A Review of Simultaneous Catalytic Removal of NOx and VOCs: From Mechanism to Modification Strategy

Abstract

1. Introduction

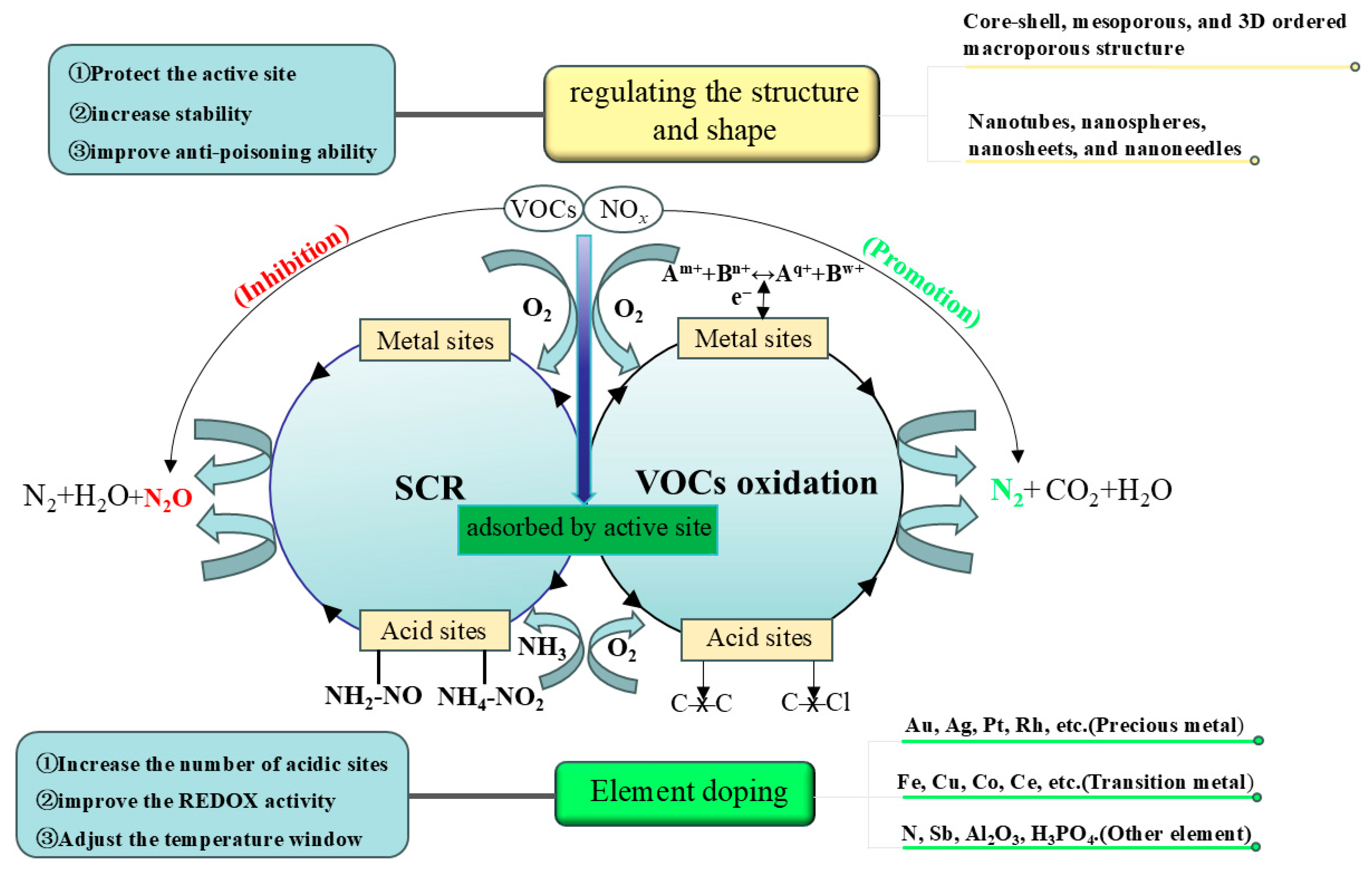

2. Reaction and Poisoning Mechanism

2.1. Mechanism of Simultaneous Removal of NOx and VOCs

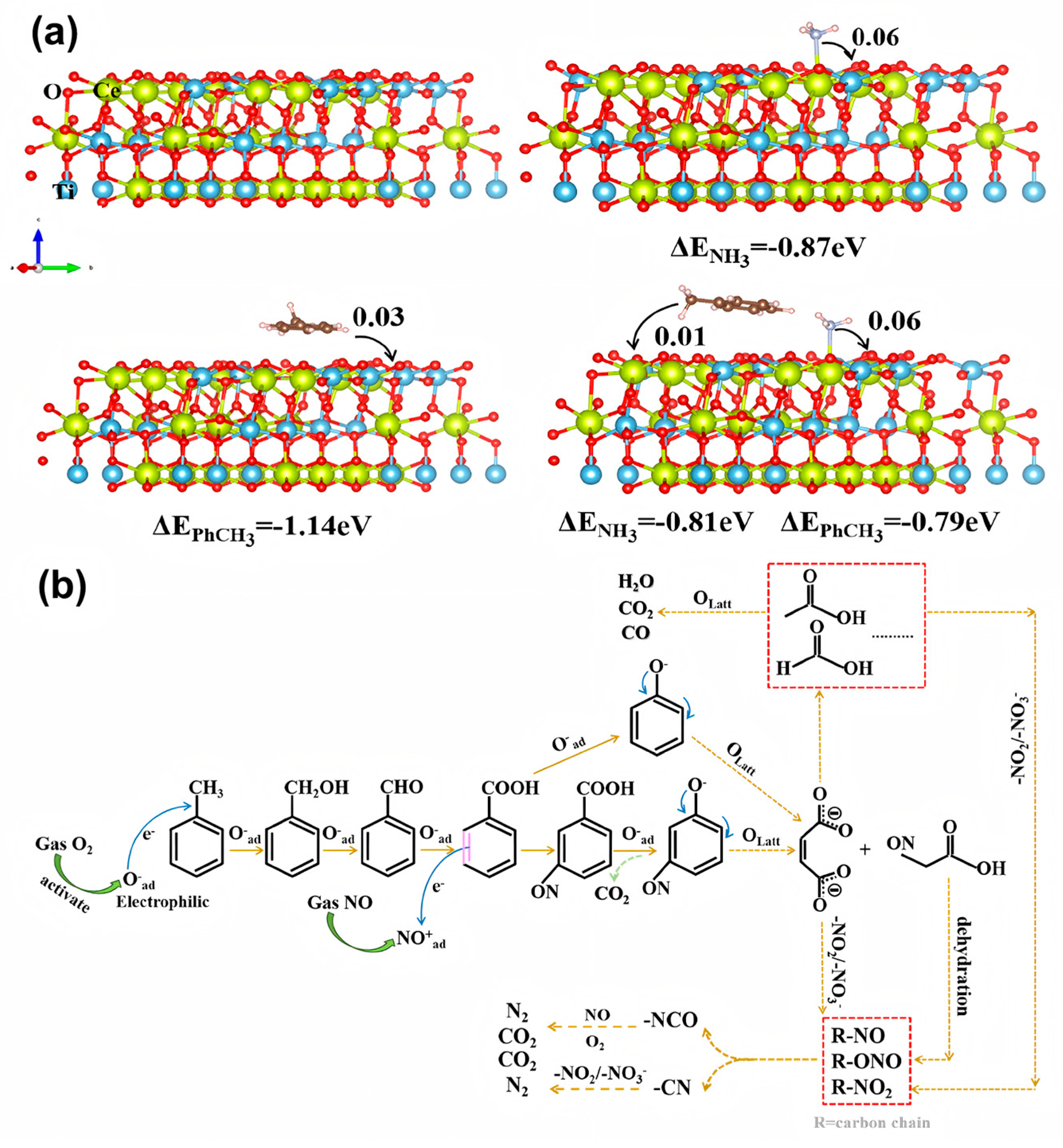

2.1.1. Mechanism of Simultaneous Removal of NOx and Toluene

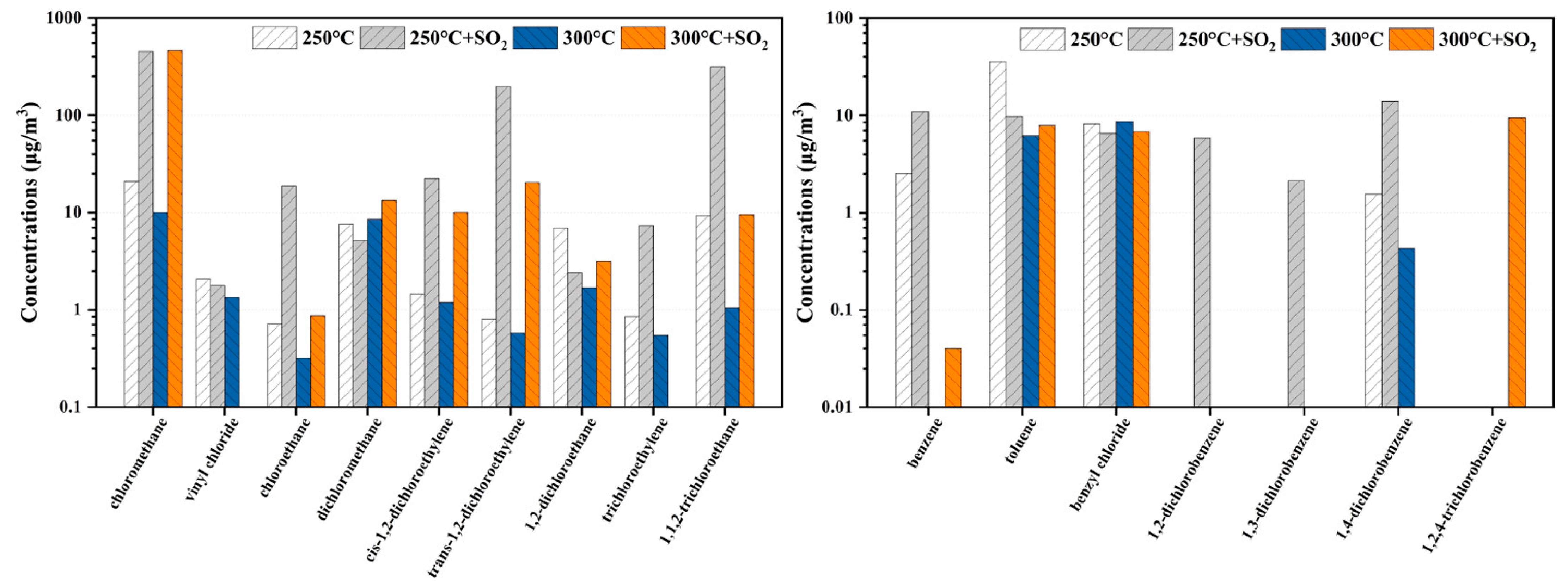

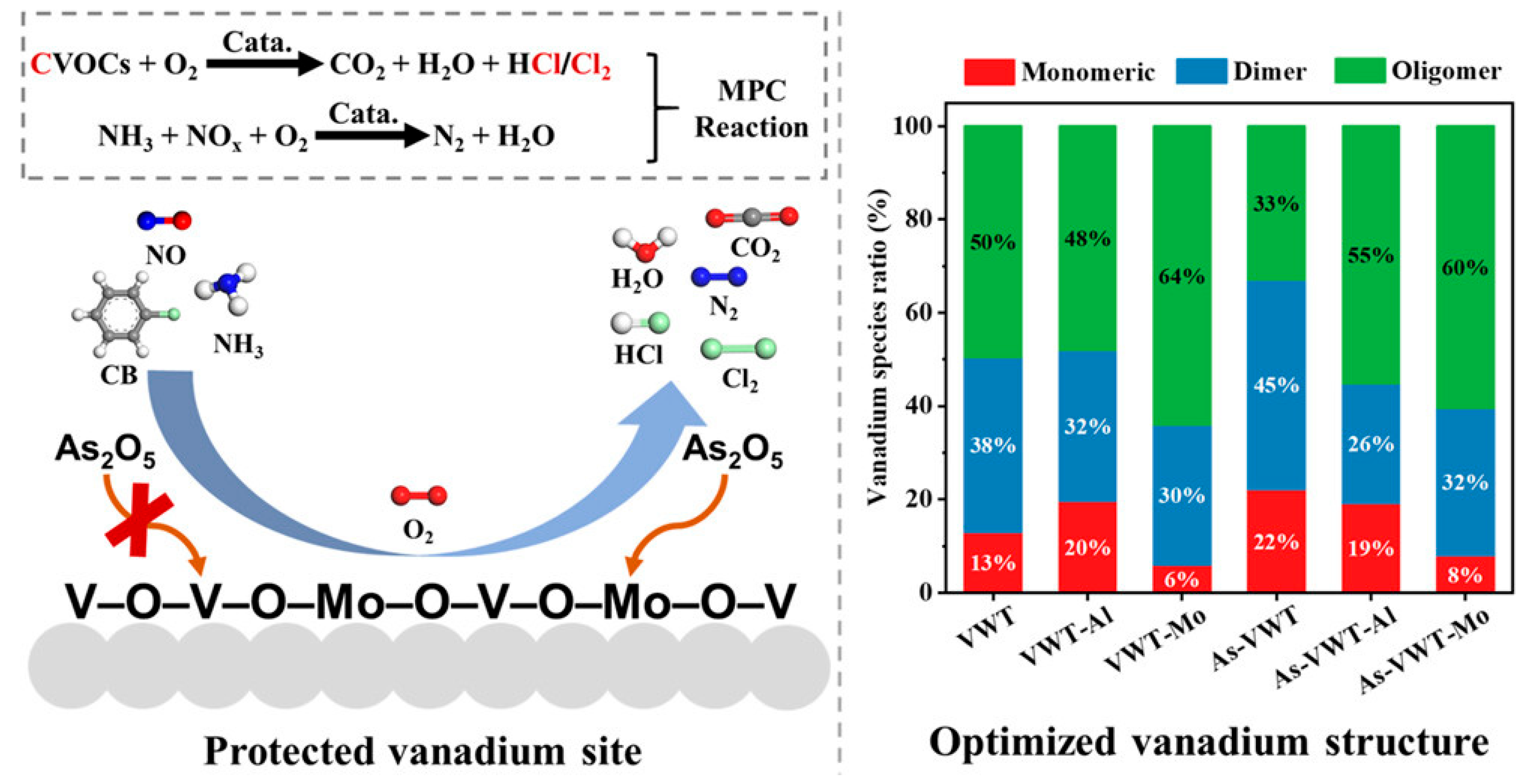

2.1.2. Mechanism of Simultaneous Removal of NOx and CB

2.2. The Role of Active Site

2.2.1. Acid Sites

2.2.2. Metal Sites and Oxygen Vacancy

2.3. Poisoning Mechanisms

2.3.1. Sulfur Poisoning

| Catalyst | Reactant Composition | Space Velocity (mL·g−1·h−1) | Conversion (Without SO2) | Conversion (with SO2) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mn-Fe | Toluene 50 ppm, NO 500 ppm, SO2 300 ppm, 5% O2, 10% H2O | 24,000 | Toluene: 100% (230 °C) NO: 89% (230 °C) | Toluene: 56% (230 °C) NO: 0% (230 °C) | [40] |

