Rapid Preparation of g-C3N4/GO Composites via Electron Beam Irradiation for Enhanced Ofloxacin Removal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Result and Discussion

2.1. Characterization of X kGy-g-C3N4/GO

2.2. Adsorption Properties of X kGy-g-C3N4/GO

2.2.1. Effect of Irradiation Dose and Reaction Time

2.2.2. Effect of Adsorbent Dosage and Initial OFL Concentration

2.2.3. Effect of Coexisting Ions

2.2.4. Effect of pH

2.2.5. Effect of Temperature

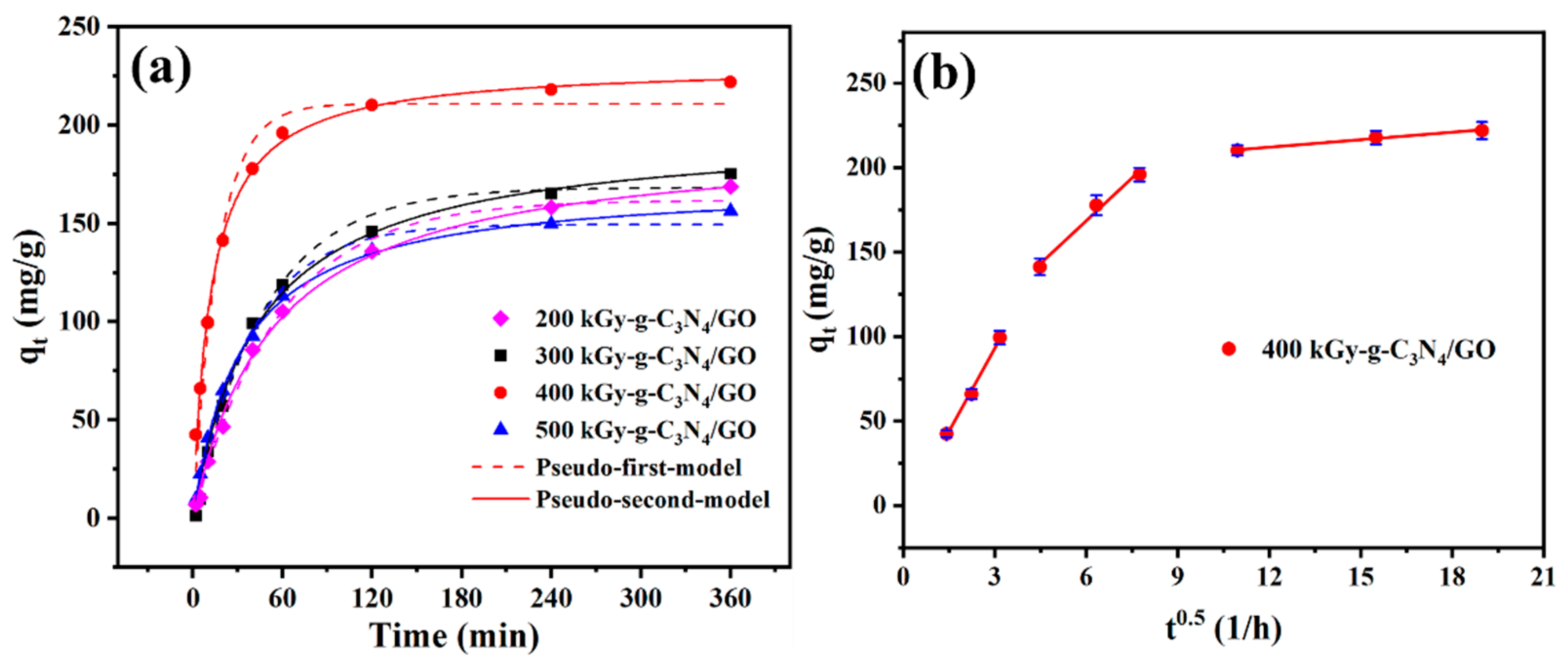

2.3. Adsorption Kinetics

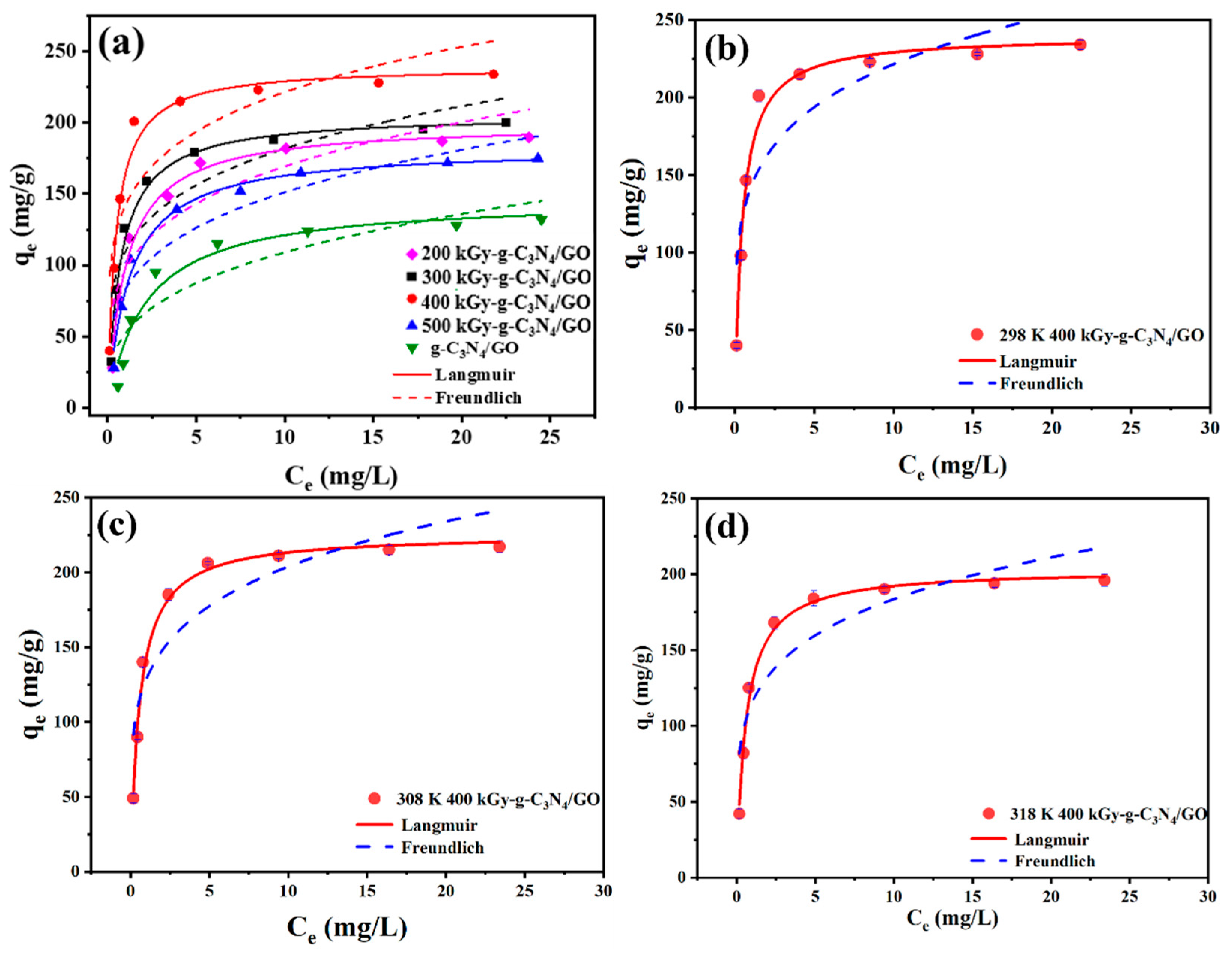

2.4. Adsorption Isotherms and Thermodynamics

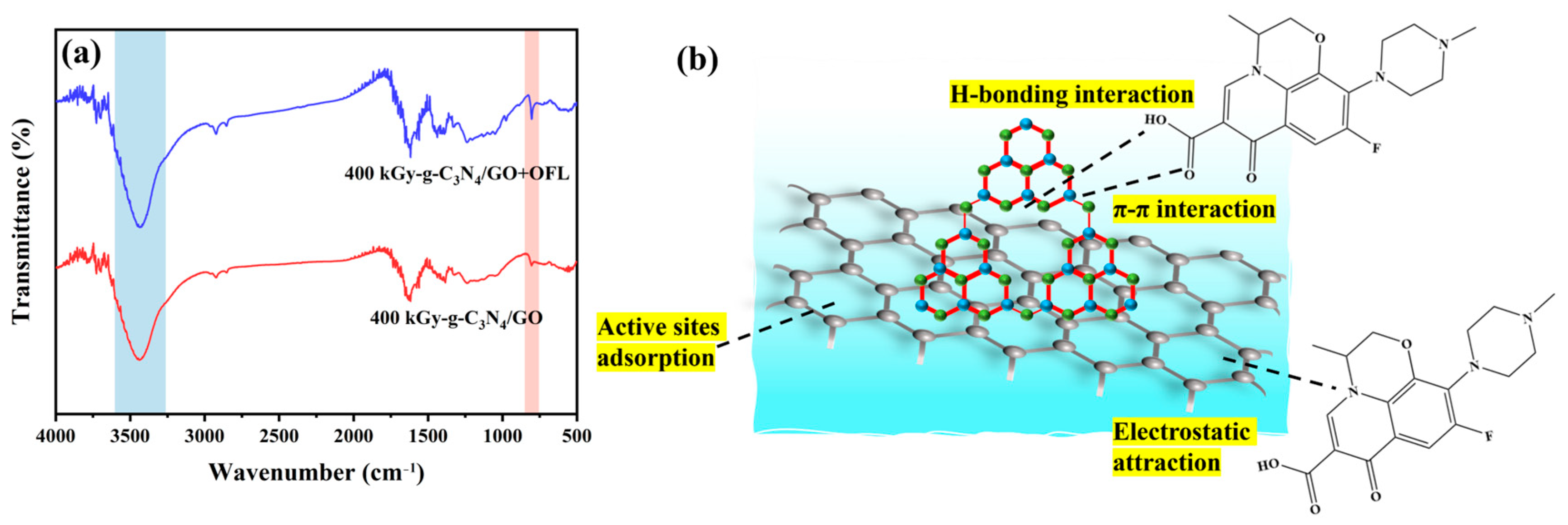

2.5. Adsorption Mechanism

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals and Reagents

3.2. Adsorbents Preparation

3.2.1. Preparation for GO

3.2.2. Preparation of g-C3N4

3.2.3. Preparation of X kGy-g-C3N4/GO

3.3. Characterization

3.4. Adsorption Experiments

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, J.; Jiao, G.H.; Sheng, G.; Lin, N.P.; Yang, B.J.; Wang, J.F.; Jiang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.D. Microwave-assisted PMS activation Ti3C2/LaFe0.5Cu0.5O3-P catalysts for efficient degradation of CIP: Enhancement of catalytic performance by phosphoric acid etching. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 354, 129357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, J.; Ma, Y.; Han, T.; Quan, G.; Zhang, X.; Lei, J.; Liu, N. Treatment of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products (PPCPs) Using Periodate-Based Advanced Oxidation Technology: A Review. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 512, 162355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Xu, J.; Zhai, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Dang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Li, Z.; Huang, W.; Zhang, X.; Tang, L. Structure–Activity Relationship in Periodate Activation by Fe-MOFs: Why MIL-101(Fe) Outperforms Other MIL-Series in Antibiotic Degradation. Green Energy Environ. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, G.H.; Yang, Y.X.; Wang, J.F.; Zhang, J.H.; Jiang, H.; Liu, N.; Zhang, X.D. 3D structure of LaFe1-δCoδO3@carbon cloth composite catalyst for promoting peroxymonosulfate activation: Identification of catalytic mechanism towards multiple antibiotics. Desalination 2025, 602, 118643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Sheng, G.; Wang, J.F.; Yang, B.J.; Jiang, H.; Liu, N.; Zhang, X.D. LaFeO3 anchoring on ZIF-67 for the activation of peroxymonosulfate toward ofloxacin degradation: Radical and non-radical reaction pathways. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 362, 131846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.J.; Zhang, Q.F.; Zhou, X.; Chen, J.H.; Chen, Z.H.; Liu, Z.Z.; Yan, J.; Wang, J. Removal of Fluoroquinolone Antibiotics by Adsorption of Dopamine-Modified Biochar Aerogel. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 40, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, X.; Cai, W.; Owens, G.; Chen, Z. Magnetic Iron Nanoparticles Calcined from Biosynthesis for Fluoroquinolone Antibiotic Removal from Wastewater. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 319, 128734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zheng, D.; Bai, B.; Hu, N.; Wang, H. Solar-Driven Photothermal-Fenton Removal of Ofloxacin through Waste Natural Pyrite with Dual-Function. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 641, 128574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Ren, L.; Tan, X.; Chu, H.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X. Removal of Ofloxacin with Biofuel Production by Oleaginous Microalgae Scenedesmus Obliquus. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 315, 123738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaswal, A.; Kaur, M.; Singh, S.; Kansal, S.K.; Umar, A.; Garoufalis, C.S.; Baskoutas, S. Adsorptive Removal of Antibiotic Ofloxacin in Aqueous Phase Using rGO-MoS2 Heterostructure. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 417, 125982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barquilha, C.E.R.; Braga, M.C.B. Adsorption of Organic and Inorganic Pollutants onto Biochars: Challenges, Operating Conditions, and Mechanisms. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2021, 15, 100728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Chen, Q.; Chen, G.; Shi, G.; Ruan, C.; Feng, M.; Ma, Y.; Jin, X.; Liu, X.; Du, C.; et al. N-Doped Activated Carbon for High-Efficiency Ofloxacin Adsorption. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2022, 335, 111848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komal; Gupta, K.; Nidhi; Kaushik, A.; Singhal, S. Amelioration of Adsorptive Efficacy by Synergistic Assemblage of Functionalized Graphene Oxide with Esterified Cellulose Nanofibers for Mitigation of Pharmaceutical Waste. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Lang, Y.; Liu, B.; Zhao, H. Ofloxacin Adsorption on Chitosan/Biochar Composite: Kinetics, Isotherms, and Effects of Solution Chemistry. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 2019, 39, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, N.; Imran, M.; Ramzan, M.; Anwar, A.; Alsafari, I.A.; Asgher, M.; Iqbal, H.M.N. Functionalized Graphene Oxide-Zinc Oxide Hybrid Material and Its Deployment for Adsorptive Removal of Levofloxacin from Aqueous Media. Environ. Res. 2023, 217, 114958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Tian, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, Z.; Dai, W.; Quan, G.; Lei, J.; Zhang, X.; Tang, L. Three-Dimensional MIL-88A(Fe)-Derived α-Fe2O3 and Graphene Composite for Efficient Photo-Fenton-like Degradation of Ciprofloxacin. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2025, 36, 111063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunleye, D.T.; Akpotu, S.O.; Moodley, B. Adsorption of Sulfamethoxazole and Reactive Blue 19 Using Graphene Oxide Modified with Imidazolium Based Ionic Liquid. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020, 17, 100616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, N.; Raheem, A. Mechanistic Investigation of Levofloxacin Adsorption on Fe (III)-Tartaric Acid/Xanthan Gum/Graphene Oxide/Polyacrylamide Hydrogel: Box-Behnken Design and Taguchi Method for Optimization. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2023, 127, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, W.; Tan, L.; Ng, Y.; Yong, S.; Chai, S. Graphitic Carbon Nitride (g-C3N4)-Based Photocatalysts for Artificial Photosynthesis and Environmental Remediation: Are We a Step Closer to Achieving Sustainability? Chem. Rev. 2016, 16, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Zhu, C.; Yang, J.; Sun, D. Facile Self-Assembly N-Doped Graphene Quantum Dots/Graphene for Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 216, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, Y.S.; Petrenko, V.V.; Alekseev, P.A.; Bystrov, P.A.; Souvorova, O.V. Trends and Opportunities for the Development of Electron-Beam Energy-Intensive Technologies. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2022, 198, 110199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Dong, H.; Zhou, D.; Tang, K.; Ma, Y.; Han, T.; Lei, J.; Huang, S.; Zhang, X.; Tang, L.; et al. Electron Beam- Induced Defect Engineering Construction in MIL-68(In) for Enhanced CO2 Photoreduction: Unravelling Organic Framework Defects. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2026, 702, 138990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Li, X.; Chen, T.; Zhao, Y.; Xiong, H.H.; Han, X.B. Application Progress of Electron Beam Radiation in Adsorption Functional Materials Preparation. Molecules 2025, 30, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Tang, Y.; Jin, R.; Meng, Q.; Chen, Y.; Long, X.; Wang, L.; Guo, H.; Zhang, S. Ultrasonic-Microwave Assisted Synthesis of GO/g-C3N4 Composites for Efficient Photocatalytic H2 Evolution. Solid State Sci. 2019, 97, 105990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.T.; Li, N.; Wang, M.; Zhao, B.P.; Long, F. Synthesis of Novel and Stable G-C3N4-Bi2WO6 Hybrid Nanocomposites and Their Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity under Visible Light Irradiation. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 171419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, H.; Liu, Y.; Hu, B.; Huang, S.; Zhang, X.; Lei, J.; Liu, N. In Situ Electronic Modulation of G-C3N4/UiO66 Composites via N Species Functionalized Ligands for Enhanced Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 379, 134964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla, A.; Li, Y.; Mandal, B.; Kang, S.G.; Hur, S.H.; Chung, J.S. Selective Adsorption of Organic Dyes on Graphene Oxide: Theoretical and Experimental Analysis. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 464, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svoboda, L.; Škuta, R.; Matějka, V.; Dvorský, R.; Matýsek, D.; Henych, J.; Mančík, P.; Praus, P. Graphene Oxide and Graphitic Carbon Nitride Nanocomposites Assembled by Electrostatic Attraction Forces: Synthesis and Characterization. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2019, 228, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla, A.; Youk, J.H. Mechanochemical Synthesis of Graphitic Carbon Nitride/Graphene Oxide Nanocomposites for Dye Sorption. Dye. Pigment. 2023, 220, 111725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, S.; Ke, X.X.; Shao, Z.D.; Zhong, L.B.; Zhao, Q.B.; Zheng, Y.M. Fish Scale-Based Biochar with Defined Pore Size and Ultrahigh Specific Surface Area for Highly Efficient Adsorption of Ciprofloxacin. Chemosphere 2022, 287, 131962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Chan, L.; Li, D.Y.; Yi, R.-B.; Mo, J.W.; Wu, M.H.; Xu, G. Controllable reduction of graphene oxide by electron-beam irradiation. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.M.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, B.J. Effects of electron beam irradiation on dimethyl methlyphosphonate adsorption behavior of activated carbon fibers. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 314, 118641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitek, J.; Czerniak-Łosiewicz, K.; Gertych, A.-P.; Giza, M.; Dąbrowski, P.; Rogala, M.; Wilczynski, K.; Sławomir, K.; Conran, B.R.; Wang, X.C.; et al. Selective Growth of van der Waals Heterostructures Enabled by Electron-Beam Irradiation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 33838–33847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, P.; Zhu, L.; Huang, Z.; Cao, Z.; Meng, X. Fabrication of Graphene/Cu Composites with in-Situ Grown Graphene from Solid Carbon Source. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 2372–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Ji, X.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Lin, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Lin, Y.; Gradon, L.; Zheng, Y.; et al. Carbon Nitride Nanosheets Induce Pulmonary Surfactant Deposition via Dysfunction of Alveolar Secretion and Clearance. Nano Today 2024, 58, 102457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, F.K.; Song, Y.Z.; Gui, H.G.; Cui, A.J.; Yao, C. Synergetic Adsorption–Photocatalytic Activated Fenton System via Iron-Doped g-C3N4/GO Hybrid for Complex Wastewater. Catalysts 2023, 13, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyth, S.M.; Nabae, Y.; Moriya, S.; Kuroki, S.; Kakimoto, M.; Ozaki, J.; Miyata, S. Carbon Nitride as a Nonprecious Catalyst for Electrochemical Oxygen Reduction. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 20148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y. In-Situ Synthesis of C3N4/CdS Composites with Enhanced Photocatalytic Properties. Chin. J. Catal. 