Abstract

This paper addresses the critical challenge of energy management for autonomous robots in the context of large-scale photovoltaic parks. The dynamic and vast nature of these environments, characterized by dense, structured rows of solar panels, introduces unique complexities, including uneven terrain, varied operational demands, and the need for equitable resource allocation among diverse robot fleets. The presented framework adapts and significantly extends the Affinity Propagation algorithm for strategic charging station placement within photovoltaic parks. The key contributions include: (1) a multi-attribute grid-based environment model that quantifies terrain difficulty and panel-specific obstacles; (2) an extended multi-factor scoring function that incorporates penalties for terrain inaccessibility and proximity to sensitive photovoltaic infrastructure; (3) a sophisticated, energy-aware consumption model that accounts for terrain friction, slope, and rolling resistance; and (4) a novel multi-agent fairness constraint that ensures equitable access to charging resources across heterogeneous robot sub-fleets. Through extensive simulations on synthesized photovoltaic park environments, it is demonstrated that the enhanced algorithm not only significantly reduces travel distance and energy consumption but also promotes a fairer, more efficient operational ecosystem, paving the way for scalable and sustainable robotic maintenance and inspection.

1. Introduction

The global energy sector is undergoing a profound transformation driven by the widespread adoption of renewable energy sources, with photovoltaic (PV) parks playing a central role [1,2,3,4,5]. The sheer scale and complexity of these installations, which can span vast areas, have created a significant demand for autonomous solutions to tasks such as inspection, cleaning, maintenance, and vegetation control. The integration of robotic systems, including Unmanned Ground Vehicles (UGVs) and Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), is central to this evolution [6]. However, a significant bottleneck to the large-scale adoption of these autonomous fleets is effective energy management [7,8]. Inefficient strategies, particularly the sub-optimal placement of charging stations, lead to increased robot downtime, reduced operational efficiency, and higher overall costs, inhibiting the full potential of these technologies.

The PV park environment presents a dynamic, unstructured, and complex setting that introduces a new set of challenges to the problem of optimal charging station placement [9,10,11,12]. A PV park is not a clean, grid-like space. Instead, it is characterized by: (a) uneven and deformable terrain, including varying slopes, soil types, and ruggedness, which fundamentally alters UGV energy consumption and mobility; (b) static and dynamic obstacles, ranging from fixed electrical infrastructure like inverters and transformers to transient elements like overgrown vegetation or recently installed equipment; and (c) the requirement to manage diverse, multi-robot fleets with heterogeneous energy needs and task assignments, such as a UGV fleet for cleaning and a UAV fleet for aerial inspection. Furthermore, the operational hotspots for robots are not static but shift with scheduled cleaning cycles or targeted inspection missions, requiring a solution that can adapt over time.

This paper presents a novel, holistic framework that utilizes the Affinity Propagation (AP) [13] algorithm to address the intricate problem of charging station placement in PV parks. The contributions of this work are multifaceted and build upon a proven algorithmic foundation while fundamentally redefining the problem to suit the unique domain of renewable energy management. The core contributions are as follows:

- A novel, context-aware extension of the Affinity Propagation algorithm for strategic charging station placement in PV parks, which addresses the dynamic nature of the robot’s activity inside the PV parks.

- A multi-attribute grid-based environment model that moves beyond simple traversability to incorporate quantitative data on terrain passability, slope, and obstacles.

- A refined, multi-factor scoring function that penalizes potential charging locations based on their terrain difficulty, proximity to panels, and other domain-specific constraints.

- A detailed, extended energy consumption model that captures the real-world costs of traversing varied terrain by accounting for slope, friction, and rolling resistance.

- A multi-agent fairness constraint that quantifies and optimizes for equitable access to charging resources, preventing a sub-fleet from being systematically disadvantaged.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a comprehensive review of the relevant literature on robotics in PV parks, energy management, and multi-agent fairness. Section 3 details the proposed system, including the new environment model and the adapted scoring function. Section 4 presents the algorithmic enhancements, focusing on the fairness constraint and the extended energy model. Section 5 describes the simulation setup and presents a quantitative analysis of the results. Section 6 provides a detailed discussion of the findings and their implications. Finally, Section 7 concludes the paper and outlines promising avenues for future research.

2. Related Work

2.1. UGV and UAV Navigation and Path Planning in Photovoltaic Parks

The problem of path planning for autonomous systems is fundamental to robotics, typically focused on minimizing travel costs between two points while avoiding obstacles [14,15,16,17,18]. While static solutions provide fixed routes, dynamic algorithms adapt to real-time changes, leading to enhanced operational efficiency. In the context of large-scale PV parks, the challenge is often a “coverage path planning” (CPP) problem, where the robot must systematically traverse an entire area to perform a task such as cleaning, inspection, or vegetation control [19].

