Abstract

Crystalline TiO2 films were synthesized on hydrophilic glass substrates by Peroxo sol–gel and sedimentation (S1–S4) and compared with conventional sol–gel protocols (S5–S10). The films were deposited on soda-lime glass and characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), and UV–Vis absorption. Photocatalytic activity was evaluated through the inactivation of multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli and Salmonella Typhimurium, and the removal of chemical oxygen demand (COD) from greywater under UV irradiation. The obtained films exhibited anatase crystallinity, crystallite sizes of ~60 nm, and grain sizes between 1.5 and 3.0 µm. S1 films showed a bandgap of 3.26 eV (380 nm). Under UV exposure, S1 reduced E. coli and S. Typhimurium by 4.78 and 3.00 Log10 units, respectively, at pH 5.0 after 30 min, while COD decreased to 380 mg L−1 compared to 433 mg L−1 with UV photolysis alone. Increasing TiO2 loading and extending irradiation to 120 min further enhanced bacterial inactivation (93 and 78% for E. coli and S. Typhimurium), COD (33%), NH4+ (90%), and H2S (89%) oxidation, outperforming UV-light controls. These results indicate that S1 films exhibited superior crystallinity, photocatalytic performance, and bacterial inactivation compared to other protocols, although complete mineralization was not achieved.

1. Introduction

The world population growth in urban and rural areas has led to an increasing need for more and more food to meet the needs of humans and animals safely and sufficiently []. It has increased surface water use to support agro-industrial and domestic activities []. This surface water, when used, is converted into non-domestic (nDWW) [] or domestic wastewater (DWW: blackwater, brownwater, and greywater) []. Water treatment must take place before being discharged into sewage systems, water bodies, or reused in agricultural or industrial activities to reduce their environmental impact and also to reduce the risk of transmission of waterborne diseases in humans and animals [].

Inadequate wastewater treatment increases the risk of the transmission of diseases caused by microorganisms [,] affecting animals and humans, consequently generating high costs in public health systems and animal production [,,]. For example, bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Salmonella spp. are frequently at the inlet and outlet of DWW and agro-industrial treatment plants [,]. Furthermore, water contaminated with Salmonella spp. and E. coli is of public health concern, as it is water for drinking, agriculture, and food production, among other purposes. The increase in world population and the impact of climate change have determined that water quality is not adequate for these activities []; only one out of three people in the world have access to quality water [], (it has been estimated), in this sense, it is necessary to treat wastewater for reuse, where emerging technologies are essential. It is necessary to generate a renewable and alternative source of treated water suitable for non-potable reuse, thereby partially contributing to the reduction in excessive surface water consumption [].

The most common treatment systems for domestic wastewater (blackwater, brownwater, and greywater) are physical, chemical, and biological processes, most are efficient in the remotion of carbonaceous organic matter and nutrients; in contrast, the reduction or inactivation of bacteria that can affect human and animal health is less efficient []. The problem increases with the presence of micropollutants (antibiotics, analgesics, cytostatics, hormones, disinfectants, and detergents, among others) [] and bacteria that have acquired resistance to multiple antibiotics (multidrug-resistant bacteria: MDR bacteria) [].

An alternative to eliminate these bacteria is to use advanced oxidation processes such as photocatalysis or photo Fenton, either with ultraviolet, visible, or solar radiation []. The photocatalysis process involves a semiconductor material such as TiO2, that when exposed to electromagnetic radiation that exceeds the bandgap value (ultraviolet light), generates a photoelectric excitation phenomenon, in which the energy of the photons (hν) become adsorbed by the electrons present in the valence band (BV) of TiO2 []; thereby generating energy transitions between the valence band and conduction band to produce electron-hole pairs (e−/h+), which trigger a series of oxidation-reduction reactions [,]. For example, when TiO2 is in an aqueous solution such as domestic wastewater, the photogenerated holes can directly oxidize pollutants or react with water adsorbed on the TiO2 surface to form hydroxyl radicals (HO•); in turn, these radicals can oxidize organic compounds and inactivate microorganisms [,]. On the other hand, conduction band electrons participate in the reductive stage of photocatalysis by being transferred to O2 (primary electron acceptor) to produce intermediates such as peroxide anion, peroxide dianion, superoxide, among others, which can also cause cell damage in bacteria, fungi and parasites [,,].

Titanium dioxide (TiO2) is a semiconductor most commonly used for domestic and non-domestic wastewater treatment and microorganism inactivation due to its physicochemical properties such as its strong oxidizing capacity, high chemical stability, low toxicity, and low cost []. There are reports of different physical and chemical techniques for producing useful TiO2 in photocatalysis; one of them is the sol–gel technique, a chemical technique where hydrolysis and condensation reactions of precursors occur []. The sol formation depends on synthesis reactions such as the hydrolysis of Titanium alkoxide and the condensation of Titanium hydroxides, also depending on the type and proportion of Titanium alkoxide, the addition of oxidizing agents, acids, and water [].

Titanium alkoxide hydrolysis occurs by substitution of the alkoxy group (-OR) with a hydroxyl group (-OH) under acidic, neutral or alkaline conditions []. These reactions occur after Titanium alkoxide hydrolyzation by water and ethanol, maintaining the reactivity to produce Titanium hydroxides together with acetic acid that keeps the Titanium hydroxides soluble [,]. However, complementary to this conventional mixture of reagents in the sol–gel process is the Peroxo sol–gel method, where H2O2 addition to the hydrolysis reaction serves as an oxidizing or peptizing agent, forming Ti-Peroxo species with a characteristic yellow coloring. As the hydrolysis reaction progresses, gel formation initiates with the formation of metal alkoxide bonds, and condensation and agglomerate formation continue in the sol []. Thus, favoring the formation of discrete colloidal particles in a liquid phase known as amorphous Titanium sol; as the hydrolysis/condensation reactions continue, the viscosity of the solution changes until it gels at a temperature of 20 °C [,]. The xerogels or aerogels produced can be dried at different temperatures to obtain materials with various physical and chemical properties [].

To obtain TiO2 films, the sol–gel must be deposited on the substrate and subsequently subjected to heat treatment to induce crystallinity [,,,]. Conventional deposition techniques such as spin coating [,] and dip coating [,] are effective, but they require specialized equipment that is not always available in many laboratories, and their scalability depends largely on the type of equipment used. In contrast, the sedimentation method, which only requires the modification of the solution’s pH, offers a simple and low-cost alternative. This approach is particularly advantageous for small laboratories or facilities located in remote areas lacking infrastructure for advanced deposition techniques such as dip coating, spin coating, spray pyrolysis, or magnetron sputtering. In addition, it can reduce the production costs of TiO2 films and facilitate future scaling of the technology in contexts such as small communities, where sanitation systems are often inadequate and inefficient in inactivating both non-resistant and antibiotic-resistant bacteria [,,].

Alternatively, TiO2 films can be produced by depositing the sol onto hydrophilic glass substrates through sedimentation []. In this study, the Peroxo sol–gel method combined with sedimentation was chosen as a practical alternative to conventional deposition techniques, aiming to address limitations related to cost and scalability. Unlike dip or spin coating, which require precise control equipment and frequently cause precursor losses during multiple coating steps, the sedimentation process allows direct film formation on different substrates, as demonstrated by Cañon et al. [,] on guadua sheet substrates. This method favors the production of thicker films, minimizes precursor waste, and eliminates the need for sophisticated coating systems [,]. In sedimentation, larger and heavier particles settle first, which defines the particle size distribution of the film []. Unlike dip or spin coating, sedimentation also avoids drainage-induced thinning and shear stresses during deposition [,]. Furthermore, it can be combined with low-temperature evaporation, improving adhesion and facilitating water and solvent removal [,,]. Finally, heat treatment converts amorphous titania into crystalline TiO2 [,,].

In a similar methodology previously reported by Villanueva et al. [], they prepared TiO2 films from a mixture of Titanium alkoxide and TiO2 powder, using sedimentation at an acidic pH, evaporation, and annealing. The TiO2 films were crystalline and showed photocatalytic activity against Escherichia coli from the surface waters of the Bogotá River. On the other hand, Fernández et al. [] deposited commercial TiO2 using a microdrip technique on the glass substrate, sedimentation, and evaporation. These films were modified with a natural dye obtained from Picramnia sellowii and had photocatalytic activity with visible light. Inactivation of 100% of total heterotrophic bacteria, removal of total organic carbon (>60%), and decolorization of more than 40% of a mixture of azo and triphenylmethane dyes were achieved []. Recently, Rincón and collaborators evaluated TiO2 films grown by the sol–gel method at both laboratory and pilot plant scales, demonstrating photocatalytic activity when irradiated with ultraviolet light (253 nm). At the laboratory scale, they achieved more than 70% inactivation of E. coli after 120 min of treatment. At the pilot plant scale, they obtained 93% E. coli inactivation and removals above 90% for COD and nitrites in greywater originating from kitchens [].

