Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer and the third cause of cancer death in the world, while intestinal microbiota is a community of microbes living in human intestine that can potentially impact human health in many ways. Accumulating evidence suggests that intestinal microbiota, especially that from the intestinal bacteria, play a key role in the CRC development; therefore, identification of bacteria involved in CRC development can provide new targets for the CRC diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. Over the past decade, there have been considerable advances in applying 16S rDNA sequencing data to verify associated intestinal bacteria in CRC patients; however, due to variations of individual and environment factors, these results seem to be inconsistent. In this review, we scrutinized the previous 16S rDNA sequencing data of intestinal bacteria from CRC patients, and identified twelve genera that are specifically enriched in the tumor microenvironment. We have focused on their relationship with the CRC development, and shown that some bacteria could promote CRC development, acting as foes, while others could inhibit CRC development, serving as friends, for human health. Finally, we highlighted their potential applications for the CRC diagnosis, prevention, and treatment.

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the collective term used for the colon, rectal and anal cancer, and is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer and the third cause of cancer death in the world. It was responsible for over 880,792 deaths and 1,849,518 new cases worldwide in 2018 [1]. As a well-known multi-factorial disease, CRC may stem from different individual genetic background, lifestyle, and environmental factors (such as diet and drugs), and from dynamic imbalance between intestinal microbiota and host immune system [2,3,4,5,6,7,8].

Intestinal microbiota is a community of microbes that live in human intestine [9]. It has been considered as an “invisible organ” of human body [10], and contains at least 150 times more genes in total than the host genome [11]. As an “invisible organ”, intestinal microbiota or their metabolites can, in fact, significantly impact human health, causing diseases such as obesity [12], diabetes [13], fatty liver disease [14], hypertension and cardiovascular disease [15], CRC [16], etc.

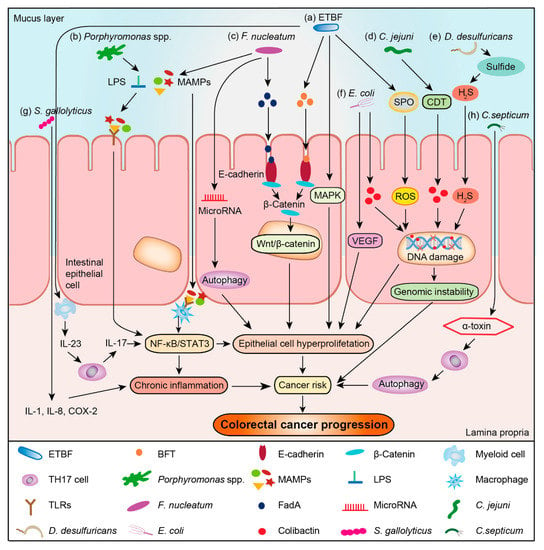

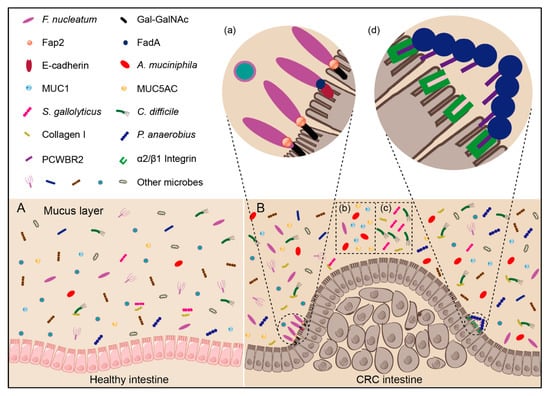

The composition and diversity of intestinal microbiota are influenced by both individual factors, such as age, sex, race, immune system, and environmental factors, including dietary habits and medication usage [17]. More than 1000 microbial species colonize the human intestine [18], with bacteria accounting for about 95% of the microbe population [18]. The dominant bacterial phyla in healthy individuals are Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Actinobacteria, with Proteobacteria and Verrucomicrobia also existing in lower numbers [17]. However, in CRC patients, intestinal bacteria appear to show different profiles. In fact, there is abundant evidence to demonstrate that the composition of intestinal bacteria can potentially contribute to cancer development [7,19,20,21,22], and some intestinal bacteria involved in colorectal carcinogenesis can be described by a “driver–passenger” model [23]. The “driver” bacteria are those causing DNA damage in intestinal epithelial cell thus contributing to the initiation of CRC and formation of a tumor microenvironment that comprises cancer cells, normal cells, and the extracellular matrix they secrete [23]. These bacteria include Bacteroides fragili [24], Escherichia coli [24] and Campylobacter jejuni [25], which can secrete B. fragilis toxin (BFT), colibactin, and cytolethal distending toxin (CDT), respectively, to attack intestinal epithelial cells and cause DNA damage. The “passenger” bacteria, on the other hand, are those that are more adapted to the tumor microenvironment, occupying the niche and being able to replace the “driver” bacteria, with most of them either promoting or inhibiting the CRC development [23]. For example, Fusobacterium nucleatum can activate the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, stimulate cancer cell growth, and promote CRC development [26]; however, Akkermansia muciniphila can instead enhance the efficacy of programmed death 1 (PD-1) based immunotherapy against CRC [27]. Therefore, identifying bacteria enriched in the tumor microenvironment are important for treatment of CRC. Despite extensive research on intestinal bacteria in patients with CRC, still a large number of CRC-associated bacteria have not yet been identified. Due to the distinct individual and environment factors, these studies on CRC-associated bacteria sometimes suffer from inconsistent results. Thus, a systematic analysis of CRC-associated bacteria is required.

