Abstract

Harnessing solar energy directly through photocatalysis is an effective approach to addressing the energy crisis and environmental pollution. This green technology enables both sustainable energy production and the removal of environmental contaminants simultaneously. Heterojunction photocatalysts demonstrate superior performance by enhancing light utilization efficiency and inhibiting the recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs. The reconstruction of active sites in heterojunction photocatalysts, encompassing changes in their valence states and coordination environments, has been extensively studied. However, the unique structural self-adaptive phenomenon displayed by heterojunction photocatalysts that incorporate flexible components during the photocatalysis process has not been extensively investigated. Indeed, this intriguing self-adaptive behavior may be closely linked to their photocatalytic properties. Extensive studies indicate that this structural self-adaptation is predominantly driven by flexible materials, with flexible metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) finding particularly broad application. Based on this understanding, we briefly summarize and offer insights into the structural design and fundamental principles of such photocatalytic heterojunction catalysts while also providing an outlook for future research.

1. Introduction

In the 21st century, humanity faces two major challenges: a worsening energy crisis and increasing environmental pollution. In response, developing green technologies that can achieve sustainable energy generation while purifying pollutants has become an urgent global priority and a shared goal in scientific research and industry. Photocatalytic technology, which converts solar energy into chemical energy, is characterized by its low cost, environmental friendliness, mild reaction conditions, and absence of secondary pollution []. It stands as one of the most promising technologies for producing clean energy and reducing environmental pollution. Since Honda and Fujishima [] first demonstrated photocatalytic water splitting for hydrogen production in 1972, photocatalysis has been widely applied in various fields, including hydrogen production from water splitting [], degradation of pollutants [], and reduction of carbon dioxide/nitrogen [,]. The key advantage of this approach is its ability to directly convert solar energy into chemical energy or utilize it for environmental cleanup. The entire process is eco-friendly, operates under mild conditions, generates no secondary pollution, and fully adheres to the principles of green chemistry and sustainable development. Heterojunction photocatalysts feature a heterojunction interface formed by staggered conduction and valence band energy levels. When carriers pass through this heterojunction interface, they achieve separation of photogenerated electrons and holes, minimizing undesirable charge recombination and effectively enhancing photocatalytic efficiency []. At present, the precise design of heterojunction has become the basic consensus and research focus in the field of photocatalysis.

Among the various branches of photocatalysis research, the in situ reconstruction phenomena of heterojunction photocatalysts during catalysis, including reconstruction of active sites, surface and interface reconstruction, have attracted widespread attention [,,,,,,]. These phenomena lead to changes in metal site valence states, coordination environments, and the generation of defects. Xie et al. found that in Cu-CuTCPP/g-C3N4, the initial paddlewheel CuII2(COO)4 nodes were reconstructed into partially reduced Cu1+δ2(COO)3 nodes, thereby promoting efficient photoreduction of carbon dioxide to ethane []. Dou et al. discovered that the formation of hydroxyl groups on ZnO (ZnO/CuOx-C CNFs) under illumination promoted the kinetics of CO2RR conversion to CH4 and oxygen evolution while inhibiting the generation of competitive HER and carbon monoxide []. It can be summed up that the reconstruction of heterojunction photocatalysts often has a significant impact on photocatalytic activity and stability.

