Simple Summary

Acute leukemias are difficult-to-treat blood cancers which many patients will eventually die from despite intensive chemotherapies and bone marrow transplantation. Antibodies that recognize proteins on leukemia cells and deliver a cell toxin (so-called antibody–drug conjugates) have been developed to improve these outcomes. Two such drugs, gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO, for acute myeloid leukemia) and inotuzumab ozogamicin (IO, for acute lymphoblastic leukemia), have been approved for use in patients but are not always effective. In our laboratory research, we undertook genome-wide screening to discover genes that are associated with response or resistance to the toxin (calicheamicin) that both GO and IO contain. Our studies revealed the importance of several DNA damage pathway regulation genes for the anti-leukemia activity of calicheamicin, including TP53, ATM, and MDM2. Building on these data, we then identified several small-molecule inhibitors that increased GO/IO efficacy—findings that support further evaluation of these combination therapies with clinical testing.

Abstract

Background/Objectives: Approved for treatment of acute leukemia, gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO) and inotuzumab ozogamicin (InO) are antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) that deliver a toxic calicheamicin (CLM) derivative. The resistance mechanisms to GO/InO remain incompletely understood. Methods: We performed a genome-wide clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)/Cas9 screen for CLM sensitivity genes, and then performed confirmatory cytotoxicity assays. Results: Several DNA damage pathway regulation genes were identified, most notably TP53. Across 13 acute leukemia cell lines, the six TP53-mutant cell lines (TP53MUT) were indeed 10- to 1000-fold less sensitive to CLM than the seven TP53WT cell lines. In five TP53WT/KO syngeneic cell line pairs we generated, TP53KO cells were significantly less sensitive to CLM than their TP53WT counterparts. In TP53WT but not TP53MUT cells, the MDM2 inhibitor and p53 activator, idasanutlin, enhanced CLM cytotoxicity, demonstrating that decoupling of cells from MDM2-p53 regulation sensitizes leukemia cells to CLM. The ATM inhibitors AZD1390 and lartesertib also significantly enhanced CLM efficacy but did so independent of the TP53 status. In contrast, neither an ATR inhibitor, Chk1/Chk2 inhibitor, Chk2 inhibitor, or a PARP inhibitor significantly impacted CLM-induced cytotoxicity across the thirteen cell lines. Together, our studies identify ATM, MDM2, and TP53—which are in the same cellular response to DNA damage pathway—as key modulators of CLM-induced cytotoxicity in acute leukemia cells. Conclusions: These results support further evaluation of combination therapies with corresponding small-molecule inhibitors (currently pursued for therapy of other cancers) toward clinical testing as novel strategies to increase the efficacy of CLM-based ADCs such as GO and InO.

1. Introduction

Acute leukemias remain difficult to treat despite multi-agent chemotherapy, allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation, and the increasing availability of immunotherapeutics and small-molecule inhibitors [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) have long been pursued to improve cure rates in these malignancies, with a major focus on CD33 (for acute myeloid leukemia [AML]) and CD22 (for B-acute lymphoblastic leukemia [B-ALL]). Improved outcomes with the CD33 ADC, gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO) [7,8,9], and the CD22 ADC, inotuzumab ozogamicin (InO) [10,11,12], validate these efforts. Still, in many patients, GO and InO are insufficiently effective. Rational use of combinatorial therapies may be one strategy to widen the therapeutic reach of these ADCs in acute leukemia.

Both GO and InO deliver a derivative of calicheamicin-γ1I (N-acetyl gamma calicheamicin-γ1I dimethyl hydrazide [CLM]) as a toxic payload. Once internalized and released from the antibody, CLM binds DNA in the minor groove and undergoes structural changes, leading to a diradical that abstracts hydrogens from the phosphodiester backbone of DNA, resulting in single- and double-strand breaks [8,13]. G2/M cell cycle arrest follows DNA damage sensing, and cell death—primarily via mitochondrial apoptosis pathways—ensues if damage is overwhelming. Modulation or loss of target antigen (for CD22), DNA damage response dysregulation, drug efflux pumps, and apoptotic dysregulation have been implicated in resistance to CLM-based ADCs [8,13,14,15]. However, the cellular mechanisms allowing acute leukemia cells to resist GO and InO remain incompletely understood. Consequently, to identify genetic vulnerabilities and new biomarkers that could inform selection of patients most likely to benefit from CLM-based ADCs and to develop combination therapies to augment the efficacy of these ADCs, we performed a genome-wide clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)/Cas9 screen to discover genes associated with CLM sensitivity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Therapeutics and Chemicals

CLM was provided by Pfizer (New York, NY, USA). AZD1390, BML-277, ceralasertib, idasanutlin, lartesertib, and prexasertib were obtained from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX, USA). Veliparib was obtained from Apexbio Technology (Houston, TX, USA). For drug selection, blasticidin was purchased from Research Projects International (Mount Prospect, IL, USA), puromycin was obtained from Gold Biotechnology (Saint Louis, MO, USA), and G418 was obtained from ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA).

