1. Introduction

As rates of diet-related chronic diseases continue to rise—alongside the associated costs to healthcare systems, individual well-being, and environmental sustainability—there is an urgent need for innovative approaches to counter the harmful effects of our current pathogenic food environment. Teaching kitchens—which serve as learning laboratories for essential life skills including nutrition education, hands-on cooking instruction, enhanced physical activity, mindfulness training, and instruction in behavior change strategies—represent a promising solution for training a new generation of informed eaters, educators, and health professionals equipped to drive meaningful behavior change and foster health promotion, also known as salutogenesis.

In January 2022, the Nutrients Editorial Board issued a call for manuscripts for a new Special Issue focusing on the following question: “How can health and wellness promotion strategies which include nutrition education alongside hands-on cooking be organized, evaluated, and optimized for maximal impact?” [1]. This invitation resulted in the acceptance and publication of 36 articles which addressed the role of teaching kitchens and hands-on cooking in relation to a range of nutrition education-related interventions. The studies and review articles published in this Special Issue help answer questions related to the most effective ways to educate individuals, families, communities, and health professionals with respect to nutrition and food choices; provide evidence that these approaches predictably change behaviors and outcomes of interest; and highlight examples as to how these multi-disciplinary educational interventions have the potential to improve human and planetary health.

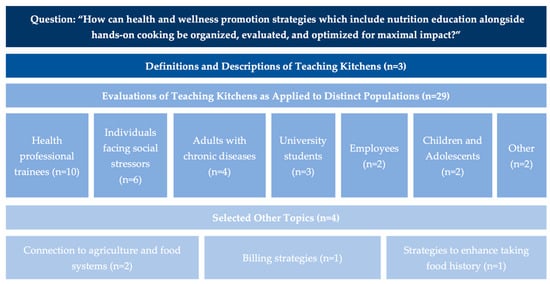

In this commentary, these articles have been grouped into three core categories—definitions and descriptions of teaching kitchens, evaluations of teaching kitchens as applied to distinct populations across multiple settings and selected “other” topics.

This invited commentary provides a summary overview of these 36 publications along with reflections on the following: (i) what has been observed and learned with respect to the development and application of these novel educational approaches across a range of populations and settings; (ii) what remains to be studied to refine and improve these approaches; and (iii) ways in which this emerging literature can inform global research and medical education relating to teaching kitchens, culinary medicine, lifestyle medicine, integrative medicine, the Food is Medicine (FIM) movement, whole-person health research, and the rapidly emerging United States (US)-based “Make America Healthy Again” (MAHA) movement. Importantly, the articles from this Special Issue, alongside the existing body of teaching kitchen literature described herein, confirm the emerging growth of research involving teaching kitchens and hands-on cooking as valuable adjuncts to nutrition education teaching methods and interventions.

This commentary highlights how health practitioners, educators, and policymakers are increasingly mobilizing to identify effective strategies—including the use of teaching kitchens—that enhance the health of individuals, communities, and the planet.

2. Descriptions of Nutrients Special Issue Articles

Between June 2023–June 2024, 36 articles were accepted and published in the Nutrients Special Issue. This Special Issue included 32 research articles, 2 review papers, and 2 “other” articles.

After reviewing all 36 articles, three core categories emerged: definitions and descriptions of teaching kitchens, evaluations of teaching kitchens as applied to distinct populations across multiple settings, and selected “other” topics. Articles about specific populations were subsequently divided into seven sub-categories—health professional trainees, adults with chronic disease, individuals facing social stressors, university students, employees, children, and others. Articles about selected other topics included the connection between teaching kitchens and agriculture and food systems, billing strategies, and strategies to enhance the solicitation of a patient’s food history.

Figure 1 displays the core categories as they relate to the Special Issue prompt question: “How can health and wellness promotion strategies which include nutrition education alongside hands-on cooking be organized, evaluated, and optimized for maximal impact?”. Table 1 lists the articles by categories and sub-categories and includes a summary of the main findings of each article. Further details about each of these articles, including the population studied, sample size, study design, outcome(s) of interest, intervention, and key findings, are described in Supplementary Table S1.

Figure 1.

Articles in the Nutrients Special Issue arranged by core category (N = 36).

Table 1.

Nutrients Special Issue articles arranged by core category *.

All 36 papers add to the literature base demonstrating evidence for and strategies to organize, evaluate, and optimize health and wellness programs for maximal impact, especially through the combination of nutrition education with hands-on cooking. Several of these papers stand out as particularly innovative and have the potential to shape future efforts related to teaching kitchens, culinary medicine, whole-person health, FIM, and other lifestyle-based interventions. The authors describe a subset of these articles in further detail below.