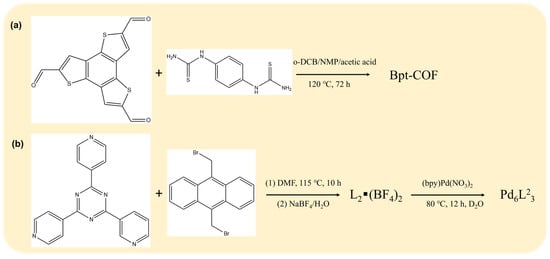

However, existing research mostly focuses on fixed active sites with relatively stationary spatial positions or ignores the dynamic changes in spatial conformations of active sites and photosensitive groups. There has been limited research on the impact of spatial structural changes in heterojunction photocatalysts on the recombination of photogenerated electrons and holes, as well as on photocatalytic reaction activity. In fact, Considering the basic structure-property principles, the changes in spatial conformations of photosensitizers, active sites, and others in heterojunction photocatalysts will inevitably lead to variations in their photocatalytic performance. For instance, Qin et al. demonstrated that a benzotrithiophene-based COF (Figure 1a)with thiourethane linkages exhibits reversible framework contraction/expansion (intralayer microflexibility) upon exposure to tetrahydrofuran or water. This adaptive pore hydrophilicity promotes efficient mass transfer and increases the accessibility of redox-active sites, leading to the nearly complete removal of micropollutants from wastewater with minimal energy consumption []. In a separate study, Luo et al. developed a biomimetic, water-soluble molecular capsule (Figure 1b) that undergoes a quantitative capsule-to-bowl transformation upon substrate binding to its hydrophobic cavity. The anthracene-based components enable visible-light absorption, and the resulting host-guest complex, stabilized by quintuple π-π stacking, exhibits charge-transfer absorption that drives the efficient aerobic photooxidation of sulfide guests under mild, visible-light irradiation []. Likewise, the phenomenon of structural self-adaptation has also attracted research interest in other fields. For instance, Yan et al. designed a novel water-soluble organic palladium host (Pd2L2), whose adaptive self-assembly and host–guest catalysis enable the highly efficient and selective photooxidation of toluene derivatives to aldehydes under mild conditions []. In another study, Xu et al. synthesized a trinuclear copper molecular catalyst (denoted as Cu3-flex) that exhibits dynamic and adaptive adjustment of copper spacing among adjacent sites within the triangular Cu3 core upon binding of two *CO intermediates and one *NO3− ion. The Cu3-flex catalyst demonstrates remarkable performance in the co-reduction of CO and NO3− for electrocatalytic urea synthesis []. From this perspective, this paper emphasizes summarizing the spatial conformational changes (structural self-adaptation phenomena) in heterojunction photocatalysts and proposes feasible ideas for the design of such photocatalysts.

Figure 1.

(a) Synthesis scheme 1 of Btp-COF []. (b) Synthesis scheme 2 of Pd6L23 [].

This review aims to systematically summarize and evaluate recent studies on the phenomenon of “structural self-adaptation” observed in photocatalytic heterojunction systems, thereby highlighting the emerging role of structural adaptive dynamics in photocatalysis research. Conventional heterojunction models often regard interfacial structures as static, which fails to adequately account for the dynamic evolution of interfacial behavior under realistic photocatalytic conditions, particularly in liquid or gas-phase reaction environments. For instance, Wang et al. successfully synthesized Cd-PLA using flexible dicarboxylic acids and 4,4′-bipyridine as co-ligands with Cd(NO3)2 []. While their work highlighted the remarkable light-harvesting capability and high photocatalytic activity of the bpy-containing Cd-PLA, the potential role of the flexible dicarboxylic acid ligand remained underexplored. It is possible that structural self-adaptation involving the flexible dicarboxylic acid moiety occurs during catalysis, opening a new avenue for investigation. A review of the literature reveals that this structural self-adaptive phenomenon is primarily enabled by flexible materials, among which flexible metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) are the most extensively utilized. The inherent structural features of MOF, including their high porosity, tunable chemical functionality, and stimuli-responsive flexibility, are highly conducive to structural self-adaptation. Their well-defined porous structures not only provide a confined environment for hosting and stabilizing active sites but also allow for dynamic framework adjustments in response to external stimuli such as light, guest molecules, or temperature [,,,]. This unique combination facilitates the in situ reconstruction of active centers and optimizes reaction interfaces, thereby significantly enhancing the dynamic performance and stability of heterojunction photocatalysts. For instance, Halder et al. reported a MOF capable of undergoing reversible crystal-to-crystal transformation triggered by water, constructed from rigid and flexible dicarboxylates along with various N,N′-donor ligands []. Similarly, Senkovska et al. have summarized the advanced applications of various flexible MOFs in energy storage and gas separation, leveraging their unique adsorption characteristics and responsive behavior. Screening these flexible MOFs for photocatalytic research also appears feasible []. Introducing such dynamic structural changes into photocatalytic systems could lead to unusual chemical effects. Therefore, this review seeks to clarify the important role of structural self-adaptation in overcoming the limitations of traditional static heterojunction models, proposing an insightful research direction and drawing broader attention to adaptive structures. To achieve the above objectives, we conducted a systematic literature survey and analysis. We screened research published in the past five years using keywords such as photocatalysis, heterojunction, structural self-adaptation, dynamic reconstruction, and in situ characterization to ensure content timeliness. Studies that solely discussed pre-synthesized static heterojunctions without addressing structural evolution during reactions, or those focusing predominantly on material synthesis without mechanistic insights, were excluded. Finally, the central goal of this review is to elucidate the prevalence, formation mechanisms, and key effects of the “structural self-adaptation” phenomenon—referring to spatial conformational changes in heterojunction catalysts—on charge carrier separation and surface reaction pathways. By integrating existing literature evidence, we ultimately aim to provide a theoretical foundation and novel design strategies for the rational development of highly efficient and stable photocatalysts endowed with adaptive and intelligent responsiveness.

