Abstract

Diabetes and obesity are globally prevalent metabolic disorders posing significant public health challenges. The effective management of these conditions requires integrated and personalized strategies. This study conducted a systematic literature review, identifying 335 relevant papers, with 129 core articles selected after screening for duplicates and irrelevant studies. The focus of the study is on the synergistic roles of functional foods, microbiotics, and nutrigenomics. Functional foods, including phytochemicals (e.g., polyphenols and dietary fibers), zoochemicals (e.g., essential fatty acids), and bioactive compounds from macrofungi, exhibit significant potential in enhancing insulin sensitivity, regulating lipid metabolism, reducing inflammatory responses, and improving antioxidant capacity. Additionally, the critical role of gut microbiota in metabolic health is highlighted, as its interaction with functional foods facilitates the modulation of metabolic pathways. Nutrigenomics, encompassing nutrigenetics and genomics, reveals how genetic variations (e.g., single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)) influence dietary responses and gene expression, forming a feedback loop between dietary habits, genetic variations, gut microbiota, and metabolic health. This review integrates functional foods, gut microbiota, and genetic insights to propose comprehensive and sustainable personalized nutrition interventions, offering novel perspectives for preventing and managing type 2 diabetes and obesity. Future clinical studies are warranted to validate the long-term efficacy and safety of these strategies.

1. Introduction

The escalating prevalence of diabetes and obesity has intensified the search for innovative, integrative strategies for prevention and management. The NCD Risk Factor Collaboration reported that over 1 billion people globally were obese in 2022, with nearly 0.3 billion classified as overweight or obese [1]. The prevalence of obesity among adults in the South-East Asia Region was about 6%, while in the Western Pacific Region, it was approximately 8%. The primary concern with obesity is its strong association with chronic metabolic disorders, including insulin resistance (IR), cardiovascular diseases, and type 2 diabetes (T2DM) [2].

In 2021, an estimated 537 million people globally were living with diabetes, including approximately 206 million adults in the South-East Asia Region (8.7%) and 206 million in the Western Pacific Region (10.9%). These numbers are projected to rise significantly, reaching 643 million globally by 2030 and 783 million by 2045, with a 69% increase anticipated in the South-East Asia Region and similar growth trends in the Western Pacific Region [3]. Beyond conventional pharmaceutical interventions, dietary strategies have emerged as pivotal approaches in health management, emphasizing the roles of functional foods, probiotics, and personalized nutrition guided by advancements in nutrigenomics and nutrigenetics [4]. Functional foods, enriched with bioactive compounds, offer health benefits that extend beyond basic nutrition by modulating physiological functions. Probiotics, as beneficial microorganisms, contribute significantly to gut health and are associated with various systemic health benefits [5]. Personalized nutrition, leveraging insights from nutrigenomics and nutrigenetics, provides tailored dietary recommendations based on individual genetic profiles, recognizing the critical influence of genetic variation on nutrient metabolism and dietary responses [6]. These disciplines explore the intricate interactions between diet, the gut microbiome, and individual genetic profiles, offering insights into metabolic modulation and the potential to mitigate metabolic disorders.

Functional foods, which offer health benefits beyond basic nutrition, include a wide range of bioactive components such as fiber, polyphenols, and omega-3 fatty acids. These foods have been shown to significantly influence the metabolic processes associated with obesity and T2DM by improving insulin sensitivity, regulating blood sugar levels, and modulating fat metabolism [7,8]. Fiber, for example, promotes satiety, regulates blood glucose, and reduces IR, while polyphenols exhibit antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties that help to mitigate oxidative stress and inflammation—key contributors to metabolic disorders [9,10,11]. Omega-3 fatty acids, found in fatty fish and certain plant oils, have been linked to improved lipid profiles and reduced cardiovascular risks, which are often elevated in individuals with obesity and T2DM [12,13].

Microbiotics, including probiotics, prebiotics, postbiotics, and synbiotics, are essential for maintaining a healthy gut microbiota composition and play a pivotal role in maintaining metabolic and immune homeostasis. Probiotics, live beneficial microorganisms, and prebiotics, non-digestible fibers that support the growth of beneficial microbes, work together to maintain a balanced microbiota critical for optimal gut function, while postbiotics, the byproducts of microbial metabolism, and synbiotics, combinations of probiotics and prebiotics, further enhance gut health by fostering a favorable microbiome [14,15,16,17,18]. The gut microbiota profoundly influences metabolic regulation, affecting processes such as insulin sensitivity, lipid metabolism, and inflammation, dysregulation linked to the progression of diabetic kidney disease (DKD) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) [14,16,19,20]. Dysbiosis contributes to systemic inflammation and the production of gut-derived uremic toxins, exacerbating kidney damage. Studies, such as those by Brugman et al., have demonstrated the critical role of gut microbiota in disease modulation, including the prevention of type 1 diabetes (T1D) onset in a diabetes-prone rat model through antibiotic treatment and dietary interventions [21]. Additionally, gut microbiome imbalances are strongly associated with metabolic disorders such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, and kidney diseases [22,23]. Probiotics, by modulating the gut microbiota, offer a promising therapeutic approach to mitigate these effects through mechanisms such as reducing uremic toxins, enhancing gut barrier integrity, attenuating inflammation, and inhibiting pathogen bacteria growth [24,25]. This review investigates the potential of probiotics as a complementary strategy primarily for managing type 2 diabetes and obesity, while also addressing their secondary benefits in mitigating complications, such as DKD and CKD, emphasizing current evidence and future research directions.

Nutrigenetics and nutrigenomics provide insights into how genetic variations influence dietary responses and how diet modulates gene expression, offering new opportunities for managing complex metabolic disorders such as T2DM and obesity. Key genetic variations, including SNPs in FTO (fat mass and obesity-associated) and PPARγ (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma), play significant roles in metabolic regulation, affecting insulin sensitivity, lipid metabolism, and energy balance [26,27,28]. Additionally, host genetics influence gut microbiota composition, which in turn impacts the production of metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), critical for metabolic health. The emerging field of nutrigenomics further highlights the interaction between the gut microbiome and the host’s genetic makeup, emphasizing how genetic variations shape individual responses to dietary components and microbiota, affecting susceptibility to metabolic diseases. Integrating genetic and microbiota profiling into personalized nutrition strategies has demonstrated potential in improving metabolic outcomes. Moreover, microbiome modulation—through diet, functional foods, and microbiotic supplementation—is increasingly recognized as a critical mechanism for enhancing metabolic health, offering a promising approach to tailored interventions for preventing and managing obesity and T2DM [29,30].

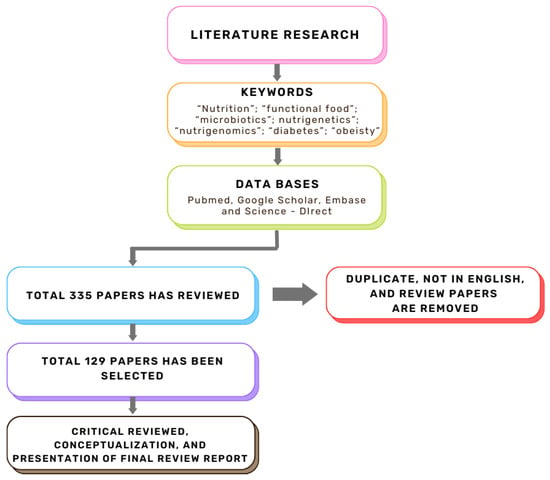

This review aims to explore the synergistic roles of functional foods, microbiotics, nutrigenomics, and nutrigenetics in modulating the metabolic pathways associated with T2DM and obesity. Figure 1 illustrates the systematic literature review process conducted in this study, which identified 335 relevant papers, with 129 core articles selected after screening for duplicates, non-English, and irrelevant studies. By integrating these approaches, researchers and practitioners can advance holistic and individualized dietary interventions, potentially improving metabolic health and providing sustainable solutions for managing these pervasive conditions.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the literature review.

2. Impact of Bioactive Compounds on Metabolic Health in Type 2 Diabetes and Obesity

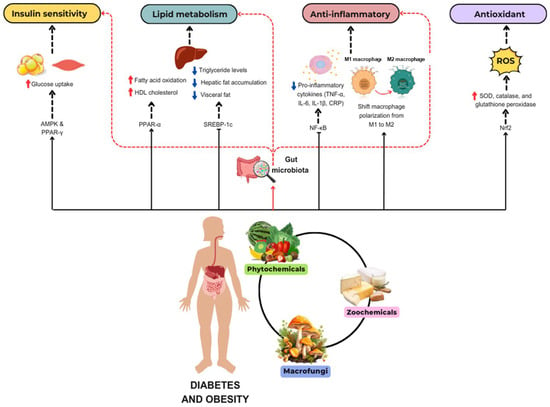

The role of bioactive compounds in modulating metabolic health has become a focal point in the management of T2DM and obesity. These naturally occurring substances, found in phytochemical, zoochemical, and microchemical forms, offer various mechanisms to influence key metabolic pathways, particularly those involved in insulin sensitivity, fat metabolism, and inflammation. Research into their potential therapeutic effects highlights the importance of bioactive compounds in preventing and managing these chronic diseases (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The mechanism of phytochemicals, zoochemicals, and macrofungi on metabolic health in diabetes and obesity. The red arrows indicate activation, blue arrows indicate inhibition, and dotted lines represent indirect effects or interactions.

