Abstract

Growing evidence supports the role of probiotics in reducing the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis, time to achieve full enteral feeding, and late-onset sepsis (LOS) in preterm infants. As reported for several neonatal clinical outcomes, recent data have suggested that nutrition might affect probiotics’ efficacy. Nevertheless, the currently available literature does not explore the relationship between LOS prevention and type of feeding in preterm infants receiving probiotics. Thus, the aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to evaluate the effect of probiotics for LOS prevention in preterm infants according to type of feeding (exclusive human milk (HM) vs. exclusive formula or mixed feeding). Randomized-controlled trials involving preterm infants receiving probiotics and reporting on LOS were included in the systematic review. Only trials reporting on outcome according to feeding type were included in the meta-analysis. Fixed-effects models were used and random-effects models were used when significant heterogeneity was found. The results were expressed as risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). Twenty-five studies were included in the meta-analysis. Overall, probiotic supplementation resulted in a significantly lower incidence of LOS (RR 0.79 (95% CI 0.71–0.88), p < 0.0001). According to feeding type, the beneficial effect of probiotics was confirmed only in exclusively HM-fed preterm infants (RR 0.75 (95% CI 0.65–0.86), p < 0.0001). Among HM-fed infants, only probiotic mixtures, and not single-strain products, were effective in reducing LOS incidence (RR 0.68 (95% CI 0.57–0.80) p < 0.00001). The results of the present meta-analysis show that probiotics reduce LOS incidence in exclusively HM-fed preterm infants. Further efforts are required to clarify the relationship between probiotics supplementation, HM, and feeding practices in preterm infants.

1. Introduction

Late onset sepsis (LOS) is one of the most common causes of morbidity and mortality in preterm infants [1,2]. It occurs in approximately 20% of very low birth weight (VLBW) infants, has a significant overall mortality [3], and a high risk of long-term neurodevelopmental sequelae [4].

Beyond an immature skin-mucosal barrier and immune response, other well-recognized risk factors for LOS include long-term use of invasive interventions, failure of early enteral feeding with breast milk, prolonged duration of parenteral nutrition, hospitalization, surgery, and underlying respiratory and cardiovascular diseases [2].

Growing evidence supports the key role of a healthy gut microbiota in promoting and maintaining a balanced immune response and in the establishment of the gut barrier in the immediate postnatal life [5]. However, in preterm infants, the development of the microbial community is disrupted by events related to prematurity: Mode of delivery, antenatal and postnatal use of antibiotics, minimal exposure to maternal flora, and low intake of breast milk [6]. Such disruption, called dysbiosis, results in an altered barrier and immune function and an imbalance between pro- and anti-inflammatory responses, and has been associated with necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) and LOS [7,8].

Probiotics, defined as live micro-organisms that confer health benefits to the host through an interaction with gut microbiota and immune function when administered at adequate doses [9], have been proposed as potential tools to prevent NEC and LOS [10].

Updated meta-analyses confirm the benefits of probiotics in reducing the risk of NEC [11,12], the time to achieve full enteral feeding [13,14], and the risk of LOS [15,16] in preterm infants. However, most of these meta-analyses fail to explore the role of probiotics in deeper detail, and do not provide specific recommendations regarding which probiotic strain or mixture of strains should be used, and which population would benefit most from the use of probiotics.

Gut colonization in human milk (HM)-fed preterm infants is different from that of formula-fed infants [17]. HM provides nutrients, prebiotic carbohydrates, endogenous probiotics, and a variety of bioactive factors that exert beneficial effects directly and indirectly on host-gut microbiota interactions [18]. Recent data suggest that probiotic efficacy might be dependent upon the type of feeding; specifically, only preterm infants receiving HM would benefit from probiotic use in terms of a lower risk of NEC [19] and a reduction in the time needed to achieve full enteral feeding [13]. Furthermore, in vitro studies have shown that the growth of some probiotic species is enhanced in the presence of HM oligosaccharides (HMOs) [20,21]. Despite these suggestions, however, only a few randomized controlled trials (RCTs) report the type of feeding in infants given probiotics; and also for this reason, meta-analyses are unable to make any consideration about the influence of type of feeding in reducing adverse outcomes, such as NEC or LOS, in preterm infants receiving probiotics [13,16].

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is thus to evaluate the effect of probiotics for the prevention of LOS in preterm infants according to type of feeding (exclusive HM vs. exclusive formula or mixed feeding).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search

The study protocol was designed by the members of the Task Force on Probiotics of the Italian Society of Neonatology. A systematic review of published studies reporting the use of probiotics for the prevention of LOS in preterm infants, according to type of feeding, was performed in accordance with PRISMA guidelines [22].

The characteristics of the studies included in the systematic review were the following: Randomized and quasi-randomized controlled trials involving preterm infants (gestational age (GA) <37 weeks) who had received, within one month of age, any probiotic compared to placebo or no treatment. The outcome of interest was culture-proven LOS, defined as the presence of a positive blood or cerebrospinal fluid culture taken >72 h after birth.

PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/), the Cochrane Library (http://www.cochranelibrary.com/) and Embase (http://www.embase.com/) were interrogated for studies published before 28 October 2016. The following string was used to perform the PubMed search: ((infant OR infants) OR (neonate OR neonates) OR (newborn OR newborns) AND (septi* OR sepsi* OR sepsis) OR (bacterial infect* OR bacterial infections (MH)) AND (probiotic OR probiotics OR pro-biotic OR pro-biotics)) NOT (animals (MH) NOT humans (MH)). The string was built up by combining all the terms related to LOS and probiotics, using PubMed MeSH terms, free-text words, and their combinations through the most proper Boolean operators, in order to be as comprehensive as possible. Similar criteria were used for searching the Cochrane Library and Embase. The review was restricted to English-written studies involving human subjects.

