Abstract

Background/Objectives: Most research linking diet and mental health outcomes is from high-income countries, limiting insight into how these relationships manifest in culturally diverse, vulnerable contexts, such as the Caribbean. This scoping review aims to map existing research on the relationship between aspects of diet and mental health within Caribbean populations, to identify evidence gaps and guide future research. Methods: Eleven databases were searched for studies published between 2000 and 2024 in 33 Caribbean countries which assessed the relationship between diet and mental health outcomes. Duplicate screening and extraction were conducted using Redcap software, and a narrative synthesis and evidence gap map were created. The original protocol was registered with Open Science Framework. Results: Forty-four records were included, nine of which focused on eating disorders (examined separately). Most were cross-sectional studies of the general population, with few experimental and qualitative studies. Surveys were the most frequently applied data collection tool, often without mention of local adaptation or validation. Most records examined food security and depression as their ‘diet’ and ‘mental health’ variables, respectively. Frequently explored relationships included autism and seafood intake and fruit and vegetable intake, while depression and food security was the most widely examined relationship across studies. Conclusions: Caribbean research on diet–mental health relationships is growing though it is limited in scope, design, and cultural validity. Strengthening this evidence base requires studies whose primary aim is in nutritional psychiatry, using culturally relevant tools, and an expansion of study designs that incorporate Caribbean food systems and sociocultural contexts surrounding diet and mental health.

Keywords:

review; diet; nutrition; food security; mental health; depression; anxiety; Caribbean; SIDS; culture 1. Introduction

Mental health disorders affect over 970 million people worldwide, making them the leading cause of years lived with disability (one in six) and a significant source of societal and economic strain [1]. Reduced economic productivity and direct costs of care due to mental health are expected to cost the world economy USD 6 trillion by 2030 [1].

Determinants of mental health are wide-reaching, yet the impact of diet on mental health outcomes is gaining increased attention [2,3]. Evidence suggests poor diet quality as a modifiable risk factor for mental health conditions, and existing research has investigated its potential impact in two main ways: the impact of specific nutrients (e.g., Vitamin D, omega-3 fatty acids) and the impact of broader dietary patterns (e.g., ultra-processed food consumption, Mediterranean diet) [1,4,5]. For instance, a 2022 review reports the significance of micronutrients and antioxidants in the development of some psychiatric disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, and depression [6]. Diets high in ultra-processed foods have been associated with systemic (including neural) inflammation and increased risk for depression [7,8]. Research has also highlighted benefits of plant-based diets on symptomatology of depression and dementia [9,10,11]. Likewise, the ketogenic diet has garnered attention for its potential for improving the symptomatology of dementia, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and unipolar depression/anxiety [12,13,14]. Further, the ketogenic diet was added to the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Clinical Guidelines for Epilepsies for drug-resistant paediatric epilepsy [15]. A growing number of reviews explore the relationship between diet and mental health—some focusing on specific diets or food groups (e.g., plant-based or ketogenic diets, fruits and vegetables) and/or mental health conditions (e.g., depression, anxiety) [14,16,17,18,19], others taking a broader focus on these variables [20,21,22]. This growing research has led to the conceptualisation of ‘nutritional psychiatry’ as its own field of work [23].

Despite a growing evidence base, gaps remain in examining diverse cultural, dietary, and environmental contexts. Most studies are conducted in high-income, Western countries such as the United States and Europe, limiting generalisability of findings to low-and-middle-income countries (LMIC) and other under-represented countries such as Small Island Developing States (SIDS). Despite most of the world’s population living in LMICs, less than a quarter of the diet–mental health evidence and only 10–20% of experimental studies on the topic are conducted in these populations [24]. SIDS are also underrepresented in research overall, given their smaller populations and capacities [25]. This evidence gap is significant considering that socioeconomic factors, cultural dietary practices, and differing mental health beliefs may play a role in the exploration of diet–mental health relationships [26,27]. This gap is further accentuated by mutual geographic/climatic, environmental, and economic vulnerabilities of these regions, which disproportionately impact their food systems and contribute to high levels of food insecurity [28,29]. Without evidence from a wider range of settings such as these, global dietary recommendations in support of mental health remain limited in their generalisability.

The Caribbean region, comprising a mix of high and LMICs and 16 of the 39 SIDS [30], represents a prime setting for expanding diet–mental health research. Coupled with rising food insecurity levels within its fragile food system [31,32,33], the region has undergone a nutrition transition from traditional, nutrient-dense whole foods to a reliance on imported, low-nutrient, processed foods [34,35]. Further, Caribbean diets consistently fall below recommended targets for key food groups such as fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, and whole grains [36]. Increasing reliance on poor quality foods contributes to a rise in metabolic risk factors including elevated blood pressure, blood glucose, blood lipids, and obesity levels and a growing burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer [37,38]. These conditions not only account for 75% of regional mortality, but also are frequently comorbid with poor mental health [1]. This physical–mental health syndemic is further fuelled by the region’s significant vulnerability to climate change impacts, global economic shifts, and its own unique cultural histories which can shape both food systems and psychosocial stressors [32].

Adding to this backdrop is the growing mental health burden in the Caribbean. While Caribbean-wide data is limited and largely model-based, Global Burden of Disease data indicate that mental health disorders contribute to 5% of DALYs and 16% of YLD in 2019 in the Caribbean [29,39]. This burden is expected to rise at least until 2050, particularly for dementia [40]. Of note, Guyana and Suriname rank 4th and 7th, respectively, among global suicide rates, with 24.8 and 22.3 deaths per 100,000 in 2021 [41]. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2030 stresses the global need for stronger leadership and governance, comprehensive and integrated services, prevention and promotion strategies, and information systems [42]. Given the growing syndemic and comorbidity of physical NCDs and mental health conditions, regional calls to action have been made to include mental health in the heavy NCD focus of countries’ health agendas, and address their underlying causes and impacts [43,44,45,46]. These calls include stronger leadership, policies, and advocacy in support of mental health and strengthening of the region’s limited mental health data and research in the Caribbean.

Understanding the research landscape of the relationship between diet and mental health in the Caribbean is the first step to exploring the role that modifying the population’s diet could have on the region’s mental health burden. Thus, the aim of this review is to map research conducted in the Caribbean that examine the relationship between diet and mental health outcomes to elucidate research gaps and focus future Caribbean-based research on this topic.

2. Methods

This review follows methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [47,48]. The original protocol was registered with Open Science Framework (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/TKJP5).

2.1. Definitions of Variables of Interest

The term ‘diet’ for this review refers to any dietary intake, including nutrient intake, dietary patterns, and dietary quality (inclusive of food security). The term ‘mental health’ is broadly defined by the WHO to include mental disorders, psychosocial disabilities, and other mental states associated with significant distress, impairment in functioning, or risk of self-harm [49]. Further details of these definitions are listed in Table 1. The year 2000 was selected as the starting point for the current study as nutrition research concerning mental health increases substantially after this date [2].

2.2. Eligibility

Eligibility criteria are listed in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria for review.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria for review.

