The Impact of Social Determinants of Health on Supportive and Palliative Care in Pancreatic Cancer Management: A Narrative Review

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

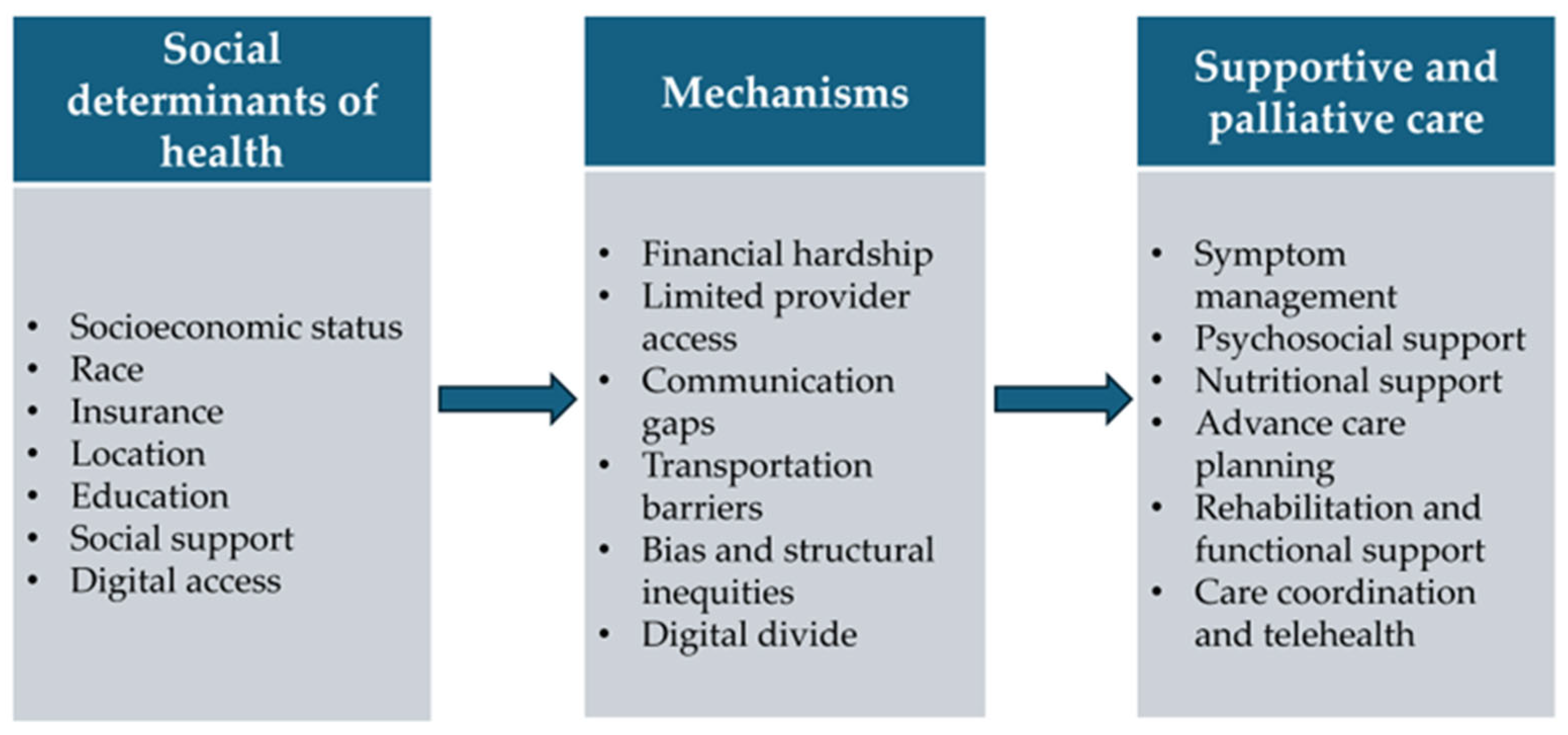

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Supportive and Palliative Care