Luca Maggio (LM), Giovanni Barone (GB), Arianna Aceti (AA), and Isadora Beghetti (IB) performed the literature search. Potentially eligible studies were identified from the abstracts; the full texts of relevant studies were assessed for inclusion and their reference lists were searched for additional studies.

2.2. Data Extraction and Meta-Analysis

Study details (population, characteristics of probiotic and placebo, type of feeding, and outcome assessment) were evaluated independently by LM, GB, AA, and IB, and checked by Davide Gori (DG). Study quality was evaluated independently by AA, IB, and DG using the risk of bias tool as proposed by the Cochrane collaboration (Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews) [23]. In addition, an assessment of the quality of evidence using the GRADE working group approach was performed [23]. The evaluation was carried out by DG following Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook [23] and classifying the evidence as high, moderate, low, and very low (as suggested by the GRADE Working Group) [24].

When outcome data were not reported according to type of feeding, the corresponding authors of the papers were contacted by email and were asked to provide separate data for LOS incidence in infants receiving probiotics vs. placebo according to type of feeding (exclusive HM vs. exclusive formula or mixed feeding). If the corresponding author was unable to provide these data or did not reply to the email, the paper was excluded from the meta-analysis.

The association between probiotic use and LOS was evaluated by a meta-analysis conducted by AA, IB, and DG using the RevMan software (version 5.3, downloaded on 1 November 2016 from the Cochrane website: http://tech.cochrane.org/revman/download). Risk ratio (RR) was calculated using the Mantel–Haenszel method and reported with a 95% confidence interval (CI). A fixed-effect model was used for the analyses. Heterogeneity was assessed using the χ2 test and I2 statistic: If significant heterogeneity was found (p < 0.05 from the χ2 test) or the number of studies was lower than five, a random-effects model was used instead [23].

The results of the meta-analysis were presented using forest plots, while a funnel plot was used for investigating publication bias.

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search

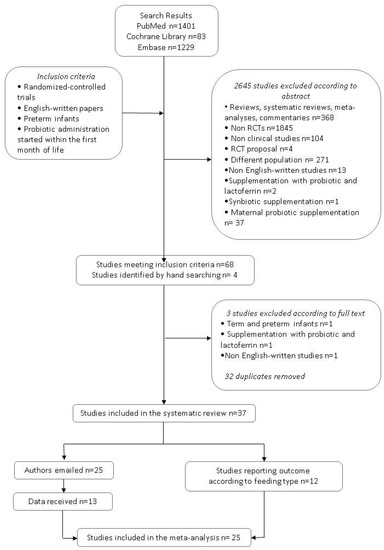

The number of potentially relevant papers identified through the literature search was 2713 (1401 in PubMed, 83 in the Cochrane Library, and 1229 in Embase).

As shown in Figure 1, 68 papers met the inclusion criteria (35 in PubMed, 13 in the Cochrane Library search, and 20 in Embase). Four additional studies were identified by a manual search of the reference lists of included studies. Among these 72 studies, 32 were excluded as they were duplicates retrieved by at least two search engines. Three studies were excluded after examining the full texts: One study included both term and preterm infants [25], one study reported supplementation with probiotic plus bovine lactoferrin [26], and one study was not written in English [27].

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the search strategy and search results. The relevant number of papers at each point is given.

Finally, 37 studies were eligible for the systematic review [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64]. Details of the included studies are reported in Table 1; excluded studies are described in Table 2.

Table 1.

Studies included in the systematic review.

Table 2.

Studies excluded from the systematic review.

For each included study, the LOS rate in the probiotic and in the placebo/control group is reported in Table 3. The study by Dutta et al. [37] was reported three times, as it included three groups of patients supplemented with a probiotic given at three different doses. Data from the study of Hays et al. [39] were reported three times because three different interventions (Bifidobacterium lactis alone, Bifidobacterium longum alone, and B. lactis plus B. longum) were evaluated. The study by Romeo et al. [53] was reported twice, as it compared two different probiotics to placebo (Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC 55730 and Lactobacillus rhamnosus ATCC 53103), and the one by Tewari et al. [62] was reported twice because its participants were stratified as very preterm and extremely preterm.

Table 3.

Incidence of late-onset sepsis (LOS) in infants treated with probiotics and in control.

Among the eligible studies, only twelve reported LOS according to feeding type during the study period: Eight studies reported LOS in exclusively HM-fed infants, either own mother’s milk (OMM) or donor human milk (DHM) [30,43,44,46,55,57,60,62], while four studies included exclusively formula-fed infants [31,32,61,64].

The corresponding authors of the remaining twenty-five studies were contacted by e-mail: data were provided for thirteen studies [28,36,37,38,39,42,49,50,51,52,56,58,59].

Twenty-five [28,30,31,32,36,37,38,39,42,43,44,46,49,50,51,52,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,64] studies were finally suitable for inclusion in the meta-analysis.

