Abstract

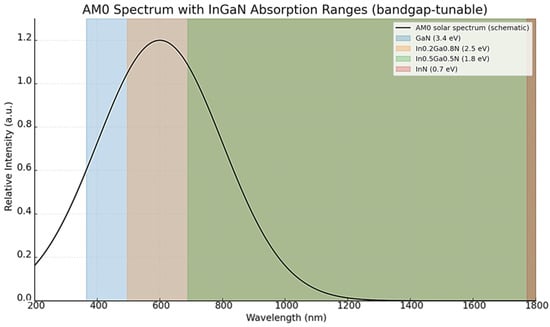

Gallium nitride (GaN) has emerged as one of the most promising wide-bandgap semiconductors for next-generation space photovoltaics. In contrast to conventional III–V compounds such as GaAs and InP, which are highly efficient under terrestrial conditions but suffer from radiation-induced degradation and thermal instability, GaN offers an exceptional combination of intrinsic material properties ideally suited for harsh orbital environments. Its wide bandgap, high thermal conductivity, and strong chemical stability contribute to superior resistance against high-energy protons, electrons, and atomic oxygen, while minimizing thermal fatigue under repeated cycling between extreme temperatures. Recent progress in epitaxial growth—spanning metal–organic chemical vapor deposition, molecular beam epitaxy, hydride vapor phase epitaxy, and atomic layer deposition—has enabled unprecedented control over film quality, defect densities, and heterointerface sharpness. At the device level, InGaN/GaN heterostructures, multiple quantum wells, and tandem architectures demonstrate outstanding potential for spectrum-tailored solar energy conversion, with modeling studies predicting efficiencies exceeding 40% under AM0 illumination. In this review article, the current state of knowledge on GaN materials and device architectures for space photovoltaics has been summarized, with emphasis placed on recent progress and persisting challenges. Particular focus has been given to defect management, doping strategies, and bandgap engineering approaches, which define the roadmap toward scalable and radiation-hardened GaN-based solar cells. With sustained interdisciplinary advances, GaN is anticipated to complement or even supersede traditional III–V photovoltaics in space, enabling lighter, more durable, and radiation-hard power systems for long-duration missions beyond Earth’s magnetosphere.

1. Introduction

With the rapid expansion of satellite constellations, lunar missions, Mars exploration and development of orbital infrastructure, the demand for lightweight, efficient, and durable power generation systems has become increasingly critical. Among the available technologies, photovoltaic (PV) devices converting solar radiation into electricity remain the primary solution for space-based power supply, owing to their modularity, long operational lifetimes, and continuous availability of solar irradiance in orbit [1,2].

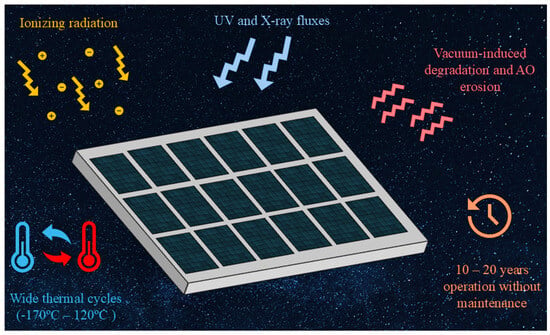

However, unlike terrestrial environments, space imposes extreme and multifactorial challenges on photovoltaic materials. These include:

- Intense ionizing radiation from high-energy protons, electrons, and heavy ions, particularly in low Earth orbit (LEO), medium Earth orbit (MEO), and geostationary Earth orbit (GEO);

- Elevated ultraviolet (UV) and X-ray fluxes;

- Wide thermal cycles, with temperature variations ranging from approximately −170 °C to +120 °C within a single orbit;

- Vacuum-induced degradation and outgassing, especially under the influence of atomic oxygen (AO);

- Mechanical stress arising from launch vibrations and orbital thermal fatigue;

- Long mission durations requiring PV systems to operate reliably for 10–20 years without maintenance.

In addition to environmental robustness, next-generation PV materials must satisfy strict mass, volume, and efficiency constraints, particularly for interplanetary probes, small satellites, and large-scale satellite constellations. Achieving high power-to-weight ratios and compact architectures is essential for reducing launch costs and increasing mission flexibility [3,4,5]. Furthermore, with rising interest in megaconstellations and space-based solar power, scalability and cost-effective manufacturability of PV materials have become central concerns, as thousands of deployable solar units will be required to meet future energy and communication demands [6].

Over the past decades, III–V compound semiconductors including gallium arsenide (GaAs) and indium phosphide (InP) have dominated the landscape of space photovoltaics. Their high energy conversion efficiencies as well as compatibility with multi-junction devices make them appropriate for space missions, especially when combined with lattice-matched layers and spectrum-optimized designs [7,8,9].

Although more radiation-tolerant than silicon, GaAs and InP still undergo significant performance degradation when exposed to prolonged bombardment by protons and electrons, which constitutes a critical challenge for long-duration missions beyond Earth’s protective magnetosphere. Moreover, their performance declines at elevated operating temperatures while their structural stability under repeated thermal cycling remains limited. The main environmental stress factors leading to the degradation of III–V photovoltaic devices in space environments are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of critical stressors affecting III–V photovoltaic devices in space applications.

These factors collectively contribute to performance degradation and reduced structural stability of III–V semiconductors under extreme space conditions. Another serious concern is the toxicity and limited availability of key elements such as arsenic, cadmium and indium, which not only introduce environmental and safety risks but also complicate large-scale supply chains due to geopolitical and resource limitations [10,11,12]. Furthermore, the fabrication of high-quality III–V structures typically relies on epitaxial growth methods. They, in turn, require expensive vacuum equipment, rigorous process control and are often restricted to small-scale batch production. These factors collectively hinder the scalability and cost-effectiveness of these technologies, particularly in the context of mass deployment for satellite constellations and long-range space missions. These obstacles have catalyzed a growing interest in alternative PV materials capable of maintaining the performance advantages of III–V semiconductors while overcoming their inherent limitations—especially under the extreme conditions characteristic for space environments [13,14,15,16].

GaN, a wide-bandgap III-nitride semiconductor, has emerged as a highly promising material for space photovoltaics. Originally developed for light-emitting diodes (LEDs) and high-frequency electronics, GaN is now gaining attention for its exceptional combination of radiation resistance, thermal and chemical stability and interesting electronic properties. Its wide bandgap (~3.4 eV) allows for efficient operation under intense solar radiation, while its robustness against proton and electron irradiation makes it appropriate for long-duration missions in difficult and demanding orbital environments [17,18,19]. In addition to its inherent material advantages, GaN supports a range of advanced photovoltaic devices including such architectures as InGaN/GaN heterojunctions, compositionally graded structures and quantum wells [20,21].

From a technological viewpoint, recent progress in metal–organic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD), molecular beam epitaxy (MBE), ALD, and hydride vapor phase epitaxy (HVPE) allows precise GaN film deposition on various substrates, including silicon, sapphire and native GaN—expanding the design space for integration and deployment [22].

Taken together, these features make GaN not merely a substitute for existing photovoltaic materials but a transformative and scalable platform for the next generation of solar energy harvesting systems designed specifically for the demands of space. The following sections of this review explore in detail the material properties, synthesis strategies and cell architecture that form the basis for the development of GaN-based space photovoltaics.

2. Key Properties of GaN Relevant to Space Applications

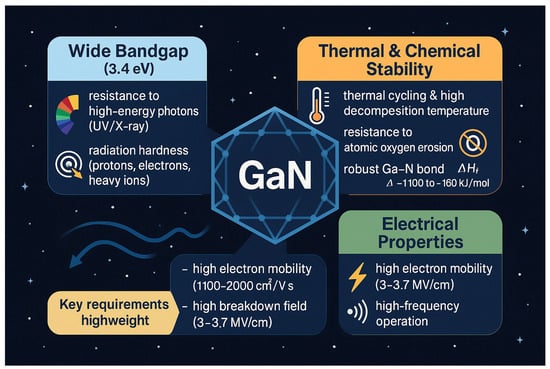

GaN has emerged as one of the most promising semiconductor materials for next-generation space technologies. Its intrinsic properties combine a wide bandgap with remarkable thermal, chemical, and electrical stability, enabling reliable operation under extreme conditions such as intense radiation, high vacuum, and severe thermal cycling. Unlike conventional III–V semiconductors, GaN provides a unique balance of robustness and efficiency, which makes it highly relevant for both photovoltaic and electronic applications in space. The key properties of GaN relevant to space applications are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Overview of the fundamental material properties of GaN relevant to space environments.

These attributes collectively explain the growing interest in GaN as an enabling material for space systems. They not only address the inherent limitations of traditional III–V semiconductors but also open new opportunities for designing devices with enhanced durability and performance. In the following subsections, each of these key properties is discussed in detail, with a focus on their implications for space photovoltaics and electronics.

