Simple Summary

Comprehensive cancer centers are an important component of cancer control efforts, that have evolved over time. Significant variation exists internationally in the setting, context, and healthcare models in which they operate. Greater clarity is needed regarding the defining characteristics and core functions of comprehensive cancer centers that distinguish them from other types of cancer centers, to inform accreditation programs. The potential impact of comprehensive cancer centers at the patient, provider, organization, system, and societal levels must also be understood to justify the development and continued support, and inform measurements of success. The findings of this chronological scoping review are valuable as they inform refinement and development of comprehensive cancer centers and cancer control efforts, highlighting key priority areas for that require future focus.

Abstract

Background/Objectives: Comprehensive cancer centers (CCCs) remain at the forefront of cancer control efforts. Limited clarity and variation exist around the models, scope, characteristics, and impacts of CCCs around the globe. This scoping review systematically searched and synthesized the international literature, describing core attributes and anticipated and realized impacts of CCCs, detailing changes over time. Methods: Searches for English language sources were conducted across PubMed, Cochrane CENTRAL, Epistemonikos, and the gray literature from January 2002 to April 2024. Data were extracted and appraised by two authors. Results were narratively synthesized. Results: Of 3895 database records and 843 gray literature sources screened, 81 sources were included. Papers were predominantly opinion-based, from the USA and Europe, and published between 2011 and 2020. Internationally, the interconnected attributes of CCCs included (1) clinical service provision; (2) research, data, and innovation; (3) education and clinical support; (4) networks and leadership; (5) health equity and inclusiveness; and (6) accountability and governance. Largely anticipated impacts were synergistic and included delivery of optimal, person-centered, complex care; development of a highly qualified cancer workforce; greater research activity and funding; effective, strategic alliances; and reduction in cancer-related inequalities. Limited evidence was found demonstrating measurable broad outcomes of CCCs. The early literature highlighted the establishment, development, and accreditation of CCCs. The ongoing literature has reflected the evolution of cancer care, key areas for growth, and limitations of CCCs. Recently, the CCC literature has increased exponentially and focused on the need for CCCs to drive networks and leadership to address health equity and inclusiveness. Conclusions: Results suggest that CCCs are yet to reach their full potential, with future efforts ideally focusing on accountability, effective networking, and health equity at a local, national, and international level. CCCs must generate evidence of impact, and continue to evolve in line with contemporary healthcare, to fulfil their role in cancer control efforts.

1. Introduction

Comprehensive cancer centers (CCCs) were first recognized in 1973 by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) in the USA, with the intended purpose of bringing research findings to the greatest number of people as quickly as possible [1]. Development and support for CCCs was established under the National Cancer Act of 1971, which represented the USA’s commitment to the “war on cancer”—focused largely on supporting cancer research and training and supporting cancer researchers in NCI-designated CCCs [1]. In 2002, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended that adequately resourced countries enforce the development and networking of comprehensive cancer treatment centers as a priority action in national cancer control programs [2]. The WHO outlined that these centers should be active in clinical training and research, and serve as national and international reference centers [2]. In 2008, the Organization for European Cancer Institutes (OECI) launched a program to recognize CCCs, based on an adaptation of the NCI accreditation methodology, while the German Cancer Society in partnership with the German Cancer Aid also started their own certification program for CCCs in Germany in 2007 [3,4,5]. Over time, a number of CCCs have been established globally, predominantly in high-income countries [6]. While the original intention of creating CCCs is still relevant, new CCCs may have aims and functions that have evolved over time.

Comprehensive Cancer Centers are defined broadly as centers of excellence in cancer care, research, and education, based on a multiprofessional, interdisciplinary, and multispecialty paradigm [6]. They are recognized as the highest tier of cancer centers and are reported to provide comprehensive care across the cancer continuum (including prevention), drive research and innovation, and be leaders in national cancer control efforts [7]. CCCs can consist of a center or a network of national or regional infrastructures providing services [8]. Variation exists internationally in the availability, purpose, role, characteristics, challenges, and opportunities of CCCs, which have evolved in line with changing burden of disease, demographics, growing social expectations, increasing inequalities, and scarcity of resources [9]. In Europe, the current recommendations are for one CCC per 5–10 million people [10]. The USA and Germany have approximately one CCC per 5–6 million people [7,11]. Other countries are in the early stages of developing CCCs, and some countries have yet to establish a single CCC [3]. However, the mere presence of a CCC does not guarantee equitable high-quality cancer care for all [12,13].

Although CCCs are reported to be an important component of cancer control efforts, significant variation exists internationally in the cancer center models in which they operate [9]. Greater clarity is needed regarding the defining characteristics and core functions of CCCs that distinguish them from other types of cancer centers. The potential impact of CCCs at the patient, provider, organization, system, and societal levels must also be understood to justify the development and continued support of CCCs and inform measurements of success. Many lessons can be learned from countries with well-established models of CCCs, around successes, limitations, and future directions [9]. To the best of our knowledge, no review has collated, described, and synthesized the broad international published and unpublished literature on the attributes and impacts of CCCs. The aim of this high-level review was to describe the defining characteristics of CCCs, their anticipated and realized impact, and changes to the CCC literature over time. Specifically, the review questions were as follows: (1) what are the key attributes of CCCs; (2) what are the anticipated and realized impacts of CCCs; and (3) how has the CCC literature evolved over time?

2. Materials and Methods

A chronological scoping review was conducted with a systematic search, exploring the attributes and impacts of CCCs as they have evolved over time. The JBI (Joanna Briggs Institute) methodology [14] and PRISMA guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews PRISMA-ScR checklist [15]) (Supplementary File S1) were followed. The protocol for this scoping review and a complimentary concurrent systematic review was registered in one protocol prospectively with the Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews database (PROSPERO ID# CRD42023387620).

2.1. Search Strategy

Searches were conducted across the following databases: PubMed, Cochrane Library, CINAHL (EBSCOhost), and Epistemonikos. Gray literature searches (for information sources that are not commercially published) were also conducted through PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, Google, Google Scholar, and World Health Organization Institutional and Repository for Information Sharing. Reference lists of included sources were searched to identify further potentially relevant articles. Library catalogues were not searched; however, book chapters were found in database, gray literature, and hand searching. Cross-checking was performed between the current scoping review and a concurrent systematic review (conducted by the authorship team) exploring differences in outcomes between CCCs and non-CCCs [16]. Search terms used were centered on “comprehensive cancer center”. Searches were conducted in January 2023, and repeated in October 2023 and May 2024. The full search strategy can be found in Supplementary File S2.