| MnOx-CeO2 | CB 50 ppm, NO 500 ppm, NH3 500 ppm, 10%O2, 5%H2O | 60,000 | CB: >90% (230 °C) NOx: >90% (250 °C) | Inactivation | [51] |

| MnO2 | Toluene 100 ppm, NO 200 ppm, SO2 1000 ppm, 20%O2 | 24,000 | Toluene: 100% (310 °C) NO: 89% (310 °C) | Toluene: 10% (310 °C) NO: 5% (310 °C) | [39] |

| MnCe/TNT | Toluene 50 ppm, NO 500 ppm, NH3 500 ppm, SO2 250 ppm, 10% O2, 10% H2O | 60,000 | Toluene: >90% (200 °C) NO: >90% (250 °C) | Toluene: 10% (200 °C) NO: 60% (250 °C) | [81] |

| PdV/TiO2 | CB 600 ppm, NO 600 ppm, NH3 600 ppm, SO2 200 ppm, 10%O2, 5%H2O | 30,000 | CB: 90% (400 °C) NOx: 80% (300 °C) | CB: 80% (400 °C) NOx: 70% (300 °C) | [49] |

| VWT | CB 100 ppm, 600 ppm NH3,600 ppm NO, 100 ppm SO2, 5 vol % O2 | 40,000 | CB: 90% (250 °C) NOx: / | CB: 80% (250 °C) NOx: / | [78] |

| MnOx | Toluene 100 ppm, NO 600 ppm, NH3 600 ppm, SO2, 200 ppm, 5% O2, 5% H2O | 15,000 | Toluene: / NO: 100% (200 °C) | Toluene: / NO: 60% (200 °C) | [82] |

2.3.2. Heavy Metal Poisoning

2.3.3. Other Effects

3. Strategies for Improving the Activity and Poisoning Resistance

3.1. Doping of Catalyst

3.1.1. Noble Metal

3.1.2. Transition Metals

3.1.3. Other Metals

3.1.4. Nonmetallic Elements

3.2. Regulating the Structure

3.2.1. Core–Shell Structure

3.2.2. Pore Structure

3.3. Regulating the Shape

4. Summary and Perspective

- (1)

- From Model Systems to Realistic Multi-Pollutant: Most current studies focus on the interaction between NOₓ and a single model VOC (e.g., toluene or chlorobenzene). The reaction network, synergistic pathways, and competitive adsorption landscapes in complex flue gas containing multiple VOCs (e.g., aromatics, oxygenates, and chlorinated compounds) remain poorly understood. Future research must employ more sophisticated experimental and theoretical approaches to decipher these complex interactions.

- (2)

- Precision in Active Site Engineering and Poisoning Resistance: While doping and structural design have proven effective, a more precise strategy is needed. The optimal dosage of dopants and the spatial architecture of multi-functional sites (e.g., physically separating SCR-active sites from oxidation-active sites to mitigate competitive adsorption) require finer control. Furthermore, a clearer distinction between reversible and irreversible deactivation pathways for different poisons (SO2, Cl, Pb, As) is crucial for developing more targeted, robust, and economically viable non-noble metal catalysts.

- (3)

