Polyphenols and Eye Health: A Narrative Review of the Literature on the Therapeutic Effects for Ocular Diseases

Abstract

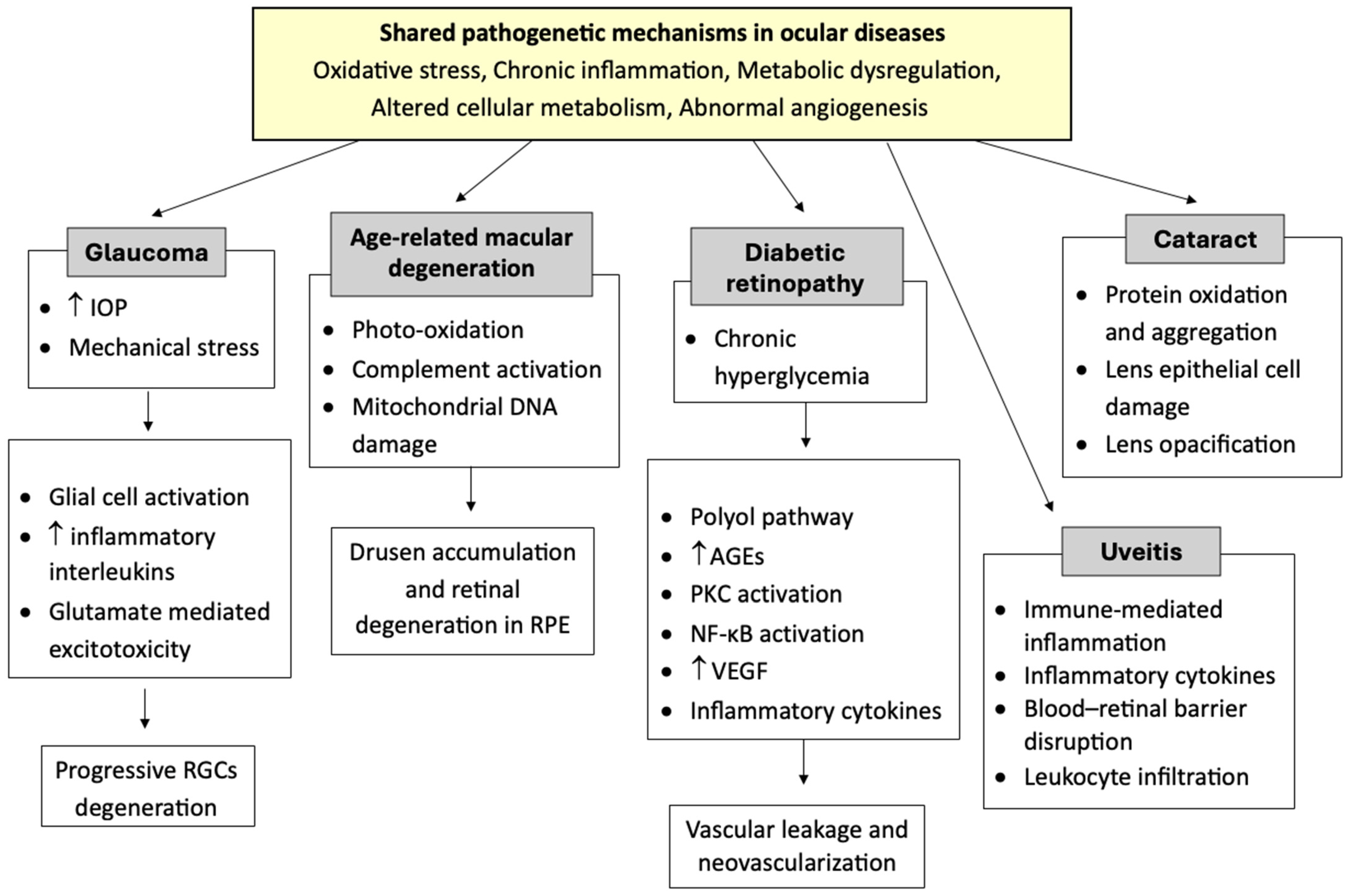

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Anthocyanins

4. Baicalin

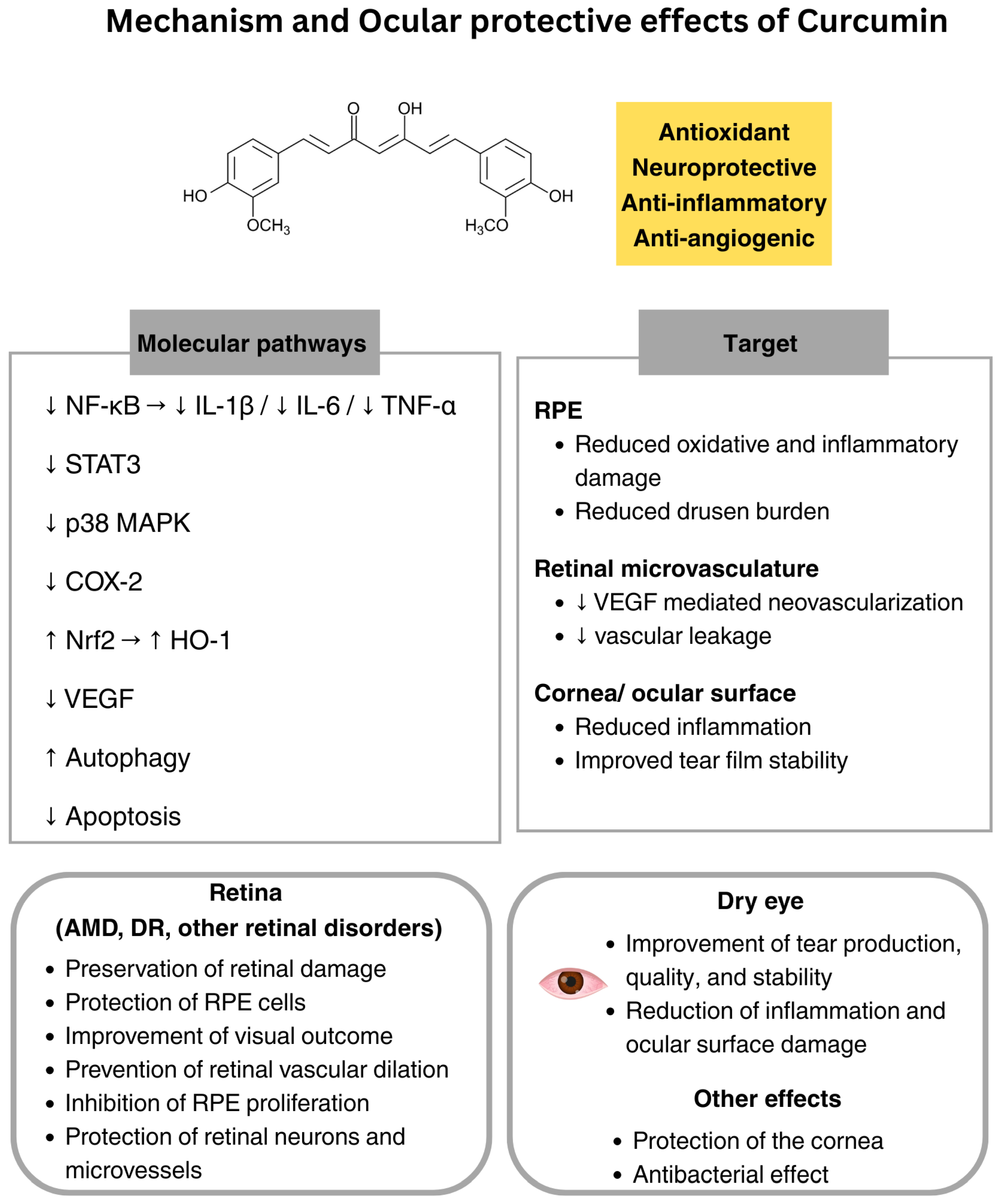

5. Curcumin

6. Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate

7. Ferulic Acid

8. Quercetin

9. Resveratrol

10. Discussion

11. Safety Considerations

12. Limitations

13. Future Directions

14. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Akt | Protein kinase B |

| AMD | Age-related macular degeneration |

| CBNS | Curcuma-based nutritional supplements |

| DR | Diabetic retinopathy |

| EGCG | Epigallocatechin-3-gallate |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α |

| HO-1 | Heme oxygenase-1 |

| ICAM-1 | Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IOP | Intraocular pressure |

| Keap1 | Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 |

| MAPKs | Mitogen-activated protein kinases |

| MMP-2 | Matrix metalloproteinase-2 |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NLRP3 | Nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich repeat, and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| PDGF | Platelet-derived growth factor |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase |

| PPARγ | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma |

| RGC | Retinal ganglion cell |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RPE | Retinal pigment epithelium |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor α |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

- United Nations General Assembly. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly; United Nations General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.H.; Ramke, J.; Mwangi, N.; Furtado, J.; Yasmin, S.; Bascaran, C.; Ogundo, C.; Jan, C.; Gordon, I.; Congdon, N.; et al. Global eye health and the sustainable development goals: Protocol for a scoping review. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e035789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terheyden, J.H.; Finger, R.P. Vision-related Quality of Life with Low Vision—Assessment and Instruments. Klin. Monbl Augenheilkd. 2019, 236, 261–268. [Google Scholar]