| Item | Included | Excluded |

|---|---|---|

| Study design | Experimental or observational studies (qualitative and quantitative), case reports, and conference proceedings (where full-text/data was available). Reviews are included at the title/abstract screening stage only to identify potentially eligible studies. | Editorials. |

| Study setting | Countries/territories in the Caribbean region are included, inclusive of Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba/Bonaire/Curacao, The Bahamas, Barbados, St. Bart’s, Belize, Cayman Islands, Cuba, Dominica, Dominican Republic, St. Eustatius, French Guiana, Grenada, Guadeloupe, Guyana, Haiti, Jamaica, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, St. Martin, St. Maarten, Martinique, Montserrat, Puerto Rico, St. Vincent and The Grenadines, Saba, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, Turks and Caicos, and the Virgin Islands (US and British). This list is based on that of previous Caribbean-based systematic reviews on social determinants of health [50,51,52]. | Caribbean diaspora. |

| Population | Humans of any age residing in the included study settings. | |

| Intervention | Any intervention; however, studies did not need to implement an intervention to be eligible (i.e., observational designs included). | |

| Diet variable | Any indicator of ‘diet’, including intake of any nutrient, supplement or food, and assessed using any quantitative dietary assessment method (such as food frequency questionnaires, dietary recall, indices of dietary quality, food insecurity scales) or qualitative method (such as interviews or focus groups). | Variables that are not direct measures of food security or diet intake/quality, including: attitudes to/knowledge of diet, water or alcohol intake, and physical/biological proxies of diet/nutritional status (e.g., stunting, wasting, obesity, biological samples of nutrients). |

| Mental health variable | Any indicator of ‘mental health’ assessed using relevant symptomatic scales or screening tools (e.g., Patient Health Questionnaire-9 Depression scale), diagnostic criteria (e.g., Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) or as experienced subjectively by participants (such as in qualitative studies or other means of self-report). This broad inclusion of symptomatology assessment aligns with recommendations to avoid narrowly focusing on diagnostic criteria which could skew potential differing concepts of mental health [24,53]. Examples of indicators include common disorders such as depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, as well as less explicit concepts like insomnia. Neurological conditions such as autism, epilepsy, attention deficit and hyperactivity disorders, dementias and Parkinson’s disease are also included. While classified in separate chapters in diagnostic manuals, experts argue the distinction between neurological and psychological is inconsistent with scientific understanding of nervous system disorders with clear mental health components [54]. | Proxies for mental health status such as drug or alcohol use. |

| Additional notes: analysis between diet and mental health variables |

|

|

| Publication status | Published or unpublished studies released between 1 January 2000 and 11 February 2024 (date of search) in English, Spanish, French, Dutch (i.e., four dominant Caribbean languages). |

2.3. Search Strategy

Search terms were conceptualised through examination of those used by other reviews on the topic and discussion with colleagues in the field [2,24,52]. The terms were broad to ensure sensitivity, and an example using PubMed syntax is listed in Supplementary Materials Table S1. Eleven databases were searched: Web of Science (via Clarivate), MEDLINE (via PubMed), EMBASE (via Ovid), SciELO, CINAHL (via EBSCO), CUMED (via WHO Virtual Health Library), LILACS (via WHO Virtual Health Library), PAHO and PAHO IRIS (via WHO Virtual Health Library), MedCarib (via WHO Virtual Health Library), PsycINFO (via Ovid), and Global Health (via Ovid). In addition, researchers scanned reference lists of included full-text records and of systematic reviews retrieved during title/abstract screening.

2.4. Record Selection and Data Extraction

Records retrieved from database searching were added to Rayyan reference manager [55]. Authors of inaccessible articles were contacted where contact information was given. Records were reviewed against the eligibility criteria in two steps: (1) Initial screening of titles and abstracts of records → potentially relevant (include) and not relevant (exclude); and (2) Secondary screening of the full-text records identified as potentially relevant in Step 1 → relevant (include) and not relevant (exclude). Key details of eligible records were extracted into REDCap data management software version 15.9.3 [56], including publication information, intervention details (if applicable) and indicators/outcome measures and data collection tools. Screening and data extraction were performed in duplicate by two independent reviewers, and any disagreement or uncertainty was resolved by a third reviewer.

2.5. Data Synthesis

The findings are reported narratively as a descriptive summary of publication details and study characteristics including design, settings, intervention, variables, tools applied, and relationships assessed. An evidence gap map was constructed summarising the distribution of existing evidence. Following scoping review methodology, effect measures and study risk of bias were not assessed.

3. Results

3.1. Summary of Included Records

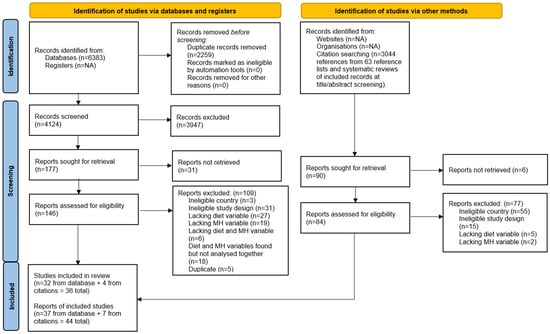

Of the 6318 database search results and 3044 references screened, 44 records from 36 studies were included (See Figure 1). The references for these 44 records are listed (in the same order as the table) in Supplementary Materials Table S2.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of records [57].

Of the 44 records, 35 examined diet and mental health relationships and 9 were classified as ‘eating disorder’ records. Eating disorders are not an aspect of diet but are considered a behavioural condition that affects dietary intake [58]. Although these studies did not fit the primary aim of this scoping review, their relevance to the topic is acknowledged and so they are briefly and separately presented at the end of this Results section.

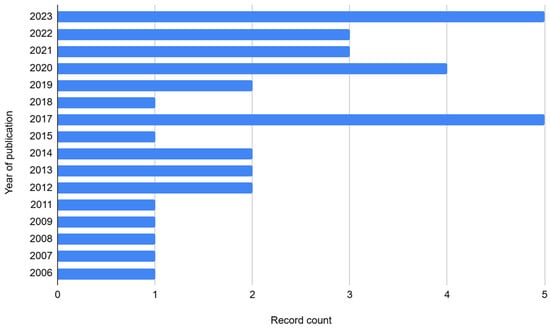

The 35 included diet–mental health relationship records were published in 33 peer-reviewed journals, one e-book of studies, and one thesis. Only half were open access. The scope of publications included public health, medical science (broadly), and nutrition (n = 26), with relatively few mental health journals (n = 5). The remaining publications were one unpublished thesis and three environmental journals. Publications spanned from 2006 to 2023, with a gradual increase from one article published per year to five articles per year (See Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Bar chart of the number of Caribbean diet–mental health relationship records published per year.

Studies were conducted in 20 of the 33 Caribbean countries, with most records from Jamaica (n = 12 records), Barbados (n = 7), Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, and Trinidad (n = 6 each). Others included Cuba and Haiti (n = 4 each); Grenada (n = 3); US Virgin Islands and Bahamas (n = 2 each); and Antigua, Anguilla, Belize, Curacao, Guadeloupe, Martinique, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and Suriname (n = 1 each). Overall, 9 of the 35 records reported analyses of pooled data from multiple countries—3 with pooled data from Caribbean countries only [59,60,61] and 6 which also pooled international data [62,63,64,65,66,67].

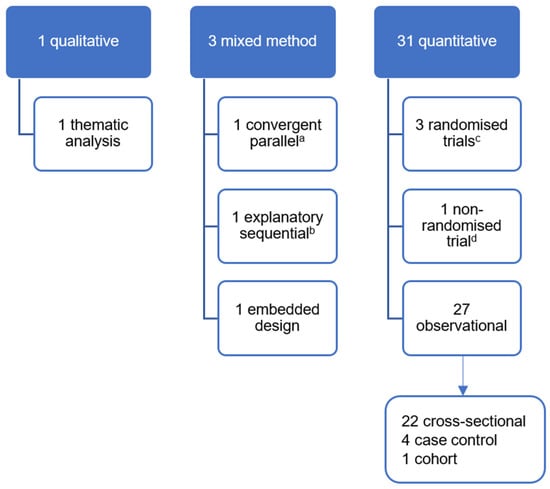

3.2. Study Details

Study details of the 35 diet–mental health relationship records are listed in Table 2. The sampling frame for most records was the general population/communities (n = 18 records), while others sampled from schools (n = 10), clinics (n = 6), and prison (n = 1). Ten records used child-only samples [67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76], and some sampled specifically from low-income communities or intentionally recruited participants who were pregnant or reported health issues (e.g., cancer, Parkinson’s disease). Nearly all records used quantitative, observational designs (n = 31) (See Figure 3).

Table 2.

Study design details of 35 included diet–mental health relationship records [59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93].

Figure 3.

Study designs of records reporting diet–mental health relationships. a—Only qualitative data of this mixed-methods study contributed to this review; b—This mixed-methods study included an uncontrolled before and after non-randomised trial of an intervention; c—All three randomised controlled trials are individually randomised parallel-group trials; d—Case study of one patient.

Five records reported on experimental studies [69,79,81,92,93]. One used urban gardens, nutrition, and cooking education to improve food security and subsequently mental and emotional wellbeing among persons living with human immunodeficiency virus in Dominican Republic [81]. Two records from The Jamaican Supplementation and Stimulation Study used milk-based formula supplementation of infants to improve future psychosocial functioning later in life (depression, anxiety, attention deficit, and oppositional behaviour) [92,93]. The final two records implemented a ketogenic diet for (a) adults in Trinidad with various types of cancer to improve their depression and quality of life [79], and (b) a boy in Cuba diagnosed with medication-resistant epilepsy to reduce the frequency and severity of seizure events [69].