- Bridging the Material–Reactor Gap for Industrial Translation: The inherent mismatch in optimal temperature windows for SCR and VOC oxidation remains a significant engineering hurdle. Future efforts should tightly integrate catalyst design with innovative reactor engineering, such as dynamic or multi-stage reactor systems (e.g., circulating fluidized beds, rotary reactors), to create spatially or temporally distinct zones for each reaction. Concurrently, establishing feasible in situ regeneration protocols and developing predictive catalyst lifetime models are indispensable steps toward successful industrial implementation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chaudary, A.; Mubasher, M.M.; Ul Qounain, S.W. Modeling the Strategies to Control the Impact of Photochemical Smog on Human Health. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Innovative Computing (ICIC), Lahore, Pakistan, 9–10 November 2021; IEEE: Lahore, Pakistan, 2021; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Li, G.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; An, T. Reactor Characterization and Primary Application of a State of Art Dual-Reactor Chamber in the Investigation of Atmospheric Photochemical Processes. J. Environ. Sci. 2020, 98, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Ge, M.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, K.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Z.; et al. A Large-Scale Outdoor Atmospheric Simulation Smog Chamber for Studying Atmospheric Photochemical Processes: Characterization and Preliminary Application. J. Environ. Sci. 2021, 102, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Lin, F.; Wang, Z.; Liu, P.; Tang, H.; He, Y.; Cen, K. Low Temperature Catalytic Ozonation of Toluene in Flue Gas over Mn-Based Catalysts: Effect of Support Property and SO2/Water Vapor Addition. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 266, 118662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yu, S.; Shang, Y. Toward Separation at Source: Evolution of Municipal Solid Waste Management in China. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2020, 14, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Song, M.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Hui, L.; Kong, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Qu, Y.; An, J.; et al. Characterization and Sources of Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) and Their Related Changes during Ozone Pollution Days in 2016 in Beijing, China. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 257, 113599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, L.; Liu, X.; Tan, Q.; Feng, M.; An, J.; Qu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, M. Characteristics, Source Apportionment and Contribution of VOCs to Ozone Formation in Wuhan, Central China. Atmos. Environ. 2018, 192, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Cheng, Y.; He, D.; Yang, E.-H. Review of Leaching Behavior of Municipal Solid Waste Incineration (MSWI) Ash. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 668, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, X.; Gao, C.; Wang, B.; Huang, X.; Peng, Y.; Li, J.; Lu, C.; Crittenden, J. Multipollutant Control (MPC) of Flue Gas from Stationary Sources Using SCR Technology: A Critical Review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 2743–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braguglia, C.M.; Bagnuolo, G.; Gianico, A.; Mininni, G.; Pastore, C.; Mascolo, G. Preliminary Results of Lab-Scale Investigations of Products of Incomplete Combustion during Incineration of Primary and Mixed Digested Sludge. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 4585–4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaß, U.; Fermann, M.; Bröker, G. The European Dioxin Air Emission Inventory Project—Final Results. Chemosphere 2004, 54, 1319–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Liu, Q.-Y.; Zheng, J.; Li, Y.-H.; Xiang, S.; Sun, X.-J.; He, X.-S. Volatile and Semi-Volatile Organic Compounds in Landfill Gas: Composition Characteristics and Health Risks. Environ. Int. 2023, 174, 107886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coggon, M.M.; Gkatzelis, G.I.; McDonald, B.C.; Gilman, J.B.; Schwantes, R.H.; Abuhassan, N.; Aikin, K.C.; Arend, M.F.; Berkoff, T.A.; Brown, S.S.; et al. Volatile Chemical Product Emissions Enhance Ozone and Modulate Urban Chemistry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2021, 118, e2026653118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Liu, C.; Ma, X.; Zhou, Z.; Lu, J. Review on NH3-SCR for Simultaneous Abating NOx and VOCs in Industrial Furnaces: Catalysts’ Composition, Mechanism, Deactivation and Regeneration. Fuel Process. Technol. 2023, 247, 107773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debecker, D.P.; Bouchmella, K.; Delaigle, R.; Eloy, P.; Poleunis, C.; Bertrand, P.; Gaigneaux, E.M.; Mutin, P.H. One-Step Non-Hydrolytic Sol–Gel Preparation of Efficient V2O5-TiO2 Catalysts for VOC Total Oxidation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2010, 94, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Peng, J.; Ge, R.; Wu, S.; Zeng, K.; Huang, H.; Yang, K.; Sun, Z. Research Progress on Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) Catalysts for NO Removal from Coal-Fired Flue Gas. Fuel Process. Technol. 2022, 236, 107432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Shi, J.-W.; Gao, C.; Gao, G.; Wang, B.; Wang, Y.; He, C.; Niu, C. Gd-Modified MnOx for the Selective Catalytic Reduction of NO by NH3: The Promoting Effect of Gd on the Catalytic Performance and Sulfur Resistance. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 348, 820–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, X.; Meng, Q.; Liu, J.; Jiang, W.; Pattisson, S.; Wu, Z. Catalytic Oxidation of Chlorinated Organics over Lanthanide Perovskites: Effects of Phosphoric Acid Etching and Water Vapor on Chlorine Desorption Behavior. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 884–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Si, W.; Li, X.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; Crittenden, J.; Hao, J. Investigation of the Poisoning Mechanism of Lead on the CeO2—WO3 Catalyst for the NH3–SCR Reaction via in Situ IR and Raman Spectroscopy Measurement. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 9576–9582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Shen, K.; Wu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Xiao, R.; Wang, B.; Zhang, S. SO2 Poisoning Mechanism of the Multi-Active Center Catalyst for Chlorobenzene and NOx Synergistic Degradation at Dry and Humid Environments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 13186–13197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Bian, Y.; Shi, Q.; Wang, J.; Yuan, P.; Shen, B. A Review of Synergistic Catalytic Removal of Nitrogen Oxides and Chlorobenzene from Waste Incinerators. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H. Recent Advances in Simultaneous Removal of NOx and VOCs over Bifunctional Catalysts via SCR and Oxidation Reaction. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 906, 167553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Cai, S.; Gao, M.; Hasegawa, J.; Wang, P.; Zhang, J.; Shi, L.; Zhang, D. Selective Catalytic Reduction of NOx with NH3 by Using Novel Catalysts: State of the Art and Future Prospects. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 10916–10976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piumetti, M.; Fino, D.; Russo, N. Mesoporous Manganese Oxides Prepared by Solution Combustion Synthesis as Catalysts for the Total Oxidation of VOCs. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2015, 163, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Ma, S.; Gao, B.; Bi, F.; Qiao, R.; Yang, Y.; Wu, M.; Zhang, X. A Systematic Review of Intermediates and Their Characterization Methods in VOCs Degradation by Different Catalytic Technologies. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 314, 123510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Fu, K.; Yu, Z.; Su, Y.; Han, R.; Liu, Q. Oxygen Vacancies in a Catalyst for VOCs Oxidation: Synthesis, Characterization, and Catalytic Effects. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 14171–14186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Yin, R.; Yang, W.; Wang, G.; Si, W.; Peng, Y.; Li, J. Interaction Mechanism for Simultaneous Elimination of Nitrogen Oxides and Toluene over the Bifunctional CeO2–TiO2 Mixed Oxide Catalyst. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 4467–4476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Li, C.; Li, S.; Du, X.; Zhang, J.; Huang, Y. Simultaneous Removal of Hg0 and NO in Simulated Flue Gas on Transition Metal Oxide M′ (M′ = Fe2O3, MnO2, and WO3) Doping on V2O5/ZrO2-CeO2 Catalysts. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 483, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Q. The Influencing Mechanism of NH3 and NOx Addition on the Catalytic Oxidation of Toluene over Mn2Cu1Al1Ox Catalyst. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 348, 131152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, L.; Wang, Y. Al2O3-Modified CuO-CeO2 Catalyst for Simultaneous Removal of NO and Toluene at Wide Temperature Range. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 397, 125419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Lu, P.; Peng, Y.; Li, J.; Huang, H. Impact of NOx and NH3 Addition on Toluene Oxidation over MnOx-CeO2 Catalyst. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 416, 125939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertinchamps, F.; Treinen, M.; Eloy, P.; Dos Santos, A.-M.; Mestdagh, M.M.; Gaigneaux, E.M. Understanding the Activation Mechanism Induced by NOx on the Performances of VOx/TiO2 Based Catalysts in the Total Oxidation of Chlorinated VOCs. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2007, 70, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Ye, L.; Yan, X.; Chen, X.; Fang, P.; Chen, D.; Chen, D.; Cen, C. N2O Inhibition by Toluene over Mn-Fe Spinel SCR Catalyst. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 414, 125468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, P.; Ye, L.; Yan, X.; Chen, D.; Chen, D.; Chen, X.; Fang, P.; Cen, C. Performance of Toluene Oxidation over MnCe/HZSM-5 Catalyst with the Addition of NO and NH3. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 567, 150836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aissat, A.; Courcot, D.; Cousin, R.; Siffert, S. VOCs Removal in the Presence of NOx on Cs–Cu/ZrO2 Catalysts. Catal. Today 2011, 176, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liao, W.; Cai, N.; Zhang, H.; Yang, H.; Shao, J.; Zhang, S. Experiment and Mechanism Investigation on Simultaneously Catalytic Reduction of NOx and Oxidation of Toluene over MnOx/Cu-SAPO-34. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 611, 155628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Chen, Z.; Ma, M.; Guo, T.; Ling, X.; Zheng, Y.; He, C.; Chen, J. Mutual Inhibition Mechanism of Simultaneous Catalytic Removal of NO and Toluene on Mn-Based Catalysts. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 607, 1189–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Lu, P.; Xianhui, Y.; Huang, H. Boosting Simultaneous Catalytic Removal of NOx and Toluene via Cooperation of Lewis Acid and Oxygen Vacancies. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2023, 331, 122696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, P.; Lin, F.; Zhu, Y.; He, Y.; Cen, K. Interplay Effect on Simultaneous Catalytic Oxidation of NO and Toluene over Different Crystal Types of MnO2 Catalysts. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2021, 38, 5433–5441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Shen, B.; Lu, F.; Peng, X. Highly Efficient Mn-Fe Bimetallic Oxides for Simultaneous Oxidation of NO and Toluene: Performance and Mechanism. Fuel 2023, 332, 126143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Yu, C.; Fang, H.; Hou, D.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, F.; Xiong, J.; Dan, J.; He, D. MnOx Catalysts with Different Morphologies for Low Temperature Synergistic Removal of NOx and Toluene: Structure–Activity Relationship and Mutual Inhibitory Effects. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, L.; Zhu, T.; Ning, R. Catalytic Oxidation of Chlorobenzene over Noble Metals (Pd, Pt, Ru, Rh) and the Distributions of Polychlorinated by-Products. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 363, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Xu, M.; Lu, Y.; Yang, B.; Ji, W.; Xue, Z.; Dai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Xu, H. Simultaneous Catalytic Removal of NO, Mercury and Chlorobenzene over WCeMnOx/TiO2–ZrO2: Performance Study of Microscopic Morphology and Phase Composition. Chemosphere 2022, 295, 133794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertinchamps, F.; Treinen, M.; Blangenois, N.; Mariage, E.; Gaigneaux, E. Positive Effect of NO on the Performances of VO/TiO-Based Catalysts in the Total Oxidation Abatement of Chlorobenzene. J. Catal. 2005, 230, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Deng, S.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Cao, Q.; Huang, J.; Yu, G. Catalytic Destruction of Pentachlorobenzene in Simulated Flue Gas by a V2O5–WO3/TiO2 Catalyst. Chemosphere 2012, 87, 1032–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.; Li, K.; Niu, H.; Peng, Y.; Chen, J.; Huang, Y.; Li, J. Simultaneous Removal of NOx and Chlorobenzene on V2O5/TiO2 Granular Catalyst: Kinetic Study and Performance Prediction. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2021, 15, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Peng, Y.; Zhu, X.; Wang, H.; Song, Z.; Si, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, J. Anti-Poisoning Mechanisms of Sb on Vanadia-Based Catalysts for NOx and Chlorobenzene Multi-Pollutant Control. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 10211–10220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Liu, Z.; Wang, D.; Peng, Y.; Li, J. The Effect of Additives and Intermediates on Vanadia-Based Catalyst for Multi-Pollutant Control. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Shen, K.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, H.; Wu, P.; Wang, B.; Zhang, S. Synergistic Degradation Mechanism of Chlorobenzene and NO over the Multi-Active Center Catalyst: The Role of NO2, Brønsted Acidic Site, Oxygen Vacancy. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 286, 119865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hou, Y.; Li, B.; Yang, Y.; Ma, S.; Wang, B.; Qin, G.; Huang, Z. Inhibition Mechanism of Chlorobenzene on NH3-SCR Side Reactions over MnOx-CeO2 Confined Titania Nanotubes. Fuel 2023, 349, 128619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.; Shi, W.; Li, K.; Chen, J.; Peng, Y.; Li, J. Synergistic Promotion Effect between NOx and Chlorobenzene Removal on MnOx–CeO2 Catalyst. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 30426–30432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Shen, Y.; He, J.; Qu, W.; Deng, J.; Han, L.; Chen, A.; Zhang, D. Synergistic Catalytic Elimination of NOx and Chlorinated Organics: Cooperation of Acid Sites. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 3719–3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Lu, P.; Chen, X.; Fang, P.; Peng, Y.; Li, J.; Huang, H. The Deactivation Mechanism of Toluene on MnOx-CeO2 SCR Catalyst. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 277, 119257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Guo, Z.; Li, J.; Xiao, G.; Ye, D.; Hu, Y. V-Cu Bimetallic Oxide Supported Catalysts for Synergistic Removal of Toluene and NOx from Coal-Fired Flue Gas: The Crucial Role of Support. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 458, 141443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Lin, B.; Huang, Y.; Tang, J.; Chen, P.; Ye, D.; Hu, Y. Design of Bimetallic Catalyst with Dual-Functional Cu-Ce Sites for Synergistic NOx and Toluene Abatement. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2024, 342, 123430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, L.; Liao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Ma, X. Copper/Nickel/Cobalt Modified Molybdenum-Tungsten-Titanium Dioxide-Based Catalysts for Multi-Pollution Control of Nitrogen Oxide, Benzene, and Toluene: Enhanced Redox Capacity and Mechanism Study. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 659, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, C.; Han, R.; Su, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Peng, M.; Liu, Q. Effect of the Acid Site in the Catalytic Degradation of Volatile Organic Compounds: A Review. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 454, 140125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallastegi-Villa, M.; Aranzabal, A.; González-Marcos, M.P.; Markaide-Aiastui, B.A.; González-Marcos, J.A.; González-Velasco, J.R. Effect of Vanadia Loading on Acidic and Redox Properties of VOx/TiO2 for the Simultaneous Abatement of PCDD/Fs and NOx. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2020, 81, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hou, Y.; Li, B.; Yang, Y.; Ma, S.; Wang, B.; Huang, Z. Synergistic Promotion Effect of Acidity and Redox Capacity in the Simultaneous Removal of CB and NOx in NH3-SCR Unit. Fuel 2023, 342, 127838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Ye, C.; Xie, H.; Wang, L.; Zheng, B.; He, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhou, J.; Ge, C. High-Temperature Vanadium-Free Catalyst for Selective Catalytic Reduction of NO with NH3 and Theoretical Study of La2O3 over CeO2/TiO2. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2021, 11, 6112–6125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Huang, X.; Feng, Y.; Zhou, J.; Shi, H.; Jin, J. Interaction Mechanism Study on Simultaneous Removal of 1,2-Dichlorobenzene and NO over MnOx–CeO2/TiO2 Catalysts at Low Temperatures. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 4820–4830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Z.; Song, H.; Zhou, C.; Xin, Q.; Zhou, F.; Fan, W.; Liu, S.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, C.; Yang, Y.; et al. A Promising Catalyst for Catalytic Oxidation of Chlorobenzene and Slipped Ammonia in SCR Exhaust Gas: Investigating the Simultaneous Removal Mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 473, 145106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, P.; Shen, K.; Zhang, S.; Ding, S. Improved Activity and Significant SO2 Tolerance of Sb-Pd-V Oxides on N-Doped TiO2 for Cb/Nox Synergistic Degradation. SSRN J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Gao, S.; Yu, J. Metal Sites in Zeolites: Synthesis, Characterization, and Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 6039–6106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, P.; Cao, R.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, J. Promotion Effect of SO42−/Fe2O3 Modified MnOx Catalysts for Simultaneous Control of NO and CVOCs. Surf. Interfaces 2022, 33, 102253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. Oxygen Vacancy Engineering on Copper-Manganese Spinel Surface for Enhancing Toluene Catalytic Combustion: A Comparative Study of Acid Treatment and Alkali Treatment. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2024, 340, 123142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Xiong, J.; Zhang, P.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Z.; Xu, L.; Guo, H.; Chen, K.; Wei, Y. Recent Progress on Density Functional Theory Calculations for Catalytic Control of Air Pollution. ACS EST Eng. 2024, 4, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Brewe, D.; Lee, J.-Y. Effects of Impregnation Sequence for Mo-Modified V-Based SCR Catalyst on Simultaneous Hg(0) Oxidation and NO Reduction. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 270, 118854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Wang, Z.; Mi, J.; Liu, H.; Wang, B.