Prediction of Lymphovascular Invasion in Early–Stage Lung Adenocarcinoma Using Artificial Intelligence–Based Radiomics

Simple Summary

Abstract

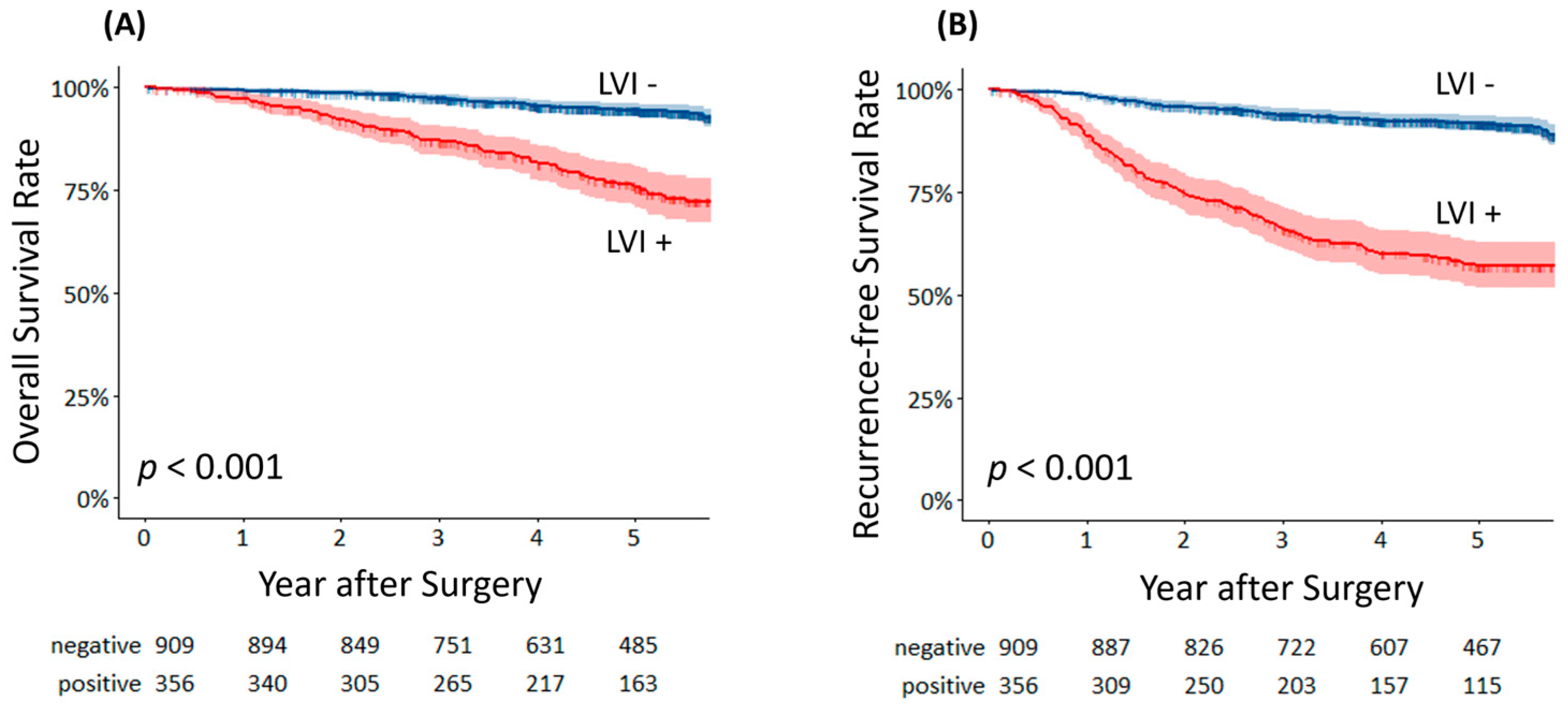

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Statement

2.2. Patients

2.3. Radiological Evaluation of Primary Tumor

2.4. Radiomics and AI Imaging Analysis

2.5. AI Architecture for Nodule Segmentation and Feature Extraction

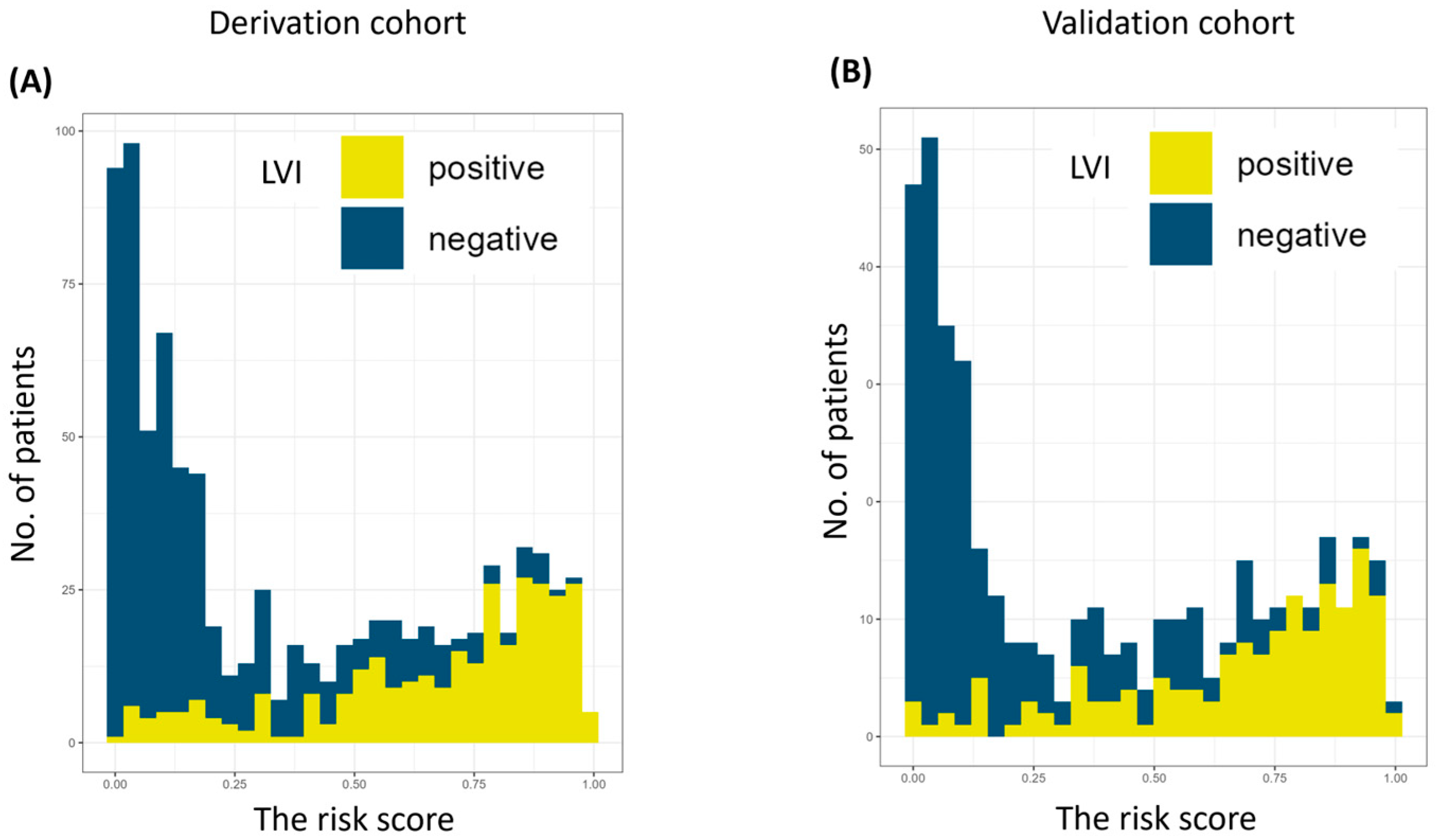

2.6. The Risk Score for LVI

2.7. Histopathology

2.8. Isolation of EVs and Measurement of the miR–30d Level

2.9. Statistics

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | artificial intelligence |

| AUC | area under the curve |

| CT | computed tomography |

| EVs | extracellular vesicles |

| LVI | lymphovascular invasion |

| miRNA | microRNA |

| NSCLC | non–small cell lung cancer |

| OS | overall survival |

| RFS | recurrent–free survival |

| ROC | receiver operating characteristic |

References

- Higgins, K.A.; Chino, J.P.; Ready, N.; D’Amico, T.A.; Berry, M.F.; Sporn, T.; Boyd, J.; Kelsey, C.R. Lymphovascular invasion in non–small–cell lung cancer: Implications for staging and adjuvant therapy. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2012, 7, 1141–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, S.; Kwak, Y.; Lee, S.; Jo, I.; Park, J.; Kim, K.; Lee, K.; Kim, T. Lymphovascular Invasion Increases the Risk of Nodal and Distant Recurrence in Node–Negative Stage I–II A Non–Small–Cell Lung Cancer. Oncology 2018, 95, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimada, Y.; Ishii, G.; Hishida, T.; Yoshida, J.; Nishimura, M.; Nagai, K. Extratumoral vascular invasion is a significant prognostic indicator and a predicting factor of distant metastasis in non–small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2010, 5, 970–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Jin, Y.; Rui, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, C.; Liu, S.; Song, B. Computed tomography–based radiomics for predicting lymphovascular invasion in rectal cancer. Eur. J. Radiol. 2022, 146, 110065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, M.; Wang, G.; Yang, L.; Ma, C.; Wang, M.; Yue, M.; Cong, M.; Ren, J.; Shi, G. Contrast–Enhanced CT–Based Radiomics Analysis in Predicting Lymphovascular Invasion in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 644165. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Pu, H.; Li, H. Dual–phase contrast–enhanced CT–based intratumoral and peritumoral radiomics for preoperative prediction of lymphovascular invasion in gastric cancer. BMC Med. Imaging 2025, 25, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, B.; Lv, Y.; Peng, C.; Wei, Z.; Xv, Q.; Lv, F.; Jiang, Q.; Liu, H.; Li, F.; Xv, Y.; et al. Deep learning feature–based model for predicting lymphovascular invasion in urothelial carcinoma of bladder using CT images. Insights Imaging 2025, 16, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Cui, J.; Qiu, L. Imaging–Based AI for Predicting Lymphovascular Space Invasion in Cervical Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta–Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e71091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Fan, X.; Lin, S.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Zuo, Z.; Zeng, Y. Assessment of Lymphovascular Invasion in Breast Cancer Using a Combined MRIMorphological Features Radiomics Deep Learning Approach Based on Dynamic Contrast–Enhanced MRI. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2024, 59, 2238–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suaiti, L.; Sullivan, T.B.; Rieger–Christ, K.M.; Servais, E.L.; Suzuki, K.; Burks, E.J. Vascular Invasion Predicts Recurrence in Stage IA2–IB Lung Adenocarcinoma but not Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Clin. Lung Cancer 2023, 24, e126–e133. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, T.; Ishikawa, K.; Aragaki, M.; Sato, M.; Okamoto, K.; Ishibashi, T.; Kaji, M. Angiolymphatic invasion exerts a strong impact on surgical outcomes for stage I lung adenocarcinoma, but not non–adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer 2012, 77, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saijo, T.; Ishii, G.; Ochiai, A.; Hasebe, T.; Yoshida, J.; Nishimura, M.; Nagai, K. Evaluation of extratumoral lymphatic permeation in non–small cell lung cancer as a means of predicting outcome. Lung Cancer 2007, 55, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Sullivan, T.B.; Rieger–Christ, K.M.; Yambayev, I.; Zhao, Q.; Higgins, S.E.; Yilmaz, O.H.; Sultan, L.; Servais, E.L.; Suzuki, K.; et al. Vascular invasion predicts the subgroup of lung adenocarcinomas ≤2.0 cm at risk of poor outcome treated by wedge resection compared to lobectomy. JTCVS Open 2023, 16, 938–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usui, S.; Minami, Y.; Shiozawa, T.; Iyama, S.; Satomi, K.; Sakashita, S.; Sato, Y.; Noguchi, M. Differences in the prognostic implications of vascular invasion between lung adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Lung Cancer 2013, 82, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, N.; Doai, M.; Usuda, K.; Uramoto, H.; Tonami, H. Non–small cell lung cancer: Whole–lesion histogram analysis of the apparent diffusion coefficient for assessment of tumor grade, lymphovascular invasion and pleural invasion. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, Y.; Kudo, Y.; Maehara, S.; Amemiya, R.; Masuno, R.; Park, J.; Ikeda, N. Radiomics with Artificial Intelligence for the Prediction of Early Recurrence in Patients with Clinical Stage IA Lung Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 29, 8185–8193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wei, H.; Fu, F.; Wei, W.; Wu, Y.; Bai, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, M. Preoperative prediction of lymphovascular invasion of colorectal cancer by radiomics based on 18F–FDG PET–CT and clinical factors. Front. Radiol. 2023, 3, 1212382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceachi, B.; Cioplea, M.; Mustatea, P.; Gerald Dcruz, J.; Zurac, S.; Cauni, V.; Popp, C.; Mogodici, C.; Sticlaru, L.; Cioroianu, A.; et al. A New Method of Artificial–Intelligence–Based Automatic Identification of Lymphovascular Invasion in Urothelial Carcinomas. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Wang, H.; Ye, Z. Artificial intelligence applications in computed tomography in gastric cancer: A narrative review. Transl. Cancer Res. 2023, 12, 2379–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wang, P.; Ding, R.; Ma, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, L. Preoperative prediction value of 2.5D deep learning model based on contrast–enhanced CT for lymphovascular invasion of gastric cancer. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25646. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shimada, Y.; Yoshioka, Y.; Kudo, Y.; Mimae, T.; Miyata, Y.; Adachi, H.; Ito, H.; Okada, M.; Ohira, T.; Matsubayashi, J.; et al. Extracellular vesicle–associated microRNA signatures related to lymphovascular invasion in early–stage lung adenocarcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4823. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Costa–Silva, B.; Aiello, N.M.; Ocean, A.J.; Singh, S.; Zhang, H.; Thakur, B.K.; Becker, A.; Hoshino, A.; Mark, M.T.; Molina, H.; et al. Pancreatic cancer exosomes initiate pre–metastatic niche formation in the liver. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015, 17, 816–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteside, T.L. Exosomes carrying immunoinhibitory proteins and their role in cancer. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2017, 189, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohama, I.; Kosaka, N.; Chikuda, H.; Ochiya, T. An Insight into the Roles of MicroRNAs and Exosomes in Sarcoma. Cancers 2019, 11, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Li, L.; Li, M.; Guo, C.; Yao, J.; Mi, S. Exosome and exosomal microRNA: Trafficking, sorting, and function. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2015, 13, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, A.; Kim, H.S.; Bojmar, L.; Gyan, K.E.; Cioffi, M.; Hernandez, J.; Zambirinis, C.P.; Rodrigues, G.; Molina, H.; Heissel, S.; et al. Extracellular Vesicle and Particle Biomarkers Define Multiple Human Cancers. Cell 2020, 182, 1044–1061 e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, S.; Valderas, J.M.; Doran, T.; Perera, R.; Kontopantelis, E. Analysing indicators of performance, satisfaction, or safety using empirical logit transformation. BMJ 2016, 352, i1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; She, Y.; Wang, T.; Xie, H.; Li, J.; Jiang, G.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xie, D.; Chen, C. Radiomics–based prediction for tumour spread through air spaces in stage I lung adenocarcinoma using machine learning. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2020, 58, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Y.; Yuan, M.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Y.D.; Li, H.; Yu, T.F. Radiomics Approach to Prediction of Occult Mediastinal Lymph Node Metastasis of Lung Adenocarcinoma. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2018, 211, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Pan, X.; Liu, H.; Gao, D.; He, J.; Liang, W.; Guan, Y. A new approach to predict lymph node metastasis in solid lung adenocarcinoma: A radiomics nomogram. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, S807–S819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thawani, R.; McLane, M.; Beig, N.; Ghose, S.; Prasanna, P.; Velcheti, V.; Madabhushi, A. Radiomics and radiogenomics in lung cancer: A review for the clinician. Lung Cancer 2018, 115, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Kim, J.; Balagurunathan, Y.; Hawkins, S.; Stringfield, O.; Schabath, M.B.; Li, Q.; Qu, F.; Liu, S.; Garcia, A.L.; et al. Prediction of pathological nodal involvement by CT–based Radiomic features of the primary tumor in patients with clinically node–negative peripheral lung adenocarcinomas. Med. Phys. 2018, 45, 2518–2526. [Google Scholar]