Notably, only 10 of 35 records aimed primarily to assess the relationship between diet and mental health, versus 20 records for which this was a secondary aim and 5 where it was not an aim at all. Of these 10 studies, 2 sought to examine the impact of a ketogenic diet intervention (mentioned above) [69,79]; 2 sought to examine the association of dietary patterns and perceived stress among students in Puerto Rico [84,88]; 4 examined the association between food insecurity and (a) suicide ideation/plans/attempt among adolescents across the Caribbean [67,75] and (b) mental health status (including anxiety and depression) in vulnerable communities in Haiti [86] and across several Caribbean countries [59]. One record investigated the association between skipping meals and depression and post-traumatic stress disorder symptomatology among students [66], and another sought to examine the association of annonaceae (e.g., sour soup, sugar apple) consumption and cognitive manifestations in atypical forms of parkinsonism and Parkinson’s disease in Guadeloupe and Martinique [82].

Studies from five records examined diet–mental health relationships during or in response to hazards or disasters—two during the COVID pandemic assessing participants in Barbados, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Puerto Rico [64,65] and three during or after hurricanes affecting the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, and US Virgin Islands [85,89,91].

3.3. Variables and Tools

3.3.1. Indicators of Diet

Of the 35 diet–mental health relationship records, 16 examined food security as the ‘diet’ variable and 19 examined diet intake, quality, or type. Diet intake variables included the intake of macronutrients (e.g., fats, protein) (n = 3 records); supplementation (infant formula) (n = 2); seafood (n = 6); meat (n = 2); fruit and/or vegetable (n = 6); grains (n = 1); meals (n = 2); and snacks (n = 2). Overall diet quality (i.e., diet diversity or food group adequacy) (n = 2) and diet type (i.e., ketogenic diet (n = 2); ‘diabetes mellitus specific’ diet (n = 1); and ‘Western’ diet (n = 1)) (n = 4) were also examined. Most records used food frequency questionnaires to collect dietary data (n = 14); one used 24 h recall and food diary, and another used qualitative interviews. The three remaining experimental records did not explicitly explain their diet assessment procedure [81,92,93].

Food security was most commonly measured using surveys, while two records used qualitative interviews. However, only four records used standardised food security surveys, namely the Household Hunger Scale, Household Food Insecurity Access Scale, Latin American and Caribbean Food Security Scale, and the Food Insecurity Experience Scale Survey Module for Individuals. Others used generalised multi-component surveys, often with only one question assessing food security (n = 10).

Few records explicitly examined processed foods (e.g., cakes, dumplings, soft drinks, Vienna sausages, added sugars) within their diet variables [72,74,84,88,90], and nine records specifically mentioned the production or consumption of local foods. These local foods included annonaceae in Guadeloupe and Martinique [82] and various local fruits and vegetables (e.g., ackee, avocado) in Jamaica [71,72,73,74]. Two examined local food production (a food security intervention) [81] and local food consumption [89] in Dominican Republic. Two others examined individual agricultural assets (a measure of food security) in Haiti [80,86]. All other records assessed diet without specification of local/traditional foods.

3.3.2. Indicators of Mental Health

Depression diagnosis or symptomatology was the most frequently (and widely) examined variable (n = 17 records), followed by perceived stress (n = 8) and anxiety diagnosis/symptomatology (n = 7). Others included suicide ideation/planning (n = 5 records), suicide attempt (n = 2), dementia diagnosis/symptomatology (n = 2), post-traumatic stress disorder symptomatology (n = 2), happiness/enjoyment (n = 2), overall quality of life (includes mental health components) (n = 1), and oppositional behaviour symptomatology (n = 1). Seven records reported on indicators of neurological conditions other than dementia: parkinsonism severity (n = 1), epileptic seizures (n = 1), autism diagnosis (n = 4), and attention deficit behaviours (n = 1). The remaining five records used ambiguous indicators: scores for ‘mental and emotional wellbeing’ (n = 1), ‘mental health symptoms’ (n = 1), ‘negative experience index’ (n = 1), ‘positive experience index’ (n = 2), and having a child at home with a mental disability (n = 1).

A wider variety of tools were used to measure mental health variables than to measure diet variables; 46 unique tools were used for measuring the 16 mental health variables, as shown in Table 3. Among all mental health variables, depression was measured by the widest variety of tools—14 different tools (1 diagnostic test and 13 measures designed to assess symptomatology) across 17 records. On the other hand, the WHO Global School-Based Student Health Survey was used in all five records examining suicidal thoughts and behaviours [67,68,70,75,76]. Some data collection tools assessed multiple different mental health variables in their studies: Geriatric Mental State Exam [94]; Child Vulnerability Survey [60]; WHO Global School-Based Student Health Survey [95]; Behaviour and Activities Checklist [92]; Negative Experience Index [59]; researchers’ own survey; and qualitative interview.

Table 3.

Mental health variables examined and data collection tools used.

3.3.3. Cultural Adaptation of Tools

Although an array of tools was used to collect data on diet and mental health outcomes, only 10 explicitly noted that the data collection tool was culturally adapted to their Caribbean setting. Three of these were qualitative interview guides are assumed to be designed for defined populations of the studies. Five records culturally adapted their tool for dietary intake data collection by adding culturally relevant food groups or questions and piloting [60,79,88], or researchers used a tool previously created for or adapted to the Caribbean setting (e.g., Latin American and Caribbean Food Security Scale) [61,82]. Regarding mental health tools, four records culturally adapted their tool by adding questions and piloting [60,79] or used a tool previously created for or adapted to the Caribbean setting [80,86].

3.4. Relationships Examined

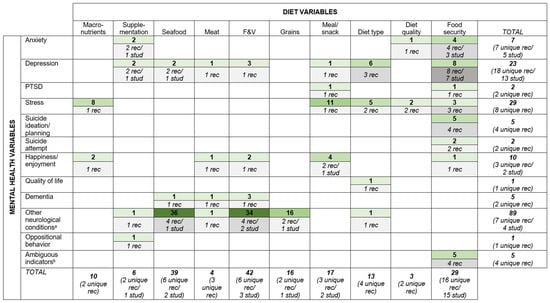

Below, Table 4 details the relationships examined and tools used in each of the 35 included records. Figure 4 further illustrates the distribution across variables of these 179diet–mental health relationships.

Table 4.

List of relationships examined in each of the 35 diet–mental health relationship records [59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93].

Figure 4.

Evidence gap map illustrating the distribution of the 179 diet–mental health relationships across reported diet and mental health variables. Footnote—Numbers in green boxes denote number of relationships examined; numbers in grey boxes denote number of records and studies (where study number is not listed, the records represent their own unique studies); darker colour shading indicates higher numbers of relationships and records. Row and column totals identify the total number of relationships examined for each diet and mental health variable, along with the number of unique records and studies they are found in. a—Other neurological conditions include parkinsonism severity, epileptic seizures, autism diagnosis, and attention deficit behaviours. b—Ambiguous indicators of mental health include ‘mental and emotional wellbeing’, ‘mental health symptoms’, ‘negative experience index’, ‘positive experience index’, and having a child at home with a mental disability.

Fruit and vegetable intake (n = 42 relationships), seafood intake (n = 39), and food security (n = 29) were the most frequently examined diet variables. However, the majority of the seafood intake variables are from the Jamaican Autism Study examining autism diagnosis [71,72,73,74]. ‘Other neurological conditions’ was the most frequently examined mental health variable (n = 89 relationships). However, nearly all are also from the Jamaican Autism Study examining the association between autism diagnosis and the intake of fruits and vegetables, seafood, grains, and meat [71,72,73,74]. Perceived stress (n = 29 relationships) and depression (n = 23) were also frequently reported yet spread across a larger number of unique records/studies (i.e., more widely examined). Food security was the most widely examined diet variable (n = 29 relationships examined in 16 records from 15 studies), and depression was the most widely examined mental health variable (n = 23 relationships examined in 18 records from 13 studies).