2.2. Eligibility

Eligibility criteria (Table 1) included any source in English that provided information on the key attributes or impacts (anticipated or realized) of CCCs in any country. Sources published from January 2002 to May 2024 were included to coincide with the year the WHO National Cancer Control Programs Policies and Managerial Guidelines were published, calling for the reinforcement of the development of CCCs internationally [2]. In countries with accreditation and designation programs, sources focused on centers formally designated as CCCs were included. In countries without formal accreditation programs, sources reporting on self-declared CCCs were included.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria.

2.3. Article Selection

Records retrieved from the database searches were imported into Covidence software, with duplicates removed. Two reviewers independently screened the title, abstract, and full text (CT and EB) against eligibility criteria. The gray literature was searched by two researchers independently (EB and JJ), and sources were assessed against the selection criteria by one author and reviewed by a second author. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached. All decisions were recorded in study-specific tables.

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

Characteristics of the individual sources (study design, description of source, country, setting, author, and cancer type), along with descriptions of the attributes and impacts of CCCs, were extracted into a Microsoft Word data extraction form (developed specifically for the review) chronologically by one author (EB) and checked for accuracy by a second author (CT). Discrepancies were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached. Where there were missing data, the authors contacted the corresponding authors of the relevant articles for more information.

Findings were synthesized via narrative analysis [17] overall, and according to decade of publication (2002–2009, 2010–2019, 2020–2024) by doctorally prepared researchers each with over 20 years of clinical experience (CT, EB). Data on attributes and impacts of CCCs were extracted from the text of included sources and coded, categorized, and themed inductively [18]. Themes relating to attributes and impacts of CCC were synthesized to understand interrelated concepts. Within the analysis, focus was placed on identifying the defining features of CCCs and the anticipated versus realized impacts, and how they have evolved over time (from the earliest available evidence onwards). Quality assessment was not conducted as is standard in scoping reviews.

3. Results

3.1. Included Sources

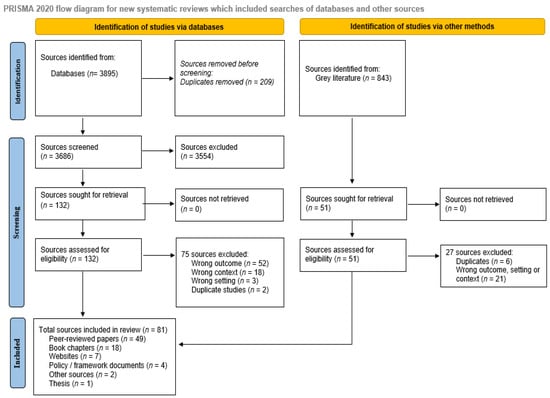

Of the 3895 records identified from databases and 843 records from the gray literature, a total of 81 sources were included (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Scoping review PRISMA flow diagram.

Sources included 49 peer-reviewed articles [3,4,5,10,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56], 18 book chapters (in two books) [57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74], 7 websites [11,75,76,77,78], 4 policy/framework documents [79,80,81], 2 white papers [82,83], and 1 thesis [84] (Table 2). The 49 peer-reviewed articles consisted of 26 opinion pieces, commentaries, or reviews [5,10,26,30,34,35,36,38,39,42,45,47,48,50,54], 13 observational studies [20,52,53], and 10 mixed methods or qualitative studies [3,4,5,10,11,21,22,23,25,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,36,37,40,41,45,46,49,51,76,77,79,81,82,84]. Most studies (n = 42, 56%) were published from 2020 onwards [3,10,13,40,42,43,44,45,47,49,50,52,53,54,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,81,82,85,86,87,88,89,90,91].

Table 2.

Summary of included sources in scoping review.

The purpose of the sources varied widely: 21 (17%) provided practical guidance on development of CCCs; [57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,80] 17 (14%) described characteristics, services, or practices of CCCs [10,24,26,27,30,39,43,44,50,51,53,74,80,89,90,91,94]; 10 (8%) reported on clinical service provision in CCCs [10,24,25,26,27,30,40,41,43,44,48,50,51,53]; and nine (7%) focused on vision and roles of CCCs [20,34,35,38,39,42,45,47,49]. Supplementary File S3 displays characteristics of included sources. Sources were predominantly focused on CCCs in Europe (n = 34, 42%) [3,4,5,10,11,13,21,22,23,25,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,36,37,40,41,45,46,49,51,76,77,79,81,82,84,85,87,88], or USA (n = 23, 28%) [20,24,34,35,38,39,42,43,44,47,48,50,52,53,54,55,56,75,78,89,90,91,93]. Four sources focused on low- or middle-income countries including: a network between CCCs in a high- and middle-income country (UK and India) [19]; a CCC model within a low-income country (Africa) [94]; guidance on development of CCCs in countries with limited resources [65]; and description of a global program where CCCs in the USA support cancer control in low- and middle-income countries [93].

3.2. Attributes and Impacts of CCCs

Key attributes and anticipated and/or realized impacts of CCCs were identified under the following themes: (1) clinical service provision; (2) research, data, and innovation; (3) education and clinical support; (4) networks and leadership; (5) health equity and inclusiveness; and (6) accountability and governance. Table 3 displays the attributes and impacts of CCCs under the key themes, as reported across all sources (n = 81) (see Supplementary File S4 for more detail).

Table 3.

Reported attributes and impacts of CCCs, reported under key themes.

Table 4 provides a summary of the characteristics of current CCC accreditation and designation programs.

Table 4.

Characteristics of current CCC accreditation and designation programs.

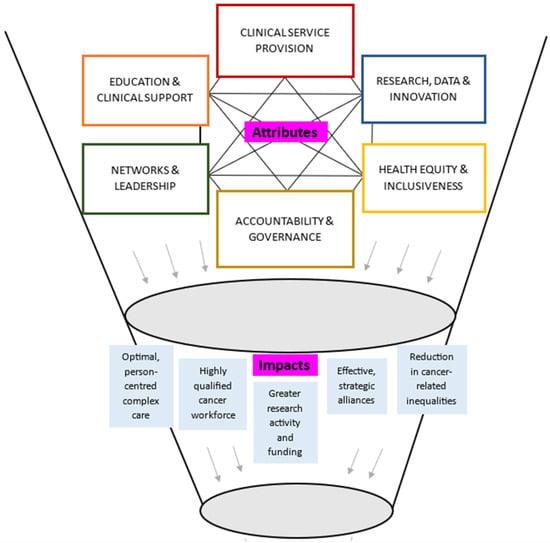

3.3. Synthesis of Attributes and Impacts of CCCs

Figure 2 displays a theoretical model of the key attributes and anticipated impacts of CCCs, informed by narrative synthesis of the largely opinion-based included sources. The synthesis highlighted that the core attributes of CCCs were likely interconnected and interdependent. An example of this was that high-quality clinical service provision could be underpinned by excellence in research and innovation. CCCs were reported to conduct clinically relevant research from the bench-to-bedside, and back again through multispecialty and multidisciplinary teams, and access to high patient numbers across the cancer trajectory. This research was then able to be directly translated into practice via education and clinical support, both within the CCC, and within local, national, or international networks. Networks and leadership could enable collaboration and sharing of resources to support research and innovation, education and clinical support, and health equity and inclusiveness, by addressing needs of the local population and focusing on rare types of cancers. Excellent standards across the attributes could be supported via accountability and governance, particularly through accreditation and designation programs.

