Simple Summary

While cancer is a leading cause of death in people with HIV, less is known about clinical outcomes after cancer. We aimed to assess outcomes after the five most common cancers in people with HIV (Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS); non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL); and lung, anal and prostate cancers) in two international HIV cohort collaborations (D:A:D and RESPOND). We assessed incidence rates and risk factors of mortality, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, another primary cancer and AIDS events individually and as a non-fatal composite clinical outcome (CCO). Amongst 2485 participants, those with lung cancer had the highest rates of mortality, CCO and diabetes, whilst those with KS had the lowest rates of mortality, CCO, diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Higher CD4 count consistently protected against post-cancer mortality and CCO. Modifiable lifestyle factors (smoking, low BMI and high comorbidity burden) increased the risk of CCO after NHL and KS. These results highlight the importance of personalized post-cancer clinical monitoring.

Abstract

Background/Objectives: Whilst cancer is a leading cause of death in people with HIV, less is known about clinical outcomes after cancer. Methods: Participants from the RESPOND and D:A:D cohorts with the five most common cancers (Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS); non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL); and lung, anal and prostate cancers) were followed from first cancer diagnosis after 2006/2012 [D:A:D/RESPOND] until death, final follow-up or administrative censoring (2016/2021). Incidence rates (IR) were calculated for post-cancer mortality; for non-fatal events (cardiovascular disease, diabetes, another primary cancer, AIDS events) individually and as a non-fatal composite clinical outcome (CCO). Predictors or mortality and CCO were assessed using Poisson regression with generalized estimating equations. Results: Amongst 2485 participants with cancer, mortality and CCO IRs were highest after lung cancer (445.4/1000 person years [95% CI 399.7, 494.9], 117.1 [94.3, 143.8], respectively) compared to other cancers and lowest after KS (21.3 [16.9, 26.6], 43.9 [37.5, 51.3]). The most common non-fatal outcomes were AIDS events after NHL and KS, diabetes after lung and prostate cancer and another primary cancer after anal cancer. Among people with NHL and anal cancer, a diagnosis in more recent years was associated with lower mortality risk. Increasing the time-updated CD4 count reduced mortality by 15–40% (per 100 cells/µL) after NHL and anal and lung cancers and reduced CCO risk by 17–28% after KS and NHL. Smoking, low BMI and multimorbidity increased CCO risks by two to three times after KS and NHL. Conclusions: Risk of post-cancer mortality and non-fatal outcomes varies by cancer type and risk profile, suggesting the need for personalized post-cancer clinical monitoring.

1. Introduction

People with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) have a higher incidence of several cancers, including lung and anal cancers, as well as lymphomas [1,2]. This increased incidence is multifactorial and related to immunosuppression, higher coinfection rates with pro-oncogenic viruses and lifestyle factors such as smoking [3,4]. With widespread access to antiretroviral therapy (ART), there has been a large decline in the incidence of several cancers, including those previously termed Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS)-defining cancers (Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and cervical cancer) and other infection-related cancers [5,6]. However, the incidence of other cancer types (e.g., smoking- and obesity-related cancers) has slightly increased [5].

Cancer has become a leading cause of death among people with HIV in high- and middle-income countries [6,7,8]. Additionally, some studies suggest that people with HIV and poor immune function, in particular, have higher mortality risk after cancer compared to the general population [9,10]. Beyond mortality, studies in the general population suggest that people with prior lung, breast and colorectal cancers are at increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) compared to those without cancer, while data is more conflicting for other cancers, such as prostate cancer [11,12,13]. Similarly, other data from the general population suggest that people with cancer have increased risk of diabetes, often secondary to the cancer treatment [14,15,16,17]. Additionally, use of chemotherapy, corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive therapies may detrimentally lower immune function and increase the risk of opportunistic infections, prompting recommendations of prophylaxis in HIV [18,19,20].

Assessments of cancer-related outcomes in people with HIV are limited to date. However, a recent US cohort study did find that the risk of severe events, such as diabetes and myocardial infarction, was increased among those with HIV and certain cancers compared to those with HIV but without cancer [21]. However, the investigators did not assess the impact of HIV-associated factors and focused exclusively on what were historically classified as non-AIDS-defining cancers. Insights into incidence rates (IRs) and predictors of mortality and non-fatal clinical outcomes after cancer in people with HIV are crucial for the optimization of clinical monitoring and personalized post-cancer care.

Using combined data from two large international observational cohorts of well-characterized people with HIV, we aimed to assess the IRs and risk factors for mortality, CVD, diabetes, another primary cancer and AIDS events following diagnosis of the most common individual cancers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The Data Collection on Adverse events of Anti-HIV Drugs (D:A:D) and International Cohort Consortium of Infectious Diseases (RESPOND) cohorts are prospective multi-cohort collaborations of people with HIV from across Europe, Australia and the US. D:A:D (1999–2016) includes data from approximately 49,000 people with HIV across 11 cohorts, while RESPOND (2017–present) includes data from approximately 35,000 people from 17 cohorts, with some overlap in cohorts and participants. Detailed information on both studies is published elsewhere [22,23]. The studies use a similar methodology, collecting standardized data during routine clinical care. Systematic cancer collection began in 2006 in D:A:D and in 2017 in RESPOND, with retrospective cancer events collected back to 2012 in RESPOND and earlier if available. In addition to annual collection of demographic and clinical data, specific serious clinical events (including death, cancer and CVD) are collected in real time using study-specific case report forms and centrally validated against pre-defined algorithms by trained physicians [24,25,26]. A selection of all cancer events is subsequently reviewed by an external oncologist.

2.2. Study Population

We included all participants from D:A:D and RESPOND aged 18 years or older at study entry and diagnosed after cohort enrolment with one of the five most common cancers in the cohorts, excluding precancerous lesions, non-melanoma skin cancers and relapses or metastases from previous cancers. To ensure a sufficient number of clinical outcomes after each cancer, we focused on the most common cancers: NHL; KS; and lung, anal and prostate cancers.

Participants were excluded from RESPOND if they lacked CD4 count or viral load (VL) measurements within one year before or 12 weeks after baseline, as defined below, as in prior RESPOND analyses [5]. These criteria were not used in the D:A:D study and, therefore, were not applied to D:A:D participants in our primary analysis but were considered in a sensitivity analysis. Participants were excluded from RESPOND and D:A:D if they lacked gender/sex data. Individual RESPOND cohorts with potential under-reporting of cancer and other clinical outcomes were excluded. Participants enrolled in both cohorts were counted only once, as in prior combined analyses [5].

Baseline was defined as the date of first diagnosis of one of the five most common cancers after the latest of cohort enrolment and 2006/2012 (D:A:D/RESPOND).

Participants were followed from the time of incident cancer until the earliest of death, final follow-up (D:A:D: date of last visit plus 6 months; RESPOND: the latest of the most recent CD4 count, VL measurement, ART start date, drop-out date or date of death) or the administrative censoring date (D:A:D: 1 February 2016; RESPOND: 31 December 2021). Participants enrolled in both D:A:D and RESPOND were followed until the final RESPOND follow-up.

2.3. Outcome Definitions

The main outcomes of interest following cancer diagnosis were severe clinical events systematically captured in both consortiums and included death (using the coding of death in HIV (CoDe) methodology [26]), non-fatal CVD, diabetes, another primary cancer and a new AIDS-defining event. Additionally, these four non-fatal outcomes were combined into a non-fatal composite clinical outcome (non-fatal CCO), as low event rates did not allow for an adequate assessment of the risk factors for each outcome separately. CVD was defined as a composite of myocardial infarction, stroke and invasive cardiovascular procedures (coronary angioplasty or stenting, coronary bypass surgery and carotid endarterectomy). Diabetes was defined as two confirmed random blood glucose levels ≥ 11.1 mmol/L, a single HbA1c ≥ 6.5%, use of antidiabetic medication or a cohort-reported clinical diagnosis [25]. Another primary cancer was defined as a new distinct cancer of a type other than the baseline cancer, excluding non-melanoma skin cancers, precancerous lesions, relapses and metastases from previously diagnosed cancers. AIDS events were based on the criteria established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [27].

2.4. Potential Risk Factors

The following variables were considered as potential risk factors for mortality and clinical outcomes: calendar year, age, gender/sex, HIV acquisition mode, ethnicity/race, geographical region, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, CD4 count, VL, ART experience, cancer stage at time of diagnosis, comorbidities (including CVD, chronic kidney disease (CKD), AIDS, diabetes, other cancers, hypertension and dyslipidemia) and comorbidity burden. Definitions of all variables are provided in the Table 1 footnotes.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Crude IRs and 95% confidence intervals ( CIs) for mortality, CVD, diabetes, another primary cancer, AIDS events and non-fatal CCO were calculated per 1000 person years of follow-up (PYFU) after cancer diagnosis. We also examined individual causes of death after cancer.

Poisson regression models with generalized estimating equations and robust standard errors were used to investigate associations between risk factors for mortality and non-fatal CCO after each cancer. Log follow-up time was included as an offset. Each potential risk factor was initially assessed in univariable models. Age, gender/sex, ART status, calendar year, BMI and smoking status were included in the multivariable models a priori. Other factors were included only if they achieved p < 0.1 in univariable analysis. Cancer stage was assessed as a risk factor only for lung, anal and prostate cancers, as it was not systematically collected in D:A:D for NHL and KS.

