Abstract

AI-generated phishing emails present a growing cybersecurity threat, exploiting human psychology with high-quality, context-aware language. This paper introduces a novel two-stage detection framework that combines deep learning with psychological analysis to address this challenge. A new dataset containing 2995 GPT-o1-generated phishing emails, each labelled with Cialdini’s six persuasion principles, is created across five organisational sectors—forming one of the largest and most behaviourally annotated corpora in the field. The first stage employs a fine-tuned DistilBERT model to predict the presence of persuasion principles in each email. These confidence scores then feed into a lightweight dense neural network at the second stage for final binary classification. This interpretable design balances performance with insight into attacker strategies. The full system achieves 94% accuracy and 98% AUC, outperforming comparable methods while offering a clearer explanation of model decisions. Analysis shows that principles like authority, scarcity, and social proof are highly indicative of phishing, while reciprocation and likeability occur more often in legitimate emails. This research contributes an interpretable, psychology-informed framework for phishing detection, alongside a unique dataset for future study. Results demonstrate the value of behavioural cues in identifying sophisticated phishing attacks and suggest broader applications in detecting malicious AI-generated content.

1. Introduction

The rapid proliferation of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies in recent years has redefined human–computer interaction (HCI) and helped achieve previously unattainable levels of data analysis, automation, and decision-making capabilities. Despite reshaping job markets and offering significant societal benefits, they have inadvertently enabled threat actors to create increasingly sophisticated offensive security threats. Of particular concern is the application of AI to generate highly convincing and seemingly genuine phishing emails almost instantaneously.

Large language models (LLMs) are trained using unsupervised learning techniques on enormous corpora of human-written text and further exacerbate the shifting threat landscape. These models demonstrate remarkable competence in contextually understanding and generating text, enabling the mass production of linguistically sophisticated and contextually aware malicious communications.

Since the introduction of webmail and email clients in the 1990s, emails have been the ubiquitous standard for individual, enterprise, and government communications and thus remain a prominent attack vector to facilitate cybercrime, including data theft, corporate espionage, and credential harvesting. This commonality, combined with the inherent trust users associate with emails, exposes a medium for adversaries to deceive victims.

Recent statistics underscore the prominence of this threat, with phishing emails accounting for 65% of all phishing-related attacks [] and contributing to one-third (36%) of organisational data breaches []. The financial implications are equally significant, with the global average cost of a data breach increasing by 10% to USD 4.8 million in 2024 [].

The pervasive nature of phishing emails highlights their effectiveness and can broadly be attributed to their deeply embedded application of persuasion principles derived from social psychology. Authority, social proof, likeability, reciprocation, consistency, and scarcity serve as cognitive shortcuts that influence the processes of human decision-making []. The post-pandemic shift to remote working, where 26% of UK workers are hybrid working in 2024, in contrast to 4.7% in 2019 [], foreshadows the growing concerns and relevance of AI-generated phishing emails as traditional organisational security boundaries continue to diminish.

Traditional barriers that previously limited the development of effective phishing campaigns, such as linguistic fluency, contextual relevance, and esoteric knowledge of specific domains, are no longer significant, as these models can generate grammatically correct and nuanced phishing emails featuring industry-specific technical jargon at scale. Consequently, this capability enables even unskilled adversaries to employ advanced social engineering techniques with minimal effort.

This research aims to address the significant gap in AI-generated phishing email detection by presenting a novel approach focused on persuasion-principle analysis. With few existing benchmarks in this area, this study develops a two-stage deep learning framework for semantic analysis and persuasion-principle identification.

The main contributions of this paper are summarised as follows:

- Review the state-of-the-art applications and research on AI/ML for detecting phishing emails.

- Design an AI/DL model capable of detecting AI-generated phishing emails.

- Test a dataset of AI-generated phishing emails.

- Recommend improvements for the effectiveness of the AI/DL model for phishing email detection.

The motivation for this research stems from the need for more sophisticated defensive capabilities against increasingly convincing AI-generated phishing emails. Creating a purpose-built dataset that systematically incorporates the persuasion principles established in social engineering provides insight into how threat actors exploit psychological biases and how these biases may manifest in evolving AI-driven attacks. Moreover, the deep learning models illustrate that semantic analysis can detect these manipulative strategies, offering a detection approach based on subtle psychological cues rather than purely technical indicators.

The rest of this paper is organised as follows. Section 2 outlines the evolution of phishing detection techniques, psychological persuasion principles, and the rise of AI-generated phishing, and identifies current gaps, proposing future research integrating semantic and psychological analysis. Section 3 provides an account of the system’s development, from dataset construction and model architecture to training configuration and implementation. It also outlines the evaluation methodology used to assess performance, interpretability, and reliability, supported by statistical and linguistic analysis. Section 4 presents the end-to-end design and implementation of the AI-driven phishing email detection system, including dataset creation, model architecture, training configuration, and technical constraints. It also details the evaluation methodology used to assess model performance, interpretability, and reliability through both quantitative metrics and in-depth analysis techniques.

2. Review

This section reviews the development of phishing detection methodologies, with a particular focus on the evolution from heuristic-based systems to contemporary AI-enabled approaches. The discussion is framed around four key areas: traditional and machine learning techniques in phishing detection, the incorporation of deep learning and interpretability, the role of psychological persuasion principles, and the recent emergence of AI-generated phishing threats. The review culminates in the identification of current research gaps and situates the contribution of this study within a broader cybersecurity landscape.

2.1. From Heuristics to Machine Learning

Phishing detection initially relied on rule-based heuristics such as blacklisting URLs, checking email headers for anomalies, and examining domain metadata. These approaches were effective against early forms of phishing, which often included misspellings, malformed links, or suspicious attachments. However, as attackers adopted more sophisticated strategies—including social engineering, contextual tailoring, and better grammar—these static methods became less effective.

To overcome this, machine learning (ML) approaches were introduced, enabling detection systems to identify new phishing instances based on learned patterns. Early ML-based approaches employed classifiers such as Support Vector Machines (SVMs), Naive Bayes, and Decision Trees trained on handcrafted features. PILFER, one of the earliest phishing detection frameworks, analysed lexical and host-based attributes such as domain age and IP reputation. It achieved over 96% accuracy while maintaining a very low false-positive rate []. However, such systems primarily relied on surface-level features and overlooked the manipulative linguistic structures present in phishing emails [].

2.2. Advances in Content-Based Detection

As phishing tactics evolved, so did the need for more nuanced analysis of email content. Researchers turned to content-based detection methods that employed bag-of-words models, term frequency–inverse document frequency (TF-IDF), and syntactic parsing to analyse the linguistic structure of phishing messages. These methods enabled the capture of higher-level semantic features rather than relying solely on metadata.

