1. Introduction

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), advanced ovarian cancer and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) are known for their high therapeutic resistance [

1]. These cancers commonly exhibit pathogenic variants in homologous recombination DNA repair genes, particularly

BRCA,

ATM,

BARD1,

RAD51 and

PALB2, resulting in impaired DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) repair [

2,

3]. Since homologous recombination is an essential DNA repair pathway to preserve genomic stability, its inhibition, namely, by targeting ATM, ATR, CHK1, CHK2, WEE1, RAD51 and RAD52, represents a promising therapeutic strategy in cancer treatment. These inhibitors are currently under study and some of them have reached clinical trials, supporting further studies aiming to unravel new homologous recombination inhibitors [

4].

BRCAs are critical components of homologous recombination DNA repair. Mutations in these proteins are related to increased cancer risk [

5]. Despite this, compiled data have highlighted that cancer patients harbouring BRCA mutations (mutBRCA) exhibit increased sensitivity to platinum-based chemotherapy and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors (PARPis), demonstrating that BRCA deficiency may improve therapeutic response [

6]. In fact, PARPis have emerged as an encouraging targeted therapy for mutBRCA-associated tumors, since the mutual disfunction of BRCA and PARP (an essential enzyme in DNA single-strand break repair) can induce synthetic lethality in DNA repair defective cancer cells [

3]. Briefly, PARPis trap PARP enzymes at the damage site by binding to the ADP ribosyltransferase catalytic domain, promoting the progression of single-strand breaks to DSBs, impairing the progression of replication forks and requiring a functional homologous recombination DNA repair to overcome this inhibition [

5]. The PARPi olaparib was approved for mutBRCA locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer, as maintenance therapy of mutBRCA advanced ovarian cancer and for metastatic PDAC [

7]. However, although effective in mutBRCA-associated DNA repair defective cancers and in an additional subset of cancer patients exhibiting BRCAness phenotype (harbouring DNA repair defects in non-

BRCA genes, producing BRCA-like homologous recombination impairment), most cancers harbour wild-type BRCA (wtBRCA), which greatly limits the clinical potential of PARPis as a monotherapy [

4]. Since the percentage of cancer patients responsive to PARPis is very limited, studies have been focused on establishing combination strategies to widen the application of PARPis to a larger population of cancer patients. In fact, PARPis have shown synergistic effects in combination with several cytotoxic agents, highlighting their promising contribution to the effectiveness of the standard-of-care therapies [

5]. However, acquired resistance to PARPis has been commonly observed, particularly by residual DNA repair activity, involving restoration or overexpression of DNA repair machinery [

3]. For instance, an increased RAD51 foci formation is commonly observed in mutBRCA cancers and its overexpression is associated with PARPi resistance in breast cancer cells [

8,

9]. Another strategy for extending the spectrum of PARPi applications is their combinatorial use with BRCAness inducers [

4].

Xanthones are

O-heteroaromatic tricyclic scaffolds, which provide a wide range of derivatives with several biological responses, representing a privileged structure for anticancer drug development [

10]. Particularly, this class of oxygen-containing heterocyclic compounds can intercalate into the base group pairs of DNA due to the appropriate planarity of the xanthone ring, causing DNA damage in cancer cells through non-covalent interaction with DNA [

11,

12]. In addition, the glycosidic moiety of natural glycosides of flavonoids and xanthones may exhibit biological activities that positively affect the antitumor activity [

13]. Furthermore, the acylation process proves to be important to the cell growth inhibitory activity, also improving the cell membrane penetration of compounds such as flavonoids [

14]. Thus, acetylated xanthone glycosides are revealed to be promising inhibitors of cancer cell growth.

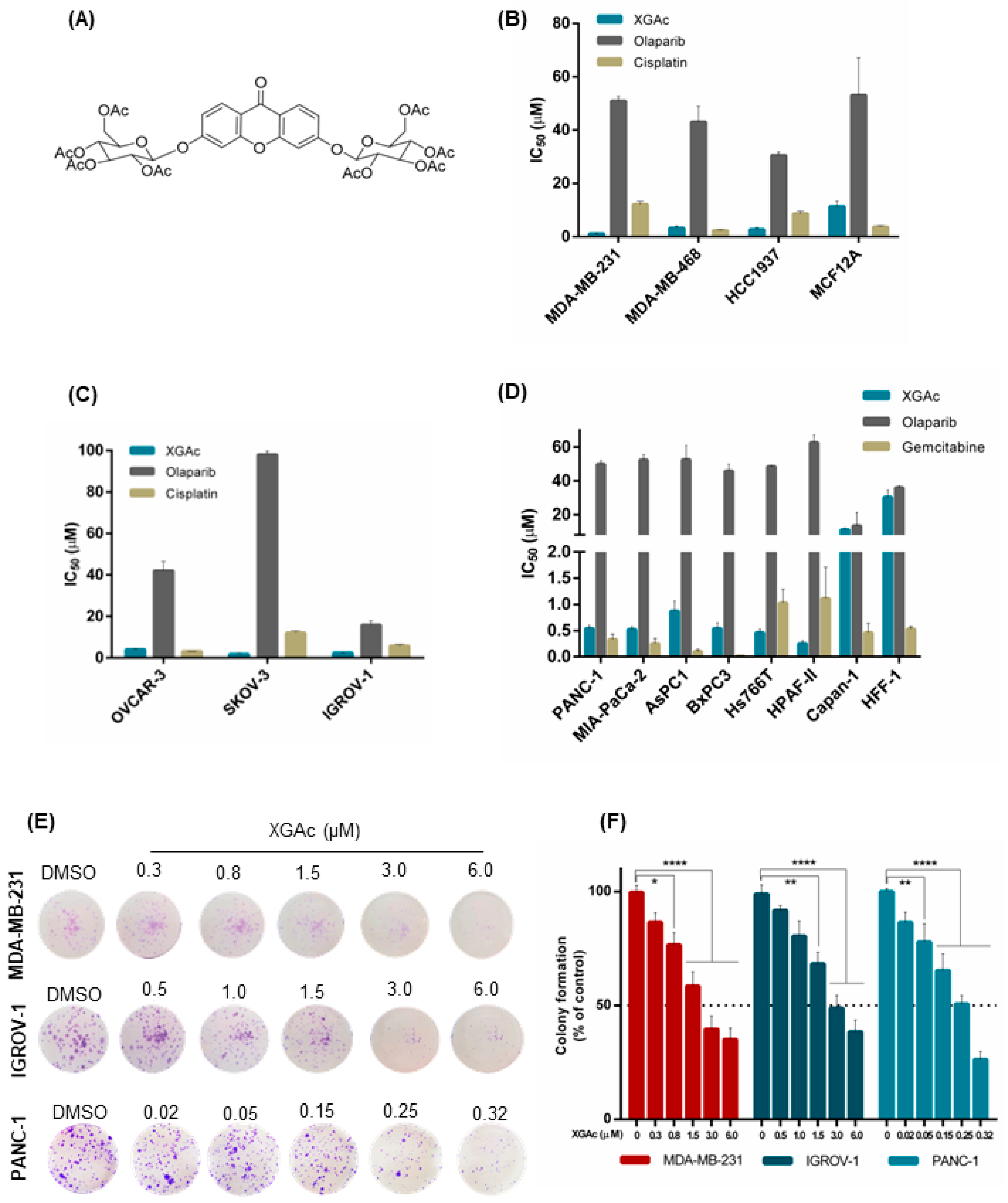

Previously, we disclosed a new acetylated xanthonoside, 3,6-bis(2,3,4,6-tetra-

O-acetyl-β-glucopyranosyl)xanthone (XGAc;