The mortality regression models were adjusted for prior and time-updated comorbidities, including CVD, CKD, AIDS, diabetes, other cancers, hypertension and dyslipidemia. However, due to limited statistical power, in the non-fatal CCO models, we combined these comorbidities into a comorbidity burden variable.

Data on the type of cancer treatment were not systematically available in D:A:D and were therefore not included in the analysis.

Missing data for categorical variables were accounted for by including an unknown category in all regression models.

2.6. Sensitivity Analyses

Several sensitivity analyses were conducted: (1) using a Fine–Gray model to treat death as a competing risk for CCO, (2) assessment of risk factors for non-fatal CCO with AIDS events excluded from the definition, (3) including only centrally validated clinical events, (4) excluding participants with missing data for any variables included in the multivariable model, (5) excluding participants with prior serious clinical events (CVD, AIDS, diabetes or cancer) and (6) applying RESPOND exclusion criteria to D:A:D participants.

Analyses were performed using Stata/SE 18.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

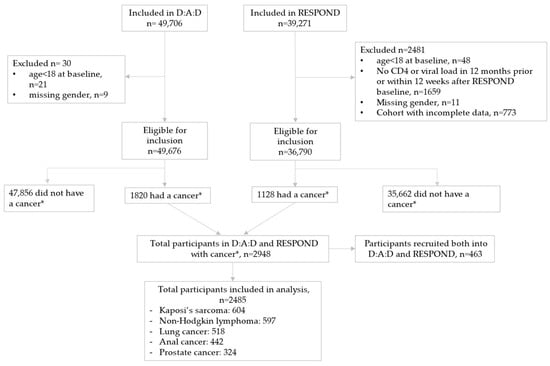

We included 1820 D:A:D and 1128 RESPOND participants with one of the five cancers. Of those, 463 participants were enrolled in both cohorts and only included once, resulting in 2485 unique participants (Figure 1). There were 604 (24%) participants with KS, 597 (24%) with NHL, 518 (21%) with lung cancer, 442 (18%) with anal cancer and 324 (13%) with prostate cancer.

Figure 1.

Study flow. * The five most common cancers in the combined D:A:D and RESPOND database: Kaposi’s sarcoma; non-Hodgkin lymphoma; and lung, anal and prostate cancers.

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

Baseline characteristics (at cancer diagnosis) are presented in Table 1: 88% of participants were male, 56% were white, 14% were ART-naïve and 64% were virally suppressed. Median age was highest in those with prostate (64 years, interquartile range [IQR, 59–69]) and lung cancers (57 [51–63]) and lowest in those with KS (43 [36–51]). Whilst the majority of participants with lung cancer had disseminated disease at the time of diagnosis (58%), this was substantially less frequent for anal and prostate cancers (both 15%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics (at cancer diagnosis) of participants overall and by cancer type.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics (at cancer diagnosis) of participants overall and by cancer type.

| Overall (n = 2485) | Kaposi’s Sarcoma (n = 604) | Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (n = 597) | Lung Cancer (n = 518) | Anal Cancer (n = 442) | Prostate Cancer (n = 324) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | % | p | |

| Age, years | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| <40 | 430 | (17.3) | 242 | (40.1) | 142 | (23.7) | 9 | (1.7) | 38 | (8.6) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| 40–49 | 674 | (27.1) | 189 | (31.2) | 208 | (34.7) | 111 | (21.4) | 157 | (35.5) | 10 | (3.1) | |

| 50+ | 1381 | (55.6) | 173 | (28.7) | 247 | (41.6) | 398 | (76.8) | 247 | (55.9) | 314 | (96.6) | |

| Sex/Gender a | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Male | 2190 | (88.1) | 559 | (92.5) | 503 | (84.3) | 414 | (79.9) | 390 | (88.2) | 324 | (100.0) | |

| Female | 294 | (11.8) | 44 | (7.3) | 94 | (15.7) | 104 | (20.1) | 52 | (11.8) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Transgender | 1 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.2) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Ethnicity/Race b | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| White | 1380 | (55.5) | 249 | (41.0) | 318 | (53.4) | 321 | (62.0) | 278 | (62.9) | 214 | (66.6) | |

| Black | 101 | (4.1) | 31 | (5.1) | 43 | (7.2) | 5 | (1.0) | 9 | (2.0) | 13 | (4.0) | |

| Other | 45 | (1.8) | 13 | (2.2) | 15 | (2.5) | 7 | (1.4) | 7 | (1.6) | 3 | (0.9) | |

| Unknown | 959 | (38.6) | 311 | (51.7) | 221 | (36.9) | 185 | (35.7) | 148 | (33.5) | 94 | (29.9) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| <18.5 | 156 | (6.3) | 33 | (5.5) | 33 | (5.5) | 53 | (10.2) | 29 | (6.6) | 8 | (2.5) | |

| 18.5–<25 | 1427 | (57.4) | 367 | (60.6) | 308 | (51.8) | 306 | (59.1) | 275 | (62.2) | 171 | (52.8) | |

| >25 | 608 | (24.5) | 107 | (17.8) | 161 | (26.9) | 114 | (22.0) | 106 | (24.0) | 120 | (37.0) | |

| Unknown | 294 | (11.8) | 97 | (16.1) | 95 | (15.9) | 45 | (8.7) | 32 | (7.2) | 25 | (7.7) | |

| Geographical Region | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Western Europe | 1010 | (40.6) | 192 | (31.6) | 237 | (39.9) | 245 | (47.3) | 178 | (40.3) | 158 | (48.8) | |

| Southern Europe | 418 | (16.8) | 99 | (16.4) | 110 | (18.4) | 92 | (17.8) | 73 | (16.5) | 44 | (13.6) | |

| Northern Europe | 967 | (38.9) | 304 | (50.5) | 217 | (36.2) | 159 | (30.7) | 176 | (39.8) | 111 | (34.3) | |

| Eastern Europe | 79 | (3.2) | 9 | (1.5) | 24 | (4.0) | 20 | (3.9) | 15 | (3.4) | 11 | (3.4) | |

| USA | 10 | (0.4) | 0 | (0.0) | 9 | (1.5) | 1 | (0.2) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| HIV acquisition mode | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| MSM | 1454 | (58.5) | 449 | (74.3) | 284 | (47.7) | 213 | (41.1) | 306 | (69.2) | 202 | (62.3) | |

| IDU | 271 | (10.9) | 11 | (1.8) | 79 | (13.2) | 124 | (23.9) | 45 | (10.2) | 12 | (3.7) | |

| Heterosexual | 597 | (24.0) | 109 | (18.1) | 178 | (29.7) | 152 | (29.3) | 67 | (15.2) | 91 | (28.1) | |

| Other | 50 | (2.0) | 6 | (1.0) | 16 | (2.7) | 12 | (2.3) | 7 | (1.6) | 9 | (2.8) | |

| Unknown | 113 | (4.5) | 29 | (4.8) | 40 | (6.7) | 17 | (3.3) | 17 | (3.8) | 10 | (3.1) | |

| ARV treatment history | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Naive | 344 | (13.8) | 208 | (34.4) | 95 | (15.9) | 18 | (3.5) | 13 | (2.9) | 11 | (3.4) | |

| ART-experienced | 2126 | (85.6) | 393 | (65.1) | 500 | (83.8) | 493 | (95.2) | 427 | (96.6) | 312 | (96.3) | |

| CD4 nadir c, cells/µL | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| <200 | 1528 | (61.5) | 349 | (57.8) | 377 | (63.3) | 316 | (61.0) | 311 | (70.4) | 174 | (53.7) | |

| 200–350 | 601 | (24.2) | 146 | (24.1) | 143 | (23.9) | 136 | (26.3) | 75 | (17.0) | 102 | (31.5) | |

| 350–500 | 248 | (10.0) | 75 | (12.5) | 55 | (9.2) | 46 | (8.9) | 40 | (9.0) | 32 | (9.9) | |

| >500 | 103 | (4.1) | 32 | (5.3) | 19 | (3.2) | 20 | (3.9) | 16 | (3.6) | 16 | (4.9) | |

| CD4, cells/µL | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| <100 | 312 | (13.0) | 154 | (26.2) | 115 | (20.0) | 20 | (4.0) | 19 | (4.5) | 4 | (1.3) | |

| 100–200 | 236 | (9.9) | 76 | (13.0) | 78 | (13.5) | 47 | (9.4) | 29 | (6.9) | 6 | (1.9) | |

| 200–350 | 477 | (19.2) | 122 | (20.3) | 139 | (23.2) | 101 | (19.5) | 76 | (17.0) | 39 | (12.0) | |

| 350–500 | 503 | (20.2) | 110 | (18.3) | 121 | (20.2) | 115 | (22.2) | 85 | (19.2) | 72 | (22.2) | |

| >500 | 864 | (34.8) | 125 | (20.8) | 123 | (20.5) | 216 | (41.7) | 211 | (47.7) | 190 | (58.6) | |

| HIV VL, d copies/mL | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| <200 | 1600 | (64.4) | 176 | (29.2) | 317 | (53.3) | 438 | (84.6) | 371 | (83.9) | 296 | (91.4) | |

