The Effect of Lifestyle on the Quality of Life of Vulvar Cancer Survivors

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

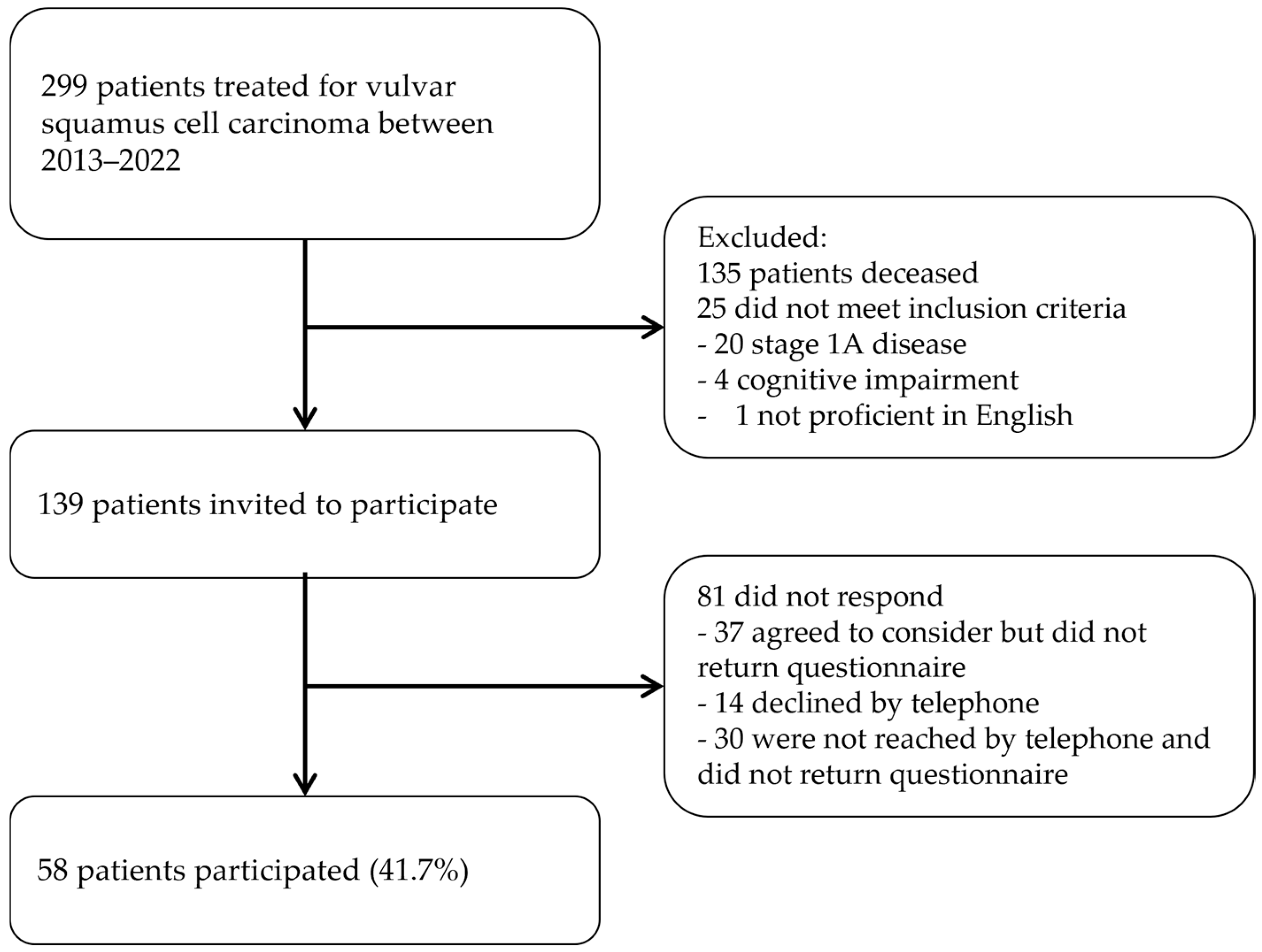

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Outcomes Measures

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HPV | Human Papilloma virus |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| FIGO | International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics |

| ASA | American Society of Anesthesiologists |

| LSI | Leisure Score Index |

| EORTC | European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer |

| QLQ-C30 | Core Quality of Life Questionnaire |

| VU-34 | Vulva-specific Module of Core Quality of Life Questionnaire |

| IQR | Inter Quartile Range |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| VIN | Vulvar Intraepithelial Neoplasia |

| NOS | Not Otherwise Specified |

References

- Cancer Today. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/online-analysis-multi-bars?v=2018&mode=cancer&mode_population=countries&population=900&populations=900&key=total&sex=0&cancer=39&type=0&statistic=5&prevalence=0&population_group=0&ages_group%5B%5D=0&ages_group%5B%5D=14&nb_items=10&group_cancer=1&include_nmsc=1&include_nmsc_other=1&type_multiple=%257B%2522inc%2522%253Atrue%252C%2522mort%2522%253Afalse%252C%2522prev%2522%253Afalse%257D&orientation=horizontal&type_sort=0&type_nb_items=%257B%2522top%2522%253Atrue%252C%2522bottom%2522%253Afalse%257D&population_group_globocan_id= (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Capria, A.; Tahir, N.; Fatehi, M. Vulva Cancer; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vulvar Cancer: Epidemiology, Diagnosis, Histopathology, and Treatment—UpToDate. Available online: https://www-uptodate-com.ru.idm.oclc.org/contents/vulvar-cancer-epidemiology-diagnosis-histopathology-and-treatment?search=vulvar cancer etiology&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~90&usage_type=default&display_rank=1 (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Thuijs, N.B.; van Beurden, M.; Bruggink, A.H.; Steenbergen, R.D.; Berkhof, J.; Bleeker, M.C. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: Incidence and long-term risk of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 148, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oonk, M.H.M.; Planchamp, F.; Baldwin, P.; Mahner, S.; Mirza, M.R.; Fischerová, D.; Creutzberg, C.L.; Guillot, E.; Garganese, G.; Lax, S.; et al. European Society of Gynaecological Oncology Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Vulvar Cancer—Update 2023. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2023, 33, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaarenstroom, K.N.; Kenter, G.G.; Trimbos, J.B.; Agous, I.; Amant, F.; Peters, A.A.W.; Vergote, I. Postoperative complications after vulvectomy and inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy using separate groin incisions. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2003, 13, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pouwer, A.F.W.; Arts, H.J.; van der Velden, J.; de Hullu, J.A. Limiting the morbidity of inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy in vulvar cancer patients; a review. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2017, 17, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oonk, M.H.; van Hemel, B.M.; Hollema, H.; de Hullu, J.A.; Ansink, A.C.; Vergote, I.; Verheijen, R.H.; Maggioni, A.; Gaarenstroom, K.N.; Baldwin, P.J.; et al. Size of sentinel-node metastasis and chances of non-sentinel-node involvement and survival in early stage vulvar cancer: Results from GROINSS-V, a multicentre observational study. Lancet. Oncol. 2010, 11, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senn, B.; Gafner, D.; Happ, M.B.; Eicher, M.; Mueller, M.D.; Engberg, S.; Spirig, R. The unspoken disease: Symptom experience in women with vulval neoplasia and surgical treatment: A qualitative study. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2011, 20, 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimena, S.; Sullivan, M.W.; Philp, L.; Dorney, K.; Hubbell, H.; del Carmen, M.G.; Goodman, A.; Bregar, A.; Growdon, W.B.; Eisenhauer, E.L.; et al. Patient reported outcome measures among patients with vulvar cancer at various stages of treatment, recurrence, and survivorship. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021, 160, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Y.C.; Lu, C.H.; Chen, I.H.; Kuo, S.F.; Huang, Y.P. Quality of life and its predictors among women with gynaecological cancers. Collegian 2021, 28, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, A.; Lopes, A.; Das, N.; Bekkers, R.; Galaal, K. The impact of BMI on quality of life in obese endometrial cancer survivors: Does size matter? Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 132, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffey, K.; Gaitskell, K.; Beral, V.; Canfell, K.; Green, J.; Reeves, G.; Barnes, I. Past cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3, obesity, and earlier menopause are associated with an increased risk of vulval cancer in postmenopausal women. Br. J. Cancer 2016, 115, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapdor, R.; Hillemanns, P.; Wölber, L.; Jückstock, J.; Hilpert, F.; De Gregorio, N.; Hasenburg, A.; Sehouli, J.; Fürst, S.; Strauss, H.; et al. Association between obesity and vulvar cancer recurrence: An analysis of the AGO-CaRE-1 study. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2020, 30, 920–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beesley, V.L.; Eakin, E.G.; Janda, M.; Battistutta, D. Gynecological cancer survivors’ health behaviors and their associations with quality of life. Cancer Causes Control 2008, 19, 775–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olawaiye, A.B.; Cotler, J.; Cuello, M.A.; Bhatla, N.; Okamoto, A.; Wilailak, S.; Purandare, C.N.; Lindeque, G.; Berek, J.S.; Kehoe, S.; et al. FIGO staging for carcinoma of the vulva: 2021 revision. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2021, 155, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weir, C.B.; Jan, A. BMI Classification Percentile and Cut Off Points; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Godin, G. The Godin-Shephard Leisure-Time Physical Activity Questionnaire. Health Fit. J. Can. 2024, 4, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- EORTC QLQ-C30|EORTC—Quality of Life. Available online: https://qol.eortc.org/questionnaires/core/eortc-qlq-c30/ (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0.2.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2023.

- EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual the EORTC QLQ-C30. 2001. Available online: https://www.eortc.org/app/uploads/sites/2/2018/02/SCmanual.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Smits, A.; Smits, E.; Lopes, A.; Das, N.; Hughes, G.; Talaat, A.; Pollard, A.; Bouwman, F.; Massuger, L.; Bekkers, R.; et al. Body mass index, physical activity and quality of life of ovarian cancer survivors: Time to get moving? Gynecol. Oncol. 2015, 139, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babatunde, O.A.; Adams, S.A.; Orekoya, O.; Basen-Engquist, K.; Steck, S.E. Effect of Physical Activity on Quality of Life as Perceived by Endometrial Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2016, 26, 1727–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, S.; Jones, T.; Janda, M.; Vagenas, D.; Ward, L.; Reul-Hirche, H.; Sandler, C.; Obermair, A.; Hayes, S. Physical activity trajectories following gynecological cancer: Results from a prospective, longitudinal cohort study. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2020, 30, 1784–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainordin, N.H.; Karim, N.A.; Shahril, M.R.; Talib, R.A. Physical Activity, Sitting Time, and Quality of Life Among Breast and Gynaecology Cancer Survivors. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2021, 22, 2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevinson, C.; Faught, W.; Steed, H.; Tonkin, K.; Ladha, A.B.; Vallance, J.K.; Capstick, V.; Schepansky, A.; Courneya, K.S. Associations between physical activity and quality of life in ovarian cancer survivors. Gynecol. Oncol. 2007, 106, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; McLaughlin, E.M.; Krok-Schoen, J.L.; Naughton, M.; Bernardo, B.M.; Cheville, A.; Allison, M.; Stefanick, M.; Bea, J.W.; Paskett, E.D. Association of Lower Extremity Lymphedema with Physical Functioning and Activities of Daily Living Among Older Survivors of Colorectal, Endometrial, and Ovarian Cancer. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e221671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Singh, B.; Reul-Hirche, H.; Bloomquist, K.; Johansson, K.; Jönsson, C.; Plinsinga, M.L. The Effect of Exercise for the Prevention and Treatment of Cancer-Related Lymphedema: A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2022, 54, 1389–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jónsdóttir, B.; Wikman, A.; Poromaa, I.S.; Stålberg, K. Advanced gynecological cancer: Quality of life one year after diagnosis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smits, A.; Lopes, A.; Bekkers, R.; Galaal, K. Body mass index and the quality of life of endometrial cancer survivors—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol. Oncol. 2015, 137, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donkers, H.; Smits, A.; Eleuteri, A.; Bekkers, R.; Massuger, L.; Galaal, K. Body mass index and sexual function in women with gynaecological cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2019, 28, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirik, D.A.; Karalok, A.; Ureyen, I.; Tasci, T.; Kalyoncu, R.; Turkmen, O.; Kose, M.F.; Tulunay, G.; Turan, T. Early and late complications after inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy for vulvar cancer. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2015, 16, 5175–5179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigott, A.; Obermair, A.; Janda, M.; Vagenas, D.; Ward, L.C.; Reul-Hirche, H.; Hayes, S.C. Incidence and risk factors for lower limb lymphedema associated with endometrial cancer: Results from a prospective, longitudinal cohort study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 158, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebegea, L.; Stoleriu, G.; Manolache, N.; Serban, C.; Craescu, M.; Lupu, M.