CHEMOBRAIN: Cognitive Deficits and Quality of Life in Chemotherapy Patients—Preliminary Assessment and Proposal for an Early Intervention Model

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

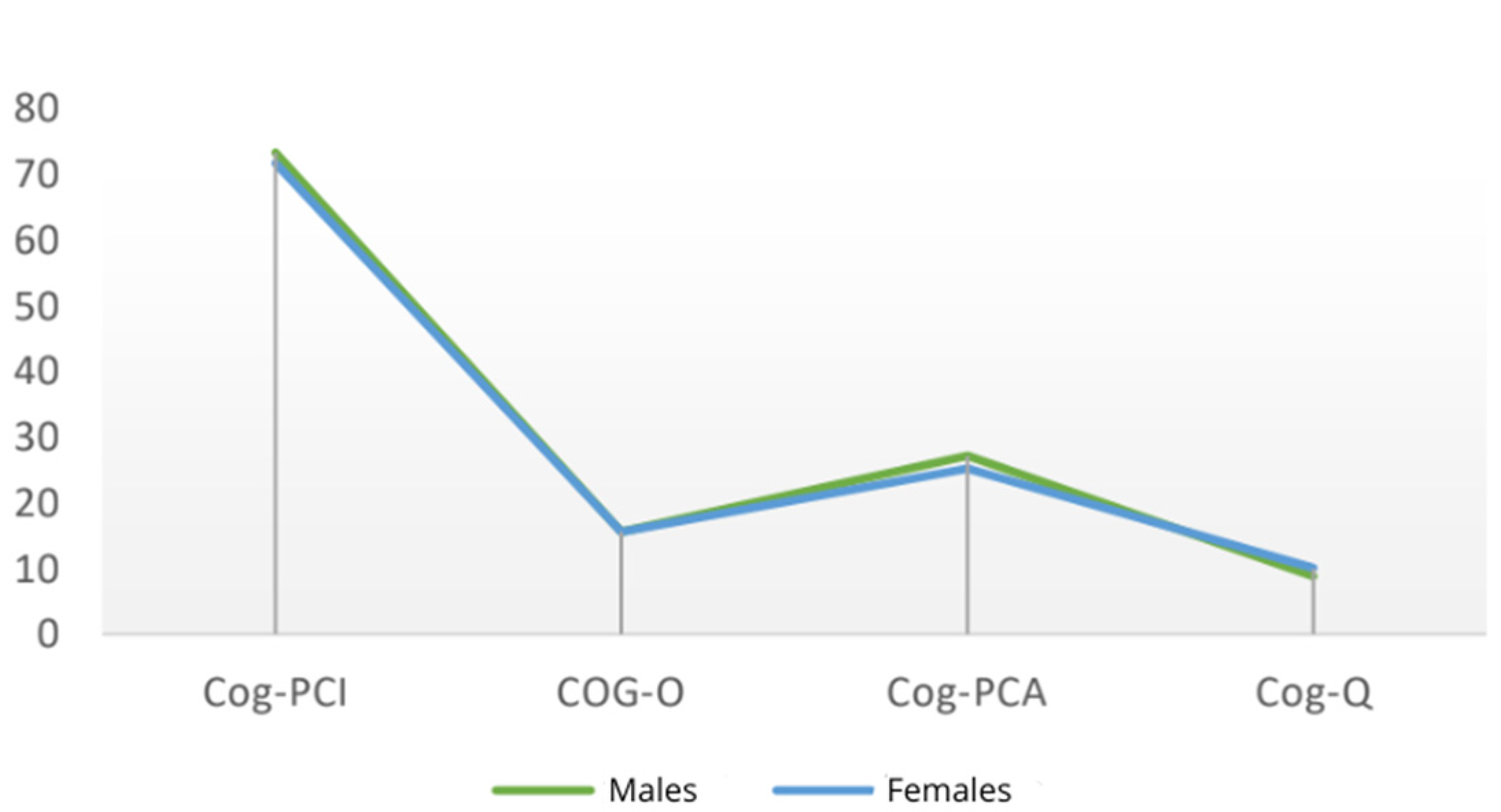

- COG-PCI (Perceived Cognitive Impairment), evaluating cognitive symptoms experienced by the participant;

- COG-O (Others), focusing on comments from others on the participant’s cognitive status;

- COG-PCA (Perceived Cognitive Abilities), measuring cognitive abilities perceived by the participant;

- COG-Q (Quality of Life), exploring the impact of cognitive difficulties on overall quality of life through four items.