2.2. Parental Human Acute Leukemia Cell Lines

Human myeloid and lymphoid EOL-1, HL-60, K562, Kasumi, KG-1, MOLM-13, REH, TF-1, and THP-1 cells were grown in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; for EOL-1, K562, REH, and THP-1 cells), 20% FBS (for Kasumi, KG-1, and MOLM-13 cells), or 10% BCS (for HL-60 cells). TF-1 cells were supplemented with 4 ng/mL GM-CSF (Peprotech; Cranbury, NJ, USA). Human myeloid and lymphoid OCI-AML3 and RS4;11 cells were grown in alpha-MEM with 10% FBS. ML-1 and MV4;11 cells were grown in IMDM and 10% FBS, with MV4;11 cells supplemented with 5 ng/mL GM-CSF with 1x Insulin–Transferrin–Selenium supplement (ThermoFisher Scientific). All cell lines were grown with penicillin/streptomycin, tested for mycoplasma contamination (MycoAlert Mycoplasma Detection Kit; Lonza, Basel, Switzerland), and authenticated using standard STR CODIS typing.

2.3. Lentiviral Expression Vectors

Lentiviral vectors containing Cas9 expression cassettes, LentiCas9-Blast (plasmid ID # 52962), Lenti-iCas9-neo (plasmid ID # 85400), lentiCRISPR v2 (plasmid ID # 52961), the lentiGuide-puro (plasmid ID # 52963) for expression of individual gRNAs, and the Brunello CRISPR knockout pooled library lentiviral particle prep with puromycin selection cassette, including 76,441 unique gRNAs covering over 19,000 genes, each gene targeted with 4 unique sgRNAs (ID # 73178-LV), were all purchased from Addgene (Watertown, MA, USA). The CD33 knockout (KO) sgRNA targeting exon 1 of CD33 (sequence 5′-CTGCTGCCCCTGCTGTGGGC-3′) was cloned into lentiGuide-puro with standard cloning techniques and confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Cas9 expression lentiviral vector particles and CD33 sgRNA lentiviral particles were prepared as described [16]. Lentivirally transduced sublines, when viral titering was possible, were generated at multiplicities of infection (MOI) of 0.25–25. EGFP-positive cells were isolated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and re-cultured for further analysis/use.

2.4. CRISPR/Cas9 Whole-Genome-Wide Screening

ML-1, K562 or OCI-AML3 cell lines were transduced with viral particles encoding LentiCas9-Blast [17] and selected with blasticidin to generate cells with constitutive Cas9 expression. To reduce the frequency of cells harboring > 1 sgRNA, cells were transduced with MOI of 0.3. Viral transduction of Brunello whole-genome targeting CRISPR/Cas9 library was performed at ~150–300x coverage. Two days later, transduced cells were selected with puromycin. Subsequently, cells were expanded to allow for treatment with either CLM or vehicle. CLM was administered every 3 days at a concentration aimed at inducing 15–30% cell death. Samples were collected on days 0, 6, and 12. Genomic DNA was purified and embedded sgRNA was amplified and barcoded by PCR, sequenced, and analyzed to determine sgRNAs under- or over-represented in CLM-treated populations compared to controls. Bowtie was used for alignment and guide quantification. Model-based Analysis of Genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout (MAGeCK) was used in conjunction with a modified robust ranking aggregation (RRA) algorithm to identify positive/negative selected genes across the two conditions, and hits with a false discovery rate (FDR) < 5% were considered for further study.

2.5. Quantification of CD33 Expression

CD33 cell surface expression was quantified with a PE-conjugated CD33 antibody (clone p67.6; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and reported as median fluorescence intensity (MFI).

2.6. TP53 Genomic Analysis

We used 500 ng of purified genomic DNA from human acute leukemia cells to assess the TP53 allelic status as described [18].

2.7. Quantification of Drug-Induced Cytotoxicity

Human acute leukemia cells were incubated in 96-well round-bottom plates at 5–10 × 103 cells/well with various concentrations of CLM and/or AZD1390, BML-277, ceralasertib, idasanutlin, lartesertib, prexasertib, or veliparib. After 3 days, cell numbers and drug-induced cytotoxicity, using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to detect non-viable cells, were determined flow cytometrically.

2.8. Generation of Human Leukemia Cell Lines with Deletion of TP53

Leukemia cell sublines with deletion of TP53 were generated as described [18]. Briefly, CRISPR/Cas9 editing was carried out by electroporating purified Cas9 protein (TrueCut Cas9 V2; ThermoFisher Scientific) complexed with a pool of synthetic guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting TP53 (sequences: 5′-CGCUAUCUGAGCAGCGCUCA-3′, 5′-GUGCUGUGACUGCUUGUAGA-3′, 5′-CAACAAGAUGUUUUGCCACC-3′; Synthego, Redwood City, CA, USA), using the ECM 380 Square Wave Electroporation system (Harvard Apparatus; Cambridge, MA, USA). TP53 knockout (TP53KO) cells were selected in culture with either 1 µM (myeloid cell lines) or 2.5 µM (lymphoid cell lines) idasanutlin, which was freshly added every 2–3 days. Cytotoxicity assays were performed 14–21 days after electroporation.

