Simple Summary

Oligometastatic breast cancer refers to an intermediate state between localized and disseminated disease. Recent advances in surgery, radiotherapy, and systemic treatments are improving outcomes for these patients. However, choosing the right treatment can be challenging and must consider the patient’s overall condition and life expectancy. This article provides a comprehensive review of the literature to determine the optimal approach to the management of musculoskeletal oligometastatic disease in breast cancer. Indications for orthopedic surgery include pathologic fractures, neurologic compromise, and a long-expected survival. Favorable prognostic factors include solitary bone metastasis, preserved performance status, adequate surgical margins, absence of pathologic fracture, metachronous metastases, and ER-positivity status. As oligometastatic breast cancer still lacks standardized treatment strategies, further research is needed to develop treatment protocols suitable for broader clinical application.

Abstract

Oligometastatic breast cancer represents an intermediate state between localized and disseminated disease with reasonable potential for clinical cure. Advancements in surgery, radiotherapy, and systemic therapy have improved prognosis. Due to the high prevalence of bone metastases, an increasing number of studies are evaluating new treatment strategies for oligometastatic bone disease. The decision to perform skeletal surgery is complex and depends on optimal patient selection. Major criteria include impending or pathologic long bone fractures, severe neurologic compromise, and an expected survival of over 3 months. Factors associated with improved survival include solitary bone metastases, preserved performance status, adequate surgical margins, absence of pathologic fracture, metachronous metastases, and ER-positivity status. Radiotherapy, especially SBRT, offers effective local control and palliation. Interventional radiology techniques such as percutaneous thermal ablation have also been described as potential treatment alternatives, particularly for fragile patients. Systemic treatment varies according to the tumor subtype. For HR+ and HER2 subtypes, a combination of endocrine therapy with CDK4/6 inhibitors may be considered. HER2+ patients are often treated with HER2-targeted therapies combined with chemotherapy. For triple-negative breast cancer, chemotherapy is the primary treatment. Bone-modifying agents are also recommended to maintain bone strength, prevent skeletal-related events, and reduce the need for additional interventions. Skeletal muscle metastases in breast cancer patients are rare and typically indicate advanced disease with poor prognosis. Treatment options include chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgical excision, but should be tailored to the patient’s clinical condition and prognosis.

1. Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common malignant tumor among women, comprising 24% of all malignancies in this population, with a 5-year survival rate of 32% for distant-stage disease [1,2]. A major factor contributing to the high mortality rate is the substantial risk of metastases, with bones being the most frequent site of metastatic spread [3]. Approximately 70% of people who die from breast cancer have evidence of bone metastatic disease at autopsy [4]. Conversely, skeletal muscle involvement is uncommon, and the literature regarding its prevalence is scarce [5]. Breast cancer subtypes are associated with different patterns of metastatic spread. For instance, HR+ subtypes are most likely to metastasize to the bone, while HER2+ subtypes have higher affinity for the brain, liver, and lungs. Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) has increased affinity for the lungs and brain [6,7].

Oligometastatic disease (OMD) is defined as the presence of no more than five metastases involving up to three organs, and is considered an intermediate stage between localized and disseminated disease [8,9]. The exact prevalence of oligometastatic breast cancer (OMBC) is unknown, but has been reported to be as high as 20% [10]. Advances in imaging techniques and locoregional treatments have made OMD increasingly recognizable, and growing evidence suggests that it is a distinct subgroup with a better long-term prognosis than metastatic breast cancer, offering a potential for clinical cure [11]. Notably, Milano et al. reported a 6-year overall survival (OS) of 47% among patients with OMBC treated with stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) [12].

However, the outcomes of patients treated with curative intent are heterogeneous, indicating that OMD represents a spectrum of disease states with variable prognoses. To harmonize diagnostic criteria, the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) and the European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology (ESTRO) have proposed a comprehensive classification system that conceptualizes OMD as an umbrella term encompassing all forms of limited metastatic disease according to biological and clinical characteristics [9,13]. Within this framework, genuine OMD refers to limited metastatic disease occurring without history of polymetastatic disease, whereas induced OMD describes cases with previous history of polymetastatic disease. Genuine OMD can be subclassified in de novo OMD, which refers to patients with first-time diagnosis of OMD, and repeat OMD, which occurs in patients with a previous history of OMD. Further subclassifications include oligorecurrence, oligoprogression, and oligopersistence, depending on whether the disease is detected during a treatment-free interval or active systemic therapy, and whether lesions are stable or progressing on current imaging [9].

Identifying these OMD states is clinically relevant, as they carry distinct prognostic implications and can guide individualized treatment strategies. In breast cancer, patients with de novo OMD generally show a more favorable prognosis and may benefit from aggressive local therapies such as surgery or SBRT with curative intent [14,15,16]. Oligorecurrent disease represents a more indolent tumor biology but is often associated with poorer survival outcomes due to limited curative locoregional treatment options. Selvarajan et al. reported a median OS of 74 months in de novo OMD compared to 22.7 months in oligorecurrent cases [17]. Oligoprogressive disease refers to acquired resistance to systemic treatment and is associated with poor survival outcomes [9]. In such cases, growing evidence supports the role of metastasis-directed therapy in restoring systemic treatment sensitivity and improving overall prognosis [18,19]. Recognizing these subtypes allows clinicians to tailor management strategies and to identify patients most likely to benefit from curative or disease-stabilizing approaches.

Among OMD presentations, bone involvement represents one of the most frequent and clinically significant patterns in breast cancer. Although metastatic bone disease is a heterogeneous entity, oligometastatic bone disease (OMBD) in breast cancer has better survival outcomes than generalized metastases [20]. Improved OS in patients with limited metastatic burden, along with advancements in surgery, radiotherapy, and systemic therapy, supports the multimodal approach recommended in the OMBC guidelines [21]. Historically, studies supporting SBRT have been largely retrospective or prospective non-randomized single-arm studies [22,23,24,25], and the role of surgery has been reported mainly in retrospective studies [22]. As aggressive metastasis-targeted therapies become more common, the growing number of randomized controlled trials on OMBD warrants further discussion. Our study aimed to provide a comprehensive review of the literature and ongoing trials to determine the optimal approach for managing musculoskeletal oligometastatic disease in breast cancer.

2. Overview of Treatment Options

The treatment of OMBD in breast cancer requires a multidisciplinary approach. Criteria for treatment selection should include tumor characteristics (location, size, histology, biological status), patient profile (health status, comorbidities, oncologic prognosis), number of metastatic sites, and time interval between diagnosis and development of metastases [26,27,28]. Due to the higher survival rate in OMD, the most aggressive treatment of this entity aims at local control, improved survival, progression-free survival (PFS), and symptom relief [28,29].

Currently, treatment options include surgery, radiotherapy, and systemic treatment (chemotherapy, targeted therapy, hormone therapy, immunotherapy, and bone-modifying agents) [27,30,31]. In most cases, a combination of local and systemic treatment is used to achieve good long-term effects [32,33].

3. Surgery

In the setting of bone metastases, surgery has been primarily reserved for vertebral metastases with spinal cord compression and for pathologic fractures of long bones [34]. Orthopedic treatment aims to decrease pain, increase mobility and functionality, achieve local tumor control, and prevent or stabilize pathologic fractures. The indication for surgical intervention in these cases is complex and varies according to the different management protocols of each institution. Surgical removal of metastatic bone tumors may not be necessary in some cases of breast cancer that respond to radiation or systemic therapy [35]. Ehne et al. consider the following criteria for patient selection that maximize the benefits of surgical intervention in patients with metastatic bone disease [34]: (I) presence of pathologic fracture or impending fracture in long bones, (II) severe neurologic compromise due to spinal metastatic disease, and (III) expected patient survival greater than three months.

Several algorithms addressing clinical staging, imaging, survival, and fracture risk prediction have been developed and are used as guides for making surgical decisions in people with metastatic bone disease [36,37,38,39]. However, heterogeneity in patients and the unpredictable nature of the tumor hinder their clinical application [40].

The axial skeleton is the most common site of metastasis in breast cancer, followed by long bones [41,42,43]. The site of metastasis is a key consideration in choosing the optimal surgical approach to ensure better survival and minimize the risk of recurrence. In solitary long bone metastases, resection followed by endoprosthetic reconstruction remains a generally accepted surgical option [34,44,45]. In axial skeleton metastases, radical tumor resection with reconstruction may be feasible, particularly in spinal lesions restricted to a single area, where the potential benefits may outweigh the surgical risks [46,47]. However, management strategies should also consider the number of metastases, the functional status of the patient and the specific anatomical location.

Despite retrospective studies indicating promising results for metastasectomy in OMD, the lack of randomized clinical trials leaves the true efficacy of surgical intervention unclear. Generally, candidates for bone metastasectomy should present with single or oligometastatic lesions and a life expectancy greater than 12 months [34,40,48,49]. However, there is currently no consensus regarding the precise indications for performing metastasectomy in patients with oligometastatic breast cancer involving the bone.

3.1. Surgical Treatment Options

Surgical options for appendicular bone metastases include intramedullary nailing (IMN), open reduction with internal fixation (ORIF), and endoprosthetic reconstruction (EPR) [40,50]. Less invasive procedures like IMN are typically preferred for patients with limited life expectancy, while en bloc resection and reconstruction with durable implants, such as prostheses, are recommended for those with longer expected survival [34,51].

