Abstract

Villa Cicogna Mozzoni, located in Bisuschio near Varese and Lake Lugano, on the border between Lombardy and Switzerland, has origins dating back to the 1540s as a hunting lodge owned by the Mozzoni family. In the 16th century, significant renovations transformed it into a “villa di delizia”, adding gardens and elaborate decorative features to the interior and exterior, many of which are still preserved today. This article focuses on a precise geometric analysis of the building’s wooden ceilings, based on laser scanning and photogrammetric data surveying. The ongoing research particularly examines the wooden coffered ceilings on the first floor and the camorcanna wooden fake vault of the Grand Staircase of Honor. By analyzing the geometric data and comparing it with historical, archival, and recent manuals, the study has provided valuable morphological, construction, and conservation insights, forming the basis for the diagnostic and restoration project.

1. Introduction

The subject of this study [1] are the wooden ceilings from the third decade of the 16th century [2] inside the Renaissance Villa Cicogna Mozzoni in Bisuschio (Va). The aim of the research is to provide an exhaustive documentation of the geometric-constructive characteristics of these structures, highlighting all those geometric anomalies that may suggest any pathologies of degradation in progress or in the past and such as to require further diagnostic investigations.

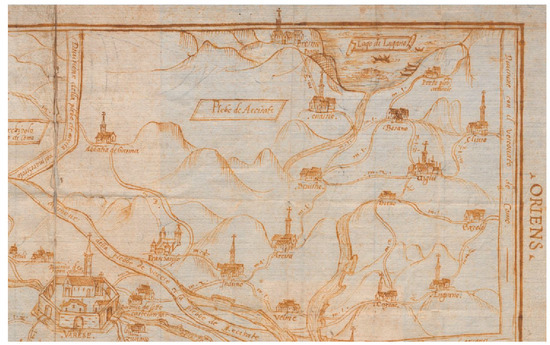

The historic residence, located in Lombardy on the Swiss border, was built by the Mozzoni family along the road from Varese to Lake Lugano, passing through Arcisate, and part of the Duchy of Milan. This road ran through the Valceresio and was in the past a convenient and direct transit route between the Alpine passes to the north and the plain to the south, passing through mountainous and wooded sub-Alpine territories to reach the lake and the Porto (harbour) di Arcisate (Figure 1). In the past, the timber trade, both for construction and firewood, also passed through this valley, which used the water basins to transport logs from the Sopraceneri valleys to the lowland areas and the cities, Varese, Como, and Milan; timber was transported along the waterways by flotation, while lighter assortments (firewood, charcoal, bark, processed wood) were transported on the same logs tied in rafts or on the numerous boats [3] that shuttled between the harbour of Arcisate and others on the other side of the lake, primarily that of Morcote. That timber was therefore available in the area at the time [4] and constituted one of the main materials in local construction [5].

Figure 1.

1573, Extract from the drawing of the Pieve di Varese (Archivio storico Diocesano di Milano, Visite Pastorali, serie X, vol. LXXXIV).

2. Historical Notes About the Villa’s Construction

Archival and bibliographical sources trace the existence of an original nucleus of the present Villa to the 1450s, configured as a hunting lodge, used by the Mozzoni family to hunt bears in the woods surrounding the building at the time [6].

Only in the first half of the 16th century, after a series of acquisitions of houses by the Mozzoni family, had the Casino been enlarged and transformed into a Villa di Delizie, surrounded by gardens on several levels and a large park. Therefore, the construction of the Villa dates back to the second or third decade of the 16th century because the archive documents (“Archivio storico Cicogna Mozzoni di Bisuschio”-ACMB) report in 1533 the existence of the Villa. The wooden ceilings covering the rooms on the first floor and the wooden vault of the Staircase of Honour were most probably built during this construction phase.

On the marriage between Ascanio Mozzoni and Cecilia Mozzoni in 1559, a series of improvements and restorations were made to the interior of the Villa, arranged on two floors above ground. In 1580, Angela Mozzoni married Giovanni Pietro Cicogna and another series of works were undertaken to embellish and complete the Villa (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Villa Cicogna Mozzoni in Bisuschio images (by author): (a) south front of the Villa from the garden; (b) west portico and the vault decorated with the coat of arms of the Mozzoni and Cicogna families; (c) the actual library at the first floor, used previously as Sala Bianca and private chapel; (d) the ”hall of mirrors” oh the ground floor; (e) the “fortepiano” room at the first floor.