Studies such as that by Ma et al. [] demonstrated that models incorporating both content and context significantly outperformed those based solely on header features. Similarly, Metsis et al. [] showed that hybrid approaches combining structural and linguistic features provided improved generalisability across datasets. Stylometric analysis—such as sentence complexity, grammatical consistency, and part-of-speech patterns—emerged as a useful tool in distinguishing phishing from legitimate messages. Research revealed that phishing emails often exhibit particular stylistic features such as imperative language, inconsistent syntax, and excessive punctuation [].

Yasin and Abuhasan [] achieved 99.1% accuracy using Random Forest classifiers with features drawn from the Nazario corpus, reinforcing the predictive power of linguistic attributes. These developments laid the foundation for the integration of Natural Language Processing (NLP) into phishing detection pipelines.

2.3. Deep Learning and Explainability

While traditional ML approaches improved detection rates, they struggled with zero-day phishing attacks that lacked historical data. Deep learning (DL) models addressed this limitation by automatically extracting hierarchical and abstract representations from raw text. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) architectures allowed models to capture contextual dependencies and complex syntax in ways that manual feature engineering could not.

LSTM networks paired with word embeddings such as Word2Vec or GloVe enhanced contextual understanding by capturing semantic relationships between words. For instance, phrases like “confirm your password” and “verify your identity” carry similar intent but differ in wording; embeddings help models generalise across such variations []. Mahdavifar and Ghorbani [] found that DL models consistently outperformed classical ML approaches across multiple cybersecurity tasks, including phishing detection.

Despite their superior performance, DL models often function as black boxes, limiting transparency in decision-making. This poses challenges in regulated sectors like healthcare or finance, where interpretability is essential for compliance and trust. A flagged message needs to be explainable, especially when blocking it could disrupt operations or customer relationships.

To bridge this gap, Explainable AI (XAI) methods have been introduced. Techniques such as attention mechanisms, saliency maps, and Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP) help visualise model decision pathways. Kavya and Sumathi [] argued for the integration of interpretability as a design principle rather than a post hoc addition. This shift has prompted researchers to design architectures that maintain high accuracy while providing actionable explanations for their outputs.

2.4. Psychological Persuasion in Phishing

Understanding the psychological basis of phishing is critical, as most successful attacks manipulate human cognition rather than exploiting technical vulnerabilities. Drawing from social psychology, researchers have identified persuasive strategies commonly used by attackers—many of which align with Cialdini’s six principles of persuasion: authority, scarcity, social proof, reciprocity, commitment/consistency, and likeability [].

Phishing campaigns frequently impersonate authority figures or institutions to establish credibility. Scarcity and urgency are used to elicit immediate action without critical evaluation. Empirical studies confirm the consistent presence of these tactics. Ferreira and Teles [] developed the Principles of Persuasion in Social Engineering (PPSE) framework to systematise how these strategies co-occur in real-world attacks. For instance, an email may leverage both authority and fear by mimicking a bank and claiming that the user’s account has been compromised.

Detecting persuasive cues requires models to interpret subtle textual signals. However, annotating emails with persuasion principles is resource-intensive, as the labels can be subjective and context-dependent. Li et al. [] highlighted the difficulties in developing reliable coding schemes for persuasion detection, while Bustio-Martínez et al. [] noted that most existing datasets lack detailed annotations for psychological features.

Nonetheless, advances in transformer-based architectures—such as BERT and RoBERTa—enable a nuanced understanding of persuasive language. These models can identify complex cues like emotional appeals, formal tone, or suggestive phrasing that may otherwise go unnoticed. Karki et al. [] found that fine-tuned transformers were particularly adept at detecting manipulative rhetorical structures in phishing emails.

2.5. AI-Generated Phishing Threats

The introduction of large language models (LLMs) such as GPT has transformed the phishing landscape. Unlike earlier phishing attempts that could often be identified through grammatical errors or poor formatting, AI-generated phishing emails are coherent, grammatically correct, and highly contextual. This makes them significantly harder to detect with conventional tools.

Generative AI allows for mass production of phishing emails that are dynamically tailored to specific organisations, job roles, or contexts. Eze and Shamir [] demonstrated how ChatGPT could craft convincing phishing messages from minimal prompts. Opara et al. [] evaluated leading email services against GPT-4o-generated phishing emails and found wide variability: Outlook flagged only 4%, while Yahoo blocked 90%. This discrepancy underscores the evolving threat posed by generative phishing.

To detect AI-generated content, researchers have explored stylometric and semantic features. Gryka et al. [] combined stylometric features such as pronoun ratio, clause density, and sentence rhythm with semantic embeddings, achieving 96% accuracy using an XGBoost ensemble. Similarly, Elongha and Liu [] applied CNN ensembles to domain-specific phishing and found strong performance in healthcare contexts.

However, most existing models are either domain-specific or trained on unreleased datasets, limiting replication and benchmarking. Moreover, few incorporate psychological features alongside semantic and stylometric cues, despite the growing body of research showing their importance in phishing detection.

2.6. Research Gaps and Alignment with This Study

While phishing detection has made substantial strides, significant gaps remain—particularly in handling AI-generated, psychologically manipulative phishing emails. First, there is a dearth of large-scale, diverse, and publicly available datasets labelled with psychological attributes such as persuasion principles. Most corpora are either synthetic, drawn from a single LLM, or lack domain variety [,]. This hinders the development of generalisable models.

Second, many existing models focus on a narrow set of features—linguistic, stylometric, or psychological—without integrating them. This limits their capacity to detect the full spectrum of phishing indicators. Third, despite the importance of interpretability, few studies embed explainability directly into the model pipeline.

This study addresses these challenges through the following:

- Introduces a large, multi-domain corpus of 2995 AI-generated phishing emails, labelled with Cialdini’s persuasion principles;

- Designs a two-stage architecture that combines transformer-based persuasion classification with a dense neural network for phishing detection, thereby integrating psychological and linguistic cues;

- Embeds interpretability via intermediate outputs, making the detection process more transparent and actionable.

This interdisciplinary approach sets a new benchmark in phishing research by combining deep learning, NLP, and behavioural science into a cohesive, scalable framework for detecting AI-generated phishing emails.

3. Technical Background

This section presents the underlying technical background required to understand the methodologies, design, and inherent challenges associated with detecting AI-generated phishing emails. The core objective is to provide the necessary context for subsequent discussions by establishing a foundational understanding of the various relevant interconnected domains.