2. Structural Self-Adaptation Behavior of Flexible Photocatalysts

2.1. Self-Adaptative Structural Twist of Framework

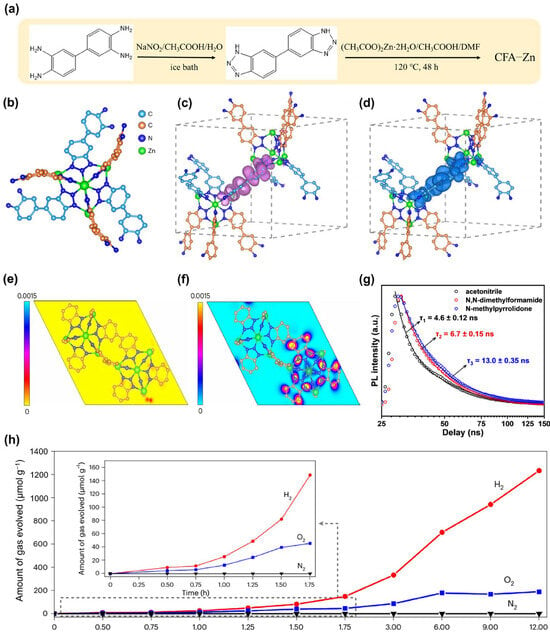

In plant photosynthesis, photosensitive elements absorb photons to generate excited electrons, which are then transferred to terminal electron acceptors with the assistance of cofactors, enabling further photosynthetic processes []. During this process, upon light excitation, usually isolated cofactors undergo structural changes to lower their energy, thereby prolonging the lifetime of excited electrons. In photocatalysis, this process corresponds to inhibiting the rapid recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs and avoiding unnecessary heat generation, thus allowing for an efficient photocatalytic process. Inspired by this, researchers [] have employed (Figure 2a) to obtain a flexible MOF (CFA-Zn) featuring electronically insulating Zn2+ nodes and two chemically equivalent but crystallographically distinct linkers (Figure 2b). Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations reveal that the conduction band minimum (CBM) and valence band maximum (VBM) of CFA-Zn are located on separate linkers, exhibiting non-overlapping band edges that behave as an electron donor-acceptor pair. In the ground state, they do not overlap. Upon excitation, the CBM linker undergoes significant structural distortion, leading to a rearrangement of excited state orbitals, which disrupts the relaxation pathway from the excited state to the ground state and achieves long-lived charge separation (Figure 2c,d). The distinct morphology of CFA-Zn suggests that its crystallographically independent linkers may be situated on different crystal facets. DFT-calculated projections of the VBM and CBM onto these facets indicate a preferential migration of photoexcited electrons (in the CBM) to the (001) facet (Figure 2e,f). The self-adaptive structural distortion was revealed by time-resolved PL spectroscopy (Figure 2g), which displayed a solvent viscosity-dependent fluorescence lifetime. This correlation stems from a competition between the rate of structural twisting in CFA-Zn and the charge recombination rate. Following photoexcitation (VB to CB), structural twisting hinders charge recombination. Fluorescence remains unchanged if charge recombination is faster than twisting, whereas a faster twisting rate alters the fluorescence lifetime. The observed viscosity-lifetime correlation confirms that self-adaptive structural twisting enhances charge separation. By introducing Pt and Co3O4 cocatalysts, remarkable performance and stability in photocatalytic water splitting were achieved (Figure 2h). This exceptional photocatalytic efficiency is attributed to the dynamic excited-state structural distortion of the MOF upon light excitation, which causes orbital rearrangement and inhibits radiative relaxation, thereby promoting long-lived charge-separated states.

Figure 2.

(a) Synthesis scheme 3 of CFA-Zn. (b) The [Zn5 × 4(L)6] SBU in the CFA-Zn structure viewed along the c axis with X and hydrogen atoms omitted for clarity. Spatial distribution profiles of the VBM (c) and CBM (d) in the excited state in the MOF single cell at an isosurface value of 0.003 e Å−3. Purple bubbles and dark blue bubbles represent the electron clouds. (e) Spatial distribution of the VBM and (f) CBM on the (001) facet of CFA-Zn. Charge density (in arbitrary units) is represented by the colour bar. Key: carbon (orange), nitrogen (blue), zinc (green). (g) Fluorescence lifetime decay curves for CFA-Zn in various solvents, monitored at an emission wavelength of 430 nm under excitation at 373 nm. (h) Photocatalytic OWS activity over Pt/CFA-Zn/Co3O4 under visible-light irradiation. Inset: enlargement of the induction period. Reprinted from [], reproduced with permission from Springer Nature.