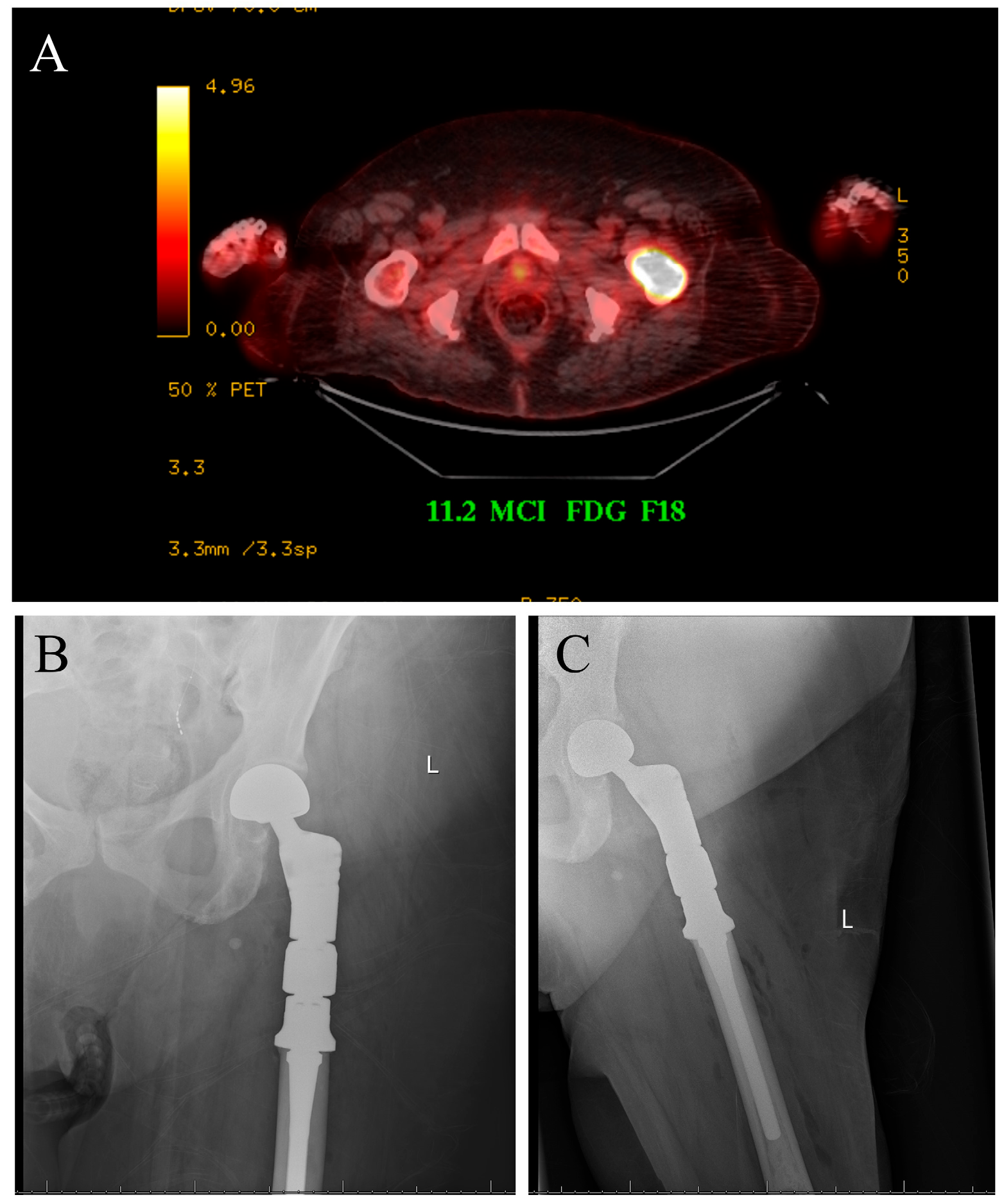

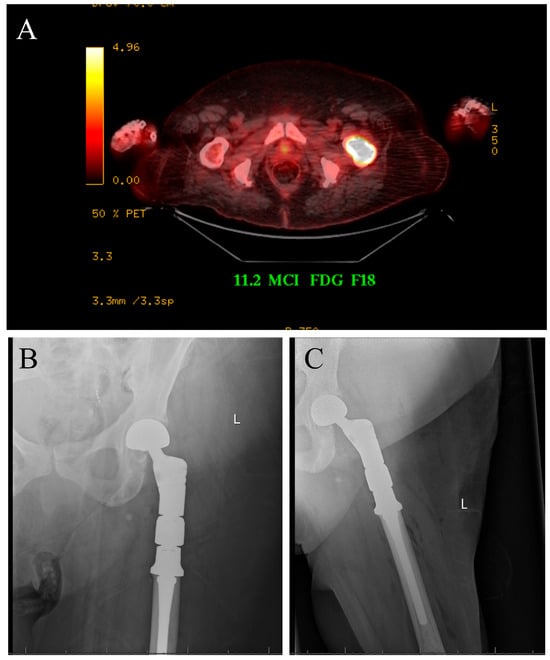

The case displayed in Figure 1 illustrates the surgical management of a solitary bone lesion on the hip by the senior author of this article.

Figure 1.

Seventy-five-year-old female with newly diagnosed breast cancer and pain with weight-bearing on the left hip. (A) Axial cut PET-CT showing solitary bone lesion biopsy proven breast cancer. (B,C) Patient underwent resection of left proximal femur and reconstruction with proximal femur megaprosthesis.

Surgical treatment of impending or actual pathologic fractures due to metastases in long bones generally involves IMN due to the short operative time and early weight-bearing [49,50,51,52]. Lesions involving the femoral head or neck are typically treated with hip arthroplasty or EPR, as they offer a durable construct that allows for immediate weight-bearing [52,53,54]. In the peritrochanteric region, either internal fixation or arthroplasty is suitable [55], while PMMA augmentation is often used in the distal femur for added strength [34]. Humeral diaphyseal lesions are generally managed with IMN and are often reinforced with PMMA cement [56,57,58,59]. Metaphyseal humeral lesions may be treated with ORIF, which has shown adequate local tumor control and lower recurrence rates [60]. Proximal humeral lesions may require endoprosthetic replacement to preserve shoulder stability and function [59,61]. Distal humeral lesions are predominantly managed with plate fixation; however, more extensive resection with elbow reconstruction may be necessary for more complex fractures [62,63,64]. Tibial metastases, though less frequent, are addressed through EPR, IMN, or plate and screws osteosynthesis [65,66,67,68], with amputation reserved for advanced or non-salvageable cases [68,69].

Surgical management of spinal metastases ranges from minimally invasive procedures, such as vertebral augmentation, to more extensive interventions including radical tumor resection and reconstruction [46], with anterior or posterior approaches chosen based on tumor location, patient overall condition, and surgeon expertise [70,71,72,73,74,75]. Sternal metastases may benefit from aggressive resection and reconstruction with grafts or prosthesis implantation [76,77,78]. Surgery of pelvic metastases should also consider the location of the lesion within the bone. Periacetabular lesions often demand complex reconstruction to restore stability and function [79,80,81], while ileum and pubis lesions may not need reconstruction due to limited weight-bearing function [80]. Emerging minimally invasive procedures, such as percutaneous screw fixation or the use of photodynamic nails, are increasingly being used in the management of pelvic metastases, with growing evidence supporting good early functional outcomes, improved patient mobility, and early pain relief [80,82].

Skeletal muscle metastases are rare and very few reports exist on the subject [83,84]. Surgical resection may be helpful in carefully selected patients, such as those with painful lesions, long disease-free intervals, or radiation-resistant tumors [85,86,87,88]. Ultimately, surgical decisions are tailored to patient prognosis, anatomical site, and expected functional benefit.

3.2. Outcomes of Surgery in Oligometastatic Bone Disease in Breast Cancer

The benefits of surgery for bone metastases in breast cancer stem primarily from observational studies (Table 1). The 5-year OS after surgery for solitary bone metastases ranged from 39% to 56%, which is higher than that of metastatic breast cancer overall. However, survival is proportional to the number of lesions and can be as low as 8% in patients with multiple bone metastases [43,48,51]. Survival rates also differ by sociodemographic and economic factors, reflecting variations in tumor subtype prevalence, healthcare access, stage at diagnosis, and metastatic patterns. In a multivariate analysis, Ren et al. reported higher breast cancer–specific mortality among non-Hispanic Black women compared with non-Hispanic White women [89]. Similarly, on a global scale, survival rates vary by region, with poorer outcomes in low- and middle-income countries due to limited access to systemic therapies and specialized care [90].

Table 1.

Outcomes of skeletal surgery in breast cancer patients with bone metastases.

The major issue with most of the available studies is the lack of a proper control group which limits the generalization of the results. Hankins et al. performed a retrospective review of 167 patients with breast cancer and bone metastases who received standard multimodality therapy (chemotherapy, radiotherapy, hormonal therapy, bone-directed therapy, and surgery) [91]. They compared the survival patterns of patients treated with and without surgery and found that non-operated patients had a higher median OS than operated patients, with 139.7 months and 88.9 months, respectively. However, surgically treated patients were more likely to have more aggressive lytic lesions which were often located in weight-bearing bones, this caused greater functional impairment and may have been associated with a lower overall survival. Also, the relatively small sample size and the combination of treatments received by patients limit the ability to identify differences in outcomes based on specific treatment approaches.

3.3. Prognostic Factors Related to Surgery

Several prognostic factors have been reported in the literature to improve survival after surgery in bone metastases. We present some of the most reported ones:

- Solitary bone metastases [26,43,48,51];

- Preserved performance status (Karnofsky score above 70) [95];

- Adequate surgical margins (R0) [48];

- Absence of pathologic fracture [48,92];

- Metachronous metastases [91];

- ER-positivity status [91,96,97].

Some risk factors for poor survival have also been reported (Table 2). Weiss et al. retrospectively reviewed 301 patients with breast cancer after surgical treatment of skeletal metastases [51]. They found age >60 years (HR 1.9, 95% CI 1.3–2.8, p = 0.002) and hemoglobin levels <110 g/L (HR 2.0, 95% CI 1.3–3, p = 0.001) as factors associated with increased risk of death, whereas impending fractures decreased postoperative risk of death (HR 0.4, 95% CI 0.2–1.0, p = 0.04). 14% of breast cancer patients who underwent surgical intervention for skeletal metastases required re-operation. The most common reasons were implant failure (n = 12), periprosthetic or stress fracture (n = 11), and local tumor progression (n = 8). However, these results are based on patients with various types of metastases (single skeletal, multiple skeletal, or generalized metastases) and may differ from those of patients with oligometastases.

Table 2.

Risk factors for poor survival after skeletal surgery in breast cancer patients with bone metastases.