3.1. Large Language Models for Text Generation

Large language models (LLMs) generate human-like text through a transformer-based architecture that uses self-attention mechanisms []. Each word considers relationships with all other words simultaneously, as opposed to sequentially word by word. Most modern LLMs follow pre-training paradigms in which models learn language patterns through lengthy text processing on vast amounts of data, which enables them to internalise syntactic and semantic patterns across various text types.

Prompt engineering describes techniques that purposefully direct LLM behaviour with carefully created input prompts to facilitate particular outputs from pre-trained models []. This takes advantage of the lengthy conversational and instructional training to follow complex directives and produce appropriate responses []. However, safety mechanisms and content filters designed to prevent misuse, such as the generation of harmful content like phishing emails, are embedded in commercial LLMs. These controls are often implemented using reinforcement learning from human or AI feedback (RLHF/RLAIF) and create use-case guardrails that must be navigated carefully when conducting legitimate security research requiring controlled malicious content generation.

3.2. Cialdini’s Principles of Persuasion as Computational Features

Ref. [] developed a framework to characterise how strategic communication can influence decision-making and invoke actions in others, which are deeply rooted in the known cognitive biases and mental shortcuts often used to navigate through social environments. That being said, these can also be exploited in an adversarial context such as phishing campaigns.

Authority exploits the tendency to comply with figures or entities of perceived authority. This manifests in phishing emails through the impersonation of trusted organisations or official titles, as humans naturally comply when faced with apparent expertise or legitimacy.

Social proof reduces individual resistance to instructions by exploiting the ’herd mentality’, suggesting that the desired actions are common among peers. This implies consensus and attempts to normalise the requested behaviour.

Likeability mimics relationships and simulates familiarity to artificially build trust. These rapport-building techniques exploit the psychological drive to comply with requests from people perceived as similar or friendly.

Reciprocation offers something of desired or perceived value to create artificial feelings of obligation before making a request. People often tend to avoid perceived ungratefulness, and this leads to disproportionate compliance with later requests that often outweigh the value or risk of the initial offerings.

Consistency abuses the psychological tendency to maintain coherence between both commitments and actions, often being observed in phishing as numerous requests sent to a recipient that sequentially escalate after initial small commitments.

Scarcity invokes a sense of time pressure and implicit urgency using loss aversion psychology. Messages are framed such that non-compliance is seen as potentially adverse, leading to immediate action regardless of potential risks.

Social behaviour and communication are extremely complex, and persuasion cannot be attributed to one principle. These psychological mechanisms complement each other and are often used in tandem in effective phishing campaigns. Multi-factor persuasion needs computational approaches capable of detecting multiple simultaneous influential techniques, which is challenging due to their subtle manifestation and frequent variation across cultural and demographic boundaries.

3.3. DistilBERT Architecture and Processing

Transformers are a type of neural network known for advanced NLP capabilities. Self-attention mechanisms are key to parallel text processing while maintaining awareness of relationships between all sequence positions. Transformers do not process words one by one; instead, they simultaneously determine how each word relates to each other word using computational weighting calculations to create contextually relevant representations showing semantic relationships over arbitrary distances.

DistilBERT is a fine-tuned transformer created through distillation learning, whereby a smaller model learns from and thus replicates a larger model’s behaviour. Both the larger training data and probabilistic distributions are used by the smaller model, with much of the complex linguistic understanding transferred to a more efficient architecture. DistilBERT retained 97% of the original performance of BERT with 40% fewer parameters and is, as such, more computationally practical [].

Subword tokenisation through the WordPiece algorithm mitigates vocabulary limitations by using frequency patterns found in training to break down words into smaller components, known as subword tokens. This manages unseen words by decomposing them into familiar subwords while observing the structural relationships between them and related words. Two components are created in order to convert text into transformer input: input IDs, which are just numerical indices symbolising each subword token, and attention masks that act as binary indicators to differentiate actual text content from added padding tokens.

The classification (CLS) token is placed at the sequence start to represent the entire input sequence, combining information from the entire text content using self-attention mechanisms []. The CLS token looks at all other tokens as the transformer processes the sequence, which results in a 768-dimensional vector that holds the entire semantic content of the input. This provides fixed-size summarised versions of inherently variable-length texts for subsequent classification tasks.

3.4. Multi-Label Text Classification

Multi-label classification allows one instance to belong to many different categories, in contrast to multi-class classification, where categories are mutually exclusive. This particular difference is extremely important for persuasion-principle detection, as single texts can potentially exhibit multiple persuasive factors. Architecturally, sigmoid activation functions are needed for each neuron instead of softmax to create independent binary decisions for each label without limiting the total probability across categories [].

Binary cross-entropy loss (BCE) is the mathematical foundation of multi-label training. It measures the prediction quality for each label independently, and then each label is treated as a separate binary classification task. For each label, the difference between the predicted probability and the true binary label is calculated, and these losses are then averaged. This differs from categorical cross-entropy, which operates on a single unified probability distribution across classes.

3.5. Hierarchical Neural Network Architectures

Hierarchical neural architectures create organised processing and computation through multiple specialised stages. Each stage performs processing at various levels of abstraction to break down complex tasks into manageable and interpretable sub-tasks rather than having one model mapping initial raw inputs to final outputs [].

Using one trained model’s probabilistic outputs as input features for another combines the representation learning abilities of deep neural networks with traditional feature engineering interpretability. As such, this creates a feature space that has complex learned patterns that remain accessible to human analysis. When initial models output continuous probability (’confidence’) scores, they provide informative encoded features representing patterns from the original input data.

Dense neural networks with interconnected layers and neurons are capable of processing structured feature spaces at low dimensionalities. Moreover, these architectures are able to learn non-linear feature relationships with iterative transformations, which is useful for extracted or pre-processed features from other models rather than high-dimensional raw data. Also important is feature concatenation, which represents multiple feature types in a singular input vector and enables neural networks to determine individual feature importance and inter-feature interactions with transformations while holding onto information from different pathways. Regularisation techniques can reduce overfitting and improve generalisation, including: dropout (randomly zeroing neurons during training), batch normalisation (normalisation of layer inputs), and weight decay (penalising large parameters).

3.6. Transfer Learning

Transfer learning tailors knowledge from large pre-trained tasks to domain-specific functions so that its understanding of linguistic and semantic relationships can be shared for different text processing tasks. The process begins with standard pre-training on vast datasets, after which fine-tuning takes place on smaller and specific labelled datasets to adjust general representations to distinct tasks [].