- VanNasdale, D.A.; Jones-Jordan, L.A.; Hurley, M.S.; Shelton, E.R.; Robich, M.L.; Crews, J.E. Association between Vision Impairment and Physical Quality of Life Assessed Using National Surveillance Data. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2021, 98, 1063–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno-Matsui, K.; Kawasaki, R.; Jonas, J.B.; Cheung, C.M.; Saw, S.M.; Verhoeven, V.J.; Klaver, C.C.; Moriyama, M.; Shinohara, K.; Kawasaki, Y.; et al. International photographic classification and grading system for myopic maculopathy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2015, 159, 877–883 e877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmamula, S.; Barrenakala, N.R.; Challa, R.; Kumbham, T.R.; Modepalli, S.B.; Yellapragada, R.; Bhakki, M.; Khanna, R.C.; Friedman, D.S. Prevalence and risk factors for visual impairment among elderly residents in ‘homes for the aged’ in India: The Hyderabad Ocular Morbidity in Elderly Study (HOMES). Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 105, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Zhao, G.L.; Cheng, S.; Wang, Z.; Yang, X.L. Activation of retinal glial cells contributes to the degeneration of ganglion cells in experimental glaucoma. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2023, 93, 101169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Bermúdez, M.Y.; Freude, K.K.; Mouhammad, Z.A.; van Wijngaarden, P.; Martin, K.K.; Kolko, M. Glial Cells in Glaucoma: Friends, Foes, and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 624983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgescu, A.; Dascalu, A.M.; Stana, D.; Alexandrescu, C.; Bobirca, A.; Cristea, B.M.; Vancea, G.; Serboiu, C.S.; Serban, D.; Tudor, C.; et al. The Role of Inflammation in Diabetic Retinopathy in Patients with Type II Diabetes; Potential Therapeutic Perspectives. J. Mind Med. Sci. 2024, 11, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrington, D.A.; Ebeling, M.C.; Kapphahn, R.J.; Terluk, M.R.; Fisher, C.R.; Polanco, J.R.; Roehrich, H.; Leary, M.M.; Geng, Z.; Dutton, J.R.; et al. Altered bioenergetics and enhanced resistance to oxidative stress in human retinal pigment epithelial cells from donors with age-related macular degeneration. Redox Biol. 2017, 13, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaarniranta, K.; Uusitalo, H.; Blasiak, J.; Felszeghy, S.; Kannan, R.; Kauppinen, A.; Salminen, A.; Sinha, D.; Ferrington, D. Mechanisms of mitochondrial dysfunction and their impact on age-related macular degeneration. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2020, 79, 100858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, A.; Lixi, F.; Vitiello, L.; Gagliardi, V.; Pellegrino, A.; Giannaccare, G. The Role of Diet and Oral Supplementation for the Management of Diabetic Retinopathy and Diabetic Macular Edema. A Narrative Review. Biomed. Res. Int. 2025, 2025, 6654976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Angelo, A.; Vitiello, L.; Gagliardi, V.; Salerno, G.; De Pascale, I.; Coppola, A.; Abbinante, G.; Pellegrino, A.; Giannaccare, G. The Role of Oral Supplementation for the Management of Age-Related Macular Degeneration. A Narrative Review. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, A.; Vitiello, L.; Lixi, F.; Abbinante, G.; Coppola, A.; Gagliardi, V.; Pellegrino, A.; Giannaccare, G. Optic Nerve Neuroprotection in Glaucoma: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibuki, M.; Lee, D.; Shinojima, A.; Miwa, Y.; Tsubota, K.; Kurihara, T. Rice Bran and Vitamin B6 Suppress Pathological Neovascularization in a Murine Model of Age-Related Macular Degeneration as Novel HIF Inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.C.; Singh, S.; Craig, J.P.; Downie, L.E. Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Eye Health: Opinions and Self-Reported Practice Behaviors of Optometrists in Australia and New Zealand. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrenson, J.G.; Downie, L.E. Nutrition and Eye Health. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiuolo, J.; Bulotta, R.M.; Oppedisano, F.; Bosco, F.; Scarano, F.; Nucera, S.; Guarnieri, L.; Ruga, S.; Macri, R.; Caminiti, R.; et al. Potential Properties of Natural Nutraceuticals and Antioxidants in Age-Related Eye Disorders. Life 2022, 13, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.L.; Wang, Y.X.; Lin, Z.Y.; Ren, W.S.; Liu, B.; Zhao, H.; Qin, Q. Regulatory factors of Nrf2 in age-related macular degeneration pathogenesis. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 17, 1344–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, L.; Joo, D.; Sun, S.C. NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2017, 2, 17023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, K.; Akhtar-Schaefer, I.; Langmann, T. Microglia in Retinal Degeneration. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carregosa, D.; Mota, S.; Ferreira, S.; Alves-Dias, B.; Loncarevic-Vasiljkovic, N.; Crespo, C.L.; Menezes, R.; Teodoro, R.; Santos, C.N.D. Overview of Beneficial Effects of (Poly)phenol Metabolites in the Context of Neurodegenerative Diseases on Model Organisms. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayusman, P.A.; Nasruddin, N.S.; Mahamad Apandi, N.I.; Ibrahim, N.; Budin, S.B. Therapeutic Potential of Polyphenol and Nanoparticles Mediated Delivery in Periodontal Inflammation: A Review of Current Trends and Future Perspectives. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 847702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Qi, Y.; Zheng, H. Dietary Polyphenol, Gut Microbiota, and Health Benefits. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsao, R. Chemistry and biochemistry of dietary polyphenols. Nutrients 2010, 2, 1231–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciupei, D.; Colisar, A.; Leopold, L.; Stanila, A.; Diaconeasa, Z.M. Polyphenols: From Classification to Therapeutic Potential and Bioavailability. Foods 2024, 13, 4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalbert, A.; Johnson, I.T.; Saltmarsh, M. Polyphenols: Antioxidants and beyond. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 215S–217S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Wang, H.; Du, X. The therapeutic use of quercetin in ophthalmology: Recent applications. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 137, 111371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, P.P.; Woi, P.J.; Bastion, M.C.; Omar, R.; Mustapha, M.; Md Din, N. Review of Evidence for the Usage of Antioxidants for Eye Aging. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 5810373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellegrini, M.; Senni, C.; Bernabei, F.; Cicero, A.F.G.; Vagge, A.; Maestri, A.; Scorcia, V.; Giannaccare, G. The Role of Nutrition and Nutritional Supplements in Ocular Surface Diseases. Nutrients 2020, 12, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Zhang, Y. The potential benefits of polyphenols for corneal diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 169, 115862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohguro, H.; Ohguro, I.; Katai, M.; Tanaka, S. Two-year randomized, placebo-controlled study of black currant anthocyanins on visual field in glaucoma. Ophthalmologica 2012, 228, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohguro, H.; Ohguro, I.; Yagi, S. Effects of black currant anthocyanins on intraocular pressure in healthy volunteers and patients with glaucoma. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 29, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Ye, Z.; Yang, W.; Xu, Y.J.; Tan, C.P.; Liu, Y. Blueberry Anthocyanins from Commercial Products: Structure Identification and Potential for Diabetic Retinopathy Amelioration. Molecules 2022, 27, 7475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, C.S.; Lee, Y.M.; Sohn, E.; Jo, K.; Kim, J.S. Vaccinium myrtillus extract prevents or delays the onset of diabetes—Induced blood-retinal barrier breakdown. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 66, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizawa, Y.; Sekikawa, T.; Kageyama, M.; Tomobe, H.; Kobashi, R.; Yamada, T. Effects of anthocyanin, astaxanthin, and lutein on eye functions: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2021, 69, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Peng, Y.; Wang, C.L.; Wei, H.X.; Xu, S.Q.; Liu, Y.F.; Yin, X.W.; Bi, H.S.; Guo, D.D. Baicalin prevents experimental autoimmune uveitis by promoting macrophage polarization balance through inhibiting the HIF-1α signaling pathway. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 16424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.H.; Kang, K.D.; Ji, D.; Fawcett, R.J.; Safa, R.; Kamalden, T.A.; Osborne, N.N. The flavonoid baicalin counteracts ischemic and oxidative insults to retinal cells and lipid peroxidation to brain membranes. Neurochem. Int. 2008, 53, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.J.; Jo, H.; Kim, J.G.; Jung, S.H. Baicalin attenuates laser-induced choroidal neovascularization. Curr. Eye Res. 2014, 39, 745–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandal, M.N.; Patlolla, J.M.; Zheng, L.; Agbaga, M.P.; Tran, J.T.; Wicker, L.; Kasus-Jacobi, A.; Elliott, M.H.; Rao, C.V.; Anderson, R.E. Curcumin protects retinal cells from light-and oxidant stress-induced cell death. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009, 46, 672–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielskus, I.; Kakouri, A.; Pfahler, N.M.; Barry, J.L.; Aman, S.; Zaparackas, Z.; Volpe, N.J.; Knepper, P.A. Curcumin acts to regress macular drusen volume in dry AMD. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2020, 61, 1036. [Google Scholar]

