Abstract

The proliferation of sophisticated malware poses a persistent threat to cybersecurity. While visualizing malware as images enables the use of Convolutional Neural Networks, standard architectures are often inefficient and struggle with the high spatial and channel redundancy inherent in these representations. To address this challenge, we propose LR-MalConv, a new detection framework centered on a novel Low-Redundancy Convolution (LR-Conv) module. The LR-Conv module is uniquely designed to synergistically reduce both spatial redundancy, via a gating and reconstruction mechanism, and channel redundancy, through an efficient split–transform–fuse strategy. By integrating LR-Conv into a ResNet backbone, our framework enhances discriminative feature extraction while significantly reducing computational overhead. Extensive experiments on the Malimg benchmark dataset show our method achieves an accuracy of 99.52%, outperforming existing methods. LR-MalConv establishes a new benchmark for visualized malware detection by striking a superior balance between accuracy and computational efficiency, demonstrating the significant potential of redundancy reduction in this domain.

1. Introduction

The proliferation and rapid evolution of malicious code—encompassing viruses, trojans, worms, and ransomware—present a significant and persistent threat to cybersecurity. The primary objectives of such software include data theft, creation of system backdoors, and infliction of widespread damage to computer systems [1,2]. With the advent of 5G, the Internet of Things (IoT), and cloud computing, the volume and velocity of malware have surged dramatically. According to the 2021 Ruixing Network Security Report, 119 million instances of malicious software were intercepted, marking a 23.71% increase from the previous year, highlighting the escalating nature of this threat.

Early malware detection primarily relied on signature-based methods [3], which involve matching byte patterns or rule-based heuristics (such as Yara rules [4]) against a database of known malware signatures. While simple and effective against known threats, this approach is easily circumvented by obfuscation techniques such as packing and polymorphism. Consequently, the research community shifted towards machine learning-based methods, leveraging static and dynamic features for detection. Static analysis extracts features like byte sequences, PE header information, opcodes, and entropy values without executing the code [5,6,7]. In contrast, dynamic analysis captures runtime behaviors like API calls [8] and system interactions [9] in a controlled environment, which requires executing the sample. Dynamic analysis via fuzz testing is highly effective for deep vulnerability discovery, with advanced methods like Vulseye targeting specific code paths [10]. However, this approach is computationally intensive and designed to find granular bugs, not to classify binaries holistically. Our static, image-based method acts as a crucial complement. It is engineered for high-throughput threat triage, identifying malware based on structural patterns without requiring execution. Thus, our approach enables rapid, large-scale classification, whereas fuzzing is best suited for in-depth, targeted application auditing. Although these methods improved detection rates for new malware variants, they often depend on complex and manually intensive feature engineering, requiring significant domain expertise.

A significant breakthrough came with the application of deep learning, particularly inspired by advancements in computer vision. Nataraj et al. [11] pioneered the approach of visualizing malware binaries as grayscale images, transforming the detection problem into an image classification task. This paradigm elegantly automates the feature extraction process, allowing Convolutional Neural Networks [12] to learn intricate textural and structural patterns indicative of specific malware families [13]. This code visualization technique has since become a prominent research direction, with various studies exploring its applications and enhancements [14,15].

However, standard deep learning models, while powerful, often introduce significant computational overhead and may not be optimally suited for the unique characteristics of visualized malware [16]. Unlike natural images, malware images frequently contain large areas of repetitive, low-information textures, leading to significant spatial redundancy in the learned feature maps. Concurrently, the high-dimensional feature spaces created by deep convolutional layers can suffer from channel redundancy, where multiple filters learn similar or correlated features. While various techniques have been proposed to address these issues individually, a holistic approach that synergistically tackles both within a single, efficient module remains an underexplored area. For instance, Senet [17], grouped convolutions [18] and depthwise separable convolutions [19] effectively reduce channel redundancy and computational cost but do not explicitly address spatial redundancy. Conversely, attention mechanisms [20] can re-weight features to emphasize salient spatial regions but do not fundamentally alter the convolutional structure to prevent the initial generation of redundant information. This research gap motivates our work.

