Abstract

Objective: To explore the preventive effect and mechanism of melatonin on high-fructose-induced renal injury in mice. Methods: A total of forty male C57BL/6J mice aged six weeks were randomly assigned to four groups: control group (CON), melatonin group (MLT), fructose group (FRU), and fructose + melatonin group (FRU + MLT). The concentration of the fructose solution was 30%, and the dose of melatonin was 10 mg/kg/day by intragastric administration. The experiment lasts for 10 weeks. Results: Liquid intake and energy intake were comparable between the FRU and FRU + MLT, both of which were significantly higher than that in the CON and MLT. MLT inhibited fructose-induced increased levels in serum creatinine (Cre), serum urea nitrogen (BUN), serum uric acid (UA), serum triglyceride (TG), renal kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1), and renal TG. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining and Oil Red O (ORO) staining showed that MLT alleviated renal tubular dilatation, loss of brush border, epithelial cell detachment and lipid accumulation. Transmission electron microscope (TEM) observations showed that MLT increased autophagic vacuoles among mitochondria. Western blot analysis showed that, compared with the FRU, the FRU + MLT had elevated expression of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) phosphorylation, along with a significant increase in the expression of its downstream mitophagy-related proteins (including PINK1, Parkin, LC3 II, and Beclin1), whereas the expression of p62 was markedly decreased. Furthermore, the expression levels of FAO-related proteins (including PPARα and CPT1A) in the FRU + MLT were significantly upregulated. Conclusions: MLT alleviates renal injury caused by high-fructose exposure in male mice and its mechanism might be associated with the regulation of mitophagy and fatty acid oxidation.

1. Introduction

Fructose, a monosaccharide naturally present in fruits, serves as the primary component of high-fructose corn syrup and is frequently employed as a sweetener in beverages, baked products, and confectionery [1,2,3]. In recent decades, the intake of fructose has increased dramatically, especially in Western countries [4,5]. High fructose exposure has been proven to cause renal injury [6,7]. Animal studies suggest that feeding mice a 10–30% fructose solution for about 10 consecutive weeks can lead to tubular dilation, renal lipid accumulation, and renal dysfunction [8,9,10].

The kidney has abundant mitochondria, and the normal activity of these organelles is crucial for a well-functioning kidney [11,12]. Mitochondrial dysfunction is implicated in the pathogenesis of renal injury induced by high-fructose diets [13,14]. Generally, when renal cells are in a state of stress or exposed to adverse stimuli, the dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) in the kidneys is abnormally upregulated, which accelerates mitochondrial fission. In contrast, the reduced expression of mitofusin1/2 (Mfn1/Mfn2) and optic atrophy 1 (OPA1) impairs mitochondrial fusion [15,16,17]. This imbalance ultimately results in excessive mitochondrial fragmentation and structural disorganization [18,19]. Damaged mitochondria recruit and accumulate PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1). PINK1 further recruits Parkin to ubiquitinate mitochondrial proteins, and this process marks damaged mitochondria for autophagic clearance to preserve mitochondrial homeostasis [20]. Mitophagy is widely recognized as a protective mechanism against kidney dysfunction [20,21,22]. Studies have demonstrated that high-fructose exposure not only triggers excessive mitochondrial fragmentation and structural disorder but also inhibits mitophagy [13]. Inhibition of mitophagy results in the failure to clear damaged mitochondria, which aggravates mitochondrial dysfunction and subsequently contributes to renal injury [23,24]. Additionally, high-fructose exposure can significantly impair the fatty acid oxidation (FAO) function in renal proximal tubular epithelial cells, leading to lipid accumulation in the kidneys [25,26,27]. As a key mitochondrial-dependent energy metabolism pathway, the impairment of FAO manifests as mitochondrial dysfunction: it not only reduces mitochondrial ATP production, failing to meet the physiological needs of renal cells, but also promotes the massive generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and accelerates the progression of renal injury [28,29]. Therefore, activating mitophagy and regulating mitochondrial FAO may represent effective strategies to alleviate high-fructose-induced renal injury.

Melatonin (MLT) is an indoleamine primarily synthesized in the pineal gland, with trace amounts also found in cherries and walnuts [30,31]. Nowadays, MLT has been used as a dietary supplement for the prevention and adjuvant treatment of conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and chronic neurodegenerative disorders [32,33,34]. Recently, the impact of MLT on kidney diseases has attracted attention. Population studies found that patients with chronic kidney disease were accompanied by a decrease in endogenous MLT levels [35]. Animal experiments indicated that MLT intervention could alleviate the senescence and apoptosis of renal cortical proximal epithelial tubule (HK-2) cells in patients with diabetic nephropathy [36]. MLT plays a preventive and therapeutic role in various diseases by regulating the expression of AMPK [37,38]. AMPK has been confirmed to directly participate in the regulation of mitophagy [39]. Additionally, AMPK is also involved in modulating FAO processes [40]. Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that MLT may ameliorate kidney damage caused by high fructose exposure through AMPK-mediated mitophagy and FAO.

In this study, C57BL/6J mice were allowed free access to a 30% fructose solution and 10 mg/kg MLT was administered via daily intragastric delivery throughout a 10-week experimental period to investigate the preventive efficacy of MLT against high-fructose-induced renal injury. It is the first time to explore its underlying mechanism through the pathways of mitophagy and FAO.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Experimental Design

This study was approved by the Experimental Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee of Qingdao University (Approval No. 20231102C574020240113054; Approval Date: 23 September 2024). A power analysis (α = 0.05, power = 0.8) based on the pilot data indicated that a sample size of n = 9 per group would be sufficient to detect a significant intervention effect. A group size of n = 10 was used to accommodate any unexpected losses. A total of forty male C57BL/6 mice, aged six weeks and weighing 20 ± 2 g, were purchased from Beijing Huafukang Biotechnology Co, and housed at 22–24 °C with 40–60% humidity under a normal circadian rhythm.

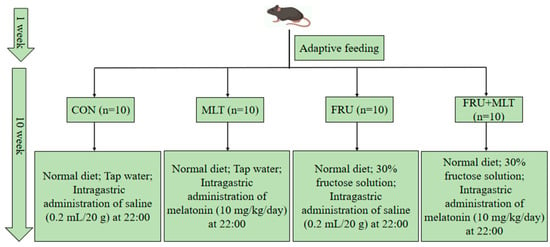

After the acclimation for 1 week, all mice were randomly assigned to four groups after matching for body weight with 10 mice in each group. All subsequent procedures and analyses were performed by investigators blinded to the group allocation. All four groups of animals were fed the same standard diet, and the detailed dietary formulations are provided in Table S1. In the control group (CON), the mice were given tap water and treated intragastrically with normal saline (0.2 mL/20 g). In the melatonin group (MLT), the mice were given tap water and treated intragastrically with 10 mg/kg/day MLT. In the fructose group (FRU), the mice were given 30% (w/v) fructose solution and treated intragastrically with normal saline (0.2 mL/20 g). In the fructose + melatonin group (FRU + MLT), the mice were given 30% (w/v) fructose solution and treated intragastrically with 10 mg/kg/day MLT. Intragastric administration was conducted at 22:00 daily, consistent with previously published studies [41]. Animals in each group had free access to tap water or a 30% fructose solution, respectively. MLT (CAS Number: 73-31-4) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA) and dissolved in 0.9% normal saline before administration. Fructose (purity ≥ 99%) was obtained from Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The experiment lasted 10 weeks, with daily measurements of food and liquid intake. The specific intervention protocol is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Experimental grouping and interventions of the study.

After 10 weeks, all animals were fasted for 12 h and were anesthetized for blood collection and then euthanized. Kidneys were rapidly excised and weighed. Tissues were processed as follows: the right kidneys were used for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, Oil Red O (ORO) staining, BODIPY staining and immunofluorescence. The left kidneys were partially used for ROS detection, another portion was for transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and the remaining part was stored at −80 °C until use.

2.2. Serum Biochemical Analysis

Serum levels of triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TC), creatinine (Cre), urea nitrogen (BUN), and uric acid (UA) were measured by using an AU5400 automatic biochemical analyzer (Beckman, Los Angeles, CA, USA).