From the end of the 16th century to the end of the 17th century, the internal distribution of the main rooms of the Villa remained more or less the same (Figure 3). From a functional point of view, the rooms on the ground floor of the central and west wings, considered the less noble part, were used as service rooms: there were kitchens, pantries, cellars, a dining room, a few rooms, and a large room for sheltering citrus fruits in the winter season. The first floor was destined for the residence: in the single east wing, known as the “women’s quarter”, there were rooms for noblewomen, in the double central wing, bedrooms and rooms for leisure, recreation, and games, while in the double west wing, a few rooms including the current library, also known as the Sala Bianca (“Stima dei lavori fatti al 1744” ACMB) and adapted as a private chapel in the first decade of the 18th century (“Note dè miglioramenti”, 1729, ACMB).

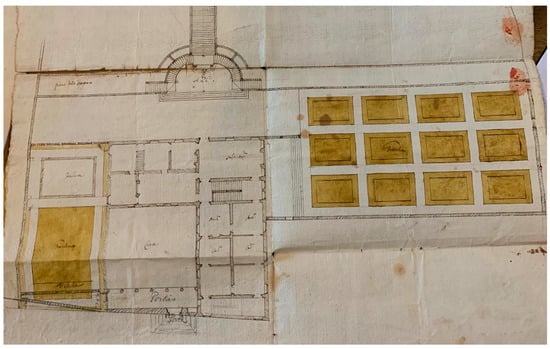

Figure 3.

About 1690, Plan of the Villa, partly representing the rooms on the ground floor and those on the first floor (ACMB).

Today, all the rooms on the ground floor are covered with masonry or wooden vaults, while the first floor is covered with wooden floors with different warping, including the Great Hall. Despite the improvements carried out on the Villa and its rooms on several occasions between the end of the 17th century and the first decades of the 18th century (of which the two inventories are kept at the ACMB and date back to 1744), mainly related to the opening and closing of windows and doors, the wooden roofs of the first noble floor have not been substantially altered over the centuries. The floor plan of the Villa drawn up in 1690 (Figure 3), which shows some rooms on the ground floor (e.g., entrance porch) and others on the first floor (central noble quarter) on the same level, corresponds to the current one.

It is Gianpaolo who mentions some renovation work on the “ceilings of some rooms” on the noble floor, commissioned in the early 18th century by Francesco II on some of the ceilings of the women’s quarter and the central body; however, according to the archive documents that have been found, these were mostly painter’s works, with the retouching of some decorations, without affecting the wooden structures that support them.

3. Materials and Methods: The Survey and Documentation of Wooden Structures for Their Knowledge

The 16th-century wooden ceilings of the Villa have not yet been studied from a constructional point of view and are an exceptional testimony to a local know-how that has in many ways been forgotten today. The fact that they have not been restored or modified over the centuries, except for limited and inevitable repair work, makes them valuable documents to be studied and preserved through the design of punctual interventions that adhere to the real needs of the existing structures, which are different one from the other, despite their apparent similarity. For this reason, it was necessary to start with an accurate geometric digital survey of these structures [7] to investigate the different construction techniques used in the various rooms and to analyze their state of preservation.

The study of the 16th-century roofing structures of the interior rooms, vaults, and ceilings was part of a larger campaign of surveys of the Villa, conducted between 2021 and 2023, using different integrated methods and instruments. Firstly, an accurate and complete laser scanning survey of the entire Villa was conducted in May 2021, carrying out 59 scans with the Faro Focus Cam instrument (georeferencing accuracy of scans ± 1 cm); in 2022, this survey was supplemented by that of the ancient greenhouses, built from the 18th century onwards in the portion of the garden to the south of the Villa [8]. 3D photogrammetry was used to create the orthophotos of the external fronts of the Villa on a scale of 1:50 (ground pixel size ≤ 1 cm); in particular, the photographic images were acquired with a Nikon DX camera with 12-bit resolution and processed with Agisoft Photoscan Pro 2.1.0 software. The direct survey was used as a fundamental tool to integrate all those measurements not taken by the laser scanner and to represent with a greater level of detail some specific construction elements. All the measurements taken were georeferenced in a single reference system to obtain a unique three-dimensional data model, the points cloud from which two-dimensional, 1:50 scale drawings were extracted using Autodesk Autocad 2020.