To address this challenge, we propose LR-MalConv, a novel detection framework centered around a Low-Redundancy Convolution (LR-Conv) module. The core novelty of our work lies not in the invention of new atomic components, but in their synergistic integration to create a module that systematically reduces both spatial and channel redundancy. We hypothesize that this dual-reduction strategy is uniquely effective for visualized malware analysis, enabling the model to learn more discriminative features with greater parameter efficiency. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- (1)

- We propose a novel Low-Redundancy Convolution (LR-Conv) module, specifically designed to address the inherent data characteristics of visualized malware. This module is the first, to our knowledge, to synergistically reduce both spatial redundancy through a Group-Normalization-based gating and reconstruction mechanism, and channel redundancy via an efficient split–transform–fuse strategy. This dual-reduction approach allows for more discriminative feature learning with greater parameter efficiency.

- (2)

- We design and implement LR-MalConv, a new and efficient deep learning framework for malware detection. By seamlessly integrating the proposed LR-Conv module into a residual network backbone, the framework gains enhanced feature extraction capabilities while significantly reducing the parameter count and computational complexity compared to the standard ResNet architecture.

- (3)

- We conduct extensive experiments on the benchmark Malimg dataset and a newly constructed dataset. Our results demonstrate that LR-MalConv reaches an accuracy of 99.52% on Malimg.

2. Methods

This section introduces the details of the model, which is divided into two parts: (1). The structure of the model; (2) LR-Conv.

2.1. Model Structure

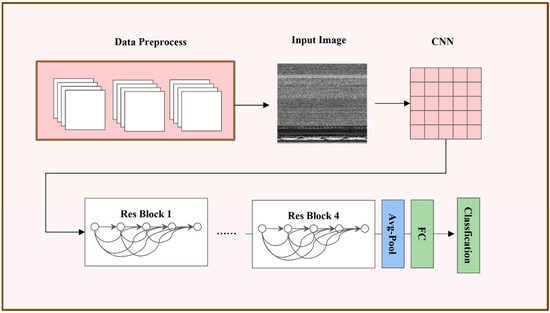

For the task of malicious code classification, we employ the ResNet [21] architecture as our foundational backbone. We augment this network by strategically integrating our proposed module to enhance its feature extraction capabilities. The complete methodological pipeline is illustrated in Figure 1. The process initiates by transforming raw malicious code binaries into 2D grayscale image representations, a technique that allows us to leverage powerful, well-established computer vision methodologies. These images subsequently undergo a standardized preprocessing pipeline, including normalization and resizing, to prepare them for network input. Finally, the resulting tensors are fed into the neural network, which is trained end-to-end to discriminate between malicious and benign samples, thereby yielding a highly effective classifier.

Figure 1.

The proposed malware detection framework.

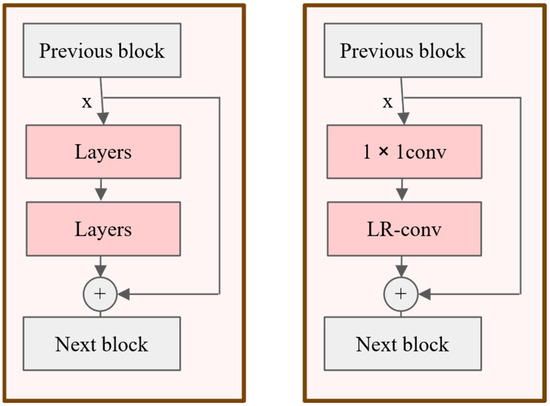

The foundational element of the ResNet architecture is the residual block, which facilitates gradient flow and enables the training of deeper networks through its characteristic identity shortcut connections (Figure 2, left). Our proposed module is engineered as a direct, drop-in replacement for the standard 3 × 3 convolutional layer within this block. To ensure seamless integration and preserve the dimensional integrity of the feature maps, a 1 × 1 convolution is appended to our module. This auxiliary convolution functions to align the channel dimensions, thereby allowing our module to be effectively embedded into the residual learning framework, as illustrated in the right panel of Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The left picture is the original Resblock; the right picture is how LR-Conv combines with Resblock.

