Abstract

Background: The heart depends on a continuous and flexible energy supply from fatty acids, glucose, and other substrates. Emerging evidence shows that gut microbiota-derived metabolites—such as trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), secondary bile acids, indoles, phenylacetylglutamine (PAGln), and branched-chain amino acids—modulate cardiac metabolism and function. Although clinical evidence linking these metabolites to cardiovascular outcomes is expanding, most data remain associative, with limited causal or interventional proof. Methods: A comprehensive narrative review was conducted (PubMed 2010–2025) to integrate preclinical, clinical, and Mendelian randomization studies on microbiota-derived metabolites and cardiovascular disease, complemented by evidence from dietary and interventional trials. Results: Gut-derived metabolites regulate mitochondrial energetics, inflammatory, immune system, and oxidative pathways, and endothelial and platelet activation. Elevated plasma TMAO and PAGln levels are often associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes, while SCFAs and indole derivatives may related to protective effects. However, findings across cohorts remain heterogeneous, largely due to differences in diet, renal function, and analytical methods. Dietary patterns rich in fiber and plant-based nutrients favor beneficial metabolite profiles, underscoring the nutritional modulation of the gut–heart axis. Conclusions: The diet–microbiota–metabolite axis represents an emerging pathway connecting nutrition to cardiovascular health. Translating this knowledge into prevention and therapy will require large-scale randomized studies and integrated multi-omics approaches. Dietary modulation of microbial metabolism may ultimately become a novel strategy for cardiometabolic protection.

1. Introduction

The heart is a metabolically flexible organ, capable of adapting to different energy substrates—fatty acids, glucose, lactate, ketone bodies, and amino acids—to sustain continuous contraction and function. This metabolic flexibility is crucial for maintaining cardiac homeostasis under both physiological and pathological conditions [1]. In recent years, an additional player has emerged in this complex scenario: the gut microbiota, now regarded as a “metabolic organ” capable of transforming dietary nutrients into a wide range of bioactive metabolites with systemic effects [2,3].

The concept of a gut–heart axis has gained ground through studies linking an imbalance in microbial composition (dysbiosis) and gut-derived metabolites to the progression of cardiovascular diseases, including atherosclerosis, hypertension, arrhythmias, and, particularly, heart failure [4,5]. Within this context, several classes of nutrient-derived microbial metabolites have been identified as key mediators. The most studied nutrient-derived microbial metabolites include: (i) Trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), derived from choline, carnitine, and lecithin, associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes in numerous observational studies [6]; (ii) short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), generated from dietary fiber fermentation, with anti-inflammatory and cardio-energetic effects [7]; (iii) secondary bile acids, acting through nuclear and membrane receptors (FXR and TGR5) and influencing lipid metabolism and contractility [8]; (iv) indoles, derived from tryptophan, associated with heterogeneous cardiovascular effects [9]; (v) phenylacetylglutamine (PAGln), linked to increased platelet reactivity and thrombotic risk [10]; and (vi) branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), whose altered catabolism has been associated with cardiac remodeling and heart failure, particularly with the heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) phenotype [11].

Despite the growing body of evidence, the field still faces significant limitations and controversies. Much of the literature focuses primarily on TMAO, whereas other metabolites remain underexplored or discussed in a fragmented way. Moreover, many available data derive from observational studies reporting simple associations, without clarifying whether these metabolites are true causal mediators or merely risk biomarkers. Findings are sometimes inconsistent: for instance, while several studies link elevated TMAO levels with cardiovascular mortality and heart failure progression, others fail to confirm an independent association after adjustment for renal function and comorbidities [12,13].

Another relevant gap is the limited integration between molecular mechanisms and clinical data. On the one hand, preclinical models have identified specific signaling pathways of nutrient-derived microbial metabolites—such as activation of G-protein coupled receptor 41/43 (GPR41/43), Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR), β-2 adrenergic receptor (β-2AR), oxidative stress, and inflammation—while, on the other hand, translating these findings into clinical contexts remains incomplete [14,15]. Similarly, approaches such as Mendelian randomization and multi-omics analyses, which could provide clues about causality, have yielded heterogeneous and poorly systematized results in current reviews [16].

From a translational perspective, therapeutic opportunities are promising but still immature. Dietary interventions, such as the Mediterranean diet or increased fiber intake, are associated with more favorable metabolic profiles [17]. In contrast, probiotics and prebiotics have shown encouraging but preliminary results in small trials [18]. In parallel, novel pharmacological strategies aim to inhibit key microbial enzymes (e.g., CutC/D in TMA production) or modulate specific receptors for SCFA, bile acids, and indoles [19]. However, large-scale randomized trials with robust clinical endpoints are still lacking to consolidate these options into clinical practice.

In light of these considerations, this review is guided by the working hypothesis that diet–microbiota interactions shape metabolite profiles that may influence cardiac metabolism and function. It aims to provide an integrated overview of nutrient-derived microbial metabolites that influence cardiac metabolism and function, combining mechanistic, clinical, and evidence-based data to identify converging mechanisms and persistent uncertainties, and to highlight future directions for translating microbiota-derived metabolic pathways into cardiovascular prevention and therapy.

2. Materials and Methods

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in PubMed/MEDLINE from January 2010 to March 2025. Only articles published in English were considered. Given the interdisciplinary nature of this topic and the evolving evidence on the gut–microbiota–heart axis, we adopted a narrative and integrative approach rather than a formal systematic review and therefore considered multiple study designs. We included peer-reviewed articles published in English that investigated (i) dietary nutrients and/or microbiota-targeted interventions (e.g., probiotics and prebiotics), (ii) gut microbiota-derived metabolites (e.g., TMAO, PAGln, secondary bile acids, SCFAs, indole-related metabolites, and amino acids), and (iii) cardiovascular phenotypes/mechanisms (e.g., atherosclerosis, thrombosis, endothelial dysfunction, and heart failure). Eligible study designs included experimental (in vitro/in vivo), observational studies, and clinical trials, as well as high-quality systematic reviews relevant to mechanistic interpretation. We excluded conference abstracts, editorials/letters without original data, case reports, non-English papers, and studies that did not address the gut microbiota–metabolite axis in relation to cardiovascular outcomes.

The primary search combined keywords related to microbiota, nutrient-derived metabolites, and cardiac function using Boolean operators (AND/OR). The search strategy included the following terms: gut microbiota, intestinal microbiota, microbiome, nutrient-derived metabolites, trimethylamine N-oxide, TMAO, short-chain fatty acids, SCFA, bile acids, indoles, tryptophan metabolism, phenylacetylglutamine, PAGln, branched-chain amino acids, BCAA, cardiac metabolism, heart failure, HFpEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), atherosclerosis, cardiovascular disease, diet, nutrition, metabolomics, metabolic pathways, and nutritional interventions.

Two independent reviewers performed the search to enhance completeness and accuracy. In addition, reference lists of selected articles and relevant reviews were manually screened to identify additional eligible publications. No formal quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis) was planned, as the included studies were heterogeneous in design and analytical methods. The review, therefore, emphasizes convergence across mechanistic, translational, and clinical evidence.

3. Overview of Nutrient-Derived Microbial Metabolites

A variety of gut microbiota-dependent metabolites derived from dietary substrates have been implicated in cardiovascular physiology and disease. These metabolites act through distinct molecular pathways, influencing inflammation, thrombosis, myocardial energetics, and remodeling (Table 1).

Table 1.

Major nutrient-derived microbial metabolites and their cardiovascular relevance.

3.1. Trimethylamine/Trimethylamine-N-Oxide (TMA/TMAO)

TMAO is a gut microbiota-derived metabolite originating from trimethylamine (TMA), which in turn is produced from dietary nutrients rich in trimethylamine moieties such as choline, phosphatidylcholine, and carnitine, commonly found in red meat, eggs, and fish [20]. Once absorbed, TMA is transported to the liver, where flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 (FMO3) oxidizes it into TMAO [21]. TMAO has been shown to interfere with reverse cholesterol transport, promoting cholesterol deposition in the arterial wall and accelerating atherosclerosis [22]. Mechanistically, elevated circulating TMAO levels contribute to endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, inflammatory activation, and platelet hyperreactivity, thereby promoting vascular injury and atherothrombosis [23,24]. Experimental studies have demonstrated that animal models supplemented with TMAO, choline, or carnitine show increased foam cell formation from macrophages and accelerated atherosclerotic plaque development [21]. Furthermore, in diabetic or metabolically impaired mice, circulating TMAO levels are elevated, whereas reducing TMAO production by knocking down the enzyme FMO3 improves insulin tolerance and reduces cardiovascular issues such as atherosclerosis [25].

3.2. Phenylacetylglutamine (PAGln)

PAGln is a gut microbiota-dependent metabolite generated from the microbial metabolism of dietary phenylalanine, followed by host conjugation with glutamine [26]. The gut microbiome is essential for its production, as antibiotic treatment in both mice and humans leads to a transient decline in circulating PAGln levels, confirming its microbial origin [26,27].

