Abstract

Maternal health care during labor requires the continuous and reliable monitoring of analgesic procedures, yet conventional systems are often subjective, indirect, and operator-dependent. Infrared thermography (IRT) offers a promising non-invasive approach for labor epidural analgesia (LEA) monitoring, but its practical implementation is hindered by clinical and hardware limitations. This work presents a novel artificial intelligence-driven mobile platform to overcome these hurdles. The proposed solution integrates a lightweight deep learning model for semantic segmentation, a B-spline-based free-form deformation (FFD) approach for non-rigid dermatome registration, and efficient on-device inference. Our analysis identified a U-Net with a MobileNetV3 backbone as the optimal architecture, achieving a high Dice score of 0.97 and a 4.5% intersection over union (IoU) gain over heavier backbones while being 73% more parameter-efficient. The entire AI pipeline is deployed on a commercial smartphone via TensorFlow Lite, achieving an on-device inference time of approximately two seconds per image. Deployed within a user-friendly interface, our approach provides straightforward feedback to support decision making in labor management. By integrating thermal imaging with deep learning and mobile deployment, the proposed system provides a practical solution to enhance maternal care. By offering a quantitative, automated tool, this work demonstrates a viable pathway to augment or replace subjective clinical assessments with objective, data-driven monitoring, bridging the gap between advanced AI research and point-of-care practice in obstetric anesthesia.

1. Introduction

Labor epidural analgesia (LEA) represents the gold standard for pain management during childbirth, utilized by millions of women globally each year [1]. While highly effective, LEA is susceptible to primary failure, with reported rates ranging from 12% to 14%, necessitating timely intervention to ensure maternal comfort and safety [2]. The clinical assessment of an epidural block’s efficacy traditionally relies on subjective patient feedback and testing sensory perception to cold or light touch, methods which are indirect and operator-dependent [3]. An objective, quantitative, and automated method for evaluating the success and dermatomal spread of LEA would constitute a significant advancement in obstetric anesthesia, enabling clinicians to identify and rectify failing blocks earlier [4].

Regarding this, infrared thermography (IRT) is a non-invasive, non-contact imaging modality that captures thermal radiation emitted from a surface, producing a detailed map of its temperature distribution [5]. In the context of neuraxial anesthesia, the blockade of sympathetic nerve fibers induces vasodilation in the corresponding dermatomes, leading to increased cutaneous blood flow and a subsequent rise in skin surface temperature [6]. This physiological response provides a direct thermal signature of a successful sympathetic blockade. Plantar thermography, focusing on the soles of the feet, is particularly informative, as this region contains a high density of arteriovenous anastomoses involved in thermoregulation, making them highly responsive to changes in sympathetic tone [7]. The dermatomes corresponding to the lower lumbar and sacral nerve roots (L4, L5, and S1), which are targeted during LEA, innervate the plantar surface, making it an ideal region for monitoring analgesic efficacy [8].

Nevertheless, thermography-guided LEA monitoring relies on precise semantic segmentation of the plantar foot in thermal images acquired under dynamic clinical conditions [9]. Unlike controlled experimental environments, delivery rooms present significant thermal clutter from sources such as bedding, medical devices, and even the patient’s other leg, which can create ambiguous or false boundaries [10]. Also, the thermal contrast between the skin and the background can be low, especially during active thermography protocols where the foot is cooled and its temperature recovers from below ambient [11]. This scenario complicates classical segmentation approaches like thresholding or active contours [12]. The challenge is further exacerbated by the inherent limitations of mobile thermal cameras, which, despite their portability and accessibility, typically generate noisier images with lower spatial resolution than research-grade systems. These shortcomings can obscure subtle anatomical boundaries and significantly complicate the segmentation process [13]. Consequently, a robust solution requires the adoption of advanced deep learning models, such as U-Net architectures and vision transformers (ViTs), which have proven effective in capturing complex spatial features and demonstrating resilience to noise and resolution variations, as reported in studies on diabetic foot segmentation [14]. Nevertheless, ensuring a balance between model complexity and segmentation performance remains crucial to enabling deployment on portable devices for clinical support [15,16].

Moreover, the human foot exhibits substantial anatomical variability in both size and shape, while its position and posture can change markedly between image acquisitions, particularly in patients undergoing labor [17]. Consequently, traditional rigid image-based transformation methods are inadequate for achieving accurate alignment. This limitation necessitates the adoption of non-rigid registration techniques capable of modeling complex local deformations to adapt a canonical dermatome template to the patient’s specific foot anatomy [18]. Approaches such as B-spline-based free-form deformation (FFD) are especially well-suited for this purpose, as they offer the flexibility to capture fine-grained anatomical variations while maintaining smooth and physiologically plausible transformations [19]. Yet, the accuracy of this registration step is paramount, as misalignment of even a few millimeters could lead to incorrect dermatome temperature attribution and flawed clinical interpretation [20]. Additionally, achieving portable and flexible solutions requires lightweight registration methods that are suitable for mobile deployment.

Indeed, an end-to-end mobile platform for thermographic imaging-based LEA monitoring must be portable and optimized for point-of-care use. For the tool to be clinically useful, it must provide near-real-time feedback (i.e., within minutes) on a device readily available in a maternal health environment, such as a smartphone or tablet [21]. The latter requires overcoming the significant computational constraints of mobile devices. Deep learning models, while powerful, are resource-intensive [22]. Then, the successful integration of a high-performance segmentation model and a registration algorithm into a user-friendly mobile interface, as demonstrated in related clinical fields, is essential to translating this technology from a research concept to a practical clinical instrument [23].

These technological hurdles—robust segmentation in cluttered environments, precise non-rigid anatomical registration, and efficient on-device deployment—collaboratively define the technical gap between the current state of research and a functional clinical tool [24]. The literature confirms the physiological premise of thermography for LEA and shows the potential of individual components, such as CNNs for foot segmentation in other domains [25]. However, no existing work has integrated these three critical components into a single and cohesive mobile framework for the specific purpose of LEA monitoring. Specifically, the state of the art indicates that while thermography is a physiologically sound method for assessing neuraxial blockade, its application has been hampered by a reliance on manual analysis [26]. Concurrently, powerful AI-based segmentation and registration techniques have been developed but have not been applied to this specific clinical problem, nor have they been integrated into a practical point-of-care mobile solution [27].

In this work, we present a novel AI-powered mobile platform for the objective analysis of plantar thermograms to support maternal care during epidural procedures. We hypothesize that an automated workflow—integrating a lightweight deep learning model for semantic segmentation with a tailored non-rigid registration strategy for dermatome mapping—can accurately quantify temperature variations and deliver intuitive, real-time feedback to clinicians. By uniting thermal imaging, deep learning, and mobile deployment, the proposed platform constitutes a practical, accessible, and non-invasive solution to strengthen maternal health monitoring and enhance clinical decision making during labor management. In summary, our main contributions are fourfold:

- –

- We propose and implement a novel end-to-end mobile application that integrates a high-performance deep learning segmentation pipeline, a non-rigid dermatome registration module, and efficient on-device inference specifically for LEA monitoring.

- –

- We provide a rigorous performance baseline for this new application by comparing state-of-the-art CNN segmentation architectures to identify the optimal model for on-device deployment. Our analysis identified U-Net with a MobileNetV3 backbone as the best-suited model, achieving a high Dice score of 0.97 while being 73% more parameter-efficient than heavier, similarly performing backbones.

- –

- We implement and adapt a B-spline-based FFD registration framework to accurately map a canonical dermatome template onto patient-specific anatomy. Our implementation was tailored for this task by employing a multi-resolution optimization strategy, ensuring its efficiency for mobile use.

- –

- We deploy the entire AI-powered workflow, centered on the lightweight U-Net-MobileNetV3 model, on a commercial Android device, leveraging a TFLite-quantized model. This validates the platform’s point-of-care capability, achieving an execution time of the entire AI pipeline of approximately two seconds.

By embedding the entire pipeline into a lightweight mobile application, the approach ensures portability, which may provide clinicians with both immediate and longitudinal insights into sympathetic blockade progression. This combination of automated image analysis and mobile deployment represents a novel step toward accessible, reproducible, and objective non-invasive monitoring in obstetric settings.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the related work. Then, Section 3 details the data acquisition protocol, the architecture of the proposed models, the non-rigid registration method, and the mobile application implementation. Section 4 and Section 5 present the experiments and results. Finally, Section 6 depicts the concluding remarks and future work.

2. Related Work

This section reviews the key technological and clinical domains that form the foundation of our work. We begin by examining the use of infrared thermography as a tool for assessing neuraxial blockade, summarizing its physiological basis, established methodologies, and the limitations of current practices. We then survey the landscape of AI-powered approaches relevant to our application, including deep learning for foot segmentation, non-rigid registration for anatomical alignment, and the deployment of these models on mobile platforms. Throughout this review, we critically analyze the results and shortcomings of existing methods to identify the specific research gap that our integrated, AI-driven mobile platform for LEA monitoring aims to address.