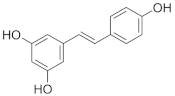

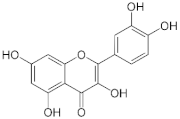

2.1. Phytochemicals

Phytochemicals are natural plant compounds, first introduced by chemist Julius Sachs, with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and metabolic-regulating properties, aiding in preventing chronic diseases, like T2DM and obesity, and are key to nutritional interventions [31].

Mechanism of Action

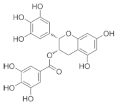

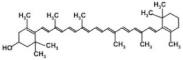

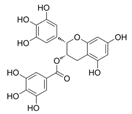

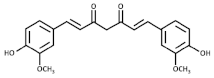

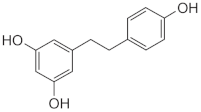

Natural compounds have shown significant potential in improving the metabolic dysregulation associated with T2DM and obesity by regulating glucose and lipid metabolism, alleviating oxidative stress, and enhancing insulin sensitivity. Studies indicate that epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), a major active component of green tea, effectively ameliorates glucose and lipid metabolism while reducing oxidative stress in type 2 diabetic rat models [32]. Dihydro-resveratrol mitigates oxidative stress, adipogenesis, and insulin resistance in high-fat diet-induced obese mouse models and in in vitro systems via AMPK activation [33]. Additionally, the fruits of Rosa laevigata and their bioactive principal sitostenone promote glucose uptake and improve insulin sensitivity in hepatic cells through AMPK/PPAR-γ signaling pathways [34]. Resveratrol, a polyphenolic compound, has garnered significant attention for its clinical applications in managing T2DM and obesity, demonstrating potential in addressing metabolic disorders. However, its limited bioavailability can be overcome through nanotechnology, further enhancing its therapeutic efficacy [35]. Table 1 summarizes the effects of key phytochemicals on metabolic health, highlighting their roles in modulating glucose metabolism, lipid profiles, and oxidative stress. Chronic low-grade inflammation is a key pathological feature of both obesity and T2DM. Phytochemicals, including flavonoids (e.g., quercetin), polyphenols (e.g., curcumin, resveratrol), and carotenoids (e.g., β-carotene), exert potent anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa B), a major transcription factor involved in the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and C-reactive protein (CRP). By suppressing NF-κB activation, these phytochemicals reduce the production of inflammatory mediators that promote insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction, which are key contributors to the development of diabesity [21,36,37,38]. Additionally, certain flavonoids (e.g., quercetin) have been shown to shift macrophage polarization from the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype to the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype, further mitigating the inflammatory burden in adipose tissue and improving metabolic health [36,39].

Oxidative stress, primarily driven by the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of obesity and T2DM by impairing insulin signaling and inducing β-cell dysfunction [40,41]. Phytochemicals, such as polyphenols (e.g., resveratrol, curcumin) and carotenoids (e.g., lutein, zeaxanthin), exhibit potent antioxidant properties by activating Nrf2 (nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2), a transcription factor that promotes the expression of endogenous antioxidant enzymes, including superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, and glutathione peroxidase. These antioxidants neutralize ROS, thereby reducing oxidative damage to cellular structures, improving insulin signaling, and protecting pancreatic β-cells from oxidative stress [42,43,44]. Consequently, phytochemicals help to maintain glucose homeostasis by improving insulin sensitivity and preventing β-cell dysfunction.

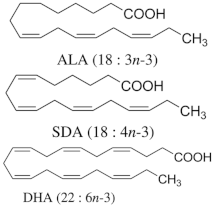

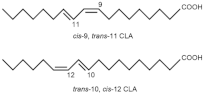

The accumulation of visceral fat is closely associated with insulin resistance and metabolic dysfunction [45]. Several phytochemicals, including omega-3 fatty acids (ALA from flaxseeds) and polyphenols (e.g., resveratrol, curcumin), regulate lipid metabolism by modulating key transcription factors such as PPAR-α and SREBP-1c (sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c) [46,47,48]. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (ω-3 PUFAs) promote fatty acid oxidation in skeletal muscle by activating PPAR-α, thereby improving metabolic regulation, reducing triglyceride levels, and enhancing insulin sensitivity rather than directly influencing HDL (high-density lipoprotein) cholesterol levels [47]. Polyphenols, such as resveratrol, inhibit SREBP-1c, a key regulator of fat synthesis in the liver, thereby reducing hepatic fat accumulation and improving liver function [46,49]. Together, these phytochemicals help to decrease visceral fat, improve lipid metabolism, and enhance fat oxidation, all of which contribute to reducing the risk of obesity-related metabolic diseases like T2DM.

The gut microbiome, including bacteria, archaea, fungi, and viruses, plays a critical role in host metabolism and immune regulation. While probiotics and prebiotics are well-established in gut health, emerging evidence highlights the gut virome’s role in microbial modulation and disease prevention. Probiotics, such as Bifidobacteria, and prebiotics, such as inulin, enhance gut microbiota composition, cognitive function, and metabolic health. Randomized controlled trials demonstrate that their intake improves cognition, reduces body fat, and strengthens gut barrier integrity [50,51,52]. Optimized prebiotic formulations (inulin, FOS, GOS) further enhance probiotic efficacy [53]. Beyond probiotics, the gut virome, particularly bacteriophages, modulates microbial diversity and gut homeostasis. Phages selectively target bacterial populations, influencing obesity, T2DM, and metabolic disorders, while also interacting with immune pathways to regulate inflammation [54]. Integrating probiotics, prebiotics, and microbiotics (phages and virome modulation) offers a holistic strategy for improving gut health and metabolic function. Future research should explore their synergistic potential in precision microbiome-based therapies. Integrating these findings, Table 1 provides a detailed summary of the beneficial effects of phytochemicals on various metabolic pathways, highlighting their multifaceted roles in managing obesity and T2DM.

Table 1.

Effects of phytochemicals.

Table 1.

Effects of phytochemicals.

| Phytochemical | Species | Experiment Model/Dosage | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) | Green tea (Camellia sinensis) |

|

| [55] ** |

Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) β-Cryptoxanthin  | Catechins from green tea (Camellia sinensis) β-Cryptoxanthin from citrus fruits | Monosodium-glutamate-induced obese male C57BL/6J mice/1.7 mg green tea catechins and 50 µg β-Cryptoxanthin/kg/day. |

| [56] *** |

Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) Caffeine  | White tea | Obese human participants (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2)/consumed 2 cups of white tea daily (brewed from sachets) along with a calorie-restricted diet (1400–1600 kcal/day) and exercise for 12 weeks *. |

| [57] **** |

Curcumin | Turmeric (Curcuma longa) | 3T3-L1 preadipocytes/optimal effects at 10 µM Male C57BL/6J mice with diet induced obesity)/50 mg/kg/day for 8 weeks. |

| [58] ** |

| Male C57BL/6J mice with diet-induced obesity and genetically obese mice/3% dietary curcumin mixed in the diet for 6 weeks *. |

| [59] *** | ||

| Prediabetic human participants (n = 240)/6 capsules per day (1500 mg/day) for 9 months *. |

| [60] **** | ||

| Obese human participants with type 2 diabetes (n = 229)/6 capsules per day (1500 mg/day) for 12 months *. |

| [61] **** | ||

Dihydro-Resveratrol (DR2) | Dendrobium spp., Dioscorea spp., Bulbophyllum spp. | 3T3-L1 cells and insulin-resistant HepG2 and C2C12 cells/DR2 (10, 20, 40 µM) for 48 h **. High-fat diet (HFD)-induced obese C57BL/6J mice/DR2 (40 or 80 mg/kg/day) for 3 weeks *. |

| [33] ** |

Resveratrol | Grapes (Vitis vinifera), berries, peanuts (Arachis hypogaea). | Patients with type 2 diabetes (n = 110)/200 mg/day (99% pure trans-resveratrol) for 24 weeks. |

| [62] **** |

| Grapes (Vitis vinifera), peanuts (Arachis hypogaea), red wine. | Obese but otherwise healthy male volunteers (n = 11)/150 mg/day (99% pure trans-resveratrol, resVida™) for 30 days. |

| [63] **** | |

Quercetin | Apples (Malus domestica), onions (Allium cepa), and berries. | Male C57BL/6J mice were fed a high-fat diet (HF) or HF supplemented with 0.05% quercetin (HFQ) for 6 weeks. |

| [64] *** |

| Patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (n = 170)/500 mg/day of quercetin dihydrate for 12 weeks. |

| [65,66] **** | ||

β-sitosterol | Chia (Salvia hispanica L.) | Non-polar fractions (light petroleum and dichloromethane) from the aerial parts of Salvia hispanica. |

| [67] * |

n-6 and n-3 PUFA |

| Hypertriglyceridemic adults (n = 59)/ALA group: 20 g/day of linseed oil (7.42 g ALA/day); SDA group: 20 g/day of echium oil (1.57 g SDA/day); DHA group: 12 g/day of microalgae oil (1.64 g DHA/day) for 10 weeks. |

| [68] **** |

* in vitro; ** in vitro and in vivo; *** animal model; **** human clinical study. Abbreviation: γH2AX, Phosphorylated H2A histone family member X; 8-OHdG, 8-Hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine; ROS, Reactive Oxygen Species; Nrf2, Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2; GPX4, Glutathione Peroxidase 4; HO-1, Heme Oxygenase-1; TNF-α, Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha; IL-6, Interleukin-6; IL-1β, Interleukin-1 Beta; MDA, Malondialdehyde; GSH, Glutathione; LDL, Low-Density Lipoprotein; HDL, High-Density Lipoprotein; UCP1, Uncoupling Protein 1; PGC-1α, Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Coactivator 1-Alpha; ATP, Adenosine Triphosphate; PPARγ, Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma; HbA1c, Hemoglobin A1c (Glycated Hemoglobin); NF-κB, Nuclear Factor Kappa B; AMPK, AMP-Activated Protein Kinase; MCP-1, Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 (also known as CCL2); C/EBPα, CCAAT/Enhancer-Binding Protein Alpha; FASN, Fatty Acid Synthase; hs-CRP, High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein; AMPK-SIRT1-PGC-1α, AMP-Activated Protein Kinase—Sirtuin 1—Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Coactivator 1-Alpha Pathway; DPPH, 2,2-Diphenyl-1-Picrylhydrazyl (a free radical used in antioxidant assays); EPA, Eicosapentaenoic Acid; ALA, Alpha-Linolenic Acid; SDA, Stearidonic Acid; DHA, Docosahexaenoic Acid.

