Cobalt Nanoparticle-Modified Boron Nitride Nanobelts for Rapid Tetracycline Degradation via PMS Activation

Abstract

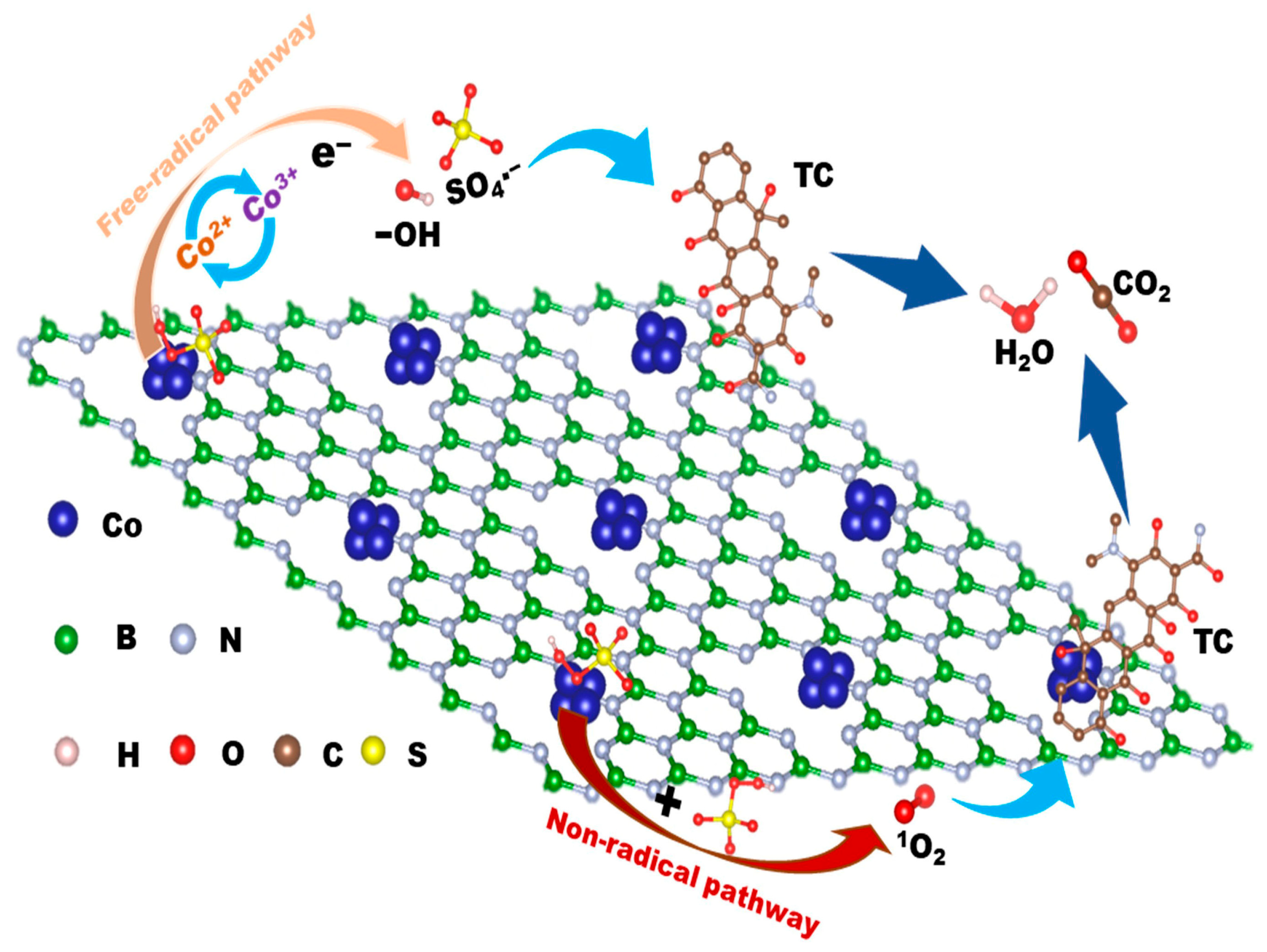

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

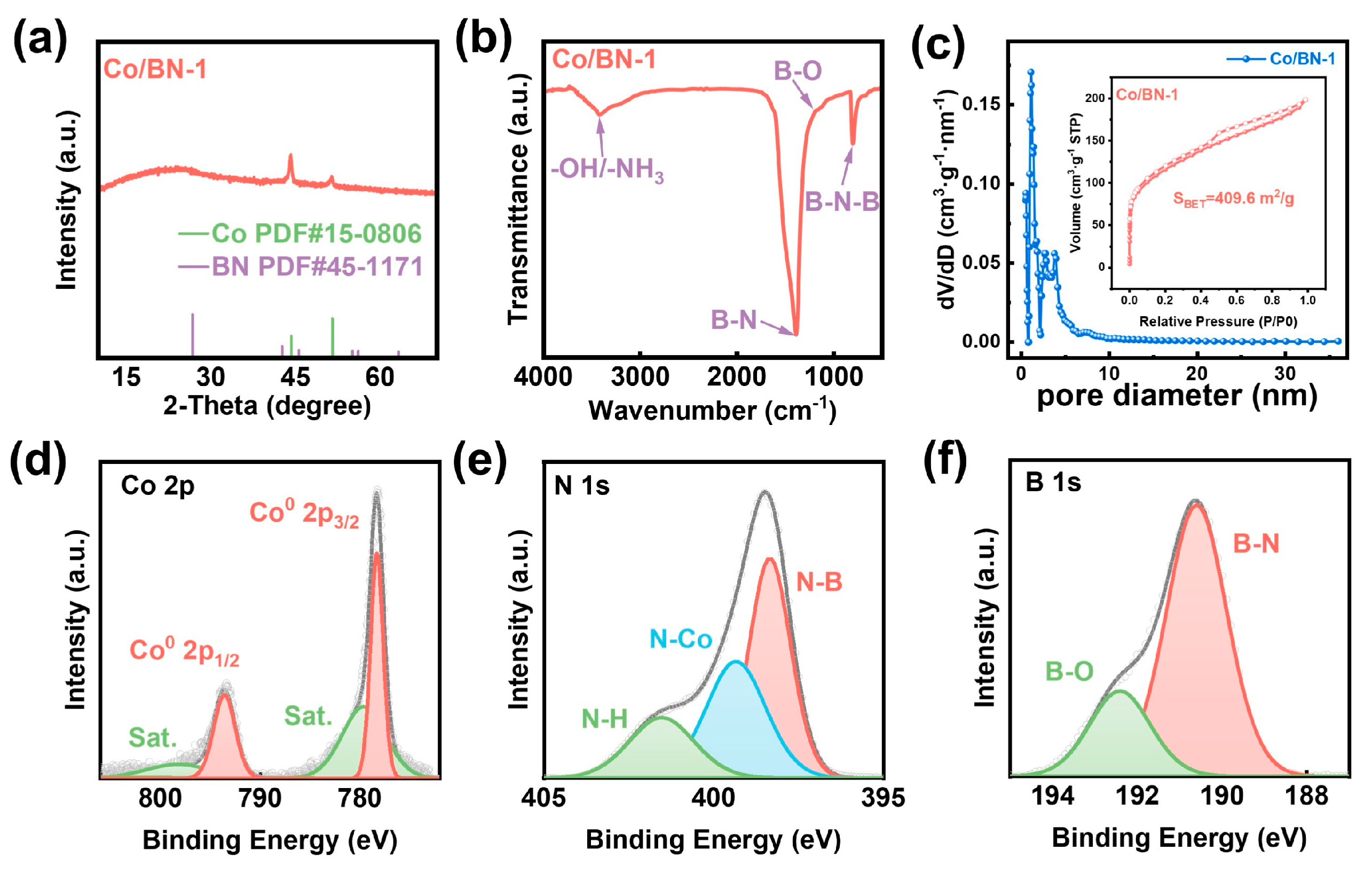

2.1. Structural and Compositional Analyses

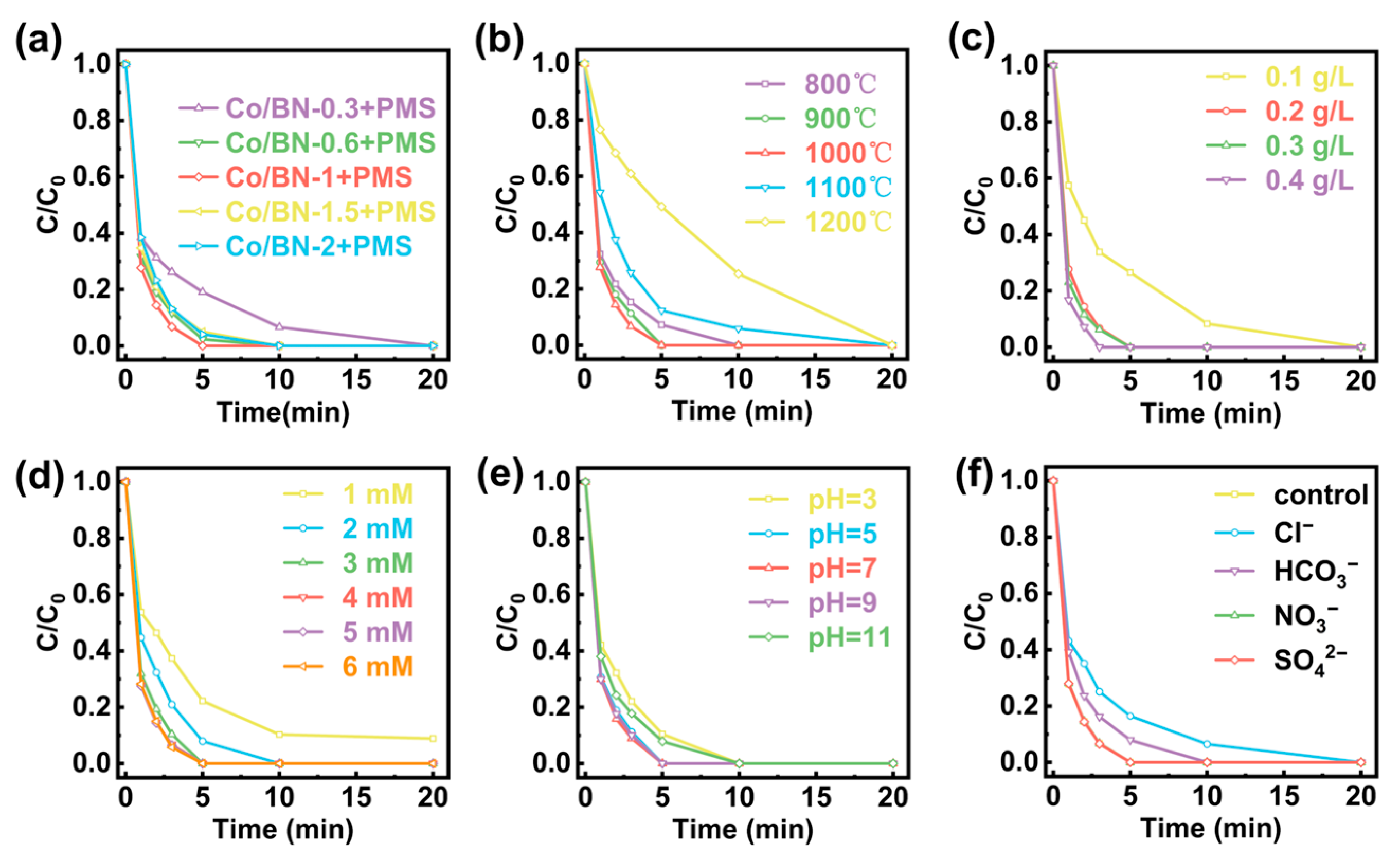

2.2. Degradation Performance of Co/BN Catalyst

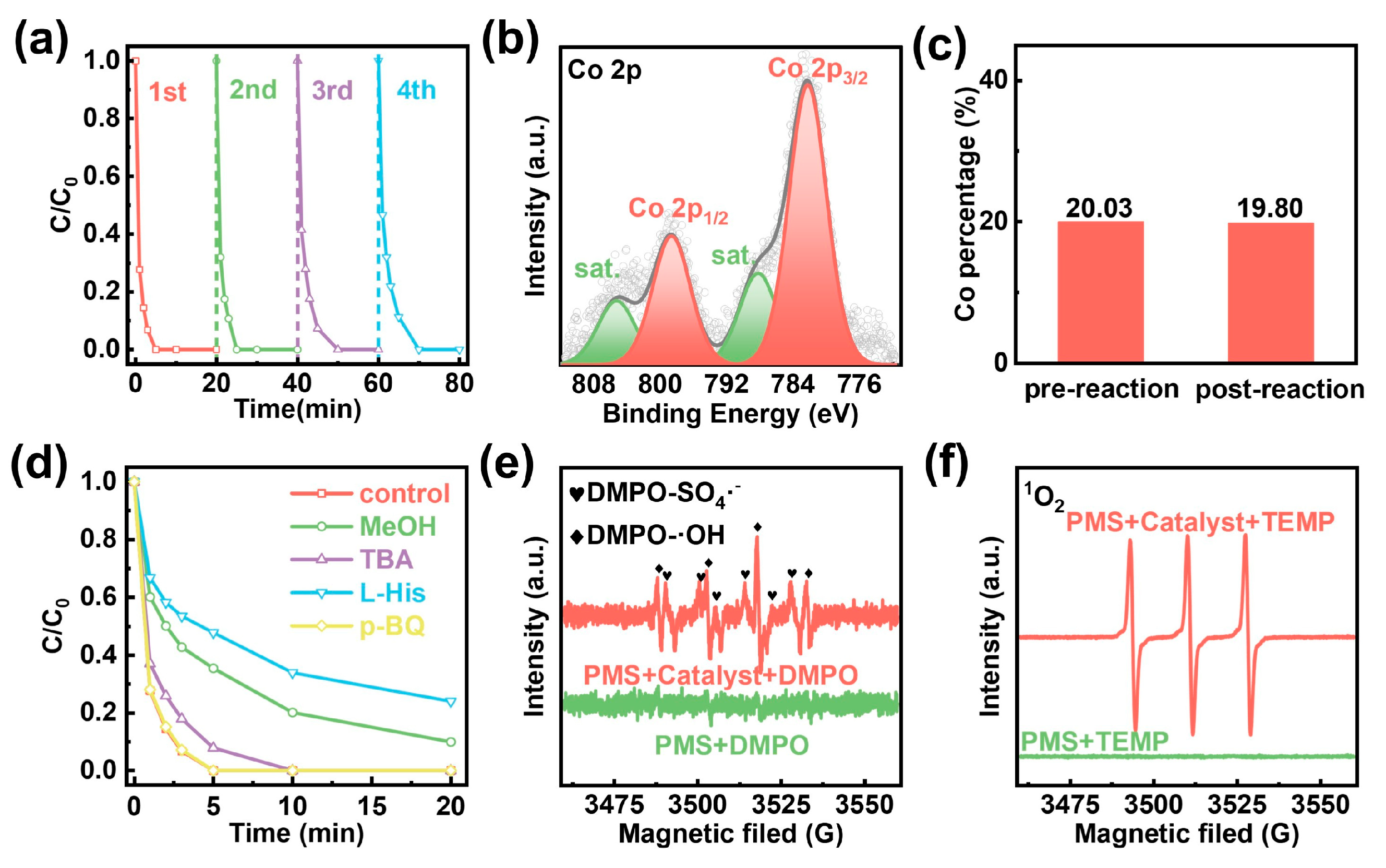

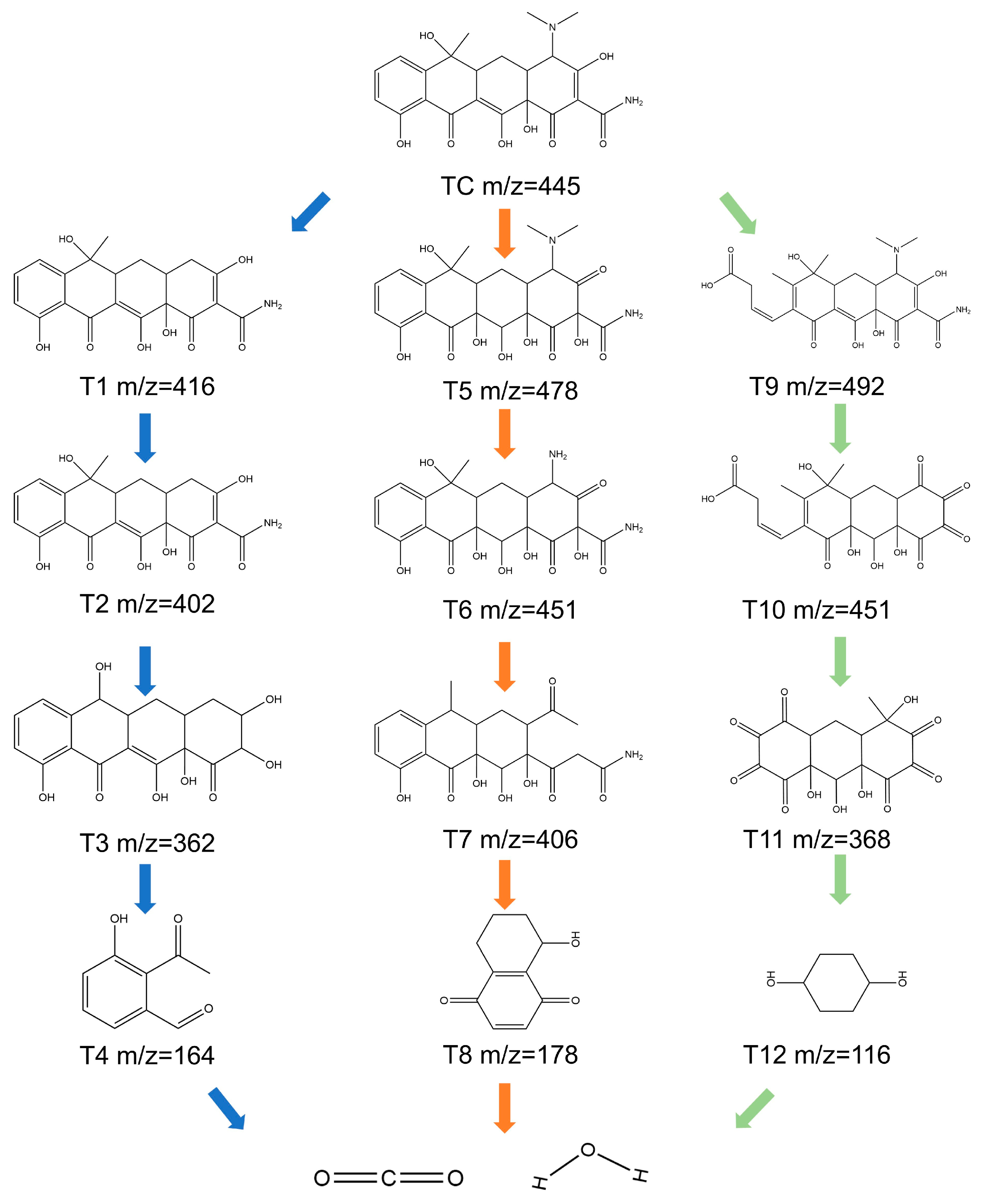

2.3. Degradation Mechanism

3. Experimental

3.1. Materials

3.2. Synthesis of Co/BN

3.3. Characterizations

3.4. Calibration of Tetracycline (TC)

3.5. Degradation Performance Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anjali, R.; Shanthakumar, S. Insights on the current status of occurrence and removal of antibiotics in wastewater by advanced oxidation processes. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 246, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodus, B.; O’Malley, K.; Dieter, G.; Gunawardana, C.; McDonald, W. Review of emerging contaminants in green stormwater infrastructure: Antibiotic resistance genes, microplastics, tire wear particles, PFAS, and temperature. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 906, 167195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatimazahra, S.; Latifa, M.; Laila, S.; Monsif, K. Review of hospital effluents: Special emphasis on characterization, impact, and treatment of pollutants and antibiotic resistance. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.-H.; Smith, S.M.; Wantala, K.; Kajitvichyanukul, P. Photocatalytic remediation of persistent organic pollutants (POPs): A review. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 8309–8337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ren, X.; Duan, X.; Sarmah, A.K.; Zhao, X. Remediation of environmentally persistent organic pollutants (POPs) by persulfates oxidation system (PS): A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 863, 