PAGln may also modestly influence thrombotic risk by engaging platelet adrenergic receptors and facilitating Ca2+-dependent activation, an effect shown to be reversible with carvedilol, suggesting a role for adrenergic signaling in its platelet-related actions [28].

3.3. Secondary Bile Acids

Secondary bile acids (BAs) are synthesized in the liver from cholesterol to form primary bile acids, which are secreted into the small intestine to facilitate the absorption and digestion of lipids and fat-soluble vitamins [29]. Within the intestinal lumen, the gut microbiota plays a crucial role in the biotransformation of bile acids [30,31]. This microbial conversion substantially alters the composition and pool size of circulating bile acids, influencing their signaling potential and enterohepatic circulation [30]. Before re-entering the liver via the enterohepatic recirculation, bile acids may undergo additional microbial modifications that affect their receptor affinity and systemic effects [30]. Beyond their digestive functions, bile acids are key signaling molecules that interact with a broad spectrum of receptors, including nuclear receptors such as the farnesoid X receptor (FXR), pregnane X receptor (PXR), and vitamin D receptor (VDR), as well as membrane receptors like the Takeda G-protein-coupled bile acid receptor 1 (TGR5/GP-BAR1) and muscarinic receptors [30,32,33,34,35,36]. FXR and TGR5 are expressed in endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, and cardiomyocytes, where they influence cholesterol and glucose metabolism, vascular tone, and inflammatory responses [37,38,39,40]. At physiological levels, bile acid-mediated activation of FXR and TGR5 tends to be vasculoprotective, promoting NO-dependent vasodilation, improving endothelial function, and exerting anti-inflammatory and lipid-lowering effects through mechanisms that include NO synthesis, Ca2+-dependent K+ channel activation, and muscarinic receptor stimulation [40,41,42,43,44]. In contrast, excess secondary bile acids such as deoxycholic acid can cause oxidative injury, mitochondrial dysfunction, endothelial damage, and reduced cardiomyocyte contractility, highlighting their dose-dependent, dual nature [45,46]. Overall, despite the complexity arising from their chemical heterogeneity and receptor promiscuity, current evidence supports bile acids as key modulators of vascular tone, metabolic homeostasis, and inflammation at the intersection of hepatic metabolism, gut microbiota activity, and cardiovascular function [47].

3.4. Amino Acids

Both host and microbial enzymes metabolize dietary branched-chain amino acids (leucine, isoleucine, and valine—BCAA). Impaired BCAA catabolism has been implicated in metabolic remodeling of the failing heart, particularly in HFpEF [48]. The accumulation of BCAAs and their toxic intermediates activates mTOR signaling, contributing to myocardial hypertrophy, fibrosis, and impaired energetics [49].

3.5. Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFA)

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)—primarily acetate, propionate, and butyrate—are produced in the colon through anaerobic fermentation of indigestible dietary fibers such as resistant starch, pectin, inulin, and other complex carbohydrates [50,51]. After absorption, propionate and acetate undergo hepatic metabolism and enter systemic circulation, where they modulate cardiovascular function [52]. SCFAs exert systemic effects via activation of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPR41/FFAR3 and GPR43/FFAR2) expressed on endothelial and immune cells and adipose tissues, and through inhibition of histone deacetylases (HDACs), thereby influencing chromatin remodeling and gene expression [53,54]. Through these mechanisms, they enhance gut barrier integrity, regulate lipid and glucose homeostasis, and reduce systemic inflammation [53,55,56,57]. Experimental evidence indicates that SCFAs ameliorate endothelial dysfunction, lower blood pressure, and attenuate cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis [58,59,60,61]. Notably, butyrate has been shown to increase HDL levels and reduce LDL concentrations, supporting cardiovascular protection through improved lipid metabolism and reduced oxidative stress [62,63].

3.6. Indoles

Indole derivatives, such as indole-3-propionic acid (IPA), are produced from dietary tryptophan by specific gut bacteria. IPA has been shown to exert antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, partly by activating the AhR and modulating NAD metabolism [64].

4. Mechanistic Pathways Linking Nutrient-Derived Metabolites to Cardiac Function

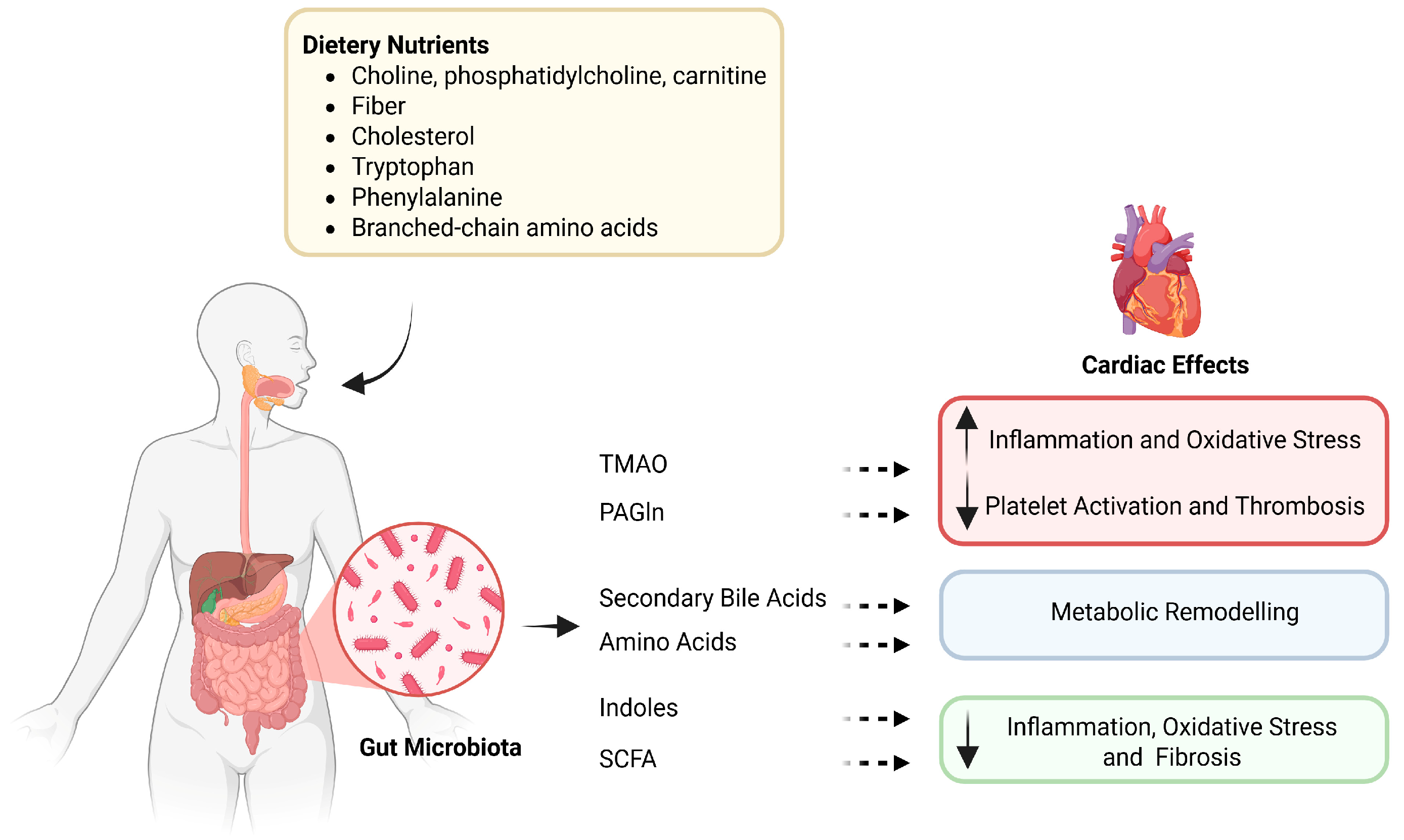

Gut-derived metabolites influence cardiac physiology through a range of molecular and cellular mechanisms (Figure 1). These include modulation of myocardial energetics, inflammatory and oxidative stress signaling, endothelial and platelet function, and structural remodeling.

Figure 1.

The gut–heart axis: microbial metabolites linking diet to cardiovascular effects. Dietary precursors such as choline, bile acids, and amino acids are metabolized by gut microbes into bioactive compounds, including TMAO, PAGln, SCFAs, and indoles. These metabolites exert diverse effects on the cardiovascular system, modulating inflammation, oxidative stress, thrombosis, and metabolic remodeling. TMAO—Trimethylamine N-oxide; PAGln—Phenylacetylglutamine; SCFAs—Short-chain fatty acids. Dietary nutrients and microbiota-targeted interventions (probiotics, prebiotics, and microbiota-directed drugs) shape gut microbiota composition and the production of specific metabolites, including trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), phenylacetylglutamine (PAGln), bile acids, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), amino acids, and indole derivatives. These metabolites are differentially associated with cardiovascular diseases: TMAO, PAGln, bile acids, and amino acids are linked to atherosclerosis, heart failure, and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), whereas SCFAs and some indole derivatives are often associated with protective phenotypes; however, these effects are context-dependent and may vary by metabolite species and host conditions. This schematic summarizes reported associations and proposed mechanisms; arrows do not imply established causality in humans.