Figure 1A), which inhibited the growth of glioma, melanoma, breast adenocarcinoma, glioblastoma astrocytoma, and non-small cell lung cancer cells [

15]. Interestingly, the non-acetylated xanthonoside did not reach 50% of cell growth inhibition, evidencing the relevance of the acylation process to improve the antitumor activity [

15]. Herein, we aimed to explore the antitumor activity of XGAc, either as a single agent or in combination with olaparib, in hard-to-treat cancers, including TNBC, ovarian cancer and PDAC.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Compounds

XGAc was synthesized as described in [

15]. XGAc, olaparib (AZD2281; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Frilabo, Portugal) and gemcitabine (Sigma-Aldrich, Sintra, Portugal) were dissolved in DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, Sintra, Portugal), while cisplatin (Enzo Life Science, Taper, Sintra, Portugal) was dissolved in saline. The solvent (maximum 0.1%) was included as control.

2.2. Human Cancer Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

The human cancer cell lines MDA-MB-231 (triple-negative metastatic breast adenocarcinoma), MDA-MB-468 (triple-negative metastatic breast adenocarcinoma), HCC1937 (triple-negative breast primary ductal carcinoma), OVCAR-3 (metastatic high-grade ovarian serous adenocarcinoma), SKOV-3 (metastatic ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma), IGROV-1 (ovarian endometrioid adenocarcinoma), AsPC-1 (metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma) and Hs766T (metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma) were grown in RPMI-1640 medium with UltraGlutamine (Biowest, VWR, Carnaxide, Portugal) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Biowest, VWR, Carnaxide, Portugal), while PANC-1 (pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma), MIA-PaCa-2 and GEM-resistant MIA-PaCa-2 (generated and kindly supplied by Dr Luigi Sapio from [

16]) (pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma), BxPC3 (pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma), and HPAF-II (metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma) were grown in DMEM high glucose (4.5 g/L glucose) with stable L-glutamine and sodium pyruvate supplemented with 10% FBS. Capan-1 cell line (metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma) was cultured in Iscove Modified Dulbecco Media (IMDM) 20% FBS. The normal human foreskin fibroblast HFF-1 cells were grown in DMEM F12 10% FBS. The normal human breast MCF-12A cells were cultured in DMEM F12 10% FBS, 20 ng/mL EGF, 100 ng/mL cholera toxin, 0.01 mg/mL insulin and 500 ng/mL hydrocortisone.

Cells were grown at 37 °C in a 5% CO

2 humidified atmosphere. Cell number and viability were assessed with trypan blue exclusion assay. Cells were routinely tested for mycoplasma infection using the MycoAlert™ PLUS mycoplasma detection kit (Lonza). Additional information about cells can be found in

Supplementary Table S1.

Patient-Derived Ovarian Cancer Cells

The patient-derived ovarian cancer (PD-OVCA) cells 1, 9, 41, 49 and 62 were obtained from ascitic effusions of epithelial ovarian cancer patients. These cells were routinely maintained as serial xenotransplants, as previously described [

17]. The study was approved by IOV Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee (EM 23/2017) and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from patients who entered this study. Procedures in animals were conformed to institutional guidelines that comply with national and international laws and policies (EEC Council Directive 86/609, OJ L 358, 12 December 1987) and were authorized by the Italian Ministry of Health (Authorization No. 617/2016 PR). Animal studies are reported in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines [

18].

Patient-derived cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 media with UltraGlutamine (Invitrogen, Milan, Italy) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco, Invitrogen), 2 mM L-glutamine, sodium pyruvate, 10 nmol/L HEPES and 100 U/mL Penicillin/Streptomycin, for a maximum of 2 weeks, as in [

19]. Additional information about patient-derived cancer cells can be found in

Supplementary Table S2.

2.3. Cell Viability and Proliferation Assays

The human cell lines MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-468, HCC1937, MCF12A, OVCAR-3, SKOV-3, IGROV-1, PANC-1, MIA-PaCa-2, GEM-resistant MIA-PaCa-2, AsPC-1, BxPC3, HS766T, HPAF-II, Capan-1 (5.0 × 10

3) and HFF-1 (1.0 × 10

4) cells/well were seeded in 96-well plates and allowed to adhere overnight, followed by treatment with serial compound dilutions, for 48 h. Half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC

50) values were determined for each cell line by sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay, as described [

19].

For PDOVCA 1, 9, 41, 49 and 62 cells, 7.5 × 10

3 cells/well were seeded in 96-well plates, and the IC

50 values were determined with the CellTiter96

® Aqueous one solution cell proliferation assay (MTS assay; Promega, Italy) after 48 h of treatment, as described [

19].

For the colony formation assay, MDA-MB-231, IGROV-1 and PANC-1 (1 × 103) cells/well were seeded in six-well plates and treated at the seeding time with a range of concentrations of XGAc for 15 days. Colonies were fixed with 10% methanol and 10% acetic acid for 10 min and stained with 0.5% crystal violet (Sigma-Aldrich) in 1:1 methanol/H2O for 15 min. Colonies containing more than 20 cells were counted.

2.4. Mammosphere Generation

HCC1937 cells, 1.5 × 10

3 cells/well, were seeded in 24-well plates coated with 1% agarose in DMEM F12 supplemented with 20 ng/mL bFGF, 40 ng/mL EGF (Bio-techne, Citomed Lda, Lisboa, Portugal), 1x B27 (Life Technologies, Porto, Portugal), 10 μg/mL insulin (Sigma-Aldrich, Sintra, Portugal) and 2 mM L-glutamine (Sigma) and treated with XGAc at the seeding time, as in [

19]. After 72 h, mammosphere growth was monitored using an inverted Nikon TE 2000-U microscope at 100× magnification, with a DXM1200F digital camera and NIS-Elements microscope imaging software (RRID:SCR_014329, Nikon Instruments Inc, Izasa, Carnaxide, Portugal). Spheroid area was quantified using Fiji Software (RRID:SCR_002285) [

20].

2.5. Cell Cycle and Apoptosis Analysis

MDA-MB-231, IGROV-1 and PANC-1 (1.5 × 105 cells/well) were seeded in six-well plates and allowed to adhere overnight, followed by treatment with XGAc for 48 h. Briefly, cells were stained with propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich) and analyzed by flow cytometry for the identification and quantification of cell cycle phases. For apoptosis analysis, cells were stained using the Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit I from BD Biosciences (Enzifarma, Porto, Portugal), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The AccuriTM C6 flow cytometer, BD Accuri C6 software (RRID:SCR_014422, BD Biosciences) and FlowJo X 10.0.7 software (RRID:SCR_008520, Treestar, Ashland, OR, USA) were used.

