Realization of a Gateway Device for Photovoltaic Application Using Open-Source Tools in a Virtualized Environment †

Abstract

1. Introduction

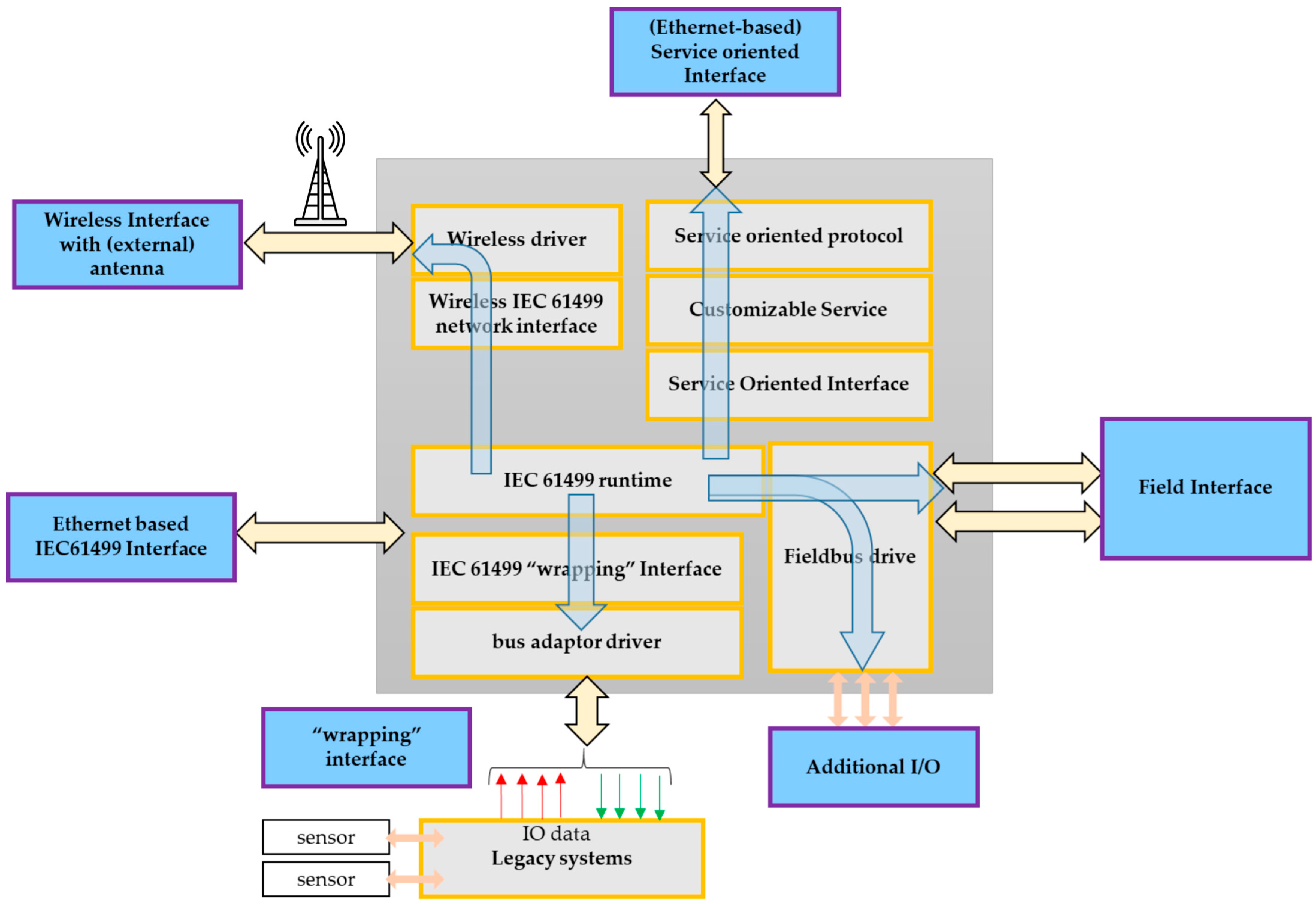

2. Literature and Review on the IEC 61499 Standard

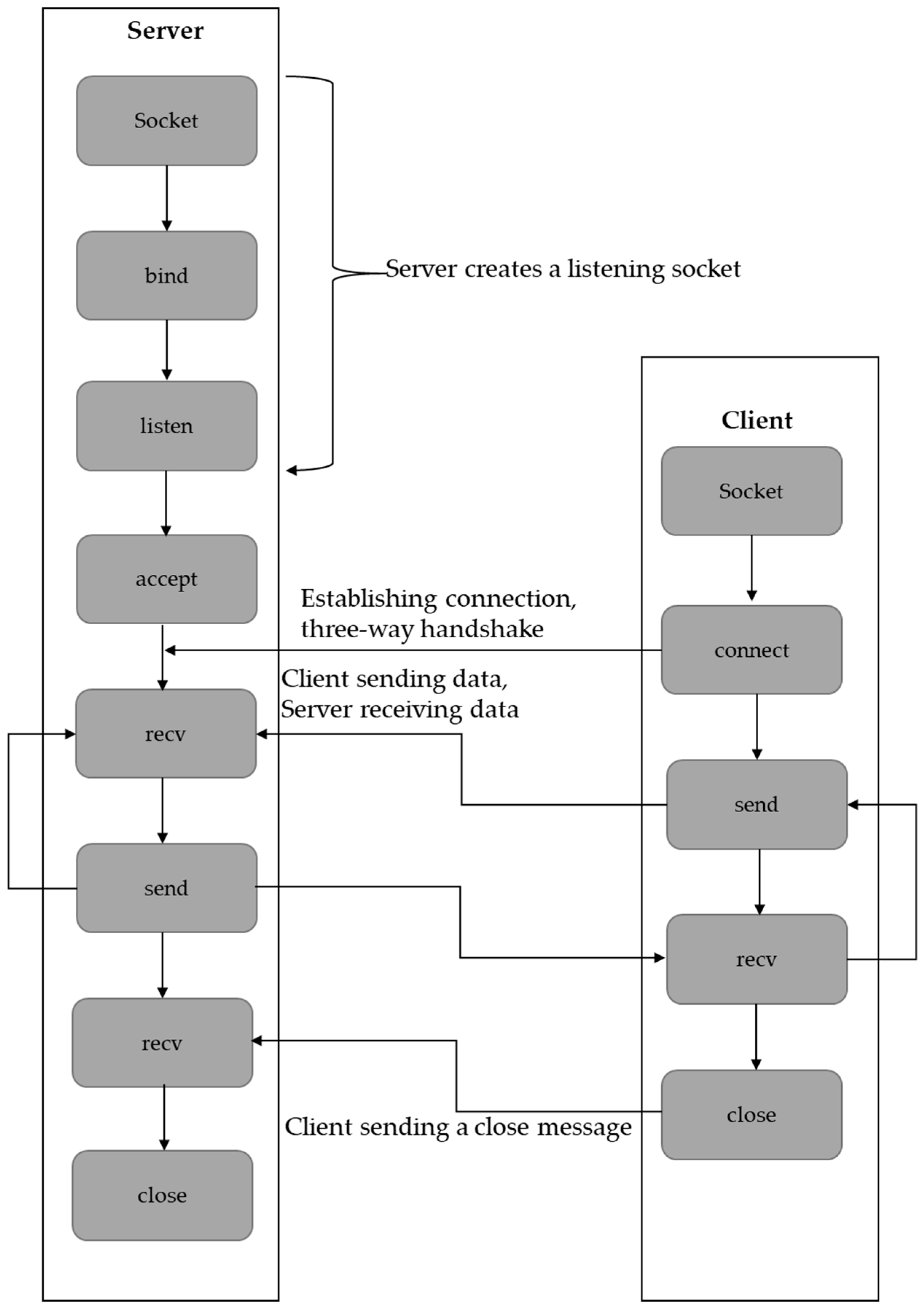

3. MATLAB TCP Communication