2.1. Thermography for Neuraxial Blockade Assessment

The use of IRT to assess the physiological effects of neuraxial anesthesia is a well-established concept, predicated on the principle that a successful sympathetic blockade causes a measurable increase in skin temperature in the affected dermatomes [28]. Early studies validated this relationship, showing significant temperature elevations in the lower extremities following spinal and epidural anesthesia. Recent research has focused on refining this application for specific clinical scenarios, particularly in obstetrics, and on improving the objectivity of the assessment. Several observational studies have demonstrated the feasibility of using IRT to monitor LEA. Bouvet et al. [29] conducted a prospective cohort study with 53 patients, using a FLIR-E4 camera to manually measure temperature changes at the T4, T10, L2, and L5 dermatomes, finding a significant correlation between temperature increase at T10 and successful analgesia. Similarly, Murphy et al. [26] used a high-resolution Flir T540 camera to track temperature changes in 30 women undergoing cesarean section with spinal anesthesia, observing pronounced temperature increases in the feet (mean difference of up to +6.8 °C). A follow-on study by Miglani et al. [30] in 38 laboring patients found that a 2 °C rise in hallux temperature within 10 min of epidural administration was a reliable indicator of success.

Reinforcing these findings, a recent study by Daza et al. [31] specifically evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of plantar thermography in 30 patients, demonstrating its superiority over traditional psychophysical tests (cold and touch sensation). Their work confirmed that 15 min post-administration, thermography achieved an Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) of 0.79, with a high positive predictive value (94.7%). While their study successfully utilized a custom deep learning-based tool (FEET-GUI) to automate the analysis, it focused on establishing diagnostic accuracy with high-performance research-grade cameras (FLIR E95) and did not address the distinct challenges of creating a fully integrated, point-of-care mobile platform. Specifically, their approach did not cover robust segmentation designed for lightweight on-device execution or the use of smartphone-attachable thermal camera modules [32].

While many foundational studies relied on high-resolution, research-grade thermal cameras, the emergence of affordable mobile thermal camera modules (e.g., FLIR ONE Pro) marks a significant advancement for point-of-care applications [33]. These smartphone-attachable devices offer unparalleled portability and seamless integration into dynamic clinical settings, making them highly attractive for widespread clinical deployment [34]. Although they typically exhibit higher Noise Equivalent Temperature Difference (NETD) and lower spatial resolution than their research-grade counterparts, their practical benefits for accessibility and real-time monitoring are substantial [35]. For example, Bruins et al. [36] demonstrated the clinical feasibility of using a FLIR ONE for epidural assessment. This move towards mobile thermography is crucial to translating IRT physiological principles into practical, accessible tools for maternal health monitoring [37].

In contrast, some studies have reported a decrease in skin temperature. Bruins et al. [36], in a cohort of 61 general surgery patients, found that successful epidural anesthesia was associated with a temperature drop, which they attributed to a core-to-peripheral redistribution of body heat. This highlights the complexity of thermoregulatory responses and the need for standardized protocols. Other works, such as those by Rykała et al. [38], have explored thermography for other applications in pregnant women, such as monitoring fetal position and physiological changes across trimesters, further establishing the safety and potential of IRT in maternal health.

A summary of key studies is presented in Table 1. The literature confirms that IRT is a physiologically sound method for monitoring LEA. However, a clear gap exists: existing methods either rely on subjective manual analysis or, when automated, have not been integrated into a cohesive, end-to-end mobile platform that can handle the challenges of lower-quality data from point-of-care thermal cameras.

Table 1.

Summary of studies on infrared thermography for neuraxial block assessment.

2.2. AI-Powered Approaches

While early studies relied on manual placement of regions of interest (ROIs) for temperature extraction, the clinical viability of a thermography-based system depends on fully automated analysis [39]. The first critical step is the semantic segmentation of the plantar foot region from the background. Classical image processing techniques, including thresholding and active contour models, have been investigated; however, they often underperform in clinical environments where the thermal contrast between the foot and surrounding background is low or inconsistent [40]. The advent of deep learning, particularly CNNs, has revolutionized medical image segmentation. Architectures like the Fully Convolutional Network (FCN), U-Net, and DeepLabV3+ have demonstrated superior performance over traditional methods [41,42,43]. Several research groups have recently applied these models to the specific problem of foot thermogram segmentation, primarily in the context of diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) detection. Cao et al. [44] proposed PFSNet, a custom U-shaped network, and achieved 97.3% intersection over union (IoU) on a private dataset of cold-stressed thermal images. Bouallal et al. [14] used a Double Encoder-ResUNet (DE-ResUnet) on the public STANDUP dataset, achieving 97% IoU; however, their approach required both thermal and color (RGB) images, adding complexity to the acquisition setup. The authors in [45] developed a prior-shape-based active contour method, reporting a Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) of 94% on a small private dataset. While these studies demonstrate the power of CNNs for this task, they have focused almost exclusively on DFU, and no study has yet performed a comparative analysis of standard CNN backbones for the specific application of epidural monitoring in parturients. A summary of relevant segmentation studies is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of recent deep learning models for foot image segmentation.

After successful segmentation of the plantar foot, the next crucial step is to overlay a standardized dermatome map to enable quantitative analysis of specific neurological regions [47]. As the size, shape, and orientation of the foot vary significantly among individuals and even among captures for the same individual, a simple rigid transformation is insufficient [48]. This problem requires non-rigid image registration, a process that finds a dense, nonlinear spatial transformation to align a source image (the dermatome template) with a target image (the segmented foot) [49]. Free-Form Deformation (FFD) models based on B-splines represent a powerful and widely used technique for non-rigid medical image registration [50]. These methods model the deformation field as a grid of control points, where the displacement of any point is interpolated using smooth B-spline basis functions [51]. This approach provides local control over the deformation while ensuring smoothness, making it robust to noise and anatomical variability [52]. While non-rigid registration is a cornerstone of medical image analysis in fields like MRI and CT, its application to registering anatomical templates like dermatome maps onto plantar thermograms has not been previously explored and represents a key novelty of the proposed workflow [53].

Moreover, this requires the deployment of the segmentation and registration pipeline onto a mobile device, a field known as Edge AI [54]. Mobile computing and the development of efficient deep learning inference frameworks, such as TensorFlow Lite (TFLite), have made this feasible [55]. A key technique for enabling on-device execution is model quantization, which converts the 32-bit floating-point weights of a trained neural network into lower-precision formats [56]. This process not only reduces a model’s memory footprint and accelerates computation but can sometimes even improve model accuracy by acting as a form of regularization [57]. For instance, Chen et al. demonstrated that quantization can improve accuracy by up to 1% for biomedical image segmentation while achieving a 3.5× to 6.4× memory reduction [58]. Several studies have demonstrated the feasibility of smartphone-integrated thermal imaging for various medical applications. Germi et al. reported the use of a FLIR One-equipped iPhone to monitor sympathetic dysfunction as a complication of neurosurgery [13]. Awaly et al. successfully used a similar setup intra-operatively to locate a retained surgical catheter by detecting the associated inflammation [23]. In the context of diabetic foot care, Agustini et al. developed and validated the M-DFEET (Mobile Diabetic Foot Early Self-Assessment) application, an Android-based tool that guides patients through a structured self-examination protocol based on the Health Belief Model, without using a thermal camera or AI analysis [59]. In summary, Table 3 highlights existing mobile health applications that validate the hardware–software paradigm but remain constrained to basic case reports or non-AI-driven tools.

Table 3.

Mobile and enabling technologies for clinical thermography.

Lastly, a significant challenge in developing and benchmarking robust AI algorithms for thermographic analysis, particularly for applications like LEA monitoring, is the scarcity of large, publicly available, and appropriately annotated datasets [60]. While several public datasets of plantar thermograms exist, many are not directly suitable for our target application. For instance, the INAOE Plantar Thermogram Database [40] and the STANDUP database [61] both focus on diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) detection and lack semantic labels for dermatomes or parturients. However, a notable and highly relevant development is the publicly available infrared imaging dataset for LEA, presented by Aguirre-Arango et al. [62]. The dataset comprises 166 thermal images from pregnant women undergoing epidural anesthesia, with foot regions segmented by an anesthesiologist to serve as ground truth. While the provided data are invaluable for foot segmentation in the context of LEA monitoring, the dataset does not include dermatome-level annotations, thereby limiting its applicability for fine-grained clinical assessment. Moreover, the dataset has not yet been adapted or validated for edge or mobile device deployment, which constrains its usability in real-time, point-of-care settings where portability and low-latency analysis are critical.

In conclusion, the literature shows that while powerful individual AI components for segmentation, registration, and mobile deployment exist, they have largely been developed in isolation or for other clinical domains. The primary limitations identified are the lack of an integrated system designed specifically for LEA monitoring, the absence of comparative analyses for this task, and the scarcity of fully annotated datasets. Our work is designed to bridge these gaps by developing and validating the first cohesive mobile platform that unites these advanced AI techniques into a practical, point-of-care tool for maternal health.

3. Materials and Methods

This section details the methodology employed to develop and validate our AI-driven mobile platform. We begin by describing the thermographic imaging dataset used for training and testing our models, including the data acquisition protocol and patient demographics. Next, we outline the deep learning fundamentals for the semantic segmentation task, detailing the model architectures and loss functions evaluated. We then describe the non-rigid registration framework used for dermatome mapping. Finally, we detail the implementation of the end-to-end mobile application, explaining the software architecture and the workflow from data acquisition to clinical result visualization.

