Simple Summary

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a clonal hematologic disorder marked by clinical and biological heterogeneity. Natural products (NPs) derived from plants, animals and microorganisms, have been used as healing agents for thousands of years and still today continue to be the most important source of new potential therapeutic agents. To date, several bioactive NPs and semi-synthetic products, such as cytarabine, anthracyclines, midostaurin and melphalan, are currently approved for the treatment of AML. As the treatment of AML remains an ongoing medical challenge, novel NPs and derivatives targeting tumor-related processes have entered preclinical and clinical trials for AML. This review provides a comprehensive summary of NPs and their derivatives approved for the treatment of AML, as well as those which exhibit potential therapeutic abilities for treating AML.

Abstract

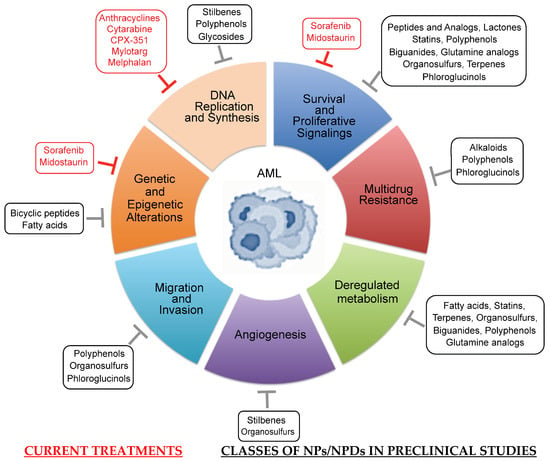

Bioactive natural products (NPs) may play a critical role in cancer progression by targeting nucleic acids and a wide array of proteins, including enzymes. Furthermore, a large number of derivatives (NPDs), including semi-synthetic products and pharmacophores from NPs, have been developed to enhance the solubility and stability of NPs. Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a poor-prognosis hematologic malignancy characterized by the clonal accumulation in the blood and bone marrow of myeloid progenitors with high proliferative capacity, survival and propagation abilities. A number of potential pathways and targets have been identified for development in AML, and include, but are not limited to, Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) and isocitrate dehydrogenases resulting from genetic mutations, BCL2 family members, various signaling kinases and histone deacetylases, as well as tumor-associated antigens (such as CD13, CD33, P-gp). By targeting nucleic acids, FLT3 or CD33, several FDA-approved NPs and NPDs (i.e., cytarabine, anthracyclines, midostaurin, melphalan and calicheamicin linked to anti-CD33) are the major agents of upfront treatment of AML. However, the effective treatment of the disease remains challenging, in part due to the heterogeneity of the disease but also to the involvement of the bone marrow microenvironment and the immune system in favoring leukemic stem cell persistence. This review summarizes the current state of the art, and provides a summary of selected NPs/NPDs which are either entering or have been investigated in preclinical and clinical trials, alone or in combination with current chemotherapy. With multifaceted actions, these biomolecules may target all hallmarks of AML, including multidrug resistance and deregulated metabolism.

1. Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a clinically and genetically heterogeneous hematopoietic cancer characterized by the clonal expansion and accumulation of immature myeloid precursors in the bone marrow (BM) and blood [1]. Leukemia cells are unable to undergo growth arrest, terminal differentiation and death in response to appropriate environmental stimuli [1]. Standard therapy consists of induction with 7 days of cytarabine plus 3 days of an anthracycline (7+3) followed by consolidation with additional chemotherapy or stem-cell transplantation [1]. Today, the approval of alternative strategies includes a new liposomal formulation of cytarabine and daunorubicin (CPX-351), or the combination of venetoclax (a BH3 mimetic that inhibits the survival function of the B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) anti-apoptotic protein) with hypomethylating agents (decitabine, 5-azacytidine) or low-dose of cytarabine [2,3]. Mylotarg (also named gemtuzumab ozogamicin) has been approved in combination with daunorubicin and cytarabine for the treatment of adult patients newly diagnosed with CD33+ AML, and young patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) CD33+ AML [3,4]. Other therapeutic targets have been approved for the treatment of AML patients that carry mutations in the isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH1/IDH2) and Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) genes [2,5]. They include ivosidenib and enasidenib, which target IDH1 and IDH2 proteins, respectively [5], and the FLT3 multikinase inhibitors sorafenib and midostaurin [6,7]. Most of these therapies are still accompanied by adverse effects or favored mutations associated with drug resistance [5,8]. Therefore, the development of new drugs directed against AML-specific targets is still needed to increase the cure rate in AML patients exhibiting chemoresistance and poor outcomes.

Nature is a major source of natural products (NPs) with a large chemical diversity and a wide variety of biological activities for treating various diseases, including cancer [9]. Bioactive NPs originate from bacterial, fungal, plant and marine animal sources [9,10,11]. To date, a large variety of NPs have been identified and include anthracyclines, polyphenols, alkaloids, organosulfur compounds, terpenes, terpenoids and other bioactive compounds such as peptides, proteins, carbohydrates, phospholipids, etc. [9,10,11]. NP-derivatives (NPDs) include semi-synthetic NPs and synthetic compounds based on pharmacophores from NPs [9,12]. Semi-synthetic NPs are derived from biologically active NPs by incorporating synthetic components in their molecular structure to improve or modify their molecular properties, including stability and activity [12]. A pharmacophore consists of a biologically active part of a molecule serving as a model [9]. NPs and NPDs may play a critical role in cancer progression by interfering with tumor cell proliferation, survival, metastasis and chemoresistance, as well as AML-associated angiogenesis [13,14,15]. Today, most chemotherapeutic NPs and derivatives used in the clinic are directed at specific nucleic acids, particular proteins or oncogenic pathways [13]. Their mechanisms of action include disruption of chromatin structure, regulation of the synthesis of certain DNA repair proteins, modulation of intracellular signaling pathways (involving a large array of kinases, transcription factors, BCL2 proteins, etc.) and inhibition of various cytokine and enzymatic activities [13,16,17].

An excellent NPD example comes from the use of cytarabine in AML therapy; it is a semi-synthetic derivative of spongothymidine, a natural molecule isolated in 1945 from a Caribbean sea sponge, Cryptotethia crypta, and endowed with antitumor activity due to its structural similarity to that of nucleic acid thymidines [10]. In 1969, cytarabine was introduced for the treatment of AML, and is still one of the cornerstones in the treatment of this disease [2]. In this review, we present a summary of the applications of NPs and NPDs that have entered the therapeutic armamentarium for AML, and highlight recent developments that are enabling NP/NPD-based drug discovery with promising results in preclinical and clinical trials for the treatment of AML.

2. Roles of Biomarkers in AML Pathogenesis and as Potential Treatment Targets of NPs and NPDs

Human AML cells with abnormally high levels of proliferation and survival transmigrate from BM into peripheral blood and extramedullary organs. BM angiogenesis plays a relevant role in the pathophysiology of AML. In addition to DNA-intercalating NPs/NPDs that block DNA replication and synthesis, a number of AML biomarkers have emerged as targets of NPs and NPDs [18,19]. They are briefly summarized in this section.

2.1. HDACs

HDACs as epigenetic modulators regulate gene expression by deacetylation of lysine residues on histone and non-histone proteins [20]. Class I and class II HDAC genes are abnormally expressed in AML and closely correlated with prognosis [21]. HDAC inhibitors promote cell differentiation, growth arrest, apoptosis, and autophagy in preclinical AML models, and inhibit AML-associated angiogenesis [20].

2.2. Kinases

The Ras/PI3K/AKT/mTOR and Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK (also known as the MAPK/ERK pathway) cross-talk kinase signalings are frequently activated in AML patient blasts [22,23]. Upregulation of these pathways in AML can result from FLT3 and c-Kit mutated tyrosine kinases or Ras GTPases, which are present in 35% to 40% of all AML [22,23,24,25]. Moreover, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway can regulate the expression of anti-apoptotic BCL2 members (Bcl-2, Mcl-1 and Bcl-xL) [26,27]. In consequence, cell survival and proliferation pathways dependent on MAPK, PI3K, AKT and mTOR, as well as NF-κB and STAT3, are deregulated in most cases of AML [28,29,30]. Adhesion to BM stromal cells and migration of AML blasts involve the PI3K signaling [31].

2.3. Transcription Factors

Constitutive NF-κB activation has been reported in approximately 40% to 70% of AML patients, and ensues in part from recurrent genetic alterations of upstream regulators of its pathway [32]. Notably, NF-κB is constitutively active in CD34+ CD38− stem cells (leukemia stem cells/LSCs) from AML patients with French–American–British (FAB) M3/M4/M5 subtypes [33,34]. NF-κB activation is involved in sustaining AML cell proliferation, survival and chemoresistance [30,35]. NF-κB mediates chemoresistance in AML cells, based at least on its ability to stimulate the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins (i.e., Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Mcl-1, XIAP, FLIP), thus enabling AML cells to evade apoptosis and increase proliferation [36,37]. Constitutive STAT3 activation is observed in approximately 50% of newly diagnosed AML, and is associated with adverse prognosis [38]. STAT3 appears essential to the survival of AML LSCs [39]. STAT3 regulates AML cell survival and proliferation by upregulating the expression of its target genes (e.g., c-Myc, cyclin D1, survivin, Bcl-2, Mcl-1) [38,40,41]. STAT3 mediates oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and glutamine uptake in AML cells and LSCs [42].

2.4. Anti-Apoptotic BCL2 Members

Anti-apoptotic BCL2 members (mainly Bcl-2, Mcl-1, Bcl-xL) are frequently overexpressed in AML [43,44]. They are critical for the survival of AML cells and LSCs [44] and associated with relapse of AML, and confer chemotherapy resistance in AML [44,45]. The anti-apoptotic proteins bind and sequester the apoptotic effectors Bax and Bak in an inactive form, and thus act to prevent Bax/Bak-driven apoptosis, thereby maintaining cell survival [46]. High levels of Mcl-1 are found in AML blasts with internal tandem duplications (ITD) of FLT3 [47]. FLT3-ITD upregulates Mcl-1 to promote survival of LSCs via constitutive STAT3 and/or STAT5 signaling [47,48].