3.1. Symptom Management

3.2. Psychological and Social Support

3.3. Nutritional Support

3.4. Advance Care Planning (ACP)

3.5. Rehabilitation and Functional Support

3.6. Care Coordination and Telehealth

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDOH | Social determinants of health |

| aOR | Adjusted odds ratio |

| PTBD | Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage |

| SES | Socioeconomic status |

| HPA | Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal |

| ERCP | Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography |

| ED | Emergency department |

| QoL | Quality of life |

| EPI | Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency |

| PERT | Pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy |

| ACP | Advance care planning |

| CHWs | Community Health Workers |

| PanCAN | Pancreatic Cancer Action Network |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 12–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, V.; Sun, V.; Ruel, N.; Smith, T.J.; Ferrell, B.R. Improving Palliative Care and Quality of Life in Pancreatic Cancer Patients. J. Palliat. Med. 2022, 25, 720–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Operational Framework for Monitoring Social Determinants of Health Equity; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, S.N.; Habib, J.R.; Hewitt, D.B.; Kluger, M.D.; Morgan, K.; Javed, A.A.; Wolfgang, C.L.; Sacks, G.D. The Impact of Social Determinants on Pancreatic Cancer Care in the United States. Cancers 2025, 17, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, N.E.; Newman, K. Socioeconomic disparities in health: Pathways and policies. Health Aff. 2002, 21, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, R.; Epstein, A.S. Palliative care and advance care planning for pancreas and other cancers. Chin. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 6, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohse, I.; Brothers, S.P. Pathogenesis and Treatment of Pancreatic Cancer Related Pain. Anticancer Res. 2020, 40, 1789–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelsen, D.P.; Portenoy, R.K.; Thaler, H.T.; Niedzwiecki, D.; Passik, S.D.; Tao, Y.; Banks, W.; Brennan, M.F.; Foley, K.M. Pain and depression in patients with newly diagnosed pancreas cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 1995, 13, 748–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akizuki, N.; Shimizu, K.; Asai, M.; Nakano, T.; Okusaka, T.; Shimada, K.; Inoguchi, H.; Inagaki, M.; Fujimori, M.; Akechi, T.; et al. Prevalence and predictive factors of depression and anxiety in patients with pancreatic cancer: A longitudinal study. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 46, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabora, J.; BrintzenhofeSzoc, K.; Curbow, B.; Hooker, C.; Piantadosi, S. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology 2001, 10, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zylberberg, H.M.; Woodrell, C.; Rustgi, S.D.; Aronson, A.; Kessel, E.; Amin, S.; Lucas, A.L. Opioid Prescription Is Associated with Increased Survival in Older Adult Patients with Pancreatic Cancer in the United States: A Propensity Score Analysis. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2022, 18, e659–e668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Chen, K.; He, J. Palliative management for malignant biliary obstruction and gastric outlet obstruction from pancreatic cancer. Ann. Gastroenterol. Surg. 2025, 9, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohri, N.; Rapkin, B.D.; Guha, C.; Kalnicki, S.; Garg, M. Radiation Therapy Noncompliance and Clinical Outcomes in an Urban Academic Cancer Center. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2016, 95, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyatt, G.; Sikorskii, A.; Tesnjak, I.; Victorson, D.; Srkalovic, G. Chemotherapy interruptions in relation to symptom severity in advanced breast cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2015, 23, 3183–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, J.M.; Awunti, M.; Guo, Y.; Bian, J.; Rogers, S.C.; Scarton, L.; DeRemer, D.L.; Wilkie, D.J. Unraveling Racial Disparities in Supportive Care Medication Use among End-of-Life Pancreatic Cancer Patients: Focus on Pain Management and Psychiatric Therapies. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2023, 32, 1675–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shavers, V.L.; Bakos, A.; Sheppard, V.B. Race, ethnicity, and pain among the U.S. adult population. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2010, 21, 177–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, C.R.; Ndao-Brumblay, S.K.; West, B.; Washington, T. Differences in prescription opioid analgesic availability: Comparing minority and white pharmacies across Michigan. J. Pain 2005, 6, 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, R.S.; Wallenstein, S.; Natale, D.K.; Senzel, R.S.; Huang, L.L. “We don’t carry that”—failure of pharmacies in predominantly nonwhite neighborhoods to stock opioid analgesics. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 342, 1023–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakkoli, A.; Singal, A.G.; Waljee, A.K.; Scheiman, J.M.; Murphy, C.C.; Pruitt, S.L.; Xuan, L.; Kwon, R.S.; Law, R.J.; Elta, G.H.; et al. Regional and racial variations in the utilization of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography among pancreatic cancer patients in the United States. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 3420–3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustgi, S.D.; Amin, S.P.; Kim, M.K.; Nagula, S.; Kumta, N.A.; DiMaio, C.J.; Boffetta, P.; Lucas, A.L. Age, socioeconomic features, and clinical factors predict receipt of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in pancreatic cancer. World J. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2019, 11, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipora, E.; Czerw, A.; Partyka, O.; Pajewska, M.; Badowska-Kozakiewicz, A.; Fudalej, M.; Sygit, K.; Kaczmarski, M.; Krzych-Falta, E.; Jurczak, A.; et al. Quality of Life in Patients with Pancreatic Cancer-A Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, N.; Beale, G.; O’Callaghan, C.; Melia, A.; DeSilva, W.; Costa, D.; Kissane, D.; Shapiro, J.; Hiscock, R. Timing of palliative care referral and aggressive cancer care toward the end-of-life in pancreatic cancer: A retrospective, single-center observational study. BMC Palliat. Care 2019, 18, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osagiede, O.; Nayar, K.; Raimondo, M.; Kumbhari, V.; Lukens, F.J. The Determinants of Inpatient Palliative Care Use in Patients with Pancreatic Cancer. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2024, 41, 1264–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, N.D.; Sheridan, S.L.; Donahue, K.E.; Halpern, D.J.; Crotty, K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet 2005, 365, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, J.C.; Moore, C.G.; Glover, S.H.; Samuels, M.E. Person and place: The compounding effects of race/ethnicity and rurality on health. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 1695–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boen, H.; Dalgard, O.S.; Bjertness, E. The importance of social support in the associations between psychological distress and somatic health problems and socio-economic factors among older adults living at home: A cross sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2012, 12, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birtel, M.D.; Wood, L.; Kempa, N.J. Stigma and social support in substance abuse: Implications for mental health and well-being. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 252, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Hu, J.; Zhang, B.; Ding, H.; Hu, D.; Li, H. The relationship between mental health literacy and professional psychological help-seeking behavior among Chinese college students: Mediating roles of perceived social support and psychological help-seeking stigma. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1356435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, J.; Buchler, M.W.; Friess, H.; Martignoni, M.E. Cachexia in patients with chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer: Impact on survival and outcome. Nutr. Cancer 2013, 65, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latenstein, A.E.J.; Dijksterhuis, W.P.M.; Mackay, T.M.; Beijer, S.; van Eijck, C.H.J.; de Hingh, I.; Molenaar, I.Q.; van Oijen, M.G.H.; van Santvoort, H.C.; de van der Schueren, M.A.E.; et al. Cachexia, dietetic consultation, and survival in patients with pancreatic and periampullary cancer: A multicenter cohort study. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 9385–9395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotogni, P.; Stragliotto, S.; Ossola, M.; Collo, A.; Riso, S.; On Behalf of The Intersociety Italian Working Group For Nutritional Support in Cancer. The Role of Nutritional Support for Cancer Patients in Palliative Care. Nutrients 2021, 13, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rausch, V.; Sala, V.; Penna, F.; Porporato, P.E.; Ghigo, A. Understanding the common mechanisms of heart and skeletal muscle wasting in cancer cachexia. Oncogenesis 2021, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partelli, S.; Frulloni, L.; Minniti, C.; Bassi, C.; Barugola, G.; D’Onofrio, M.; Crippa, S.; Falconi, M. Faecal elastase-1 is an independent predictor of survival in advanced pancreatic cancer. Dig. Liver Dis. 2012, 44, 945–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.W.; Jang, J.Y.; Kim, E.J.; Kang, M.J.; Kwon, W.; Chang, Y.R.; Han, I.W.; Kim, S.W. Effects of pancreatectomy on nutritional state, pancreatic function and quality of life. Br. J. Surg. 2013, 100, 1064–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Permuth, J.B.; Park, M.A.; Chen, D.T.; Basinski, T.; Powers, B.D.; Gwede, C.K.; Dezsi, K.B.; Gomez, M.; Vyas, S.L.; Biachi, T.; et al. Leveraging real-world data to predict cancer cachexia stage, quality of life, and survival in a racially and ethnically diverse multi-institutional cohort of treatment-naive patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1362244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olaechea, S.; Sarver, B.; Liu, A.; Gilmore, L.A.; Alvarez, C.; Iyengar, P.; Infante, R. Race, Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Factors as Determinants of Cachexia Incidence and Outcomes in a Retrospective Cohort of Patients with Gastrointestinal Tract Cancer. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2023, 19, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chittajallu, V.; Monk, I.N.; Saleh, M.A.; Lindsey, A.; Barkin, J.S.; Barkin, J.A.; Simons-Linares, C.R. S0005 Treatment of Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency in Pancreatic Cancer Is Low and Disproportionately Affects Older and African American Patients. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. ACG 2020, 115, S2–S3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Robin, G.; Kasnik, J.; Wong, G.; Abdel-Rahman, O. Challenges in Diagnosis and Treatment of Pancreatic Exocrine Insufficiency among Patients with Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancers 2023, 15, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, P.A.; Robertson, G.; Roy, D.J. Bioethics for clinicians: 6. Advance care planning. CMAJ 1996, 155, 1689–1692. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, A.A.; Zhang, B.; Ray, A.; Mack, J.W.; Trice, E.; Balboni, T.; Mitchell, S.L.; Jackson, V.A.; Block, S.D.; Maciejewski, P.K.; et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA 2008, 300, 1665–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wright, A.A.; Huskamp, H.A.; Nilsson, M.E.; Maciejewski, M.L.; Earle, C.C.; Block, S.D.; Maciejewski, P.K.; Prigerson, H.G. Health care costs in the last week of life: Associations with end-of-life conversations. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009, 169, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zabawa, B.J. Advance Care Planning is Critical to Overall Wellbeing. Am. J. Health Promot. 2023, 37, 422–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spelten, E.R.; Geerse, O.; van Vuuren, J.; Timmis, J.; Blanch, B.; Duijts, S.; MacDermott, S. Factors influencing the engagement of cancer patients with advance care planning: A scoping review. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2019, 28, e13091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LoPresti, M.A.; Dement, F.; Gold, H.T. End-of-Life Care for People with Cancer from Ethnic Minority Groups: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2016, 33, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramey, S.J.; Chin, S.H. Disparity in hospice utilization by African American patients with cancer. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2012, 29, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.J.; Hendifar, A.E.; Gresham, G.; Ngo-Huang, A.; Oberstein, P.E.; Parker, N.; Coveler, A.L. Exercise Guidelines in Pancreatic Cancer Based on the Dietz Model. Cancers 2025, 17, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.M.; Wahba, N.M.I.; Zaghamir, D.E.F.; Mersal, N.A.; Mersal, F.A.; Ali, R.A.E.; Eltaib, F.A.; Mohamed, H.A.H. Impact of a comprehensive rehabilitation palliative care program on the quality of life of patients with terminal cancer and their informal caregivers: A quasi-experimental study. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampedro Pilegaard, M.; Knold Rossau, H.; Lejsgaard, E.; Kjer Moller, J.J.; Jarlbaek, L.; Dalton, S.O.; la Cour, K. Rehabilitation and palliative care for socioeconomically disadvantaged patients with advanced cancer: A scoping review. Acta Oncol. 2021, 60, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elk, R.; Felder, T.M.; Cayir, E.; Samuel, C.A. Social Inequalities in Palliative Care for Cancer Patients in the United States: A Structured Review. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2018, 34, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, M.; Alvarez, R.; Gallego, J.; Guillen-Ponce, C.; Laquente, B.; Macarulla, T.; Munoz, A.; Salgado, M.; Vera, R.; Adeva, J.; et al. Consensus guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of patients with pancreatic cancer in Spain. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2017, 19, 667–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.N.; Maharaj, A.; Evans, S.; Pilgrim, C.; Zalcberg, J.; Brown, W.; Cashin, P.; Croagh, D.; Michael, N.; Shapiro, J.; et al. A qualitative investigation of the supportive care experiences of people living with pancreatic and oesophagogastric cancer. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.N.T.; Hartel, G.; Janda, M.; Wyld, D.; Merrett, N.; Gooden, H.; Neale, R.E.; Beesley, V.L. The Unmet Needs of Pancreatic Cancer Carers Are Associated with Anxiety and Depression in Patients and Carers. Cancers 2023, 15, 5307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noel, M.; Fiscella, K. Disparities in Pancreatic Cancer Treatment and Outcomes. Health Equity 2019, 3, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plate, S.; Emilsson, L.; Soderberg, M.; Brandberg, Y.; Warnberg, F. High experienced continuity in breast cancer care is associated with high health related quality of life. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfson, J.A.; Sun, C.L.; Wyatt, L.P.; Hurria, A.; Bhatia, S. Impact of care at comprehensive cancer centers on outcome: Results from a population-based study. Cancer 2015, 121, 3885–3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, S.; Khoong, E.C.; Lyles, C.R.; Karliner, L. Addressing Equity in Telemedicine for Chronic Disease Management During the Covid-19 Pandemic. NEJM Catal. 2020, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senft Everson, N.; Jensen, R.E.; Vanderpool, R.C. Disparities in Telehealth Offer and Use among U.S. Adults: 2022 Health Information National Trends Survey. Telemed. J. E Health 2024, 30, 2752–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcondes, F.O.; Normand, S.T.; Le Cook, B.; Huskamp, H.A.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Barnett, M.L.; Uscher-Pines, L.; Busch, A.B.; Mehrotra, A. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Telemedicine Use. JAMA Health Forum 2024, 5, e240131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffat, G.T.; Epstein, A.S.; O’Reilly, E.M. Pancreatic cancer-A disease in need: Optimizing and integrating supportive care. Cancer 2019, 125, 3927–3935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulaylat, A.S.; Mirkin, K.A.; Hollenbeak, C.S.; Wong, J. Utilization and trends in palliative therapy for stage IV pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients: A U.S. population-based study. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2017, 8, 710–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausner, D.; Tricou, C.; Mathews, J.; Wadhwa, D.; Pope, A.; Swami, N.; Hannon, B.; Rodin, G.; Krzyzanowska, M.K.; Le, L.W.; et al. Timing of Palliative Care Referral Before and After Evidence from Trials Supporting Early Palliative Care. Oncologist 2021, 26, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cann, C.G.; Shen, C.; LaPelusa, M.; Cardin, D.; Berlin, J.; Agarwal, R.; Eng, C. Palliative and supportive care underutilization for patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer: Review of the NCDB. ESMO Gastrointest. Oncol. 2024, 4, 100049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Q.D.; Hsieh, M.C.; Gibbs, J.F.; Wu, X.C. Treatment at a high-volume academic research program mitigates racial disparities in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2021, 12, 2579–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoehn, R.S.; Rieser, C.J.; Winters, S.; Stitt, L.; Hogg, M.E.; Bartlett, D.L.; Lee, K.K.; Paniccia, A.; Ohr, J.P.; Gorantla, V.C.; et al. A Pancreatic Cancer Multidisciplinary Clinic Eliminates Socioeconomic Disparities in Treatment and Improves Survival. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 28, 2438–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppsteiner, R.W.; Csikesz, N.G.; McPhee, J.T.; Tseng, J.F.; Shah, S.A. Surgeon volume impacts hospital mortality for pancreatic resection. Ann. Surg. 2009, 249, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, A.J.; Gray, B.H.; Schlesinger, M. Racial and ethnic differences in the use of high-volume hospitals and surgeons. Arch. Surg. 2010, 145, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manisundaram, N.; Snyder, R.A.; Hu, C.Y.; DiBrito, S.R.; Chang, G.J. Racial disparities in cancer mortality in patients with gastrointestinal malignancies following Medicaid expansion. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 6546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalingam, K.; Ji, L.; O’Leary, M.P.; Lum, S.S.; Caba Molina, D. Medicaid Expansion and Overall Survival of Lower Gastrointestinal Cancer Patients After Cytoreductive Surgery and Heated Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2025, 32, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.; Cherla, D.; Mehari, K.; Tripathi, M.; Butler, T.W.; Crook, E.D.; Heslin, M.J.; Johnston, F.M.; Fonseca, A.L. Palliative Therapies in Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer: Does Medicaid Expansion Make a Difference? Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 30, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paro, A.; Rice, D.R.; Hyer, J.M.; Palmer, E.; Ejaz, A.; Shaikh, C.F.; Pawlik, T.M. Telehealth Utilization Among Surgical Oncology Patients at a Large Academic Cancer Center. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 29, 7267–7276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.I.; Kapphahn, K.; Wood, E.; Coker, T.; Salava, D.; Riley, A.; Krajcinovic, I. Effect of a Community Health Worker-Led Intervention Among Low-Income and Minoritized Patients with Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS Finalizes Physician Payment Rule that Advances Health Equity; Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: Woodlawn, MD, USA, 2023.