3.1. Thermographic Imaging Dataset

The primary dataset used in this study, hereafter referred to as the ThermalFeet dataset [62], was collected as part of a clinical research project investigating the use of IRT for monitoring the physiological effects of LEA in obstetric patients. The plantar surface of the feet was selected as the region of interest due to its high density of arteriovenous anastomoses, making it highly sensitive to sympathetically mediated changes in cutaneous blood flow and temperature. The dataset is characterized by challenges inherent to clinical data acquisition, including low thermal contrast, patient movement artifacts, and physiological variability, making it a robust testbed for developing resilient segmentation algorithms. It is publicly available and has been previously utilized to validate deep learning segmentation models in this clinical context [63].

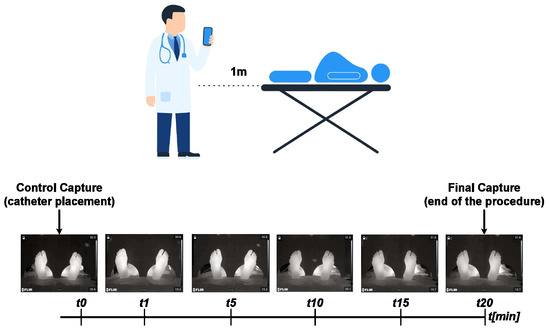

The dataset comprises thermographic recordings from 30 healthy full-term pregnant women. Participants were between 18 and 45 years old, classified as ASA II, and had no history of peripheral neuropathy or vascular disease. Data for the primary ThermalFeet dataset were acquired using an industrial-grade FLIR A320 infrared camera mounted on a tripod at an approximate distance of 1.5 m from the patient’s feet. Patients were positioned supine with their soles placed on a non-reflective support to minimize thermal artifacts. Key imaging parameters for the FLIR A320 were standardized as follows: The thermographic system employed in this study features a native thermal resolution of 320 × 240 pixels, operating within the long-wave infrared (LWIR) spectral range of 7.5–13 μm. It achieves a thermal sensitivity (NETD) below 50 mK, enabling the detection of subtle temperature variations across the skin surface. For accurate physiological monitoring, the device was calibrated with an emissivity value of 0.98, consistent with the emissive properties of human skin. Furthermore, the imaging protocol was synchronized with the anesthetic procedure, as illustrated in Figure 1. A baseline () image was captured immediately after the first administration of the analgesic mixture, followed by time-series acquisition every five minutes for 20 min post-injection (, , , and ).

Figure 1.

Regional analgesia monitoring protocol. Thermal images are captured at defined intervals following epidural catheter placement to track temporal changes in the plantar region.

Moreover, detailed demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 4 and Table 5. Notably, the dataset was collected at SES Hospital de Caldas under a protocol approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (Acta DC-047-18), with all participants providing written informed consent.

Table 4.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patient cohort (). Values are presented as means ± standard deviations (SDs) along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Table 5.

Summary of key maternal and fetal physiological variables recorded during the labor epidural analgesia procedure at standardized monitoring intervals. Measurements were obtained immediately after epidural administration () and subsequently , and minutes post-injection, corresponding to the validated acquisition protocol illustrated in Figure 1. The variables reported include systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP), maternal and fetal heart rate (HR and FHR), and pain intensity (VAS), which reflect the physiological and thermal responses most relevant to sympathetic blockade assessment.

To complement this dataset and evaluate our methodology’s robustness across different types of hardware, additional samples were acquired using a Fluke TC01A mobile thermal camera module. This device connects directly to an Android smartphone, offering a portable solution with the following specifications: The thermal imaging device used in this study provides a thermal resolution of 256 × 192 pixels, allowing for reliable visualization of temperature gradients across the region of interest. Its thermal sensitivity (NETD) of 50 mK ensures the detection of fine thermal variations, which are essential to capturing subtle physiological changes during monitoring.

All images from both camera systems were exported and resized to a standard resolution of pixels in PNG format. This preprocessing step harmonizes the different native resolutions of the source cameras ( and pixels) into a uniform format for batch processing in deep learning frameworks. The dimension was chosen as a high-fidelity resolution to ensure that all spatial details from the original images were preserved after upsampling, creating a standardized master dataset without loss of critical boundary information. This master dataset was formed by aggregating the images from the original ThermalFeet study with the new samples acquired using the Fluke TC01A camera. Hence, the combined dataset comprises 354 annotated thermal images, partitioned into training (248 samples), validation (71 samples), and test (35 samples) subsets. Each sample consists of a single-channel thermal image and a corresponding binary semantic segmentation mask. A clinical expert manually annotated the masks, labeling pixels as either ‘Foot’ (value 1) or ‘Background’ (value 0). This complete, curated collection is the final dataset used in our study, which we refer to as the ‘Feet Mamitas’. It is publicly available for research purposes on Kaggle (see https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/lucasiturriago/feet-mamitas—accessed on 1 July 2025).

3.2. Deep Learning Fundamentals for Semantic Image Segmentation

Given a dataset of input–output pairs, , where denotes an input image of size with C channels (e.g., a thermographic foot image) and the corresponding ground-truth mask encodes pixel-wise class assignments across K categories (e.g., foot regions vs. background), the objective of semantic segmentation is to learn a mapping that assigns, for each pixel, a probability distribution over the K semantic categories. This function, parameterized by a set of learnable weights , takes an input image and produces a probability map , where each pixel contains a vector of class probabilities. The optimal parameters are estimated by minimizing an expected loss function over the dataset:

Therefore, is fixed as a composition of functions, yielding

where denotes the l-th layer mapping (), parameterized by weights and biases , where is the convolutional kernel size. The feature map is given by

with being a nonlinear activation and ⊗ denoting convolution. Thus, represents learned features, obtained by transforming into salient representations at layer l.

Remarkably, the choice of the loss function in Equation (1) plays a pivotal role in steering the optimization process and in tackling the inherent challenges of semantic segmentation. The effectiveness of a given function strongly depends on factors such as class imbalance, boundary complexity, and the variability of target structures [64].

Given the target-predicted pair and , we assessed four widely adopted loss functions:

- –

- Categorical Cross-Entropy (CE): The standard pixel-wise CE loss serves as our baseline, owing to its probabilistic interpretation and stability during optimization [65]:where denotes the Frobenius inner product between the tensors.

- –

- Dice: To directly address class imbalance by maximizing the spatial overlap between predicted and ground-truth masks, we implement the Dice loss, derived from the Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) [66]:where is a tensor of ones and prevents division by zero.

- –

- Focal: It is employed to mitigate the influence of easily classified background pixels and focus training on challenging examples [67]:where ⊙ is the element-wise (Hadamard) product, is a focusing hyperparameter (set to ), and ensures numerical stability.

- –

- Tversky: As a generalization of the Dice loss, it is used to provide explicit control over the trade-off between false positive (FP) and false negative (FN) rates [68]:where control the penalties for FP and FN errors, respectively.

Regarding the architectures employed to model in Equation (2), we systematically evaluated and compared three seminal approaches to semantic segmentation: U-Net [44], ResUNet [14], and DeepLabV3+ [69]. To ensure both fairness and robustness, all models were implemented using two encoder configurations: a ResNet34 and a MobileNetV3 backbone, each initialized with ImageNetV1 pre-trained weights [70]. This dual-encoder strategy allowed for a balanced assessment between accuracy and computational efficiency.

A key requirement of the proposed mobile platform is efficient inference on resource-constrained devices, such as smartphones, which possess limited memory, processing capacity, and battery life. These constraints render conventional high-capacity deep learning models impractical for on-device deployment. Consequently, lightweight architectures are required—models specifically designed to minimize computational cost (in FLOPs) and memory footprint (in parameters) while preserving high predictive accuracy. Modern lightweight backbones such as MobileNetV3 achieve this efficiency primarily by replacing standard, computationally expensive convolutions with depth-wise separable convolutions. This operation decomposes a standard convolution into two simpler steps: a depth-wise convolution that applies a single filter per input channel, followed by a point-wise convolution to combine the outputs. This factorization substantially reduces both the number of parameters and the computational burden compared with conventional convolutions. Beyond this core optimization, MobileNetV3 incorporates additional design elements—such as inverted residual blocks and squeeze-and-excitation layers—to further enhance the accuracy–efficiency trade-off. Our dual-encoder approach, contrasting the high-capacity ResNet-34 with the lightweight MobileNetV3, was, therefore, explicitly designed to quantify this trade-off, which is critical to effective point-of-care deployment. The ResNet34 variants serve as high-capacity baselines capable of extracting detailed feature representations, whereas the MobileNetV3 counterparts explore lightweight designs optimized for real-time inference and edge deployment. Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 illustrate both configurations, also detailed as follows:

- –

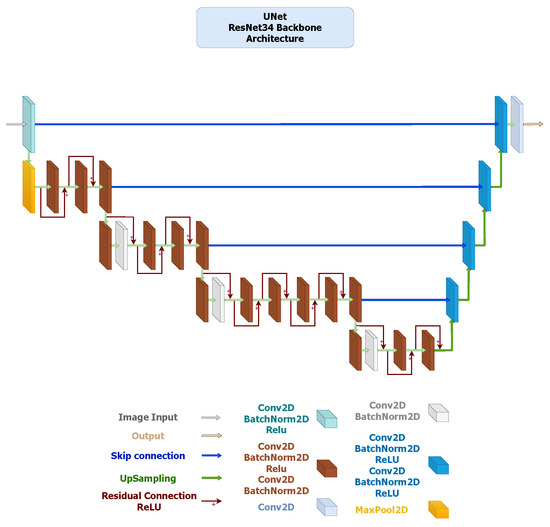

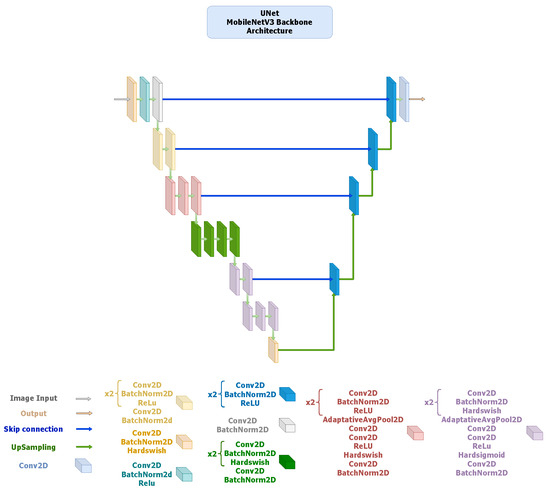

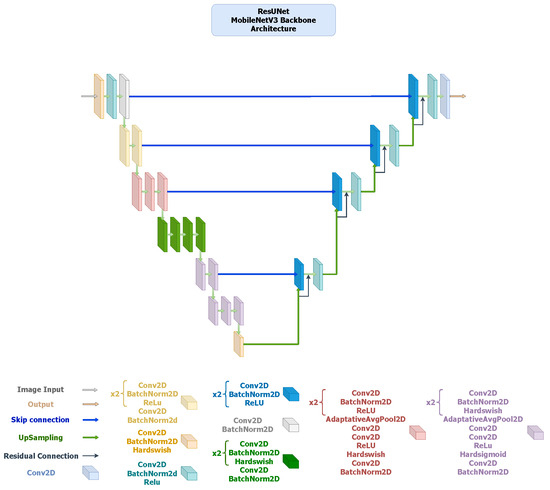

- U-Net: It employs a symmetric encoder–decoder design with skip connections that concatenate features from the contracting to the expanding path, facilitating precise localization and recovery of spatial details. The ResNet34-based configuration (Figure 2) provides a robust baseline with strong representational capacity, while the MobileNetV3-based version (Figure 3) maintains the same topology using depth-wise separable convolutions to reduce computational cost and parameter count. Both implementations yielded highly accurate segmentation, confirming that spatial precision can be retained even in compact encoder variants.

Figure 2. U-Net architecture employing a ResNet-34 encoder pre-trained on ImageNet V1. The encoder extracts hierarchical feature maps across five stages with channel dimensions using convolutions, BatchNorm, and ReLU activations. The decoder consists of four DoubleConv upsampling blocks (channels ) with bilinear interpolation and skip connections to the corresponding encoder levels. The segmentation head is a single convolution producing the binary mask output.

Figure 2. U-Net architecture employing a ResNet-34 encoder pre-trained on ImageNet V1. The encoder extracts hierarchical feature maps across five stages with channel dimensions using convolutions, BatchNorm, and ReLU activations. The decoder consists of four DoubleConv upsampling blocks (channels ) with bilinear interpolation and skip connections to the corresponding encoder levels. The segmentation head is a single convolution producing the binary mask output. Figure 3. U-Net architecture using a MobileNetV3-Large encoder pre-trained on ImageNet V1. The encoder generates feature maps at five scales with channel sizes . Depth-wise-separable convolutions and squeeze-and-excitation layers are employed for efficiency, with Hard-Swish activations. The decoder mirrors the encoder structure through DoubleConv upsampling blocks () using bilinear interpolation, followed by a convolution output layer.

Figure 3. U-Net architecture using a MobileNetV3-Large encoder pre-trained on ImageNet V1. The encoder generates feature maps at five scales with channel sizes . Depth-wise-separable convolutions and squeeze-and-excitation layers are employed for efficiency, with Hard-Swish activations. The decoder mirrors the encoder structure through DoubleConv upsampling blocks () using bilinear interpolation, followed by a convolution output layer. - –

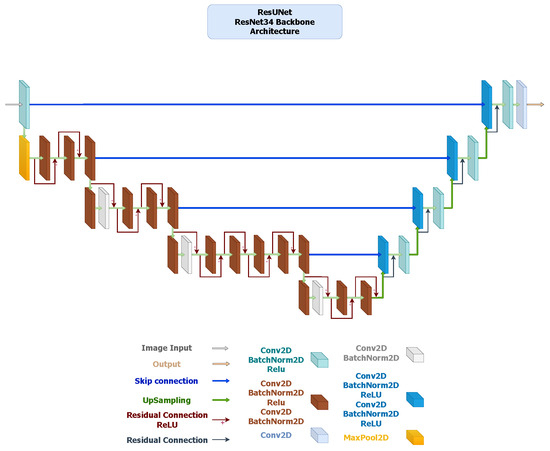

- ResUNet: It extends the U-Net framework by incorporating residual blocks in both the encoder and decoder, improving gradient flow and enabling deeper feature extraction (Figure 4). The ResNet34 encoder offers strong multi-level feature representation, while the MobileNetV3 variant (Figure 5) replaces standard convolutions with inverted residual blocks and squeeze-and-excitation layers to achieve substantial reductions in parameters and inference time. Both versions preserve boundary precision and detail consistency, demonstrating that residual connectivity remains effective even in compact encoder settings.

Figure 4. ResUNet architecture with a ResNet-34 encoder pre-trained on ImageNet V1. The encoder comprises five residual stages with channel sizes . The decoder replaces standard convolutions with ResidualBlock modules (two convolutions + BatchNorm + ReLU) arranged as , using skip connections and bilinear upsampling. A final convolution forms the segmentation head.

Figure 4. ResUNet architecture with a ResNet-34 encoder pre-trained on ImageNet V1. The encoder comprises five residual stages with channel sizes . The decoder replaces standard convolutions with ResidualBlock modules (two convolutions + BatchNorm + ReLU) arranged as , using skip connections and bilinear upsampling. A final convolution forms the segmentation head. Figure 5. ResUNet architecture using a MobileNetV3-Large encoder pre-trained on ImageNet V1. The encoder outputs five hierarchical feature maps with channel sizes . The decoder employs ResidualBlock modules () incorporating inverted residual and squeeze-and-excitation operations. The final segmentation head is a convolution.

Figure 5. ResUNet architecture using a MobileNetV3-Large encoder pre-trained on ImageNet V1. The encoder outputs five hierarchical feature maps with channel sizes . The decoder employs ResidualBlock modules () incorporating inverted residual and squeeze-and-excitation operations. The final segmentation head is a convolution. - –

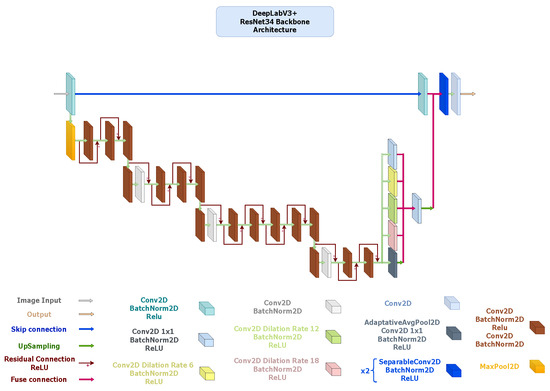

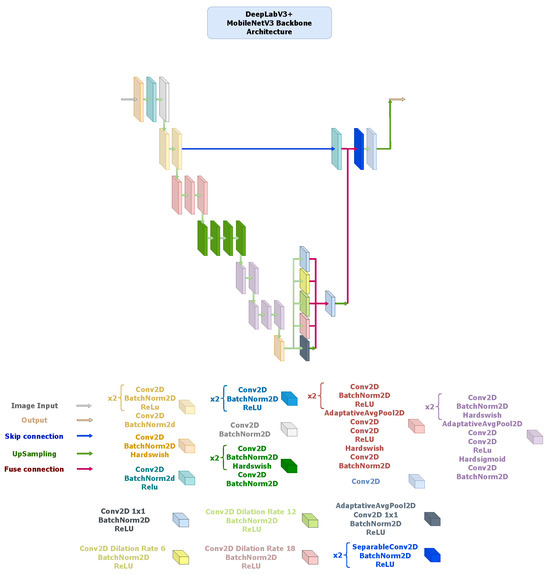

- DeepLabV3+: It integrates an encoder–decoder structure with Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) [69] to capture multi-scale contextual information without losing spatial resolution. The ResNet34 backbone (Figure 6) provides high representational power but incurs greater computational cost, whereas the MobileNetV3-based alternative (Figure 7) replaces standard convolutions with depth-wise separable operations throughout the ASPP and decoder, resulting in a much lighter configuration. Although the MobileNetV3 variant exhibits slightly lower accuracy, it maintains sufficient contextual awareness for effective thermal foot segmentation under real-time constraints.