Figure 2.

Theoretical model synthesizing attributes and impacts of CCCs.

Synergistic impacts of CCCs were reported to be mostly aligned with core attributes. Optimal person-centered complex care could be enabled by a highly qualified cancer workforce. Effective and strategic alliances could lead to greater research activity and funding and improve cancer-related outcomes. Figure 2 does not represent all possible reported or anticipated impacts (see Table 3 for a breakdown of attributes and impacts of CCCs).

3.4. Primary Research

Table 5 outlines findings in the 24 sources that reported observational primary research, which focused on health equity (grant schemes, community engagement, and access to care) (n = 7) [34,35,38,39,42], availability of clinical services in CCCs (n = 6) [26,30,34,35,45,47], website content of CCCs (n = 3) [38,39,42], secondary analyses of accreditation data (n = 3) [5,10,53], and benefits of second opinions at CCCs (n = 2) [52,85]. Of note, one study reported no difference in cancer prevention measures in designated CCCs compared to non-CCCs [10], despite several sources stating that cancer prevention was a core concern of CCCs [13,28,80,88]. All observational studies were descriptive, with the exception of five exploratory studies, which reported CCCs were associated with greater academic output [48], higher rates of participation in clinical trials [91], and improved treatment plans in second opinions [52], but lack of equitable access to care [55,56].

Table 5.

Results of primary research.

3.5. Changes in the CCC Literature over Time

Table 6 provides a summary of the CCC literature in various time periods for each of the themes. The few sources (n = 4) published between 2002 and 2009 described early establishment of CCCs [26], initiation of accreditation and designation programs [4], and strategies for CCCs to align with cancer control programs [79]. The literature from 2010 to 2019 (n = 28) explored clinical service provision of CCCs [20,25,34,35] (with a focus on supportive and integrative care services) [27,34,38,39] and research opportunities for CCCs (between CCC networks, and greater focus on translational research) [48]. The literature on the growth and development of networks (between CCCs, and CCCs and community organizations) [19,22,33,37] and accreditation and designation programs [5,21,29,31,32], and barriers in equitable access to care, were also reported in 2010–2019. Recently (2020–2024), the literature on CCCs has increased exponentially (n = 42) and focused on a range of issues across all identified attributes of CCCs. The recent literature has highlighted the need for CCCs to focus on networks and leadership, to address health equity and inclusiveness (Table 6).

Table 6.

Summary of changes in the CCC literature across time, according to themes.

4. Discussion

This review reports findings of a comprehensive search and synthesis of 81 published and unpublished sources describing the key attributes and (largely anticipated) impact of CCCs, and chronological changes in the CCC literature. The evolution of the CCC literature has reflected the progress of CCCs over time; from articulation of vision; to development of centers (and larger scale deployment of CCC), services, systems, and programs; and to a focus on areas for improvement. Changes in the CCC literature have also reflected an increasing focus on supportive and integrative care, in line with a greater understanding of the benefits of such services and the recognition of cancer as a chronic illness [1,2,81]. The most notable development in the CCC literature was a recognition of issues surrounding health equity, and subsequent development of strategies to address the issue at a local, national, and international level. This work is significant, timely, and can inform the development and improvement of CCCs within particular health systems internationally, which are regarded as vital in addressing the burden of cancer globally [1,2,81]. Most sources were opinion pieces and therefore findings must be interpreted through this lens.

4.1. Attributes and Impacts

Key, interdependent attributes of CCCs were found across six themes: (1) clinical service provision; (2) education and clinical support; (3) research, data, and innovation; (4) health equity and inclusiveness; (5) networks and leadership; and (6) accountability and governance (Figure 2). While many of these attributes are accepted as core components of comprehensive cancer care and substantiate and build upon the WHO-IAEA Framework [96], the symbiotic relationship of these attributes in CCCs is yet to be fully explored. The literature indicates that CCCs serve as a nexus, where the core attributes of CCCs are intimately linked and needed for CCCs to reach their full potential. Evidence is lacking on the importance of having all attributes present within a standalone CCC, or if such attributes can successfully be provided within a networked approach. Although reported as ideal [4,26], the presence of all attributes in a single physical location may not be feasible or realistic in many countries, requiring networking and alliances of infrastructure and services [83]. The concept of CCCs has evolved from standalone CCCs, to include approaches with CCCs as core elements within comprehensive cancer networks—with an increased obligation on the CCC to drive improvements of care for all [92]. Our findings suggest that the success of CCCs lies in having all six attributes present in some form (potentially drawing on a networked approach), to produce synergistic impacts both within and beyond the CCC.

The literature describes the ambitious goals set out for CCCs, often aligned with the objectives of national or international cancer control plans [1,2,81]. These goals included providing equal access to high-quality cancer care [4,76], education, support, and training for cancer clinicians beyond the CCC, to foster and accelerate transdisciplinary state-of-the-art clinical research, and translation across the cancer trajectory [1,4,76]. In the US, the initial purpose of CCCs was to bring research findings to the greatest number of people as quickly as possible [1]. Our findings highlight the synergistic impacts of CCCs that were anticipated to flow on from core attributes of CCCs. Largely opinion-based sources reported that CCCs can lead to a broad range of positive impacts, including delivery of optimal, person-centered, complex care; a highly qualified cancer workforce; greater research activity and funding; effective, strategic alliances; and reduction in cancer-related inequalities. A framework is needed to assess the impacts of CCCs and justify current and future investment.