2.6. Western Blot Analysis

MDA-MB-231, IGROV-1 and PANC-1 (1.5 × 10

5 cells/well) were seeded in six-well plates, allowed to adhere overnight and treated with XGAc for 48 h. Briefly, protein lysates were quantified using Pierce

® BCA Protein Assay reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Porto Salvo, Portugal), resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and transferred to a Whatman

® nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham Protran, GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Enzymatic, Portugal). Membranes were sectioned to allow the detection of multiple protein targets of distinct molecular weights, blocked with 5% skimmed milk or 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA, for γH2AX detection) and probed with specific primary and HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (described in

Supplementary Table S3). Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) or tubulin were used as loading controls. Signal was detected with ECL Amersham (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Enzymatic, Portugal) using the ChemiDoc

TM MP Imaging system (RRID:SCR_019037, Bio Rad Laboratories, Amadora, Portugal). Whole blot images are provided in

Supplementary Materials (Figure S3).

2.7. Wound Healing Assay

MDA-MB-231 (1 × 105 cells/well), IGROV-1 (6 × 104 cells/well) and PANC-1 (6 × 104 cells/well) were grown to confluence in 2-well silicone culture inserts (Ibidi), and a fixed-width wound was created in the cell monolayer by removing the insert. Cells were treated with DMSO or XGAc in serum-free media and images of the wound were captured at different time points (0, 6, 12, 24, 30 and 48 h) using an inverted NIKON TE 2000-U microscope from Nikon Instruments Inc. (Izasa, Carnaxide, Portugal) at 100× magnification with a DXM1200F digital camera (Nikon Instruments Inc.) and an NIS-Elements microscope imaging software (version 4; Nikon Instruments Inc.). Wound closure was calculated by subtracting the wound area (measured using Fiji Software) at the indicated time points of treatment to the wound area at the starting point.

2.8. Combination Therapy

Cells were treated with DMSO (control), the concentration of XGAc that causes 10% growth inhibition (IC

10, with no significant effect on cell growth) and/or increasing concentrations of olaparib for 48 h. The effect of combined treatments on cell proliferation was analyzed by SRB assay. Mutually nonexclusive combination index (C.I.) and dose reduction index (D.R.I.) were determined using CompuSyn software (RRID:SCR_022931, version 1.0, ComboSyn, Inc., Paramus, NJ, USA), as described [

21].

2.9. Statistical Analysis

The data presented as mean ± SEM values of at least three independent experiments were analyzed statistically using the GraphPad Prism (La Jolla, CA, USA; version 7.0) software. For comparison of multiple groups, statistical analysis relative to controls was performed using one-way or two-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Sidak’s or Dunnett’s multiple comparison tests. Statistical significance was set as * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 and **** p < 0.0001.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. XGAc Has a Potent Antiproliferative Effect on TNBC, Ovarian Cancer and PDAC Cells, Including Drug-Resistant Cancer Cells

The growth inhibitory activity of XGAc was determined by sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay in a panel of TNBC, ovarian cancer and PDAC cells and compared with olaparib, cisplatin (platinum agent mainly used in breast and ovarian cancer therapy) and gemcitabine (DNA-damaging agent used in pancreatic cancer therapy). The antiproliferative activity of the compounds was also assessed in non-tumorigenic foreskin fibroblasts (HFF-1) and breast (MCF12A) cells to check their selectivity to cancer cells.

In accordance with the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC

50) values, XGAc showed a potent growth inhibitory effect, ranging from 0.25 to 11.13 µM, in TNBC, ovarian cancer and PDAC cells, harbouring either wild-type (wt) or mutBRCA (

Figure 1B–D;

Supplementary Materials Table S1). Interestingly, regarding PDAC cells, a pronounced antiproliferative activity of XGAc was found in wtBRCA-expressing PDAC cells (IC

50 values of 0.25 to 0.87 µM), particularly when compared to mutBRCA2-expressing Capan-1 cells (IC

50 value of 11.13 ± 1.04 µM,

Figure 1D).

The effectiveness of XGAc against TNBC, ovarian and PDAC was further reinforced when compared to cisplatin, gemcitabine and olaparib (

Figure 1B–D). In particular, XGAc was shown to be much more effective than olaparib regardless of the BRCA status. In fact, olaparib only exhibited a similar antiproliferative effect to XGAc in mutBRCA2 Capan-1 cells (

Figure 1D). Importantly, conversely to the standard-of-care agents, XGAc showed selectivity to cancer cells, as demonstrated by its higher IC

50 values in the non-tumorigenic cells MCF12A (11.33 ± 1.95 µM;

Figure 1B) and HFF-1 (30.30 ± 4.19 µM;

Figure 1D).

The antiproliferative effect of XGAc in TNBC, ovarian cancer and PDAC cells was further evaluated by colony formation assay (

Figure 1E,F). Consistently, also in this assay, a pronounced growth inhibitory effect was observed for XGAc (IC

50 values of 2.39 ± 0.31 µM in MDA-MB-231, 3.34 ± 0.38 µM in IGROV-1 and 0.20 ± 0.03 µM in PANC-1).