This study aimed to obtain crystalline TiO2 films deposited on hydrophilic glass substrates by combining two techniques, Peroxo sol–gel and sedimentation, to evaluate ten synthesis protocols, four of which prepared by Peroxo–Titanium sol–gel and the other six prepared by the conventional sol–gel method as an alternative to traditional deposition techniques for films with semiconducting materials, which also exhibit photocatalytic activity at high concentrations of multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli and Salmonella Typhimurium and remove organic matter expressed as COD in greywater.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Substrate Cleaning and Hydrophilicity

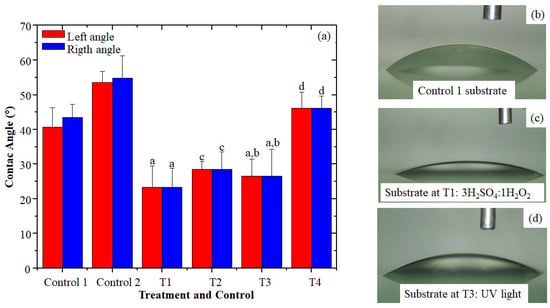

The Contact angles for C1 (unwashed glass) were (41 ± 6)° for the left angle and (44 ± 4)° for the right angle. For C2 (washed glass only), the values for the left angle were (54 ± 3)° and those for the right angle were (55 ± 6)°, indicating that the surfaces of the two controls were naturally hydrophilic, as the values obtained were less than 90 (Figure 1a, Table S1) []. According to the statistical analysis, significant differences were observed (p < 0.05) between treatments concerning the control 1 (unwashed substrate) in the right angle (44 ± 4)° and the left angle (41 ± 6)°, which indicates that when using the combination of T1 (3H2SO4:1H2O2 and cleaning of the substrate with detergent, MilliQ water, ethanol, and acetone), lower contact angles resulted, both on the right (24 ± 6)° and left (24 ± 5)°, which also represented a decrease of (46 ± 3)% of the right angle and (42 ± 3)% of the left one, concerning the first control (washed glass only); and a decrease of (55 ± 6)% for the right angle and (54 ± 5)% of the left angle compared to the second control. Additionally, with T3, which employed physical processing with 253 nm UV light radiation and cleaning of the substrate with detergent, MilliQ water, ethanol, and acetone, a decrease in the contact angle was also obtained with values of (26 ± 5)° for the right angle and (26 ± 7)° for the left one, with a percentage decrease of (41 ± 3)% for the right angle and (36 ± 3)% for the left, concerning the first control and (49 ± 5)% for the right angle and (45 ± 7)% of the left angle decrease compared to the second control. Figure 1b shows a drop on the unmodified substrate surface and Figure 1c,d, show the substrate surface modified by the chemical and physical methods, respectively. In T3 and T4, Figure 1a, the UV light photons used to irradiate the glass surface had enough energy (~4.9 eV) to break the surface intermolecular bonds of the glass, releasing oxygen atoms, resulting in oxygen vacancies on the glass surface, which, once in contact with water, form OH groups altering the surface forces at the solid–liquid interface, increasing the surface energy and decreasing the contact angle [,,]. The study by Syafiq et al. [] modified the glass substrate surface with TiO2 and Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) thin films and evaluated the effects of UV light irradiation on the glass surface by measuring the contact angle, showing changes in the hydrophilic properties of the modified surface upon contact with UV light []; this behavior was similar to that presented in the work of Wenting et al. [], in which UV radiation of the modified glass substrates broke surface bonds generating dipolar groups (-OH) that affected the surface tension making the surface superhydrophobic []. However, the surface effects of UV light are limited when the glass surface is not clean because glasses may contain a thin layer of organic contaminants that do not allow UV light photoexcitation of the surface [,], as was verified in treatment T4 (irradiation with UV253nm without previous cleaning) since the contact angle increased concerning control 1, which suggests that the glass substrate surface could have organic compounds and the surface changes produced due to UV irradiation are not permanent and tend to revert the hydrophilicity process; this phenomenon known as decreased in hydrophilicity caused mainly by the gradual coating of the silicon structure with free producing siloxanes, which results in the reorientation in the polar groups and reduces the surface energy [,]. This was indicated by Chen et al. [] in their study on the effect of UV/ozone radiation on hydrophilicity, where exposure of a surface to light for less than 30 min causes a rapid reduction in the subsequent contact angles called contact angle hysteresis [,,].

Figure 1.

Effect of chemical and physical treatments on the increased hydrophilicity of the substrate (a). The mean result of the three replicates for control 1, control 2, T1, T2, T3, and T4; letters above the bars identify the significant differences between treatments, with the letter a being the best treatment, followed by b, c and d (b). Image of a water drop over the control substrate (c). A water drop on the substrate at T1 (d). A water drop on the substrate at T3.

From these results, the chemical treatment 3H2SO4:1H2O2 and the previous cleaning of the substrate according to the protocol of Puentes et al. [] allowed the decrease in the static contact angle, generating hydroxylation on the substrate surface. Considering that soda-lime glass contains silicon oxides (~70%), sodium oxides (~14%), and calcium oxides (~6%), among other compounds [] the clustering of the atoms on its surface presents higher surface energy because the cations of these oxides remain exposed with Si-O-R active sites, allowing various interactions with the glass with the medium. As reported by Yu et al. [] and Jang et al. [], when the glass are expose to an acidic solution, the silanol and siloxane groups on its surface can form hydrogen bridge bonds by proton separation, where the sodium on the glass surface is exchanged with the hydrogen ions in the 3H2SO4:1H2O2 solution and removed together with the sulfate in the deionized water rinse [,,,,,]. So, breaking the Si-O-R or O-Si-O bonds allows the release of oxygen atoms, hydrating the glass surface by OH groups and improving its hydrophilicity []. According to Cras et al. [] in their study of chemical glass cleaning methods, the pre-washing of glass substrates together with exposure to sulfuric acid in combination with hydrogen peroxide allows the removal of organic contaminants, grease, and metallic ionic contaminants, modifying the hydrophilic properties of the glass once exposed for 1 h, which generated a contact angle of 12° []. Additionally, the study of Koh et al. [] employed a PDMS monomer for hydrophilic surface modification with a Piranha solution (3H2SO4:1H2O2), which they obtained as a result of the increase in silanol groups on the PDMS surface with the decrease in contact angle [,,].

2.2. Synthesis of TiO2 Films by Sol-Gel/Sedimentation

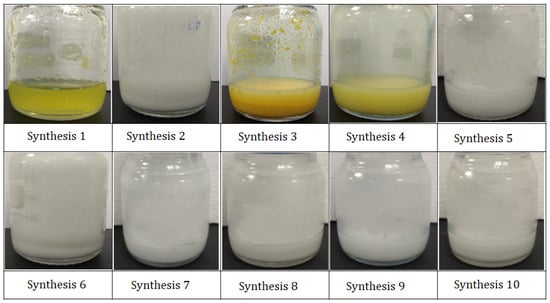

For the elaboration of TiO2 films, Tetraisopropyl Orthotitanate (TTIP) served as a metallic precursor of amorphous Titanium in three concentrations, and the effect of different concentrations of ethanol as the solvent, acetic acid as a catalyst to control the hydrolysis and condensation reactions, and hydrogen peroxide as an oxidant or peptizing agent, prepared in H2O concentration, was evaluated to generate four treatments (Peroxo sol–gel method). Concerning the TTIP/water ratio in the synthesis with the highest concentration of water (S1 and S4), the hydrolysis process was faster when compared to the treatments with only 0.49 M, 0.54 M, and 0.55 M of H2O (Figure 2), supporting the higher molar ratio of water and the faster hydrolysis reaction of the Titanium precursor [,]. When TTIP reacts with the aqueous solution, the metal ions of the precursor increase their coordination by the charge transfer from the 3 s orbital of the water to the d orbital of the metal causing the partial charge of the hydrogen to increase, acidifying the aqueous solution by the release of H+. This forms a precipitate that releases oxygen molecules or OH ligands, which upon interacting with acetic acid causes the absorption of protons in the solution by charging them positively, as reported by Pala et al. [] and Kignelman et al. [], studying different concentrations of components of sol–gel in an alcoholic medium and the effect of acetic acid and nitric acid on sol–gel synthesis showed that the acid influences the rate of the hydrolysis reaction, because the isoelectric point of the Titanium compound is around pH 6.8 and being at lower pH due to the action of the acid, electrostatic repulsion is promoted causing the formation of colloidal particles in the sol from around 8 to 100 nm until equilibrium is reached depending on the acid concentration [,,,,]. Thus, the addition of acetic acid in the ten syntheses regulated the rate of hydrolysis of Titanium alkoxides (TTIP), favoring the onset of gel condensation and preventing the sol from precipitating at pHs ranging between 4.0 and 5.0, as demonstrated by Sasirekha et al. [] in the study where they tested acidic and basic pH in a sol–gel solution []. Especially for synthesis S1, S4, S6 and S9, where four sols formed and did not precipitate, a viscosity increase occurred as the maturation time (five days) elapsed. The increases in viscosity for this synthesis suggest that the gel formation initiates, but the gelation was not complete as they were fluid enough to be used in the production of TiO2 films and improved adhesion to the glass substrate associated with the percentage of mass detached from films after the annealing process at 450 °C (Table S2). In the synthesis with low acetic acid concentrations (S7, S8, and S10), less stability of the sols occurred, precipitating after five days, like synthesis S2 and S3, which had lower amounts of water []. These results indicate that the addition of acid helps to control hydrolysis and condensation, but depending on the amount of water and solvent, a gel is generated and serves the TiO2 film elaboration.

Figure 2.

Coloring of the solutions of the 10 syntheses.