2.1. Wide Bandgap and Resistance to Radiation-Induced Damage

A significant characteristic making GaN exceptionally promising for space photovoltaics is its wide direct bandgap of approximately 3.4 eV. This property plays an important role in determining thermal, electronic and optical stability of the material under harsh orbital conditions. In contrast to narrow-bandgap semiconductors such as Si (1.1 eV) or GaAs (1.4 eV), GaN maintains low intrinsic carrier concentrations and is significantly less susceptible to thermally induced carrier excitation [23,24]. As a result, GaN-based devices show reduced leakage currents and superior operation in high-temperature and high-irradiance environments such as low Earth orbit (LEO), geostationary orbit (GEO) and interplanetary space [25]. The wide bandgap also enables an exceptional resistance of GaN to radiation-induced damage. In space, semiconductors are permanently exposed to high-energy particles which can displace atoms in the crystal lattice and generate defects acting as recombination centers. GaN, however, benefits from strong covalent bonding, low atomic number and high cohesive energy, which contribute to its resistance to displacement damage. Reported displacement threshold energies typically exceed 10 eV (around 12 eV for N and over 20 eV for Ga), significantly higher than in many III–V semiconductors such as GaAs or InP [26,27].

Numerous irradiation studies have demonstrated that GaN retains its optoelectronic properties under extreme conditions. GaN-based heterostructures and quantum wells show minimal degradation in carrier mobility, photoluminescence intensity and junction integrity even after proton fluences exceeding 1014 cm−2—levels at which GaAs or InP devices experience severe performance loss [28,29]. GaN also exhibits robustness against both ionizing and non-ionizing radiation effects, as confirmed by flight-demonstrated devices in geostationary orbit [30,31]. Power-electronics-grade GaN shows high tolerance in harsh space radiation environments, outperforming Si-based MOSFETs and eliminating the need for extensive shielding [32,33]. This radiation hardness provides system-level advantages: GaN-based devices can maintain functionality with minimal shielding, reducing both mass and volume—two critical constraints in aerospace design. Enhanced durability also lowers the risk of system failure and enables more aggressive mission trajectories, including operation in radiation-intensive environments such as lunar or Martian orbits [34].

2.2. High Thermal and Chemical Stability

GaN demonstrates notable thermal and chemical stability, important for reliable operation in extreme space conditions. Because of its wide bandgap and strong bonding, GaN shows good tolerance to temperature fluctuations and limited chemical degradation under vacuum and elevated temperatures. In situ decomposition studies indicate that GaN begins to decompose in vacuum only at high temperatures, while nitrogen-rich environments significantly suppress this effect [35]. Surface studies of GaN(0001) reveal that Ga-terminated surfaces resist many chemical reactions, supporting overall environmental robustness [36]. Device-level tests also confirm high thermal durability: GaN HEMTs with improved heat-dissipation structures show reduced performance degradation at elevated junction temperatures [37], and studies of deep-level traps in MOCVD-grown GaN suggest that many defect states remain stable under moderate annealing [38]. GaN exhibits high thermal stability due to its wide bandgap and strong covalent bonding in the wurtzite structure. The material maintains structural integrity at temperatures far exceeding those tolerated by GaAs or InP, which often experience lattice degradation or defect activation at much lower temperatures. The high thermal conductivity of GaN, typically 130–230 W·m−1·K−1 (with record values near 300 W·m−1·K−1), further improves heat dissipation and reduces thermally induced degradation in spaceborne devices [39,40,41].

Recent studies provide quantitative insight into the relationship between temperature cycling behavior and device performance in GaN-based electronics. In particular, experimental investigations reported in [42] directly analyze the impact of repeated thermal cycling on the electrical stability of GaN devices, showing that cyclic heating and cooling can induce gradual changes in series resistance and leakage current due to thermally induced stress at heterointerfaces. These effects are closely related to thermal-expansion mismatch and stress accumulation during repeated temperature excursions, which are especially relevant for space environments characterized by frequent day–night transitions. Complementary evidence is provided by high-temperature power-cycling studies of p-GaN HEMTs reported by Hein et al. [43]. Devices were subjected to repetitive power and temperature cycling with virtual junction temperatures reaching 175 °C and endured more than 40 million cycles without irreversible degradation of key electrical parameters. Although the on-state resistance increased with temperature—reaching approximately 2.5× its room-temperature value at 200 °C—this behavior was reversible and attributed to phonon-limited transport rather than permanent structural damage. Importantly, leakage currents at 600 V remained below 100 µA at elevated temperature, and no significant drift in threshold voltage or gate characteristics was observed. Thermal runaway occurred only under current-saturation conditions, linking performance degradation to electrothermal operating regimes rather than intrinsic material failure. These results demonstrate the inherent thermal robustness of GaN-based devices and their strong tolerance to repeated temperature cycling, which is a key advantage for space applications.

GaN’s hybrid ionic–covalent bonding contributes to its strong Ga–N bonds (bond length ~1.95 Å) and relatively high formation enthalpy (−110 to −160 kJ/mol), both indicators of thermodynamic stability [44,45,46]. Its low thermal expansion coefficients—~5.6 × 10−6 K−1 along the a-axis and ~3.2 × 10−6 K−1 along the c-axis—help minimize thermal-mismatch stress during heating–cooling cycles, reducing risks of delamination or cracking in GaN-based devices [47]. Thermodynamic studies also show that GaN resists oxidation under low oxygen chemical potential, and full oxidation becomes favorable only under harsher conditions [48]. Experimental and modeling studies further indicate that GaN layers maintain structural coherence under repeated thermal cycles up to several hundred degrees Celsius, with manageable strain relative to substrates such as sapphire or SiC [49,50,51,52].

2.3. Electrical Transport Properties and Breakdown Field Strength

GaN is widely recognized for its excellent electrical transport properties, which make it a leading material for high-power and high-frequency applications. Its wide bandgap and strong polar bonding give rise to high electron mobility, high saturation velocity, and an exceptionally high breakdown field. Electron mobility in GaN is governed by several scattering mechanisms, including ionized impurities, polar optical phonons, piezoelectric scattering, and acoustic phonons. At low temperatures (<100 K), acoustic phonons dominate, while at higher temperatures, polar optical phonon scattering becomes the primary limitation [53,54]. Typical room-temperature mobility values for bulk GaN lie between 1100 and 2000 cm2/V·s [55]. Mobility decreases with temperature due to enhanced phonon scattering, consistent with Monte Carlo and Hall measurements. GaN also exhibits a high saturation electron velocity of about 2–3 × 107 cm/s at room temperature, enabling fast switching performance in electronic devices [56]. A defining property of GaN is its very high breakdown electric field, substantially exceeding that of Si or GaAs. Critical field strengths for wurtzite GaN are typically 3.0–3.75 MV/cm [55], allowing GaN devices to sustain large voltage biases. Simulations show that the fields required for drift-velocity saturation or significant electron heating increase with temperature, reaching >100 kV/cm at elevated conditions. Experimental studies confirm that GaN tolerates extreme electric fields because of its wide bandgap and low intrinsic carrier concentration. Temperature strongly affects electron transport: as the lattice heats, phonon populations rise, reducing mobility and saturation velocity. This is particularly relevant for power electronics, where self-heating is significant. Simulations show stable mobility in the low-field region, saturation at moderate fields due to polar optical phonons, and intervalley scattering at very high fields (>200 kV/cm), which alters drift velocity and energy relaxation [53,56,57].

The combination of high breakdown field, high mobility, and high saturation velocity makes GaN highly suitable for power electronics, RF amplifiers, and high-frequency systems. Its ability to function under high electric fields and elevated temperatures, together with low intrinsic carrier concentration and good thermal conductivity (~1.6 W/cm·K), enhances device reliability in demanding environments [58,59]. Table 1 summarizes key properties of GaN relative to other III–V materials, highlighting its superior bandgap, thermal conductivity, radiation tolerance, and reduced toxicity—factors contributing to its growing relevance for next-generation space photovoltaics.

Table 1.

Comparison of selected material properties of GaN, GaAs, and InP relevant to space photovoltaic applications. Values are given for room temperature (300 K) unless otherwise noted. Radiation tolerance values are indicative and depend on particle energy, device architecture, and test conditions.

The data clearly underline that GaN offers a unique balance of wide bandgap, high thermal conductivity, and superior resistance to radiation damage compared to GaAs and InP. At the same time, challenges related to substrate cost and defect management remain critical barriers for its broader deployment. These considerations set the stage for the following section, which focuses on epitaxial growth techniques and defect-reduction strategies essential for advancing GaN-based space photovoltaics.

GaN is not only relevant as a photovoltaic absorber but also as a key material for high-efficiency power-conversion circuits in space systems. Its wide bandgap, high breakdown field, and high electron mobility enable the fabrication of GaN HEMTs and Schottky diodes that operate at high frequencies with low switching and conduction losses. Such devices are central to power-management units, DC–DC converters, and MPPT circuits in satellites, where thermal constraints and radiation exposure are critical challenges. Owing to its strong resistance to displacement damage and ionizing radiation, GaN allows compact, efficient, and robust power-conditioning electronics that complement GaN-based photovoltaic absorbers.