- Kowluru, R.A.; Kanwar, M. Effects of curcumin on retinal oxidative stress and inflammation in diabetes. Nutr. Metab. 2007, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, N.; Gerson, J.; Ryan, R.; Barbour, K.; Poteet, J.; Jennings, B.; Sharp, M.; Lowery, R.; Wilson, J.; Morde, A.; et al. A novel multi-ingredient supplement significantly improves ocular symptom severity and tear production in patients with dry eye disease: Results from a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Front. Ophthalmol. 2024, 4, 1362113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, A.; Oliveira, D.; Cabral-Marques, H. Curcumin in Ophthalmology: Mechanisms, Challenges, and Emerging Opportunities. Molecules 2025, 30, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etemadi, S.; Barhaghi, M.H.S.; Leylabadlo, H.E.; Memar, M.Y.; Mohammadi, A.B.; Ghotaslou, R. The synergistic effect of turmeric aqueous extract and chitosan against multidrug-resistant bacteria. New Microbes New Infect. 2021, 41, 100861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, T.; Jin, Y.; Yang, D.; Chen, F. Neuroprotective effects of Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) in optic nerve crush model in rats. Neurosci. Lett. 2010, 479, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasiak, J.; Chojnacki, J.; Szczepanska, J.; Fila, M.; Chojnacki, C.; Kaarniranta, K.; Pawlowska, E. Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate, an Active Green Tea Component to Support Anti-VEGFA Therapy in Wet Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.K.; Liang, S. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate protects retinal vascular endothelial cells from high glucose stress in vitro via the MAPK/ERK-VEGF pathway. Genet. Mol. Res. 2016, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ola, M.S.; Ahmed, M.M.; Shams, S.; Al-Rejaie, S.S. Neuroprotective effects of quercetin in diabetic rat retina. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2017, 24, 1186–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, G.; Yang, B.; Wu, J. Quercetin Enhances Inhibitory Synaptic Inputs and Reduces Excitatory Synaptic Inputs to OFF- and ON-Type Retinal Ganglion Cells in a Chronic Glaucoma Rat Model. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.J.; Zhang, S.H.; Xu, P.; Yang, B.Q.; Zhang, R.; Cheng, Y.; Zhou, X.J.; Huang, W.J.; Wang, M.; Chen, J.Y.; et al. Quercetin Declines Apoptosis, Ameliorates Mitochondrial Function and Improves Retinal Ganglion Cell Survival and Function in In Vivo Model of Glaucoma in Rat and Retinal Ganglion Cell Culture In Vitro. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2017, 10, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, P.; Shen, Y.; Lin, B.Q.; Zhang, W.Y.; Chiou, G.C. Effect of quercetin on formation of choroidal neovascularization (CNV) in age-related macular degeneration(AMD). Eye Sci. 2011, 26, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- King, R.E.; Kent, K.D.; Bomser, J.A. Resveratrol reduces oxidation and proliferation of human retinal pigment epithelial cells via extracellular signal-regulated kinase inhibition. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2005, 151, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soufi, F.G.; Mohammad-Nejad, D.; Ahmadieh, H. Resveratrol improves diabetic retinopathy possibly through oxidative stress—Nuclear factor kappaB—Apoptosis pathway. Pharmacol. Rep. 2012, 64, 1505–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.Z.; Yao, Z.Y.; He, Z.H. Resveratrol protects against high glucose-induced oxidative damage in human lens epithelial cells by activating autophagy. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 21, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Ishida, T.; Fang, Y.; Shinohara, K.; Li, X.; Nagaoka, N.; Ohno-Matsui, K.; Yoshida, T. Protection of the Retinal Ganglion Cells: Intravitreal Injection of Resveratrol in Mouse Model of Ocular Hypertension. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2020, 61, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, S.; Kurihara, T.; Mochimaru, H.; Satofuka, S.; Noda, K.; Ozawa, Y.; Oike, Y.; Ishida, S.; Tsubota, K. Prevention of ocular inflammation in endotoxin-induced uveitis with resveratrol by inhibiting oxidative damage and nuclear factor-kappaB activation. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2009, 50, 3512–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ginkel, P.R.; Darjatmoko, S.R.; Sareen, D.; Subramanian, L.; Bhattacharya, S.; Lindstrom, M.J.; Albert, D.M.; Polans, A.S. Resveratrol inhibits uveal melanoma tumor growth via early mitochondrial dysfunction. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2008, 49, 1299–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, Y.A.; Chen, C.S.; Wang, Y.C.; Lin, E.S.; Chang, C.Y.; Chen, J.J.; Wu, M.Y.; Lin, H.J.; Wan, L. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Resveratrol on Human Retinal Pigment Cells and a Myopia Animal Model. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2021, 43, 716–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abengozar-Vela, A.; Schaumburg, C.S.; Stern, M.E.; Calonge, M.; Enriquez-de-Salamanca, A.; Gonzalez-Garcia, M.J. Topical Quercetin and Resveratrol Protect the Ocular Surface in Experimental Dry Eye Disease. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2019, 27, 1023–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, K.; Jin, B.; Zhu, H.; Zhou, P.; Du, L.; Jin, X. Ferulic acid (FA) protects human retinal pigment epithelial cells from H2O2—Induced oxidative injuries. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 13454–13462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Zou, W.; Cao, X.; Xu, W.; Lu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Hu, X.; Hu, J.; Zhu, Q. Ferulic acid attenuates high glucose-induced apoptosis in retinal pigment epithelium cells and protects retina in db/db mice. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, X.; Zhu, L.; Yan, Y.; Qian, H.; Kang, Z.; Ye, W.; Xie, Z.; Xue, C. Ferulic Acid Protects Human Lens Epithelial Cells Against UVA-Induced Oxidative Damage by Downregulating the DNA Demethylation of the Keap1 Promoter. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2024, 38, e70031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoo, H.E.; Azlan, A.; Tang, S.T.; Lim, S.M. Anthocyanidins and anthocyanins: Colored pigments as food, pharmaceutical ingredients, and the potential health benefits. Food Nutr. Res. 2017, 61, 1361779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, N.; Wang, T.; Gan, Q.; Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Jin, B. Plant flavonoids: Classification, distribution, biosynthesis, and antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 2022, 383, 132531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, C.; Blesso, C.N. Antioxidant properties of anthocyanins and their mechanism of action in atherosclerosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 172, 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.S.; Stoner, G.D. Anthocyanins and their role in cancer prevention. Cancer Lett. 2008, 269, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomi, Y.; Iwasaki-Kurashige, K.; Matsumoto, H. Therapeutic Effects of Anthocyanins for Vision and Eye Health. Molecules 2019, 24, 3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsen, A.; Retterstol, L.; Laake, P.; Paur, I.; Kjolsrud-Bohn, S.; Sandvik, L.; Blomhoff, R. Anthocyanins inhibit nuclear factor-κB activation in monocytes and reduce plasma concentrations of pro-inflammatory mediators in healthy adults. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 1951–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Balandrano, D.D.; Chai, Z.; Beta, T.; Feng, J.; Huang, W.Y. Blueberry anthocyanins: An updated review on approaches to enhancing their bioavailability. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 118, 808–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGhie, T.K.; Walton, M.C. The bioavailability and absorption of anthocyanins: Towards a better understanding. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2007, 51, 702–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, C.D. Aspects of anthocyanin absorption, metabolism and pharmacokinetics in humans. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2006, 19, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.H.; Hwang, I.G.; Lee, Y.M. Effects of anthocyanin supplementation on blood lipid levels: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1207751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, R.H.; Sirasanagandla, S.R.; Das, S.; Teoh, S.L. Treatment of Glaucoma with Natural Products and Their Mechanism of Action: An Update. Nutrients 2022, 14, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shim, S.H.; Kim, J.M.; Choi, C.Y.; Kim, C.Y.; Park, K.H. Ginkgo biloba extract and bilberry anthocyanins improve visual function in patients with normal tension glaucoma. J. Med. Food 2012, 15, 818–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, O.; Moritoh, S.; Sato, K.; Maekawa, S.; Murayama, N.; Himori, N.; Omodaka, K.; Sogon, T.; Nakazawa, T. Bilberry extract administration prevents retinal ganglion cell death in mice via the regulation of chaperone molecules under conditions of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2017, 11, 1825–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khidr, E.G.; Morad, N.I.; Hatem, S.; El-Dessouki, A.M.; Mohamed, A.F.; El-Shiekh, R.A.; Hafeez, M.; Ghaiad, H.R. Natural remedies proposed for the management of diabetic retinopathy (DR): Diabetic complications. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2025, 398, 7919–7947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozlowska, A.; Nitsch-Osuch, A. Anthocyanins and Type 2 Diabetes: An Update of Human Study and Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parravano, M.; Tedeschi, M.; Manca, D.; Costanzo, E.; Di Renzo, A.; Giorno, P.; Barbano, L.; Ziccardi, L.; Varano, M.; Parisi, V. Effects of Macuprev® Supplementation in Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Double-Blind Randomized Morpho-Functional Study Along 6 Months of Follow-Up. Adv. Ther. 2019, 36, 2493–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Huang, L.; Yu, J. Effects of blueberry anthocyanins on retinal oxidative stress and inflammation in diabetes through Nrf2/HO-1 signaling. J. Neuroimmunol. 2016, 301, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakaishi, H.; Matsumoto, H.; Tominaga, S.; Hirayama, M. Effects of black current anthocyanoside intake on dark adaptation and VDT work-induced transient refractive alteration in healthy humans. Altern. Med. Rev. 2000, 5, 553–562. [Google Scholar]