Additionally, another factor that interferes with the hydrolysis and condensation reactions is the interaction of the TTIP with ethanol—because they form dimeric or trimeric species given the physicochemical properties of the metal, such as the electronegativity of Titanium and ethanol, characterized by forming clusters and or oligomers through oxo bridges in conjunction with oxidizing agents leading to faster hydrolysis and condensation reactions []. The growth of crystalline domains during hydrolysis and condensation depends on the amount of reactive OH species and increases until all tetra-isopropoxide groups are depleted, thus allowing oxide formation by continuous condensation of the hydrolyzed species; however, when there are not enough ligands in the reaction, the condensation process stops, and as a consequence no ordered crystalline domains are present, as in the conventional sol–gel method in S5–S10 synthesis [,].

Concerning the ethanol solvent concentration, it is necessary to homogenize the hydrolysis reaction mixture that occurs when using alkoxides, especially at the beginning of the reaction. The polarity, dipole moment, viscosity, and protic behavior of ethanol influence the reaction rates and, thus, the final structure of the TiO2 film. Polar and especially protic solvents, such as water, alcohols, and formamides, stabilize polar species such as [Ti(OR)x(OH)y]n by hydrogen bonds, playing a crucial role in sol–gel synthesis [,].

The best concentrations were those evaluated in synthesis S1 and S4 (0.5 and 5.0 M). The presence of H2O2 (0.2 M) as an oxidizing/peptizing agent, generated in synthesis S1, S3, and S4, allowed the formation of three yellow-colored sols; this coloring was due to the presence of the Peroxo–Titanium complex, which results from the reaction of Titanium alkoxide with hydrogen peroxide generating peroxotitanate acid ([Ti(OH)3O2]−), reducing Ti(IV) to Ti(III) and releasing oxygen during the hydrolysis reaction [,,,] (Figure 2). As reported by Yaemsunthorna et al. [], the Peroxo–Titanium bonds enhance the stability of the Titanium complex, allowing the continuous hydrolysis reaction and condensation in the formation of TiO2 and avoiding the precipitation of the solution forming a solution with amorphous properties []. According to Garcia et al. [], after a low-temperature calcination process, the TiO2 formed in the Peroxo sol–gel solution can be converted into crystalline TiO2 in the anatase phase, compared to the conventional sol–gel method which requires higher crystallization temperatures, for the removal of unreacted organic compounds or by-products of the hydrolysis and condensation reactions [,,,]. However, in the S2 synthesis, the low H2O2 concentration (0.02 M) did not allow the formation of the Peroxo–Titanium compound because the solution precipitated and its coloring, instead of yellow was white and opaque, similar to the S5–S10 synthesis that did not contain H2O2 (Figure 2) [].

In the case of synthesis S5–S10 prepared with the conventional sol–gel method, it is evident that the hydrolysis reaction between TTIP and ethanol in the presence of water allows the formation of Titanium hydroxides, making the reaction to advance rapidly, giving rise to an incomplete condensation reaction for the formation of O-Ti-O bonds; therefore, the acidification of the solution with acetic acid allowed the protonation of the hydroxyl groups avoiding precipitation, by altering the surface charges of the amorphous Titanium hydroxide leading to the breaking of the oxo bonds, to the surface protonation of the particles formed in the condensation reaction as evidenced in the S6 treatment, which obtained better crystallization of TiO2 after the thermal process [].

Finally, synthesis S1 (0.1 M TTIP precursors, 0.5 M ethanol, 0.05 M acetic acid, 0.2 M hydrogen peroxide, and 1.28 M deionized water) showed increased adhesion to the substrate due to the interaction of the doubly coordinated OH groups, resulting from the cleaning of the substrate and the chemical treatment (3H2SO4:1H2O2), with the Ti atoms of the solution with the TTIP precursor [,], in the deposition of the solution by oxygen vacancies that allowed the formation of hydrogen bridge bonds, caused by the electrostatic interaction of the silanol Si-OH groups of the substrate surface with the TTIP solution [,], measured by the amount of deposited mass (Table S2).

2.3. TiO2 Film Characterization

2.3.1. X-Ray Diffraction

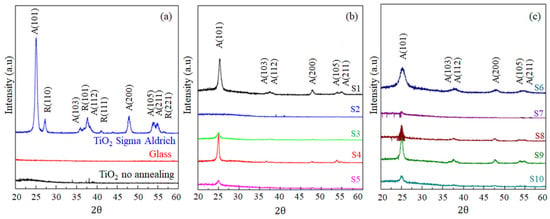

Figure 3a shows the diffractograms for the glass substrate, the amorphous Titanium deposited before annealing and the commercial TiO2 from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) in the Anatase (A) 80% and Rutile (R) 20% phases (Figure 3a–c). Figure 3b,c show the diffractograms of the ten syntheses after annealing at 450 °C, with which it was possible to identify the diffraction pattern of the anatase crystalline phase-oriented at characteristic angles (25.2 ± 0.2)°, (36.8 ± 0.2)°, (47.8 ± 0.2)°, and (54.2 ± 0.2)° with the diffraction planes (101), (103), (200), and (105), respectively []. The films were prepared with the ten combinations of reagents by sedimentation and evaporation at 100 °C, all of them were amorphous or non-crystalline, and when the heat treatment or annealing was at 450 °C, TiO2 was formed with variable crystallinity in all the films except for those obtained with S2, where the combination of Titanium alkoxide precursors with the solvents, triggered hydrolysis and condensation reactions, leading to the suspension of colloidal particles that affect the physical and structural properties of TiO2 films [,,].

Figure 3.

X-ray diffraction pattern of TiO2 films prepared with different mixtures of precursors by the sedimentation technique and annealing at (450 ± 1) °C for one hour. (a). TiO2 Sigma-Aldrich, Glass substrate and TiO2 without heat treatment (b). S1–S5 and (c). S6-S10, films of the ten syntheses were annealed at (450 ± 1) °C for one hour.

The crystallization rate of TiO2 is under the influence of many factors such as temperature, heating rate, and atmosphere []; consequently, it is remarkable the thermal processes necessary for the formation of TiO2 in the anatase crystalline phase, where the initial evaporation process occurs at 100 °C, which allows the loss of water and ethanol. This is followed by the decomposition of Peroxo groups and volatile acetic acid components leading to crystallization at 450 °C for the anatase phase of TiO2, as a consequence, the formation of O-Ti-O bonds in the hydrolysis and condensation reactions are responsible for the particle size and composition of Titanium oxide []. The syntheses that presented the highest intensity of the anatase phase (101) after the annealing process at 450 °C [] were S1 and S4, with intensity values in the (101) plane of 915 a.u and 684 a. u, respectively, and lower intensity values in the (103) planes, the intensity in S1 was 123 a. u and S4 106 a.u; in the (200) plane, the intensity of S1 was 143 a.u and S4, 110 a.u; and in the (105) plane, the intensity for S1 was 104 a.u and S4, 108 a.u (Figure 3a and Table S2).

Having calculated the crystallite grain size ranging from (60.1 ± 0.2) nm to (65.5 ± 3.3) nm (Table S2) for the synthesis that had the crystalline phase oriented in the (101) plane, along with the intensity value in this plane, with three replicates per synthesis []. According to the report of Ge et al. [] and Kassahun et al. [], the crystallite size affects the photocatalytic activity of the semiconductor because a small crystallite increases the surface area with more active sites of the charge carriers increasing the adsorption of reactants on the photocatalyst decreasing the electron–hole pair recombination of the photogenerated electrons [,]. As for the synthesis S5, S6, S7, S8, and S10, synthesized by the conventional sol–gel method, they present peaks with very low intensity of the anatase 101 phase at low concentrations of acetic acid and amounts of water, suggesting the presence of Titanium but with low crystallinity; so, the crystallite size was not be calculated. On the other hand, in the case of S6 and S9, the intensity in the (101) plane was higher than in the previous syntheses but lower than S1 and S4 so that the crystallite size could be calculated (Table S2).

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed significant differences in the intensity of the anatase crystalline phase with respect to the (101) plane family among the ten TiO2 syntheses (S1–S10) (p < 0.001), explaining 91.7% of the total variability (R2 = 0.9171). Tukey’s post hoc test confirmed that synthesis S1 exhibited the highest mean value, being significantly greater than all other syntheses. Synthesis S4 occupied an intermediate position, with values significantly higher than S2 and S3 but lower than S1. Syntheses S6 and S9 formed a low–intermediate group, whereas S2, S3, S5, S7, S8, and S10 showed no significant differences among them and were clustered at the lowest level. Overall, the results indicate the presence of four homogeneous groups (a, b, c, and d), reflecting consistent differences in the measured response across the evaluated syntheses (Figure S1).

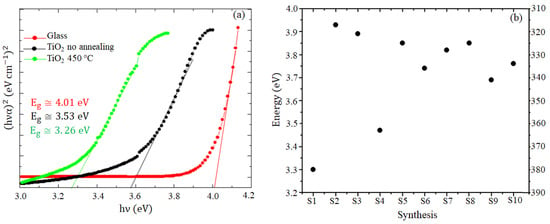

2.3.2. Determination of the GAP

Figure 4a shows the absorbance to determine the forbidden bandwidth of the glass substrate with value of 4.01 eV = 309 nm, the TiO2 before heat treatment with value of 3.53 eV = 351 nm, and the TiO2 film after heat treatment for T1 with value of 3.26 eV = 380 nm; extrapolation of the tangent line to the curvature allows us to obtain the abscissa intercept (eV), as shown in the chart, to identify the values corresponding to the bandgap energy of the semiconductor.

Figure 4.

UV-VIS spectroscopy characterization for thin film for the 10 syntheses (a) Absorbance to extract the band gap for glass (red), TiO2 not annealed from S1 synthesis (black), 450 °C annealed TiO2 from S1 synthesis (green) and (b) S1–S10 band gap values with 450 °C annealing.