Beyond these transport parameters, the above-described material characteristics—wide bandgap, strong bonding, high thermal stability, and excellent radiation resistance—directly reinforce GaN’s electrical performance in space environments. They allow GaN devices to maintain stable mobility, low leakage, and predictable switching behavior even under high fields, strong irradiation, and large temperature swings characteristic of orbital operation. As a result, GaN circuits used in power management, signal conditioning, and high-frequency communication systems benefit from reduced degradation and increased operational lifetime compared to conventional III–V technologies. This link between intrinsic material robustness and reliable charge transport is one of the main reasons why GaN is considered a key platform not only for photovoltaic absorbers but also for the accompanying high-efficiency electronics required in modern space missions [63,64,65].

3. Synthesis Techniques for GaN-Based Photovoltaic Structures

For space photovoltaics, GaN growth methods should be discussed beyond basic deposition aspects. Key factors include crystalline quality, defect density, scalability, and stability under radiation and temperature cycling. Space applications require low dislocation densities, good structural uniformity, and mechanical stability during repeated thermal changes. These requirements strongly influence which growth techniques are practically suitable. Therefore, ALD, MOCVD, MBE, and HVPE are discussed below with a focus on their relevance and limitations for GaN-based space photovoltaic devices.

3.1. Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD)

Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD), including plasma-enhanced variants, is characterized by excellent conformality and precise thickness control at the atomic scale. However, its inherently low deposition rates make ALD unsuitable for the growth of micron-thick photovoltaic layers. In the context of space photovoltaics, ALD is therefore best positioned as a complementary technique for ultrathin passivation layers, tunneling junctions, or interface engineering, rather than as a primary method for layer growth [66].

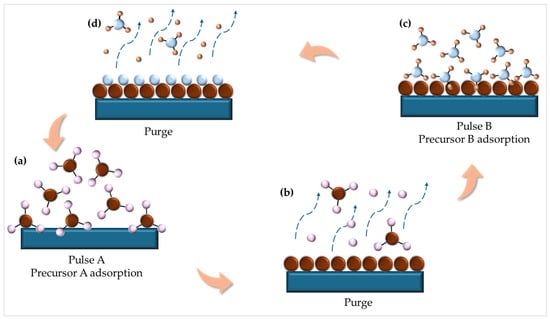

ALD is a vapor-phase technique based on self-limiting surface reactions, offering atomic-scale thickness control, excellent conformality, and uniform coverage over complex three-dimensional topographies [67,68,69]. These advantages make ALD particularly attractive for the deposition of GaN thin films, especially in applications requiring ultrathin, uniform layers—such as nanoscale electronics, optoelectronics, and photovoltaics for space technologies [70,71]. In Figure 3, the ALD process is schematically presented, illustrating the sequential, self-limiting surface reactions that enable layer-by-layer growth with sub-nanometer precision.

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of the ALD cycle. The process consists of alternating precursor pulses separated by purge steps: (a) precursor A adsorption on the activated substrate surface, (b) purge to remove unreacted molecules and by-products, (c) precursor B adsorption and surface reaction, followed by (d) a second purge. Each cycle deposits a controlled sub-monolayer, enabling atomic-scale thickness control and conformal film growth.

In ALD of GaN, a typical cycle consists of alternate exposure to a gallium precursor and a nitrogen source, separated by inert gas purges to prevent gas-phase reactions. This cyclic approach allows for layer-by-layer growth, yielding stoichiometric GaN films with precise thickness control. One of the challenges in ALD of GaN is the relatively low reactivity of common nitrogen precursors (e.g., NH3) at low temperatures. Therefore, plasma-enhanced ALD (PEALD) is often used, where nitrogen is activated via radio frequency (RF) or microwave plasma, significantly enhancing surface reactivity and film quality at temperatures as low as 200–300 °C [72].

Various gallium precursors have been investigated in the literature for GaN ALD, including:

- Trimethylgallium (TMGa): A widely used precursor; allows for good control over film composition but may result in carbon contamination due to methyl ligands [73];

- Tris(dimethylamido)gallium (III) (Ga2(NMe2)6: This non-halide precursor has demonstrated promise for low-temperature processes with reduced carbon incorporation [74];

- Gallium trichloride (GaCl3): Although corrosive and requiring higher temperatures, it offers better control over film purity in some configurations [75];

For nitrogen sources, NH3 plasma and N2/H2 plasma [76] are most commonly used, enabling efficient nitridation at reduced thermal budgets—critical for temperature-sensitive substrates or multilayer structures.

An illustrative example is provided by Rouf et al. [77], who demonstrated plasma-enhanced ALD of GaN using tris(dimethylamido)gallium(III) [Ga(NMe2)3] as the gallium precursor and NH3 plasma as the nitrogen source. Self-limiting growth was observed in the temperature range of 130–250 °C, with a growth per cycle of approximately 1.4 Å. The resulting films exhibited crystallinity on Si(100) substrates with nearly stoichiometric Ga/N ratios and very low carbon and oxygen contamination. Notably, epitaxial GaN was achieved on 4H-SiC without the need for an AlN buffer layer—a result not previously reported for ALD GaN. The films showed an optical bandgap of ~3.42 eV and unintentional n-type conductivity. Kim et al. [78] reported thermal ALD of GaN on Si(100) substrates using GaCl3 and NH3, achieving a growth per cycle of approximately 2.0 Å/cycle. However, the thermal approach required temperatures above 400 °C and presented risks of Cl incorporation. Austin et al. [71] demonstrated high-temperature ALD of GaN on silica nanosprings using TMGa and NH3 at 800 °C, obtaining conformal amorphous coatings that became nanocrystalline (with an average crystallite size of 11.5 ± 0.5 nm) upon introducing Al2O3 or AlN buffer layers. Hafdi et al. [79] examined the surface chemistry of GaN ALD using TEG and NH3, showing via in situ mass spectrometry that ethyl ligands are removed during the TEG pulse, followed by ligand-exchange reactions during NH3 exposure. Banerjee et al. [70] reported a purely thermal ALD route for polycrystalline GaN using TMGa and NH3 at 400 °C, achieving a growth per cycle of ~0.1 nm without plasma activation and maintaining excellent conformality in high-aspect-ratio structures. The ALD window was narrow (375–425 °C), with decomposition of TMGa above 425 °C leading to contamination. Growth behavior strongly depended on NH3 partial pressure and pulse duration. Recent studies have expanded ALD GaN methodology. Cong et al. [80] investigated PEALD with TMGa/NH3 plasma over 250–350 °C, observing a transition from amorphous to oriented films. Wang et al. [81] achieved low-resistance N-polar GaN at 300 °C.

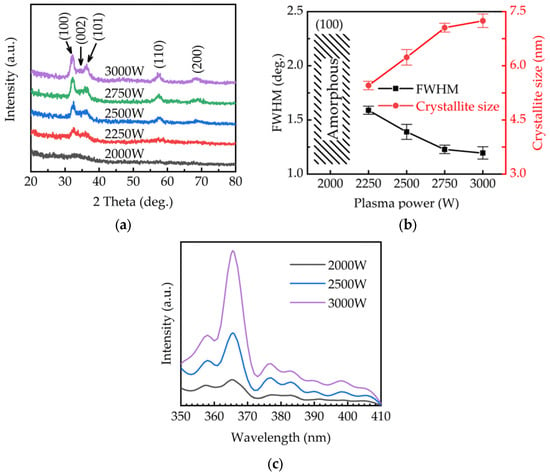

Jiang et al. [82] demonstrated effective oxygen reduction in PEALD-grown GaN using NH3-derived plasma radicals. In Figure 4, representative XRD and photoluminescence data illustrate the direct impact of plasma power on film quality.

Figure 4.

(a) XRD patterns of PEALD-GaN films deposited at different plasma powers, (b) corresponding FWHM values and crystallite sizes, and (c) room-temperature photoluminescence spectra showing enhanced near-band-edge emission at higher plasma power. Adapted from Ref. [82] under the CC BY 4.0 license.

At low plasma power, GaN films show weak and broadened XRD peaks, indicating poor crystallinity. Increasing the plasma power leads to well-defined GaN diffraction peaks, reduced FWHM values, and increased crystallite size. Correspondingly, PL spectra reveal a strong enhancement of near-band-edge emission at ~365 nm and a reduction in defect-related luminescence, confirming improved crystalline quality and lower oxygen-related defect density. Complementary process strategies were reported by Deminskyi et al. [76], who introduced an additional B-pulse to enhance ethyl-ligand removal and increase the growth-per-cycle, and by Yun et al. [83], who demonstrated polarity control through the incorporation of an Ar-plasma buffer layer.