3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

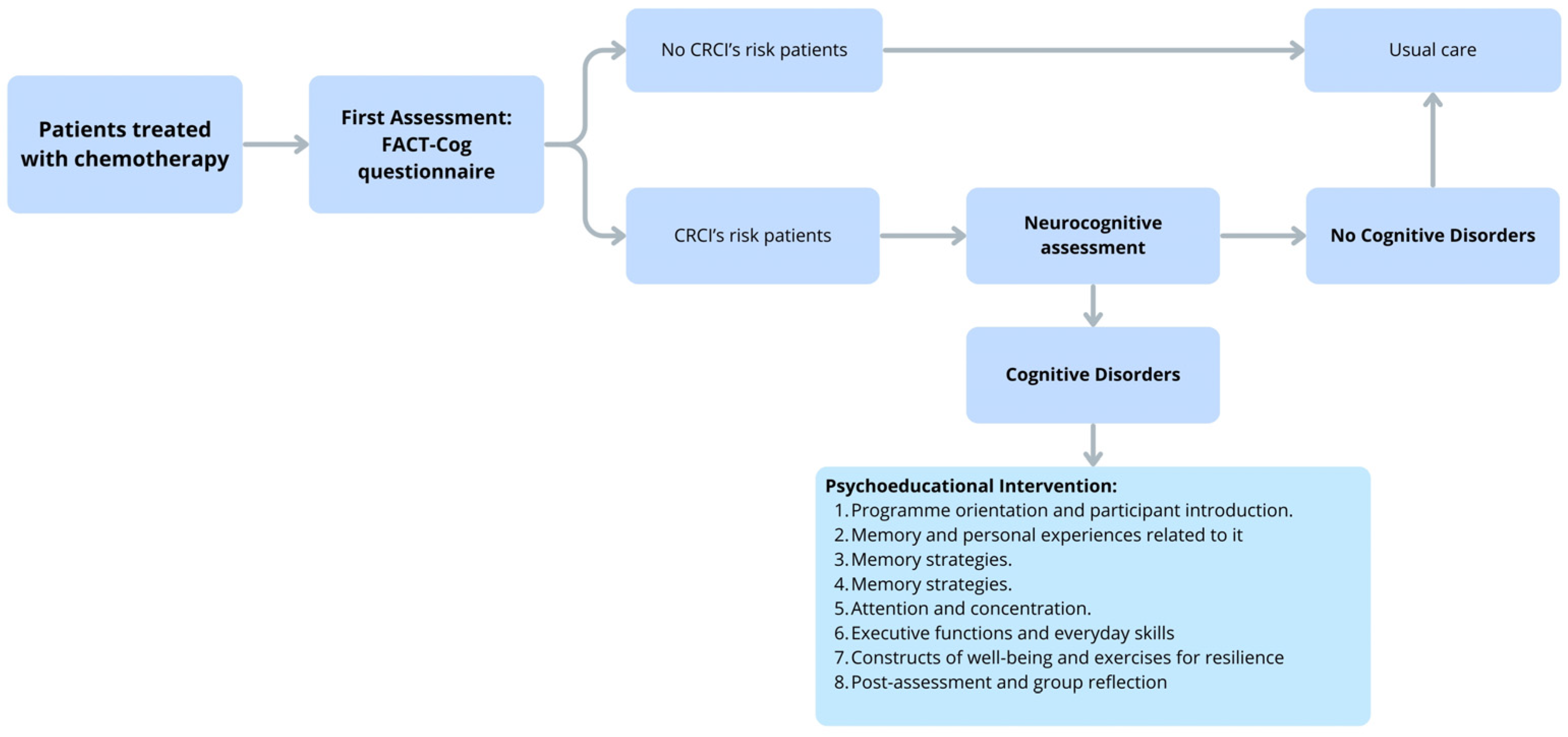

6. Future Perspective: Early Cognitive Intervention Model

7. Limitations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CRCI | Cancer-Related Cognitive Impairments |

| FACT-Cog v.3 | Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—Cognitive Function v.3 |