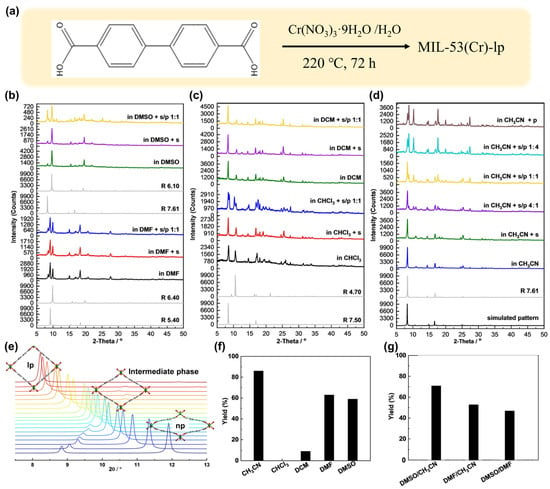

Beyond structural distortion, adaptive framework flexibility can also manifest through pore aperture modulation. In a representative study, researchers employed MIL-53(Cr) as a photocatalyst, where the pore structure was tuned by varying reaction solvents for dehalogenation of aryl halides []. Researchers have employed (Figure 3a) to obtain a met-al-organic frameworks MIL-53(Cr). PXRD analysis elucidated the solvent-dependent pore aperture evolution of the MIL-53(Cr) catalyst (Figure 3b–d). Compared with the simulated pattern from the structural model (Figure 3e), the pore dimensions of MIL-53(Cr) in different solvents were determined as follows: CH3CN (R = 7.61 Å), DCM (7.50 Å), CHCl3 (7.50/4.70 Å), DMSO (6.10 Å), and DMF (6.40/5.40 Å). CH3CN and DCM maintained an open-pore structure, whereas CHCl3, DMSO, and DMF induced slight pore contraction. The modulation of pore geometry significantly affected the reaction outcomes. Using 4′-bromoacetophenone as a model substrate and triethylamine as a sacrificial agent, solvent effects were systematically investigated in single or mixed organic systems. As shown in Figure 3f, Yield trends followed the order: CH3CN (88%) > DMF (63%) >DMSO (59%) > DCM (9%), no conversion occurred in CH3Cl. These results suggest a clear positive correlation between pore sizes and catalytic efficiency, with the largest pore in CH3CN affording the highest product yield. Notably, the photocatalytic activity could be finely regulated via solvent mixtures (Figure 3g). The decline in yield correlated with reduced pore aperture, confirming that catalytic efficiency can be modulated by solvent composition. In contrast to other adaptive structural changes, this work demonstrates autonomous control over pore structure via solvent tuning, enabling precise regulation of MIL-53(Cr) photocatalytic activity and highlighting the diversity of adaptive structural transformations.

Figure 3.

(a) Synthesis scheme 4 of MIL-53(Cr). (b,d) PXRD patterns of the large-pore form MIL-53(Cr)-lp under various environments: (b) in DMF and DMSO; (c) in DCM and CHCl3, including conditions with solvent only, with added substrate (s), and with both substrate and product (s/p, 1:1 ratio); (d) in CH3CN with solvent only and with varying substrate-to-product ratios (5:0, 4:1, 1:1, 1:4, 0:5). (e) Simulated structural evolution of MIL-53(Cr): PXRD patterns corresponding to pore aperture diameters (R) ranging from 3.6 Å to 7.8 Å. (f) Photocatalytic performance of MIL-53(Cr)-lp in the dehalogenation of 4′-bromoacetophenone across different organic solvents. (g) Catalytic yields obtained in mixed solvent systems: 1:1 blends of DMSO/CH3CN, DMF/CH3CN, and DMSO/DMF; CH3CN/H2O mixtures at 1:1 and 19:1 ratios; and in pure CH3CN using the narrow-pore form MIL-53(Cr)-np (H2O) as a reference. General yields for photocatalytic dehalogenation of diverse aryl halides over MIL-53(Cr) are summarized. Reprinted from [], reproduced with permission from Wiley.