4.1. Inflammation and Immune Signaling

Low-grade chronic inflammation is a central mechanism linking gut-derived metabolites to cardiovascular disease. Among these, TMAO has been associated with pro-inflammatory signaling, and experimental studies suggest it may amplify immune and vascular responses. Elevated plasma TMAO levels have been associated with enhanced NF-κB signaling activation, increased interleukin production (IL-1β and IL-6), and upregulation of adhesion molecules such as Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1 (ICAM-1) in endothelial cells. It has also been observed that TMAO primes the NLRP3 inflammasome, thereby contributing to endothelial injury and immune cell infiltration [22,65]. At the same time, TMAO has been reported to promote reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation by stimulating Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate (NADPH) oxidase activity and by reducing mitochondrial antioxidant defenses, including Sirtuin 1/3 (SIRT1/3), and superoxide dismutase (SOD2). This imbalance is correlated with reduced NO bioavailability and endothelial dysfunction [22,66,67]. Conversely, SCFAs and indole derivatives exhibit anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties [68]. Butyrate and propionate have been shown to inhibit HDACs, restore the Treg/Th17 balance, and suppress NF-κB-dependent cytokine expression, while also upregulating antioxidant enzymes such as catalase and glutathione peroxidase [69].

Similarly, IPA has been associated with reduced oxidative stress and improved endothelial integrity by activating the AhR [70,71].

Under dysbiotic conditions, however, tryptophan metabolism shifts toward the production of kynurenine and indoxyl sulfate. These metabolites have been reported to induce oxidative stress and endothelial apoptosis via AhR–p38 MAPK activation, thereby compromising vascular integrity [72,73].

Activation of FXR (and, in some contexts, TGR5) by specific bile acid species has been associated with anti-inflammatory signaling in experimental models [74]. However, bile acid effects are receptor-, species-, and concentration-dependent, and excessive secondary bile acid accumulation has been linked to oxidative injury and endothelial dysfunction [75]. Collectively, these findings underscore the context-dependent, pro- versus anti-inflammatory actions of bile acids in the cardiovascular system [76].

4.2. Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress is a major contributor to cardiovascular pathology within the gut–heart axis. TMAO has been reported to increase ROS formation by stimulating NADPH oxidase and suppressing mitochondrial antioxidant enzymes such as SOD2 through inhibition of sirtuins (SIRT1 and SIRT3) [22,66,67]. These changes may contribute to mitochondrial dysfunction, endothelial activation, and diminished NO bioavailability, thereby accelerating vascular injury.

Conversely, SCFAs and indole derivatives exhibit robust antioxidant activity [76]. Butyrate enhances the expression of antioxidant enzymes such as catalase and glutathione peroxidase [77], while IPA functions as a potent free radical scavenger, protecting cardiomyocytes from lipid peroxidation [71,78]. In addition, bile acid signaling via FXR and TGR5 modulates redox balance. Actually, FXR activation attenuates ET-1-mediated vasoconstriction via AMPK signaling [79], whereas TGR5 activation enhances cAMP-mediated antioxidant responses [39].

In preclinical models, chronic TMAO exposure exacerbates oxidative stress and accelerates atherosclerosis [22]. FXR activation by secondary bile acids is linked to reduced oxidative stress, in part through their lipid-lowering and anti-inflammatory actions, which improve endothelial function [79,80]. In contrast, high concentrations of secondary bile acids, such as deoxycholic acid, can trigger oxidative injury and mitochondrial dysfunction, thereby promoting vascular damage [39,81]. These observations highlight that bile acids may either limit or exacerbate oxidative stress depending on receptor engagement, molecular species, and concentration [82].

4.3. Endothelial and Platelet Function

The endothelium serves as a dynamic interface between the circulation and the tissue, regulating vascular tone, permeability, and hemostasis. Gut-derived metabolites influence endothelial and platelet function in both protective and pathological directions. TMAO and PAGln have been shown in experimental settings to increase platelet responsiveness by activating adrenergic receptors (α2A, α2B, β1, and β2), suggesting an increased intracellular calcium flux and thrombus formation [83]. This pro-thrombotic state is reinforced by oxidative stress, which promotes leukocyte adhesion and endothelial activation [83,84].

TMAO suppresses sirtuin activity and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) function, leading to reduce NO bioavailability and impaired vasodilation [85]. PAGln-mediated adrenergic signaling further enhances NF-κB-dependent inflammatory gene expression, upregulating VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 [86]. Mechanistically, PAGln has been shown to modulate platelet function and thrombosis risk. It activates the adrenergic receptors α2A, α2B, and β2 expressed on human platelets, thereby enhancing intracellular Ca2+ signaling and lowering the activation threshold for classical platelet agonists such as ADP [28]. This receptor-mediated mechanism can promote platelet hyperresponsiveness and collagen adhesion under flow conditions, thereby increasing thrombotic potential [28]. In experimental models, carotid arterial thrombosis induced by PAGln was reversed by carvedilol, a non-selective adrenergic receptor antagonist, demonstrating that the pro-thrombotic effects of PAGln are mediated via adrenergic signaling [28]. These processes may create a sustained inflammatory and thrombogenic milieu conducive to atherosclerotic plaque progression.

By contrast, SCFAs strengthen endothelial integrity and enhance eNOS-mediated NO production [58]. Butyrate promotes vasodilation and barrier function, while propionate modulates sympathetic activity via GPR41, thereby reducing vascular tone and blood pressure [69,87]. Bile acids also contribute to vascular homeostasis, acting on FXR and TGR5. In particular, within the vasculature, both receptors contribute to the regulation of vascular tone and endothelial homeostasis [88]. TGR5 activation promotes vasodilation via NO signaling, whereas FXR stimulation improves endothelial function and reduces inflammation [89,90]. The vasodilatory effects of bile acids are mediated by multiple mechanisms, including enhanced NO synthesis, activation of Ca2+-dependent K+ channels, and stimulation of muscarinic receptors [90,91,92]. At supraphysiological concentrations, however, bile acids can impair endothelial integrity and alter vascular relaxation, again emphasizing their dose-dependent dual nature [8].

4.4. Myocardial Energetics

The myocardium is one of the most metabolically active tissues in the body, requiring a continuous supply of ATP to sustain contraction and relaxation. Under physiological conditions, fatty acid oxidation provides approximately 60–70% of cardiac ATP production, with glucose and lactate serving as complementary energy substrates. However, during metabolic stress, SCFAs may contribute as alternative substrates that can enhance mitochondrial efficiency and preserve cardiac energetics [63]. SCFAs—principally acetate, propionate, and butyrate—exert effects through the activation of GPR41 and GPR43 and inhibition of histone deacetylases (HDACs) [77,93]. Butyrate promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation by activating Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Coactivator (PGC)-1α and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), thereby improving mitochondrial efficiency and energy conservation [94]. Propionate sustains anaplerotic flux into the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, preserving ATP synthesis under hypoxic or nutrient-limited conditions. Conversely, impaired metabolism of BCAAs (leucine, isoleucine, and valine) leads to accumulation of branched-chain ketoacids (BCKAs), which interfere with mitochondrial oxidative capacity and activate mechanistic Target Of Rapamycin Complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling. This maladaptive activation promotes protein synthesis, cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, and diastolic dysfunction, key features of heart failure with HFpEF [95,96]. In addition, bile acids influence cardiomyocyte function, in part by affecting mitochondrial integrity. Excessive accumulation of secondary bile acids, such as deoxycholic acid, can induce mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative injury, and endothelial damage, thereby contributing to vascular and myocardial pathology [97]. At higher concentrations, bile acids have also been reported to reduce cardiomyocyte contractility in a dose-dependent manner, indicating a potential detrimental impact on myocardial performance when levels exceed the physiological range [98].

Thus, cardiac energy metabolism is a critical node through which nutrient-derived metabolites influence myocardial performance and metabolic flexibility.

4.5. Cardiac Remodeling and Fibrosis

Cardiac remodeling represents the culmination of metabolic, inflammatory, and oxidative stress-related insults driven by gut-derived metabolites. TMAO promotes fibroblast activation and collagen synthesis via TGF-β/Smad signaling, thereby contributing to interstitial fibrosis and impaired ventricular compliance [99]. Chronic TMAO exposure also exacerbates hypertrophy and stiffness, mimicking clinical features of HFpEF.

Likewise, excessive BCAA accumulation triggers mTORC1–S6K1–4EBP1 signaling, stimulating protein synthesis and hypertrophic remodeling [100]. Impaired BCAA catabolism in macrophages contributes to increased pro-inflammatory cytokine release, establishing a vicious cycle between metabolic stress and inflammation.

Conversely, SCFAs and indole derivatives counteract fibrosis by inhibiting TGF-β-driven myofibroblast differentiation and extracellular matrix deposition [63]. Bile acid receptors FXR and TGR5 regulate matrix turnover by suppressing fibrotic gene expression and improving mitochondrial quality control [101]. Restoring the balance of these metabolites can therefore mitigate pathological remodeling and preserve myocardial architecture.