The reviewed studies indicate that GaN ALD/PEALD commonly relies on metal–organic precursors such as TMG, TEG, Ga(NMe2)3, and GaCl3, with NH3 as the dominant nitrogen source. PEALD enhances nitridation efficiency, reduces contamination, and enables deposition at moderate temperatures (250–350 °C), while thermal ALD typically requires ≥400 °C and may suffer impurity incorporation. Substrates include Si(100), semi-insulating GaN, 4H-SiC, and 1D architectures. Process-dependent film characteristics range from amorphous to nanocrystalline to well-oriented. Modifications such as additional reactive pulses or Ar-plasma buffers enable improved growth rates and polarity control. Overall, PEALD is emerging as the preferred approach for crystalline GaN at moderate temperatures, while thermal ALD remains advantageous for extreme conformality. Ongoing research focuses on lowering deposition temperatures, improving crystallinity without post-annealing, and minimizing impurities. Plasma diagnostics, in situ ellipsometry, and advanced characterization (XPS, TEM, XRR) are being used to better understand growth mechanisms. Emerging directions include area-selective ALD [84,85,86], hybrid ALD–CVD/MBE processes [87,88], and low-temperature ALD on flexible substrates [89], supporting future lightweight and conformable photovoltaic architectures.

3.2. Metal–Organic Chemical Vapor Deposition (MOCVD)

Metal–Organic Chemical Vapor Deposition (MOCVD) is the dominant and industrially established technique for the growth of GaN layers used in photovoltaic devices, particularly for the relatively thick active layers required for efficient light harvesting. Its high deposition rates (typically several µm/h), excellent thickness and composition uniformity on large-diameter wafers, and compatibility with established III–V manufacturing processes make it well suited for practical device fabrication. From the perspective of space photovoltaics, these advantages are especially important. MOCVD enables reliable growth of GaN and InGaN layers with controlled composition, sharp interfaces, and relatively low defect densities, which are key requirements for multi-junction and tandem solar-cell concepts. In addition, the method supports scalable wafer-level processing and reproducibility, both critical for space-grade devices. In contrast, techniques such as ALD, while valuable for ultrathin passivation or tunneling layers, are inherently unsuitable for micron-scale layer growth due to their very low deposition rates [90,91].

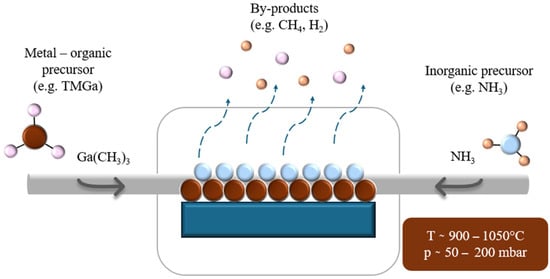

Unlike ALD, MOCVD operates under continuous gas flow rather than self-limiting surface reactions, enabling higher growth rates and the deposition of high-quality single-crystalline layers over large areas. In this process, volatile metal–organic precursors (such as TMGa and nitrogen sources (typically ammonia, NH3)) are introduced into a heated reactor, where they undergo thermal decomposition at the substrate surface to form the desired compound. Key process parameters—including growth temperature, V/III ratio, reactor pressure, and precursor flow rates—have a direct influence on film crystallinity, defect density, surface morphology, and polarity. In Figure 5, the principle of the MOCVD process is schematically presented, showing the continuous supply of metal–organic and nitrogen precursors and their thermal decomposition on the heated substrate surface.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of the metal–organic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD) process.

MOCVD is the dominant method for GaN growth in optoelectronic and high-power electronic devices due to its scalability, ability to achieve epitaxial growth on lattice-matched and lattice-mismatched substrates, and compatibility with in situ monitoring techniques (e.g., reflectometry, mass spectrometry). Advanced variations, such as low-pressure MOCVD (LP-MOCVD), pulsed MOCVD, and selective-area growth, further expand the flexibility of this technique for both planar and nanostructured architectures.

Research on MOCVD of GaN has increasingly focused on overcoming the limitations of precursor decomposition efficiency, impurity incorporation, and surface morphology control. Various approaches have been proposed to enhance growth rates and film quality while reducing process temperatures and contamination. One such approach was presented by Zhang et al. [92], who developed and applied a laser-assisted MOCVD (LA-MOCVD) method for GaN growth. In their work, a CO2 laser (λ ≈ 9.219 µm) was used to resonantly excite NH3 molecules, significantly improving their dissociation in the reaction zone. This strategy enabled GaN growth rates of up to 10 µm/h, with smooth, pit-free surfaces even at 8.5 µm/h. The films showed a markedly reduced carbon content (~5.5 × 1015 cm−3) and high crystalline quality, with electron mobilities exceeding 1000 cm2/V·s at room temperature. These results demonstrated that laser-assisted NH3 activation can substantially enhance growth efficiency, purity, and electrical performance compared to conventional MOCVD.

Another noteworthy example is provided by Hu et al. [93], who designed and demonstrated a novel Buffered Distributed Spray MOCVD reactor intended for high-quality GaN growth for LED structures. The reactor incorporates vertically distributed gas injection and horizontal gas inlets, enabling precise and uniform precursor delivery to the reaction zone. This configuration improves gas flow control, reduces parasitic reactions, and enhances the uniformity of epitaxial layers across large wafer batches. Experimental growths performed in a 36 × 2″ wafer configuration showed that the reactor architecture supports efficient GaN and InGaN/GaN multiple quantum well (MQW) deposition with excellent thickness uniformity. Structural and optical characterization, including TEM and photoluminescence, confirmed that the BDS design yields epitaxial films of high crystalline quality, making it particularly well-suited for large-scale LED manufacturing.

Swain et al. [94] addressed the sustainability aspect of MOCVD-based GaN production by investigating the recovery of gallium from waste dust generated during the epitaxial growth process. Detailed chemical analysis of the collected reactor dust revealed a high gallium content in forms suitable for extraction. The authors developed a chemical recovery protocol involving dissolution, selective precipitation, and separation steps, ultimately obtaining gallium compounds of high purity that could be reused as precursors in subsequent growth cycles. This approach not only reduces the consumption of raw gallium but also minimizes waste generation, thereby lowering both the economic and environmental footprint of GaN manufacturing.

Delgado Carrascon et al. [95] explored a hot-wall MOCVD configuration for the homoepitaxial growth of GaN. In this reactor design, the entire chamber wall is uniformly heated rather than relying solely on localized substrate heating. This approach minimizes thermal gradients, stabilizes the reaction environment, and enhances precursor utilization efficiency. The method enabled the deposition of high-purity, defect-reduced GaN layers directly on GaN substrates, yielding atomically smooth surfaces and narrow X-ray rocking curve widths indicative of excellent crystalline quality. Such improvements are particularly advantageous for advanced optoelectronic devices, where lattice perfection and surface uniformity critically affect performance.

Collectively, these studies highlight the remarkable versatility of MOCVD as a GaN growth technique, enabling not only the fabrication of high-quality epitaxial layers for a broad range of applications but also innovations that address efficiency, scalability, and environmental sustainability. Advances in reactor design, precursor activation methods, and resource recovery strategies demonstrate that both fundamental process optimization and system-level engineering can significantly improve film quality, reduce defect densities, and lower operational costs. As such, MOCVD remains a cornerstone technology for GaN production, with ongoing research continuing to expand its capabilities for next-generation optoelectronic and power electronic devices.

3.3. Molecular Beam Epitaxy (MBE)

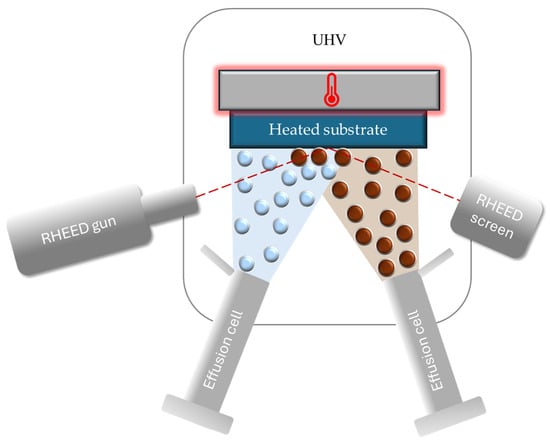

Molecular Beam Epitaxy (MBE) is a highly controlled epitaxial growth technique widely used for the fabrication of III–V compound semiconductors, including GaN. In MBE, ultra-pure elemental or compound sources are thermally evaporated or sublimated in ultra-high vacuum (UHV) conditions, producing molecular or atomic beams that impinge directly on a heated substrate. MBE offers unparalleled control over interfaces, doping profiles, and low-dimensional structures, making it highly valuable for fundamental studies and high-performance electronic devices. However, its intrinsically low growth rates and limited scalability restrict its applicability for thick photovoltaic layers required in space solar cells. As such, MBE is better suited for specialized device layers or model structures rather than large-scale photovoltaic absorbers [96].

In Figure 6, the molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) process is schematically illustrated, highlighting the use of ultra-high vacuum, effusion cells, and molecular or atomic beams for epitaxial film growth with atomic-layer precision.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of the molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) process.