Environment modeling for path planning is a critical precursor to effective navigation. Grid-based maps are a widely used approach due to their intuitive nature and high adaptability [20,21]. In this method, the environment is discretized into uniformly spaced cells, each with a state indicating whether it is passable or impassable. While this model is computationally efficient, its primary limitation lies in the trade-off between precision and computational load; excessively large grids may miss important nuances, while small grids can be computationally prohibitive. An alternative is the use of topological maps, which represent the environment as a graph of nodes and traversable edges [22]. While this approach is suitable for large parks, it often lacks the granular detail required for fine-grained decisions about charging station placement or terrain-specific navigation.

To overcome the limitations of simple 2D grid maps, researchers have developed multi-attribute maps, sometimes referred to as “2.5D” maps. These maps enrich each grid cell with additional, non-binary information that captures the complexity of the off-road environment. Factors such as slope, ruggedness, and soil conditions can be encoded into each cell, creating a “passability map” that can serve as a foundational layer for more sophisticated path planning [23]. The creation of such maps can be a complex process, often requiring the fusion of data from various sensors and platforms, including UAVs for wide-area surveys and UGVs for localized ground-truth data collection.

2.2. Energy Management and Station Placement

The strategic placement of energy stations is a nascent but critical field of research, especially with the proliferation of electric vehicles and autonomous systems [24,25]. While a significant body of work exists on deploying charging stations in urban landscapes for cars, the principles often differ when applied to controlled or semi-controlled environments.

A separate but related research area is energy-aware path planning for off-road robots. Traditional path planning algorithms typically seek to minimize travel distance, but on uneven terrain [26,27], the shortest path may not be the most energy-efficient. A path with a gentle slope and stable soil may be longer in distance but consume less energy than a shorter path that requires climbing a steep, rugged hill. This highlights the need for a more nuanced energy model that goes beyond simple distance traveled. The development of such models is challenging, as it requires an understanding of how terrain characteristics, such as slope and friction, influence a robot’s power consumption. Research has shown that rolling resistance, a primary source of energy loss on soft or uneven surfaces, is influenced by factors like the vehicle’s shape, weight distribution, and the properties of the ground itself. Obtaining accurate, real-world energy-cost maps for practical applications is a significant hurdle, as it often requires extensive data collection with both aerial and ground robots.

2.3. Multi-Agent Coordination and Fairness

To meet the demands of modern PV park management, the industry is increasingly moving toward multi-robot systems [28]. The use of coordinated fleets of UGVs and UAVs can significantly improve efficiency, scalability, and task completion times, especially on large-scale PV parks. However, this shift introduces new challenges in coordination, task allocation, and resource management.

A critical, yet often overlooked, consideration in multi-agent systems is fairness. In a system designed purely for global efficiency (e.g., minimizing total travel time for the entire fleet), some individual agents or sub-fleets may be systematically disadvantaged. For example, a group of UGVs assigned to a remote section of a large park might consistently face longer travel distances to a charging station, while another group operating near a station enjoys near-constant uptime. This can lead to what is known as the “tragedy of the commons” in resource management, where a focus on the aggregate can lead to sub-optimal performance for individuals, creating system instability and operational bottlenecks.

To address this, quantitative measures of fairness are required. One such metric, derived from behavioral economics, is the Coefficient of Variation (CV) of agents’ utilities or, in our context, their travel distances to resources. The CV, defined as the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean, is a widely used metric for fairness in resource allocation as it provides a normalized, scale-invariant measure of dispersion. This allows for a fair comparison of equity across sub-fleets that may have different absolute mean travel distances. By incorporating a fairness objective into the overall optimization problem, a system can be designed to not only be efficient but also to ensure a more equitable distribution of resources, leading to greater overall system robustness and stability.

2.4. Charging Station Placement in Related Domains

While the specific problem of optimal charging station placement within photovoltaic parks is an emerging research area, a number of works from related domains offer valuable insights and methodologies. Much of the prevailing research focuses on urban landscapes for electric vehicles (EVs) [24,25]. Some of these studies have formulated the placement of charging stations as an optimization problem, considering factors like station density, accessibility, and regional cost variations to minimize construction costs. Other work has applied reinforcement learning strategies to identify optimal locations by minimizing the energy required for EVs to reach a charging station. Another approach leverages real-world charging data to identify patterns and causal relationships between charging demand and factors such as proximity to amenities, EV registration density, and adjacency to high-traffic routes.