The decrease in bandgap energy of the S1 synthesis film could be due to effects on the combination of the precursor with surface interaction and TiO2 particle size (quantum size effects and quantum effects), as reported by Yaemsunthorna et al. [], proving that increasing annealing temperature decreases the bandgap due to structural changes from amorphous to crystalline TiO2, which also increases the packing density of TiO2 in Ti-Ti bonds, the main reason for the gap reduction [,]. According to Manickam et al. [], the absorption spectrum of TiO2 has a shift towards a longer wavelength or lower energy as a function of increasing temperature due to the particle size-dependent electronic transition of TiO2 [,] and rearrangement of atoms in the crystal structure, indicating that the increase in crystallite size with temperature generates a change in refractive index [].

These results agree with the characteristics of the anatase crystalline phase semiconductor, which should be in the range of 3.20 eV to 3.37 eV []. Additionally, Figure 4a presents the corresponding band gap values of the ten syntheses, observing an increase in the band gap energy in synthesis S2 (3.93 eV = 315 nm), S3 (3.87 eV = 320 nm), S4 (3.54 eV = 350 nm), S5 (3.85 eV = 322 nm), S6 (3.75 eV = 330 nm), S7 (3.81 eV = 325 nm), S8 (3.84 eV = 323 nm), S9 (3.66 eV = 338 nm), and S10 (3.75 eV = 329 nm), which may be due to the combination of quantum size effects due to the change in TiO2 particle size and surface interaction in addition to the crystallinity of the films.

2.3.3. SEM/EDX

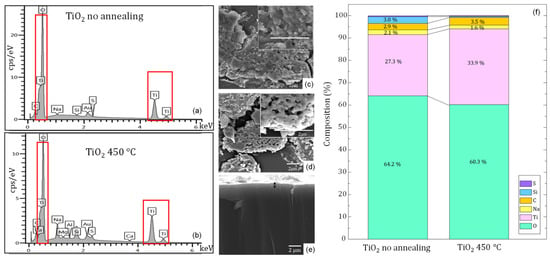

The EDX analysis made it possible to identify the elements present in the S1 film and their distribution on the surface during the semi-quantitative evaluation. The film had a thickness of approximately 1 μm, as reported in Figure 5e. Elemental mapping, carried out before and after the annealing process, showed the presence of Titanium (33.87%) and oxygen (60.24%), which correspond to the atomic percentages on the TiO2 film surface after heat treatment. In addition, small amounts of silicon (0.40%), sodium (1.64%), carbon (3.50%), and sulfur (0.40%) were detected, mainly originating from the glass substrate. Gold signals were also identified, associated with the coating applied to the sample for its observation and measurement. These results are shown in Figure 5a,b,f [,].

Figure 5.

EDX spectra and SEM micrographs of TiO2 films prepared by the sedimentation technique (S1): (a,c) film without annealing; (b,d) film annealed at 450 °C for 1 h, the presence of titanium is shown in the red box; (e) cross-sectional view showing film thickness; and (f) EDX elemental composition (%).

Finally, in Figure 5c,d, the SEM morphology of the surface of the S1 synthesis films before and after annealing showed a rough surface, with cracks and agglomerates of sizes ranging between 1.5 and 3.0 µm; the grain size distribution can be associated with the evaporation and annealing process in the fabrication of the films, as reported by Fernández et al. []. In addition, observations with a stereoscope at 40 X magnification of the ten-film synthesis (Figure S2) showed low adherence of the Titanium to the substrate due to the detachment of the film in S2, S5, S7, S8, and S10. At S3, S4, S6, and S9 films the coating was not uniform; in contrast, S1 films did not show a homogeneously complete substrate coating. Coating after annealing was not homogeneous on the glass; in contrast, S1 films showed a complete substrate coating distribution with a rough surface [].

The increase in the intensity of the diffraction peak (101) of TiO2 in the anatase phase and the decrease in the peak amplitude (Figure 3), suggests that the formed TiO2 is composed of irregular polycrystalline structures, Figure 5c,d, which have an effect on the bandgap energy of TiO2 Figure 4b, as indicated by Bandgar et al. [] and Rahmati et al. [], because there is a higher density of states at the Fermi level allowing the formation of charge carriers (electron–hole pairs) on the semiconductor surface with a longer lifetime due to the indirect electronic transition that reacts with water, producing free radicals with high oxidizing power [,,,].

2.4. Inactivation of E. coli 226 and S. Typhimurium 211 in Grey Water (GW)

2.4.1. Strains for Study, Preservation, and Growth Curves

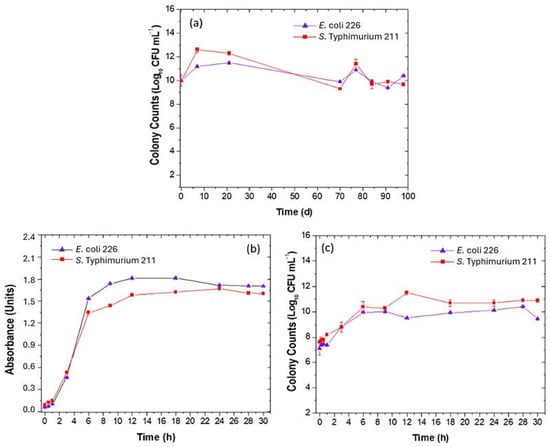

The stability results of the Master Cell Banks (MCBs) of both bacteria (E. coli 226 and S. Typhimurium 211) showed that preservation at −20 °C using 30% (w/v) glycerol was an appropriate cryoprotectant and did not affect viability. Counts for E. coli ranged from (10.0 ± 0.5) to (11.50 ± 0.07) Log10 CFU mL−1. For S. Typhimurium the counts ranged between (10.00 ± 0.05) and (12.6 ± 0.2) Log10 CFU mL−1 (Figure 6a).

Figure 6.

Growth and stability curve of Escherichia coli 226 and Salmonella Typhimurium 211 banks. (a) Number of colonies as a function of time days, (b) absorbance as a function of time, and (c) colony count (CFU mL−1) as a function of time (h).

At the growth curve for E. coli 226 (followed by OD 540 nm and colony count (Log10 CFU mL−1), a Log phase of 1 h occurred, and the exponential growth phase finished after nine hours, with a count of (9.990 ± 0.054) Log10 CFU mL−1. The stationary phase was excised between 12 and 28 h with the death phase (Figure 6b,c).

The behavior of S. Typhimurium 211 in the growth curve was different to E. coli 226; the Log phase was 30 min and the Log phase extended up to 12 h, with a count of (10.70 ± 0.24) Log10 CFU mL−1; the stationary phase finished at 30 h (Figure 6b,c).

Based on the growth curves results, to produce E. coli 226 and S. Typhimurium 211 inoculum, the culture time conditions were 12 h, 30 °C, and 200 r.p.m., before inoculation in GW1 and GW2 to evaluate photocatalysis.

2.4.2. Greywater (GW) Characterization

The first GW (GW1) used in this study had an alkaline pH (8.6 ± 0.5), high TSS (total suspended solids) concentration (80 ± 18) mg L−1, light yellow color, and slightly elevated COD and BOD5 concentrations (320 ± 34) and (160 ± 20) mg L−1. The BOD5/COD treatability ratio was (0.51 ± 0.12), a value higher than 0.5, suggesting that GW has potentially biodegradable organic matter to be oxidized by photocatalysis (Table 1). Associated with the nitrogen cycle intermediates, NH4+, NO2−, and NO3− concentrations were detected, with ammonium having the highest concentration (17.33 ± 8.38) mg L−1, which could be related to the presence of proteins, urea, and disinfectants derived from quaternary ammoniums, among others. The concentrations of SO4− and H2S generated unpleasant odors, especially H2S, which were detected with values (26 ± 3) mg L−1 and should be less than or equal to 1.5 mg L−1 [], (Table 1).

Table 1.

Physical, chemical, and microbiological characterization of GW.

Concerning the presence of microorganisms in the GW, being domestic wastewater, total heterotrophic bacteria (5 × 105 CFU mL−1), total fungi (6.0 × 105 CFU mL−1), total coliforms (3.0 × 104 CFU mL−1), Escherichia coli (8.0 × 103 CFU mL−1), and Salmonella spp. < 100 CFU mL−1 were not detected (Table 1).

The second GW (GW2), used to evaluate only the TiO2 films with the best synthesis protocol S1, had a similar composition to GW1, especially for H2S and PO4 (Table 1). However, the pH was acidic (5.1 ± 0.1) and had lower concentrations of NH4+ (0.45 ± 0.01) mg L−1, NO3− (0.10 ± 0.01) mg L−1, and SO4− (2.0 ± 0.1) mg L−1. In contrast, the initial COD concentration was higher (540 ± 1) mg L−1, and regarding the counts for bacteria and total coliforms, the values obtained were 3.0 × 104 and 1.0 × 104 CFU mL−1 (Table 1).