- Herremans, K.M.; Riner, A.N.; Winn, R.A.; Trevino, J.G. Diversity and Inclusion in Pancreatic Cancer Clinical Trials. Gastroenterology 2021, 161, 1741–1746.E3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Domain of Care | SDOH | Affected Group | Observed Disparity | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom management | Race | Black, Asian, and Hispanic patients | Opioids: Lower utilization among Black: aOR 0.84 (95% CI 0.79–0.88) and Asian: aOR 0.84 (95% CI 0.79–0.90) patients compared with Non-Hispanic Whites; Antidepressants: Lower utilization among Black aOR 0.56 (95% CI 0.53–0.59), Hispanic aOR 0.77 (95% CI 0.73–0.82) and Asian patients aOR 0.47 (95% CI 0.44–0.51) compared with Non-Hispanic Whites. | Allen et al., [15] |

| Race, location | Non-White neighborhoods | Opioid availability: Stocked in only 25% of pharmacies in predominantly non-White neighborhoods vs. 72% in White neighborhoods. | Morrison et al., [18] | |

| Race, location | Minority neighborhoods | Opioid availability: Adequate in 54% of pharmacies in minority neighborhoods vs. 86.9% in White neighborhoods. | Green et al., [17] | |

| Race | Black patients | ERCP utilization: Lower among Black patients (aOR 0.84 (95% CI 0.72–0.97)) compared to white patients. | Tavakkoli et al., [19] | |

| Age, marital status, location | Older patients, unmarried, and rural area | ERCP utilization: Lower among older individuals (aOR 0.88 (95% CI 0.83–0.94)), unmarried individuals, (aOR 0.92 (95% CI 0.86–0.98)), and rural residents (aOR 0.89 (95% CI 0.82–0.98)) | Rustgi et al., [20] | |

| Psychological and social support | Access to palliative and supportive care | Patients receiving late palliative care | Inappropriate end-of-life care impacted psychological well-being. Comparing early to late palliative care referral, the second group had more ED presentations (18.1% (95% CI 6.8–29.4%)) and more acute hospital admissions (12.5% (95% CI 1.7–24.8%)). | Michael et al., [22] |

| Patients receiving late palliative care | Early palliative care may improve QoL and psychological distress: 26 pancreatic cancer patients received advanced practice nurse driven palliative care intervention versus 16 patients receiving normal care. A positive impact on treatment, potentially leading to longer survival, was observed in the intervention arm. | Chung et al., [2] | ||

| Gender, age, insurance status, comorbidity | Younger, male, Medicare insured, lower Charlson comorbidity score | Retrospectively (22,053 pancreatic cancer patients), less access to psychological support services. | Osagiede et al., [23] | |