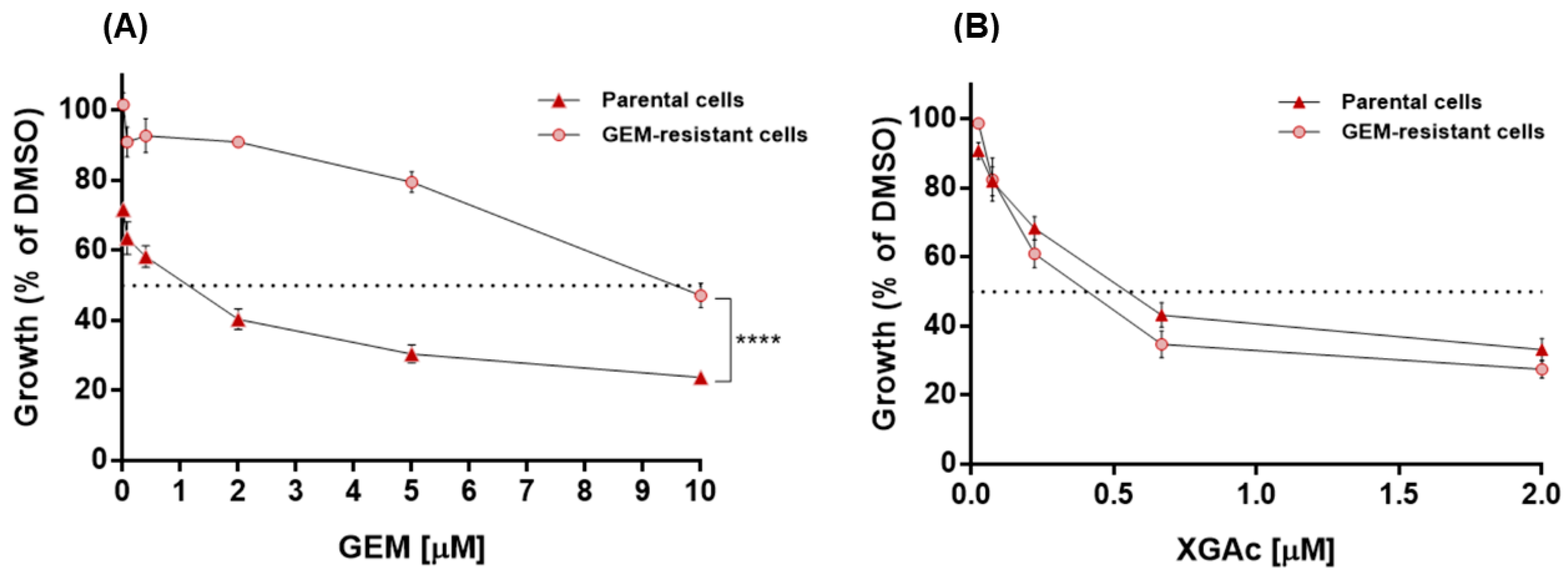

XGAc was also tested in gemcitabine (GEM)-resistant MIA-PaCa-2 cells, which showed no cross-resistance to XGAc. In fact, conversely to GEM (

Figure 2A), the antiproliferative effect of XGAc in GEM-resistant MIA-PaCa-2 cells (IC

50 value of 0.40 ± 0.05 µM) was similar to that obtained in non-resistant parental MIA-PaCa-2 cells (IC

50 value of 0.60 ± 0.07 µM,

Figure 2B). These results evidence the effectiveness of XGAc against drug-resistant cancer cells.

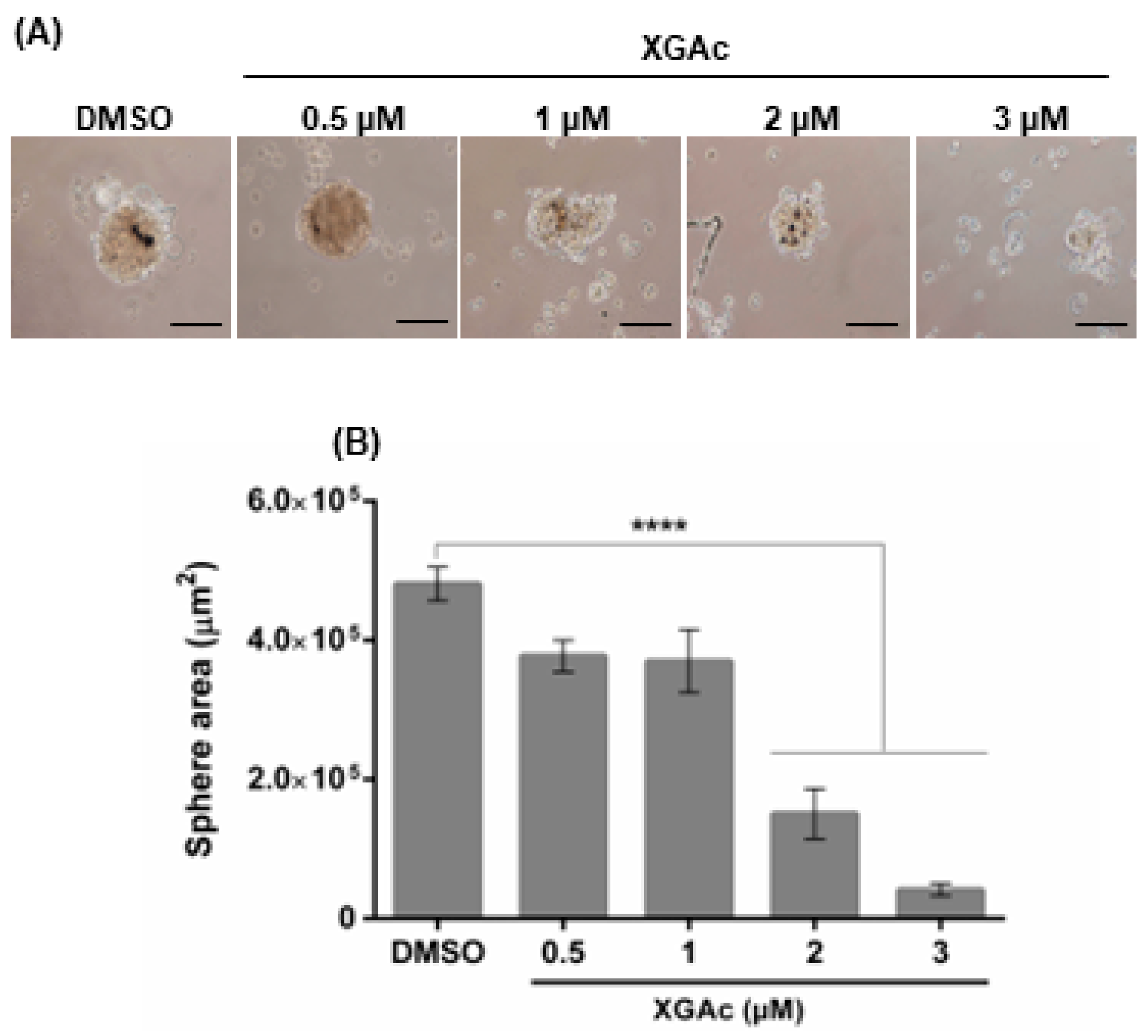

We further analyzed the effect of XGAc on the formation of a three-dimensional (3D) mammosphere model of the TNBC HCC1937 cells. As observed in

Figure 3, after 72 h of treatment with 2 and 3 µM of XGAc (added upon cell seeding), XGAc significantly inhibited spheroid formation (IC

50 value of 1.42 ± 0.22 µM). Altogether, these results indicated that XGAc inhibits the proliferation and clonogenic potential of cancer cells in 2D and 3D cancer cell models.