This paper advances the field by uniquely addressing the specific challenges of a photovoltaic park, an environment that sits at a complex intersection between unstructured natural terrain and a structured, human-made infrastructure. While existing literature provides foundational concepts for grid-based modeling and optimization, they typically fall short in their ability to holistically account for the unique, multi-faceted complexities of a PV park. Unlike the simplified models used for urban or indoor environments, our approach explicitly incorporates a detailed multi-attribute environment model that accounts for terrain passability and a refined energy model that penalizes movement over difficult terrain and slopes, a critical factor for off-road UGVs and UAVs. Furthermore, by introducing a multi-agent fairness constraint, our framework directly tackles a problem often overlooked in traditional efficiency-focused placement algorithms, ensuring a more stable and scalable solution for heterogeneous robotic fleets. This integration of a sophisticated environment model, a nuanced energy consumption metric, and a fairness constraint represents a significant and necessary departure from prior work, providing a more practical and robust solution for the unique demands of renewable energy infrastructure.

3. Implementation

3.1. Environment Definition: The Multi-Attribute PV Park Grid

A grid-based representation of the environment is adopted for its computational efficiency and ease of implementation. However, unlike a simplistic grid, the proposed model for a PV park is a rich, multi-attribute representation. Each cell, denoted by its Cartesian coordinates is not a binary value of accessible or inaccessible but a complex data point that captures the multifaceted nature of the environment.

The environment is formally defined as a matrix of these cells, where each cell is characterized by the following attributes:

- TrafficCount : This value represents the historical or predicted robot traversal count for a specific cell, indicating areas of high operational demand. In the PV park context, these “hotspots” are dynamic and shift based on the maintenance schedule (e.g., a planned inspection route or a cleaning cycle) and the need for localized repairs.

- TerrainDifficulty : This is a continuous value (e.g., on a scale of 0 to 10) that quantifies the traversability of the terrain in that cell. This attribute would be derived from a “passability map” that fuses data from various sources, including slope, soil type, and ruggedness. A higher value indicates more difficult terrain, such as rocky ground or areas with dense vegetation. This value is paramount for energy-aware path planning, as traversing a cell with a high TerrainDifficulty incurs a greater energy penalty.

- ObstaclePenalty : This value represents the presence of static obstacles (e.g., inverters, transformers, control rooms) and dynamic ones (e.g., maintenance crew vehicles, temporary equipment) that a robot must avoid. This can be a binary value (1 for an obstacle, 0 for clear) or a continuous one to represent varying levels of obstruction.

The acquisition of this rich environmental data is a key practical consideration. A symbiotic approach involving both Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) and UGVs is envisioned. UAVs can efficiently survey large areas to create a base map with high-level terrain and obstacle data, while UGVs can collect ground-truth data on soil conditions, moisture levels, and localized terrain characteristics to enrich the grid cells.

3.2. Dynamic Hotspot Identification via Affinity Propagation

The first stage of the proposed methodology is to identify areas of high robot activity, which correspond to the clusters where charging stations should be placed. The Affinity Propagation (AP) algorithm is well-suited for this task due to its ability to find “exemplars” or representative data points from a set of input data without requiring a predefined number of clusters.

The input is a PV park grid, with each cell’s TrafficCount serving as the primary metric. The algorithm identifies clusters of cells with similar traversal patterns. The output is a set of distinct sub-areas, each with a designated “exemplar” cell that best represents the traffic characteristics of its cluster. This process accounts for the dynamic nature of PV park operations, where operational hotspots are not fixed. The algorithm would need to be re-run periodically to adapt to changing mission parameters (e.g., a scheduled cleaning cycle versus a post-storm inspection) or new operational plans, a necessity in the real-world context.

A crucial adaptation to the standard AP algorithm is the recalibration of the self-similarity values, which pivotally determines the number and size of the resulting clusters. The self-similarity for a cell is calculated using the following equation:

In this formula, is the TrafficCount of cell , and is a small positive constant. This modification ensures that cells in high-traffic zones, with their elevated TrafficCount values, are more likely to become exemplars, leading to smaller, more numerous clusters in areas of intense activity. Conversely, cells in lower-traffic areas are less likely to become exemplars and are instead subsumed into larger clusters, ensuring a balance between resource density and coverage across the entire park. The constant is a critical tuning parameter that directly influences the number of exemplars (and thus, charging stations) the algorithm produces. The term acts as a global preference offset; a very small increases this preference, creating more, smaller clusters, while a larger lowers it, resulting in fewer, larger ones. In practice, is selected empirically to balance the trade-off between deployment cost (fewer stations) and operational efficiency (more stations).

3.3. Multi-FactorScoring for Charging Station Placement

Once the clusters have been identified, the next objective is to select the optimal charging station location within each cluster. This is accomplished using an adapted scoring function that considers a multitude of factors critical to a PV park environment. The function for a cell c within a cluster is represented mathematically as:

The weighting constants , , γ and are used to balance the influence of each factor. Each component of the function is defined as follows:

- Traffic Desirability : This factor is an inverted bell curve based on the TrafficCount of cell c. It ensures that the optimal location is a central point within the cluster, easily accessible from the most frequently visited areas.