160818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zango, Z.U.; Ibnaouf, K.H.; Lawal, M.A.; Aldaghri, O.; Wadi, I.A.; Modwi, A.; Zango, M.U.; Adamu, H. Recent trends in catalytic oxidation of tetracycline: An overview on advanced oxidation processes for pharmaceutical wastewater remediation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ren, W.; Ma, T.; Ren, N.; Wang, S.; Duan, X. Transformative Removal of Aqueous Micropollutants into Polymeric Products by Advanced Oxidation Processes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 4844–4851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaria, J.; Nidheesh, P.V. Comparison of hydroxyl-radical-based advanced oxidation processes with sulfate radical-based advanced oxidation processes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2022, 36, 100830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.-T.; Yan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, M. Nanoconfinement in advanced oxidation processes. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 53, 1197–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, A.; Li, M.; Liu, C.; Chee, T.-S.; Yan, Q.; Lei, L.; Xiao, C. Recovering palladium and gold by peroxydisulfate-based advanced oxidation process. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadm9311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, T.; Zhu, M.; Yan, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, P.; Shi, G.; Yue, D. Resourceful recovery of WC@Co for organic pollutants treatment via Fenton-like reaction. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 341, 126653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akçay, H.T.; Demir, A.; Özçifçi, Z.; Yumak, T.; Keleş, T. Treatment of wastewater containing organic pollutants in the presence of N-doped graphitic carbon and Co3O4/peroxymonosulfate. Carbon Lett. 2023, 33, 1445–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liang, X.; Liu, Z.; Huang, T.; Wang, S.; Yao, S.