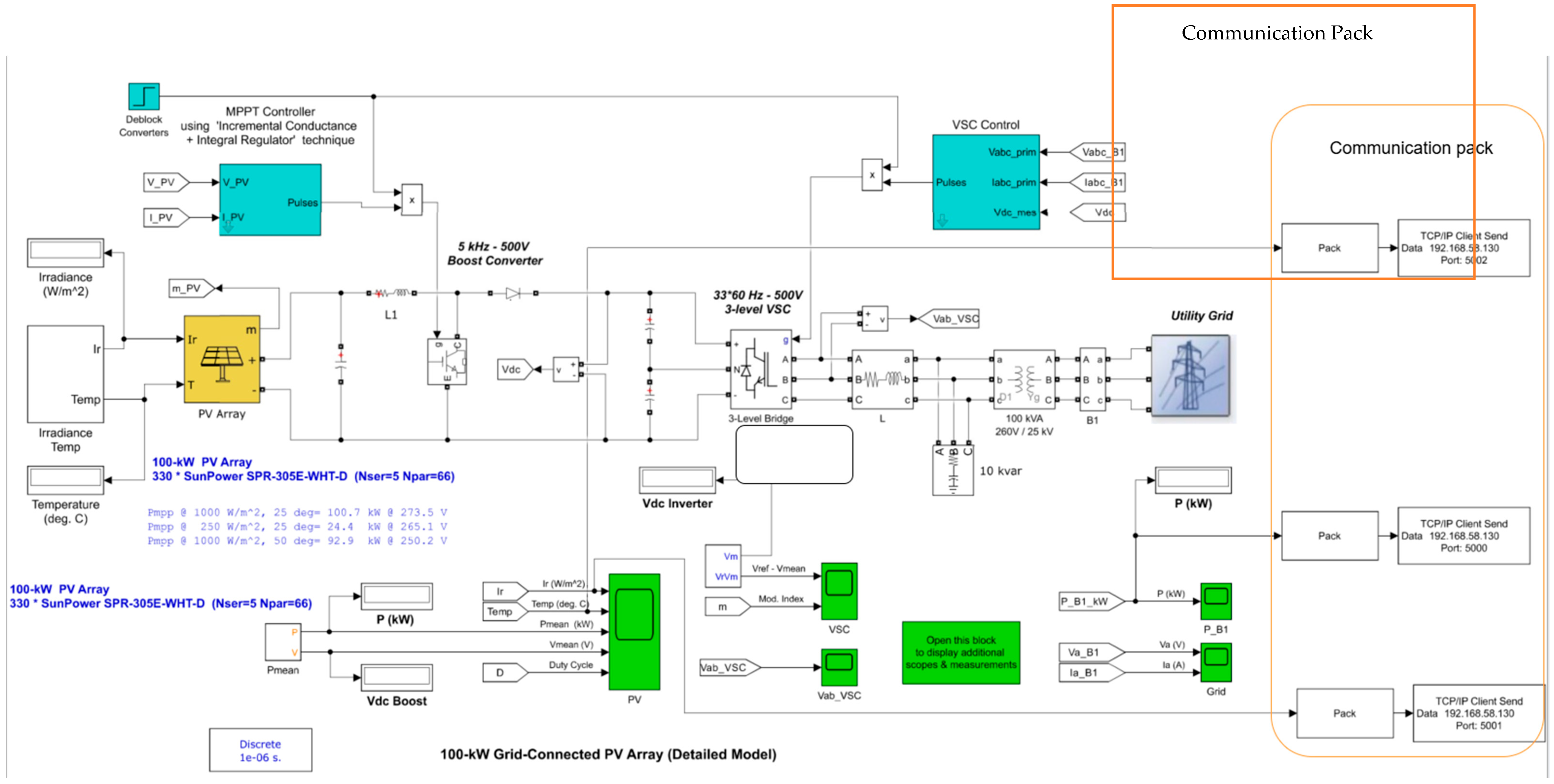

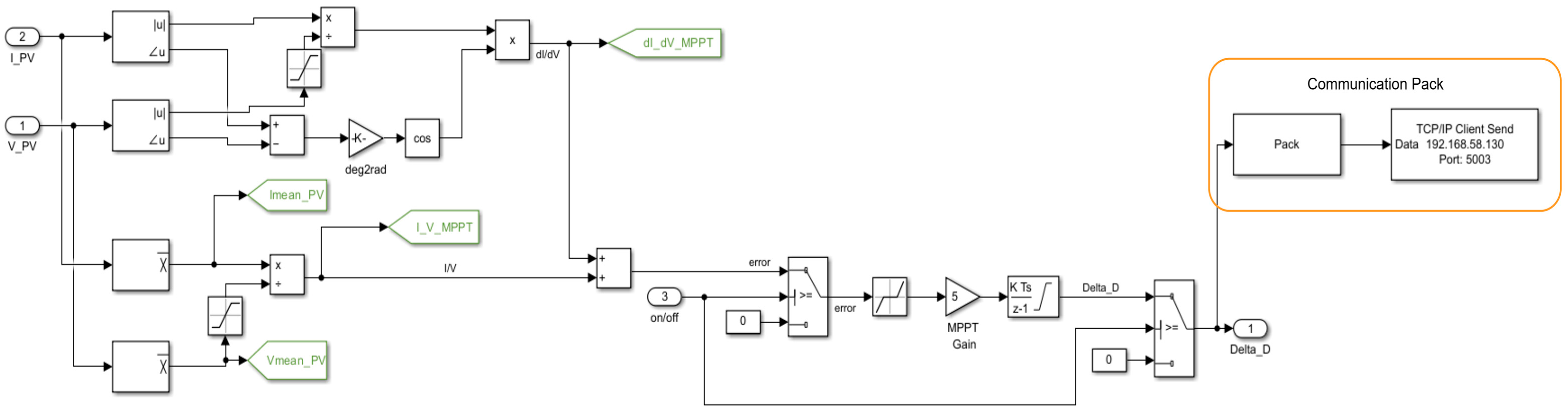

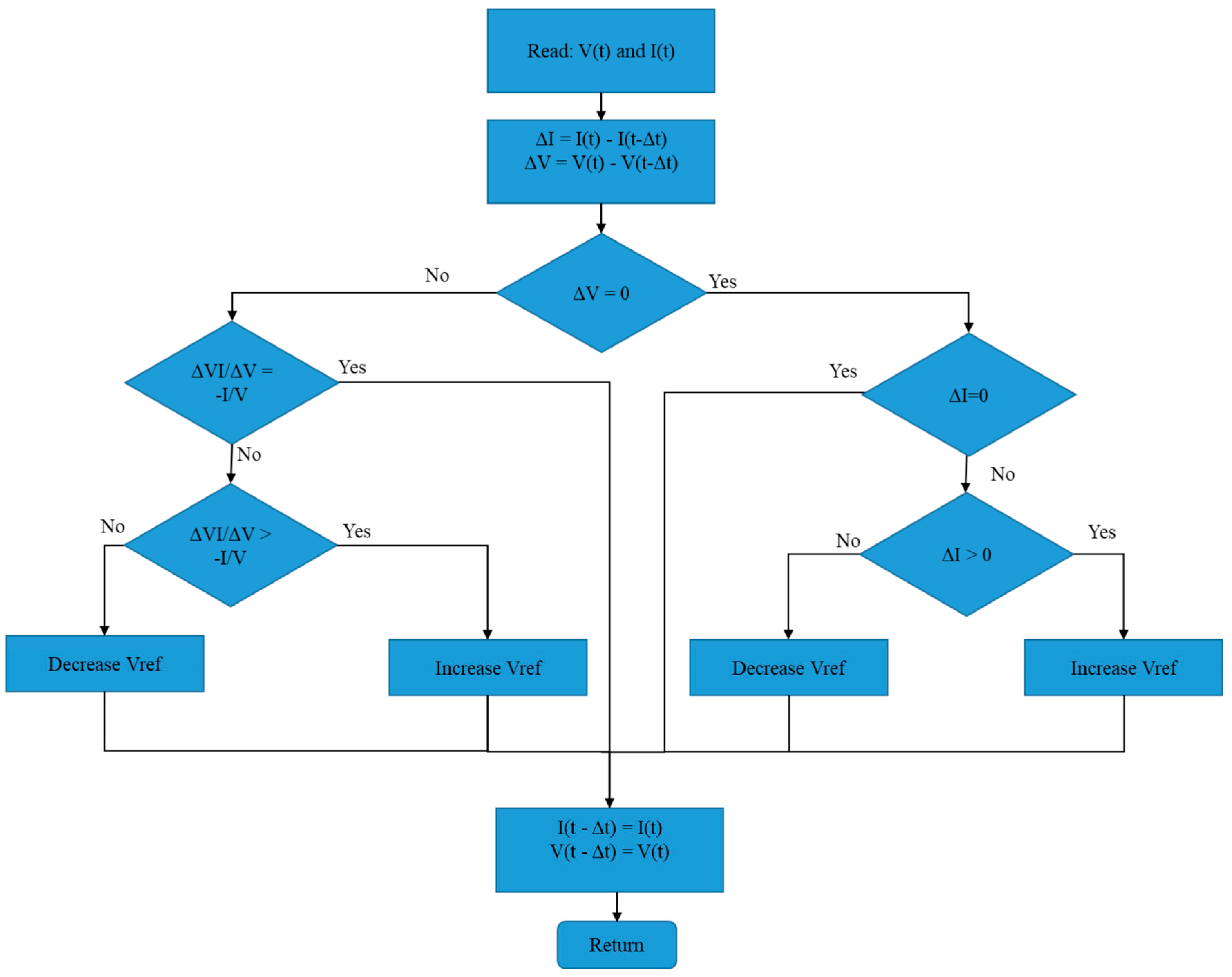

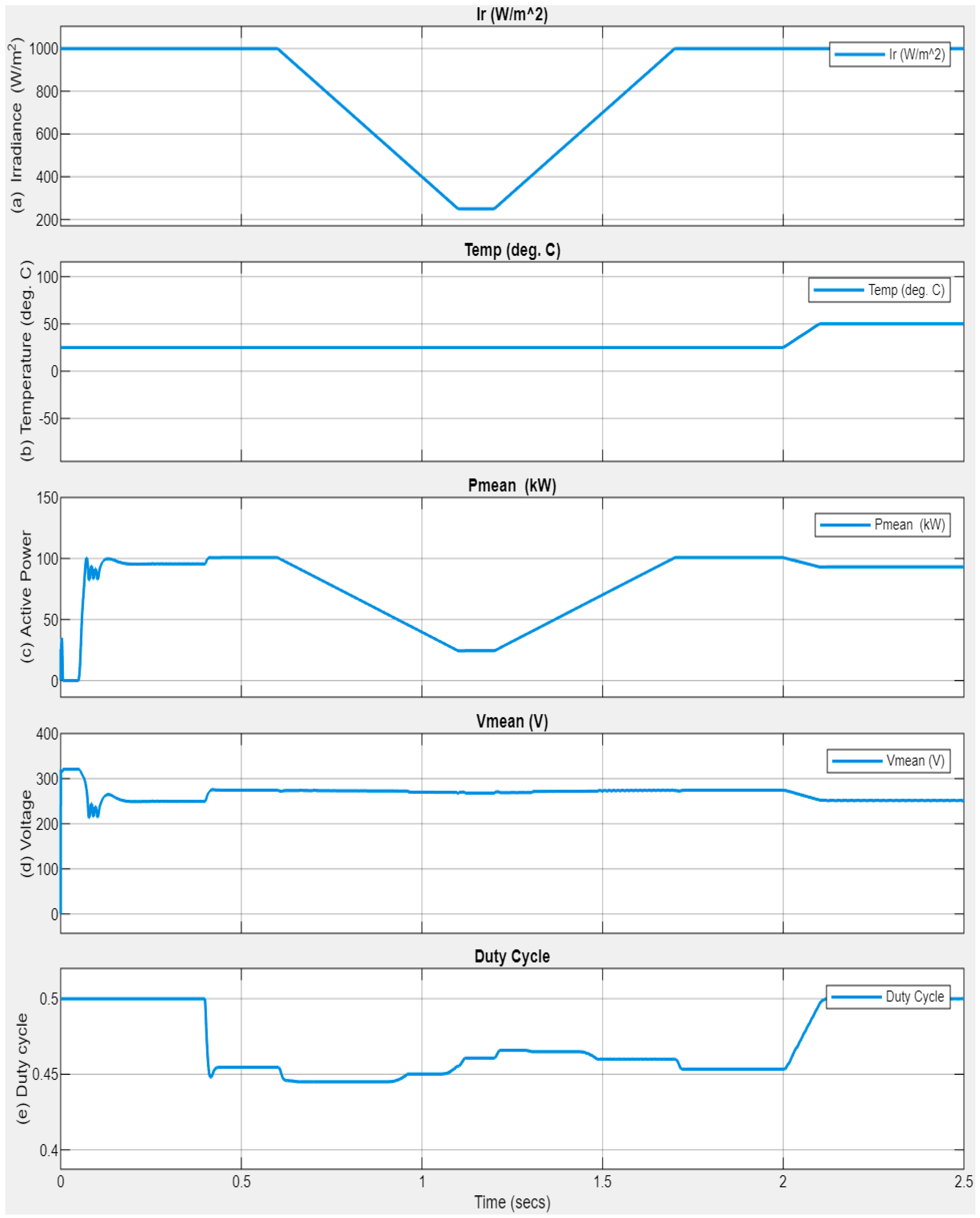

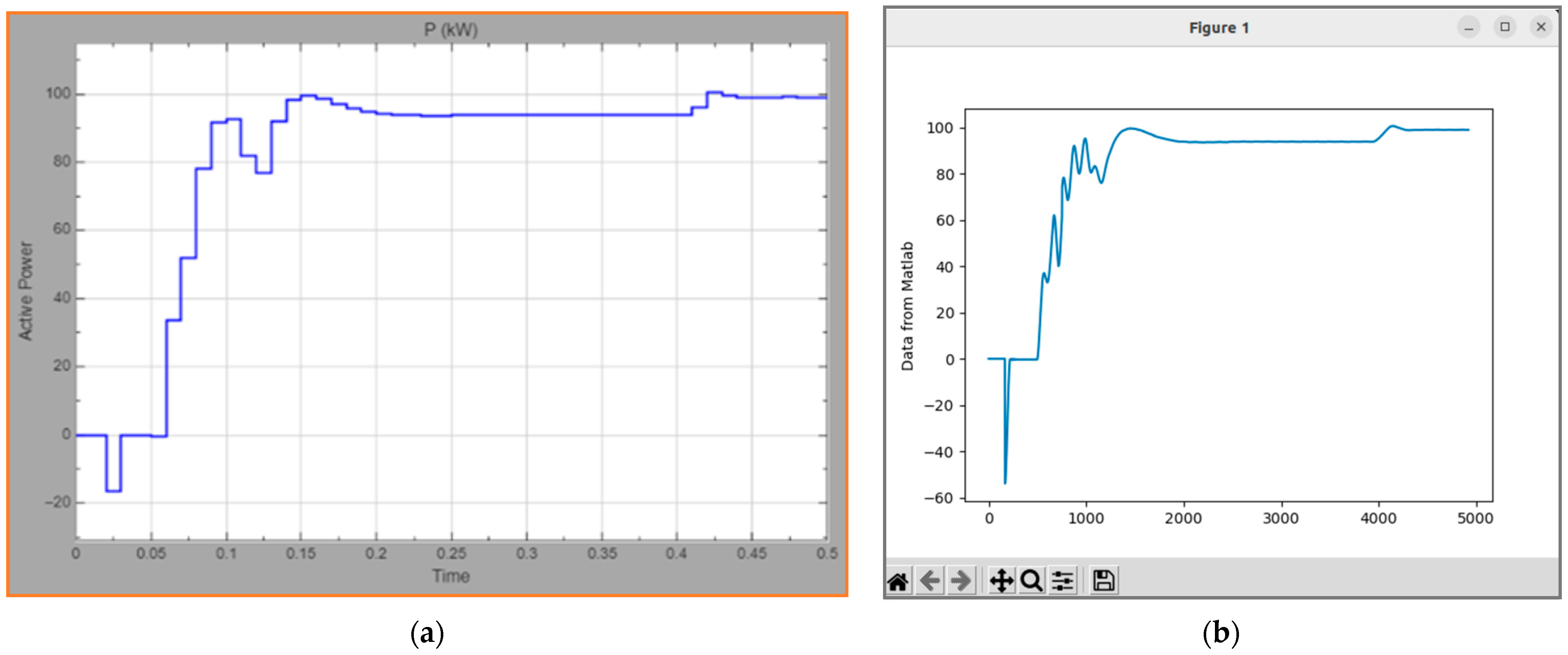

3.1. Simulink PV Plant Simulation with TCP Client Implementation

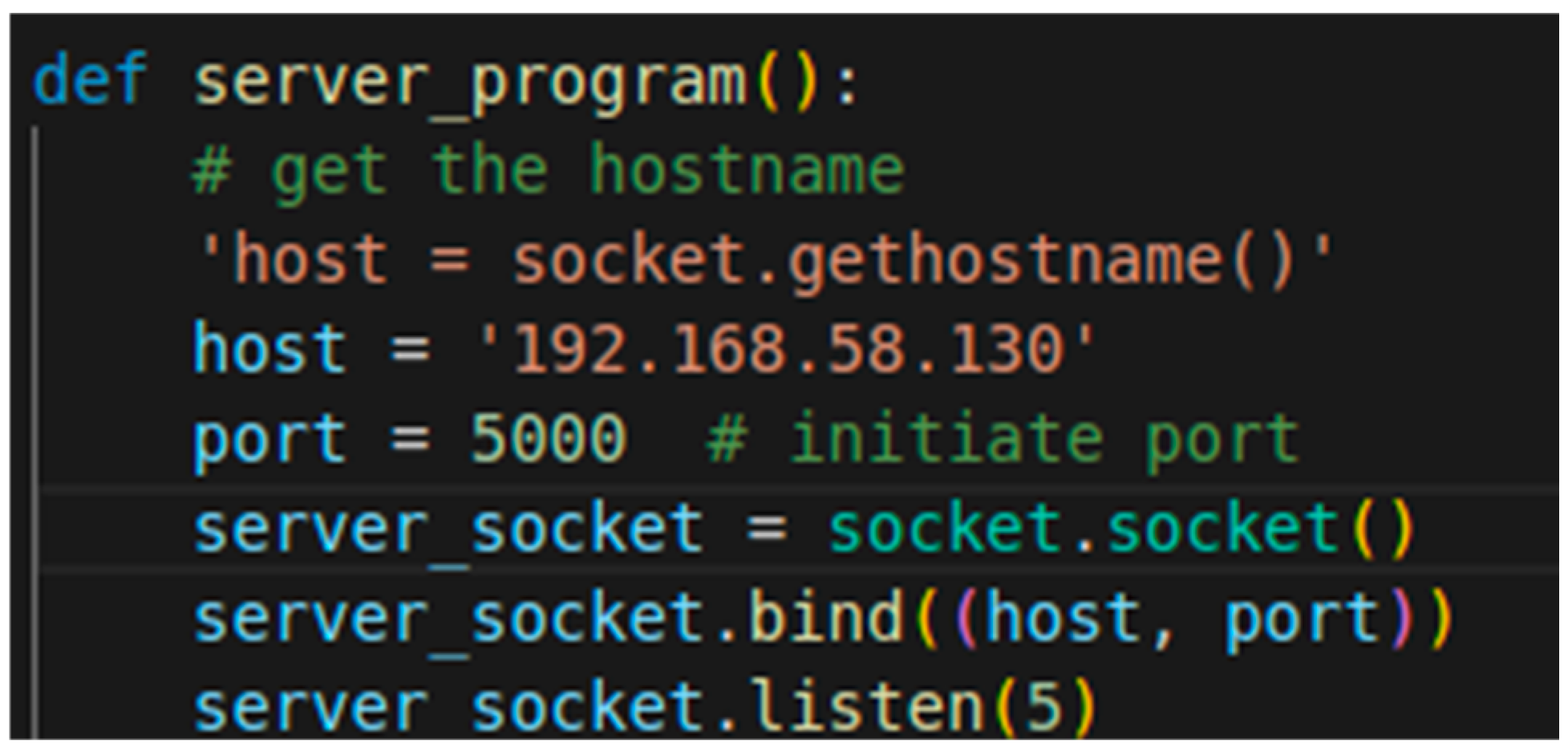

