Radiomics for Predicting the Efficacy of Immunotherapy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Radiomics Quality Score Assessment

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Data Extraction

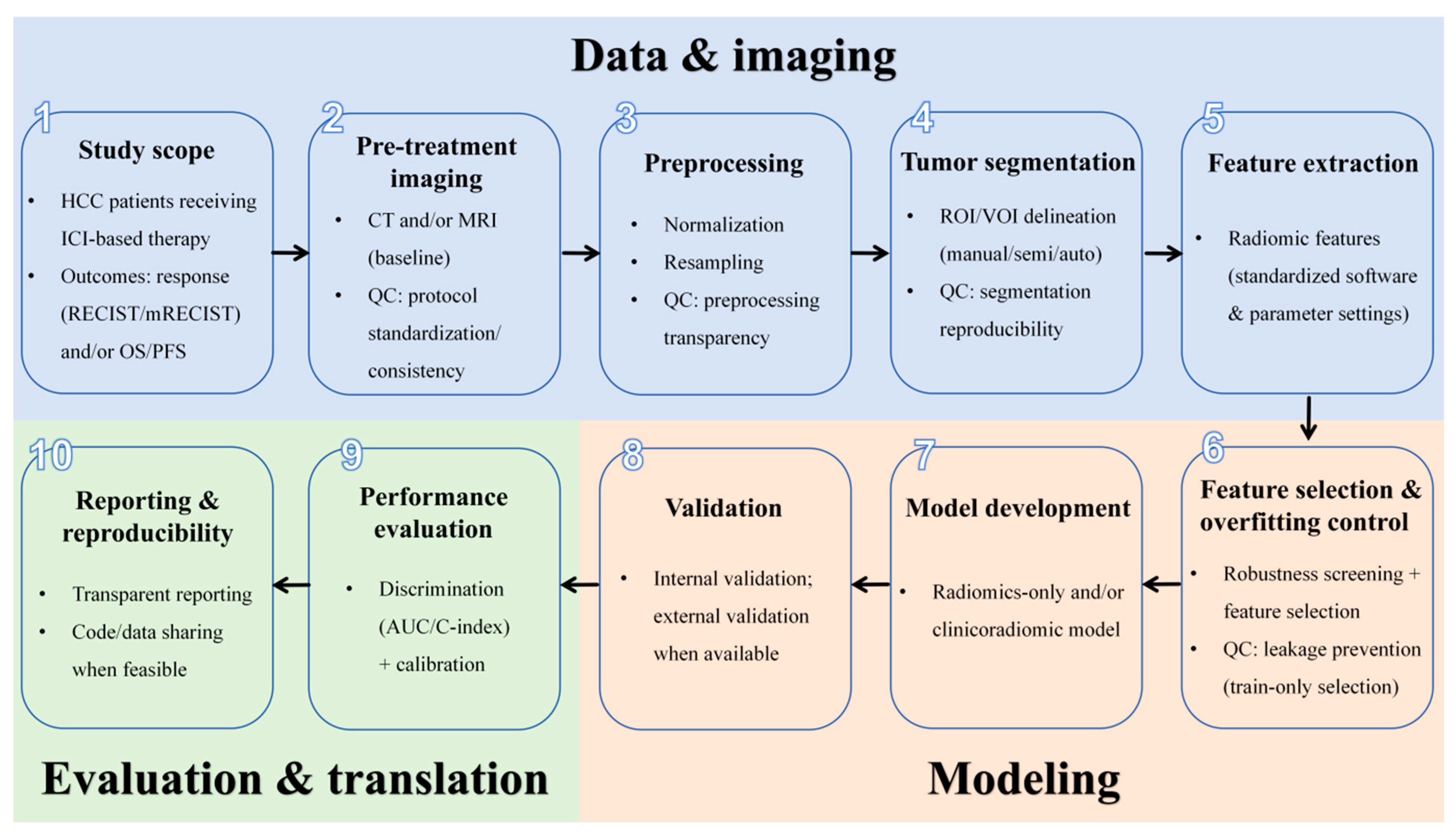

2.4. Quality Assessment

3. Results

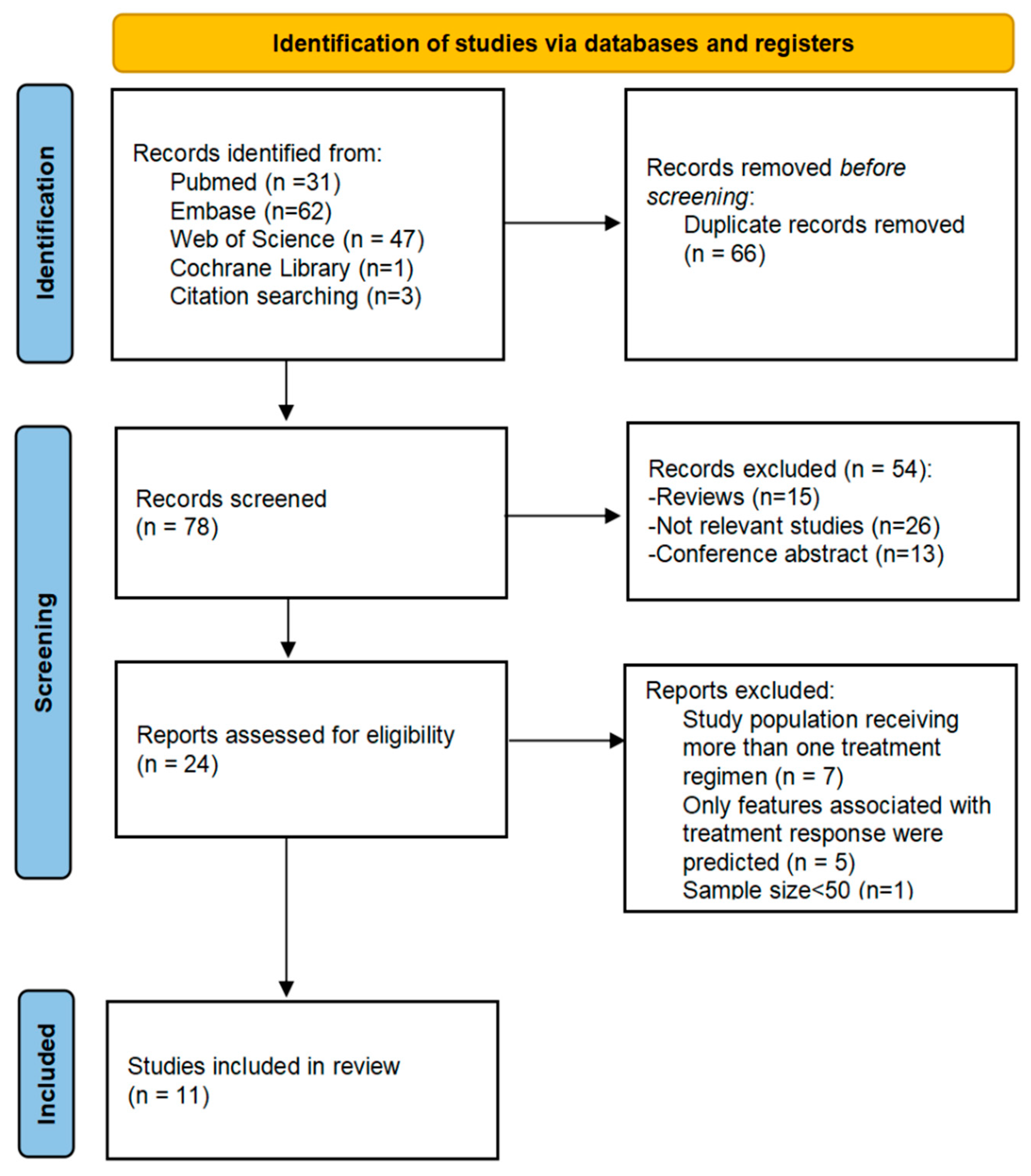

3.1. Literature Search

3.2. Overall Characteristics of Included Studies

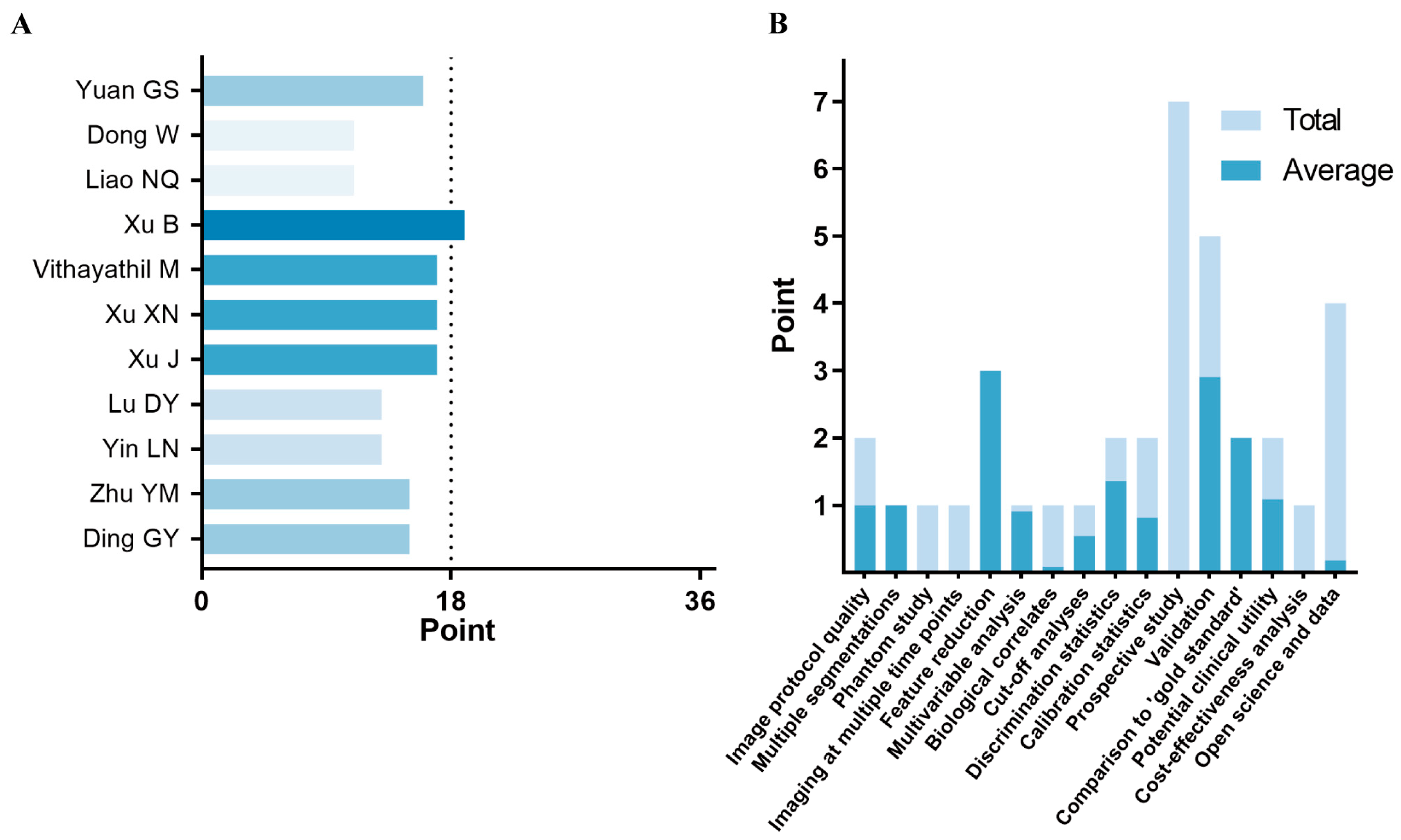