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wan, X.; Wang, Z.L.; et al. Self-powered electrochemical water treatment system for pollutant degradation and bacterial inactivation based on high-efficient Co(OH)2/Pt electrocatalyst. Nano Res. 2023, 16, 2192–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żółtowska, S.; Miñambres, J.F.; Piasecki, A.; Mertens, F.; Jesionowski, T. Three-dimensional commercial-sponge-derived Co3O4@C catalysts for effective treatments of organic contaminants. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, I.S.; Manikandan, V.; Patil, R.P.; Mahadik, M.A.; Chae, W.-S.; Chung, H.-S.; Choi, S.H.; Jang, J.S. Hydrogen-Treated TiO2 Nanorods Decorated with Bimetallic Pd–Co Nanoparticles for Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Pollutants and Bacterial Inactivation. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 1562–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Nasir Khan, M.; Kwame Klu, P.; Wang, C.; Zhang, W.; Luo, R.; Zhang, M.; Qi, J.; Sun, X.; Wang, L.; Li, J. Metal-organic framework-derived hollow Co3O4/carbon as efficient catalyst for peroxymonosulfate activation. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 363, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Tang, J.; Kong, L.; Lu, W.; Natarajan, V.; Zhu, F.; Zhan, J. Cobalt doped g-C3N4 activation of peroxymonosulfate for monochlorophenols degradation. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 360, 1213–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jiang, H.; Luo, J.; Zhang, K.; Wan, Y.; Li, C.; Song, J.; Jin, X.; Yang, P.; Jia, H. NaOH-treated waste allochroic silica gel as an efficient catalyst for the degradation of tetracycline hydrochloride by peroxymonosulfate activation in a continuous flow fixed-bed system. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 70, 107109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, M.; Yan, J.; Fan, G.; Liu, Y.; Chai, B.; Wang, C.; Song, G. Built-in electric field mediated peroxymonosulfate activation over biochar supported-Co3O4 catalyst for tetracycline hydrochloride degradation. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 444, 136589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Wang, X.; Pang, H.; Zhang, R.; Song, W.; Fu, D.; Hayat, T.; Wang, X. Boron nitride-based materials for the removal of pollutants from aqueous solutions: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 333, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.-G.; Nam, S.-N.; Jang, M.; Park, C.M.; Her, N.; Sohn, J.; Cho, J.; Yoon, Y. Boron nitride-based nanomaterials as adsorbents in water: A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 288, 120637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Bai, C.; An, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, F.; Huang, Y.; Qu, M.; Yu, Y. Biocompatible porous boron nitride nano/microrods with ultrafast selective adsorption for dyes. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 104797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.X.; Zhang, D.J.; Liu, C.B. Theoretical Study of Adsorption of Chlorinated Phenol Pollutants on Co-Doped Boron Nitride Nanotubes. Acta Phys. Chim. Sin. 2015, 31, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Jin, X.; Fan, Y.; Lin, J.; Li, J.; Ren, C.; Xu, X.; Liu, D.; Hu, L.; Meng, F.; et al. Boron Nitride Quasi-Nanoscale Fibers: Controlled Synthesis and Improvement on Thermal Properties of PHA Polymer. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2014, 63, 794–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, D.; Li, Q.; Chen, C.; Chen, Z.; Song, P.; Hao, J.; Li, Y.; Fakhrhoseini, S.; Naebe, M.; et al. Lightweight, Superelastic Yet Thermoconductive Boron Nitride Nanocomposite Aerogel for Thermal Energy Regulation. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 7860–7870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Zhang, H.; Song, Q.; Liu, Z.; Xia, J.; Yan, B.; Meng, X.; Jiang, Z.; Lou, X.W.; Lee, C.-S. Modulating Charge Separation of Oxygen-Doped Boron Nitride with Isolated Co Atoms for Enhancing CO2-to-CO Photoreduction. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2303287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Liu, Q.; Huang, C.; Qiu, X. One-step synthesis of magnetically recyclable Co@BN core–shell nanocatalysts for catalytic reduction of nitroarenes. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 35451–35459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zheng, S.; Luo, Y.; Pang, H. Synthesis of confining cobalt nanoparticles within SiOx/nitrogen-doped carbon framework derived from sustainable bamboo leaves as oxygen electrocatalysts for rechargeable Zn-air batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 401, 126005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Chen, C.; Zhang, M.; Lin, L.; Ye, X.; Lin, S.; Antonietti, M.; Wang, X. Carbon-doped BN nanosheets for metal-free photoredox catalysis. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, X.; Zhu, Z.; Hu, W.; Zhang, H.; Xu, J.; Hu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, M.; Zhang, H.; et al. Single-atom Co embedded in BCN matrix to achieve 100% conversion of peroxymonosulfate into singlet oxygen. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 300, 120759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Yu, P.; Sun, Y.; Li, X.; Xu, Y. Enhanced electron transfer-based nonradical activation of peroxymonosulfate by CoNx sites anchored on carbon nitride nanotubes for the removal of organic pollutants. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 466, 143155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Fang, Y.; Wang, W.; Nie, G. Efficient Activation of Peroxymonosulfate to Produce Singlet Oxygen (1O2) for Degradation of Tetracycline over Cu-Co Nanocomposite Catalyst. Top. Catal. 2024, 67, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cui, K.; Cui, M.; Liu, T.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y.; Nie, X.; Xu, Z.; Li, C.-X. Insight into the degradation of tetracycline hydrochloride by non-radical-dominated peroxymonosulfate activation with hollow shell-core Co@NC: Role of cobalt species. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 289, 120662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Wang, G.; Li, P.; Shu, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Meng, Z.; Zhu, W. Oxygen Vacancy-Enhanced Electrocatalytic Degradation of Tetracycline over a Co3O4–La2O3/Peroxymonosulfate System. ACS ES T Water 2024, 4, 1411–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, B.; Zheng, L.; Adeboye, A.; Li, F. Defect- and nitrogen-rich porous carbon embedded with Co NPs derived from self-assembled Co-ZIF-8 @ anionic polyacrylamide network as PMS activator for highly efficient removal of tetracycline hydrochloride from water. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 443, 136439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Xiao, P. Catalytic degradation of tetracycline using peroxymonosulfate activated by cobalt and iron co-loaded pomelo peel biochar nanocomposite: Characterization, performance and reaction mechanism. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 287, 120533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-F.; Wang, L.-F.; Gao, S.-J.; Yu, T.-L.; Li, Q.-F.; Wang, J.-W. Facile Fabrication of Co-Doped Porous Carbon from Coal Hydrogasification Semi-Coke for Efficient Microwave Absorption. Molecules 2024, 29, 4633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Yu, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, J.; Sheng, J. Annealing temperature regulates the maneuverability of cobalt spinel sites decorated on halloysite nanotubes: Dynamic restructuring and catalytic performance. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 42798–42808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; O’Shea, K.E. Selective oxidation of H1-antihistamines by unactivated peroxymonosulfate (PMS): Influence of inorganic anions and organic compounds. Water Res. 2020, 186, 116401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, F.; Liu, Y.; Feng, L.