3.2. Testing Simulink Communication with a TCP Server Implemented Using a Python Script

4. Testing and Implementation

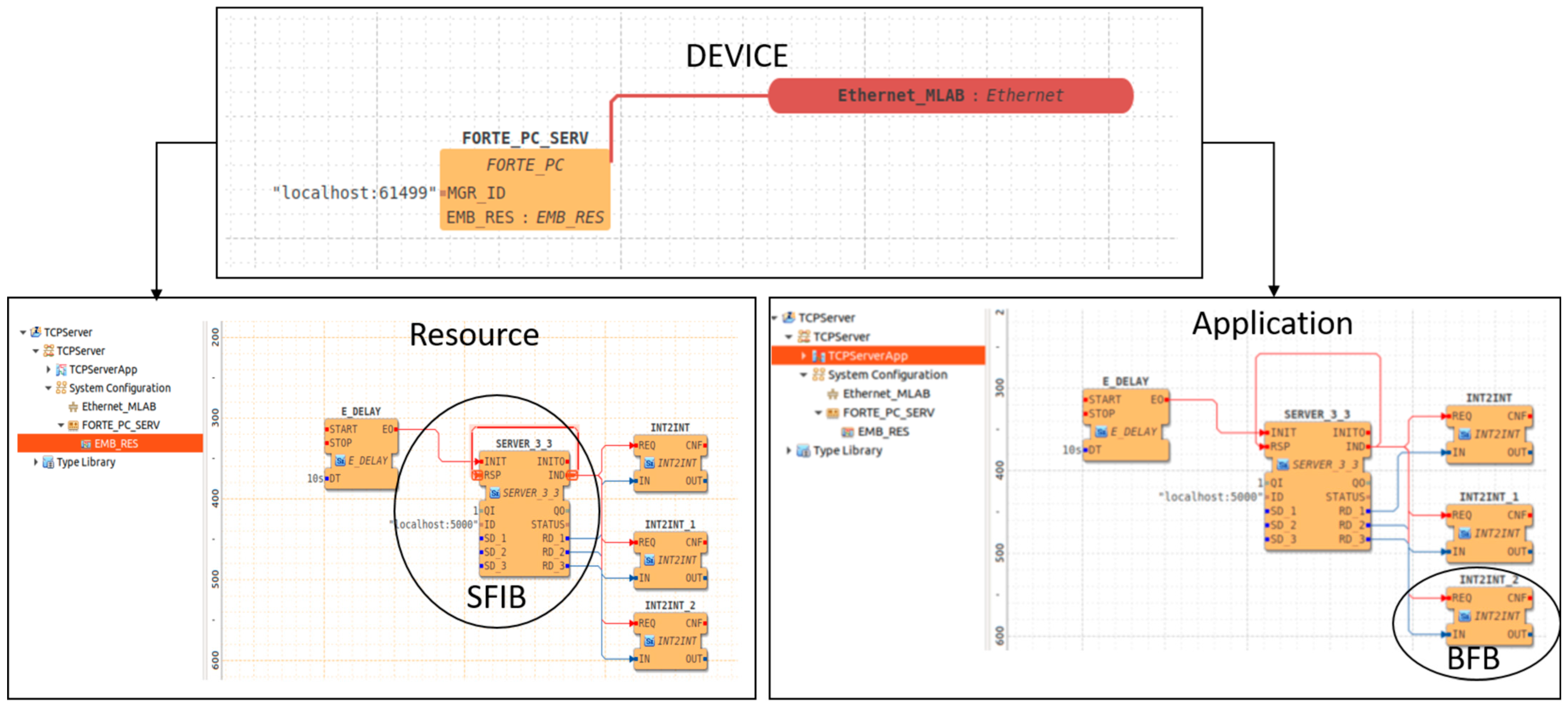

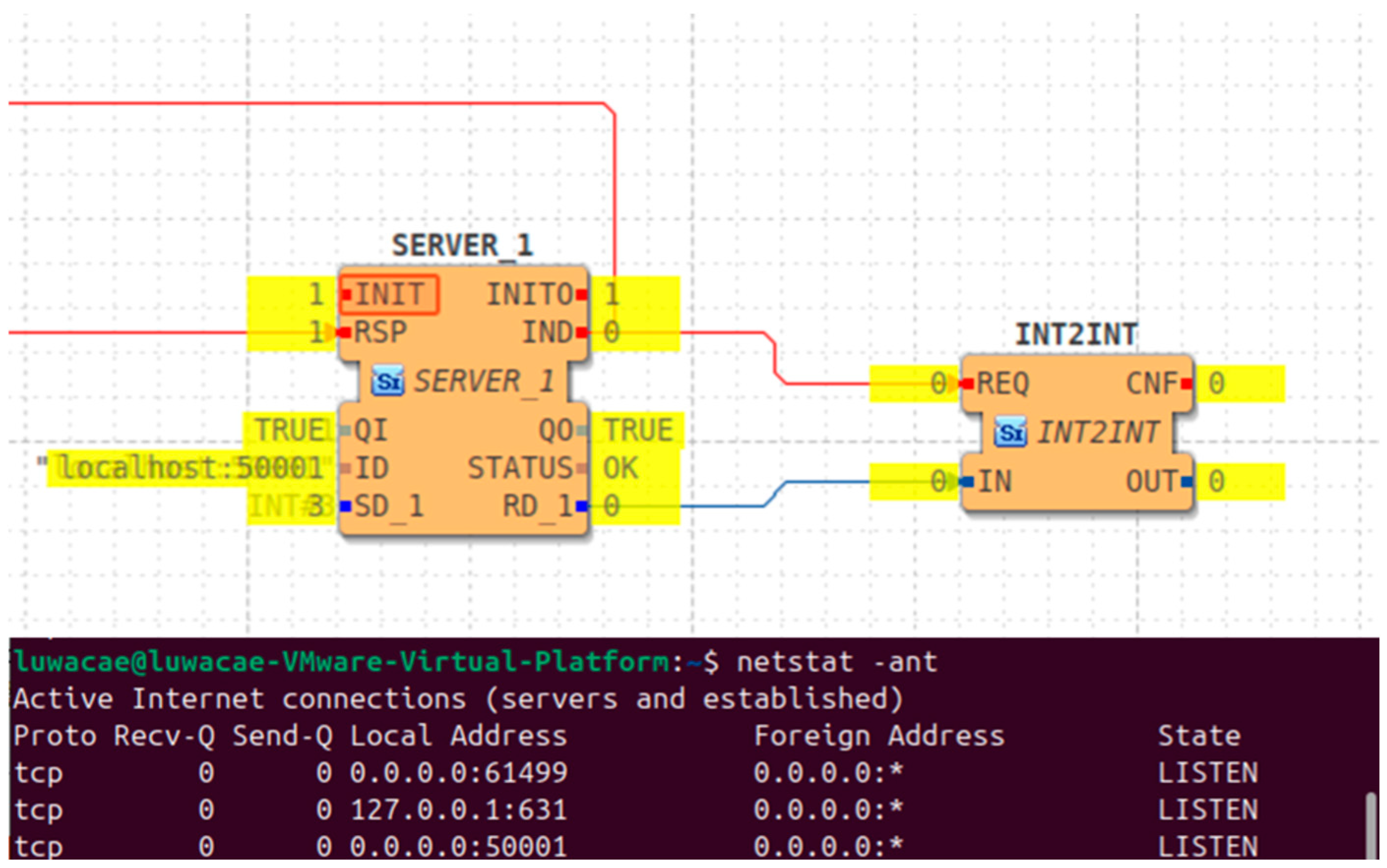

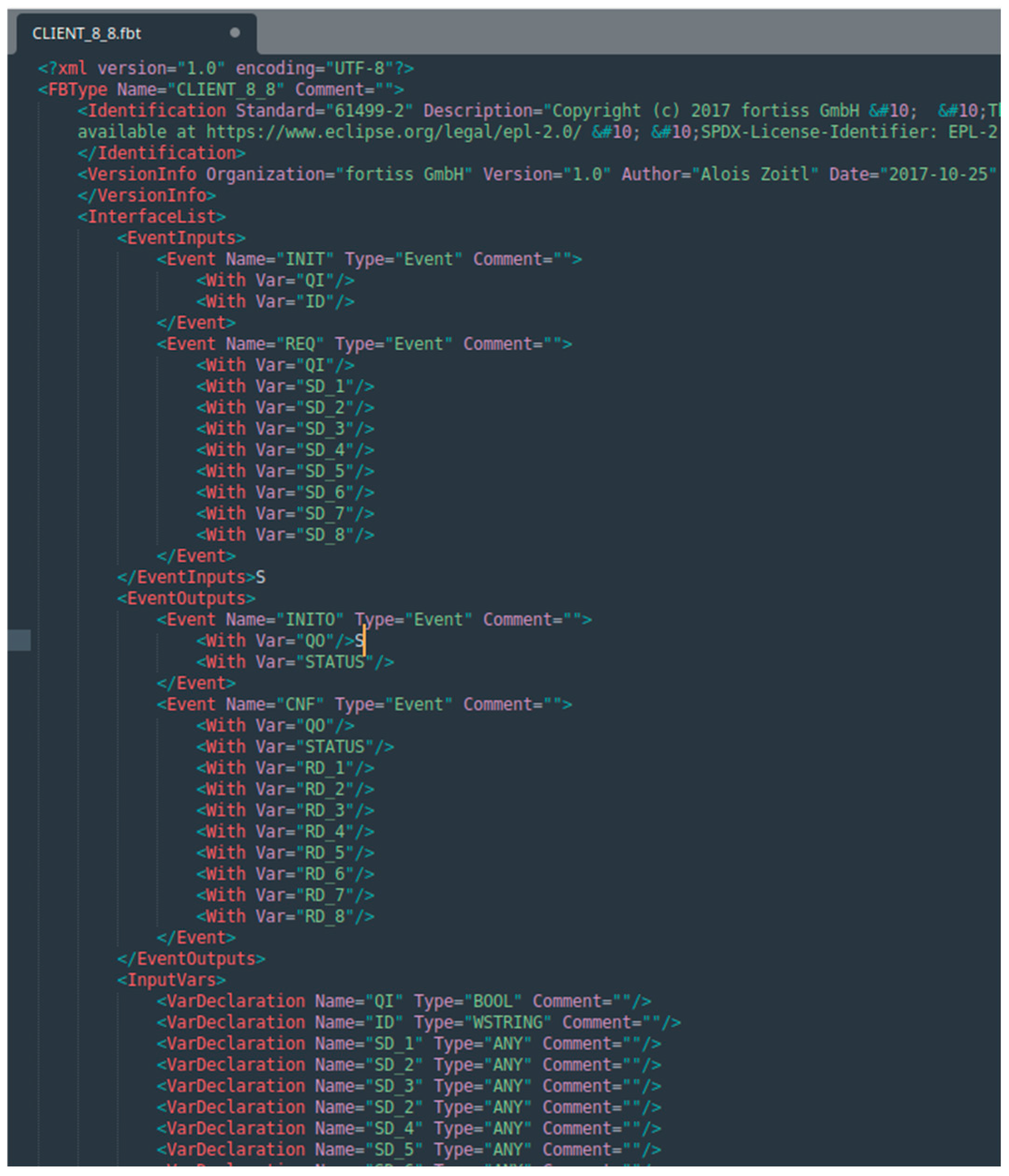

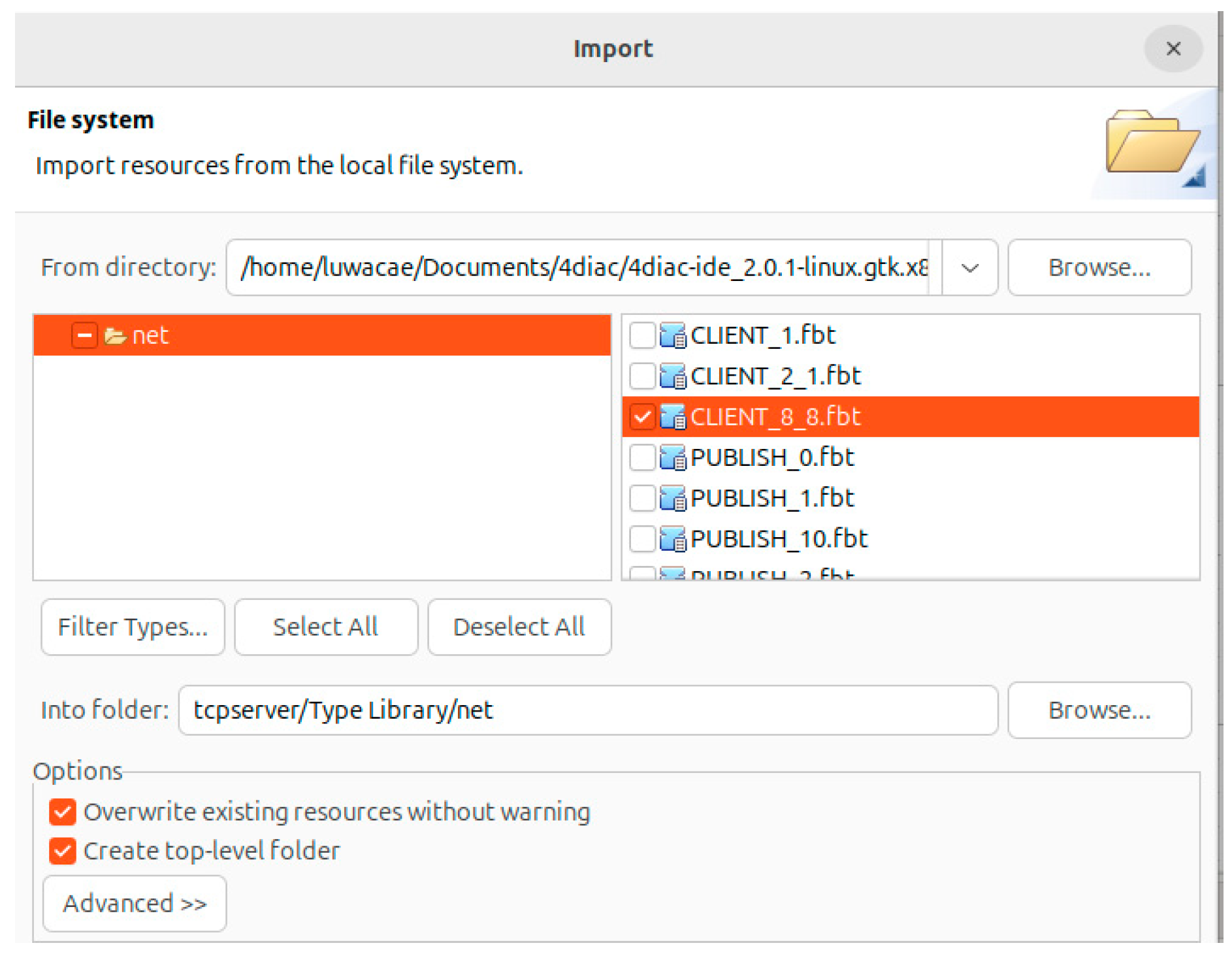

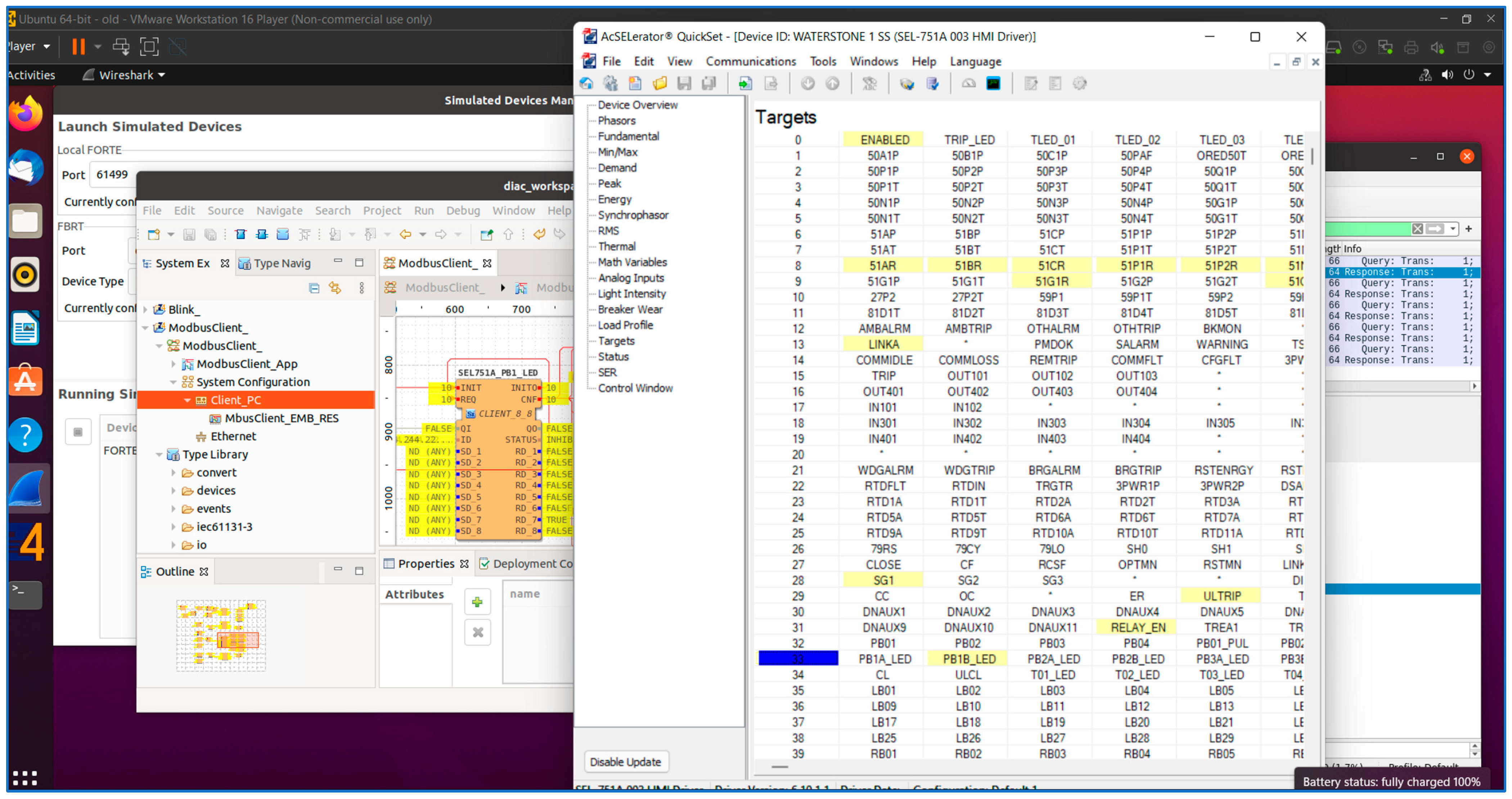

