Synchrotron Radiation–Excited X-Ray Fluorescence (SR-XRF) Imaging for Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Specimens

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

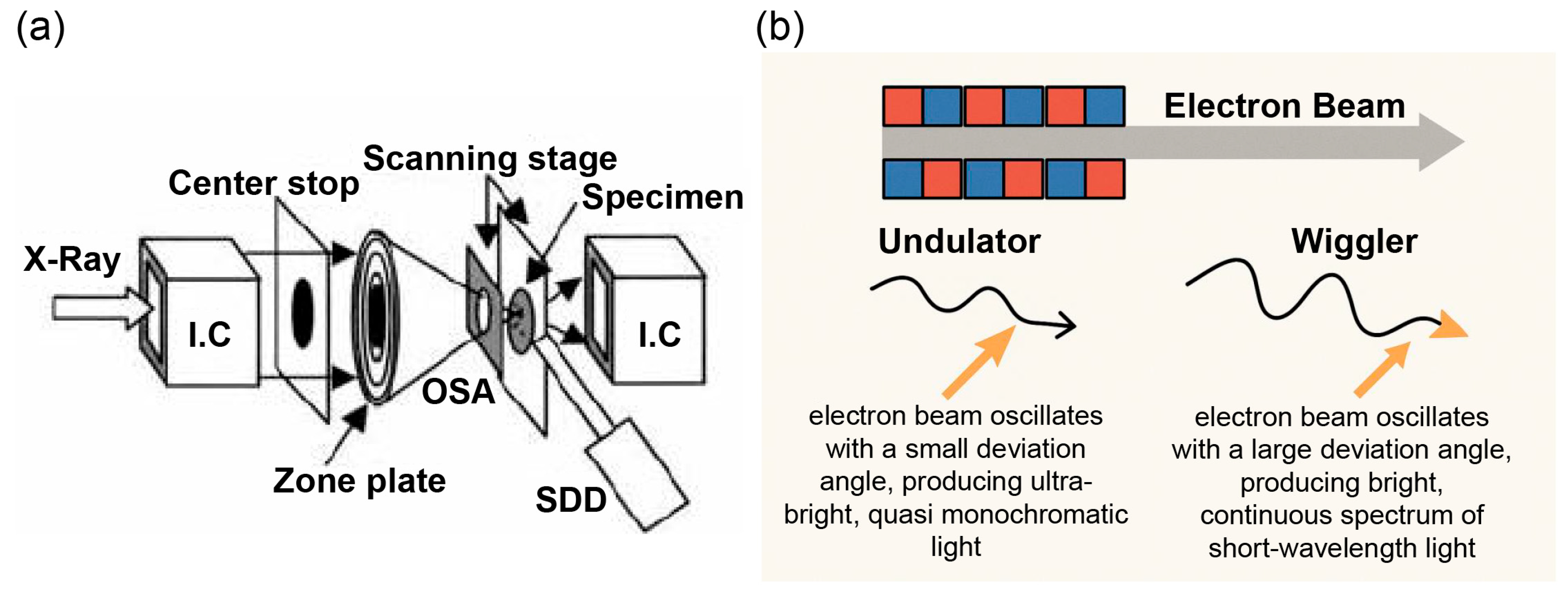

2.2. SR-XRF Imaging Setup

2.3. MRI

2.4. Data Analysis