During pre-training, these models develop a broad linguistic understanding to identify grammatical, semantic, and individual word relationships in text, which creates a strong foundation for more specialised tasks. Fine-tuning maintains the valuable generalised knowledge gained from pre-training while adjusting those learned representations to a specialised task.

The adaptations that take place during fine-tuning can be controlled using layer freezing, which puts specific layers of the pre-trained model in a constant state while others continue to adjust to the new task requirements. The lower layers that are typically responsible for identifying core linguistic patterns are usually frozen to maintain a basic understanding of the language, while higher layers are fine-tuned to learn new decision thresholds and feature representations. Catastrophic forgetting describes the tendency of neural networks to lose previously learned knowledge once trained on new tasks, which is mitigated by selective layer freezing, conservative learning rates, and regularisation techniques.

4. Design

This section details the technical design and implementation of the AI-generated phishing detection model.

4.1. Overview of Requirements

The detection system must classify emails as phishing or legitimate, incorporating persuasion-principle analysis. It must include a labelled dataset containing AI-generated phishing emails with defined psychological features, basic and extended evaluation metrics, and a two-stage architecture optimised for resource-constrained environments. Additional functionality, such as model interpretability, efficient regularisation, and appropriate training configurations, should support performance, reliability, and reproducibility.

4.2. Dataset Design

4.2.1. Dataset Structure and Generation

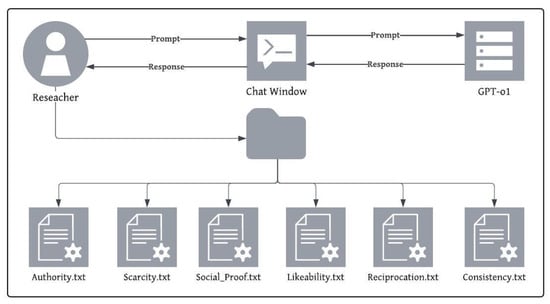

Initial evaluation tested multiple LLMs for their ability to produce persuasive phishing emails. Claude 3.7 Sonnet and Microsoft Copilot were the most restrictive, providing minimal usable outputs. ChatGPT-o1, Gemini 2.5 Pro, and LLaMA 4 were more flexible, with ChatGPT demonstrating the most consistent outputs across different sessions. The overall prompt engineering and phishing email generation workflow is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Prompt Engineering and Phishing Email Generation Process.

Data was generated using GPT-o1 with a prompt framework targeting each of Cialdini’s six persuasion principles. The prompt was kept objective and reproducible, avoiding conversational noise and minimising human input while still allowing diversity. Prompts generated 15 phishing emails for each persuasion principle, ensuring contextual variation across five organisational types (e.g., educational, governmental). These were output in standardised JSON format for streamlined parsing and integration. The JSON structure used for storing each generated email is shown in Listing 1.

| Listing 1. AI-Generated Phishing Email JSON Output Structure. |

| [ { "email_id": string, "primary_factor": string, "secondary_factor": string, "organisation_type": string, "complexity": string, "length": string, "subject" : string, "body" : string, "label": string, }, … ] |

Each email included one primary and one secondary persuasion principle. Larger batch generations (e.g., 40+ per prompt) were trialled but produced repetitive, lower-quality outputs. Limiting to batches of 15 improved content diversity and allowed effective manual validation to check uniqueness and plausibility.

4.2.2. Dataset Composition and Distribution

The final dataset contained 2995 unique AI-generated phishing emails, equally distributed across six persuasion principles. This is the largest such dataset documented in the literature that is specifically structured around cognitive persuasion indicators.

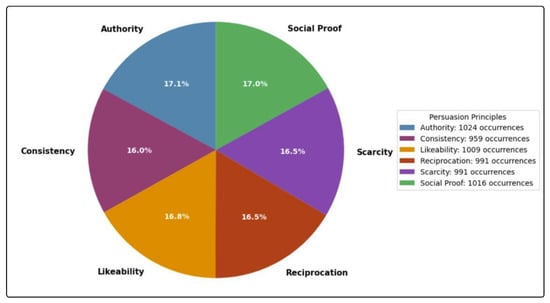

In total, there were 5990 occurrences of persuasion principle across primary and secondary factors, with just a 2.2% spread across categories (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of Cialdini’s Persuasion Principles in the AI-Generated Phishing Email Dataset.

To support classification, 1000 legitimate emails from the University of Twente dataset [] were included. These messages exhibit high linguistic quality, minimal grammatical errors, and a professional tone—features aligned with the generated phishing content. Although the 3:1 class imbalance (phishing to legitimate) may appear unrepresentative of real-world scenarios, quality was prioritised, and this limitation is well documented in the cybersecurity literature.

The legitimate emails generally demonstrated more positive sentiment. While this reflects natural workplace communication, it could complicate the detection of loss-framed (negative-sentiment) phishing attempts.

4.3. Model Architecture

A two-stage architecture was chosen for its balance of interpretability and performance. The first model classifies persuasion principles, and the second uses the output to detect phishing attempts. This design supports more transparent classification decisions and allows for targeted optimisation.

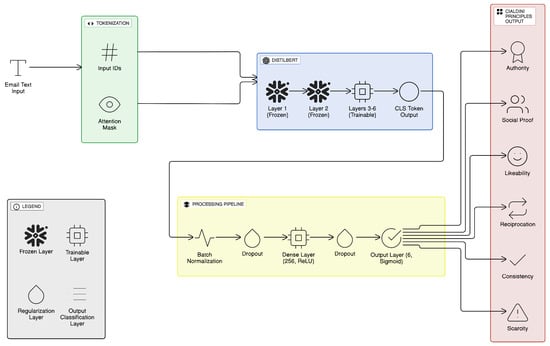

4.3.1. Model 1: Multi-Label Persuasion-Principle Classifier

Model 1 uses DistilBERT, a lightweight transformer model that retains 97% of BERT’s performance with 40% fewer parameters []. This efficiency was critical due to the resource-constrained training environment (limited GPU availability and cloud session time limits). The architecture of Model 1 is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Model 1 Architectural Overview.

The model processes each email by first applying tokenisation (input IDs and attention masks) with a 256-token cap. The CLS token is used to extract a 768-dimensional vector representing the entire message’s semantic content. Two layers of the pre-trained transformer were frozen to preserve general linguistic understanding while fine-tuning upper layers for persuasion classification.

Regularisation strategies were implemented to reduce overfitting:

- Batch normalisation: Stabilises training when mixing pre-trained and new layers.

- Dropout (0.5, then 0.3): Introduced at different layers to generalise beyond specific phrasing.

- Dense layer (256 ReLU units, L1 and L2 regularisation): Encourages sparse and robust feature usage across diverse linguistic structures.