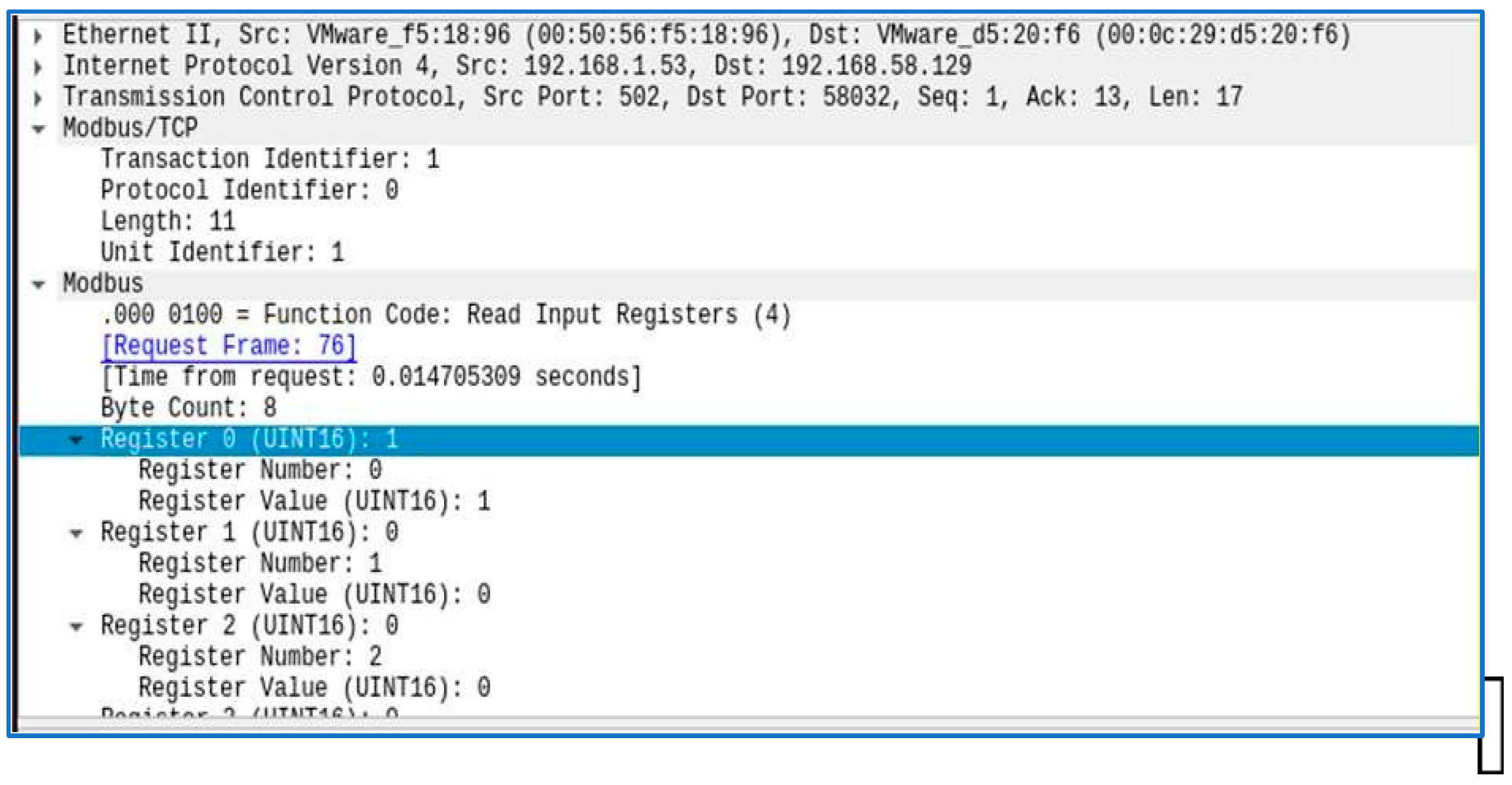

4.1. Testing Communication Protocols on 4DIAC

4.2. Implementing a Low-Cost Gateway Application

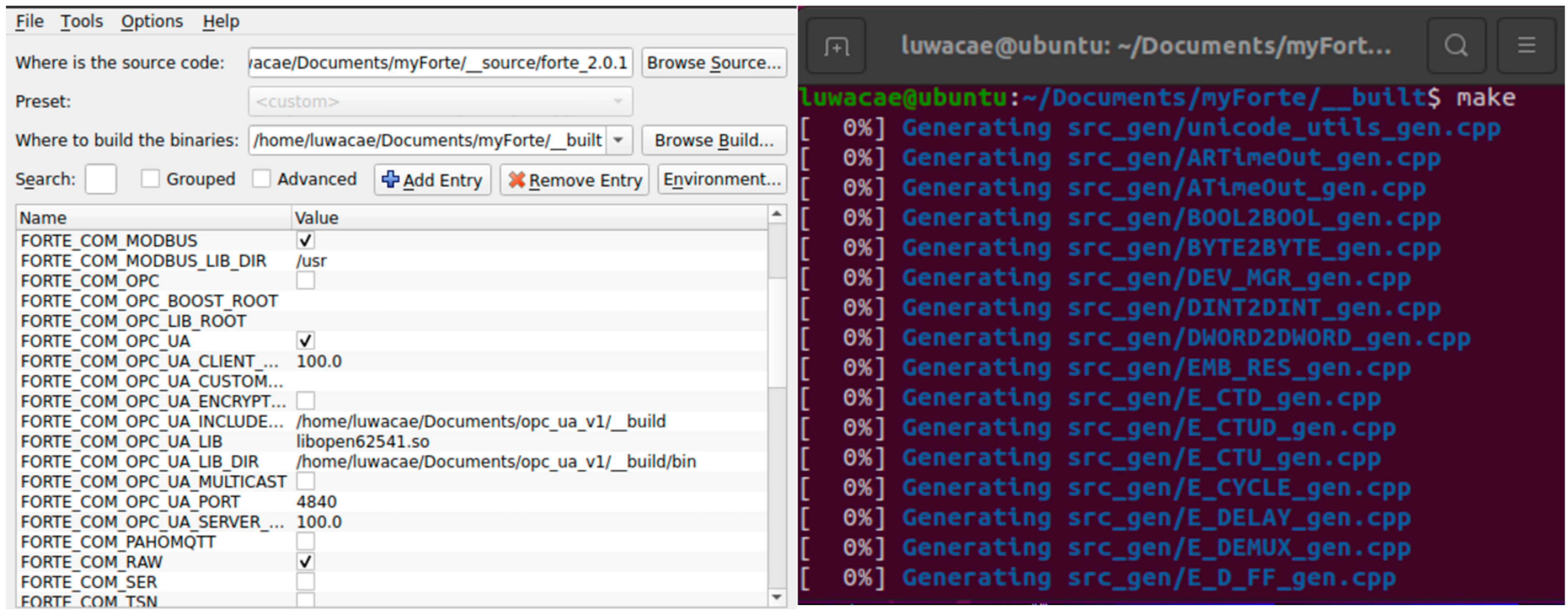

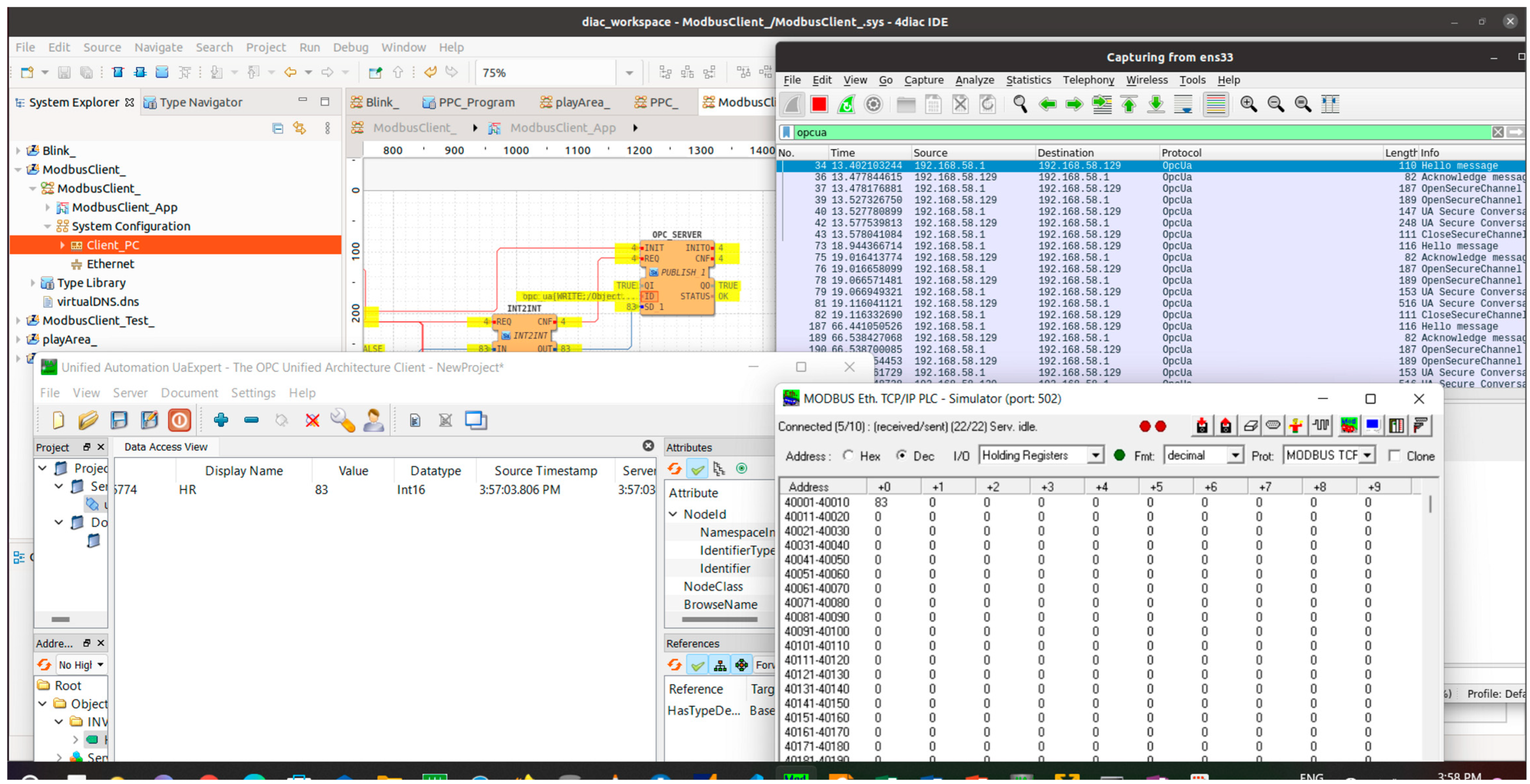

4.2.1. Using 4DIAC—OPC UA

4.2.2. IEC 61850-USING OpenPLC61850

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 4Diac | 4diac™ IDE is an IEC 61499. Compliant Development Environment |

| AC | Alternating Current |

| DER | Distributed Energy Resource |

| ECC | Execution Control Chart |

| EPL | Eclipse Public License |

| FORTE | 4Diac runtime |

| GOOSE | Generic Object-Oriented Substation Event |

| IC | Incremental conductance |

| IDE | Integrated Development Environment |

| IEC 61131-3 | IEC61131 is an IEC standard for programmable controllers |

| IEC 61499 | IEC61499 is an IEC Standard that provides a generic model for distributed systems |

| IEC 62541 | An IEC standard that defines the Information Model of the OPC Unified Architecture |

| IED | Intelligent Electronic Device |

| IGBT | Insulated-Gate Bipolar Transistor |

| iLN | Intelligent Logical Node |

| IR | Integral Regulator |

| MMS | Manufacture Message Specification |

| Modbus | Modbus is an open, client-server application protocol for industrial communication. |