2.2. Low-Redundancy Convolution

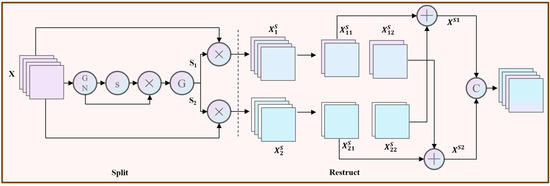

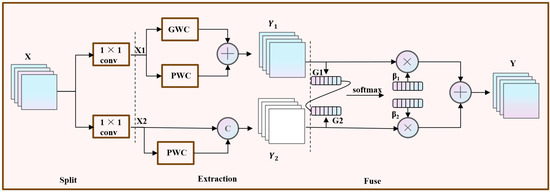

In conventional residual networks, feature maps generated by standard convolutions often contain significant spatial and channel-wise redundancies. Such redundancies can impede the model’s ability to learn abstract and discriminative semantics, particularly in complex tasks like malware classification. To address this, we propose the Low-Redundancy Convolution (LR-Conv) module, a novel architecture designed to enhance feature representation by systematically reducing redundancy. As depicted in Figure 3 and Figure 4, the LR-Conv module operates in two sequential stages: (1) Spatial Redundancy Reduction, and (2) Channel redundancy Reduction.

Figure 3.

The first part of LR-conv to decrease the spatial redundancy.

Figure 4.

The second part of LR-conv to decrease the channel redundancy.

2.2.1. Spatial Redundancy Reduction

The initial stage of our module mitigates spatial redundancy through a splitting and reconstruction mechanism. This process partitions feature maps based on their information content, which is estimated via the scaling factors (γ) in Group Normalization (GN) [22]. For a given input tensor X ∈ ℝN×C×H×W, where N, C, H, and W denote the batch size, channel count, height, and width, respectively, the GN output is formulated as:

Here, μ and σ represent the mean and standard deviation, ε is a small constant for numerical stability, and β and γ are trainable affine variables.

The trainable parameters γ in GN layers are used to measure the variance of pixels in each batch and channel. Our rationale is that feature channels critical for malware classification tend to exhibit higher variance, reflecting strong, selective activations in response to discriminative patterns. The trainable parameter γ rescales the normalized features. During training, the network learns to assign a larger γ to channels it deems important to amplify their signal and preserve their influence. Consequently, the learned magnitude of γ serves as a data-driven proxy for channel-wise feature importance, reflecting the model’s own assessment of saliency. More information will lead to a larger variance, thus producing a larger γ. The normalized correlation weight Sγ is calculated from Equation (2), which represents the importance of different feature maps.

When using sigmoid to map Sγ to [0, 1], a threshold is set as a gating unit, the weights above the threshold are set to 1 to get S1 and the weights above the threshold are set to 0 to get S2. In this mechanism, the threshold is a fixed hyperparameter that serves as a hard threshold. Based on empirical validation on our development set, the threshold was set to 0.5. This value provided the best balance between filtering out irrelevant features and preserving essential information. The calculation method for obtaining S is shown in Equation (3).

Subsequently, the input tensor X is element-wise-multiplied with S1 and S2 to yield two distinct feature sets: possesses rich spatial information while has little information, which is considered redundant. Based on this, we propose a reconstruction operation to combine these two features to generate a feature with more information and reduce spatial redundancy. The process is as follows:

where denotes element-wise multiplication, denotes element-wise addition, and represents concatenation. Compared with simple concatenation or addition, this split-attend-reconstruct mechanism promotes finer-grained information interaction between the two feature streams. It fosters intricate feature interplay, thereby capturing more complex dependencies and generating novel feature combinations absent in the original space. This forces the model to learn more robust representations and mitigates overfitting. Ultimately, these operations amplify salient features while suppressing redundancy, yielding a more informative feature map XS.