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Li, J. To Be Support or Promoter: The Mode of Introducing Ceria into Commercial V2O5/TiO2 Catalyst for Enhanced Hg0 Oxidation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 454, 131489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Z.; Song, W.; Wei, Y. A New 3DOM Ce-Fe-Ti Material for Simultaneously Catalytic Removal of PM and NOx from Diesel Engines. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 342, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Janus Electronic State of Supported Iridium Nanoclusters for Sustainable Alkaline Water Electrolysis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Lou, L.-L.; Liu, S.; Zhou, W. Asymmetric Oxygen Vacancies: The Intrinsic Redox Active Sites in Metal Oxide Catalysts. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 1901970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Lai, J.; Lin, X.; Zhang, H.; Du, H.; Long, J.; Yan, J.; Li, X. Implication of Operation Time on Low-Temperature Catalytic Oxidation of Chloroaromatic Organics over VOx/TiO2 Catalysts: Deactivation Mechanism Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 372, 133477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Liu, H.; Chen, W.; Chen, D.; Yu, S.; Liu, A.; Dong, L.; Feng, S. Insights into the Sm/Zr Co-Doping Effects on N2 Selectivity and SO2 Resistance of a MnOx-TiO2 Catalyst for the NH3-SCR Reaction. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 347, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marberger, A.; Ferri, D.; Elsener, M.; Kröcher, O. The Significance of Lewis Acid Sites for the Selective Catalytic Reduction of Nitric Oxide on Vanadium-Based Catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 11989–11994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, X.; Sun, P.; Long, Y.; Meng, Q.; Wu, Z. Catalytic Oxidation of Chlorobenzene over Mnx Ce1–xO2 /HZSM-5 Catalysts: A Study with Practical Implications. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 8057–8066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wang, C.; Chang, H.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, T.; Li, J. New Insight into SO2 Poisoning and Regeneration of CeO2–WO3/TiO2 and V2O5–WO3/TiO2 Catalysts for Low-Temperature NH3–SCR. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 7064–7071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Yu, Y.; Bi, F.; Sun, P.; Weng, X.; Wu, Z. Synergistic Elimination of NOx and Chloroaromatics on a Commercial V2O5–WO3/TiO2 Catalyst: Byproduct Analyses and the SO2 Effect. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 12657–12667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, T.; Ding, S. Adsorption and Desorption of SO2, NO and Chlorobenzene on Activated Carbon. J. Environ. Sci. 2016, 43, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Hou, Y.; Ding, X.; Tian, J.; Li, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, J.; Huang, Z. Unravelling the Impacts of Sulfur Dioxide on Dioxin Catalytic Decomposition on V2O5/AC Catalysts. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 901, 166462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, P.; Fang, P.; Ren, T.; Liu, Y.; Cen, C.; Wang, H.; Wu, Z. Tuning the Property of Mn-Ce Composite Oxides by Titanate Nanotubes to Improve the Activity, Selectivity and SO2/H2O Tolerance in Middle Temperature NH3-SCR Reaction. Fuel Process. Technol. 2017, 167, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Feng, S.; Shen, B.; Li, Z.; Gao, P.; Zhang, C.; Shi, G. Simultaneous Removal NO and Toluene over the Sb Enhanced MnOx Catalysts. Fuel 2024, 360, 130533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero-Rey, J.R.; López-Vilariño, J.M.; Moreda-Piñeiro, J.; Alonso-Rodríguez, E.; Muniategui-Lorenzo, S.; López-Mahía, P.; Prada-Rodríguez, D. As, Hg, and Se Flue Gas Sampling in a Coal-Fired Power Plant and Their Fate during Coal Combustion. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 5262–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eighmy, T.T.; Eusden, J.D.; Krzanowski, J.E.; Domingo, D.S.; Staempfli, D.; Martin, J.R.; Erickson, P.M. Comprehensive Approach toward Understanding Element Speciation and Leaching Behavior in Municipal Solid Waste Incineration Electrostatic Precipitator Ash. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1995, 29, 629–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Du, X.; Fu, Y.; Mao, J.; Luo, Z.; Ni, M.; Cen, K. Theoretical and Experimental Study on the Deactivation of V2O5 Based Catalyst by Lead for Selective Catalytic Reduction of Nitric Oxides. Catal. Today 2011, 175, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, X.; Xue, Y.; Chen, J.; Meng, Q.; Wu, Z. Elimination of Chloroaromatic Congeners on a Commercial V2O5-WO3/TiO2 Catalyst: The Effect of Heavy Metal Pb. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 387, 121705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Long, Y.; Long, Y.; Cao, S.; Weng, X.; Wu, Z. Deactivation Effects of Pb(II) and Sulfur Dioxide on a γ-MnO2 Catalyst for Combustion of Chlorobenzene. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 559, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Jiang, M.; Chen, J.; Yan, D.; Jia, H. Unveiling the Lead Resistance Mechanism and Interface Regulation Strategy of Ru-Based Catalyst during Chlorinated VOCs Oxidation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 315, 121592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Su, Y.; Chen, M.; Lu, S.; Luo, X.; Zhu, Z.; Wu, Z.; Weng, X. Polymerization State of Vanadyl Species Affects the Catalytic Activity and Arsenic Resistance of the V2O5–WO3/TiO2 Catalyst in Multipollutant Control of NOx and Chlorinated Aromatics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 7590–7598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Li, J.; Si, W.; Luo, J.; Dai, Q.; Luo, X.; Liu, X.; Hao, J. Insight into Deactivation of Commercial SCR Catalyst by Arsenic: An Experiment and DFT Study. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 13895–13900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, L.; Li, J.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, Y. Heavy Metal Poisoned and Regeneration of Selective Catalytic Reduction Catalysts. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 366, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, Y.; Su, Y.; Xue, Y.; Wu, Z.; Weng, X. V2O5–WO3/TiO2 Catalyst for Efficient Synergistic Control of NOx and Chlorinated Organics: Insights into the Arsenic Effect. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 9317–9325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, T.; Liu, K.; Gao, R.; Chen, H.; Yu, X.; Hou, Z.; Jing, L.; Deng, J.; Liu, Y.; Dai, H. Enhanced Performance of Supported Ternary Metal Catalysts for the Oxidation of Toluene in the Presence of Trichloroethylene. Catalysts 2022, 12, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Li, J.; Yang, P.; Cheng, Z.; Li, J.; Zuo, S. Ce-Modified Mesoporous γ-Al2O3 Supported Pd-Pt Nanoparticle Catalysts and Their Structure-Function Relationship in Complete Benzene Oxidation. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 356, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Kang, S.; Ma, J.; Zhang, C.; He, H. Silver Incorporated into Cryptomelane-Type Manganese Oxide Boosts the Catalytic Oxidation of Benzene. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018, 239, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Chen, J.; Peng, Y.; Si, W.; Li, X.; Li, B.; Li, J. Dechlorination of Chlorobenzene on Vanadium-Based Catalysts for Low-Temperature SCR. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 2032–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Chen, A.; Lan, T.; Chen, X.; Wang, M.; Hu, X.; Wang, P.; Cheng, D.; Zhang, D. Synergistic Catalytic Removal of NOx and Chlorinated Organics through the Cooperation of Different Active Sites. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 468, 133722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, D.; Shi, Q.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, P.; Lyu, H.; Huang, A.; Shen, B. Modulation of Acidic and Redox Properties of Mn-Based Catalysts by Co Doping: Application to the Synergistic Removal of NOx and Chlorinated Organics. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 339, 126695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Martín, J.A.; Gallastegi-Villa, M.; González-Marcos, M.P.; Aranzabal, A.; González-Velasco, J.R. Bimodal Effect of Water on V2O5/TiO2 Catalysts with Different Vanadium Species in the Simultaneous NO Reduction and 1,2-Dichlorobenzene Oxidation. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 417, 129013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Ye, L.; Yan, X.; Fang, P.; Chen, X.; Chen, D.; Cen, C. Impact of Toluene Poisoning on MnCe/HZSM-5 SCR Catalyst. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 414, 128838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-Y.; Ren, Y.; He, J.; Xiao, H.; Li, J.-R. Recent Advances of the Effect of H2O on VOC Oxidation over Catalysts: Influencing Factors, Inhibition/Promotion Mechanisms, and Water Resistance Strategies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 1034–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, L.; Liao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Ma, X. Enhanced Dual-Catalytic Elimination of NO and VOCs by Bimetallic Oxide (CuCe/MnCe/CoCe) Modified WTiO2 Catalysts: Boosting Acid Sites and Rich Oxygen Vacancy. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 335, 126160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Ding, S.; Hou, X.; Shen, K.