Time of detection of metastases has also been recognized as an important predictor of survival, with synchronous and metachronous metastases representing two distinct patterns of metastases progression. Synchronous metastases are defined as metastases detected at the time of breast cancer diagnosis or within a maximum of 6 months from it, while metachronous metastases are identified after 6 months of initial breast cancer diagnosis [9]. Although no consensus exists in the literature regarding the time interval between the primary tumor diagnosis and the development of OMD for defining metachronous disease, a period of six months is frequently used. Hankins et al. reported median OS of 58.3 and 139.7 months for patients with synchronous and metachronous bone metastases, respectively [91]. Multivariable analysis confirmed that synchronous status was associated with inferior OS (HR 2.27, 95% CI 1.36–3.81, p = 0.002). Furthermore, they reported that surgical intervention of breast cancer bone metastases was not associated with a difference in OS in patients with synchronous bone metastases. The median OS of patients with synchronous metastases treated surgically was 58.3 months, compared with 59.9 months in patients with synchronous disease treated nonsurgically. In patients with metachronous metastases, the median OS for those treated surgically was 114.2 months, compared with 175.1 months for those treated nonsurgically. This study suggests that the timing of metastasis appearance is not a useful factor for patient selection for surgical intervention. Instead, decisions should be guided by lesion’s characteristics, location, size, and the patient’s performance status. The major limitation of this study is that it does not differentiate patients with oligometastases and disseminated disease; furthermore, the combination of treatments received by the patients and the retrospective nature of the study make it difficult to generalize the results.

4. Radiotherapy

Ablation therapies have been effective in treating metastases with minimal tumor spread, making them a potential alternative for managing oligometastases. Stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy (SABR) is increasingly being used for OMD because it offers a noninvasive approach that can be administered on an outpatient basis. SABR has also been demonstrated to be both feasible and well-tolerated in managing bone-involved OMBC, providing excellent local control. David et al. conducted a prospective trial involving 15 breast cancer patients with oligometastases who received a single fraction of SABR for all visible sites of disease [100]. They found that none of the patients experienced grade 3 or 4 radiotherapy-related toxicities, and only 27% of patients reported grade 2 toxicities.

Although systemic therapy is the standard of care for patients in a metastatic stage, cases of oligometastases can be treated in a metastasis-directed approach using minimally invasive surgical and ablative techniques, such as stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy or hypofractionated stereotactic radiation (HSRT). Milano et al. found that the 5-year and 10-year OS rates after HSRT were 83% and 75%, respectively, for patients with bone-only oligometastases, compared to 31% and 17%, respectively, for non-bone-only oligometastases [16]. Additionally, they emphasized that tumor burden, which includes both the volume and number of lesions, appears to influence the likelihood of recurrence.

4.1. Ongoing Clinical Trials

Various clinical trials are enrolling patients with OMBC, with radiotherapy being the main local treatment approach (Table 3) [23,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117]. The number of metastases varies across studies, with a median ranging from 3 to 5 metastases. It is important to note that all patients received local ablative radiotherapy for progressing lesions. A major primary endpoint in these trials is the duration before a transition to systemic therapy is needed. Repeated local ablative therapy is usually only considered in the case of new oligoprogressive lesions [100].

Table 3.

Clinical trials of radiation therapy for oligometastatic breast cancer patients.

It is important to highlight that the NRG-BR002 trial, a Phase II/III randomized controlled study, evaluated the addition of metastasis-directed treatments, including SBRT and/or surgical resection, to standard systemic therapy. The trial aimed to assess their impact on PFS and OS in patients with OMBC. However, the study did not demonstrate improvement in either PFS or OS and therefore did not advance to Phase III [106]. These findings underscore the need for further randomized controlled trials and comparative studies to better assess the efficacy and safety of metastasis-directed therapies, particularly SBRT, before such aggressive strategies can be systematically implemented in clinical practice.

4.2. Prognostic Factors Related to Radiotherapy

Some prognostic factors have also been reported in retrospective studies involving radiotherapy. Wijetunga et al. retrospectively reviewed 79 patients who underwent SABR for breast cancer oligometastases [15]. On multivariate analysis, they found that less than 5 years from breast cancer diagnosis to SABR (HR = 4.17, p = 0.003) was associated with shorter OS. Also, having TNBC was associated with worse PFS compared to HR+/HER2− breast cancer (HR = 2.80, p = 0.036).

Furthermore, retrospective studies have shown that prognosis worsens as the number of metastases increases. Steenbruggen et al. evaluated 3447 patients with synchronous metastatic breast cancer and reported that those with up to 3 metastases had an estimated 10-year OS rate of 14.9%, compared to 3.4% for patients with more than 3 metastases [118]. They additionally performed a multivariate analysis of 517 patients with OMBC and found that premenopausal (HR 0.37, p = 0.004) or perimenopausal status (HR 0.48, p = 0.03), along with local therapy of metastases (surgery and/or radiotherapy) (HR 0.57, p = 0.02) were associated with better OS. In contrast, lung metastases (HR 4.83, p < 0.001) and the absence of systemic treatment (HR 8.75, p = 0.002) were associated with worse OS. Although the study did not perform a subgroup analysis for patients with only skeletal metastases, 55.9% of patients included in the study had OMBC to the bone.

Other important predictors for good prognosis after SBRT include biological subtype (hormone receptor positive, HER2 negative), solitary metastasis, bone-only metastasis, and long-metastasis free interval [119]. However, further research with larger sample sizes and proper control groups is required to prove the benefits of SBRT in OMBC and define adequate selection criteria.

5. Interventional Radiology

Patients with OMBC are potentially curable due to very few metastasis sites, with limited potential for further spread. As a result, aggressive treatments aimed at cure, such as interventional radiology, confer chances to prolong survival in this intermediate cancer scenario [120,121]. Percutaneous thermal ablation (PTA) is a minimally invasive technique that may be performed on an outpatient basis targeting metastases in different locations with a relatively shorter time of recovery [122]. PTA encompasses various procedures such as radiofrequency ablation, microwave ablation, and cryotherapy. Barral et al. evaluated 79 patients with breast cancer oligometastases who underwent PTA with curative intent [123]. They reported no postoperative mortality and a morbidity rate of 15% (12 out 79 patients). The OS rates at 1 and 2 years were 98.3 and 95.5%, respectively. Disease-free survival rates at 1 and 2 years were 54.2 and 30.4%, respectively. Additionally, on multivariate analysis, they found that triple-negative histological subtype (HR 2.22, 95% CI 1.13–4.36, p = 0.02) and increased metastasis size (HR 2.43, 95% CI 1.22–4.82, p = 0.011) were associated with poorer disease-free survival following PTA. The study emphasized that PTA is a safe procedure with few and manageable complications, especially when compared to surgical metastasectomy in the oligometastatic setting and is frequently preferred for more fragile patients.

Ridouani et al. conducted a retrospective cohort study of 33 patients who underwent thermal ablation to either eradicate all evident sites of metastases or to achieve local control of metastases [122]. They found a median OS of 70 months and a 5-year OS of 55%, median PFS was 10 months and median time to local progression (TTP) was 11 months. The study also showed that ablation of 5 mm or more was associated with longer median TTP (13 vs. 5 months, p = 0.036), with no local tumor progression during the follow-up period. Additionally, Deschamps et al. conducted a retrospective analysis of patients who underwent thermal ablation of bone metastases with curative intent [121]. They reported a 1-year treatment completion rate of 67% and that favorable prognostic factors for successful local treatment include an oligometastatic and metachronous disease profile, small tumor size (less than 2 cm), and the absence of cortical erosions. This suggests that thermal ablation can also be indicated with curative intent.

6. Systemic Treatment

Selecting patients for systemic treatment involves evaluating specific characteristics, such as tumor characteristics, number and location of metastatic lesions, biological status of the tumor, patient profile, and the time interval between diagnosis and metastasis development [33,124]. Patients with OMBC tend to have one or two metastatic sites, primarily located in bone structures (53.2%), lymph nodes (19.7%), and liver (18.2%) [125]. Gogia et al. conducted an ambispective cohort study to describe the characteristics of 120 OMBC patients [126]. They found a variable distribution of hormone receptor statuses: 40% were ER and/or PR positive, 23.3% were ER/PR and HER2/neu positive, 17.5% were HER2/neu positive only, and 19.2% were triple-negative. Additionally, on multivariate analysis, they found that patients with hormone receptor-positive tumors (HR 0.46, p = 0.017), those with bone-only metastases (HR 0.54, p = 0.05), and those who underwent surgery of the primary tumor after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (HR 0.47, p = 0.013) had better PFS and clinical outcomes. This highlights the importance of systemic treatment, as it aims to slow the progression disease and manage symptoms [124].

Dürr et al. conducted a retrospective study to evaluate the effect of surgical therapy on a series of 70 patients with breast cancer and bone metastases [43]. Chemotherapy was used in 29 patients, of whom 9 received chemotherapy prior to surgery. They found that patients who underwent chemotherapy before surgery had worse prognosis than those who received chemotherapy afterward, likely due to more aggressive tumor behavior and resistance to systemic treatment. However, the heterogeneity of the patient population and the small sample size limit the generalizability of these findings. Studies evaluating the prognosis of bone metastases surgery following chemotherapy are still lacking.