3. Selected Articles

3.1. Perspective: Teaching Kitchens: Conceptual Origins, Applications and Potential for Impact Within Food Is Medicine Research [2]

This paper frames the entirety of the Special Issue, as it grounds the topic of teaching kitchens in terms of their origins, evidence, and structure, as well as opportunities for future research and practice. The paper makes the case that hands-on strategies (i.e., teaching kitchens) that train individuals in nutrition, mindfulness, movement, and behavior change have the potential to improve health outcomes, address social determinants of health, reduce barriers to healthy eating patterns, and slow rising healthcare costs. Teachings from Traditional Chinese Medicine—which tout the superiority of prevention over intervention and the influence of dietary, movement, and thought patterns on overall well-being—can be applied to modern medicine through teaching kitchens. Because teaching kitchens share many synergies and applications to fields such as culinary medicine, integrative medicine, lifestyle medicine, and FIM—and with the growing national attention in these complementary fields—there are countless opportunities for continued research and investment to demonstrate the potential economic, health, and social benefits of teaching kitchens as learning laboratories of the future.

3.2. Characteristics of Current Teaching Kitchens: Findings from Recent Surveys of the Teaching Kitchen Collaborative [3]

This paper describes common characteristics of teaching kitchens from Teaching Kitchen Collaborative members. Teaching kitchen programs are commonly delivered through the healthcare system, universities, and community-based organizations through a variety of modalities, including mobile carts, pop-up kitchens, pod kitchens, built-in-kitchens, and/or virtual settings. Teaching kitchens serve a range of individuals, including patients, practicing health professionals and trainees, employees, children, older adults, low-income individuals, and others, and are typically directed and/or facilitated by physicians, registered dietitians, chefs, and/or administrative directors or managers. Teaching kitchens offer multiple operational functions, with the majority of programs delivering culinary skills training and nutrition education and providing mindfulness training. Multiple funding streams exist to support teaching kitchens, including philanthropy, participant dues, organizational support, insurance, corporate sponsorship, and others, with most programs relying on more than one source. Future research should focus on best practices in program design, opportunities to integrate with the growing FIM movement, sustainable funding mechanisms, and—importantly—ways to better serve teaching kitchen participants.

3.3. “Zoom”ing to the Kitchen: A Novel Approach to Virtual Nutrition Education for Medical Trainees [12]

This paper addresses an important gap in nutrition education delivery by evaluating the effectiveness of a virtually delivered, single-session nutrition class—which included a hands-on teaching kitchen component—on students’ nutrition-related knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. This course was delivered to physician assistant students and suggests that as little as one course may lead to persistent nutrition knowledge increases and confidence in nutrition counseling. This study indicates that even small doses of nutrition education, delivered virtually, can be effective in improving health professional trainees’ nutrition-related knowledge and skills, paving a path to scalability and sustainability.

3.4. Impact of Culinary Medicine Course on Confidence and Competence in Diet and Lifestyle Counseling, Interprofessional Communication, and Health Behaviors and Advocacy [13]

This study addresses three prominent topics in the teaching kitchen literature: the effectiveness of a culinary medicine elective on improving health professional trainees’ confidence and competence in food and nutrition counseling and knowledge, the impact of program delivery setting—in-person versus virtual—on participant outcomes, and differences in counseling confidence for students that enrolled in the elective culinary medicine course versus those that did not. An eight-week (24 h) culinary medicine course significantly improved health professional trainees’ confidence and competence in food and nutrition counseling, interprofessional communication skills, and healthy meal preparation. These findings hold constant whether the course was delivered in-person or online. Finally, this study demonstrated that medical students that participated in this culinary medicine course expressed significantly higher confidence in delivering nutrition and physical activity counseling to patients compared to students that did not take the course.

3.5. Assessing Acceptability: The Role of Understanding Participant, Neighborhood, and Community Contextual Factors in Designing a Community-Tailored Cooking Intervention [20]

This paper points to the importance of incorporating community members’ perspectives when designing effective teaching kitchen programs in order to best meet the needs of the target population. Participants in this study indicated that effective cooking interventions must address the following: (i) barriers to cooking (e.g., transportation, family and caregiving, time, household eating patterns, etc.); (ii) motivators to cooking (e.g., family, health, enjoyment, caregiving, etc.); (iii) applicable strategies (e.g., social support, meal planning, food shopping behaviors, etc.); (iv) neighborhood-based factors (e.g., safety, grocery store access, gentrification, stigma, etc.); and (v) intervention acceptability (e.g., influences to participate, delivery methods, recruitment strategies, etc.). By integrating community-informed insights during the planning phase, teaching kitchen and hands-on cooking programs are more likely to yield meaningful and sustainable outcomes for both researchers and participants.