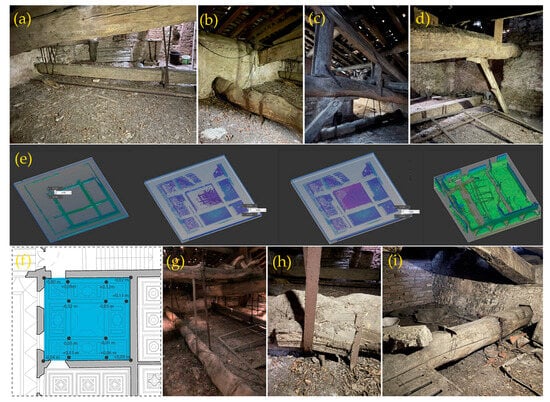

With specific regard to the surveying and documentation of the wooden ceilings, some routine maintenance work carried out in March 2023 on the wooden lacunar coffered ceiling of the Great Hall made it possible to deepen some information on the stratigraphy of the ceiling itself, thanks to the possibility of inspecting its interior.

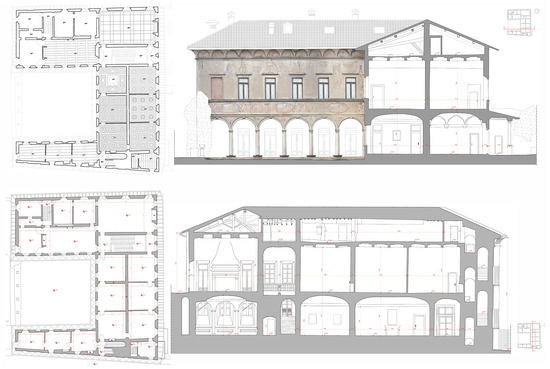

The first step of the data elaboration was the creation of two-dimensional drawings (Figure 4 and Figure 5). Secondly, the data gathered and presented graphically were used to investigate and analyze the precise geometry of the structures, masonry, and horizontal systems to assess their condition. Specifically, concerning both the wooden floors and the vaulted ceilings, construction hypotheses were made for various components and their assembly, based on the multiple vertical sections extracted from the laser scanner points cloud. These construction observations were formed by comparing them with known contemporary buildings and referencing historical manuals. The inspection of one of the floors finally made it possible to validate some of the previously formulated construction hypotheses. In this way, it became possible to identify the most vulnerable and delicate structures, which will be the focus of future diagnostic investigations on their preservation status, providing essential geometric and constructive insights for planning restoration or reinforcement actions on the buildings. In particular, the precise measurements regarding the inter-floor thicknesses, the connections between the horizontal systems and the perimeter walls—both external and internal—along with the existing deformations, were incorporated into the system along with the crack patterns. The systematization of all these geometric, formal, morphological, and qualitative data enabled the formulation of hypotheses regarding the ongoing degradation phenomena, which can be assessed for their potential risk by examining the physical deformations of the individual structures.

Figure 4.

From laser scanner points clouds (images on the top) and photogrammetric data to 2D drawings in scale 1:50: in the middle, fronts of the main entrance and, below, south façade (drawings by Anna Urso).

Figure 5.

On the left, plans show the projection of the wooden floors of the rooms on the main floor of the Villa and the dimensions of the rooms; on the right, cross and longitudinal sections on the main body of the Villa.

As far as the ceilings of the rooms inside the Villa on the first floor are concerned, these are in all cases wooden ceilings or vaults in incannicciato (fake vault); in particular, the women’s quarter and the Library have double warp wooden ceilings a regolo per convento (monastery rule) and the rooms on the main floor of the main building and the Hall of Honour have wooden ceilings a cassettoni (coffered) or “lacunars”, and a light incannicciato staircase vault.

As previously noted, the simultaneous construction of the wooden coffered ceilings and the vaulting dates back to an early phase of the Villa’s construction, before 1560.

