Abstract

Background: Nutritional support in patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is a clinical challenge. Hemodynamic instability and concerns about gut perfusion delay enteral nutrition (EN), resulting in frequent use of total parenteral nutrition (TPN). This study aimed to compare nutritional practices in patients on venoarterial (VA) vs. venovenous (VV) ECMO, and to evaluate the associations between prolonged TPN use, feeding status, circuit change frequency, length of stay, and survival. Methods: Retrospective cohort study of ECMO patients in a quaternary pediatric intensive care unit. Nutritional variables included route and amount of nutrition delivery. The primary outcome was the nutrition type (enteral vs. parenteral) in association with ECMO mode (VV vs. VA). Secondary outcomes included associations between nutrition variables (TPN by Day 14, lack of EN by Day 5 or 7) and circuit changes, ECMO duration, ICU/hospital length of stay (LOS), and mortality. Analyses by Mann–Whitney and chi-square tests. Multivariable Poisson regression was used to identify independent predictors of circuit change frequency. Results: Patients on VV ECMO achieved higher enteral intake than those on VA ECMO. Persistent need for TPN by Day 14 was associated with longer PICU LOS, hospital LOS, and ECMO duration and was independently associated with 71% higher circuit change frequency. Survival did not differ significantly by TPN duration or early EN exposure. Conclusions: VV ECMO patients received higher enteral nutrition. Persistent need for TPN by day 14 was associated with worse outcomes. These findings underscore the need for standardized, evidence-based feeding strategies in this population.

1. Introduction

Optimal nutritional support is a fundamental aspect of care in critically ill patients, influencing outcomes such as infection risk, wound healing, length of stay, and mortality [1,2]. In this population, early and adequate enteral nutrition delivery has been associated with improved survival and functional recovery [3,4,5].

Enteral nutrition (EN) is generally preferred over parenteral nutrition (PN) as it preserves gut integrity, modulates the immune response, and reduces infectious complications. However, in patients requiring advanced organ support such as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), achieving adequate and timely nutrition remains a major clinical challenge [6,7].

ECMO provides temporary cardiopulmonary support for patients with severe cardiac or respiratory failure refractory to conventional management. Two main configurations are used: veno-venous (VV) ECMO, which supports gas exchange in patients with isolated respiratory failure, and veno-arterial (VA) ECMO, which provides both cardiac and respiratory support in cases of severe circulatory compromise [8,9]. While advances in technology and critical care practices have improved survival [10], optimizing nutritional support for patients on ECMO remains a significant clinical challenge with reported usage of PN in up to 80% of patients on ECMO [11,12]. The physiological alterations associated with ECMO such as systemic inflammation, altered hemodynamics, and changes in gastrointestinal perfusion can delay both the initiation and advancement of enteral feeding [13,14].

In particular, patients supported on VA ECMO are often perceived to be at higher risk for gut ischemia and feeding intolerance due to compromised bowel perfusion. As a result, clinicians may hesitate to initiate or advance EN, leading to heterogeneous nutritional practices and frequent suboptimal caloric and protein delivery throughout the ECMO course [6,11].

Although several studies have described feeding practices in ECMO populations, few have directly compared nutritional strategies between venovenous (VV) and veno-arterial (VA) ECMO configurations. Given the differences in underlying pathophysiology, respiratory failure in VV ECMO vs. combined cardiac and circulatory failure in VA ECMO, understanding how ECMO mode influences nutrition delivery is clinically relevant. The study aimed to address two clinically important questions; (1) Do children supported with VV vs. VA ECMO receive different patterns of enteral and parenteral nutrition? and (2) Are delayed enteral feeding and prolonged dependence on TPN associated with greater circuit dysfunction or worse clinical outcomes?

We aimed to identify barriers that may limit advancement of enteral feeding, thereby informing future feeding protocols and optimizing nutritional care for this high-risk population.

2. Materials and Methods

This is a retrospective cohort analysis of index admissions to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) at a single quaternary institution. We included pediatric patients (aged one month to 18 years) who required veno-venous (VV) or veno-arterial (VA) ECMO, from January 2015 through December 2024. Inclusion criteria were;

(1) ECMO support for more than 7 days. (2) Patients received calculable nutrition intake by feeding tube or parenteral route. Patients with missing data, congenital heart disease, or post-cardiopulmonary bypass were excluded. The Institutional Review Board at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston (IRB: H-5692) approved this study’s ethical considerations in February 2025.

Data points were collected from information documented in the electronic medical record (EMR), encompassing patients’ demographics, admission anthropometric measurements [weight (kilograms), height/length (cm)] upon admission, PICU length of stay (LOS), hospital LOS, ECMO mode and duration, mortality, and nutrition-related variables such as route, volume, macronutrient intake, and documented barriers to initiating or advancing enteral feeds.

2.1. Nutrition Assessment

Anthropometric data were used to calculate z-scores for nutritional assessment. For patients younger than two years of age we utilized growth curves by the World Health Organization (WHO), and for those older than two years we utilized growth curves according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [15] Specifically, the anthropometric measures employed were weight-for-age (WFA), height-for-age (HFA) z scores, and body mass index-for-age (BMI/A) or weight-for-length (WFL) z scores.