4.6. Electrophysiological Effects

Emerging data indicate that gut-derived metabolites also modulate cardiac electrophysiology. Secondary bile acids affect ion channel function—particularly calcium and potassium channels—through FXR/TGR5-dependent mechanisms, altering action potential duration and predisposing to arrhythmias [101]. PAGln-driven adrenergic stimulation further enhances calcium influx and delays repolarization, heightening arrhythmogenic potential [102]. Moreover, accumulation of BCAAs and kynurenine pathway metabolites disrupts mitochondrial potential and elevates ROS production in cardiomyocytes, contributing to electrical instability and arrhythmogenesis [72,96]. These findings highlight the intricate interplay between metabolic and electrophysiological signaling in the gut–heart axis.

5. Clinical Evidence

Clinical research investigating gut-derived, nutrient-dependent metabolites in cardiovascular disease has expanded rapidly in recent years. Nevertheless, methodological limitations and confounding factors still hinder causal interpretation and clinical translation. Current knowledge mainly derives from observational and case–control studies, while randomized interventional evidence remains limited.

5.1. Heart Failure (HFpEF vs. HFrEF): Differences in Metabolite Profiles

Altered gut microbiota composition and distinct metabolomic signatures have been reported in patients with heart failure, with consistent depletion of SCFA-producing taxa and enrichment of pathobionts such as Proteobacteria [103]. Circulating TMAO levels are frequently elevated in both HFpEF and HFrEF and have been associated with adverse prognosis [104], although adjustment for renal function often attenuates these associations [105,106]. While some Mendelian randomization (MR) studies suggest a modest causal contribution of TMAO to heart failure or coronary artery disease [107], others fail to confirm these findings after accounting for pleiotropy and population differences. Conversely, decreased SCFA concentrations and impaired BCAA catabolism have been reported primarily in HFpEF [100,108,109,110], supporting a link between metabolic remodeling and diastolic dysfunction. In addition, preclinical studies indicate that IPA protects against diastolic dysfunction in models of HFpEF and mitigates sepsis-induced cardiac dysfunction [9].

5.2. Atherosclerosis, Acute Myocardial Infarction, and Stroke: Prospective Associations (TMAO and PAGln)

Prospective cohort studies and meta-analyses have reported positive associations between higher plasma concentrations of TMAO or PAGln and the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), including myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular mortality [111,112,113]. Actually, in a large cohort of patients undergoing elective coronary angiography, plasma TMAO levels were independent predictors of stroke, myocardial infarction, revascularization, and death [114]. PAGln, in particular, demonstrates a mechanistic connection with platelet adrenergic signaling [27,28], supporting the biological plausibility of a link to thrombosis. However, the strength and consistency of these associations vary considerably across studies, largely due to differences in population size, analytical platforms, and the adjustment for dietary and metabolic confounders [115,116,117,118].

6. Emerging Biomarkers: Robust vs. Controversial

Among the diverse metabolites produced by the gut microbiota, several have been proposed as potential biomarkers of cardiovascular disease, though the strength and consistency of the supporting evidence vary widely. Because elevated plasma TMAO levels have been linked to increased risk of all-cause mortality and major cardiovascular events across multiple cohorts and meta-analyses [21,119,120], TMAO could be considered a risk-stratification tool in both primary and secondary prevention settings. A second emerging biomarker is PAGln, a phenylalanine-derived metabolite associated with heightened thrombotic risk. Elevated PAGln levels have been observed in patients with heart failure and have been linked to increased platelet reactivity and adverse clinical outcomes [10,28,121]. In contrast, other metabolites, such as SCFAs, present a more complex and context-dependent picture. Butyrate appears elevated in HFrEF but reduced in HFpEF, suggesting phenotype-specific metabolic adaptations [7]. These inconsistencies highlight the need for standardized measurement methods and better-controlled clinical studies.

Indole derivatives also show promise. Preclinical data suggest anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects, and early clinical observations report lower IPA levels in patients with HFpEF compared to healthy controls [9]. However, the available human evidence remains preliminary, and larger cohorts are required to confirm their diagnostic and prognostic utility. Similarly, BCAAs and their metabolic byproducts have been implicated in the pathophysiology of heart failure, particularly HFpEF. Impaired BCAA catabolism may contribute to myocardial metabolic dysfunction, and elevated circulating levels have been observed in both HFrEF and HFpEF [108,122]. Nonetheless, these findings are primarily associative, and it remains unclear whether BCAA alterations are causal or merely reflect systemic metabolic dysregulation. Finally, specific metabolites—despite extensive investigation—remain the subject of debate. This is particularly true for TMAO, whose causal role is still uncertain. While strong associations with cardiovascular outcomes have been repeatedly observed, Mendelian randomization and multi-omics studies have produced conflicting results, failing to confirm a direct pathogenic role in many cases [21,107,119,120,123]. These discrepancies raise the possibility that TMAO may serve more as a marker of dysbiosis or renal dysfunction than as an active disease mediator. In conclusion, while TMAO and PAGln currently stand out for their reproducibility and translational potential, other metabolites such as SCFAs, indoles, and BCAAs offer intriguing, albeit less established, avenues for biomarker discovery. Future research will need to integrate clinical cohorts, mechanistic insights, and interventional studies to clarify their roles and define their place in cardiovascular risk stratification and prevention.

7. Dietary Modulation and Interventional Perspectives

Dietary patterns are a primary determinant of gut microbial composition and the profile of microbial-derived metabolites. Mediterranean and plant-based dietary regimens—characterized by high intake of fiber, polyphenols, and omega-3 fatty acids—are associated with enhanced production of SCFAs and favorable modulation of bile acid signaling pathways. These effects contribute to improvements in lipid metabolism, endothelial function, and anti-inflammatory status [50,124,125,126,127]. High-fiber intake specifically augments colonic fermentation, resulting in increased systemic levels of acetate and butyrate, which, in turn, support mitochondrial biogenesis, oxidative phosphorylation, and the suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokine production [124,128,129].

Microbiota-targeted nutritional interventions, including probiotics and prebiotics, represent pragmatic adjunct strategies to modulate gut-derived metabolites implicated in CVD. Although available evidence suggests modest improvements in selected cardiometabolic risk markers (e.g., blood pressure, lipid and glycemic profiles, and inflammatory indices), results vary substantially depending on formulation, dose, and the population studied [130]. Mechanistically, these approaches may promote SCFA-producing taxa and reshape bile acid pools, potentially influencing downstream FXR/TGR5 signaling [131]. Conversely, interventions aimed at modulating the choline/carnitine-derived TMA/TMAO pathway have yielded mixed results; in some controlled trials, probiotic supplementation was not associated with consistent reductions in circulating TMAO levels under fasting conditions or following a dietary challenge [132,133]. Similarly, inulin supplementation did not reduce plasma TMAO concentrations in adults at cardiometabolic risk [134]. Beyond metabolite modulation, probiotic and prebiotic supplementation—particularly formulations containing Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains—has been associated with reduced systemic inflammatory markers and improved left ventricular function in preliminary clinical studies involving heart failure patients [135,136]; however, these findings are primarily derived from small-scale or pilot trials, and larger randomized controlled studies are required to confirm therapeutic efficacy and generalizability.

Dietary restriction of red meat and choline-rich foods (e.g., egg yolks and liver) has been proposed as a strategy to reduce circulating levels of TMA, a pro-atherothrombotic metabolite produced through gut microbial metabolism of dietary trimethylamine-containing compounds [20,137]. In parallel, pharmacological inhibition of microbial TMA production via targeting of CutC/D enzymes offers a novel therapeutic avenue, as evidenced by preclinical studies demonstrating reduced TMAO levels and attenuated atherosclerosis [138,139].

Collectively, available evidence suggests that nutritional modulation of gut-derived metabolites may represent a potential adjunct approach for cardiovascular prevention. However, most human data remain associative and interventional findings are heterogeneous; therefore, these strategies should be considered hypothesis-generating until confirmed in adequately powered randomized controlled trials with robust clinical endpoints. Targeting the diet–microbiota–metabolite axis may thus complement conventional cardiometabolic therapies by addressing upstream metabolic and inflammatory pathways.

8. Conclusions

The growing understanding of the diet–microbiota–heart axis reveals a complex network of interactions that shape cardiovascular health. Microbial metabolites such as TMAO and PAGln have shown reproducible associations with adverse cardiac outcomes and mechanistic links to inflammation, thrombosis, and remodeling. SCFAs, selected indole derivatives, and bile acid signaling have been associated with potentially beneficial effects on metabolic flexibility, endothelial function, and redox balance, although these relationships are context- and concentration-dependent. Nevertheless, the clinical relevance of many of these metabolites remains limited by methodological heterogeneity, confounding factors (e.g., renal function), and inconsistent evidence from Mendelian randomization or interventional trials.

Dietary patterns emerge as key upstream modulators of these microbial pathways. High-fiber and plant-based diets support beneficial microbial activity and metabolite production, while targeted interventions—such as probiotics, prebiotics, and enzyme inhibition—represent promising but still exploratory therapeutic strategies.