3.6. Promoting Nutrition and Food Sustainability Knowledge in Apprentice Chefs: An Intervention Study at the School of Italian Culinary Arts—ALMA [26]

Chefs play an important role in individual and societal consumption patterns. While many culinary students have a moderate understanding of nutrition concepts, knowledge about sustainability concepts is lacking. This paper presents findings that an educational intervention which incorporates both nutrition and sustainability topics leads to significant improvements in students’ planetary health knowledge and small, but meaningful improvements in nutrition knowledge, suggesting that a sustainability-focused curriculum could drive improvements in global menus and dining patterns. Enhanced versions of the questionnaire developed for this study may also drive further assessments of culinary trainees’ health and sustainability knowledge and skills in both research and practice.

3.7. University Students as Change Agents for Health and Sustainability: A Pilot Study on the Effects of a Teaching Kitchen-Based Planetary Health Diet Curriculum [27]

In the face of both the global diet-related disease epidemic and climate crisis, this paper introduces an innovative approach to preparing future leaders in food and health. Through a university elective course delivered in a teaching kitchen setting, students from multiple disciplines engaged with planetary health diet concepts integrated into each lecture. Following the course, students showed significant improvements in planetary health diet literacy, suggesting that a hands-on, sustainability-focused nutrition curriculum can effectively influence knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors around healthy, sustainable cooking and eating practices.

3.8. Effect of the Emory Healthy Kitchen Collaborative on Employee Health Habits and Body Weight: A 12-Month Workplace Wellness Trial [29]

Worksite wellness programs have the potential to improve employees’ quality of life and overall health. This paper describes a 12-month teaching kitchen program which incorporated didactic, hands-on, and health coaching strategies to support a cohort of motivated individuals at an academic medical center. A multidisciplinary team led training sessions in culinary arts, mindful eating, yoga, exercise, stress resilience, and ethnobotany. Following the intervention, participants demonstrated improvements in diet quality, confidence in trying novel foods, mindful eating habits, and physical activity. This study demonstrates that engaging a multidisciplinary team as part of a workplace wellness strategy may lead to employees’ self-reported health behaviors.

3.9. The Role of Agricultural Systems in Teaching Kitchens: An Integrative Review and Thoughts for the Future [35]

This paper explores the intersections between agriculture, healthcare, culinary arts, nutrition science, and public health and highlights case studies where these often-siloed disciplines have come together to advance both human and planetary health. Increasingly, chefs, physicians, dietitians, and farmers are finding opportunities to collaborate to educate patients, communities, students, and medical trainees about the interconnectedness of food production, distribution, preparation, and consumption and the physiological and ecological consequences of each of these processes. Showcasing these linkages through teaching kitchen programs can elevate the roles of farmers and chefs within the growing Food is Medicine and culinary medicine movements, reinforcing their contributions to a more integrated and sustainable approach to health.

3.10. Culinary Medicine eConsults Pair Nutrition and Medicine: A Feasibility Pilot [36]

Enhancing referral pathways within healthcare teams can significantly improve patient access to essential services, including nutrition counseling and support. This paper presents an innovative pilot clinical workflow in which primary care physicians referred patients for a culinary medicine eConsult, delivered collaboratively by a physician-dietitian team. Most of these eConsults were successfully billed as reimbursable services, demonstrating the potential for a viable, scalable, and sustainable payment model—one that both compensates healthcare providers and expands patient access to nutrition counseling. Following the publication within the Nutrients Special Issue, the complete study paper illustrates the impact of this innovative culinary medicine service line which offers personalized food-based support while leveraging community kitchens as clinical sites through strategic partnerships [38]. The program’s early successes highlight its potential for broader adoption and phased growth of food as medicine initiatives.

3.11. Standard Patient History Can Be Augmented Using Ethnographic Foodlife Questions [37]

Typical food intake questionnaires are often perceived as clinical, impersonal, and disconnected from the lived experiences of patients. Yet, food is deeply tied to culture, emotion, and identity—far more than just its nutritional components. To enhance patient engagement, this paper proposes an expanded food history framework grounded in ethnographic methods, designed to explore individuals’ relationships with food and their underlying motivations. By enriching food history intake in this way, healthcare providers can foster deeper trust and open dialogue with patients, potentially leading to more meaningful and lasting improvements in health behaviors.