2.9. Statistical Considerations

Statistical analyses were performed with Prism (Graphpad; La Jolla, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. CRISPR/Cas9 Whole-Genome Screening Identifies TP53 as a CLM Sensitivity Gene

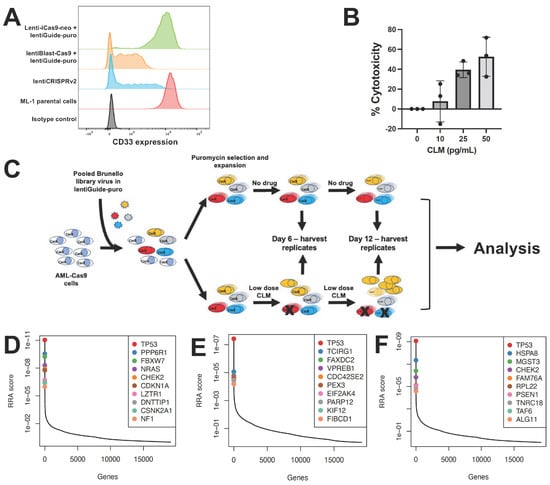

CRISPR whole-genome screening requires library recipient cells expressing Cas9. To identify an optimal screening platform, we compared conditional with constitutive Cas9 expression using a single guide RNA (sgRNA) to disrupt CD33 in ML-1 cells. In our studies, we contrasted an inducible Cas9 expression construct, zeocin-inducible Lenti-iCas9-neo, with constitutive Cas9 expression from the EF1a promoter-driven lentiBlast-Cas9 construct and an all-in-one single expression plasmid construct as control, lentiCRISPRv2, which combines constitutive expression of both Cas9 and sgRNA from one plasmid. While the inducible Cas9 system generated only a small subpopulation of CD33-negative cells, constitutive Cas9 expression yielded a robust CD33KO phenotype (Figure 1A). Based on these results, ML-1 cells with lentiBlast-Cas9 were selected for transduction of the Brunello sgRNA library. Transduced cells were expanded under puromycin selection, and aliquots were simultaneously subjected to CLM titration to identify 25 ng/mL as the CLM dose inducing 15–30% cell death, the desired target cytotoxicity for the drug screen (Figure 1B). The screen was conducted by incubating human acute leukemia cells (ML-1, K562, OCI-AML3) in the presence or absence of CLM. Samples were collected at time 0 as well as after 6 and 12 days of culture. At these time points, cells aliquots were collected, sgRNAs sequenced, and bioinformatically analyzed (Figure 1C). As depicted in Figure 1D, this screen identified several DNA damage pathway regulation genes in ML-1 cells, including TP53 (as the highest ranked hit overall), PPP6R1, FBXW7, CHEK2, CDKN1A, DNTTIP1, and CSNK2A1 as conferring sensitivity to CLM. These findings were confirmed in K562 cells (for TP53; Figure 1E) and OCI-AML3 cells (for TP53 and CHEK2; Figure 1F).

Figure 1.

CRISPR/Cas9 whole-genome drug screening. (A) Optimization of CD33 gene editing. CD33 expression levels were compared in parental ML-1 cells and sublines virally transduced with sgRNA targeting CD33 and Cas9. The lentiCRISPRv2 construct is included as a positive control, and PE-conjugated isotype negative control antibody is shown. (B) CLM dose finding. CLM-induced cytotoxicity was assessed in ML-1 cells after 3 days. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments performed in duplicate wells. (C) Schematic of CRISPR/Cas9 whole-genome sgRNA screen. (D–F) Top 10 CRISPR/Cas9 screening hits as determined by MaGeCK and RRA analysis in (D) ML-1, (E) K562, and (F) OCI-AML3 cells.

3.2. Validation of TP53 as a CLM Sensitivity Gene

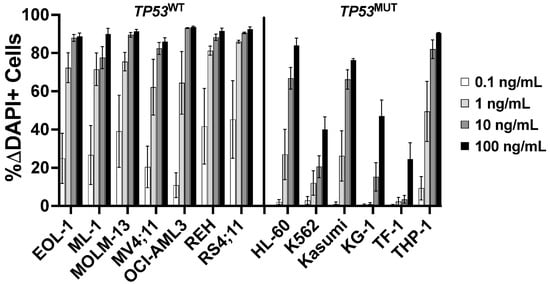

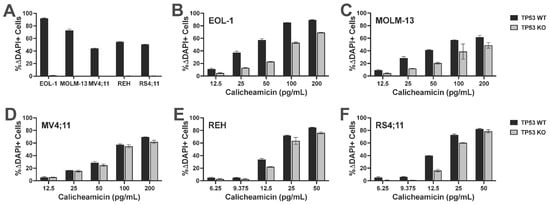

Having identified TP53 as a possible CLM sensitivity gene in our screening, we evaluated the association between TP53 mutations and CLM-induced cytotoxicity in a set of 13 human leukemic cell lines. This set included seven TP53 wild-type (TP53WT: EOL-1, ML-1, MOLM-13, MV4;11, OCI-AML3, REH, and RS4;11) and six TP53 mutant (TP53MUT; HL-60, K562, Kasumi, KG-1, TF-1, and THP-1) cell lines we identified via DNA sequencing for all coding exons of TP53 [18]. Across these 13 acute leukemia cell lines, the 6 TP53MUT cell lines were approximately 10- to 1000-fold less sensitive to CLM than the 7 TP53WT cell lines. For example, at 1 ng/mL, the median (±SEM) CLM-induced cell death was 19 ± 8% in TP53MUT cells and 72 ± 3% in TP53WT cells (Figure 2). To test the relationship between TP53 and CLM sensitivity further, we then derived TP53WT/KO syngeneic cell line pairs via deletion of TP53 from bulk cells via CRISPR/Cas9 and exposure to 1–2.5 µM of the mouse double minute 2 (MDM2) inhibitor, idasanutlin, to enrich for the population of TP53KO cells [18]. As shown in Figure 3, TP53KO sublines indeed showed reduced sensitivity to their TP53WT counterparts in all five cell line models, although the degree of relative resistance varied significantly across cell lines.