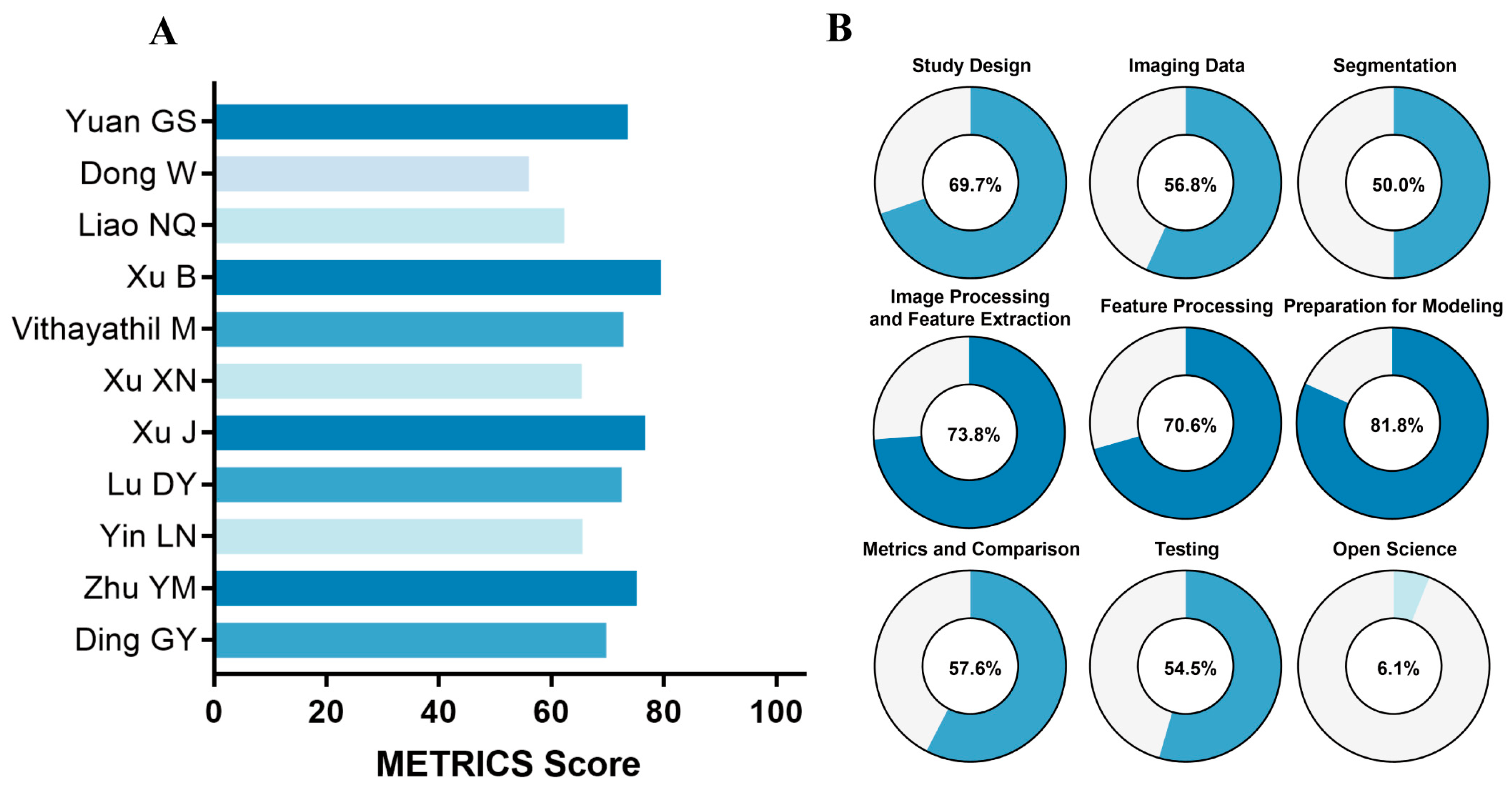

3.3. Methodological Quality Assessment

3.4. Characteristics of the Radiomics Model Pipeline

3.5. Performance of Radiomics Models in Predicting Treatment Response

3.6. Performance of Radiomics Models in Predicting OS

3.7. Performance of Radiomics Models in Predicting PFS

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Heterogeneity and Predictive Performance