Unlike chemical vapor deposition methods, MBE relies on physical evaporation rather than chemical precursor decomposition, which allows precise control of deposition rates at the monolayer scale. The extremely low background pressure (typically below 10−9 Torr) minimizes impurity incorporation, enabling the synthesis of high-purity, defect-controlled films [97,98,99].

Key growth parameters—such as substrate temperature, beam flux ratios (e.g., Ga/N), and growth rate—strongly influence crystal quality, surface morphology, and defect density. The inherently slow growth rates of MBE (commonly below 2 µm/h) are offset by the unparalleled precision in controlling composition, doping profiles, and interface sharpness, making the technique particularly valuable for advanced heterostructures, quantum wells, and low-dimensional architectures. Additionally, in situ diagnostics such as Reflection High-Energy Electron Diffraction (RHEED) provide real-time feedback on surface reconstruction and growth kinetics, enabling dynamic process optimization [100,101].

A distinctive advantage of MBE lies In Its flexibility: by modifying the growth environment, energy supply, or flux modulation, researchers can directly tailor film properties, morphology, and defect density. For instance, Aggarwal et al. [102] employed laser-assisted MBE (laser-MBE) to overcome the inherent low growth rate and to stimulate enhanced reactivity of nitrogen. By optimizing the buffer layer design and pre-nitridation conditions on nonpolar r-plane (11–20) sapphire substrates, they achieved a spectrum of GaN nanostructures ranging from granular thin films (~160 nm) to vertically aligned nanocolumns (~370 nm) and nanoporous GaN films (~560 nm, pore diameters 70–110 nm). Detailed structural characterization using RHEED, high-resolution X-ray diffraction, and Raman spectroscopy confirmed the epitaxial wurtzite phase with remarkably low residual strain (0.03–0.23 Gpa). Importantly, when integrated into metal–semiconductor–metal (MSM) ultraviolet photodetectors, nanoporous GaN exhibited outstanding responsivity up to 358 mA/W at 1 V, representing a breakthrough in device performance for this morphology. This study demonstrated that MBE, when combined with laser assistance, can broaden the accessible morphological space of GaN while simultaneously enhancing optoelectronic functionality.

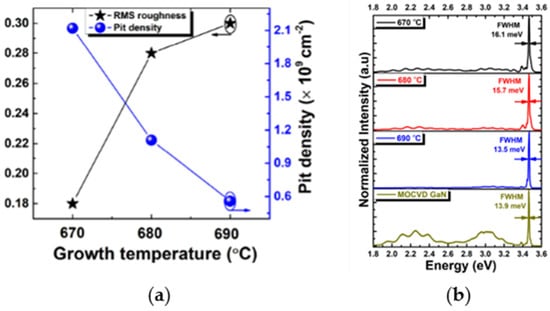

The ability of MBE to control morp”olog’cal transitions was further highlighted by Mai et al. [103], who systematically investigated the effect of substrate temperature on GaN films. Their work directly addressed the needs of HEMT structures, in which crystalline quality and defect suppression are paramount. By carefully increasing substrate temperature, they triggered a transition from three-dimensional island growth to a two-dimensional layer-by-layer growth regime. In Figure 7, the influence of growth temperature on surface morphology and defect-related optical properties is presented.

Figure 7.

(a) Surface roughness and pit density of MBE-grown GaN films as a function of growth temperature, and (b) normalized near-band-edge photoluminescence spectra showing FWHM narrowing with increasing temperature. Adapted from Ref. [103] under the CC BY 4.0 license.

Figure 7a shows that increasing the growth temperature from 670 to 690 °C leads to a clear reduction in pit density and the formation of atomically smooth surfaces, with RMS roughness decreasing to approximately 0.3 nm at 690 °C. At the same time, Figure 7b demonstrates a progressive narrowing of the near-band-edge photoluminescence peak, with the FWHM decreasing from 16.1 meV to 13.5 meV, indicating reduced defect density and improved crystalline quality. At the optimal temperature of 690 °C, GaN films exhibited atomically smooth surfaces (RMS roughness of 0.3 nm), significant relaxation of residual strain, and strong suppression of defect-related yellow luminescence, which is commonly associated with deep-level states. Electrical characterization revealed that these high-quality MBE-grown GaN channel layers achieved breakdown voltages of ~1450 V, markedly surpassing the ~1180 V typically reported for MOCVD-grown counterparts. This result underscores the potential of MBE to engineer ultra-low-defect GaN for next-generation power electronics, where breakdown strength and reliability are critical.

Beyond temperature and morphology, alternative growth strategies within the MBE framework have been developed to further suppress defects. Yang et al. [104] introduced metal-modulated epitaxy (MME), in which the gallium flux is periodically modulated to deliberately alter surface stoichiometry and adatom kinetics. This modulation effectively regulates the competition between gallium-rich and nitrogen-rich conditions, leading to reduced incorporation of extended defects and improved uniformity across the film. By fine-tuning the modulation parameters, the authors achieved GaN layers with excellent crystalline order and reduced impurity levels. Their work demonstrated that MME can be seen as a powerful refinement of conventional MBE, capable of producing high-performance GaN films that meet the stringent requirements of optoelectronic and high-frequency devices. In turn, Suzuki et al. [105] investigated the deposition of GaN films on unconventional MgO substrates in (111) and (001) orientations using radio-frequency plasma-assisted MBE (RF-MBE). Despite the considerable lattice mismatch between GaN and MgO, the authors showed that epitaxial GaN layers with acceptable structural quality could be grown. This work highlighted the adaptability of MBE to diverse substrate platforms, expanding its potential for integration into non-standard device architectures.

In addition to morphological and structural optimization, MBE has proven highly effective for controlled doping of GaN [106]. A notable example is the introduction of magnesium acceptors during plasma-assisted MBE under shutter-controlled growth conditions, which enabled the achievement of p-type carrier concentrations as high as 3.12 × 1018 cm−3. The presence of Mg not only promoted conformal layer growth but also improved carrier mobility and overall structural quality, particularly under nitrogen-rich conditions. Such advances highlight the ability of MBE to finely tune electrical properties while maintaining excellent crystalline integrity, making it a key enabler for the development of high-performance GaN-based electronic and optoelectronic devices.

3.4. Hydride Vapor Phase Epitaxy (HVPE) and Ammonothermal Growth

Hydride Vapor Phase Epitaxy (HVPE) plays a crucial role in the fabrication of bulk GaN substrates due to its very high growth rates and ability to produce thick, low-defect crystals. While HVPE is generally not used for active photovoltaic layer deposition, it provides high-quality GaN substrates that significantly reduce threading dislocation densities in subsequent epitaxial layers grown by MOCVD, thereby indirectly enhancing device performance and reliability in space environments [107].

Hydride Vapor Phase Epitaxy (HVPE) and ammonothermal growth represent two of the most advanced techniques for producing bulk GaN crystals of high structural quality. HVPE, based on the chemical reaction between GaCl3 (generated in situ by flowing HCl over molten gallium) and NH3, is particularly attractive due to its exceptionally high growth rates, often exceeding 100 µm/h, and its capability to produce thick GaN layers with dislocation densities below 106 cm−2 [108]. Optimized HVPE processes have enabled the fabrication of freestanding GaN substrates up to several millimeters in thickness, with controlled wafer curvature and reduced stress. Importantly, recent studies demonstrated that careful reactor design and gas flow engineering can yield growth uniformity variations as low as 1% across wafers up to 50 mm in diameter [109]. Moreover, laser lift-off techniques applied to thick HVPE films grown on sapphire substrates have yielded freestanding GaN with dislocation densities in the range of 2–5 × 106 cm−2, marking a significant step toward industrial scalability [110].

In contrast, ammonothermal growth employs a solution-based approach, in which GaN is dissolved in supercritical ammonia in the presence of mineralizers (basic or acidic ammonium salts) and recrystallized onto a seed crystal under controlled thermal gradients [111]. This method is analogous to hydrothermal growth of quartz and is valued for its ability to produce crystals with extremely low dislocation densities—down to the order of 104 cm−2—alongside narrow X-ray rocking curves (31–38 arcsec) and low optical absorption coefficients (~4 cm−1 at 450 nm) [112]. Detailed studies of GaN solubility and dissolution kinetics in supercritical ammonia have further clarified the role of mineralizers in enhancing mass transport and stabilizing crystal growth [108,113,114]. More recently, computational fluid dynamics (CFD) modeling has been applied to ammonothermal autoclaves, demonstrating the critical influence of convection patterns, thermal gradients, and supersaturation control on crystal size, morphology, and uniformity [115].