Figure 2.

Association between TP53 mutational status and CLM-induced cytotoxicity. Parental cell lines were treated with various doses of CLM. After 3 days, drug-induced cytotoxicity was assessed flow cytometrically. Data are presented as mean ± SEM from 4 independent experiments performed in duplicate wells.

Figure 3.

TP53 deletion leads to relative CLM resistance in syngeneic acute leukemia cell line models. TP53WT cell lines were electroporated with TP53-targeting Cas9/CRISPR sgRNA nucleoprotein complexes and bulk cells were then treated with 1.0 or 2.5 µM idasanutlin for 14 days to enrich for TP53KO cells. (A) Parental cells electroporated with Cas9 alone and idasanutlin-enriched TP53KO cells were treated with 1.0 or 2.5 µM idasanutlin, and idasanutlin-induced cytotoxicity was assessed flow cytometrically after 3 days. TP53WT and idasanutlin-enriched TP53KO (B) EOL-1, (C) MOLM-13, (D) MV4;11, (E) REH, and (F) RS4;11 cell pairs were then subjected to various concentrations of CLM for 3 days before cell numbers and viability were assessed. Data are shown as percent change in DAPI-positive cells and are presented as mean ± SD. Shown is one representative of three qualitatively similar, independent experiments performed in duplicate wells. A second series of experiments with an independent electroporation yielded qualitatively similar results.

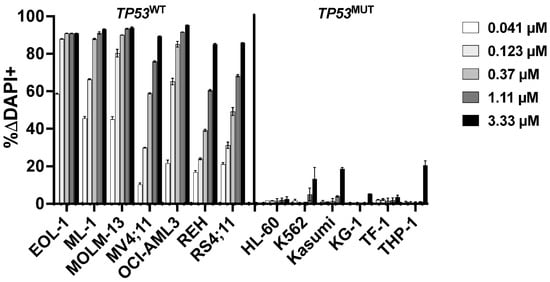

3.3. Validation of Role of DNA Damage Pathways in CLM Sensitivity

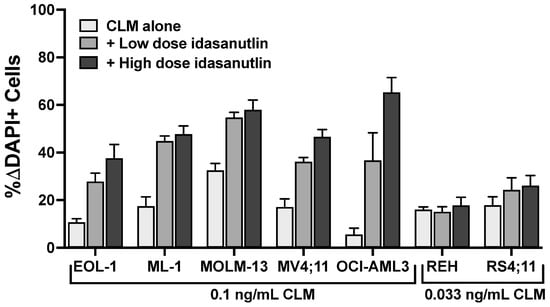

Because TP53 and CHEK2 are in the same cellular DNA damage response pathway as MDM2 and ataxia–telangiectasia mutated (ATM) [19,20,21], we next tested which inhibitors of this pathway regulated response to CLM. We first tested the mouse double minute 2 (MDM2) inhibitor idasanutlin, a strong activator of p53. Nanomolar concentrations of idasanutlin effectively killed parental TP53WT leukemia cell lines. By comparison, much higher doses (3–10 µM) were required to kill parental leukemia cell lines harboring TP53 alterations, in line with the notion that TP53 inactivation render cells insensitive to MDM2 inhibition [22] (Figure 4). We therefore assessed whether idasanutlin enhanced CLM-induced cytotoxicity in TP53WT cells. Indeed, across the seven TP53WT cell lines, drug-induced toxicity increased from a median of 7 ± 5% ΔDAPI+ cells (CLM alone at 0.05 ng/mL) to 31 ± 3% ΔDAPI+ cells when idasanutlin (10–20 nM) was added (Figure 5). In contrast, TP53MUT cells were resistant (<5% ΔDAPI+ cells) to idasanutlin even at 1 µM, and no combinatory effect was seen with CLM (Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 4.

Association between TP53 mutational status and idasanutlin-induced cytotoxicity. Idasanutlin-induced cytotoxicity was assessed flow cytometrically after 3 days. Data are presented as mean ± SD from one representative experiment performed in duplicate wells.

Figure 5.

Idasanutlin enhances CLM-induced cytotoxicity in TP53WT leukemia cell lines. Parental TP53WT leukemia cell lines were treated with a sub-maximally effective dose of CLM in the absence or presence of either a low or high dose of idasanutlin (5 or 10 nM for EOL-1 and MOLM-13 cells; 10 or 20 nM for ML-1, MV4;11, OCI-AML3, REH, and RS4;11 cells). After 3 days, cell numbers and the percentage of dead cells were quantified by flow cytometry. Data are shown as percent change in DAPI-positive cells relative to idasanutlin/medium alone and are presented as mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments performed in duplicate wells.