With respect to relationships, the most frequently examined relationships were seafood intake and other neurological conditions (n = 36 relationships in four records from one study); fruit and vegetable intake and other neurological conditions (n = 34 relationships in four records from two studies); and grain intake and other neurological conditions (n = 16 relationships in two records from one study)—all from the same Jamaican Autism Study. Apart from these, meal/snack intake and perceived stress (n = 11 relationships in one record); macronutrient intake and perceived stress (n = 8 relationships in one record); and food security and depression (n = 8 relationships in eight records from seven studies) were the most frequently examined relationships, the latter also being the most widely examined relationship of all relationships found.

3.5. Eating Disorders

Nine peer-reviewed, mostly cross-sectional records (2002–2011) examined eating disorders; five were open access. They included one pooled regional analysis on dieting behaviours and their correlates across nine countries [96]; five reports of school-based surveys on bulimic disorders, eating attitudes, and body image perceptions in Barbados, Trinidad, and Puerto Rico [97,98,99,100,101]; two medical-record reviews of anorexia and other eating disorder diagnoses in Curacao and Jamaica [102,103]; and one mixed-methods study exploring cultural influences on anorexia diagnoses in Curacao [104]. Together, they assessed incidence, prevalence, correlates, and contextual factors related to eating disorders in adolescents and adults across 12 Caribbean countries.

Except the Jamaica and Curacao studies which were secondary data analyses, the data collection tools included the following:

- To screen for anorexia and/or bulimia: Researchers own short surveys (n = 4 records); Eating Attitudes Test-26 [105] (n = 5); Bulimia Investigatory Test Edinburgh (BITE) [106] (n = 2); Bulimia Test-Revised (BULIT-R) [107] (n = 2); Eating Disorders Inventory (EDI) [108] (n = 1); and the Questionnaire for Eating and Weight problems-revised [109] (n = 1);

- To diagnose bulimia: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd edition, revised Bulimia Diagnostic Interview [110] (n = 1);

- To screen for any eating disorder: Drive-for-Thinness subscale of the Eating Disorder Inventory-2 [111] (n = 1).

Except for three studies of university students [97,100,101], authors reported a relatively low prevalence of potential eating disorders in the context of the protective factors of a “still traditional” culture [98] of healthy body size preferences and eating habits. Authors referred to the growing influence of Western ideals of thinness/beauty as a contributing factor to eating disorders, while one hypothesised that the influence may not be Western-specific per se but rather related to the process of any society’s complex socio-cultural development [104].

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary Findings and Evidence Gaps

Thirty-five records examined relationships between diet and mental health in the Caribbean between 2000 and 2024. Despite relatively limited human and infrastructural capacities, an increasing number of studies were conducted in a wide range of Caribbean countries (20 of 33 searched). While this might seem to reflect growing regional interest in the field, the low number of studies that examine this relationship as a primary research aim suggests the Caribbean to be at an early, exploratory stage of examination.

With respect to study design, the common use of cross-sectional design limits speculation on the direction of reported associations. Though five interventions were found, the collective strength of evidence is limited due to relatively small sample sizes and lack of control groups or randomisation. The low number of qualitative studies indicates a weak understanding of sociocultural beliefs about the diet–mental health relationship, including what might shape the relationship or its focus in academic research. Overall, studies were mostly epidemiological; there were no biological studies of mechanisms of action (for example, gut or neural inflammation, gut microbiome, or hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis) which could also deepen the regional evidence base on nutritional psychiatry. Finally, with respect to eating disorders, the evidence spans only up to 2011, deeming their findings possibly less relevant considering that Caribbean countries are vulnerable to rapid globalisation and it is argued that prevalence of eating attitudes and disorders may change over time [98].

Although a variety of diet and mental health variables were examined, the Jamaican Autism Study [71,72,73,74] skews the image of a strong Caribbean focus on autism when in fact its high count of relationships comes from this single study. It is unsurprising that perceived stress and depression were the most frequently and widely examined mental health variables, given the ubiquity of stress and its implications for both physical and mental health, and that depression is among the most common mental health disorders globally [112]. Yet two major mental health disorders were not reported - bipolar and schizoaffective disorders. While less prevalent than anxiety or depression, this is a significant evidence gap given their severity of symptoms, comparative difficulty in achieving remission, and the emerging evidence of effective nutritional interventions that may reduce their symptoms and burden of disease [17,113].

The most frequently and widely reported diet variables (fruits and vegetables, seafood and food security) are also unsurprising given the commonly purported protective role of fruits and vegetables in promoting adequate health [18,114], the cultural significance and abundance of seafood in Caribbean diets, and the rise in food insecurity in the region [31]. However, the low number of records examining processed foods and local foods specifically is important considering the Caribbean’s heavy reliance on processed food imports, and the vital role local foods could play in improving food sovereignty, food security and NCD risk profiles in the Caribbean [32,34,35,115]. Indigenous foods of the region have declined in availability since colonialism, but traditional plant-based foods, such as the West Indian cherry, mango, avocado, aloe, cassava, and breadfruit, not only have nutritional benefits, but also their production could improve food sovereignty and climate resilience of small island food systems [116,117].

Though not problematic to see diversity in variables examined across studies, the variation in data collection tools used limits both the comparability between settings and, in some cases, the validity of findings. Variation could obscure observed associations when comparing diverse contexts [59]. For example, the variability of tools used to assess food security is relevant considering that its impact on mental health is not only from biological effects of poor nutrition but also because of the stress caused by being food insecure, with accompanying emotions and behaviours which can be culturally bound [21,118]. Suicide was the only variable examined by the same standardised tool, namely the WHO Global School Based Survey. However, validity of findings is questionable as the survey often used a single yes/no question for assessment (e.g., “During the past 12 months, did you ever seriously consider attempting suicide?”) [68]. This inconsistency in tools is perhaps driven by the relative lack of measures (particularly mental health measures) validated for use in the Caribbean, which raises risk for error in interpretation of both research and clinical findings [119,120]. The emerging field of global mental health emphasises the significance of cultural variation in conceptualisations of mental health, which can influence both the interpretation and measurement of mental health constructs and questions the applicability of standardised assessment tools across diverse settings [26,121]. The same can be said for diet; measuring dietary intake with standard tools such as food frequency questionnaires is challenged by cultural differences in food preferences and varying access to foods, which may not be fully captured. The omission of culturally specific foods can limit the accuracy of dietary assessment, particularly amongst underrepresented groups, potentially contributing to gaps in understanding diet-related health outcomes [27].

4.2. Future Research Focus

A more targeted systematic review to follow this scoping exercise is recommended to examine this existing data. Potential areas of focus can include the most widely reported relationships—‘food security and depression’, and ‘food security and suicide ideation/planning/attempt’. Additionally, risk of bias assessments of systematic reviews will elucidate the strength of existing evidence.

Secondly, conducting studies with the primary aim of examining the relationship between diet and mental health could deepen understanding of nutritional psychiatry in the region. Study designs that promote enquiry beyond the cross-sectional observational study are warranted. Qualitative and mixed-methods studies can provide insight into why research in this area might be lacking and what cultural beliefs and understandings exist about the relationship. Hoek et al., for example, found sociocultural factors to be associated with the incidence of anorexia nervosa in Curacao, and they call for a deeper understanding to support their explanatory hypotheses on how settings influence the development of eating disorders [102]. Intervention studies would also benefit the regional evidence base of nutritional psychiatry, perhaps focusing on plant-based and ketogenic diets and including more severe mental health conditions given the growing amount of evidence in support of these in other settings [9,12,14]. Interventions promoting fruit and vegetable intake might be particularly relevant for Caribbean populations given existing low intake and potential benefit for both physical and mental health [36]. Further, understanding contextual factors such as cultural food preferences and local food availability and accessibility could complement intervention work. Researchers should also consider examining processed food and local food consumption and use dietary diversity as a proxy for nutrient adequacy, given their evidenced impact on mental health in other countries and considering the Caribbean’s narrowing local foodscape and dependency on (often processed) food imports [117,122]. Likewise, researchers should facilitate ethical inclusion of people with severe mental illness, such as those with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, to increase their representation in needed research [123]. Though, researchers must acknowledge the threat of Neyman bias arising from the potential of persons with severe mental health disproportionately refusing to participate in or withdrawing from studies, and also the difficulty in recruiting from other hard-to-reach groups (i.e., low-income or rural dwellers). Finally, social desirability bias is also at play in any self-report of diet, where participants might erroneously report healthier foods than those that are truly consumed.