In this review, via analyzing and scrutinizing the abundant 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) sequencing studies of intestinal bacteria in CRC patients, we conclude that twelve genera were significantly enriched in the CRC patients or tissues. We then discuss these twelve genera in detail, including their roles in the CRC development, the mechanisms for their enrichment in tumor microenvironment of CRC patients, and their application values in the CRC treatment. Our aim is to highlight new ideas for diagnosis (such as validating bacterial biomarkers), prevention, and treatment (via inhibiting carcinogenic bacteria and supplementing probiotics) of CRC.

3. Conclusions and Prospects

If the battle between human and CRC is a “prolonged war”, the tumor microenvironment would be the front line of the battlefield. Are the bacteria that enriched in tumor microenvironment foes or friends? Identification and clarification of the relationship between these bacteria and CRC development are extremely important.

In this review, we focused on the analyses of twelve genera that are enriched in the tumor microenvironment of CRC patients and explored their relationship with CRC development. These bacteria can be divided into three groups: (1) Direct carcinogenic bacteria, like F. nucleatum, S. gallolyticus, C. difficile, and P. anaerobius. Scientists have proposed the potential mechanism of their enrichment in CRC microenvironment, and found that these bacteria can directly participate CRC development; (2) Indirect carcinogenic bacteria, like enterotoxigenic B. fragile and E. coli. They act indirectly to impact CRC pathogenesis via secondary metabolites, or induction of immune changes in the tumor microenvironment. B. fragile and E. coli are such bacteria that are not specifically enriched in the tumor microenvironment, but the toxins they produced can promote the development of CRC; (3) Anticancer probiotics, like A. muciniphila. They do not promote development of CRC and are beneficial to human health.

We conclude that there are three mechanisms for bacteria to affect CRC development: (1) They stimulate the immune system and thereby trigger chronic inflammation. Processes in chronic inflammation might cause or facilitate epithelial cell hyper-proliferation, oncogene activation, and angiogenesis; (2) They directly or indirectly damage host DNA. Occasionally, DNA damage surpasses the host cell repair capacity, and such incomplete DNA repair would result in mutagenesis and genomic instability, leading to CRC initiation and development; (3) They affect cell proliferation and cellular apoptosis through activation of NF-κB or β-catenin signaling. This could promote tumor development by regulating the expression of anti-apoptotic, cell cycle or pro-inflammatory proteins. Bacteria could bind E-cadherin on the colonic epithelial cells and triggered β-catenin activation, resulting in dysregulated cell growth to acquire stem cell–like qualities.

The bacteria enriched in tumor microenvironment have many known or potential application prospects for the CRC diagnosis, prevention, and treatment, including: (1) For strains enriched in the intestines of CRC patients, they can be regarded as biomarkers, and it is possible to develop a diagnostic method for CRC, such as qPCR and other cheap and fast methods to detect the abundance of these bacteria in the patients’ feces to screen for high-risk CRC population; (2) For carcinogenic bacteria enriched in CRC, drugs against them can be developed to reduce its abundance in CRC patients, thus inhibiting the CRC development; (3) For probiotics that are colonized in the tumor microenvironment, one can increase their abundance in the intestines with oral supplements to improve CRC patients’ health. These can be enclosed and supplied in a specific CRC drug delivery vehicle to target the tumor site of CRC, release cancer treatment drugs, and exert their probiotic effect.

In the future, more research on the CRC and intestinal bacteria, standardized analysis, and CRC mouse models are required to better understand how these bacteria can be used to efficiently prevent or treat CRC. If we can clearly understand the relationship between these bacteria and CRC development, we can also use bacteriophages, targeted antibiotics or even develop new vaccines to fight against these bacteria to develop new strategies for the CRC treatment.