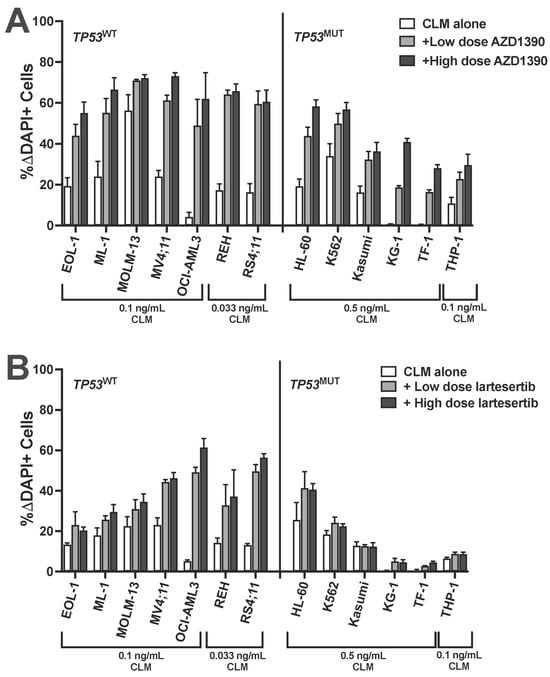

We then tested small-molecule inhibitors that could activate DNA damage pathways upstream of TP53. One such pharmacological target is ATM. Treatment of cells with the ATM inhibitor AZD1390 has been shown to cause cell death in TP53MUT cells [23]. At relatively non-toxic doses (Supplementary Figure S2), AZD1390 enhanced CLM-induced cytotoxicity in all 13 tested human leukemia cell lines, including all 6 TP53MUT cell lines (Figure 6A). Specifically, in TP53WT cell lines, median drug-induced cell death increased from 7 ± 6% with 0.05 ng/mL CLM alone to 41 ± 9% with the addition of 0.25–2.5 µM of AZD1390; across TP53MUT cell lines, the median drug-induced cell death increased from 19 ± 13% with 0.5 ng/mL of CLM to 50 ± 10% with the addition of 1–2.5 µM of AZD1390. Testing of a second ATM inhibitor, lartesertib, yielded qualitatively similar results, except for one cell line (Kasumi) which failed to show any evidence of sensitivity to lartesertib (Figure 6B and Supplementary Figure S3). In contrast, no significant or consistent effects on CLM-induced cytotoxicity were found in combination treatments with an ATR inhibitor (ceralasertib; Supplementary Figure S4), a Chk1/Chk2 inhibitor (prexasertib; Supplementary Figure S5), a Chk2 inhibitor (BML-277; Supplementary Figure S6), or a PARP inhibitor, veliparib. With the latter, for example, in TP53WT cell lines, median drug-induced cell death changed from 3 ± 3% with 0.05 ng/mL CLM alone to 7 ± 6% with the addition of 1–10 µM of veliparib across TP53WT cell lines. Across the leukemia cell lines with TP53 alteration, the median drug-induced cell death changed from 5 ± 5% with 0.5 ng/mL of CLM to 7 ± 7% with the addition of 2.5–10 µM of veliparib (Supplementary Figure S7).

Figure 6.

ATM inhibitors enhance CLM-induced cytotoxicity in acute leukemia cell lines independent of TP53 status. A panel of human acute leukemia cell lines was treated with a sub-maximally effective dose of CLM in the absence or presence of either a low or high dose of (A) AZD1390 (0.1 and 0.25 µM: REH; 0.25 and 1 µM: EOL-1, MV4;11, OCI-AML3, RS4;11, Kasumi, and KG-1; 0.25 and 2.5 µM: MOLM-13, THP-1, and HL-60; 1 and 2.5 µM: TF-1; 2.5 and 5 µM: ML-1 and K562) or (B) lartesertib (1 and 2.5 µM: EOL-1, MOLM-13, MV4;11, REH, RS4;11, HL-60, Kasumi, and KG-1; 2.5 and 5 µM: ML-1, OCI-AML3, K562, TF-1, and THP-1). After 3 days, and cell numbers and the percentage of dead cells were quantified by flow cytometry. Data are shown as percent change in DAPI-positive cells relative to AZD1390 or lartesertib/medium alone and are presented as mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments performed in duplicate wells.

4. Discussion

With GO and InO, CLM-based ADCs are routinely employed in patients with acute leukemia nowadays. However, while they are effective in subsets of patients with CD33+ AML or CD22+ B-ALL, respectively [7,8,9,10,11,12], others do not meaningfully benefit from these drugs as they are currently used. To identify genetic vulnerabilities and new biomarkers that could inform the selection of patients most likely to benefit from CLM-based ADCs and to develop rational combination therapies that augment the efficacy of these ADCs, we performed genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 screening to discover genes associated with CLM sensitivity. In this screen, human acute leukemia cell lines with genetic lesions introduced by CRISPR/Cas9 were exposed to CLM and surviving cells were analyzed for over- or under-representation of genetic lesions relative to the starting cell population as a read-out for resistance or sensitivity to CLM, respectively.

As a main finding, our screen identified TP53 as a key sensitivity gene for CLM, with genetic TP53 deletion being the top hit and leading to relative CLM resistance in all three acute leukemia cell backgrounds tested, including K562 cells which harbor a gain-of-function TP53 point mutation (Q136P) [24] that was possibly selected against in our screening. Consistent with these results, we found human leukemia cell lines with TP53 alterations to be 10- to 1000-fold less sensitive to CLM than TP53WT cell lines across the panel of 13 cell lines we studied. To study the impact of TP53 on CLM sensitivity more directly, we also derived TP53KO sublines from five TP53WT cell lines. In these studies, TP53KO cells were not completely resistant to CLM but were significantly less sensitive to CLM than their TP53WT counterparts, further demonstrating the impact TP53 has on CLM-induced cytotoxicity. Together, these data point to the acute leukemia cells’ TP53 status—a key marker for the sensitivity of both AML and B-ALL to conventional chemotherapy [25,26,27,28]—as a biomarker for patient selection or, in clinical drug testing, patient stratification when CLM-based ADCs are used. Whether TP53-mutated leukemia cells’ sensitivity to CLM-based ADCs is affected by co-mutations that may be present is an open question in need of further study.