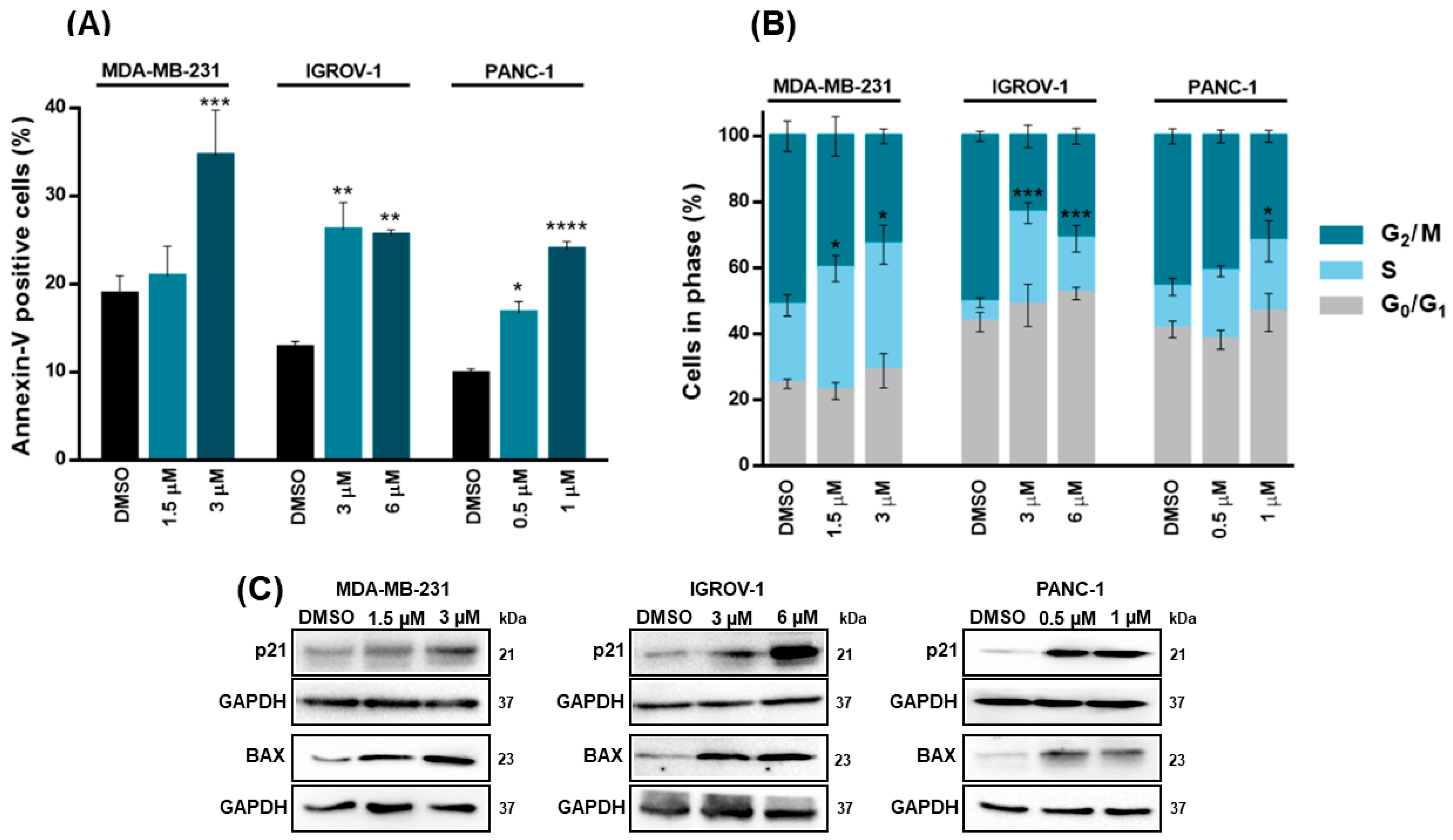

3.2. XGAc Induces Cell Cycle Arrest, Apoptosis and Genotoxicity, Inhibiting Crucial Players of Homologous Recombination DNA Repair Pathway in TNBC, Ovarian Cancer and PDAC Cells

We next verified that the growth inhibitory effect of XGAc went along with a significant induction of apoptosis (annexin V-positive cells) in MDA-MB-231 (at 3 µM), IGROV-1 (at 3 and 6 µM) and PANC-1 (at 0.5 and 1 µM) cells after 48 h of treatment (

Figure 4A). Additionally, after 48 h of treatment, XGAc significantly induced cell cycle arrest at S-phase in MDA-MB-231 (at 1.5 and 3 µM), IGROV-1 (at 3 and 6 µM) and PANC-1 (at 1 µM) (

Figure 4B). Consistently, 48 h treatment with XGAc increased the protein expression levels of cell cycle and proapoptotic regulators, p21 and BAX, respectively, in MDA-MB-231, IGROV-1 and PANC-1 (

Figure 4C).

In fact, several DNA-targeting agents, such as gemcitabine and irinotecan (a topoisomerase I inhibitor clinically effective against distinct cancers), have shown S-phase-specific cytotoxicity [

22,

23]. By promoting S-phase arrest, these compounds impair DNA replication [

24]. Consistently, previous evidence has indicated that xanthone derivatives may interact with DNA through intercalation, suppressing its replication in cancer cells [

11,

12].