- Cong, M.; Feng, H.; Ren, J.L.; Xu, Q.; Cong, L.; Hou, Z.; Wang, Y.Y.; Shi, G. Development of a predictive radiomics model for lymph node metastases in pre–surgical CT–based stage IA non–small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2020, 139, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takehana, K.; Sakamoto, R.; Fujimoto, K.; Matsuo, Y.; Nakajima, N.; Yoshizawa, A.; Menju, T.; Nakamura, M.; Yamada, R.; Mizowaki, T.; et al. Peritumoral radiomics features on preoperative thin–slice CT images can predict the spread through air spaces of lung adenocarcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, Y.J.; Han, K.; Kwon, Y.; Kim, H.; Lee, S.; Hwang, S.H.; Kim, M.H.; Shin, H.J.; Lee, C.Y.; Shim, H.S. Computed Tomography Radiomics for Preoperative Prediction of Spread Through Air Spaces in the Early Stage of Surgically Resected Lung Adenocarcinomas. Yonsei Med. J. 2024, 65, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, W.; Li, J.; Xing, L.; Sun, X. (18)F–FDG PET/CT radiomics for prediction of lymphovascular invasion in patients with early stage non–small cell lung cancer. Front. Oncol. 2023, 3, 1185808. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, P.; Yang, G.; Wang, N.; Yan, L.; Miao, W.; Duan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gong, A.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, J.; et al. Additional value of metabolic parameters to PET/CT–based radiomics nomogram in predicting lymphovascular invasion and outcome in lung adenocarcinoma. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2021, 48, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Shao, J.; Xue, T.; Peng, H.; Li, M.; Duan, S.; Feng, F. Intratumoral and peritumoral radiomics nomograms for the preoperative prediction of lymphovascular invasion and overall survival in non–small cell lung cancer. Eur. Radiol. 2023, 33, 947–958. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, M.; Zhao, C.; Huang, H.; Zhao, X.; Yang, S.; He, X.; Li, K. The clinical value of predicting lymphovascular invasion in patients with invasive lung adenocarcinoma based on the intratumoral and peritumoral CT radiomics models. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Derivation Cohort n = 840 (%) | Validation Cohort n = 425 (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (median) | 33–88 (68) | 23–87 (68) | 0.90 |

| Sex, male | 391 (47) | 188 (44) | 0.44 |

| Any smoking history | 442 (53) | 225 (53) | 0.95 |

| Comorbidities, present | 433 (52) | 229 (54) | 0.44 |

| Whole tumor size on CT, cm (mean ± SD) | 0.50–8.40 (2.20 ± 0.87) | 0.50–5.00 (2.21 ± 0.88) | 0.87 |

| Solid tumor size on CT, cm (mean ± SD) | 0.0–4.00 (1.54 ± 1.01) | 0.0–4.00 (1.60 ± 1.06) | 0.31 |