4.2. Methodological Quality Assessment (RQS and METRICS)

4.3. Major Limitations of Current Evidence

4.4. Clinical Implications and Future Directions

4.5. Limitations of This Review

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumgay, H.; Ferlay, J.; De, M.C.; Georges, D.; Ibrahim, A.S.; Zheng, R.; Wei, W.; Lemmens, V.; Soerjomataram, I. Global, regional and national burden of primary liver cancer by subtype. Eur. J. Cancer 2022, 161, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimassa, L.; Finn, R.S.; Sangro, B. Combination immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yu, J.; Sun, X.; Li, J.; Cao, S.; Han, Y.; Wang, H.; Yang, Z.; Li, J.; Hu, C.; et al. Sequencing of systemic therapy in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2024, 204, 104522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, T.; Kang, Y.K.; Kim, T.Y.; El, A.B.; Santoro, A.; Sangro, B.; Melero, I.; Kudo, M.; Hou, M.M.; Matilla, A.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab in Patients with Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma Previously Treated with Sorafenib: The CheckMate 040 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, e204564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, Q.; Mei, J.; Yang, Z.; Chen, M.; Liang, T. Real-world efficiency of lenvatinib plus PD-1 blockades in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: An exploration for expanded indications. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llovet, J.M.; De, B.T.; Kulik, L.; Haber, P.K.; Greten, T.F.; Meyer, T.; Lencioni, R. Locoregional therapies in the era of molecular and immune treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 293–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangro, B.; Sarobe, P.; Hervás, S.S.; Melero, I. Advances in immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, A.L.; Qin, S.; Ikeda, M.; Galle, P.R.; Ducreux, M.; Kim, T.Y.; Lim, H.Y.; Kudo, M.; Breder, V.; Merle, P.; et al. Updated efficacy and safety data from IMbrave150: Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab vs. sorafenib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2022, 76, 862–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Yang, X.; Piao, M.; Xun, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ning, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; et al. Biomarkers and prognostic factors of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor-based therapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomark. Res. 2024, 12, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paijens, S.T.; Vledder, A.; De, B.M.; Nijman, H.W. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in the immunotherapy era. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2021, 18, 842–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samstein, R.M.; Lee, C.H.; Shoushtari, A.N.; Hellmann, M.D.; Shen, R.; Janjigian, Y.Y.; Barron, D.A.; Zehir, A.; Jordan, E.J.; Omuro, A.; et al. Tumor mutational load predicts survival after immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, P.; Leijenaar, R.T.H.; Deist, T.M.; Peerlings, J.; De, J.E.; Van, T.J.; Sanduleanu, S.; Larue, R.T.H.M.; Even, A.J.G.; Jochems, A.; et al. Radiomics: The bridge between medical imaging and personalized medicine. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, Z.; Song, J.; He, Q.; Chen, B.; Chen, Z.; Xie, X.; Shu, D.; Chen, K.; Wang, Y.; Chen, G. Application of artificial intelligence radiomics in the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 173, 108337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Mckenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocak, B.; Akinci, D.T.; Mercaldo, N.; Alberich, B.A.; Baessler, B.; Ambrosini, I.; Andreychenko, A.E.; Bakas, S.; Beets, R.G.H.; Bressem, K.; et al. METhodological RadiomICs Score (METRICS): A quality scoring tool for radiomics research endorsed by EuSoMII. Insights Imaging 2024, 15, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, G.; Song, Y.; Li, Q.; Hu, X.; Zang, M.; Dai, W.; Cheng, X.; Huang, W.; Yu, W.; Chen, M.; et al. Development and Validation of a Contrast-Enhanced CT-Based Radiomics Nomogram for Prediction of Therapeutic Efficacy of Anti-PD-1 Antibodies in Advanced HCC Patients. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 613946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Ji, Y.; Pi, S.; Chen, Q.F. Noninvasive imaging-based machine learning algorithm to identify progressive disease in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma receiving second-line systemic therapy. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, B.; Dong, S.Y.; Bai, X.L.; Song, T.Q.; Zhang, B.H.; Zhou, L.D.; Chen, Y.J.; Zeng, Z.M.; Wang, K.; Zhao, H.T.; et al. Tumor Radiomic Features on Pretreatment MRI to Predict Response to Lenvatinib plus an Anti-PD-1 Antibody in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Multicenter Study. Liver Cancer 2023, 12, 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, N.Q.; Deng, Z.J.; Wei, W.; Lu, J.H.; Li, M.J.; Ma, L.; Chen, Q.F.; Zhong, J.H. Deep learning of pretreatment multiphase CT images for predicting response to lenvatinib and immune checkpoint inhibitors in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 24, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.; Li, K. A CT-Based Clinical-Radiomics Nomogram for Predicting the Overall Survival to TACE Combined with Camrelizumab and Apatinib in Patients with Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Acad. Radiol. 2025, 32, 1993–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Zhou, L.; Zuo, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, X.; Weng, J.; Yu, Z.; Ji, J.; Xia, J. MRI Radiomics to Predict Early Treatment Response to TACE Combined with Lenvatinib Plus a PD-1 Inhibitor for Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Portal Vein Tumor Thrombus. J. Hepatocell. Carcinoma 2025, 12, 985–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vithayathil, M.; Koku, D.; Campani, C.; Nault, J.C.; Sutter, O.; Ganne, C.N.; Aboagye, E.O.; Sharma, R. Machine learning based radiomic models outperform clinical biomarkers in predicting outcomes after immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2025, 83, 959–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, T.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Fu, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Cai, W.; Song, R.; et al. A multimodal fusion system predicting survival benefits of immune checkpoint inhibitors in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. npj Precis. Oncol. 2025, 9, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Jiang, X.; Jiang, H.; Yuan, X.; Zhao, M.; Wang, Y.; Chen, G.; Li, G.; Duan, Y. Prediction of prognosis of immune checkpoint inhibitors combined with anti-angiogenic agents for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma by machine learning-based radiomics. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Liu, R.; Li, W.; Li, S.; Hou, X. Deep learning-based CT radiomics predicts prognosis of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma treated with TACE-HAIC combined with PD-1 inhibitors and tyrosine kinase inhibitors. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025, 25, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Liu, T.; Chen, J.; Wen, L.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, D. Prediction of therapeutic response to transarterial chemoembolization plus systemic therapy regimen in hepatocellular carcinoma using pretreatment contrast-enhanced MRI based habitat analysis and Crossformer model. Abdom. Radiol. 2025, 50, 2464–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, L.; Mo, X.; You, J.; Chen, L.; Fang, J.; Wang, F.; Jin, Z.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, S. Current status and quality of radiomic studies for predicting immunotherapy response and outcome in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2021, 49, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; De, F.F.L.; Shi, Z.; Zhu, C.; Dekker, A.; Bermejo, I.; Wee, L. Systematic review of radiomic biomarkers for predicting immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment outcomes. Methods 2021, 188, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evangelista, L.; Fiz, F.; Laudicella, R.; Bianconi, F.; Castello, A.; Guglielmo, P.; Liberini, V.; Manco, L.; Frantellizzi, V.; Giordano, A.; et al. PET Radiomics and Response to Immunotherapy in Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Cancers 2023, 15, 3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, K.Y.; Zhu, Y.; Xie, S.Z.; Qin, L.X. Immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment and immunotherapy of hepatocellular carcinoma: Current status and prospectives. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 17, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bera, K.; Braman, N.; Gupta, A.; Velcheti, V.; Madabhushi, A. Predicting cancer outcomes with radiomics and artificial intelligence in radiology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 19, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, A.; Wu, X.; Hu, X.; Bai, G.; Fan, Y.; Stål, P.; Brismar, T.B. Radiomics models for preoperative prediction of the histopathological grade of hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and radiomics quality score assessment. Eur. J. Radiol. 2023, 166, 111015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbaspour, E.; Karimzadhagh, S.; Monsef, A.; Joukar, F.; Mansour, G.F.; Hassanipour, S. Application of radiomics for preoperative prediction of lymph node metastasis in colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Surg. 2024, 110, 3795–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First Author | Publication Year | Country | Study Design | Study Center | Treatment | No. of Patients | Gender (Male/Female) | Age | Predicted Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yuan, G.S. [17] | 2021 | China | Retrospective | S | ICIs | 58 | 52/6 | 55; 52 # | mRECIST |