| ICCTF | International Cognition and Cancer Task Force |

References

- Hutchinson, A.D.; Hosking, J.R.; Kichenadasse, G.; Mattiske, J.K.; Wilson, C. Objective and subjective cognitive impairment following chemotherapy for cancer: A systematic review. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2012, 38, 926–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.Y.; Kim, K.; Ha, B.; Lee, D.; Kim, S.; Ryu, S.; Yang, J.; Jung, S.J. Neurocognitive effects of chemotherapy for colorectal cancer: A systematic review and a meta-analysis of 11 studies. Cancer Res. Treat. 2021, 53, 1134–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.N.; Leak Bryant, A.; Conklin, J.L.; Girdwood, T.; Piepmeier, A.; Hirschey, R. Systematic review of cognitive impairment in colorectal cancer survivors who received chemotherapy. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2021, 48, 634–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; Mao, S.; Dong, H.; Hu, P.; Dong, R. Pathogenesis, assessments, and management of chemotherapy-related cognitive impairment (CRCI): An updated literature review. J. Oncol. 2020, 2020, 3942439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amani, O.; Mazaheri, M.A.; Moghani, M.M.; Zarani, F.; Choolabi, R.H. Chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairment in breast cancer survivors: A systematic review of studies from 2000 to 2021. Cancer Rep. 2024, 7, e1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, A.L.; George, R.P.; O’Malley, L. Prevalence of cognitive impairment following chemotherapy treatment for breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.-H.; So, T.W.; Fan, C.L.; Chung, Y.T.; Lin, C.-C. Prevalence and assessment tools of cancer-related cognitive impairment in lung cancer survivors: A systematic review and proportional meta-analysis. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhong, T.; Zhou, M.; Gao, L.; Chen, L. Prevalence and associated factors of chemotherapy-related cognitive impairment in older breast cancer survivors. J. Adv. Nurs. 2024, 80, 484–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sales, M.V.C.; Suemoto, C.K.; Apolinario, D.; Serrão, V.; Andrade, C.S.; Conceição, D.M.; Amaro, E.; de Melo, B.A.R.; Riechelmann, R.P. Effects of adjuvant chemotherapy on cognitive function of patients with early-stage colorectal cancer. Clin. Color. Cancer 2019, 18, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joly, F.; Rigal, O.; Noal, S.; Giffard, B. Cognitive dysfunction and cancer: Which consequences in terms of disease management? Psycho-Oncology 2011, 20, 1251–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsos, A.; Loomes, M.; Zhou, I.; Macmillan, E.; Sabel, I.; Rotziokos, E.; Beckwith, W.; Johnston, I. Chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairments: White matter pathologies. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2017, 61, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, H.; Li, J.; Hu, S.; He, X.; Partridge, S.C.; Ren, J.; Bian, Y.; Yu, Y.; Qiu, B. Long-term cognitive impairment of breast cancer patients after chemotherapy: A functional MRI study. Eur. J. Radiol. 2016, 85, 1053–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wefel, J.S.; Kesler, S.R.; Noll, K.R.; Schagen, S.B. Clinical characteristics, pathophysiology, and management of noncentral nervous system cancer-related cognitive impairment in adults. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2015, 65, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, J.-E.; Chen, S.; Zhao, F.; Chen, L.; Li, R. Effectiveness of nonpharmacologic interventions for chemotherapy-related cognitive impairment in breast cancer patients: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Cancer Nurs. 2023, 46, E305–E319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullens, M.J.J.; De Vries, J.; Van Warmerdam, L.J.C.; Van De Wal, M.A.; Roukema, J.A. Chemotherapy and cognitive complaints in women with breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2013, 22, 1783–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerulla, N.; Arcusa, À.; Navarro, J.-B.; de la Osa, N.; Garolera, M.; Enero, C.; Chico, G.; Fernández-Morales, L. Cognitive impairment following chemotherapy for breast cancer: The impact of practice effect on results. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2019, 41, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitali, M.; Ripamonti, C.I.; Roila, F.; Proto, C.; Signorelli, D.; Imbimbo, M.; Corrao, G.; Brissa, A.; Rosaria, G.; de Braud, F.; et al. Cognitive impairment and chemotherapy: A brief overview. Crit. Rev. Oncol./Hematol. 