Most sources in this review were set in countries that participated in accreditation and designation programs that subjectively assessed the presence of attributes and quality markers of CCCs. Accreditation criteria were viewed as valuable as they defined the essential components and prescribed standards, distinguishing CCCs from other types of cancer centers [1,11,76,77,82]. The impacts of accreditation and designation programs were reported to include defining excellence [11,75,76], increased academic output of clinical staff [48], identification of strengths and weaknesses of a center to inform improvement efforts [36], and greater collaboration between designated centers [11,75,76]. While the USA and European countries have long-standing, robust accreditation, and designation systems for CCCs [7,97], this is not the case in all countries with CCCs [26,92]. It is acknowledged that formal (or mandatory) accreditation and designation programs may not be practical, feasible, or desired in all countries. We emphasize it is vital for all CCCs to have key performance indicators within systems of accountability and governance, to define the attributes of CCCs, benchmark outcomes, promote standards of excellence, and define the role of CCCs within the wider provision of cancer services.

The anticipated impacts of CCCs are well described in the international literature, but to date, are largely unsubstantiated in empirical research. The 24 peer review studies in this review largely reported descriptions of availability of clinical services and patient resources [20,34,35,38,42,45,47,85]. Although three primary research studies reported observed benefits associated with CCCs [48,52,91], two studies reported CCCs were associated with inequitable access to care [55,56]. In relation to the original intent of CCCs in the USA, unanswered questions remain in the peer-reviewed literature regarding 1) the extent that investment in discovery and testing of new treatments in CCCs leads to widescale spread through engagement between CCCs and external organizations; and 2) the wider impact of CCCs on cancer outcomes for the population. More research is desperately needed exploring the impact of CCCs, particularly within different government healthcare funding models, to guide their role within the overall health system. A recent systematic review of patient-relevant outcomes, conducted by the authorship team, reported superior mortality and survival, and quality of care outcomes, in CCCs compared to non-CCCs [16]. Studies reporting health equity and cost outcomes favored non-CCCs over CCCs, and there was a dearth of literature focused on symptoms, health-related quality of life, treatment experience, and economic evaluation [16]. Future research is needed to understand if the goals of CCCs are being realized, and if this leads to positive impacts at a societal, organizational, provider, and patient level.

4.2. Opportunities and Drivers for Change

The results of this review suggest that networks are, and will continue to be, key drivers of interconnected improvements in comprehensive cancer care at a regional, national, and international level through a “systems-thinking” approach. Networking between CCCs was described across Europe [11,76], Germany [82], USA [78], and India [19], to support and enable government policy, innovative and equitable high-quality research, and improved patient outcomes. Networks of CCCs played a key role in developing best-practice guidelines [78] and patient pathways that can support standardized high-quality care [98]. Research networks between CCCs can enable multi-center, large-scale research to be conducted, such as longitudinal studies, registries, and biobanks, which can lead to breakthroughs for rare cancers and minority/vulnerable populations [25,99]. Descriptions of networked approaches to comprehensive cancer care in low- and middle-income countries were described in the recent literature [94,95].

The literature highlighted health equity and inclusiveness is an opportunity area for CCCs to focus improvement efforts. Inequities surrounding access to care [56] and clinical trials [91] in CCCs in high-income countries were reported in included sources in this review, and substantiated by findings of our recent systematic review [16]. Explicit approaches are needed to combat health equity and demonstrate measurable differences. Governments in the US and Europe have published formalized health equity agendas, describing clear strategies to address health disparities [13,43,44,89,90]. Similarly, a key focus of the new Australian Cancer Plan is improving equitable access and outcomes [100]. In the European Union, networked CCCs are driving Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan with a goal for all members states to have at least one accredited CCC by 2025 as part of the European Network of CCCs [11]. In the US, where CCCs are positioned within the healthcare free market, NCI-designated CCCs must demonstrate corporate social responsibility and citizenship, and attract and retain patients from minority backgrounds equal or higher to their representation in the population [101]. Lengthy, expensive treatments that are far from home may be difficult to afford for people with limited cover from health insurance policies [101]. Local networks where CCCs reach out into the community may help to address this issue. However, national healthcare policy changes are also required in the US to support equitable access to care [101].

A “hub-and-spoke” networked approach to delivery of comprehensive cancer care is an alternative approach for CCCs to achieve their goals and function effectively as important “cogs” in cancer control efforts [9]. For practical reasons, CCCs cannot be ubiquitous geographically and across the cancer trajectory, and most people with cancer will not receive care in a CCC [51]. There are many advantages to receiving care close to home or in a smaller community setting, which is often more accessible and can provide appropriate and high-quality care at lower cost and less inconvenience to patients and families [102]. A networked approach to comprehensive cancer care that positions a CCC as the hub within a geographical region, working with smaller, community health service providers and local health care teams, can serve the individual needs of the community or population and provide equitable access to care. This approach to cancer infrastructure and services can be a viable solution to countries with geographical disparate populations [92] or those lacking the substantial resources that are required to build stand-alone CCCs [94]. In any resource setting, CCCs may be best suited to provide care for certain patients based on clinical need. Notably there were little data to suggest that people with lived experience of cancer are significantly involved in the development of CCCs and their services delivery models; this needs to be rectified to ensure a person-centered approach to comprehensive cancer care. These considerations will be important for future framework development and spatial analysis research informing development of CCCs and their networks to support equitable access to high-quality cancer care.

The findings of this review are slanted towards resource-rich settings where CCCs have historically been developed and maintained. Of note, the development of CCCs is not solely resource-dependent, but also contingent on political commitment, policy alignment, and national cancer strategies. We acknowledge that very few sources were found from low- or middle-income countries, including throughout South America, India, or Asian regions. Subsequently, there is underrepresentation of the characteristics and impact of CCCs in portions of the world largely extending care and services to under-served populations. Comprehensive cancer care delivery in resource-constrained settings may be more likely to rely on a networked approach rather than standalone CCCs, to overcome challenges in scarcity of resources. Such models of comprehensive cancer care may also have innovative approaches to provide equitable access to care for priority and under-served populations. As this review focused on CCC, exploration of alternative models of comprehensive cancer care was beyond the scope of this work. However, we acknowledge the importance of further research to understand and strengthen comprehensive cancer care delivery in resource-limited settings.

4.3. Key Recommendations

Based on the findings of this review, we make five key recommendations: (1) focus on all interconnected attributes of CCCs; (2) systems of accountability and governance for CCCs; (3) the need for robust evidence on impact of CCCs; (4) emphasis on networks and networking of CCCs; and (5) continued and increased focus on health equity (Table 7).

Table 7.

Key recommendations based on review findings.