To translate this knowledge into clinical practice, future research must address current gaps through large-scale, longitudinal, and mechanistically informed studies. Integrating multi-omics profiling, microbial functional assays, and randomized interventions will be essential to move beyond correlation and toward causally grounded, personalized approaches for cardiovascular prevention and therapy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: L.S., M.G.B. and G.P.; Project administration: L.S.; Supervision: L.S.; Writing—original draft: M.B., A.P., R.A.F., N.B., A.M.M.P., R.J., A.Z., G.T., Z.U. and M.A.; Writing—review and editing: L.S., M.G.B. and G.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by PNRR Project ANTHEM (AdvaNced Technologies for Human-cEntred Medicine) Project Code PNC0000003, CUP: B53C22006540001; PRIN2022—CUP: B53D23020210006; Arketipo: ARtificial Intelligence for Early RisK PrEdicTIon of Heart Failure by Combining Circulating EPi Signature tO Clinical Features Project Code F/310107/01/X56, CUP: B29J23000310005; and RENALERT-AI CUP: B29J24000110005, Project Code: F/360062/03/X75.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AhR | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| BA | Bile acid |

| BCAA | Branched-chain amino acid |

| BCKA | Branched-chain keto acid |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| cAMP | Cyclic adenosine monophosphate |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| eNOS | Endothelial nitric oxide synthase |

| ET-1 | Endothelin-1 |

| FMO3 | Flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 |

| FXR | Farnesoid X receptor |

| GPR41 | G protein-coupled receptor 41 (free fatty acid receptor 3, FFAR3) |

| GPR43 | G protein-coupled receptor 43 (free fatty acid receptor 2, FFAR2) |

| HDAC | Histone deacetylase |

| HF | Heart failure |

| HFpEF | Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction |

| HFrEF | Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction |

| ICAM-1 | Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IPA | Indole-3-propionic acid |

| MACE | Major adverse cardiovascular events |

| MR | Mendelian randomization |

| mTOR | Mechanistic target of rapamycin |

| mTORC1 | Mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 |

| NAD | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| NLRP3 | NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3 |

| PAGln | Phenylacetylglutamine |

| PCI | Percutaneous coronary intervention |

| PGC-1α | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 alpha |

| PXR | Pregnane X receptor |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SCFA | Short-chain fatty acid |

| SIRT1 | Sirtuin 1 |

| SIRT3 | Sirtuin 3 |

| SOD2 | Superoxide dismutase 2 |

| TCA | Tricarboxylic acid cycle |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor beta |

| TGR5 | Takeda G protein-coupled receptor 5 (G protein-coupled bile acid receptor 1) |