2.3. Biochemical and Molecular Analyses of Renal Tissues

Kidney tissues were homogenized in normal saline at a ratio of 1:9 (g:mL) and then centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 15 min. After centrifugation, the supernatant was collected to determine the concentrations of kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1, a renal injury marker; Cat# H436-1-1), TG (Cat# A110-1-1), IL-1β (Cat# H002-1-1), IL-6 (Cat# H007-1-1), TNFα (Cat# H052-1-1), and MDA (Cat#A003-1-1), as well as the enzymatic activities of SOD (Cat# A001-1-1), GSH-Px (Cat# A005-1-1) and CAT (Cat# A007-1-1) in kidney tissues, which were measured with corresponding ELISA kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Biological Engineering Research Institute, Nanjing, China). All samples were assayed in triplicate.

The Western blot scheme follows the standard procedure used in a previous study [42]. Protein extracts were prepared from three independent biological samples per group. Primary antibodies used in this experiment targeted three categories of proteins: (1) mitophagy-related proteins, including AMPK (Cat# ab32047), p-AMPK (Cat# ab133448), PINK1 (Cat# ab216144), Parkin (Cat# ab77924), LC3 II (Cat# ab192890), Beclin1 (Cat# ab207612), and P62 (Cat# ab109012); (2) mitochondrial dynamics-related proteins, including FIS1 (Cat# ab156865), Drp1 (Cat# ab184247), Mfn1 (Cat# ab221661), Mfn2 (Cat# ab124773) and OPA1 (Cat# ab157457); and (3) FAO-related proteins, including PPARα (Cat# ab126285) and CPT1A (Cat# ab128568). β-Actin (Cat# ab6276) was used as the internal loading control. All antibodies were purchased from Abcam plc, Cambridge, UK.

2.4. Renal Ultrastructure Observation

Left kidney tissues were fixed overnight, followed by dehydration, embedding, polymerization, sectioning (50 nm), and staining. Samples were visualized via JEM-1200EX Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM; JEOL, Tokyo, Japan).

2.5. H&E Staining

Right kidney tissues were first immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 24 consecutive hours; after fixation, they were embedded in paraffin and further sectioned into 5-μm-thick slices. Once sectioned, the renal slices were stained using H&E. Renal histopathological alterations were then visualized and imaged under a light microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Three non-consecutive kidney sections per mouse were analyzed.

2.6. ORO Staining

The cryosections of fresh right kidney tissue were stained with the ORO solution and washed using 60% isopropanol and distilled water. Subsequently, nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin and observed under a BX60 light microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). For each mouse, three non-consecutive sections were analyzed to ensure representative sampling.

2.7. BODIPY Staining

Fresh right renal cryosections were first immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 10 min for fixation, then rinsed three times with PBS buffer. Subsequently, the sections were incubated at room temperature for 60 min with 5 μg/mL of BODIPY 493/503 supplied by Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Following additional rinsing, the sections were counterstained using DAPI and then mounted onto slides. Staining results were visualized using an Olympus confocal microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

2.8. Immunofluorescence

Renal paraffin sections (4 μm thick) were employed for immunofluorescence staining. First, the sections were permeabilized using 0.3% Triton X-100 and then blocked with 4% bovine serum albumin (BSA). After blocking, the sections were incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight, followed by incubation with secondary antibodies for 50 min. The primary antibodies utilized included TOM20 (1:1000 dilution, Servicebio (Wuhan, China)) and LC3 (1:500 dilution, Servicebio); additionally, DAPI (Servicebio) was used for nuclear counterstaining. Regions with fluorescent signals were visualized and imaged using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Ten pictures were taken at randomly chosen fields from each section.

2.9. Renal ROS Assay

Kidney tissue homogenates were diluted with PBS solution and then mixed with 2,7-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (Elabscience, Wuhan, China) to incubate for 30 min. After rinsing with PBS and centrifugation, the supernatant was discarded to collect renal cells, resuspended in 0.5 mL of PBS solution, and then the fluorescence value was measured by flow cytometry.

2.10. Renal ATP Measurement and Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number Detection

Renal ATP concentrations were determined via a commercial ATP assay kit (Cat# A095-2-1, Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China) per the kit’s instructions. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) copy number was quantified via real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using a SYBR Green kit (Cat# RR82LR, Takara Bio Inc., Tokyo, Japan). All qPCR reactions were run in triplicate for each independent sample.

2.11. Statistical Analysis

SPSS 23.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Data are presented as means ± standard deviation (SD) if normally distributed, or as median with interquartile range (IQR) otherwise. Normality (Shapiro–Wilk test) and homogeneity of variances (Levene’s test) were assessed. For multi-group comparisons meeting both assumptions, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was used. If the equal variance assumption was violated, Welch’s ANOVA with the Games-Howell test was applied. Non-normally distributed data were analyzed by the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s test. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of MLT on Body Weight and Kidney Index

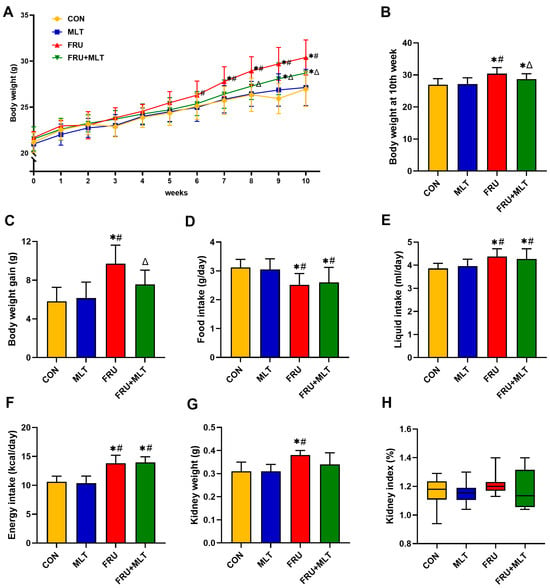

Figure 2A illustrated that no statistically significant differences were observed in initial body weights across the four experimental groups (p > 0.05). Compared to CON, FRU showed a significant elevation in both body weight at the 10th week and total body weight gain; in contrast, FRU + MLT exhibited a marked reduction in these two indices relative to FRU (p < 0.05; Figure 2B,C). Additionally, food consumption in FRU and FRU + MLT was notably lower compared to CON and MLT (p < 0.05; Figure 2D). In contrast, FRU and FRU + MLT had significantly higher liquid intake and energy intake than CON and MLT (p < 0.05; Figure 2E,F). As shown in Figure 2G, compared with the CON, the kidney weight in the FRU was significantly increased (p < 0.05). There were no significant differences in kidney index among the four groups (p > 0.05; Figure 2H).

Figure 2.

Effect of MLT on body weight and kidney index. (A) Body weight. (B) Body weight at 10th week. (C) Body weight gain. (D) Food intake. (E) Liquid intake. (F) Energy intake. (G) Kidney weight. (H) Kidney index. In panels (A–G), data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 10). In panel (H), data are presented as median with IQR (n = 10). * p < 0.05 vs. CON, # p < 0.05 vs. MLT, Δ p < 0.05 vs. FRU.

3.2. Effect of MLT on Serum Biochemical Indicators

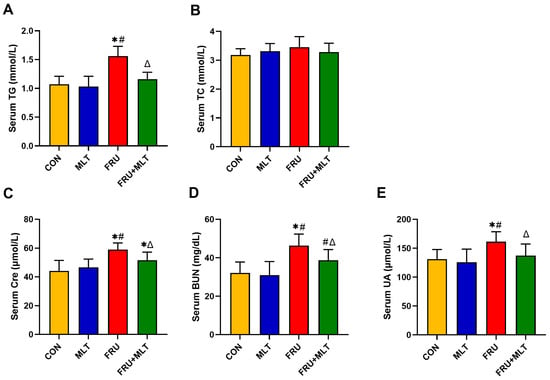

In Figure 3A, the serum level of TG was significantly higher in FRU than in CON (p < 0.05). In comparison to FRU, FRU + MLT had a markedly lowered serum level of TG (p < 0.05). No significant differences were observed in serum TC levels among the four groups (p > 0.05; Figure 3B). The serum Cre, BUN and UA levels in FRU were significantly higher than those in CON (p < 0.05). MLT supplementation significantly reduced the increase in Cre, BUN and UA when compared to FRU (p < 0.05; Figure 3C–E).