| Xu, B. [19] | 2022 | China | Retrospective | M | ICIs + Targeted therapy | 170 | 154/16 | 55; 57 # | RECIST1.1, OS, PFS |

| Dong, W. [18] | 2023 | China | Retrospective | S | ICIs + Targeted therapy | 55 | 50/5 | 53 | RECIST1.1, OS |

| Liao, N.Q. [20] | 2024 | China | Retrospective | S | ICIs + Targeted therapy | 120 | 99/21 | 48; 47 # | RECIST1.1 |

| Vithayathil, M. [23] | 2025 | UK | Retrospective | M | ICIs + Targeted therapy | 152 | 130/22 | 67; 63 # | OS, PFS |

| Xu, X.N. [25] | 2025 | China | Retrospective | S | ICIs + Targeted therapy | 111 | 105/6 | 56 | PFS |

| Xu, J. [24] | 2025 | China | Retrospective | M | ICIs + Targeted therapy | 859 | 736/123 | 58; 57 # | OS, PFS |

| Lu, D.Y. [22] | 2025 | China | Retrospective | M | ICIs + Targeted therapy + Locoregional therapy | 115 | 104/11 | 56 | mRECIST |

| Yin, L.N. [26] | 2025 | China | Retrospective | M | ICIs + Targeted therapy + Locoregional therapy | 122 | 104/18 | 54 | mRECIS, PFS |

| Zhu, Y.M. [27] | 2025 | China | Retrospective | M | ICIs + Targeted therapy + Locoregional therapy | 102 | 92/10 | 53; 57 # | mRECIST |

| Ding, G.Y. [21] | 2025 | China | Retrospective | S | ICIs + Targeted therapy + Locoregional therapy | 150 | 133/17 | >60; 38% | OS |

| Study ID | Imaging Modality | Imaging Sequence | Segmentation Method | Feature Extraction | Feature Extracted | Feature Selection | Feature in the Model | Modeling Algorithms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yuan et al. [17] | CT | NC, AP | Manually | Pyradiomics | 3160 | ICC, Spearman correlation test, t test, and LASSO | 9 | LASSO, RF, SVM, and DT |

| Xu et al. [19] | MRI | AP, DP | Manually | Pyradiomics | 2236 | ICC, t test, and LASSO | 17 | Neural network model |

| Dong et al. [18] | CT | AP, PVP | Semi-auto | Pyradiomics | 2458 | ICC and LASSO | 10 | SVM, NB, Rpart, Ctree, RF, KNN, neuralnet, boosting, bagging, and logistics |

| Liao et al. [20] | CT | AP, PVP, DP | Unclear | ResNet-18 | - | - | - | ResNet-18, VGG19, ResNet-50, and Mobilenetv3 |

| Vithayathil, M. et al. [23] | CT | PVP | semi-auto | TexLAB | 892 | LASSO, elastic net, RFE, PCA, Boruta, mutual information, Pearson and Spearman correlations, Kendall correlation, ANOVA F-test, variance threshold, and forward selection | - | XGBoost, logistic regression, Naïve bayes, neural network, random forest, Ridge regression, SVM, and Kmeans clustering |

| Xu et al. [25] | MRI | AP, PVP, DP | Manually | Pyradiomics | 2736 | Univariable Cox model and LASSO | 32 | RSF and Cox regression |

| Xu et al. [24] | CT | AP, PVP, DP | Semi-auto | Pyradiomics | 642 | Univariate Cox model, VIF, and RSF | 16 | EfficientNet B1 Model, semi-supervised hybrid model, CNN-Transformer Model, and RSF |

| Lu et al. [22] | MRI | T1WI, T2WI, DWI | Manually | 3D slicer | 851 | ICC, t test, LASSO, and RFE | 12 | SVM, KNN, XGBoost, and RF |

| Yin et al. [26] | CT | AP, PVP, DP | Manually | ResNet50 | - | MLP and Cox regression | 6 | Cox regression |

| Zhu et al. [27] | MRI | T1WI, AP, PVP, DP | Manually | Pyradiomics | 428 | ICC and LASSO | 5 | Extra Trees, Crossformer, and ResNet50 |

| Ding et al. [21] | CT | AP, PVP | Manually | Pyradiomics | 3376 | ICC, Pearson correlation, univariate Cox analysis, LASSO Cox regression | 5 | LASSO Cox regression |

| Study ID | Radiomics | Clinical–Radiomics | Calibration Curve | Decision Curve Analysis | Model Form | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC (Training) | AUC (Internal Validation) | AUC (External Validation) | AUC (Training) | AUC (Internal Validation) | AUC (External Validation) | ||||

| ICIs | |||||||||

| Yuan, G.S. et al. [17] | 0.772 | 0.705 | - | 0.894 [0.797, 0.991] | 0.883 [0.716, 0.998] | - | Yes | Yes | Nomogram |

| ICIs combined with molecular targeted therapy | |||||||||

| Xu, B. et al. [19] | 0.886 [0.815, 0.957] | - | 0.820 [0.648, 0.984] | 0.987 [0.968, 1.000] | - | 0.884 [0.762, 1.000] | Yes | Yes | - |