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, L.; Qi, F.; Liu, C. Carbonized polyaniline activated peroxymonosulfate (PMS) for phenol degradation: Role of PMS adsorption and singlet oxygen generation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 286, 119921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obiedallah, F.M.; Abo Zeid, E.F.; Abu-Sehly, A.-H.; Aboraia, A.M.; El-Ghaffar, S.A.; El-Aal, M.A. Hydrothermal synthesis of CuWO4/Co3O4 nanocomposites for water remediation and antibacterial activity applications. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 13478–13492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, S.; Lian, X.; Dong, S.; Li, H.; Xu, K. Efficient activation of peroxydisulfate by g-C3N4/Bi2MoO6 nanocomposite for enhanced organic pollutants degradation through non-radical dominated oxidation processes. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 607, 684–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Cao, J.; Yang, Z.; Xiong, W.; Xu, Z.; Song, P.; Jia, M.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, H.; Wu, A. Fabrication of Fe-doped cobalt zeolitic imidazolate framework derived from Co(OH)2 for degradation of tetracycline via peroxymonosulfate activation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 259, 118059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, B.; Wang, S.; Li, X.; Wang, C.; Liu, B.; Han, F.; Xu, Y.; Yu, P.; Sun, Y. Tetracycline degradation by peroxymonosulfate activated with CoNx active sites: Performance and activation mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 431, 133477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, T.; Yang, M.; Hu, C. CoO anchored on boron nitride nanobelts for efficient removal of water contaminants by peroxymonosulfate activation. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 430, 132915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, B.; Jiang, W.; Zhou, T.; Ma, Y.; Che, G.; Liu, C. Superhydrophilic N,S,O-doped Co/CoO/Co9S8@carbon derived from metal-organic framework for activating peroxymonosulfate to degrade sulfamethoxazole: Performance, mechanism insight and large-scale application. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 446, 137361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zou, H.; Ma, H.; Ko, J.; Sun, W.; Andrew Lin, K.; Zhan, S.; Wang, H. Highly efficient activation of peroxymonosulfate by MOF-derived CoP/CoOx heterostructured nanoparticles for the degradation of tetracycline. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 430, 132816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Li, Y.; Zou, Y.; Lin, L.; Li, B.; Li, X.-y. Transition metal single-atom embedded on N-doped carbon as a catalyst for peroxymonosulfate activation: A DFT study. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 437, 135428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dai, P.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhao, H.; Cheng, L.; Xu, L.; Zhang, Z. Cobalt Nanoparticle-Modified Boron Nitride Nanobelts for Rapid Tetracycline Degradation via PMS Activation. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1117. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121117

Dai P, Wang X, Zhao Y, Chen H, Zhao H, Cheng L, Xu L, Zhang Z. Cobalt Nanoparticle-Modified Boron Nitride Nanobelts for Rapid Tetracycline Degradation via PMS Activation. Catalysts. 2025; 15(12):1117. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121117

Chicago/Turabian StyleDai, Pengcheng, Xiangjian Wang, Yongxin Zhao, Huishan Chen, Hui Zhao, Longzhen Cheng, Longxi Xu, and Zeyu Zhang. 2025. "Cobalt Nanoparticle-Modified Boron Nitride Nanobelts for Rapid Tetracycline Degradation via PMS Activation" Catalysts 15, no. 12: 1117. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121117

APA StyleDai, P., Wang, X., Zhao, Y., Chen, H., Zhao, H., Cheng, L., Xu, L., & Zhang, Z. (2025). Cobalt Nanoparticle-Modified Boron Nitride Nanobelts for Rapid Tetracycline Degradation via PMS Activation. Catalysts, 15(12), 1117. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121117