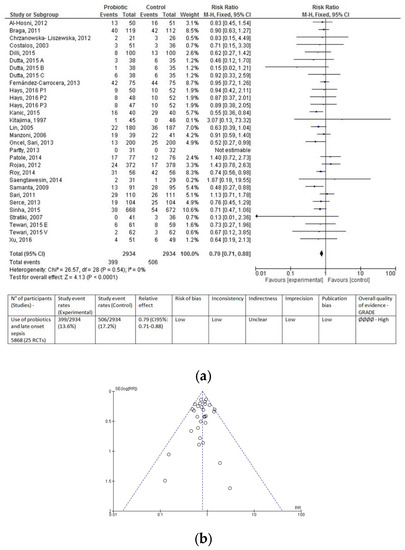

3.2. Probiotic and LOS: Overall Population

Overall, data from 5868 infants (2934 in the probiotic group and 2934 in the control group) were evaluated. Regardless of type of feeding, fewer infants in the probiotic group developed LOS compared to infants in the control group (399 (13.60%) vs. 506 (17.24%), respectively). Probiotic supplementation resulted in a significantly lower incidence of LOS (RR 0.79 (0.71–0.88), p < 0.0001; Figure 2a). Number needed to treat was 28. In other words, 28 infants would need to receive probiotic supplementation in order to prevent one additional case of LOS. The funnel plot did not show any clear asymmetry (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Forest plot (a) and funnel plot (b) of the included studies. The forest plot shows the association between the use of probiotics and late onset sepsis in the overall population of preterm infants. The evaluation of the overall results of the meta-analysis according to the GRADE approach is reported below the forest plot. The funnel plot does not show any clear visual asymmetry. M–H: Mantel–Haenszel method; RR, risk ratio; CI, confidence interval.

3.3. Probiotic and LOS According to Type of Feeding

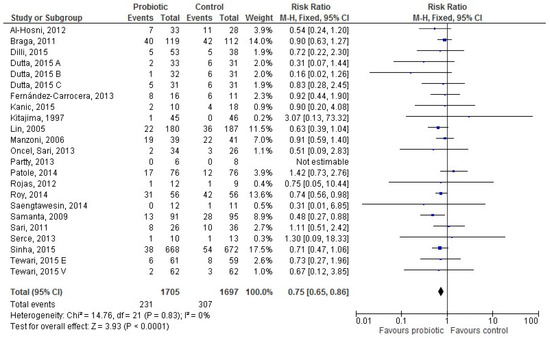

The data were then analyzed according to type of feeding (exclusive HM, exclusive formula, or mixed feeding).

Twenty studies [28,30,36,37,38,42,43,44,46,49,50,51,52,55,56,57,58,59,60,62] provided data for 3402 exclusively HM-fed infants (1705 in the probiotic and 1697 in the control group). LOS occurred less frequently in HM-fed infants receiving probiotics than in controls (231 (13.55%) infants vs. 307 (18.09%), respectively); the RR was 0.75 ((95% CI 0.65–0.86), p < 0.0001), and heterogeneity among studies was absent (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The forest plot shows the association between the use of probiotics and late onset sepsis in the twenty studies reporting data for exclusively human milk-fed preterm infants. M–H: Mantel–Haenszel method.

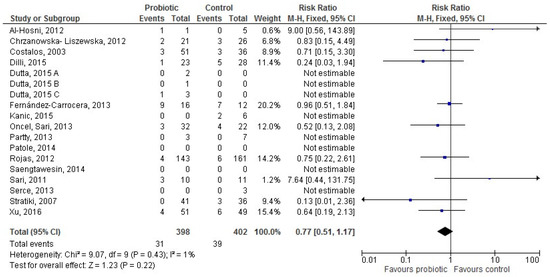

Sixteen [28,31,32,36,37,38,42,49,50,51,52,56,58,59,61,64] studies provided data for 800 exclusively formula-fed infants (398 in the probiotic and 402 in the control group). The difference in LOS incidence between groups was not significant (RR 0.77 (95% CI 0.51–1.17), p = 0.22; Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The forest plot shows the association between the use of probiotics and late onset sepsis in the sixteen studies reporting data for exclusively formula-fed preterm infants. M–H: Mantel–Haenszel method.

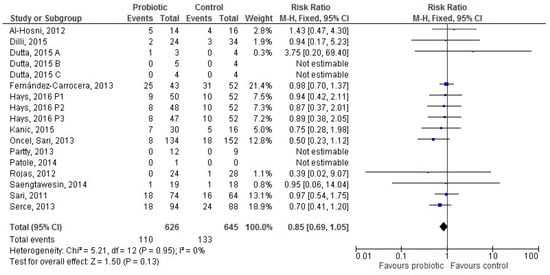

Thirteen [28,36,37,38,39,42,49,50,51,52,56,58,59] studies provided data for 1271 infants receiving mixed feeding (626 in the probiotic and 645 in the control group). The difference in LOS incidence between groups was not significant (RR 0.85 (95% CI 0.69–1.05), p = 0.13; Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The forest plot shows the association between the use of probiotics and late onset sepsis in the thirteen studies reporting data for preterm infants receiving mixed feeding. M–H: Mantel–Haenszel method.

In order to examine in deeper detail the effect of probiotics in HM-fed infants, sub-meta-analyses restricted according to population and probiotic characteristics, as well as study quality, were performed.

3.3.1. Population Characteristics: VLBW and Extremely Low Birth Weight (ELBW) Infants

Fifteen [28,36,38,42,43,44,46,49,51,52,56,57,58,59,62] studies reported data for 1516 exclusively HM-fed VLBW infants (760 in the probiotic and 756 in the control group). LOS occurred less frequently in infants given probiotics than in controls (114 (15%) infants vs. 151 (19.97%)), with an RR of 0.76 (95% CI 0.62–0.94; p = 0.01; I2 = 0%; fixed-effect model).