-N.; Voinescu, D.; Firescu, D.; Ciobotaru, O. Associated risk factors of lower limb lymphedema after treatment of cervical and endometrial cancer. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Berg, N.J.; van Beurden, F.P.; Wendel-Vos, G.C.W.; Duijvestijn, M.; van Beekhuizen, H.J.; Maliepaard, M.; van Doorn, H.C. Patient-Reported Mobility, Physical Activity, and Bicycle Use After Vulvar Carcinoma Surgery. Cancers 2023, 15, 2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.Y.; Edbrooke, L.; Granger, C.L.; Denehy, L.; Frawley, H.C. The impact of gynaecological cancer treatment on physical activity levels: A systematic review of observational studies. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2019, 23, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Activity Levels See Partial Recovery from COVID-19|Sport England. Available online: https://www.sportengland.org/news/activity-levels-see-partial-recovery-covid-19 (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Chatterjee, R.; Chapman, T.; Brannan, M.G.T.; Varney, J. GPs’ knowledge, use, and confidence in national physical activity and health guidelines and tools: A questionnaire-based survey of general practice in England. Br. J. Gen. Pract. J. R. Coll. Gen. Pract. 2017, 67, e668–e675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, V.; Malchow, B.; Schubert, M.; Andresen, L.; Jochens, A.; Jonat, W.; Mundhenke, C.; Alkatout, I. Impact of radical operative treatment on the quality of life in women with vulvar cancer—A retrospective study. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2014, 40, 875–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trott, S.; Höckel, M.; Dornhöfer, N.; Geue, K.; Aktas, B.; Wolf, B. Quality of life and associated factors after surgical treatment of vulvar cancer by vulvar field resection (VFR). Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 302, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orsini, N.; Bellocco, R.; Bottai, M.; Hagströmer, M.; Sjöström, M.; Pagano, M.; Wolk, A. Validity of self-reported total physical activity questionnaire among older women. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2008, 23, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogonowska-Slodownik, A.; Morgulec-Adamowicz, N.; Geigle, P.R.; Kalbarczyk, M.; Kosmol, A. Objective and Self-Reported Assessment of Physical Activity of Women over 60 Years Old. Ageing Int. 2022, 47, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, E.; Oldham, M. Weight status misperceptions among UK adults: The use of self-reported vs. measured BMI. BMC Obes. 2016, 3, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nout, R.A.; Van De Poll-Franse, L.V.; Lybeert, M.L.M.; Wárlám-Rodenhuis, C.C.; Jobsen, J.J.; Mens, J.W.M.; Lutgens, L.C.H.W.; Pras, B.; Van Putten, W.L.J.; Creutzberg, C.L. Long-term outcome and quality of life of patients with endometrial carcinoma treated with or without pelvic radiotherapy in the post operative radiation therapy in endometrial carcinoma 1 (PORTEC-1) trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 1692–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, E.; Boulton, M.G.; Horne, A.; Rose, P.W.; Durrant, L.; Collingwood, M.; Oskrochi, R.; Davidson, S.E.; Watson, E.K. The effects of pelvic radiotherapy on cancer survivors: Symptom profile, psychological morbidity and quality of life. Clin. Oncol. R. Coll. Radiol. 2014, 26, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Clinical Characteristics | Respondents n = 58 (%/SD/IQR) | Non-Respondents n = 81 (%/SD/IQR) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years (mean, SD) | 68 (10.7) | 60 (13.6) | <0.001 |