| Dong, W. et al. [18] | 0.933 | 0.792 | - | - | - | - | No | No | - |

| Liao, N.Q. et al. [20] | 0.956 [0.931, 0.981] | 0.802 [0.753, 0.851] | - | - | - | - | No | No | - |

| ICIs combined with molecular targeted therapy and local therapy | |||||||||

| Lu, D.Y. et al. [22] | 0.92 [0.86, 0.97] | 0.79 [0.61, 0.95] | - | 0.95 [0.68, 0.98] | 0.84 [0.91, 0.99] | - | No | No | - |

| Yin, L.N. et al. [26] | - | - | - | 0.96 | 0.87 | 0.85 | No | No | - |

| Zhu, Y.M. et al. [27] | 0.877 [0.795, 0.958] | 0.721 [0.556, 0.886] | - | - | - | - | Yes | Yes | - |

| Study ID | Radiomics | Clinical–Radiomics | Calibration Curve | Decision Curve Analysis | Model Form | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-Index (Training) | C-Index (Internal Validation) | C-Index (External Validation) | C-Index (Training) | C-Index (Internal Validation) | C-Index (External Validation) | ||||

| ICIs combined with molecular targeted therapy | |||||||||

| Dong, W. et al. [18] | - | - | - | 0.81 | - | - | No | Yes | - |

| Vithayathil, M. et al. [23] | 0.77 [0.69, 0.84] | - | 0.63 [0.55, 0.70] | 0.78 [0.67–0.85] | - | 0.67 [0.60, 0.74] | Yes | Yes | - |

| Xu, J. et al. [24] | 0.76 [0.73, 0.79] | 0.70 [0.64, 0.76] | 0.69 [0.64, 0.73] | 0.82 [0.79, 0.84] | 0.73 [0.68, 0.79] | 0.74 [0.70, 0.78] | No | No | Formula |

| ICIs combined with molecular targeted therapy and local therapy | |||||||||

| Ding, G.Y. et al. [21] | 0.838 [0.806, 0.870] | 0.817 [0.748, 0.886] | - | 0.867 [0.839, 0.898] | 0.840 [0.782, 0.897] | - | Yes | Yes | Nomogram |

| Study ID | Radiomics | Clinical–Radiomics | Calibration Curve | Decision Curve Analysis | Model Form | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-Index (Training) | C-Index (Internal Validation) | C-Index (External Validation) | C-Index (Training) | C-Index (Internal Validation) | C-Index (External Validation) | ||||

| ICIs combined with molecular targeted therapy | |||||||||

| Vithayathil, M. et al. [23] | 0.67 [0.58, 0.76] | - | 0.54 [0.48, 0.62] | 0.70 [0.62, 0.78] | - | 0.59 [0.51, 0.67] | Yes | Yes | - |

| Xu, X.N. et al. [25] | 0.837 | 0.830 | - | 0.846 [0.804,0.879] | 0.845 [0.767, 0.893] | - | Yes | Yes | Nomogram |

| Xu, J. et al. [24] | 0.69 [0.66, 0.71] | 0.64 [0.58, 0.69] | 0.66 [0.61, 0.70] | 0.72 [0.69, 0.74] | 0.68 [0.62, 0.74] | 0.69 [0.65, 0.73] | No | No | Formula |

| ICIs combined with molecular targeted therapy and local therapy | |||||||||

| Yin, L.N. et al. [26] | 0.59 | - | - | 0.75 | - | - | Yes | No | Nomogram |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, R.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Y.; Gui, Z.; Zhang, A. Radiomics for Predicting the Efficacy of Immunotherapy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Radiomics Quality Score Assessment. Cancers 2026, 18, 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020186

Zhang R, Zhang C, Liu Y, Gui Z, Zhang A. Radiomics for Predicting the Efficacy of Immunotherapy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Radiomics Quality Score Assessment. Cancers. 2026; 18(2):186. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020186

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Ruixin, Chengjie Zhang, Yi Liu, Zhiguo Gui, and Anhong Zhang. 2026. "Radiomics for Predicting the Efficacy of Immunotherapy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Radiomics Quality Score Assessment" Cancers 18, no. 2: 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020186

APA StyleZhang, R., Zhang, C., Liu, Y., Gui, Z., & Zhang, A. (2026). Radiomics for Predicting the Efficacy of Immunotherapy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Radiomics Quality Score Assessment. Cancers, 18(2), 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020186