| ≥200 | 812 | (32.7) | 410 | (67.8) | 256 | (42.7) | 62 | (12.0) | 61 | (13.8) | 25 | (7.7) | |

| Unknown | 73 | (2.9) | 18 | (3.0) | 24 | (4.0) | 18 | (3.5) | 10 | (2.3) | 3 | (0.9) | |

| Smoking status | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Never | 533 | (21.4) | 187 | (30.9) | 156 | (26.2) | 18 | (3.5) | 71 | (16.1) | 101 | (31.2) | |

| Current | 964 | (38.8) | 174 | (28.7) | 203 | (34.1) | 300 | (57.9) | 208 | (47.1) | 79 | (24.4) | |

| Previous | 598 | (24.1) | 91 | (15.1) | 124 | (20.7) | 165 | (31.9) | 116 | (26.2) | 102 | (31.5) | |

| Unknown | 390 | (15.7) | 152 | (25.2) | 114 | (19.0) | 35 | (6.8) | 47 | (10.6) | 42 | (13.0) | |

| Diabetes e | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| No | 2204 | (88.7) | 553 | (91.5) | 532 | (89.1) | 451 | (87.1) | 395 | (89.4) | 273 | (84.3) | |

| Yes | 228 | (9.2) | 35 | (5.8) | 41 | (6.8) | 64 | (12.4) | 43 | (9.7) | 45 | (13.9) | |

| Unknown | 53 | (2.1) | 16 | (2.7) | 24 | (4.0) | 3 | (0.6) | 4 | (0.9) | 6 | (1.9) | |

| Prior AIDS | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| No | 1564 | (62.9) | 439 | (72.6) | 377 | (63.4) | 310 | (59.8) | 218 | (49.3) | 219 | (67.6) | |

| Yes | 921 | (37.1) | 165 | (27.4) | 219 | (36.6) | 208 | (40.2) | 224 | (50.7) | 105 | (32.4) | |

| Prior NADC | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| No | 2308 | (92.9) | 591 | (97.8) | 567 | (95.0) | 460 | (88.8) | 401 | (90.7) | 289 | (89.2) | |

| Yes | 177 | (7.1) | 13 | (2.2) | 30 | (5.0) | 58 | (11.2) | 41 | (9.3) | 35 | (10.8) | |

| Prior CVD f | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| No | 2306 | (92.8) | 580 | (96.0) | 576 | (96.5) | 459 | (88.6) | 407 | (92.1) | 284 | (87.7) | |

| Yes | 141 | (5.7) | 8 | (1.3) | 10 | (1.7) | 55 | (10.6) | 32 | (7.2) | 36 | (11.1) | |

| Unknown | 38 | (1.5) | 16 | (2.7) | 11 | (1.8) | 4 | (0.8) | 3 | (0.7) | 4 | (1.2) | |

| Comorbidity burden g (number of comorbidities) | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 389 | (15.7) | 194 | (32.2) | 112 | (18.7) | 37 | (7.1) | 28 | (6.3) | 18 | (5.6) | |

| 1 | 773 | (31.1) | 235 | (38.7) | 201 | (38.6) | 141 | (27.2) | 106 | (24.0) | 62 | (19.1) | |

| 2 | 711 | (28.6) | 115 | (19.1) | 163 | (27.4) | 157 | (30.3) | 160 | (36.2) | 115 | (35.3) | |

| 3+ | 612 | (24.6) | 60 | (10.0) | 92 | (15.4) | 183 | (35.3) | 148 | (33.5) | 129 | (39.8) | |

| Cancer stage h | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Localized | 776 | (31.2) | 98 | (16.1) | 64 | (10.7) | 124 | (23.9) | 290 | (65.6) | 201 | (62.0) | |

| Disseminated | 567 | (22.8) | 52 | (8.6) | 105 | (17.5) | 298 | (57.5) | 64 | (14.5) | 48 | (14.8) | |

| Unknown | 1142 | (46.0) | 454 | (75.2) | 428 | (71.8) | 96 | (18.5) | 88 | (19.9) | 75 | (23.1) | |

| Cancer treatment | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Chemotherapy | 239 | (9.6) | 30 | (4.9) | 89 | (14.9) | 57 | (11.0) | 56 | (12.7) | 7 | (2.2) | |

| Radiotherapy | 145 | (5.8) | 5 | (0.8) | 7 | (1.2) | 40 | (7.7) | 58 | (13.1) | 35 | (10.8) | |

| Surgery | 125 | (5.0) | 8 | (1.3) | 3 | (0.5) | 38 | (7.3) | 33 | (7.5) | 43 | (13.3) | |

| Endocrine therapy | 26 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.2) | 1 | (0.2) | 0 | (0.0) | 24 | (7.4) | |

| Immune therapy | 36 | (1.4) | 2 | (0.3) | 18 | (3.0) | 15 | (2.9) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.3) | |

| Antineoplastic therapy | 22 | (0.9) | 3 | (0.5) | 11 | (1.8) | 2 | (0.4) | 2 | (0.4) | 4 | (1.2) | |

| Unknown | 1911 | (76.9) | 512 | (84.7) | 486 | (81.5) | 358 | (69.1) | 337 | (76.2) | 218 | (67.3) | |

| Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | p | |

| Baseline date (month/year) | 12/11 | (01/08, 07/15) | 09/09 | (03/07, 04/14) | 04/10 | (10/06, 08/14) | 12/12 | (04/09, 10/16) | 04/12 | (11/08, 11/15) | 04/14 | (11/10, 02/18) | <0.001 |

| Age, years | 52 | (43, 61) | 43 | (36, 51) | 48 | (41, 56) | 57 | (51, 63) | 52 | (46, 58) | 64 | (59, 69) | |

| CD4 nadir c, cells/µL | 146 | (49, 263) | 160 | (42, 290) | 137 | (49, 250) | 150 | (60, 247) | 108 | (26, 220) | 180 | (80, 285) | <0.001 |

| CD4, cells/µL | 399 | (212, 600) | 280 | (90, 469) | 300 | (141, 465) | 441 | (281, 684) | 502 | (299, 718) | 562 | (430, 729) | <0.001 |

| VL d, copies/mL | 50 | (39, 3855) | 18,410 | (54, 152,600) | 70 | (50, 27,274) | 50 | (29, 50) | 50 | (39, 50) | 40 | (19, 50) | <0.001 |

| Duration of HIV years | 11.2 | (3.8, 19.1) | 3.6 | (0.2, 9.8) | 7.2 | (2.1, 14.9) | 16.4 | (9.8, 22.0) | 16.5 | (10.7, 22.6) | 16.1 | (8.2, 22.7) | <0.001 |

| Duration on ART, years | 9.9 | (3.2, 15.9) | 1.9 | (0.1, 10.3) | 5.9 | (1.0, 11.2) | 12.9 | (7.4, 17.8) | 13.7 | (8.8, 17.9) | 13.6 | (7.4, 18.9) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; MSM, men who have sex with men; IDU, injecting drug use; ARV, antiretroviral; ART, antiretroviral therapy; VL, viral load; AIDS, acquired immune deficiency syndrome; NADC, non-AIDS-defining cancer; IQR, interquartile range. Due to small numbers, Australia was combined with Northern Europe, and Eastern Central Europe was combined with Eastern Europe. a The mixture of sex and gender is collected. b The mixture of ethnicity/race is collected. Information on ethnicity/race is prohibited in several of the participating cohorts. c CD4 count was taken as the lowest CD4 count prior to baseline. If no CD4 count was measured, the first measurement within 12 weeks after baseline was used. d VL measurements below the level of detection but unknown reported lower limits of detection of the HIV-RNA assay were included to the category of < 200 copies/mL. e Diabetes was defined by a reported diagnosis, use of anti-diabetic medication, glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L, and/or HbA1c ≥ 6.5% or ≥48 mmol/mol. f Cardiovascular disease (CVD) was defined using a composite diagnosis of myocardial infarction, stroke or an invasive cardiovascular procedure. g Comorbidities included prior AIDS-defining and non-AIDS-defining cancers, AIDS events, chronic kidney disease (CKD), CVD, hypertension, diabetes and dyslipidemia. Hypertension was defined as two consecutive systolic blood pressure (SBP) measurements ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) measurements ≥ 90 mmHg, performed on different days; one single SBP measurement ≥ 140 mmHg and/or DBP measurement ≥ 90 mmHg with the use of antihypertensive medication within six months of this measurement; or the initiation of antihypertensives without a recorded high BP reading. CKD was defined as confirmed if there were 2 consecutive measurements of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) ≤ 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 measured at least 3 months apart or a 25% eGFR decrease when eGFR ≤ 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2. Dyslipidemia was defined as total cholesterol > 239.4 mg/dL, HDL cholesterol < 34.7 mg/dL, triglyceride > 203.55 mg/dL or use of lipid-lowering treatments. h Disseminated cancer stage defined as metastasized cancer. Cancer stage for NHL and KS was not collected in D:A:D.