| BMI in kg/m2 at time of diagnosis (median, IQR) | 28.5 (24.4–32.9) | 29.0 (24.0–24.0) | n.s. |

| Missing value | 8 | 18 | |

| BMI categories | n.s. | ||

| <18.5 kg/m2 | 2 (3.4%) | 1 (1.2%) | |

| 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 | 11 (19.0%) | 19 (23.5%) | |

| 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 | 15 (25.9%) | 15 (18.5%) | |

| ≥30 kg/m2 | 24 (41.4%) | 28 (34.6%) | |

| Missing value | 6 (10.3%) | 18 (22.2%) | |

| Primary vulvar surgery | n.s. | ||

| Wide local excision | 31 (53.4%) | 33 (40.7%) | |

| Vulvectomy | 23 (39.7%) | 43 (53.1%) | |

| Anovulvectomy | 3 (5.2%) | 4 (4.9%) | |

| Vulvovaginectomy | 1 (1.7%) | 1 (1.2%) | |

| Lymphadenectomy | n.s. | ||

| Inguinofemoral nodes | 44 (75.9%) | 57 (70.4%) | |

| Sentinel nodes | 8 (13.8%) | 21 (25.9%) | |

| None | 6 (10.3%) | 3 (3.7%) | |

| Tumor origin | n.s. | ||

| HPV | 19 (32.8%) | 27 (33.3%) | |

| Lichen sclerosis | 29 (50.0%) | 40 (49.4%) | |

| VIN NOS | 7 (12.1%) | 10 (12.3%) | |

| Bartholin’s gland | 1 (1.7%) | 1 (1.2%) | |

| Unknown | 2 (3.4%) | 3 (3.7%) | |

| FIGO stage | n.s. | ||

| IB | 43 (74.1%) | 67 (82.7%) | |

| II | 3 (5.2%) | 1 (1.2%) | |

| III | 12 (20.7%) | 13 (16.3%) | |

| Time since operation in months | 64.6 (31.0–95.0) | 70.1 (34.0–96.0) | n.s. |

| Recurrence | n.s. | ||

| Yes | 12 (20.7%) | 10 (12.3%) | |

| No | 46 (79.3%) | 71 (87.7%) | |

| Smoking at time of diagnosis | n.s. | ||

| Yes | 9 (15.5%) | 20 (24.7%) | |

| No | 38 (65.5%) | 41 (50.6%) | |

| Unknown | 11 (19.0%) | 20 (24.7%) | |

| ASA score | n.s. | ||

| I | 3 (5.2%) | 3 (3.7%) | |

| II | 24 (41.4%) | 36 (44.4%) | |

| III | 9 (15.5%) | 10 (12.3%) | |

| IV | 1 (1.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Unknown | 21 (36.2%) | 32 (39.5%) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Cardiovascular disease | 17 (30.4%) | 32 (38.6%) | n.s. |

| Diabetes mellitus | 10 (17.2%) | 13 (16.0%) | n.s. |

| Respiratory disease | 13 (22.4%) | 14 (17.2%) | n.s. |

| Mental health issues | 7 (12.1%) | 10 (12.3%) | n.s. |

| Rheumatic/musculoskeletal diseases | 10 (17.2%) | 13 (16.0%) | n.s. |

| Quality Of Life Outcomes | Total Population n = 58 (IQR) | Non-Obese n = 32 (IQR) | Obese n = 17 (IQR) | p-Value Univariate Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global health score | 66.7 (50.0–83.3) | 62.5 (50.0–83.3) | 66.7 (66.7–83.3) | n.s. |

| Functional scales | ||||

| Physical functioning | 74.2 (46.7–93.3) | 81.7 (53.3–96.65) | 80.0 (60.0–93.3) | n.s. |

| Role functioning | 83.3 (50.0–100) | 66.7 (50.0–100) | 83.3 (66.7–100) | n.s. |

| Emotional functioning | 83.3 (66.7–100) | 83.3 (66.7–100) | 83.3 (58.3–100) | n.s. |