2017, 118, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Ah, D.; Tallman, E.F. Perceived cognitive function in breast cancer survivors: Relationships with objective cognitive performance. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2015, 49, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, M.; Joly, F.; Vardy, J.; Ahles, T.; Dubois, M.; Tron, L.; Winocur, G.; De Ruiter, M.B.; Castel, H. Cancer-related cognitive impairment: State of the art, detection, and management strategies in cancer survivors. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1925–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, T.; Turton, P. ‘Chemobrain’: Concentration and memory effects in people receiving chemotherapy—A descriptive phenomenological study. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2011, 20, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vannorsdall, T.D. Cognitive changes related to cancer therapy. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 101, 1115–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visovatti, M.A.; Reuter-Lorenz, P.A.; Chang, A.E.; Northouse, L.; Cimprich, B. Assessment of cognitive impairment and complaints in individuals with colorectal cancer. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2016, 43, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, L.I.; Sweet, J.; Butt, Z.; Lai, J.S.; Cella, D. Measuring patient self-reported cognitive function: Development of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Cognitive Function instrument. J. Support. Oncol. 2009, 7, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, D.S.J.; Loh, V.; Birney, D.P.; Dhillon, H.M.; Fardell, J.E.; Gessler, D.; Vardy, J.L. The structure of the FACT-Cog v3 in cancer patients, students, and older adults. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2018, 55, 1173–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biglia, N.; Bounous, V.E.; Malabaila, A.; Palmisano, D.; Torta, D.M.E.; D’Alonzo, M.; Sismondi, P.; Torta, R. Objective and self-reported cognitive dysfunction in breast cancer women treated with chemotherapy: A prospective study: Chemotherapy-induced cognitive dysfunction. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2012, 21, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, H.M.; Tannock, I.F.; Pond, G.R.; Renton, C.; Rourke, S.B.; Vardy, J.L. Perceived cognitive impairment in people with colorectal cancer who do and do not receive chemotherapy. J. Cancer Surviv. 2018, 12, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janelsins, M.C.; Heckler, C.E.; Peppone, L.J.; Kamen, C.; Mustian, K.M.; Mohile, S.G.; Magnuson, A.; Kleckner, I.R.; Guido, J.J.; Young, K.L.; et al. Cognitive complaints in survivors of breast cancer after chemotherapy compared with age-matched controls. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lycke, M.; Lefebvre, T.; Pottel, L.; Pottel, H.; Ketelaars, L.; Stellamans, K.; Van Eygen, K.; Vergauwe, P.; Werbrouck, P.; Cool, L.; et al. Subjective, but not objective, cognitive complaints impact long-term quality of life in cancer patients. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2019, 37, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janelsins, M.C.; Mohamed, M.; Peppone, L.J.; Magnuson, A.; Belcher, E.K.; Melnik, M.; Dakhil, S.; Geer, J.; Kamen, C.; Minasian, L.; et al. Longitudinal changes in cognitive function in a nationwide cohort study of patients with lymphoma treated with chemotherapy. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2022, 114, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oertelt-Prigione, S.; de Rooij, B.H.; Mols, F.; Oerlemans, S.; Husson, O.; Schoormans, D.; Haanen, J.B.; van de Poll-Franse, L.V. Sex-differences in symptoms and functioning in >5000 cancer survivors: Results from the PROFILES registry. Eur. J. Cancer 2021, 156, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemp, J.R.; Myers, J.S.; Fabian, C.J.; Kimler, B.F.; Khan, Q.J.; Sereika, S.M.; Stanton, A.L. Cognitive functioning and quality of life following chemotherapy in pre- and peri-menopausal women with breast cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2018, 26, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vardy, J.L.; Stouten-Kemperman, M.M.; Pond, G.; Booth, C.M.; Rourke, S.B.; Dhillon, H.M.; Dodd, A.; Crawley, A.; Tannock, I.F. A mechanistic cohort study evaluating cognitive impairment in women treated for breast cancer. Brain Imaging Behav. 2019, 13, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Category | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 40 | |