Figure 3.

Effect of MLT on serum biochemical indicators. (A) Serum TG. (B) Serum TC. (C) Serum Cre. (D) Serum BUN. (E) Serum UA. The data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 10). * p < 0.05 vs. CON, # p < 0.05 vs. MLT, Δ p < 0.05 vs. FRU.

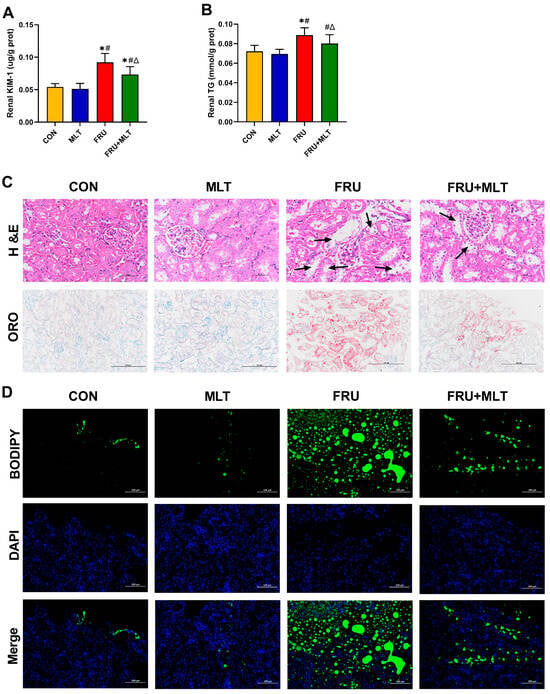

3.3. Effect of MLT on Renal Injury and Renal Lipid Accumulation

KIM-1 is a biomarker of renal injury. Compared with CON, FRU showed an elevated renal KIM-1 level; in contrast, FRU + MLT displayed a marked reduction in renal KIM-1 level relative to FRU (p < 0.05; Figure 4A). Relative to CON, FRU had a significantly higher renal TG level, while FRU + MLT exhibited a significantly normalized renal TG level compared to FRU (p < 0.05; Figure 4B). H&E, ORO and BODIPY staining assays were employed to further assess renal pathological alterations and lipid accumulation. In Figure 3C, H&E staining showed normal morphology in CON. Renal tubular dilatation, loss of brush border and epithelial cell detachment were observed in FRU, while the above pathological changes in FRU + MLT were significantly improved. ORO and BODIPY staining showed obvious lipid accumulation in the kidneys of FRU, while the lipid accumulation in FRU + MLT was significantly improved (Figure 4C,D).

Figure 4.

Effect of MLT on renal injury and renal lipid accumulation. (A) Renal KIM-1. (B) Renal TG. (C) H&E and ORO staining of Kidney (40×, 20×, scale bars: 50 µm, 100 µm) (black arrowhead: renal tubular dilation). (D) BODIPY Staining (20×, scale bars: 100 µm) Lipids stained green and nuclei stained blue. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 10). * p < 0.05 vs. CON, # p < 0.05 vs. MLT, Δ p < 0.05 vs. FRU.

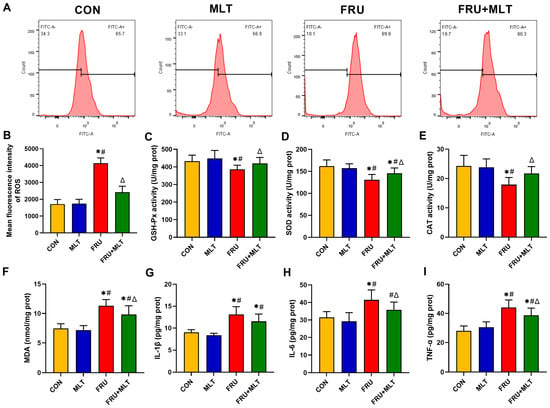

3.4. Effect of MLT on Renal ROS Accumulation, Renal Oxidative Stress and Renal Inflammation

Compared with CON, FRU exhibited a significant elevation in the mean fluorescence intensity of ROS (p < 0.05). Relative to FRU, FRU + MLT showed a marked reduction in ROS mean fluorescence intensity (p < 0.05; Figure 5B). Additionally, when compared to CON, the FRU had an observable decrease in renal GSH-Px, SOD, and CAT activity, alongside a significant increase in renal MDA content (p < 0.05). Furthermore, the FRU + MLT displayed a significant decrease in renal MDA content and a noticeable increase in renal GSH-Px, SOD, and CAT levels relative to the FRU (p < 0.05; Figure 5C–F). As shown in Figure 5G–I, the levels of renal IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in the FRU significantly elevated compared with the CON (p < 0.05), while MLT treatment significantly reversed the elevations of renal IL-6 and TNF-α in FRU (p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Effect of MLT on renal ROS accumulation, renal oxidative stress and renal inflammation. (A) Flow cytometry map of ROS. (B) Mean fluorescence intensity of ROS. (C) GSH-Px activity. (D) SOD activity. (E) CAT activity. (F) MDA content. (G) IL-1β content. (H) IL-6 content. (I) TNF-α content. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 6 per group for ROS flow cytometry and mean fluorescence intensity; n = 10 per group for MDA, GSH-Px, SOD, CAT, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α). * p < 0.05 vs. CON, # p < 0.05 vs. MLT, Δ p < 0.05 vs. FRU.

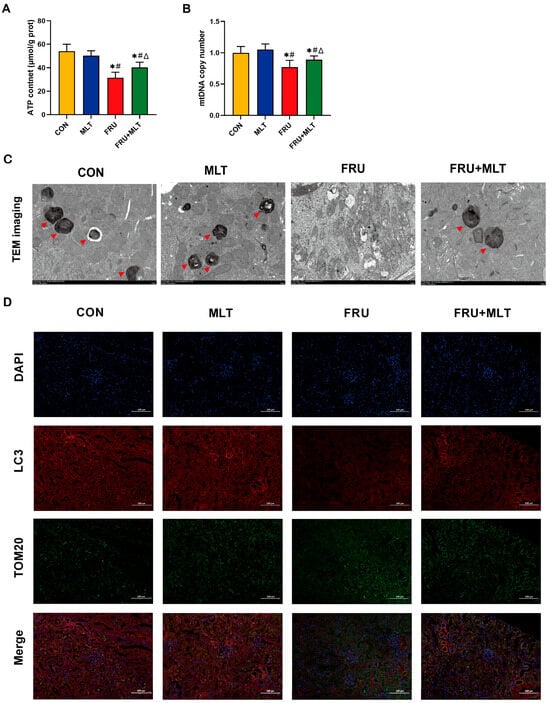

3.5. Effect of MLT on Renal Mitochondrial Damage and Renal Mitophagy

Figure 6A,B demonstrate that FRU had significantly lower ATP content and mtDNA copy number than CON (p < 0.05). Relative to FRU, FRU + MLT exhibited a significant increase in both mtDNA copy number and ATP quantity (p < 0.05). TEM observations revealed that the mitochondrial cristae in the renal tissues of CON had clear and intact structures. However, mice in FRU exhibited significant mitochondrial damage, manifesting as mitochondrial swelling, almost complete loss of cristae structures, and a decrease in observable mitophagosomes. In contrast, renal mitophagy impairment was reversed in FRU + MLT (Figure 6C). Moreover, the colocalization between LC3 and TOM20 was notably reduced in FRU compared to CON. When compared to FRU, the colocalization of LC3 and TOM20 was significantly enhanced in FRU + MLT. MLT promoted the colocalization of LC3 and mitochondrial marker TOM20 as shown by the increase in merged intensity of LC3 with TOM20 puncta (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

Effect of MLT on renal mitochondrial damage and renal mitophagy. (A) ATP content. (B) Mitochondrial DNA copy number. (C) TEM images in the kidney tissues (Red arrowhead indicates mitophagosomes. Scale bar: 2 μm). (D) Representative immunofluorescent images of fluorescence intensity for LC3 (Red, mitophagosome marker) and TOM20 (Green, mitochondrial outer membrane marker). Nuclei are counterstained with DAPI (Blue). Scale bar: 100 μm. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 10 per group for ATP and mitochondrial DNA copy number; n = 6 per group for TEM and immunofluorescent images). * p < 0.05 vs. CON, # p < 0.05 vs. MLT, Δ p < 0.05 vs. FRU.