- Proximity To Obstacles and Panels : This is a new and critical constraint that reflects the unique challenges of a PV park. It imposes a penalty on any potential placement location that is too close to an obstacle, such as a transformer or control room, or to the panel rows themselves. A binary value of 1 can be assigned if the cell is within a predefined buffer zone of a sensitive area, and 0 otherwise. This ensures that the placement does not hinder robot operations, damage infrastructure, or pose a risk to equipment. Placing charging stations too close to panels could also cast shadows, which reduces their energy output.

- Terrain Difficulty : This component, derived directly from the multi-attribute grid, penalizes locations with difficult terrain. Placing a charging station on a steep hill or in a particularly rugged area would be counterproductive, as it would increase the energy cost and potential wear on robots traveling to and from it. This value is a crucial departure from simplified constraints, reflecting a more realistic understanding of robot dynamics in a natural environment.

- Distance From High Traffic Cell : This component remains a crucial part of the function. It is calculated as the Manhattan distance from the cell with the highest TrafficCount within the cluster. It ensures that the chosen charging station location is not isolated from the primary area of robot activity.

By calculating the scores for every cell within a cluster and selecting the one with the highest score, the algorithm ensures that the charging stations are placed in locations that are not only centrally located to service high-traffic areas but are also physically accessible, safe, and viable for long-term use.

4. Algorithmic Enhancements for Field Operations

4.1. Multi-Agent Fairness Constraint

A purely utilitarian approach of optimizing total robot travel distance can lead to an unfair distribution of resources. In a multi-agent system, this could mean a specific sub-fleet of robots performing tasks in a low-traffic area is consistently required to travel a significantly longer distance to charge than a sub-fleet working in a high-traffic area. Such a scenario is not only inequitable but also leads to operational inefficiencies and potential bottlenecks.

To address this, the system’s objective function is enhanced to include a fairness constraint. The goal is no longer just to minimize total travel distance but to minimize a combined objective that balances overall efficiency with equitable resource access. A quantitative measure for fairness, the Coefficient of Variation (CV) of the average travel distances for each sub-fleet, is adopted. This metric was chosen over other indices (such as Jain’s index) because it is particularly well-suited to minimizing large deviations from the average, which directly corresponds to our goal of preventing any single sub-fleet from being ‘systematically disadvantaged’. The CV provides a normalized measure of dispersion around the mean, with a lower value indicating greater fairness. The proposed global objective function to be minimized is defined as:

In this formula, is the total number of UGVs and UAVs, and is the travel distance for robot to its assigned charging station. The term is the Coefficient of Variation of the average travel distances across all distinct robot sub-fleets. The weight is a tuning parameter that allows a system operator to adjust the trade-off between maximizing global efficiency and promoting a fairer distribution of charging resources. A higher value of would prioritize fairness, even at the expense of a slightly increased total travel distance. This enhancement is essential for a stable and scalable multi-agent system, as it prevents any single group of robots from being disproportionately burdened, which aligns with human-centric design principles for autonomous systems.

4.2. Extended Energy Consumption Model

A simplified energy consumption model, which accounts for straight travel, turns, and idle time, is not suitable for the complexities of a PV park environment. Such a model would fail to capture the true energy costs of traversing uneven terrain. The proposed system addresses this by introducing a more sophisticated, energy-aware consumption model that fundamentally redefines the “cost” of movement for a UGV or UAV. The extended model accounts for the energy expended due to slope and terrain friction, recognizing that the path with the shortest distance is not necessarily the path with the lowest energy cost. The extended energy consumption for a robot to travel a path of length is given by:

The first three terms correspond to the energy consumed for straight travel (), turns (), and idle time (). The summation term represents the cell-specific energy costs for the path, where is each individual cell in the path:

- quantifies the energy cost due to terrain friction and rolling resistance in cell . This cost is influenced by the type of soil and its condition (e.g., dry, wet, muddy) and is directly proportional to the friction coefficient of the surface. A path through a wet, muddy section of a field will incur a significantly higher friction energy cost than a path on firm, dry ground.

- accounts for the energy required to traverse a slope. The cost is calculated based on the change in altitude between the current cell and the next, the UGV’s mass, and the force of gravity. Energy is consumed when traveling uphill and can be partially regained when traveling downhill. This model provides a physically grounded representation of energy expenditure that is essential for real-world agricultural scenarios.

This enhanced energy model is not merely a cosmetic change but a critical enhancement that allows the scoring function’s Distance From High Traffic Cell term to serve as a valid proxy for a more complex, energy-aware traversal cost. The lowest-cost path is no longer assumed to be the shortest path, which fundamentally changes the nature of the optimization problem.