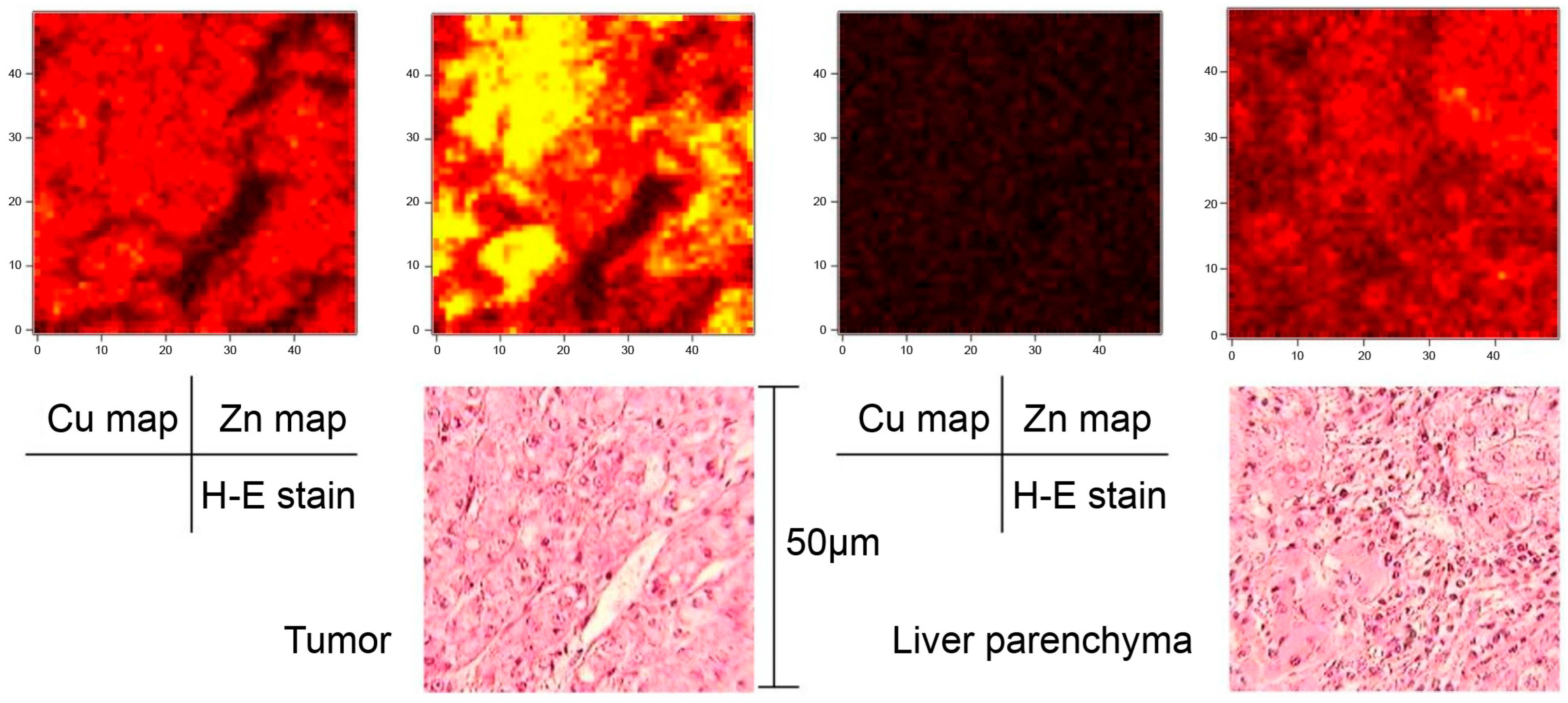

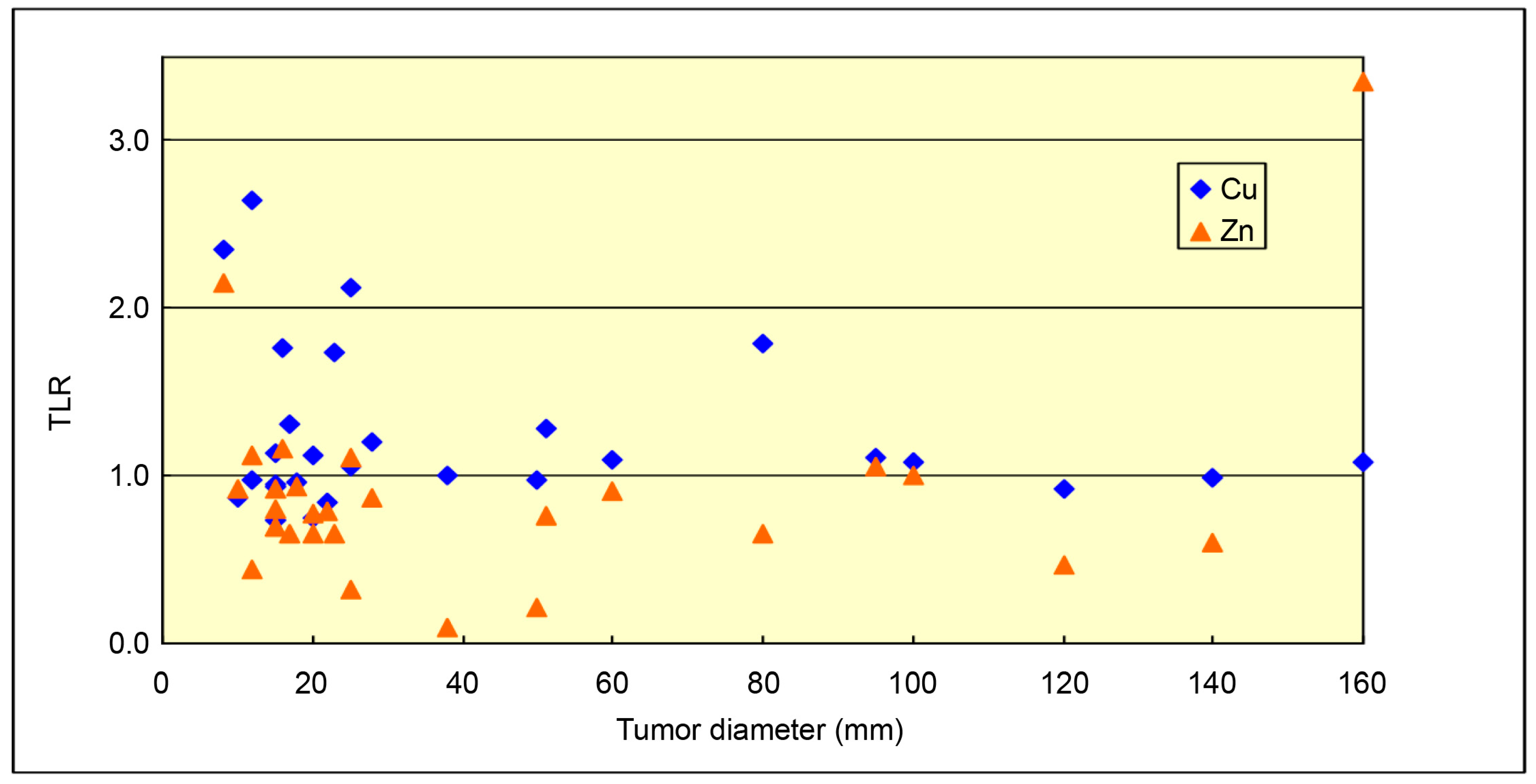

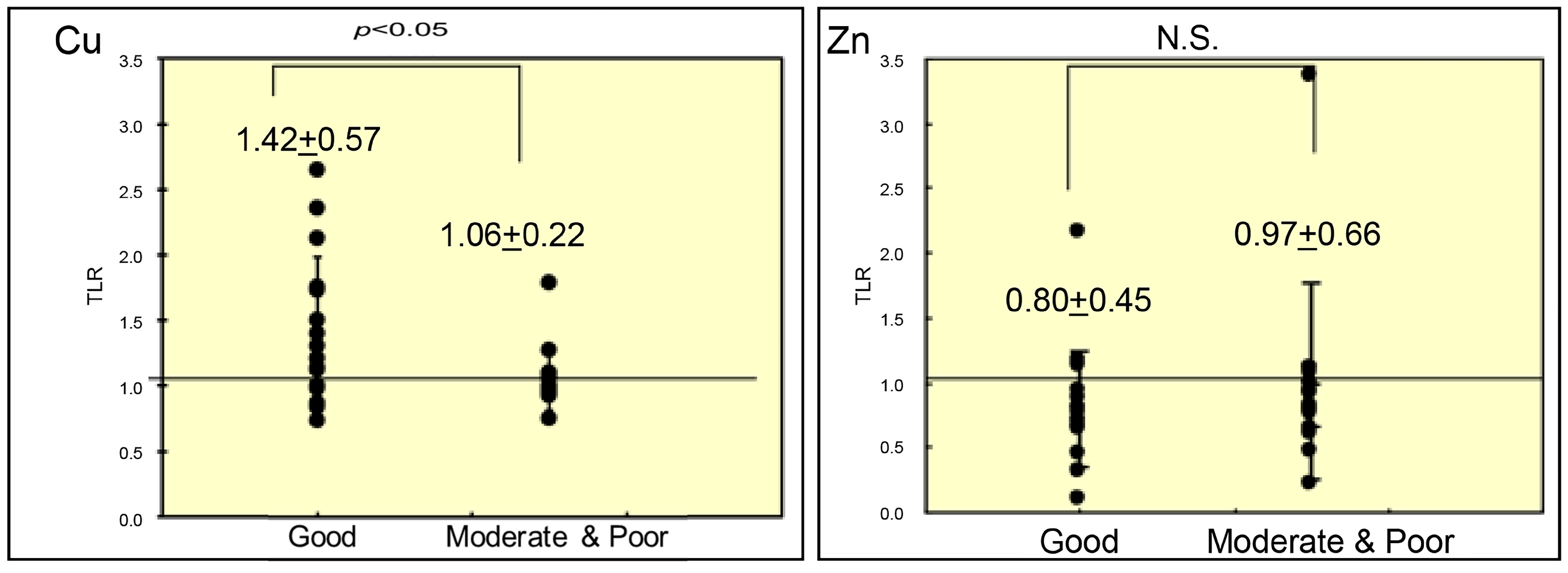

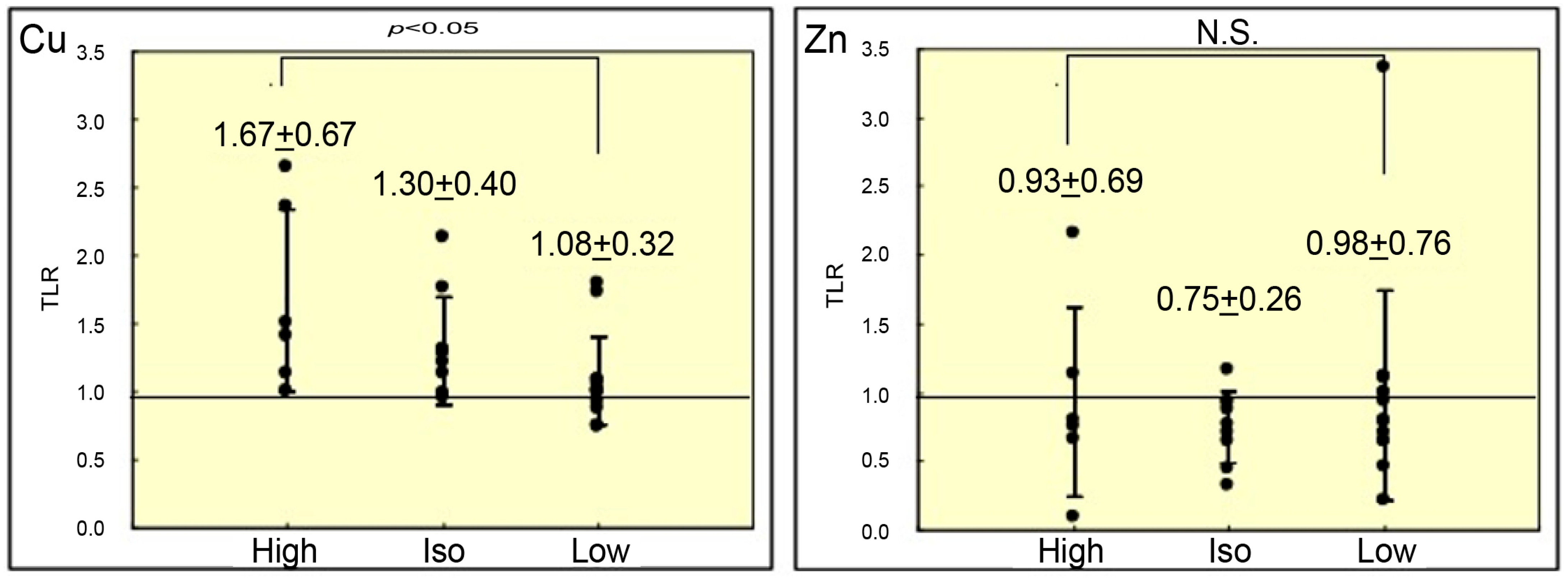