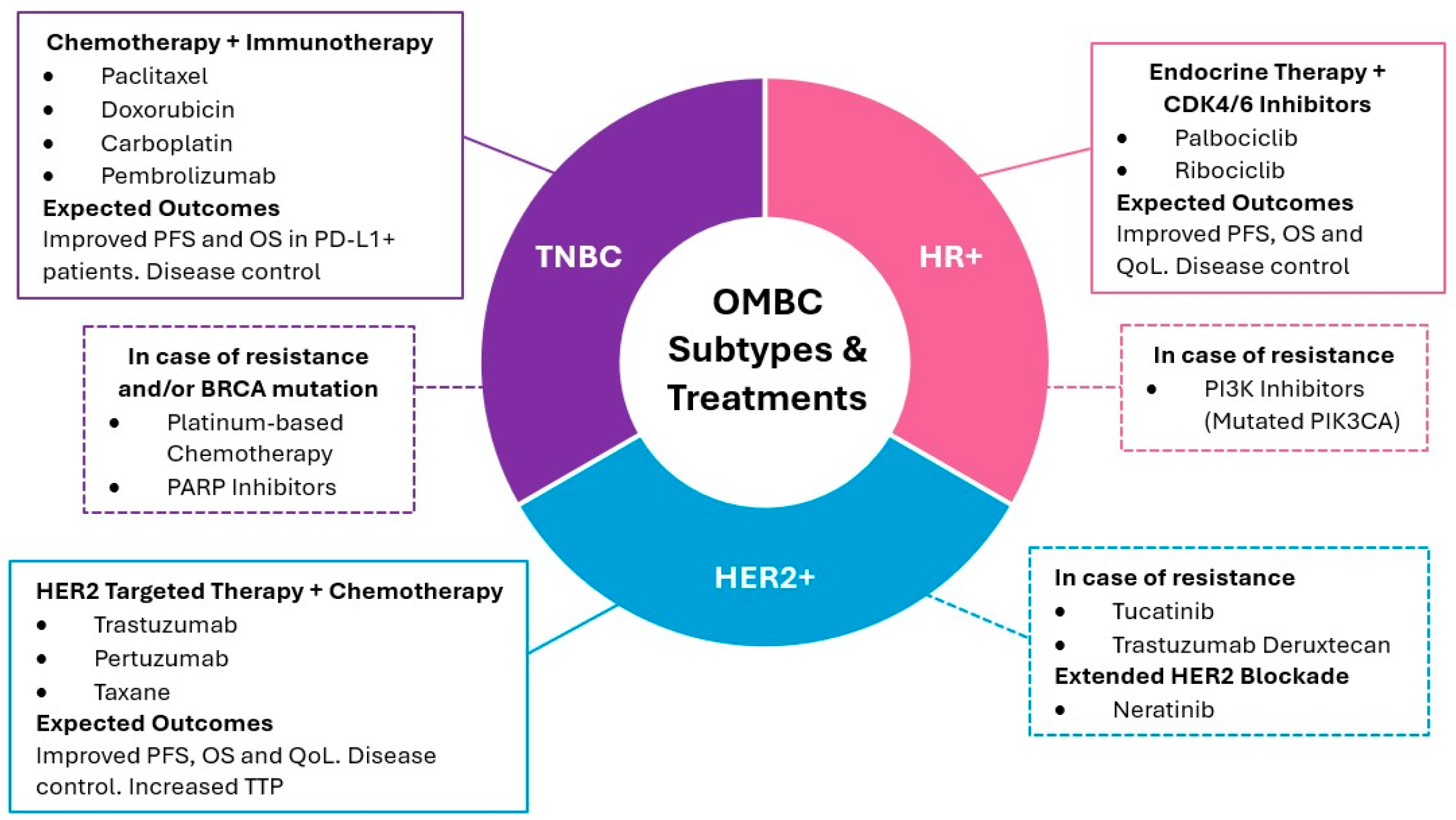

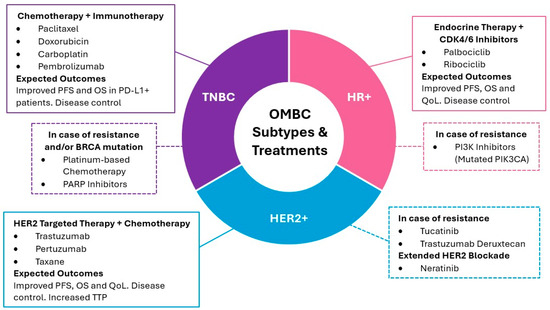

Systemic therapy for OMBC varies based on the biological status of the tumor, aligning with specific molecular and genetic characteristics (Figure 2). For instance, Chmura et al. conducted a phase IIR/III trial to determine the efficacy of combining standard of care systemic therapy (SOC ST) with locoregional therapy (SBRT and/or surgical resection) as first line treatment of OMBC, compared to SOC ST alone [127]. They included 125 OMBC patients, most of whom presented with bone lesions, followed by metastases to the lung and liver, and predominantly exhibited an HR+/HER2- phenotype. First-line systemic therapy consisted of chemotherapy, endocrine, and targeted treatments in 27%, 76%, and 67% of patients, respectively. Although the trial did not meet the primary endpoint of PFS and no OS benefit was captured, locoregional therapy prevented new lesions in the index area with minimal high-grade toxicity [127,128]. For patients with OMBC, more aggressive locoregional treatments, combined with systemic therapy, can improve long-term survival, aligning with ESO-ESMO recommendations for treating patients who are highly sensitive to treatment [129].

Figure 2.

Systemic treatment strategies for OMBC according to biological subtype. The diagram outlines the primary treatment modalities for HR+, HER2+, and TNBC subtypes, including first-line therapies and options for managing resistance, and additional information on extended HER2+ blockade [33,116,124,125,126,130,131,132,133,134,135]. PFS: progression free survival; OS: overall survival; QoL: quality of life; TTP: time to progression.

6.1. Systemic Treatment Selection by Biological Status

Systemic treatment selection according to biological status has been reported in multiple clinical trials (Table 4). For HR+ and HER2- subtypes, combining endocrine therapy with CDK4/6 inhibitors like palbociclib or ribociclib has significantly improved progression-free and overall survival, especially in bone-only metastases [125]. In patients with a high tumor burden or rapid progression, adding everolimus or alpelisib may be beneficial, particularly in cases with PIK3CA mutations [33]. HER2-positive patients benefit from HER2-targeted therapies such as trastuzumab and pertuzumab, often combined with chemotherapy, with trastuzumab plus pertuzumab and a taxane as the standard first-line treatment [124,126]. In cases of progression, second-line therapies like trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) or trastuzumab deruxtecan show promising results [116,130]. For patients with TNBC, chemotherapy remains the standard treatment, with platinum-based regimens favored, particularly in patients with BRCA mutations. PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors like pembrolizumab combined with chemotherapy have also shown survival benefits in selected TNBC patients [131]. In severe visceral involvement, immediate chemotherapy or systemic therapies are used to stabilize the patient [124].

Table 4.

Outcomes of systemic treatment selection by biological status in metastatic breast cancer patients.

6.2. Bone-Modifying Agents

Bone-modifying agents (BMAs) are essential in managing bone metastases from breast cancer, preventing skeletal-related events (SREs), reducing pain, and improving patients’ quality of life [149,150]. Bisphosphonates, such as zoledronic acid and pamidronate, inhibit osteoclast activity, preserving bone density and delaying SREs like pathological fractures, spinal cord compression, and the need for surgery or radiotherapy [151,152]. Zoledronic acid is particularly effective in reducing hypercalcemia of malignancy, a frequent complication in metastatic cancer, while also decreasing the need for radiotherapy when administered continuously for six months [151]. Additionally, it has demonstrated superior efficacy compared to pamidronate, reducing skeletal morbidity and delaying the time to the first SRE by up to 30% [152]. Zoledronic acid offers flexible dosing schedules, as it can be administered every 4 or 12 weeks without compromising treatment outcomes [152].

Denosumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody targeting the RANK/RANKL pathway, is a valuable alternative to bisphosphonates, particularly in patients with renal impairment where bisphosphonates might not be suitable [33,126,153]. By inhibiting osteoclast-mediated bone resorption, denosumab helps maintain bone strength and reduces the risk of multiple SREs, surpassing zoledronic acid in some clinical outcomes [152]. Its administration every 4 weeks via subcutaneous injection simplifies treatment, as it requires no renal monitoring, further enhancing its usability in clinical practice [152,153].

Current guidelines recommend both bisphosphonates and denosumab for managing bone metastases from breast cancer, emphasizing their role in reducing SREs, preserving bone strength, and minimizing the need for surgical or radiotherapeutic interventions [150]. Early initiation of bisphosphonate therapy, ideally within 3 months of surgery or 2 months of adjuvant chemotherapy, has been associated with better patient outcomes [150].

Combining BMAs with radiation therapy offers enhanced local control of osteolytic bone metastases, resulting in 75.0% bone reformation compared to 33.3% with BMAs alone [154]. This combination also accelerates symptom relief, with a median response time of 4 months versus 6 months for BMA-only treatment [154]. Moreover, patients responding to RT + BMA treatment show improved survival rates, with a 1-year overall survival rate of 83.1%, compared to 37.5% for non-responders [154].

7. Future Perspectives: Liquid Biopsies

Molecular advances such as liquid biopsies have emerged as promising tools for disease monitoring and treatment individualization in breast cancer. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) consists of tumor-derived DNA fragments that carry specific mutations released into the bloodstream [155]. ctDNA analysis offers a minimally invasive method to characterize tumor genomic profiles, allowing early detection of residual disease and tumor-acquired resistance [156]. Notably, ctDNA can potentially detect disease relapse before clinical and radiological confirmation. Garcia-Murillas et al. reported a median lead time of 10.7 months between ctDNA detection and clinical relapse, anticipating relapse in all major breast cancer subtype [157].

In the OMBC setting, ctDNA analysis may refine treatment selection, as patients with undetectable ctDNA could represent optimal candidates for aggressive local therapies with curative intent [158]. Moreover, ctDNA provides insights into tumor heterogeneity and clonal evolution, supporting its role in tracking treatment response and predicting prognosis [159]. While prognostic biomarkers are not yet clinically available, a recent meta-analysis reported a significant association between ctDNA detection and poorer survival outcomes, underscoring its potential as a prognostic biomarker in metastatic breast cancer [160]. Integrating ctDNA analysis into OMBC management algorithms could therefore improve treatment individualization and guide future therapeutic decisions.