5. Simulation and Experimental Results

5.1. Simulation Setup

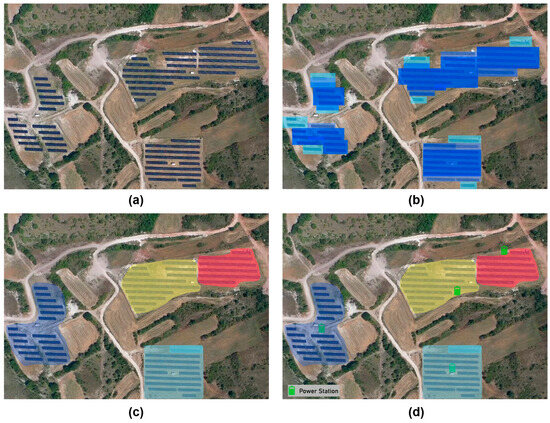

To empirically assess the effectiveness of the proposed framework, a simulated environment was created that captures the multi-attribute complexity of a real-world PV park. A grid of 50 by 50 cells was used, with each cell assigned randomized but realistic values for TrafficCount, TerrainDifficulty, and ObstaclePenalty. To ensure these ‘realistic’ values had practical credibility, the parameters for this synthetic environment were directly informed by the empirical characteristics of the actual PV park in Western Macedonia, Greece, shown in Figure 1. For example, the distribution of TerrainDifficulty values was set to mimic the slopes and ground types observed in the park’s topology. Similarly, the TrafficCount hotspots generated for a typical ‘routine cleaning’ and ‘targeted inspection’ scenarios were modeled on actual operational plans for such facilities. While a full, cell-by-cell empirical map was outside the scope of this study, this hybrid “empirically informed synthetic data” approach allows for reproducible, controlled experiments while grounding our simulation in a real-world context. The simulation was structured around two distinct operational scenarios to demonstrate the algorithm’s adaptability: one representing a “routine cleaning” period with high traffic in specific panel rows, and another representing a “targeted inspection” period with shifted traffic hotspots. An example of a realistic PV park is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of the different stages of the algorithm in an actual PV park located in Western Macedonia, Greece. Image (a) shows the initial facilities of the PV park. Image (b) shows the heatmap of the robot’s activities inside the park (areas outside of the park are never traversed by robots). Image (c) shows the area division process. Finally, image (d) shows the actual power station placement inside each sub-area. The different colors in (c,d) denote the different sub-areas that were identified by the AP algorithm.

For the purpose of this evaluation, a fleet of 100 heterogeneous UGVs and UAVs was simulated, divided into three sub-fleets with varying energy consumption rates. The weighting constants for the scoring function (Equation (2)) were set as follows: , , , and . The fairness tuning parameter in the objective function (Equation (3)) was set to to place a moderate emphasis on equitable resource distribution.

The weighting constants (, , , ) and the fairness parameter () were selected based on heuristic tuning to reflect the operational priorities of a PV park. Traffic Desirability () is weighted highest as it’s the primary driver for placement. Terrain Difficulty () and Obstacle Proximity () are also weighted heavily to ensure the selected locations are safe and energy-efficient to access. The fairness parameter () was chosen as a moderate value to demonstrate a clear trade-off between global efficiency (total distance) and equitable resource access.

The experiments compared the proposed algorithm against three baseline scenarios: (1) Random Placement, where charging stations are placed in random, accessible locations; (2) Naive Distance-Only Placement, which uses a scoring function without the new terrain and obstacle constraints. Table 1 provides a summary of the key simulation parameters, ensuring full reproducibility of the experimental results.

Table 1.

Experimental results for two environments using three clustering algorithms for CPP.

5.2. Evaluation Metrics

The performance of each algorithm was evaluated across three key metrics:

- Average Travel Distance: The mean distance a robot must travel to reach a charging station from its current position. This is a measure of logistical efficiency.

- Total Energy Consumption: The total energy expended by all robots in the fleet to reach their charging stations, calculated using the extended energy model (Equation (4)). This metric provides a more accurate representation of operational costs.

- Fairness Score: The Coefficient of Variation (CV) of the average travel distances for each of the three sub-fleets. A lower CV indicates a more equitable distribution of charging resources.

5.3. Results

The simulation results, summarized in Table 2, demonstrate the significant superiority of the proposed framework across all evaluated metrics. To ensure statistical rigor, each of the algorithmic scenarios was simulated 30 times with different randomized environment seeds and robot starting positions. The values presented in Table 2 represent the mean average of these runs. It was observed that the standard deviation for the ‘Proposed Algorithm’ was consistently low across all metrics, indicating stable and reliable performance, whereas the ‘Random Placement’ baseline showed, as expected, very high variance. The proposed algorithm consistently outperformed the random and naive placement baselines.

Table 2.