Having identified TP53 as a key sensitivity gene for CLM, we then focused our efforts on genes in DNA damage pathways that are affected by TP53, in particular MDM2 and ATM [19,20,21]. In TP53WT but not TP53MUT cells, the MDM2 inhibitor and p53 activator, idasanutlin, enhanced CLM cytotoxicity, demonstrating that decoupling of cells from MDM2-p53 regulation sensitizes leukemia cells to CLM. Moreover, both ATM inhibitors we tested, AZD1390 and lartesertib, significantly enhanced CLM efficacy. Consistent with our data, previous investigations with SV40-transformed fibroblasts derived from ataxia telangiectasia (AT) patients showed hypersensitivity to a calicheamicin derivative [29]. Of potential clinical interest, the effect of ATM inhibitors was independent of the TP53 status, unlike the effect of the MDM2 inhibitor. In contrast to reports by others [30,31], a PARP inhibitor (veliparib) only minimally affected CLM-induced cytotoxicity in our panel of human acute leukemia cell lines. Likewise, CLM-induced cytotoxicity was not significantly modulated by an ATR inhibitor, a Chk1/Chk2 inhibitor, or a Chk2 inhibitor. The latter was unexpected considering that the Chk2-p53 pathway is well established and both TP53 and CHEK2 were identified in our screen and may suggest a role of residual non-catalytic functions of Chk2 in the leukemia cells’ response to CLM-induced cytotoxicity.

Our observation that inhibition of ATM or MDM2 sensitizes acute leukemia cells to CLM may provide the rationale for the clinical exploration of a combination therapy with either GO or InO. While efficacy has been limited thus far, several MDM2 inhibitors have been tested in patients with acute leukemia [32,33,34,35]. Testing of ATM inhibitors in acute leukemia is so far largely confined to preclinical investigations but early-phase clinical trials in other cancers have been completed [36] or initiated (e.g., NCT03423628, NCT05116254, NCT05182905, NCT05396833, NCT06433219, NCT06894979). Our data would support the testing of an MDM2 inhibitor with either GO or InO in patients with TP53WT acute leukemia, whereas the combination of GO or InO with an ATM inhibitor could be explored in patients independent of the TP53 mutational status. It is interesting to speculate—and a goal of future studies—whether p53 reactivators like eprenetapopt (APR-246) [37] might be of value to sensitize acute leukemias with TP53 mutations to CLM-based ADCs.

In our studies, we exclusively focused on CLM-containing ADCs. While our findings do not immediately apply to ADCs delivering other small-molecule toxins, as resistance mechanisms may differ, our experimental approach may offer a blueprint for the identification of genetic vulnerabilities that are critical for the anti-tumor activity of other ADCs.

5. Conclusions

Our study identified ATM, MDM2, and TP53—which exhibit the same cellular response to DNA damage pathways—as key modulators of CLM-induced cytotoxicity in acute leukemia cells. While these findings may not be surprising per se, considering the mechanism of action of CLM [8,13], the observation that our genomic screening identified these modulators as key hits may suggest their potential value as targets for combination therapies. Thus, our results support further evaluation of combination therapies with corresponding small-molecule inhibitors targeting MDM2 or ATM toward clinical testing as novel strategies to increase the efficacy of CLM-based ADCs such as GO and InO.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cancers18010067/s1, Figure S1: Effect of idasanutlin on CLM-induced cytotoxicity in TP53MUT leukemia cell lines. Figure S2: AZD1390-induced cytotoxicity in acute leukemia cell lines. Figure S3: Lartesertib-induced cytotoxicity in acute leukemia cell lines. Figure S4: Effect of ceralasertib on CLM-induced cytotoxicity in human acute leukemia cell lines. Figure S5: Effect of prexasertib on CLM-induced cytotoxicity in human acute leukemia cell lines. Figure S6: Effect of BML-277 on CLM-induced cytotoxicity in human acute leukemia cell lines. Figure S7: Effect of veliparib on CLM-induced cytotoxicity in human acute leukemia cell lines.

Author Contributions

C.M.P.-W. and G.S.L. performed research, analyzed and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. M.G., F.M.C., C.D.G., S.E., P.C., A.R.K., J.L., J.W.B., M.M.Y. and E.R.-A. performed research and analyzed and interpreted the data. R.B.W. conceptualized and designed this study, participated in data analysis and interpretation, and drafted the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript critically and gave final approval to submit it for publication. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by an investigator-sponsored grant agreement with Pfizer (to R.B.W.). R.B.W. also acknowledges receiving support from the José Carreras/E. Donnall Thomas Endowed Chair for Cancer Research. This work was supported by the Cell Manipulation Tools Core-Vector Production of Fred Hutch, which is funded by the NIH/NIDDK Cooperative Center of Excellence in Hematology (U54-DK106829). M.G. is supported by a fellowship training grant from the NIH/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI; T32-HL007093).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All laboratory research was conducted under a broad research protocol approved by the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board (#9045; with annual renewal approved since 23 November 2013).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

For original data and reagents, please contact the corresponding author (rwalter@fredhutch.org).