Nutritional status was categorized as follows: underweight, WFA z score < −2.0; acute malnutrition, defined as a weight for height z score < −2.0; chronic malnutrition, HFA z score < −2.0; overweight, weight for height z score > 2.0; and obesity, weight for height z score > 3.0 [16,17].

All nutritional categories were based on age and sex.

2.2. Nutrition Support (Amount and Delivery Methods)

We collected data from the electronic medical record on nutritional variables, including macronutrient (calories and protein) prescriptions by the clinical dietitians and the medical team, actual daily caloric and protein delivery, route of delivery: enteral (EN) vs. parenteral (PN), and timing of the clinical dietitian’s evaluation. Nutritional intake was calculated on days 1, 3, 5, and 7, with day 0 being the day of ECMO initiation.

Using the Schofield equation, basal metabolic rate (BMR) was used to estimate the daily recommended caloric intake [18].

Goal protein intake was calculated as 2–3 g/kg for 0–2 years, 1.5–2 g/kg for 2–13 years, and 1.5 g/kg/day for 13–18 years [19]. We identified nutrition goal adequacy as 60% of the recommended daily caloric and protein intake and calculated it as [(intake/recommended) × 100] [20]. We compared nutritional adequacy and route of nutrition delivery across several subgroups, including ECMO mode (VV vs.VA ECMO), age (<2 years vs. >2 years), and nutritional status (underweight vs. non-underweight).

2.3. ECMO Outcomes

The primary outcome is the association between ECMO mode (VV vs. VA) and achieving goal nutrition by day 7 of ECMO support, via the enteral vs. parenteral route.

Secondary outcomes are relationships between nutrition-related variables, including persistent need of TPN and receipt of TPN by Days 7 and 14, and absence of enteral nutrition during the first 5 or 7 days of ECMO support, and several clinically relevant endpoints. These endpoints included the total number of ECMO circuit changes, duration of ECMO support, ICU and hospital LOS, and survival to hospital discharge. A multivariable analysis included nutrition variables, ECMO type, age, and sex.

These nutrition variables were selected a priori based on their clinical relevance and established use in ECMO nutrition research. TPN use at Days 7 and 14 reflects sustained dependence on parenteral nutrition and serves as a practical marker of feeding intolerance and illness severity during the early ECMO course. Similarly, absence of enteral nutrition by Days 5 and 7 captures early feeding practices and aligns with guideline-recommended time windows for evaluating readiness for enteral feeding in critically ill children. Together, these variables represent key milestones in nutritional progression and provide meaningful insight into the interaction between feeding tolerance, ECMO physiology, and clinical outcome.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient demographics, nutritional variables, and clinical outcomes. Continuous variables were expressed as median (interquartile range) and compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables were summarized as counts and percentages and compared using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate.

To examine the independent association between nutritional variables and ECMO circuit dysfunction (circuit change frequency), a multivariable Poisson regression model was constructed with circuit change frequency as the dependent variable. Independent variables included receipt of total parenteral nutrition (TPN) by Day 7, receipt of TPN by Day 14, and absence of enteral feeding during the first 5 days and first 7 days of ECMO support. Regression coefficients (β) were exponentiated to obtain incidence rate ratios (IRR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using Stat View Version 5.0.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and Python (v3.11, statsmodels package).

3. Results

During the study period, 115 patients met the inclusion criteria, of whom 51% were females. The median (interquartile range (IQR)) age was 3 years (1–11.75), and the median weight was 14.7 kg (8.9–38.8). The median ICU LOS was 46 days (26–75.8), and the median ECMO duration was 17 (9–30) days. Among the cohort, 20% received VA ECMO, and 80% received VV ECMO.

Primary indications for ECMO initiation included acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) of mixed etiology (74%, n = 85), asthma (9.5%, n = 11), pulmonary hypertension (7.8%, n = 9), sepsis (4.3%, n = 5), air leak syndrome (1.7%, n = 2), and mediastinal mass (0.8%, n = 1).

A total of 53% (n = 61) of patients were evaluated by a dietitian within 48 h of ECMO initiation.

The prevalence of malnutrition categories was as follows: underweight (16%), obesity (15%), and chronic malnutrition (20%). Overall mortality for the cohort was 26% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Demographics for Nutrition Support.