With respect to tools, researchers are encouraged to use culturally appropriate data collection tools or conduct validation studies in Caribbean settings to prevent the misappropriation of WEIRD-developed tools (‘Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich and Democratic’ contexts) [124]. For instance, the Beck Depression Inventory II has been validated in Jamaican university students [125]; Perceived Stress Scale and Brief Resilient Coping Scale were validated in health professional students across four Caribbean countries [124]; and EQ-5D-5L for self-reported health was validated in adults in Barbados and Jamaicas [126]. Yet caution must be taken in applying these tools across all ages and countries given the specificity of study samples. Also, any cultural adaptation to standardised tools must also appreciate the ‘tailor locally, retain globally’ principle in measurement tool adaptation. While culturally adapting standardised tools is essential, the process must be balanced to preserve enough of the original structure to allow for meaningful cross-country comparisons [127]. A recent example is the adaptation and pilot of the INTAKE24 dietary intake data collection tool, which was originally developed for the United Kingdom context. Researchers from the Global Community Food and Health Project adapted the diet recall tool for application in St. Vincent and the Grenadines, adding Caribbean dishes and local foods to ensure cultural applicability and validity (ongoing study; manuscript in review) [128]. Food frequency questionnaires can also be adapted to include context-specific foods and use more branching logic with open-answered questions to capture these foods in a systematic way [27].

Finally, researchers are encouraged to publish in more open-source platforms and mental health-focused publications to promote further awareness and advocacy in mental health arenas where, perhaps, knowledge on the potential impact of diet on mental health may be less acknowledged.

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, this scoping review is the first to attempt to map research on diet and mental health relationships in the Caribbean. It provides a broad snapshot of existing research to guide focused systematic reviews and primary studies on the topic. Its broad search strategy encompassing eleven databases and the inclusion of review articles during screening maximised sensitivity to capture as many relevant studies as possible. However, as expected within scoping review work, researchers were challenged by deciding on eligibility criteria for the two variables. While definitions of mental health were kept broad, researchers were forced to draw a line between what constitutes ‘mental health’ versus ‘overall brain health’, especially considering the physiological connection between physical and mental health and the shared purported pathophysiology of diet’s impact on both, through oxidative stress and systemic inflammation, for example [3]. It is acknowledged that broader definitions of variables might identify further studies.

5. Conclusions

Research examining diet and mental health relationships is steadily increasing in Caribbean contexts. However, research is limited in study design (mostly cross-sectional); is thinly spread across most variables; and often uses data collection tools that may not be culturally appropriate. Targeted systematic reviews of the identified diet and mental health variables are required to better understand the extent of existing evidence in the region. Experimental and qualitative studies that primarily aim to explore the impact of diet on mental health outcomes and related beliefs of such, using culturally appropriate, data collection tools, are warranted. Diet and mental health are cultural phenomena of populations and future examinations should be performed with a cultural lens to elucidate more on if and how culture interacts with findings.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nu18010058/s1, Table S1: Database search terms (using syntax appropriate for PubMed); Table S2: List of references of 44 included records.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, C.R.B. and M.M.; methodology, C.R.B., M.C. and M.M.; software, C.R.B.; formal analysis, C.R.B.; investigation, C.R.B., E.H., K.P. and C.H.; data curation, C.R.B.; writing—original draft preparation, C.R.B.; writing—review and editing, C.R.B., E.H., K.P., C.H., M.C. and M.M.; supervision, M.M.; project administration, C.R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study. Data Sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the dedicated guidance of Nigel Unwin and Cornelia Guell in working to shape the focus of this work. For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EQ-5D-5L | EuroQol-5 Dimensions-5 Levels |

| LMIC | Low-and-Middle-Income Country |

| NCD | Non-communicable disease |

| SIDS | Small island developing state |

| WEIRD | Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich and Democratic |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- World Health Organization. World Mental Health Report: Transforming Mental Health for All; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sparling, T.M.; Cheng, B.; Deeney, M.; Santoso, M.V.; Pfeiffer, E.; Emerson, J.A.; Amadi, F.M.; Mitu, K.; Corvalan, C.; Verdeli, H.; et al. Global Mental Health and Nutrition: Moving Toward a Convergent Research Agenda. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 722290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, B.J.; Rucklidge, J.J.; Romijn, A.; McLeod, K. The Emerging Field of Nutritional Mental Health: Inflammation, the Microbiome, Oxidative Stress, and Mitochondrial Function. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 3, 964–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliby, D.; Simpson, C.A.; Lawrence, A.S.; Schwartz, O.S.; Haslam, N.; Simmons, J.G. Associations between Diet Quality and Anxiety and Depressive Disorders: A Systematic Review. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2023, 14, 100629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devranis, P.; Vassilopoulou, Ε.; Tsironis, V.; Sotiriadis, P.M.; Chourdakis, M.; Aivaliotis, M.; Tsolaki, M. Mediterranean Diet, Ketogenic Diet or MIND Diet for Aging Populations with Cognitive Decline: A Systematic Review. Life 2023, 13, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grajek, M.; Krupa-Kotara, K.; Białek-Dratwa, A.; Sobczyk, K.; Grot, M.; Kowalski, O.; Staśkiewicz, W. Nutrition and Mental Health: A Review of Current Knowledge about the Impact of Diet on Mental Health. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 943998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, M.M.; Davis, J.A.; Beattie, S.; Gómez-Donoso, C.; Loughman, A.; O’Neil, A.; Jacka, F.; Berk, M.; Page, R.; Marx, W.; et al. Ultraprocessed Food and Chronic Noncommunicable Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 43 Observational Studies. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejtahed, H.-S.; Mardi, P.; Hejrani, B.; Mahdavi, F.S.; Ghoreshi, B.; Gohari, K.; Heidari-Beni, M.; Qorbani, M. Association between Junk Food Consumption and Mental Health Problems in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventriglio, A.; Sancassiani, F.; Contu, M.P.; Latorre, M.; Di Slavatore, M.; Fornaro, M.; Bhugra, D. Mediterranean Diet and Its Benefits on Health and Mental Health: A Literature Review. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2020, 16, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lv, M.-R.; Wei, Y.-J.; Sun, L.; Zhang, J.-X.; Zhang, H.-G.; Li, B. Dietary Patterns and Depression Risk: A Meta-Analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 253, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-H.; Gao, X.; Na, M.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Mitchell, D.C.; Jensen, G.L. Dietary Pattern, Diet Quality, and Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2020, 78, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietch, D.M.; Kerr-Gaffney, J.; Hockey, M.; Marx, W.; Ruusunen, A.; Young, A.H.; Berk, M.; Mondelli, V. Efficacy of Low Carbohydrate and Ketogenic Diets in Treating Mood and Anxiety Disorders: Systematic Review and Implications for Clinical Practice. BJPsych Open 2023, 9, e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-McGill, K.J.; Bresnahan, R.; Levy, R.G.; Cooper, P.N. Ketogenic Diets for Drug-Resistant Epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 6, CD001903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.J.; Fournakis, N.; Ellison, J. Ketogenic Diet for the Treatment and Prevention of Dementia: A Review. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2021, 34, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteley, V.J.; Martin-McGill, K.J.; Carroll, J.H.; Taylor, H.; Schoeler, N.E. Ketogenic Dietitians Research Network (KDRN) Nice to Know: Impact of NICE Guidelines on Ketogenic Diet Services Nationwide. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 33, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molendijk, M.; Molero, P.; Ortuño Sánchez-Pedreño, F.; Van der Does, W.; Angel Martínez-González, M. Diet Quality and Depression Risk: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 226, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, F.C.; Oliveira, M.; Bruna, D.M.M.; Berk, M.; Brietzke, E.; Jacka, F.N.; Lafer, B. Nutrition and Bipolar Disorder: A Systematic Review. Nutr. Neurosci. 2023, 26, 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Głąbska, D.; Guzek, D.; Groele, B.; Gutkowska, K. Fruit and Vegetable Intake and Mental Health in Adults: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iguacel, I.; Huybrechts, I.; Moreno, L.A.; Michels, N. Vegetarianism and Veganism Compared with Mental Health and Cognitive Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2021, 79, 361–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neil, A.; Quirk, S.E.; Housden, S.; Brennan, S.L.; Williams, L.J.; Pasco, J.A.; Berk, M.; Jacka, F.N. Relationship Between Diet and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, e31–e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourmotabbed, A.; Moradi, S.; Babaei, A.; Ghavami, A.; Mohammadi, H.; Jalili, C.; Symonds, M.E.; Miraghajani, M. Food Insecurity and Mental Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 1778–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montgomery, L.; McNulty, H.; Ward, M.; Hoey, L.; Patterson, C.; Hughes, C.F. Effect of Specific Nutrients or Dietary Patterns on Mental Health Outcomes in Adults; A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses of Nutrition Interventions. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2024, 83, E277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adan, R.A.H.; van der Beek, E.M.; Buitelaar, J.K.; Cryan, J.F.; Hebebrand, J.; Higgs, S.; Schellekens, H.; Dickson, S.L. Nutritional Psychiatry: Towards Improving Mental Health by What You Eat. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019, 29, 1321–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparling, T.M.; Deeney, M.; Cheng, B.; Han, X.; Lier, C.; Lin, Z.; Offner, C.; Santoso, M.V.; Pfeiffer, E.; Emerson, J.A.; et al. Systematic Evidence and Gap Map of Research Linking Food Security and Nutrition to Mental Health. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitoun, R.; Sander, S.G.; Masque, P.; Perez Pijuan, S.; Swarzenski, P.W. Review of the Scientific and Institutional Capacity of Small Island Developing States in Support of a Bottom-up Approach to Achieve Sustainable Development Goal 14 Targets. Oceans 2020, 1, 109–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summerfield, D. Afterword: Against “Global Mental Health”. Transcult. Psychiatry 2012, 49, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassine, H.N.; Samieri, C.; Livingston, G.; Glass, K.; Wagner, M.; Tangney, C.; Plassman, B.L.; Ikram, M.A.; Voigt, R.M.; Gu, Y.; et al. Nutrition State of Science and Dementia Prevention: Recommendations of the Nutrition for Dementia Prevention Working Group. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2022, 3, e501–e512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agricultural Organization; International Fund for Agricultural Development; UNICEF; World Food Programme; World Health Organization. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023: Urbanization, Agrifood Systems Transformation and Healthy Diets Across the Rural–Urban Continuum; The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World; Food and Agricultural Organization: Rome, Italy, 2023; ISBN 978-92-5-137226-5. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases and Mental Health in Small Island Developing States; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. List of SIDS. Available online: https://www.un.org/ohrlls/content/list-sids (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization; International Fund for Agricultural Development; Pan American Health Organization; World Food Programme; UNICEF. Latin America and the Caribbean–Regional Overview of Food Security and Nutrition 2021: Statistics and Trends, 1st ed.; Food and Agriculture Organization: Santiago, Chile, 2021; ISBN 978-92-5-135261-8. [Google Scholar]