Only two studies reported specific data on LOS in ELBW infants. One study [28] included only ELBW infants, who received exclusive HM or mixed feeding; the other one [62] recruited both VLBW and ELBW infants, who were exclusively HM-fed. In these studies, probiotic supplementation did not show any significant benefit in terms of LOS compared to a placebo.

3.3.2. Probiotic Characteristics

Ten studies [28,30,37,38,42,44,55,56,57,60] reported data for 2560 HM-fed infants who received a probiotic mix (1281 infants) vs. placebo/no treatment (1279 infants). LOS occurred less frequently in infants given probiotics than in controls (169 (13.2%) infants vs. 242 (18.9%)), with an RR of 0.68 (95% CI 0.57–0.80; p < 0.00001; I2 = 0%; fixed-effect model).

Four studies [46,49,50,52] reported data for 175 HM-fed infants who received a single-strain Lactobacillus probiotic (91 infants) vs. placebo/no treatment (84 infants). No difference between groups in the incidence of LOS was documented (RR 0.87 (95% CI 0.58–1.32); p = 0.63; I2 = 0%; random effects model). Lactobacillus strains differed among studies: Lactobacillus rhamnosus was used in two studies [46,50] and Lactobacillus reuteri in two studies [49,52]. Lactobacillus sporogenes was used in one study [58], showing no differences between groups in LOS incidence; this latter study was not included in the pooled analysis, as L. sporogenes is a species which has not found international recognition, shows characteristics of both genera Lactobacillus and Bacillus, and its strain should be better classified as Bacillus coagulans [65].

Three studies [36,43,51] reported data for 334 HM-fed infants who received a single-strain Bifidobacterium probiotic (174 infants) vs. placebo/no treatment (160 infants). No difference between groups in the incidence of LOS was documented (RR 1.23 (95% CI 0.70–2.18); p = 0.47; I2 = 0%; random effects model). Bifidobacterium strains differed among studies: Bifidobacterium breve was used in two studies [43,51] and Bifidobacterium lactis in one study [36].

Saccharomyces boulardii was used in one study [59], as well as Bacillus clausii [62]: None of these studies showed a significant difference between infants treated with probiotics and controls in the incidence of LOS.

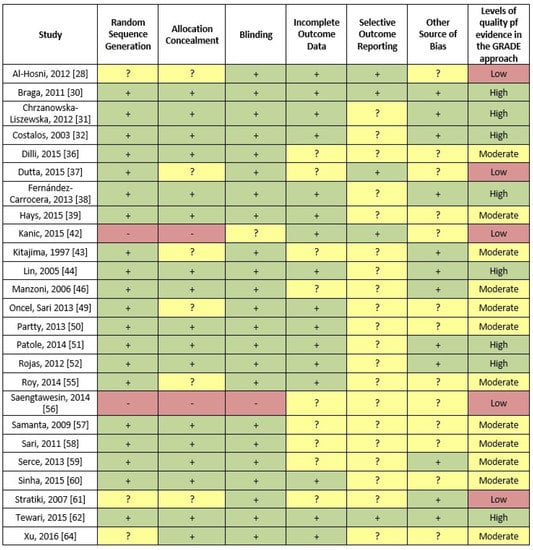

3.4. Methodological Study Quality

The quality assessment of the studies included in the meta-analysis according to the risk of bias tool as proposed by the Cochrane collaboration is shown in Figure 6. The last column of the Figure also shows the assessment of the body of evidence using the GRADE working group approach.

Figure 6.

Evaluation of the quality of the studies included in the meta-analysis according to the risk of bias tool as proposed by the Cochrane collaboration (red represents a high risk of bias, yellow an unclear risk of bias and green a low risk of bias). In addition, the last column shows the assessment an assessment of the body of evidence using the GRADE working group approach.

Following a methodology similar to that used in the meta-analysis by Rao et al. [15], we conducted a sensitivity analysis including only studies which had a low risk of bias in both random sequence generation and allocation concealment. Sixteen studies [30,31,32,36,38,39,44,46,50,51,52,57,58,59,60,62] were included and reported data for 4628 infants (2306 in the probiotic and 2322 in the control group). The results were similar to those of the overall meta-analysis: LOS occurred less frequently in infants receiving probiotics than in controls (309 (13.4%) infants vs. 366 (15.76%)) with an RR of 0.85 (95% CI 0.75–0.97; p = 0.02; I2 = 0%; fixed effect model).

4. Discussion

In line with the results of previous papers [15,16], the present meta-analysis showed an overall benefit of probiotic supplementation for the prevention of LOS in preterm infants. However, when data were analyzed according to type of feeding, the beneficial effect of probiotics in reducing LOS was confirmed only in exclusively HM-fed preterm and VLBW infants, but not in infants receiving formula. Statistical heterogeneity among studies was almost absent and a low risk of publication bias was documented.

Two recent meta-analyses investigating the effect of probiotic supplementation on LOS in preterm infants reported an overall decrease in the risk of LOS in infants receiving probiotics compared to controls [15,16]. The studies included in the meta-analyses by Rao [15] and Zhang [16] are almost the same as those included in our updated systematic review; in the majority of the studies, both HM- and formula-fed infants were recruited, but no detailed data on the relationship between type of feeding and outcome were published.

Several data suggest that the impact of the type of feeding on clinical outcome in preterm infants is likely to be relevant [66]: It has been previously shown that HM feeding, per se, is associated with a reduction of the risk of developing LOS [67] and with a shorter time to achieve full enteral feeding in VLBW infants [68]. In addition, the use of probiotics in HM-fed, but not in formula-fed, infants appears to be related to a lower risk of NEC [19] and an earlier achievement of full enteral feeding [13].