3.1. Nutrition Support

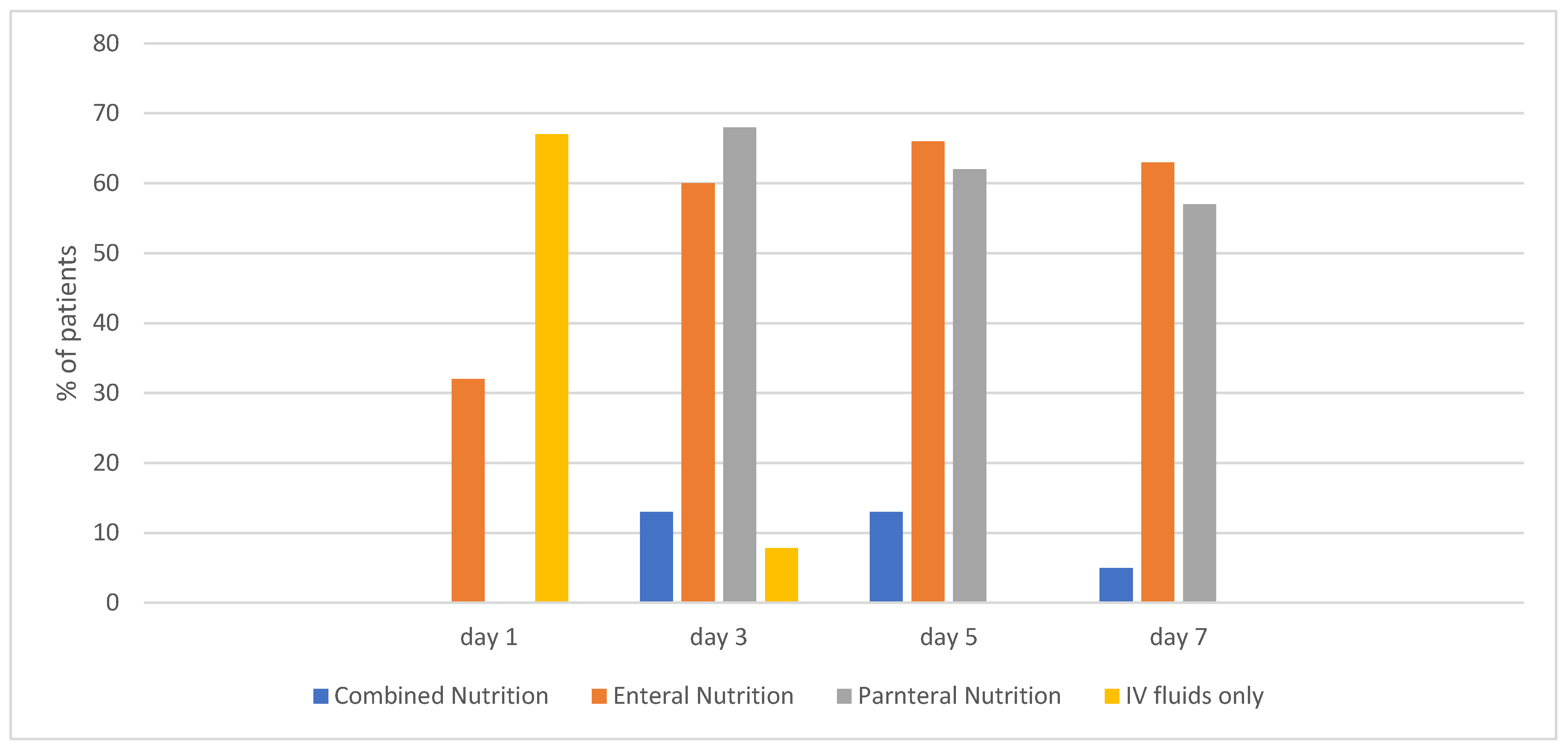

On day 1 of ECMO, 33% (n = 38) of patients were on an enteral diet. That percentage increased to 63% (n = 73) by day 7 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Percentage of patients receiving each type of Nutrition Support by day.