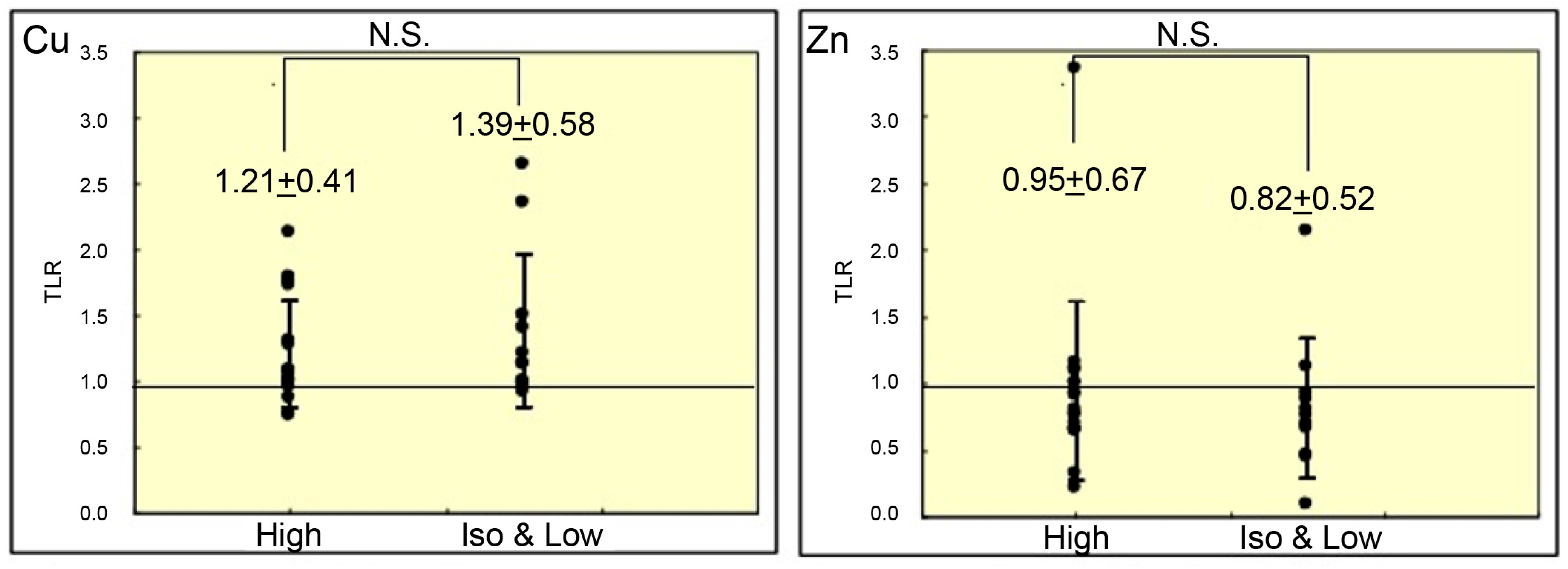

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFP | alpha-fetoprotein |

| HCC | hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HCV | hepatitis C virus |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| OSA | order-sorting aperture |