4. Discussion

These 36 articles add to the growing body of evidence demonstrating the value and applicability of teaching kitchens and other hands-on cooking experiential interventions to a wide range of populations across many settings. Outside of the publications from this Nutrients Special Issue, several other notable publications exist describing the role of teaching kitchens and hands-on cooking strategies in other settings and for other populations. These publications are described in Supplementary Table S2. While these and the articles in Table 1 offer a significant description of the state of the evidence on teaching kitchens, this paper is not a meta-analysis of the entirety of the teaching kitchen literature base. Rather, this paper represents a synthesis of the contents of the Nutrients Special Issue, plus the co-authors’ shared expertise and opinion regarding other publications of interest.

Together, these articles suggest that teaching kitchens and other multi-disciplinary educational interventions which include hands-on cooking may positively impact the populations displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Populations for which teaching kitchens may offer benefits, based on the existing literature.

It is the applicability of teaching kitchen-related interventions to so many populations that suggests that these emerging educational interventions warrant further refinement, replication, and formal evaluation.

The Nutrients Special Issue, alongside the additional articles cited above, provides an overview of more than ten years of collective work related to the scientific evaluation of teaching kitchens and culinary medicine and their potential for impact on individual and public health. Given the available evidence from this body of literature, several questions arise which can guide future research.

5. Future Research and Educational Opportunities

Further studies should investigate gaps in the evidence, such as the correct ‘dose’ and duration of a teaching kitchen intervention; minimal educational components of a teaching kitchen curriculum which will result in predictable behavior change; predictors of health-enhancing behavior change based on data from additional prospective teaching kitchen-related educational interventions; patient populations that should be prioritized; the integration of teaching kitchen programs with GLP-1 therapies to support the transition on and off of these intensive and expensive medications; cost-effectiveness analyses for specific patient populations and payer coverage by line of business; strategies whereby teaching kitchen instructors from a range of disciplines (e.g., dietitians, physicians, nurses, chefs, exercise and mindfulness instructors, behavior change experts, etc.) are trained, evaluated and “certified”; and the minimum necessary level of training required for medical students, physician trainees, and practicing clinicians to recommend and refer patients to teaching kitchen or other lifestyle medicine-based therapies.

In addition to these research gaps, further attention should be directed to several emerging themes and logistical considerations related to teaching kitchens and culinary medicine programs. First, comparative analyses of in-person versus virtual teaching kitchen models are needed to determine which components are best delivered in each format and how accessibility and engagement differ across populations and platforms. Second, there is an urgent need for cost modeling studies to determine the minimum financial investment required to achieve meaningful outcomes—whether in clinical, educational, or community-based settings. Third, future studies of FIM interventions should collect data on cooking confidence, skills, and frequency, as these may positively correlate (or potentially act as a confounding variable) with greater positive health outcomes (i.e., patients that receive culinary coaching or support in addition to produce prescriptions or medically tailored groceries may demonstrate greater health benefits compared to those who do not). Fourth, the development of robust and validated theoretical frameworks to explain the mechanisms through which teaching kitchen curricula impact behavior, clinical outcomes, and systems-level change remains a significant unmet need. Fifth, future research should explore predictors of successful intervention response, including sociodemographic factors, health status, baseline self-efficacy, and readiness for change. Lastly, well-designed longitudinal studies are required to determine the optimal follow-up duration for capturing both short- and long-term impacts of multidisciplinary teaching kitchen interventions. These should be conducted across diverse settings and populations to build a more generalizable evidence base and to guide the strategic implementation of these programs at scale.

Additionally, as evidence increases that teaching kitchens have the potential to impact behavior change, clinical outcomes, and the cost of medical care, it will become essential to establish criteria whereby teaching kitchen facilities, instructors, and relevant teaching kitchen educational ensembles can be credentialed, as third-party payers will likely require such standardization and accreditation.

The imperative to incorporate teaching kitchens into the medical curriculum can also be viewed as a catalyst for improving learning and work environments and can contribute to enhanced well-being of health professionals, faculty, and trainees. As the concept of Human Flourishing has been expanded to medical education to create a more conducive environment for learning and operationalized further to provide trainees with key skills, teaching kitchens can play a vital role by providing a unique opportunity to ‘Nourish to Flourish’ [39,40,41]. The comprehensive approach to flourishing in medical school—and in life—involves aligning key domains of one’s life, such as meaning, purpose, characters, values, and relationships; increasing physical activity; adopting mindfulness practices; and choosing better nourishment through an understanding of food and food choices; all of which can be fostered together through the use of teaching kitchens as classrooms.