2.2. Self-Adaptative Twist of Flexible Ligands

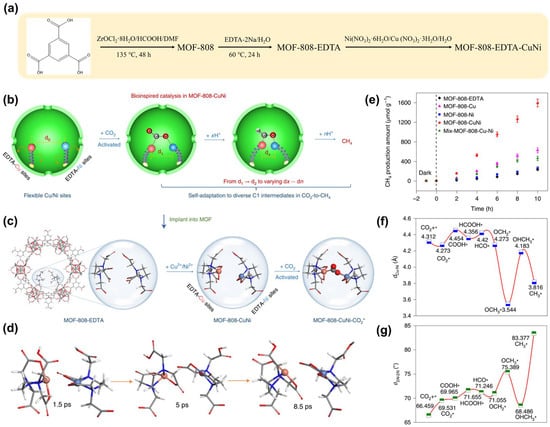

The photoreduction of CO2 to CH4 involves multiple proton-coupled electron transfer processes, accompanied by various electron transfer steps involving different reaction intermediates [,,,]. Therefore, providing appropriate interactions (suitable binding energies) for different intermediates at the active sites is crucial for enhancing selectivity. The dual metal site pair (DMSP) strategy has been proven to be an effective approach to improve selectivity [,,]. However, DMSPs in solid catalysts, due to their fixed positions, struggle to provide suitable adsorption energies for different intermediates [,,]. The three-dimensional active sites in biological enzymes can dynamically match with different intermediates directly. Inspired by this, researchers [] have employed (Figure 4a) to obtain an MOF photocatalyst embedded with Cu/Ni dual metal single-atom sites (abbreviated as Cu/Ni DMSP MOF, Figure 4b,c). Ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) reveals the dynamic nature of copper/nickel DMSP catalysis, where its spatial configuration can self-adjust to accommodate different intermediates (Figure 4d). During the photoreduction of CO2, this catalyst demonstrates an enzyme-like ability to dynamically stabilize C1 intermediates, significantly enhancing the activity and selectivity for methane (CH4) production (Figure 4e). Further density functional theory (DFT) calculations proposed a synergistic mechanism: during the multi-step photoreduction of CO2, the spatial structure of Cu/Ni DMSP can adaptively adjust according to the needs of different C1 intermediates (Figure 4f,g).

Figure 4.

(a) Synthesis scheme 5 of MOF-808-CuNi. (b) The flexible DMSPs for self-adaptive CO2-to-CH4 photoreduction. (c) Schematic diagram of bioinspired CO2 photoreduction in MOF-808-CuNi. (d) Snapshot images of a flexible Cu/Ni DMSP recorded at 1.5, 5.0 and 8.5 ps (the Zr-oxo clusters and ligands in MOF-808-CuNi have been removed for clarity). Carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, copper, nickel, and hydrogen atoms are depicted in grey, red, blue, orange, caeseous, and white, respectively. (e) Photocatalytic CO2 reduction performance. Configuration evolution with varying values of (f) dCu-Ni and (g) θ2N-2N. The * refers to a substance as a reaction intermediate. Reprinted from [], reproduced with permission from Springer Nature.

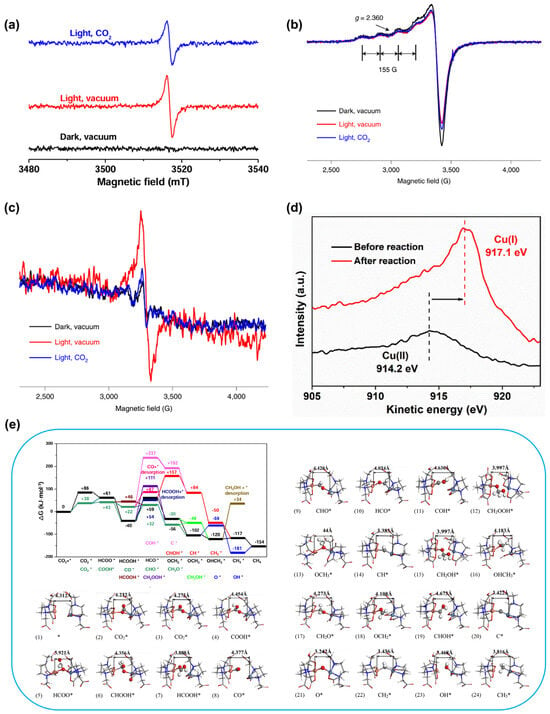

The charge transfer mechanism in MOF-808-CuNi during CO2 photoreduction was investigated by ESR (Figure 5a). The signal, attributed to oxygen-centered sites in Zr-oxo clusters formed by electron transfer from [Ru(bpy)3]Cl2, weakens under a CO2 atmosphere due to electron donation from Zr-oxo centers to CO2. Under irradiation, the Cu(II) signal diminishes with the concurrent appearance of a Cu(I) Auger peak, while the Ni(I) signal gains intensity (Figure 5b–d), confirming both metal sites act as electron acceptors from the Zr-oxo clusters. The partial recovery of these ESR signals upon CO2 introduction signifies electron transfer from the metal sites to CO2, triggering its reduction. Collectively, these results outline a charge transfer pathway: electrons move from Zr-oxo clusters to Cu/Ni DMSPs and subsequently couple with CO2 molecules. Furthermore, DFT calculations examined the concomitant bonding changes, underscoring the key role of the flexible Cu/Ni DMSPs in enabling the high CH4 selectivity. As shown in Figure 5e, the primary pathway for CO2 photoreduction on MOF-808-CuNi is as follows: CO2*—COOH*—CO*—HCO*—H2CO*—H3CO*—CH3OH*—CH3*—CH4 and demonstrating the dynamic changes in reaction intermediate configuration during the self-adaptive process. Throughout the reaction, the self-adaptive evolution of the Cu/Ni DMSPs enables synergistic thermodynamic and kinetic driving forces, resulting in outstanding activity and selectivity. The experimental results show that this MOF catalyst modified with flexible ligands (MOF-808-CuNi) exhibits exceptional activity and selectivity in the photoreduction of CO2 to CH4. Under light excitation, the self-adaptive twist of the flexible ligand (EDTA) enables adaptive binding of metal sites to different intermediates, thereby enhancing catalytic selectivity.