2.5. Tumor-Associated Antigens

Aminopeptidase-N (APN)/CD13 preferentially cleaves small neutral amino acids from the N-terminus of small peptides [49]. In AML, CD13 is strongly expressed on LSCs and blasts in all AML FAB subtypes [50,51,52]. CD13 regulates cell proliferation and survival in AML cells, through the activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway and modulation of Bcl-2, Mcl-1 and Bax proteins [53,54]. Our laboratory showed that transmigration of AML cell lines in a Transwell migration assay was neither blocked by bestatin (APN inhibitor) nor anti-CD13 Abs, thus strongly suggesting that surface CD13 is not required for the migration of AML cells.

CD33 is a member of the sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectin family that is involved in cell–cell interactions [55]. CD33 full length and three splice variants of CD33 (that lack exon 2) are present in AML cells [56]. CD33 is highly expressed on a subset of LSCs, on leukemic myeloblasts and AML cells with FLT3 mutations, in most AML patients, regardless of age [55,57,58]. In primary AML cells expressing SYK/ZAP70 kinases, ligation of CD33 mediates induction of death and enhances the cytotoxic effects of cytarabine and idarubicin on leukemic cells [55,59,60].

The presence of various CD44 variants, particularly CD44v6-v10, is observed in primary AML and LSCs [61,62]; their high levels correlate with advanced disease and short survival of patients [61], as well as with relapse and chemotherapy resistance [63,64]. CD44 on AML cells acts as a receptor for the natural glycosaminoglycan hyaluronic acid (HA) and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) [65,66]. CD44 engagement regulates AML cell survival and proliferation (through PI3K/AKT/Mcl-1 pathway) [67,68], mediates AML cell infiltration of BM [69], and reduces AML cell repopulation in serial transplantations by eradication of LSCs [55].

The transmembrane transporter P-glycoprotein/P-gp encoded by the ABCB1 transporter gene (also named multidrug resistance/MDR gene) transports numerous drugs, thus preventing the intracellular accumulation of cytotoxic agents [70]. ABCB1 polymorphisms affect P-gp expression and activity [71]. AML patients, except those with the FAB M5, have a high expression and activity of P-gp [43,72,73]. P-gp is overexpressed in LSCs compared to more differentiated subsets [74]. Overexpression of P-gp is considered to be the primary cause of MDR in patients with AML, often associated with a poor prognosis, and affects the efficacy of treatment and event-free survival [71,72,73,75,76].

Vascular endothelial growth factor-receptor 2 (VEGF-R2) belongs to the tyrosine kinase receptor superfamily, and is the main receptor for VEGF-A (e.g., VEGF165) [77]. Enhanced expression of VEGF and VEGF-R2 in BM correlated with enhanced BM angiogenesis [78,79]. AML cells from BM and blood express high levels of VEGF-R2 and VEGF [79,80,81,82,83]. Overexpression of VEGF and VEGF-R2 has been clinically associated with an aggressive clinical course, chemotherapy resistance and poor prognosis in patients with AML [78,84]. By interacting with VEGF-R2, autocrine VEGF-A supports AML cell survival, proliferation and migration through NF-κB, PI3K/AKT, ERK, HSP90 signaling proteins and Bcl-2 and Mcl-1 anti-apoptotic proteins [79,85,86,87,88].

In addition to VEGF-A, VEGF-C is highly expressed by AML blasts [89,90]. AML patients with high VEGF-C levels at diagnosis show poor biological responses [91,92]. A high VEGF-C expression is related to drug resistance in vitro and in vivo [92]. Binding of VEGF-C to its receptors (e.g., VEGF-R2 and VEGF-R3) favors AML cell proliferation and survival through activation of the endothelin-1/cyclo-oxygenase-2 (ET-1/COX-2)/JNK/AP-1 axis, and upregulating Bcl-2 expression [90,91,93,94]. Accordingly, VEGF-A or VEGF-C stimulation protects AML cells from chemotherapy-induced apoptosis via ET-1/COX-2 pathway and anti-apoptotic proteins [86,93,94,95,96]. Moreover, VEGF can upregulate the expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in primary AML cells [97].

2.6. Soluble Hemoregulators

Blood and BM AML blasts express and release both active and inactive forms of MMP-2 and MMP-9 [81,98,99,100,101]. MMP-2 transcription is mainly regulated by STAT3 [102], while MMP-9 transcription is regulated via NF-κB, AP-1 and SP-1 [103]. Constitutive MMP-2 release is associated with decreased AML cell chemosensitivity [98,99]. Through their enzymatic activities, MMP-2 and MMP-9 likely contribute to the dissemination of AML cells from the BM, and resistance to chemotherapy [104,105,106]. Accordingly, MMP inhibition improves chemotherapy effectiveness in AML models [98,106,107]. In addition, MMP-2 and MMP-9 can be detected as membrane-bound forms on the surface of AML cells [99,107,108]. The binding of MMP-9 to the integrins αLβ2 and αMβ2 on AML cell lines induces their migration [104].

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) exists in two active forms, e.g., the transmembrane form (tmTNF-α) and the secreted form (sTNF-α). Secreted TNF-α is released from tmTNF-α through proteolytic cleavage by ADAM17 (a disintegrin and metalloprotease 17) [109], which is overexpressed on AML cells [52]. Both forms of TNF-α are expressed by AML cells [110,111,112]. A high level of tmTNF-α is correlated with a higher percentage of CD34+ AML cells, extramedullary infiltration, and an adverse risk group [111]. TNF-α enhances AML cell survival and drug resistance by inducing NF-κB activation [113,114], and upregulation of Bcl-2, Mcl-1 and Bcl-xL [36,114]. Alternatively, TNF-α without NF-κB activation can enhance AML cell survival and drug resistance by activating a JNK/AP-1/Mcl-1 signaling [112] or upregulating heme oxygenase-1 expression [115]. NF-κB signaling comprises two independent but interlinked signaling pathways [116]: the canonical or classical pathway mediated by the action of the RelA/p50 subunits, and the non-canonical or alternative pathway that is dependent on activation of the RelB subunit associated with p50 or p52 [116]. The canonical pathway of NF-κB is constitutively active in AML cells [33], while the FLT3/ITD activates the noncanonical NF-κB signaling pathway [117].

3. Current Treatments of AML Using NPs and NPDs

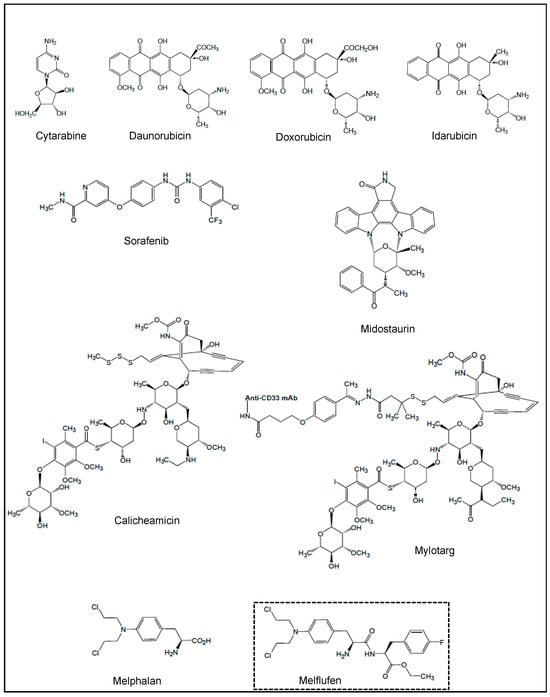

To date, the NPs and NPDs currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of AML include the cytosine derivative cytarabine, the anthracyclines daunorubicin, doxorubicin and idarubicin, the FLT3 inhibitors sorafenib and midostaurin, calicheamicin conjugated to anti-CD33 (mylotarg) and melphalan (Figure 1). In addition, clinical and preclinical trials which are either entering or have evaluated these agents in combination with other drugs are summarized in this section.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of NPs and NPDs used in current treatments of AML, and melflufen, a melphalan derivative.

3.1. Cytarabine, Anthracyclines and CPX-351

Cytarabine (also known as cytosine arabinoside, ara-C) is a semi-synthetic derivative of spongothymidine, a natural molecule isolated from a sponge Cryptotehia crypta; it is an antimetabolite that interferes with DNA synthesis, and inhibits DNA and RNA polymerases and nucleotide reductases needed for DNA synthesis [118]. Anthracyclines are DNA-intercalating agents that block DNA replication (by disrupting the topoisomerase-II-mediated DNA repair) and its subsequent synthesis, therefore causing cell growth arrest and cell death [118]. Daunorubicin (Figure 1), produced by the fermentation of Streptomyces strains, was the first anthracycline discovered in 1963, and received its first marketing authorization in France in 1968 and in the United States in 1974. Daunorubicin was initially used for AML treatment until its semi-synthetic derivatives doxorubicin and idarubicin (Figure 1) were proven more effective by generating free radicals that cause cellular damage [118,119]. The combination and schedule of these molecules for AML, widely known as the “7+3” regimen, remains the backbone of AML standard therapy [120]. Then, the approval of alternative strategies includes a liposomal formulation of cytarabine and daunorubicin (CPX-351) for patients previously exposed to chemotherapy or radiation therapy, or the combination of a low dose of cytarabine with venetoclax [121]. Several phase I/II trials have started to investigate the combination of CPX-351 with other drugs (such as venetoclax, mylotarg, FLT3 inhibitors, etc.) [122,123].