| PDFF | proton density fat fraction |

| PIXE | particle-induced X-ray emission |

| SDD | silicon drift detector |

| SR-XRF | Synchrotron Radiation–excited X-ray Fluorescence |

| TLR | tumor-to-liver ratio |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Li, Q.; Cao, M.; Lei, L.; Yang, F.; Li, H.; Yan, X.; He, S.; Zhang, S.; Teng, Y.; Xia, C.; et al. Burden of liver cancer: From epidemiology to prevention. Chin. J. Cancer Res. 2022, 34, 554–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidambaranathan-Reghupaty, S.; Fisher, P.B.; Sarkar, D. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): Epidemiology, etiology and molecular classification. Adv. Cancer Res. 2021, 149, 1–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulik, L.; El-Serag, H.B. Epidemiology and management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 477–491.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.; Kim, G.A.; Han, S.; Lee, W.; Chun, S.; Lim, Y.S. Longitudinal assessment of three serum biomarkers to detect very early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2019, 69, 1983–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.X.; Wu, L.H.; Ji, H.; Liu, Q.Q.; Deng, S.Z.; Dou, Q.Y.; Ai, L.; Pan, W.; Zhang, H.M. A novel cuproptosis-related prognostic signature and potential value in HCC immunotherapy. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 1001788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górska, A.; Markiewicz-Gospodarek, A.; Trubalski, M.; Żerebiec, M.; Poleszak, J.; Markiewicz, R. Assessment of the impact of trace essential metals on cancer development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himoto, T.; Masaki, T. Current trends on the involvement of zinc, copper, and selenium in the process of hepatocarcinogenesis. Nutrients 2024, 16, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebara, M.; Fukuda, H.; Kojima, Y.; Morimoto, N.; Yoshikawa, M.; Sugiura, N.; Satoh, T.; Kondo, F.; Yukawa, M.; Matsumoto, T.; et al. Small hepatocellular carcinoma: Relationship of signal intensity to histopathologic findings and metal content of the tumor and surrounding hepatic parenchyma. Radiology 1999, 210, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itai, Y.; Ohtomo, K.; Kokubo, T.; Makita, K.; Okada, Y.; Machida, T.; Yashiro, N. CT and MR imaging of fatty tumors of the liver. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 1987, 11, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, H.; Onitsuka, H.; Kanazawa, Y.; Matsumata, T.; Hayashi, T.; Kaneko, K.; Fukuya, T.; Tateshi, Y.; Adachi, E.; Masuda, K. MR imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma. Correlation of metal content and signal intensity. Acta Radiol. 1995, 36, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, S.; Yasumoto, M.; Kamijo, N.; Suzuki, Y.; Awaji, M.; Takeuchi, A.; Takano, H.; Handa, K. Development of a multilayer Fresnel zone plate for high-energy synchrotron radiation X-rays by DC sputtering deposition. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2002, 9, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamijo, N.; Suzuki, Y.; Awaji, M.; Takeuchi, A.; Takano, H.; Ninomiya, T.; Tamura, S.; Yasumoto, M. Hard X-ray microbeam experiments with a sputtered-sliced Fresnel zone plate and its applications. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2002, 9, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vatamaniuk, M.Z.; Huang, R.; Zhao, Z.; Lei, X.G. SXRF for studying the distribution of trace metals in the pancreas and liver. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dao, E.; Clavijo Jordan, M.V.; Geraki, K.; Martins, A.F.; Chirayil, S.; Sherry, A.D.; Farquharson, M.J. Using micro-synchrotron radiation x-ray fluorescence (µ-SRXRF) for trace metal imaging in the development of MRI contrast agents for prostate cancer imaging. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2022, 74, 127054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, J.B.; Sobin, L.H. Histological Typing of Tumours of the Liver, Biliary Tract and Pancreas; International Histological Classification of Tumors. No. 20; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1978.