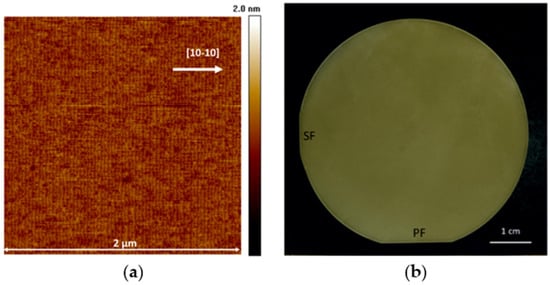

Together, HVPE and ammonothermal growth offer complementary strengths: HVPE provides unmatched deposition rates and scalability for thick wafer production, while ammonothermal growth excels in defect reduction and crystalline perfection. Their continued development remains central to overcoming substrate-related challenges in GaN-based optoelectronic and power device technologies. A representative comparison of these two approaches was provided by Grabińska et al. [111], who analyzed GaN substrates obtained via HVPE and ammonothermal growth in terms of their structural, optical, and electrical properties. The authors emphasized that HVPE remains highly attractive for commercial applications, owing to its ability to deliver thick, large-diameter substrates suitable for laser diodes and power devices. At the same time, ammonothermal GaN demonstrated markedly superior structural quality, with threading dislocation densities typically in the range of 104–105 cm−2 and X-ray rocking curve widths of 31–38 arcsec, values that approach those of native GaN single crystals. In Figure 8, representative experimental images of ammonothermal GaN substrates are presented.

Figure 8.

(a) AFM image of an as-grown ammonothermal GaN surface, demonstrating high surface uniformity and low defect density, and (b) photograph of a 2-inch ammonothermal GaN substrate with primary flat (PF) and secondary flat (SF) marked, illustrating wafer-scale quality and crystallographic orientation. Adapted from Ref. [111] under the CC BY 4.0 license.

Figure 8a shows an AFM image of the as-grown ammonothermal GaN surface, confirming its high surface uniformity and low defect density. Figure 8b displays a photograph of a 2-inch ammonothermal GaN substrate with marked primary and secondary flats, illustrating the high macroscopic quality, wafer-scale uniformity, and technological maturity of this growth method. In addition, ammonothermal-grown crystals exhibit low optical absorption coefficients (~4 cm−1 at 450 nm) and high resistivity, making them particularly suitable for optoelectronic applications requiring minimal defect-related losses. Together, these results highlight the complementary nature of HVPE and ammonothermal growth: HVPE offers scalability and cost efficiency, while ammonothermal GaN provides unmatched crystalline perfection.

Building on the previously discussed bulk growth methods, Hsiang et al. [116] examined the influence of hydrogen incorporation during Molecular Beam Epitaxy (MBE) of GaN. Their study revealed that the controlled presence of hydrogen can act as a surfactant, enhancing adatom mobility, improving surface smoothness, and reducing the density of extended defects. As a result, the GaN layers exhibited superior crystalline integrity and improved morphological quality, underlining the potential of hydrogen-assisted MBE for fabricating high-performance GaN films.

One notable advancement was introduced by Saredin et al. [117] provided an in-depth analysis of ammonothermal GaN growth, with a particular focus on the mechanisms of defect formation and their mitigation. By systematically studying the influence of process parameters such as mineralizer concentration, temperature gradients, and pressure conditions, the authors demonstrated pathways to control both point defects and extended dislocations. Their work highlighted that careful optimization of supersaturation levels and solubility kinetics is critical for suppressing defect generation during recrystallization. Importantly, the ammonothermal crystals grown under optimized conditions exhibited full widths at half maximum of X-ray rocking curves as low as 20–30 arcsec and dislocation densities approaching 104 cm−2, values that surpass those typically achievable in HVPE-grown GaN. These results confirm the capability of ammonothermal techniques to deliver substrates of exceptional crystalline perfection, reinforcing their role as a cornerstone for next-generation GaN optoelectronic and power devices.

Sochacki et al. [118] demonstrated a refined HVPE growth strategy that effectively limited unwanted lateral spreading of GaN during crystallization. By promoting preferential extension along the [0001] c-axis, the process yielded vertically elongated GaN structures with superior morphological stability and reduced defect formation. Crucially, this optimization maintained the inherently high deposition rates of HVPE, highlighting its potential for the scalable fabrication of thick, high-quality GaN substrates suitable for advanced device applications

A variety of epitaxial techniques have been developed for GaN growth, each characterized by distinct growth rates, defect densities, and scalability. To highlight the comparative advantages and limitations of these approaches, a summary is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of epitaxial growth techniques for GaN, including typical growth rates, dislocation densities, scalability, and common substrates.

As seen in Table 2, no single technique satisfies all requirements simultaneously: MOCVD remains the industrial standard, MBE provides unmatched interface control, HVPE and ammonothermal offer pathways to bulk GaN substrates, while ALD excels in conformality and precise thickness control. Ongoing research into hybrid and modified approaches (e.g., REMOCVD, MME) aims to combine these advantages and further reduce defect densities, which is critical for scaling GaN to large-area space photovoltaic applications.

4. Key Aspects in GaN Formation

4.1. Influence of Substrate Type and Quality

The substrate type and surface characteristics play a crucial role in determining the nucleation behavior, microstructural evolution, defect formation, and ultimately the functional performance of GaN layers. A notable example is provided by Santis et al. [119], who investigated the growth of cubic GaN on GaP and GaAs substrates under low-pressure MOCVD. XRD analysis revealed compressive stress in both cases, with higher structural quality achieved on GaP, as further confirmed by Raman spectra and surface morphology. The band gap of c-GaN was estimated at approximately 380 nm for both substrates, consistent with known values for the cubic phase. Extending this approach to nanoscale patterning, Li et al. [120] employed molecular dynamics simulations to evaluate GaN growth on nanopatterned AlN substrates. Introducing nanopillars significantly enhanced crystallinity by increasing the proportion of wurtzite structures and reducing dislocation density, with pillar geometry and substrate temperature identified as critical control parameters. These results demonstrate the potential of nanoscale pattern engineering to mitigate defect formation. Li et al. [121] further examined the effect of incident particle energies on crystalline quality during epitaxy. Higher energies improved surface smoothness and atomic packing but simultaneously increased dislocation nucleation height, highlighting the delicate balance between growth kinetics and internal stress. A related experimental study [122] focused on GaN growth on amorphous glass using pulsed-DC magnetron sputtering and a ZnO buffer layer. Structural analysis confirmed c-axis-oriented growth and strong near-band-edge emission, although the polycrystalline morphology and domain structure reflected inherent limitations of amorphous substrates. Dhasiyan et al. [123] employed radical-enhanced MOCVD (REMOCVD) to grow GaN on bulk GaN and GaN/Si templates. Optimizing plasma activation and minimizing radical deactivation yielded high-quality layers with XRD FWHM values as low as 72 arcsec, illustrating the strong substrate dependence of crystalline quality and the potential of low-temperature REMOCVD for GaN device structures. The influence of substrate type was also evident in the work of Kizir et al. [124], who used hollow-cathode plasma-assisted ALD to grow GaN on Si (100), Si (111), and sapphire. Although all samples exhibited wurtzite GaN, grain size, roughness, and preferred orientation varied significantly with substrate, with smoother films obtained on Si and higher growth-per-cycle values on sapphire due to enhanced nucleation behavior. Substrate surface morphology was shown to be equally critical in [125], where adjusting sapphire miscut angles enabled smooth epitaxial GaN growth under low-temperature ECR sputtering. Increasing the misorientation activated a step-flow growth mechanism, reducing surface roughness while preserving excellent crystalline quality.

Among the conventional substrates used for GaN heteroepitaxy, silicon and sapphire remain the most widely employed, but both introduce important limitations due to lattice and thermal-expansion mismatch with GaN. Sapphire offers good chemical stability and high-temperature robustness; however, the large lattice mismatch (~13–16%) and the difference in thermal-expansion coefficients generate significant tensile stress during cooldown from MOCVD growth temperatures. As the substrate and GaN layer contract at different rates, this stress promotes threading dislocations, wafer bowing, and cracking, which degrade minority-carrier lifetimes and optical performance [126]. Silicon is attractive because of its low cost, availability of large wafer diameters, and compatibility with microelectronics processing. However, the GaN/Si system suffers from an even stronger thermal-expansion mismatch. GaN expands more during growth and contracts more rapidly during cooling, leading to high tensile stress that can cause catastrophic cracking unless complex AlN/AlGaN buffer stacks are used. In addition, the large lattice mismatch (~17%) increases the density of misfit and threading dislocations, which propagate toward the surface and act as non-radiative recombination centers [127].

These mismatch-related defects have direct consequences for photovoltaic performance. They reduce carrier diffusion lengths, lower internal quantum efficiency, and accelerate degradation under thermal cycling conditions typical of space environments. Repeated temperature swings between sunlight and eclipse further increase interfacial stress, raising the risk of fatigue-related cracking and long-term device degradation. Strain accumulation also modifies polarization fields in InGaN layers, which affects carrier confinement and extraction Despite advances in GaN and InGaN growth techniques, several practical barriers remain for photovoltaic applications. A major limitation is strain accumulation caused by lattice and thermal-expansion mismatch between the epitaxial layer and the substrate. As the layer thickness increases, strain is gradually released through the formation of threading dislocations or, in extreme cases, by crack formation, especially in thick absorber layers required for efficient light absorption [128,129]. The problem becomes more pronounced for InGaN alloys with higher indium content. Increasing the In fraction lowers the bandgap and enables absorption of longer wavelengths, but it also increases lattice mismatch and internal strain. This often leads to compositional inhomogeneity, phase separation, and higher defect densities, which reduce carrier lifetime and device efficiency. As a result, there are practical limits on both the achievable indium composition and the thickness of InGaN absorber layers. Effective strain management and defect reduction therefore remain key challenges in the development of high-performance GaN-based photovoltaic devices [129,130,131].