3.2. Sorafenib and Midostaurin

Sorafenib (Figure 1) was built from NP pharmacophores, i.e., a synthetic nicotinamide and a diphenylurea derivative; nicotinamide is found in certain meat and vegetables, while N,N′-diphenyl urea was first isolated from coconut milk in 1955. Sorafenib inhibits various intracellular and cell surface kinases, including FLT3, Raf and VEGF-Rs [124]. Sorafenib, in monotherapy or in combination with conventional chemotherapy, has been used in various settings in AML, including front-line R/R disease, including post-allograft failures and post-transplant maintenance therapy [7,125]. Among new developed FLT3 inhibitors with greater potency [126], midostaurin (Figure 1) is a synthetic derivative of staurosporine, an alkaloid originally isolated from the bacterium Streptomyces staurosporeus. In 2017, midostaurin was approved by the FDA for the treatment of adult patients with newly diagnosed FLT3-mutated AML, in combination with standard cytarabine and daunorubicin induction, and cytarabine consolidation [127,128]. The addition of midostaurin maintenance therapy following allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (alloHCT) may provide clinical benefit in some patients with FLT3-ITD AML [129]. A recent phase I trial of midostaurin and mylotarg used in combination with standard cytarabine and daunorubicin induction has started in patients with newly diagnosed FLT3-mutated AML (NCT03900949, period 2019–2025) [130]. An active phase I/II trial (NCT04982354, period 2022–2030) has been designed to identify the effect of midostaurin combined with CPX-351 as induction and consolidation therapy for patients with high-risk FLT3 mutated AML, and subsequent alloHCT.

3.3. Calicheamicin and Mylotarg

Calicheamicin (Figure 1) is a naturally occurring hydrophobic enediyne that was first isolated from the actinomycete Micromonospora echinospora calichensis. It is a potent DNA-binding cytotoxic agent [131]. To enhance its therapeutic value, a derivative of calicheamicin (i.e., calicheamicin 1,2-dimethyl hydrazine dichloride) has been conjugated with an anti-CD33 mAb, giving an antibody–drug conjugate (ADC) (mylotarg, also known as gemtuzumab ozogamicin) (Figure 1) [131]. After binding to CD33 on the surface of AML cells, mylotarg enters the cell via receptor-mediated endocytosis and releases the lethal drug. Despite the clinical efficacy in R/R AML [132], mylotarg was withdrawn from the market in 2010 due to increased early deaths seen in newly diagnosed AML patients receiving mylotarg plus intensive chemotherapy [4]. In 2017, the FDA regranted approval for mylotarg in combination with daunorubicin and cytarabine for the treatment of adult patients newly diagnosed with CD33+ AML, and young patients with R/R CD33+ AML [3,4]. Several clinical trials have evaluated mylotarg in combination with various therapeutic drugs (i.e., busulfan, cyclophosphamide, azacitidine, all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA), venetoclax, glasdegib (an inhibitor of the Hedgehog pathway), zosuquidar, midostaurin and gilteritinib (a new FLT3 inhibitor) in various AML populations [131,133,134,135,136,137,138,139]. An active phase III in patients with newly diagnosed AML with or without FLT3 mutations (NCT04293562, period 2020–2027)) studies the combination of mylotarg with CPX-351 and/or gilterinitib.

3.4. Melphalan and Melflufen

Melphalan (Figure 1) was synthesized from L-phenylalanine in 1954 [140]. Phenylalanine was first discovered in yellow lupine (Lupinus luteus), and is mainly found in meat, milk, oil seeds and legumes. Melphalan is an alkylating agent, which interferes with the synthesis of DNA and RNA. Patients with R/R AML have a particularly poor outcome, and alloHCT is the only potential curative option for them. To improve alloHCT results in this setting, patients have to receive high-dose myeloablative chemotherapy before alloHCT. The IDA-FLAG (idarubicin-fludarabine/cytarabine (Ara C)/G-CSF) chemotherapy is based on its cytoreductive properties in R/R AML [141]. Furthermore, the IDA-FLAG plus high-dose melphalan-based sequential alloHCT was selected due to its capability in contributing to a high rate of complete response and a low relapse incidence [142,143].

Among developed derivatives of melphalan, designed to increase its activity or selectivity [144], a prodrug of melphalan, the melphalan flufenamide abbreviated melflufen (L-melphalanyl p-L-fluorophenylalanine ethyl ester hydrochloride) was synthesized [145] (Figure 1). With the insertion of a simple peptide bond, the activity of melflufen is directed to APN/CD13-expressing tumor cells. Under the enzymatic action of APN, the peptide bond of melflufen is cleaved, resulting in the release of melphalan, which, due to its hydrophilicity, is trapped inside the cell, and interacts with DNA [145]. Melflufen shows significant anti-leukemia activity in primary AML cells and murine AML xenografts, and inhibits angiogenesis in different preclinical AML models in vitro and in vivo [144,146]. Regardless of FAB subtype, primary AML cells that are resistant to venetoclax exhibit in vitro good sensitivity to melflufen [147].

4. Clinical Trials of AML Using NPs and NPDs

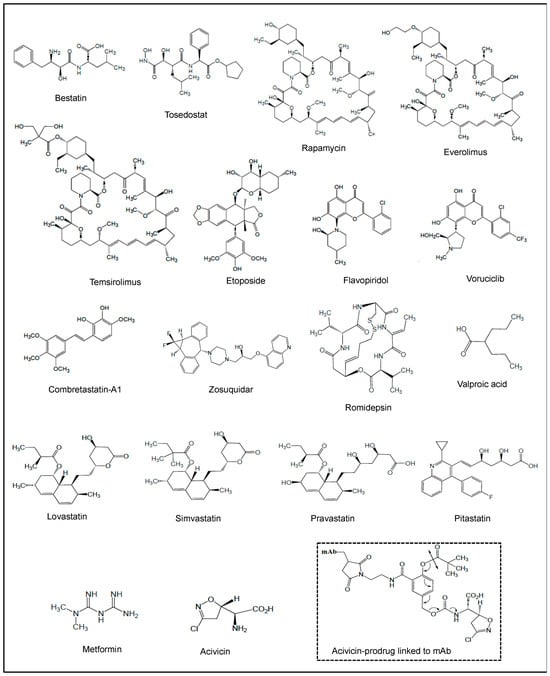

In this section, we discuss the roles of representative NPs and NPDs which have been involved in AML therapeutic purposes. The structures of these molecules are shown in Figure 2, and Table 1 summarizes their actions in clinical trials of AML. These studies have given hints in what ways to steer more effective treatment regimens.

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of NPs and NPDs investigated in clinical trials of AML, and acivicin-prodrug linked to mAb.

4.1. Bestatin and Tosedostat

Bestatin (also known as Ubenimex) is a Phe-Leu-dipeptide (Figure 2) first isolated from Streptomyces olivoreticuli. Bestatin inhibits the proteolytic activity of APN/CD13 in AML cell lines and primary AML blasts [53,54]. Interaction of APN/CD13 with high-dose bestatin induced apoptosis in AML cell lines through the caspase-3, MAPK and glycogen-synthase kinase (GSK)-3β pathways [53]. The combination of cytarabine and bestatin had a synergistic impact in inducing apoptosis of AML cell lines, with Bax expression increased and the expression of Bcl-2, PI3K and AKT decreased [148].

While bestatin has been used for over 35 years in Japan, it has not been approved for any indication in the United States or Europe. In first clinical trials, therapeutic efficacy of bestatin was demonstrated by a prolongation of survival of patients with AML [149,150,151], and in promoting graft versus leukemia effects in patients following alloHCT [152] (Table 1). The effective and safe regimen of cytarabine, aclarubicin (anthracycline produced by Streptomyces galilaeus) and G-CSF (CAG) was widely used in China and Japan for the treatment of patients with new or R/R AML [153]. Bestatin had limited cytotoxicity, and was then used at low doses in combination with the CAG regimen to enhance its antitumor effects [154,155] (Table 1).

In order to overcome the cytotoxic limitation of bestatin, several bestatin derivatives or analogues, as well as bestatin-conjugates, have been developed [156,157,158]. Among them, tosedostat (CHR-2797) (Figure 2) is a synthetic aminopeptidase inhibitor related to bestatin [159]. Tosedostat has been evaluated in clinical trials for the treatment of AML (Table 1). In phase I/II trials, tosedostat showed acceptable toxicity and encouraging efficacy in R/R AML [160,161] (Table 1). When combined with low-dose cytarabine, decitabine or azacitidine, tosedostat was not associated with major toxic effects in newly diagnosed patients with AML [162], as well as in elderly patients with AML [163] (Table 1). A randomized phase II multicenter study (HOVON 103) confirmed the safety of the combination of tosedostat with standard chemotherapy (Table 1). However, phase II randomized studies with a large AML sample size demonstrated that addition of tosedostat to standard chemotherapy or low-dose cytarabine negatively affected the therapeutic outcome of AML patients due to more infection-related deaths [164,165] (Table 1). Using the pharmacophore fusion strategy, a new bestatin–fluorouracil conjugate was developed and provided a basis for the design of bestatin-based conjugates or hybrids [157]. Furthermore, two bestatin–vorinostat hybrids have been developed as potent APN/CD13 and HDAC dual inhibitors, which exhibit antitumor activity in vitro [158,166].

Table 1.

Selected clinical trials using NPs and NPDs in AML.

Table 1.

Selected clinical trials using NPs and NPDs in AML.

| NP/NPD | Class/Activity | Clinical Study |

|---|---|---|

| Bestatin (Ubenimex) (NP) | Phe-Leu-dipeptide/APN inhibitor | Phase I untreated AML [149,150,151] |

| Phase I AML following alloHCT [152] | ||

| Phase I untreated and R/R AML, in combination with cytarabine/aclarubicin/G-CSF [154,155] | ||

| Tosedostat (NPD) | Bestatin peptidomimetic/APN inhibitor | Phase I/II older or relapsed AML (CHR-2797-002) [160] |

| Phase II R/R AML (OPAL, NCT00780598) [161] | ||

| Phase II newly diagnosed AML (NCT01567059), in combination with cytarabine or decitabine [162] | ||

| Phase I/II in elderly R/R AML patients (NCT01636609), in combination with cytarabine or azacitidine [163] | ||

| Phase II very poor risk AML (except FAB M3) (HOVON 103, NL-OMON22002), in combination with daunorubicin/cytarabine | ||

| Phase II in elderly AML patients (Leukemia Working Group of the HOVON/SAKK Cooperative Groups) [164] | ||

| Phase II in untreated elderly patients (ISRCTN40571019), in combination with low-dose cytarabine [165] | ||

| Rapamycin (NP) | Macrocyclic lactone/mTOR inhibitor | Phase I R/R AML or untreated secondary AML, in combination with mitoxantrone/etoposide/cytarabine [167] |

| Phase I R/R and untreated high-risk AML (NCT00780104) | ||

| Phase II (NCT01184898), in combination with mitoxantrone/etoposide/cytarabine [168] | ||