Figure 6. DeepLabV3+ architecture with ResNet-34 encoder pre-trained on ImageNet V1. Configured with an output stride of 16, the Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) module applies atrous rates of 6, 12, and 18 on 512-channel high-level features. The 256-channel ASPP output is upsampled and fused with 64-channel low-level encoder features projected to 48 channels. Two SeparableConv2D + BatchNorm + ReLU layers precede a final convolution segmentation head.

Figure 6. DeepLabV3+ architecture with ResNet-34 encoder pre-trained on ImageNet V1. Configured with an output stride of 16, the Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) module applies atrous rates of 6, 12, and 18 on 512-channel high-level features. The 256-channel ASPP output is upsampled and fused with 64-channel low-level encoder features projected to 48 channels. Two SeparableConv2D + BatchNorm + ReLU layers precede a final convolution segmentation head. Figure 7. DeepLabV3+ architecture using a MobileNetV3-Large encoder pre-trained on ImageNet V1. The encoder outputs feature maps of sizes , followed by an ASPP module configured with dilation rates of 6, 12, and 18 and a fused 256-channel bottleneck. The decoder concatenates this output with 64-channel low-level features, applies two depth-wise-separable convolution blocks ( kernels, stride 1), and ends with a convolution for segmentation. Hard-Swish and ReLU activations are used throughout, with bilinear upsampling to restore spatial resolution.

Figure 7. DeepLabV3+ architecture using a MobileNetV3-Large encoder pre-trained on ImageNet V1. The encoder outputs feature maps of sizes , followed by an ASPP module configured with dilation rates of 6, 12, and 18 and a fused 256-channel bottleneck. The decoder concatenates this output with 64-channel low-level features, applies two depth-wise-separable convolution blocks ( kernels, stride 1), and ends with a convolution for segmentation. Hard-Swish and ReLU activations are used throughout, with bilinear upsampling to restore spatial resolution.

3.3. Non-Rigid Registration for Dermatome Mapping

Following semantic segmentation, which yields, for each thermal image , a probabilistic mask (see Section 3.2), the subsequent step is to establish a standardized anatomical coordinate system. This stage is essential to enabling reproducible and anatomically consistent quantification of each foot temperature variation across specific dermatomes for LEA monitoring. Owing to both inter-subject variability in plantar anatomy and intra-subject postural shifts, rigid transformations fail to provide accurate alignment [48]. To address these limitations, we adopt a non-rigid registration framework that aligns the canonical dermatome atlas with each patient-specific thermal image , where denotes the cropped bounding-box region extracted from using the predicted feet masks obtained from , with and .

Formally, the registration problem is cast as the estimation of the optimal parameters of a non-rigid transformation that warps the source image (atlas ) onto the target image (patient thermogram ). We adopt a B-spline-based Free-Form Deformation (FFD) model, a widely used approach in medical image registration [71]. To ensure robust convergence, the registration process is initialized using a global affine transformation to provide coarse alignment of the atlas to the target image’s position, scale, and orientation. The subsequent FFD optimization then refines this initial alignment by modeling the local, non-rigid deformations.

The transformation is defined as the identity mapping perturbed by a displacement field parameterized by a grid of control-point displacements :

where denotes the image domain. The displacement field is expressed component-wise. Let be the matrices encoding the horizontal and vertical control-point displacements , respectively. For a given point , with normalized coordinates relative to the local B-spline grid, the basis matrix is defined by the outer product of cubic B-spline basis functions. Thus, the displacement field is computed as

where denotes the Frobenius inner product, ensuring smooth interpolation between control points.

The optimal deformation is obtained by minimizing a composite cost functional:

where is the Normalized Cross-Correlation (NCC) image similarity metric quantifying the alignment between the patient thermogram and the warped atlas . Moreover, is a regularization functional that penalizes implausible deformations, typically by enforcing smoothness via first- and second-order derivatives of . In addition, is a hyperparameter balancing similarity fidelity and deformation regularity.

Once the optimal transformation is determined, it is applied to the semantic labels of the canonical atlas to project the dermatome regions of interest (ROIs) onto the patient-specific plantar surface. This results in a personalized dermatome map , which provides anatomically consistent ROIs for quantitative temperature analysis.

3.4. Mobile Platform Implementation and User Interface Design

To translate the AI-driven analysis—encompassing semantic image segmentation for foot identification from thermographic images and non-rigid registration for dermatome mapping in regional analgesia monitoring—into a practical clinical solution (see Section 3.2 and Section 3.3), we developed a point-of-care mobile application for the Android platform. The primary design goal is to create an intuitive user interface (UI) that simplifies the clinical workflow, from patient registration to the visualization of longitudinal results.

Furthermore, ethical considerations—especially those related to data privacy—were paramount. The management of sensitive patient information was meticulously designed to ensure full compliance with Colombia’s data protection law (Ley 1581 de 2012, or Habeas Data) and its associated regulations [72]. To address these requirements proactively, we adopted a privacy-by-design strategy, prioritizing on-device processing and secure local storage. This approach minimizes data exposure by ensuring that patient thermograms and derived data do not leave the user’s device, thereby mitigating privacy risks. Additionally, we employed user-centered design (UCD) principles to create a minimalist, high-contrast UI. This strategy not only enhances usability but also serves as a risk mitigation measure by reducing cognitive load on clinicians and minimizing the potential for interpretation errors in fast-paced clinical environments.

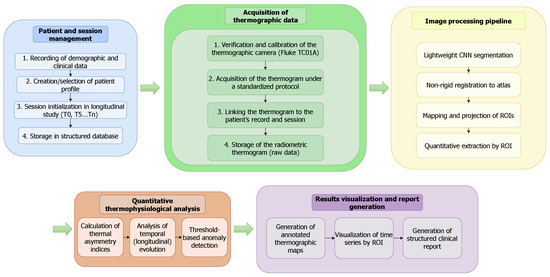

The application’s workflow is organized into five core stages: Patient and Session Management, Thermographic Data Acquisition, an automated Image Processing Pipeline, Quantitative Thermophysiological Analysis, and Results Visualization. It is developed for Android using Kotlin, while specialized image processing and visualization tasks are executed through Python scripts integrated via the Chaquopy plugin. The principal libraries and technical stack utilized are as follows:

- –

- UI/Frontend: AndroidX libraries (Core-Ktx 1.10.1, AppCompat 1.6.1), Material Components 1.10.0, and MPAndroidChart 3.1.0 for data visualization.

- –

- Image Handling: Glide 4.12.0 for efficient image loading and PhotoView 2.3.0 for interactive image viewing.

- –

- On-Device AI: TensorFlow Lite 2.16.1 and TensorFlow Lite Select-TF-Ops 2.16.1 for executing the quantized segmentation model.

- –

- Data Processing and Utilities: Chaquopy 16.0.0 to integrate Python scripts, tess-two 9.1.0 for Optical Character Recognition (OCR), and Gson 2.10.1 for data serialization.

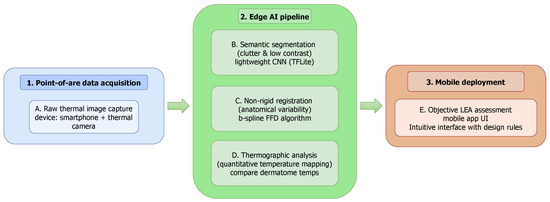

As illustrated in Figure 8, the application’s end-to-end workflow begins with Patient and Session Management, where clinicians record demographic data and create a patient profile, which is stored locally. The Acquisition of Thermographic Data module is then initiated for a specific session (, , etc.); a thermogram is captured using a mobile thermal camera (Fluke TC01A), calibrated, and linked to the patient’s record. This raw radiometric data is then passed to the on-device Image Processing Pipeline. Here, a lightweight CNN performs semantic segmentation, followed by non-rigid registration to map a canonical dermatome atlas onto the foot region. The resulting registered ROIs are used for Quantitative Thermophysiological Analysis, where thermal asymmetry indices and longitudinal temperature changes are calculated. Finally, the Results Visualization and Report Generation module presents this information to the clinician through annotated thermal maps and time-series plots, with all processed data and results stored locally in the patient’s record. Patient data confidentiality is safeguarded through secure local storage, while a minimalist, high-contrast user interface is implemented to reduce cognitive load and mitigate the risk of interpretation errors in dynamic clinical settings.

Figure 8.

End-to-end workflow of the mobile thermography platform. The process flows from patient management and data acquisition through an on-device AI pipeline for segmentation and registration, culminating in quantitative analysis and result visualization for clinical decision support.

In a nutshell, Figure 9 illustrates our AI-driven mobile platform pipeline designed to support maternal health care through thermographic analysis. It integrates a deep learning-based foot segmentation from thermographic images with a non-rigid registration strategy for dermatome identification, enabling temperature mapping for LEA monitoring. This visualization encapsulates the system’s core functionality, illustrating how its processes are seamlessly deployed within an Android-native environment.

Figure 9.

AI-driven mobile platform to support maternal health care. Our approach combines deep learning-based foot segmentation from thermographic images with a non-rigid registration framework for dermatome identification and temperature mapping, enabling the accurate and objective monitoring of labor epidural analgesia.