4.2. GaN Doping and Challenges in p-Type Layer Formation

Doping plays a central role in tailoring the electrical properties of GaN and enabling its application in electronic and optoelectronic devices. In its undoped state, GaN is a wide-bandgap semiconductor with high resistivity, which makes the introduction of dopants essential for achieving controlled conductivity. N-type doping is comparatively well understood and widely implemented, with donors such as silicon (Si), oxygen (O), or germanium (Ge) providing high electron concentrations and stable electrical performance. These approaches have enabled the reliable fabrication of n-type GaN layers with low resistivity and excellent reproducibility. In contrast, the realization of efficient p-type doping remains highly problematic. The high ionization energy of typical acceptors (e.g., Mg), low solubility limits, and strong compensation effects from native defects or hydrogen incorporation make it difficult to achieve high hole concentrations and stable p-type conductivity. As a result, while n-type doping can be considered mature and technologically straightforward, the formation of p-type GaN layers continues to represent one of the most critical challenges in III-nitride semiconductor technology [132,133,134,135].

While Mg remains the most widely used acceptor for p-type GaN, its high activation energy, low solubility, and strong compensation by native defects severely limit hole concentrations. Recent studies have explored alternative dopants such as Zn and Be, but their incorporation often leads to poor thermal stability or self-compensation effects. To address these barriers, novel approaches are being developed, including co-doping strategies that combine different acceptors or donor–acceptor pairs to enhance activation, as well as polarization-assisted doping methods that exploit the strong internal electric fields in III-nitrides to lower ionization barriers. Modulation doping, in which carriers are supplied from adjacent layers rather than directly from the GaN matrix, has also been investigated as a way to bypass the inherent limitations of Mg. Although these techniques remain in the research stage, they represent promising directions for overcoming the long-standing challenge of achieving efficient and stable p-type conductivity in GaN [136,137,138,139,140].

These difficulties have direct implications for device performance, particularly in p–n junctions, LEDs, and other optoelectronic applications. In addition to the fundamental limitations of acceptor activation, the formation of high-quality p-type layers is further hindered by issues such as dopant activation, thermal stability, and interface degradation. Addressing these barriers requires advanced doping strategies, careful optimization of growth conditions, and effective post-deposition treatments, including thermal annealing or hydrogen passivation removal [141,142,143,144].

In photovoltaic applications, the challenges of p-type doping in GaN impact not only carrier concentration but also the ability to form low-resistance Ohmic contacts. Because of the wide bandgap and deep acceptor levels, Mg-doped GaN typically exhibits low hole mobility and limited activation, making it difficult to achieve sufficiently high conductivity in the p-layer [145]. This directly influences the contact resistance at the metal/semiconductor interface, as forming low-barrier Ohmic contacts on p-GaN is inherently challenging. As a result, the p-type contact often becomes a major contributor to the device’s series resistance. Increased series resistance reduces the Fill Factor (FF) and leads to power losses, ultimately limiting the achievable efficiency of GaN and InGaN-based solar cells. Therefore, the difficulty of creating both conductive and low-contact-resistance p-type GaN represents one of the most significant challenges for high-performance III-nitride photovoltaics [146,147].

A comprehensive analysis of these limitations was presented by Cheng [148], who focused on the activation issues associated with Mg doping with a focus on the limitations of magnesium as the primary acceptor species. Although Mg is widely used due to its compatibility with Ga in terms of electronic structure, its activation is significantly suppressed by the formation of Mg–H complexes, especially during MOCVD growth processes. As presented in the article, the presence of atomic hydrogen not only passivates Mg dopants but also leads to extremely high resistivity in the resulting layers, limiting their applicability in optoelectronic devices such as LEDs and LDs. The authors emphasized that the large covalent radius of Mg contributes to compensation effects, further reducing hole concentrations. Consequently, the formation of efficient p-type layers remains a key bottleneck, demanding the development of improved doping mechanisms and post-growth activation strategies to meet the performance requirements of advanced GaN-based devices.

Further technological challenges were discussed in [141], with particular emphasis on the fabrication of p-type regions in vertical GaN power devices, highlighting key technological and material challenges. In particular, the authors emphasized the importance of precisely controlling the effective acceptor concentration, which is the difference between the Mg dopant level and compensating donor species, including unintentional carbon (CN) and hydrogen (Hi). It was shown that hydrogen removal is critical for Mg activation, but prolonged annealing can lead to the formation of deep traps. As presented, the introduction of a p+ capping layer significantly enhances hydrogen out-diffusion due to the internal electric field across the p+/p− junction, reducing required annealing time and trap formation. Furthermore, the use of selective-area Mg ion implantation and subsequent ultrahigh-pressure annealing up to 1753 K under 1 GPa nitrogen atmosphere enabled high Mg activation without GaN decomposition. The study demonstrated that Mg and H diffusion is strongly influenced by UHPA parameters and vacancy dynamics, underlining the need for precise control over annealing temperature and ambient composition.

From a structural standpoint, further insight into the nature of defects in Mg-doped GaN was offered in the work by Liliental-Weber et al. [149], who employed transmission electron microscopy to compare bulk crystals grown under high-pressure and high-temperature conditions with MOCVD-grown epitaxial layers using either continuous or δ-doping methods. The results revealed that spontaneous ordering in the form of Mg-rich planar defects appeared exclusively in N-polar bulk crystals, forming stacking-fault-like structures separated by ~10.4 nm. These defects, while resembling basal stacking faults, also exhibited features consistent with inversion domains. In contrast, growth on the Ga-polar face—characterized by a significantly faster rate—resulted in three-dimensional pyramidal and rectangular void-like defects with Mg accumulation at internal surfaces. Interestingly, similar types of polarity-dependent defects were also observed in MOCVD-grown samples with δ-doping, while continuous doping appeared to suppress their formation.

An alternative approach to achieving high-conductivity p-type GaN layers was presented in the work [150], where zinc was introduced as a transition metal dopant using the thermionic vacuum arc (TVA) technique. The resulting film exhibited a polycrystalline zincblende–wurtzite structure with promising electrical properties, including low resistivity and high hole mobility. Structural and morphological characterization confirmed uniform grain distribution (200–250 nm) and high crystalline quality. The direct bandgap was red-shifted to approximately 2.9 eV, supporting effective p-type behavior. These findings suggest that Zn-doping via TVA may serve as a viable alternative to conventional Mg-based doping for the fabrication of GaN layers in nanotechnology-driven power electronics.

4.3. Crystalline Defects in GaN and Strategies for Their Reduction

Defects are deviations from the ideal periodicity of a crystal lattice and are inherently present in all semiconductors. They occur in different forms: point defects (vacancies, interstitials, etc.), line defects (dislocations), planar defects (stacking faults, twins, grain boundaries), and extended defects such as cracks or voids. From a functional perspective, defects are not merely structural irregularities—they strongly influence the electrical, optical, and mechanical properties of a material. Defect-related states inside the bandgap can act as charge carrier traps or recombination centers, thereby reducing carrier lifetime, mobility, and overall device performance. In optoelectronic devices, this manifests as reduced luminescence efficiency, while in power and photovoltaic devices, it leads to higher leakage currents, increased noise, and premature degradation under stress conditions [151,152,153].

For GaN, defects represent one of the most persistent challenges despite the outstanding intrinsic properties of this wide-bandgap (3.4 eV) semiconductor. High-quality GaN substrates are still limited and expensive, which necessitates heteroepitaxial growth on foreign substrates such as sapphire, silicon carbide or silicon. The large lattice mismatch (≈16% with sapphire, ≈17% with Si, ≈3.5% with SiC) and thermal expansion coefficient differences generate high densities of threading dislocations (TDs), typically in the range of 108–1010 cm−2 in heteroepitaxial GaN layers [154]. These dislocations propagate vertically through the active region and can act as non-radiative recombination centers in LEDs [155] or leakage paths in HEMTs [156]. Point defects such as nitrogen vacancies are known to create deep donor states close to the conduction band, reducing radiation hardness and long-term reliability of GaN-based devices [157].

The quality of GaN growth directly affects the performance of GaN power devices used in space energy-conversion circuits. Low dislocation density, controlled impurity incorporation, and smooth morphology are important in terms of achieving high breakdown voltages, low leakage currents as well as stable 2DEG characteristics in GaN HEMTs and Schottky diodes. Growth techniques such as MOCVD, HVPE, ELO, and pendeo-epitaxy improve uniformity and interface quality which translates into higher switching efficiency and thermal reliability. These methods support both high-quality InGaN absorbers and reliable GaN power electronics for space energy-conversion systems.