| SES | Low SES patients | Association between lack of social support and psychological distress. Even and indicated direct effect. | Bøen et al., [27] | |

| Nutritional support | Race | Black and Hispanic patients | Cachexia risk: Higher in Black (aOR 2.447 (95% CI 1.62–3.697)) and Hispanic patients (aOR 3.039 (95% CI 1.943–4.754)) vs. Non-Hispanic White patients. | Olaechea et al., [37] |

| Race | African American patients, older patients | PERT utilization: Less likely in African Americans (OR 0.7281 (95% CI 0.6628–0.7998)) and older patients (OR 0.8064 (95% CI 0.7604–0.8551)). | Chittajallu et al., [38] | |

| Advance Care Planning (ACP) | Race, education, support network | Non-White, less-educated, no support network | White, well-educated patients with a support network were more likely to be involved in ACP. However, within cancer patients, there is limited comprehension regarding ACP. | Spelten et al., [44] |

| Race | African and Asian Americans | Higher need for hospice care, yet more frequently inadequate knowledge. Inconsistency with the patients’ preferences or inadequate documentation of their ACP involving religious or spiritual beliefs. | LoPresti et al., [45] | |

| Education, language, literacy skills | Less-educated, language barrier | Poor health literacy, limited time in outpatient settings, inaccurate prognostic expectations, and gaps in understanding can be an obstacle in making well-informed decisions, considering all the preferences and wishes for the patients’ care goals. | Agarwal and Epstein [6] | |

| Rehabilitation and functional support | SES | Patients with financial constrains | A barrier to utilizing palliative care. | Marc Sempedro Pilegaard et al., [49] |

| Immigration status, SES, disability | Immigrants, homeless, disabled | Lack of access to palliative care and lack of research to meet the needs of these vulnerable groups. | Elk et al., [50] | |

| Care coordination and telehealth | Access to care | Patients treated at centers without formalized care coordination | Centers with established multidisciplinary teams experience improved survival outcomes and QoL. Barriers to receiving care at these centers are race/ethnicity, insurance status, SES, and geography. | Wolfson et al., [56] |

| Age, SES, race | Digital literacy and technology access | Barriers to telehealth utilization. | Nouri et al., [57] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

van Herwijnen, S.; Jayaprakash, V.; Hidalgo Salinas, C.; Habib, J.R.; Hewitt, D.B.; Sacks, G.D.; Wolfgang, C.L.; Morgan, K.A.; Kaplan, B.J.; Kluger, M.D.; et al. The Impact of Social Determinants of Health on Supportive and Palliative Care in Pancreatic Cancer Management: A Narrative Review. Cancers 2025, 17, 3254. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193254

van Herwijnen S, Jayaprakash V, Hidalgo Salinas C, Habib JR, Hewitt DB, Sacks GD, Wolfgang CL, Morgan KA, Kaplan BJ, Kluger MD, et al. The Impact of Social Determinants of Health on Supportive and Palliative Care in Pancreatic Cancer Management: A Narrative Review. Cancers. 2025; 17(19):3254. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193254

Chicago/Turabian Stylevan Herwijnen, Sterre, Vishnu Jayaprakash, Camila Hidalgo Salinas, Joseph R. Habib, Daniel Brock Hewitt, Greg D. Sacks, Christopher L. Wolfgang, Katherine A. Morgan, Brian J. Kaplan, Michael D. Kluger, and et al. 2025. "The Impact of Social Determinants of Health on Supportive and Palliative Care in Pancreatic Cancer Management: A Narrative Review" Cancers 17, no. 19: 3254. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193254

APA Stylevan Herwijnen, S., Jayaprakash, V., Hidalgo Salinas, C., Habib, J. R., Hewitt, D. B., Sacks, G. D., Wolfgang, C. L., Morgan, K. A., Kaplan, B. J., Kluger, M. D., Aggarwal, A., & Javed, A. A. (2025). The Impact of Social Determinants of Health on Supportive and Palliative Care in Pancreatic Cancer Management: A Narrative Review. Cancers, 17(19), 3254. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193254