| Phase I newly diagnosed AML (NCT01822015), in combination with cytarabine/daunorubucin [169] | ||

| Temsirolimus (NPD) | Macrocyclic lactone/mTOR inhibitor | Phase II for elderly AML patients (NCT007755903), in combination with clofarabine [170] |

| Everolimus (NPD) | Macrocyclic lactone/mTOR inhibitor | Phase Ib first relapse AML (NCT01074086), in combination with cytarabine/daunorubicin [171] |

| Phase Ib/II R/R AML (ACTRN12610001031055), in combination with cytarabine [172] | ||

| Phase I AML (UK NCRI AML17 trial), in combination with consolidation high-dose cytarabine [173,174] | ||

| Etoposide (NPD) | Glycoside/ topoisomerase II inhibitor | Phase I R/R AML, in combination with cytarabine [175] |

| Phase I R/R AML, in combination with fludarabine/cytarabine [176] | ||

| Phase I R/R AML, in combination with mitoxantrone/cytarabine [177] | ||

| Phase I/II untreated and R/R AML (NCT02921061), in combination with mitoxantrone/cytarabine following priming with decitabine [178] | ||

| Phase I R/R AML, in combination with fludarabine/cytarabine/G-CSF [179] | ||

| Phase I p53 mutated AML (ChiCTR-INR-16009337) in combination with decitabine [180,181] | ||

| Flavopiridol (NPD) | Flavone/kinase inhibitor | Phase I poor-risk AML (NCT00470197), in combination with cytarabine/mitoxantrone [182] |

| Phase I AML (NCT00278330), in combination with vorinostat [183] | ||

| Phase II poor-risk AML (NCT00795002), in combination with cytarabine/mitoxantrone [184,185,186] | ||

| Phase I newly diagnosed high-risk AML (NCT03298984), Phase II newly diagnosed AML (NCT00407966), Phase I R/R AML (NCT03563560), in combination with cytarabine/mitoxantrone or cytarabine/daunorubicin [187,188,189] | ||

| Phase II R/R AML (NCT00634244), in combination with cytarabine/mitoxantrone or sirolimus/mitoxantrone/etoposide [190] | ||

| Phase II Mcl-1-dependent-R/R AML (NCT02520011), in combination with cytarabine/mitoxantrone [191] | ||

| Phase II AML (NCT01349972), in combination with cytarabine/daunorubicin/mitoxantrone | ||

| Phase I AML (NCT00064285), in combination with imatinib | ||

| Phase Ib R/R AML (NCT03441555), in combination with venetoclax [192] | ||

| Phase II R/R AML (NCT03969420, active trial), in combination with venetoclax | ||

| Voruciclib (NPD) | Flavone/kinase inhibitor | Phase I R/R AML (NCT03547115), in combination with venetoclax [193] |

| Combretastatin-A1 (NP) | Stilbene/DNA-damaging agent | Phase I/Ia R/R AML (NCT01085656) [194,195] |

| Phase Ib R/R AML (NCT02576301), in combination with cytarabine [196,197] | ||

| Zosuquidar (NPD) | Quinoline alkaloid/P-gp inhibitor | Phase I newly and relapsed AML, in combination with cytarabine/daunorubicin [198] |

| Phase I in untreated AML, in combination with cytarabine/daunorubicin [199] | ||

| Phase III in untreated elderly AML patients (NCT00046930), in combination with cytarabine/daunorubicin [200] | ||

| Phase I/II in untreated elderly AML patients (NCT00129168), in combination with cytarabine/daunorubicin [201] | ||

| Phase I/II untreated AML (NCT00233909), in combination with mylotarg [137] | ||

| Romidepsin (NP) | Bicyclic peptide/HDAC inhibitor | Phase I newly and relapsed AML (approval from The Ohio State University Institutional Review Board) [202] |

| Phase I/II R/R AML (NCT00062075), in combination with azacytidine [203,204] | ||

| Valproic acid (NPD) | Fatty acid/HDAC inhibitor | Phase I/II/III AML, in combination with ATRA [205,206,207,208] |

| Phase I/II AML (NCT00414310), Phase I R/R AML (NCT00079378), Phase I AML ((NCI U01 CA 76576-05) | ||

| Phase II AML (NCT01305499), in combination with decitabine [209,210,211] | ||

| Phase I/II relapsed AML after alloHCT (NCT01369368) | ||

| Phase II AML/MDS (NCT00382590), in combination with 5-azacytidine versus low-dose cytarabine | ||

| Phase II AML, in combination with low-dose cytarabine [212] | ||

| Phase II AML, in combination with ATRA and 5-azacytidine (NCT00326170) [213], (NCT00339196) [214] | ||

| Phase I AML (NCT00175812), in combination with ATRA and theophylline [215,216] | ||

| Phase I/II AML (NCT00995332), in combination with ATRA and low-dose cytarabine [217] | ||

| Phase I/II AML (NCT00867672), in combination with ATRA and decitabine [218,219] | ||

| Phase III in old AML patients (NCT00151255), with standard induction (cytarabine/idarubicin), and consolidation (cytarabine/mitoxantrone) [220] | ||

| Phase II high risk AML/MDS (NCT02124174), in combination with 5-azacytidine as maintenance therapy post alloHCT [221] | ||

| Lovastatin (NP) | Statin/lipid-lowering drug | Phase I/II R/R AML (NCT NCT00583102), with high-dose cytarabine [222] |

| Pravastatin (NPD) | Statin/lipid-lowering drug | Phase I AML (MDACC IRB, protocol no. 2004-0185), in combination with idarubicin and high-dose cytarabine [223] |

| Phase II R/R AML (NCT00840177), in combination with idarubicin and cytarabine [224] | ||

| Phase I/II R/R AML (NCT01342887), in combination with etoposide, cyclosporine and mitoxantrone [225] | ||

| Pitavastatin (NPD) | Statin/lipid-lowering drug | Phase I AML (NCT04512105), in combination with venetoclax [226] |

| Metformin (NP) | Biguanide/mitochondrial GPDH inhibitor | Retrospective studies with diabetic AML patients [227,228] Phase I R/R AML (NCT01849276), in combination with cytarabine |

| Acivicin (NP) | Glutamine analog/γ-GT inhibitor | Phase I/II R/R AML [229] |

AlloHCT, allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation; APN, aminopeptidase-N; ATRA, all-trans retinoic acid; γ-GT, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase; G-CSF, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor; HDAC, histone deacetylase; NP, natural product; NPD, natural product derivative; R/R, relapsed/refractory.

4.2. Rapamycin, Temsirolimus and Everolimus

Rapamycin (also known as sirolimus) (Figure 2) was first isolated from a filamentous bacterium Streptomyces hygroscopicus. Its mechanism of action uncovers the inhibition of mTOR kinase that regulates mRNA translation and protein synthesis, an essential step in cell growth, proliferation and survival [230]. Rapamycin markedly impaired the clonogenic properties of fresh AML cells while sparing normal hematopoietic progenitors [231]. In vitro studies showed that rapamycin inhibited the proliferation of AML cells and induced apoptosis associated with the inhibition of the mTOR, 4E-BP1 and p70S6K pathways, and VEGF expression [231,232,233,234].

Initial clinical studies showed that rapamycin was well-tolerated in patients with refractory AML [235], and confirmed the feasibility of combining rapamycin and induction chemotherapy in R/R and untreated high-risk AML [167,168] (Table 1). Recently, a phase I trial of rapamycin with conventional “7+3” chemotherapy in patients with newly diagnosed AML showed it was a well-tolerated and safe regimen [169] (Table 1). Furthermore, two new rapamycin analogues were developed, e.g., temsirolimus, which is a soluble ester of rapamycin [236], and everolimus, which is a hydroxyethyl ether of rapamycin [237] (Figure 2). Both derivatives inhibit the growth of AML cell lines and VEGF expression [232]. Furthermore, they inhibit more efficiently mTOR signaling and AKT activation in primary AML cells [238]. They enhance chemotherapy response in bulk and AML stem populations [231,239]. The combination of temsirolimus with clofarabine (a nucleoside analogue) displays synergistic cytotoxic effects against AML cells, translated by growth arrest, apoptosis and autophagy (associated with inactivation of AKT and mTORC1 downstream targets) [240]. Three clinical trials provided evidence that temsirolimus and everolimus can enhance chemosensitivity in relapsed AML patients [170,171,172] (Table 1). However, one clinical trial performed on a large cohort of AML patients suggested that the addition of everolimus to consolidation therapy provided no benefit and was terminated due to immunosuppressive effects of everolimus leading to infections [173,174] (Table 1).

4.3. Etoposide

Etoposide (also known as VP-16) (Figure 2) is a semi-synthetic glycoside derivative of podophyllotoxin which is a non-alkaloid compound extracted from the rhizomes and roots of certain Podophyllum species. Etoposide inhibits topoisomerase II, which is responsible for rewinding broken DNA strands [241]. The in vitro pro-apoptotic effect of etoposide related to caspase-3-mediated Bcl-2 cleavage and topoisomerase II inhibition was demonstrated in AML cell lines and primary AML blasts [242,243,244,245,246,247]. Synergism with doxorubicin, rapamycin and other drugs has been demonstrated in vitro and in AML murine xenografts [239].

In initial clinical trials, etoposide, as a single agent, was active in R/R AML, and gave complete response rates of 10% to 25% [248]. Etoposide was safely combined with cytarabine, anthracyclines (daunorubicin, doxorubicin, idarubicin), mitoxantronerapamycin, etc., inducing remission rates of 20% to 60% in R/R AML [249]. Following clinical studies showed encouraging results, with a high percentage of new and R/R AML patients achieving complete remission [175,176] (Table 1). The combination of mitoxantrone, etoposide and cytarabine can induce deep complete remission and is an effective bridge therapy to alloHCT in R/R AML patients [177] (Table 1). Moreover, the fludarabine, high-dose cytarabine, G-CSF and etoposide regimen showed a moderate toxicity profile in heavily pretreated R/R AML patients enabling stem cell consolidation [179] (Table 1). However, a phase I/II study of mitoxantrone, etoposide and cytarabine following priming with decitabine (an analogue of cytarabine) in patients with R/R AML showed no evidence that this combination was substantially better than other cytarabine-based regimens currently used for R/R AML [178] (Table 1). More recently, combinations of decitabine and etoposide regimens appeared relatively safe and tolerable in elderly patients with p53 mutated AML [180,181] (Table 1).