| Clinical stage | 0.12 | ||

| 0 | 75 (9) | 28 (7) | |

| IA1 | 219 (26) | 128 (30) | |

| IA2 | 271 (32) | 123 (29) | |

| IA3 | 145 (17) | 65 (15) | |

| IB | 130 (15) | 81 (19) | |

| Surgical procedure | 0.32 | ||

| Lobectomy | 729 (87) | 376 (88) | |

| Segmentectomy | 75 (9) | 38 (9) | |

| Wedge resection | 36 (4) | 11 (3) | |

| Pathological stage | 0.041 | ||

| 0 | 13 (2) | 8 (2) | |

| IA | 571 (68) | 295 (69) | |

| IB | 162 (19) | 58 (14) | |

| II | 52 (6) | 30 (7) | |

| III–IV | 42 (5) | 34 (8) | |

| Lymph–node status | 0.038 | ||

| N0 | 762 (91) | 368 (87) | |

| N1 | 42 (5) | 27 (6) | |

| N2 | 34 (4) | 30 (7) | |

| Lymphovascular invasion, Positive | 309 (37) | 158 (37) | 0.90 |

| Blood vessel invasion, Positive | 235 (37) | 121 (28) | 0.90 |

| Lymphatic invasion, Positive | 254 (30) | 140 (33) | 0.90 |

| Collected serum extracellular vesicles | 31 (4) | 16 (4) | 1.00 |

| Risk Score | AUC | Sens. (%) | Spec. (%) | Accu. (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVI | ≤0.397 | >0.397 | |||||||

| Derivation | Negative Positive | 443 | 88 | 0.899 | 84.8 | 83.7 | 83.9 | 74.9 | 90.4 |

| 47 | 262 | ||||||||

| Validation | Negative Positive | 212 | 55 | 0.882 | 82.3 | 79.4 | 80.5 | 70.3 | 88.3 |

| 28 | 130 | ||||||||

| Study | Target Feature | Sample Size | Imaging Modality | AI/Radiomics Method | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen et al. (2020) [28] | STAS | 233 | CT | Naïve Bayes model | AUC 0.63–0.69 |

| Takehana et al. (2022) [34] | STAS | 339 | CT | Peritumoral features | AUC 0.70–0.76 |

| Suh et al. (2024) [35] | STAS | 520 | CT | Radiomics score | AUC 0.815 |

| Cong et al. (2020) [33] | LNM | 649 | CT | LASSO | AUC 0.851–0.898 |

| Shimada et al. (2022) [16] | recurrence | 642 | CT | Modified U–Net | AUC 0.707–0.71 |

| Wang et al. (2023) [36] | LVI | 148 | PET/CT | LASSO | AUC 0.773–0.774 |

| Nie et al. (2021) [37] | LVI | 272 | PET/CT | Radiomics score | AUC 0.796–0.851 |

| Chen et al. (2023) [38] | LVI | 240 | CT | Radiomics score | AUC 0.66–0.89 |

| Lin et al. (2025) [39] | LVI | 384 | CT | Radiomics score | AUC 0.75–0.83 |

| Present study | LVI | 1265 | CT | Modified U–Net | AUC 0.882–0.899 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shimada, Y.; Harada, K.; Kudo, Y.; Park, J.; Matsubayashi, J.; Taguri, M.; Ikeda, N. Prediction of Lymphovascular Invasion in Early–Stage Lung Adenocarcinoma Using Artificial Intelligence–Based Radiomics. Cancers 2025, 17, 3998. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243998

Shimada Y, Harada K, Kudo Y, Park J, Matsubayashi J, Taguri M, Ikeda N. Prediction of Lymphovascular Invasion in Early–Stage Lung Adenocarcinoma Using Artificial Intelligence–Based Radiomics. Cancers. 2025; 17(24):3998. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243998

Chicago/Turabian StyleShimada, Yoshihisa, Kazuharu Harada, Yujin Kudo, Jinho Park, Jun Matsubayashi, Masataka Taguri, and Norihiko Ikeda. 2025. "Prediction of Lymphovascular Invasion in Early–Stage Lung Adenocarcinoma Using Artificial Intelligence–Based Radiomics" Cancers 17, no. 24: 3998. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243998

APA StyleShimada, Y., Harada, K., Kudo, Y., Park, J., Matsubayashi, J., Taguri, M., & Ikeda, N. (2025). Prediction of Lymphovascular Invasion in Early–Stage Lung Adenocarcinoma Using Artificial Intelligence–Based Radiomics. Cancers, 17(24), 3998. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243998