Figure 5.

(a) ESR spectra of Zr nodes in MOF-808 EDTA mixed with [Ru(bpy)3]Cl2·6H2O under different conditions. (b) ESR spectra of Cu species in MOF-808-CuNi under different conditions. (c) ESR spectra of Ni species in MOF-808-Ni under different conditions. (d) Cu LMM Auger spectra for MOF-808-CuNi with high Cu concentration (>2 wt%) before and after photocatalysis. (e) Proposed mechanism of self-adaptive flexible Cu and Ni sites in MOF-808-CuNi for CO2 photoreduction, including Gibbs free energy diagram and optimized structures of reaction intermediates. The (1–24) structural diagrams refer to the dynamic evolution of the reaction intermediate configurations during the optimized adaptive process. Atom color code: carbon (grey), oxygen (red), nitrogen (blue), copper (orange), nickel (caeseous), hydrogen (white). The * refers to a substance as a reaction intermediate. Reprinted from [], reproduced with permission from Springer Nature.

2.3. The Design Principles of Self-Adaptive Heterojunction Photocatalysts

A summary of key activity parameters/performance for a series of self-adaptive photocatalysts is provided in Table 1, demonstrating the feasibility of designing catalysts based on the structural self-adaptive phenomenon. The structural self-adaptation phenomenon in photocatalytic heterojunction catalysts arises from spatial structural changes that occur during the photocatalytic process in flexible materials or flexible ligands within rigid materials. Compared to commonly seen rigid heterojunction photocatalysts, flexible materials, such as flexible MOFs, flexible covalent organic frameworks (COFs, such as COF-300), and flexible covalent porphyrin frameworks (CPFs), exhibit potential spatial structural self-regulation under light excitation [,,]. They can stabilize charge-separated states through chemical separation, thus potentially achieving high photocatalytic activity. Heterojunction photocatalysts with rigid structures, like MOF-808, often have fixed active sites, and the reconstruction of these active sites typically occurs at these fixed locations, making it difficult for structural dynamic changes to occur. The adoption of flexible organic ligands for substitution, such as EDTA, long-chain alkanes, CF3COO−, etc., can be applied to this strategy. The active sites in heterojunction photocatalysts may interact simultaneously with substrate molecules through adaptive behavior, potentially leading to asymmetric adsorption of linear molecules (such as CO2, N2), which may facilitate molecular activation. During the reaction process, the adaptive behavior towards intermediates can effectively enhance the selectivity towards the target product.

Table 1.

Relevant information of a series of self-adaptive photocatalysts.

3. Summary and Perspective

In summary, this review systematically summarizes and evaluates recent research on the “structural self-adaptation” phenomenon observed in photocatalytic heterojunction systems, highlighting the emerging significance of such structural dynamics in photocatalysis. The structural self-adaptation phenomenon observed in this heterojunction photocatalyst exhibits exceptional performance in inhibiting the rapid recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs and dynamically regulating the binding energy between active sites and reaction intermediates. This is crucial for enhancing the efficiency and selectivity of heterojunction photocatalysts. Consequently, the integration of structural self-adaptation phenomena into photocatalytic research merits increased attention from the scientific community. Although existing research has demonstrated the existence of the structural self-adaptation phenomenon in catalysts during photocatalysis, there is still a need for further exploration. (1) It is necessary to design catalysts in conjunction with specific reactions, potentially leveraging machine learning and other advanced techniques for catalyst screening. (2) Besides photo response catalysis, such self-adaptation phenomena may also exist in thermally driven, magnetically driven, and other processes, which merits further investigation. (3) Since the structural adaptive changes of catalysts occur at the microscopic level, current characterization methods face challenges in direct observation, relying instead on theoretical simulations for verification. Therefore, the development of in situ characterization techniques to further substantiate this in situ process is crucial.