It is plausible that the effect of probiotics on clinical outcomes could be mediated by HM properties [69]; actually, several HM components, including prebiotic HMOs, growth factors, immunological factors, and probiotic bacteria, can drive the establishment of a beneficial gut microbiota. In addition, HM can constitute the ideal soil for exogenous probiotics and promote a more effective crosstalk among probiotics, gut microbiota, and the developing immune system.

According to the latest recommendations, all preterm infants should receive exclusive HM; OMM is the best nutritional choice, and pasteurized DHM should be preferred to formula when OMM is not available or is contraindicated [70]. However, providing an exclusive HM diet to preterm infants presents a variety of challenges related to the prematurity itself and to hospitalization [71]. The term “exclusive HM feeding” may cover a range of feeding practices beyond direct breastfeeding, such as the use of fresh vs. frozen expressed breast milk given by bottle or tube feeding, the addition of HM fortifiers, and a variable duration of exclusive HM feeding. As described for pasteurization [72], some of these interventions might affect the nutritional and non-nutritional components of HM. In this perspective, the beneficial effect of probiotic supplementation in exclusively HM-fed infants might be related to a synergic action exerted by exogenous probiotics together with the prebiotic components of HM, which could partially restore the symbiotic potential of breast milk.

The data about exclusively HM-fed infants were analyzed according to population and probiotic characteristics in order to evaluate which preterm infants would benefit more from probiotic use and which probiotic strain or mixture of strains would be more beneficial. While there is evidence that probiotics are effective in reducing LOS in VLBW infants, no definite conclusion could be drawn for ELBW infants, as only two studies reported specific data on LOS in these infants, who remain the highest-risk and most vulnerable population.

The currently available literature does not provide a definite recommendation on which probiotic strain or mixture would be more effective in reducing LOS. In the 25 included studies, different probiotic strains and mixtures were used. Consistently with previous papers [12,16,73], our meta-analysis indicated that a mixture of different probiotic strains might be more effective in reducing LOS in exclusively HM-fed preterm infants. A possible explanation for this finding is that a probiotic mixture would provide a better ecological barrier and a more diverse immunological stimulation than a single strain.

The possible limitations of the present meta-analysis should be taken into consideration. Thirty-seven studies were potentially eligible for the meta-analysis, but only 25 studies provided separated data according to feeding type. In addition, infants’ classification according to feeding type was not homogeneous across studies, and the meta-analysis had to rely on unpublished information provided by the authors themselves. Finally, although no statistical heterogeneity was found, the characteristics of probiotic administration (dose, duration, time of initiation, and probiotic micro-organisms) differed among the included studies.

More importantly, no separate data for OMM-fed and DHM-fed infants were available; as a result, it was not possible to clarify whether the “synergic” effect of HM and probiotics applies to both OMM and DHM. It remains also unclear whether HM feeding, either OMM or DHM, has a “dose and time-dependent” effect on probiotic supplementation, as reported for outcomes such as NEC [66].

Probiotics appear to be generally safe, but it has to be acknowledged that there are some reports about the occurrence of sepsis in preterm newborns potentially linked to probiotic supplementation [74]. None of the studies included in the systematic review reported any side effect related to probiotic administration.

5. Conclusions

According to the results of the present meta-analysis, probiotic supplementation reduces the risk of LOS in exclusively HM-fed preterm infants. An exclusive HM diet should be the gold standard for all preterm, VLBW infants. Since direct breastfeeding is almost impossible in this population, it is likely that manipulations of HM, including pasteurization, refrigeration, and administration by tube or bottle, could affect HM bioactive properties; in this context, the administration of exogenous probiotics could help in restoring, at least partially, HM symbiotic properties.

Future research should be aimed at clarifying the relationship between feeding practices and probiotic supplementation, and at addressing the choice of the most effective probiotic products to be used in exclusively HM-fed infants.