Algorithmic Comparison for Key Metrics.

The Naive Distance-Only Placement showed a significant improvement in average travel distance compared to random placement (a reduction of 50.1%). However, its performance on energy consumption was less pronounced, and its fairness score remained high.

The proposed algorithm, while having a slightly higher average travel distance than the Naive Distance-Only approach, demonstrated a dramatic reduction in both Total Energy Consumption and the Fairness Score. The energy savings of the proposed algorithm were approximately 29% better than the naive approach, which can be attributed directly to the extended energy model. By placing charging stations in locations that minimize the combined cost of distance, terrain difficulty, and friction, the algorithm selects paths that are less energy-intensive, even if they are not the shortest in terms of Manhattan distance.

Furthermore, the Fairness Score of the proposed algorithm was reduced by over 68% compared to the Naive Distance-Only placement. This is a direct consequence of the new fairness constraint, which actively seeks to minimize the disparity in travel distances between different sub-fleets. This shows that the algorithm effectively balances the trade-off between global efficiency and equitable resource allocation.

To further validate the extended energy model, a breakdown of energy consumption for a sample path was conducted, as shown in Table 3. This analysis reveals that on challenging terrain, the energy costs associated with friction and slope can constitute a substantial portion of the total energy expenditure, far exceeding the costs of turns or idle time.

Table 3.

Comparison of Energy Model Components.

This breakdown illustrates why the proposed model’s energy-aware placement leads to such significant gains. The lowest-distance path is not the lowest-energy path, and the new model correctly identifies and penalizes energy-intensive routes.

6. Discussion

6.1. Implications of the Multi-Factor Framework and Practical Considerations

The results presented demonstrate that a simple re-application of an algorithm to a dynamic environment is insufficient. The core AP algorithm serves as a powerful tool, but its effectiveness is contingent upon a problem formulation that accurately reflects the new domain. The introduced enhancements to the environment model, scoring function, and objective function are not merely cosmetic; they represent a fundamental re-conceptualization of the charging station placement problem for robotics in PV parks.

The multi-attribute grid and the refined scoring function allow the algorithm to make decisions based on real-world constraints, such as the physical characteristics of the terrain and the presence of electrical infrastructure, which were irrelevant in a structured environment. This shift from a purely logistical problem to a multi-objective engineering challenge is critical for the practical deployment of autonomous systems in PV parks.

The new energy model, in particular, provides a nuanced understanding of UGV and UAV dynamics on natural terrain. By explicitly modeling the energy costs of slope and friction, the algorithm can identify charging locations that, while perhaps slightly farther in a straight line, are significantly more efficient in terms of power consumption. This provides a compelling argument for moving beyond simple Euclidean distance metrics in energy management for off-road robotics.

The inclusion of a multi-agent fairness constraint is a crucial element for system stability and scalability. While it may slightly increase the total travel distance in a few isolated cases, its ability to ensure equitable access to resources prevents the development of operational chokepoints and promotes a more robust and harmonious multi-robot ecosystem.

The proposed framework, while robust in simulation, highlights several important considerations for real-world implementation. The model relies on the availability of rich, multi-attribute environmental data, which can be difficult to acquire and maintain in a constantly changing environment. Real-time re-planning and continuous environmental mapping (e.g., via UAV patrols) would be necessary to adapt to transient changes such as weather-induced mud or new vegetation growth. The complex interplay between multi-robot cooperation and centralized control presents additional challenges that must be addressed, particularly regarding communication and task allocation in an outdoor setting.

6.2. The Two-Stage Optimization Framework

The selection of a two-stage framework (clustering via AP followed by intra-cluster scoring) over a single, holistic optimization was a deliberate design choice. This approach prioritizes practicality, scalability, and adaptability for the specific problem domain over the pursuit of a guaranteed global optimum, which would likely be computationally intractable.

First, the physical layout of many large-scale PV parks, such as the one in Western Macedonia, Greece, depicted in our study, is not a single, contiguous field. Instead, they often consist of several geographically separate, non-contiguous panel groups. A clustering-based approach like AP is ideally suited to this topology, as it naturally identifies these distinct operational zones as separate clusters. A holistic method that does not first partition the space might incorrectly place stations in inefficient “central” locations (e.g., in a field) that are far from all actual operational areas.

Second, a key advantage of AP is its ability to determine the number of clusters—and thus charging stations—automatically from the data’s structure. Other approaches based on algorithms like k-medoids or k-means often require the number of stations, k, to be specified a priori. This is a significant drawback in a dynamic environment like a PV park, where the optimal number of stations is unknown and may change with operational demands.