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

Despite efforts to identify all sources and studies reporting attributes and impacts of CCCs, we were limited to including only those that used the term “CCC”, meaning some that were relevant may have been missed. Only sources and studies in English were included, meaning some relevant information may have been missed (i.e., German literature). The exclusion of websites in gray literature searches may have excluded some leading CCCs. For example, there was a notable absence of sources reporting on UK CCCs, which have played a key role in the establishment of accreditation and designation programs [5,36], a local networked approach to equitable comprehensive cancer services [103], and home to a CCC of Excellence as designated by EACS [104]. Importantly, low-and middle-income countries were not well represented, which influences the application of these findings to a large population of cancer care provider settings; this also demonstrates that the development of CCCs in these countries has been slower compared to high-income countries, possibly due to limited resources and low-priority policy agendas. Despite these limitations, our review provides a methodologically rigorous, thorough, up-to-date, and evidence-based summary and synthesis of the international literature around CCCs.

5. Conclusions

Interconnected core attributes and synergistic impacts of CCCs were reported across six themes in mostly opinion-based sources. The results highlight the importance of all attributes and the need for more evidence highlighting the impact of CCCs. The findings also suggest that CCCs are yet to reach their full potential, with anticipated benefits dependent on accountability, effective networking, and focus on health equity at a local, national, and international level. We recommend that countries with well-established, well-resourced comprehensive cancer care networks prioritize equitable partnerships with resource-limited settings. These collaborations should focus on strengthening locally led cancer care, research, innovation, and education to enhance sustainable, high-quality, and accessible cancer services.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cancers17061023/s1, Supplementary File S1. PRISMA checklist, Supplementary File S2. Database search strategies, Supplementary File S3. Condensed data extraction table, Supplementary File S4. Narrative summary of key attributes and impacts of CCCs, Supplementary File S5. Current CCC accreditation and designation programs.

Author Contributions

C.T. (Carla Thamm)—conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; E.B.—conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; J.J.—conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; R.K.—conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; C.P.—conceptualization, supervision, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing—review and editing; M.T.H.—formal analysis, investigation, writing—review and editing; A.C. (Andreas Charalambous)—formal analysis, investigation, writing—review and editing; A.C. (Alexandre Chan)—formal analysis, investigation, writing—review and editing; S.A.—formal analysis, investigation, writing—review and editing: C.T. (Carolyn Taylor)—formal analysis, investigation, writing—review and editing: R.J.C.—conceptualization, supervision, resources, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We want to acknowledge Ellen Griesshammer of the German Cancer Society for providing important background information on comprehensive cancer centers, accreditation and designation programs, and networks in Germany and across Europe.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CCC | Comprehensive cancer center |

| NCI | National Cancer Institute |

| OECI | Organization for European Cancer Institutes |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- National Institute of Health. National Institute of Health (NCI) Mission. Available online: https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/what-we-do/nih-almanac/national-cancer-institute-nci (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- World Health Organisation. National Cancer Control Programmes: Policy and Managerial Guidelines; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ringborg, U.; Berns, A.; Celis, J.E.; Heitor, M.; Tabernero, J.; Schüz, J.; Baumann, M.; Henrique, R.; Aapro, M.; Basu, P.; et al. The Porto European Cancer Research Summit 2021. Mol. Oncol. 2021, 15, 2507–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringborg, U.; Pierotti, M.; Storme, G.; Tursz, T. Managing cancer in the EU: The Organisation of European Cancer Institutes (OECI). Eur. J. Cancer 2008, 44, 772–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghatchian, M.; Thonon, F.; Boomsma, F.; Hummel, H.; Koot, B.; Harrison, C.; Rajan, A.; de Valeriola, D.; Otter, R.; Laranja Pontes, J.; et al. Pioneering quality assessment in European cancer centers: A data analysis of the organization for European cancer institutes accreditation and designation program. J. Oncol. Pract. 2014, 10, e342–e349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirohi, B.; Chalkidou, K.; Pramesh, C.; Anderson, B.O.; Loeher, P.; El Dewachi, O.; Shamieh, O.; Shrikhande, S.V.; Venkataramanan, R.; Parham, G. Developing institutions for cancer care in low-income and middle-income countries: From cancer units to comprehensive cancer centres. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, e395–e406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute. NCI-Designated Cancer Centers. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/research/infrastructure/cancer-centers (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- EU Health Support. Mapping of Comprehensive Cancer Infrastructures. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/document/download/6bbdb89a-1766-4c29-bc8e-3ad663bdefdc_en (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Sullivan, R. Has the US Cancer Centre model been ‘successful’? Lessons for the European cancer community. Mol. Oncol. 2009, 3, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kehrloesser, S.; Oberst, S.; Westerhuis, W.; Wendler, A.; Wind, A.; Blaauwgeers, H.; Burrion, J.B.; Nagy, P.; Saeter, G.; Gustafsson, E.; et al. Analysing the attributes of comprehensive cancer centres and cancer centres across Europe to identify key hallmarks. Mol. Oncol. 2021, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CraNE. European Network of Comprehensive Cancer Centres. Available online: https://crane4health.eu/ (accessed on 15 November 2023).

