naphthyl-Substituted Pyridine-Alkylamides as Pro-Initiators for the Efficient ROP of ε-Caprolactone. Catalysts 2015, 5, 1425–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nienkemper, K.; Kehr, G.; Kehr, S.; Fröhlich, R.; Erker, G. (Amidomethyl)pyridine zirconium and hafnium complexes: Synthesis and structural characterization. J. Organomet. Chem. 2008, 693, 1572–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knijnenburg, Q.; Smits, J.M.M.; Budzelaar, P.H.M. Reaction of the Diimine Pyridine Ligand with Aluminum Alkyls: An Unexpectedly Complex Reaction. Organometallics 2006, 25, 1036–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, C.J.; Gregory, A.; Griffith, P.; Perkins, T.; Singh, K.; Solan, G.A. Use of Suzuki cross-coupling as a route to 2-phenoxy-6-iminopyridines and chiral 2-phenoxy-6-(methanamino) pyridines. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 9857–9864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhou, S.; Feng, Z.; Guo, L.; Zhu, X.; Mu, X.; Yao, F. Aluminum Alkyl Complexes Supported by Bidentate N,N Ligands: Synthesis, Structure, and Catalytic Activity for Guanylation of Amines. Organometallics 2015, 34, 1882–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Yang, S.; Ding, Y.; Xia, D. Study on the effect of substituents on the structure, volatility, and fluorescence of N-(Alkyl or TMS)-2-pyridinamine diethyl aluminum complexes. J. Organomet. Chem. 2021, 933, 121646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addison, A.W.; Rao, T.N.; Reedijk, J.; van Rijn, J.; Verschoor, G.C. Synthesis, structure, and spectroscopic properties of copper(II) compounds containing nitrogen–sulphur donor ligands; the crystal and molecular structure of aqua[1,7-bis(N-methylbenzimidazol-2′-yl)-2,6-dithiaheptane]copper(II) perchlorate. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1984, 1349–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-H.; Wang, F.-C.; Ko, B.-T.; Yu, T.-L.; Lin, C.-C. Ring-Opening Polymerization of ε-Caprolactone and L-Lactide Using Aluminum Thiolates as Initiator. Macromolecules 2001, 34, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Save, M.; Schappacher, M.; Soum, A. Controlled Ring-Opening Polymerization of Lactones and Lactides Initiated by Lanthanum Isopropoxide, 1. General Aspects and Kinetics. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2002, 203, 889–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dove, A.P. Organic Catalysis for Ring Opening Polymerization. ACS Macro Lett. 2012, 1, 1409–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT–Integrated space-group and crystal structure determination. Acta Cryst. 2015, A71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Cryst. 2015, C71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).