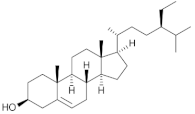

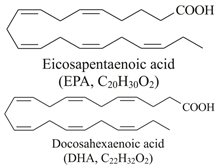

2.2. Zoochemicals

Zoochemicals are natural compounds from animal-based foods, such as omega-3 fatty acids and linoleic acid (CLA), with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and metabolic-regulating effects that reduce the risks of cardiovascular diseases and T2DM. The term was introduced by nutrition researchers in the late 20th century to describe health-promoting animal-derived components [69]. Table 2 provides a comprehensive summary of the effects of zoochemicals, highlighting their roles in improving metabolic health and reducing the risks associated with obesity, T2DM, and cardiovascular diseases.

Mechanism of Action

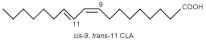

Zoochemicals, including omega-3 fatty acids (EPA and DHA), CLA, and milk-derived bioactive peptides, play pivotal roles in improving metabolic health by targeting glucose and lipid metabolism, inflammation, and fat accumulation. Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), and bioactive compounds in dairy products play critical roles in metabolic health and inflammation regulation. A balanced dietary ratio of n-6:n-3 PUFAs has been shown to improve the total fatty acid profile in red blood cells and reduce inflammatory markers, positively impacting inflammation in individuals with obesity [70]. Omega-3 fatty acids were found to reduce the number of adipose tissue macrophages in insulin-resistant subjects, thereby mitigating inflammatory responses [71]. A randomized controlled trial demonstrated that the consumption of goat cheese naturally rich in Omega-3 and CLA improved cardiovascular and inflammatory biomarkers in overweight and obese subjects [72]. Additionally, cis-9, trans-11 conjugated linoleic acid exhibited anti-inflammatory effects in bovine mammary epithelial cells stimulated by Escherichia coli, mediated via inhibition of the NF-κB signaling pathway [73]. A study of Korean adults further revealed that dairy and soy product intake was associated with a reduced 10-year risk of coronary heart disease [74]. Moreover, bioactive peptides derived from goat milk showed potential anticancer effects on the HCT-116 human colorectal carcinoma cell line [75]. As summarized in Table 2, these findings collectively demonstrate that zoochemicals such as PUFAs, CLA, and bioactive components in dairy products hold significant potential in improving metabolic health, reducing inflammation, and lowering the risks of cardiovascular and cancer-related diseases.

Collectively, PUFAs, CLA, and bioactive components in dairy products demonstrate significant potential in improving metabolic health, reducing inflammation, and lowering the risk of cardiovascular and cancer-related diseases.

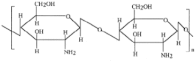

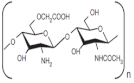

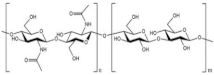

Chitin and its derivatives (e.g., chitosan, chitosan oligosaccharides, and chitin–glucan fibers) exhibit extensive potential in improving metabolic health by modulating gut microbiota, promoting metabolic signaling, and enhancing therapeutic efficacy. Formulated chitosan microspheres have been shown to remodel gut microbiota and regulate liver miRNA in diet-induced type 2 diabetic rats, improving metabolic functions [76]. According to Lopez-Santamarina et al., insect-based ingredients and insect powder exhibit both beneficial and harmful effects on gene modification regulation, likely due to their high protein content. In contrast, chitin-derived compounds (e.g., chitosan) demonstrate better prebiotic activity in low-protein diets, promoting beneficial bacteria while inhibiting pathogenic microbes. Additionally, chitin derivatives show potential in anti-inflammatory responses, immune stimulation, diabetes prevention, and obesity control. Further research is needed to enhance their application as a dietary fiber source in human nutrition [77].

Carboxymethyl chitin demonstrated anti-obesity effects in 3T3-L1 adipocytes via AMPK and aquaporin-7 signaling pathways [78]. A randomized controlled trial revealed that chitin–glucan fibers reduced oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) levels, indicating potential cardiovascular protective effects [79]. Clinically, chitosan oligosaccharides significantly enhanced the therapeutic efficacy of sitagliptin in Chinese elderly patients with T2DM [80]. Furthermore, dietary chitin–glucan fibers modulated gut bacteria, such as Roseburia spp. (Clostridial cluster XIVa), and improved high-fat diet-induced metabolic alterations in mice [81]. These findings highlight the significant potential of chitin and its derivatives in managing T2DM, obesity, and cardiovascular diseases, providing new avenues for functional foods and therapeutic interventions. As summarized in Table 2, these findings collectively demonstrate that zoochemicals such as PUFAs, CLA, bioactive components in dairy products, and chitin and its derivatives hold significant potential in improving metabolic health, reducing inflammation, and lowering the risks of cardiovascular, obesity-related, and cancer-related diseases.

Table 2.

Effects of zoochemicals.

Table 2.

Effects of zoochemicals.

| Zoochemical | Experiment Model | Dosage and Duration | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Cis-9, Trans-11-Conjugated Linoleic Acid (CLA 9,11) | Bovine Mammary Epithelial Cells (BMECs) | 600 µmol/L H₂O₂ for 8 h |

| [82] * |

| Alzheimer’s disease (AD) mouse model (hAPPSwInd, J20) and C57BL/6 wild-type mice | 0.4% CLA in the diet (~16 mg/day per mouse) from 6 to 14 months of age |

| [83] ** | |

| Cis-9, Trans-11, and Trans-10, Cis-12 Conjugated Linoleic Acid (CLA 9,11 and CLA 10,12)  | EA.hy926 endothelial cells (human umbilical vein endothelial cell lineage) | 1 and 10 µM for CLA9,11 and CLA10,12 for 48 h |

| [84] * |

| Lactating Holstein dairy cows | 120 g/day of CLA supplement providing 12 g/day of each isomer from 21 days pre-calving to 60 days post-calving |

| [85] ** | |

| Overweight and obese adults (n = 68; BMI ≥ 27 and <40 kg/m2) | 60 g/day of PUFA-enriched goat cheese for 12 weeks |

| [72] *** | |

Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFAs), including n-3 PUFA and Conjugated Linoleic Acid (CLA)  | Primary human subcutaneous and visceral adipocytes | 100 μM EPA and/or DHA for 72 h |

| [86] * |

| Omega-3 fatty acids (EPA and DHA)  | Fish oil such as: Salmo salar (Atlantic salmon) Clupea harengus (Atlantic herring) Engraulis encrasicolus (European anchovy) Sardinops sagax (Pacific sardine) | Wistar rats on a high-fat diet (HFD)/3.4% fish oil of total dietary energy for 8 weeks. |

| [87] ** |

| Twelve obese women (BMI ≥ 35) and 12 healthy women (BMI < 24)/4.8 g/day (3.2 g EPA + 1.6 g DHA) for 3 months. |

| [88] *** | ||

| 60 diabetic patients with NAFLD/2 g/day (180 mg EPA and 120 mg DHA per capsule, 2 capsules daily) for 12 weeks. |

| [89] *** | ||

Chitosan | Rats fed with a high-sugar and high-fat diet (HSFD) to induce Type 2 diabetes | Wistar rats on a HSHF/Chitosan microsphere (CMS) supplement providing 40 mg/day for 90 days. |

| [76] ** |

Carboxymethyl chitin | 3T3-L1 preadipocytes as a cell model | Carboxymethyl chitin (CM-chitin) was tested in 3T3-L1 adipocytes at concentrations of 50, 100, and 200 μg/mL |

| [78] * |

Chitin-glucan complex | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Participants received either 1.5 g/day or 4.5 g/day of chitin–glucan for 6 weeks |

| [79] *** |

* in vitro; ** animal model; *** human clinical study. Abbreviation: SOD, Superoxide Dismutase; CAT, Catalase; GPx, Glutathione Peroxidase; T-AOC, Total Antioxidant Capacity; Aβ, Amyloid Beta (general term for amyloid beta peptides); MCP-1, Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 (also known as CCL2); RANTES, Regulated upon Activation, Normal T Cell Expressed and Secreted (also known as CCL5); COX-2, Cyclooxygenase-2; NF-κB1, Nuclear Factor Kappa B Subunit 1; IGF-1, Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1; CCL2, C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 2 (same as MCP-1); CX3CL1, C-X3-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 1 (also known as Fractalkine); CIDEA, Cell Death-Inducing DFFA-Like Effector A; CPT1, Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase 1; FLI, Fatty Liver Index; LAP, Lipid Accumulation Product; VAI, Visceral Adiposity Index.