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y. Unlocking Low-Temperature and Anti-SO2 Poisoning Performance of Bimetallic Pdv/TiO2 Catalyst for Chlorobenzene/Nox Catalytic Removal by Antimony Modification Design. SSRN J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, C.; Chen, L.; Tang, J.; Liao, Y.; Ma, X. Multiple Pollutants Control of NO, Benzene and Toluene from Coal-Fired Plant by Mo/Ni Impregnated TiO2-Based NH3-SCR Catalyst: A DFT Supported Experimental Study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 599, 153986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; Guo, Z.; Li, J.; Du, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xiong, T.; Lin, B.; Fu, M.; Ye, D.; Hu, Y. Insights into the Effect of Flue Gas on Synergistic Elimination of Toluene and NO over V2O5-MoO3(WO3)/TiO2 Catalysts. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 435, 134914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Lin, F.; Xiang, L.; Yu, H.; Wang, Z.; Yan, B.; Chen, G. Synergistic Effect for Simultaneously Catalytic Ozonation of Chlorobenzene and NO over MnCoO Catalysts: Byproducts Formation under Practical Conditions. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 427, 130929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xiao, J.; Gao, Y.; Gui, R.; Wang, Q. Design of Bifunctional Cu-SSZ-13@Mn2Cu1Al1Ox Core–Shell Catalyst with Superior Activity for the Simultaneous Removal of VOCs and NOx. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 20326–20338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liao, Y.; Xin, S.; Song, X.; Liu, G.; Ma, X. Simultaneous Removal of NO and Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) by Ce/Mo Doping-Modified Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) Catalysts in Denitrification Zone of Coal-Fired Flue Gas. Fuel 2020, 262, 116485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; Liu, A.; Xie, S.; Yan, Y.; Shaw, T.E.; Pu, Y.; Guo, K.; Li, L.; Yu, S.; Gao, F.; et al. Ce–Si Mixed Oxide: A High Sulfur Resistant Catalyst in the NH3–SCR Reaction through the Mechanism-Enhanced Process. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 4017–4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, W.; Song, Y.; Liu, B.; Wu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, H. Commercial SCR Catalyst Modified with Cu Metal to Simultaneously Efficiently Remove NO and Toluene in the Fuel Gas. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 96543–96553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liao, Y.; Chen, L.; Chen, Z.; Ma, X. Performance of Transition Metal (Cu, Fe and Co) Modified SCR Catalysts for Simultaneous Removal of NO and Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) from Coal-Fired Power Plant Flue Gas. Fuel 2021, 289, 119849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Cai, Q.; Zhao, H.; Guo, R.; Zhou, J.; Hu, Z.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, L.; Lu, Q. Promotional Effects of FeOx on the Commercial SCR Catalyst for the Synergistic Removal of NO and Dioxins from Municipal Solid Waste Incineration Flue Gas. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 8512–8522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Peng, Y.; Zhao, X.; Liu, H.; Gao, C.; Si, W.; Li, J. Roles of Ru on the V2O5–WO3/TiO2 Catalyst for the Simultaneous Purification of NOx and Chlorobenzene: A Dechlorination Promoter and a Redox Inductor. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 11505–11517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wang, L.; Wu, P.; Zhang, S.; Shen, K.; Zhang, Y. Insight into the Combined Catalytic Removal Properties of Pd Modification V/TiO2 Catalysts for the Nitrogen Oxides and Benzene by: An Experiment and DFT Study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 527, 146787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Li, K.; Peng, Y.; Duan, R.; Hu, F.; Jing, Q.; Chen, J.; Li, J. Fe-Doped α-MnO2 Nanorods for the Catalytic Removal of NOx and Chlorobenzene: The Relationship between Lattice Distortion and Catalytic Redox Properties. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 25880–25888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, D.; Shi, Q.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, P.; Lyu, H.; Yang, M.; Bian, Y.; Shen, B. Synergistic Removal of NOx and CB by Co-MnOx Catalysts in a Low-Temperature Window. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 476, 146369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.-F.; Yan, Z.-L.; Jin, L.-Y. Structure and Redox Properties of CexPr1−xO2−δ Mixed Oxides and Their Catalytic Activities for CO, CH3OH and CH4 Combustion. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2006, 260, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Zhu, N.; Hou, L.; Wang, S.; Li, S. Pr-Modified Vanadia-Based Catalyst for Simultaneous Elimination of NO and Chlorobenzene. Mol. Catal. 2023, 548, 113430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Wang, X.; Long, Y.; Pattisson, S.; Lu, Y.; Morgan, D.J.; Taylor, S.H.; Carter, J.H.; Hutchings, G.J.; Wu, Z.; et al. Efficient Elimination of Chlorinated Organics on a Phosphoric Acid Modified CeO2 Catalyst: A Hydrolytic Destruction Route. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 12697–12705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.; Ye, P.; Tian, X.; Mi, J.; Xing, J.; Xue, Q.; Wu, Q.; Chen, J.; Li, J. Simultaneous Removal of NO and VOCs by Si Doping CeO2 Based Catalysts: An Acidity and Redox Properties Balance Strategy. Fuel 2024, 366, 131396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, H.; Feng, X.; Ma, L.; Cao, X.; Wang, B. Ni-Ce-Ti as a Superior Catalyst for the Selective Catalytic Reduction of NOx with NH3. Mol. Catal. 2018, 445, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Dong, F.; Wang, J.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, J. Constructing a Core–Shell Pt@MnOx /SiO2 Catalyst for Benzene Catalytic Combustion with Excellent SO2 Resistance: New Insights into Active Sites. Environ. Sci. Nano 2024, 11, 1926–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Xu, S.; Liu, Q.; Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Yu, Y.; Chen, C.; Chen, Z.; Li, L.; et al. Rationally Engineering a CuO/Pd@SiO2 Core–Shell Catalyst with Isolated Bifunctional Pd and Cu Active Sites for n-Butylamine Controllable Decomposition. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 16189–16199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, J.; Huang, Y.; Wang, X. Core-Shell Structure CuO-TiO2@CeO2 Catalyst with Multiple Active Sites for Simultaneous Removal of NO, Hg0 and Toluene. Fuel 2023, 349, 128648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xing, Y.; Jia, H.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, H.; Qian, D.; Su, W. TiO2-Coated CeCoOx-PVP Catalysts Derived from Prussian Blue Analogue for Synergistic Elimination of NOx and o-DCB: The Coupling of Redox and Acidity. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 476, 146390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Li, X.; Deng, L.; Tian, M.; Cen, W.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhu, T. Confining the Reactions on Active Facet Enhances the Simultaneous Removal of NO and Toluene by Copper-Titanium Catalysts. Fuel 2024, 365, 131157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lin, X.; Xue, Q.; Ding, X.; Tian, Z.; Wang, Y.; Jin, S.; Liu, S.; Hrynshpan, D.; Savitskaya, T.; et al. MnOx@CeSnOx with Core-Shell Structure and Electronic Interaction Boosting Sulfur Tolerance in Simultaneous Removal of NO and Chlorobenzene. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2026, 381, 125868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Zhao, L.; Jiang, S.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, J. Effect of Transition-Metal Oxide M (M = Co, Fe, and Mn) Modification on the Performance and Structure of Porous CuZrCe Catalysts for Simultaneous Removal of NO and Toluene at Low–Medium Temperatures. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 4439–4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Jiang, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Tang, J.; Li, C. Mechanism Investigation of Three-Dimensional Porous A-Site Substituted La1-xCoxFeO3 Catalysts for Simultaneous Oxidation of NO and Toluene with H2O. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 578, 151977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okhlopkova, L.B.; Lisitsyn, A.S.; Likholobov, V.A.; Gurrath, M.; Boehm, H.P. Properties of Pt/C and Pd/C Catalysts Prepared by Reduction with Hydrogen of Adsorbed Metal Chlorides Influence of Pore Structure of the Support. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2000, 204, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Jia, X.; Liu, R.; Fang, H.; Wang, J.; Li, D.; Xiong, J.; Dan, J.; Dai, Z.; Wang, L. A Novel Supported Mn-Ce Catalyst with Meso-Microporous Structure for Low Temperature Synergistic Removal of Nitrogen Oxides and Toluene: Structure–Activity Relationship and Synergistic Mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 477, 147149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwath, J.P.; Lehman-Chong, C.; Vojvodic, A.; Stach, E.A. Surface Rearrangement and Sublimation Kinetics of Supported Gold Nanoparticle Catalysts. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 8098–8107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, B.; Pan, H.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Ye, Z. Catalytic Reduction of NO and Oxidation of Dichloroethane over α-MnO2 Catalysts: Properties-Reactivity Relationship. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16, 104587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Guo, Z.; Tang, J.; Chen, P.; Ye, D.; Hu, Y. Modulating the Microstructure and Surface Acidity of MnO2 by Doping-Induced Phase Transition for Simultaneous Removal of Toluene and NOx at Low Temperature. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 10398–10408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Catalyst | Reactant Composition | Space Velocity (mL·g−1·h−1) | Conversion | Conversion (After) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CuCeTi | Toluene 50 ppm, NO 500 ppm, NH3 500 ppm, SO2 0–500 ppm, 10% O2, 5% H2O | 60,000 | / | Toluene: >90% (300 °C) NO: >90% (300 °C) | [55] |