3.2. Mortality After Cancer

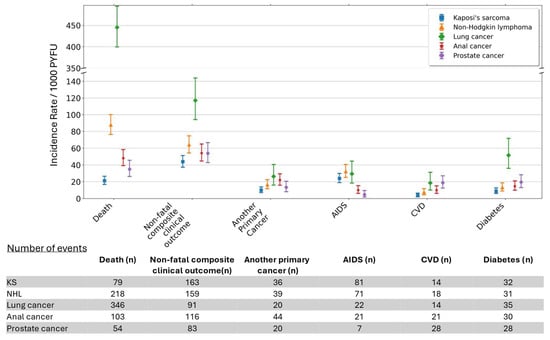

Median follow-up after cancer overall was 3.1 years [IQR 0.8–7.1], with participants contributing a total of 10,630 PYFU. Participants with lung cancer had the shortest median follow-up time after cancer (0.7 years [IQR 0.3–1.7]), followed by those with NHL (2.5 [0.5–6.8]), anal cancer (4.0 [1.7–7.4]), prostate cancer (4.0 [1.7–6.8]) and KS (6.4 [2.9–8.8]), likely reflected in the differences in mortality after these cancers (Figure 2). Almost 21% of participants with cancer had died at one year after diagnosis (Table 2). The crude IRs of mortality varied by cancer type and were markedly higher after lung cancer (n = 346; 445.4/1000 PYFU [95% CI 399.7, 494.9]), with a 49% and 64% fatality rate at one and three years after diagnosis. Conversely, the lowest mortality incidence was seen after KS (n = 79; IR 21.3/1000 PYFU [16.9, 26.6]), with one- and three-year fatality rates of 8% and 11%.

Cancer was a leading underlying cause of death across all studied cancers, with 87% of all deaths after lung cancer, 72% after NHL, 52% after anal cancer, 41% after prostate cancer and 29% after KS. For KS and NHL, non-cancer AIDS events were also common causes of deaths (28% and 22%, respectively; Table A1).

Figure 2.

Crude Incidence Rates (IRs) per 1000 person years of follow-up for mortality and clinical events after cancer diagnosis. Non-fatal composite clinical outcome is a composite of another primary cancer, AIDS, CVD and diabetes. Abbreviations: AIDS, acquired immune deficiency syndrome; CVD, cardiovascular disease; KS, Kaposi’s sarcoma; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; PYFU, person years of follow-up.

Table 2.

Cumulative percentage experiencing mortality and non-fatal clinical outcomes after the most common cancers by years of follow-up.

Table 2.

Cumulative percentage experiencing mortality and non-fatal clinical outcomes after the most common cancers by years of follow-up.

| Overall (%) | Kaposi’s Sarcoma (%) | Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (%) | Lung Cancer (%) | Anal Cancer (%) | Prostate Cancer (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-year follow-up | ||||||

| Death | 20.6 | 7.8 | 28.2 | 49.4 | 7.2 | 2.2 |

| Non-fatal CCO | 11.5 | 12.3 | 14 | 11.6 | 10 | 7.4 |

| Cancer | 3.1 | 2.2 | 3.5 | 3.1 | 4.5 | 2.2 |

| AIDS | 5.3 | 9.3 | 8.9 | 2.3 | 2 | 0.6 |

| CVD | 1.3 | 0.8 | 1 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 2.5 |

| Diabetes | 3.4 | 2.3 | 3.5 | 5 | 2.9 | 3.1 |

| 2-year follow-up | ||||||

| Death | 25.1 | 9.5 | 30.9 | 60 | 12 | 5.6 |

| Non-fatal CCO | 13.9 | 14 | 16 | 13 | 14.3 | 10.8 |

| Cancer | 4.1 | 3.3 | 4.5 | 3.5 | 6.3 | 3.1 |

| AIDS | 6.1 | 10 | 9.7 | 2.9 | 3.6 | 0.6 |

| CVD | 1.8 | 1 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 3.1 |

| Diabetes | 4.3 | 3.2 | 3.8 | 5.8 | 4.1 | 4.9 |

| 3-year follow-up | ||||||

| Death | 27.6 | 10.5 | 32.4 | 64.1 | 15.8 | 8.3 |

| Non-fatal CCO | 15.7 | 16.3 | 17 | 14.1 | 16.1 | 14.2 |

| Cancer | 4.7 | 4 | 4.7 | 3.7 | 7.2 | 4 |

| AIDS | 6.7 | 11.1 | 10.2 | 3.3 | 4.3 | 0.9 |

| CVD | 2.2 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 3.2 | 4 |

| Diabetes | 4.7 | 3.7 | 4 | 6.2 | 4.3 | 6.2 |

Abbreviations: non-fatal CCO, non-fatal composite clinical outcome; AIDS, acquired immune deficiency syndrome; CVD, cardiovascular disease.

3.3. Predictors of Mortality After Cancer

Risk factors for mortality following lung cancer, NHL and anal cancer are shown in a heat map in Table 3. Due to low mortality rates, we were underpowered to analyze risk factors for mortality after KS and prostate cancer.

Table 3.

Heat map of Adjusted Incidence Rate Ratios (aIRRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for key predictors of mortality and non-fatal composite clinical outcome (CCO) after lung cancer, non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), anal cancer, Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) and prostate cancer *.

After adjustment, mortality incidence declined over time by 7–10% per calendar year following NHL and anal cancer, respectively, while the decline for lung cancer was not significant after adjustment for other risk factors. Each increment of 10 years in age at cancer diagnosis was associated with 24% and 45% increased mortality for participants with NHL and anal cancer, respectively, but was not significantly associated with mortality following lung cancer. Mortality was also twofold higher for participants with disseminated anal cancer and nearly fivefold higher for those with disseminated lung cancer compared to participants with localized cancer of the same type. A higher time-updated CD4 count (per 100 cells/µL increment) was associated with reductions in mortality of 40%, 17% and 15% for NHL, anal cancer and lung cancer, respectively. Having another primary cancer during follow-up doubled the mortality risk after NHL and tripled it after anal cancer, whilst other comorbidities were not significant risk factors in our univariable model and, therefore, were not included in the multivariable model. Participants with injecting drug use (IDU) as the HIV acquisition mode had a threefold higher risk of anal cancer mortality compared to men who have sex with men (MSM), but this association was based on low numbers (20 events in persons with IDU and 61 MSM).

3.4. Non-Fatal Clinical Outcomes After Cancer

Overall, almost 12% of participants had a non-fatal CCO one year after cancer diagnosis, increasing to 16% by three years. The IR of non-fatal CCO after cancer was substantially higher for lung cancer (IR 117.1/1000 PYFU [95% CI 94.31, 143.82]) than for the other cancers considered (Figure 2).

The most common individual non-fatal clinical outcome following cancer depended on the cancer type. For NHL and KS, another AIDS event was most common (IR 32.9 [95% CI 25.21, 40.72] per 1000 PYFU and 24.0 [19.08, 29.87], respectively), with 9% of individuals with these cancers experiencing an AIDS event by one year. For lung and prostate cancers, the most common event was diabetes (IR 51.7 [36.01, 71.90] and 19.6 [13.04, 28.36], respectively), whereas for anal cancer, it was another primary cancer (22.0 [15.98, 29.53]), with 5% of individuals experiencing another cancer by 1 year (Table 2). CVD was one of the least common individual clinical outcomes after cancer, with just 1% and 2% of all participants experiencing such an event at one and three years.

3.5. Predictors of Non-Fatal Outcomes After Cancer

Predictors of non-fatal CCO after each cancer are shown in Table 3. Higher time-updated CD4 counts were associated with a 28% and 17% (per 100 cells/µL) reduced risk of non-fatal CCO after KS and NHL, respectively. For lung, anal and prostate cancers, similar trends were seen, but they did not reach statistical significance. When AIDS events were excluded from the non-fatal CCO, the beneficial effect of a higher CD4 count remained only for KS (aIRR 0.96, 95% CI [0.78, 0.96]; Supplementary Table S1). VL was not significant in univariable models (apart from for KS).

Older age (per 10 years) was associated with a 34% increased risk of non-fatal CCO after anal cancer. Smoking doubled non-fatal CCO risks after anal cancer, KS and NHL. Further, for participants with NHL and KS, low BMI (<18.5) and high comorbidity burden (>3 conditions) increased non-fatal CCO risk by 2–3-fold.

No statistically significant predictors of non-fatal CCO were identified after lung and prostate cancers, likely due to insufficient statistical power.

3.6. Sensitivity Analyses

All findings were largely consistent across all sensitivity analyses.

4. Discussion

This is the first large multinational study examining incidence and predictors of mortality and non-fatal clinical outcomes after the most common cancers in people with HIV. With an increasing proportion of aging people with HIV at risk of cancer, insights into predictors—particularly the role of potential modifiable risk factors—contributing to morbidity and mortality post cancer are increasingly pertinent to continuously improve HIV care. We found that post-cancer prognosis and predictors of clinical outcomes varied by cancer type. Our findings illustrate the need for a personalized and holistic post-cancer management strategy for people with HIV after a cancer diagnosis.

Participants with lung cancer commonly presented with disseminated disease and had the highest rate of mortality, with almost 50% dying within the first year after diagnosis. These findings are consistent with prior findings in people with HIV and in the general population [2,28,29]. As such, in the general population, mortality after a lung cancer diagnosis has 5-year relative survival rates of 16–27% compared to, e.g., prostate cancer, with 96% [30]. Furthermore, we found no indication of improved prognosis of lung cancer mortality over time, which highlights a pressing need for earlier diagnosis and continued efforts to intervene against modifiable risk factors for lung cancer, especially smoking cessation. While smoking status did not impact mortality incidence following lung cancer in our analysis, the number of persons without a smoking history was very limited. Smoking is generally considered a risk factor for increased mortality in the general population following a lung cancer diagnosis [31]; this effect is most clearly established at 5 and 10 years post diagnosis, and conversely, current data regarding 1-year survival rates remain inconsistent [32,33]. It is also possible that current and former smokers are diagnosed with lung cancer at an earlier stage than non-smokers due to increased screening within this high-risk group, potentially mitigating short-term mortality risks [32,34].