| Sex | Male | 11 (28) |

| Female | 29 (72) | |

| Age | Mean | 50.65 |

| Range | 65–84 | |

| Range 25–34 | 1 (2) | |

| Range 35–44 | 9 (22) | |

| Range 45–54 | 16 (39) | |

| Range 55–64 | 14 (37) | |

| Diagnosis | Breast cancer | 21 (52) |

| Lung Cancer | 8 (20) | |

| Ovarian or uterine cancer | 2 (5) | |

| Testicular cancer | 2 (5) | |

| Gastrointestinal tract tumor | 2 (5) | |

| Other types of cancer | 5 (13) |

| Variable | Coefficient | Standard Error | p > |t| |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 1.6459 | 1.8636 | 0.383 |

| Cog-PCI | −0.0574 | 0.1502 | 0.704 |

| Cog-O | 0.3141 | 0.9557 | 0.744 |

| Cog-PCA | 0.2441 | 0.1601 | 0.136 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Standard Error | p > |t| |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 1.6459 | 1.8636 | 0.084 |

| Cog-PCI | −0.0574 | 0.1502 | 0.22 |

| Cog-O | 0.3141 | 0.9557 | −0.72 |

| Cog-PCA | 0.2441 | 0.1601 | 0.018 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Standard Error | p > |t| |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 1.6459 | 1.8636 | 0.084 |

| Cog-PCI | −0.0574 | 0.1502 | 0.22 |

| Cog-O | 0.3141 | 0.9557 | −0.72 |

| Cog-PCA | 0.2441 | 0.1601 | 0.018 |

| Time Point | Cog-PCI | Cog-O | Cog-PCA | Cog-Q | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | T0 | 72.10 (±9.03) | 15.08 (±1.01) | 25.70 (±7.70) | 9.73 (±5.23) | 123.09 (±17.93) |

| T1 | 68.33 (±9.18) | 15.03 (±2.01) | 23.60 (±9.03) | 9.78 (±4.00) | 116.73 (±16.05) | |

| T2 | 64.43 (±11.57) | 14.98 (±1.51) | 20.90 (±7.53) | 8.75 (±4.11) | 106.28 (±26.18) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cavalletto, E.; Iannizzi, P.; Bergo, E.; Grosso, D.; Gasparotto, G.; Feltrin, A.; Galtarossa, N.; Bernardi, M. CHEMOBRAIN: Cognitive Deficits and Quality of Life in Chemotherapy Patients—Preliminary Assessment and Proposal for an Early Intervention Model. Cancers 2026, 18, 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010066

Cavalletto E, Iannizzi P, Bergo E, Grosso D, Gasparotto G, Feltrin A, Galtarossa N, Bernardi M. CHEMOBRAIN: Cognitive Deficits and Quality of Life in Chemotherapy Patients—Preliminary Assessment and Proposal for an Early Intervention Model. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):66. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010066

Chicago/Turabian StyleCavalletto, Erika, Pamela Iannizzi, Eleonora Bergo, Daniela Grosso, Giorgia Gasparotto, Alessandra Feltrin, Nicola Galtarossa, and Matteo Bernardi. 2026. "CHEMOBRAIN: Cognitive Deficits and Quality of Life in Chemotherapy Patients—Preliminary Assessment and Proposal for an Early Intervention Model" Cancers 18, no. 1: 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010066

APA StyleCavalletto, E., Iannizzi, P., Bergo, E., Grosso, D., Gasparotto, G., Feltrin, A., Galtarossa, N., & Bernardi, M. (2026). CHEMOBRAIN: Cognitive Deficits and Quality of Life in Chemotherapy Patients—Preliminary Assessment and Proposal for an Early Intervention Model. Cancers, 18(1), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010066