4. Experimental Setup

To test the deep learning and non-rigid registration strategies, experiments were conducted on Kaggle using a Tesla P100-PCIE-16GB GPU with CUDA version 12.4. The software environment was configured with Python 3.12.11, PyTorch 2.6.0+cu124, and the gcpds-cv-pykit library (v0.1.0.63), a custom Python package built on top of PyTorch, NumPy, and Matplotlib to streamline code integration and testing routines. Additional dependencies included matplotlib 3.10.0, numpy 2.0.2, and kagglehub 0.3.13. All experiments were executed in a fully reproducible environment, with source code and configuration files publicly available at https://github.com/UN-GCPDS/Mamitas (accessed on 26 October 2025).

Moreover, all segmentation architectures were trained using the Adam optimizer with a batch size of 36 for up to 60 epochs. The Adam optimizer was selected due to its widespread adoption and proven effectiveness in deep learning applications, as its adaptive learning rate capabilities provide robust and efficient convergence across different model architectures [64]. A batch size of 36 was chosen as the maximum size that could be accommodated by the 16 GB VRAM of the available GPU, ensuring stable gradient estimation while maximizing training efficiency. Training was conducted for a fixed duration of 60 epochs, a limit determined empirically to be sufficient for all models to reach convergence. Our observations during experimentation showed that model performance on the validation set had stabilized by this point, ensuring that each architecture was trained to its full potential for a fair and consistent comparison. Input images and their corresponding masks were uniformly resized to pixels.

Training followed a staged fine-tuning strategy adapted to the characteristics of each backbone architecture. For the ResNet34-based models, the process began by training the decoder and segmentation head while keeping the encoder weights frozen. Subsequently, normalization layers were unfrozen to allow for feature recalibration to the thermal domain, followed by a gradual unfreezing of the deeper residual stages to enable end-to-end optimization. For the MobileNetV3-based models, a similar progressive unfreezing protocol was employed, starting from the high-level feature extraction blocks and proceeding toward the early layers that capture low-level spatial details. This hierarchical fine-tuning approach allowed the network to retain transferable representations from ImageNet while adapting progressively to the distribution and texture characteristics of thermographic data. In both cases, the base learning rate for the decoder and segmentation head was set to , while encoder parameters used a reduced rate of to prevent abrupt weight updates in pre-trained layers. To stabilize convergence during the later stages of training, an exponential learning rate scheduler with a decay factor of was applied. Each model was independently trained with four widely adopted loss functions to assess their effect on class imbalance and segmentation robustness: categorical Cross-Entropy, Dice, Focal, and Tversky. Hyperparameters were fixed across all experiments for comparability. Dice loss included a smoothing factor of ; Focal loss used and [67]; Tversky loss was implemented with a smoothing of , , and [68]. Cross-Entropy loss followed its standard formulation.

Further, segmentation performance was evaluated using four complementary metrics: Dice Coefficient, Jaccard index (also known as intersection over union (IoU)), sensitivity, and specificity [64]. Collectively, these metrics offer a comprehensive assessment of model performance by capturing overlap accuracy, robustness against false positives, and sensitivity to minority structures. To mitigate overfitting and improve generalization, on-the-fly data augmentation was applied during training. Geometric transformations included random horizontal and vertical flips and random rotations within , applied jointly to images and masks to preserve alignment. Photometric augmentations, applied only to images, comprised random adjustments in brightness, contrast, and saturation within . Additionally, Gaussian noise was injected at low probability to simulate acquisition variability. All augmented images were normalized and clamped to valid intensity ranges before training. The dataset used for foot segmentation was partitioned into training (), validation (), and testing () subsets. This 70/20/10 split is a standard and widely accepted practice for developing and evaluating deep learning models. This ratio allocates a large majority of the data for model training, provides a substantial and representative set for hyperparameter tuning and model selection during the validation phase, and reserves a completely unseen hold-out set for a final, unbiased evaluation of the selected model’s performance. Crucially, and to ensure a clinically valid and unbiased evaluation, patient-level separation was enforced to prevent data leakage.

Following the successful segmentation of the plantar region, we evaluated the performance of a B-spline-based non-rigid registration pipeline implemented in SimpleITK (v2.5.2, Insight Software Consortium, Bethesda, MD, USA). The objective of this test was to spatially align a canonical dermatome atlas with the segmented plantar masks, thereby generating patient-specific anatomical mappings for subsequent quantitative temperature analysis. The registration process employed a multi-resolution optimization strategy using a four-level Gaussian pyramid. At each level, the optimizer minimized the mean squared intensity difference between the atlas and the segmented foot region while updating the B-spline deformation grid through iterative gradient descent. A grid spacing of control points was empirically determined to provide a suitable trade-off between registration flexibility and stability. Convergence was achieved when the relative metric change fell below or after 250 iterations at the finest resolution.

All preprocessing steps, including mask resampling, boundary smoothing, and binary morphology operations, were executed within the SimpleITK framework to maintain geometric consistency. Visual verification of registration quality was conducted using overlaid contour plots and difference heatmaps. The registered dermatome atlas was subsequently resampled to the native foot coordinate system, producing a subject-specific dermatome partition suitable for downstream temperature-based analyses.

Now, to enable efficient on-device inference, the trained PyTorch models were converted to TensorFlow Lite (TFLite) using the ai-edge-torch library (v0.4.0). The workflow involved (i) exporting the trained model to a channel-last format, (ii) applying post-training quantization with FP16 precision, and (iii) generating a representative dataset from the validation set for calibration. The TFLite converter was configured with default optimization flags and restricted to built-in operations to ensure compatibility with Android devices. The resulting model was exported and validated using the ai edge litert interpreter. Finally, application execution tests were carried out on a Xiaomi 12 Pro smartphone running HyperOS 2 with 12 GB of RAM, a Snapdragon 8 Gen 1 processor, and Android 15. The deployment validated functional integration and measured inference latency and memory footprint under realistic operating conditions.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Results of Foot Segmentation from Thermographic Images

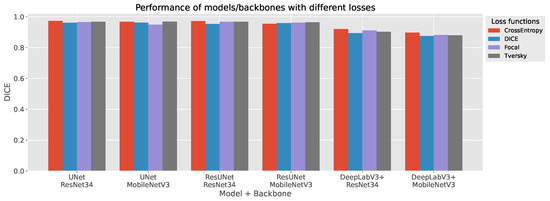

The comparative results in Figure 10 and Table 6 highlight clear performance trends across architectures, backbones, and loss functions. U-Net consistently achieved the highest segmentation accuracy, confirming its robustness for plantar thermogram analysis. With a ResNet34 encoder and Cross-Entropy Loss, it reached a Dice coefficient of 0.973 and Jaccard-IoU of 0.947, maintaining excellent sensitivity (0.985) and specificity (0.986). These metrics reflect U-Net’s ability to preserve fine structural details while minimizing background noise.

Figure 10.

Foot segmentation results from thermographic images. Quantitative comparison of segmentation models showing the mean Dice Similarity Coefficient across U-Net, ResUNet, and DeepLabV3+ with both ResNet34 and MobileNetV3 backbones trained under four different loss functions.

Table 6.

Comparison of segmentation performance across models, backbones, and loss functions. Metrics include Dice, IoU, sensitivity, and specificity for each combination of architecture and encoder. Lightweight MobileNetV3-based variants achieve comparable accuracy to their ResNet34 counterparts with a significantly lower parameter count.

ResUNet delivered comparable results, particularly under Focal and Tversky losses (Dice score of 0.967–0.971; sensitivity of up to 0.991). Its residual connections likely enhance gradient flow and feature reuse, providing a marginal sensitivity gain over U-Net. In contrast, DeepLabV3+ underperformed relative to the encoder–decoder models (Dice scores typically <0.92 for ResNet34 and <0.90 for MobileNetV3), suggesting that its atrous convolutional design captures context well but struggles with narrow inter-foot boundaries and sharp contours.

The use of MobileNetV3 backbones demonstrates a favorable balance between efficiency and accuracy. Despite a reduction in parameters of 70% (6.7–10.6 M vs. 25 M for ResNet34), U-Net and ResUNet with MobileNetV3 retained strong performance (Dice scores of up to 0.968 and 0.964, respectively). This confirms the suitability of lightweight encoders for real-time or embedded thermography, though DeepLabV3+ exhibited a sharper performance decline (Dice score ≤ 0.897) under similar compression.

Loss functions influenced performance notably. Dice and Tversky losses offered the most stable results across configurations, effectively addressing class imbalance. Cross-Entropy yielded the top Dice score for U-Net and ResUNet but slightly reduced sensitivity, while Focal loss favored sensitivity at the expense of specificity—an acceptable trade-off in detection-oriented tasks but less ideal for clinical segmentation.

Overall, encoder–decoder architectures with skip and residual connections—U-Net and ResUNet—demonstrated the best accuracy–complexity trade-off. Their high Dice and Jaccard scores, coupled with efficient parameter use, position them as the most reliable options for automated plantar segmentation. These models combine diagnostic precision with computational efficiency, enabling deployment in real-time or low-power clinical thermography systems.