Participants with lung cancer had a high rate of non-fatal CCO. Although there were relatively few events compared to other cancers (likely because participants died before experiencing a non-fatal CCO), the number of events relative to the short follow-up time remained high.

The high incidence of diabetes, especially after lung cancer, likely reflects the common use of corticosteroids in this population, as also noted in previous studies, including a recent US analysis [14,21,35]. Diabetes incidence was also increased after prostate cancer, where the substantially lower mortality risk ensured a longer follow-up time at risk of non-fatal events and, as also noted in other studies, could be related to both treatment effects and shared risk factors [14,35,36,37]. These findings highlight the importance of monitoring blood glucose, especially after lung and prostate cancer.

The incidence of AIDS events was, as expected, increased after NHL and KS, reflecting the often-close connection to recently diagnosed HIV with high VL, low CD4 count and other viral coinfections. However, the incidence of AIDS was also notably increased after lung cancer, although affecting a smaller proportion of persons (2–3%) and likely related to both the cancer itself and to cancer treatment-related immunosuppression [18].

Participants with anal cancer predominantly had localized disease at the time of diagnosis and low mortality rates. With the longer follow-up time at risk of other non-fatal outcomes, another primary cancer was the most common event after anal cancer, as also described in a more recent register study and possibly explained by shared risk [38].

Prior studies in the general population and one study in population with HIV have described increased CVD rates after several cancers; however, in our study, CVD rates were fairly low over follow-up [11,12,13,21].

Among the strongest predictors for mortality were, as expected, disseminated disease for lung and anal cancer, whilst cancer stage did not reach statistical significance for non-fatal CCO after these cancers. Other strong mortality predictors were age and history of a prior (different) cancer for anal cancer and NHL. In contrast, age was not significantly associated with lung cancer mortality, potentially related to the high proportion with disseminated disease. Age only reached significance for non-fatal CCO after anal cancer, although the trend was in a similar direction for the other cancers.

Even in an aging population, mortality after NHL and anal cancer gradually improved over calendar time, likely reflecting, in part, effective and well-tolerated ART and improvements in cancer treatment regimens. Our follow-up precedes that of the ANCHOR study, demonstrating encouraging benefits of systematic screening for anal cancer and treatment of pre-cancer lesions [39].

Consistent with predominantly older studies focusing on cancer overall rather than individual cancers, we found that higher CD4 counts significantly decreased mortality rates after NHL, as well as after anal and lung cancers [40,41]; predictors of mortality were not assessed after KS and prostate cancer due to low mortality rates. Higher CD4 counts also predicted lower non-fatal CCO incidence after NHL and KS, although, particularly for NHL, this, to a large extent, was attributed to other AIDS events.

Similar but non-significant trends were seen for CCO after lung, anal and prostate cancers, also supporting the pathogenesis of these events in individuals without cancer [42,43]. Investigation of predictors of CD4 count trajectories after cancer is the focus of another ongoing project in RESPOND [44].

Consistent with our observation that cancer was the most common cause of death, multimorbidity did not substantially impact mortality risk. A different pattern was observed for non-fatal CCO; having >3 comorbidities substantially increased the incidence of non-fatal CCO, particularly after NHL and KS. Similar but non-significant trends were seen for anal and prostate cancers. Additionally, for participants with KS and NHL, other modifiable risk factors such as low BMI and a history of smoking also increased the risk of non-fatal CCO. Low BMI was predominantly associated with the cancers previously termed AIDS-defining cancers, likely serving as a proxy for overall frailty of individuals with AIDS as opposed to those experiencing a cancer without a similar degree of immunosuppression. Conversely, we observed no association between low BMI and CCO after cancers in participants with non-AIDS-defining cancers.

Our findings collectively underscore the need for a multidisciplinary approach to post-cancer care in people with HIV to address modifiable risk factors, including nutritional support, smoking cessation and proactive management of comorbidities.

Key strengths of our study include having a large and diverse study population across Europe, Australia and the US over extended calendar time, together with systematic and rigorous data collection and adjudication of clinical events. However, our study also has several limitations. Due to low numbers of non-fatal clinical events after cancers, we were unable to study predictors for these events individually. Additionally, even with the combined data from two of the largest longitudinal studies of people with HIV, the median follow-up time after cancer was relatively short; therefore, we may have underestimated the true disease burden after these cancers. Lack of data on cancer stage for some cancers (for D:A:D) and histological subtypes (RESPOND) prevented analysis of mortality differences between cancer subtypes. Missing data on specific cancer treatments, especially from D:A:D, precluded us from studying their impacts on participants’ death rates and other outcomes. Finally, data to further quantify tobacco usage, including pack years, was unfortunately not systematically available in D:A:D and RESPOND.

5. Conclusions

In this large multicohort study of people with HIV, rates and predictors of clinical outcomes after the most common cancers varied by cancer type. Lung cancer was often disseminated at the time of diagnosis and had the most unfavorable prognosis. Encouragingly, mortality after anal cancer and NHL declined over time. Among the strongest mortality predictors were disseminated cancer for lung and anal cancers and prior cancer and older age for NHL and anal cancer. Higher CD4 counts reduced rates of both fatal and non-fatal events after several cancers. Smoking, low BMI and multimorbidity increased incidence of non-fatal CCO, especially after KS and NHL. Our findings call for personalized and multidisciplinary post-cancer care strategies to improve long-term outcomes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cancers17244000/s1, Table S1: Heatmap of Adjusted Incidence Rate Ratios (aIRR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for key predictors of non-AIDS composite clinical outcome (CCO) after lung cancer, non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), anal cancer, Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) and prostate cancer.

Author Contributions

A.T., supervised by J.L., L.R., L.P. and L.G., conceived the idea and developed the project proposal and a statistical analysis plan. All authors reviewed the proposal and analysis plan. L.G. performed the statistical analysis, which was reviewed by all authors. A.T. developed the first draft of the manuscript and revised the subsequent drafts. A.T., L.R., L.P. and L.G. reviewed all versions of the manuscript and interpreted the data. P.D., P.E.T., A.E., C.M. (Charlotte Martin), C.M. (Cristina Mussini), F.W., A.C. (Antonella Cingolani), C.L., A.C. (Antonella Castagna), K.P., C.A.S., F.B., J.L., M.B., S.H., C.C., A.A., K.G.-P., H.G., A.M. and L.A.Y. contributed to the interpretation of data, reviewed the final draft of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The International Cohort Consortium of Infectious Disease (RESPOND) is supported by participating cohorts providing data in-kind and/or statistical support: The CHU St Pierre Brussels HIV Cohort, The Austrian HIV Cohort Study, The Australian HIV Observational Database, The AIDS Therapy Evaluation in the Netherlands National Observational HIV cohort, The EuroSIDA cohort, The Frankfurt HIV Cohort Study, The Georgian National AIDS Health Information System, The Nice HIV Cohort, The ICONA Foundation, The Modena HIV Cohort, The PISCIS Cohort Study, The Swiss HIV Cohort Study, The Swedish InfCare HIV Cohort, The Royal Free HIV Cohort Study, The San Raffaele Scientific Institute, The University Hospital Bonn HIV Cohort, The University of Cologne HIV Cohort, The Brighton HIV Cohort and The National Croatian HIV cohort. RESPOND is further financially supported by ViiV Healthcare LLC (Grant number 207709); Merck, Sharp and Dohme (Grant number LKR196747); Gilead Sciences (Grant number CO-EU-311-4339); the Centre of Excellence for Health, Immunity and Infections (CHIP); and the AHOD cohort by grant No. GNT1050874 of the National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of participating centers as per local and national requirements.

Informed Consent Statement

Participants consented to share data with RESPOND according to local requirements. Participants were pseudonymized at enrolment by assignment of a unique identifier by the participating cohort before data transfer to the main RESPOND database. According to national or local requirements, all cohorts have approval to share data with RESPOND. Ethical approval was obtained, if required, from the relevant bodies for collection and sharing of data. Data are stored on secure servers at the RESPOND coordinating center in Copenhagen, Denmark, in accordance with current legislation and under approval by The Danish Data Protection Agency (approval number 2012-58-0004, RH-2018-15, 26 January 2018) under the EU General Data Protection Regulation (2016/679). All participating cohorts followed local or national guidelines or regulations regarding patient consent and ethical review. Of the countries with participating cohorts, only Australia and Switzerland require specific ethical approval for the entire D:A:D cohort, in addition to that required for their national cohorts (the Australian HIV Observational Database and the Swiss HIV Cohort Study); France (Nice and Aquitaine cohorts), Italy (ICONA cohort) and Belgium (Brussels Saint-Pierre cohort) do not require specific ethical approval more than that required for the individual cohorts; and the Netherlands (AIDS Therapy in the Netherlands project) does not require any specific ethical approval because data are provided as part of HIV care. For the EuroSIDA study, which includes the data from the Barcelona Antiretroviral Surveillance Study and Swedish cohorts, among participants from many European countries, each participating site has a contractual obligation to ensure that data collection and sharing are conducted in accordance with national legislation; each site’s principal investigator either maintains appropriate documentation from an ethical committee (if required by law) or has a documented written statement to say that this is not required.