2.3. Macrofungi

In addition to the roles of phytochemical and zoochemical functional components, we have previously reviewed the clinical potential of medicinal components from edible fungi for T2DM treatment and in the prevention of noncommunicable diseases [90]. Macrofungi, including edible and medicinal mushrooms, are emerging as rich sources of bioactive compounds with promising potential for managing metabolic health in T2DM and obesity. These mushrooms are abundant in polysaccharides, terpenoids, phenolic compounds, and sterols, each contributing unique therapeutic properties [91]. For instance, phenolic compounds in Agaricus bisporus (white button mushroom) act as potent antioxidants, alleviating oxidative stress, a key factor in IR and β-cell dysfunction. Their antihyperglycemic activity was demonstrated in alloxan-induced diabetic rats, where ethanol (ABEE) and methanol (ABME) extracts reduced serum glucose levels, improved lipid profiles, and restored liver function, with ABEE showing superior efficacy [92]. Similarly, aqueous extracts of Pleurotus ostreatus (oyster mushroom) and Lentinula edodes (shiitake mushroom) exhibited strong antioxidant, antiviral, and anticancer activities, mediated by bioactive proteins, like superoxide dismutase, and compounds such as catechin and quercetin [93].

Vitamin D plays a role in regulating glucose metabolism and inflammation, potentially reducing the risk of T2DM and obesity. Studies have shown that vitamin D deficiency is associated with insulin resistance, T2DM, and adipose tissue inflammation; appropriate supplementation may improve metabolic health [94]. Hsu et al. first demonstrated that pulsed UV light-treated Pleurotus citrinopileatus significantly increased serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] levels in healthy adults, addressing vitamin D deficiency. This technique enhances vitamin D2 content in mushrooms, providing a safe and sustainable way to boost daily vitamin D intake. It also offers a novel solution for addressing global vitamin D insufficiency and related metabolic issues [95].

Further studies highlight the in vivo therapeutic potential of Pleurotus ostreatus-derived insoluble dietary fiber (POIDF) in addressing obesity and metabolic dysregulation. POIDF supplementation in rats reduced body weight, serum lipid levels, and hepatic fat deposition, while enhancing antioxidant capacity and modulating gut microbiota composition. Proteomic and metabolomic analyses revealed its influence on key metabolic pathways, including PPAR and adipocytokine signaling, and increased SCFA production [96]. Additionally, Lentinula edodes has been shown to contain novel bioactive compounds with potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, surpassing the efficacy of standard drugs, like indomethacin, in inhibiting NO and TNF-α production [97].

The submerged cultivation of Trametes sp. further emphasizes the potential of mushrooms as functional foods. A phytochemical analysis revealed high levels of saponins, anthraquinones, phenolic compounds, flavonoids, and β-glucan, contributing to strong antioxidant activity and potential applications in managing oxidative stress and metabolic disorders [98]. Evidence from in vitro and in vivo studies supports the therapeutic potential of macrofungi, with their bioactive compounds contributing to anti-inflammatory, antihyperglycemic, and lipid-regulating effects [99,100]. Moreover, a prospective cohort study demonstrated an inverse relationship between mushroom consumption and the risk of T2DM, with higher intakes associated with improved glucose metabolism and reduced oxidative stress. The bioactive compound ergothioneine and other metabolites were identified as significant contributors to these effects. These findings position macrofungi as sustainable and effective dietary components for mitigating inflammation and managing T2DM, particularly when consumed raw or minimally processed to preserve their bioactivity [101].

Hyperglycemia-induced renal damage often triggers inflammation and fibrosis, leading to DKD. Studies on Cordyceps species have highlighted their antidiabetic and nephroprotective potential. Fermented Cordyceps sinensis (CS) demonstrated an ability to reduce cytotoxicity, inhibit apoptosis, and promote cell proliferation in high-glucose-induced HK-2 cells by modulating key molecular markers, including bax, caspase-3, VEGFA, phosphorylated AKT (P-AKT), and phosphorylated ERK (P-ERK) and PTEN [102]. Similarly, aqueous extracts of Cordyceps militaris (CM) in diet streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats significantly lowered blood glucose, improved lipid profiles, and enhanced renal function by reducing albuminuria, serum creatinine, and urea nitrogen levels. CM also attenuated oxidative stress and modulated inflammatory markers, showcasing its potential for managing type 2 diabetes and DKD [103].

3. The Potential of Probiotics and Gut Microbiota Modulation in the Treatment of Diabetic Kidney Disease and Chronic Kidney Disease

DKD and CKD are caused by multiple factors, including diabetes, hypertension, chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and metabolic dysregulation. Persistent hyperglycemia and hypertension lead to glomerular hyperfiltration and high pressure, causing glomerular damage and renal fibrosis. Inflammation and oxidative stress also play critical roles in kidney injury. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota has been linked to the progression of CKD and DKD, as impaired gut barrier function increases the production of uremic toxins, such as indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate, which exacerbate kidney damage. Probiotics, by modulating the gut microbiota, can reduce the generation of harmful metabolites, lower systemic inflammation, and improve renal function, making them a promising approach in the management of CKD and DKD [104,105,106].

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum NKK20 has been shown to significantly reduce renal inflammation, serum oxidative stress, and advanced glycation end-product (AGE) levels in diabetic mice, thereby improving kidney damage. Treatment with NKK20 increases the anti-inflammatory metabolite butyrate in feces; metabolomics analysis reveals alterations in 24 metabolites involved in glycerophospholipid and arachidonic acid metabolism. In human renal HK-2 cells, butyrate enhances tight junction gene expression, inhibits fibrosis, and suppresses the PI3K–AKT pathway activation. These findings suggest that NKK20 can effectively prevent and treat diabetic kidney injury by reducing blood glucose levels, decreasing AGE concentrations, and promoting butyrate production [107].

Huang’s study also developed the probiotic Lactobacillus mix (Lm), which demonstrated efficacy in improving gut dysbiosis caused by chronic kidney disease (CKD). The probiotic increased short-chain fatty acid production, reduced uremic toxins and related metabolites, alleviated oxidative stress and inflammation, and improved renal function. Both animal and clinical trials revealed that Lm enhanced gut microbiota diversity, reduced toxin accumulation, and mitigated the decline in glomerular filtration rate. Additionally, variable responses in human and feline trials highlighted potential connections between microbial species and metabolites, emphasizing Lm’s precision potential in delaying CKD progression [108].

Vazir et al. highlighted that the gut microbiota functions as a symbiotic ecosystem with both nutritional and protective roles, influenced by the biochemical environment. Their study examined the effects of dietary and pharmacological interventions in uremia and CKD on the gut microbiome. Microbial DNA from the feces of 24 end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients and 12 healthy individuals was analyzed using phylogenetic microarrays. The results showed significant differences in 190 operational taxonomic units (OTUs) between the ESRD and control groups, with notable increases in OTUs from Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, Enterobacteriaceae, Halomonadaceae, Moraxellaceae, Nesterenkonia, Polyangiaceae, Pseudomonadaceae, and Thiotrichaceae in ESRD patients. A separate study using 5/6 nephrectomized rats revealed significant changes in 175 OTUs, including a marked reduction in Lactobacillaceae and Prevotellaceae. These findings demonstrate that uremia profoundly alters gut microbiota composition, although the biological implications require further investigation [109].

Kuo et al. demonstrated that approximately one-third of end-stage CKD patients suffer from diabetic nephropathy (DN), which exacerbates renal dysfunction, with few preventive options available. A probiotic combination of Lactobacillus acidophilus TYCA06, Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis BLI-02, and Bifidobacterium bifidum VDD088 (high dose: 5.125 × 10⁹ CFU/kg/day; low dose: 1.025 × 10⁹ CFU/kg/day) significantly reduced blood urea nitrogen (BUN), serum creatinine, blood glucose, and urinary protein fluctuation rates after 8 weeks in db/db mouse models. The probiotics also improved blood pressure, glucose tolerance, and renal fibrosis. In vitro analysis revealed that TYCA06 and BLI-02 significantly increased acetate production, while all three strains demonstrated antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and glucose consumption activities. Collectively, this probiotic combination effectively stabilizes glucose levels and slows CKD progression induced by diabetes [110].

4. Interplay of Nutrigenetics and Nutrigenomics in Personalized Interventions for Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes

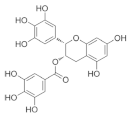

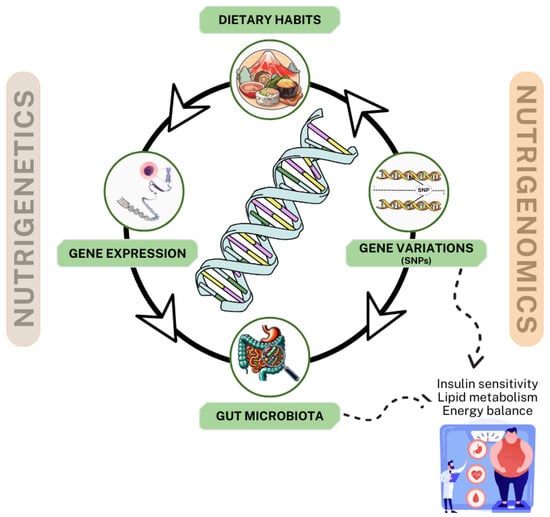

The intersection of nutrigenetics and nutrigenomics represents a transformative approach to understanding the complex relationship between diet, genetic predisposition, and metabolic health, particularly in managing T2DM and obesity. These two complementary disciplines offer profound insights into the genetic and molecular mechanisms underlying individual variability in response to dietary interventions, enabling the development of personalized nutrition strategies tailored to optimize metabolic outcomes [111,112]. Figure 3 illustrates an interactive model of nutrigenetics and nutrigenomics in the management of T2DM and obesity. This model highlights the interconnections among dietary habits, gene variations (e.g., single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)), gene expression, and gut microbiota, collectively influencing insulin sensitivity, lipid metabolism, and energy balance. Nutritional components in the diet not only modulate gene expression but also reshape the gut microbiota composition, further impacting metabolic functions and providing a scientific basis for personalized nutritional.