4. Results

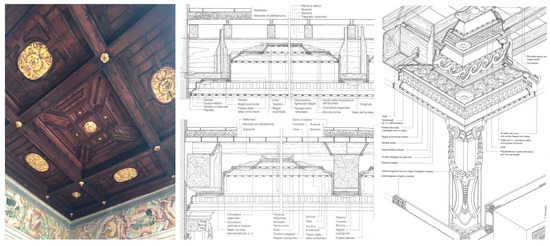

4.1. The Lacunar Coffered Wooden Ceilings of the Central Body of the Main Floor

Lacunar ceilings were first introduced in Italian architecture during the 15th century, gaining widespread use in the subsequent century. As Conforti [9] observes, this construction method became prominent during the Renaissance, spurred by the growing fascination with classical antiquity and perspective development [10]. Inspired by the marble models of ancient architecture, the lacunar’s regular geometric patterns, mostly square, were carved to varying depths based on the thickness between the intrados and extrados. This technique created a sense of spatial perspective in the room, thanks to a precise geometric arrangement. The square modules could be further enhanced with decorative elements such as molded cornices, astragals, rosettes, darts, dentils, pinecones, and pendants of various types [11]. Additionally, gilding and painting were often applied to enhance the effect and amplify or soften the perspective illusions.

The structural framework of the wooden ceilings could be either single or double. When no rooms were above the extrados, as seen in Villa Cicogna Mozzoni, the wooden deck supporting the lacunars, which rested directly on the main beams, could be suspended from the roof beams or trusses [12]. For this reason, some architectural scholars refer to them as “apparent ceilings”.

The wooden ceilings from the 16th century, which cover the rooms on the first floor of the main section of the Villa, are all lacunar ceilings, distinguished by square and rectangular sections that form a regular, modular geometric pattern. Six square attics cover the rooms of the two-part building, each measure approximately 6 × 6 m. Apart from the corner room, referred to as the “Game room”, all the ceilings are divided into nine square modules, each about 2 × 2 m, creating a highly organized and symmetrical design. The distinctiveness of the attic in the game room is further highlighted by the varying thickness of the surrounding walls, which are about 50 cm thick, while the walls in other areas are considerably thinner, around 15 cm. It is also notable that the perimeter walls of these rooms are the only ones in the central section of the Villa that maintain the same alignment across all levels, from the ground floor to the ceiling. These geometric features, along with a series of mensiochronological studies conducted on the walls of the attics and the sealed openings still present, suggest that these walls likely date back to the 15th-century hunting lodge.

From a design perspective, although there are some variations from floor to floor, the geometries of the ceiling panels are relatively simple, primarily featuring alternating regular shapes such as squares, circles, triangles, and octagons. At the centre of each panel, as well as at the intersections of the beams dividing the panels, there is a gilded floral motif.

The analysis of the floor sections has made it possible to make a construction hypothesis regarding the parts that are not visible and to make a series of useful considerations to assess their state of conservation and to set up a future restoration and structural consolidation intervention. In fact, by comparing the outline of the intrados and extrados of all the floors, except the one in the game room (approximately 60 cm from beam intrados to co-opening floor [13]), which are geometrically very similar to each other, with the sections of similar and contemporary floors (Figure 6)), the following double-original package was assumed: main beams, with spacing between them of approx. 2 m and arranged parallel to the perimeter walls, section approx. 20 × 30 cm, 7 × 7 cm joists, presumably every 50 cm [14], with a roof covering of approx. 2 cm.

Figure 6.

Geometrical and constructive analysis of the coffered ceiling of the “game room”: (e) laser scanner points cloud analysis; (a–d) images (by author) of the extrados of the ceiling; (f) schema of the punctual deformation’s measurements on the wooden ceiling; (g–i) the system of hanging elements to the roof.

A section taken from the game room revealed a significant ceiling (Figure 7) sag of approximately 10 cm across a span of about 6 m, located in the two rows of mirrors facing the outer front of the Villa, overlooking the inner courtyard. This ceiling is characterized by square mirrors in the room’s corners. Inspection of the extrados of the ceiling—unique in that it lacks a screed on the outer surface of the planking (which is only 2 cm thick and notably flexible)—revealed the presence of two additional beams, likely intended as reinforcement. Visible breakage signs are evident in these beams where they meet the perimeter walls. These beams align with two transverse “false beams” (Figure 7), constructed to form the square configuration of the coffer. Metal stirrups are visible on these beams, extending into the floor’s thickness, seemingly designed to help support the ‘false beams,’ which are made of wooden linings [15,16]. The sagging of this ceiling appears to have occurred previously, though further investigation of archival records will likely be required to determine the exact date of this reinforcement work.