Data Availability Statement

The RESPOND Scientific Steering Committee (SSC) encourages the submission of concepts for research projects. Online research concepts should be submitted to the RESPOND secretariat (respond.rigshospitalet@regionh.dk); for guidelines on how to submit research concepts, see the RESPOND governance and procedures point 6. The secretariat will direct the proposal to the relevant Scientific Interest Group, where the proposal will initially be discussed for scientific relevance before being submitted to the SSC for review. Once submitted to the SSC, the research concept’s scientific relevance, relevance to RESPOND’s ongoing scientific agenda, design, statistical power, feasibility and overlap with already approved projects will be assessed. Upon completion of the review, feedback will be provided to the proposer or proposers. In some circumstances, a revision of the concept might be requested. If the concept is approved for implementation, a writing group will be established, consisting of the proposers (up to seven people who were centrally involved in developing the concept), representatives from RESPOND cohorts and representatives from the Statistical Department and Coordinating Center. All individuals involved in the process of reviewing these research concepts are bound by confidentiality. All data within RESPOND from individual cohorts are de-identified. The present RESPOND data structure and a list of all collected variables and their definition can be found online. For any inquiries regarding data sharing, please contact the RESPOND secretariat (respond.rigshospitalet@regionh.dk).

Acknowledgments

D:A:D study group. D:A:D Participating Cohorts: Aquitaine, France; CPCRA, USA; NICE Cohort, France; ATHENA, The Netherlands; EuroSIDA, Europe; SHCS, Switzerland, AHOD, Australia; HIV-BIVUS, Sweden; St.Pierre Brussels Cohort, Belgium; BASS, Spain, The ICONA Foundation, Italy. D:A:D Steering Committee: Names marked with *, Chair with ¢: Cohort PIs: W El-Sadr * (CPCRA), G Calvo * (BASS), F Bonnet and F Dabis * (Aquitaine), O Kirk * and A Mocroft * (EuroSIDA), M Law * (AHOD), A d’Arminio Monforte * (ICONA), L Morfeldt * (HivBIVUS), C Pradier * (Nice), P Reiss * (ATHENA), R Weber * (SHCS), S De Wit * (Brussels). Cohort coordinators and data managers: A Lind-Thomsen (coordinator), R Salbøl Brandt, M Hillebreght, S Zaheri, FWNM Wit (ATHENA), A Scherrer, F Schöni-Affolter, M Rickenbach (SHCS), A Tavelli, I Fanti (ICONA), O Leleux, J Mourali, F Le Marec, E Boerg (Aquitaine), E Thulin, A Sundström (HIVBIVUS), G Bartsch, G Thompsen (CPCRA), C Necsoi, M Delforge (Brussels), E Fontas, C Caissotti, K Dollet (Nice), S Mateu, F Torres (BASS), K Petoumenos, A Blance, R Huang, R Puhr (AHOD), K Grønborg Laut, D Kristensen (EuroSIDA). Statisticians: CA Sabin *¢, AN Phillips *, DA Kamara, CJ Smith, A Mocroft *. D:A:D coordinating office: CI Hatleberg, A Lind-Thomsen, RS Brandt, D Raben, C Matthews, A Bojesen, AL Grevsen, JD Lundgren *, L Ryom ¢. Members of the D:A:D Oversight Committee: B Powderly *, N Shortman*, C Moecklinghoff *, G Reilly *, X Franquet *. D:A:D working group experts: Kidney: L Ryom ¢, A Mocroft *, O Kirk *, P Reiss *, C Smit, M Ross, CA Fux, P Morlat, E Fontas, DA Kamara, CJ Smith, JD Lundgren *. Mortality: CJ Smith, L Ryom ¢, CI Hatleberg, AN Phillips *, R Weber*, P Morlat, C Pradier *, P Reiss *, FWNM Wit, N Friis-Møller, J Kowalska, JD Lundgren *. Cancer: CA Sabin *¢, L Ryom ¢, CI Hatleberg, M Law *, A d’Arminio Monforte*, F Dabis *, F Bonnet*, P Reiss *, FWNM Wit, CJ Smith, DA Kamara, J Bohlius, M Bower, G Fätkenheuer, A Grulich, JD Lundgren *. External endpoint reviewers: A Sjøl (CVD), P Meidahl (oncology), JS Iversen (nephrology). RESPOND Study Group: AIDS Therapy Evaluation in the Netherlands Cohort (ATHENA): F Wit, M van der Valk, M Hillebregt, Stichting HIV Monitoring (SHM), Amsterdam, Netherlands; The Australian HIV Observational Database (AHOD): K Petoumenos, M Law, J Hutchinson, D Rupasinghe, W Min Han, UNSW, Sydney, Australia; Austrian HIV Cohort Study (AHIVCOS): R Zangerle, H Appoyer, Medizinische Universität Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria; Brighton HIV cohort: J Vera, A Clarke, B Broster, L Barbour, D Carney, L Greenland, R Coughlan, Lawson Unit, Royal Sussex County Hospital, University Hospitals Sussex NHS Foundation Trust, Brighton, United Kingdom; CHU Saint-Pierre: C Martin, S De Wit, M Delforge, Centre de Recherche en Maladies Infectieuses a.s.b.l., Brussels, Belgium; Croatian HIV cohort: J Begovac, University Hospital of Infectious Diseases, Zagreb, Croatia; EuroSIDA Cohort: G Wandeler, CHIP, Rigshospitalet, RegionH, Copenhagen, Denmark; Frankfurt HIV Cohort Study: C Stephan, M Bucht, Johann Wolfgang Goethe-University Hospital, Frankfurt, Germany; Infectious Diseases, AIDS and Clinical Immunology Research Center (IDACIRC): A Abutidze, O Chokoshvili, Infectious Diseases, AIDS and Clinical Immunology Research Center, Tbilisi, Georgia; Italian Cohort Naive Antiretrovirals (ICONA): A d’Arminio Monforte, A Rodano, A Tavelli, ASST Santi Paolo e Carlo, Milan, Italy; I Fanti, Icona Foundation, Milan, Italy; Modena HIV Cohort: C Mussini, V Borghi, M Menozzi, A Cervo, Università degli Studi di Modena, Modena, Italy; Nice HIV Cohort: C Pradier, E Fontas, K Dollet, C Caissotti, Université Côte d’Azur et Centre Hospitalier Universitaire, Department of Public Health, Nice, France; PISCIS Cohort Study: J Casabona, JM Miro, JM Llibre, A Riera, J Reyes- Urueña, Centre Estudis Epidemiologics de ITS i VIH de Catalunya (CEEISCAT), Badalona, Spain; Royal Free Hospital Cohort: F Burns, C Smith, F Lampe, C Chaloner, Royal Free Hospital, University College London, London, United Kingdom; San Raffaele Scientific Institute: A Castagna, A Lazzarin, A Poli, R Lolatto, Università Vita-Salute San Raffaele, Milano, Italy; Swedish InfCare HIV Cohort: C Carlander, A Sönnerborg, P Nowak, J Vesterbacka, L Mattsson, D Carrick, K Stigsäter, Department of Infectious Diseases, Karolinska University Hospital, and Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine Huddinge, Karolinska Institutet, Sweden; Swiss HIV Cohort Study (SHCS): H Günthard, B Ledergerber, H Bucher, K Kusejko, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland; University Hospital Bonn: JC Wasmuth, J Rockstroh, Bonn, Germany; University Hospital Cologne: C Lehmann, G Fätkenheuer, M Scherer, G Sauer, Cologne, Germany; RESPOND Executive Committee: L Ryom *, K Petoumenos *, J Rooney, M Dunbar, R Campo, C Mussini, C Martin, J van Wyk, H Günthard, J Lundgren, V Vannappagari, L Young, R Zangerle (* Chairs). RESPOND Scientific Steering Committee: J Lundgren *, H Günthard *, J Begovac, C Martin, F Burns, A Castagna, R Campo, D Thorpe, J van Wyk, J Kowalska, C Mussini, L Peters, O Kirk, H Butcher, J Vera, K Petoumenos, C Pradier, D Raben, J Rooney, L Ryom, C Carlander, V Vannappagari, C Lehmann, N Dedes, J Rockstroh, A Volny-Anne, F Wit, L Young, R Zangerle (* Chairs). RESPOND Cancer Working Group Members: L Greenberg, A Timiryasova, L Ryom, B Neesgaard, F Wit, A Castagna, C Duvivier, JJ Vehrechild, C Hatleberg, E Fontas, P Gabunia, H Bucher, A Borges, JM Miro, J Hoy, M Law, PM Peterson, V Vannappagari, A Marongiu, I McNicholl, F Rogatto, N Jaschinski, L Young, G Clifford, M Bower, L Peters, K Petoumenos, F Chammartin, C Muccini, J Brännström, C Carlander, M Bottanelli, S Malnström. External Clinical Reviewers: Kirstine Lærum Sibilitz (Clinical Cardiology), P Meidal Petersen (Clinical Oncology). Community Representatives: A Volny-Anne, N Dedes, L Mendão (European AIDS Treatment Group), E Dixon Williams (UK). RESPOND Staff: Coordinating Centre and Data Management: N Jaschinski, A Timiryasova, B Neesgaard, O Valdenmaier, M Gardizi, TW Elsing, L Ramesh Kumar, S Shahi, JF Larsen, D Raben, L Peters, L Ryom. Statistical Staff: L Greenberg, L Bansi-Matharu, K Petoumenos, W Min Han, W Bannister.