- Output layer: A six-unit sigmoid activation layer enables multi-label classification, suitable for non-exclusive principles.

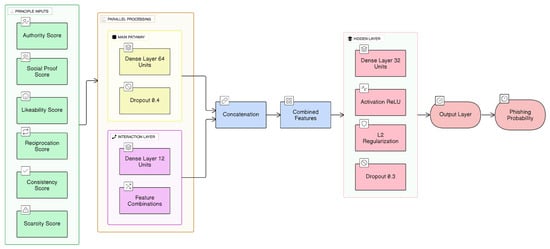

4.3.2. Model 2: Binary Phishing Classifier

Model 2 receives the six-dimensional persuasion-principle confidence scores as input and classifies whether the email is phishing. Its architecture is designed for structured, low-dimensional input rather than text. The architecture of Model 2 is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Model 2 Architectural Overview.

The design includes the following:

- Feature concatenation: Merges a dense pathway (64 units) and an interaction pathway (12 units) to consider both independent and relational features.

- Hidden layer (32 ReLU units with L2 regularisation): Enables non-linear transformations to define complex decision boundaries.

- Dropout (0.3): Further reduces overfitting to persuasion-principle combinations.

- Sigmoid output unit: Outputs a probabilistic binary classification.

The model contains 3029 trainable parameters, calibrated for generalisation without capacity for memorisation.

4.3.3. Training Configuration

The models were trained independently with task-specific parameters. Both used the Adam optimiser, early stopping (patience of 12 epochs), label smoothing (0.15), and a batch size of 16. Learning-rate schedules were adjusted based on validation plateau detection.

- Model 1: Learning rate = ; validation AUC monitored.

- Model 2: Learning rate = ; validation AUC-ROC monitored.

This configuration balanced convergence speed with learning stability across different model tasks.

4.4. Design Limitations

There are several technical and methodological constraints. Firstly, using GPT-o1 for data generation may result in outputs that overfit to that model’s language patterns, limiting generalisation to phishing emails from other sources. A broader range of LLMs could improve robustness, but due to resource constraints, we did not include others.

Second, only English-language emails were generated. This affects applicability to multilingual and cross-cultural phishing contexts, which can use different linguistic cues for persuasion.

Third, the 3:1 imbalance between phishing and legitimate emails does not reflect real-world email traffic. However, this trade-off was necessary to maximise data quality and coverage of the six persuasion categories.

Fourth, errors in the first model (persuasion-principle classification) can propagate to the second, affecting phishing detection performance. Hierarchical structures often face this cascading error problem.

Finally, the 256-token cap of DistilBERT may truncate long emails, potentially excluding important context or indicators of persuasion, though this limit was necessary to manage training efficiency under constrained cloud resources.

While the 256-token cap was chosen to manage resource constraints during training, real-world emails can be significantly longer. For deployment, several adaptations are possible, such as applying a sliding-window approach to process overlapping chunks of text, summarising long emails before classification, or adopting transformer architectures optimised for extended sequences (e.g., Longformer, BigBird). These strategies are designed to preserve the broader context while maintaining manageable computational requirements.

4.5. Ethical Considerations

This research involves the creation and analysis of realistic phishing emails, raising clear ethical considerations. Firstly, the generated content is not used to conduct actual phishing attempts, and similarly, the research emphasis is on detection and prevention as opposed to cultivating novel attack techniques. In addition, the AI-generated phishing emails are not directly distributed to anyone, nor are they publicly accessible through open repositories (e.g., GitHub). The dataset does not contain any PII, and this is explicitly excluded in the generative prompt. Also, the model is run in a contained environment.

4.6. Evaluation

This section details the chosen evaluation methodology tailored to the hierarchical two-stage detection design, outlining the specific requirements of multi-label persuasion-principle classification and binary phishing detection. The evaluation uses a quantitative analytical approach with particular metrics appropriate for each architecture.

4.6.1. Performance Metrics

Core performance metrics, such as F1-score, precision, recall, and AUC-ROC, are used to obtain the foundational insights of this evaluation. In particular, AUC-ROC is prioritised, as it produces performance evaluations that are independent of defined thresholds. This helps establish the model’s ranking ability over all decision cut-offs rather than fixed boundaries and can indicate whether there is a degree of random guessing (AUC of 0.5) or good discrimination, with values closer to 1.0.

4.6.2. Model-Specific Metrics and Validation

The first model performs multi-label classification, necessitating macro-averaged metrics over all six principles to provide an overall performance evaluation. Performance analysis of individual principles identifies which psychological techniques are most reliably detected, and vice versa, allowing targeted recommendations for improvement.

The second binary phishing classification model is observed directly with all metrics. There is particular emphasis on recall to minimise missed phishing emails (false negatives), acknowledging the security context where missed threats are more costly than false positives, although this will not be considered in isolation to form more realistic evaluations. Precision–recall balance ensures practical usability.

4.6.3. Cross-Validation Methodology

The performance estimates for Model 1 are robust, using 5-fold stratified cross-validation to observe proportionate persuasion-principle distributions over different folds. This gives performance consistency measures for all performance metrics and reduces any overfitting bias with multiple independent evaluations. Model 2 uses standardised 80/20 train–test splits, with stratification based on phishing and legitimate labels to maintain class balance during evaluation. Statistical analysis across cross-validation folds uses mean and standard deviation calculations to assess performance consistency and reliability.

4.6.4. Persuasion-Principle Score Distribution Analysis

The separation effectiveness of each principle can be deduced by examining the distribution between the scores for legitimate and phishing emails. This also identifies threshold sensitivity and any score-range overlaps that are indicative of challenges in classification. Statistical analysis makes use of descriptive statistics and separation analysis compared against the 0.5 threshold to quantify the discriminative power of each psychological technique.

4.6.5. Linguistic Profile Comparison

Eight textual metrics form the basis of stylometric feature comparisons between AI-generated phishing and legitimate emails. The metrics include the following:

- Frequencies of part-of-speech (POS) categories (pronouns, verbs, and nouns);

- Measurements of text structure (sentence and word length);

- Diversity indicators;

- Readability scores derived from the Coleman–Liau index;

- Sentiment analysis.

This identifies any intrinsic differences in emotional tone, general readability, linguistic diversity, lexical styles, or structural complexity between these email groups.

4.6.6. Misclassification Analysis

The errors of Model 2 are analysed through the true positives, false positives, true negatives, and false negatives of a confusion matrix to identify any core failures and classification boundaries. Importantly, categorising errors provides the foundational understanding necessary to identify model limitations and makes recommendations for improvements more relevant.