Figure 7.

On the left, is a picture of the coffered wooden ceiling of the “Fortepiano room”. On the left, are drawings of a similar coffered ceiling published in a manual [13].

The decoration of the walls in the six rooms with coffered ceilings is organized into regular geometric fields, topped with a frescoed cornice that runs along the ceiling impost, reflecting a geometric pattern for regular modules, similar to the ceiling design [17]. The heights of the mirrored modules are consistently the same except in the recreation room, where the varying height of the intrados of the central rectangular module adds movement and perspective to the ceiling, with bands sloping towards the centre to create a “broken” lacunar, bordered by “defleshed” frames inspired by traditional mouldings decorated with antique motifs. In the 15th century, skilled carvers began employing perspective techniques to realistically simulate the three-dimensional appearance of spaces and objects [18]. This perspective illusion seen in the ceilings is reflected in the frescoes on the wall panels, which portray damask draperies, creating a sense of movement that is not present.

4.2. The Wooden ‘Monastery Rule’ Floors of the Women’s Quarter

The wooden floors covering the three rooms for the women of the noble family (Figure 8) are double beamed, with main beams covered with linings and arranged transversally concerning the perimeter walls, and joists, bushes, and convent rulers covering the spaces between the individual planks of the floorboard [19]. All the intrados surfaces of the floors are decorated to form a regular geometric pattern of square coffers, with the inclusion of gilded elements to embellish the final effect.

Figure 8.

The wooden ceilings cover the three rooms on the first floor of the Women’s Quarter (by author).

These rooms are similar in volume but with a variable floor plan to adapt to the two different directions of the wall towards the internal courtyard and the street. The first room of access to the flat, from the central cover of the Villa, the largest, has a floor of approximately 4.6 × 5.7 m, with a single main beam arranged in the middle, 21 × 41 cm thick and 7 × 11 cm joists arranged with a centre-to-centre distance of approximately 2.8 metres and planking of approximately 37 cm wide.

From a geometric point of view, the main beam does not show any deflection, while some floor deformations were found at the centre of the two bays delineated between the walls and the main beam, with a maximum deflection of 6.5 cm.

Only in correspondence with the last room towards the garden do the partitions of the upper floor rest on the false floor, without, however, causing significant deformations of the wooden ceiling. The main beams of the three rooms discharge onto the wall between the openings and fall at the columns on the lower floor, where there is the entrance loggia.

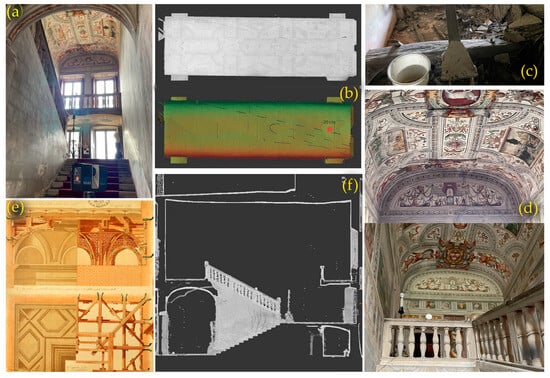

4.3. The Wooden Vault of the Staircase

The barrel vault covering the Grand Staircase was probably built during the 1560s in place of pre-existing walls belonging to the Hunting Lodge.