| TMA | Trimethylamine |

| TMAO | Trimethylamine N-oxide |

| VCAM-1 | Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 |

| VDR | Vitamin D receptor |

References

- Da Dalt, L.; Cabodevilla, A.G.; Goldberg, I.J.; Norata, G.D. Cardiac lipid metabolism, mitochondrial function, and heart failure. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 119, 1905–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manolis, A.A.; Manolis, T.A.; Melita, H.; Manolis, A.S. Gut Microbiota and Cardiovascular Disease: Symbiosis Versus Dysbiosis. Curr. Med. Chem. 2022, 29, 4050–4077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariff, S.; Kwan Su Huey, A.; Parag Soni, N.; Yahia, A.; Hammoud, D.; Nazir, A.; Uwishema, O.; Wojtara, M. Unlocking the gut-heart axis: Exploring the role of gut microbiota in cardiovascular health and disease. Ann. Med. Surg. 2024, 86, 2752–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.H.W.; Li, D.Y.; Hazen, S.L. Dietary metabolism, the gut microbiome, and heart failure. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2019, 16, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masenga, S.K.; Povia, J.P.; Lwiindi, P.C.; Kirabo, A. Recent Advances in Microbiota-Associated Metabolites in Heart Failure. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; He, J.; Huo, Y.; Liu, L.; Xie, Y.; Meng, Y.; Wei, G.; Deng, L.; Jiang, Y.; Feng, J. Gut microbial metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide as a novel predictor for adverse cardiovascular events after PCI: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Nutr. J. 2025, 24, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm, C.L.; de Wit, S.; Gorter, T.M.; Rienstra, M.; Vos, M.J.; Kema, I.P.; van der Ley, C.P.; Bakker, S.J.L.; Bakker, B.M.; de Boer, R.A.; et al. Beyond the gut: Systemic levels of short-chain fatty acids are altered in patients with heart failure. Int. J. Cardiol. 2025, 428, 133124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleishman, J.S.; Kumar, S. Bile acid metabolism and signaling in health and disease: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.C.; Koay, Y.C.; Pan, C.; Zhou, Z.; Tang, W.; Wilcox, J.; Li, X.S.; Zagouras, A.; Marques, F.; Allayee, H.; et al. Indole-3-Propionic Acid Protects Against Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circ. Res. 2024, 134, 371–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chu, M.; Wang, D.; Li, Q.; Lin, J.; Zhao, J. Threshold of phenylacetylglutamine changes: Exponential growth between age and gut microbiota in stroke patients. Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1576777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Guo, Y.; Li, M.; Li, C.; Tan, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Gao, F. Exercise Enhances Branched-Chain Amino Acid Catabolism and Decreases Cardiac Vulnerability to Myocardial Ischemic Injury. Cells 2022, 11, 1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworska, K.; Kopacz, W.; Koper, M.; Ufnal, M. Microbiome-Derived Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO) as a Multifaceted Biomarker in Cardiovascular Disease: Challenges and Opportunities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y. Gut microbiota derived metabolites in cardiovascular health and disease. Protein Cell 2018, 9, 416–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.H.; Hazen, S.L. Microbiome, trimethylamine N-oxide, and cardiometabolic disease. Transl. Res. 2017, 179, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Wang, L.; Ou, J.; Peng, D.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, W.; Wang, Y. Gut Microbiota Metabolites and Chronic Diseases: Interactions, Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Hu, Y.; Chen, X.; Luo, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, H. Effects of Gut Microbiota and Metabolites on Heart Failure and Its Risk Factors: A Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization Study. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 899746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaglione, S.; Di Chiara, T.; Daidone, M.; Tuttolomondo, A. Effects of the Mediterranean Diet on the Components of Metabolic Syndrome Concerning the Cardiometabolic Risk. Nutrients 2025, 17, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Y.; Sharma, B.; Jain, C.K. Advanced Membrane Simulations in Probiotics and Gut Microbiome Interaction Research: The Current Trends and Insights. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2025, 31, 2723–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondanelli, M.; Borromeo, S.; Cavioni, A.; Gasparri, C.; Gattone, I.; Genovese, E.; Lazzarotti, A.; Minonne, L.; Moroni, A.; Patelli, Z.; et al. Therapeutic Strategies to Modulate Gut Microbial Health: Approaches for Chronic Metabolic Disorder Management. Metabolites 2025, 15, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Klipfell, E.; Bennett, B.J.; Koeth, R.; Levison, B.S.; Dugar, B.; Feldstein, A.E.; Britt, E.B.; Fu, X.; Chung, Y.M.; et al. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature 2011, 472, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, B.J.; de Aguiar Vallim, T.Q.; Wang, Z.; Shih, D.M.; Meng, Y.; Gregory, J.; Allayee, H.; Lee, R.; Graham, M.; Crooke, R.; et al. Trimethylamine-N-oxide, a metabolite associated with atherosclerosis, exhibits complex genetic and dietary regulation. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktaviono, Y.H.; Dyah Lamara, A.; Saputra, P.B.T.; Arnindita, J.N.; Pasahari, D.; Saputra, M.E.; Suasti, N.M.A. The roles of trimethylamine-N-oxide in atherosclerosis and its potential therapeutic aspect: A literature review. Biomol. Biomed. 2023, 23, 936–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Chen, Y.; Gua, C.; Li, X. Elevated Circulating Trimethylamine N-Oxide Levels Contribute to Endothelial Dysfunction in Aged Rats through Vascular Inflammation and Oxidative Stress. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Gregory, J.C.; Org, E.; Buffa, J.A.; Gupta, N.; Wang, Z.; Li, L.; Fu, X.; Wu, Y.; Mehrabian, M.; et al. Gut Microbial Metabolite TMAO Enhances Platelet Hyperreactivity and Thrombosis Risk. Cell 2016, 165, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schugar, R.C.; Shih, D.M.; Warrier, M.; Helsley, R.N.; Burrows, A.; Ferguson, D.; Brown, A.L.; Gromovsky, A.D.; Heine, M.; Chatterjee, A.; et al. The TMAO-Producing Enzyme Flavin-Containing Monooxygenase 3 Regulates Obesity and the Beiging of White Adipose Tissue. Cell Rep. 2017, 19, 2451–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamoorthy, N.K.; Kalyan, M.; Hediyal, T.A.; Anand, N.; Kendaganna, P.H.; Pendyala, G.; Yelamanchili, S.V.; Yang, J.; Chidambaram, S.B.; Sakharkar, M.K.; et al. Role of the Gut Bacteria-Derived Metabolite Phenylacetylglutamine in Health and Diseases. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 3164–3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, P.P.; Gogonea, V.; Sweet, W.; Mohan, M.L.; Singh, K.D.; Anderson, J.T.; Mallela, D.; Witherow, C.; Kar, N.; Stenson, K.; et al. Gut microbe-generated phenylacetylglutamine is an endogenous allosteric modulator of beta2-adrenergic receptors. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemet, I.; Saha, P.P.; Gupta, N.; Zhu, W.; Romano, K.A.; Skye, S.M.; Cajka, T.; Mohan, M.L.; Li, L.; Wu, Y.; et al. A Cardiovascular Disease-Linked Gut Microbial Metabolite Acts via Adrenergic Receptors. Cell 2020, 180, 862–877.e822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Chiang, J.Y. Regulation of bile acid and cholesterol metabolism by PPARs. PPAR Res. 2009, 2009, 501739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Perez, O.; Cruz-Ramon, V.; Chinchilla-Lopez, P.; Mendez-Sanchez, N. The Role of the Gut Microbiota in Bile Acid Metabolism. Ann. Hepatol. 2017, 16, s15–s20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, A.; Kumar, V. The gut microbiota-bile acid axis: A crucial regulator of immune function and metabolic health. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 41, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hylemon, P.B.; Zhou, H.; Pandak, W.M.; Ren, S.; Gil, G.; Dent, P. Bile acids as regulatory molecules. J. Lipid Res. 2009, 50, 1509–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, J.; Hollister, K.; Sowers, L.C.; Forman, B.M. Endogenous bile acids are ligands for the nuclear receptor FXR/BAR. Mol. Cell 1999, 3, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staudinger, J.L.; Goodwin, B.; Jones, S.A.; Hawkins-Brown, D.; MacKenzie, K.I.; LaTour, A.; Liu, Y.; Klaassen, C.D.; Brown, K.K.; Reinhard, J.; et al. The nuclear receptor PXR is a lithocholic acid sensor that protects against liver toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 3369–3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makishima, M.; Lu, T.T.; Xie, W.; Whitfield, G.K.; Domoto, H.; Evans, R.M.; Haussler, M.R.; Mangelsdorf, D.J. Vitamin D receptor as an intestinal bile acid sensor. Science 2002, 296, 1313–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keitel, V.; Reinehr, R.; Gatsios, P.; Rupprecht, C.; Gorg, B.; Selbach, O.; Haussinger, D.; Kubitz, R. The G-protein coupled bile salt receptor TGR5 is expressed in liver sinusoidal endothelial cells. Hepatology 2007, 45, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.C.; Chang, W.T.; Kuo, F.Y.; Chen, Z.C.; Li, Y.; Cheng, J.T. TGR5 activation ameliorates hyperglycemia-induced cardiac hypertrophy in H9c2 cells. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zuo, Y.; Huang, K.; Deng, L.; Liao, B.; Zhong, Y.; Feng, J. Takeda G protein-coupled receptor 5 (TGR5): An attractive therapeutic target for aging-related cardiovascular diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1493662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, D.; He, J.; He, X. The role of bile acid receptor TGR5 in regulating inflammatory signalling. Scand. J. Immunol. 2024, 99, e13361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki-Anzai, S.; Masuda, M.; Levi, M.; Keenan, A.L.; Miyazaki, M. Dual activation of the bile acid nuclear receptor FXR and G-protein-coupled receptor TGR5 protects mice against atherosclerosis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e108270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levi, M. Role of Bile Acid-Regulated Nuclear Receptor FXR and G Protein-Coupled Receptor TGR5 in Regulation of Cardiorenal Syndrome (Cardiovascular Disease and Chronic Kidney Disease). Hypertension 2016, 67, 1080–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, G.; Passeri, D.; De Franco, F.; Ciaccioli, G.; Donadio, L.; Rizzo, G.; Orlandi, S.; Sadeghpour, B.; Wang, X.X.; Jiang, T.; et al. Functional characterization of the semisynthetic bile acid derivative INT-767, a dual farnesoid X receptor and TGR5 agonist. Mol. Pharmacol. 2010, 78, 617–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.X.; Edelstein, M.H.; Gafter, U.; Qiu, L.; Luo, Y.; Dobrinskikh, E.; Lucia, S.; Adorini, L.; D’Agati, V.D.; Levi, J.; et al. G Protein-Coupled Bile Acid Receptor TGR5 Activation Inhibits Kidney Disease in Obesity and Diabetes. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 27, 1362–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, P.; Liu, H.; Boehme, S.; Xie, C.; Krausz, K.W.; Gonzalez, F.; Chiang, J.Y.L. Farnesoid X receptor induces Takeda G-protein receptor 5 cross-talk to regulate bile acid synthesis and hepatic metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 11055–11069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Chen, J.; Jiang, L.; Geng, T.; Tian, S.; Liao, Y.; Yang, K.; Zheng, Y.; He, M.; Tang, H.; et al. Gut microbiota-derived secondary bile acids, bile acids receptor polymorphisms, and risk of cardiovascular disease in individuals with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: A cohort study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 119, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhou, J.; Wu, W.