Figure 3.

Interactive model of nutrigenetics and nutrigenomics in the management of type 2 diabetes and obesity.

To further clarify the distinction between nutrigenetics and nutrigenomics, the latter focuses specifically on how dietary components influence gene expression through epigenetic mechanisms such as DNA methylation, histone modification, and non-coding RNA regulation. These mechanisms reveal how diet interacts with the genome to modulate metabolic health beyond genetic predisposition. For instance, dietary polyphenols, fatty acids, and vitamins have been shown to regulate epigenetic marks, influencing the genes involved in glucose metabolism, lipid homeostasis, and inflammation. By incorporating this expanded understanding of nutrigenomics, this model emphasizes its unique contribution to personalized nutrition through the modulation of gene expression to optimize metabolic outcomes [113,114].

Moreover, according to the study by Scala et al., dietary components, like polyphenols, can activate specific epigenetic pathways, influencing non-coding RNA expression. These mechanisms provide new insights into how diet can reshape gene activity and metabolic health. Mediterranean diet plants, rich in bioactive compounds, such as polyphenols, flavonoids, and terpenoids, have been shown to exert nutrigenomic effects by modulating gene expression through epigenetic mechanisms. Notably, indicaxanthin from prickly pear, kaempferol and quercetin from capers, and terpenoids, like carvacrol and γ-terpinene, from oregano and thyme, exhibit antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial properties, contributing to metabolic regulation. Additionally, these plants thrive in arid environments, benefiting from plant growth-promoting (PGP) microorganisms that enhance stress resistance and sustainability. This expanded understanding of nutrigenomics underscores its critical role in advancing personalized nutrition strategies by focusing on the modulation of gene expression through epigenetic marks [115].

Research in obesity genetics has significantly advanced our understanding of its monogenic and polygenic forms. Monogenic obesity, often characterized by early-onset and severe obesity, results from rare mutations in genes such as LEP (leptin), MC4R (melanocortin 4 receptor), and SH2B1 (SH2B adaptor protein 1) [116,117]. In contrast, polygenic obesity stems from the cumulative effects of numerous genetic variants, each exerting a modest influence on body weight regulation and metabolic processes. Recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified key loci associated with obesity-related traits, deepening our understanding of the genetic architecture underlying polygenic obesity [118,119]. These advancements lay a critical foundation for the development of personalized strategies aimed at preventing and managing obesity.

Gene–diet interaction studies further emphasize the role of genetic variants in shaping metabolic outcomes. For instance, the Pro12Ala polymorphism of the PPARγ2 gene was shown to interact with dietary fat intake, where Ala12 carriers exhibited improved insulin sensitivity and reduced BMI when following a Mediterranean diet [120]. Similarly, variants in the FTO gene (rs9939609 and rs9930506) were associated with higher BMI and fat intake in Emirati populations, as well as attenuated weight loss responses in Mediterranean diet interventions [121,122].

In the South Indian population, polymorphisms in the ADIPOQ gene (e.g., rs2241766 and rs1501299) influenced serum adiponectin levels and conferred differential risks for obesity and T2DM [123]. Additionally, TCF7L2 gene variants (rs7903146 and rs290487) interacted with BMI and waist circumference to elevate T2DM risk, as shown in Chinese cohorts [124]. In Korean T2DM patients, the rs7903146 T allele of TCF7L2 was linked to a significantly higher risk of peripheral arterial disease, particularly in those with long-standing diabetes [125].

Furthermore, bioactive compounds from Hibiscus sabdariffa, including delphinidin-3-sambubioside (DS3), quercetin (QRC), and hibiscus acid (HA), offer promising insights for nutrigenomics through their interactions with key genes and pathways influencing metabolic health. DS3 primarily targets genes such as AKT1, EGFR, and PIK3R1, modulating the PI3K–AKT signaling pathway. These interactions regulate glucose metabolism, inflammation, and angiogenesis, suggesting DS3’s role in addressing insulin resistance and metabolic dysregulation. QRC affects multiple gene networks, including CDK2, CYP1B1, and IGF1R, involved in metabolic regulation and inflammation. Its impact on the PI3K–AKT pathway and lipid metabolism highlights its potential in personalized strategies for managing obesity and glucose homeostasis. HA uniquely targets genes like PPARA and GABRA2, influencing neurological pathways such as neuroactive ligand–receptor interactions. These gene interactions suggest potential applications in neurodegenerative disease management and brain health [126].

Izquierdo-Lahuerta’s study demonstrated that the parathyroid hormone-related protein/parathyroid hormone 1 receptor (PTHrP/PTH1R) axis plays a central role in adipose tissue differentiation and remodeling. On the one hand, it is crucial in directing stem cells toward either adipogenesis or osteogenesis. On the other hand, PTHrP/PTH1R appears to be essential in adipose tissue “stress” conditions, whether due to excess fat accumulation in obesity, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and gestational diabetes, or disease-induced metabolic dysfunction in cancer and chronic kidney disease [127].

Hernando Boigues et al. reported that PUFAs may regulate obesity-related parameters through epigenetic mechanisms. Studies suggest that PUFAs reversibly alter adipogenesis gene methylation, influencing gene expression and offering the potential for nutritional interventions. Additionally, PUFAs may interact with miRNAs to modulate lipid metabolism, although research on histone modifications remains limited. Current data do not establish an optimal PUFA dosage; however, their role in functional foods and non-pharmacological approaches warrants further study. Given the varying effects of different PUFAs, future research must control for dosage, bioavailability, and genetic backgrounds to clarify their epigenetic impact on obesity [128]. Saad et al. reported that anti-obesity drugs target different adipocyte stages, while polyphenol bioactive compounds (e.g., genistein, apigenin, quercetin, resveratrol) inhibit adipogenesis or induce apoptosis. Phytochemicals regulate epigenetic mechanisms, including DNA methylation, histone acetylation, miRNA, and chromatin remodeling, offering a potential strategy for obesity management. Western diets induce epigenetic alterations; however, natural phytochemicals and nutritional interventions may reverse these effects, benefiting both individual health and future generations’ epigenomes [129].