To address these issues, multiple defect-reduction strategies have been developed. A foundational approach involves the use of buffer layers, for instance, low-temperature GaN nucleation layers or AlN interlayers, which help accommodate strain and reduce dislocation density during subsequent growth. More advanced methods such as epitaxial lateral overgrowth [158,159,160] and pendeo-epitaxy redirect dislocations laterally or terminate them at mask edges, enabling a significant reduction in TD densities down to 106–107 cm−2 [161,162,163].

Epitaxial growth techniques themselves are also subject to extensive optimization for defect reduction. In metal–organic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD), parameters such as growth temperature, V/III precursor ratio, and reactor pressure strongly influence the incorporation of point defects and the evolution of surface morphology. For example, optimized V/III ratios can suppress nitrogen vacancies and improve film stoichiometry, while higher growth temperatures generally reduce impurity incorporation, although excessively high temperatures may induce nitrogen desorption and surface roughening. Molecular beam epitaxy (MBE), although inherently slower (typically <1–2 µm/h), offers unmatched precision in controlling composition and doping profiles, which helps in engineering sharp heterointerfaces and minimizing interface-related defects. Post-growth treatments provide an additional pathway for defect management. Thermal annealing can promote defect annihilation or passivation, while chemical treatments (e.g., surface oxidation, hydrogen or plasma passivation) can neutralize electrically active defect states. Moreover, the deposition of dielectric passivation layers such as SiNX or Al2O3 is often employed to suppress surface states and improve carrier lifetimes in GaN devices. Advances in defect characterization have played a crucial role in guiding these strategies. High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) enables direct imaging of dislocations and stacking faults, while XRD and reciprocal space mapping (RSM) provide statistical measures of dislocation densities and strain. Techniques such as cathodoluminescence (CL) and photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy can spatially map non-radiative centers, and deep-level transient spectroscopy (DLTS) allows the identification of electrically active traps [164,165,166,167,168].

Collectively, these mitigation strategies have significantly improved GaN material quality, supporting its evolution from a laboratory curiosity to a pillar of the LED lighting revolution and a core technology in high-power RF transistors. More recently, work has begun on developing GaN components and devices with enhanced radiation tolerance, particularly for space or near-space applications. While fully mature radiation-hardened GaN photovoltaics remain at an earlier stage, the advances in defect reduction, passivation, and processing lay a solid foundation for their eventual realization. Nonetheless, defect reduction remains a central research frontier—especially for large-area, low-cost GaN substrates necessary for mass deployment in power electronics and space solar cell arrays [169,170,171].

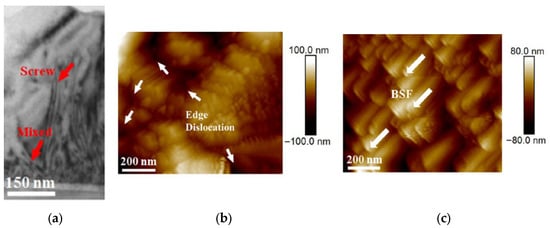

Quantitative correlations between crystalline defect density and device performance have been clearly demonstrated in GaN-based heterostructures grown on different substrates. For example, Pharkphoumy et al. [172] compared AlGaN/GaN HEMTs fabricated on silicon and sapphire substrates and directly linked structural quality to electrical characteristics. High-resolution X-ray diffraction revealed significantly narrower rocking-curve full width at half maximum (FWHM) values for GaN grown on sapphire (368 arcsec) compared with silicon (703 arcsec), indicating a substantially lower threading dislocation density in the sapphire-based structures. This improvement in crystalline quality translated directly into enhanced device performance. AlGaN/GaN HEMTs on sapphire exhibited higher drain current densities (155 mA/mm vs. 150 mA/mm at VGS = 0 V without passivation) and superior breakdown voltages (415 V on sapphire compared with 245 V on silicon). After SiO2 passivation, which suppresses surface trap-assisted leakage, the breakdown voltage increased to 425 V on sapphire and 400 V on silicon, further highlighting the combined influence of defect density and interface quality on high-field operation. The same study also demonstrated that higher defect densities induce self-heating effects and limit transconductance at elevated bias. Devices grown on silicon showed a more rapid degradation of transconductance at higher gate voltages, consistent with increased defect-assisted scattering and inferior thermal dissipation. Atomic force microscopy confirmed a much smoother GaN surface on sapphire (RMS roughness ≈ 0.88 nm) compared with silicon (≈2.96 nm), reinforcing the link between microstructural quality and carrier transport. Complementary evidence is provided by Yang et al. [173], who analyzed the influence of dislocation density on GaN-based device reliability and performance under electrically and thermally demanding conditions. Using X-ray rocking curves (XRC), cross-sectional TEM, and AFM after selective etching, the authors quantified screw and mixed dislocation densities. In Figure 9, representative XRC, cross-sectional TEM, and AFM images illustrate the direct relationship between defect type, defect density, and GaN device performance.

Figure 9.

Representative experimental characterization of nonpolar GaN: (a) cross-sectional TEM image showing screw and mixed dislocations; (b) AFM image after selective etching revealing edge dislocations; (c) AFM image highlighting basal stacking faults (BSFs). The data demonstrate the correlation between defect density and GaN device performance. Reproduced from Ref. [173], with the permission of AIP Publishing.

Clear correlations between crystalline defects and device metrics were demonstrated. Higher screw and mixed dislocation densities led to increased leakage current due to barrier-height lowering and current paths along dislocation cores, while edge dislocations and BSFs primarily reduced responsivity through enhanced carrier scattering and non-radiative recombination. Devices fabricated on GaN layers with lower overall defect densities exhibited improved electrical stability, lower dark current, and higher responsivity under high electric fields and thermal stress.

4.4. Substrate Reuse and Recycling Strategies for Scalable Low-Defect GaN Epitaxy

Owing to the high production cost and limited availability of freestanding GaN substrates, as well as the growing strategic importance of GaN wafer supply for next-generation electronics, several recycling and substrate-reclaim pathways have recently attracted specific attention as a strategy to reduce material scarcity risks. Although large-scale end-of-life recycling of GaN devices remains at an early stage of development, multiple substrate-reclaim approaches are relatively advanced. For instance, laser lift-off (LLO), already established in the LED industry, enables the separation of GaN epilayers from sapphire while preserving the underlying substrate for subsequent re-polishing and reuse [174]. Complementary approaches—including chemical and electrochemical lift-off, sacrificial interlayers, and selective etching processes—have been developed to detach epitaxial GaN from native GaN, SiC or sapphire while maintaining surface planarity and low defect density. Additional methods such as hydride-vapor-phase and plasma etching to remove residual GaN, together with emerging schemes aimed at regrowth on recovered templates, further demonstrate the feasibility of reducing raw-wafer consumption [175,176,177,178,179].

Beyond reclaim, several chemical recycling approaches have also been investigated to recover GaN from waste LED, RF and power-electronics devices. These methods typically involve selective leaching using acidic, alkaline, or complexing solutions that remove surface metallization and packaging residues while leaving the GaN material largely intact. Such chemical purification enables the isolation of clean GaN fragments suitable for further processing or reuse and represents a promising complementary pathway for reducing material consumption within the GaN value chain [180,181].

Importantly, these cost- and material-saving strategies interface directly with established defect-reduction techniques in GaN epitaxy—most notably epitaxial lateral overgrowth (ELO) and pendeo-epitaxy. Both methods rely on selective-area or sidewall-initiated growth to bend, block, and annihilate threading dislocations, thus lowering dislocation densities by one to two orders of magnitude compared to planar heteroepitaxy. By enabling the fabrication of low-defect-density GaN and InGaN templates on large-area, relatively low-cost substrates such as sapphire or SiC, ELO and pendeo-epitaxy significantly improve scalability for space photovoltaics [182,183,184,185,186].

When combined with substrate lift-off and reuse, these approaches offer a synergistic path toward lowering the effective cost per wafer while maintaining the high crystalline quality required for radiation-hardened, long-lifetime space-PV absorber structures. Together, defect-reduction epitaxy and substrate recycling constitute a critical technological foundation for advancing GaN-based space photovoltaics from laboratory-scale demonstrations toward economically viable multi-wafer manufacturing.

4.5. Semi-Polar and Non-Polar GaN Orientations

Semi-polar and non-polar GaN orientations have become increasingly important for high-In-content InGaN absorbers, as they significantly reduce or eliminate the polarization fields present in conventional c-plane (0001) GaN. Orientations such as semi-polar

and

, as well as non-polar

and

, suppress the quantum-confined Stark effect (QCSE), leading to improved electron–hole wavefunction overlap, enhanced radiative efficiency, and more efficient carrier extraction. This reduction in internal fields allows the incorporation of higher indium fractions without severe strain-driven defect formation, enabling InGaN bandgaps below ~1.5 eV required for the low-energy junctions in multi-junction solar cells [187,188,189,190,191].