8. Conclusions

Oligometastatic bone disease is increasingly recognized as a tumor presentation in breast cancer patients that offers the potential for long-term tumor control. The standard of care for patients with oligometastatic breast cancer affecting the bones involves a multidisciplinary approach that includes radiotherapy, surgery, and systemic therapy. Orthopedic surgery interventions have shown favorable outcomes in a subgroup of patients, particularly in cases involving spinal metastases, pathologic fractures, and solitary or oligo skeletal disease, with positive neurological and functional outcomes. Radiation therapy plays a crucial role in both local control and palliation of the disease. Systemic treatment remains a key component of treatment for bone metastatic breast cancer, and its selection should be guided by the tumor’s biological, molecular, and genetic characteristics. Although current treatment strategies are increasingly multimodal and individualized, the lack of standardized treatment protocols and consensus guidelines remains a significant challenge, underscoring the need for further research and harmonization in clinical practice. As bone metastatic disease remains a significant cause of morbidity in breast cancer, future research must focus on enhancing diagnostic and treatment guidelines specifically for oligometastatic bone disease.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P.-M. and M.R.G.; methodology, K.K.-L. and M.R.G.; validation, K.K.-L. and M.R.G.; formal analysis, K.K.-L. and M.R.G.; Investigation, K.K.-L., J.L. and A.O.L.-L.; data curation, K.K.-L., J.L. and A.O.L.-L.; writing—original draft preparation, K.K.-L., J.L. and A.O.L.-L.; writing—review and editing, M.R.G. and J.P.-M.; visualization, K.K.-L., J.L. and A.O.L.-L.; supervision, J.P.-M.; project administration, K.K.-L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Newman, L.A.; Freedman, R.A.; Smith, R.A.; Star, J.; Jemal, A.; Siegel, R.L. Breast Cancer Statistics 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 477–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, H.; Varamini, P. Breast Cancer Bone Metastasis: A Narrative Review of Emerging Targeted Drug Delivery Systems. Cells 2022, 11, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoni, E.; van der Pluijm, G. The Role of microRNAs in Bone Metastasis. J. Bone Oncol. 2016, 5, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretell-Mazzini, J.; Younis, M.H.; Subhawong, T. Skeletal Muscle Metastases from Carcinomas: A Review of the Literature. JBJS Rev. 2020, 8, e19.00114-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Arciero, C.; Jiang, R.; Behera, M.; Peng, L.; Li, X. Different Breast Cancer Subtypes Show Different Metastatic Patterns: A Study from A Large Public Database. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2020, 21, 3587–3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chikarmane, S.A.; Tirumani, S.H.; Howard, S.A.; Jagannathan, J.P.; DiPiro, P.J. Metastatic Patterns of Breast Cancer Subtypes: What Radiologists Should Know in the Era of Personalized Cancer Medicine. Clin. Radiol. 2015, 70, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellman, S.; Weichselbaum, R.R. Oligometastases. J. Clin. Oncol. 1995, 13, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guckenberger, M.; Lievens, Y.; Bouma, A.B.; Collette, L.; Dekker, A.; de Souza, N.M.; Dingemans, A.-M.C.; Fournier, B.; Hurkmans, C.; Lecouvet, F.E.; et al. Characterisation and Classification of Oligometastatic Disease: A European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology and European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Consensus Recommendation. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, e18–e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Dorn, P.; Chmura, S.; Weichselbaum, R.; Hasan, Y. Incidence and Implications of Oligometastatic Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, e11512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Ichiba, T.; Sakuyama, T.; Arakawa, Y.; Nagasaki, E.; Aiba, K.; Nogi, H.; Kawase, K.; Takeyama, H.; Toriumi, Y.; et al. Possible Clinical Cure of Metastatic Breast Cancer: Lessons from Our 30-Year Experience with Oligometastatic Breast Cancer Patients and Literature Review. Breast Cancer 2012, 19, 218–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, M.T.; Katz, A.W.; Zhang, H.; Okunieff, P. Oligometastases Treated with Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy: Long-Term Follow-Up of Prospective Study. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2012, 83, 878–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lievens, Y.; Guckenberger, M.; Gomez, D.; Hoyer, M.; Iyengar, P.; Kindts, I.; Romero, A.M.; Nevens, D.; Palma, D.; Park, C.; et al. Defining Oligometastatic Disease from a Radiation Oncology Perspective: An ESTRO-ASTRO Consensus Document. Radiother. Oncol. 2020, 148, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujari, L.; Suresh, A.; Chowdhury, Z.; Pradhan, S.; Tripathi, M.; Gupta, A.; Singh, P.; Giridhar, P.; Kapoor, A.R.; Shinghal, A.; et al. Outcomes of De Novo Oligometastatic Breast Cancer Treated with Surgery of Primary and Metastasis Directed Radiotherapy. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 47, 566–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijetunga, N.A.; Dos Anjos, C.H.; Zhi, W.I.; Robson, M.; Tsai, C.J.; Yamada, Y.; Dover, L.; Gillespie, E.F.; Xu, A.J.; Yang, J.T. Long-term Disease Control and Survival Observed after Stereotactic Ablative Body Radiotherapy for Oligometastatic Breast Cancer. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 5163–5174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, M.T.; Katz, A.W.; Zhang, H.; Huggins, C.F.; Aujla, K.S.; Okunieff, P. Oligometastatic Breast Cancer Treated with Hypofractionated Stereotactic Radiotherapy: Some Patients Survive Longer than a Decade. Radiother. Oncol. 2019, 131, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvarajan, G.; Dhanushkodi, M.; Radhakrishnan, V.; Murali, C.S.; Ananthi, B.; Iyer, P.; Krishnamurthy, A.; Velusamy, S.; Ganesarajah, S.; Sagar, T.G. The Continuing Conundrum in Oligometastatic Breast Carcinoma: A Real-World Data. Breast 2022, 63, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.M.; Bazan, J.G. Navigating Breast Cancer Oligometastasis and Oligoprogression: Current Landscape and Future Directions. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2024, 26, 647–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marazzi, F.; Masiello, V.; Orlandi, A.; Moschella, F.; Chiesa, S.; Di Leone, A.; Garufi, G.; Mazzarella, C.; Sanchez, A.M.; Casa, C.; et al. Outcomes of Radiotherapy in Oligoprogressive Breast Cancer. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zengel, B.; Kilic, M.; Tasli, F.; Simsek, C.; Karatas, M.; Ozdemir, O.; Cavdar, D.; Durusoy, R.; Bas, K.K.; Uslu, A. Breast Cancer Patients with Isolated Bone Metastases and Oligometastatic Bone Disease Show Different Survival Outcomes. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ommen–Nijhof, A.; Steenbruggen, T.G.; Schats, W.; Wiersma, T.; Horlings, H.M.; Mann, R.; Koppert, L.; van Werkhoven, E.; Sonke, G.S.; Jager, A. Prognostic Factors in Patients with Oligometastatic Breast Cancer—A Systematic Review. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2020, 91, 102114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhlin, I.; Fox, K. Oligometastatic Breast Cancer. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2020, 22, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovo, M.; Furlan, C.; Polesel, J.; Fiorica, F.; Arcangeli, S.; Giaj-Levra, N.; Alongi, F.; Del Conte, A.; Militello, L.; Muraro, E.; et al. Radical Radiation Therapy for Oligometastatic Breast Cancer: Results of a Prospective Phase II Trial. Radiother. Oncol. 2018, 126, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onal, C.; Guler, O.C.; Yildirim, B.A. Treatment Outcomes of Breast Cancer Liver Metastasis Treated with Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy. Breast 2018, 42, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rades, D.; Panzner, A.; Janssen, S.; Dunst, J.; Veninga, T.; Holländer, N.H.; Schild, S.E. Outcomes After Radiotherapy Alone for Metastatic Spinal Cord Compression in Patients with Oligo-Metastatic Breast Cancer. Anticancer. Res. 2018, 38, 6897–6903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbit, E.G.; Donnelly, E.D.; Strauss, J.B. Treatment Strategies for Oligometastatic Breast Cancer. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2021, 22, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberi, V.; Pietragalla, A.; Franceschini, G.; Marazzi, F.; Paris, I.; Cognetti, F.; Masetti, R.; Scambia, G.; Fabi, A. Oligometastatic Breast Cancer: How to Manage It? J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, C.L.; McDuff, S.G.R.; Salama, J.K. Oligometastatic Breast Cancer: Where Are We Now and Where Are We Headed?—A Narrative Review. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 5954968–5955968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merloni, F.; Palleschi, M.; Casadei, C.; Romeo, A.; Curcio, A.; Casadei, R.; Stella, F.; Ercolani, G.; Gianni, C.; Sirico, M.; et al. Oligometastatic Breast Cancer and Metastasis-Directed Treatment: An Aggressive Multimodal Approach to Reach the Cure. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2023, 15, 175883592311614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeed, H.; Kirby, A.M. Local Therapies for Managing Oligometastatic Breast Cancer: A Review. Ann. Breast Surg. 2022, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayama, N.; Katsui, K.; Watanabe, K.; Nagao, R.; Otsuki, K.; Hiraki, T.; Kanazawa, S. Radiation Therapy for Oligometastatic Bone Disease in Breast Cancer. Transl. Cancer Res. 2020, 9, 5096–5101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphal, T.; Gampenrieder, S.P.; Rinnerthaler, G.; Greil, R. Cure in Metastatic Breast Cancer. Memo Mag. Eur. Med. Oncol. 