4.4. Flavopiridol and Voruciclib

Flavopiridol (also known as alvocidib) (Figure 2) is a semi-synthetic flavone derived from rohitukine present in the Indian tree Dysoxylum binectariferum. Initially described as a potent inhibitor of multi-serine threonine cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) by binding to the ATP-binding domain of CDKs [250], flavopiridol lacks absolute specificity since it can inhibit the activity of other kinases (including AKT, MAPKS, JNK, PKC, and IκBα kinase) and MMP-9, as well as the expression of anti-apoptotic BCL2 proteins [250,251]. Flavopiridol induced apoptosis in various AML cell lines and BM AML blasts, associated with downregulation of Mcl-1 and Bcl-2 [252,253,254,255,256,257].

Flavopiridol was the first CDK inhibitor to enter clinical trials for the treatment of solid tumors. An initial phase I clinical study of flavopiridol in R/R AML patients showed a modest anti-leukemic activity [258,259]. Correlative pharmacodynamic studies in AML BM blasts demonstrate that flavopiridol induced suppression of tumor-associated genes (encoding Mcl-1, Bcl-2, VEGF, E2F1, STAT3, cyclin D1 and RNA polymerase II), and increased the cytotoxic effects of cytarabine [182,258,260,261,262]. In phase I/II clinical trials, flavopiridol showed a significant clinical activity in AML (R/R and newly diagnosed non-favorable risk AML patients), when combined in various sequential chemotherapy regimens (daunorubicin, cytarabine, imatinib, mitoxantrone, vorinostat, sirolimus, etoposide) [182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,250] (Table 1). The best rate of complete remission or remission with incomplete hematologic recovery was seen with flavopiridol combined with the “7+3” conventional therapy [187,188,189]. While a phase Ib of flavopiridol combined with venetoclax for R/R AML showed no increase in efficacy across all cohorts compared to what was previously observed with each agent alone [192] (Table 1), an ongoing phase II R/R AML is still evaluating, in combination, flavopiridol plus venetoclax in R/R AML (Table 1). New synthetic derivatives of flavopiridol, including voruciclib (Figure 2), exhibited improved CDK-inhibitory activity, efficiently induced apoptosis of AML cells and differentiation of LSCs and prevented AML progression in various cellular and animal models [250,263]. In a phase I trial, voruciclib on intermittent dosing was well-tolerated in R/R AML patients [264], and, combined with venetoclax, achieved objective responses in patients with AML [193] (Table 1). Liposomal formulation of flavopiridol was well-tolerated in mice, led to improved plasma concentrations and increased elimination phase half-time relative to flavopiridol alone [265]. This suggests that further increases in flavopiridol retention could result in its improved therapeutic activity.

4.5. Combretastatin-A1

Cis-combretastatin-A1 (Figure 2) is a stilbene found in the Eastern Cape South African Bushwillow Combretum caffrum. As an anti-angiogenic agent, it destabilizes tubulin, which induces the death of endothelial cells [266]. Cis-combretastatin-A1 diphosphate is a water-soluble prodrug of cis-combretastatin-A1. In vitro, combretastatin-A1 diphosphate counteracted the chemoprotective effects of BM endothelial cells on cytarabine-treated AML cells and induced apoptosis in primary AML cells [267]. The combination of combretastatin-A1 with cytarabine in xenografted human AML models was more effective than either drug alone [268].

In phase I trials in patients with R/R AML, combretastatin-A1 diphosphate showed a manageable safety profile but only a modest anti-leukemic activity as a single agent [194,195] (Table 1). In a multicenter Phase Ib study, combretastatin-A1 diphosphate and cytarabine administered in combination in patients with R/R AML exhibited a manageable toxicity and a promising benefit to risk profile in relapsed AML patients, with a 19% overall response rate, and a considerably longer overall survival for those who obtained complete remission [196,197] (Table 1).

4.6. Zosuquidar

Zosuquidar (LY335979) is a synthetic difluorocyclopropyl quinoline alkaloid (Figure 2). The quinoline ring occurs in several NPs found mainly in Rutaceae plants (Cinchona Alkaloids), which display a broad range of biological activities, including inhibition of P-gp efflux pump and other related pumps responsible for the development of resistance [269]. Zosuquidar is a highly specific P-gp inhibitor [270]. Compiled in vitro studies demonstrated that zosuquidar restored drug sensitivity in P-gp+ AML cell lines, and enhanced the cytotoxicity of anthracyclines (daunorubicin, idarubicin, mitoxantrone) and mylotarg in the majority of primary AML blasts with active P-gp [271,272].

Early clinical studies of zosuquidar given in combination with anthracyclines demonstrated acceptable safety profiles and minimal pharmacokinetic interactions with doxorubicin or daunorubicin [273,274]. Phase I trials have shown that zosuquidar can be given safely to the AML patients in combination with daunorubicin and cytarabine [198,199] (Table 1). In a randomized phase III clinical trial, the combination zosuquidar/daunorubicin/cytarabine did not improve the outcome of elderly patients with newly diagnosed AML [200] (Table 1). However, an open-label, phase I/II multicenter dose escalation study of zosuquidar, combined with daunorubicin and cytarabine in old patients with untreated AML, provided evidence of zosuquidar efficacy with the 72 h continuous intravenous infusion [201] (Table 1). A clinical phase I/II trial in R/R AML evidenced that patients with P-gp+/CD33+ leukemic blasts were effectively targeted by cotherapy with zosuquidar and mylotarg [137] (Table 1).

4.7. Romidepsin

Romidepsin (Figure 2) is a natural bicyclic peptide present in cultures of Chromobacterium violaceum, a Gram-negative bacterium isolated from a Japanese soil sample. It is a natural HDAC inhibitor which acts as a prodrug, as its disulfide bridge is reduced by glutathione on uptake into the cell, thus allowing the free thiol groups to interact with Zn2+ ions in the active site of class I and II HDAC enzymes [275,276]. HDAC inhibitors, including romidepsin, promoted cell death, apoptosis, autophagy, or cell cycle arrest in preclinical AML models, yet these drugs seemed to be more effective in combination with other drugs than when used as monotherapies [20,204,276].

Romidepsin was first approved for the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (TCL) in 2009 by the FDA [275]. Clinical trials in AML with romidepsin had encouraging outcomes in early phase studies [202] (Table 1). In the phase I/II ROMAZA trial, the combination of romidepsin and azacitidine therapy was well-tolerated and clinically active in patients with newly diagnosed R/R AML who are ineligible for conventional chemotherapy [203,204] (Table 1). However, toxicity and tolerability need to be considered in addition to response rate, especially in old patients with AML [20]. Recently, a first-in-class polymer nanoparticle of romidepsin has been developed that exhibits superior pharmacologic properties and superior anti-tumor efficacy in murine xenograft TCL models [277]. The clinical value of nanoromidepsin in AML has yet to be assessed.

4.8. Valproic Acid

Valproic acid (Figure 2) is a synthetic molecule derived from valeric acid found naturally in an herbaceous perennial flowering plant, Valeriana. This short-chain fatty acid is used as an anticonvulsant to treat epilepsy and bipolar disorder, and to prevent migraine headaches [278]. Valproic acid acts as an HDAC inhibitor by binding to the enzymatic site of HDACs [279]. This molecule induced differentiation and apoptosis in various AML cell lines and primary AML cells expressing P-gp and/or MDR-1, either alone or in combination with agents such as cytarabine, ATRA, and venetoclax [217,280,281,282]. It inhibits HDAC-1 activity in AML blasts, and this effect is accompanied by enhanced levels of histone H3/H4 acetylation [283,284]. Valproic acid increases CAR-T cell toxicity against mouse AML models [285].

A number of clinical trials for AML have been performed on the effects of valproic acid in conjunction with various drugs (Table 1). In phases II/III, valproic acid appears to be a safe and effective treatment option for AML patients, particularly when used in conjunction with ATRA and DNA-hypomethylating drugs (cytarabine, 5-azacytidine) [205,206,207,208,209,210,211,212,213,214,215,216,218,219,220,221,281] (Table 1). Serum samples collected from AML patients included in a previously clinical phase I/II study [217] showed that valproic treatment significantly altered the levels of the amino acid (AA) and lipid metabolites, which may contribute to the antileukemic effects of valproic acid [286].

4.9. Lovastatin, Simvastatin, Pravastatin and Pitavastatin

Lovastatin (Figure 2) is a statin initially isolated from a strain of a mold, Aspergillus terreus. As a specific inhibitor of hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase, lovastatin blocks cellular cholesterol synthesis, and hence is extensively used to treat hypercholesterolemia [287]. Lovastatin and its synthetic analogues (such as simvastatin, pravastatin and pitavastatin) (Figure 2) were approved for marketing by the FDA. Lovastatin was shown to inhibit proliferation and colony formation in primary AML cells [288,289,290], as well as to induce apoptosis in AML cells [291,292,293]. Statin-mediated apoptosis is accompanied by the downregulation of Bcl-2 and Raf/MEK/ERK signalings and geranylgeranylation suppression, resulting in upregulation of the pro-apoptotic protein PUMA [289,292,294,295]. Lovastatin enhanced the cytotoxic effect of cytarabine in K-562 cells by downregulating MAPK activity and preventing cytarabine-induced MAPK activation [222]. In line, the majority of CD34+ AML primary blasts were affected by lovastatin treatment, which was potentiated when combined with cytarabine and daunorubicin [295]. In AML cell lines, the combination of simvastatin and venetoclax induced more death than either treatment alone [296].