5. Conclusions

This review explored the synergistic roles of functional foods, microbiotics, nutrigenetics, and nutrigenomics in the comprehensive management of T2DM and obesity. The findings demonstrated that bioactive components in functional foods, such as phytochemicals, zoochemicals, and fungal compounds, effectively modulate metabolic pathways, improving insulin sensitivity, lipid metabolism, and inflammatory responses. Microbiotics studies highlighted the critical relationship between gut microbiota and metabolic health, emphasizing the benefits of probiotic and prebiotic supplementation in enhancing gut ecology. Additionally, nutrigenetics and nutrigenomics underscored the influence of genetic variations (e.g., SNPs) on dietary responses and gene expression, enabling personalized nutritional interventions. This research provides comprehensive and sustainable solutions for T2DM and obesity prevention and management, emphasizing the need for further clinical studies to validate the long-term efficacy and safety of these strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.N.L. and S.-C.L.; validation, S.-P.L., C.-M.C., C.-T.S. and T.-C.F.; writing—original draft preparation, H.N.L.; writing—review and editing, D.H.N.N.; supervision, S.-C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Taoyuan Armed Forces General Hospital (grant number: TYAFGH-A-113019).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: A pooled analysis of 3663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2024, 403, 1027–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, J.S.; Palacio, T.L.N.; Vieira, T.A.; Nakandakare-Maia, E.T.; Grandini, N.A.; Ferron, A.J.T.; Francisqueti-Ferron, F.V.; Correa, C.R. An overview of the complex interaction between obesity and target organ dysfunction: Focus on redox-inflammatory state. Nutrire 2023, 48, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliano, D.J.; Boyko, E.J.; IDF Diabetes Atlas 10th Edition Scientific Committee. IDF Diabetes Atlas; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Cortes, T.; Lopez-Perez, P.; Toledo, A.; Perez-Espana, V.; Aparicio-Burgos, J.; Cuervo-Parra, J. Nutrigenomics and nutrigenetics in functional foods. Int. J. Bio-Resour. Stress Manag. 2018, 9, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ni, H.; Zhang, H. Exploring the relationship between live microbe intake and obesity prevalence in adults. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, L.R. Nutrigenomics and Nutrigenetics in Functional Foods and Personalized Nutrition; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, X.; Olatunji, O.J.; Basit, A.; Sripetthong, S.; Nalinbenjapun, S.; Ovatlarnporn, C. Insights into the phytochemical profiling, antidiabetic and antioxidant potentials of Lepionurus sylvestris Blume extract in fructose/streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1424346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakwo Bassogog, C.B.; Nyobe, C.E.; Sabine, F.Y.; Bruno Dupon, A.A.; Ngui, S.P.; Minka, S.R.; Laure, N.J.; Mune Mune, M.A. Protein hydrolysates of Moringa oleifera seed: Antioxidant and antihyperglycaemic potential as ingredient for the management of type-2 diabetes. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hartogh, D.J.; Gabriel, A.; Tsiani, E. Antidiabetic Properties of Curcumin II: Evidence from In Vivo Studies. Nutrients 2019, 12, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakadate, K.; Kawakami, K.; Yamazaki, N. Synergistic Effect of β-Cryptoxanthin and Epigallocatechin Gallate on Obesity Reduction. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Jia, W.; He, H.; Yin, J.; Xu, H.; He, C.; Zhang, Q.; Peng, Y.; Cheng, R. A New Dietary Fiber Can Enhance Satiety and Reduce Postprandial Blood Glucose in Healthy Adults: A Randomized Cross-Over Trial. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costabile, G.; Della Pepa, G.; Vetrani, C.; Vitaglione, P.; Griffo, E.; Giacco, R.; Vitale, M.; Salamone, D.; Rivellese, A.A.; Annuzzi, G.; et al. An Oily Fish Diet Improves Subclinical Inflammation in People at High Cardiovascular Risk: A Randomized Controlled Study. Molecules 2021, 26, 3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro, P.; Lizio, R.; Izzo, C.; Visco, V.; Damato, A.; Venturini, E.; De Lucia, M.; Galasso, G.; Migliarino, S.; Rasile, B.; et al. A Novel Combination of High-Load Omega-3 Lysine Complex (AvailOm®) and Anthocyanins Exerts Beneficial Cardiovascular Effects. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.C.; Fang, T.J.; Ho, H.H.; Chen, J.F.; Kuo, Y.W.; Huang, Y.Y.; Tsai, S.Y.; Wu, S.F.; Lin, H.C.; Yeh, Y.T. A multi-strain probiotic blend reshaped obesity-related gut dysbiosis and improved lipid metabolism in obese children. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 922993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahayu, E.S.; Mariyatun, M.; Putri Manurung, N.E.; Hasan, P.N.; Therdtatha, P.; Mishima, R.; Komalasari, H.; Mahfuzah, N.A.; Pamungkaningtyas, F.H.; Yoga, W.K.; et al. Effect of probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum Dad-13 powder consumption on the gut microbiota and intestinal health of overweight adults. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Z.; Wu, Y.; Gao, D.; Dong, Y.; Pan, Y.; Gu, S. Gut Microbiome and Metabolome Alterations in Overweight or Obese Adult Population after Weight-Loss Bifidobacterium breve BBr60 Intervention: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, K.S.; Gibson, G.R.; Hutkins, R.; Reimer, R.A.; Reid, G.; Verbeke, K.; Scott, K.P.; Holscher, H.D.; Azad, M.B.; Delzenne, N.M.; et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of synbiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalali, S.; Mojgani, N.; Sanjabi, M.R.; Saremnezhad, S.; Haghighat, S. Functional properties and safety traits of L. rhamnosus and L. reuteri postbiotic extracts. AMB Express 2024, 14, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassaian, N.; Feizi, A.; Aminorroaya, A.; Amini, M. Probiotic and synbiotic supplementation could improve metabolic syndrome in prediabetic adults: A randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2019, 13, 2991–2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, R.; Chen, R. Exploring the causal connection: Insights into diabetic nephropathy and gut microbiota from whole-genome sequencing databases. Ren. Fail. 2024, 46, 2385065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeoluwa, O.A.; Olayinka, J.N.; Adeoluwa, G.O.; Akinluyi, E.T.; Adeniyi, F.R.; Fafure, A.; Nebo, K.; Edem, E.E.; Eduviere, A.T.; Abubakar, B. Quercetin abrogates lipopolysaccharide-induced depressive-like symptoms by inhibiting neuroinflammation via microglial NLRP3/NFκB/iNOS signaling pathway. Behav. Brain Res. 2023, 450, 114503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Guo, Q.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Cao, C.; Jin, L.; Li, C.; Xiao, J.; Zhao, W. Alterations in the Gut Microbiota Composition in Obesity with and without Type 2 Diabetes: A Pilot Study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2024, 17, 3965–3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuli, R.; Cai, J.; Kadeer, A.; Zhang, Y.; Mohemaiti, P. Integrative Analysis Toward Different Glucose Tolerance-Related Gut Microbiota and Diet. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xie, S.; Liu, Y.; Yue, W.; Wang, L.; Liang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, H.; Yu, J. Gut microbiota profiling reflects the renal dysfunction and psychological distress in patients with diabetic kidney disease. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1410295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Jha, R.; Li, A.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Zhai, Q.; Zhang, J. Probiotics (Lactobacillus plantarum HNU082) Supplementation Relieves Ulcerative Colitis by Affecting Intestinal Barrier Functions, Immunity-Related Gene Expression, Gut Microbiota, and Metabolic Pathways in Mice. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0165122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vähämiko, S.; Laiho, A.; Lund, R.; Isolauri, E.; Salminen, S.; Laitinen, K. The impact of probiotic supplementation during pregnancy on DNA methylation of obesity-related genes in mothers and their children. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, R.; Bailey, S.D.; Desbiens, K.; Belisle, A.; Montpetit, A.; Bouchard, C.; Pérusse, L.; Vohl, M.C.; Engert, J.C. Genetic variants of FTO influence adiposity, insulin sensitivity, leptin levels, and resting metabolic rate in the Quebec Family Study. Diabetes 2008, 57, 1147–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntean, C.; Sasaran, M.O.; Crisan, A.; Banescu, C. Effects of PPARG and PPARGC1A gene polymorphisms on obesity markers. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 962852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Chen, M.; Zhuang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Qian, Y.; Xu, J.; Fan, J. Genetic associations between gut microbiota and type 2 diabetes mediated by plasma metabolites: A Mendelian randomization study. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1430675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Gao, Y.; Wu, H.; Huang, X. The causal relationship between gut microbiota and type 2 diabetes: A two-sample Mendelian randomized study. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1255059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J. Physiological Notes: II. Contributions to the Theory of the Cell. a) Energids and Cells. Biol. Theory 2022, 17, 231–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhu, C.; Liu, T.; Zhang, W.; Liu, X.; Li, P.; Zhu, T. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate ameliorates glucolipid metabolism and oxidative stress in type 2 diabetic rats. Diabetes Vasc. Dis. Res. 2020, 17, 1479164120966998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.S.; Xia, Y.X.; Chen, B.S.; Du, Y.X.; Liu, K.L.; Zhang, H.J. Dihydro-Resveratrol Attenuates Oxidative Stress, Adipogenesis and Insulin Resistance in In Vitro Models and High-Fat Diet-Induced Mouse Model via AMPK Activation. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.S.; Lin, C.; Tseng, Y.-H.; Wang, S.-Y. Fruits of Rosa laevigata and its bio-active principal sitostenone facilitate glucose uptake and insulin sensitivity in hepatic cells via AMPK/PPAR-γ activation. Phytomedicine Plus 2021, 1, 100109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, K.H.; Yee, G.S.; Candasamy, M.; Tan, S.C.; Md, S.; Abdul Majeed, A.B.; Bhattamisra, S.K. Catalpol Ameliorates Insulin Sensitivity and Mitochondrial Respiration in Skeletal Muscle of Type-2 Diabetic Mice Through Insulin Signaling Pathway and AMPK/SIRT1/PGC-1α/PPAR-γ Activation. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Jiang, W.; Yu, B.; Liang, H.; Mao, S.; Hu, X.; Feng, Y.; Xu, J.; Chu, L. Quercetin improves cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury by promoting microglia/macrophages M2 polarization via regulating PI3K/Akt/NF-κB signaling pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 168, 115653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.C.; Huang, S.Y.; Chan, S.T.; Liao, J.W.; Yeh, S.L. Combination of β-carotene and quercetin against benzo[a]pyrene-induced pro-inflammatory reaction accompanied by the regulation of antioxidant enzyme activity and NF-κB translocation in Mongolian gerbils. Eur. J. Nutr. 2015, 54, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thadhani, V.M. Resveratrol in management of diabetes and obesity: Clinical applications, bioavailability, and nanotherapy. In Resveratrol—Adding Life to Years, Not Adding Years to Life; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019; Volume 10, pp. 1–166. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, C.-F.; Chen, G.-W.; Chen, Y.-C.; Shen, C.-K.; Lu, D.-Y.; Yang, L.-Y.; Chen, J.-H.; Yeh, W.-L. Regulatory Effects of Quercetin on M1/M2 Macrophage Polarization and Oxidative/Antioxidative Balance. Nutrients 2022, 14, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramadan, H.; Moustafa, N.; Ahmed, R.R.; El-Shahawy, A.A.G.; Eldin, Z.E.; Al-Jameel, S.S.; Amin, K.A.; Ahmed, O.M.; Abdul-Hamid, M. Therapeutic effect of oral insulin-chitosan nanobeads pectin-dextrin shell on streptozotocin-diabetic male albino rats. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Qiu, J.; Zhang, J.; Yang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y. Association between dietary antioxidant capacity and type 2 diabetes mellitus in Chinese adults: A population-based cross-sectional study. Nutr. Metab. 2024, 21, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ming, J.; Ye, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Yang, X.; Shao, X.; Qiang, J.; Xu, P. Optimal dietary curcumin improved growth performance, and modulated innate immunity, antioxidant capacity and related genes expression of NF-κB and Nrf2 signaling pathways in grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) after infection with Aeromonas hydrophila. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020, 97, 540–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahin, E.; Orhan, C.; Sahin, N.; Padigaru, M.; Morde, A.; Lal, M.; Dhavan, N.; Erten, F.; Bilgic, A.A.; Ozercan, I.H.; et al. Lutein/Zeaxanthin Isomers and Quercetagetin Combination Safeguards the Retina from Photo-Oxidative Damage by Modulating Neuroplasticity Markers and the Nrf2 Pathway. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cui, K.; Wang, X.; Tong, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhu, Y.; You, Q.; Jiang, Z.; Guo, X. Novel Hydrogen Sulfide Hybrid Derivatives of Keap1-Nrf2 Protein–Protein Interaction Inhibitor Alleviate Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Acute Experimental Colitis. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, M.O.M.; Evangelista-Silva, P.H.; Neves, N.N.; Moreno, L.G.; Santos, C.S.; Rocha, K.L.S.; Ottone, V.O.; Batista-da-Silva, B.; Dias-Peixoto, M.F.; Magalhães, F.C.; et al. Caloric restriction-induced weight loss with a high-fat diet does not fully recover visceral adipose tissue inflammation in previously obese C57BL/6 mice. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 45, 1353–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Baek, S.Y.; Jang, E.J.; Ku, S.K.; Kim, K.M.; Ki, S.H.; Kim, C.E.; Park, K.I.; Kim, S.C.; Kim, Y.W. Oxyresveratrol ameliorates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by regulating hepatic lipogenesis and fatty acid oxidation through liver kinase B1 and AMP-activated protein kinase. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2018, 289, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chávez-Ortega, M.P.; Almanza-Pérez, J.C.; Sánchez-Muñoz, F.; Hong, E.; Velázquez-Reyes, E.; Romero-Nava, R.; Villafaña-Rauda, S.; Pérez-Ontiveros, A.; Blancas-Flores, G.; Huang, F. Effect of Supplementation with Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids on Metabolic Modulators in Skeletal Muscle of Rats with an Obesogenic High-Fat Diet. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabirifar, R.; Rezaifar, A.; Binesh, F.; Bamdad, K.; Moradi, A. Curcumin, quercetin and atorvastatin protected against the hepatic fibrosis by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 40, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naiini, M.R.; Shahouzehi, B.; Azizi, S.; Shafiei, B.; Nazari-Robati, M. Trehalose-induced SIRT1/AMPK activation regulates SREBP-1c/PPAR-α to alleviate lipid accumulation in aged liver. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2024, 397, 1061–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azuma, N.; Mawatari, T.; Saito, Y.; Tsukamoto, M.; Sampei, M.; Iwama, Y. Effect of Continuous Ingestion of Bifidobacteria and Dietary Fiber on Improvement in Cognitive Function: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, Y.; Saito, Y.; Kadowaki, M.; Azuma, N.; Tsuge, D. Effect of Continuous Ingestion of Bifidobacteria and Inulin on Reducing Body Fat: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Parallel-Group Comparison Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 5025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, R.O.; Castro, P.R.; Fachi, J.L.; Nirello, V.D.; El-Sahhar, S.; Imada, S.; Pereira, G.V.; Pral, L.P.; Araújo, N.V.P.; Fernandes, M.F.; et al. Inulin diet uncovers complex diet-microbiota-immune cell interactions remodeling the gut epithelium. Microbiome 2023, 11, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewarsar, E.; Chaiyasut, C.; Lailerd, N.; Makhamrueang, N.; Peerajan, S.; Sirilun, S. Optimization of Mixed Inulin, Fructooligosaccharides, and Galactooligosaccharides as Prebiotics for Stimulation of Probiotics Growth and Function. Foods 2023, 12, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezzatpour, S.; Mondragon Portocarrero, A.D.C.; Cardelle-Cobas, A.; Lamas, A.; López-Santamarina, A.; Miranda, J.M.; Aguilar, H.C. The Human Gut Virome and Its Relationship with Nontransmissible Chronic Diseases. Nutrients 2023, 15, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L.W.; Cai, S.; Zhao, T.S.; Li, M.; Tian, Y. Green tea derivative (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) confers protection against ionizing radiation-induced intestinal epithelial cell death both in vitro and in vivo. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 161, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakadate, K.; Kawakami, K.; Yamazaki, N. Anti-Obesity and Anti-Inflammatory Synergistic Effects of Green Tea Catechins and Citrus β-Cryptoxanthin Ingestion in Obese Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyildiz, K.; Yilmaz, A.; Avci, U.; Toraman, M.N.; Yazici, Z.A. White Tea Consumption Alleviates Anthropometric and Metabolic Parameters in Obese Patients. Medicina 2024, 60, 1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D.; Pan, Y.; Yu, N.; Bai, Y.; Ma, R.; Mo, F.; Zuo, J.; Chen, B.; Jia, Q.; Zhang, D.; et al. Curcumin improves adipocytes browning and mitochondrial function in 3T3-L1 cells and obese rodent model. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2021, 8, 200974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weisberg, S.P.; Leibel, R.; Tortoriello, D.V. Dietary curcumin significantly improves obesity-associated inflammation and diabetes in mouse models of diabesity. Endocrinology 2008, 149, 3549–3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuengsamarn, S.; Rattanamongkolgul, S.; Luechapudiporn, R.; Phisalaphong, C.; Jirawatnotai, S. Curcumin extract for prevention of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 2121–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaikwawong, M.; Jansarikit, L.; Jirawatnotai, S.; Chuengsamarn, S. Curcumin extract improves beta cell functions in obese patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. Nutr. J. 2024, 23, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahjabeen, W.; Khan, D.A.; Mirza, S.A. Role of resveratrol supplementation in regulation of glucose hemostasis, inflammation and oxidative stress in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2022, 66, 102819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmers, S.; Konings, E.; Bilet, L.; Houtkooper, R.H.; van de Weijer, T.; Goossens, G.H.; Hoeks, J.; van der Krieken, S.; Ryu, D.; Kersten, S.; et al. Calorie restriction-like effects of 30 days of resveratrol supplementation on energy metabolism and metabolic profile in obese humans. Cell Metab. 2011, 14, 612–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.; Tam, C.C.; Rolston, M.; Alves, P.; Chen, L.; Meng, S.; Hong, H.; Chang, S.K.C.; Yokoyama, W. Quercetin Ameliorates Insulin Resistance and Restores Gut Microbiome in Mice on High-Fat Diets. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantadaki, A.E.; Linardakis, M.; Tsakiri, M.; Baliou, S.; Fragkiadaki, P.; Vakonaki, E.; Tzatzarakis, M.N.; Tsatsakis, A.; Symvoulakis, E.K. Benefits of Quercetin on Glycated Hemoglobin, Blood Pressure, PiKo-6 Readings, Night-Time Sleep, Anxiety, and Quality of Life in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantadaki, A.E.; Baliou, S.; Linardakis, M.; Vakonaki, E.; Tzatzarakis, M.N.; Tsatsakis, A.; Symvoulakis, E.K. Quercetin Intake and Absolute Telomere Length in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Novel Findings from a Randomized Controlled Before-and-After Study. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel Ghani, A.E.; Al-Saleem, M.S.M.; Abdel-Mageed, W.M.; AbouZeid, E.M.; Mahmoud, M.Y.; Abdallah, R.H. UPLC-ESI-MS/MS Profiling and Cytotoxic, Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, Antidiabetic, and Antiobesity Activities of the Non-Polar Fractions of Salvia hispanica L. Aerial Parts. Plants 2023, 12, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dittrich, M.; Jahreis, G.; Bothor, K.; Drechsel, C.; Kiehntopf, M.; Blüher, M.; Dawczynski, C. Benefits of foods supplemented with vegetable oils rich in α-linolenic, stearidonic or docosahexaenoic acid in hypertriglyceridemic subjects: A double-blind, randomized, controlled trail. Eur. J. Nutr. 2015, 54, 881–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vass, N.; Czegledi, L.; Javor, A. Significance of functional foods of animal origin in human health. Sci. Pap. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2008, 41, 263. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Becerra, K.; Barron-Cabrera, E.; Muñoz-Valle, J.F.; Torres-Castillo, N.; Rivera-Valdes, J.J.; Rodriguez-Echevarria, R.; Martinez-Lopez, E. A Balanced Dietary Ratio of n-6:n-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Exerts an Effect on Total Fatty Acid Profile in RBCs and Inflammatory Markers in Subjects with Obesity. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, M.; Finlin, B.S.; Unal, R.; Zhu, B.; Morris, A.J.; Shipp, L.R.; Lee, J.; Walton, R.G.; Adu, A.; Erfani, R.; et al. Omega-3 fatty acids reduce adipose tissue macrophages in human subjects with insulin resistance. Diabetes 2013, 62, 1709–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santurino, C.; López-Plaza, B.; Fontecha, J.; Calvo, M.V.; Bermejo, L.M.; Gómez-Andrés, D.; Gómez-Candela, C. Consumption of Goat Cheese Naturally Rich in Omega-3 and Conjugated Linoleic Acid Improves the Cardiovascular and Inflammatory Biomarkers of Overweight and Obese Subjects: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Chang, G.; Huang, J.; Wang, Y.; Gao, Q.; Cheng, X.; Liu, J.; Shen, X. cis-9, trans-11-Conjugated Linoleic Acid Exerts an Anti-inflammatory Effect in Bovine Mammary Epithelial Cells after Escherichia coli Stimulation through NF-κB Signaling Pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Ha, A.W. Intakes of Dairy and Soy Products and 10-Year Coronary Heart Disease Risk in Korean Adults. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cakir, B.; Tunali-Akbay, T. Potential anticarcinogenic effect of goat milk-derived bioactive peptides on HCT-116 human colorectal carcinoma cell line. Anal. Biochem. 2021, 622, 114166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Bhatia, Z.; Seshadri, S. Formulated chitosan microspheres remodelled the altered gut microbiota and liver miRNA in diet-induced Type-2 diabetic rats. Carbohydr. Res. 2025, 547, 109301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Santamarina, A.; Mondragon, A.d.C.; Lamas, A.; Miranda, J.M.; Franco, C.M.; Cepeda, A. Animal-Origin Prebiotics Based on Chitin: An Alternative for the Future? A Critical Review. Foods 2020, 9, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, C.-S.; Kim, J.-A.; Bak, S.-S.; Byun, H.-G.; Kim, S.-K. Anti-obesity effect of carboxymethyl chitin by AMPK and aquaporin-7 pathways in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2011, 22, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bays, H.E.; Evans, J.L.; Maki, K.C.; Evans, M.; Maquet, V.; Cooper, R.; Anderson, J.W. Chitin-glucan fiber effects on oxidized low-density lipoprotein: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 67, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Sun, T.; Wang, L. Chitosan oligosaccharide improves the therapeutic efficacy of sitagliptin for the therapy of Chinese elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2017, 13, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyrinck, A.M.; Possemiers, S.; Verstraete, W.; De Backer, F.; Cani, P.D.; Delzenne, N.M. Dietary modulation of clostridial cluster XIVa gut bacteria (Roseburia spp.) by chitin–glucan fiber improves host metabolic alterations induced by high-fat diet in mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012, 23, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Dan, N.; Wang, Y.Q.; Gou, C.L. Protection effect of cis 9, trans 11-conjugated linoleic acid on oxidative stress and inflammatory damage in bovine mammary epithelial cells. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, Y.; Kano, K.; Kishino, S.; Nagao, T.; Shen, X.; Sato, C.; Hatakeyama, H.; Ota, Y.; Niibori, S.; Nomura, A.; et al. Dietary cis-9, trans-11-conjugated linoleic acid reduces amyloid β-protein accumulation and upregulates anti-inflammatory cytokines in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, C.A.; Baker, E.J.; Miles, E.A.; Calder, P.C. Conjugated Linoleic Acids Have Anti-Inflammatory Effects in Cultured Endothelial Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahbar, B.; Taghizadeh, A.; Paya, H.; Daghigh Kia, H. Conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) supplementation effects on performance, metabolic parameters and reproductive traits in lactating Holstein dairy cows. Vet. Res. Forum 2021, 12, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, J.F.; Roberts-Lee, K.; Borcea, C.; Smith, H.M.; Midgette, Y.; Shah, R. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids attenuate inflammatory activation and alter differentiation in human adipocytes. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2019, 64, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacińska, M.; Zabielski, P.; Książek, M.; Szałaj, P.; Jarząbek, K.; Kojta, I.; Chabowski, A.; Błachnio-Zabielska, A.U. The Impact of OMEGA-3 Fatty Acids Supplementation on Insulin Resistance and Content of Adipocytokines and Biologically Active Lipids in Adipose Tissue of High-Fat Diet Fed Rats. Nutrients 2019, 11, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borja-Magno, A.; Guevara-Cruz, M.; Flores-López, A.; Carrillo-Domínguez, S.; Granados, J.; Arias, C.; Perry, M.; Sears, B.; Bourges, H.; Gómez, F.E. Differential effects of high dose omega-3 fatty acids on metabolism and inflammation in patients with obesity: Eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acid supplementation. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1156995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangouni, A.A.; Orang, Z.; Mozaffari-Khosravi, H. Effect of omega-3 supplementation on fatty liver and visceral adiposity indices in diabetic patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2021, 44, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Chen, C.-M.; Mu, S.-C.; Yang, S.-H.; Ju, Y.-M.; Li, S.-C. Medicinal Components in Edible Mushrooms on Diabetes Mellitus Treatment. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-Y.; Ho, K.-J.; Hsieh, Y.-J.; Wang, L.-T.; Mau, J.-L. Contents of lovastatin, γ-aminobutyric acid and ergothioneine in mushroom fruiting bodies and mycelia. Lwt 2012, 47, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, P.; Loganayagi, C. Antihyperglycemic activity of Agaricus bisporus mushroom extracts on alloxan induced diabetic rats. Int. J. Pharma Res. Health Sci. 2018, 6, 2475–2479. [Google Scholar]