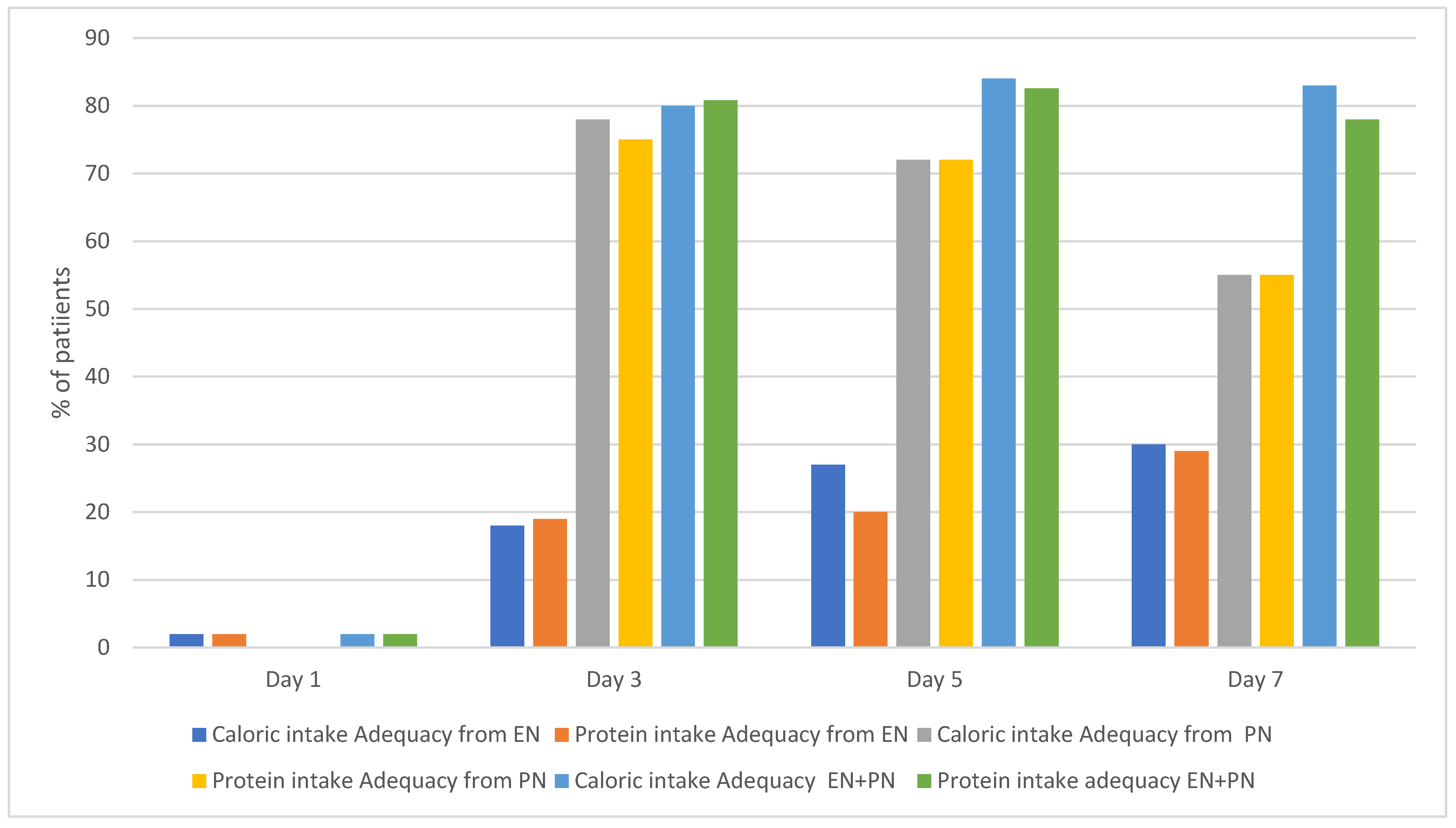

By day 7 of ECMO, 30% of patients achieved goal nutrition adequacy (60% of protein and caloric needs) through EN. This percentage increased to ~80% of this cohort when calculating EN and PN intake.

The percentages of patients who achieved goal nutrition adequacy on EN alone, PN alone, and EN+PN on days 1, 3, 5, and 7 are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Percentage of patients who achieved caloric and protein intake adequacy.

Patients who had been receiving EN within 48 h prior to ECMO were more likely to remain on EN by day 1 of ECMO compared with those who were not previously enterally fed (47.5% vs. 16.7%; p < 0.0005). This difference was no longer significant by day 3 of ECMO (59% vs. 63%; p = 0.3).

3.1.1. Nutritional Adequacy by ECMO Mode (VA vs. VV)

We compared the achievement of optimal nutrition adequacy between patients supported on VA ECMO (n = 27) and VV ECMO (n = 88).

On Day 3, patients on VA ECMO achieved significantly lower enteral protein and caloric intake than those on VV ECMO: 0 (0–9) vs. 10 (0–40), p = 0.02, and 0 (0–12) vs. 16 (10–50), p = 0.01, respectively. Similar trends were observed on day 5, 0 (0–26) vs. 11 (0–63) p = 0.07 and 11 (0–32) vs. 14 (0–76) p = 0.02 for protein and caloric intake adequacy, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Protein and caloric adequacy in VA vs. VV patients.

When total intake from combined EN and PN was analyzed, patients on VA ECMO received higher protein and caloric intake compared with those on VV ECMO (Table 2). On day 5, protein and caloric intake adequacy were 138 (115–160) vs. 108 (72–140) p = 0.04 and 126 (94–157) vs. 112 (81–140) p = 0.3, respectively. By day 7, protein adequacy remained higher in VA ECMO patients 135 (113–143) vs. 105 (57–143) p = 0.03, as did caloric adequacy 137 (104–168) vs. 111 (80–129) p = 0.002 (Table 2).

3.1.2. Nutritional Adequacy by Age Groups (Age < vs. >2 Years Old)

In this cohort, no statistically significant differences were observed in EN provision practices between patients younger than 2 years and those 2 years or older.

However, patients under 2 years of age had higher caloric adequacy from EN+PN, 140 (108–167) vs. 103 (78–129), p = <0.001 on day 5, and 136 (115–168) vs. 106 (82–127), p < 0.001 on day 7. This difference was not observed for protein intake (Table 3).

Table 3.

Protein and caloric adequacy in <2 years vs. >2 years patients.

3.1.3. Nutritional Adequacy by Nutritional Status (Underweight vs. Non-Underweight Patients)

Comparing underweight and non-underweight patients, there was no difference in enteral protein and calorie intake adequacy between underweight and non-underweight patients on days 1, 3, and 5. Compared to underweight patients, non-underweight patients were more likely to receive higher caloric and protein intake enterally 0 (0–2) vs. 13 (0–62), p = 0.02 and 0 (0–7) vs. 24 (0–89), p = 0.04 for protein and caloric intake adequacy on day 7, respectively (Table 4).

Table 4.

Protein and caloric adequacy in underweight vs.non-underweight patients.

The overall intake from EN+PN calculations showed higher caloric intake of underweight vs. non-underweight patients, 145 (123–177) vs. 111 (18–136) p = 0.006 and 140 (88–177) vs. 115 (68–135) p = 0.09 on day 5 and 7, respectively. There was a statistically significant difference in protein intake between these two groups (Table 4).