A dose escalation phase I/II trial of lovastatin with high-dose cytarabine for R/R AML was terminated due to slow accrual [222] (Table 1). The combination of pravastatin with cytarabine and idarubicin was successful in two out of three clinical trials for the treatment of newly-diagnosed and relapsed AML patients [223,224,297]. In an initial phase I study, addition of pravastatin to idarubicin and high-dose cytarabine was safe in newly diagnosed and salvage patients with unfavorable or intermediate prognosis cytogenetics [223] (Table 1). In this study, total and LDL (low-density lipoprotein) cholesterol levels decreased in nearly all patients [223]. It has to be pointed out that following exposure to cytotoxic agents, AML blasts elevate cellular cholesterol in a defensive adaptation that increases chemoresistance. Then, inhibition of cholesterol synthesis and uptake could sensitize AML blasts to chemotherapy. A phase II trial of high-dose pravastatin given in combination with idarubicin and cytarabine demonstrated a 30% response rate in untreated and R/R patients with AML, suggesting that targeting the cholesterol pathway may have therapeutic benefit in AML [224] (Table 1). In a phase I/II study, pravastatin with etoposide, cyclosporine and mitoxantrone had adverse effects in patients with R/R AML [225] (Table 1). A phase I study adding pitavastatin to venetoclax-based therapy in new patients with AML showed that pitavastatin was well-tolerated, and toxicities were similar to those of venetoclax-based therapy in standard clinical practice [226] (Table 1).

4.10. Metformin

Metformin (Figure 2) is a natural biguanide initially found in Galega officinalis (or plant goat’s rue). It is an oral anti-diabetic drug used to treat people with type 2 diabetes at the early stages [298]. Since, the benefits of metformin have been observed for other diseases including cancers. Metformin inhibits cell proliferation in AML cell lines and reduces AML propagation in mice models through the activation of the adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway, resulting in the inhibition of downstream mTOR signaling and mitochondrial OXPHOS [299,300,301,302,303]. High-dose metformin promotes AML cell apoptosis in an AMPK-independent manner [304,305,306,307]. When combined with cytarabine or other drugs (i.e., ATRA, paclitaxel, venetoclax, idarubicin, gilteritinib, etc.), metformin may have additive or synergistic cytotoxic effects through AMPK activation, and modulation of distinct signaling pathways (mTORC1/P70S6K; OXPHOS; STAT5; NF-κB; MAP/MAPK; MEK/ERK; Mcl-1, Bcl-xL; FLT3/STAT5/ERK/mTOR) [304,305,306,307,308,309,310,311,312,313,314,315].

Two retrospective studies with diabetic AML patients taking metformin showed no metformin benefit [227,228] (Table 1). One phase I clinical trial aimed to test metformin in combination with cytarabine for the treatment of R/R AML. Unfortunately, the study was terminated due to the accrual of only two patients (Table 1).

4.11. Acivicin and Acivicin-Prodrug

Acivicin (Figure 2) is a natural structural analogue of glutamine, originally isolated as a fermentation product of Streptomyces sveceus. It is a glutamine antimetabolite and a potent inhibitor of the enzymatic activity of γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GT) activity [316]. The γ-GT is strongly expressed on HL-60 and U937 leukemic cell lines [317,318,319,320,321,322], and on blasts from blood in all AML FAB subtypes (with highest surface activity observed in the FAB M5 group) [317,323,324]. Acivicin inhibited the proliferation of HL-60 and U937 cells and induced their differentiation toward macrophages associated with H2O2 inhibition and NF-κB activation [318,319,320,321,325]. High-dose acivin induced apoptosis in these cells through H2O2 inhibition [322,326].

While several phase I studies of acivicin were performed in patients with advanced solid malignancies [327,328], only one phase I clinical trial was conducted, with six patients with R/R AML [229] (Table 1). These clinical trials demonstrated a high rate of severe, albeit reversible, central nervous system toxicity [229,327,328]. A new acivicin prodrug designed for AML-targeted delivery was developed (Figure 2) to target an inactive acivicin precursor to tumor cells when linked to a mAb, which recognizes a tumor-specific antigen at the surface of AML cells. Prodrug cleavage by plasmatic esterases then restored the acivicin’s inhibitory activity against γ-GT and its cytotoxicity towards the HL-60 cell model [329,330]. This suggests that a prodrug-antibody conjugate might be used to target acivicin to AML cells.

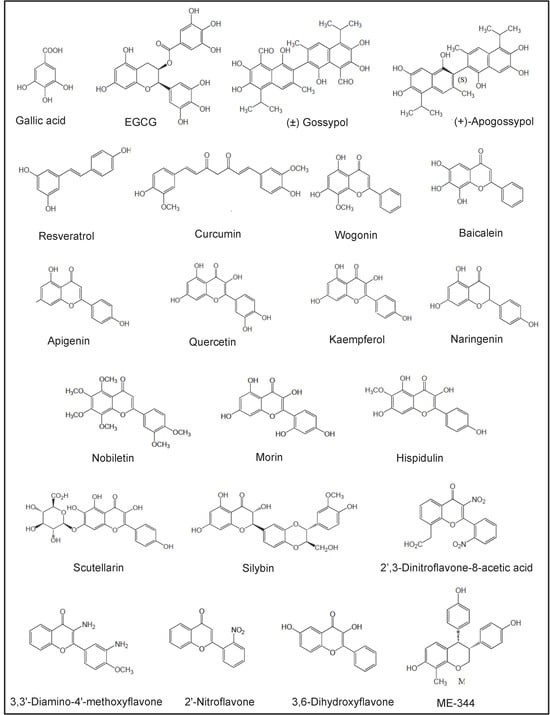

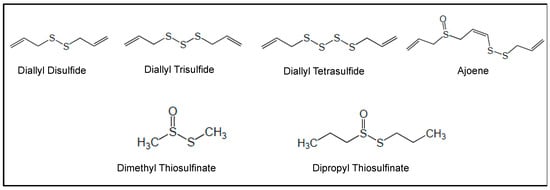

5. Preclinical Studies of AML with Selected NPs and NPDs

In vitro and in vivo studies carried out with a number of NPs and NPDs (Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 and Table 2) have been performed both in AML models and primary AML samples. Their antitumor effects still need confirmation by clinical trials.

Figure 3.

Chemical structures of polyphenols investigated in preclinical studies.

Figure 4.

Chemical structures of organosulfur compounds investigated in preclinical studies.

Figure 5.

Chemical structures of terpenes investigated in preclinical studies.

Figure 6.

Chemical structures of hyperforin and derivatives investigated in preclinical studies.

Table 2.

Selected in vitro and in vivo studies of selected NPs and NPDs in AML.

5.1. Polyphenols

Polyphenols fall into two main categories, i.e., flavonoids (including flavones, flavonols, flavans, isoflavones, flavanones, catechins, chalcones and anthocyanidins) and non-flavonoids (including stilbenes, curcuminoids, phenolic acids, xanthones, anthraquinones, lignans, coumarin and its derivatives) [438,439,440]. Flavonoids are derived from phenylalanine and initially involve the biosynthesis of 4-coumaroyl-CoA. They are omnipresent in the daily food intake [441,442].

5.1.1. Gallic Acid

Gallic acid (Figure 3) is a polyhydroxyl phenolic compound abundantly found in fruits, grapes, vegetables and green tea. It demonstrated significant growth inhibitory and pro-apoptotic effects in various AML cell lines [331,332,333,334,335,336]. Gallic acid induced apoptosis in AML cell lines and primary CD34+ AML cells by inhibiting the AKT/mTOR [335] and NF-κB/BCR-ABL/COX-2 pathways [331,334] or increasing the miR-17/miR-92b/miR-181a pathways [332,333]. It also enhanced the cytotoxic effects of daunorubicin and cytarabine in vitro and in AML xenograft mice [335]. In addition, gallic acid inhibited invasion of K-562 cells related to the downregulation of MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression mediated through the suppression of JNK1/c-Jun/ATF2 and AKT/ERK/c-Jun/c-Fos pathways, respectively [336]. To enhance its therapeutic value, gallic acid has been conjugated with HA, which binds to CD44+ AML cells [443]. Doxorubicin and gallic acid coencapsulated in HA-lipid-polymer nanoparticles induced cytotoxicity in doxorubicin-resistant HL-60 cells in vitro and in vivo [444].

5.1.2. (–)-Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate (EGCG)

EGCG (Figure 3) is an abundant biflavanol mainly found in white tea and green tea made from the leaves of the Camellia sinensis plant. EGCG is the ester of epigallocatechin and gallic acid. It is a topoisomerase inhibitor and a powerful antioxidant. Preclinical studies have reported the antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic effects of EGCG in AML cell lines and primary AML blasts [337,338,339,340,341,342,343,344,345]. EGCG induces apoptosis by inhibiting Bcl-2 expression and PI3K/AKT activity in HL-60 cells [339,345]. It also inhibits NF-κB expression and increases ROS in UF-1 cells and primary AML cells [342,344]. Moreover, it affects the levels of MDR genes (P-gp and ABCC1) expression in HL-60 cells [345]. EGCG supported differentiation of FLT3-mutated myeloid cell lines toward neutrophils through epigenetic modulations of genes involved in the cell cycle and differentiation (p27, C/EBPα, C/EBPβ) and downregulation of epigenetic regulators DNA methyltransferase-1 and HDAC-1/-2 [338,340,341,342]. In AML xenograft mice, EGCG inhibited AML tumor growth by modulating ROS, BCL-2 proteins (Bax, Bad, Bcl-2) and c-Myc [338,342,344]. Furthermore, EGCG sensitized THP-1 leukemic cells to daunorubicin by inducing the activation of tumor-suppressor proteins, such as retinoblastoma protein and merlin [445].

On the other hand, EGCG has been conjugated with HA, which binds to CD44+ AML cells [348]. The HA-EGCG conjugate promoted the terminal differentiation of CD44+ myeloid cell lines (NB4 and HL-60 cells), and prolonged survival in the HL-60 xenograft mouse model [348]. A micellar nanocomplex from HA-EGCG and daunorubicin showed superior cytotoxic efficacy against MDR-HL-60 cells over free daunorubicin [346]. The chemosensitizing effect was associated with nucleus accumulation of daunorubicin, elevation of intracellular ROS and caspase-mediated apoptosis induction [346]. A micellar nanocomplex self-assembled from EGCG and sorafenib eradicated BM-residing AML cells in AML xenograft mice, and prolonged survival rates more effectively than free sorafenib [347].