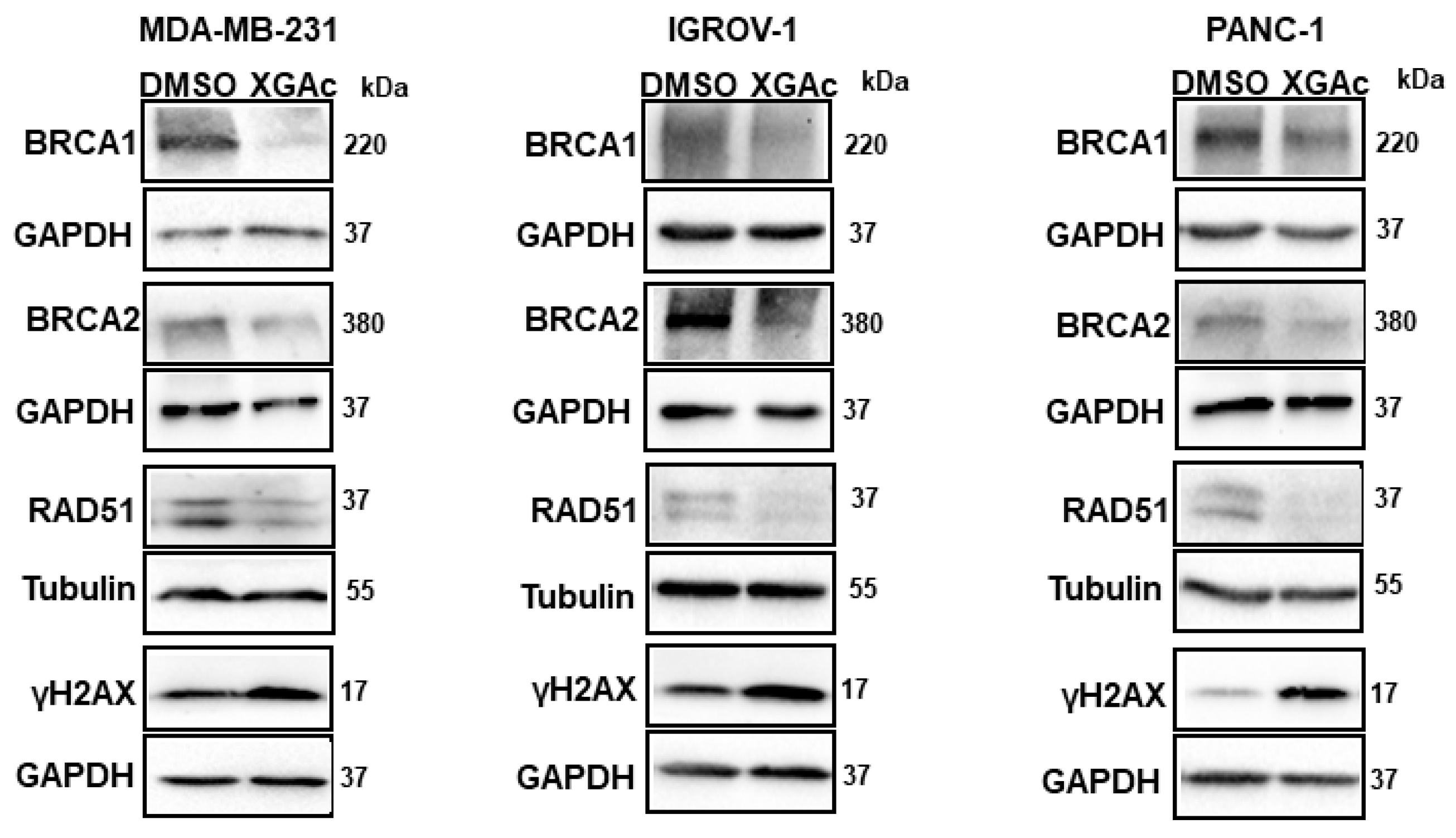

Since XGAc suppresses DNA replication in cancer cells by inducing cell cycle arrest in the S-phase, the genotoxic potential of XGAc was evaluated. Accordingly, after 48 h of treatment, XGAc increased the protein expression levels of the phosphorylated histone γH2AX (

Figure 5), which is a sensitive marker of DSBs. Altogether, these results indicated that XGAc promoted replication-associated DSBs, stimulating cancer cell death due to unrepaired DNA damage. In conformity with this, it was verified that XGAc could interfere with the expression levels of key proteins in homologous recombination DNA repair, a high-fidelity DNA repair pathway that predominates in the S- and G2-phases of the cell cycle to repair DNA gaps, DSBs and DNA interstrand crosslinks, also providing critical support for DNA replication [

25]. In fact, XGAc decreased the protein expression levels of BRCA1, BRCA2 and RAD51 in TNBC (MDA-MB-231 cells; at 3 µM), ovarian cancer (IGROV-1 cells; at 6 µM) and PDAC (PANC-1 cells; at 1 µM) cells after 48 h of treatment (

Figure 5).

Particularly, the downregulation of RAD51 by XGAc is highly relevant, since RAD51 is commonly overexpressed in several human malignancies, which is correlated with poor patient survival [

26]. In fact, as observed with XGAc, RAD51 inhibitors have been described for their ability to impair human cancer cell growth, induce cell cycle arrest in S-phase and increase the expression levels of γH2AX, also sensitizing cancer cells to other DNA-damaging agents [

27].

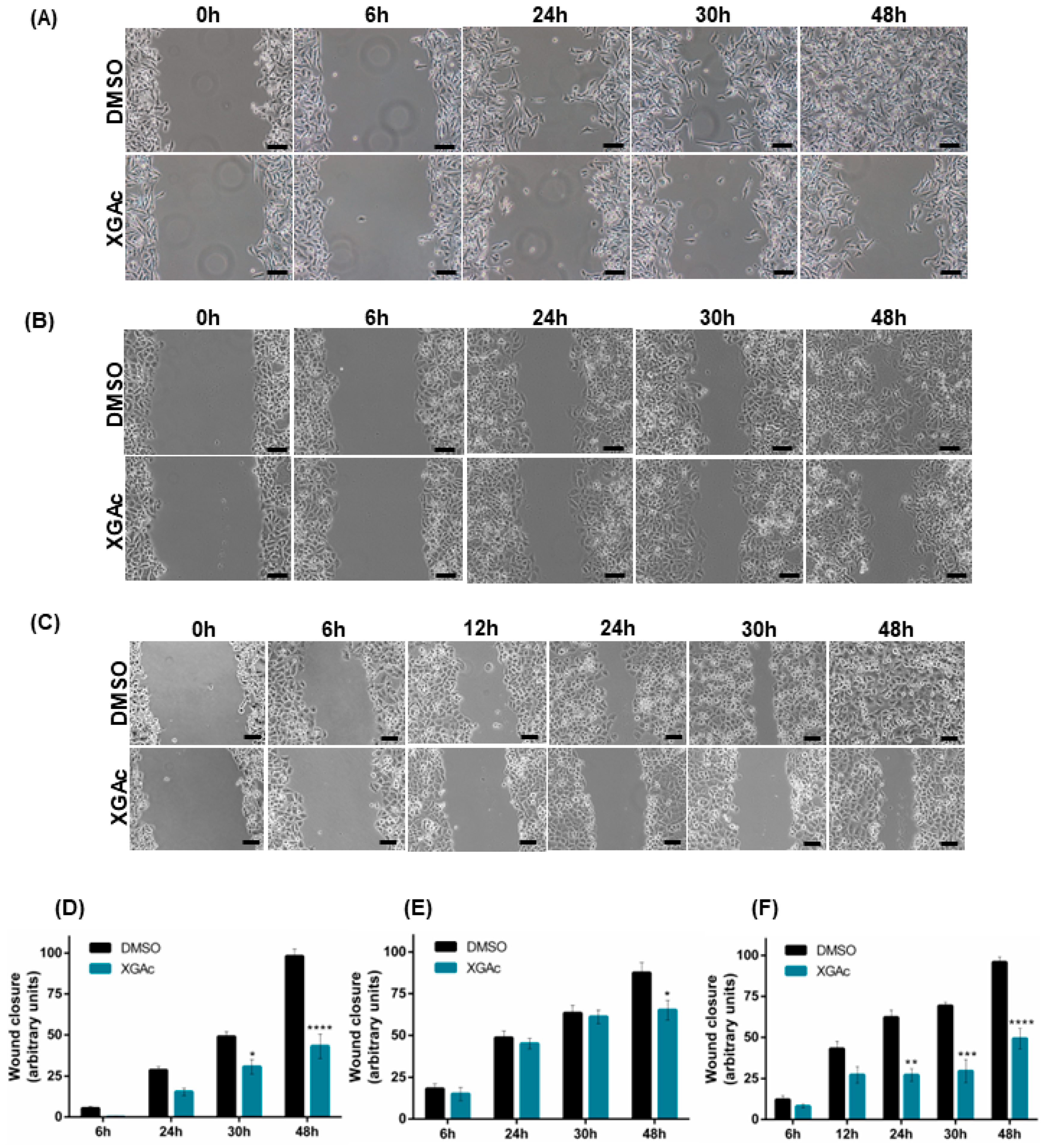

3.3. XGAc Inhibits the Migration of TNBC, Ovarian Cancer and PDAC Cells

To evaluate the antimigratory activity of XGAc in TNBC, ovarian cancer and PDAC cells, a wound healing assay was performed. It was observed that 47 nM, 200 nM and 16 nM of XGAc (corresponding to the IC

10 concentration of XGAc in MDA-MB-231, IGROV-1 and PANC-1, respectively) significantly inhibited cancer cell migration after 24 h (in PANC-1), 30 h (in MDA-MB-231 and PANC-1) and 48 h (in MDA-MB-231, IGROV-1 and PANC-1) of treatment (

Figure 6). These results suggested that XGAc suppresses cancer cell motility, potentially preventing tumor dissemination.