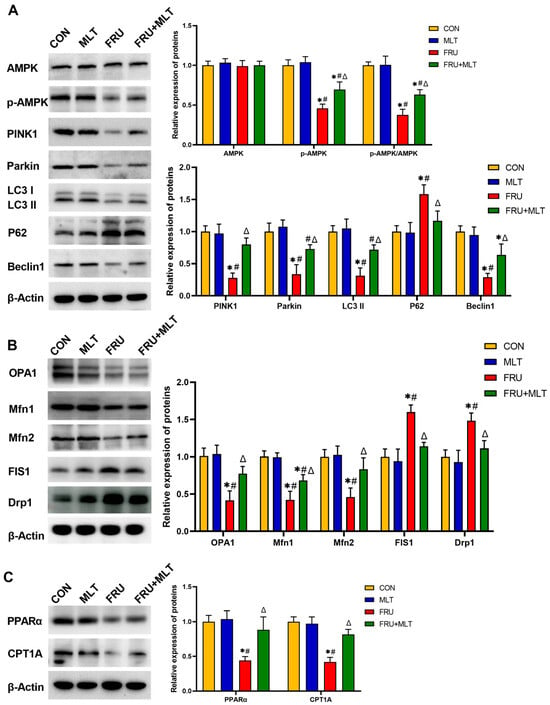

3.6. Effect of MLT on Renal Mitophagy, Mitochondrial Dynamics and FAO-Related Protein Expression

Figure 7A illustrated that, compared to CON, FRU exhibited significant reductions in the protein expression levels of p-AMPK (p < 0.001, Hedges’ g = −4.02), PINK1 (p < 0.001, Hedges’ g = −5.21), Parkin (p < 0.001, Hedges’ g = −3.19), LC3 II (p < 0.001, Hedges’ g = −4.17), and Beclin1 (p = 0.023, Hedges’ g = −2.83), accompanied by a marked increase in P62 expression (p = 0.004, Hedges’ g = 5.72). Relative to FRU, FRU + MLT showed significantly higher protein expression levels of p-AMPK (p = 0.017, Hedges’ g = 1.98), PINK1 (p = 0.001, Hedges’ g = 4.15), Parkin (p = 0.014, Hedges’ g = 2.71), LC3 II (p < 0.001, Hedges’ g = 3.22), and Beclin1 (p = 0.023, Hedges’ g = 1.97), together with a decrease in P62 (p = 0.023, Hedges’ g = −2.18). Figure 7B demonstrated that when compared to CON, FRU showed notably decreased OPA1 (p < 0.001, Hedges’ g = −3.47), Mfn1 (p < 0.001, Hedges’ g = −4.23), and Mfn2 (p = 0.003, Hedges’ g = −3.68) expression and significantly increased FIS1 (p < 0.001, Hedges’ g = 3.27) and Drp1 (p = 0.004, Hedges’ g = 2.98) expression. Relative to FRU, FRU + MLT displayed a significant increase in OPA1 (p = 0.019, Hedges’ g = 2.51), Mfn1 (p = 0.022, Hedges’ g = 1.89) and Mfn2 (p = 0.025, Hedges’ g = 2.14) expression and a notable reduction in the expression levels of FIS1 (p = 0.004, Hedges’ g = −3.82) and Drp1 (p = 0.019, Hedges’ g = −2.87). In terms of PPARα and CPT1A expression (Figure 6C), relative to CON, FRU exhibited dramatically lower levels of PPARα (p = 0.002, Hedges’ g = −4.45) and CPT1A (p < 0.001, Hedges’ g = −0.92). When contrasted with FRU, FRU + MLT showed markedly higher PPARα (p = 0.009, Hedges’ g = 2.56) and CPT1A (p = 0.001, Hedges’ g = 0.53) expression.

Figure 7.

Effect of MLT on renal mitophagy, mitochondrial dynamics and FAO-related protein expression. (A) Protein expression levels related to renal mitophagy. (B) Protein expression levels related to renal mitochondrial dynamics. (C) Protein expression levels related to renal FAO. The data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). * p < 0.05 vs. CON, # p < 0.05 vs. MLT, Δ p < 0.05 vs. FRU.

4. Discussion

Fructose is commonly used as a sweetener and is widely applied in processed foods. Over the years, with the increased consumption of processed foods, the health risks caused by high-fructose exposure have attracted increasing attention [43,44,45,46]. Long-term high-fructose exposure has been proven to induce renal injury. For instance, animal studies have found that drinking a 30% fructose solution for about 10 consecutive weeks induces hyperuricemic nephropathy in mice [8,9,10]. Proactively preventing and managing renal injury caused by high-fructose exposure is of great significance. MLT is an indoleamine primarily synthesized in the pineal gland, and it is present in foods such as cherries and walnuts [47,48]. Nowadays, due to its well-documented anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immune-regulatory effects, MLT has been developed as a therapeutic agent or dietary supplement and used in the treatment of sleep disorders, metabolic syndrome, etc. [49,50,51]. MLT has also been explored for the treatment of various kidney diseases [52,53]. Previous research has shown that MLT exerts an ameliorative effect on diabetic nephropathy, as it can reduce renal cell apoptosis by regulating STAT3 phosphorylation [36]. Moreover, MLT can alleviate diclofenac-induced acute kidney injury through promoting the signaling of Nrf2/HO-1 [54]. MLT also exhibits excellent preventive and therapeutic effects on health issues induced by high-fructose exposure, such as metabolic syndrome, hepatic steatosis [55,56]. However, research on the preventive effect of MLT against high fructose-induced renal injury remains rather limited to date.

To elucidate the preventive effect of MLT on high-fructose-induced renal injury, we divided mice into four groups: CON, MLT, FRU and FRU + MLT. The concentration of the fructose solution is 30%, which was consistent with the intervention doses reported in previous studies [9,10]. The administration of 10 mg/kg of MLT via gavage was reported to effectively alleviate non-alcoholic fatty liver disease induced by a high-fat and high-fructose diet in mice [57], and it can ameliorate anxiety and depression-like behaviors and modulate proteomic changes in triple transgenic mice of Alzheimer’s disease [58]. Moreover, 10 mg/kg MLT attenuated retinal neovascularization and neuroglial dysfunction by inhibiting the HIF-1α-VEGF pathway in oxygen-induced retinopathy mice [59]. Additionally, 10 mg/kg of MLT also exerts protective effects against cadmium exposure-induced and ciprofloxacin-induced nephrotoxicity in previous animal studies [60,61]. Therefore, in this study, we also selected an MLT dose of 10 mg/kg. After 10 weeks of intervention, the serum Cre, BUN and UA levels in the FRU were significantly increased by 33.44%, 44.00%, and 22.98%, respectively, compared with those in the CON. Meanwhile, the renal KIM-1 level was significantly elevated by 69.8% relative to the CON. These findings suggested that mice in the FRU developed mild renal dysfunction. The serum Cre, BUN, UA levels and renal KIM-1 level in the FRU + MLT were significantly decreased compared with those in the FRU. Pathological examination of the kidneys can provide more direct evidence for the assessment of renal injury. In FRU, renal tubular dilatation, loss of brush border, and epithelial cell detachment were observed, while these pathological changes were significantly alleviated in FRU + MLT. The histopathological changes observed were consistent with the alterations in serum renal function indicators and renal KIM-1 levels. Based on the above results, we found that high-fructose exposure induces renal injury, while MLT effectively mitigates it. The mechanism by which MLT mitigates high fructose-induced renal injury has aroused our considerable interest.