- National Cancer Institute. Elimiate inequiteies—National Cancer Plan. Available online: https://nationalcancerplan.cancer.gov/goals/eliminate-inequities (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Ringborg, U.; von Braun, J.; Celis, J.; Baumann, M.; Berns, A.; Eggermont, A.; Heard, E.; Heitor, M.; Chandy, M.; Chen, C.J. Strategies to decrease inequalities in cancer therapeutics, care and prevention: Proceedings on a conference organized by the Pontifical Academy of Sciences and the European Academy of Cancer Sciences, Vatican City, February 23–24, 2023. Mol. Oncol. 2024, 18, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thamm, C.; Button, E.; Johal, J.; Knowles, R.; Gulyani, A.; Paterson, C.; Halpern, M.T.; Charalambous, A.; Chan, A.; Aranda, S.; et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of patient-relevant outcomes in comprehensive cancer centers versus noncomprehensive cancer centers. Cancer 2025, 131, e35646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhera, J. Narrative reviews: Flexible, rigorous, and practical. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2022, 14, 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.R. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am. J. Eval. 2006, 27, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, R.; Finlayson, A.; Indox Cancer Research Network. Building capacity for clinical research in developing countries: The INDOX Cancer Research Network experience. Glob. Health Action. 2012, 5, 17288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayman, M.L.; Harper, M.M.; Quinn, G.P.; Reinecke, J.; Shah, S. Oncofertility resources at NCI-designated comprehensive cancer centers. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2013, 11, 1504–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deriu, P.L.; La Pietra, L.; Pierotti, M.; Collazzo, R.; Paradiso, A.; Belardelli, F.; De Paoli, P.; Nigro, A.; Lacalamita, R.; Ferrarini, M.; et al. Accreditation for excellence of cancer research institutes: Recommendations from the Italian Network of comprehensive cancer centers. Tumori 2013, 99, 293e–298e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggermont, A.M.; Caldas, C.; Ringborg, U.; Medema, R.; Tabernero, J.; Wiestler, O. Cancer Core Europe: A consortium to address the cancer care-cancer research continuum challenge. Eur. J. Cancer 2014, 50, 2745–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggermont, A.M.M.; Apolone, G.; Baumann, M.; Caldas, C.; Celis, J.E.; de Lorenzo, F.; Ernberg, I.; Ringborg, U.; Rowell, J.; Tabernero, J.; et al. Cancer Core Europe: A translational research infrastructure for a European mission on cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2019, 13, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.L. Mind, body and spirit: Comprehensive cancer centers emphasize treating the whole person. ASRT (Am. Soc. Radiol. Technol.) Scanner 2004, 36, 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Pelagio, G.; Pistillo, D.; Mottolese, M. Minimum biobanking requirements: Issues in a comprehensive cancer center biobank. Biopreserv. Biobank. 2011, 9, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soo, K.C. Role of comprehensive cancer centres during economic and disease transition: National Cancer Centre, Singapore—A case study. Lancet Oncol. 2008, 9, 796–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Harten, W.H.; Paradiso, A.; Le Beau, M.M. The role of comprehensive cancer centers in survivorship care. Cancer 2013, 119, 2200–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adami, H.O.; Berns, A.; Celis, J.E.; de Vries, E.; Eggermont, A.; Harris, A.; Zur Hausen, H.; Pelicci, P.G.; Ringborg, U. European Academy of Cancer Sciences: Position paper. Mol. Oncol. 2018, 12, 1829–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ancarani, V.; Bernabini, M.; Zani, C.; Altini, M.; Amadori, D. The Comprehensive Cancer Care Network of Romagna: The opportunities generated by the OECI accreditation program. Tumori 2015, 101 (Suppl. S1), S55–S59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berendt, J.; Stiel, S.; Simon, S.T.; Schmitz, A.; van Oorschot, B.; Stachura, P.; Ostgathe, C. Integrating palliative care into comprehensive cancer centers: Consensus-based development of best practice recommendations. Oncologist 2016, 21, 1241–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canitano, S.; Di Turi, A.; Caolo, G.; Pignatelli, A.C.; Papa, E.; Branca, M.; Cerimele, M.; De Maria, R. The Regina Elena National Cancer Institute process of accreditation according to the standards of the Organisation of European Cancer Institutes. Tumori 2015, 101 (Suppl. S1), S51–S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Pieve, L.; Collazzo, R.; Masutti, M.; De Paoli, P. The OECI model: The CRO Aviano experience. Tumori 2015, 101 (Suppl. S1), S10–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paoli, P.; Ciliberto, G.; Ferrarini, M.; Pelicci, P.; Dellabona, P.; De Lorenzo, F.; Mantovani, A.; Musto, P.; Opocher, G.; Picci, P.; et al. Alliance Against Cancer, the network of Italian cancer centers bridging research and care. J. Transl. Med. 2015, 13, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, S.L.; Clark, K.; Grant, M.; Loscalzo, M.J. Seventeen years of progress for supportive care services: A resurvey of National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer centers. Palliat. Support. Care 2015, 13, 917–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platek, M.E.; Johnson, J.; Woolf, K.; Makarem, N.; Ompad, D.C. Availability of outpatient clinical nutrition services for patients with cancer undergoing treatment at comprehensive cancer centers. J. Oncol. Pract. 2015, 11, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, A.; Berns, A.; Ringborg, U.; Celis, J.; Ponder, B.; Caldas, C.; Livingston, D.; Bristow, R.G.; Hecht, T.T.; Tursz, T.; et al. Excellent translational research in oncology: A journey towards novel and more effective anti-cancer therapies. Mol. Oncol. 2016, 10, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, W. Health systems, quality of health care, and translational cancer research: The role of the Istituto Superiore Sanità—Rome. Tumori 2015, 101 (Suppl. S1), S67–S68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolland, B.; Eschler, J. Searching for survivor-specific services at NCI-designated comprehensive cancer centers: A qualitative assessment. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2018, 16, 839–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, H.; Sun, L.; Mao, J.J. Growth of integrative medicine at leading cancer centers between 2009 and 2016: A systematic analysis of NCI-designated comprehensive Cancer Center Websites. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2017, 2017, lgx004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berns, A.; Ringborg, U.; Celis, J.E.; Heitor, M.; Aaronson, N.K.; Abou-Zeid, N.; Adami, H.O.; Apostolidis, K.; Baumann, M.; Bardelli, A.; et al. Towards a cancer mission in Horizon Europe: Recommendations. Mol. Oncol. 2020, 14, 1589–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandts, C.H. Innovating the outreach of comprehensive cancer centers. Mol. Oncol. 2019, 13, 619–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, K.; Liou, K.; Liang, K.; Seluzicki, C.; Mao, J.J. Availability of integrative medicine therapies at National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer centers and community hospitals. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2021, 27, 1011–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doykos, P.M.; Chen, M.S., Jr.; Watson, K.; Henderson, V.; Baskin, M.L.; Downer, S.; Smith, L.A.; Bhavaraju, N.; Dina, S.; Lathan, C.S. Special convening and listening session on health equity and community outreach and engagement at National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer centers. Health Equity 2021, 5, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doykos, P.M.; Chen, M.S., Jr.; Watson, K.; Henderson, V.; Baskin, M.L.; Downer, S.; Smith, L.A.; Bhavaraju, N.; Dina, S.; Lathan, C.S. Recommendations from a dialogue on evolving National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer center community outreach and engagement requirements: A path forward. Health Equity 2021, 5, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahr, S.; Lödel, S.; Berendt, J.; Thomas, M.; Ostgathe, C. Implementation of best practice recommendations for palliative care in German comprehensive cancer centers. Oncologist 2020, 25, e259–e265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joos, S.; Nettelbeck, D.M.; Reil-Held, A.; Engelmann, K.; Moosmann, A.; Eggert, A.; Hiddemann, W.; Krause, M.; Peters, C.; Schuler, M.; et al. German Cancer Consortium (DKTK): A national consortium for translational cancer research. Mol. Oncol. 2019, 13, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, M.; Henry, E.; McCann, K.; Karuturi, M.S.; Bustamante Alvarez, J.G.; Parkes, A.; Wesolowski, R.; Wei, M.; Mougalian, S.S.; Durm, G.; et al. Making national cancer institute-designated comprehensive cancer center knowledge accessible to community oncologists via an online tumor board: Longitudinal observational study. JMIR Cancer 2022, 8, e33859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.J.; Misra, S.; Chen, H.; Bell, T.M.; Koniaris, L.G.; Valsangkar, N.P. National Cancer Institute centers and Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Research synergy. J. Surg. Res. 2019, 236, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, M.; Davies, L.; Oberst, S.; Oliver, K.; Eggermont, A.; Schmutz, A.; La Vecchia, C.; Allemani, C.; Lievens, Y.; Naredi, P.; et al. European Groundshot-addressing Europe’s cancer research challenges: A Lancet Oncology Commission. Lancet Oncol. 2023, 24, e11–e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, N.M.; Hsieh, A.; Ramanadhan, S.; Lee, R.M.; Emmons, K.M. The prevalence of dissemination and implementation research and training grants at National Cancer Institute-designated cancer centers. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2022, 6, pkab092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oberst, S. Bridging research and clinical care: The comprehensive cancer centre. Mol. Oncol. 2019, 13, 614–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasick, R.J.; Campbell, B.; Rugo, H.S.; Dillard, C.; Harris, M.; Joseph, G. Unlocking the vault: Can 2nd opinions by comprehensive cancer center breast oncologistsimprove treatment quality for African Americans? Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2020, 29, d078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, D.; Reynolds Kueny, C.; Anderson, M. Impact of merging into a comprehensive cancer center on health care teams and subsequent team-member and patient experiences. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2022, 19, e78–e91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaniz, M.; Rebbeck, T.R. The role of community outreach and engagement in evaluation of NCI Cancer Center Support Grants. Cancer Causes Control 2023, 35, 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamlyn, G.S.; Hutchins, K.E.; Johnston, A.L.; Thomas, R.T.; Tian, J.; Kamal, A.H. Accessibility and barriers to oncology appointments at 40 National Cancer Institute–designated comprehensive cancer centers: Results of a mystery shopper project. J. Oncol. Pract. 2016, 12, e884–e900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirtane, K.; Zhao, Y.; Amorrortu, R.P.; Fuzzell, L.N.; Vadaparampil, S.T.; Rollison, D.E. Demographic disparities in receipt of care at a comprehensive cancer center. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 13687–13700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcantara, G.; Chao, N.J. Administrative support. In The Comprehensive Cancer Center: Development, Integration and Implementation; Aljurf, M., Majhail, N.S., Koh, M.B.C., Kharfran-Dabaja, M.A., Chao, N.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Aldehaim, M.; Phan, J. Proposal for establishing a new radiotherapy facility. In The Comprehensive Cancer Center: Development, Integration and Implementation; Aljurf, M., Majhail, N.S., Koh, M.B.C., Kharfran-Dabaja, M.A., Chao, N.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Babar, A.; Montero, A.J. Building quality from the ground up in a cancer center. In The Comprehensive Cancer Center: Development, Integration and Implementation; Aljurf, M., Majhail, N.S., Koh, M.B.C., Kharfran-Dabaja, M.A., Chao, N.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, R.; Majhail, N.S.; Abraham, J. Psychosocial and patient support services in comprehensive cancer centers. In The Comprehensive Cancer Center: Development, Integration and Implementation; Aljurf, M., Majhail, N.S., Koh, M.B.C., Kharfran-Dabaja, M.A., Chao, N.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Chew, L.; Thum, M.C.M. Pharmacy requirements for a comprehensive cancer center. In The Comprehensive Cancer Center: Development, Integration and Implementation; Aljurf, M., Majhail, N.S., Koh, M.B.C., Kharfran-Dabaja, M.A., Chao, N.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, K.M.; Klammer, M.; Koh, M.B.C. Laboratory/pathology services and blood bank. In The Comprehensive Cancer Center: Development, Integration and Implementation; Aljurf, M., Majhail, N.S., Koh, M.B.C., Kharfran-Dabaja, M.A., Chao, N.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Frith, J.; Chao, N.J. Oncology nursing care. In The Comprehensive Cancer Center: Development, Integration and Implementation; Aljurf, M., Majhail, N.S., Koh, M.B.C., Kharfran-Dabaja, M.A., Chao, N.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Grosso, D.; Aljurf, M.; Gergis, U. Building a comprehensive cancer center: Overall structure. In The Comprehensive Cancer Center: Development, Integration and Implementation; Aljurf, M., Majhail, N.S., Koh, M.B.C., Kharfran-Dabaja, M.A., Chao, N.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hashmi, S.K.; Geara, F.; Mansour, A.; Aljurf, M. Cancer management at sites with limited resources: Challenges and potential solutions. In The Comprehensive Cancer Center: Development, Integration and Implementation; Aljurf, M., Majhail, N.S., Koh, M.B.C., Kharfran-Dabaja, M.A., Chao, N.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 173–185. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, F.; Alhayli, S.; Aljurf, M. Data unit, translational reserach, and registries. In The Comprehensive Cancer Center: Development, Integration and Implementation; Aljurf, M., Majhail, N.S., Koh, M.B.C., Kharfran-Dabaja, M.A., Chao, N.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 157–165. [Google Scholar]