The lowered wooden barrel vault ceiling is fully frescoed and displays a noticeable pattern of cracks. In keeping with the local construction methods of the period [20], the vault is made of wooden ribs shaped like a barrel vault, connected by continuous wooden elements, a layer of “incannicciato”, and the final layers of plaster. Although it is currently impossible to perform core drilling to evaluate the structural integrity and the level of plaster detachment from the underlying support, a series of geometric observations on the actual shape of the vault allowed for the identification of potential risks related to ongoing degradation, which could result in the loss of valuable 16th-century artwork. The survey also uncovered five flat metal chains embedded in the thickness of the vault’s plaster, spaced regularly at 2.5 − m intervals. At certain points, gaps in the plaster were observed in alignment with these more rigid elements, likely caused by the movement of the wooden structure, which is naturally more flexible (Figure 9). A three-dimensional model derived from the laser scanner point cloud revealed several deformations, the locations of which must be analyzed alongside the shape, position, and size of the cracks (with a maximum deformation of 20 cm). A comparative analysis of the crack pattern and vault deformation showed an irregular pattern of past and ongoing movement and settling. Identifying the positions of these geometric deformations [21] and the direction of movement may help in determining where to install monitoring systems. Similarly, diagnostic investigations and surveys should be conducted on the paint layer to assess its condition and any potential detachment.

Figure 9.

Geometrical and constructive analysis of the camorcanna—fake barrel vault of the main staircase. (a) The Grand Staircase; (b) two different coloured views of the vault’s laser scanner points cloud with the indication of the maximum deformation registered; (c) an image of the wooden beam at the extrados of the vault with the iron hanging element; (d) the painted vault; (e) a table of a historical treatise [20]; (f) a vertical longitudinal section of the points cloud with the deformation of the vault’s geometry.

5. Conclusions

Although it deals with local construction techniques, widespread in Italy since the 16th century and widely used in Lombard palaces, this research proposes a rigorous method of analyzing and interpreting geometric data for an initial diagnostic assessment of the structures, to be further investigated and compared with information of a different nature. The opportunity, for the first time, to conduct an accurate survey of the Villa using laser scanning and photogrammetric tools enabled the collection of exact measurements related to the individual structural wooden elements, whose shapes often appear complex and irregular. These geometric observations allow for the identification of the most sensitive areas and structures, guiding the future diagnostic [22], preservation, and reinforcement plan [23]. These data, alongside observations on the materials and their condition, provided essential insights into the building’s construction history, past design decisions, and the changes that have occurred over the centuries to various structural components. This information was then cross-referenced with historical and archival records and with research on similar and contemporary buildings, although not very numerous. From this integration of data, valuable insights emerged to inform the conservation strategy for these structures through an iterative approach involving data analysis, hypothesis formation, comparison with archival information, and then revisiting the object to validate or adjust the construction theories.

Of the wooden floors analyzed, both in the central body and the women’s wing, only one floor was identified, that of the “game room”, in which the alteration of the geometries provides an alert concerning their state of preservation, to be further investigated with inspections from the extrados and diagnostic tests on the timbers to assess the anchoring systems between the parts. Similarly, the vault of the staircase, which shows a worrying deformation at the window, is an area also affected in the recent past by infiltration of rainwater from the roof plane. The presence of water is also a factor to be taken into great consideration when assessing the last wooden ceiling of the women’s wing, where traces of humidity are visible on the painted surfaces; in this case, no geometric anomalies have been recorded, but the state of conservation in which the wood is found requires careful assessment and monitoring of the situation, to be carried out with other diagnostic tools.

The future restoration approach, inherently, must be tailored to each element and its conservation state, ruling out solutions that are predefined. This methodology is the only way to ensure a successful conservation project, one that effectively preserves the existing structures while respectfully guiding them into the future. In this context, three-dimensional drawing and modelling are not only crucial tools for representing the existing but also key instruments for knowledge and genuine diagnostic examination.

Funding

This research work is part of a Research Agreement (scientific responsible prof. Daniela Oreni) between the Politecnico di Milano, ABC Department, and the Fondazione Cicogna Mozzoni onlus (n. 7513/2022).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy restrictions (data private property).