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, X. The Role of Bile Acids in Cardiovascular Diseases: From Mechanisms to Clinical Implications. Aging Dis. 2023, 14, 261–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, B.; Tong, J.; Hao, H.; Yang, Z.; Chen, K.; Xu, H.; Wang, A. Bile acid coordinates microbiota homeostasis and systemic immunometabolism in cardiometabolic diseases. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 2129–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, C.R.; Alaeddine, L.M.; Wessendorf-Rodriguez, K.A.; Turner, R.; Elmastas, M.; Hover, J.D.; Murphy, A.N.; Ryden, M.; Mejhert, N.; Metallo, C.M.; et al. Impaired branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) catabolism during adipocyte differentiation decreases glycolytic flux. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 108004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimou, A.; Tsimihodimos, V.; Bairaktari, E. The Critical Role of the Branched Chain Amino Acids (BCAAs) Catabolism-Regulating Enzymes, Branched-Chain Aminotransferase (BCAT) and Branched-Chain alpha-Keto Acid Dehydrogenase (BCKD), in Human Pathophysiology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongsomboon, W.; Serra, D.O.; Possling, A.; Hadjineophytou, C.; Hengge, R.; Cegelski, L. Phosphoethanolamine cellulose: A naturally produced chemically modified cellulose. Science 2018, 359, 334–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- den Besten, G.; van Eunen, K.; Groen, A.K.; Venema, K.; Reijngoud, D.J.; Bakker, B.M. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 2013, 54, 2325–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Jian, Y.P.; Zhang, Y.N.; Li, Y.; Gu, L.T.; Sun, H.H.; Liu, M.D.; Zhou, H.L.; Wang, Y.S.; Xu, Z.X. Short-chain fatty acids in diseases. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 21, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ney, L.M.; Wipplinger, M.; Grossmann, M.; Engert, N.; Wegner, V.D.; Mosig, A.S. Short chain fatty acids: Key regulators of the local and systemic immune response in inflammatory diseases and infections. Open Biol. 2023, 13, 230014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.; He, C.; An, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fu, W.; Wang, M.; Shan, Z.; Xie, J.; Yang, Y.; et al. The Role of Short Chain Fatty Acids in Inflammation and Body Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parada Venegas, D.; De la Fuente, M.K.; Landskron, G.; Gonzalez, M.J.; Quera, R.; Dijkstra, G.; Harmsen, H.J.M.; Faber, K.N.; Hermoso, M.A. Short Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs)-Mediated Gut Epithelial and Immune Regulation and Its Relevance for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorburn, A.N.; Macia, L.; Mackay, C.R. Diet, metabolites, and “western-lifestyle” inflammatory diseases. Immunity 2014, 40, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Yu, B.; Sun, J.; Liu, Z.; Chen, H.; Ge, L.; Chen, D. Short-chain fatty acids can improve lipid and glucose metabolism independently of the pig gut microbiota. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 12, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles-Vera, I.; Toral, M.; de la Visitacion, N.; Aguilera-Sanchez, N.; Redondo, J.M.; Duarte, J. Protective Effects of Short-Chain Fatty Acids on Endothelial Dysfunction Induced by Angiotensin II. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolomaeus, H.; Balogh, A.; Yakoub, M.; Homann, S.; Marko, L.; Hoges, S.; Tsvetkov, D.; Krannich, A.; Wundersitz, S.; Avery, E.G.; et al. Short-Chain Fatty Acid Propionate Protects from Hypertensive Cardiovascular Damage. Circulation 2019, 139, 1407–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, D.M.; Shihata, W.A.; Jama, H.A.; Tsyganov, K.; Ziemann, M.; Kiriazis, H.; Horlock, D.; Vijay, A.; Giam, B.; Vinh, A.; et al. Deficiency of Prebiotic Fiber and Insufficient Signaling Through Gut Metabolite-Sensing Receptors Leads to Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation 2020, 141, 1393–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, F.Z.; Nelson, E.; Chu, P.Y.; Horlock, D.; Fiedler, A.; Ziemann, M.; Tan, J.K.; Kuruppu, S.; Rajapakse, N.W.; El-Osta, A.; et al. High-Fiber Diet and Acetate Supplementation Change the Gut Microbiota and Prevent the Development of Hypertension and Heart Failure in Hypertensive Mice. Circulation 2017, 135, 964–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhang, S.; Wu, J.; Ye, T.; Wang, S.; Wang, P.; Xing, D. Butyrate-producing bacteria and the gut-heart axis in atherosclerosis. Clin. Chim. Acta 2020, 507, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, M. Recent advancements and comprehensive analyses of butyric acid in cardiovascular diseases. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12, 1608658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owe-Larsson, M.; Drobek, D.; Iwaniak, P.; Kloc, R.; Urbanska, E.M.; Chwil, M. Microbiota-Derived Tryptophan Metabolite Indole-3-Propionic Acid-Emerging Role in Neuroprotection. Molecules 2025, 30, 3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querio, G.; Antoniotti, S.; Geddo, F.; Levi, R.; Gallo, M.P. Modulation of Endothelial Function by TMAO, a Gut Microbiota-Derived Metabolite. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsulami, M.; Alamri, H.; Barhoumi, T.; Munawar, N.; Alghanem, B. The effect of TMAO on aging-associated cardiovascular and metabolic pathways and emerging therapies. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2025, 480, 5659–5669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanmugham, M.; Bellanger, S.; Leo, C.H. Gut-Derived Metabolite, Trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) in Cardio-Metabolic Diseases: Detection, Mechanism, and Potential Therapeutics. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Bosch, C.; Boorman, E.; Zunszain, P.A.; Mann, G.E. Short-chain fatty acids as modulators of redox signaling in health and disease. Redox Biol. 2021, 47, 102165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicks, L.M.T. Butyrate Produced by Gut Microbiota Regulates Atherosclerosis: A Narrative Review of the Latest Findings. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, T.; Li, D.; Sun, F.; Pan, L.; Wang, A.; Li, X.; Bao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zheng, F.; Yue, H. Indole Propionic Acid Regulates Gut Immunity: Mechanisms of Metabolite-Driven Immunomodulation and Barrier Integrity. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 35, e2503045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.A.; Garaci, E.; Frustaci, A.; Fini, M.; Costantini, C.; Oikonomou, V.; Nunzi, E.; Puccetti, P.; Romani, L. Host-microbe tryptophan partitioning in cardiovascular diseases. Pharmacol. Res. 2023, 198, 106994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roager, H.M.; Licht, T.R. Microbial tryptophan catabolites in health and disease. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Gimenez, R.; Ahmed-Khodja, W.; Molina, Y.; Peiro, O.M.; Bonet, G.; Carrasquer, A.; Fragkiadakis, G.A.; Bullo, M.; Bardaji, A.; Papandreou, C. Gut Microbiota-Derived Metabolites and Cardiovascular Disease Risk: A Systematic Review of Prospective Cohort Studies. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorucci, S.; Marchiano, S.; Distrutti, E.; Biagioli, M. Bile acids and their receptors in hepatic immunity. Liver Res. 2025, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punzo, A.; Silla, A.; Fogacci, F.; Perillo, M.; Cicero, A.F.G.; Caliceti, C. Bile Acids and Bilirubin Role in Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Cardiovascular Diseases. Diseases 2024, 12, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonch-Cerbu, A.K.; Boicean, A.G.; Stoia, O.M.; Teodoru, M. Gut Microbiota-Derived Metabolites in Atherosclerosis: Pathways, Biomarkers, and Targets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, T.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Qiu, H.J. Short-chain fatty acids: Key antiviral mediators of gut microbiota. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1614879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Chen, C.; Gao, J. Extensive Summary of the Important Roles of Indole Propionic Acid, a Gut Microbial Metabolite in Host Health and Disease. Nutrients 2022, 15, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, B.; Wang, L.; Chiang, J.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Klaassen, C.D.; Guo, G.L. Mechanism of tissue-specific farnesoid X receptor in suppressing the expression of genes in bile-acid synthesis in mice. Hepatology 2012, 56, 1034–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, J.Y.L.; Ferrell, J.M. Discovery of farnesoid X receptor and its role in bile acid metabolism. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2022, 548, 111618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Umar, S.; Rust, B.; Lazarova, D.; Bordonaro, M. Secondary Bile Acids and Short Chain Fatty Acids in the Colon: A Focus on Colonic Microbiome, Cell Proliferation, Inflammation, and Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orozco-Aguilar, J.; Simon, F.; Cabello-Verrugio, C. Redox-Dependent Effects in the Physiopathological Role of Bile Acids. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 4847941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Wei, H.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, H.; Hang, W.; Wu, J.; Wang, D.W. Gut microbiota-dependent phenylacetylglutamine in cardiovascular disease: Current knowledge and new insights. Front. Med. 2024, 18, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, V.L.; Martins, J.R.; Queiroz-Junior, C.M.; Hottz, E.D.; Teixeira, M.M.; Costa, V.V. Mechanisms of Thromboinflammation in Viral Infections—A Narrative Review. Viruses 2025, 17, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querio, G.; Antoniotti, S.; Geddo, F.; Levi, R.; Gallo, M.P. Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO) Impairs Purinergic Induced Intracellular Calcium Increase and Nitric Oxide Release in Endothelial Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Li, M.L.; Zeng, G.; Xu, X.Y.; Yin, S.H.; Xu, C.; Li, L.; Wen, K.; Yu, X.H.; Wang, G. Gut microbiota-derived metabolite phenylacetylglutamine in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Pharmacol. Res. 2025, 217, 107794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lymperopoulos, A.; Suster, M.S.; Borges, J.I. Short-Chain Fatty Acid Receptors and Cardiovascular Function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, J.Y.L.; Ferrell, J.M. Bile acid receptors FXR and TGR5 signaling in fatty liver diseases and therapy. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2020, 318, G554–G573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, C.; Wang, Z.; Dou, X.; Yang, Q.; Ning, Y.; Kao, S.; Sang, X.; Hao, M.; Wang, K.; Peng, M.; et al. Farnesoid X receptor: From Structure to Function and Its Pharmacology in Liver Fibrosis. Aging Dis. 2024, 15, 1508–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, X.; Qin, L.; Wu, D.; Xie, J.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; He, Y. Research Progress of Takeda G Protein-Coupled Receptor 5 in Metabolic Syndrome. Molecules 2023, 28, 5870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pak, J.M.; Adeagbo, A.S.; Triggle, C.R.; Shaffer, E.A.; Lee, S.S. Mechanism of bile salt vasoactivity: Dependence on calcium channels in vascular smooth muscle. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994, 112, 1209–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raufman, J.P.; Cheng, K.; Zimniak, P. Activation of muscarinic receptor signaling by bile acids: Physiological and medical implications. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2003, 48, 1431–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Zhu, Y.; Hu, G.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, L. Gut microbiome and metabolites, the future direction of diagnosis and treatment of atherosclerosis? Pharmacol. Res. 2023, 187, 106586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vourakis, M.; Mayer, G.; Rousseau, G. The Role of Gut Microbiota on Cholesterol Metabolism in Atherosclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuerhongjiang, G.; Guo, M.; Qiao, X.; Lou, B.; Wang, C.; Wu, H.; Wu, Y.; Yuan, Z.; She, J. Interplay Between Gut Microbiota and Amino Acid Metabolism in Heart Failure. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 752241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Feng, L.; Pei, Z.; Zhao, J.; Lu, S.; Lu, W. Gut microbiota metabolism of branched-chain amino acids and their metabolites can improve the physiological function of aging mice. Aging Cell 2025, 24, e14434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrigo, J.; Olguin, H.; Tacchi, F.; Orozco-Aguilar, J.; Valero-Breton, M.; Soto, J.; Castro-Sepulveda, M.; Elorza, A.A.; Simon, F.; Cabello-Verrugio, C. Cholic and deoxycholic acids induce mitochondrial dysfunction, impaired biogenesis and autophagic flux in skeletal muscle cells. Biol. Res. 2023, 56, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Churova, M.V.; Shulgina, N.; Kuritsyn, A.; Krupnova, M.Y.; Nemova, N.N. Muscle-specific gene expression and metabolic enzyme activities in Atlantic salmon Salmo salar L. fry reared under different photoperiod regimes. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020, 239, 110330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Chang, M.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xue, C.; Yanagita, T.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y. Trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO)-induced atherosclerosis is associated with bile acid metabolism. Lipids Health Dis. 2018, 17, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Q.; He, C.; Fu, C.; Wei, Q. The role of the gut microbiota in health and cardiovascular diseases. Mol. Biomed. 2022, 3, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; He, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, S.; Deng, L.; Zhong, Y.; Liao, B.; Wei, Y.; Feng, J. TGR5 signalling in heart and brain injuries: Focus on metabolic and ischaemic mechanisms. Neurobiol. Dis. 2024, 192, 106428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano, K.A.; Nemet, I.; Prasad Saha, P.; Haghikia, A.; Li, X.S.; Mohan, M.L.; Lovano, B.; Castel, L.; Witkowski, M.; Buffa, J.A.; et al. Gut Microbiota-Generated Phenylacetylglutamine and Heart Failure. Circ. Heart Fail. 2023, 16, e009972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yafarova, A.A.; Dementeva, E.V.; Zlobovskaya, O.A.; Sheptulina, A.F.; Lopatukhina, E.V.; Timofeev, Y.S.; Glazunova, E.V.; Lyundup, A.V.; Doludin, Y.V.; Kiselev, A.R.; et al. Gut Microbiota and Metabolic Alterations Associated with Heart Failure and Coronary Artery Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, L.; Zhang, H.; Xiang, Q.; Hu, H.; Zhai, C.; Xu, S.; Tian, H. Role of Trimethylamine N-Oxide in Heart Failure. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 25, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missailidis, C.; Hallqvist, J.; Qureshi, A.R.; Barany, P.; Heimburger, O.; Lindholm, B.; Stenvinkel, P.; Bergman, P. Serum Trimethylamine-N-Oxide Is Strongly Related to Renal Function and Predicts Outcome in Chronic Kidney Disease. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0141738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, P.; Li, S.; Gao, Y.; Xing, Y. From heart failure and kidney dysfunction to cardiorenal syndrome: TMAO may be a bridge. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1291922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaritei, O.; Mierlan, O.L.; Dinu, C.A.; Chiscop, I.; Matei, M.N.; Gutu, C.; Gurau, G. TMAO and Cardiovascular Disease: Exploring Its Potential as a Biomarker. Medicina 2025, 61, 1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Liu, Z.; Ren, S.; Zhu, J.; Morisawa, N.; Chua, G.L.; Zhang, X.; Wong, Y.K.; Su, L.; Wong, M.X.; et al. BCAA catabolism targeted therapy for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Theranostics 2025, 15, 6257–6273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzelas, D.A.; Pitoulias, A.G.; Telakis, Z.C.; Kalogirou, T.E.; Tachtsi, M.D.; Christopoulos, D.C.; Pitoulias, G.A. Incidence and risk factors of postimplantation syndrome after elective endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. Int. Angiol. 2022, 41, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chulenbayeva, L.; Issilbayeva, A.; Sailybayeva, A.; Bekbossynova, M.; Kozhakhmetov, S.; Kushugulova, A. Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Their Metabolic Interactions in Heart Failure. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Cai, B.; Sun, Y.; Deng, H.; Wang, H.; Qiao, Z. Alteration of the gut microbiota and metabolite phenylacetylglutamine in patients with severe chronic heart failure. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 1076806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Grange, M.; Pospich, S.; Wagner, T.; Kho, A.L.; Gautel, M.; Raunser, S. Structures from intact myofibrils reveal mechanism of thin filament regulation through nebulin. Science 2022, 375, eabn1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeth, R.A.; Wang, Z.; Levison, B.S.; Buffa, J.A.; Org, E.; Sheehy, B.T.; Britt, E.B.; Fu, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, L.; et al. Intestinal microbiota metabolism of L-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasecka, A.; Fidali, O.; Klebukowska, A.; Jasinska-Gniadzik, K.; Szwed, P.; Witkowska, K.; Eyileten, C.; Postula, M.; Grabowski, M.; Filipiak, K.J.; et al. Plasma concentration of TMAO is an independent predictor of adverse outcomes in patients after acute myocardial infarction. Postep. Kardiol. Interwencyjnej 2023, 19, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, Q.; Liu, K.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y. A Mendelian randomization study of the causal relationship between dietary factors and venous thromboembolism. Medicine 2025, 104, e43565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lijfering, W.M.; Cannegieter, S.C. Nutrition and venous thrombosis: An exercise in thinking about survivor bias. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost. 2019, 3, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, S.; Herpai, D.M.; Rodriguez, A.; Huang, Y.; Chou, J.; Hsu, F.C.; Seals, D.; Mott, R.; Miller, L.D.; Debinski, W. The Presence and Potential Role of ALDH1A2 in the Glioblastoma Microenvironment. Cells 2021, 10, 2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, M.; Moffat, D.; Latham, B.; Badrick, T. Review of diagnostic error in anatomical pathology and the role and value of second opinions in error prevention. J. Clin. Pathol. 2018, 71, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, X.S.; Wang, Z.; de Oliveira Otto, M.C.; Lemaitre, R.N.; Fretts, A.; Sotoodehnia, N.; Budoff, M.; Nemet, I.; DiDonato, J.A.; et al. Trimethylamine N-oxide is associated with long-term mortality risk: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 1608–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappuccio, G.; Genesio, R.; Ronga, V.; Casertano, A.; Izzo, A.; Riccio, M.P.; Bravaccio, C.; Salerno, M.C.; Nitsch, L.; Andria, G.; et al. Complex chromosomal rearrangements causing Langer-Giedion syndrome atypical phenotype: Genotype-phenotype correlation and literature review. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2014, 164, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, X.; Fan, Q.; Yang, Q.; Pan, R.; Zhuang, L.; Tao, R. Phenylacetylglutamine as a risk factor and prognostic indicator of heart failure. ESC Heart Fail. 2022, 9, 2645–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwi, Q.G.; Lopaschuk, G.D. Branched-Chain Amino Acid Metabolism in the Failing Heart. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2023, 37, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canyelles, M.; Borras, C.; Rotllan, N.; Tondo, M.; Escola-Gil, J.C.; Blanco-Vaca, F. Gut Microbiota-Derived TMAO: A Causal Factor Promoting Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiners, F.; Ortega-Matienzo, A.; Fuellen, G.; Barrantes, I. Gut microbiome-mediated health effects of fiber and polyphenol-rich dietary interventions. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1647740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagpal, R.; Shively, C.A.; Register, T.C.; Craft, S.; Yadav, H. Gut microbiome-Mediterranean diet interactions in improving host health. F1000Research 2019, 8, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merra, G.; Noce, A.; Marrone, G.; Cintoni, M.; Tarsitano, M.G.; Capacci, A.; De Lorenzo, A. Influence of Mediterranean Diet on Human Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2020, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieux, F.; Soler, L.G.; Touazi, D.; Darmon, N. High nutritional quality is not associated with low greenhouse gas emissions in self-selected diets of French adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 569–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Gao, Y.; Xu, W. Dietary Fiber Intake and Gut Microbiota in Human Health. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canfora, E.E.; Hermes, G.D.A.; Muller, M.; Bastings, J.; Vaughan, E.E.; van Den Berg, M.A.; Holst, J.J.; Venema, K.; Zoetendal, E.G.; Blaak, E.E. Fiber mixture-specific effect on distal colonic fermentation and metabolic health in lean but not in prediabetic men. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2009297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, Y.Q.J.; Chong, B.; Soong, R.Y.; Yong, C.L.; Chew, N.W.; Chew, H.S.J. Effects of probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics on anthropometric, cardiometabolic and inflammatory markers: An umbrella review of meta-analyses. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 43, 1563–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Z.; Yang, S.; Tang, C.; Li, D.; Kan, Y.; Yao, L. New insights into microbial bile salt hydrolases: From physiological roles to potential applications. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1513541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Jiang, P.P.; Yu, D.; Liao, G.C.; Wu, S.L.; Fang, A.P.; Chen, P.Y.; Wang, X.Y.; Luo, Y.; Long, J.A.; et al. Effects of probiotic supplementation on serum trimethylamine-N-oxide level and gut microbiota composition in young males: A double-blinded randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutagy, N.E.; Neilson, A.P.; Osterberg, K.L.; Smithson, A.T.; Englund, T.R.; Davy, B.M.; Hulver, M.W.; Davy, K.P. Probiotic supplementation and trimethylamine-N-oxide production following a high-fat diet. Obesity 2015, 23, 2357–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baugh, M.E.; Steele, C.N.; Angiletta, C.J.; Mitchell, C.M.; Neilson, A.P.; Davy, B.M.; Hulver, M.W.; Davy, K.P. Inulin Supplementation Does Not Reduce Plasma Trimethylamine N-Oxide Concentrations in Individuals at Risk for Type 2 Diabetes. Nutrients 2018, 10, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, M.; Duarte, J. Probiotics and Prebiotics in Cardiovascular Diseases. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlidou, E.; Fasoulas, A.; Mantzorou, M.; Giaginis, C. Clinical Evidence on the Potential Beneficial Effects of Probiotics and Prebiotics in Cardiovascular Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, M.; Brandl, B.; Neuhaus, K.; Wudy, S.; Kleigrewe, K.; Hauner, H.; Skurk, T. Effect of dietary fiber on trimethylamine-N-oxide production after beef consumption and on gut microbiota: MEATMARK—A randomized cross-over study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2025, 79, 980–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalnins, G.; Kuka, J.; Grinberga, S.; Makrecka-Kuka, M.; Liepinsh, E.; Dambrova, M.; Tars, K. Structure and Function of CutC Choline Lyase from Human Microbiota Bacterium Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 21732–21740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craciun, S.; Balskus, E.P. Microbial conversion of choline to trimethylamine requires a glycyl radical enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 21307–21312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.