Finally, this two-stage approach is more computationally scalable and extensible. A holistic, energy-aware placement problem for k stations in a large, multi-attribute grid is a complex optimization problem. Our method decomposes this into two stages: Stage 1, the AP clustering, and Stage 2, the intra-cluster scoring, which is a simple, highly parallelizable search within much smaller, localized areas. This modularity grants increased extensibility; new, complex environmental parameters (e.g., soil type, sun-shadowing penalties) can be easily added to the local scoring function without reformulating the entire (Stage 1) clustering problem.

6.3. Charging Station Capacity and Queueing

A significant consideration for real-world implementation, and a logical extension of this work, is the issue of charging station capacity and potential queueing. The current framework focuses on optimizing the placement and number of stations, but it does not explicitly define their throughput. A high-traffic, centrally located station, though optimally located in terms of travel distance, could become saturated with requests and create a new operational bottleneck, leading to robot downtime and negating the framework’s efficiency gains. This is particularly relevant in scenarios such as a coordinated cleaning routine, where an entire robot sub-fleet may deplete its energy at similar times, producing a “rush-hour” effect at the charging station. While operational strategies like staggering task start times could mitigate this, the framework itself offers a path for capacity planning. A simple but powerful extension would be to use the aggregate TrafficCount of all cells within a given cluster as a quantitative proxy for its total charging demand. This metric could then be used to scale the provisioning of each station—for example, by informing whether a location should be a simple 1-pad station or a high-capacity 5-pad “charging hub”. Of course, a dynamic simulation incorporating stochastic arrivals and queueing theory still remains a significant avenue for future research.

6.4. Computational Complexity

A critical consideration for practical deployment is the computational complexity and scalability of the framework. The core AP algorithm has a time complexity of , where is the number of data points. In our implementation, corresponds to the total number of grid cells. While this is tractable for the 50 × 50 grid used in our simulation, this complexity could become a bottleneck for significantly larger parks or higher-resolution grids. Although the clustering stage is a pre-planning process that does not need to operate in real time, scalability remains an important factor for real-world applications.

To mitigate potential computational challenges, several strategies can be employed. Sparse or approximate variants of AP can significantly reduce complexity, while hierarchical clustering schemes may provide scalable alternatives for very large environments. Preprocessing the grid to exclude non-viable or redundant cells (e.g., peripheral areas with no charging relevance) can further decrease the effective number of data points. Additionally, parallel computing can be leveraged to accelerate computation—particularly during the construction of the similarity matrix, which is one of the most computationally demanding steps of the AP algorithm. The second stage of our framework, where each cluster is independently optimized to determine power station placement, also lends itself naturally to parallel execution, further enhancing scalability.

7. Conclusions

In this research, a comprehensive framework for the strategic placement of smart charging stations in photovoltaic parks was presented. The approach presents a comprehensive framework to address the unique and dynamic challenges of a new domain. The key innovations, including a multi-attribute grid model, an extended energy consumption model accounting for slope and friction, and a multi-agent fairness constraint, were demonstrated in our comparative study to result in a more robust and practical solution. The simulation results quantitatively demonstrate that this multi-faceted approach, which considers not only distance but also energy consumption, terrain, and fairness, leads to quantifiably superior operational performance in simulation when compared to naive baseline approaches.

Looking ahead, several promising avenues for future research exist. The current model could be extended to incorporate real-time sensor data and weather forecasts, allowing for dynamic, on-the-fly placement adjustments in response to immediate environmental changes. Furthermore, the environment model could be enhanced to a full 3D representation to more accurately capture the nuances of complex terrain. Furthermore, future work should include a comprehensive sensitivity analysis to systematically optimize these weighting parameters and explore the trade-off between efficiency, safety, and fairness.