4.6.7. Statistical Analysis Framework

The mean and standard deviation results of the combined cross-validation folds are calculated and analysed to assess the consistency and reliability of the model. This is in addition to the persuasion-principle score separation and cross-fold iteration analysis previously mentioned.

4.6.8. Considerations for Validity

Considerations were made to ensure the evaluation’s validity:

- Internal validity: Cross-validation and random seeding (1) made core computations reproducible while also giving reliable performance over multiple evaluation runs.

- External validity: Training and validation splits test model generalisation more comprehensively than only training examples and demonstrate real-world feasibility.

- Statistical significance: Consistency analysis over cross-validation folds gives measures of overall performance reliability and justifies the result’s validity.

5. Results

This section presents the empirical results for the two-stage AI-generated phishing detection model. This involves evaluating the performance of the first model in persuasion-principle detection and the effectiveness of the second model for binary phishing classification, as well as further linguistic analysis.

5.1. Model 1: Persuasion-Principle Detection Performance

5.1.1. Cross-Validation Results

Model 1 demonstrated strong performance throughout five-fold cross-validation, with a mean AUC of 0.9008 (±0.0056). Table 1 illustrates that the individual AUC scores exhibited minimal variance between folds, within the range of 0.8948 to 0.9083, indicating stable model performance.

Table 1.

Five-Fold Cross-Validation AUC and Accuracy Scores for Model 1.

The mean accuracy of 0.3856 (±0.0148) was low, although this was expected for a multi-label classification model, which must match all six persuasion-principle scores simultaneously.

5.1.2. Distribution of Persuasion Principles in the Dataset

The dataset demonstrated a relatively balanced representation of all six principles across primary and secondary factors. The occurrence rates for the persuasion principles ranged from 32.0% for consistency to 34.2% for authority, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Distribution of persuasion principles in phishing email corpus ().

The numerical difference between the least and most often occurring principles was 65, which is insignificant and demonstrates that a single principle did not dominate the training process.

5.2. Persuasion-Principle Score Analysis

5.2.1. Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics presented in Table 3 demonstrate that likeability and reciprocation were most prevalent in legitimate emails, having the highest means (0.645 and 0.539) and displaying the closest inter-quartile ranges (0.608–0.670 and 0.505–0.597).

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics for persuasion-principle scores of legitimate emails () and phishing emails ().

Indicators of authority, scarcity, and social proof were represented to a lesser extent, with the mean of social proof being 0.276 and the maximum being 0.384. In contrast, the representation of persuasion principles in phishing emails was significantly more balanced, with no single principle dominating the underlying semantic context.

Negatively framed and urgency-based principles were found more often in phishing emails, with the mean for authority rising from 0.350 to 0.451, while scarcity and social proof climbed to 0.446 and 0.454, respectively.

The confidence scores exceeded the 75th percentile of legitimate email scores, which was expected, as phishing emails typically demonstrate stronger indicators of most persuasion principles. The standard deviation was consistently higher across the phishing emails, reflecting varied writing styles from the LLM, whereas legitimate emails came from a limited set of senders.

5.2.2. Discriminative Analysis

The frequency with which each principle crossed the decision boundary is quantified in Table 4. Social proof, authority, and scarcity were much more prevalent in phishing emails (ratios > 4:1) and, therefore, highly discriminative for the second classifier.

Table 4.

Percentage of emails with persuasion-principle scores exceeding the 0.5 decision threshold.

Conversely, likeability and reciprocation were present in the overwhelming majority of legitimate emails, attributable to the largely positive tone observed during dataset analyses.

5.3. Model 2: Binary Phishing Classification Performance

5.3.1. Overall Performance Metrics

This model achieved remarkable results for a novel approach with few benchmarks. The AUC-ROC was 98.40%, confirming excellent separability, nearly independent of thresholds, as detailed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Overall performance of Model 2 on the held-out test set ().

A precision of 97.4% indicates minimal disturbance to end-users from misclassified legitimate emails, while an F1-score of 96.02% indicates that the results were not due to training biases.

5.3.2. Confusion Matrix Analysis

The confusion matrix in Table 6 shows that 567 phishing emails (94.7%) were correctly classified, with only 14 legitimate emails (7%) incorrectly flagged.

Table 6.

Confusion matrix of Model 2 predictions.

The model missed 32 phishing emails, achieving a recall ≥ 95%. Maintaining a 5% false negative rate without reducing precision would reduce active threats while avoiding excessive misclassifications.

5.3.3. Class-Specific Performance

Performance favoured phishing detection, and the model was more accurate in detecting phishing emails (0.97) than legitimate emails (0.85), although recall was high for both (0.93 and 0.95). This is clearly illustrated in Table 7.

Table 7.

Per-class performance metrics for Model 2.

The class imbalance remains a limitation, but the macro-average F1-score of 0.92 demonstrates balanced treatment of both classes.

5.4. Training Dynamics

Convergence Analysis

Table 8 displays the training and validation curves for both models across epochs. Model 1 achieved an optimal validation AUC of 0.9173 at epoch 27, with early stopping triggered at epoch 39.

Table 8.

Training–validation dynamics for Model 1 and Model 2.

The validation loss for Model 1 decreased from 5.1913 at epoch 1 to 2.6550 at epoch 27, with a consistent learning rate. Model 2 reached optimal performance at epoch 40, with most AUC improvements occurring in the first five epochs, and no early stopping was triggered.

5.5. Linguistic Analysis

Stylistic Comparison

Linguistic analysis showed that AI-generated phishing emails had distinct characteristics compared to legitimate emails, with all textual descriptors, except for verb frequency, being statistically significant (see Table 9).

Table 9.

Stylometric comparison of AI-generated phishing and legitimate emails.

Phishing emails contained far fewer pronouns, more nouns, and longer words. The POS diversity and sentiment polarity results indicated that legitimate emails were more positively framed and had more varied sentence structures. Most notably, the Coleman–Liau Index was much higher for phishing emails (19.849) than for legitimate ones (8.487), indicating significantly greater complexity.

The evaluation results for the two-stage phishing detection model demonstrated strong performance across most metrics. Model 1 effectively extracted discriminative persuasion-principle features (AUC = 0.9173), which were then used by Model 2, achieving 94.12% accuracy and a minimal 5% false negative rate in binary classification. The linguistic analysis confirms significant stylistic differences, validating semantic analysis as an effective phishing detection approach.