- Ebara, M.; Fukuda, H.; Hatano, R.; Saisho, H.; Nagato, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Nakajima, K.; Yukawa, M.; Kondo, F.; Nakayama, A.; et al. Relationship between copper, zinc and metallothionein in hepatocellular carcinoma and its surrounding liver parenchyma. J. Hepatol. 2000, 33, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawata, T.; Nakamura, S.; Nakayama, A.; Fukuda, H.; Ebara, M.; Nagamine, T.; Minami, T.; Sakurai, H. An improved diagnostic method for chronic hepatic disorder: Analyses of metallothionein isoforms and trace metals in the liver of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma as determined by capillary zone electrophoresis and inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2006, 29, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udali, S.; De Santis, D.; Mazzi, F.; Moruzzi, S.; Ruzzenente, A.; Castagna, A.; Pattini, P.; Beschin, G.; Franceschi, A.; Guglielmi, A.; et al. Trace elements status and metallothioneins DNA methylation influence human hepatocellular carcinoma survival rate. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 596040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalny, A.V.; Kushlinskii, N.E.; Korobeinikova, T.V.; Alferov, A.A.; Kuzmin, Y.B.; Kochkina, S.O.; Gordeev, S.S.; Mammadli, Z.Z.; Stilidi, I.S.; Tinkov, A.A. Zinc, copper, copper-to-zinc ratio, and other biometals in blood serum and tumor tissue of patients with colorectal cancer. Biometals 2025, 38, 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebara, M.; Watanabe, S.; Kita, K.; Yoshikawa, M.; Sugiura, N.; Ohto, M.; Kondo, F.; Kondo, Y. MR imaging of small hepatocellular carcinoma: Effect of intratumoral copper content on signal intensity. Radiology 1991, 180, 617–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaki, K.; Sano, N.; Hashiguchi, N.; Yoshida, S.; Nishitani, H. Influence of copper on MRI of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 1997, 7, 478–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakakoshi, T.; Kajiyama, M.; Fujita, N.; Nakayama, N.; Takeichi, N.; Miyasaka, K. Copper concentration in hyperintense hepatocellular carcinomas of Long-Evans cinnamon rats on T1-weighted images. Magn. Reson. Imaging 1997, 15, 689–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, K.; Matsui, O.; Kadoya, M.; Takashima, T.; Kawamori, Y.; Yamahana, T.; Kidani, H.; Hirano, M.; Masuda, S.; Nakanuma, Y. Hepatocellular carcinomas with excessive copper accumulation: CT and MR findings. Radiology 1991, 180, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Sui, Y. Deciphering the synergistic role of tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase 1 and yes-associated protein 1: Catalysts of malignant progression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cytojournal 2024, 21, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Jiang, Q.N. A spatial transcriptome-based perspective on highly variable genes associated with the tumor microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Plus 2023, 5, 1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Li, T.; Ling, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhong, S. Construction of a dual colorimetric fluorescent imprinting polymer hybrid system for the detection of alpha-fetoprotein based on the multi-FRET effect and modeling of its color response mechanism. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2024, 418, 136264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Sun, K.; Dong, J.; Ge, Y.; Liu, H.; Jin, X.; Yu, X.-A. Carrier-free nanoparticles based on natural products trigger dual “synergy and attenuation” for enhanced phototherapy of liver cancer. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 35, 102278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Zeng, J.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Yang, X.; Tian, J.; Zhao, Z.; Du, Y. Multivoid Magnetic Nanoparticles as High-Performance Magnetic Particle Imaging Tracers for Precise Glioma Detection. Bioconjug Chem. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planeta, K.; Setkowicz, Z.; Czyzycki, M.; Janik-Olchawa, N.; Ryszawy, D.; Janeczko, K.; Simon, R.; Baumbach, T.; Chwiej, J. Altered elemental distribution in male rat brain tissue as a predictor of glioblastoma multiforme growth-studies using SR-XRF microscopy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, K.; Lamm, C.; Erb, H.N.; Hillebrandt, J.R. The effects of formalin fixation and tissue embedding of bovine liver on copper, iron, and zinc analysis. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2008, 20, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonta, M.; Török, S.; Hegedus, B.; Döme, B.; Limbeck, A. A comparison of sample preparation strategies for biological tissues and subsequent trace element analysis using LA-ICP-MS. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2017, 409, 1805–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyte, R.M.; Darrah, T.H.; Barrett, E.; O’Connor, T.G.; Olesik, J.W.; Salafia, C.M.; Shah, R.; Love, T.; Miller, R.K. Comparison of trace element concentrations in paired formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded and frozen human placentae. Placenta 2023, 131, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copeland-Hardin, L.; Paunesku, T.; Murley, J.S.; Crentsil, J.; Antipova, O.; Li, L.; Maxey, E.; Jin, Q.; Hooper, D.; Lai, B.; et al. Proof of principle study: Synchrotron X-ray fluorescence microscopy for identification of previously radioactive microparticles and elemental mapping of FFPE tissues. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tsurusaki, M.; Sofue, K.; Kitajima, K.; Murakami, T.; Tanigawa, N. Synchrotron Radiation–Excited X-Ray Fluorescence (SR-XRF) Imaging for Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Specimens. Cancers 2026, 18, 311. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020311

Tsurusaki M, Sofue K, Kitajima K, Murakami T, Tanigawa N. Synchrotron Radiation–Excited X-Ray Fluorescence (SR-XRF) Imaging for Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Specimens. Cancers. 2026; 18(2):311. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020311

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsurusaki, Masakatsu, Keitaro Sofue, Kazuhiro Kitajima, Takamichi Murakami, and Noboru Tanigawa. 2026. "Synchrotron Radiation–Excited X-Ray Fluorescence (SR-XRF) Imaging for Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Specimens" Cancers 18, no. 2: 311. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020311

APA StyleTsurusaki, M., Sofue, K., Kitajima, K., Murakami, T., & Tanigawa, N. (2026). Synchrotron Radiation–Excited X-Ray Fluorescence (SR-XRF) Imaging for Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Specimens. Cancers, 18(2), 311. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020311