2.2.2. Channel Redundancy Reduction

Following the reduction in spatial redundancy, this stage addresses channel redundancy. The process involves three sequential steps: splitting, extraction, and fusion, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Splitting: The feature XS processed in the previous step is split into two parts at the channel level. To save computational resources, 1 × 1 convolution is used to reduce the dimension, reducing the number of channels calculated to half. As shown in Figure 4, it is divided into X1 and X2.

Extraction: Two efficient convolution operations (PWC and GWC) are used to replace the standard convolution to extract features from X1. The parameters and computation of GWC are much smaller than the standard convolution, but it loses the inter-group connection. PWC is used to compensate for this information. That is, perform k × k GWC operation (g = 2) and 1 × 1 PWC operation on X1, and then add the outputs element-wise to form the feature mapping Y1. This part of the operation is represented as:

where and represent the weight matrices generated in the two convolution operations, respectively. In this way, relying on the GWC and PWC of X1, rich information Y1 is extracted at a relatively low cost.

For X2, analogous to the cross-layer connection of the residual network, the original input is directly concatenated with the output processed by the 1 × 1 PWC operation to generate a supplementary feature Y2 that only has shallow hidden details. The calculation method is as follows:

Fusion: After the transformation, we do not directly connect or add the two types of features, but use the simplified SKNet method to adaptively merge the output features Y1 and Y2 from the upper and lower transformation stages, as shown in Figure 3. We first use global average pooling to collect global information and calculate Gm at the channel level:

Then, G1 and G2 are superimposed, and the channel soft attention (softmax) is used to calculate an importance vector β1 and β2 of a feature:

Finally, these two vectors are used to combine Y1 and Y2 to obtain the final result Y.

The LR-Conv module synergistically reduces spatial and channel redundancy. By integrating channel-wise feature pruning with a spatial gating mechanism, it functions as a lightweight yet powerful building block, extracting compact and discriminative features for the overall LR-MalConv architecture.

3. Experiments

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed method, in this section a series of experiments are conducted on two different datasets. Our model was implemented using the PyTorch 2.2.0 and trained on a single NVIDIA RTX 4060 GPU. The model was trained for 50 epochs using the Adam optimizer. Initial learning rate was set to 1 × 10−3, which was dynamically adjusted by a Cosine Annealing scheduler down to a minimum value of 1 × 10−5. Batch size = 64. We choose CrossEntropyLoss as loss function.

To ensure the robustness of our experiments while conserving computational resources, we employed a Multiple Random Splits strategy. Specifically, we repeated the data splitting process three times using different random seeds. For each split, the model was trained and tested independently. The final reported results are the average of these three repetitions.

3.1. Dataset Introduction

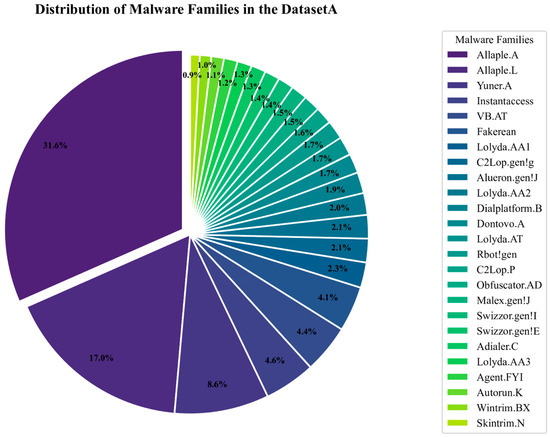

This work first conducts experiments and comparisons on dataset A, which is the Malimg [10]. Malimg contains 9339 malware from 25 different malware families. The distribution of different categories is shown in Figure 5. It can be seen that this data set is a relatively unbalanced dataset. In addition, the Malimg only contains malware.

Figure 5.

The distribution of different malware families in the Malimg.