6. Discussion

6.1. Critical Analysis, Interpretation, and Comparison with Existing Research

Overall, the hierarchical detection approach shows that persuasion principles provide strong representations of features for AI-generated phishing detection. The 90% AUC achieved by Model 1 demonstrates that Cialdini’s framework is discriminative, although its multi-label accuracy was low at 38%. This gap was expected because partial persuasion-principle predictions were considered incorrect, yet the high AUC confirms that the model still classified the emails correctly. The quality of these intermediate scores was used by the second model, which achieved 94% accuracy and 98% AUC on the final binary classification task.

The analysis of persuasion-principle scores reveals clear differences in effectiveness. Authority, scarcity, and social proof were highly separable, with a 4:1 ratio of phishing to legitimate emails. Notably, reciprocation and likeability appeared most frequently in legitimate emails, reflecting their positive and friendly tone. Psychological theory aligns with these observable patterns, demonstrating that authority and scarcity likely trigger loss avoidance, while normal workplace and social familiarity are reflected in reciprocation and likeability.

Model 2’s high 97% precision kept false positives low, and, as demonstrated by its 95% recall, AI phishing threats were rarely missed. Among 599 phishing emails, only 32 were not detected, indicating that the approach handled different styles of writing well and was not dependent on a specific combination of persuasion principles.

The additional linguistic analysis supports this, as AI-generated phishing emails had nearly double the Coleman–Liau readability score of legitimate emails and used fewer pronouns but more nouns. This creates the formal, impersonal tone expected of phishing communications, where recipients are often addressed vaguely or impartially. Persuasion-principle-based semantic cues and these stylistic fingerprints both highlight the same difference: language generated by large language models is more complex and detached. That said, the prompt used was very specific, whereas other generalised or unrelated prompts may be interpreted differently.

The 94% accuracy places the approach in close standing with, or above, most recent work, despite their limitations (Table 10).

Table 10.

Performance comparison with recent AI-generated phishing studies.

Ref. [] reported 96% accuracy with an XGBoost model using many stylometric features, but their dataset was extremely small. Likewise, [] achieved 98.8% accuracy using an ensemble CNN approach built specifically for healthcare-related phishing emails. The work is significantly more comprehensive, covering five organisational sectors and providing a more interpretable two-stage design as opposed to one black-box model. Opara’s methodology also demonstrates how commercial-grade email services still struggle, as Outlook classified only 4% of AI-generated phishing emails, while Yahoo used overly aggressive filtering methods to achieve high detection rates. The work exhibits high recall with a marginal 7% false-positive rate for legitimate emails, equivalent to 1.75% of the total test set, while maintaining a justifiable balance for real-world applications.

6.2. Unexpected Findings, Implications, and Methodology Effectiveness

At a fixed 0.5 threshold, no legitimate email in this sample exceeded the social-proof score, yielding apparent separation under that cut-off. However, a manual inspection of misclassified emails indicated that a number of phishing emails with extraneous social-proof values were missed. This is indicative of the approach’s inability to detect some subtle consensus phrases. Another interesting finding was that AI-generated text was highly complex and, as such, the long-winded and technical sentences actually served as an effective phishing indicator.

Training behaviour also differed by stage, with Model 1 ceasing to improve after about 30 epochs, whereas Model 2 iteratively improved until the final (40th) epoch. This suggests that engineered scores are less likely to overfit than raw text content.

The two-stage design uses a small classifier with only 3029 trainable parameters in Model 2. Despite this, it still performs better than comparatively larger approaches. It also has clear intermediate confidence scores that show which persuasion principles were detected, which is adequately comprehensive for both subsequent evaluation and fine-tuning.

6.3. Limitations, Validity, and Recommendations

This study demonstrates the feasibility and interpretability of a novel two-stage approach at this scale. That being said, there are several limitations and opportunities for future work to consider. The dataset used emails generated by one large language model, which may cause results to vary when using another model. The emails were only in English, leaving cross-language performance untested. The imbalanced 4:1 ratio of phishing to legitimate emails reflects dataset availability rather than real inbox conditions, so thresholds will require tuning in deployment. In addition, the 256-token cap used during model training may truncate longer emails. While this decision was necessary for resource management, future implementations could apply sliding-window tokenisation, semantic summarisation, or long-sequence transformer variants (e.g., Longformer, BigBird) to preserve broader contexts. All principles were subject to a 0.5 threshold, as significant imbalances in legitimate email tone and sentiment were identified early on. Moreover, results may become less relevant as new language models emerge. The emails generated for this study were kept securely and never sent to real users.

Taking these limitations into account, the following recommendations are considered to have the greatest ROI impact:

- Add stylometric features: Include readability scores and pronoun frequency in persuasion-principle scores to improve phishing detection capabilities, which currently produce some false negatives.

- Dataset diversification: Regenerate aspects of the phishing email dataset using different language models to reduce reliance on the writing patterns of a single model and ensure robustness against future AI developments.

- Add more social-proof examples: Implement more training samples that purposefully represent social-proof cues and language, as subtle overlapping phrases can lead to misclassifications.

- Create a more extensive legitimate email corpus: Collect and include more legitimate emails, including those across different professional domains, to address data quality gaps that contributed to the 4:1 class imbalance and to reduce false positives caused by narrow legitimate email styles.

- Use adversarial fine-tuning: Scrutinise the current results and interpretations by generating varied phishing emails over time to conduct fine-tuning, keeping the approach effective against evolving AI models.

- Calibration and thresholds: Explore probability calibration and ROC/PR-driven threshold selection, which were not addressed here, in future work.

- Add stylistic comparisons: Stylometric analysis provides supporting evidence, but multiple-comparisons correction and effect sizes would add greater statistical context and should be incorporated into subsequent studies.

- Expand on class-specific performance: Report specificity (TNR), FPR/FNR, and AUCPR alongside ROC-based metrics for each class to better reflect operational settings with class imbalance. Threshold sweeps should also be considered to characterise precision–recall trade-offs.

6.4. Conclusions

This study set out to address significant gaps in the academic understanding of AI-generated phishing email detection through three primary contributions to the current literature. First, it develops a novel two-stage detection approach that combines language model embeddings with persuasion-principle analysis to achieve 94% accuracy with notable interpretability. Second, it proposes the largest publicly described AI-generated phishing email corpus to date, with 2995 emails labelled with persuasion principles across five organisational sectors, creating a new benchmark for future work. Finally, it provides empirical evidence that persuasion principles and psychological cues can be effectively detected even in the shifting threat landscape of automated AI phishing. Importantly, this work highlights the continued importance of behavioural theory in email and cybersecurity.