Interestingly, in conformity with our work, it was previously reported that the naturally occurring xanthone C-glycoside mangiferin also inhibited the proliferation, migration, and invasion of distinct cancers [

28].

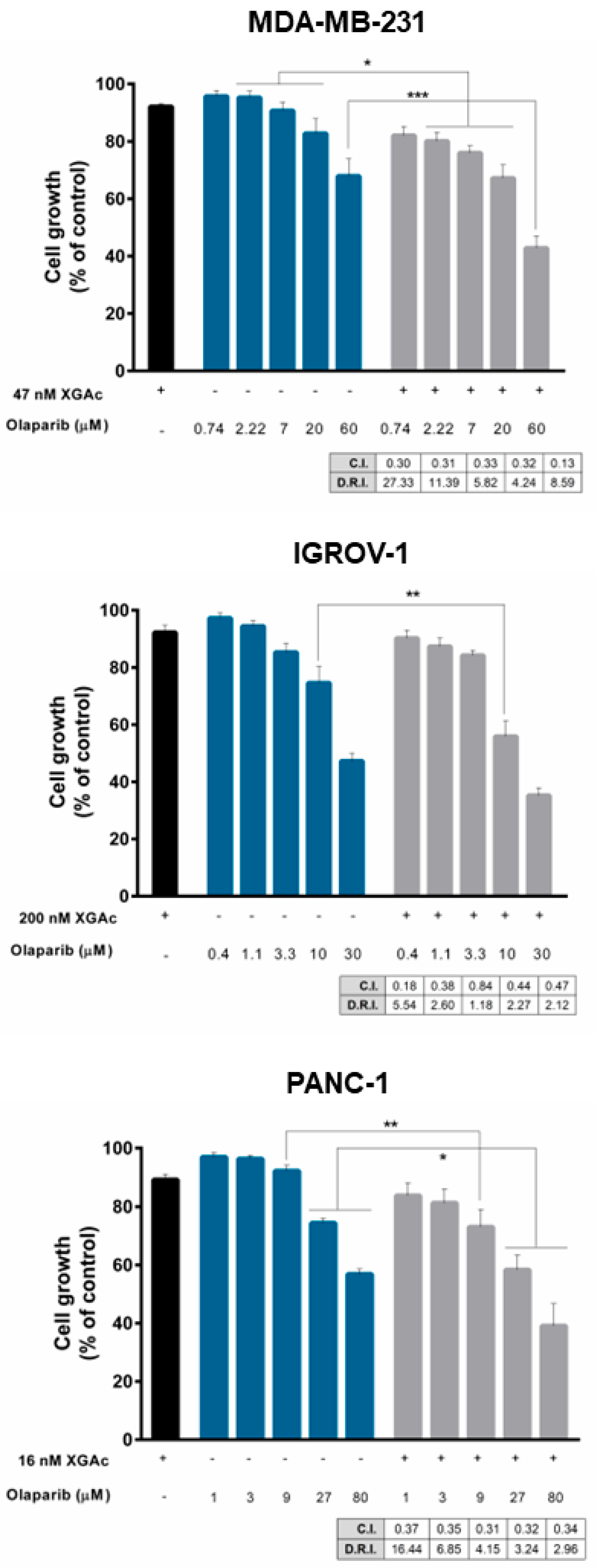

3.4. XGAc Sensitizes TNBC, Ovarian Cancer and PDAC Cells to Olaparib

Since XGAc negatively impacted DNA repair including homologous recombination regulators in cancer cells, we investigated the potential synergistic combination of XGAc with another DNA repair-inhibiting agent, olaparib, that compromises DNA single-strand break repair, affecting DNA repair pathways such as base excision repair and non-homologous end joining. For that, a single concentration of XGAc, with no significant effect on cancer cell growth (IC

10), and a concentration range of olaparib were tested in cancer cells. The results revealed that XGAc enhanced the growth inhibitory activity of olaparib when compared to olaparib alone, either in wt or mutBRCA cancer cells (

Figure 7). The combination index (C.I.) and dose reduction index (D.R.I.) values were determined by multiple drug-effect analyses for each combination, showing synergistic effects between XGAc and olaparib for all the combinations tested (C.I. < 1), and a marked reduction in the effective dose of olaparib (

Figure 7). Particularly, in MDA-MB-231, the synergistic combination of 47 nM XGAc and 0.74 µM olaparib (C.I. of 0.30) was associated with 27.33-fold reduction of the effective dose of olaparib; in IGROV-1, a 5.54-fold reduction was achieved with 200 nM XGAc and 0.4 µM olaparib (C.I. of 0.18); and in PANC-1, the 16 nM XGAc and 1 µM olaparib synergistic combination (C.I. of 0.37) caused a 16.44-fold reduction of the effective dose of olaparib (

Figure 7).

The clinical use of PARPis in combination with DNA-damaging agents is limited by the more-than-addictive cytotoxicity [

29]. However, XGAc exhibited synergistic effects with olaparib, which may be explained by a synthetic lethality effect involving an inhibition of homologous recombination DNA repair by XGAc and of single-strand break repair by olaparib. In fact, the mutual inhibition of different DNA repair pathways significantly compromises cell survival [

30]. Consistently, previous works have shown synergistic effects between olaparib and novel homologous recombination DNA repair inhibitors capable of inducing a BRCAness phenotype, namely, in PDAC cells [

31,

32,

33].

The synergism with XGAc will reduce the effective dose of olaparib and, subsequently, its undesirable toxicity. Also, since resistance to olaparib is a major clinical concern, the combination with XGAc will (re)sensitize cancer cells to its cytotoxic effect. Importantly, this synergistic combination may also be applied to homologous recombination-proficient patients since XGAc enhanced the growth inhibitory activity of olaparib in wtBRCA cancer cells, which will extend the population of cancer patients that may respond to this targeted anticancer drug. In summary, these findings indicate that XGAc may enhance the sensitivity of cancer cells to olaparib by potentially inhibiting homologous recombination.

Despite its clinical approval, the limitations of olaparib are known, particularly due to its inability to trigger synthetic lethality in homologous recombination-proficient patients. The ability of XGAc to induce synthetic lethality when combined with olaparib, increasing its efficacy, and extending the population of patients that may benefit from this drug, has high clinical relevance and is worthy of this study. Although it has not been studied in this work, the mechanism of action of this compound leads us to also predict promising synergistic effects of XGAc with other chemotherapeutic agents, such as cisplatin and gemcitabine.