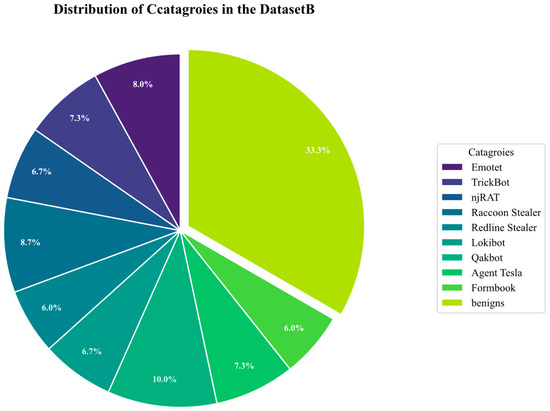

To evaluate the performance of our model on more contemporary malware samples, we constructed datasetB. Initially, we procured Portable Executable (PE) files corresponding to nine distinct malware families from the VirusShare [23] corpora spanning 2021–2023. The selection and classification of these malicious samples were guided by metadata from the VirusTotal API. Subsequently, a contrasting set of 5000 benign software samples was curated from reliable sources, including the native Windows operating system and popular third-party software repositories. To ensure dataset integrity and eliminate redundancy, all collected samples were deduplicated based on their respective hash values. The proportion of categories can be seen in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The proportion of two categories in dataset B.

3.2. Result

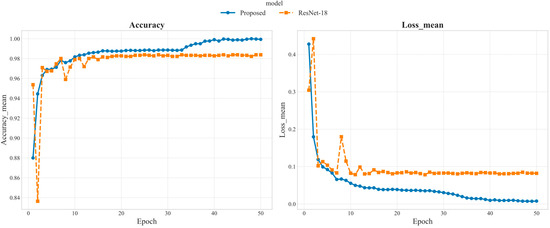

The superiority of our proposed method over the baseline is evidenced in Figure 7. Our approach not only achieves a significantly higher accuracy and lower loss but also converges faster, confirming its effectiveness in enhancing the base model.

Figure 7.

Train curve of proposed method and ResNet-18.

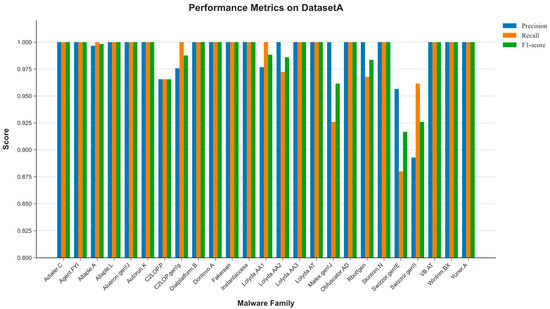

To address the challenge of class imbalance inherent in the Malimg dataset and to ensure our model’s performance is not skewed towards majority classes, we conducted a comprehensive per-class performance evaluation. Instead of relying solely on overall accuracy, we calculated the precision, recall, and F1-score for each of the 25 malware families. The detailed results are presented in Figure 8. The analysis reveals that our proposed model maintains robust performance across nearly all classes, including those with very few samples (minority classes). Problems only occur in categories with relatively few data samples: “Swizzor.gen!E” and “Swizzor.gen!I” both belong to the Swizzor.gen family, and hence there is a certain degree of similarity, leading to classification errors. If several categories belonging to the same large family are merged, the classification effect might be improved.

Figure 8.

Model performance on DatasetA.

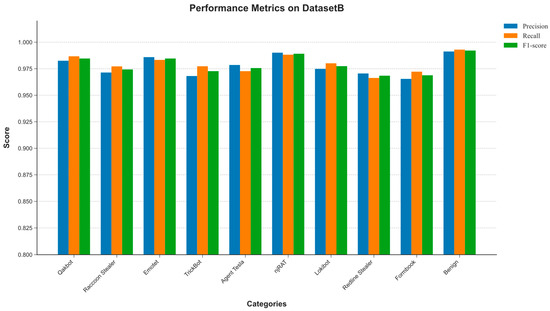

As can be seen in Figure 9, the model demonstrates robust performance when evaluated on Dataset B. This outcome is attributable to the well-balanced nature of this dataset, which results in more uniform performance metrics across all categories. The convergence of these per-class metrics indicates that the model is not biased towards any specific majority class within this balanced distribution.