Conflicts of Interest

P.D. has received research grants, served on speakers’ bureaus or advisory panels, and earned speaking fees from Janssen & Cilag, Gilead Sciences, Merck, Sharp & Dohme, ViiV Healthcare, Theratechnologies, and Ferrer International. P.T.’s institution has received grant support, lecture fees and support for educational activities from Gilead, Viiv and MSD. None of these amounts went to him personally. F.W. has participated in advisory board for ViiV Healthcare, all paid to his institution. C.L. reported receiving grants from Gilead; receiving advisory fees from Viiv, Pfizer, Novartism BioTech, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Gilead. A.C. (Antonella Castagna) received honoraria for speaking at symposia and Advisory board for the following: MSD, Gilead Sciences, ViiV Healthcare, Johnson & Johnson. K.P.’s institution has received unrestricted research grants from ViiV healthcare Australia and Gilead Sciences Australia. C.S. has received financial support for the preparation and delivery of educational materials, and for participation in advisory boards and speaker panels from Gilead Sciences, ViiV Healthcare and MSD. C.C. has received lecture, moderator and advisory board fees paid to her institution. H.G., A.M., L.Y. are employees of ViiV Healthcare, Gilead Sciences and MSD, respectively.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| AIDS | Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome |

| ART | Antiretroviral therapy |

| KS | Kaposi’s sarcoma |

| NHL | Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma |

| IR | Incidence rate |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CCO | Composite clinical outcome |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| VL | Viral load |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| PYFU | Person years of follow-up |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| IDU | Injecting drug use |

| MSM | Men who have sex with men |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Causes of death after all cancers, Kaposi’s sarcoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, lung cancer, anal cancer and prostate cancer.

Table A1.

Causes of death after all cancers, Kaposi’s sarcoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, lung cancer, anal cancer and prostate cancer.

| Overall, All Cancers (N = 800) | Kaposi’s Sarcoma (N = 79) | Non-Hodgkins Lymphoma (N = 218) | Lung Cancer (N = 346) | Anal Cancer (N = 103) | Prostate Cancer (N = 54) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |

| Cause of death | ||||||||||||

| AIDS events (non-cancer) | 51 | (6.4) | 22 | (27.8) | 24 | (11.0) | 2 | (0.6) | 3 | (2.9) | 0 | (0.0) |

| AIDS malignancy | 184 | (23.0) | 23 | (29.1) | 157 | (72.0) | 1 | (0.3) | 3 | (2.9) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Infection | 6 | (0.8) | 1 | (1.3) | 1 | (0.5) | 1 | (0.3) | 2 | (1.9) | 1 | (1.9) |

| Bacterial infection | 10 | (1.2) | 6 | (7.6) | 0 | (0.0) | 2 | (0.6) | 2 | (1.9) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Pneumonia | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.9) |

| HBV | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.5) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| HCV | 6 | (0.8) | 2 | (2.5) | 2 | (0.9) | 1 | (0.3) | 1 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.5) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Anal cancer | 58 | (7.2) | 3 | (3.8) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 54 | (52.4) | 1 | (1.9) |

| Bladder cancer | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Chronic lymphoid leukemia | 2 | (0.2) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.5) | 1 | (0.3) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Connective tissue cancer | 3 | (0.4) | 0 | (0.0) | 2 | (0.9) | 1 | (0.3) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Esophagus cancer | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.5) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Gallbladder cancer | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Gynecologic cancer | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.5) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Head and neck cancer | 2 | (0.2) | 1 | (1.3) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 2 | (0.2) | 0 | (0.0) | 2 | (0.9) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Liver cancer | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.5) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Lung cancer | 311 | (38.9) | 1 | (1.3) | 2 | (0.9) | 300 | (86.7) | 3 | (2.9) | 5 | (9.3) |

| Metastasis of adenocarcinoma | 2 | (0.2) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 2 | (0.6) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Multiple myeloma | 1 | (0.1) | 1 | (1.3) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Pancreatic cancer | 2 | (0.2) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.5) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.9) |

| Prostate cancer | 22 | (2.8) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 22 | (40.7) |

| Rectum cancer | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Stomach cancer | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Unspecified leukemia | 2 | (0.2) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.5) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Unspecified Malignancy | 30 | (3.8) | 4 | (5.1) | 4 | (1.8) | 16 | (4.6) | 5 | (4.9) | 1 | (1.9) |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 3 | (0.4) | 1 | (1.3) | 1 | (0.5) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.9) |

| Heart or vascular disease | 5 | (0.6) | 2 | (2.5) | 1 | (0.5) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 1 | (1.9) |

| Myocardial Iinfarction or other ischemic heart disease | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Lung embolus | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.3) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Other ischemic heart disease | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.9) |

| Stroke | 8 | (1.0) | 1 | (1.3) | 2 | (0.9) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 4 | (7.4) |

| Chronic obstructive lung disease | 3 | (0.4) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 3 | (5.6) |

| Chronic viral hepatitis | 2 | (0.2) | 1 | (1.3) | 1 | (0.5) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Degenerative disorders of the CNS | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.5) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Digestive system disease | 2 | (0.2) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 1 | (1.9) |

| Hematological disease | 1 | (0.1) | 1 | (1.3) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Renal failure | 2 | (0.2) | 1 | (1.3) | 1 | (0.5) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Respiratory disease | 2 | (0.2) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.5) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Psychiatric disease | 4 | (0.5) | 2 | (2.5) | 1 | (0.5) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.9) |

| Mood or affective disorder | 2 | (0.2) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 2 | (1.9) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Accident or other violent death | 1 | (0.1) | 1 | (1.3) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Acute intoxication | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Suicide | 2 | (0.2) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 2 | (1.9) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Other causes | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.9) |

| Unknown | 53 | (6.6) | 5 | (6.3) | 7 | (3.2) | 18 | (5.2) | 14 | (13.6) | 9 | (16.7) |

N—total number of deaths after each type of cancer.