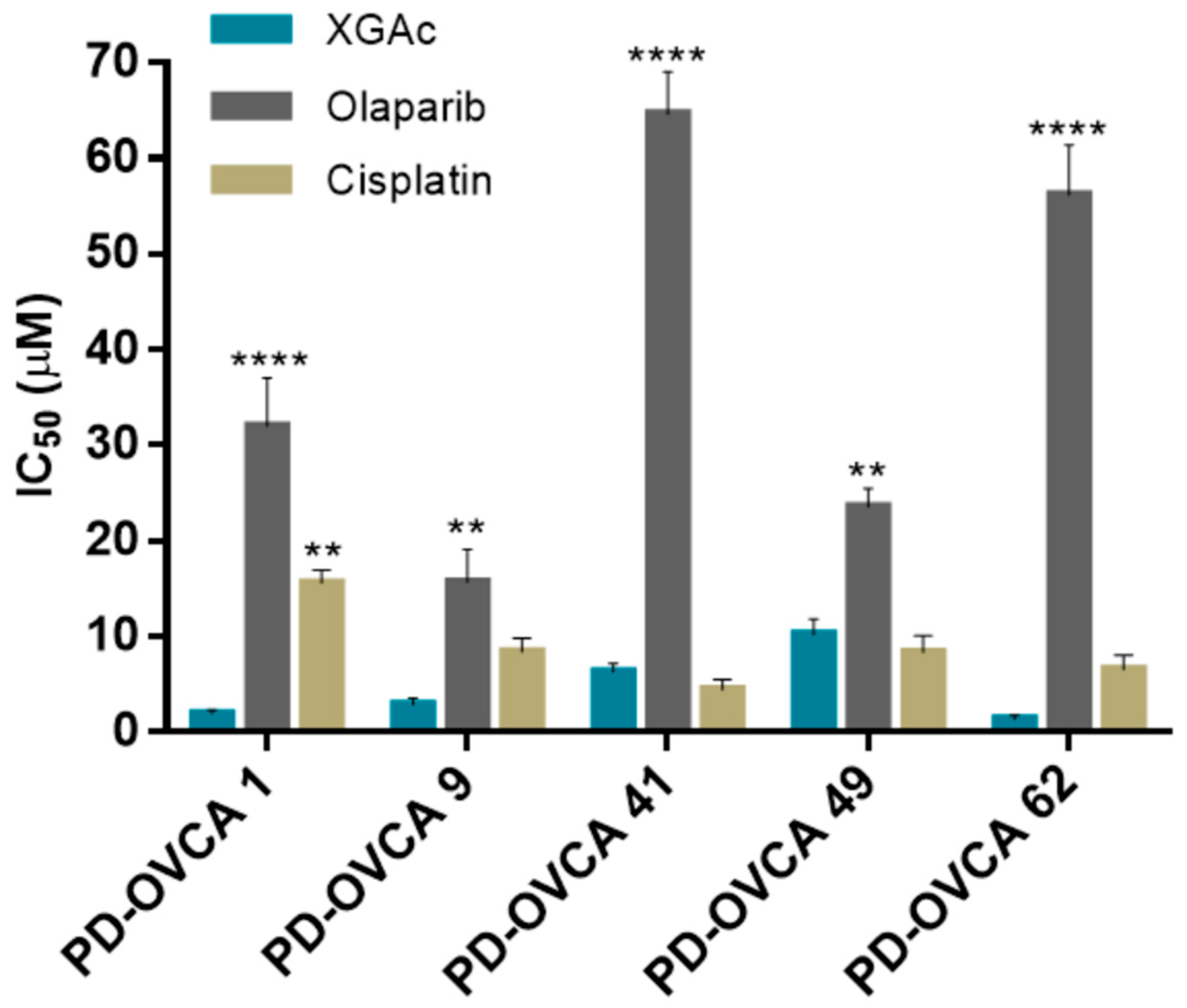

3.5. XGAc Induces Cytotoxicity in Patient-Derived Ovarian Cancer Cells

The cytotoxic effect of XGAc was further evaluated in patient-derived ovarian cancer cells harbouring wt or mut

BRCA1 (

Supplementary Materials, Table S2) by MTS assay. Consistently with our previous results (

Figure 1), regardless of

BRCA1 status, XGAc was much more effective than olaparib in reducing the cell viability of all patient-derived ovarian cancer cells (

Figure 8). Notably, XGAc was also more effective than cisplatin in platinum-resistant patient-derived PD-OVCA 1 cells harbouring a pathogenic mut

BRCA1 (

Figure 8;

Supplementary Materials, Table S2).

As observed in GEM-resistant MIA-PaCa-2 cells (

Figure 2), the promising cytotoxicity obtained with XGAc in PD-OVCA 1 (post-chemo platinum-resistant patient-derived ovarian cancer cells) indicated that these cells showed no cross-resistance to XGAc (

Figure 8). PD-OVCA 1 was derived from a patient that received different treatments based on carboplatin, followed by gemcitabine and topotecan, and finally mitoxantrone, developing post-chemo platinum resistance [

17]. In fact, drug effectiveness is often limited by the emergence of cancer cell resistance [

34]. However, these results corroborated the potential of XGAc against drug-resistant cancer cells.

Altogether, these results confirmed the efficacy of XGAc against both wt and mutBRCA1 cancer cell lines. In fact, the higher cytotoxic effect of XGAc could be observed in mut

BRCA1 PD-OVCA 1 and wt

BRCA1 PD-OVCA 62 cells (

Figure 8).

It is worth noting that the low sensitivity of PD-OVCA 41 to olaparib may be related to the presence, in this patient-derived cell line, of a benign missense mutBRCA1. On the other hand, the notable sensitivity of wtBRCA1 PD-OVCA 49 to olaparib suggests some homologous recombination impairment in this cell line, namely, in non-BRCA genes (BRCAness phenotype); however, we do not have further information to confirm this hypothesis.

4. Conclusions

This work reports the promising antitumor activity of XGAc in TNBC, ovarian and PDAC cancer cells. Herein, we demonstrated that XGAc decreased cancer cell proliferation, viability, and motility, exhibiting low cytotoxicity against normal cells, and being much more effective than olaparib regardless of BRCA status. Importantly, XGAc was shown to be highly effective in drug-resistant cancer cells, suggesting its great therapeutic relevance in resistant and hard-to-treat cancers.

PARPis are currently on the frontline of targeted therapy for mutBRCA patients. However, its efficacy in monotherapy is limited to mutBRCA cancer patients and cancer cells frequently become resistant to this therapy by restoring or retaining a residual DNA repair machinery. Thus, the development of strategies that improve the therapeutic potential of PARPis and allow the overcoming of resistance to these agents, namely, through combination therapy is of great relevance. Following this premise, the inhibition of homologous recombination DNA repair constitutes a promising anticancer strategy particularly to (re)sensitize cancer cells to DNA-damaging agents. Herein, XGAc was identified as a genotoxic xanthone derivative, promoting replication-associated DSBs in cancer cells and triggering apoptotic cancer cell death by DNA repair inhibition. XGAc may induce synthetic lethality effects with PARPis that negatively impact single-strand break repair. In fact, XGAc sensitized both wt and mutBRCA cancer cells to the effect of olaparib, extending the population of cancer patients that may respond to this targeted therapy while reducing its effective dose and subsequent toxic side effects.

In conclusion, this work supports the promising application of XGAc in the treatment of hard-to-treat cancers, either alone or in combination with olaparib. Importantly, these results pave the way to future works that may explore acetylated xanthonosides as anticancer agents, particularly by their DNA-targeting ability. Moreover, it encourages combination therapy to induce synthetic lethality in cancer cells, sensitizing them to the standard-of-care therapy.