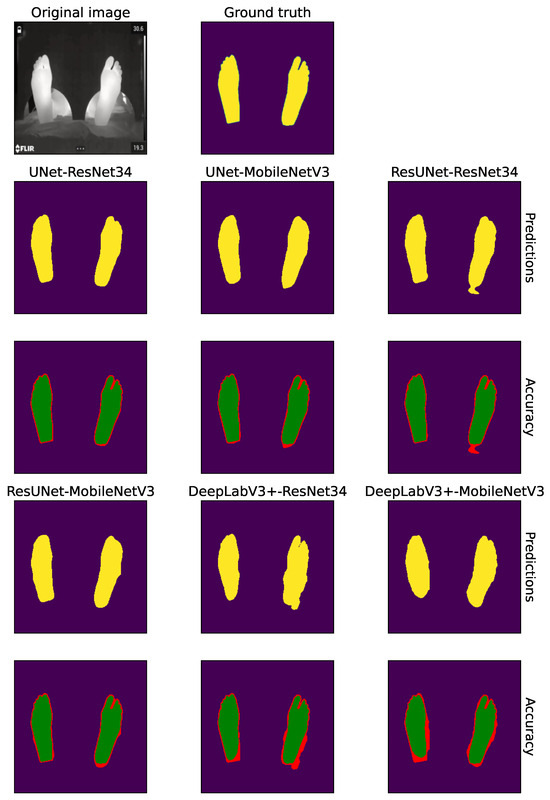

Figure 11 provides a qualitative comparison of segmentation outputs across the evaluated architectures and backbones. The top row shows the predicted binary masks, while the bottom row presents pixel-level accuracy maps, where green pixels indicate correct classifications and red pixels highlight errors relative to the ground truth.

Figure 11.

Qualitative comparison of segmentation results across architectures and backbones using Cross-Entropy loss. The panel shows, from left to right: the original thermogram and its ground-truth mask, followed by the predictions produced by U-Net, ResUNet and DeepLabV3+ with ResNet34 and MobileNetV3 encoders. In each pair of rows the top row presents the predicted segmentation, where yellow regions highlight the pixels assigned to the ‘Foot’ class by the corresponding model; the bottom row shows the pixel-wise accuracy map, with green for correctly classified pixels and red for errors.

Overall, both U-Net and ResUNet variants produced highly accurate and spatially coherent segmentations that closely align with the ground-truth contours. Their accuracy maps are dominated by green regions, with only minimal red fringes appearing at challenging boundary zones such as the toes and heel edges. Notably, the MobileNetV3 versions of these models maintained a segmentation quality comparable to their heavier ResNet34-based counterparts, exhibiting only minor smoothing at boundary transitions. This confirms that lightweight encoders can preserve high spatial fidelity despite their lower parameter count. In contrast, DeepLabV3+ exhibited more pronounced segmentation inconsistencies, particularly along foot borders and inter-foot gaps. Both backbone configurations demonstrated two recurrent error patterns: (i) the under-segmentation or merging of closely positioned feet, leading to false negatives in the inter-foot region, and (ii) slight over-segmentation near external contours, where predictions extend into the background. These visual artifacts are in agreement with the quantitative gap observed in the Dice and Jaccard-IoU indices for DeepLabV3+ (see Table 6).

Taken together, these qualitative findings reinforce the numerical analysis: U-Net and ResUNet—especially when combined with Cross-Entropy or Tversky losses—offer the most consistent and anatomically precise delineations of plantar thermograms. The MobileNetV3-based variants further demonstrate that accurate segmentation can be achieved with lightweight architectures suitable for real-time deployment in clinical or portable thermal imaging systems.

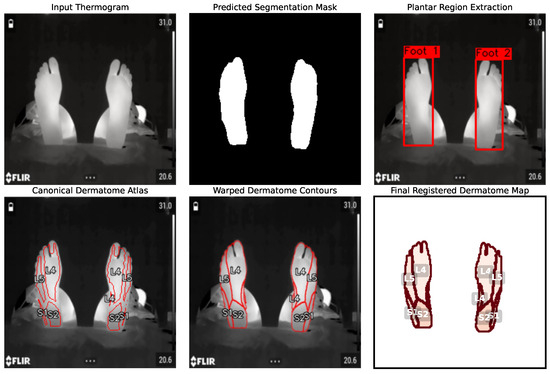

5.2. Results of Dermatome Mapping via Non-Rigid Registration

Following the successful segmentation of the plantar region, we evaluated the performance of our B-spline-based non-rigid registration module. The primary goal of this stage is to accurately and efficiently warp a canonical dermatome atlas onto the segmented foot mask, creating a patient-specific anatomical map for quantitative analysis. Figure 12 provides a qualitative, step-by-step visualization of the entire registration workflow. The process begins with the original thermographic image and the highly accurate segmentation mask produced by a U-Net model. To refine the analysis, a plantar box extraction step is introduced, which isolates the region of interest and facilitates subsequent anatomical alignment. The core of the registration is shown in the subsequent panels, where the canonical dermatome contours are deformed to align with the patient’s specific foot anatomy. Finally, the registered dermatome map provides patient-specific ROIs ready for quantitative thermal feature extraction.

Figure 12.

End-to-end visualization of the non-rigid registration pipeline. The process transforms the input thermogram into a predicted segmentation mask using the U-Net model. From this mask, plantar region extraction isolates the feet (canonical dermatome atlas). This atlas is then deformed to create warped dermatome contours that align with the patient’s specific anatomy. The process culminates in the final registered dermatome map, providing anatomically consistent ROIs.

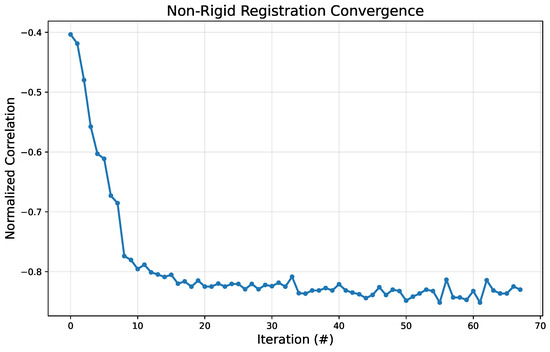

To quantitatively validate the stability and efficiency of the registration algorithm, we analyzed its convergence behavior. Figure 13 plots the value of the similarity metric (normalized correlation) against the optimization iteration number. The plot demonstrates rapid convergence, with the metric value decreasing sharply within the first 10–15 iterations. This indicates that the algorithm quickly finds a strong initial alignment between the atlas and the target image. After this initial phase, the metric stabilizes and continues to make minor refinements, converging to a stable minimum value around iteration 40. This behavior confirms that the optimization is effective and efficient, reaching a robust solution without excessive computational cost. The rapid convergence is particularly important for point-of-care application, as it ensures that the entire analysis can be completed in near-real time on a mobile device.

Figure 13.

Convergence plot for the non-rigid registration algorithm. The y-axis represents the similarity metric value (normalized correlation), while the x-axis shows the iteration number (#).

5.3. AI-Driven Mobile Platform Illustrative Results

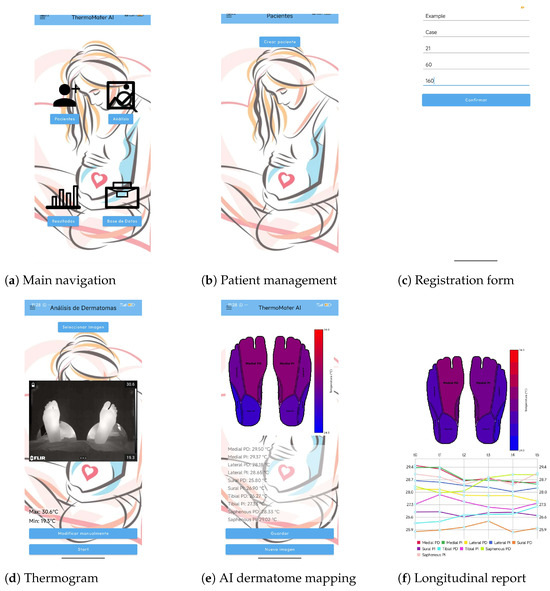

We qualitatively validate the proposed AI-driven mobile platform by illustrating its complete workflow, which transforms raw thermographic captures into quantitative and longitudinal data for maternal health monitoring regarding LEA procedures. As shown in Figure 14, the application integrates five sequential modules: patient management, image acquisition, automated segmentation and registration, dermatome-based temperature extraction, and longitudinal reporting. The workflow begins with patient registration and case management, ensuring that all thermal acquisitions are consistently linked to the correct clinical record. During analysis, clinicians capture or select a thermogram using a mobile thermal camera, after which the on-device AI pipeline automatically performs semantic segmentation of the plantar surface and B-spline-based non-rigid registration of a canonical dermatome atlas. This yields anatomically standardized ROIs, for which the system provides immediate temperature estimations and heatmap visualizations, enabling rapid clinical interpretation. Then, a distinctive feature of the platform is its longitudinal monitoring capability. By aggregating temperature values across sessions, the application generates comparative plots that display the temporal evolution of dermatomal responses, allowing clinicians to objectively assess the progression and efficacy of epidural analgesia.

Figure 14.

Illustrative workflow of the AI-driven mobile platform. (a) The main navigation screen, providing access to patient management, analysis, results, and the database. (b) The patient management module, where clinicians can select existing patients or create new ones. (c) The new patient registration form for entering demographic data. (d) The thermogram acquisition screen, where a thermal image is selected for analysis. (e) The automated AI analysis result, displaying the segmented plantar surface with the registered dermatome map and the extracted mean temperature for each region. (f) The longitudinal report, which plots the temperature evolution of each dermatome across multiple time points for objective monitoring.