Author Contributions

S.X. and W.Y. wrote the manuscript and added valuable insights into the manuscript. Y.Z. coordinated to write the manuscript. Q.L. participated in drafting the figures. Y.Y. searched for references. J.H. developed the concept, designed the thought and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant 2018YFD0500204), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 31970074 and 31770087), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grants 2662017PY112).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Keefe, S.J. Diet, microorganisms and their metabolites, and colon cancer. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 13, 691–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, J.; Sinha, R.; Pei, Z.; Dominianni, C.; Wu, J.; Shi, J.; Goedert, J.J.; Hayes, R.B.; Yang, L. Human gut microbiome and risk for colorectal cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2013, 105, 1907–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M’Koma, A.E. Inflammatory bowel disease: An expanding global health problem. Clin. Med. Insights Gastroenterol. 2013, 6, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhiqin, W.; Palaniappan, S.; Raja Ali, R.A. Inflammatory bowel disease-related colorectal cancer in the Asia-Pacific region: Past, present, and future. Intest. Res. 2014, 12, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, C.; Medzhitov, R. Interactions between the host innate immune system and microbes in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2011, 140, 1729–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, J.C.; Gharaibeh, R.Z.; Muhlbauer, M.; Perez-Chanona, E.; Uronis, J.M.; McCafferty, J.; Fodor, A.A.; Jobin, C. Microbial genomic analysis reveals the essential role of inflammation in bacteria-induced colorectal cancer. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Cao, Q.; Cheng, J. Review of inflammatory bowel disease in China. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 296470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J.I. Honor thy gut symbionts redux. Science 2012, 336, 1251–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, A.M.; Shanahan, F. The gut flora as a forgotten organ. EMBO Rep. 2006, 7, 688–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Li, R.; Raes, J.; Arumugam, M.; Burgdorf, K.S.; Manichanh, C.; Nielsen, T.; Pons, N.; Levenez, F.; Yamada, T.; et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature 2010, 464, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komaroff, A.L. The microbiome and risk for obesity and diabetes. JAMA 2017, 317, 355–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, A.; Molinaro, A.; Stahlman, M.; Khan, M.T.; Schmidt, C.; Manneras-Holm, L.; Wu, H.; Carreras, A.; Jeong, H.; Olofsson, L.E.; et al. Microbially produced imidazole propionate impairs insulin signaling through mTORC1. Cell 2018, 175, 947–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Chen, C.; Cui, J.; Lu, J.; Yan, C.; Wei, X.; Zhao, X.; Li, N.; Li, S.; Xue, G.; et al. Fatty liver disease caused by high-alcohol-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 675–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilck, N.; Matus, M.G.; Kearney, S.M.; Olesen, S.W.; Forslund, K.; Bartolomaeus, H.; Haase, S.; Mahler, A.; Balogh, A.; Marko, L.; et al. Salt-responsive gut commensal modulates TH17 axis and disease. Nature 2017, 551, 585–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.; Sears, C.L. Impact of the gut microbiome on the genome and epigenome of colon epithelial cells: Contributions to colorectal cancer development. Genome Med. 2019, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, H.J.; Scott, K.P.; Louis, P.; Duncan, S.H. The role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 9, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajilic-Stojanovic, M.; de Vos, W.M. The first 1000 cultured species of the human gastrointestinal microbiota. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 38, 996–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellarin, M.; Warren, R.L.; Freeman, J.D.; Dreolini, L.; Krzywinski, M.; Strauss, J.; Barnes, R.; Watson, P.; Allen-Vercoe, E.; Moore, R.A.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum infection is prevalent in human colorectal carcinoma. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostic, A.D.; Chun, E.; Robertson, L.; Glickman, J.N.; Gallini, C.A.; Michaud, M.; Clancy, T.E.; Chung, D.C.; Lochhead, P.; Hold, G.L.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum potentiates intestinal tumorigenesis and modulates the tumor-immune microenvironment. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 14, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira-Pascual, L.; Cabrera-Rubio, R.; Ocon, S.; Costales, P.; Parra, A.; Suarez, A.; Moris, F.; Rodrigo, L.; Mira, A.; Collado, M.C. Microbial mucosal colonic shifts associated with the development of colorectal cancer reveal the presence of different bacterial and archaeal biomarkers. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 50, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Dong, L.; Wang, T.; Zhang, M.; Hua, W.; Zhang, C.; Pang, X.; Chen, M.; Su, M.; Qiu, Y.; et al. Structural shifts of gut microbiota as surrogate endpoints for monitoring host health changes induced by carcinogen exposure. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2010, 73, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjalsma, H.; Boleij, A.; Marchesi, J.R.; Dutilh, B.E. A bacterial driver-passenger model for colorectal cancer: Beyond the usual suspects. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejea, C.M.; Fathi, P.; Craig, J.M.; Boleij, A.; Taddese, R.; Geis, A.L.; Wu, X.; DeStefano Shields, C.E.; Hechenbleikner, E.M.; Huso, D.L.; et al. Patients with familial adenomatous polyposis harbor colonic biofilms containing tumorigenic bacteria. Science 2018, 359, 592–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, B.J.; Vignard, J.; Mirey, G. Cytolethal Distending Toxin Subunit B: A review of structure-function relationship. Toxins (Basel) 2019, 11, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, M.R.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Hao, Y.; Cai, G.; Han, Y.W. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal carcinogenesis by modulating E-cadherin/β-catenin signaling via its FadA adhesin. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 14, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routy, B.; Le Chatelier, E.; Derosa, L.; Duong, C.P.M.; Alou, M.T.; Daillere, R.; Fluckiger, A.; Messaoudene, M.; Rauber, C.; Roberti, M.P.; et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science 2018, 359, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chang, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, R.; Hu, C.; Jia, W. Altered intestinal microbiota associated with colorectal cancer. Front. Med. 2019, 13, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffarian, A.; Mulet, C.; Regnault, B.; Amiot, A.; Tran-Van-Nhieu, J.; Ravel, J.; Sobhani, I.; Sansonetti, P.J.; Pedron, T. Crypt- and mucosa-associated core microbiotas in humans and their alteration in colon cancer patients. Microbiology 2019, 10, e01315–e01319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Kong, C.; Huang, L.; Li, H.; Qu, X.; Liu, Z.; Lan, P.; Wang, J.; Qin, H. Mucosa-associated microbiota signature in colorectal cancer. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 36, 2073–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.M.; Jesus, E.C.; Lopes, A.; Aguiar, S., Jr.; Begnami, M.D.; Rocha, R.M.; Carpinetti, P.A.; Camargo, A.A.; Hoffmann, C.; Freitas, H.C.; et al. Tissue-associated bacterial alterations in rectal carcinoma patients revealed by 16S rRNA community profiling. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2016, 6, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allali, I.; Boukhatem, N.; Bouguenouch, L.; Hardi, H.; Boudouaya, H.A.; Cadenas, M.B.; Ouldim, K.; Amzazi, S.; Azcarate-Peril, M.A.; Ghazal, H. Gut microbiome of Moroccan colorectal cancer patients. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2018, 207, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemer, B.; Lynch, D.B.; Brown, J.M.; Jeffery, I.B.; Ryan, F.J.; Claesson, M.J.; O’Riordain, M.; Shanahan, F.; O’Toole, P.W. Tumour-associated and non-tumour-associated microbiota in colorectal cancer. Gut 2017, 66, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, T.L.; Manter, D.K.; Sheflin, A.M.; Barnett, B.A.; Heuberger, A.L.; Ryan, E.P. Stool microbiome and metabolome differences between colorectal cancer patients and healthy adults. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Cai, G.; Qiu, Y.; Fei, N.; Zhang, M.; Pang, X.; Jia, W.; Cai, S.; Zhao, L. Structural segregation of gut microbiota between colorectal cancer patients and healthy volunteers. ISME J. 2012, 6, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Guo, B.; Gao, R.; Zhu, Q.; Qin, H. Microbiota disbiosis is associated with colorectal cancer. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allali, I.; Delgado, S.; Marron, P.I.; Astudillo, A.; Yeh, J.J.; Ghazal, H.; Amzazi, S.; Keku, T.; Azcarate-Peril, M.A. Gut microbiome compositional and functional differences between tumor and non-tumor adjacent tissues from cohorts from the US and Spain. Gut Microbes 2015, 6, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Yang, X.; Zhang, R.; Li, J.; Xiao, X.; Hu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, F.; Lu, N.; Wang, Z.; et al. Dysbiosis signature of fecal microbiota in colorectal cancer patients. Microb. Ecol. 2013, 66, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Fan, H.; Tang, X.; Zhai, H.; Zhang, Z. Diversified pattern of the human colorectal cancer microbiome. Gut Pathog. 2013, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, O.; Lahti, L.; Kokkola, A.; Karla, T.; Tikkanen, M.; Ehsan, H.; Carpelan-Holmstrom, M.; Koskensalo, S.; Bohling, T.; Rautelin, H.; et al. Stool microbiota composition differs in patients with stomach, colon, and rectal neoplasms. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2018, 63, 2950–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhani, I.; Tap, J.; Roudot-Thoraval, F.; Roperch, J.P.; Letulle, S.; Langella, P.; Corthier, G.; Tran Van Nhieu, J.; Furet, J.P. Microbial dysbiosis in colorectal cancer (CRC) patients. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Liu, F.; Ling, Z.; Tong, X.; Xiang, C. Human intestinal lumen and mucosa-associated microbiota in patients with colorectal cancer. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e39743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostic, A.D.; Gevers, D.; Pedamallu, C.S.; Michaud, M.; Duke, F.; Earl, A.M.; Ojesina, A.I.; Jung, J.; Bass, A.J.; Tabernero, J.; et al. Genomic analysis identifies association of Fusobacterium with colorectal carcinoma. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Carvalho, A.C.; de Mattos Pereira, L.; Datorre, J.G.; Dos Santos, W.; Berardinelli, G.N.; Matsushita, M.M.; Oliveira, M.A.; Duraes, R.O.; Guimaraes, D.P.; Reis, R.M. Microbiota profile and impact of Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal cancer patients of Barretos cancer hospital. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Misra, B.B.; Liang, L.; Bi, D.; Weng, W.; Wu, W.; Cai, S.; Qin, H.; Goel, A.; Li, X.; et al. Integrated microbiome and metabolome analysis reveals a novel interplay between commensal bacteria and metabolites in colorectal cancer. Theranostics 2019, 9, 4101–4114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Jiang, B. Analysis of mucosa-associated microbiota in colorectal cancer. Med. Sci. Monit. 2017, 23, 4422–4430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Song, Q.; Tang, X.; Liang, X.; Fan, H.; Peng, H.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, Z. Co-occurrence of driver and passenger bacteria in human colorectal cancer. Gut Pathog. 2014, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Donaldson, G.P.; Mikulski, Z.; Boyajian, S.; Ley, K.; Mazmanian, S.K. Bacterial colonization factors control specificity and stability of the gut microbiota. Nature 2013, 501, 426–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, G.P.; Ladinsky, M.S.; Yu, K.B.; Sanders, J.G.; Yoo, B.B.; Chou, W.C.; Conner, M.E.; Earl, A.M.; Knight, R.; Bjorkman, P.J.; et al. Gut microbiota utilize immunoglobulin A for mucosal colonization. Science 2018, 360, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiryaev, S.A.; Remacle, A.G.; Cieplak, P.; Strongin, A.Y. Peptide sequence region that is essential for the interactions of the enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis metalloproteinase II with E-cadherin. J. Proteolysis 2014, 1, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Abed, J.; Emgard, J.E.; Zamir, G.; Faroja, M.; Almogy, G.; Grenov, A.; Sol, A.; Naor, R.; Pikarsky, E.; Atlan, K.A.; et al. Fap2 mediates Fusobacterium nucleatum colorectal adenocarcinoma enrichment by binding to tumor-expressed Gal-GalNAc. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 20, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, J.C.; Bresalier, R.S. Mucins and mucin binding proteins in colorectal cancer. Cancer Metastasis. Rev. 2004, 23, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.M.; Escher, U.; Mousavi, S.; Tegtmeyer, N.; Boehm, M.; Backert, S.; Bereswill, S.; Heimesaat, M.M. Immunopathological properties of the Campylobacter jejuni flagellins and the adhesin CadF as assessed in a clinical murine infection model. Gut Pathog. 2019, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konkel, M.E.; Larson, C.L.; Flanagan, R.C. Campylobacter jejuni FlpA binds fibronectin and is required for maximal host cell adherence. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z.; Burucoa, C.; Grignon, B.; Baqar, S.; Huang, X.Z.; Kopecko, D.J.; Bourgeois, A.L.; Fauchere, J.L.; Blaser, M.J. Mutation in the peb1A locus of Campylobacter jejuni reduces interactions with epithelial cells and intestinal colonization of mice. Infect. Immun. 1998, 66, 938–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitag, C.M.; Strijbis, K.; van Putten, J.P.M. Host cell binding of the flagellar tip protein of Campylobacter jejuni. Cell. Microbiol. 2017, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddocks, O.D.; Short, A.J.; Donnenberg, M.S.; Bader, S.; Harrison, D.J. Attaching and effacing Escherichia coli downregulate DNA mismatch repair protein in vitro and are associated with colorectal adenocarcinomas in humans. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prorok-Hamon, M.; Friswell, M.K.; Alswied, A.; Roberts, C.L.; Song, F.; Flanagan, P.K.; Knight, P.; Codling, C.; Marchesi, J.R.; Winstanley, C.; et al. Colonic mucosa-associated diffusely adherent afaC+ Escherichia coli expressing lpfA and pks are increased in inflammatory bowel disease and colon cancer. Gut 2014, 63, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillanpaa, J.; Nallapareddy, S.R.; Singh, K.V.; Ferraro, M.J.; Murray, B.E. Adherence characteristics of endocarditis-derived Streptococcus gallolyticus ssp. gallolyticus (Streptococcus bovis biotype I) isolates to host extracellular matrix proteins. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2008, 289, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nystrom, H.; Naredi, P.; Hafstrom, L.; Sund, M. Type IV collagen as a tumour marker for colorectal liver metastases. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2011, 37, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Feng, B.; Dong, T.; Yan, G.; Tan, B.; Shen, H.; Huang, A.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, M.; Yang, P.; et al. Up-regulation of type I collagen during tumorigenesis of colorectal cancer revealed by quantitative proteomic analysis. J. Proteomics 2013, 94, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrigan, M.M.; Venugopal, A.; Roxas, J.L.; Anwar, F.; Mallozzi, M.J.; Roxas, B.A.; Gerding, D.N.; Viswanathan, V.K.; Vedantam, G. Surface-layer protein A (SlpA) is a major contributor to host-cell adherence of Clostridium difficile. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waligora, A.J.; Hennequin, C.; Mullany, P.; Bourlioux, P.; Collignon, A.; Karjalainen, T. Characterization of a cell surface protein of Clostridium difficile with adhesive properties. Infect. Immun. 2001, 69, 2144–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.P.; Kuo, C.J.; Koleci, X.; McDonough, S.P.; Chang, Y.F. Manganese binds to Clostridium difficile Fbp68 and is essential for fibronectin binding. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 3957–3969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; Wong, C.C.; Tong, L.; Chu, E.S.H.; Ho Szeto, C.; Go, M.Y.Y.; Coker, O.O.; Chan, A.W.H.; Chan, F.K.L.; Sung, J.J.Y.; et al. Peptostreptococcus anaerobius promotes colorectal carcinogenesis and modulates tumour immunity. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 2319–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sears, C.L. Enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis: A rogue among symbiotes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 22, 349–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boleij, A.; Hechenbleikner, E.M.; Goodwin, A.C.; Badani, R.; Stein, E.M.; Lazarev, M.G.; Ellis, B.; Carroll, K.C.; Albesiano, E.; Wick, E.C.; et al. The Bacteroides fragilis toxin gene is prevalent in the colon mucosa of colorectal cancer patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 60, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, L.; Thiele Orberg, E.; Geis, A.L.; Chan, J.L.; Fu, K.; DeStefano Shields, C.E.; Dejea, C.M.; Fathi, P.; Chen, J.; Finard, B.B.; et al. Bacteroides fragilis toxin coordinates a pro-carcinogenic inflammatory cascade via targeting of colonic epithelial cells. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 23, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.M.; Jung, H.Y.; Lee, J.Y.; Youn, J.; Lee, C.H.; Kim, K.H. Mitogen-activated protein kinase and activator protein-1 dependent signals are essential for Bacteroides fragilis enterotoxin-induced enteritis. Eur. J. Immunol. 2005, 35, 2648–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, A.C.; Destefano Shields, C.E.; Wu, S.; Huso, D.L.; Wu, X.; Murray-Stewart, T.R.; Hacker-Prietz, A.; Rabizadeh, S.; Woster, P.M.; Sears, C.L.; et al. Polyamine catabolism contributes to enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis-induced colon tumorigenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 15354–15359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, J.A.; O’Brien-Simpson, N.M.; Lenzo, J.C.; Orth, R.K.H.; Mansell, A.; Reynolds, E.C. Porphyromonas gulae activates unprimed and gamma interferon-primed macrophages via the pattern recognition receptors Toll-Like Receptor 2 (TLR2), TLR4, and NOD2. Infect. Immun. 2017, 85, e00282-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, J.A.; Attard, T.J.; Laughton, K.M.; Mansell, A.; O’Brien-Simpson, N.M.; Reynolds, E.C. Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide weakly activates M1 and M2 polarized mouse macrophages but induces inflammatory cytokines. Infect. Immun. 2014, 82, 4190–4203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosho, K.; Sukawa, Y.; Adachi, Y.; Ito, M.; Mitsuhashi, K.; Kurihara, H.; Kanno, S.; Yamamoto, I.; Ishigami, K.; Igarashi, H.; et al. Association of Fusobacterium nucleatum with immunity and molecular alterations in colorectal cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsuhashi, K.; Nosho, K.; Sukawa, Y.; Matsunaga, Y.; Ito, M.; Kurihara, H.; Kanno, S.; Igarashi, H.; Naito, T.; Adachi, Y.; et al. Association of Fusobacterium species in pancreatic cancer tissues with molecular features and prognosis. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 7209–7220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.W.; Redline, R.W.; Li, M.; Yin, L.; Hill, G.B.; McCormick, T.S. Fusobacterium nucleatum induces premature and term stillbirths in pregnant mice: Implication of oral bacteria in preterm birth. Infect. Immun. 2004, 72, 2272–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Guo, F.; Yu, Y.; Sun, T.; Ma, D.; Han, J.; Qian, Y.; Kryczek, I.; Sun, D.; Nagarsheth, N.