2015, 36, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Sun, Y.J.; Fu, M.; Ho, W.K.; Lee, S.; Wu, Z.B. Novel in Situ N-Doped (BiO)2CO3 Hierarchical Microspheres Self-Assembled by Nanosheets as Efficient and Durable Visible Light Driven Photocatalyst. Langmuir 2011, 1, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaha, C.K.; Mahmud, M.A.A.; Saha, S.; Karmaker, S.; Saha, T.K. Efficient Removal of Sparfloxacin Antibiotic from Water Using Sulfonated Graphene Oxide: Kinetics, Thermodynamics, and Environmental Implications. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Y.; Zhao, L.; Ao, V.Q.; Zhang, G.; Kang, D.Q.; Li, Y.L.; Liu, J.; Ding, G.T.; Ma, Z.R.; Tewo, Y.H.; et al. Exploring the cationic surfactant adsorption efficiency at concentrations relative to the critical micelle concentration by SA/SiO2 microspheres. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 367, 122069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Q.; He, X.; Shu, L.; Miao, M. Ofloxacin Adsorption by Activated Carbon Derived from Luffa Sponge: Kinetic, Isotherm, and Thermodynamic Analyses. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2017, 112, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derya, A.D.; Dilek, D.Y.; Yalçın, Ş.Y. Magnetic chitosan/calcium alginate double-network hydrogel beads: Preparation, adsorption of anionic and cationic surfactants, and reuse in the removal of methylene blue. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 239, 124311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Cai, Y.; Song, M.; Qi, K.; Xie, X. S-Scheme BiVO4/CQDs/β-FeOOH Photocatalyst for Efficient Degradation of Ofloxacin: Reactive Oxygen Species Transformation Mechanism Insight. Chemosphere 2022, 295, 133784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Xiong, X. A Porous Molybdenum Disulfide and Reduced Graphene Oxide Nanocomposite (MoS2-rGO) with High Adsorption Capacity for Fast and Preferential Adsorption towards Congo Red. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 1150–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Jang, H.M. Comparative Study on Characteristics and Mechanism of Levofloxacin Adsorption on Swine Manure Biochar. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 351, 127025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, D.; Han, X.; Xing, B. Adsorption of Antibiotic Ciprofloxacin on Carbon Nanotubes: pH Dependence and Thermodynamics. Chemosphere 2014, 95, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, S.; Zhao, J.; Liang, G.; Xie, X. Mechanistic Insights into Removal of Norfloxacin from Water Using Different Natural Iron Ore–Biochar Composites: More Rich Free Radicals Derived from Natural Pyrite-Biochar Composites than Hematite-Biochar Composites. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 255, 117752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Singh, N.; Rajor, A. RSM-CCD Optimized Prosopis Juliflora Activated Carbon for the Adsorptive Uptake of Ofloxacin and Disposal Studies. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 25, 102176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michela, S.; Constantin, P.; Giulia, G.; Federica, M.; Giovanna, B.; Francesco, M.; Antonella, P.; Doretta, C. Combined Layer-by-Layer/Hydrothermal Synthesis of Fe3O4@MIL-100(Fe) for Ofloxacin Adsorption from Environmental Waters. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Wu, Z. High Adsorption for Ofloxacin and Reusability by the Use of ZIF-8 for Wastewater Treatment. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2020, 308, 110494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehtesabi, H.; Bagheri, Z.; Yaghoubi-Avini, M. Application of Three-Dimensional Graphene Hydrogels for Removal of Ofloxacin from Aqueous Solutions. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2019, 12, 100274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, N.S.; Mohamad Amini, M.H.; Danish, M.; Sulaiman, O.; Hashim, R.; Demirel, S.; Demirel, G.K. Characterization and Ofloxacin Adsorption Studies of Chemically Modified Activated Carbon from Cassava Stem. Materials 2022, 15, 5117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alatawi, R.A.S. Construction of Amino-Functionalized Molecularly Imprinted Silica Particles for (±)-Ofloxacin Chiral Separation. Chem. Sel. 2023, 8, e202204455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.B.; Soomro, U.; Muqeet, M.; Ahmed, Z. Adsorption of Indigo Carmine Dye onto the Surface-Modified Adsorbent Prepared from Municipal Waste and Simulation Using Deep Neural Network. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 408, 124433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novoselov, K.S.; Geim, A.K.; Morozov, S.V. Electric field effect inatomically thin carbon films. Science 2004, 306, 666–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, C.; Li, Y.; Qi, B.; Li, Z.; He, Z.; Wang, B.; Fang, F.; Dai, X.; Qin, X.; Wan, Y. Preparation of Amine-Modified Lignin Adsorbent for Highly Efficient and Selective Removal of Sodium Dodecyl Benzene Sulfonate from Greywater. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 353, 128334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Zhao, X.; Song, K.; Gao, D.; Yang, Z.; Han, L. Valorizing copper-contaminated manure into biochar for tetracycline adsorption: Dynamics and interactions of tetracycline adsorption and copper leaching. Waste Manag. 2025, 203, 114880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J. PEI-grafted graphene oxide modified phosphogypsum for the adsorption and removal of heavy metals and dyes in wastewater. Water Res. 2025, 286, 124236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Models | Adsorbents | Parameters | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| qt (mg·g−1) | K1 (min−1) | R2 | ||