| Cognitive functioning | 83.3 (66.7–100) | 83.3 (66.7–100) | 83.3 (66.7–100) | n.s. |

| Social functioning | 83.3 (50.0–100) | 91.7 (58.3–100) | 100 (66.7–100) | n.s. |

| Symptom scales | ||||

| Fatigue | 33.3 (11.1–55.5) | 33.3 (11.1–55.5) | 33.3 (11.1–44.4) | n.s. |

| Nausea and vomiting | 0 (0–16.6) | 0 (0–16.7) | 0 (0–0) | n.s. |

| Pain | 0 (0–33.3) | 0 (0–33.3) | 0 (0–33.3) | n.s |

| Dyspnea | 0 (0–33.3) | 0 (0–33.3) | 0 (0–33.3) | n.s. |

| Insomnia | 33.3 (0–33.3) | 33.3 (0–33.3) | 0 (0–33.3) | n.s. |

| Appetite loss | 0 (0–33.3) | 0 (0–33.3) | 0 (0–16.7) | n.s. |

| Constipation | 0 (0–33.3) | 0 (0–33.3) | 16.7 (0–33.3) | n.s. |

| Diarrhea | 0 (0–33.3) | 0 (0–33.3) | 0 (0–0) | n.s. |

| Financial difficulties | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | n.s. |

| VU-34 functional scales | ||||

| Body image | 66.7 (44.0–100) | 77.8 (56.0–100) | 44.0 (22.2–66.7) | 0.043 * |

| Sexual enjoyment | 58.3 (50–83.3) | 50.0 (33.3–83.3) | 66.7 (66.7–100) | n.s. |

| Sexually related vaginal changes | 66.7 (33.3–88.8) | 72.2 (66.7–100) | 33.3 (0–66.7) | n.s. |

| VU-34 symptom scales | ||||

| Vulva skin changes | 13.3 (0–20.0) | 13.3 (0–20.0) | 13.3 (6.7–40.0) | n.s. |

| Vulva scarring | 16.7 (0–33.3) | 16.7 (0–33.3) | 16.7 (0–33.3) | n.s. |

| Vulvo-vaginal discharge | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | n.s. |

| Vulva swelling | 0 (0–16.7) | 0 (0–16.7) | 0 (0–33.3) | n.s. |

| Groin lymphoedema | 11.1 (0–22.2) | 0 (0–11.1) | 11.1 (0–33.3) | n.s. |

| Leg lymphoedema | 20.8 (0–50.0) | 8.3 (0–29.2) | 50.0 (16.7–75.0) | 0.006 * |

| Urine urgency and leakage | 25 (8.3–50.0) | 33.3 (8.3–50.0) | 16.7 (8.3–41.6) | n.s. |

| Bowel urgency and leakage | 16.7 (0–33.3) | 16.7 (0–33.3) | 0 (0–16.7) | n.s. |

| Non-Obese n = 32 | Obese n = 17 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sedentary lifestyle | 13 (40.6%) | 7 (41.2%) | n.s. |

| Moderately active lifestyle | 6 (18.8%) | 2 (11.8%) | |

| Active lifestyle | 12 (37.5%) | 5 (29.4%) | |

| Not disclosed | 1 (3.1%) | 3 (17.6%) |

| Sedentary n = 25 (IQR) | Moderately Active n = 8 (IQR) | Active n = 18 (IQR) | Univariate p-Value | Multivariate p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global health score | 50.0 (41.6–66.7) | 75.0 (54.1–83.3) | 83.3 (66.7–91.6) | <0.001 * | 0.004 * |

| Functional scales | |||||

| Physical functioning | 60.0 (46.7–73.3) | 81.7 (46.7–91.1) | 100 (86.7–100) | <0.001 * | <0.001 * |

| Role functioning | 50.0 (33.3–75.0) | 83.3 (33.3–100) | 100 (100–100) | <0.001 * | <0.001 * |

| Emotional functioning | 66.7 (50.0–83.3) | 70.8 (41.6–91.6) | 100 (88.8–100) | <0.001 * | <0.001 * |

| Cognitive functioning | 83.3 (50.0–83.3) | 91.6 (83.3–100) | 100 (83.3–100) | <0.001 * | <0.001 * |