References

- Hernández-Ramírez, R.U.; Shiels, M.S.; Dubrow, R.; Engels, E.A. Cancer risk in HIV-infected people in the USA from 1996 to 2012: A population-based, registry-linkage study. Lancet HIV 2017, 4, e495–e504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, T.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Yang, L.; Wang, H.; Li, L.; Wang, J.; Qian, H.; Clifford, G.; Zou, H. Incidence and mortality of non-AIDS-defining cancers among people living with HIV: A systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine 2022, 52, 101613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borges, Á.H.; Dubrow, R.; Silverberg, M.J. Factors contributing to risk for cancer among HIV-infected individuals, and evidence that earlier combination antiretroviral therapy will alter this risk. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2014, 9, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocroft, A.; Petoumenos, K.; Wit, F.; Vehreschild, J.J.; Guaradli, G.; Miro, J.M.; Greenberg, L.; Oellinger, A.; Egle, A.; Guenthard, H.; et al. The interrelationship of smoking, CD4+cell count, viral load and cancer in persons living with HIV. AIDS 2021, 35, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, L.; Ryom, L.; Bakowska, E.; Wit, F.; Bucher, H.C.; Braun, D.L.; Phillips, A.; Sabin, C.; d’Arminio Monforte, A.; Zangerle, R.; et al. Trends in Cancer Incidence in Different Antiretroviral Treatment-Eras amongst People with HIV. Cancers 2023, 15, 3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.J.; Ryom, L.; Weber, R.; Morlat, P.; Pradier, C.; Reiss, P.; Kowalska, J.; de Wit, S.; Law, M.; el Sadr, W.; et al. Trends in underlying causes of death in people with HIV from 1999 to 2011 (D:A:D): A multicohort collaboration. Lancet 2014, 384, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trickey, A.; McGinnis, K.; Gill, M.J.; Abgrall, S.; Berenguer, J.; Wyen, C.; Hessamfar, M.; Reiss, P.; Kusejko, K.; Silverberg, M.J.; et al. Longitudinal trends in causes of death among adults with HIV on antiretroviral therapy in Europe and North America from 1996 to 2020: A collaboration of cohort studies. Lancet HIV 2024, 11, e176–e185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tusch, E.; Ryom, L.; Pelchen-Matthews, A.; Mocroft, A.; Elbirt, D.; Oprea, C.; Gunthard, H.F.; Staehelin, C.; Zangerle, R.; Suarez, I.; et al. Trends in Mortality in People With Human Immunodeficiency Virus From 1999 through 2020: A Multicohort Collaboration. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024, 79, 1242–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coghill, A.E.; Shiels, M.S.; Suneja, G.; Engels, E.A. Elevated cancer-specific mortality among HIV-infected patients in the United States. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 2376–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.L.; Sarovar, V.; Lam, J.O.; Leyden, W.A.; Alexeeff, S.E.; Lea, A.N.; Hechter, R.C.; Hu, H.; Marcus, J.L.; Yuan, Q.; et al. Excess Mortality in Persons with Concurrent HIV and Cancer Diagnoses: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2024, 33, 1698–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armenian, H.; Xu, L.; Ky, B.; Sun, C.; Farol, L.T.; Pal, S.K.; Douglas, P.S.; Bhatia, S.; Chao, C. Cardiovascular disease among survivors of adult-onset cancer: A community-based retrospective cohort study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 1122–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoormans, D.; Vissers, P.A.J.; van Herk-Sukel, M.P.P.; Denollet, J.; Pedersen, S.S.; Dalton, S.O.; Rottmann, N.; van de Poll-Franse, L. Incidence of cardiovascular disease up to 13 year after cancer diagnosis: A matched cohort study among 32 757 cancer survivors. Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 4952–4963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florido, R.; Daya, N.R.; Ndumele, C.E.; Koton, S.; Russell, S.D.; Prizment, A.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Matsushita, K.; Mok, Y.; Felix, A.S.; et al. Cardiovascular Disease Risk Among Cancer Survivors: The Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC) Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 80, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Han, H.S.; Lee, H.D.; Yang, J.; Jeong, J.; Choi, M.K.; Kwon, J.; Jeon, H.-J.; Oh, T.-K.; Lee, K.H.; et al. A pilot study evaluating steroid-induced diabetes after antiemetic dexamethasone therapy in chemotherapy-treated cancer patients. Cancer Res. Treat. 2016, 48, 1429–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunello, A.; Kapoor, R.; Extermann, M. Hyperglycemia during chemotherapy for hematologic and solid tumors is correlated with increased toxicity. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. Cancer Clin. Trials 2011, 34, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Wang, H.; Tang, Y.; Yan, J.; Cao, L.; Chen, Z.; Shao, Z.; Mei, Z.; Jiang, Z. Increased risk of diabetes in cancer survivors: A pooled analysis of 13 population-based cohort studies. ESMO Open 2021, 6, 100218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylow, L.; Grand, M.K.; von Heymann, A.; Persson, F.; Siersma, V.; Kriegbaum, M.; Lykkegaard Andersen, C.; Johansen, C. Incidence of New-Onset Type 2 Diabetes After Cancer: A Danish Cohort Study. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, e105–e106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Bonomo, R.A. Infections in Cancer Patients. In Oncology Critical Care; InTechOpen: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.K.; Liu, C.; Dadwal, S.S. Infectious Disease Complications in Patients with Cancer. Crit. Care Clin. 2021, 37, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS). Guidelines v.13.0. 2025. Available online: https://eacs.sanfordguide.com/en/eacs-part2/cancer/cancer-treatment-monitoring (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Goyal, G.; Enogela, E.M.; Burkholder, G.A.; Kitahata, M.M.; Crane, H.M.; Eulo, V.; Achenbach, C.J.; Farel, C.E.; Hunt, P.W.; Jacobson, J.M.; et al. Burden of Chronic Health Conditions Among People With HIV and Common Non-AIDS-Defining Cancers. JNCCN J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2025, 23, e257018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friis-Møller, N.; Weber, R.; Reiss, P.; Thiébaut, R.; Kirk, O.; D’Arminio Monforte, A.; Pradier, C.; Morfeldt, L.; Mateu, S.; Law, M.; et al. Cardiovascular disease risk factors in HIV patients—Association with antiretroviral therapy. Results from the DAD study. AIDS 2003, 17, 1179–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The RESPOND Study Group. How to RESPOND to modern challenges for people living with HIV: A profile for a new cohort consortium. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D:A:D Study Webpage. CHIP. Manual of Operations MOOP Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs. 2013. [Cited 2025 Jun 12]. Available online: https://chip.dk/Research/Studies/DAD/Study-Documents (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- RESPOND Study Webpage. CHIP CC. RESPOND. Manual of Operations (MOOP) for Clinical Events. 2024. [Cited 2025 Jun 12]. Available online: https://chip.dk/Research/Studies/RESPOND/Study-documents (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- D:A:D Study Webpage. D:A:D Cause of Death Form (CoDe). 2013. Available online: https://chip.dk/research-areas/cohorts/studies-and-projects/completed-studies-and-projects/dad/study-documents/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Castro, K.G.; Ward, J.W.; Slutsker, L.; Buehler, H.J. Appendix C 1993 Revised Classification System For HIV Infection and Expanded AIDS Surveillance Case Definition For Adolescents and Adults. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK573029/1993; (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Trickey, A.; May, M.T.; Gill, M.; Grabar, S.; Vehreschild, J.; Wit, F.W.N.M.; Bonnet, F.; Cavassini, M.; Abgrall, S.; Berenguer, J.; et al. Cause-specific mortality after diagnosis of cancer among HIV-positive patients: A collaborative analysis of cohort studies. Int. J. Cancer 2020, 146, 3134–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano, A.; Svedman, C.; Hofmarcher, T.; Wilking, N. Comparator Report on Cancer in Europe 2025—Disease Burden, Costs and Access to Medicines and Molecular Diagnostisc. 2025. Available online: https://www.efpia.eu/media/nbbbsbhp/ihe-comparator-report-on-cancer-in-europe-2025.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Lee, J.M.; Suh, H.-W.; Lee, H.-J.; Choi, M.; Kim, J.S.; Lee, K.; Kim, S.-H.; Sohn, J.-W.; Yoon, H.J.; Paek, Y.-J.; et al. Impact of Quitting Smoking at Diagnosis on Overall Survival in Lung Cancer Patients: A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2025, 17, 3623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, J.R.; Qaqish, N.; Stoddard, G.; Jridi, A.; Anderson, P.S.; Woods, L.; Newman, A.; Carter, M.R.; Ellessy, R.; Chamberlin, J.; et al. Non-small cell lung cancer in ever-smokers vs never-smokers. BMC Med. 2025, 23, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Jiang, G.; Wang, C.; Xun, L.; Shen, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Q.; Xie, M.; Xue, X.; et al. Comparative study of lung cancer between smokers and nonsmokers: A real-world study based on the whole population from Tianjin City, China. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2024, 22, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubin, S.; Griffin, D. Lung Cancer in Non-Smokers. Mo. Med. 2020, 117, 375–378. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, V.J.; Grimes, D.; Armstrong, T.; LoBiondo-Wood, G. Management of steroid-induced hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients with cancer: A review. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2014, 41, e355–e365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renehan, A.G.; Tyson, M.; Egger, M.; Heller, R.F.; Zwahlen, M. Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet 2008, 371, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Siegel, R.L.; Rosenberg, P.S.; Jemal, A. Emerging cancer trends among young adults in the USA: Analysis of a population-based cancer registry. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e137–e147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfister, N.T.; Cao, Y.; Schlafstein, A.J.; Switchenko, J.; Patel, P.R.; McDonald, M.W.; Tian, S.; Landry, J.C.; Alese, O.B.; Gunthel, C.; et al. Factors Affecting Clinical Outcomes Among Patients Infected With HIV and Anal Cancer Treated With Modern Definitive Chemotherapy and Radiation Therapy. Adv. Radiat. Oncol. 2023, 8, 101155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palefsky, J.M.; Lee, J.Y.; Jay, N.; Goldstone, S.E.; Darragh, T.M.; Dunlevy, H.A.; Rosa-Cunha, I.; Arons, A.; Pugliese, J.C.; Vena, D.; et al. Treatment of Anal High-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions to Prevent Anal Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 2273–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achenbach, C.J.; Cole, S.R.; Kitahata, M.M.; Casper, C.; Willig, J.H.; Mugavero, M.J.; Saag, M.S. Mortality after cancer diagnosis in HIV-infected individuals treated with antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2011, 25, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calkins, K.L.; Chander, G.; Joshu, C.E.; Visvanathan, K.; Fojo, A.T.; Lesko, C.R.; Moore, R.D.; Lau, B. Immune Status and Associated Mortality after Cancer Treatment among Individuals with HIV in the Antiretroviral Therapy Era. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helleberg, M.; Kronborg, G.; Larsen, C.S.; Pedersen, G.; Pedersen, C.; Obel, N.; Gerstoft, J. CD4 decline is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and death in virally suppressed patients with HIV. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 57, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.M.; Ryom, L.; Sabin, C.A.; Greenberg, L.; Cavassini, M.; Egle, A.; Duvivier, C.; Wit, F.; Mussini, C.; d’Arminio Monforte, A.; et al. Risk of Cancer in People with Human Immunodeficiency Virus Experiencing Varying Degrees of Immune Recovery With Sustained Virological Suppression on Antiretroviral Treatment for More Than 2 Years: An International, Multicenter, Observational Cohort. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2025, ciaf248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timiryasova, A.; Greenberg, L.; Domingo, P.; Tarr, P.E.; Egle, A.; Martin, C.; Mussini, C.; Witt, F.; Cingolani, A.; Lehmann, C.; et al. CD4 Cell count trends after common cancers in people with HIV: A multicohort collaboration. In Proceedings of the Nordic HIV and Virology Conference, Poster Presentation, Stockholm, Sweden, 24–26 September 2025; Available online: https://hivnordic.se/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/P4_RESPOND_Poster_CD4_trends_NordicHIV_23.09.2025.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).