Figure 9.

Model performance on DatasetB.

3.3. Experimental Evaluation

To validate the efficiency of our proposed LR-Conv module, as suggested by the reviewer, we benchmarked our complete LR-MalConv model against two leading lightweight CNN architectures—MobileNetV2 [24] and ShuffleNetV2 [25]—and the baseline of original ResNet-18. MobileNetV2 and ShuffleNetV2 represent the state-of-the-art in efficient network design and serve as a strong baseline for evaluating our contribution. We compared them across three critical dimensions: classification accuracy, the number of model parameters (a measure of size), and computational complexity (measured in GFLOPs). The results of this comprehensive benchmark are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of the efficiency and acc on two datasets.

The benchmarking results in Table 1 clearly illustrate the trade-offs. While MobileNetV2 and ShuffleNetV2 are better in terms of FLOPs and parameters, our work achieves significantly higher classification accuracy and the basic models do not perform well. Notably, LR-conv module greatly reduces the flops and parameter of the base model. This demonstrates that our proposed LR-Conv block strikes a superior balance between computational efficiency and discriminative power for the task of malware classification. It is not merely efficient in isolation, but achieves this efficiency while delivering state-of-the-art performance, a critical requirement for practical deployment.

To rigorously evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed framework, we conducted a comprehensive comparative analysis against several state-of-the-art methods on datasetA. A critical aspect of a fair comparison is ensuring that all models are evaluated under identical experimental conditions. Therefore, we re-implemented three key models: a standard deep learning architecture (ResNet-50), and two prominent methods from recent malware classification literature. These models were trained and tested using the exact same data splits, preprocessing steps, and evaluation metrics as our own model. For other established methods, we report the performance metrics as published in their original papers, acknowledging that minor variations in experimental setups might exist. The comparative results are summarized in Table 2; “Re” means Re-implemented and “Cited” means cited from the original paper.

Table 2.

Comparison of proposed framework with other papers on DatasetA.

The results in Table 2 clearly demonstrate the superiority of our proposed method. Our model achieves an accuracy of 99.52% and an F1-score of 98.80%, outperforming all re-implemented baselines. Notably, compared to the powerful ResNet-50 backbone, our model shows a significant improvement, which we attribute to the specialized feature extraction capabilities of the LR-Conv module. While direct comparison with methods cited from other papers should be interpreted with caution, our model’s performance remains highly competitive. This comprehensive and fair evaluation validates the effectiveness of our proposed architecture.

3.4. Ablation Study of the LR-Conv Module

To thoroughly investigate the individual contributions of the two main components within our proposed LR-Conv module—the Spatial Redundancy Reduction (SRR) mechanism and the Channel Redundancy Reduction (CRR) mechanism—we conducted a series of ablation experiments on the DatasetA. We constructed two variants of our model for this purpose: (1) Res_sr, which incorporates only the SRR module by replacing the CRR component with a standard convolution, and (2) Res_cr, which uses only the CRR module by bypassing the initial SRR stage.

The results of this study are summarized in Table 3. The baseline ResNet18 achieves an accuracy of 98%. By incorporating only the SRR module (Res_sr), the accuracy improves to 98.28%, demonstrating that our GN-based gating and reconstruction mechanism is effective at filtering out irrelevant spatial information and enhancing feature representation. When using only the CRR module (Res_cr), the model achieves an even higher accuracy of 99.25%, indicating that the split-extract-fuse strategy for reducing channel redundancy provides a substantial performance boost.

Table 3.

Ablation study of the LR-Conv components on datasetA.