- Guell, C.; Saint Ville, A.; Anderson, S.G.; Murphy, M.M.; Iese, V.; Kiran, S.; Hickey, G.M.; Unwin, N. Small Island Developing States: Addressing the Intersecting Challenges of Non-Communicable Diseases, Food Insecurity, and Climate Change. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2024, 12, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, E.; Singh, S.J.; McCordic, C.; Pittman, J. Food Security Challenges and Options in the Caribbean: Insights from a Scoping Review. Anthr. Sci. 2022, 1, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkin, B.M.; Adair, L.S.; Ng, S.W. Global Nutrition Transition and the Pandemic of Obesity in Developing Countries. Nutr. Rev. 2012, 70, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgenie, D.; Hutchinson, S.D.; Muhammad, A. Dynamic Analysis of Caribbean Food Import Demand. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 15, 100989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Nutrition Report Country Nutrition Profiles: Caribbean. Available online: https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/latin-america-and-caribbean/caribbean/ (accessed on 8 November 2023).

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 8 November 2023).

- World Bank Group. The Economic Impact of Non-Communicable Diseases in the Caribbean. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/caribbean/brief/the-economic-impact-of-non-communicable-diseases-in-the-caribbean (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. GBD Compare. Available online: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/ (accessed on 8 November 2023).

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. GBD Foresight Visualization. Available online: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-foresight (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- World Health Organization. Suicide Mortality Rate (per 100,000 Population). Available online: https://data.who.int/indicators/i/F08B4FD/16BBF41 (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- World Health Organization. Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2030; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson, G. The Hidden Pandemic. West Indian Med. J. 2025, 72, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Healthy Caribbean Youth. Caribbean Youth Mental Health Call to Action. Available online: https://www.healthycaribbean.org/caribbean-youth-mental-health-call-to-action/ (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Pan American Health Organization. 2023 Bridgetown Declaration on NCDs and Mental Health; Pan American Health Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pan American Health Organization. A New Agenda for Mental Health in the Americas: Report of the Pan American Health Organization High-Level Commission on Mental Health and COVID-19; Pan American Health Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun, H.L.; Levac, D.; O’Brien, K.K.; Straus, S.; Tricco, A.C.; Perrier, L.; Kastner, M.; Moher, D. Scoping Reviews: Time for Clarity in Definition, Methods, and Reporting. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 1291–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Brown, C.R.; Hambleton, I.; Hercules, S.M.; Unwin, N.; Murphy, M.M.; Nigel Harris, E.; Wilks, R.; MacLeish, M.; Sullivan, L.; Sobers-Grannum, N.; et al. Social Determinants of Prostate Cancer in the Caribbean: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.R.; Hambleton, I.R.; Hercules, S.M.; Alvarado, M.; Unwin, N.; Murphy, M.M.; Harris, E.N.; Wilks, R.; MacLeish, M.; Sullivan, L.; et al. Social Determinants of Breast Cancer in the Caribbean: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Equity Health 2017, 16, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.R.; Hambleton, I.R.; Sobers-Grannum, N.; Hercules, S.M.; Unwin, N.; Nigel Harris, E.; Wilks, R.; MacLeish, M.; Sullivan, L.; Murphy, M.M.; et al. Social Determinants of Depression and Suicidal Behaviour in the Caribbean: A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haroz, E.E.; Ritchey, M.; Bass, J.K.; Kohrt, B.A.; Augustinavicius, J.; Michalopoulos, L.; Burkey, M.D.; Bolton, P. How Is Depression Experienced around the World? A Systematic Review of Qualitative Literature. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 183, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, P.D.; Rickards, H.; Zeman, A.Z.J. Time to End the Distinction between Mental and Neurological Illnesses. BMJ 2012, 344, e3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)—A Metadata-Driven Methodology and Workflow Process for Providing Translational Research Informatics Support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, G.; Beard, J. Recent Advances in Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy for Eating Disorders (CBT-ED). Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2024, 26, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.D. Food Insecurity and Mental Health Status: A Global Analysis of 149 Countries. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 53, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racine, E.F.; Jemison, K.; Huber, L.R.; Arif, A.A. The Well-Being of Children in Food-Insecure Households: Results from The Eastern Caribbean Child Vulnerability Study 2005. Public Health Nutr. 2008, 12, 1443–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Brockman, J.L.; Hromi-Fiedler, A.; Galusha, D.; Oladele, C.; Acosta, L.; Adams, O.P.; Maharaj, R.G.; Nazario, C.M.; Nunez, M.; Nunez-Smith, M.; et al. Risk Factors for Household Food Insecurity in the Eastern Caribbean Health Outcomes Research Network Cohort Study. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1269857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltzer, K.; Pengpid, S.; Sodi, T.; Mantilla Toloza, S.C. Happiness and Health Behaviours among University Students from 24 Low, Middle and High Income Countries. J. Psychol. Afr. 2017, 27, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltzer, K.; Pengpid, S. Correlates of Healthy Fruit and Vegetable Diet in Students in Low, Middle and High Income Countries. Int. J. Public Health 2015, 60, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertl, M.M.; Trapp, S.K.; Alzueta, E.; Baker, F.C.; Perrin, P.B.; Caffarra, S.; Yüksel, D.; Ramos-Usuga, D.; Arango-Lasprilla, J.C. Trauma-Related Distress During the COVID-19 Pandemic in 59 Countries. Couns. Psychol. 2022, 50, 306–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benites-Zapata, V.A.; Urrunaga-Pastor, D.; Solorzano-Vargas, M.L.; Herrera-Añazco, P.; Uyen-Cateriano, A.; Bendezu-Quispe, G.; Toro-Huamanchumo, C.J.; Hernandez, A.V. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Food Insecurity in Latin America and the Caribbean during the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pengpid, S.; Peltzer, K. Skipping Breakfast and Its Association with Health Risk Behaviour and Mental Health Among University Students in 28 Countries. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2020, 13, 2889–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pengpid, S.; Peltzer, K. Food Insecurity Is Associated with Multiple Psychological and Behavioural Problems among Adolescents in Five Caribbean Countries. Psychol. Health Med. 2023, 28, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwangu, M.; Siziya, S.; Mulenga, D.; Mazyanga, M.; Njunju, E. Correlates of Suicidal Ideation among School-Going Adolescents in Bahamas. Int. Public Health J. 2017, 9, 393–399. [Google Scholar]