3.2. Outcomes in Association with Nutrition Practices

In a multivariable Poisson regression model including all nutritional variables, ECMO type, sex and age, we found that the persistent need of TPN by Day 14 was independently associated with an increased rate of circuit changes (IRR 1.71, 95% CI 1.19–2.47, p = 0.004).

Other nutritional variables, including TPN by Day 7 and absence of enteral feeding during the first 5 or 7 days, were not significantly associated with circuit change frequency (Table 5).

Table 5.

Multivariable Poisson Regression Assessing the Association Between Nutritional Variables and Circuit Change Frequency in ECMO Patients.

Patients receiving TPN on day 14 of ECMO (44%, n = 51) had significantly longer PICU LOS compared to those who did not receive TPN, 58.0 (39.0–77.5) vs. 38.5 (20.8–66.5) days, p = 0.007, longer hospital LOS 77.6 (45.7–103.6) vs. 50.3 (29.0–83.0) days, p = 0.006, and longer ECMO duration 21.3 (13–32) vs. 13 (8–22.6) days, p = 0.007 (Table 6).

Table 6.

Clinical outcomes in association with TPN intake on Day 14 of ECMO:.

No statistically significant difference in mortality was observed between patients who received EN at any time during the first 5 days of ECMO and those who did not. The same finding was observed when comparing patients who received EN at any time during the first 7 days vs.those who did not (Table 6).

4. Discussion

In this cohort of pediatric patients on ECMO, ~30% achieved the nutritional adequacy goal, using EN alone, by the end of the first week of ECMO. At the same time, ~80% of patients achieved the same goal with EN+PN.

These findings are not consistent across VA and VV ECMO patients. Our analysis demonstrated a clear disparity in nutritional practices between the two modes: patients supported with VV ECMO were significantly more likely to achieve nutritional adequacy via the enteral route than those on VA ECMO. This difference underscores the persistent challenge of safely initiating and advancing enteral nutrition in patients receiving VA ECMO, who often have greater hemodynamic instability and higher risk of feeding intolerance [6,11].

In contrast, patients on VA ECMO in this study achieved greater overall nutritional adequacy when considering combined EN and PN delivery. On average, VA ECMO patients received 135% of their protein goals and 137% of their caloric goals, compared with 105% and 111%, respectively, among VV ECMO patients. This observation raises important questions regarding how nutritional requirements are assessed in VV vs. VA ECMO patients, how underfeeding and overfeeding should be defined, how best to quantify caloric and protein delivery in this complex population, and how is the amount of nutrition delivery associated with clinical outcomes e.g., mortality.

In a study of adult patients on VV ECMO, higher protein intake during the first 14 days of therapy was independently associated with reduced mortality, highlighting the potential importance of early protein optimization in this population. In contrast, total energy intake over the same period was not significantly associated with clinical outcomes, suggesting that protein provision may play a more critical role than caloric delivery during the early course of ECMO support [21].

Despite the growing evidence that EN is associated with lower mortality and less PICU LOS, initiating and advancing enteral diet, especially in patients on VA ECMO, remains a challenge as shown in our analysis [5,22,23,24,25].

Advancing EN in critically ill patients is often hindered by a combination of physiological, clinical, and institutional barriers. Hemodynamic instability and high vasoactive requirements raise concerns about mesenteric hypoperfusion and the risk of intestinal ischemia [26].

As a result, many ECMO patients, especially those on VA support, experience delayed advancement to goal enteral nutrition despite emerging evidence supporting its safety and benefits in hemodynamically stable patients [6,11,27].

In this cohort of patients, gastric intolerance, emesis, and abdominal distention are commonly documented reasons for stopping the feeds and often lead to cautious advancement or prolonged reliance on PN with or without enteral trophic feeding. Additionally, we found frequent interruptions for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures and imaging studies that halt or at least delay the progression of feeds.

Interestingly, in our analysis, we found that patients who were on an enteral diet within 2 days before ECMO initiation were more likely to receive an enteral diet on Day 1 of ECMO, which might be explained by a higher provider comfort level to initiate enteral diet, given the recent history of enteral feeding intolerance.

Gut failure is common in critically ill patients and reflects the complex interplay of shock, inflammation, and impaired splanchnic perfusion [28,29]. Because ECMO is reserved for patients who have already failed conventional therapies [8,9], these patients are initiated on ECMO support with significant physiologic instability. Moreover, ECMO itself can trigger a systemic inflammatory response and alter gut perfusion, further compromising intestinal barrier integrity [13,14,29]. As a result, patients supported with ECMO are at particularly high risk for gut dysfunction and its associated complications. This hypothesis has been studied in preclinical studies. In a neonatal porcine model, investigators reported that initiating ECMO in healthy piglets led to intestinal barrier dysfunction and bacterial translocation, resulting from increased gut permeability. The authors proposed that barrier dysfunction may serve as a primary initiator or amplifier of ECMO-related systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), rather than merely representing a secondary epiphenomenon associated with loss of mucosal integrity as part of ECMO-induced multisystem dysfunction [30]. In a clinical study of neonates, Piena et al. demonstrated that intestinal integrity is impaired in infants supported with ECMO and that the introduction of enteral nutrition did not further deteriorate intestinal integrity. This notable finding challenges the long-standing concern that feeding may exacerbate gut injury. Instead, it suggests that enteral nutrition can be safely initiated in critically ill neonates receiving ECMO support [31].