2.4.3. Evaluation of the Photocatalytic Activity of TiO2 Films Produced with the Ten Synthesis Protocols Using GW1

The use of different first [,,], second [,,,], and third generation [,,], semiconductor materials for the treatment of domestic and non-domestic wastewater, including the removal of organic matter (COD and BOD), nutrients (nitrogen and phosphorus), offensive odors (H2S), and inactivation of bacteria of fecal origin [,,,,], involves both the synthesis of semiconductors, their characterization and their evaluation either at the laboratory, pre-commercial, or commercial scale [,,]. To satisfactorily fulfill this evaluation, studies involved synthetic wastewaters that allow greater control of the process and study the effect of individual pollutants on the photocatalysis process [,]. However, the challenge is also to demonstrate that semiconductors such as TiO2 are functional in the presence of mixtures of pollutants such as those present in “real” wastewater. Because the precise content of organic matter, nutrients, ions, turbidity, solids, and different kinds of micro-organisms can affect light absorption, semiconductor photoexcitation, generation, and the half-life of oxidizing species [,]. If a semiconductor with high photocatalytic activity reaches a successful treatment of this type of wastewater, a technological and environmental limitation is solved to the extent that it can be coupled with other conventional treatment systems to improve water quality, reduce processing times, and open the possibility of reuse. This aspect is relevant due to a decrease in the quantity and quality of water resources because of global warming, climate change, and pandemics [,].

For this reason, two batches of “real” domestic wastewater evaluations are in the present study, the first for the selection of the best TiO2 synthesis protocol and the second aims to demonstrate that the TiO2 films from the S1 synthesis had photocatalytic activity when evaluated with different wastewater and monitors an extensive parameter number.

Once E. coli 226 and S. Typhimurium 211 were simultaneously inoculated into the sterile wastewater, the resulting chemical and microbiological parameters were pH (5.0 ± 0.5), COD 530 mg L−1, E. coli 226 concentration (6.2 ± 0.3) Log10 CFU mL−1, and S. Typhimurium 211 concentration (6.65 ± 1.00) Log10 CFU mL−1. With these initial values, COD inactivation and removal experiments started.

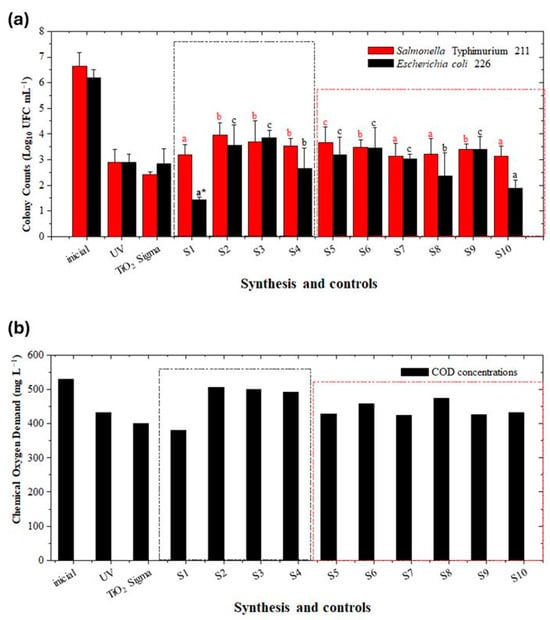

Under the experimental conditions evaluated in this study, when using the combination of reagents to obtain TiO2 films with photocatalytic activity against E. coli 226 (synthesis S1–S4), only protocols S1 and S4 showed significant differences (p < 0.05) compared to the controls with UV253 nm photolysis and photocatalysis using commercial Sigma TiO2. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) performed on the bacterial inactivation data of E. coli and S. Typhimurium for the 10 TiO2 syntheses (S1–S10) revealed statistically significant effects for the interaction, the row factor associated with the bacterial strain and the column factor corresponding to the treatments and controls. The column factor explained the largest proportion of the total variation (43.47%, p < 0.0001), followed by the interaction factor (16.72%, p = 0.0294) and the row factor (6.7%, p = 0.0029). These results demonstrate that the S1 synthesis had statistically significant differences with respect to the other treatments and controls, while the difference in the average bacterial inactivation between E. coli (53.43%) and S. Typhimurium (47.84%) was 5.59%, with a 95% confidence interval of 2.01 to 9.16, confirming a significant effect attributable to the type of bacteria (Table S3). The lowest E. coli concentration occurred in synthesis S1 and S4 (1.44 ± 0.10) and (2.65 ± 0.8) Log10 CFU mL−1 for a decrease of 4.76 and 3.55 Log10 in 30 min at pH 5.0, respectively, (Figure 7a).

Figure 7.

Bacterial inactivation results correspond to an average of three replicates with their respective standard deviations. E. coli 226 (black) and S. Typhimurium 211 (red) in the ten syntheses and control by UV photolysis and TiO2 Sigma-Aldrich. (a) Colony count (Log10 CFU mL−1) as a function of the synthesis and controls, the letters above the bars identify the significant differences between synthesis, with the letter a* identifying the most significant. (b) COD concentration (mg L−1) as a function of the synthesis and controls. The black box shows the Peroxo sol-gel treatments and the red box the Sol-gel treatments.

For synthesis S2 and S3, a final E. coli concentration of (3.56 ± 0.8) and (3.84 ± 0.3) Log10 CFU mL−1 was obtained (decrease of 2.64 Log10 and 2.36 units in 30 min at pH 5.0) but did not exceed the controls evaluated (p > 0.05). Bacterial inactivation could be attributed mainly to the effect of UV light, and to a lesser extent, to the formation of a film on the substrate, but of TiO2 in the process of crystallization for S2 and with low crystallinity for S3, noting that anatase phase (101) was uniquely detected and the grain size could not be estimated (Figure 7b).

On the other hand, when analyzing the E. coli inactivation at synthesis S5–S10, in which reagents and synthesis conditions stayed focused on the conventional sol–gel method, only synthesis S8 and S10, outperformed the controls, obtaining (2.36 ± 0.9) and (1.9 ± 0.3) Log10 CFU mL−1 after 30 min of treatment (decrease of 3.84 Log10 and 4.3 units). The films obtained for these syntheses had crystalline TiO2, with the presence of anatase phase with the (101), (103), (200), and (105) planes, but with lower intensity if compared to the films of synthesis S1 and S4, synthesized by the Peroxo sol–gel method (Figure 3b,c). For syntheses S5, S6, S7, and S9, a decrease in E. coli concentration concerned the initial value (6.2 ± 0.3) Log10 CFU mL−1 but did not exceed the controls. Final concentrations of (3.18 ± 0.7), (3.44 ±0.8), (3.02 ± 0.2), and (3.41 ± 0.5) Log10 CFU mL−1 were obtained for S5, S6, S7, and S9, respectively, (Figure 7a). Anatase phase (101) occurred in S5, S6, and S9 films, but the intensity was lower than those obtained in S1 and S4; in the S7 film, the anatase phase 101 tried to form but the signal was not clearly defined. Therefore, a large part of the inactivation could be associated with UV photolysis and a smaller proportion with the photocatalysis effect.

Regarding Salmonella Typhimurium 211, the results obtained in this study were contrasting when compared to the literature, as authors such as Kim et al. [] and Shahbaz et al. [] reported that this bacterium is more sensitive than E. coli to inactivation using advanced oxidation processes [,]. A decrease in the initial concentration of Salmonella Typhimurium 211 (6.65 ± 1.00) Log10 CFU mL−1 occurred in all syntheses (S1–S4 Peroxo sol–gel method and S5–S10 conventional sol–gel method); none of the syntheses exceeded the UV photolysis and Sigma TiO2 controls (final concentration: (2.90 ± 0.30) and (2.42 ± 0.10) Log10 CFU mL−1, respectively), (Figure 7a). Therefore, for this bacterium, other factors associated with the bacterium itself or with the initial concentration could have masked the photocatalysis process and were not directly related to the crystallinity of the TiO2 films and their photocatalytic activity.

The statistical differences observed between E. coli and S. Typhimurium can be explained by structural and biochemical distinctions between the two species. Although both are Gram-negative, Salmonella generally exhibits a denser and more rigid outer membrane, largely due to variations in lipopolysaccharide composition and the presence of outer membrane proteins such as the O antigen []. In addition, Salmonella expresses the porins OmpC, OmpF, and OmpD; the latter is genus-specific and reduces membrane permeability, thereby increasing resistance to chemical compounds and oxidative stress [].

Moreover, Salmonella possesses more efficient antioxidant defenses than E. coli. For instance, it can produce hydrogen sulfide from thiosulfate, which protects cells by inhibiting Fenton reactions through Fe2+ sequestration and by stimulating the synthesis of antioxidant enzymes such as catalase (EC 1.11.1.6) and superoxide dismutase (EC 1.15.1.1) [,]. These enzymes are upregulated in the presence of antibiotics or reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by TiO2.

Recent studies on the antimicrobial activity of TiO2 confirm this trend. Park et al. [] reported statistically significant differences in the inactivation of E. coli and Salmonella on black pepper using UV-A/UV-C radiation combined with TiO2 coatings, achieving reductions of 4.84 and 3.77 Log10 CFU mL−1, respectively []. Similarly, Moncayo-Lasso et al. [] observed that under identical conditions, E. coli was reduced by 6 Log10 CFU mL−1 after 120 min, whereas S. Typhimurium showed only a 3 Log10 CFU mL−1 reduction [].

Finally, photocatalyst characteristics also influence bacterial responses. The photochemical efficiency of TiO2 determines ROS generation and availability, affecting the extent of cell damage. Yong et al. [] demonstrated that ROS accumulation during TiO2 photocatalysis triggers lipid peroxidation and membrane disruption, with hydroxyl radicals (•OH) playing a predominant role compared to H2O2 and •O2− []. Nevertheless, other studies with pristine and doped TiO2 confirm that S. Typhimurium maintains higher resistance than E. coli, attributed to the presence of detoxifying enzymes and reducing compounds that neutralize ROS and repair oxidative damage [,].