- Elhusseiny, S.M.; El-Mahdy, T.S.; Awad, M.F.; Elleboudy, N.S.; Farag, M.M.S.; Yassein, M.A.; Aboshanab, K.M. Proteome Analysis and In Vitro Antiviral, Anticancer and Antioxidant Capacities of the Aqueous Extracts of Lentinula edodes and Pleurotus ostreatus Edible Mushrooms. Molecules 2021, 26, 4623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras-Bolívar, V.; García-Fontana, B.; García-Fontana, C.; Muñoz-Torres, M. Mechanisms Involved in the Relationship between Vitamin D and Insulin Resistance: Impact on Clinical Practice. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-C.; Chen, C.-M.; Ju, Y.-M.; Wu, Y.-C.; Hsieh, H.-M.; Yang, S.-H.; Su, C.-T.; Fang, T.-C.; Setyaningsih, W.; Li, S.-C. Effects of Consuming Pulsed UV Light-Treated Pleurotus citrinopileatus on Vitamin D Nutritional Status in Healthy Adults. Foods 2025, 14, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, H.; Guo, L.; Ma, C.; Kang, W. Regulating role of Pleurotus ostreatus insoluble dietary fiber in high fat diet induced obesity in rats based on proteomics and metabolomics analyses. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 136857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Yu, C.; Liu, Z.; Cui, X.; Guo, X.; Wang, H. Chemical Composition, Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Shiitake Mushrooms (Lentinus edodes). J. Fungi 2024, 10, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M.; Kumari, M.; Karn, S.K.; Bhambri, A.; Mahale, V.G.; Mahale, S. Submerged cultivation and phytochemical analysis of medicinal mushrooms (Trametes sp.). Front. Fungal Biol. 2024, 5, 1414349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harada, E.; Morizono, T.; Kanno, T.; Saito, M.; Kawagishi, H. Medicinal Mushroom, Grifola gargal (Agaricomycetes), Lowers Triglyceride in Animal Models of Obesity and Diabetes and in Adults with Prediabetes. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2020, 22, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunawardena, D.; Bennett, L.; Shanmugam, K.; King, K.; Williams, R.; Zabaras, D.; Head, R.; Ooi, L.; Gyengesi, E.; Münch, G. Anti-inflammatory effects of five commercially available mushroom species determined in lipopolysaccharide and interferon-γ activated murine macrophages. Food Chem. 2014, 148, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.M.; Woo, H.W.; Shin, M.H.; Koh, S.B.; Kim, H.C.; Kim, M.K. A prospective association between dietary mushroom intake and the risk of type 2 diabetes: The Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study-Cardiovascular Disease Association Study. Epidemiol. Health 2024, 46, e2024017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, L.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, M.; Tian, Y.; Dong, J.; Liao, L. Protective effect of Cordyceps sinensis against diabetic kidney disease through promoting proliferation and inhibiting apoptosis of renal proximal tubular cells. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2023, 23, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Song, J.; Teng, M.; Zheng, X.; Li, X.; Tian, Y.; Pan, M.; Li, Y.; Lee, R.J.; Wang, D. Antidiabetic and Antinephritic Activities of Aqueous Extract of Cordyceps militaris Fruit Body in Diet-Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Sprague Dawley Rats. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 9685257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Lu, Q.-Y.; Wu, H.; Cheng, Y.-L.; Kang, J.; Xu, Z.-G. The Intestinal Microbiota Composition in Early and Late Stages of Diabetic Kidney Disease. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e00382-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Gnanasambandan, R. Intestinal microbiome diversity of diabetic and non-diabetic kidney disease: Current status and future perspective. Life Sci. 2023, 316, 121414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohia, S.; Vlahou, A.; Zoidakis, J. Microbiome in Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD): An Omics Perspective. Toxins 2022, 14, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Xi, Y.; Yan, M.; Sun, C.; Tang, J.; Dong, X.; Yang, Z.; Wu, L. Lactiplantibacillus plantarum NKK20 Increases Intestinal Butyrate Production and Inhibits Type 2 Diabetic Kidney Injury through PI3K/Akt Pathway. J. Diabetes Res. 2023, 2023, 8810106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Li, K.; Lee, Y.; Chen, M. Preventive Effects of Lactobacillus Mixture against Chronic Kidney Disease Progression through Enhancement of Beneficial Bacteria and Downregulation of Gut-Derived Uremic Toxins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 7353–7366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaziri, N.D.; Wong, J.; Pahl, M.; Piceno, Y.M.; Yuan, J.; DeSantis, T.Z.; Ni, Z.; Nguyen, T.H.; Andersen, G.L. Chronic kidney disease alters intestinal microbial flora. Kidney Int. 2013, 83, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, Y.W.; Huang, Y.Y.; Tsai, S.Y.; Wang, J.Y.; Lin, J.H.; Syu, Z.J.; Wang, H.S.; Hsu, Y.C.; Chen, J.F.; Hsia, K.C.; et al. Probiotic Formula Ameliorates Renal Dysfunction Indicators, Glycemic Levels, and Blood Pressure in a Diabetic Nephropathy Mouse Model. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, L.R.; De Caterina, R.; Görman, U.; Allayee, H.; Kohlmeier, M.; Prasad, C.; Choi, M.S.; Curi, R.; de Luis, D.A.; Gil, Á.; et al. Guide and Position of the International Society of Nutrigenetics/Nutrigenomics on Personalised Nutrition: Part 1—Fields of Precision Nutrition. J. Nutr. Nutr. 2016, 9, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlmeier, M.; De Caterina, R.; Ferguson, L.R.; Görman, U.; Allayee, H.; Prasad, C.; Kang, J.X.; Nicoletti, C.F.; Martinez, J.A. Guide and Position of the International Society of Nutrigenetics/Nutrigenomics on Personalized Nutrition: Part 2—Ethics, Challenges and Endeavors of Precision Nutrition. J. Nutr. Nutr. 2016, 9, 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]