Despite the lack of clinical trials, many observational studies have shown safe enteral diet in ECMO patients [4,32,33]. Hence, enteral nutrition, when appropriate, is recommended by guidelines [3,19,27,34].

In our study, reasons for delaying or pausing feeds included constipation, abdominal distension, emesis, and nausea. No severe gastrointestinal complications, e.g., necrotizing enterocolitis, bowel ischemia, etc., were documented in relation to the enteral diet.

These findings call for larger, prospective, randomized studies to examine gut barrier integrity markers, enteral diet feasibility, safety, and outcomes in this heterogeneous population.

When EN is not achievable, parenteral nutrition is often used to augment nutritional intake [12,35]. The literature shows better clinical outcomes in PICU patients when 60% of caloric and protein needs are met in the first week [2,19,36]. Clinicians may find it difficult to achieve this goal with EN alone. Hence, PN is widely used [12,35].

In our analysis, 80% of the cohort achieved the nutritional goals when TPN intake was combined with EN. The primary concern with overutilizing TPN is its side effect profile, i.e., immune dysregulation, microbiome dysfunction, increased risk of sepsis, electrolyte imbalance, and liver dysfunction [37,38,39,40,41].

The effects of delayed enteral nutrition and prolonged parenteral nutrition use during ECMO remain largely unexamined. An observational study in adults on ECMO reported a higher risk of circuit dysfunction among patients on PN [40].

In our study, patients with persistent PN requirements during the first 2 weeks of ECMO had a higher rate of circuit changes (IRR 1.76, 95% CI 1.22–2.52, p = 0.002).

Although statistically significant, this finding does not establish causation or independent association, as other factors, such as severe sepsis, multiorgan failure, immune dysregulation, and coagulopathy, may confound the results. Prospective large-scale studies are needed to explore the relationships among TPN, inflammation, immune dysregulation, coagulopathy, and circuit dysfunction in ECMO patients.

The literature shows better outcomes in patients who tolerate early enteral nutrition compared to those who don’t [5,25,32]. In this study, patients with persistent need for PN, had longer Hospital LOS, PICU LOS, and ECMO LOS. There was no difference in mortality in relation to different nutrition provision status (Table 6).

These findings have several practical implications for clinical nutrition management in ECMO patients. Identifying patients at risk for delayed enteral feeding—particularly those supported with VA ECMO—may allow earlier implementation of targeted nutrition strategies. For example, early stratification based on ECMO mode, hemodynamic stability, and feeding tolerance in the first 48–72 h could help determine which patients may benefit from more proactive TPN initiation vs. cautious but earlier EN trials. Our results also suggest that persistent TPN dependence by Day 14 is associated with greater circuit instability, highlighting the importance of close monitoring and timely reassessment of feeding readiness. Integrating these insights into structured feeding pathways may support more consistent decision-making around EN advancement, reduce unnecessary delays in enteral initiation, and help mitigate the metabolic consequences of prolonged underfeeding. Ultimately, applying individualized nutrition strategies informed by ECMO configuration and early feeding patterns may improve both nutritional adequacy and broader clinical outcomes.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we observed that patients supported with VV ECMO were more likely to receive and advance enteral nutrition than those on VA ECMO. The need for prolonged parenteral nutrition, particularly by Day 14, was associated with a higher rate of circuit dysfunction, longer ECMO duration and extended ICU and hospital stays, although not with increased mortality.

Early enteral feeding initiation remained limited, and a significant proportion of patients did not achieve enteral nutrition within the first week of ECMO. These findings underscore the challenges of achieving adequate nutrition during ECMO support and highlight the need for objective criteria to guide safe advancement of enteral nutrition in this population.

Future research should aim to identify strategies to safely advance enteral nutrition, reduce dependence on parenteral support, and better understand the metabolic and inflammatory consequences of varying nutrition practices in ECMO patients.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, its retrospective single-center design limits the ability to infer causality and may introduce selection and documentation bias. Second, variability in feeding practices among providers and the absence of a standardized feeding protocol could have influenced the timing and advancement of nutrition. Although our multivariable model adjusted for several nutrition-related and demographic factors, we were unable to control for important clinical confounders such as illness severity scores, vasoactive support, and underlying diagnosis because these variables were not consistently available in our retrospective dataset. Finally, because this analysis was limited to patients with complete nutritional and ECMO data, the findings may not be generalizable to all ECMO populations or to other institutions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M., J.A.C.-B. and A.O.; methodology, M.M. and J.A.C.-B.; software, N.K.; validation, M.M., J.S., S.N., N.C., K.M. and N.K.; formal analysis, M.M., N.K. and J.A.C.-B.; investigation, M.M., N.C., C.B., B.P., K.M., J.S. and S.N.; resources, M.M., C.B. and B.P.; data curation, M.M., N.C., K.M., J.S., C.B., B.P. and S.N.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.; writing—review and editing, M.M., N.C., K.M., J.S., S.N., N.K., J.A.C.-B. and A.O.; visualization, M.M.; supervision, A.O.; project administration, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by internal funding from the Division of Critical Care, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, and Texas Children’s Hospital.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Institutional Review Board at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston (IRB: H-5692) approved this study’s ethical considerations in 20 February 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ECMO | extracorporeal membrane oxygenation |