| MPPT | Maximum Power Point Tracking |

| OPCUA | Open Platform Communications Unified Architecture |

| PLC | Programmable Logic Controller |

| PO | Perturb & Observe |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| RBAC | Role-based access control |

| SCADA | Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition |

| SEL 751A | Feeder Protection Relay is for industrial and utility feeder protection |

| SFIB | Service Interface Function Block |

| SV | Sampled Values |

| TCP/IP | Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol, |

| TLS | Transport Layer Security |

| TR | Technical Report |

| uint | Unsigned Integer |

| VM | Virtual Machine |

| XML | Extensible Markup Language |

References

- Spalding-Fecher, R.; Senatla, M.; Yamba, F.; Lukwesa, B.; Himunzowa, G.; Heaps, C.; Chapman, A.; Mahumane, G.; Tembo, B.; Nyambe, I. Electricity supply and demand scenarios for the Southern African power pool. Energy Policy 2017, 101, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Srinivasan, S.; Indumathi, G.; Dzitac, S. A Communication Viewpoints of Distributed Energy Resource. In Proceedings of the International Workshop Soft Computing Applications, Arad, Romania, 24–26 August 2016; pp. 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 61131-3:2025; Programmable Controllers—Part 3: Programming Languages (4th ed.). International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

- Vyatkin, V. IEC 61499 as enabler of distributed and intelligent automation: State-of-the-art review. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2011, 7, 768–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, G.; Brennan, R.W. Towards IEC 61499-based distributed intelligent automation: A literature review. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 17, 2295–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyatkin, V. IEC 61499 Function Blocks for Embedded and Distributed Control Systems Design; ISA: Gurugram, India, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; Shi, D.; Duan, X. Standard function blocks for flexible IED in IEC 61850-based substation automation. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2010, 26, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavadini, F.A.; Montalbano, G.; Kollegger, G.; Mayer, H.; Vytakin, V. IEC-61499 distributed automation for the next generation of manufacturing systems. In The Digital Shopfloor-Industrial Automation in the Industry 4.0 Era; Soldatos, J., Lazaro, O., Cavadini, F., Eds.; River Publishers: Gistrup, Denmark, 2022; pp. 103–127. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, J.H.; Strasser, T.; Valentini, A.; Vyatkin, V.; Zoitl, A. The IEC 61499 function block standard: Overview of the second edition. ISA Autom. Week 2012, 6, 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Thramboulidis, K. IEC 61499 in factory automation. In Advances in Computer, Information, and Systems Sciences, and Engineering, Proceedings of the IETA 05, TENE 05 and EIAE 05; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 115–124. [Google Scholar]

- Thramboulidis, K. IEC 61499 vs. 61131: A comparison based on misperceptions. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1303.4761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanelli, S.; Foglia, P.; Prete, C.A. Integration of existing IEC 61131-3 systems in an IEC 61499 distributed solution. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE 17th International Conference on Emerging Technologies & Factory Automation, Krakow, Poland, 17–21 September 2012; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andren, F.; Strasser, T.; Zoitl, A.; Hegny, I. A reconfigurable communication gateway for distributed embedded control systems. In Proceedings of the IECON 2012-38th Annual Conference on IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Montreal, QC, Canada, 25–28 October 2012; pp. 3720–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, T.; Stifter, M.; Andrén, F.; de Castro, D.B.; Hribernik, W. Applying open standards and open source software for smart grid applications: Simulation of distributed intelligent control of power systems. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting, Detroit, MI, USA, 24–28 July 2011; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, T.; Andrén, F.; Vyatkin, V.; Zhabelova, G.; Yang, C.-W. Towards an IEC 61499 compliance profile for smart grids review and analysis of possibilities. In Proceedings of the IECON 2012-38th Annual Conference on IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Montreal, QC, Canada, 25–28 October 2012; pp. 3750–3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlad, V.; Popa, C.D.; Turcu, C.O.; Buzduga, C. A solution for applying IEC 61499 function blocks in the development of substation automation systems. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1508.06435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, E.M.; Carrillo, L.R.G.; Salazar, L.A.C. Structuring Cyber-Physical Systems for Distributed Control with IEC 61499 Standard. IEEE Lat. Am. Trans. 2023, 21, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sysel, M. Matlab/Simulink TCP/IP communication. In Proceedings of the 15th WSEAS International Conference on Computers, Corfu Island, Greece, 15–17 July 2011; pp. 71–75. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy, S.; Mohlwini, E.X. Voltage stability index method for optimal placement of capacitor banks in a radial network using real-time digital simulator. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on the Domestic Use of Energy (DUE), Cape Town, South Africa, 30–31 March 2016; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MATLAB Help Center. Simscape Electrical. Available online: https://ch.mathworks.com/help/sps/ug/detailed-model-of-a-100kw-grid-connected-pv-array.html (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Dighore, V.; Welankiwar, A. Design and Simulation of 100 MW Photovoltaic Power Plant Using Matlab Simulink. 2021. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351733228_Design_and_Simulation_of_100_MW_Photovoltaic_Power_Plant_Using_Matlab_Simulink (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Zoitl, A.; Strasser, T.; Ebenhofer, G. Developing modular reusable IEC 61499 control applications with 4DIAC. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 11th International Conference on Industrial Informatics (INDIN), Bochum, Germany, 29–31 July 2013; pp. 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seilonen, I.; Vyatkin, V.; Atmojo, U.D. OPC UA information model and a wrapper for IEC 61499 runtimes. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 17th International Conference on Industrial Informatics (INDIN), Helsinki, Finland, 22–25 July 2019; pp. 1008–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 61850-7-420; Communication Networks and Systems for Power Utility Automation—Part 7-420: Basic Communication Structure—Distributed Energy Resources Logical Nodes. IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. Available online: https://cdn.standards.iteh.ai/samples/13405/92c4628f823549998e9f9d88013e5b37/IEC-61850-7-420-2009.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- IEC TR 61850-90-11; Part 90-11: Methodologies for Modelling of Logics for IEC 61850 Based Applications. IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. Available online: https://webstore.iec.ch/en/publication/32080 (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Hara, M.; Kriger, C. Implementation of an IEC 61850-Based Metering Device Using Open-Source Software. Univers. J. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2021, 8, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roomi, M.M.; Ong, W.S.; Mashima, D.; Hussain, S.S. OpenPLC61850: An IEC 61850 MMS compatible open source PLC for smart grid research. SoftwareX 2022, 17, 100917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, T.R.; Buratto, M.; De Souza, F.M.; Rodrigues, T.V. OpenPLC: An open source alternative to automation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference (GHTC 2014), San Jose, CA, USA, 10–13 October 2014; pp. 585–589. [Google Scholar]

| Criteria | Evaluation of IEC 61499 to Support Criteria | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Standardization | Standardized models using function blocks. | DCS |

| Modular, Portable, and Reusable FBs | Supports the use of modular, reusable, and portable FBs | PLCs, DCS, IoT |

| Interoperability | Limited. runtime interoperability is not detailed | Multi-vendor integration |

| Scalability | Supports both small and large applications | PLC and DCS |

| Tools | Limited—both open-source and commercial | PLC and DCS |

| Certification | Lacks a strong certification ecosystem. |

| Time | Irradiance | Temp |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1000 | 25 |

| 1.1 | 250 | 25 |

| 1.2 | 250 | 25 |

| 1.7 | 1000 | 25 |

| 2.1 | 1000 | 50 |

| Device Name | Device Type | DI | DO | AI | AO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASE | TCP | %IX100.0-to-%IX100.7 | %DX100.0-to-%QX101.7 | %IW100-to-%IW11 | %QW100 to %QW107 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luwaca, E.; Krishnamurthy, S. Realization of a Gateway Device for Photovoltaic Application Using Open-Source Tools in a Virtualized Environment. Computers 2025, 14, 524. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120524

Luwaca E, Krishnamurthy S. Realization of a Gateway Device for Photovoltaic Application Using Open-Source Tools in a Virtualized Environment. Computers. 2025; 14(12):524. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120524

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuwaca, Emmanuel, and Senthil Krishnamurthy. 2025. "Realization of a Gateway Device for Photovoltaic Application Using Open-Source Tools in a Virtualized Environment" Computers 14, no. 12: 524. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120524

APA StyleLuwaca, E., & Krishnamurthy, S. (2025). Realization of a Gateway Device for Photovoltaic Application Using Open-Source Tools in a Virtualized Environment. Computers, 14(12), 524. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120524