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes chemoresistance to colorectal cancer by modulating autophagy. Cell 2017, 170, 548–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gur, C.; Ibrahim, Y.; Isaacson, B.; Yamin, R.; Abed, J.; Gamliel, M.; Enk, J.; Bar-On, Y.; Stanietsky-Kaynan, N.; Coppenhagen-Glazer, S.; et al. Binding of the Fap2 protein of Fusobacterium nucleatum to human inhibitory receptor TIGIT protects tumors from immune cell attack. Immunity 2015, 42, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eribe, E.R.K.; Olsen, I. Leptotrichia species in human infections II. J. Oral Microbiol. 2017, 9, 1368848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Castro, E.J.T.; Shim, H.; Advincula, J.V.G.; Kim, Y.W. Differences regarding the molecular features and gut microbiota between right and left colon cancer. Ann. Coloproctol. 2018, 34, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrien, M.; Collado, M.C.; Ben-Amor, K.; Salminen, S.; de Vos, W.M. The Mucin degrader Akkermansia muciniphila is an abundant resident of the human intestinal tract. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 1646–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrien, M.; Belzer, C.; de Vos, W.M. Akkermansia muciniphila and its role in regulating host functions. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 106, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanninen, A.; Toivonen, R.; Poysti, S.; Belzer, C.; Plovier, H.; Ouwerkerk, J.P.; Emani, R.; Cani, P.D.; De Vos, W.M. Akkermansia muciniphila induces gut microbiota remodelling and controls islet autoimmunity in NOD mice. Gut 2018, 67, 1445–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grander, C.; Adolph, T.E.; Wieser, V.; Lowe, P.; Wrzosek, L.; Gyongyosi, B.; Ward, D.V.; Grabherr, F.; Gerner, R.R.; Pfister, A.; et al. Recovery of ethanol-induced Akkermansia muciniphila depletion ameliorates alcoholic liver disease. Gut 2018, 67, 891–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcena, C.; Valdes-Mas, R.; Mayoral, P.; Garabaya, C.; Durand, S.; Rodriguez, F.; Fernandez-Garcia, M.T.; Salazar, N.; Nogacka, A.M.; Garatachea, N.; et al. Healthspan and lifespan extension by fecal microbiota transplantation into progeroid mice. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1234–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depommier, C.; Everard, A.; Druart, C.; Plovier, H.; Van Hul, M.; Vieira-Silva, S.; Falony, G.; Raes, J.; Maiter, D.; Delzenne, N.M.; et al. Supplementation with Akkermansia muciniphila in overweight and obese human volunteers: A proof-of-concept exploratory study. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1096–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradel, K.O.; Nielsen, H.L.; Schonheyder, H.C.; Ejlertsen, T.; Kristensen, B.; Nielsen, H. Increased short- and long-term risk of inflammatory bowel disease after Salmonella or Campylobacter gastroenteritis. Gastroenterology 2009, 137, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Gharaibeh, R.Z.; Newsome, R.C.; Pope, J.L.; Dougherty, M.W.; Tomkovich, S.; Pons, B.; Mirey, G.; Vignard, J.; Hendrixson, D.R.; et al. Campylobacter jejuni promotes colorectal tumorigenesis through the action of cytolethal distending toxin. Gut 2019, 68, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlan, P.D.; Shanahan, F.; Marchesi, J.R. Culture-independent analysis of Desulfovibrios in the human distal colon of healthy, colorectal cancer and polypectomized individuals. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2009, 69, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, C. Gasotransmitters in cancer: From pathophysiology to experimental therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016, 15, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapral, M.; Weglarz, L.; Parfiniewicz, B.; Lodowska, J.; Jaworska-Kik, M. Quantitative evaluation of transcriptional activation of NF-κB p65 and p50 subunits and IκBα encoding genes in colon cancer cells by Desulfovibrio desulfuricans endotoxin. Folia Microbiol. (Praha) 2010, 55, 657–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buc, E.; Dubois, D.; Sauvanet, P.; Raisch, J.; Delmas, J.; Darfeuille-Michaud, A.; Pezet, D.; Bonnet, R. High prevalence of mucosa-associated E. coli producing cyclomodulin and genotoxin in colon cancer. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, J.C.; Perez-Chanona, E.; Muhlbauer, M.; Tomkovich, S.; Uronis, J.M.; Fan, T.J.; Campbell, B.J.; Abujamel, T.; Dogan, B.; Rogers, A.B.; et al. Intestinal inflammation targets cancer-inducing activity of the microbiota. Science 2012, 338, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas-Ramos, G.; Petit, C.R.; Marcq, I.; Boury, M.; Oswald, E.; Nougayrede, J.P. Escherichia coli induces DNA damage in vivo and triggers genomic instability in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 11537–11542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassenaar, T.M. E. coli and colorectal cancer: A complex relationship that deserves a critical mindset. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 44, 619–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, F.; Frisan, T. Bacterial genotoxins: Merging the DNA damage response into infection biology. Biomolecules 2015, 5, 1762–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, A.; Travaglione, S.; Ballan, G.; Loizzo, S.; Fiorentini, C. The cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 from E. coli: A janus toxin playing with cancer regulators. Toxins (Basel) 2013, 5, 1462–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marches, O.; Ledger, T.N.; Boury, M.; Ohara, M.; Tu, X.; Goffaux, F.; Mainil, J.; Rosenshine, I.; Sugai, M.; De Rycke, J.; et al. Enteropathogenic and enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli deliver a novel effector called Cif, which blocks cell cycle G2/M transition. Mol. Microbiol. 2003, 50, 1553–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boleij, A.; van Gelder, M.M.; Swinkels, D.W.; Tjalsma, H. Clinical importance of Streptococcus gallolyticus infection among colorectal cancer patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 53, 870–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulamir, A.S.; Hafidh, R.R.; Abu Bakar, F. The association of Streptococcus bovis/gallolyticus with colorectal tumors: The nature and the underlying mechanisms of its etiological role. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 30, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbavy, S.; Lukac, L.; Porubsky, J.; Cerna, M.; Labuda, M.; Kmet’ova, J.; Papincak, J.; Durdik, S.; Jakubovsky, J. Collagen type IV in epithelial tumours of colon. Acta Histochem. 2002, 104, 331–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.S.; Cohen, A.M.; Guillem, J.G. Loss of basement membrane type IV collagen is associated with increased expression of metalloproteinases 2 and 9 (MMP-2 and MMP-9) during human colorectal tumorigenesis. Carcinogenesis 1999, 20, 749–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aymeric, L.; Donnadieu, F.; Mulet, C.; du Merle, L.; Nigro, G.; Saffarian, A.; Berard, M.; Poyart, C.; Robine, S.; Regnault, B.; et al. Colorectal cancer specific conditions promote Streptococcus gallolyticus gut colonization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E283–E291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulamir, A.S.; Hafidh, R.R.; Bakar, F.A. Molecular detection, quantification, and isolation of Streptococcus gallolyticus bacteria colonizing colorectal tumors: Inflammation-driven potential of carcinogenesis via IL-1, COX-2, and IL-8. Mol. Cancer 2010, 9, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Herold, J.L.; Schady, D.; Davis, J.; Kopetz, S.; Martinez-Moczygemba, M.; Murray, B.E.; Han, F.; Li, Y.; Callaway, E.; et al. Streptococcus gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus promotes colorectal tumor development. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.H.; Gao, Q.Y.; Cai, G.X.; Sun, X.M.; Sun, X.M.; Zou, T.H.; Chen, H.M.; Yu, S.Y.; Qiu, Y.W.; Gu, W.Q.; et al. Fecal Clostridium symbiosum for noninvasive detection of early and advanced colorectal cancer: Test and validation studies. EBioMedicine 2017, 25, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulli, L.; Marchi, S.; Petracca, R.; Shaw, H.A.; Fairweather, N.F.; Scarselli, M.; Soriani, M.; Leuzzi, R. CbpA: A novel surface exposed adhesin of Clostridium difficile targeting human collagen. Cell. Microbiol. 2013, 15, 1674–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, C.L.; Krejany, E.O.; Young, L.F.; O’Connor, J.R.; Awad, M.M.; Boyd, R.L.; Emmins, J.J.; Lyras, D.; Rood, J.I. The α-toxin of Clostridium septicum is essential for virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 2005, 57, 1357–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruitt, R.N.; Lacy, D.B. Toward a structural understanding of Clostridium difficile toxins A and B. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2012, 2, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.F.; Ai, L.Y.; Wang, J.L.; Ren, L.L.; Yu, Y.N.; Xu, J.; Chen, H.Y.; Yu, J.; Li, M.; Qin, W.X.; et al. Probiotics Clostridium butyricum and Bacillus subtilis ameliorate intestinal tumorigenesis. Future Microbiol. 2015, 10, 1433–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Jin, D.; Huang, S.; Wu, J.; Xu, M.; Liu, T.; Dong, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, S.; Zhong, W.; et al. Clostridium butyricum, a butyrate-producing probiotic, inhibits intestinal tumor development through modulating Wnt signaling and gut microbiota. Cancer Lett. 2020, 469, 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoi, H.; Chu, E.S.H.; Zhang, X.; Sheng, J.; Nakatsu, G.; Ng, S.C.; Chan, A.W.H.; Chan, F.K.L.; Sung, J.J.Y.; Yu, J. Peptostreptococcus anaerobius induces intracellular cholesterol biosynthesis in colon cells to induce proliferation and causes dysplasia in mice. Gastroenterology 2017, 152, 1419–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).