A more advanced area of exploration would be to integrate the charging station placement algorithm with a multi-objective task allocation and path-planning system, creating a truly unified and intelligent park management system. Such a system could dynamically re-allocate tasks and charging responsibilities based on real-time energy levels and path costs. Finally, the potential for mobile, solar-powered charging stations could be investigated, further increasing the operational independence and resilience of autonomous fleets.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.Z. and N.B.; Methodology, D.Z. and N.B.; Software, D.Z. and N.B.; Validation, D.Z. and N.B.; Investigation, D.Z.; Writing—original draft, D.Z. and N.B.; Writing—review & editing, D.Z.; Visualization, D.Z. and N.B.; Supervision, M.D. and C.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Al-Ezzi, A.S.; Ansari, M.N.M. Photovoltaic Solar Cells: A Review. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2022, 5, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolniak, R.; Skotnicka-Zasadzień, B. Development of Photovoltaic Energy in EU Countries as an Alternative to Fossil Fuels. Energies 2022, 15, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hammoumi, A.; Chtita, S.; Motahhir, S.; El Ghzizal, A. Solar PV energy: From material to use, and the most commonly used techniques to maximize the power output of PV systems: A focus on solar trackers and floating solar panels. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 11992–12010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.R.; Mubarak, A. Utilizing Photovoltaic Solar Panels for Real-Time Localization and Speed Detection of Approaching Illuminated Objects in Humanoid Robots. J. Field Robot. 2025, 42, 1298–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olayiwola, O.; Elsden, M.; Dhimish, M. Robotics, Artificial Intelligence, and Drones in Solar Photovoltaic Energy Applications—Safe Autonomy Perspective. Safety 2024, 10, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Arce, C.; Brenes-Torres, J.C.; Solis-Ortega, R. Swarm Robotics: Simulators, Platforms and Applications Review. Computation 2022, 10, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-F.R.; Nugroho, A. Intelligent Energy Management System for Mobile Robot. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soori, M.; Arezoo, B.; Dastres, R. Optimization of energy consumption in industrial robots, a review. Cogn. Robot. 2023, 3, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sizkouhi, A.M.M.; Esmailifar, S.M.; Aghaei, M.; Karimkhani, M. RoboPV: An integrated software package for autonomous aerial monitoring of large scale PV plants. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 254, 115217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, F.; Lingala, S.S.; Veeraboina, P. Effect of various parameters on the performance of solar PV power plant: A review and the experimental study. Sustain. Energy Res. 2023, 10, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zidane, T.E.K.; Aziz, A.S.; Zahraoui, Y.; Kotb, H.; AboRas, K.M.; Jember, Y.B. Grid-Connected Solar PV Power Plants Optimization: A Review. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 79588–79608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atayev, S.; Bayramova, G.; Heydarova, L.; Mahizade, A. Industrial Design of Photovoltaic Power Station: Design Review. In International Conference on Smart Environment and Green Technologies—ICSEGT2024; Mammadov, F.S., Aliev, R.A., Kacprzyk, J., Pedrycz, W., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, B.J.; Dueck, D. Clustering by Passing Messages Between Data Points. Science 2007, 315, 972–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baras, N.; Dasygenis, M. UGV energy-aware coverage path planning. AIP Conf. Proc. 2023, 2909, 120009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbuJabal, N.; Rabie, T.; Baziyad, M.; Kamel, I.; Almazrouei, K. Path Planning Techniques for Real-Time Multi-Robot Systems: A Systematic Review. Electronics 2024, 13, 2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akshya, J.; Priyadarsini, P.L.K. Graph-based path planning for intelligent UAVs in area coverage applications. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2020, 39, 8191–8203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabreira, T.M.; Brisolara, L.B.; Ferreira, P.R., Jr. Survey on Coverage Path Planning with Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Drones 2019, 3, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajeil, F.H.; Ibraheem, I.K.; Azar, A.T.; Humaidi, A.J. Grid-Based Mobile Robot Path Planning Using Aging-Based Ant Colony Optimization Algorithm in Static and Dynamic Environments. Sensors 2020, 20, 1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galceran, E.; Carreras, M. A survey on coverage path planning for robotics. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2013, 61, 1258–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriely, Y.; Rimon, E. Spanning-tree based coverage of continuous areas by a mobile robot. In Proceedings of the 2001 ICRA. IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (Cat. No.01CH37164), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 21–26 May 2001; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 1927–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Shao, P. Grid-Based Path Planning of Agricultural Robots Driven by Multi-Strategy Collaborative Evolution Honey Badger Algorithm. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, G.; Cielniak, G.; Heselden, J.; Pearson, S.; Duchetto, F.D.; Zhu, Z.; Dichtl, J.; Hanheide, M.; Fentanes, J.P.; Binch, A.; et al. A Unified Topological Representation for Robotic Fleets in Agricultural Applications. J. Field Robot. 2025, 42, 760–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potić, I.; Đorđević, D. Terrain Passability Modeling for Cross-Country Unmanned Ground Vehicle Navigation. Trans. GIS 2025, 29, e70035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, A.Y.S.; Leung, Y.-W.; Chu, X. Electric Vehicle Charging Station Placement: Formulation, Complexity, and Solutions. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2014, 5, 2846–2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.; Weng, Y.; Tan, C.-W. Electric Vehicle Charging Station Placement Method for Urban Areas. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2019, 10, 6552–6565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganganath, N.; Cheng, C.-T.; Fernando, T.; Iu, H.H.C.; Tse, C.K. Shortest Path Planning for Energy-Constrained Mobile Platforms Navigating on Uneven Terrains. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2018, 14, 4264–4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Li, G.; Zheng, Q.; Bai, X.; Ding, Y.; Khan, A. Path Planning for Wheeled Mobile Robot in Partially Known Uneven Terrain. Sensors 2022, 22, 5217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baras, N.; Dasygenis, M. Area Division Using Affinity Propagation for Multi-Robot Coverage Path Planning. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).