| Benzene 100 ppm, Toluene 100 ppm, NO 500 ppm, NH3 500 ppm, SO2 1000 ppm, 3.3% O2 | 45,000 | / | Benzene: >85% (260–420 °C) Toluene: >92% (260–420 °C) NO: >91% (260–420 °C) | [102] | |

| SbPdV/TiO2 | CB 600 ppm, NO 600 ppm, NH3 600 ppm, SO2 600 ppm, 10% O2 | 30,000 | CB: >90% (325 °C) NO: >90% (200 °C) | CB: >90% (350 °C) NO: >90% (225 °C) | [103] |

| Sb/VWT | CB 100 ppm, NO 500 ppm, NH3 500 ppm, SO2 50 ppm, 10% O2 | 60,000 | CB: 100% (325 °C) NO: ~95% (325 °C) | CB: 100% (325 °C) NO: ~90% (325 °C) | [47] |

| Cu0.1-VWT | Benzene 100 ppm, Toluene 100 ppm, NO 500 ppm, NH3 500 ppm, SO2 1000 ppm, 3.3% O2 | 45,000 | / | Benzene: 98.65% (260–420 °C) Toluene: 99.89% (260–420 °C) NO: 86.5% (260–420 °C) | [104] |

| V-Mo/TiO2 | Toluene 50 ppm, NO 50–500 ppm, NH3 50–1000, 600 ppmSO2 1000 ppm | 120,000 | Toluene: ~97% (350 °C) NO: / | Toluene: ~85% (350 °C) NO: / | [105] |

| MnCoOx | CB 50 ppm, NO 50 ppm, SO2 50 ppm | 12,000 | CB: ~97% (120 °C) NO: / | CB: ~90% (120 °C) NO: / | [106] |

| Cu-SSZ-13@Mn2Cu1Al1Ox | Toluene 800 ppm, NOx 100 ppm, NH3 100 ppm, SO2 50 ppm, 20% O2, 5% H2O | 60,000 | Toluene: ~99% (300 °C) NO: ~99% (300 °C) | Toluene: ~89% (300 °C) NO: ~95% (300 °C) | [107] |

| Sb-Mn | Toluene 100 ppm, NO 600 ppm, NH3 600 ppm, SO2 200 ppm, 5% O2, 5% H2O | 15,000 | Toluene: 100% (250) NO: 100% (200 °C) | Toluene:80% (250) NO: 80% (200 °C) | [82] |

| Catalyst | Doping Element | Reactant Composition | Space Velocity (mL·g−1·h−1) | Conversion | Conversion (After) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VWT | Cu | Toluene 50 ppm, NH3 500 ppm, NO 500 ppm, SO2 100 ppm, O2 5.5%, H2O 8%, | 60,000 | Toluene: ~50% NO: ~80% | Toluene: ~95% NO: 100% | [110] |

| Fe | Benzene 100 ppm, Toluene 100 ppm, NH3 500 ppm, NO 500 ppm, SO2 1000 ppm, O2 3.33% | 45,000 | / | Benzene: ~99% Toluene: ~99% NO: ~76% | [111] | |

| Co | Benzene 100 ppm, Toluene 100 ppm, NH3 500 ppm, NO 500 ppm, SO2 1000 ppm, O2 3.33% | Benzene: ~94% Toluene: ~99% NO: ~74% | [111] | |||

| Ce | Benzene 500 ppm, Toluene 500 ppm, NO 0.5% vol, NH3 0.5% mol, SO2 0.5% vol, O2 20% vol | 45,000 | Benzene: ~98% Toluene: ~85% NO: ~20% | Benzene: ~99% Toluene: ~99% NO: ~25% | [108] | |

| Mo | Benzene 500 ppm, Toluene 500 ppm, NO 0.5% vol, NH3 0.5% mol, SO2 0.5% vol, O2 20% vol | Benzene: ~98% Toluene: ~99% NO: ~15% | [108] | |||

| Ni | NH3 500 ppm, NO 500 ppm, Benzene 100 ppm, Toluene 100 ppm, SO2 1000 ppm, 3.33% O2 | 45,000 | Benzene: ~90% Toluene: ~99% NO: ~50% | Benzene: ~95% Toluene: ~99% NO: ~65% | [104] | |

| [104] | ||||||

| VMT | Ce | CB 50 ppm, NH3 300 ppm, NO 300 ppm, O2 10 vol%, H2O 5 vol % | 21,000 | CB: ~45% NO: ~90% | CB: ~66% NO: ~75% | [112] |

| Fe | CB 50 ppm, NH3 300 ppm, NO 300 ppm, O2 10 vol%, H2O 5 vol % | CB: ~80% NO: ~82% | [112] | |||

| Mn | CB 50 ppm, NH3 300 ppm, NO 300 ppm, O2 10 vol%, H2O 5 vol % | CB: ~65% NO: ~81% | [112] | |||

| Cr | CB 50 ppm, NH3 300 ppm, NO 300 ppm, O2 10 vol%, H2O 5 vol % | CB: ~70% NO: ~89% | [112] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tian, Z.; Ding, X.; Pan, H.; Xue, Q.; Chen, J.; He, C. A Review of Simultaneous Catalytic Removal of NOx and VOCs: From Mechanism to Modification Strategy. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1114. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121114

Tian Z, Ding X, Pan H, Xue Q, Chen J, He C. A Review of Simultaneous Catalytic Removal of NOx and VOCs: From Mechanism to Modification Strategy. Catalysts. 2025; 15(12):1114. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121114

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, Zhongliang, Xingjie Ding, Hua Pan, Qingquan Xue, Jun Chen, and Chi He. 2025. "A Review of Simultaneous Catalytic Removal of NOx and VOCs: From Mechanism to Modification Strategy" Catalysts 15, no. 12: 1114. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121114

APA StyleTian, Z., Ding, X., Pan, H., Xue, Q., Chen, J., & He, C. (2025). A Review of Simultaneous Catalytic Removal of NOx and VOCs: From Mechanism to Modification Strategy. Catalysts, 15(12), 1114. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121114