- Muth, E.R.; Laurent, J.M.; Jasper, P. The effect of bilberry nutritional supplementation on night visual acuity and contrast sensitivity. Altern. Med. Rev. 2000, 5, 164–173. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q.; Chen, X.Y.; Martin, C. Scutellaria baicalensis, the golden herb from the garden of Chinese medicinal plants. Sci. Bull. 2016, 61, 1391–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinda, B.; Dinda, S.; DasSharma, S.; Banik, R.; Chakraborty, A.; Dinda, M. Therapeutic potentials of baicalin and its aglycone, baicalein against inflammatory disorders. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 131, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.C.; Shen, S.C.; Chen, L.G.; Lee, T.J.; Yang, L.L. Wogonin, baicalin, and baicalein inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 gene expressions induced by nitric oxide synthase inhibitors and lipopolysaccharide. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2001, 61, 1417–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Zhao, B.; Wang, J. The Pharmacological Efficacy of Baicalin in Inflammatory Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.R.; Do, C.W.; To, C.H. Potential therapeutic effects of baicalein, baicalin, and wogonin in ocular disorders. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 30, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzone, F.; Nebbioso, M.; Pergolizzi, T.; Attanasio, G.; Musacchio, A.; Greco, A.; Limoli, P.G.; Artico, M.; Spandidos, D.A.; Taurone, S.; et al. Anti-inflammatory role of curcumin in retinal disorders (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 22, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurenka, J.S. Anti-inflammatory properties of curcumin, a major constituent of Curcuma longa: A review of preclinical and clinical research. Altern. Med. Rev. 2009, 14, 141–153. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, B.B.; Harikumar, K.B. Potential therapeutic effects of curcumin, the anti-inflammatory agent, against neurodegenerative, cardiovascular, pulmonary, metabolic, autoimmune and neoplastic diseases. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2009, 41, 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giordano, A.; Tommonaro, G. Curcumin and Cancer. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsamanesh, N.; Moossavi, M.; Bahrami, A.; Butler, A.E.; Sahebkar, A. Therapeutic potential of curcumin in diabetic complications. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 136, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewlings, S.J.; Kalman, D.S. Curcumin: A Review of Its Effects on Human Health. Foods 2017, 6, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegrini, D.; Raimondi, R.; Borgia, A.; Sorrentino, T.; Montesano, G.; Tsoutsanis, P.; Cancian, G.; Verma, Y.; De Rosa, F.P.; Romano, M.R. Curcumin in Retinal Diseases: A Comprehensive Review from Bench to Bedside. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peddada, K.V.; Brown, A.; Verma, V.; Nebbioso, M. Therapeutic potential of curcumin in major retinal pathologies. Int. Ophthalmol. 2019, 39, 725–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, U.P.S.; Surico, P.L.; Mori, T.; Singh, R.B.; Cutrupi, F.; Premkishore, P.; Gallo Afflitto, G.; Di Zazzo, A.; Coassin, M.; Romano, F. Antioxidants in Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Lights and Shadows. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, P.; Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Newman, R.A.; Aggarwal, B.B. Bioavailability of curcumin: Problems and promises. Mol. Pharm. 2007, 4, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muangnoi, C.; Sharif, U.; Ratnatilaka Na Bhuket, P.; Rojsitthisak, P.; Paraoan, L. Protective Effects of Curcumin Ester Prodrug Curcumin Diethyl Disuccinate against H2O2-Induced Oxidative Stress in Human Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells: Potential Therapeutic Avenues for Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, J.M.; Shin, D.Y.; Lee, S.J.; Joe, Y.; Zheng, M.; Yim, J.H.; Callaway, Z.; Chung, H.T. Curcumin protects retinal pigment epithelial cells against oxidative stress via induction of heme oxygenase-1 expression and reduction of reactive oxygen. Mol. Vis. 2012, 18, 901–908. [Google Scholar]