The kidney is an organ with high energy demands and is highly dependent on mitochondria for energy production. Mitophagy, a selective autophagic process, eliminates damaged or dysfunctional mitochondria to sustain cellular survival and growth while preventing further cellular damage. In this process, the accumulation of PINK1 signals the recruitment of Parkin to the mitochondrial surface, where Parkin ubiquitinates the damaged mitochondria. P62 then binds to polyubiquitinated mitochondrial proteins and recruits LC3, a marker of autophagosomes. TEM observations revealed dysfunctional autolysosomes in renal tissues of FRU, indicating the presence of mitophagy impairment in the kidneys. Notably, mitochondrial ATP production capacity, mtDNA copy number, and ROS levels serve as direct indicators of renal mitochondrial energy supply, biosynthetic stability, and oxidative stress status, respectively [62,63,64]. In FRU, mitochondrial ATP production and mtDNA copy number were decreased, while ROS levels were elevated. These results demonstrate that high-fructose exposure induces renal injury by disrupting mitochondrial dynamics and inhibiting mitophagy—a finding that aligns with the conclusions of prior research [9,65].

AMPK has been well established as a critical regulator of mitophagy [66]. For example, a recent study found decreased mitochondrial translocation and expression of PINK1 following AMPK inhibition in the renal tubular cell [67]. This finding suggests that AMPK phosphorylation serves as an upstream target of PINK1. In a series of in vivo and in vitro studies, MLT has been well-confirmed to promote AMPK phosphorylation. For example, MLT improves glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity by mitigating inflammation and activating AMPK signaling in a mouse model of sleep fragmentation67 [68]. Moreover, MLT can also inhibit oxalate-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis in HK-2 cells by activating the AMPK pathway68 [69]. MLT can exert antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects by activating AMPK signaling [37,69]. In this study, compared with FRU, the expression level of AMPK phosphorylation in FRU + MLT was increased, and the expression levels of PINK1 and Parkin were also elevated accordingly. Compared with FRU, FRU + MLT had higher mitochondrial ATP production capability, increased mtDNA copy number, and decreased ROS level. Furthermore, the expressions of LC3, Beclin1, OPA1, Mfn1 and Mfn2 in FRU + MLT were upregulated, while P62, FIS1 and Drp1 were downregulated. The above results indicated that the alleviation effect of MLT on high fructose-induced renal injury might be associated with the regulation of mitochondrial homeostasis and mitophagy.

In the kidney, the normal functioning of glomerular filtration and tubular reabsorption and secretion relies on continuous ATP supply. FAO is the main ATP-producing pathway in renal cells [29]. High fructose exposure can impair FAO in the kidney by downregulating PPARα expression [70]. PPARα is a core transcriptional factor that regulates FAO, which can directly bind to the promoter regions of FAO-related genes (including CPT1A) and promote their expression. CPT1A is the rate-limiting enzyme of mitochondrial FAO [71]. In the case of high-fructose exposure, PPARα downregulates, and the expression of CPT1A decreases accordingly. Unoxidized fatty acids then accumulate in renal cells, leading to lipid accumulation in the kidney [72]. The lipotoxicity caused by massive lipid accumulation further triggers renal cell inflammation, oxidative stress and apoptosis, thereby promoting the renal injury [10]. Therefore, FAO inhibition is an important mechanism underlying high fructose-induced renal injury. In this study, ORO staining demonstrated severe lipid accumulation in the kidneys of FRU. The results of the renal TG level test in FRU corresponded with the ORO staining findings. Compared with CON, the PPARα and CPT1A expressions were reduced in FRU, which can be used to explain the phenomenon observed by ORO staining. In FRU + MLT, the PPARα and CPT1A expressions were marked increased and renal lipid accumulation was significantly improved. The FAO process mediated by PPARα is directly regulated by AMPK in the kidney [73]. Therefore, MLT might exert a regulatory effect on FAO by regulating AMPK, thereby alleviating renal lipid accumulation and ultimately improving renal injury.

There were some limitations in this study. Firstly, this study was conducted solely in male mice and without a positive control group. Although the exclusive use of male animals was made to minimize physiological variability associated with the estrous cycle in females, it precludes any assessment of sex-dependent effects. The lack of a positive control group limits our ability to benchmark the efficacy of our intervention against established therapies. While the findings demonstrated the protective effect of MLT on high-fructose-induced renal injury in male mice, their applicability to females and their relative therapeutic potency require validation in more comprehensive future studies. Secondly, a high-concentration fructose solution (30%) was selected in this study to ensure robust and reproducible induction of renal injury within a controlled period. Although this approach is well-established and instrumental for mechanistic investigation, it is much higher than the fructose consumption level in human daily life. Future translational studies using fructose levels related to human consumption can bridge this gap. Thirdly, the absence of creatinine clearance, albuminuria, and highly specific protein markers for renal tubular injury limits the ability of this study to precisely quantify functional decline and delineate the primary site of renal injury. Nevertheless, the concordance of the static serum biomarkers (Cre, BUN, UA) with histopathological alterations observed in H&E staining, ORO staining, and TEM provides compelling evidence for renal injury and the protective effect of MLT. Fourthly, this study has a mechanistic limitation. In the FRU + MLT of this study, the observed improvement of mitophagy and FAO was highly consistent with the activation of AMPK, which aligns with the well-established role of AMPK as a master regulator of these processes. Given the extensive in vitro studies confirming MLT as a direct AMPK activator, it is a highly plausible mediator. However, a sequential causality from MLT to AMPK activation to downstream effects remains to be fully established. Moreover, the evidence supporting renal mitophagy and FAO mainly relies on a limited set of molecular markers assessed by Western blot (with a sample size of n = 3 per group) rather than functional assays. Future studies with larger sample sizes are warranted to increase statistical power and validate these molecular findings. In addition, employing AMPK-knockout models or specific inhibitors to confirm AMPK as the key upstream mediator. Subsequently, direct functional assays—such as measurements of mitophagic flux and mitochondrial FAO rates—will be essential to establish a definitive causal link between AMPK activation, downstream molecular adaptations, and the observed renoprotective phenotype.

The antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, immune regulatory, and potential anti-tumor effects of MLT make it of great value in disease prevention and adjuvant therapy. Nowadays, MLT has been applied in various human disease models and preliminary evidence has been obtained. For instance, a double-blind randomized trial showed that 3 mg/day MLT administered as a 3-month adjunctive therapy for mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis was safe, potentially alleviating symptoms and improving quality of life [74]. A 12-week clinical trial demonstrated that a daily dose of 6 mg MLT improved anthropometric indices, liver enzymes, and inflammatory markers in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [75]. Another trial designed for patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction administered 10 mg/day MLT for 24 weeks to translate preclinical benefits while monitoring safety, and the results of this unique clinical trial might confirm MLT’s role as an adjunctive therapy not only for the primary disease, but also for the common comorbidities and complications of HF, along with patients’ overall health status [76]. MLT has also been exploratively applied in human renal disease models. It is found that 3 mg twice-daily MLT reduced acute kidney injury incidence in critically ill patients with vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity [77]. Furthermore, a dose of 3 mg/day MLT (24 h pre-transplant to discharge) protected kidney transplant patients from ischemia–reperfusion injury [78]. In this study, we administered MLT at a dose of 10 mg/kg via oral gavage and observed its preventive effect on high-fructose-induced renal injury in mice. Although it is not feasible to directly convert this dose to humans, such preclinical research holds significant scientific value, as it provides essential mechanistic evidence supporting the potential renal protective role of MLT. Future studies may build upon the findings of this study to further explore a safe and effective dosage suitable for human application, thereby promoting the translation of melatonin from fundamental evidence to clinical practice.

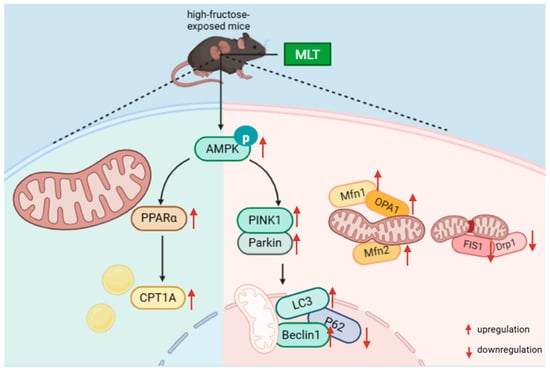

5. Conclusions

MLT alleviates high-fructose-induced renal injury in male mice, which might be associated with the regulation of mitophagy and FAO (Figure 8). In the future, by integrating fundamental research with clinical evidence to optimize dosing strategies and systematically elucidate its renoprotective mechanisms, MLT holds promise as an important adjuvant in renal injury management.