- Kharfan-Dabaja, M.A. The infusion center. In The Comprehensive Cancer Center: Development, Integration and Implementation; Aljurf, M., Majhail, N.S., Koh, M.B.C., Kharfran-Dabaja, M.A., Chao, N.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kharfan-Dabaja, M.A. The inpatient unit in a cancer center. In The Comprehensive Cancer Center: Development, Integration and Implementation; Aljurf, M., Majhail, N.S., Koh, M.B.C., Kharfran-Dabaja, M.A., Chao, N.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Majhail, N.S.; De Lima, M. Transplantation and cellular therapy. In The Comprehensive Cancer Center: Development, Integration and Implementation; Aljurf, M., Majhail, N.S., Koh, M.B.C., Kharfran-Dabaja, M.A., Chao, N.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 121–133. [Google Scholar]

- Murthy, H.S.; Manochakian, R.; Kharfan-Dabaja, M.A. Education and training. In The Comprehensive Cancer Center: Development, Integration and Implementation; Aljurf, M., Majhail, N.S., Koh, M.B.C., Kharfran-Dabaja, M.A., Chao, N.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 167–172. [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker, L.; McInnes, S. Starting a palliative care program at a cancer center. In The Comprehensive Cancer Center: Development, Integration and Implementation; Aljurf, M., Majhail, N.S., Koh, M.B.C., Kharfran-Dabaja, M.A., Chao, N.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, I.Q.; Lim, F.L.W.I.; Koh, L.P. Outpatient care. In The Comprehensive Cancer Center: Development, Integration and Implementation; Aljurf, M., Majhail, N.S., Koh, M.B.C., Kharfran-Dabaja, M.A., Chao, N.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Yassine, F.; Kharfan-Dabaja, M.A. Patient resources in a cancer centre. In The Comprehensive Cancer Center: Development, Integration and Implementation; Aljurf, M., Majhail, N.S., Koh, M.B.C., Kharfran-Dabaja, M.A., Chao, N.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 145–155. [Google Scholar]

- Gospodarowicz, M.; Trypuc, J.; D’Cruz, A.; Khader, J.; Omar, S.; Knaul, F. Cancer services and the comprehensive cancer center. In Disease Control Priorities, 3rd ed.; Gelband, H., Jha, P., Sankaranarayanan, R., Horton, S., Eds.; The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; pp. 195–210. [Google Scholar]

- NCI, Toocca. NIH National Cancer Institute: Office of Cancer Centers. Available online: https://cancercenters.cancer.gov/ (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Organisation European Cancer Institute. OECI. Available online: https://www.oeci.eu/ (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Czech Cancer Centre Network. Criteria Defining the Status of Comprehensive Cancer Centre. Available online: https://www.linkos.cz/english-summary/national-cancer-control-programme/czech-cancer-centre-network/criteria-defining-the-status-of-comprehensive-cancer-centre/ (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/ (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- World Health Organization. Towards a Strategy for Cancer Control in the Eastern Mediterrean Region; Regional Office for Eastern Mediteranean: Cairo, Egypt, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, R.; Khalfan, A.; Abdelmutti, N.; Chudak, A.; Trypuc, J.; Gospodarowicz, M. Cancerpedia; Princess Margaret Cancer Center: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Oberst, S.; Poortmans, P.; Aapro, M.; Philip, T. Comprehensive Cancer Care Across the EU: Advancing the Vision; European Cancer Organisation: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- German Cancer Aid. Program for the Development of Interdisciplinary Oncology Centres of Excellence in Germany: 10th Call for Applications; Deutsche Krebshilfe: Berlin, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- McArthur, G. VCCC Alliance submission to the Australian Government Department of the Treasury; Victorian Comprehensive Cancer Centre Alliance: Melbourne, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rajan, A. Assessing Translational Research Excellence in European Comprehensive Cancer Centre; University of Twente: Enschede, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schulmeyer, C.E.; Beckmann, M.W.; Fasching, P.A.; Häberle, L.; Golcher, H.; Kunath, F.; Wullich, B.; Emons, J. Improving the Quality of Care for Cancer Patients through Oncological Second Opinions in a Comprehensive Cancer Center: Feasibility of Patient-Initiated Second Opinions through a Health-Insurance Service Point. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VCCC Alliance. Annual Reports. Available online: https://vcccalliance.org.au/about-us/governance-and-management/annual-reports/ (accessed on 19 September 2023).

- Berns, A. Academia and society should join forces to make anti-cancer treatments more affordable. Mol. Oncol. 2024, 18, 1351–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fervers, B.; Pérol, O.; Lasset, C.; Moumjid, N.; Vidican, P.; Saintigny, P.; Tardy, J.; Biaudet, J.; Bonadona, V.; Triviaux, D. An Integrated Cancer Prevention Strategy: The Viewpoint of the Leon Berard Comprehensive Cancer Center Lyon, France. Cancer Prev. Res. 2024, 17, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odedina, F.T.; Salinas, M.; Albertie, M.; Murrell, D.; Munoz, K. Operational strategies for achieving comprehensive cancer center community outreach and engagement objectives: Impact and logic models. Arch. Public. Health 2024, 82, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapl, E.S.; Koopman Gonzalez, S.; Austin, K. A framework for building comprehensive cancer center’s capacity for bidirectional engagement. Cancer Causes Control 2024, 35, 963–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, J.M.; Shulman, L.N.; Facktor, M.A.; Nelson, H.; Fleury, M.E. National estimates of the participation of patients with cancer in clinical research studies based on Commission on cancer accreditation data. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 2139–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Australia. Australian Comprehensive Cancer Network. Available online: https://www.canceraustralia.gov.au/key-initiatives/accn (accessed on 27 June 2024).

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Global Program. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/global/global-program (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Jatho, A.; Kibudde, S.; Orem, J. An Approach to Comprehensive Cancer Control in low- and Middle-Income Countires: The Ugandan Model. Available online: https://connection.asco.org/magazine/asco-international/approach-comprehensive-cancer-control-low-and-middle-income-countries (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Aljurf, M.; Majhail, N.S.; Koh, L.P.; Kharfan-Dabaja, M.A.; Chao, N.J.e. The Comprehensive Cancer Center: Development, Integration and Implementation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. Setting Up a Cancer Centre: A WHO–IAEA Framework; World Health Organisation: Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Griesshammer, E.; Wesselmann, S. European Cancer Centre Certification Programme: A European way to quality of cancer care. Der Gynäkol. 2019, 52, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- iPAAC. Patient Pathways for Comprehensive Cancer Networks. Available online: https://www.ipaac.eu/news-detail/en/59-patient-pathways-for-comprehensive-cancer-care-networks/ (accessed on 26 March 2024).

- Riegman, P.H.; Morente, M.M.; Betsou, F.; De Blasio, P.; Geary, P.; Marble Arch International Working Group on Biobanking for Biomedical Research. Biobanking for better healthcare. Mol. Oncol. 2008, 2, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Australia. Australian Cancer Plan; Cancer Australia: Surry Hills, NSW, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sultan, D.H.; Gishe, J.; Hanciles, A.; Comins, M.M.; Norris, C.M. Minority use of a National Cancer Institute-Designated Comprehensive Cancer Center and non-specialty hospitals in two Florida regions. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2015, 2, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norden, A. Why cancer centres of excllence may not be right for every patient. MedCity News, 14 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Expert Advisory Group on Cancer; Calman, K.C.; Hine, D. A Policy Framework for Commissioning Cancer Services: A Report by the Expert Advisory Group on Cancer to the Chief Medical Officers of England and Wales: Guidance for Purchasers and Providers of Cancer Services; Department of Health: Hong Kong, China, 1995.

- University of Cambridge. Cambridge First UK Centre to Be Given ‘Comprehensive Cancer Centre of Excellence’. Available online: https://www.cam.ac.uk/news/cambridge-first-uk-centre-to-be-given-comprehensive-cancer-center-of-excellence (accessed on 21 March 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).