2018, 11, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marazzi, F.; Orlandi, A.; Manfrida, S.; Masiello, V.; Di Leone, A.; Massaccesi, M.; Moschella, F.; Franceschini, G.; Bria, E.; Gambacorta, M.A.; et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Bone Metastases in Breast Cancer: Radiotherapy, Local Approach and Systemic Therapy in a Guide for Clinicians. Cancers 2020, 12, 2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehne, J.; Tsagozis, P. Current Concepts in the Surgical Treatment of Skeletal Metastases. World J. Orthop. 2020, 11, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickels, J.; Dadia, S.; Lidar, Z. Surgical Management of Metastatic Bone Disease. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2009, 91, 1503–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westermann, L.; Olivier, A.C.; Samel, C.; Eysel, P.; Herren, C.; Sircar, K.; Zarghooni, K. Analysis of Seven Prognostic Scores in Patients with Surgically Treated Epidural Metastatic Spine Disease. Acta Neurochir. 2020, 162, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirels, H. The Classic: Metastatic Disease in Long Bones A Proposed Scoring System for Diagnosing Impending Pathologic Fractures. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2003, 415, S4–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willeumier, J.J.; Van Der Linden, Y.M.; Van Der Wal, C.W.P.G.; Jutte, P.C.; Van Der Velden, J.M.; Smolle, M.A.; Van Der Zwaal, P.; Koper, P.; Bakri, L.; De Pree, I.; et al. An Easy-to-Use Prognostic Model for Survival Estimation for Patients with Symptomatic Long Bone Metastases. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2018, 100, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsberg, J.A.; Eberhardt, J.; Boland, P.J.; Wedin, R.; Healey, J.H. Estimating Survival in Patients with Operable Skeletal Metastases: An Application of a Bayesian Belief Network. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafchinski, L.A. Metastasectomy for Oligometastatic Bone Disease of the Appendicular Skeleton: A Concise Review. J. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 128, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, H.; Yuan, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, F.; Wang, T.; Bian, L.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, S. Occurrence and Distribution of Bone Metastases in 984 Metastatic Breast Cancer Patients. Transl. Breast Cancer Res. 2021, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briasoulis, E.; Karavasilis, V.; Kostadima, L.; Ignatiadis, M.; Fountzilas, G.; Pavlidis, N. Metastatic Breast Carcinoma Confined to Bone: Portrait of a Clinical Entity. Cancer 2004, 101, 1524–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dürr, H.R.; Müller, P.E.; Lenz, T.; Baur, A.; Jansson, V.; Refior, H.J. Surgical Treatment of Bone Metastases in Patients with Breast Cancer. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2002, 396, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirstoiu, C.; Cretu, B.; Iordache, S.; Popa, M.; Serban, B.; Cursaru, A. Surgical Management Options for Long-Bone Metastasis. EFORT Open Rev. 2022, 7, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, C.K.; Kim, H.-S.; Yun, J.Y.; Cho, H.S.; Park, J.W.; Han, I. Factors Associated with Local Recurrence after Surgery for Bone Metastasis to the Extremities. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 117, 797–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, D.G. Diagnosis and Surgical Management of Breast Cancer Metastatic to the Spine. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 5, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patchell, R.A.; Tibbs, P.A.; Regine, W.F.; Payne, R.; Saris, S.; Kryscio, R.J.; Mohiuddin, M.; Young, B. Direct Decompressive Surgical Resection in the Treatment of Spinal Cord Compression Caused by Metastatic Cancer: A Randomised Trial. Lancet 2005, 366, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegener, B.; Schlemmer, M.; Stemmler, J.; Jansson, V.; Dürr, H.R.; Pietschmann, M.F. Analysis of Orthopedic Surgery of Bone Metastases in Breast Cancer Patients. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2012, 13, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soeharno, H.; Povegliano, L.; Choong, P.F. Multimodal Treatment of Bone Metastasis—A Surgical Perspective. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marulanda, G.A.; Mont, M.A.; Lucci, A.; Letson, G.D.; Khakpour, N. Orthopedic Surgery Implications of Breast Cancer. Expert Rev. Anticancer. Ther. 2008, 8, 949–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, R.J.; Tullberg, E.; Forsberg, J.A.; Bauer, H.C.; Wedin, R. Skeletal Metastases in 301 Breast Cancer Patients. Breast 2014, 23, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, D.; Gazendam, A.M.; Ghert, M. The Surgical Management of Proximal Femoral Metastases: A Narrative Review. Curr. Oncol. 2021, 28, 3748–3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedin, R.; Bauer, H.C.F.; Rutqvist, L.-E. Surgical Treatment for Skeletal Breast Cancer Metastases: A Population-Based Study of 641 Patients. Cancer 2001, 92, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, N.; Ahlmann, E.R.; Allison, D.C.; Wang, L.; Menendez, L.R. Endoprostheses Last Longer Than Intramedullary Devices in Proximal Femur Metastases. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2012, 470, 684–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipp, T.C.; Lam, P.W.; Gundle, K.R.; Putnam, D.S. Treatment Modalities for Pathologic Fractures of the Proximal Femur Pertrochanteric Region: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Reoperation Rates. J. Arthroplast. 2018, 33, 3354–3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Geyer, A.; Bourgoin, A.; Rousseau, C.; Ropars, M.; Bonnevialle, N.; Bouthors, C.; Descamps, J.; Niglis, L.; Sailhan, F.; Bonnevialle, P. Retrospective, Multicenter, Observational Study of 112 Surgically Treated Cases of Humerus Metastasis. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2020, 106, 1047–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redmond, B.J.; Biermann, J.S.; Blasier, R.B. Interlocking Intramedullary Nailing of Pathological Fractures of the Shaft of the Humerus. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 1996, 78, 891–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickels, J.; Kollender, Y.; Wittig, J.C.; Meller, I.; Malawer, M.M. Function after Resection of Humeral Metastases: Analysis of 59 Consecutive Patients. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2005, 437, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thai, D.M.; Kitagawa, Y.; Choong, P.F. Outcome of Surgical Management of Bony Metastases to the Humerus and Shoulder Girdle: A Retrospective Analysis of 93 Patients. Int. Semin. Surg. Oncol. 2006, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarahrudi, K.; Wolf, H.; Funovics, P.; Pajenda, G.; Hausmann, J.T.; Vécsei, V. Surgical Treatment of Pathological Fractures of the Shaft of the Humerus. J. Trauma Inj. Infect. Crit. Care 2009, 66, 789–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccioli, A.; Maccauro, G.; Rossi, B.; Scaramuzzo, L.; Frenos, F.; Capanna, R. Surgical Treatment of Pathologic Fractures of Humerus. Injury 2010, 41, 1112–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedin, R.; Hansen, B.H.; Laitinen, M.; Trovik, C.; Zaikova, O.; Bergh, P.; Kalén, A.; Schwarz-Lausten, G.; Vult Von Steyern, F.; Walloe, A.; et al. Complications and Survival after Surgical Treatment of 214 Metastatic Lesions of the Humerus. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2012, 21, 1049–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athwal, G.S.; Chin, P.Y.; Adams, R.A.; Morrey, B.F. Coonrad-Morrey Total Elbow Arthroplasty for Tumours of the Distal Humerus and Elbow. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2005, 87, 1369–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, M.R.; Okay, E.; Sodhi, A.S.; Lozano-Calderon, S.A. Reconstruction of the Elbow with Distal Humerus Endoprosthetic Replacement after Tumor Resection: A Systematic Review of the Literature and Institutional Case Series. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2024, 33, 1104–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzik, G. Results of the Treatment of Bone Metastases with Modular Prosthetic Replacement—Analysis of 67 Patients. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2016, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greco, T.; Fulchignoni, C.; Cianni, L.; Maccauro, G.; Perisano, C. Surgical Management of Tibial Metastases: A Systematic Review. Acta Biomed. Atenei Parm. 2022, 92, e2021552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.M.; Wilkins, R.M.; Eckardt, J.J.; Ward, W.G. Treatment of Metastatic Disease of the Tibia. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2003, 415, S219–S229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccioli, A.; Maccauro, G.; Scaramuzzo, L.; Graci, C.; Spinelli, M.S. Surgical Treatment of Impending and Pathological Fractures of Tibia. Injury 2013, 44, 1092–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scolaro, J.A.; Lackman, R.D. Surgical Management of Metastatic Long Bone Fractures: Principles and Techniques. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2014, 22, 90–100. [Google Scholar]