The oxidation of organic matter can be slower than bacterial inactivation and requires longer treatment time. A decrease in COD for all synthesis occurred (UV photolysis and TiO2 Sigma); however, S1 was the synthesis with the extended decrease with a final concentration of 380 mg L−1, a lower value than UV photolysis (433 mg L−1), which suggests that the combination of precursors for obtaining TiO2 films with S1 (Peroxo sol–gel method: 0.1 M TTIP, 0.5 M ethanol, 0.05 M acetic acid, 0.2 M H2O2, and 1.28 M H2O) and the heat treatment at 450 °C favored the formation of crystalline TiO2 with anatase having effects on the photocatalytic activity of the semiconductor. When TiO2 is irradiated by UV light, the valence band electrons move towards the conduction band, allowing the formation of photogenerated charge carriers, which are transported at the TiO2/GW interface. Reacting with the water molecules, the photogenerated e− reduces O2 producing the superoxide radical anion (O2−•) and the photogenerated h+ oxidizes H2O resulting in the •OH radical being a powerful oxidizing agent that allows the degradation of organic matter (Figure 7b) [].

Finally, measurements of the initial and final pH of the GW used for the bacterial inactivation and COD removal tests showed that initially, the GW had a pH of 5.0, and at the end of each treatment (after 30 min.), an increase in approximately three units was observed for all ten syntheses and one unit for the UV photolysis control. These increases in pH values were responsible for the release of bacterial intracellular components and the formation of ions at the expense of the oxidation of organic matter such as sulfates, ammonium, and orthophosphates.

In the present study, although the GW used did not present such high concentrations of solids, organic matter, nutrients and bacteria, if compared to what is reported by other authors such as Gandhi and Prakash [], Moreno et al. [], and Zawadzki et al. [], who published physical, chemical, and microbiological characterizations for domestic and municipal wastewater [,,], it did present concentrations of TSS, COD, BOD5, NH4, H2S, and E. coli counts over the maximum permissible values according to Colombian and US regulations (Table 1). This means that the GW used for this research was not been treated before being discharged, either by biological or physical/chemical processes [,]. In this sense, advanced oxidation processes such as TiO2 photocatalysis and UV photolysis are viable and efficient alternatives which have been extensively studied [,,]. However, for these processes, the types and concentrations of contaminants present in the wastewater directly affect their removal and inactivation efficiency [,,], especially the “in situ” production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) mainly responsible for oxidizing organic matter and inactivating microorganisms, to produce CO2, H2O, and a variety of inorganic ions []. Therefore, the presence of TSS, COD, BOD5, NH4, H2S, and bacteria in slightly increased concentrations, as detected in the present study, could affect the process of TiO2 photocatalysis and UV photolysis, basically because they generate a decrease in the passage of ultraviolet light, competition of ions for the active sites of TiO2, and bacteria in high concentrations can coat the films preventing the photoexcitation of the semiconductor to take place [,,,].

For the inactivation experiments with E. coli 226, in the synthesis that outperformed the control with UV253nm photolysis, the TiO2 photocatalysis process occurred, irrespective of whether sol synthesis and films were through the Peroxo sol–gel method (S1 and S4) or by the conventional sol–gel method (S8 and S10) produced. All four syntheses reached crystalline TiO2 in the anatase phase, with the (101) plane being the preferred orientation; however, the intensity of the anatase phase varied between synthesis (Figure 3b,c). The presence of a single phase (anatase) was related to the heat treatment of 450 °C for one hour, as temperatures below 600 °C favored the formation of this phase and temperatures above 600 °C favored a transition to rutile phase [,]. On the other hand, having crystalline TiO2 decreases the recombination process of the photogenerated charge carriers, while in amorphous or low-crystallinity TiO2, the structural defects of the material form recombination centers [], affecting the efficiency of the photocatalysis process because photoexcited electrons in the conduction band return to the valence band and the production of reactive oxygen species involved in the inactivation of bacteria and oxidation of organic matter decreased [].

Regarding E. coli 226, the heterogeneous photocatalysis process decreased the initial concentrations of E. coli 226 (6.2 ± 0.3) Log10 CFU mL−1 and COD (530 mg L−1). To finish with (1.4 ± 0.9) Log10 CFU mL−1 and a COD of 380 mg L−1 (Figure 7a,b); this represents a colony decrease of 4.8 Log10 CFU mL−1, for E. coli 226, especially using the combination of reagents in synthesis S1 (Peroxo sol–gel method). These data were similar to those obtained by Nyangaresi et al. [], who employed LED light in the photocatalysis process with TiO2, achieving a reduction of 4.1 Log10 CFU mL−1 of E. coli []. These results were related to several mechanisms, the first one concerning the presence of crystalline TiO2 in the anatase phase (S1); this phase is more reactive and favors the semiconductor photoexcitation process when compared to an amorphous material or with a mixture of crystalline phases [,]. Authors such as Varnagiris et al. [] demonstrated that the inactivation of S. Typhimurium was more successful (initial concentration 1 × 109 CFU mL−1) when using C-doped anatase-phase TiO2 than when using the same catalyst but one that was amorphous. The authors suggest that having anatase-phase TiO2 produces more reactive oxygen species than amorphous TiO2, and these species can induce bacteria to produce internal ROS, which causes additional cell damage. Both external and internal ROS alter membrane permeability and oxidation of phospholipids that form the membrane lipid bilayer []. The second reason could be related to the size of anatase-phase TiO2 crystals and their larger surface area [].

The present investigation showed that when preparing TiO2 films by the Peroxo sol–gel method employing the S1 precursor mixture, the anatase phase achieved crystal sizes of (60.1 ± 0.2) nm; this value suggests that the particle size is small and could increase the surface area. By having a larger surface area, more H2O adsorbes to TiO2, and when reacting with the photogenerated holes, favors the production of •OH radicals that participate in the oxidation of organic matter and cause cell damage in microorganisms [,]. Ahmed et al. [] synthesized a type of anatase-phase TiO2 with a high specific surface area using a novel one-step method, employing microwave and hydrothermal methods. The authors reported that as the particle size decreased, the surface area increased, hydroxyl groups were generated and favored the inactivation of E. coli starting from concentrations of 1 × 108 CFU mL−1 in one hour of treatment [], a situation also reported by Lin et al. [], which found that particles smaller than 11 nm were more efficient in inactivating E. coli [].

For S. Typhimurium 211, a decrease in the initial concentration (6.65 ± 1.0) Log10 CFU mL−1 was observed in all synthesis but did not exceed the UV253 nm photolysis control. Only with S1 (Peroxo sol–gel method) the final concentration was close to that obtained with UV light (Figure 7a). These results suggest that although Salmonella Typhimurium 211 is a Gram-negative bacterium like E. coli, it might have some differences and more efficient cellular self-repair mechanisms than E. coli because during the 30 min treatment the cells recovered and did not achieve the same inactivation as that obtained with E. coli []. Especially for the synthesis obtained by the Peroxo sol–gel method (S1 and S4) and conventional sol–gel (S8 and S10), in which the inactivation of E. coli was superior and was related to the physical characteristics of the films, such as the crystallinity of the anatase phase, the size of the crystals, and the value of the band GAP. On the other hand, this bacterium, being resistant to several antibiotics [], could also have or develop mechanisms of resistance or adaptation to reactive oxygen species, a process similar to what happens when Salmonella is found in open environments and exposed to solar radiation that has a certain percentage in the ultraviolet region or comes into sporadic contact with strongly oxidizing compounds such as chlorine-based disinfectants, peracetic acid, and quaternary ammonium, among others [,]. Additionally, the initial inactivation concentration could affect the inactivation process by photocatalysis as it was slightly higher than for E. coli. At high concentrations, some cells are not damaged by ROS because, by shielding between cells generated, the cells more exposed to ultraviolet light protect the cells in the inner part of the wastewater []. Having not obtained similar results to E. coli, further studies are necessary to evaluate lower cell concentrations and prolong the exposure time. Authors such as Lelis et al. [] reported that the appropriate concentration to inactivate is about 1 × 104 CFU mL−1 with a treatment time longer than two hours [].

Finally, the decrease in COD concentration was lower than the bacterial inactivation in all syntheses because polymeric compounds, detergents, and disinfectants (not quantified in the initial characterization) could be present in the wastewater. These pollutants require more time and effort for mineralization into CO2 and water. On the other hand, ions such as phosphates, bicarbonates, nitrates, and sulfates can act as interference in the oxidation process of organic matter [].

2.4.4. Photocatalytic Activity Evaluation of the TiO2 Films Produced Using the Most Promising Synthesis Protocols, Employing GW2 on a Larger Scale

Table 2 shows the initial and final chemical and microbiological characteristics of the GW2 used to re-evaluate the TiO2 films produced with the S1 synthesis protocol (Peroxo sol–gel method). After 120 min of photocatalysis, the concentrations of COD (367 ± 15) mg L−1, NH4 (0.046 ± 0.002) mg L−1, H2S (2.600 ± 0.003) mg L−1, E. coli (<1.0 CFU mL−1), and Salmonella (<10 CFU mL−1) decreased. On the other hand, increases in NO3 (0.40 ± 0.01) mg L−1 and SO4 (6.6 ± 1.1) mg L−1 concentrations were observed.

Table 2.

Physical, chemical, and microbiological characterization of GW2 used to evaluate the photocatalytic activity of TiO2 films prepared by the S1 synthesis protocol on a larger scale.