| VA | venoarterial |

| VV | venovenous |

| EN | enteral nutrition |

| PN | parenteral nutrition |

| TPN | total parenteral nutrition |

References

- Toh, T.S.W.; Ong, C.; Mok, Y.H.; Mallory, P.; Cheifetz, I.M.; Lee, J.H. Nutrition in Pediatric Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: A Narrative Review. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 666464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, N.M.; Bechard, L.J.M.; Cahill, N.R.; Wang, M.M.; Day, A.M.; Duggan, C.P.; Heyland, D.K.M. Nutritional practices and their relationship to clinical outcomes in critically ill children—An international multicenter cohort study. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 40, 2204–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wales, P.W.; Allen, N.; Worthington, P.; George, D.; Compher, C. A.S.P.E.N. clinical guidelines: Support of pediatric patients with intestinal failure at risk of parenteral nutrition-associated liver disease. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2014, 38, 538–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrillo-Albarano, T.; Pettignano, R.; Asfaw, M.; Easley, K. Use of a feeding protocol to improve nutritional support through early, aggressive, enteral nutrition in the pediatric intensive care unit*. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 7, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikhailov, T.A.; Kuhn, E.M.; Manzi, J.; Christensen, M.; Collins, M.; Brown, A.; Dechert, R.; Scanlon, M.C.; Wakeham, M.K.; Goday, P.S. Early Enteral Nutrition Is Associated with Lower Mortality in Critically Ill Children. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2014, 38, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofheinz, S.B.; Núñez-Ramos, R.; Germán-Díaz, M.; Melgares, L.O.; Arroba, C.M.A.; López-Fernández, E.; Moreno-Villares, J.M. Which is the best route to achieve nutritional goals in pediatric ECMO patients? Nutrition 2022, 93, 111497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneeweiss-Gleixner, M.; Scheiner, B.; Semmler, G.; Maleczek, M.; Laxar, D.; Hintersteininger, M.; Hermann, M.; Hermann, A.; Buchtele, N.; Schaden, E.; et al. Inadequate Energy Delivery Is Frequent among COVID-19 Patients Requiring ECMO Support and Associated with Increased ICU Mortality. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, K.; Singhal, N. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in children: A brief review. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2022, 58, 1525–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.C. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Severe Pediatric Respiratory Failure. Respir. Care 2017, 62, 732–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuhang, Y.; Ni, Y.; Tiening, Z.; Lijie, W.; Wei, X.; Chunfeng, L. Functional status of pediatric patients after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: A five-year single-center study. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 917875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresen, E.; Naidoo, O.; Hill, A.; Elke, G.; Lindner, M.; Jonckheer, J.; De Waele, E.; Meybohm, P.; Modir, R.; Patel, J.J.; et al. Medical nutrition therapy in patients receiving ECMO: Evidence-based guidance for clinical practice. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2022, 47, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, L.B.; Ariagno, K.; Smallwood, C.D.; Hong, C.; Arbuthnot, M.; Mehta, N.M. Nutrition Delivery During Pediatric Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Therapy. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2018, 42, 1133–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, J.E.; Fanning, J.P.; McDonald, C.I.; McAuley, D.F.; Fraser, J.F. The inflammatory response to extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO): A review of the pathophysiology. Crit. Care 2016, 20, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatami, S.; Hefler, J.; Freed, D.H. Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in the Context of Extracorporeal Cardiac and Pulmonary Support. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 831930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, J.H.; Roumiantsev, S.; Singh, R. PediTools Electronic Growth Chart Calculators: Applications in Clinical Care, Research, and Quality Improvement. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e16204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, S.K.; Gudivada, K.K.; Krishna, B. Assessment of Nutritional Status in the Critically Ill. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 24, S152–S156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, S.S.; Juarez, M.D.; Vega, M.W.; Canada, N.L. Pediatric Malnutrition. Putting the New Definition and Standards Into Practice. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2015, 30, 609–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, W.N. Predicting basal metabolic rate, new standards and review of previous work. Hum. Nutr. Clin. Nutr. 1985, 39, 5–41. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, N.M.; Compher, C.; ASPEN Board of Directors. A.S.P.E.N. Clinical Guidelines: Nutrition Support of the Critically Ill Child. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2009, 33, 260–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansour, M.; Knebusch, N.; Daughtry, J.; Fogarty, T.P.; Lam, F.W.; Orellana, R.A.; Lai, Y.C.; Erklauer, J.; Coss-Bu, J.A. Feasibility of Achieving Nutritional Adequacy in Critically Ill Children with Critical Neurological Illnesses (CNIs)?—A Quaternary Hospital Experience. Children 2024, 11, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelekhaty, S.; Gessler, J.; Dante, S.; Rector, N.; Galvagno, S.; Stachnik, S.; Rabin, J.; Tabatabai, A. Nutrition and outcomes in venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: An observational cohort study. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2024, 40, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohman, K.; Zhu, H.; Maizlin, I.; Williams, R.F.; Guner, Y.S.; Russell, R.T.; Harting, M.T.; Vogel, A.M.; Starr, J.P.; Johnson, D.; et al. A Multicenter Study of Nutritional Adequacy in Neonatal and Pediatric Extracorporeal Life Support. J. Surg. Res. 2020, 249, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, G.; González, E.; Zamora, L.; Fernández, S.N.; Sánchez, A.; Bellón, J.M.; Santiago, M.J.; Solana, M.J. Early Enteral Nutrition and Gastrointestinal Complications in Pediatric Patients on Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2021, 74, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanekamp, M.N.; Spoel, M.; Sharman-Koendjbiharie, I.; Peters, J.W.B.; Albers, M.J.I.J.; Tibboel, D. Routine enteral nutrition in neonates on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation*. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2005, 6, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greathouse, K.C.; Sakellaris, K.T.; Tumin, D.; Katsnelson, J.; Tobias, J.D.; Hayes, D.; Yates, A.R. Impact of Early Initiation of Enteral Nutrition on Survival During Pediatric Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2017, 42, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, E.D.; Absah, I.; Steien, D.B.; Grothe, R.; Crow, S. Vasopressors and Enteral Nutrition in the Survival Rate of Children During Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2022, 75, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.E.; Munoz, E.; Al Dabbous, T.; Harris, E.; O’callaghan, M.; Raman, L. Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Guidelines for the Provision and Assessment of Nutritional Support in the Neonatal and Pediatric ECMO Patient. ASAIO J. 2022, 68, 875–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sertaridou, E.; Papaioannou, V.; Kolios, G.; Pneumatikos, I. Gut failure in critical care: Old school vs. new school. Ann. Gastroenterol. Q. Publ. Hell. Soc. Gastroenterol. 2015, 28, 309–322. [Google Scholar]