Collectively, these results highlight the platform’s key contributions: (i) seamless integration of advanced AI methods into a lightweight mobile application, (ii) standardized and automated temperature quantification across dermatomes, and (iii) longitudinal, data-driven decision support for obstetric analgesia. By replacing traditionally subjective procedures with an efficient, reproducible, and interpretable workflow, the proposed solution demonstrates strong potential as a point-of-care tool for maternal health care.

5.4. Software Validation and Comparative Analysis

To validate the design and implementation of our AI-based platform, we conducted an evaluation based on the internationally recognized software quality standard, ISO/IEC 25030 (systems and software quality requirements and evaluation—SQuaRE) [73]. This standard provides a comprehensive framework for assessing the quality of a software product across several key characteristics. Table 7 presents a compliance analysis of our platform against the most relevant quality attributes for clinical point-of-care application, demonstrating its readiness as a robust engineering artifact.

Table 7.

Analysis of our AI-based platform based on ISO/IEC 25010 quality characteristics.

Finally, to contextualize our contribution, we compare our approach with two distinct categories of applications:

- –

- Mobile Diabetic Foot Early Self-Assessment (M-DFEET): Applications like M-DFEET are designed to guide patients through structured self-examination protocols [59]. The validation of such tools focuses on their usability for a non-expert user and their effectiveness in promoting adherence to a health model. While valuable, these applications typically lack automated image analysis capabilities and are not intended as clinical diagnostic aids. In contrast, our proposal is a clinician-facing tool designed for objective, quantitative analysis, shifting the focus from patient adherence to providing data-driven decision support for medical professionals.

- –

- Remote Maternal Health Monitoring Apps: A significant portion of maternal apps focuses on remote data collection, such as monitoring vital signs (e.g., blood pressure and glucose) or providing educational reminders and facilitating communication [74]. These apps excel at collecting and transmitting discrete data points but do not typically perform complex, on-device analysis of medical imagery. Our tool differs fundamentally by functioning as an advanced analytical instrument. Instead of merely recording data, it executes a sophisticated computational pipeline (segmentation and non-rigid registration) to transform raw, high-dimensional image data into objective, anatomically standardized metrics.

5.5. Limitations

Despite the promising results, our framework presents several limitations that must be addressed before large-scale clinical adoption. First, while deep learning segmentation models (U-Net and ResUNet) achieve high Dice and Jaccard-IoU scores, their performance remains sensitive to acquisition noise, occlusions, and anatomical variability. The limited training dataset, collected with specific thermal cameras (FLIR A320, Teledyne FLIR, Wilsonville, OR, USA, and Fluke TC01A, Fluke Corporation, Everett, WA, USA) under a controlled protocol, restricts generalization to different devices or acquisition settings. Furthermore, although the B-spline-based non-rigid registration strategy successfully adapts a canonical dermatome atlas, its accuracy is inherently constrained by initialization, local distortions, and potential misalignment as small as a few millimeters, which can critically affect dermatome-level temperature attribution and subsequent clinical interpretation.

Also, the mobile deployment, while demonstrating feasibility on Android devices via TensorFlow Lite quantization, remains constrained by hardware resources and user variability. Real-time execution on low-end smartphones or under unstable acquisition conditions may limit robustness and usability. Moreover, the current clinical validation is preliminary, based on a relatively small cohort and evaluation by non-specialized users. Broader trials with anesthesiologists and larger patient populations are required to confirm reliability, usability, and compliance with regulatory standards for medical apps. In this sense, future work should focus on expanding annotated datasets, incorporating domain adaptation to new devices, refining lightweight registration models, and performing prospective clinical studies to establish the platform as a standardized tool for obstetric analgesia monitoring.

6. Conclusions

This work introduced an AI-driven mobile platform that integrates semantic segmentation, non-rigid registration, and temperature-based dermatome analysis to support the non-invasive monitoring of labor epidural analgesia. The proposed pipeline demonstrated competitive segmentation performance in plantar thermogram segmentation, with U-Net and ResUNet achieving Dice Coefficients above 0.94, Jaccard-IoU indices near 0.90, and high specificity, thereby confirming their robustness for clinical-grade image delineation. The non-rigid registration stage enabled the alignment of a canonical dermatome atlas with patient-specific anatomy, ensuring anatomically consistent extraction of regions of interest despite inter-subject variability and postural differences. Importantly, the deployment of the pipeline on a mobile platform validated its feasibility for point-of-care use, with on-device inference operating efficiently under realistic conditions and producing outputs that combine both immediate heatmap visualizations and longitudinal temperature reports. These results collectively underscore the platform’s ability to transform raw thermal acquisitions into reproducible, interpretable, and clinically actionable insights, reducing reliance on subjective visual inspection and offering anesthesiologists a data-driven decision-support tool during obstetric care.

Future work will focus on expanding and diversifying the annotated thermographic dataset, including acquisitions from multiple camera models and under varied clinical protocols, to strengthen generalization. In parallel, lightweight registration methods and adaptive deep learning models will be explored to ensure robust performance on low-resource mobile devices. Crucially, prospective clinical studies with larger patient cohorts and active involvement of anesthesiologists are needed to validate usability, interpretability, and regulatory compliance in real-world labor wards. Moreover, integrating multimodal signals—such as patient vitals or sensor-based feedback—may further enhance the reliability of analgesia monitoring. These directions aim to consolidate the platform as a clinically validated, accessible, and standardized tool for maternal health care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.M.-S., L.M.I.-S., P.A.C.-C., and A.M.Á.-M.; data curation, J.A.M.-S., and L.M.I.-S.; methodology, L.M.I.-S., P.A.C.-C., and A.M.Á.-M.; project administration, A.M.Á.-M., and G.C.-D.; supervision, A.M.Á.-M., and G.C.-D.; resources, J.A.M.-S., L.M.I.-S., and P.A.C.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded under grants provided for the research project ‘Sistema de visión artificial para el monitoreo y seguimiento de efectos analgésicos y anestésicos administrados vía neuroaxial epidural en población obstétrica durante labores de parto para el fortalecimiento de servicios de salud materna del Hospital Universitario de Caldas—SES HUC’, Hermes 57661, funded by Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

Data Availability Statement

The publicly available dataset analyzed in this study can be found at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/lucasiturriago/feet-mamitas (accessed on 1 July 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Fredy Andrés Castaño-Escobar and David Ramírez-Betancourth for their invaluable support in mobile deployment.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Callahan, E.C.; Lee, W.; Aleshi, P.; George, R.B. Modern labor epidural analgesia: Implications for labor outcomes and maternal-fetal health. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 228, S1260–S1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sia, A.; Sng, B.L.; Ramage, S.; Armstrong, S.; Sultan, P. Failed epidural analgesia during labour. In Quick Hits in Obstetric Anesthesia; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 359–364. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, L.; Nelson, S.M.; Kearns, R.J. Epidural analgesia in labor: A narrative review. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022, 159, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyaehie, B.; Galvan, J.M. A standardized algorithm for assessing labor epidural analgesia. Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent. Proc. 2024, 37, 914–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, P.; Liu, Y.; Wu, H.; Wang, H. Non-invasive infrared thermography technology for thermal comfort: A review. Build. Environ. 2024, 248, 111079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Agbigbe, O.; Nigro, N.; Yakobi, G.; Shapiro, J.; Ginosar, Y. Use of high-resolution thermography as a validation measure to confirm epidural anesthesia in mice: A cross-over study. Int. J. Obstet. Anesth. 2021, 46, 102981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topalidou, A.; Markarian, G.; Downe, S. Thermal imaging of the fetus: An empirical feasibility study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0226755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitman, P.A.; Launico, M.V.; Adigun, O.O. Anatomy, Skin, Dermatomes; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kütük, Z.; Algan, G. Semantic segmentation for thermal images: A comparative survey. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 286–295. [Google Scholar]

- Soliz, P.; Duran-Valdez, E.; Saint-Lot, S.; Kurup, A.; Bancroft, A.; Schade, D.S. Functional Thermal Video Imaging of the Plantar Foot for Identifying Biomarkers of Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy. In Proceedings of the 2022 56th Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems, and Computers, Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 31 October–2 November 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 106–110. [Google Scholar]

- Pakarinen, T.; Oksala, N.; Vehkaoja, A. Confounding factors in peripheral thermal recovery time after active cooling. J. Therm. Biol. 2024, 121, 103826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougrine, A.; Harba, R.; Canals, R.; Ledee, R.; Jabloun, M. On the segmentation of plantar foot thermal images with Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 27th European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO), A Coruña, Spain, 2–6 September 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Germi, J.; Mensah-Brown, K.; Chen, H.; Schuster, J. Use of smartphone-integrated infrared thermography to monitor sympathetic dysfunction as a surgical complication. Interdiscip. Neurosurg. 2022, 28, 101475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouallal, D.; Douzi, H.; Harba, R. Diabetic foot thermal image segmentation using Double Encoder-ResUnet (DE-ResUnet). J. Med. Eng. Technol. 2022, 46, 378–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]