Concerning the UV photolysis process, the values obtained were (410 ± 10) mg L−1 (COD), (0.12 ± 0.01) mg L−1 (NH4), (0.3 ± 0. 1) mg L−1 (NO3), (9.000 ± 0.001) mg L−1 (H2S), (2.8 ± 0.1) mg L−1 (SO4), (1.0 ± 0.1) CFU mL−1 (E. coli), and (10.0 ± 0.1) CFU mL−1 (Salmonella), (Table 2). In the adsorption control (TiO2 films in the dark and with aeration), a slight decrease in parameters such as COD, NH4, and H2S was observed, but they did not outperform photocatalysis and photolysis. The counts of the two bacteria were in the range of (1.5 × 104 and 4.0 × 103) CFU mL−1 for E. coli and Salmonella (Table 2). Finally, in the absolute control (GW without TiO2 and UV253nm, but with aeration), values similar to the initial values were obtained, which shows that the changes observed in each of the parameters analyzed are attributable to photocatalysis, photolysis, and to a lesser extent to dark adsorption of the TiO2 films (Table 2). The initial pH value was (5.1 ± 0.1), and after 120 min, an increase occurred in all the experiments, obtaining values of (8.3 ± 0.1), (8.2 ± 0.1), (8.1 ± 0.1), and (7.0 ± 0.1), respectively, for photocatalysis, photolysis, dark adsorption, and the absolute control (Table 2).

Under the experimental conditions, TiO2 films produced by the Peroxo sol–gel method (S1) had photocatalytic activity after 120 min of treatment when using GW2, whose chemical composition was like the first GW1 (Table 1). As in the first GW1 trials, the decrease in COD concentration was less than bacterial inactivation (Figure 7 and Table 2). These results suggest that to obtain complete mineralization to CO2 + H2O and inorganic intermediates, the amount of TiO2 and the photocatalysis time possibly need to be increased [,]. This situation could also be related to the chemical composition of GW1 and GW2, given that due to their domestic origin they may contain compounds such as polymers, carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins, among others, which, being part of the organic matter associated with the carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur cycles, are not oxidized or reduced in short periods and their concentrations, expressed globally as COD, will always be more difficult to remove when present in mixtures such as in “real” wastewater [,].

Concerning the individual evaluation of the nitrogen and sulfur cycle intermediates, the photocatalysis process decreased NH4 and H2S concentrations after 120 min, outperforming UV photolysis, adsorption, and what could be removed by aeration of the GW2 (absolute control) (Table 2). Associated with NH4+, the process could start with the adsorption of NH4+ onto the semiconductor, a step favored at pH above 7.0 []. Subsequently, photogenerated h+, •OH radicals, as well as other reactive species (superoxide radical O2•− and H2O2) oxidize NH4+ to NO2− and NO3− [,,]. Possibly for this reason, slight increases in NO3− concentrations occurred in the present research, especially in photocatalysis and photolysis (Table 2). Authors such as García-Prieto et al. [] reported that the oxidation of ammonium through photocatalysis can have a synergistic effect between the photolytic and photocatalytic processes, which favors its oxidation and higher NO3 production. On the contrary, during the photolysis process with different UV lamp types, the •OH radicals could oxidize NH4+ to form NH2, which reacts with more •OH radicals to produce NHOH and being an intermediate with low stability in water, it rapidly converts to NH2O2− and subsequently to NO2− and NO3− [,].

H2S concentration decreased with the TiO2 photocatalysis process and to a lesser extent with the photolysis process (Table 2). The changes in concentrations could be attributable to oxidation mediated by photogenerated holes and reactive oxygen species []. The removal or conversion of H2S present in wastewater, industrial waste, and biogas is feasible and starts with adsorption onto the catalyst, a process favored at alkaline pH [], followed by the oxidation of H2S to sulfur dioxide and sulfate. Sulfate is the desired intermediate, as sulfur dioxide is a gas that causes tissue irritation and can affect many aquatic and terrestrial organisms [,,]. On the other hand, it is remarkable that hydrogen production can result from the oxidation of H2S from domestic and industrial wastewater, resulting in an alternative fuel to petroleum derivatives [,].

Finally, the inactivation of E. coli and Salmonella was higher with the photocatalysis process compared to UV253nm photolysis, while in the adsorption and absolute controls, no decreases higher than one logarithmic unit occurred. When comparing the two types of domestic wastewater, inactivation was higher with GW2 (Table 1, Figure 7). These results suggest that using lower concentrations of the two bacteria and increasing the processing time favors bacterial inactivation because of low cells mL−1 exposed for a long time to different reactive oxygen species generating irreversible cell membrane, wall, lipids, respiratory chain, and genetic material damage after 120 min of photocatalysis. No secondary reactivation of the bacteria based on the activation of intracellular repair mechanisms occurred, demonstrating that TiO2 films produced by Peroxo sol–gel synthesis could serve for bacterial inactivation and pollutant removal in “real” wastewater.

Although the results obtained under the experimental conditions evaluated in this article are promising, they have limitations susceptible to improvement in several aspects; First, to favor the homogeneous deposition of TiO2 films using the S1 synthesis protocol, methods such as spin coating or dip coating could be used instead of sedimentation growth techniques. Second, increasing the sintering temperature above the one evaluated in this article, and below 600 °C, could improve the crystallinity of the film and promote the formation of other crystalline planes of the anatase phase. Third, the modification of GAP of TiO2 films by introducing nitrogen to make them functional at a wavelength close to the visible spectrum. Finally, using the same type of hydrophilic substrates as described in this article, larger dimension film production will allow scaling up of the photocatalysis process in larger capacity photoreactors that are coupled to other treatment units to integrate a functional pilot plant to treat domestic wastewater at different sites and help urban and rural communities to improve their water scarcity-related limitations; this would contribute to water resilience, responsible consumption, and the reuse of treated wastewater in activities that do not involve direct consumption by humans and animals.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Substrate Preparation

Commercial soda-lime glasses (SLIDES glass) with standard dimensions of 25.4 mm, 76.2 mm long, and 1.20 mm thick served as substrates. The substrates were washed and degreased following the protocol by Puentes et al. [], which consisted of first washing with alkaline detergent, followed by sonication cycles of 15 min 20 °C, following the sequence of immersion/sonication in MilliQ water, ethanol (99% v/v), acetone (99.5% v/v), and MilliQ water, with each solution measuring 15 mL [].

Subsequently, two methods served to modify and improve the hydrophilic surface of the substrate, as it had an initial hydrophilicity average of 42.1°. The first method was chemical, using a solution containing 98% (v/v) sulfuric acid (H2SO4) and 30% (v/v) hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in a 3:1 ratio. Substrates were then immersed in 3 mL of the solution for 20 min, rinsed with 15 mL MilliQ water in a 10 min sonication cycle, and dried at 102 °C for 3–5 min []. The second method was a physical one with ultraviolet (UV) light and employed a galvanized box (60 cm long, 50 cm wide, and 30 cm high) with 4 LTF S9-15W UV lamps with a wavelength of 253 nm []. Each substrate was placed inside the box horizontally at a 10 cm distance parallel to the UV lamps, and exposed to UV radiation for 20 min; later the lamps were turned off and the galvanized box was ventilated for 15 min.

To determine the effect of both modification protocols on the substrate (hydrophilicity), the measurement of the static contact angle [,,] was through four treatments and two controls, the first the substrate without washing and with no physical or chemical treatment and the second was substrate washed according to the protocol of Puentes et al. [] and untreated substrates (Table 3). Each treatment involved three substrates, in which three drops of water dripped on different substrate areas, and three images of the left and right angles were measured (test performed in triplicate). Finally, the angle measurements were statistically analyzed using SAS 9.0 for Windows to determine significant differences between treatments.

Table 3.

Selection of conditions for cleanliness and hydrophilicity of commercial glass substrates.

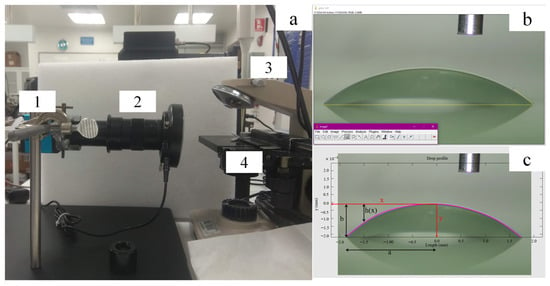

The static contact angle (SCA) measurement was according to ASTM []; the substrate was placed on a horizontal surface at a distance of 5 cm parallel to the optical microscope with 0.5× focus and a Hanwei camera (Figure 8a). A drop of distilled water (5.0 ± 0.1) μL was deposited on three different areas of the substrate. The ImageJ 1.54g software (Java 1.8.0_461), with a freely available Java programming language, was used; each image was calibrated by the number of pixels mm−1 using a needle of (0.31 ± 0.01) mm in diameter as a reference. Finally, Angle tool software (Java 1.8.0_461) allowed for left- and right-angle measurements in each image in Figure 8b [,,].

Figure 8.

Contact angle measurement. (a) Measuring equipment, 1. Camera, 2. Optical microscope, 3. Micropipette, 4. Sample holder (b) Angle measurement with ImageJ program. (c) Profile calculated with MATLAB.

Additionally, the MATLAB software (version R2023b) (with its matrix programming language for Windows) allows the calculation of the droplet profile in Figure 8c according to the Laplace–Young curve approximation (Equation (1)), where γ is the surface tension of water in N m−1, R1 and R2 are the two principal radii of the curvature at the surface in m, and ΔP is the pressure difference at the interface in Pa (Material S1, Figure S3) [].