Acknowledgments

We thank Patrick J. Paddison and Daniel Kuppers (both Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center) for their valuable assistance with the CRISPR/Cas9 screening reagents.

Conflicts of Interest

R.B.W. has received laboratory research grants and/or clinical trial support from ImmunoGen/AbbVie, Jazz, Kura, and Pfizer, and has been a consultant to AbbVie, Eigen, Omeros, and Prelude. The other authors have no competing financial interests to declare.

References

- Döhner, H.; Wei, A.H.; Löwenberg, B. Towards precision medicine for AML. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döhner, H.; Wei, A.H.; Appelbaum, F.R.; Craddock, C.; DiNardo, C.D.; Dombret, H.; Ebert, B.L.; Fenaux, P.; Godley, L.A.; Hasserjian, R.P.; et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2022 recommendations from an international expert panel on behalf of the ELN. Blood 2022, 140, 1345–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabbour, E.; Short, N.J.; Jain, N.; Haddad, F.G.; Welch, M.A.; Ravandi, F.; Kantarjian, H. The evolution of acute lymphoblastic leukemia research and therapy at MD Anderson over four decades. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 16, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldoss, I.; Roboz, G.J.; Bassan, R.; Boissel, N.; DeAngelo, D.J.; Fleming, S.; Gökbuget, N.; Logan, A.C.; Luger, S.M.; Menne, T.; et al. Frontline treatment of adults with newly diagnosed B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet Haematol. 2024, 11, e959–e970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantarjian, H.M.; DiNardo, C.D.; Kadia, T.M.; Daver, N.G.; Altman, J.K.; Stein, E.M.; Jabbour, E.; Schiffer, C.A.; Lang, A.; Ravandi, F. Acute myeloid leukemia management and research in 2025. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 46–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantarjian, H.; Aldoss, I.; Jabbour, E. Management of adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A review. JAMA Oncol. 2025, 11, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, R.K.; Castaigne, S.; Appelbaum, F.R.; Delaunay, J.; Petersdorf, S.; Othus, M.; Estey, E.H.; Dombret, H.; Chevret, S.; Ifrah, N.; et al. Addition of gemtuzumab ozogamicin to induction chemotherapy in adult patients with acute myeloid leukaemia: A meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised controlled trials. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 986–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godwin, C.D.; Gale, R.P.; Walter, R.B. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2017, 31, 1855–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collados-Ros, A.; Muro, M.; Legaz, I. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin in acute myeloid leukemia: Efficacy, toxicity, and resistance mechanisms-a systematic review. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynne, J.; Wright, D.; Stock, W. Inotuzumab: From preclinical development to success in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Adv. 2019, 3, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantarjian, H.M.; Boissel, N.; Papayannidis, C.; Luskin, M.R.; Stelljes, M.; Advani, A.S.; Jabbour, E.J.; Ribera, J.M.; Marks, D.I. Inotuzumab ozogamicin in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Development, current status, and future directions. Cancer 2024, 130, 3631–3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, F.G.; Kantarjian, H.; Short, N.J.; Jain, N.; Senapati, J.; Ravandi, F.; Jabbour, E. Incorporation of immunotherapy into adult B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia therapy. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2025, 23, e257050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, J.D.; O’Brien, M.M. Inotuzumab ozogamicin in B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Efficacy, toxicity, and practical considerations. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1237738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, D.M.; Bossenmaier, B.; Kollmorgen, G.; Niederfellner, G. Acquired resistance to antibody-drug conjugates. Cancers 2019, 11, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Short, N.J.; Kantarjian, H.M.; Chang, T.C.; Ghate, P.S.; Qu, C.; Macaron, W.; Jain, N.; Thakral, B.; Phillips, A.H.; et al. Genomic determinants of response and resistance to inotuzumab ozogamicin in B-cell ALL. Blood 2024, 144, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, R.B.; Raden, B.W.; Kamikura, D.M.; Cooper, J.A.; Bernstein, I.D. Influence of CD33 expression levels and ITIM-dependent internalization on gemtuzumab ozogamicin-induced cytotoxicity. Blood 2005, 105, 1295–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanjana, N.E.; Shalem, O.; Zhang, F. Improved vectors and genome-wide libraries for CRISPR screening. Nat. Methods 2014, 11, 783–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, F.M.; Laszlo, G.S.; Lunn-Halbert, M.C.; Kehret, A.R.; Zweidler-McKay, P.A.; Rodríguez-Arbolí, E.; Wu, D.; Nyberg, K.; Li, J.; Lim, S.Y.T.; et al. Preclinical characterization of the anti-leukemia activity of the CD123 antibody-drug conjugate, pivekimab sunirine (IMGN632). Leukemia 2025, 39, 1243–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abuetabh, Y.; Wu, H.H.; Chai, C.; Al Yousef, H.; Persad, S.; Sergi, C.M.; Leng, R. DNA damage response revisited: The p53 family and its regulators