- Fourney, D.R.; Gokaslan, Z.L. Use of “MAPS” for Determining the Optimal Surgical Approach to Metastatic Disease of the Thoracolumbar Spine: Anterior, Posterior, or Combined: Invited Submission from the Joint Section Meeting on Disorders of the Spine and Peripheral Nerves, March 2004. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2005, 2, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, I.; Sciubba, D.M.; Madera, M.; Bydon, A.; Witham, T.J.; Gokaslan, Z.L.; Wolinsky, J.-P. Surgical Management of Metastatic Spinal Tumors. Cancer Control 2012, 19, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourney, D.R.; Gokaslan, Z.L. Anterior Approaches for Thoracolumbar Metastatic Spine Tumors. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 2004, 15, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.C.; Boland, P.; Mitra, N.; Yamada, Y.; Lis, E.; Stubblefield, M.; Bilsky, M.H. Single-Stage Posterolateral Transpedicular Approach for Resection of Epidural Metastatic Spine Tumors Involving the Vertebral Body with Circumferential Reconstruction: Results in 140 Patients: Invited Submission from the Joint Section Meeting on Disorders of the Spine and Peripheral Nerves, March 2004. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2004, 1, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, D.W.; Kumar, R. Palliative Subtotal Vertebrectomy with Anterior and Posterior Reconstruction via a Single Posterior Approach. J. Neurosurg. Spine 1999, 90, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilsky, M.H.; Boland, P.; Lis, E.; Raizer, J.J.; Healey, J.H. Single-Stage Posterolateral Transpedicle Approach for Spondylectomy, Epidural Decompression, and Circumferential Fusion of Spinal Metastases. Spine 2000, 25, 2240–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, H.J.; Bellón, J.M. Papel de la cirugía en las metástasis del cancer de mama. Cirugía Española 2007, 82, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incarbone, M.; Nava, M.; Lequaglie, C.; Ravasi, G.; Pastorino, U. Sternal Resection for Primary or Secondary Tumors. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1997, 114, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noguchi, S.; Miyauchi, K.; Nishizawa, Y.; Imaoka, S.; Koyama, H.; Iwanaga, T. Results of Surgical Treatment for Sternal Metastasis of Breast Cancer. Cancer 1988, 62, 1397–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, D.A.; Capanna, R. The Surgical Treatment of Pelvic Bone Metastases. Adv. Orthop. 2015, 2015, 525363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Hardan, W.; Garbrecht, E.; Huntley, K.; Pretell-Mazzini, J. Surgical Management Update in Metastatic Disease of the Pelvis Operative Techniques in Orthopaedics. Oper. Tech. Orthop. 2021, 31, 100897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavignac, P.; Prieur, J.; Fabre, T.; Descamps, J.; Niglis, L.; Carlier, C.; Bouthors, C.; Baron-Trocellier, T.; Sailhan, F.; Bonnevialle, P. Surgical Treatment of Peri-Acetabular Metastatic Disease: Retrospective, Multicentre Study of 91 THA Cases. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2020, 106, 1025–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozano-Calderon, S.A.; Clunk, M.J.; Gonzalez, M.R.; Sodhi, A.; Krueger, R.K.; Gruender, A.C.; Greenberg, D.D. Assessing Pain and Functional Outcomes of Percutaneous Stabilization of Metastatic Pelvic Lesions via Photodynamic Nails. JBJS Open Access 2024, 9, e23.00148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surov, A.; Hainz, M.; Holzhausen, H.-J.; Arnold, D.; Katzer, M.; Schmidt, J.; Spielmann, R.P.; Behrmann, C. Skeletal Muscle Metastases: Primary Tumours, Prevalence, and Radiological Features. Eur. Radiol. 2010, 20, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogiya, A.; Takahashi, K.; Sato, M.; Kubo, Y.; Nishikawa, N.; Kikutani, M.; Tadokoro, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Uematsu, T.; Watanabe, J.; et al. Metastatic Breast Carcinoma of the Abdominal Wall Muscle: A Case Report. Breast Cancer 2012, 22, 206–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herring, C.L.; Harrelson, J.M.; Scully, S.P. Metastatic Carcinoma to Skeletal Muscle: A Report of 15 Patients. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1998, 355, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Garrido, M.J.; Guillén-Ponce, C. Muscle Metastasis of Carcinoma. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2011, 13, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salemis, N.S. Skeletal Muscle Metastasis from Breast Cancer: Management and Literature Review. Breast Dis. 2015, 35, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretell-Mazzini, J.; De Neyra, J.Z.S.; Luengo-Alonso, G.; Shemesh, S. Skeletal Muscle Metastasis from the Most Common Carcinomas Orthopedic Surgeons Deal with. A Systematic Review of the Literature. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2017, 137, 1477–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.-X.; Gong, Y.; Ling, H.; Hu, X.; Shao, Z.-M. Racial/Ethnic Differences in the Outcomes of Patients with Metastatic Breast Cancer: Contributions of Demographic, Socioeconomic, Tumor and Metastatic Characteristics. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2019, 173, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francies, F.Z.; Hull, R.; Khanyile, R.; Dlamini, Z. Breast Cancer in Low-Middle Income Countries: Abnormality in Splicing and Lack of Targeted Treatment Options. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2020, 10, 1568–1591. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hankins, M.L.; Smith, C.N.; Hersh, B.; Heim, T.; Belayneh, R.; Dooley, S.; Lee, A.V.; Oesterreich, S.; Lucas, P.C.; Puhalla, S.L.; et al. Prognostic Factors and Survival of Patients Undergoing Surgical Intervention for Breast Cancer Bone Metastases. J. Bone Oncol. 2021, 29, 100363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouraria, G.G.; Matte, S.R.F.; Hanasilo, C.H.; Carvalho, M.J.R.D.; Etchebehere, M. Prognostic Factors in Patients with Breast Cancer Metastasis in the Femur Treated Surgically. Med. Express 2014, 1, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nathan, S.S.; Healey, J.H.; Mellano, D.; Hoang, B.; Lewis, I.; Morris, C.D.; Athanasian, E.A.; Boland, P.J. Survival in Patients Operated on for Pathologic Fracture: Implications for End-of-Life Orthopedic Care. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 6072–6082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratasvuori, M.; Wedin, R.; Keller, J.; Nottrott, M.; Zaikova, O.; Bergh, P.; Kalen, A.; Nilsson, J.; Jonsson, H.; Laitinen, M. Insight Opinion to Surgically Treated Metastatic Bone Disease: Scandinavian Sarcoma Group Skeletal Metastasis Registry Report of 1195 Operated Skeletal Metastasis. Surg. Oncol. 2013, 22, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratasvuori, M.; Wedin, R.; Hansen, B.H.; Keller, J.; Trovik, C.; Zaikova, O.; Bergh, P.; Kalen, A.; Laitinen, M. Prognostic Role of En-Bloc Resection and Late Onset of Bone Metastasis in Patients with Bone-Seeking Carcinomas of the Kidney, Breast, Lung, and Prostate: SSG Study on 672 Operated Skeletal Metastases. J. Surg. Oncol. 2014, 110, 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, R.; Smith, P.; Rubens, R. Clinical Course and Prognostic Factors Following Bone Recurrence from Breast Cancer. Br. J. Cancer 1998, 77, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciubba, D.M.; Gokaslan, Z.L.; Suk, I.; Suki, D.; Maldaun, M.V.C.; McCutcheon, I.E.; Nader, R.; Theriault, R.; Rhines, L.D.; Shehadi, J.A. Positive and Negative Prognostic Variables for Patients Undergoing Spine Surgery for Metastatic Breast Disease. Eur. Spine J. 2007, 16, 1659–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehadi, J.A.; Sciubba, D.M.; Suk, I.; Suki, D.; Maldaun, M.V.C.; McCutcheon, I.E.; Nader, R.; Theriault, R.; Rhines, L.D.; Gokaslan, Z.L. Surgical Treatment Strategies and Outcome in Patients with Breast Cancer Metastatic to the Spine: A Review of 87 Patients. Eur. Spine J. 2007, 16, 1179–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, W.; Li, Z.; Guo, L.; Niu, L.; Yan, M.; Niu, X. Surgical Efficacy and Prognosis of 54 Cases of Spinal Metastases from Breast Cancer. World Neurosurg. 2022, 165, e373–e379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, S.; Tan, J.; Savas, P.; Bressel, M.; Kelly, D.; Foroudi, F.; Loi, S.; Siva, S. Stereotactic Ablative Body Radiotherapy (SABR) for Bone Only Oligometastatic Breast Cancer: A Prospective Clinical Trial. Breast 2020, 49, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, D.A.; Olson, R.; Harrow, S.; Gaede, S.; Louie, A.V.; Haasbeek, C.; Mulroy, L.; Lock, M.; Rodrigues, G.B.; Yaremko, B.P.; et al. Stereotactic Ablative Radiotherapy for the Comprehensive Treatment of Oligometastatic Cancers: Long-Term Results of the SABR-COMET Phase II Randomized Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 2830–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschini, D.; Franzese, C.; Comito, T.; Ilieva, M.B.; Spoto, R.; Marzo, A.M.; Dominici, L.; Massaro, M.; Bellu, L.; Badalamenti, M.; et al. Definitive Results of a Prospective Non-Randomized Phase 2 Study on Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy (Sbrt) for Medically Inoperable Lung and Liver Oligometastases from Breast Cancer. Radiother. Oncol. 2024, 195, 110240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, R.; Mathews, L.; Liu, M.; Schellenberg, D.; Mou, B.; Berrang, T.; Harrow, S.; Correa, R.J.M.; Bhat, V.; Pai, H.; et al. Stereotactic Ablative Radiotherapy for the Comprehensive Treatment of 1-3 Oligometastatic Tumors (SABR-COMET-3): Study Protocol for a Randomized Phase III Trial. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, D.A.; Olson, R.; Harrow, S.; Correa, R.J.M.; Schneiders, F.; Haasbeek, C.J.A.; Rodrigues, G.B.; Lock, M.; Yaremko, B.P.; Bauman, G.S.; et al. Stereotactic Ablative Radiotherapy for the Comprehensive Treatment of 4–10 Oligometastatic Tumors (SABR-COMET-10): Study Protocol for a Randomized Phase III Trial. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, D.; Vonthein, R.; Illen, A.; Olbrich, D.; Barkhausen, J.; Richter, J.; Klapper, W.; Schmalz, C.; Rody, A.; Maass, N.; et al. Metastases-Directed Radiotherapy in Addition to Standard Systemic Therapy in Patients with Oligometastatic Breast Cancer: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Multi-National and Multi-Center Clinical Trial (OLIGOMA). Clin. Transl. Radiat. Oncol. 2021, 28, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chmura, S.; Winter, K.; Al-Hallaq, H.; Borges, V.; Jaskowiak, N.; Matuszak, M.; Milano, M. NRG-BR002: A Phase IIR/III Trial of Standard of Care Therapy with or without Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy (SBRT) and/or Surgical Ablation for Newly Oligometastatic Breast Cancer (NCT02364557). J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, TPS1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Investigating the Effectiveness of Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy (SBRT) in Addition to Standard of Care Treatment for Cancer That Has Spread Beyond the Original Site of Disease. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03808337?cond=NCT03808337&rank=1 (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Gangnam Severance Hospital. Local Treatment in ER-Positive/HER2-Negative Oligo-Metastatic Breast Cancer. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03750396?cond=NCT03750396&rank=1 (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Instituto do Cancer do Estado de São Paulo. Local Therapy for ER/PR-Positive Oligometastatic Breast Cancer (LARA). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04698252 (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- King Hussein Cancer Center. SBRT for Breast Cancer Oligometastases. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04424732?cond=NCT04424732&rank=1 (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Gustave Roussy, Cancer Campus, Grand Paris. Trial of Superiority of Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy in Patients with Breast Cancer. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT02089100?cond=NCT02089100&rank=1 (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- National Cancer Institute. Metastases Directed Therapy for Oligometastatic Breast Cancer. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06144346 (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. Radiotherapy for Extracranial Oligometastatic Breast Cancer. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04646564 (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Tokyo Medical and Dental University. Metastasis-Directed Therapy for Oligometastases of Breast Cancer. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06135714 (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust. Conventional Care Versus Radioablation (Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy) for Extracranial Oligometastases. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT02759783?cond=NCT02759783&rank=1 (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Linderholm, B.K.; Valachis, A.; Flote, V.G.; Poortmans, P.; Person, O.K.; Niligal-Yam, E.; O’Reilly, S.; Duane, F.; Marinko, T.; Ekholm, M.; et al. Treatment of Oligometastatic Breast Cancer (OMBC): A Randomised Phase III Trial Comparing Stereotactic Ablative Radiotherapy (SABR) and Systemic Treatment with Systemic Treatment Alone as First-Line Treatment—TAORMINA. ESMO Open 2023, 8, 101447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thureau, S.; Marchesi, V.; Vieillard, M.-H.; Perrier, L.; Lisbona, A.; Leheurteur, M.; Tredaniel, J.; Culine, S.; Dubray, B.; Bonnet, N.; et al. Efficacy of Extracranial Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy (SBRT) Added to Standard Treatment in Patients with Solid Tumors (Breast, Prostate and Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer) with up to 3 Bone-Only Metastases: Study Protocol for a Randomised Phase III Trial (STEREO-OS). BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenbruggen, T.G.; Schaapveld, M.; Horlings, H.M.; Sanders, J.; Hogewoning, S.J.; Lips, E.H.; Vrancken Peeters, M.-J.T.; Kok, N.F.; Wiersma, T.; Esserman, L.; et al. Characterization of Oligometastatic Disease in a Real-World Nationwide Cohort of 3447 Patients with de Novo Metastatic Breast Cancer. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2021, 5, pkab010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piroth, M.D.; Krug, D.; Feyer, P.; Baumann, R.; Combs, S.; Duma, M.-N.; Dunst, J.; Fastner, G.; Fietkau, R.; Guckenberger, M.; et al. Oligometastasis in Breast Cancer—Current Status and Treatment Options from a Radiation Oncology Perspective. Strahlenther. Onkol. 2022, 198, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwapisz, D. Oligometastatic Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer 2019, 26, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschamps, F.; Farouil, G.; Ternes, N.; Gaudin, A.; Hakime, A.; Tselikas, L.; Teriitehau, C.; Baudin, E.; Auperin, A.; De Baere, T. Thermal Ablation Techniques: A Curative Treatment of Bone Metastases in Selected Patients? Eur. Radiol. 2014, 24, 1971–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridouani, F.; Solomon, S.B.; Bryce, Y.; Bromberg, J.F.; Sofocleous, C.T.; Deipolyi, A.R. Predictors of Progression-Free Survival and Local Tumor Control after Percutaneous Thermal Ablation of Oligometastatic Breast Cancer: Retrospective Study. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2020, 31, 1201–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barral, M.; Auperin, A.; Hakime, A.; Cartier, V.; Tacher, V.; Otmezguine, Y.; Tselikas, L.; De Baere, T.; Deschamps, F. Percutaneous Thermal Ablation of Breast Cancer Metastases in Oligometastatic Patients. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2016, 39, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network NCCN Guidelines for Patients: Metastatic Breast Cancer. 2024. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/patients/guidelines/content/PDF/stage_iv_breast-patient.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- Glemarec, G.; Lacaze, J.-L.; Cabarrou, B.; Aziza, R.; Jouve, E.; Zerdoud, S.; Maio, E.D.; Massabeau, C.; Loo, M.; Esteyrie, V.; et al. Systemic Treatment with or without Ablative Therapies in Oligometastatic Breast Cancer: A Single Institution Analysis of Patient Outcomes. Breast 2023, 67, 102–109, Erratum in Breast 2023, 69, 424–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2023.03.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogia, A.; S Deo, S.; Sharma, D.; Mathur, S. Oligometastatic Breast Cancer: An Institutional Analysis. Indian J. Cancer 2022, 59, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chmura, S.J.; Winter, K.A.; Woodward, W.A.; Borges, V.F.; Salama, J.K.; Al-Hallaq, H.A.; Matuszak, M.; Milano, M.T.; Jaskowiak, N.T.; Bandos, H.; et al. NRG-BR002: A Phase IIR/III Trial of Standard of Care Systemic Therapy with or without Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy (SBRT) and/or Surgical Resection (SR) for Newly Oligometastatic Breast Cancer (NCT02364557). J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglietta, F.; Visani, L.; Marini, S.; Griguolo, G.; Vernaci, G.M.; Bottosso, M.; Dieci, M.V.; Meattini, I.; Guarneri, V. Oligometastatic Breast Cancer: Dissecting the Clinical and Biological Uniqueness of This Emerging Entity. Can We Pursue Curability? Cancer Treat. Rev. 2022, 110, 102462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, S.; Pereira, A.; de Paula, B.; Millen, E.; McAdam, K. Locoregional Treatment in Oligometastatic Breast Cancer: A Case Report and Review of Treatment Approaches in the Era of Cyclin Inhibitors. Curr. Probl. Cancer Case Rep. 2022, 5, 100140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visani, L.; Livi, L.; Ratosa, I.; Orazem, M.; Ribnikar, D.; Saieva, C.; Becherini, C.; Salvestrini, V.; Scoccimarro, E.; Valzano, M.; et al. Safety of CDK4/6 Inhibitors and Concomitant Radiation Therapy in Patients Affected by Metastatic Breast Cancer. Radiother. Oncol. 2022, 177, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, B.K.; Rybicki, L.; Abounader, D.; Andresen, S.; Kalaycio, M.; Sobecks, R.; Pohlman, B.; Hanna, R.; Dean, R.; Liu, H.; et al. Long-Term Survival after High-Dose Chemotherapy with Autologous Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation in Metastatic Breast Cancer. Hematol. Oncol. Stem Cell Ther. 2015, 8, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tutt, A.; Tovey, H.; Cheang, M.C.U.; Kernaghan, S.; Kilburn, L.; Gazinska, P.; Owen, J.; Abraham, J.; Barrett, S.; Barrett-Lee, P.; et al. A Randomised Phase III Trial of Carboplatin Compared with Docetaxel in BRCA1/2 Mutated and Pre-Specified Triple Negative Breast Cancer “BRCAness” Subgroups: The TNT Trial. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, M.; Im, S.-A.; Senkus, E.; Xu, B.; Domchek, S.M.; Masuda, N.; Delaloge, S.; Li, W.; Tung, N.; Armstrong, A.; et al. Olaparib for Metastatic Breast Cancer in Patients with a Germline BRCA Mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, F.; Ciruelos, E.; Rubovszky, G.; Campone, M.; Loibl, S.; Rugo, H.S.; Iwata, H.; Conte, P.; Mayer, I.A.; Kaufman, B.; et al. Alpelisib for PIK3CA-Mutated, Hormone Receptor–Positive Advanced Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1929–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.; Delaloge, S.; Holmes, F.A.; Moy, B.; Iwata, H.; Harvey, V.J.; Robert, N.J.; Silovski, T.; Gokmen, E.; von Minckwitz, G.; et al. Neratinib after Trastuzumab-Based Adjuvant Therapy in Patients with HER2-Positive Breast Cancer (ExteNET): A Multicentre, Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassier, P.A.; Chabaud, S.; Trillet-Lenoir, V.; Peaud, P.-Y.; Tigaud, J.-D.; Cure, H.; Orfeuvre, H.; Salles, B.; Martin, C.; Jacquin, J.-P.; et al. A Phase-III Trial of Doxorubicin and Docetaxel versus Doxorubicin and Paclitaxel in Metastatic Breast Cancer: Results of the ERASME 3 Study. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2008, 109, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sledge, G.W.; Neuberg, D.; Bernardo, P.; Ingle, J.N.; Martino, S.; Rowinsky, E.K.; Wood, W.C. Phase III Trial of Doxorubicin, Paclitaxel, and the Combination of Doxorubicin and Paclitaxel as Front-Line Chemotherapy for Metastatic Breast Cancer: An Intergroup Trial (E1193). J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 588–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, P.; Adams, S.; Rugo, H.S.; Schneeweiss, A.; Barrios, C.H.; Iwata, H.; Diéras, V.; Hegg, R.; Im, S.-A.; Shaw Wright, G.; et al. Atezolizumab and Nab-Paclitaxel in Advanced Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2108–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.S.; Martin, M.; Rugo, H.S.; Jones, S.; Im, S.-A.; Gelmon, K.; Harbeck, N.; Lipatov, O.N.; Walshe, J.M.; Moulder, S.; et al. Palbociclib and Letrozole in Advanced Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1925–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hortobagyi, G.N.; Stemmer, S.M.; Burris, H.A.; Yap, Y.S.; Sonke, G.S.; Paluch-Shimon, S.; Campone, M.; Petrakova, K.; Blackwell, K.L.; Winer, E.P.; et al. Updated Results from MONALEESA-2, a Phase III Trial of First-Line Ribociclib plus Letrozole versus Placebo plus Letrozole in Hormone Receptor-Positive, HER2-Negative Advanced Breast Cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 1541–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, S.M.; Baselga, J.; Kim, S.-B.; Ro, J.; Semiglazov, V.; Campone, M.; Ciruelos, E.; Ferrero, J.-M.; Schneeweiss, A.; Heeson, S.; et al. Pertuzumab, Trastuzumab, and Docetaxel in HER2-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 724–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, J.; Rugo, H.S.; Cescon, D.W.; Im, S.-A.; Yusof, M.M.; Gallardo, C.; Lipatov, O.; Barrios, C.H.; Perez-Garcia, J.; Iwata, H.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Advanced Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diéras, V.; Miles, D.; Verma, S.; Pegram, M.; Welslau, M.; Baselga, J.; Krop, I.E.; Blackwell, K.; Hoersch, S.; Xu, J.; et al. Trastuzumab Emtansine versus Capecitabine plus Lapatinib in Patients with Previously Treated HER2-Positive Advanced Breast Cancer (EMILIA): A Descriptive Analysis of Final Overall Survival Results from a Randomised, Open-Label, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 732–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arpino, G.; de la Haba Rodríguez, J.; Ferrero, J.-M.; De Placido, S.; Osborne, C.K.; Klingbiel, D.; Revelant, V.; Wohlfarth, C.; Poppe, R.; Rimawi, M.F. Pertuzumab, Trastuzumab, and an Aromatase Inhibitor for HER2-Positive and Hormone Receptor–Positive Metastatic or Locally Advanced Breast Cancer: PERTAIN Final Analysis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 1468–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huober, J.; Fasching, P.A.; Barsoum, M.; Petruzelka, L.; Wallwiener, D.; Thomssen, C.; Reimer, T.; Paepke, S.; Azim, H.A.; Ragosch, V.; et al. Higher Efficacy of Letrozole in Combination with Trastuzumab Compared to Letrozole Monotherapy as First-Line Treatment in Patients with HER2-Positive, Hormone-Receptor-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer—Results of the eLEcTRA Trial. Breast 2012, 21, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, S.R.D.; Hegg, R.; Im, S.-A.; Park, I.H.; Burdaeva, O.; Kurteva, G.; Press, M.F.; Tjulandin, S.; Iwata, H.; Simon, S.D.; et al. Phase III, Randomized Study of Dual Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2) Blockade with Lapatinib Plus Trastuzumab in Combination with an Aromatase Inhibitor in Postmenopausal Women with HER2-Positive, Hormone Receptor–Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer: Updated Results of ALTERNATIVE. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wesolowski, R.; Rugo, H.S.; Specht, J.M.; Han, H.S.; Kabos, P.; Vaishampayan, U.; Wander, S.A.; Gogineni, K.; Spira, A.; Schott, A.F.; et al. Gedatolisib Combined with Palbociclib and Letrozole in Patients with No Prior Systemic Therapy for Hormone Receptor–Positive, HER2-Negative Advanced Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 31, 4040–4048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardia, A.; Hurvitz, S.A.; Tolaney, S.M.; Loirat, D.; Punie, K.; Oliveira, M.; Brufsky, A.; Sardesai, S.D.; Kalinsky, K.; Zelnak, A.B.; et al. Sacituzumab Govitecan in Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1529–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]