Figure 8.

Potential alleviation mechanisms of MLT on high-fructose-induced renal injury in male mice.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nu18010068/s1, Table S1: Composition and energy of the study diets.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z. and Y.M.; methodology, Y.M.; validation, D.S.; formal analysis, Y.B.; investigation, W.L. and X.B.; data curation, Z.L. and T.K.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.M.; writing—review and editing, H.Z.; supervision, P.W., Z.Z. and H.L.; funding acquisition, P.W., H.Z., H.L. and X.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Financial support for this research was provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81803220), Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. ZR2025MS1478), Qingdao Municipal Natural Science Foundation (No. 24-4-4-zrjj-161-jch), and Key Technology Breakthrough and Industrialization Demonstration Projects in Qingdao (25-1-1-gjgg-71-nsh).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Experimental Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee of Qingdao University (Approval No. 20231102C574020240113054; Approval Date: 23 September 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed in the current study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data availability is restricted in accordance with laboratory policies and confidentiality agreements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| ATP | adenosine triphosphate |

| BUN | urea nitrogen |

| CAT | catalase |

| CON | control |

| CPT1A | carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A |

| Cre | creatinine |

| Drp1 | dynamin-related protein 1 |

| FAO | fatty acid oxidation |

| FIS1 | fission mitochondrial |

| FRU | fructose |

| GSH-Px | glutathione peroxidase |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and Eosin |

| KIM-1 | kidney injury molecule-1 |

| LC3 | Microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 |

| MDA | malonaldehyde |

| MLT | melatonin |

| Mfn1 | mitofusin1 |

| Mfn2 | mitofusin2 |

| mtDNA | mitochondrial DNA |

| OPA1 | optic atrophy 1 |

| ORO | Oil Red O |

| PINK1 | PTEN-induced kinase 1 |

| PPARα | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha |

| P62 | Sequestosome-1 |

| P-AMPK | phosphorylated AMP-activated protein kinase |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase |

| TC | total cholesterol |

| TEM | transmission electron microscope |

| TG | triglyceride |

| TOM20 | translocase of the outer membrane 20 |

| UA | uric acid |

References

- Herman, M.A.; Birnbaum, M.J. Molecular aspects of fructose metabolism and metabolic disease. Cell Metab. 2021, 33, 2329–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Febbraio, M.A.; Karin, M. “Sweet death”: Fructose as a metabolic toxin that targets the gut-liver axis. Cell Metab. 2021, 33, 2316–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, S.; Bae, H.; Song, W.S.; Jang, C. Dietary Fructose and Fructose-Induced Pathologies. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2022, 42, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cargnin-Carvalho, A.; de Mello, A.H.; Bressan, J.B.; Backes, K.M.; Uberti, M.F.; Fogaça, J.B.; da Rosa Turatti, C.; Cavalheiro, E.; Vilela, T.C.; Rezin, G.T. Can fructose influence the development of obesity mediated through hypothalamic alterations? J. Neurosci. Res. 2020, 98, 1662–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi-Sahlabadi, A.; Teymoori, F.; Ahmadirad, H.; Mokhtari, E.; Azadi, M.; Seraj, S.S.; Hekmatdoost, A. Nutrient patterns and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Iranian Adul: A case-control study. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 977403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellwig, M.; Diel, P.; Eisenbrand, G.; Grune, T.; Guth, S.; Henle, T.; Humpf, H.U.; Joost, H.G.; Marko, D.; Raupbach, J.; et al. Dietary glycation compounds—Implications for human health. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2024, 54, 485–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawiasa, A.; Nowicki, M. Acute effects of fructose consumption on uric acid and plasma lipids in patients with impaired renal function. Metabolism 2013, 62, 1462–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.W.; Li, M.X.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Yu, H. The deficiency of CX3CL1/CX3CR1 system ameliorates high fructose diet-induced kidney injury by regulating NF-κB pathways in CX3CR1-knock out mice. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 41, 3577–3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Song, Y.; Chen, L.; Chen, P.; Yuan, M.; Meng, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, G.; Qiu, Z. Urolithin A Attenuates Hyperuricemic Nephropathy in Fructose-Fed Mice by Impairing STING-NLRP3 Axis-Mediated Inflammatory Response via Restoration of Parkin-Dependent Mitophagy. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 907209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Qiu, L.; Wang, F. 18α-Glycyrrhetinic acid (GA) ameliorates fructose-induced nephropathy in mice by suppressing oxidative stress, dyslipidemia and inflammation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 125, 109702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Kang, H.J.; Lee, Y.K.; Kang, H.; Kim, J.; Chung, J.H.; Chang, J.S.; McPherron, A.C.; Lee, S.B. Inactivation of EWS reduces PGC-1α protein stability and mitochondrial homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 6074–6079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rodríguez, M.; García-Verdugo, A.; Sánchez-Mendoza, L.M.; Muñoz-Martín, A.; Bolaños, N.; Pérez-Sánchez, C.; Moreno, J.A.; Burón, M.I.; de Cabo, R.; González-Reyes, J.A.; et al. Cytochrome b(5) reductase 3 overexpression and dietary nicotinamide riboside supplementation promote distinctive mitochondrial alterations in distal convoluted tubules of mouse kidneys during aging. Aging Cell 2024, 23, e14273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nargesi, A.A.; Zhang, L.; Tang, H.; Jordan, K.L.; Saadiq, I.M.; Textor, S.C.; Lerman, L.O.; Eirin, A. Coexisting renal artery stenosis and metabolic syndrome magnifies mitochondrial damage, aggravating poststenotic kidney injury in pigs. J. Hypertens. 2019, 37, 2061–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Lozada, L.G.; Madero, M.; Mazzali, M.; Feig, D.I.; Nakagawa, T.; Lanaspa, M.A.; Kanbay, M.; Kuwabara, M.; Rodriguez-Iturbe, B.; Johnson, R.J. Sugar, salt, immunity and the cause of primary hypertension. Clin. Kidney J. 2023, 16, 1239–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Luo, T.; Yang, Y.; Yang, L.; Liu, M.; Zou, Q.; Wang, D.; Yang, C.; Xue, Q.; Liu, S.; et al. TRPA1 protects against contrast-induced renal tubular injury by preserving mitochondrial dynamics via the AMPK/DRP1 pathway. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 224, 521–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Cai, J.; Wu, P.; Wang, D.; Shi, Y.; Huyan, T.; Su, J.; Li, X.; Wang, Q.; et al. Emodin prevents renal ischemia-reperfusion injury via suppression of CAMKII/DRP1-mediated mitochondrial fission. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 916, 174603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, R.T.; Peng, J.B.; Huang, L.L.; Jiang, G.P.; Liao, Y.J.; Sun, H.; Hu, Y.D.; Liao, X.H. Augmenter of Liver Regeneration Alleviates Renal Hypoxia-Reoxygenation Injury by Regulating Mitochondrial Dynamics in Renal Tubular Epithelial Cells. Mol. Cells 2019, 42, 893–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D.; Alavi, M.V.; Kim, K.Y.; Kang, T.; Scott, R.T.; Noh, Y.H.; Lindsey, J.D.; Wissinger, B.; Ellisman, M.H.; Weinreb, R.N.; et al. A new vicious cycle involving glutamate excitotoxicity, oxidative stress and mitochondrial dynamics. Cell Death Dis. 2011, 2, e240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, Z.; Xing, D. Mitochondrial oxidative stress causes mitochondrial fragmentation via differential modulation of mitochondrial fission-fusion proteins. FEBS J. 2011, 278, 941–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, P.; Tan, J.; Miao, Y.; Zhang, Q. PINK1/Parkin-Mediated Mitophagy Plays a Protective Role in Albumin Overload-Induced Renal Tubular Cell Injury. Front. Biosci. 2022, 27, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Livingston, M.J.; Liu, Z.; Dong, Z. Autophagy in kidney homeostasis and disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2020, 16, 489–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.; Han, H.; Yan, M.; Zhu, S.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z.; He, L.; Tan, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; et al. PINK1-PRKN/PARK2 pathway of mitophagy is activated to protect against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Autophagy 2018, 14, 880–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Ying, X.; Wu, Z.; Zeng, W.; Miao, C.; Nan, Y.; Huang, Q.; Ai, K. Fully Biocompatible Tantalum-Based Antioxidant Nanoshields for Proximal Tubule Epithelial Cells-Targeted Mitochondrial Holistic Protection in Acute Kidney Injury. Adv. Mater. 2025, e06307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munusamy, S.; Saba, H.; Mitchell, T.; Megyesi, J.K.; Brock, R.W.; Macmillan-Crow, L.A. Alteration of renal respiratory Complex-III during experimental type-1 diabetes. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2009, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, L.; Jin, B.; Wu, Y.; Xu, L.; Chang, X.; Hu, L.; Wang, G.; Huang, Y.; Song, L.; et al. Metrnl Alleviates Lipid Accumulation by Modulating Mitochondrial Homeostasis in Diabetic Nephropathy. Diabetes 2023, 72, 611–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Liu, C.; Chang, D.Y.; Zhan, R.; Zhao, M.; Man Lam, S.; Shui, G.; Zhao, M.H.; Zheng, L.; Chen, M. The Attenuation of Diabetic Nephropathy by Annexin A1 via Regulation of Lipid Metabolism Through the AMPK/PPARα/CPT1b Pathway. Diabetes 2021, 70, 2192–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Xu, L.; Ma, Y.; Kohzuki, M.; Ito, O. Chronic exercise provides renal-protective effects with upregulation of fatty acid oxidation in the kidney of high fructose-fed rats. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2020, 318, F826–F834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Qiao, P.; Ying, Y.; Lin, S.; Lu, F.; Gao, C.; Li, M.; Yang, B.; Zhou, H. Mechanisms of Cisplatin-Induced Acute Kidney Injury: The Role of NRF2 in Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Metabolic Reprogramming. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, V.; Tituaña, J.; Herrero, J.I.; Herrero, L.; Serra, D.; Cuevas, P.; Barbas, C.; Puyol, D.R.; Márquez-Expósito, L.; Ruiz-Ortega, M.; et al. Renal tubule Cpt1a overexpression protects from kidney fibrosis by restoring mitochondrial homeostasis. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e140695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, A.M.; Reiter, R.J.; Nonaka, K.O.; Mostafa, M.H.; Soliman, S.A.; el-Sebae, A.H. Carbaryl-induced changes in indoleamine synthesis in the pineal gland and its effects on nighttime serum melatonin concentrations. Toxicology 1991, 65, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuraikat, F.M.; Wood, R.A.; Barragán, R.; St-Onge, M.P. Sleep and Diet: Mounting Evidence of a Cyclical Relationship. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2021, 41, 309–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpino, F.M.; Figueiredo, L.M.; Nunes, B.P. Effects of melatonin supplementation on diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 4595–4605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Qin, X.; Turdi, S.; Sun, D.; Culver, B.; Reiter, R.J.; Wang, X.; Zhou, H.; Ren, J. ALDH2 contributes to melatonin-induced protection against APP/PS1 mutation-prompted cardiac anomalies through cGAS-STING-TBK1-mediated regulation of mitophagy. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2020, 5, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jauhari, A.; Baranov, S.V.; Suofu, Y.; Kim, J.; Singh, T.; Yablonska, S.; Li, F.; Wang, X.; Oberly, P.; Minnigh, M.B.; et al. Melatonin inhibits cytosolic mitochondrial DNA-induced neuroinflammatory signaling in accelerated aging and neurodegeneration. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 3124–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, B.C.; van der Putten, K.; Van Someren, E.J.; Wielders, J.P.; Ter Wee, P.M.; Nagtegaal, J.E.; Gaillard, C.A. Impairment of endogenous melatonin rhythm is related to the degree of chronic kidney disease (CREAM study). Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2010, 25, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Huang, W.; Sun, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, R.; Liu, F.; Huang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, F.; Wang, B. Melatonin attenuates cellular senescence and apoptosis in diabetic nephropathy by regulating STAT3 phosphorylation. Life Sci. 2023, 332, 122108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, S.U.; Ikram, M.; Ullah, N.; Alam, S.I.; Park, H.Y.; Badshah, H.; Choe, K.; Kim, M.O. Neurological Enhancement Effects of Melatonin against Brain Injury-Induced Oxidative Stress, Neuroinflammation, and Neurodegeneration via AMPK/CREB Signaling. Cells 2019, 8, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Hao, H.; Gao, X.; Cai, Y.; Zhou, J.; Liang, P.; Lv, J.; He, Q.; Shi, C.; Hu, D.; et al. Melatonin ameliorates necrotizing enterocolitis by preventing Th17/Treg imbalance through activation of the AMPK/SIRT1 pathway. Theranostics 2020, 10, 7730–7746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Sun, Q.; Qiu, H.; Yang, K.; Xiao, B.; Xia, T.; Wang, A.; Gao, H.; Zhang, S. Melatonin protects against developmental PBDE-47 neurotoxicity by targeting the AMPK/mitophagy axis. J. Pineal. Res. 2023, 75, e12871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.S.; Zhang, S.F.; Luo, G.; Cheng, B.C.