provide endless cancer therapy opportunities. Exp. Mol. Med. 2022, 54, 1658–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, J.; Long, Y.; Maimaitijiang, A.; Su, Z.; Li, W.; Li, J. Unraveling the guardian: P53’s multifaceted role in the DNA damage response and tumor treatment strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, S.E.; Rahimian, E.; Rahimi, S.; Zarandi, B.; Bahraini, M.; Soleymani, M.; Safdari, S.M.; Shabannezhad, A.; Jaafari, N.; Safa, M. From regulation to deregulation of p53 in hematologic malignancies: Implications for diagnosis, prognosis and therapy. Biomark. Res. 2024, 12, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoma, A.; Barbieri, E.; Agarwal, S.; Jackson, J.; Chen, Z.; Kim, Y.; McVay, M.; Shohet, J.M.; Kim, E.S. The MDM2 small-molecule inhibitor RG7388 leads to potent tumor inhibition in p53 wild-type neuroblastoma. Cell Death Discov. 2015, 1, 15026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laverty, D.J.; Gupta, S.K.; Bradshaw, G.A.; Hunter, A.S.; Carlson, B.L.; Calmo, N.M.; Chen, J.; Tian, S.; Sarkaria, J.N.; Nagel, Z.D. ATM inhibition exploits checkpoint defects and ATM-dependent double strand break repair in TP53-mutant glioblastoma. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.A.; Raih, M.F.; Sage, E.E.; Ali, Q.M.; Suliman, O.H.; Ibrahim, S.A.E.; Mohamed, O.; Abdelrazeg, S.; Mohamed, S.B. The impact of mutations on TP53 protein and MicroRNA expression in HNSCC: Novel insights for diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0307859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hof, J.; Krentz, S.; van Schewick, C.; Körner, G.; Shalapour, S.; Rhein, P.; Karawajew, L.; Ludwig, W.D.; Seeger, K.; Henze, G.; et al. Mutations and deletions of the TP53 gene predict nonresponse to treatment and poor outcome in first relapse of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 3185–3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stengel, A.; Kern, W.; Haferlach, T.; Meggendorfer, M.; Fasan, A.; Haferlach, C. The impact of TP53 mutations and TP53 deletions on survival varies between AML, ALL, MDS and CLL: An analysis of 3307 cases. Leukemia 2017, 31, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.; Amin, M.K.; Daver, N.G.; Shah, M.V.; Hiwase, D.; Arber, D.A.; Kharfan-Dabaja, M.A.; Badar, T. What have we learned about TP53-mutated acute myeloid leukemia? Blood Cancer J. 2024, 14, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, M.V.; Arber, D.A.; Hiwase, D.K. TP53-mutated myeloid neoplasms: 2024 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am. J. Hematol. 2025, 100, 88–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, N.; Lyne, L. Sensitivity of fibroblasts derived from ataxia-telangiectasia patients to calicheamicin gamma 1I. Mutat. Res. 1990, 245, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ida, N.; Okura, M.; Tanaka, S.; Hosono, N.; Yamauchi, T. Combining inotuzumab ozogamicin with PARP inhibitors olaparib and talazoparib exerts synergistic cytotoxicity in acute lymphoblastic leukemia by inhibiting DNA strand break repair. Oncol. Rep. 2024, 52, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghelli Luserna di Rorà, A.; Jandoubi, M.; Padella, A.; Ferrari, A.; Marranci, A.; Mazzotti, C.; Olimpico, F.; Ghetti, M.; Ledda, L.; Bochicchio, M.T.; et al. Exploring the role of PARP1 inhibition in enhancing antibody-drug conjugate therapy for acute leukemias: Insights from DNA damage response pathway interactions. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, E.M.; DeAngelo, D.J.; Chromik, J.; Chatterjee, M.; Bauer, S.; Lin, C.C.; Suarez, C.; de Vos, F.; Steeghs, N.; Cassier, P.A.; et al. Results from a first-in-human phase I study of siremadlin (HDM201) in patients with advanced wild-type TP53 solid tumors and acute leukemia. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 870–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konopleva, M.Y.; Röllig, C.; Cavenagh, J.; Deeren, D.; Girshova, L.; Krauter, J.; Martinelli, G.; Montesinos, P.; Schafer, J.A.; Ottmann, O.; et al. Idasanutlin plus cytarabine in relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia: Results of the MIRROS trial. Blood Adv. 2022, 6, 4147–4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daver, N.G.; Dail, M.; Garcia, J.S.; Jonas, B.A.; Yee, K.W.L.; Kelly, K.R.; Vey, N.; Assouline, S.; Roboz, G.J.; Paolini, S.; et al. Venetoclax and idasanutlin in relapsed/refractory AML: A nonrandomized, open-label phase 1b trial. Blood 2023, 141, 1265–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiNardo, C.D.; Olin, R.; Wang, E.S.; Skikne, B.; Rosenthal, J.; Kumar, P.; Sumi, H.; Hizukuri, Y.; Hong, Y.; Patel, P.; et al. Phase 1 dose escalation study of the MDM2 inhibitor milademetan as monotherapy and in combination with azacitidine in patients with myeloid malignancies. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e70028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siu, L.L.; Yap, T.A.; Genta, S.; Pennock, G.; Hicking, C.; Vagge, D.S.; Mukker, J.K.; Locatelli, G.; Tolcher, A.W. A first-in-human study of ATM inhibitor lartesertib as monotherapy in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 31, 4429–4437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, S.; Iwakuma, T. Drugs targeting p53 mutations with FDA approval and in clinical trials. Cancers 2023, 15, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.