Once the contact angles were measured (triplicate treatments and control), the average allowed the calculation of the decreasing percentage of both (right and left angles) compared to the natural hydrophilic substrate (control 1) (Equation (2))

3.2. Elaboration of TiO2 Films by Sol–Gel/Sedimentation

The selection of a chemical reagent mixture to generate the precursors for sol–gel and Peroxo sol–gel production involved the formulation of 10 syntheses or possible combinations (Table 4). The reagents considered were Tetraisopropyl Orthotitanate (TTIP) Ti[OCH(CH3)2]4 with molecular weight 284.22 g mol−1 Sigma-Aldrich, ethanol CH3CH2OH with molecular weight 46.07 g mol−1 Sigma-Aldrich, acetic acid CH3COOH with molecular weight 60.05 g mol−1, hydrogen peroxide H2O2 with molecular weight 36.01 g mol−1, and water Milli Q H2O molecular weight 1.00 g mol−1.

Table 4.

Precursor selection for the production of sol from Titanium alkoxides.

The synthesis was carried out in two 50 mL Schott flasks. In the first flask, solution A was prepared, which contained ethanol, shaken for 5 min, and then TTIP was added by drip and shaken for 30 min. The second flask contained solution B (with MilliQ water and acetic acid), for synthesis S6 to S10 by the conventional sol–gel method, and hydrogen peroxide was added to solution B, for synthesis S1–S4 by the Peroxo sol–gel method, according to the concentrations to be evaluated in each treatment and homogenized with agitation for 30 min.

Solution A was then dripped into solution B and stirred for 2 h in the dark; all homogenization processes were carried out at 250 rpm on a Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA USA) Cimarec SP88850105 Stirring Hot Plate at 20 °C. The mixture of solution A and B was referred to as solution C and varied according to the 10 evaluated syntheses (Table 4). The solutions were preserved at 20 C in the dark for five days; over the five days, the changes in the solutions in the ten treatments were observed qualitatively, concerning changes in the intensity of yellow (S1–S4) or white (S5–S10) color, precipitation, and viscosity [,,].

As a commercial control for the semiconducting oxide, TiO2 dispersion preparation followed the protocol described by Villanueva et al. [] containing 0.5 g of commercial Sigma-Aldrich TiO2 with molecular weight 79.87 g mol−1 in Anatase (80%)—Rutile (20%) phase, particle size < 100 nm and purity of 99.5%, 25 mL distilled water, and 350 μL of 63% (v/v) nitric acid (HNO3) with pH (2.0 ± 0.2) of the solution [], this mixture was prepared by first mixing the distilled water with the nitric acid in agitation for five minutes; then, it was added the TiO2 powder, then the solution was agitated at 250 rpm in Thermo Scientific Cimarec SP88850105 Stirring Hot Plate at 20 °C for 30 min to homogenize and was later preserved at 20 °C until the films’ elaboration.

The TiO2 films occurred by placing a triplicate (2.000 ± 0.005) mL of each mixture in the ten precursor solutions (C solutions) and the Sigma-Aldrich commercial TiO2 solution (commercial control of TiO2), covering the whole substrate surface on the previously washed and hydrophilized mixture. The films were deposited through sedimentation and dried at (105 ± 3) °C for (16.00 ± 0.01) min in a SWISS MADE Precisa EM-120HR thermobalance. Subsequently, the annealing process involved four temperature ramps in a 119 V Terrigeno muffle; the first change in temperature was from 20 °C to 100 °C at 1.6 °C min−1 rate, then the temperature was kept constant for one hour to evaporate solvents and organic species from the film. After this time, the temperature set up was 450 °C; the increase was at a rate of 3.8 °C min−1, and finally, maintained at 450 °C for 1 h to induce the crystallization of TiO2 into the anatase phase []. At the end of the annealing and cooling steps, the films were removed from the muffle and preserved in 5 cm diameter Petri dishes to keep them dry.

3.3. Physical Characterization of TiO2 Film

3.3.1. Crystal Structure

For the characterization of the films prepared using the mixtures of the precursors (10 syntheses) and the Sigma-Aldrich TiO2 films, X-ray diffraction was performed with the Shimadzu X-Ray Diffractometer XRD-7000 equipment operating with a Cu copper anode (Kβ = 1. 54 Å), 0.3 mm divergence slit, and scanning from 20 to 60°, the voltage was 40.0 kV and 30.0 mA, which allowed the determination of the anatase crystalline phase of TiO2. In each treatment, the mean crystallite size was calculated using the Debye–Scherrer equation (Equation (3)), those treatments that had the anatase phase more intensively in plane (101) were clearly defined [].

where k = 0.94, the wavelength of the copper beam β = 1.54 Å, θ is Full Width Half Maximum (FWHM), and λ is the diffraction angle of the highest intensity in plane (101).

3.3.2. Optical Characterization

The absorption coefficient of the films deposited in the 10 synthesis protocols was analyzed to calculate the value of the forbidden band width of TiO2 from the absorption spectra and was estimated according to the Tauc model (Equation (4)) [,,] using a Varian Cary 300 Bio UV-Vis spectrophotometer, scanning from 300 nm to 600 nm with a tungsten lamp.

where α (cm−1) is the absorption coefficient of the films, hν (eV) is the photon energy, respectively, Eg (eV) is the bandgap energy between the conduction band and the valence band, values of n are 2 and 1/2 for allowed direct and indirect transitions, and A (a.u) is a constant that depends on the mass of the electron and hole.

3.3.3. Morphology

Finally, the surface morphology of the TiO2 films with higher intensity of the anatase crystalline phase was observed using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) at 30.0 kX magnification and 7.0 kV voltage []. Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDX) composition was used to detect the materials on the surface of the films [,]; additionally, stereoscope observations with 40× for the films obtained with synthesis 1 to 10 were performed.

3.4. Photocatalytic Activity of TiO2 Films

3.4.1. Strains Used in the Study

For the photocatalytic activity of the TiO2 films evaluation for the ten synthesis protocols in triplicate, the inactivation experiments employed E. coli 226 and S. Typhimurium 211 strains (obtained from the strain bank of the Food Microbiology laboratory of the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana). The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) was determined using the automated SensititreTM SWINTM Software (version SW1202), following the guidelines provided by the manufacturer. This procedure used broth microdilution plates (Thermo ScientificTM EUVSEC3), specifically designed for the susceptibility testing of Gram-negative bacteria; plate reading was conducted by using VisionTM Software (version 152-0007). The panel included 15 antibiotics: amikacin (AMK), ampicillin (AMP), azithromycin (AZ), cefotaxime (CTX), ceftazidime (CAZ), chloramphenicol (CHL), ciprofloxacin (CIP), colistin (COL), gentamicin (GEN), meropenem (Mer), nalidixic acid (NAL), sulfamethoxazole (SMX), tetracycline (TET), tigecycline (TGC), and trimethoprim (TMP) []. The resistance profiles previously investigated for each strain are E. coli 226 ampicillin (AMP), azithromycin (AZM), chloramphenicol (CHL), ciprofloxacin (CIP), teicoplanin (TEC), S. Typhimurium amikacin (AMK), ampicillin (AMP), chloramphenicol (CHL), gentamicin (GEN), and teicoplanin (TEC). For plates- and susceptibility-reading, the Vision™ equipment and the Sensititre™ SWIN™ Software System were, respectively, used [].

Some strains of Escherichia coli and Salmonella spp. may be antibiotic-resistant, sporadically found alone or together in domestic or agro-industrial wastewater.

Escherichia coli (biotype 1) is considered worldwide as an indicator of bacterium for fecal contamination, and for this reason, serves as a model in wastewater quality assays and to the efficiency of treatment and disinfection systems assessments [,,,,].

On the other hand, Salmonella Typhimurium is one of the bacteria responsible for causing salmonellosis in humans and can infect humans through the consumption of contaminated food or water []; this bacterium circulates in multiple vertebrate reservoirs, favoring its dissemination along production chains [], it is the dominant bacterial pathogen in wastewater []. In recent years, the monophasic variant (4, [5],12:i:-) has emerged, which has better adaptation characteristics to physical and chemical factors and is more resistant to antibiotics used against salmonellosis. In addition, several foodborne outbreaks have been responsible for a high hospitalization rate [,,], leading to the emergence of several new outbreaks of salmonellosis.

In this research Escherichia coli 226 and Salmonella Typhimurium 211 strains isolated from the pig industry and domestic wastewater were used. The Master Cell Bank (MCB) of these bacteria remain preserved in Nutritive Broth by freezing at −20 °C with 33% (w/v) glycerol [,]. Throughout the study, the primary strain bank was sampled to assess purity and viability as a function of time, to guarantee the quality of the bacteria in each of the photocatalytic inactivation assays. Vials of each bacterium were taken in triplicate and thawed at 19 °C. Subsequently, 1 mL of the suspension was transferred from each vial to a glass tube containing 9 mL of 0.1% (w/v) peptonized water. From this, further dilutions were made up to 10−8. From each dilution, 20 µL were surface seeded and the boxes were incubated for 24 h at 30 °C. Equation (5) was used to determine the CFU mL−1.

where CFU mL−1 are colony-forming units per milliliter. A: colonies counted in 20 µL of the seeded sample. B: correction factor equal to 50 to express the number of colonies in 1 mL. C: inverse of the dilution factor at which the count was performed.