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.W.; Qiu, X.Y.; Zhou, X.H.; Wang, Q.G.; Song, X.L.; et al. Schisandrin B mitigates hepatic steatosis and promotes fatty acid oxidation by inducing autophagy through AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway. Metabolism 2022, 131, 155200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zou, D.; Tang, S.; Fan, T.; Su, H.; Hu, R.; Zhou, Q.; Gui, S.; Zuo, L.; Wang, Y. Ameliorative effect of melatonin against increased intestinal permeability in diabetic rats: Possible involvement of MLCK-dependent MLC phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2016, 416, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, X.Q.; Jian, T.Y.; Gai, Y.N.; Niu, G.T.; Liu, Y.; Meng, X.H.; Li, J.; Lyu, H.; Ren, B.R.; Chen, J. Chicoric Acid Attenuated Renal Tubular Injury in HFD-Induced Chronic Kidney Disease Mice through the Promotion of Mitophagy via the Nrf2/PINK/Parkin Pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 2923–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeChristopher, L.R.; Tucker, K.L. Disproportionately higher asthma risk and incidence with high fructose corn syrup, but not sucrose intake, among Black young adults: The CARDIA Study. Public Health Nutr. 2025, 28, e92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeChristopher, L.R.; Uribarri, J.; Tucker, K.L. Intakes of apple juice, fruit drinks and soda are associated with prevalent asthma in US children aged 2-9 years. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siqueira, J.H.; Mill, J.G.; Velasquez-Melendez, G.; Moreira, A.D.; Barreto, S.M.; Benseñor, I.M.; Molina, M. Sugar-Sweetened Soft Drinks and Fructose Consumption Are Associated with Hyperuricemia: Cross-Sectional Analysis from the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil). Nutrients 2018, 10, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragno, M.; Mastrocola, R. Dietary Sugars and Endogenous Formation of Advanced Glycation Endproducts: Emerging Mechanisms of Disease. Nutrients 2017, 9, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, A.V.; Mosser, E.A.; Oikonomou, G.; Prober, D.A. Melatonin is required for the circadian regulation of sleep. Neuron 2015, 85, 1193–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Zhou, Y.; Gan, R.Y.; Xu, D.P.; Li, H.B. Dietary Sources and Bioactivities of Melatonin. Nutrients 2017, 9, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liang, C.; Yao, S.; Wang, F. Melatonin Exerts Positive Effects on Sepsis Through Various Beneficial Mechanisms. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2025, 19, 1333–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palagini, L.; Manni, R.; Aguglia, E.; Amore, M.; Brugnoli, R.; Bioulac, S.; Bourgin, P.; Micoulaud Franchi, J.A.; Girardi, P.; Grassi, L.; et al. International Expert Opinions and Recommendations on the Use of Melatonin in the Treatment of Insomnia and Circadian Sleep Disturbances in Adult Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 688890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Ma, Y.; Bai, Y.; Bai, X.; Liu, W.; Du, L.; Wang, P.; Liang, X.; Liang, H.; Zhang, H. Folic Acid Combined with Melatonin Might Prevent Hepatic Steatosis by Alleviating Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress to Promote Lipid Droplet Lipolysis in High-Fat Diet-Fed Mice. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kose, O.; Kurt Bayrakdar, S.; Unver, B.; Altin, A.; Akyildiz, K.; Mercantepe, T.; Bostan, S.A.; Arabaci, T.; Turker Sener, L.; Emre Kose, T.; et al. Melatonin improves periodontitis-induced kidney damage by decreasing inflammatory stress and apoptosis in rats. J. Periodontol. 2021, 92, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Liu, J.; Li, H.; Yan, Y. Melatonin attenuates ischemia-reperfusion-induced acute kidney injury by regulating abnormal autophagy and pyroptosis through SIRT1-mediated p53 deacetylation. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 162, 115092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Agaty, S.M.; Khedr, S.; Mostafa, D.K.M.; Wanis, N.A.; Abou-Bakr, D.A. Protective role of melatonin against diclofenac-induced acute kidney injury. Life Sci. 2024, 353, 122936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Ledo, A.; Luxán-Delgado, B.; Caballero, B.; Potes, Y.; Rodríguez-González, S.; Boga, J.A.; Coto-Montes, A.; García-Macia, M. Melatonin Ameliorates Autophagy Impairment in a Metabolic Syndrome Model. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Li, H.; Zhang, O.; Zhang, F.; Song, M.; Ma, M.; Zhao, Y.; Ding, R.; Li, D.; Dong, Z.; et al. Melatonin alleviates diet-induced steatohepatitis by targeting multiple cell types in the liver to suppress inflammation and fibrosis. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2023, 70, e220075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Upadhyay, K.K.; Vohra, A.; Shirsath, K.; Devkar, R. Melatonin induces Nrf2-HO-1 reprogramming and corrections in hepatic core clock oscillations in Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. FASEB J. 2021, 35, e21803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, L.; Wei, G.; Peng, S.; Qu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Huang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhuang, Z.; Yang, X. Melatonin ameliorates anxiety and depression-like behaviors and modulates proteomic changes in triple transgenic mice of Alzheimer’s disease. Biofactors 2017, 43, 593–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Lu, X.; Hu, Y.; Yang, B.; Tsui, C.K.; Yu, S.; Lu, L.; Liang, X. Melatonin attenuated retinal neovascularization and neuroglial dysfunction by inhibition of HIF-1α-VEGF pathway in oxygen-induced retinopathy mice. J. Pineal Res. 2018, 64, e12473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; He, Y.; Ma, Q.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Q. Alleviative effect of melatonin against the nephrotoxicity induced by cadmium exposure through regulating renal oxidative stress, inflammatory reaction, and fibrosis in a mouse model. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 265, 115536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaki, F.; Ashari, S.; Ahangar, N. Melatonin can attenuate ciprofloxacin induced nephrotoxicity: Involvement of nitric oxide and TNF-α. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 84, 1172–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhuang, W.R.; Zhao, H.; Nie, W.; Wu, G.; Pang, D.W.; Xie, H.Y. NAD(+) biosynthesis and mitochondrial repair in acute kidney injury via ultrasound-responsive thylakoid-integrating liposomes. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2025, 9, 1740–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, N.; Ding, X. Empagliflozin, a sodium-glucose cotransporter inhibitor enhancing mitochondrial action and cardioprotection in metabolic syndrome. J. Cell. Physiol. 2024, 239, e31264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, S.; Wang, C.; Yuan, Y.; Yang, G.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, J.; Lu, Y.; et al. Mitochondrial ROS promote mitochondrial dysfunction and inflammation in ischemic acute kidney injury by disrupting TFAM-mediated mtDNA maintenance. Theranostics 2021, 11, 1845–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glauser, J.S.O.; Santana-Oliveira, D.A.; Silva-Veiga, F.M.; Fernandes-da-Silva, A.; Aguila, M.B.; Souza-Mello, V. Excessive dietary saturated fat or fructose and their combination (found in ultra-processed foods) impair mitochondrial dynamics markers and cause brown adipocyte whitening in adult mice. Nutrition 2025, 137, 112805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddhi, J.; Sherkhane, B.; Kalavala, A.K.; Arruri, V.; Velayutham, R.; Kumar, A. Melatonin prevents diabetes-induced nephropathy by modulating the AMPK/SIRT1 axis: Focus on autophagy and mitochondrial dysfunction. Cell Biol. Int. 2022, 46, 2142–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.C.; Tang, S.Q.; Liu, Y.T.; Li, A.M.; Zhan, M.; Yang, M.; Song, N.; Zhang, W.; Wu, X.Q.; Peng, C.H.; et al. AMPK agonist alleviate renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis via activating mitophagy in high fat and streptozotocin induced diabetic mice. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.H.; Lee, D.B.; Yoon, D.W.; Kim, J. Melatonin Improves Glucose Homeostasis and Insulin Sensitivity by Mitigating Inflammation and Activating AMPK Signaling in a Mouse Model of Sleep Fragmentation. Cells 2024, 13, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; He, Z.; Li, B.; Liu, J.; Liu, L.; Liao, W.; Xiong, Y.; Song, C.; Yang, S.; Liu, Y. Melatonin inhibits oxalate-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis in HK-2 cells by activating the AMPK pathway. Cell Cycle 2020, 19, 2600–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.H.; Zhang, X.; Pan, Y.; Li, Y.C.; Kong, L.D. Corrigendum to “Allopurinol, quercetin and rutin ameliorate renal NLRP3 inflammasome activation and lipid accumulation in fructose-fed rats”. [Biochem. Pharmacol. 84(1) (2012) 113-125]. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2022, 198, 114971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Zhan, H.; Yuan, H.; Wang, N.; Lan, Y.; Qu, W.; Lan, X.; Liao, Z.; Wang, G.; Chen, M. Boeravinone C ameliorates lipid accumulation and inflammation in diabetic kidney disease by activating PPARα signaling. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 342, 119398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.Y.; Wang, M.X.; Ge, C.X.; Wang, X.; Li, J.M.; Kong, L.D. Betaine supplementation protects against high-fructose-induced renal injury in rats. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2014, 25, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Lim, J.H.; Kim, M.Y.; Kim, E.N.; Yoon, H.E.; Shin, S.J.; Choi, B.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Chang, Y.S.; Park, C.W. The Adiponectin Receptor Agonist AdipoRon Ameliorates Diabetic Nephropathy in a Model of Type 2 Diabetes. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 29, 1108–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrokh, S.; Qobadighadikolaei, R.; Abbasinazari, M.; Haghazali, M.; Asadzadeh Aghdaei, H.; Abdi, S.; Balaii, H.; Khanzadeh-Moghaddam, N.; Zali, M.R. Efficacy and Safety of Melatonin as an Adjunctive Therapy on Clinical, Biochemical, and Quality of Life in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2021, 20, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, M.; Cheraghpour, M.; Jafarirad, S.; Alavinejad, P.; Asadi, F.; Hekmatdoost, A.; Mohammadi, M.; Yari, Z. The effect of melatonin on treatment of patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized double blind clinical trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 52, 102452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M.; Khosrawi, S.; Heshmat-Ghahdarijani, K.; Gheisari, Y.; Roohafza, H.; Mansoorian, M.; Hoseini, S.G. Effect of melatonin on heart failure: Design for a double-blinded randomized clinical trial. ESC Heart Fail. 2020, 7, 3142–3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.; Bigharaz, E.; Farsaei, S.; Mansourian, M. Could melatonin prevent Vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity in critically ill patients? A randomized, double-blinded controlled trial. Casp. J. Intern. Med. 2023, 14, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panah, F.; Ghorbanihaghjo, A.; Argani, H.; Haiaty, S.; Rashtchizadeh, N.; Hosseini, L.; Dastmalchi, S.; Rezaeian, R.; Alirezaei, A.; Jabarpour, M.; et al. The effect of oral melatonin on renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in transplant patients: A double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Transpl. Immunol. 2019, 57, 101241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.