- Soranno, D.E.; Coopersmith, C.M.; Brinkworth, J.F.; Factora, F.N.F.; Muntean, J.H.; Mythen, M.G.; Raphael, J.; Shaw, A.D.; Vachharajani, V.; Messer, J.S. A review of gut failure as a cause and consequence of critical illness. Crit. Care 2025, 29, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurundkar, A.R.; Killingsworth, C.R.; McIlwain, R.B.; Timpa, J.G.; Hartman, Y.E.; He, D.; Karnatak, R.K.; Neel, M.L.; Clancy, J.P.; Anantharamaiah, G.M.; et al. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Causes Loss of Intestinal Epithelial Barrier in the Newborn Piglet. Pediatr. Res. 2010, 68, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piena, M.; Albers, M.; Van Haard, P.; Gischler, S.; Tibboel, D. Introduction of enteral feeding in neonates on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation after evaluation of intestinal permeability changes. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1998, 33, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettignano, R.; Heard, M.; Davis, R.M.; Labuz, M.; Hart, M. Total enteral nutrition vs.total parenteral nutrition during pediatric extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Crit. Care Med. 1998, 26, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, J.L.M.; Jordan, J.; Rice, M.P.; Lee, A.E. Enteral Nutrition During Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in the Neonatal and Pediatric Populations: A Literature Review. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 24, e382–e389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaksic, T.; Hull, M.A.; Modi, B.P.; Ching, Y.A.; George, D.; Compher, C. A.S.P.E.N. clinical guidelines: Nutrition support of neonates supported with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2010, 34, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerstein, J.S.; Pane, C.R.; Sleeper, L.A.; Finnan, E.; Thiagarajan, R.R.; Mehta, N.M.; Mills, K.I. Nutrition Provision in Children with Heart Disease on Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO). Pediatr. Cardiol. 2024, 46, 2097–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, N.M.; Skillman, H.E.; Irving, S.Y.; Coss-Bu, J.A.; Vermilyea, S.; Farrington, E.A.; McKeever, L.; Hall, A.M.; Goday, P.S.; Braunschweig, C. Guidelines for the Provision and Assessment of Nutrition Support Therapy in the Pediatric Critically Ill Patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2017, 41, 706–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fivez, T.; Kerklaan, D.; Mesotten, D.; Verbruggen, S.; Wouters, P.J.; Vanhorebeek, I.; Debaveye, Y.; Vlasselaers, D.; Desmet, L.; Casaer, M.P.; et al. Early vs. Late Parenteral Nutrition in Critically Ill Children. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 1111–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, L.; Mehta, N.M.; Duggan, C.P. Timing of the initiation of parenteral nutrition in critically ill children. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2017, 20, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Puffelen, E.; Hulst, J.M.; Vanhorebeek, I.; Dulfer, K.; Berghe, G.V.D.; Verbruggen, S.C.A.T.; Joosten, K.F.M. Outcomes of Delaying Parenteral Nutrition for 1 Week vs Initiation Within 24 Hours Among Undernourished Children in Pediatric Intensive Care. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e182668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linares-Peña, S.; Poveda-Henao, C.; Saucedo-Jaramillo, L.; Garzón-Ruiz, J.P.; Lasso-Ossa, L.; Florez-Navas, C.; Rodriguez-Torres, G.; Robayo-Amortegui, H. Association between parenteral nutrition and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation circuit dysfunction in critically ill adults requiring extracorporeal life support: A retrospective cohort study. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdó, T.; García-Santos, J.A.; Rodríguez-Pöhnlein, A.; García-Ricobaraza, M.; Nieto-Ruíz, A.; Bermúdez, M.G.; Campoy, C. Impact of Total Parenteral Nutrition on Gut Microbiota in Pediatric Population Suffering Intestinal Disorders. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).