- Carozza, G.; Tisi, A.; Capozzo, A.; Cinque, B.; Giovannelli, A.; Feligioni, M.; Flati, V.; Maccarone, R. New Insights into Dose-Dependent Effects of Curcumin on ARPE-19 Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsoudi, A.F.; Wai, K.M.; Koo, E.; Mruthyunjaya, P.; Rahimy, E. Curcuma-Based Nutritional Supplements and Risk of Age-Related Macular Degeneration. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2024, 142, 1114–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allegrini, D.; Raimondi, R.; Angi, M.; Ricciardelli, G.; Montericcio, A.; Borgia, A.; Romano, M.R. Curcuma-Based Nutritional Supplement in Patients with Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. J. Med. Food 2021, 24, 1191–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, P.R.; Madanagopalan, V.G. Role of Curcumin in Retinal Diseases-A review. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2022, 260, 1457–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.K.; Kumar, B.; Nag, T.C.; Agrawal, S.S.; Agrawal, R.; Agrawal, P.; Saxena, R.; Srivastava, S. Curcumin Prevents Experimental Diabetic Retinopathy in Rats Through Its Hypoglycemic, Antioxidant, and Anti-Inflammatory Mechanisms. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 27, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khimmaktong, W.; Petpiboolthai, H.; Sriya, P.; Anupunpisit, V. Effects of curcumin on restoration and improvement of microvasculature characteristic in diabetic rat’s choroid of eye. J. Med. Assoc. Thail. 2014, 97, S39–S46. [Google Scholar]

- Amini, S.; Dehghani, A.; Sahebkar, A.; Iraj, B.; Rezaeian-Ramsheh, A.; Askari, G.; Majeed, M.; Bagherniya, M. The efficacy of curcumin-piperine supplementation in patients with nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy: An optical coherence tomography angiography-based randomized controlled trial. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2024, 29, 64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kapil, D.; Bari, A.; Sharma, N.; Velpandian, T.; Sinha, R.; Maharana, P.; Kaur, M.; Agarwal, T. Role of oral bio-enhanced curcumin in dry eye disease. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2025, 73, S428–S434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Li, C.; Guo, H.; Kern, T.S.; Huang, K.; Zheng, L. Curcumin inhibits neuronal and vascular degeneration in retina after ischemia and reperfusion injury. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alex, A.F.; Spitznas, M.; Tittel, A.P.; Kurts, C.; Eter, N. Inhibitory Effect of Epigallocatechin Gallate (EGCG), Resveratrol, and Curcumin on Proliferation of Human Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells In Vitro. Curr. Eye Res. 2010, 35, 1021–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenivasan, S.; Thirumalai, K.; Danda, R.; Krishnakumar, S. Effect of curcumin on miRNA expression in human Y79 retinoblastoma cells. Curr. Eye Res. 2012, 37, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zheng, L.; Yang, Q.; Huang, W.; Yan, X. miR-22-Mediated Regulation of Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling by Curcumin in Retinoblastoma. J. Vis. Exp. 2025, 223, e69300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Hu, D.N.; Pan, Z.; Lu, C.W.; Xue, C.Y.; Aass, I. Curcumin protects against hyperosmoticity-induced IL-1beta elevation in human corneal epithelial cell via MAPK pathways. Exp. Eye Res. 2010, 90, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.P.; Chang, H.C.; Lu, L.S.; Liu, D.Z.; Wang, T.J. Activation of kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1/nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2/antioxidant response element pathway by curcumin enhances the anti-oxidative capacity of corneal endothelial cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 141, 111834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, F.; Zhang, M.C.; Zhu, Y. Inhibitory effect of curcumin on corneal neovascularization in vitro and in vivo. Ophthalmologica 2008, 222, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, N.R.; Gupta, S.K.; Das, G.K.; Kumar, N.; Mongre, P.K.; Haldar, D.; Beri, S. Evaluation of Ophthacare eye drops—A herbal formulation in the management of various ophthalmic disorders. Phytother. Res. 2001, 15, 618–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; He, J.; Chen, W.; Yu, Y.; Li, W.; Du, Z.; Xie, T.; Ye, Y.; Hua, S.Y.; Zhong, D.; et al. Light-Activatable Synergistic Therapy of Drug-Resistant Bacteria-Infected Cutaneous Chronic Wounds and Nonhealing Keratitis by Cupriferous Hollow Nanoshells. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 3299–3315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capasso, L.; De Masi, L.; Sirignano, C.; Maresca, V.; Basile, A.; Nebbioso, A.; Rigano, D.; Bontempo, P. Epigallocatechin Gallate (EGCG): Pharmacological Properties, Biological Activities and Therapeutic Potential. Molecules 2025, 30, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Mukhtar, H. Tea Polyphenols in Promotion of Human Health. Nutrients 2018, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusciano, D. Health Benefits of Epigallocatechin Gallate and Forskolin with a Special Emphasis on Glaucoma and Other Retinal Diseases. Medicina 2024, 60, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzanti, G.; Di Sotto, A.; Vitalone, A. Hepatotoxicity of green tea: An update. Arch. Toxicol. 2015, 89, 1175–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falsini, B.; Marangoni, D.; Salgarello, T.; Stifano, G.; Montrone, L.; Di Landro, S.; Guccione, L.; Balestrazzi, E.; Colotto, A. Effect of epigallocatechin-gallate on inner retinal function in ocular hypertension and glaucoma: A short-term study by pattern electroretinogram. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2009, 247, 1223–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasiunas, K.; Galgauskas, S. Green tea-a new perspective of glaucoma prevention. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 15, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Rui, Y.X.; Guo, S.D.; Luan, F.; Liu, R.; Zeng, N. Ferulic acid: A review of its pharmacology, pharmacokinetics and derivatives. Life Sci. 2021, 284, 119921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, S.C.; Huang, W.C.; Pang, S.J.H.; Wu, Y.H.; Cheng, C.Y. Quercetin Inhibits the Production of IL-1beta-Induced Inflammatory Cytokines and Chemokines in ARPE-19 Cells via the MAPK and NF-kappaB Signaling Pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ungurianu, A.; Zanfirescu, A.; Margină, D. Exploring the therapeutic potential of quercetin: A focus on its sirtuin-mediated benefits. Phytother. Res. 2024, 38, 2361–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, L.; Barbhuiya, S.A.A.; Saikia, K.; Kalita, P.; Dutta, P.P. Therapeutic Potential of Quercetin in Diabetic Neuropathy and Retinopathy: Exploring Molecular Mechanisms. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2024, 24, 2351–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Gupta, S.K.; Nag, T.C.; Srivastava, S.; Saxena, R.; Jha, K.A.; Srinivasan, B.P. Retinal neuroprotective effects of quercetin in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Exp. Eye Res. 2014, 125, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migone, C.; Cerri, L.; Fabiano, A.; Parri, S.; Mezzetta, A.; Guazzelli, L.; Piras, A.M.; Zambito, Y.; Sarmento, B. Olive leaf extract-based eye drop formulations for corneal wound healing. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2025, 110, 107026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, J.L.; Cambien, F.; Ducimetiere, P. Epidemiologic characteristics of coronary disease in France. Nouv. Presse Med. 1981, 10, 1111–1114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Renaud, S.; Gueguen, R. The French paradox and wine drinking. In Novartis Foundation Symposium 216-Alcohol and Cardiovascular Diseases: Alcohol and Cardiovascular Diseases: Novartis Foundation Symposium; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 1998; Volume 216, pp. 208–217. [Google Scholar]