5.1.3. Gossypol

Gossypol (AT-101) (Figure 3) is a natural polyphenol extracted from cotton plants of the genus Gossypium. To solve the problems attributable to the presence of the two aldehydes in gossypol, novel derivatives of gossypol were synthesized. Thus, apogossypol (Figure 3), a modified derivative of an atropoisomer of gossypol which lacks the reactive aldehydic groups, was prepared and displays a pro-apoptotic activity comparable to gossypol [446] (Figure 3). Solution-based studies showed that gossypol and apogossypol are capable of binding and inhibiting BCL2 proteins (i.e., Mcl-1, Bcl-2, and Bcl-XL) with high affinity [446,447,448].

Both molecules induced caspase-dependent apoptosis in AML cell lines by activating the transcription factors ATF-3/-4 and Noxa, which can then bind to and inhibit Mcl-1 [349,350]. Gossypol was effective towards primary AML cells from patients with adverse prognostic factors (i.e., hyperleukocytosis, FLT3-ITD mutations) and from elderly patients and patients who did not achieve complete remission after induction therapy [350]. Combination of gossypol and idarubicin resulted in synergistic apoptosis of CD34+CD38− leukemia stem-like cells (sorted from Kasumi-1 cell lines) and primary LSCs in vitro [351,352], through the inhibition of IL-6/JAK1/STAT3 signaling [352]. The clinical application of gossypol appears limited by poor aqueous solubility, rapid metabolism and systemic toxicity [449]. Various derivatives of gossypol have been developed, such as gossypol Schiff bases and gossypolone, which are less toxic and retain similar therapeutic benefits [450]. Nanocarrier platforms have been engineered to improve gossypol’s therapeutic index in both in vitro and in vivo cancer models [449].

5.1.4. Resveratrol

Resveratrol (3,4′,5-trihydroxystilbene) (Figure 3) is a polyphenol belonging to the class of stilbenes; it is present in the seeds, stems and skins of grapes, nuts, cocoa and certain berries. Resveratrol comes in two isomeric forms, trans- and cis-, with the trans-isomer being the bioactive form [451]. Resveratrol exhibits antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic activities in AML cell lines [332,353,354,355,356,357,452]. Resveratrol triggers apoptotic effects in FLT3-ITD AML cells via the inhibition of ceramide catabolism enzymes [452], sensitizes U937 cells to HDAC inhibitors through ROS-mediated activation of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway [357] and increases the expression of miR-181a, miR-17, miR-92b and Bax in HL-60 cells [332]. It suppresses colony-forming cell proliferation of AML BM cells from patients with newly diagnosed AML [359], and induces death in blood AML cells (especially leukemic cells with the FAB M3) [358]. Resveratrol exhibits low water solubility and rapid metabolism, leading to low systemic bioavailability. In order to enhance the cytotoxic effects of resveratrol, a series of analogs and formulations have been developed [453,454,455,456,457], including 3,3′,4,4′,5,5′-hexahydroxystilbene (that induces apoptosis in HL-60 cells through NF-κB inhibition) [454], micronized resveratrol (that allows increased drug absorption, thus increasing availability) [455] and resveratrol encapsulated into nano- and micro-particles [456,457].

5.1.5. Curcumin

Curcumin (Figure 3) is a polyphenolic pigment isolated from the rhizomes of the plant Curcuma longa. A number of preclinical studies have showed that curcumin inhibits the growth and induces apoptosis in AML cell lines and primary AML blasts [360,361,362,363,364,365,366,367,368,369,370,371,372,373,458]. Curcumin elicits different signal transduction cascades, including (i) the inhibition of Bcl-2, DNA methyltransferase 1 and survivin [361,363,368,369], (ii) the alteration of the JNK/p38/MAPK/ERK/NF-κB and FLT3/PI3K/AKT pathways [366,370,371,372], and (iii) the downregulation of MMP-2, MMP-9 and VEGF [361,364,366,371]. In line, the growth and invasion of SHI-1 cells in vitro and in vivo appears related to the alteration of MAPK and MMP-2/-9 expression [366]. Curcumin may also promote apoptosis of adriamycin-resistant HL-60 cells by blocking the lncRNA HOTAIR/miR-20a-5p/WT1 axis [373]. In mice implanted with MV4-11 AML cells, administration of curcumin resulted in suppression of the tumor growth [369]. Combined with other drugs (doxorubicin, thalidomide, bortezomib, azacytidine), curcumin induces additive or synergistic cytotoxic effects in AML cell lines [362,364,367] and primary CD34+ AML cells [361,367]. In xenograft mouse models, curcumin combined with bortezomib or afuresertib (an AKT inhibitor) suppresses the engraftment, proliferation and survival of AML cells [362,372]. Curcumin exhibits low water solubility and in vivo low bioavailability. This is why a novel curcumin-liposome modified with HA was developed to specifically deliver curcumin to CD44+ AML cells [459]. When compared with free curcumin and nontargeted liposome, the HA-curcumin-liposomes exhibited good stability, high affinity to CD44, increased cellular uptake, and more potent activity on inhibiting AML cell proliferation [459].

5.1.6. Other Polyphenols

Several papers reported the ability of other NPs, polyphenols and flavonoids (Figure 3) to induce apoptosis in leukemic myeloid cell lines and primary AML cells through regulation of different signal transduction cascades. These NPs include wogonin and baicalein (isolated from the roots of Scutellaria baicalensis), apigenin, quercetin and kaempferol (present in fruits and vegetables), naringenin (present in some citrus fruits), nobiletin (found in citrus peels), morin (found in leaves of Psidium guajava), hispidulin (from various plants including Grindelia argentina), scutellarin (from plants of the Scutellaria family) and silybin (from the milk thistle plant Silybum marianum). These molecules were shown to induce caspase-dependent AML cell death associated with (i) the inhibition of the PI3K/AKT and ERK1/2 signaling pathways, (ii) the inhibition of the STAT3 signaling pathway, (iii) the activation of the p38 and/or JNK pathways and (iv) the change of expression of pro-apoptotic (Bad, Bax) and/or anti-apoptotic (Bcl-2, Mcl-1) BCL2 members [383,391,395,460,461]. The VEGF-R2 signaling pathway was also involved in the action of quercetin on mitochondria and Bcl-2 proteins in HL-60 and MV4-11 cells [391]. Quercetin treatment downregulated HDAC-I in HL-60 and U937 cell lines [392]. Furthermore, quercetin induced apoptosis and autophagy in HL-60 leukemic xenografts [396], as well as in primary AML cells by inhibiting PI3K/AKT signaling pathway activation through regulation of miR-224-3p/PTEN axis [395]. Similarly, baicalein induced AML cell autophagy via miR-424 and the PTEN/PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway [378]. Kaempferol was shown to reduce the expression of MDR genes (P-gp and ABCC1) in HL-60 cells [345,460]. Treatment of THP-1 and KG-1 cells with quercetin or apigenin combined with doxorubicin caused a synergistic downregulation of glutathione levels and increased DNA damage, driving apoptosis [385,386,387].

Several laboratories reported the synthesis of novel flavone derivatives (Figure 3). The 2′,3-dinitroflavone-8-acetic acid was shown to be a noncytotoxic inhibitor of APN activity carried by CD13 in AML cell lines [408] and primary AML blood cells (Nguyen and Bauvois, unpublished results 2008). The 3,3′-diamino-4′-methoxyflavone [462] induced caspase-dependent apoptosis of AML cell lines and suppressed colony-forming cell proliferation of primary AML cells [410]. As a novel proteasome inhibitor, this flavone targeted Bax activation and the degradation of caspase-3 substrate of P70S6K during AML cell death [410]. The 2′-nitroflavone and 3,6-dihydroxyflavone [463,464] induced apoptosis in HL-60 cells through the JNK/ERK1/2/Bax and p38/JNK/ROS signalings [411,413]. ME-344 [4,4′-((3R,4S)-7-Hydroxy-8-methylchroman-3,4-diyl)diphenol] is a second generation of 2H-chromene related to phenoxodiol, a synthetic compound related to the natural isoflavone genistein [465]. ME-344 induced apoptosis in leukemia cell lines and primary AML cells (from BM and blood) by increasing mitochondrial ROS generation [414]. It reduced tumor growth in an AML xenograft model [414]. ME-344 also enhanced venetoclax antileukemic activity against leukemic cell lines and primary AML samples, including those resistant to cytarabine, through suppression of OXPHOS and purine biosynthesis [415]. ME-344 is now used as single agent or in combination therapies to treat patients with solid tumors [465], thus supporting its future clinical evaluation in AML patients.

5.2. Organosulfur Compounds

Allium vegetables (including garlic, onions, leeks, chives and scallions) are used throughout the world for their apparent health benefits, which are largely attributed to the presence of sulfur compounds in these plants. The major sulfur-containing molecules in intact garlic (Allium sativum) are sulfoxides, which are converted into sulfides and thiosulfinates [466,467]. Allicin isolated from garlic is rapidly decomposed to diallyl disulfide, diallyl trisulfide and diallyl tetrasulfide (Figure 4) [466]. These molecules induce apoptosis in AML cell lines [416,417,418,419,420,421,422]. The pro-apoptotic activity of diallyl disulfide may occur through the inhibition of the ERK/p38/MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways, and ROS increase [418,419,420]. Diallyl tetrasulfide treatment led to the induction of apoptosis by promoting activation of Bax and Bak and counteracting Bcl-xL, phospho-Bad and Bcl-2 in U937 cells [422]. Ajoene is another garlic-derived unsaturated disulfide formed by the bonding of three allicin molecules (Figure 4) [423]. Ajoene was shown to inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis of AML cell lines [423,424]. The addition of ajoene enhanced caspase-dependent apoptosis in both cytarabine- and fludarabine-treated KGI cells through activation of 20S proteasome and inhibition of Bcl-2 expression [425]. The thiosulfinates dimethyl thiosulfinate and dipropyl thiosulfinate are mainly identified in onion and leek (Figure 5) [467]. Both compounds (i) inhibited the growth of AML cell lines (U937, HL-60, NB4, MonoMac-6), (ii) induced differentiation of leukemic cells towards macrophages, and (iii) inhibited the expression of TNF-α and MMP-9 at the post-transcriptional level [426].