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the Cicogna Mozzoni family and in particular Count Jacopo Cicogna Mozzoni, for sharing the private archival materials and for the great availability shown. Many thanks to architect Anna Urso for the graphic drawings.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Oreni, D. Drawing and Geometrical Interpretation of Historical Constructive Elements for Conservation Activities: The Sixteenth Century Coffered Wooden Ceilings and the “camorcanna” Vaults of the Villa Cicogna Mozzoni. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications (ICCSA 2024), Hanoi, Vietnam, 1–4 July 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogni, M. Villa Cicogna Mozzoni. Guida; Officina Libraria: Milano, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bertogliati, M. Il commercio del legname dalle montagne alle pianure: Il caso del Cantone Ticino nell’Ottocento. Percorsi Di Ric. 2011, 3, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bonan, G. Pionieri Nella Frontiera Del Legname? I Commercianti Di Legname in Italia Settentrionale Durante l’Industrializzazione. Imprese E Stor. 2022, 46, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampaolo, L. Il Palazzo Cicogna Di Bisuschio (Nuovi Documenti). Archeol. Dell’antica Prov. E Diocesi Di Como 1947, 48, 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Urso, A. Villa Cicogna Mozzoni: Studi ed Analisi per la Conoscenza, e la Conservazione e per una Proposta Compatibile di Riuso e Valorizzazione di una Villa Rinascimentale Lombarda 2021; Relatore Matracchi, P., Co-relatori Oreni, D., Della Torre, S., Eds.; Tesi di Specializzazione in Beni Architettonici e del Paesaggio, Università degli Studi di Firenze: Firenze, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Augelli, F. The Diagnosis of Wooden Works and Structures. The Surveys; Il Prato: Villatora, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic, D.; Oreni, D. Drawings for the Reuse of Nineteenth Century Greenhouses in the Garden of Villa Cicogna Mozzoni. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, 48, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conforti, C.; Belli, G.; D’Amelio, M.G.; Funis, F. Opus Incertum. Soffitti lignei a lacunari a Firenze e a Roma in età moderna. In Rivista di Storia dell’Architettura Università Degli Studi di Firenze; Officine Grafiche Giannini: Napoli, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Opus incertum: Nuova Serie; III, University Press: Firenze, Italy, 2017.

- Grimoldi, A.; Landi, A.G. History and analysis of coffered ceilings: The case study of Palazzo Raimondi in Cremona. In Structural Health Assessment of Timber Structures; DWE: Wroclaw, Poland, 2015; pp. 236–247. [Google Scholar]

- Tosini, A. Coffered ceilings in the churches of Rome, from the 15th to the 20th century. TEMAm 2022, 1, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tampone, G.; Mannucci, M.; Macchioni, N. Strutture di Legno. Cultura, Conservazione, Restauro; De Lettera Editore: Milano, Italy, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Belardi, P.; Ramaccini, G. “Con una disinvoltura davvero fantastica”. Sul soffitto cassettonato dello studiolo di Gubbio. Opus Incert. 2018, 3, 144–147. [Google Scholar]

- Rondelet, J.B. Trattato Teorico e Pratico dell’arte di Edificare. First French Edition 1802–1817; Italian Edition 1833, A Spese Della Società Editrice, coi tipi di L. Caranenti: Mantova). Available online: https://rome.library.nd.edu/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=1856 (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- Valadier, G. L’architettura Pratica; Società Tipografica: Roma, Italy, 1828. [Google Scholar]

- Serlio, S. I Sette Libri Dell’Architettura; Presso Francesco de’ Franceschi Senese: Venezia, Italy, 1537. [Google Scholar]

- Giovannetti, F. Manuale del Recupero del Comune di Roma; Tipografia Del genio civile: Roma, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Grimoldi, A.; Landi, A.G.; Facchi, E. Re-employed, transformed or preserved. The wooden beam floors in Palazzo Magio Grasselli in Cremona. In SHATIS’ 19-5th International Conference on Structural Health Assessment of Timber Structures; Universidade do Minho: Braga, Portuguesa, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Formenti, C. La Pratica del Fabbricare-Parte Prima: Il Rustico Delle Fabbriche; U. Hoepli: Milano, Italy, 1909. [Google Scholar]

- Brumana, R.; Oreni, D.; Raimondi, A.; Georgopoulos, A.; Bregianni, A. From survey to HBIM for documentation, dissemination and management of built heritage: The case study of St. Maria in Scaria d’Intelvi. In 2013 Digital Heritage International Congress (DigitalHeritage); IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Volume 1, pp. 497–504. [Google Scholar]

- Augelli, F.; Bordina, A.; Migliavacca, J. Diagnosis for the Conservation of Wooden Ceilings inside the Ducal Palace in Sabbioneta (Mantua, Italy). Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 778, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Chiesa di San Giuseppe dei Falegnami a Roma. Il cassettonato ligneo: Restauro e ricostruzione. Recuper. E Conserv. Mag. 2019, 156.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).