Crucially, our full proposed model, which synergistically combines both modules, achieves the highest accuracy of 99.52%. This result is higher than the sum of the individual improvements, providing strong evidence that the two components are not just independently effective but also complementary. The SRR module first acts as a filter to create a more refined feature map, which then allows the CRR module to learn channel-wise representations more efficiently. This confirms the effectiveness of our integrated design.

4. Conclusions

In this work, we have introduced and validated LR-MalConv, a novel and efficient framework for visualized malware detection that directly addresses the critical challenge of feature redundancy. At the heart of our framework is the LR-Conv module, which effectively reduces both spatial and channel redundancy within a single, cohesive unit. Our extensive experiments demonstrate the superiority of this approach, with LR-MalConv achieving a state-of-the-art accuracy of 99.52% on the Malimg dataset. This result not only surpasses existing methods but also establishes a more favorable balance between accuracy and computational efficiency.

Ultimately, the success of our framework validates a key principle: designing specialized architectures that account for the unique data characteristics of a problem domain can yield significant performance gains over general-purpose models. This work underscores the value of targeted redundancy reduction as a potent strategy in cybersecurity applications. While our framework marks a significant step forward, we recognize that the ever-evolving threat landscape necessitates continuous validation and enhancement of its capabilities.

5. Limitation and Future Work

We acknowledge that a primary limitation of our study is the scope of the datasets used for evaluation. While we have taken steps to mitigate this by constructing a more recent dataset with a transparent methodology, we recognize that the malware landscape is continuously evolving. Therefore, future work should focus on validating our work on even larger and more diverse benchmark datasets, to further substantiate its generalizability to a wider array of modern threats. Also, a significant limitation of the current study is the evaluation of our model’s robustness against advanced evasion techniques. This represents a critical security concern. While our method demonstrates high accuracy, image-based classifiers are known to be vulnerable to inputs intentionally designed to cause misclassification. Attackers could employ two primary strategies: generating adversarial examples by applying subtle, often imperceptible, perturbations directly to the malware images or employing binary-level modifications—such as code mutation, obfuscation, or packing—which inherently alter the malware’s visual representation to evade detection. The challenge of creating robust defenses against such evolving, mutated, or polymorphic threats is a pressing issue at the forefront of cybersecurity research [31]. Inspired by these findings, a crucial direction for our future work will be to investigate and enhance the adversarial robustness of our framework. We plan to benchmark our model against various adversarial attack algorithms and, perhaps more importantly, evaluate its resilience to binary-level mutations that aim to change the resulting image structure. This includes exploring the integration of defense mechanisms to counter both types of evasion.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft: J.L.; Writing—review and editing: J.L., X.L.; Conceptualization: J.L., X.L., Y.R., J.C.; Investigation: J.L.; Methodology: J.L., X.L.; Supervision: X.L.; Project administration: X.L.; Validation: J.L.; Visualization: J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62402124), Open Project Program of Guangxi Key Laboratory of Digital Infrastructure (Grant No. GXDINBC202402 and No. GXDINBC202407), and Guangxi Science and Technology Base and Talent Project (Grant No. GuikeAD23026160), and Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 2025GXNSFBA069283).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, X.L., upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Conv | Convolution |

| LR | Low-Redundancy |

References

- Rieck, K.; Trinius, P.; Willems, C.; Holz, T. Automatic analysis of malware behavior using machine learning. J. Comput. Secur. 2011, 19, 639–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoroso, E. Recent progress in software security. IEEE Softw. 2018, 35, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, I.; Penya, Y.K.; Devesa, J.; Bringas, P.G. N-grams-based file signatures for malware detection. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, Milan, Italy, 6–10 May 2009; Volume 9, pp. 317–320. [Google Scholar]

- Van Impe, K. Signature-Based Detection with YARA. 2015. Available online: https://securityintelligence.com/signature-based-detection-with-yara/ (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Drew, J.; Moore, T.; Hahsler, M. Polymorphic malware detection using sequence classification methods. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Security and Privacy Workshops (SPW), San Jose, CA, USA, 22–26 May 2016; pp. 81–87. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, R.; Stokes, J.W.; Marinescu, M.; Selvaraj, K. Neural sequential malware detection with parameters. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2018—2018 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Calgary, AB, Canada, 15–20 April 2018; pp. 2656–2660. [Google Scholar]