Author Contributions

T.L. and J.W. contributed equally to this work. Prepared the manuscript: T.L., J.W. and S.Z. Reviewed the manuscript: W.J., Z.L., J.L., Y.D.K. and W.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22305227). Wu J. was supported by China Scholarship Council (CSC) Grant #202307040009. Ji W. was supported by the Ningxia Natural Science Foundation (2024AAC03048).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhou, P.; Navid, I.A.; Ma, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, P.; Ye, Z.; Zhou, B.; Sun, K.; Mi, Z. Solar-to-hydrogen efficiency of more than 9% in photocatalytic water splitting. Nature 2023, 613, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujishima, A.; Honda, K. Electrochemical photolysis of water at a semiconductor electrode. Nature 1972, 238, 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Huang, Y.; Sun, F.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, X.; Fan, F.; Luo, Y.; et al. Dynamic structural twist in metal–organic frameworks enhances solar overall water splitting. Nat. Chem. 2024, 16, 1638–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Q.; Feng, X.; Teng, Y.; Shi, H.; Kuang, J.; Xiao, Z.; Wang, W.; Jiang, C.; Guo, W.; Ren, N. Constructing effective and low-toxic removal of combined contaminants by intimately coupled Z-scheme heterojunction photocatalysis and biodegradation system. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2025, 365, 124909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huang, H.; Xue, W.; Sun, K.; Song, X.; Wu, C.; Nie, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, C.; Pan, Y.; et al. Self-adaptive dual-metal-site pairs in metal-organic frameworks for selective CO2 photoreduction to CH4. Nat. Catal. 2021, 4, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.N.; Anand, R.; Zafari, M.; Ha, M.; Kim, K.S. Progress in Single/Multi Atoms and 2D-Nanomaterials for Electro/Photocatalytic Nitrogen Reduction: Experimental, Computational and Machine Leaning Developments. Adv. Energy Mater. 2024, 14, 2304106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakshinamoorthy, A.; Li, Z.; Yang, S.; Garcia, H. Metal–organic framework heterojunctions for photocatalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 3002–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Bao, L.; Pan, Y.; Du, J.; Wang, W. Interface reconstruction of MXene-Ti3C2 doped CeO2 nanorods for remarked photocatalytic ammonia synthesis. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 675, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, Y.; Zhou, A.; Yao, Y.; Lim, S.Y.; Li, J.-R.; Zhang, W. Suppressing hydrogen evolution for high selective CO2 reduction through surface-reconstructed heterojunction photocatalyst. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 286, 119876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, Y.; Mao, H.; Yang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Z.; Cao, Y.; Yang, S.; Peng, F. The photo-decomposition and self-restructuring dynamic equilibrium mechanism of Cu2(OH)2CO3 for stable photocatalytic CO2 reduction. J. Energy Chem. 2024, 92, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Li, Y.; Sheng, B.; Zhang, W.; Wang, W.; Chen, C.; Li, J.; Sheng, H.; Zhao, J. Self-reconstruction of paddle-wheel copper-node to facilitate the photocatalytic CO2 reduction to ethane. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 310, 121320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Bhoyar, T.; Abraham, B.M.; Kim, D.J.; Pasupuleti, K.S.; Umare, S.S.; Vidyasagar, D.; Gedanken, A. Potassium Molten Salt-Mediated In Situ Structural Reconstruction of a Carbon Nitride Photocatalyst. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 18898–18906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; He, Y.; Wang, H.; Sun, Y.; Dong, F. Photo-Switchable Oxygen Vacancy as the Dynamic Active Site in the Photocatalytic NO Oxidation Reaction. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 14015–14025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, W.; Du, X.; Yang, Y.; Long, C.; Li, Y.; Hu, C.; Xu, R.; Tian, M.; Xie, J.; Wang, W.; et al. Oxygen Atom Coordinative Position Inducing Catalytic Sites Structure Reconstruction for Enhanced Photocatalytic H2 Evolution. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2400466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Wu, X.; Zhou, W.; Li, M.; Bi, S.; Tang, L.; Huang, H.; Tu, W.; Yuan, X.; Ang, E.H.; et al. Urea/Thiourea Imine Linkages Provide Accessible Holes in Flexible Covalent Organic Frameworks and Dominates Self-Adaptivity and Exciton Dissociation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 64, e202418830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.-N.; Cai, L.-X.; Cheng, P.-M.; Hu, S.-J.; Zhou, L.-P.; Sun, Q.-F. Photooxidase Mimicking with Adaptive Coordination Molecular Capsules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 16087–16094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.N.; Cai, L.X.; Hu, S.J.; Zhou, Y.F.; Zhou, L.P.; Sun, Q.F. An Organo-Palladium Host Built from a Dynamic Macrocyclic Ligand: Adaptive Self-Assembly, Induced-Fit Guest Binding, and Catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202209879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Xue, Y.; Liu, Z.; Lv, X.; Han, Q.; Zheng, G. Efficient Urea Electrosynthesis on a Cu3 Molecular Catalyst with Dynamically Adaptive Intercopper Spacings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 41956–41964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Sun, C.; Wang, Y. Photocatalytic Oxidation of Benzylamine by Cadmium-Based MOF Constructed with Flexible Carboxylic Acid. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 27, e202300575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.-J.; Lü, J.; Hong, M.; Cao, R. Metal–organic frameworks based on flexible ligands (FL-MOFs): Structures and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 5867–5895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinen, J.; Dubbeldam, D. On flexible force fields for metal–organic frameworks: Recent developments and future prospects. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2018, 8, e1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Jeoung, S.; Chung, Y.G.; Moon, H.R. Elucidation of flexible metal-organic frameworks: Research progresses and recent developments. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 389, 161–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebadi Amooghin, A.; Sanaeepur, H.; Ghomi, M.; Luque, R.; Garcia, H.; Chen, B. Flexible–robust MOFs/HOFs for challenging gas separations. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 505, 215660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, A.; Bhattacharya, B.; Haque, F.; Ghoshal, D. Structural Diversity in Six Mixed Ligand Zn(II) Metal–Organic Frameworks Constructed by Rigid and Flexible Dicarboxylates and Different N,N′ Donor Ligands. Cryst. Growth Des. 2017, 17, 6613–6624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senkovska, I.; Bon, V.; Mosberger, A.; Wang, Y.; Kaskel, S. Adsorption and Separation by Flexible MOFs. Adv. Mater. 2025, 2414724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Jiang, H.-L. A dynamic metal-organic framework photocatalyst. Nat. Chem. 2024, 16, 1580–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Jeppesen, H.S.; Schoekel, A.; Bönisch, N.; Xu, F.; Zhuang, R.; Huang, Q.; Senkovska, I.; Bon, V.; Heine, T.; et al. Photocatalytic Dehalogenation of Aryl Halides Mediated by the Flexible Metal–Organic Framework MIL-53(Cr). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202422776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Yang, F.; Qu, J.; Cai, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, C.M.; Hu, J. Recent Advances and Challenges in Efficient Selective Photocatalytic CO2 Methanation. Small 2024, 20, 2400700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Hussain, S.; Li, Q.; Yang, J. PdCu alloy anchored defective titania for photocatalytic conversion of carbon dioxide into methane with 100% selectivity. J. Energy Chem. 2024, 91, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wu, S.; Liu, D.; Ye, Z.; Wang, L.; Kan, M.; Ye, Z.; Khan, M.; Zhang, J. Engineering Spatially Adjacent Redox Sites with Synergistic Spin Polarization Effect to Boost Photocatalytic CO2 Methanation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 15538–15548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalathil, S.; Rahaman, M.; Lam, E.; Augustin, T.L.; Greer, H.F.; Reisner, E. Solar-Driven Methanogenesis through Microbial Ecosystem Engineering on Carbon Nitride. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202409192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Yang, T.; Dong, Y.; Ji, R.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, J.; Pan, C.; Zhu, Y. Stabilization of *OH intermediates for enhanced photocatalytic H2O oxidation to H2O2. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2025, 379, 125692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Z.-W.; Huang, Z.-J.; Li, L.-P.; Peng, X.-R.; Shang, M.-J.; Liao, P.-S.; Chao, H.-Y.; Ouyang, G.; Liu, G.-F. Boosting CH4 selectivity in CO2 electroreduction using a metallacycle-based porous crystal with biomimetic adaptive cavities. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 11948–11954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, B.; Gou, J.; Zheng, Y.; Pu, X.; Wang, Y.; Kidkhunthod, P.; Tang, Y. Coordination Chemistry of Large-Sized Yttrium Single-Atom Catalysts for Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2300381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Li, W.; Li, S.; Xu, S.; Lv, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Dai, L.; Wang, B.; Li, P. 2D Undulated Metal Hydrogen-Bonded Organic Frameworks with Self-Adaption Interlayered Sites for Highly Efficient C–C Coupling in the Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction. Nano-Micro Lett. 2025, 17, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, C.; Kim, T.W.; Yadav, R.K.; Baeg, J.-O.; Gole, V.; Singh, A.P. Flexible covalent porphyrin framework film: An emerged platform for photocatalytic C H bond activation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 544, 148938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, W.; He, Y. Direct visual observation of pedal motion-dependent flexibility of single covalent organic frameworks. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, R.; Sun, C.; Lin, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, S.; Li, L.; Guo, S. Biomimetic Interface with Dynamic Disulfide Bonds Boosts Durable Photoconversion of Diluted CO2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 38311–38319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).