- Marcos Plasencia, L.M.; Rojas Massipe, E. Presentación de Un Caso de Aplicación de La Dieta Cetogénica En La Epilepsia Refractaria. Rev. Cuba. Pediatría 2007, 79. [Google Scholar]

- Mulenga, D.; Siziya, S.; Mazaba, M.L.; Kwangu, M.; Njunju, E.M. Correlates of Suicidal Ideation among In-School Adolescents in Trinidad and Tobago. Int. Public Health J. 2017, 9, 437. [Google Scholar]

- Rahbar, M.H.; Samms-Vaughan, M.; Ardjomand-Hessabi, M.; Loveland, K.A.; Dickerson, A.S.; Chen, Z.; Bressler, J.; Shakespeare-Pellington, S.; Grove, M.L.; Bloom, K.; et al. The Role of Drinking Water Sources, Consumption of Vegetables and Seafood in Relation to Blood Arsenic Concentrations of Jamaican Children with and without Autism Spectrum Disorders. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 433, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbar, M.H.; Samms-Vaughan, M.; Dickerson, A.S.; Loveland, K.A.; Ardjomand-Hessabi, M.; Bressler, J.; Shakespeare-Pellington, S.; Grove, M.L.; Pearson, D.A.; Boerwinkle, E. Blood Manganese Concentrations in Jamaican Children with and without Autism Spectrum Disorders. Environ. Health 2014, 13, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbar, M.H.; Samms-Vaughan, M.; Loveland, K.A.; Ardjomand-Hessabi, M.; Chen, Z.; Bressler, J.; Shakespeare-Pellington, S.; Grove, M.L.; Bloom, K.; Pearson, D.A.; et al. Seafood Consumption and Blood Mercury Concentrations in Jamaican Children With and Without Autism Spectrum Disorders. Neurotox. Res. 2013, 23, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbar, M.H.; Samms-Vaughan, M.; Dickerson, A.S.; Loveland, K.A.; Ardjomand-Hessabi, M.; Bressler, J.; Lee, M.; Shakespeare-Pellington, S.; Grove, M.L.; Pearson, D.A.; et al. Role of Fruits, Grains, and Seafood Consumption in Blood Cadmium Concentrations of Jamaican Children with and without Autism Spectrum Disorder. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2014, 8, 1134–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyanagi, A.; Stubbs, B.; Oh, H.; Veronese, N.; Smith, L.; Haro, J.M.; Vancampfort, D. Food Insecurity (Hunger) and Suicide Attempts among 179,771 Adolescents Attending School from 9 High-Income, 31 Middle-Income, and 4 Low-Income Countries: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 248, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siziya, S.; Njunju, E.M.; Kwangu, M.; Mulenga, D.; Mazaba-Liwewe, M. Suicidal Ideation in Jamaica. In Suicide: A Global View on Suicidal Ideation Among Adolescents; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Albanese, E.; Dangour, A.D.; Uauy, R.; Acosta, D.; Guerra, M.; Guerra, S.S.G.; Huang, Y.; Jacob, K.S.; de Rodriguez, J.L.; Noriega, L.H.; et al. Dietary Fish and Meat Intake and Dementia in Latin America, China, and India: A 10/66 Dementia Research Group Population-Based Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 90, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, E.; Lombardo, F.L.; Dangour, A.D.; Guerra, M.; Acosta, D.; Huang, Y.; Jacob, K.S.; Llibre Rodriguez, J.d.J.; Salas, A.; Schönborn, C.; et al. No Association between Fish Intake and Depression in over 15,000 Older Adults from Seven Low and Middle Income Countries—the 10/66 Study. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustus, E.; Granderson, I.; Rocke, K.D. The Impact of a Ketogenic Dietary Intervention on the Quality of Life of Stage II and III Cancer Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial in the Caribbean. Nutr. Cancer 2020, 73, 1590–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewis, A.; Wutich, A.; Galvin, M.; Lachaud, J. Localizing Syndemics: A Comparative Study of Hunger, Stigma, Suffering, and Crime Exposure in Three Haitian Communities. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 295, 113031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celeste-Villalvir, A.; Then-Paulino, A.; Armenta, G.; Jimenez-Paulino, G.; Palar, K.; Wallace, D.D.; Derose, K.P. Exploring Feasibility and Acceptability of an Integrated Urban Gardens and Peer Nutritional Counselling Intervention for People with HIV in the Dominican Republic. Public Health Nutr. 2023, 26, 3134–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleret de Langavant, L.; Roze, E.; Petit, A.; Tressières, B.; Gharbi-Meliani, A.; Chaumont, H.; Michel, P.P.; Bachoud-Lévi, A.-C.; Remy, P.; Edragas, R.; et al. Annonaceae Consumption Worsens Disease Severity and Cognitive Deficits in Degenerative Parkinsonism. Mov. Disord. 2022, 37, 2355–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DaSantos, A.; Goddard, C.; Ragoobirsingh, D. Self-Care Adherence and Affective Disorders in Barbadian Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. AIMS Public Health 2021, 9, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabián, C.; Pagán, I.; Ríos, J.L.; Betancourt, J.; Cruz, S.Y.; González, A.M.; Palacios, C.; González, M.J.; Rivera-Soto, W.T. Dietary Patterns and Their Association with Sociodemographic Characteristics and Perceived Academic Stress of College Students in Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico Health Sci. J. 2013, 32, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffers, N.K.; Wilson, D.; Tappis, H.; Bertrand, D.; Veenema, T.; Glass, N. Experiences of Pregnant Women Exposed to Hurricanes Irma and Maria in the US Virgin Islands: A Qualitative Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachaud, J.; Hruschka, D.J.; Kaiser, B.N.; Brewis, A. Agricultural Wealth Better Predicts Mental Wellbeing than Market Wealth among Highly Vulnerable Households in Haiti: Evidence for the Benefits of a Multidimensional Approach to Poverty. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2019, 32, e23328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaMonaca, K.; Desai, M.; May, J.P.; Lyon, E.; Altice, F.L. Prisoner Health Status at Three Rural Haitian Prisons. Int. J. Prison. Health 2018, 14, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Cepero, A.; O’Neill, J.; Tamez, M.; Falcón, L.M.; Tucker, K.L.; Rodríguez-Orengo, J.F.; Mattei, J. Associations Between Perceived Stress and Dietary Intake in Adults in Puerto Rico. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, 762–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, I. Examining Dominican Folk Knowledge and Practices Used as Self-Care during Crises in the Dominican Republic. Ph.D. Thesis, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, Chicago, IL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rocke, K.; Roopchand, X. Predictors for Depression and Perceived Stress among a Small Island Developing State University Population. Psychol. Health Med. 2020, 26, 1108–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simeone, R.M.; House, L.D.; Salvesen von Essen, B.; Kortsmit, K.; Hernandez Virella, W.; Vargas Bernal, M.I.; Galang, R.R.; D’Angelo, D.V.; Shapiro-Mendoza, C.K.; Ellington, S.R. Pregnant Women’s Experiences During and After Hurricanes Irma and Maria, Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, Puerto Rico, 2018. Public Health Rep. 2023, 138, 916–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.P.; Chang, S.M.; Powell, C.A.; Simonoff, E.; Grantham-McGregor, S.M. Effects of Psychosocial Stimulation and Dietary Supplementation in Early Childhood on Psychosocial Functioning in Late Adolescence: Follow-up of Randomised Controlled Trial. BMJ 2006, 333, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.P.; Chang, S.M.; Vera-Hernández, M.; Grantham-McGregor, S. Early Childhood Stimulation Benefits Adult Competence and Reduces Violent Behavior. Pediatrics 2011, 127, 849–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, J.R.M.; Kelleher, M.J.; Kellett, J.M.; Gourlay, A.J.; Gurland, B.J.; Fleiss, J.L.; Sharpe, L. A Semi-Structured Clinical Interview for the Assessment of Diagnosis and Mental State in the Elderly: The Geriatric Mental State Schedule: I. Development and Reliability. Psychol. Med. 1976, 6, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global School-Based Student Health Survey. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/surveillance/systems-tools/global-school-based-student-health-survey (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- McGuire, M.T.; Story, M.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Halcon, L.; Campbell-Forrester, S.; Blum, R.W. Prevalence and Correlates of Weight-Control Behaviors among Caribbean Adolescent Students. J. Adolesc. Health 2002, 31, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, S.D.; Dookeran, S.S.; Ragbir, K.K.; Dalrymple, N. Body Image Perception and the Risk of Unhealthy Behaviours among University Students. West Indian Med. J. 2009, 58, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bhugra, D.; Mastrogianni, A.; Maharajh, H.; Harvey, S. Prevalence of Bulimic Behaviours and Eating Attitudes in Schoolgirls from Trinidad and Barbados. Transcult. Psychiatry 2003, 40, 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramberan, K.; Austin, M.; Nichols, S. Ethnicity, Body Image Perception and Weight-Related Behaviour among Adolescent Females Attending Secondary School in Trinidad. West Indian Med. J. 2006, 55, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Rodríguez, M.L.; Franko, D.L.; Matos-Lamourt, A.; Bulik, C.M.; Von Holle, A.; Cámara-Fuentes, L.R.; Rodríguez-Angleró, D.; Cervantes-López, S.; Suárez-Torres, A. Eating Disorder Symptomatology: Prevalence among Latino College Freshmen Students. J. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 66, 666–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Rodríguez, M.L.; Sala, M.; Von Holle, A.; Unikel, C.; Bulik, C.M.; Cámara-Fuentes, L.; Suárez-Torres, A. A Description of Disordered Eating Behaviors in Latino Males. J. Am. Coll. Health 2011, 59, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoek, H.W.; van Harten, P.N.; Hermans, K.M.E.; Katzman, M.A.; Matroos, G.E.; Susser, E.S. The Incidence of Anorexia Nervosa on Curaçao. Am. J. Psychiatry 2005, 162, 748–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, V.O.; Gardner, J.M. Presence of Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa in Jamaica. West Indian Med. J. 2002, 51, 32–34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Katzman, M.A.; Hermans, K.M.E.; Hoeken, D.V.; Hoek, H.W. Not Your “Typical Island Woman”: Anorexia Nervosa Is Reported Only in Subcultures in Curaçao. Cult. Med. Psychiatry 2004, 28, 463–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, D.M.; Olmsted, M.P.; Bohr, Y.; Garfinkel, P.E. The Eating Attitudes Test: Psychometric Features and Clinical Correlates. Psychol. Med. 1982, 12, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, M.; Freeman, C.P.L. A Self-Rating Scale for Bulimia the ‘BITE’. Br. J. Psychiatry 1987, 150, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelen, M.H.; Farmer, J.; Wonderlich, S.; Smith, M. A Revision of the Bulimia Test: The BULIT—R. Psychol. Assess. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1991, 3, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, D.M.; Olmstead, M.P.; Polivy, J. Development and Validation of a Multidimensional Eating Disorder Inventory for Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1983, 2, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spritzer, R.; Yanovski, S.; Marcus, M. Questionnaire on Eating and Weight Patterns–Revised (QEWP-R). Obes. Res. 1993, 1, 319–324. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Garner, D. Eating Disorder Inventory-2: Professional Manual; Psychological Assessment Resources: Odessa, FL, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Candeias, A.A.; Galindo, E.; Reschke, K.; Bidzan, M.; Stueck, M. The Interplay of Stress, Health, and Well-Being: Unraveling the Psychological and Physiological Processes. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1471084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onaolapo, O.J.; Onaolapo, A.Y. Nutrition, Nutritional Deficiencies, and Schizophrenia: An Association Worthy of Constant Reassessment. World J. Clin. Cases 2021, 9, 8295–8311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devirgiliis, C.; Guberti, E.; Mistura, L.; Raffo, A. Effect of Fruit and Vegetable Consumption on Human Health: An Update of the Literature. Foods 2024, 13, 3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, E.; Brown, C.; Wou, C.; Vogliano, C.; Guell, C.; Unwin, N. Health and Other Impacts of Community Food Production in Small Island Developing States: A Systematic Scoping Review. Pan Am. J. Public Health 2018, 42, e176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrero, A.; Mattei, J. Reclaiming Traditional, Plant-Based, Climate-Resilient Food Systems in Small Islands. Lancet Planet. Health 2022, 6, e171–e179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St. John, J. Improving Dietary Diversity in the Caribbean Community. Rev. Panam. Salud Pública 2022, 46, e58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, J.; Frongillo, E.A.; Rogers, B.L.; Webb, P.; Wilde, P.E.; Houser, R. Commonalities in the Experience of Household Food Insecurity across Cultures: What Are Measures Missing? J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 1438S–1448S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, M.C.; Levitch, A.; Robinson, J.; Sweeney, T.W. Psychometric Concerns Associated with Using Psychological Assessment Tools from Eurocentric Countries in Anglophone Caribbean Nations. Caribb. J. Psychol. 2018, 10, 91. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, M.H.; Gromer-Thomas, J.; Khan, K.; Sa, B.; Lashley, P.M.; Cohall, D.; Chin, C.E.; Pierre, R.B.; Ojeh, N.; Bharatha, A.; et al. Measuring Caribbean Stress and Resilient Coping: Psychometric Properties of the PSS-10 and BRCS in a Multi-Country Study during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Camb. Prisms Glob. Ment. Health 2024, 11, e77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bass, J.K.; Bolton, P.A.; Murray, L.K. Do Not Forget Culture When Studying Mental Health. Lancet 2007, 370, 918–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazloomi, S.N.; Talebi, S.; Mehrabani, S.; Bagheri, R.; Ghavami, A.; Zarpoosh, M.; Mohammadi, H.; Wong, A.; Nordvall, M.; Kermani, M.A.H.; et al. The Association of Ultra-Processed Food Consumption with Adult Mental Health Disorders: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of 260,385 Participants. Nutr. Neurosci. 2023, 26, 913–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, E.; Benjamin-Thomas, T.E.; Sithambaram, A.; Shankar, J.; Chen, S.-P. Participatory Action Research Among People With Serious Mental Illness: A Scoping Review. Qual. Health Res. 2024, 34, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gromer, J.; Campbell, M.H. Measuring Stress in Caribbean University Students: Validation of the PSS-10 in Barbados. Caribb. J. Psychol. 2018, 10, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipps, G.E.; Lowe, G.A.; Young, R. Validation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II in a Jamaican University Student Cohort. West Indian Med. J. 2007, 56, 404–408. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, H.; Janssen, M.F.; La Foucade, A.; Boodraj, G.; Wharton, M.; Castillo, P. EQ-5D Self-Reported Health in Barbados and Jamaica with EQ-5D-5L Population Norms for the English-Speaking Caribbean. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2021, 19, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidani, S.; Guruge, S.; Miranda, J.; Ford-Gilboe, M.; Varcoe, C. Cultural Adaptation and Translation of Measures: An Integrated Method. Res. Nurs. Health 2010, 33, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Projects: Global Community Food for Human Nutrition and Planetary Health in Small Islands (Global CFaH). Available online: https://communityfoodplanetaryhealth.org/our-projects (accessed on 9 November 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.