| Pseudo-first-order | 200 kGy-g-C3N4/GO 300 kGy-g-C3N4/GO 400 kGy-g-C3N4/GO 500 kGy-g-C3N4/GO | 161.7 168.2 210.7 149.5 | 0.018 0.020 0.060 0.026 | 0.998 0.996 0.970 0.990 |

| qt (mg·g−1) | K1 (min−1) | R2 | ||

| Pseudo-second-order | 200 kGy-g-C3N4/GO 300 kGy-g-C3N4/GO 400 kGy-g-C3N4/GO 500 kGy-g-C3N4/GO | 193.4 197.6 230.6 171.0 | 9.68 × 10−5 1.16 × 10−4 3.57 × 10−4 1.81 × 10−4 | 0.996 0.989 0.995 0.999 |

| Intra-particle diffusion | 400 kGy-g-C3N4/GO | Kb mg·(g·min1/2)−1 | C (mg·g−1) | R2 |

| 32.68 | 0.297 | 0.991 | ||

| 16.87 | 79.64 | 0.974 | ||

| 1.477 | 196.8 | 0.977 | ||

| Langmuir | Freundlich | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorbents | T (K) | KL (L·mg−1) | qm (mg·g−1) | R2 | n | KF [(mg·g−1) (L mg−1)1/n] | R2 |

| 200 kGy-g-C3N4/GO | 298 | 0.97 | 199.9 | 0.979 | 4.126 | 97.00 | 0.809 |

| 300 kGy-g-C3N4/GO | 298 | 1.36 | 206.0 | 0.983 | 4.559 | 109.7 | 0.797 |

| 400 kGy-g-C3N4/GO | 298 | 2.16 | 239.6 | 0.984 | 5.182 | 142.0 | 0.765 |

| 308 | 1.75 | 225.3 | 0.991 | 5.016 | 128.8 | 0.795 | |

| 318 | 1.72 | 203.2 | 0.992 | 4.970 | 115.5 | 0.795 | |

| 500 kGy-g-C3N4/GO | 298 | 0.81 | 182.9 | 0.983 | 3.846 | 83.10 | 0.855 |

| Adsorbent | Adsorption Capacity (mg·g−1) | Optimum pH | Temperature (K) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice husk ash | 6.26 | 6.0 | - | [49] |

| Fe3O4 Metal–organic framework | 218.0 | - | 298 | [50] |

| ZIF-8 MOF | 194.1 | 7.0 | 298 | [51] |

| 3D Graphene hydrogel | 134.0 | - | 363 | [52] |

| Raw cassava stem | 42.37 | 8.0 | 328 | [53] |

| Amino functionalized molecularly imprinted silica | 261.1 | 7.0 | - | [54] |

| 400 kGy-g-C3N4/GO | 222.0 | 7.0 | 298 | This Work |

| T (K) | ∆G0 (kJ·mol−1) | ∆H0 (kJ·mol−1) | ∆S0 (kJ·mol −1·K−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 298 | −25.21 | −10.25 | 0.050 |

| 308 | −25.66 | ||

| 318 | −26.21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Z.; Guo, S.; Ni, B.; Lin, Z.; Han, T.; Wang, D.; Lei, J.; Liu, N. Rapid Preparation of g-C3N4/GO Composites via Electron Beam Irradiation for Enhanced Ofloxacin Removal. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1118. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121118

Li Z, Guo S, Ni B, Lin Z, Han T, Wang D, Lei J, Liu N. Rapid Preparation of g-C3N4/GO Composites via Electron Beam Irradiation for Enhanced Ofloxacin Removal. Catalysts. 2025; 15(12):1118. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121118

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Zhiying, Shaohua Guo, Beibei Ni, Zhuopeng Lin, Tao Han, Denghui Wang, Jianqiu Lei, and Ning Liu. 2025. "Rapid Preparation of g-C3N4/GO Composites via Electron Beam Irradiation for Enhanced Ofloxacin Removal" Catalysts 15, no. 12: 1118. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121118

APA StyleLi, Z., Guo, S., Ni, B., Lin, Z., Han, T., Wang, D., Lei, J., & Liu, N. (2025). Rapid Preparation of g-C3N4/GO Composites via Electron Beam Irradiation for Enhanced Ofloxacin Removal. Catalysts, 15(12), 1118. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121118