| Social functioning | 66.7 (33.3–83.3) | 83.3 (66.7–100) | 100 (100–100) | 0.001 * | 0.003 * |

| Symptom scales | |||||

| Fatigue | 33.3 (33.3–66.6) | 22.2 (0–55.5) | 11.1 (0–22.2) | <0.001 * | 0.005 * |

| Nausea and vomiting | 0 (0–16.6) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0.010 * | n.s. |

| Pain | 0 (0–50.0) | 24.6 (0–33.3) | 0 (0–16.6) | n.s. | |

| Dyspnea | 0 (0–33.3) | 0 (0–33.3) | 0 (0–0) | n.s. | |

| Insomnia | 33.3 (0–33.3) | 33.3 (16.6–50.0) | 0 (0–33.3) | 0.017 * | n.s. |

| Appetite loss | 33.3 (0–33.3) | 0 (0–33.3) | 0 (0–0) | 0.002 * | 0.026 * |

| Constipation | 0 (0–33.3) | 16.7 (0–50.0) | 0 (0–0) | n.s. | |

| Diarrhea | 0 (0–33.3) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | n.s. | |

| Financial difficulties | 0 (0–33.3) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | n.s. | |

| VU-34 functional scales | |||||

| Body image | 66.7 (33.3–88.9) | 56 (39.2–100) | 77.8 (56–100) | n.s. | |

| Sexual enjoyment | 83.3 (33.3–100) | 50.0 (50.0–50.0) | 58.3 (50.0–66.7) | n.s. | |

| Sexually related vaginal changes | 77.7 (0–100) | 66.7 (66.7–66.7) | 66.7 (33.3–83.3) | n.s. | |

| VU-34 symptom scales | |||||

| Vulva skin changes | 13.3 (6.7–40.0) | 13.3 (0–26.7) | 10 (0–20.0) | n.s. | |

| Vulva scarring | 16.7 (0–50.0) | 33.3 (0–33.3) | 16.7 (0–33.3) | n.s. | |

| Vulvo-vaginal discharge | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | n.s. | |

| Vulva swelling | 16.7 (0–33.3) | 0 (0–0) | 8.3 (0–33.3) | 0.047 * | n.s. |

| Groin lymphoedema | 11.1 (0–22.2) | 0 (0–22.2) | 5.5 (0–1.1) | n.s. | |

| Leg lymphoedema | 25.0 (8.3–66.7) | 25 (12.5–58.3) | 12.5 (0–33.3) | n.s. | |

| Urine urgency and leakage | 33.3 (20.8–45.8) | 20.8 (0–50.0) | 8.3 (0–50.0) | n.s. | |

| Bowel urgency and leakage | 16.7 (0–33.3) | 25.0 (0–50.0) | 0 (0–16.7) | n.s. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boonstra, M.S.; Smits, A.; Cassar, V.; Bekkers, R.L.M.; Anderson, Y.; Ratnavelu, N.; Vergeldt, T.F.M. The Effect of Lifestyle on the Quality of Life of Vulvar Cancer Survivors. Cancers 2025, 17, 1024. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17061024

Boonstra MS, Smits A, Cassar V, Bekkers RLM, Anderson Y, Ratnavelu N, Vergeldt TFM. The Effect of Lifestyle on the Quality of Life of Vulvar Cancer Survivors. Cancers. 2025; 17(6):1024. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17061024

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoonstra, Marleen S., Anke Smits, Viktor Cassar, Ruud L. M. Bekkers, Yvonne Anderson, Nithya Ratnavelu, and Tineke F. M. Vergeldt. 2025. "The Effect of Lifestyle on the Quality of Life of Vulvar Cancer Survivors" Cancers 17, no. 6: 1024. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17061024

APA StyleBoonstra, M. S., Smits, A., Cassar, V., Bekkers, R. L. M., Anderson, Y., Ratnavelu, N., & Vergeldt, T. F. M. (2025). The Effect of Lifestyle on the Quality of Life of Vulvar Cancer Survivors. Cancers, 17(6), 1024. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17061024