The wider effects are that security tooling capable of understanding what an email is trying to say, rather than only considering surface-level appearances, can outperform conventional filtering approaches. These same principles can be applied to detect other malicious AI-generated content, such as fake reviews and social media misinformation. The study’s limitations and risks to validity are discussed above, along with clear recommendations for refinement and adaptation.

6.5. Future Research

This study highlights several avenues for future work. First, the legitimate emails used for training and evaluation were drawn from a single academic dataset, which limits diversity. Although this provided a useful benchmark, the stylistic gap between these legitimate samples and the AI-generated phishing emails may have simplified the classification task. Future research should therefore validate the framework against a broader and more heterogeneous set of legitimate emails from multiple sectors to ensure robustness in real-world environments.

Second, an informal observation suggested that some misclassified phishing emails contained subtle social-proof cues, a finding that warrants deeper investigation. Future work could systematically analyse misclassifications to uncover recurring patterns and, importantly, expand training data to include richer and more nuanced examples of social proof to improve detection performance.

Finally, as large language models continue to evolve, their outputs are likely to become increasingly indistinguishable from legitimate human writing, which could reduce the effectiveness of stylometric approaches. However, persuasion-based cues are grounded in enduring psychological principles that underpin social engineering attacks and are therefore less likely to fade over time. Future research could further explore this robustness, framing persuasion-informed models as more resilient to advances in generative AI and highlighting their long-term potential for phishing detection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, P.T. and H.S.L.; methodology, P.T.; software, P.T.; validation, P.T.; formal analysis, P.T.; investigation, P.T.; resources, P.T.; data curation, P.T.; writing—original draft preparation, P.T. and H.S.L.; writing—review and editing, P.T. and H.S.L.; visualisation, P.T.; supervision, H.S.L.; project administration, H.S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data and prompts utilised as part of this research are not available due to ethical restrictions. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Micro, T. Top 15 Phishing Stats to Know in 2024. Trend Micro News Web Article, 2024. Available online: https://news.trendmicro.com/2024/07/22/phishing-stats-2024/ (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Cveticanin, N. Phishing Statistics & How to Avoid Taking the Bait. Dataprot Web Article, 2023. Available online: https://dataprot.net/statistics/phishing-statistics/ (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- IBM. Cost of a Data Breach 2024. IBM Report, 2024. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/reports/data-breach (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Cialdini, R.B. The science of persuasion. Sci. Am. 2001, 284, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooson, M. UK Remote and Hybrid Working Statistics. Forbes Advisor UK Web Article, 2024. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/uk/advisor/business/remote-work-statistics/ (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Fette, I.; Sadeh, N.; Tomasic, A. Learning to detect phishing emails. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on World Wide Web (WWW ’07), Banff, AB, Canada, 8–12 May 2007; pp. 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagui, S.; Nandi, D.; Bagui, S.; White, R.J. Classifying phishing email using machine learning and deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Cyber Security and Protection of Digital Services (CyberSecPODS), Oxford, UK, 3–4 June 2019; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Q. Text spam neural-network classification algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Communications, Circuits and Systems (ICCCAS), Chengdu, China, 28–30 July 2010; pp. 466–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metsis, V.; Androutsopoulos, I.; Paliouras, G. Spam filtering with naive Bayes-Which naive Bayes? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 3rd Conference on Email and Anti-Spam (CEAS 2006), Mountain View, CA, USA, 27–28 July 2006; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Shams, R.; Mercer, R.E. Classifying spam emails using text and readability features. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 13th International Conference on Data Mining, Dallas, TX, USA, 7–10 December 2013; pp. 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, A.; Abuhasan, A. An intelligent classification model for phishing-email detection. Int. J. Netw. Secur. Its Appl. 2016, 8, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdy, S.; Abouelseoud, Y.; Mikhail, M. Efficient spam- and phishing-email filtering based on deep learning. Comput. Netw. 2022, 206, 108826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavifar, S.; Ghorbani, A.A. Application of deep learning to cybersecurity: A survey. Neurocomputing 2019, 347, 149–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavya, S.; Sumathi, D. Staying ahead of phishers: A review of recent advances and emerging methodologies in phishing detection. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.; Teles, S. Persuasion: How phishing emails can influence users and bypass security measures. Int. J.-Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2019, 125, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, D.; Wu, B. Detection method of phishing email based on persuasion principle. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 4th Information Technology, Networking, Electronic and Automation Control Conference, Chongqing, China, 12–14 June 2020; pp. 571–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustio-Martínez, L.; Herrera-Semenets, V.; García-Mendoza, J.L.; González-Ordiano, J.Á.; Zúñiga-Morales, L.; Sánchez Rivero, R.; Quiróz-Ibarra, J.E.; Santander-Molina, P.A.; van den Berg, J.; Buscaldi, D. Towards automatic principles of persuasion detection using a machine-learning approach. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, B.; Abri, F.; Siami Namin, A.; Jones, K.S. Using transformers for identification of persuasion principles in phishing emails. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Big Data, Osaka, Japan, 17–20 December 2022; pp. 2841–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, C.S.; Shamir, L. Analysis and prevention of AI-based phishing email attacks. Electronics 2024, 13, 1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opara, C.; Modesti, P.; Golightly, L. Evaluating spam filters and stylometric detection of AI-generated phishing emails. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 276, 127044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryka, P.; Gradoń, K.; Kozłowski, M.; Kutyła, M.; Janicki, A. Detection of AI-generated emails-A case study. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security (ARES 2024), Vienna, Austria, 30 July–2 August 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elongha, G.; Liu, X. Detecting AI-generated phishing emails targeting healthcare practitioners using ensemble techniques. SSRN in press. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Petrov, I. Advanced strategies for detecting and preventing AI-generated phishing attacks. Innov. Comput. Sci. J. 2024, 10, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2017), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; 2017; Volume 30, pp. 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.B.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language models are few-shot learners. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 6–12 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Yuan, W.; Fu, J.; Jiang, Z.; Hayashi, H.; Neubig, G. Pre-train, prompt, and predict: A systematic survey of prompting methods in natural-language processing. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 55, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanh, V.; Debut, L.; Chaumond, J.; Wolf, T. DistilBERT, a distilled version of BERT: Smaller, faster, cheaper and lighter. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.01108. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T. Two-way multi-label loss. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 7476–7485. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Yang, D.; Dyer, C.; He, X.; Smola, A.; Hovy, E. Hierarchical attention networks for document classification. In Proceedings of the 2016 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, San Diego, CA, USA, 12–17 June 2016; pp. 1480–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miltchev, R.; Rangelov, D.; Genchev, E. Phishing-Validation Emails Dataset; Dataset; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).