- de la Lastra, C.A.; Villegas, I. Resveratrol as an anti-inflammatory and anti-aging agent: Mechanisms and clinical implications. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2005, 49, 405–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baur, J.A.; Sinclair, D.A. Therapeutic potential of resveratrol: The in vivo evidence. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006, 5, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kaundal, R.K.; Iyer, S.; Sharma, S.S. Effects of resveratrol on nerve functions, oxidative stress and DNA fragmentation in experimental diabetic neuropathy. Life Sci. 2007, 80, 1236–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Namkoong, K.; Shin, M.; Park, J.; Yang, E.; Ihm, J.; Thu, V.T.; Kim, H.K.; Han, J. Cardiovascular Protective Effects and Clinical Applications of Resveratrol. J. Med. Food 2017, 20, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, C.N.; Gan, R.Y.; Li, H.B. Health Benefits and Molecular Mechanisms of Resveratrol: A Narrative Review. Foods 2020, 9, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Amero, K.K.; Kondkar, A.A.; Chalam, K.V. Resveratrol and Ophthalmic Diseases. Nutrients 2016, 8, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryl, A.; Falkowski, M.; Zorena, K.; Mrugacz, M. The Role of Resveratrol in Eye Diseases-A Review of the Literature. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, D.; Cornebise, C.; Courtaut, F.; Xiao, J.; Aires, V. New Highlights of Resveratrol: A Review of Properties against Ocular Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Yang, M.; Fan, L.; Yan, Q.; Zhang, L.; Mu, P.; Lu, F. Interaction between resveratrol and SIRT1: Role in neurodegenerative diseases. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2025, 398, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walle, T. Bioavailability of resveratrol. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011, 1215, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaito, A.; Posadino, A.M.; Younes, N.; Hasan, H.; Halabi, S.; Alhababi, D.; Al-Mohannadi, A.; Abdel-Rahman, W.M.; Eid, A.H.; Nasrallah, G.K.; et al. Potential Adverse Effects of Resveratrol: A Literature Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, V.A.; Patel, K.R.; Viskaduraki, M.; Crowell, J.A.; Perloff, M.; Booth, T.D.; Vasilinin, G.; Sen, A.; Schinas, A.M.; Piccirilli, G.; et al. Repeat Dose Study of the Cancer Chemopreventive Agent Resveratrol in Healthy Volunteers: Safety, Pharmacokinetics, and Effect on the Insulin-like Growth Factor Axis. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 9003–9011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pintea, A.; Rugina, D.; Pop, R.; Bunea, A.; Socaciu, C.; Diehl, H.A. Antioxidant Effect of-Resveratrol in Cultured Human Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 27, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagineni, C.N.; Raju, R.; Nagineni, K.K.; Kommineni, V.K.; Cherukuri, A.; Kutty, R.K.; Hooks, J.J.; Detrick, B. Resveratrol Suppresses Expression of VEGF by Human Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells: Potential Nutraceutical for Age-related Macular Degeneration. Aging Dis. 2014, 5, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Kim, Y.S.; Roh, G.S.; Choi, W.S.; Cho, G.J. Resveratrol blocks diabetes-induced early vascular lesions and vascular endothelial growth factor induction in mouse retinas. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012, 90, e31–e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Wang, L.; Huang, K.; Zheng, L. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in retinal vascular degeneration: Protective role of resveratrol. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2012, 53, 3241–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiano, E.; Vaccaro, S.; Scorcia, V.; Carnevali, A.; Borselli, M.; Chisari, D.; Guerra, F.; Iannuzzo, F.; Tenore, G.C.; Giannaccare, G.; et al. From Vineyard to Vision: Efficacy of Maltodextrinated Grape Pomace Extract (MaGPE) Nutraceutical Formulation in Patients with Diabetic Retinopathy. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, K.B.; Li, Z.Y.; Lei, Y.M.; Xu, W.X.; Ouyang, L.Y.; He, T.; Xing, Y.Q. Resveratrol attenuates retinal ganglion cell loss in a mouse model of retinal ischemia reperfusion injury via multiple pathways. Exp. Eye Res. 2021, 209, 108683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, H.; Zhuang, J.; Hu, P.; Ye, W.; Chen, S.; Pang, Y.; Li, N.; Deng, C.; Zhang, X. Resveratrol Delays Retinal Ganglion Cell Loss and Attenuates Gliosis-Related Inflammation From Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2018, 59, 3879–3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sareen, D.; van Ginkel, P.R.; Takach, J.C.; Mohiuddin, A.; Darjatmoko, S.R.; Albert, D.M.; Polans, A.S. Mitochondria as the primary target of resveratrol-induced apoptosis in human retinoblastoma cells. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006, 47, 3708–3716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eseberri, I.; Trepiana, J.; Léniz, A.; Gómez-García, I.; Carr-Ugarte, H.; González, M.; Portillo, M.P. Variability in the Beneficial Effects of Phenolic Compounds. A Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Z.; Rauf, A.; Orhan, I.E.; Mubarak, M.S.; Akram, Z.; Islam, M.R.; Imran, M.; Edis, Z.; Kondapavuluri, B.K.; Thangavelu, L.; et al. Antioxidant Potential of Polyphenolic Compounds, Sources, Extraction, Purification and Characterization Techniques: A Focused Review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e71259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Rajala, A.; Rajala, R.V.S. Nanoparticles as Delivery Vehicles for the Treatment of Retinal Degenerative Diseases. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1074, 117–123. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Deng, Z.; Ji, D. Advances in the development of lipid nanoparticles for ophthalmic therapeutics. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 178, 117108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souto, E.B.; Dias-Ferreira, J.; López-Machado, A.; Ettcheto, M.; Cano, A.; Camins Espuny, A.; Espina, M.; Garcia, M.L.; Sánchez-López, E. Advanced Formulation Approaches for Ocular Drug Delivery: State-Of-The-Art and Recent Patents. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahu, A.; Patel, A.R.; Shetty, K.H.; Shah, D.O.; Willcox, M.D.; Maulvi, F.A.; Desai, D.T. Revolutionizing age-related macular degeneration treatment: Advances and future directions in non-invasive retinal drug delivery systems. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 683, 126009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Polyphenols | Sources | Effects | Mechanisms of Action | Limitations | Ocular Diseases | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthocyanins | Blueberries Blackcurrant Bilberry Grape | Antioxidant Anti-inflammatory Neuroprotection | ↓ ROS ↑ ocular perfusion Modulation of Nrf2, NF-κB, MAPKs | Low oral stability Low bioavailability | Glaucoma | [32,33] |