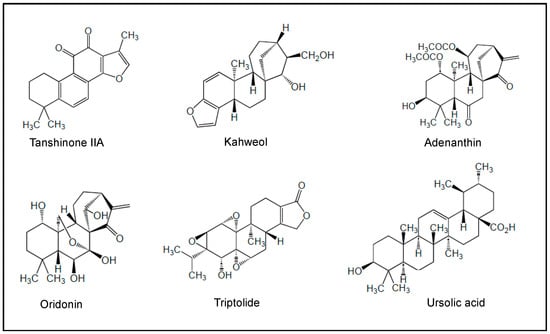

5.3. Terpenes

Numerous biological characteristics of natural terpenes have been documented, including their antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, antihyperglycemic, anti-inflammatory and antiparasitic effects, as well as their cancer chemopreventive benefits [468]. Among them, tanshinone IIA (from Salvia miltiorrhiza), kahweol (from Arabica coffee), adenanthin (from the leaves of Rabdosia adenantha), oridonin (from the herb Isodon rubescens, and marine sponges in the genus Agelas), triptolide (from the Chinese herb Tripterygium wilfordii hook F) and ursolic acid (from many plants such as Mirabilis jalapa and numerous fruits and herbs) (Figure 5) have been reported to induce differentiation and apoptosis in AML cell lines and primary AML cells through the modulation of distinct signalings related to (i) the AKT/JNK/ERK signaling pathways, (ii) the activation of C/EBPβ, (iii) the increase in ROS, and (iv) the inhibition of anti-apoptotic BCL2 proteins (Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Mcl-1, XIAP) and upregulation of pro-apoptotic proteins (Bim, Bax) [427,428,429,431,432,469,470]. The combination of oridonin and venetoclax effectively inhibited the growth of AML xenograft tumors in mice and prolonged the survival time of tumor-bearing mice [470].

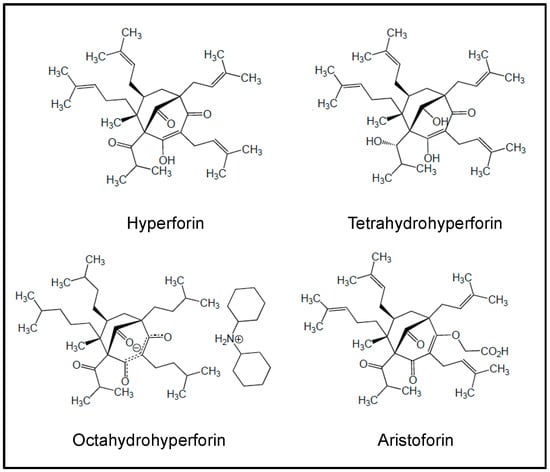

5.4. Hyperforin

The polyprenylated acylphloroglucinol hyperforin (Figure 6) has been isolated from the plant St. John’s wort, Hypericum perforatum. As a multi-targeting agent, hyperforin displays antidepressant, antibacterial, anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory properties [471,472]. It exhibits antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic activities towards AML cell lines and primary AML cells (from blood and BM) independently of the latter’s FAB subtype [81,434,435,471]. Hyperforin was identified as a novel inhibitor of AKT1 activity [435]. Thus, hyperforin’s pro-apoptotic effect in U937 cells involved inhibition of AKT1 signaling, mitochondria and dysfunctions of Bcl-2 members (i.e., Noxa and Bad, which is a direct downstream target of AKT1), thus leading to activation of procaspases -9/-3 [435]. The induction of apoptosis by hyperforin in primary AML blasts significantly paralleled the inhibition of release of MMP-2/-9 and VEGF-A by hyperforin (without altering transcripts) [81]. Hyperforin was also shown to be a potential inhibitor of P-gp functional activity in myeloid cell lines [436]. However, the poor solubility and stability of hyperforin in aqueous solution, as well as its sensitivity to light and oxygen, limits its potential clinical application [473]. Several derivatives with improved stability and ameliorated solubility and pharmacological activities have been next developed, including tetrahydrohyperforin octahydrohyperforin [474] and O-(carboxymethyl)hyperforin, named aristoforin [473] (Figure 6). Encapsulated hyperforin into polymeric nanoparticles shows improved inhibitory bioactivity toward 5-lipoxygenase activity in neutrophils [475]. It remains to be determined whether these analogues retain the anti-leukemic properties of hyperforin in AML models.

6. Future Directions for NPs and NPDs in the Context of AML Therapy

This section highlights (i) the relevance of NP/NPDs in prodrug’s strategies, (ii) the interplay between NP/NPDs and AML metabolism and (iii) the identification of additional AML-associated antigens as potential chemotherapeutic targets of NPs and NPDs.

Research efforts opened up the field of NPs and NPDs to prodrug strategies [476,477]. For example, based on the ADC concept (combination of drugs with mAbs), taking advantage of the plasma esterase activity, a prodrug of acivicin was synthesized with a self-immolative spacer capable of releasing acivicin linked to a mAb which can recognize an AML associated-antigen [329,330]. The concept of this prodrug structure could be used with other NPs/NPDs, or conjugated to different AML-associated antigen Abs (directed against CD33, CD13, CD44, etc.), leading to its potential use in AML treatment. Using the pharmacore fusion strategy, bestatin–HDAC inhibitor hybrids were synthesized to obtain novel prodrugs. Among them, two bestatin–vorinostat prodrugs were successfully developed as APN/HDAC dual inhibitors, which exhibit superior antitumor activity compared to bestatin and vorinostat alone [158,166]. In this context, the APN/HDAC inhibitor developed by Jia et al. induces apoptosis in the AML MV4-11 cell line [166]. A third example of prodrug strategy exploited the enzymatic activity of APN/CD13 overexpressed in cancer cells for the activation of melflufen (melphalan-flufenamide) in active cytotoxic melphalan. Melflufen has successfully reached clinical trial phase III in R/R multiple myeloma [478]. In AML, melfufen treatment shows anti-leukemia activity in vitro and in vivo [146]. These examples provide new avenues for the development of NP prodrugs against AML.

As exemplified by CPX-351, the incorporation of bioactive NPs and NPDs into nanodelivery systems can enhance the drug loading capacity, half-life in biological systems, sustained release and selective biodistribution in cancer cells. The nanoformulations developed include polymeric nanoparticles, micelles, nanogels, dendrimers, liposomes, metallic nanoparticles, metallic liposomes and HA-nanoparticles [477,479]. With the focus on AML, two nanosystems were designed and synthesized by incorporating flavopiridol, EGCG and sorafenib. Flavopiridol incorporated into copper-containing liposome exhibited extended circulation lifetimes and demonstrated significant therapeutic activity in subcutaneous AML models [265]. A micellar nanocomplex self-assembled from EGCG and sorafenib successfully eradicated BM-residing AML cells in AML xenograft mice, and prolonged survival rates more effectively than free sorafenib [347]. Besides AML, other studies have demonstrated promising therapeutic activity of nanosystems engineered with polyphenols (including romidepsin, gallic acid, gossypol, resveratrol, curcumin, quercetin, kaempferol), metformin, hyperforin and garlic against solid tumors [265,277,443,449,456,475,480,481,482,483]. These NP/NPD-nanosystems successfully assessed in solid cancers could be evaluated in AML.

A great interest in the potential use of HA-based nanoparticles against CD44+ tumors arose when the ability of the natural polysaccharide HA to bind to its primary receptor CD44 overexpressed in cancer cells was demonstrated, thus allowing its efficient internalization in tumor cells [484]. Daunorubicin, doxorubicin, quercetin, EGCG, naringenin, curcumin, resveratrol and gallic acid have been incorporated into HA-based systems and tested in cancer cells of different origins [346,444,459,485,486]. To date, four HA-based nanosystems have been developed and successfully tested in AML models, with doxorubicin crosslinked to HA-lipoic acid-nanoparticles [486], doxorubicin and gallic acid coencapsulated in HA-lipid-polymer nanoparticles [444], daunorubicin and HA-EGCG assembled into micelles [346] and curcumin in HA-liposomes [459]. So far, no NP-based nanomedicines are in clinical use for AML treatment, but undoubtedly, they offer valuable insights for the next generation of AML therapy.

One important insight that deserves attention concerns metabolic reprogramming in AML. The main metabolic pathways dysregulated in AML are glycolysis, AA metabolism, mitochondrial metabolism (OXPHOS) and lipid metabolism, all of which support proliferation and survival of AML cells and LSCs [487,488,489]. In peculiar, LSCs and treatment-resistant cells are highly dependent on mitochondrial metabolism, with high levels of OXPHOS and low levels of ROS [487,488]. As detailed in this review, most NPs and NPDs induced apoptosis in AML cell models by altering distinct metabolic profiles, associated with decreased levels of OXPHOS, COX-1/COX-2, cholesterol, fatty acid (FA) oxidation and increased ROS levels. Elevated levels of ROS (i.e., O.2, H2O2, HO. and diverse peroxides) cause damage to lipids, proteins and DNA. Moreover, valproic treatment was shown to alter the levels of the AA and lipid metabolites in serum samples collected from AML patients treated with valproic acid [286]. While clinical trials of metformin or lovastatin, combined with cytarabine for R/R AML, were abandoned due to slow accrual, a phase I study adding pitavastatin to venetoclax-based therapy in new patients with AML showed that pitavastatin was well-tolerated [226]. A phase II trial with pravastatin combined with idarubicin and cytarabine resulted in a high remission rate in relapsed AML patients with favorable risk profiles, associated with inhibition of cholesterol synthesis [224]. In phases II/III, valproic acid appeared to be a safe and effective treatment option for AML patients, particularly when used in conjunction with ATRA and DNA-hypomethylating drugs (Table 1). Clinical trials for AML have evaluated other metabolism-related drugs (which target glycolysis, AA metabolism, OXPHOS and lipid biosynthesis, as well as IDH enzymes involved in the tricarboxylic acid cycle) alone or in combination with other drugs in patients with R/R AML and AML patients with IDH1/2 mutations [489]. Although no metabolic inhibitor has yet been included in standard AML treatment, the value of metabolic-related drugs including NPs/NPDs in the AML metabolic machinery could hold promise in future clinical settings in combination with conventional therapies.