- Ki, Y.; Kim, E.; Kim, H.K. A novel approach to detect malware based on API call sequence analysis. Int. J. Distrib. Sensor Netw. 2015, 11, 659101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Ji, L.; He, J. Analyzing malware by abstracting the frequent itemsets in API call sequences. In Proceedings of the 2013 12th IEEE International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications (TrustCom), Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 16–18 July 2013; pp. 265–270. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Qi, P.; Wang, W. Dynamic malware analysis with feature engineering and feature learning. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2020, 34, 1210–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, R.; Chen, J.; Wu, C.; He, K.; Wu, Y.; Cao, R.; Du, R.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, Y. VULSEYE: Detect Smart Contract Vulnerabilities via Stateful Directed Graybox Fuzzing. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.10116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nataraj, L.; Karthikeyan, S.; Jacob, G.; Manjunath, B.S. Malware images: Visualization and automatic classification. In Proceedings of the 8th International Symposium on Visualization for Cyber Security, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 20 July 2011; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lecun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-Based Learning Applied to Document Recognition. Proc. IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, B. Malware classification using gray-scale images and ensemble learning. In Proceedings of the 2016 3rd International Conference on Systems and Informatics (ICSAI), Shanghai, China, 19–21 November 2016; pp. 1018–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Vasan, D.; Alazab, M.; Wassan, S.; Safaei, B.; Zheng, Q. Image-Based malware classification using ensemble of CNN architectures (IMCEC). Comput. Secur. 2020, 92, 101748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, H.; Ullah, F.; Naeem, M.R.; Khalid, S.; Vasan, D.; Jabbar, S.; Saeed, S. Malware detection in industrial internet of things based on hybrid image visualization and deep learning model. Ad Hoc Netw. 2020, 105, 102154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Girshick, R.; Gupta, A.; He, K. Non-local Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7794–7803. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer vision and pattern recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 25; Pereira, F., Burges, C.J.C., Bottou, L., Weinberger, K.Q., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 1097–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Chollet, F. Xception: Deep Learning with Depthwise Separable Convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1251–1258. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30; Guyon, I., Luxburg, U.V., Bengio, S., Wallach, H., Fergus, R., Vishwanathan, S., Garnett, R., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; He, K. Group Normalization. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://virusshare.com/ (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.C. MobileNetV2: Inverted Residuals and Linear Bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 4510–4519. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, N.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, H.T.; Sun, J. ShuffleNet V2: Practical Guidelines for Efficient CNN Architecture Design. In Proceedings of the 15th European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 122–138. [Google Scholar]

- Makandar, A.; Patrot, A. Malware class recognition using image processing techniques. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Data Management, Analytics and Innovation (ICDMAI), Pune, India, 24–26 February 2017; pp. 76–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hemalatha, J.; Roseline, S.A.; Geetha, S.; Kadry, S.; Damaševičius, R. An efficient densenet-based deep learning model for malware detection. Entropy 2021, 23, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasan, D.; Alazab, M.; Wassan, S.; Naeem, H.; Safaei, B.; Zheng, Q. IMCFN: Image-based malware classification using fine-tuned convolutional neural network architecture. Comput. Netw. 2020, 171, 107138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Anisetti, M.; Ahmad, A.; Jeon, G. A Multilayer Deep Learning Approach for Malware Classification in 5G-Enabled IIoT. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 19, 1495–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, K.; Luo, S.; Varadharajan, V. A novel deep learning-based approach for malware detection. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 122, 106030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Chen, J.; Zhu, S.; Feng, W.; He, K.; Du, R.; Xiang, Y. WAFBooster: Automatic Boosting of WAF Security Against Mutated Malicious Payloads. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2025, 22, 1118–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).