| Diabetic retinopathy | [34,35] | |||||

| Visual function | [36] | |||||

| Baicalin | Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi | Antioxidant Anti-inflammatory Immunomodulatory Neuroprotection | ↓ NF-κB ↓ IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α ↓ NLRP3 | No clinical trials | Uveitis | [37] |

| Glaucoma | [38] | |||||

| AMD | [39] | |||||

| Curcumin | Turmeric | Antioxidant Anti-inflammatory Anti-angiogenic Neuroprotective | ↓ NF-κB ↓ IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α ↑ Nrf2/HO-1 ↓ VEGF | Low bioavailability Rapid metabolism | AMD | [40,41] |

| Diabetic retinopathy | [42] | |||||

| Dry eye disease | [43] | |||||

| Corneal diseases | [44] | |||||

| Bacterial Ocular Diseases | [45] | |||||

| Epigallocatechin-3-gallate | Green tea | Antioxidant Anti-inflammatory | ↓ NF-κB ↓ MAPKs ↓ VEGF | Low stability Limited clinical data | Glaucoma | [46] |

| AMD | [47] | |||||

| Diabetic retinopathy | [48] | |||||

| Quercetin | Onions Apples Berries Kale | Antioxidant Anti-inflammatory Neuroprotection | ↓ NF-κB ↓ MAPKs ↓ ROS | Poor solubility and absorption | Diabetic retinopathy | [49] |

| Glaucoma | [50,51] | |||||

| AMD | [52] | |||||

| Resveratrol | Red grapes Berries Peanuts | Antioxidant Anti-inflammatory Anti-apoptotic | ↓ ROS ↓ NF-κB ↓ IL-6, TNF-α | Bioavailability < 1% | AMD | [53] |

| Diabetic retinopathy | [54] | |||||

| Diabetic cataract | [55] | |||||

| Glaucoma | [56] | |||||

| Uveitis | [57] | |||||

| Eye Tumors | [58] | |||||

| Myopia | [59] | |||||

| Dry eye disease | [60] | |||||

| Ferulic acid | Ranunculaceae and Gramineae | Antioxidant Anti-inflammatory | ↑ PI3K/Akt ↑ Nrf2/HO-1 ↓ NF-κB | Poor bioavailability No clinical trials | AMD | [61] |

| Diabetic retinopathy | [62] | |||||

| Cataract | [63] |

| Formulation | Ocular Disease | Subject | Dose | Duration | Effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blackcurrant anthocyanins | Glaucoma |

n = 38 open-angle glaucoma patients

(n = 19; n = 19 placebo) | 50 mg/day | 2 years | ↓ IOP slower visual field loss | [32] |

| Blackcurrant anthocyanins | Glaucoma | n = 12 healthy volunteers n = 21 glaucoma patients (n = 12; n = 9 placebo) | 50 mg/day | 4 weeks | ↓ IOP ↑ optic nerve head blood flow | [33] |

| Macuprev® | Intermediate AMD | n = 30 AMD patients (n = 15; n = 15 placebo) | anthocyanins 90 mg | 6 months | ↑ macular preganglionic function | [79] |

| Curcumin | Dry AMD | n = 20 AMD patients (n = 14; n = 6 placebo) | 1330 mg × 2/die | 6 months | ↓ drusen volume, ↓ foveal volume | [41] |

| Curcumin + piperine | NPDR |

n = 60 DR patients

(n = 30; n = 30 placebo) | 1010 mg/day | 12 weeks | ↑ antioxidant markers ↓ oxidative stress | [106] |

| Oral supplement blend (curcumin, lutein, zeaxanthin, vitamin D3) | Dry Eye disease |

n = 155 dry eye patients

(n = 77; n = 78 placebo) | 200 mg curcuminoids/day | 8 weeks | ↑ tear stability, production, and quality ↓ inflammation | [43] |

| Curcumin | Dry eye disease | n = 40 dry eye patients (n = 20; n = 20 placebo) | 500 mg tablets × 2/die | 3 months | ↑film stability ↓bulbar redness | [107] |

| Green tea and ECGC | Glaucoma prevention | n = 43 healthy volunteers (n = 17 green tea; n = 17 ECGC; n = 9 placebo) | 400 mg | 90 min | ↓ IOP | [122] |

| Grape pomace extract | DR | n = 99 non-proliferative DR patients (n = 49; n = 50 placebo) | 400 mg × 2/die | 6 months | ↓ retinal swelling, ↓ oxidative stress | [147] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

D’Angelo, A.; Giannaccare, G.; Lixi, F.; Troisi, M.; Adamo, G.G.; Lee, D.; De Pascale, I.; Pellegrino, A.; Vitiello, L. Polyphenols and Eye Health: A Narrative Review of the Literature on the Therapeutic Effects for Ocular Diseases. Nutrients 2026, 18, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010069

D’Angelo A, Giannaccare G, Lixi F, Troisi M, Adamo GG, Lee D, De Pascale I, Pellegrino A, Vitiello L. Polyphenols and Eye Health: A Narrative Review of the Literature on the Therapeutic Effects for Ocular Diseases. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010069

Chicago/Turabian StyleD’Angelo, Angela, Giuseppe Giannaccare, Filippo Lixi, Mario Troisi, Ginevra Giovanna Adamo, Deokho Lee, Ilaria De Pascale, Alfonso Pellegrino, and Livio Vitiello. 2026. "Polyphenols and Eye Health: A Narrative Review of the Literature on the Therapeutic Effects for Ocular Diseases" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010069

APA StyleD’Angelo, A., Giannaccare, G., Lixi, F., Troisi, M., Adamo, G. G., Lee, D., De Pascale, I., Pellegrino, A., & Vitiello, L. (2026). Polyphenols and Eye Health: A Narrative Review of the Literature on the Therapeutic Effects for Ocular Diseases. Nutrients, 18(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010069