Author Contributions

All the authors approved the submission of this version of the manuscript and take full responsibility for the manuscript. Specifically, all the authors, as part of the Task Force on Probiotics of the Italian Society of Neonatology, conceived and designed the study protocol. L.M., G.B., A.A., and I.B. performed the literature search and assessed study details, which were checked by D.G., A.A., and I.B., and D.G. evaluated study quality and performed the meta-analysis. A.A. and I.B. wrote the first draft of the paper, which was critically revised by all the other authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Liu, L.; Johnson, H.L.; Cousens, S.; Perin, J.; Scott, S.; Lawn, J.E.; Rudan, I.; Campbell, H.; Cibulskis, R.; Li, M.; et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: An updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. Lancet 2012, 379, 2151–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Speer, C.P. Late-onset neonatal sepsis: Recent developments. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2015, 100, F257–F263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoll, B.J.; Hansen, N.; Fanaroff, A.A.; Wright, L.L.; Carlo, W.A.; Ehrenkranz, R.A.; Lemons, J.A.; Donovan, E.F.; Stark, A.R.; Tyson, J.E.; et al. Late-onset sepsis in very low birth weight neonates: The experience of the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics 2002, 110, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoll, B.J.; Hansen, N.I.; Adams-Chapman, I.; Fanaroff, A.A.; Hintz, S.R.; Vohr, B.R.; Higgins, R.D.; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Neurodevelopmental and growth impairment among extremely low-birth-weight infants with neonatal infection. JAMA 2004, 292, 2357–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collado, M.C.; Cernada, M.; Neu, J.; Pérez-Martínez, G.; Gormaz, M.; Vento, M. Factors influencing gastrointestinal tract and microbiota immune interaction in preterm infants. Pediatr. Res. 2015, 77, 726–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berrington, J.E.; Stewart, C.J.; Embleton, N.D.; Cummings, S.P. Gut microbiota in preterm infants: Assessment and relevance to health and disease. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2013, 98, F286–F290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, C.J.; Marrs, E.C.L.; Magorrian, S.; Nelson, A.; Lanyon, C.; Perry, J.D.; Embleton, N.D.; Cummings, S.P.; Berrington, J.E. The preterm gut microbiota: Changes associated with necrotizing enterocolitis and infection. Acta Paediatr. 2012, 101, 1121–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, V.; Torrazza, R.M.; Ukhanova, M.; Wang, X.; Sun, Y.; Li, N.; Shuster, J.; Sharma, R.; Hudak, M.L.; Neu, J. Distortions in development of intestinal microbiota associated with late onset sepsis in preterm infants. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e52876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, M.E.; Guarner, F.; Guerrant, R.; Holt, P.R.; Quigley, E.M.; Sartor, R.B.; Sherman, P.M.; Mayer, E.A. An update on the use and investigation of probiotics in health and disease. Gut 2013, 62, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slattery, J.; Macfabe, D.F.; Frye, R.E. The significance of the enteric microbiome on the development of childhood disease: A review of prebiotic and probiotic therapies in disorders of childhood. Clin. Med. Insights Pediatr. 2016, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlFaleh, K.; Anabrees, J. Probiotics for prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 9, 584–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceti, A.; Gori, D.; Barone, G.; Callegari, M.L.; Di Mauro, A.; Fantini, M.P.; Indrio, F.; Maggio, L.; Meneghin, F.; Morelli, L.; et al. Probiotics for prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2015, 41, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aceti, A.; Gori, D.; Barone, G.; Callegari, M.L.; Fantini, M.P.; Indrio, F.; Maggio, L.; Meneghin, F.; Morelli, L.; Zuccotti, G.; et al. Probiotics and time to achieve full enteral feeding in human milk-fed and formula-fed preterm infants: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athalie-Jape, G.; Deshpande, G.; Rao, S.; Patole, S. Benefits of probiotics on enteral nutrition in preterm neonates-a systematic review. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2014, 50, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, S.C.; Athalye-Jape, G.K.; Deshpande, G.C.; Simmer, K.N.; Patole, S.K. Probiotic Supplementation and Late-Onset Sepsis in Preterm Infants: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20153684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.-Q.; Hu, H.-J.; Liu, C.-Y.; Shakya, S.; Li, Z.-Y. Probiotics for Preventing Late-Onset Sepsis in Preterm Neonates: A PRISMA-Compliant Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Medicine 2016, 95, e2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlisle, E.M.; Morowitz, M.J. The intestinal microbiome and necrotizing enterocolitis. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2013, 25, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco, A.R.; Barile, D.; Underwood, M.A.; Mills, D.A. The impact of the milk glycobiome on the neonate gut microbiota. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2015, 3, 419–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Repa, A.; Thanhaeuser, M.; Endress, D.; Weber, M.; Kreissl, A.; Binder, C.; Berger, A.; Haiden, N. Probiotics (Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium bifidum) prevent NEC in VLBW infants fed breast milk but not formula. Pediatr. Res. 2015, 77, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, R.E.; Ninonuevo, M.; Mills, D.A.; Lebrilla, C.B.; German, J.B. In vitro fermentation of breast milk oligosaccharides by bifidobacterium infantis and Lactobacillus gasseri. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 4497–4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Underwood, M.A.; German, J.B.; Lebrilla, C.B.; Mills, D.A. Bifidobacterium longum subspecies infantis: Champion colonizer of the infant gut. Pediatr. Res. 2014, 77, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.; Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.E.; Kunz, R.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Schünemann, H.J. GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008, 336, 924–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, H.; Mokhtar, G.; Imam, S.S.; Gad, G.I.; Hafez, H.; Aboushady, N. Comparison between killed and living probiotic usage versus placebo for the prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis and sepsis in neonates. Pakistan J. Biol. Sci. 2010, 13, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoni, P.; Rinaldi, M.; Cattani, S.; Pugni, L.; Romeo, M.G.; Messner, H. Bovine Lactoferin Supplementation for Prevention of Late-Onset Sepsis in Very Low-Birth-Weight Neonates. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2009, 302, 1421–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, B. Preventive effect of Bifidobacterium tetravaccine tablets in premature infants with necrotizing enterocolitis. J. Pediatr. Pharm. 2010, 16, 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hosni, M.; Duenas, M.; Hawk, M.; Stewart, L.A.; Borghese, R.A.; Cahoon, M.; Atwood, L.; Howard, D.; Ferrelli, K.; Soll, R. Probiotics-supplemented feeding in extremely low-birth-weight infants. J. Perinatol. 2012, 32, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bin-Nun, A.; Bromiker, R.; Wilschanski, M.; Kaplan, M.; Rudensky, B.; Caplan, M.; Hammerman, C. Oral probiotics prevent necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight neonates. J. Pediatr. 2005, 147, 192–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braga, T.D.; da Silva, G.A.; de Lira, P.I.; de Carvalho Lima, M. Efficacy of bifidobacterium breve and Lactobacillus casei oral supplementation on necrotizing enterocolitis in very-low-birth-weight preterm infants: A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrzanowska-Liszewska, D.; Seliga-Siwecka, J.; Kornacka, M.K. The effect of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG supplemented enteral feeding on the microbiotic flora of preterm infants-double blinded randomized control trial. Early Hum. Dev. 2012, 88, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costalos, C.; Skouteri, V.; Gounaris, A.; Sevastiadou, S.; Triandafilidou, A.; Ekonomidou, C.; Kontaxaki, F.; Petrochilou, V. Enteral feeding of premature infants with Saccharomyces boulardii. Early Hum. Dev. 2003, 74, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costeloe, K.; Hardy, P.; Juszczak, E.; Wilks, M.; Millar, M.R. Bifidobacterium breve BBG-001 in very preterm infants: A randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2016, 387, 649–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dani, C.; Biadaioli, R.; Bertini, G.; Martelli, E.; Rubaltelli, F.F. Probiotics feeding in prevention of urinary tract and necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants. Biol. Neonate 2002, 82, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demirel, G.; Erdeve, O.; Celik, I.H.; Dilmen, U. Saccharomyces boulardii for prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants: A randomized, controlled study. Acta Paediatr. 2013, 102, 560–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dilli, D.; Aydin, B.; Fettah, N.D.; Özyazıcı, E.; Beken, S.; Zenciroğlu, A.; Okumuş, N.; Özyurt, B.M.; İpek, M.Ş.; Akdağ, A.; et al. The propre-save study: Effects of probiotics and prebiotics alone or combined on necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. J. Pediatr. 2015, 166, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, S.; Ray, P.; Narang, A. Comparison of stool colonization in premature infants by three dose regimes of a probiotic combination: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Perinatol. 2015, 32, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Carrocera, L.A.; Solis-Herrera, A.; Cabanillas-Ayón, M.; Gallardo-Sarmiento, R.B.; García-Pérez, C.S.; Montaño-Rodríguez, R.; Echániz-Aviles, M.O.L.; Fernandez-Carrocera, L.A.; Cabanillas-Ayon, M.; Gallardo-Sarmiento, R.B.; et al. double-blind, randomised clinical assay to evaluate the efficacy of probiotics in preterm newborns weighing less than 1500 g in the prevention of necrotising enterocolitis. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2013, 98, F5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hays, S.; Jacquot, A.; Gauthier, H.; Kempf, C.; Beissel, A.; Pidoux, O.; Jumas-Bilak, E.; Decullier, E.; Lachambre, E.; Beck, L.; et al. Probiotics and growth in preterm infants: A randomized controlled trial, PREMAPRO study. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 35, 802–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hikaru, U.; Koichi, S.; Yayoi, S.; Hiromichi, S.; Hiroaki, S.; Yoshikazu, O.; Seigo, S.; Nagata, S.; Toshiaki, S.; Yamashiro, Y. Bifidobacteria prevents preterm infants from developing infection and sepsis. Int. J. Probiotics Prebiotics 2010, 5, 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, A.S.E.; Tobin, J.M. Probiotic effects on late-onset sepsis in very preterm infants: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics 2013, 132, 1055–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanic, Z.; Micetic Turk, D.; Burja, S.; Kanic, V.; Dinevski, D. Influence of a combination of probiotics on bacterial infections in very low birthweight newborns. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2015, 127, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitajima, H.; Sumida, Y.; Tanaka, R.; Yuki, N.; Takayama, H.; Fujimura, M. Early administration of Bifidobacterium breve to preterm infants: Randomised controlled trial. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1997, 76, F101–F107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.-C.; Su, B.-H.; Chen, A.-C.; Lin, T.-W.; Tsai, C.-H.; Yeh, T.-F.; Oh, W. Oral probiotics reduce the incidence and severity of necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics 2005, 115, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.-C.; Hsu, C.-H.; Chen, H.-L.; Chung, M.-Y.; Hsu, J.-F.; Lien, R.-I.; Tsao, L.-Y.; Chen, C.-H.; Su, B.-H. Oral probiotics prevent necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight preterm infants: A multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics 2008, 122, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzoni, P.; Mostert, M.; Leonessa, M.L.; Priolo, C.; Farina, D.; Monetti, C.; Latino, M.A.; Gomirato, G. Oral supplementation with Lactobacillus casei subspecies rhamnosus prevents enteric colonization by Candida species in preterm neonates: A randomized study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 42, 1735–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihatsch, W.A.; Vossbeck, S.; Eikmanns, B.; Hoegel, J.; Pohlandt, F. Effect of bifidobacterium lactis on the incidence of nosocomial infections in very-low-birth-weight infants: A randomized controlled trial. Neonatology 2010, 98, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millar, M.R.R.; Bacon, C.; Smith, S.L.L.; Walker, V.; Hall, M.A.A. Enteral feeding of premature infants with Lactobacillus GG. Arch. Dis. Child. 1993, 69, 483–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oncel, M.Y.; Sari, F.N.; Arayici, S.; Guzoglu, N.; Erdeve, O.; Uras, N.; Oguz, S.S.; Dilmen, U. Lactobacillus Reuteri for the prevention of necrotising enterocolitis in very low birthweight infants: A randomised controlled trial. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2014, 99, F110–F115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pärtty, A.; Luoto, R.; Kalliomäki, M.; Salminen, S.; Isolauri, E. Effects of early prebiotic and probiotic supplementation on development of gut microbiota and fussing and crying in preterm infants: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J. Pediatr. 2013, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patole, S.; Keil, A.D.; Chang, A.; Nathan, E.; Doherty, D.; Simmer, K.; Esvaran, M.; Conway, P. Effect of Bifidobacterium breve M-16V supplementation on fecal bifidobacteria in preterm neonates-a randomised double blind placebo controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas, M.A.; Lozano, J.M.; Rojas, M.X.; Rodriguez, V.A.; Rondon, M.A.; Bastidas, J.A.; Perez, L.A.; Rojas, C.; Ovalle, O.; Garcia-Harker, J.E.; et al. Prophylactic probiotics to prevent death and nosocomial infection in preterm infants. Pediatrics 2012, 130, e1113–e1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romeo, M.G.; Romeo, D.M.; Trovato, L.; Oliveri, S.; Palermo, F.; Cota, F.; Betta, P. Role of probiotics in the prevention of the enteric colonization by Candida in preterm newborns: Incidence of late-onset sepsis and neurological outcome. J. Perinatol. 2011, 31, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rougé, C.; Piloquet, H.; Butel, M.-J.; Berger, B.; Rochat, F.; Ferraris, L.; Des Robert, C.; Legrand, A.; de la Cochetiere, M.-F.; N’Guyen, J.-M.; et al. Oral supplementation with probiotics in very-low-birth-weight preterm infants: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 1828–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, A.; Chaudhuri, J.; Sarkar, D.; Ghosh, P.; Swapna, C. Role of enteric supplementation of probiotic on late-onset sepsisi by candida species in preterm low-boirth weight neonates: A randomized double blind, placebo-controlled trial. N. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2014, 6, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saengtawesin, V.; Tangpolkaiwalsak, R.; Kanjanapattankul, W. Effect of oral probiotics supplementation in the prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis among very low birth weight preterm infants. J. Med. Assoc. Thail. 2014, 97, S20–S25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Samanta, M.; Sarkar, M.; Ghosh, P.; Ghosh, J.; Sinha, M.; Chatterjee, S. Prophylactic probiotics for prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight newborns. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2008, 55, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sari, F.N.; Dizdar, E.A.; Oguz, S.; Erdeve, O.; Uras, N.; Dilmen, U. Oral probiotics: Lactobacillus sporogenes for prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in very low-birth weight infants: A randomized, controlled trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 65, 434–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serce, O.; Benzer, D.; Gursoy, T.; Karatekin, G.; Ovali, F. Efficacy of saccharomyces boulardii on necrotizing enterocolitis or sepsis in very low birth weight infants: A randomised controlled trial. Early Hum. Dev. 2013, 89, 1033–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, A.; Gupta, S.S.; Chellani, H.; Maliye, C.; Kumari, V.; Arya, S.; Garg, B.S.; Gaur, S.D.; Gaind, R.; Deotale, V.; et al. Role of probiotics VSL#3 in prevention of suspected sepsis in low birthweight infants in India: A randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e006564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stratiki, Z.; Costalos, C.; Sevastiadou, S.; Kastanidou, O.; Skouroliakou, M.; Giakoumatou, A.; Petrohilou, V. The effect of a bifidobacter supplemented bovine milk on intestinal permeability of preterm infants. Early Hum. Dev. 2007, 83, 575–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tewari, V.V.; Dubey, S.K.; Gupta, G. Bacillus clausii for prevention of late-onset sepsis in preterm infants: A randomized controlled trial. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2015, 61, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Totsu, S.; Yamasaki, C.; Terahara, M.; Uchiyama, A.; Kusuda, S. Bifidobacterium and enteral feeding in preterm infants: Cluster-randomized trial. Pediatr. Int. 2014, 56, 714–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fu, J.; Sun, M.; Mao, Z.; Vandenplas, Y. A double-blinded randomized trial on growth and feeding tolerance with Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 in formula-fed preterm infants. J. Pediatr. (Rio. J.) 2016, 92, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drago, L.; de Vecchi, E. Should Lactobacillus sporogenes and Bacillus coagulans have a future? J. Chemother. 2009, 21, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maffei, D.; Schanler, R.J. Human milk is the feeding strategy to prevent necrotizing enterocolitis! Semin. Perinatol. 2017, 41, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schanler, R.J.; Shulman, R.J.; Lau, C. Feeding strategies for premature infants: Beneficial outcomes of feeding fortified human milk versus preterm formula. Pediatrics 1999, 103, 1150–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corvaglia, L.; Fantini, M.P.; Aceti, A.; Gibertoni, D.; Rucci, P.; Baronciani, D.; Faldella, G. Predictors of full enteral feeding achievement in very low birth weight infants. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e92235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Embleton, N.D.; Zalewski, S.; Berrington, J.E. Probiotics for prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis and sepsis in preterm infants. Curr. Opin. Infect Dis. 2016, 29, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eidelman, A.I. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk: An analysis of the American Academy of Pediatrics 2012 Breastfeeding Policy Statement. Breastfeed. Med. 2012, 129, e827–e841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Underwood, M.A. Human milk for premature infant. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 60, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peila, C.; Moro, G.; Bertino, E.; Cavallarin, L.; Giribaldi, M.; Giuliani, F.; Cresi, F.; Coscia, A. The effect of holder pasteurization on nutrients and biologically-active components in donor human milk: A review. Nutrients 2016, 8, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, D.; Zhou, W.; Lun, Z.J.; Mu, X.; Wang, D.X.; Wu, H. Meta-analysis of probiotics and/or prebiotics for the prevention of eczema. J. Int. Med. Res. 2013, 41, 1426–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertelli, C.; Pillonel, T.; Torregrossa, A.; Prod’hom, G.; Fischer, C.J.; Greub, G.; Giannoni, E. Bifidobacterium longum bacteremia in preterm infants receiving probiotics. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 60, 924–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).