This line of ongoing inquiry is additionally supported by the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH’s) Office of Nutrition Research (ONR). ONR is currently actively involved with myriad culinary medicine and teaching kitchen activities, both with the extramural research community as well as on the NIH campus itself. The ONR Teaching Kitchen Program—which currently serves The Children’s Inn at NIH which is planned to expand to serve the NIH Clinical Center and campus as a whole is highlighted in the Office’s current strategic plan [42,43]. Culinary medicine and teaching kitchen activities are also rooted within an approved NIH concept for comprehensive FIM Networks or Centers of Excellence [44]. These topics also align well with the recent HHS Press Release and Editorial calling for enhanced nutrition education requirements for physicians [45,46,47].

6. Conclusions

This is the first paper to our knowledge that includes many—if not most—of the relevant published articles relating to teaching kitchens, as well as other strategies that include hands-on cooking, and their potential to enhance nutrition education, clinical care, and management of selected patient populations. There is increasing evidence that these approaches can inform and, potentially, be incorporated into future educational, research, clinical, and policy recommendations.

We must consider and think of teaching kitchens in the context of current US and global trends relating to culinary medicine, lifestyle medicine, whole-person health, FIM, and the US-based MAHA movement. As healthcare leaders and practitioners, health plans, community organizers, policymakers, and researchers continue to invest in and investigate the effectiveness of these programs, it will be critical to integrate experts in teaching kitchen design, implementation, and evaluation to optimize health-promoting strategies for individuals, communities, and health systems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nu17233638/s1, Table S1: Descriptions of 36 Nutrients Articles. Table S2: Selected Additional Articles from Other Journals Evaluating the Impact of Teaching Kitchens and Related Interventions [48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M.E. and A.C.; writing—original draft preparation, D.M.E., A.C., L.S.P. and J.M.; writing—review and editing, D.M.E., A.C., L.S.P., J.M., A.H. and A.A.B.; visualization, A.C.; supervision, D.M.E.; project administration, A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

D.M.E. reported receiving personal fees from Teaching Kitchen Collaborative, Northwell Health, CancerScan Inc., Infinitus Inc., and Nissin Inc and honoraria from Barilla Inc outside the submitted work. A.C. reported receiving personal fees from Teaching Kitchen Collaborative outside the submitted work. L.S.P. reports funding from NIH (K01HL169414; P30 DK 040561). No other disclosures were reported.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FIM | Food is Medicine |

| US | United States |

| MAHA | Make America Healthy Again |

| GLP | Glucagon-like peptide |

| NIH | National Institutes of Health |

| ONR | Office of Nutrition Research |

References

- Eisenberg, D.M. Special Issue: How Can Health and Wellness Promotion Strategies Which Include Nutrition Education alongside Hands-On Cooking Be Organized, Evaluated, and Optimized for Maximal Impact. Nutrients 2023. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/nutrients/special_issues/F62DAN81H6 (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Eisenberg, D.M.; Pacheco, L.S.; McClure, A.C.; McWhorter, J.W.; Janisch, K.; Massa, J. Perspective: Teaching Kitchens: Conceptual Origins, Applications and Potential for Impact within Food Is Medicine Research. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badaracco, C.; Thomas, O.W.; Massa, J.; Bartlett, R.; Eisenberg, D.M. Characteristics of Current Teaching Kitchens: Findings from Recent Surveys of the Teaching Kitchen Collaborative. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croxford, S.; Stirling, E.; MacLaren, J.; McWhorter, J.W.; Frederick, L.; Thomas, O.W. Culinary Medicine or Culinary Nutrition? Defining Terms for Use in Education and Practice. Nutrients 2024, 16, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, K.L.; Kennedy, J.; Kim, D.; Kalra, A.; Parekh, N.K. Development of a Culinary Medicine Curriculum to Support Nutrition Knowledge for Gastroenterology Fellows and Faculty. Nutrients 2024, 16, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thircuir, S.; Chen, N.N.; Madsen, K.A. Addressing the Gap of Nutrition in Medical Education: Experiences and Expectations of Medical Students and Residents in France and the United States. Nutrients 2023, 15, 5054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, K.; Thomas, O.W.; Sweeney, T.; Ryan, T.J.; Kytomaa, S.; Zhao, M.; Zhong, W.; Long, M.; Rajendran, I.; Sarfaty, S.; et al. Eat to Treat: The Methods and Assessments of a Culinary Medicine Seminar for Future Physicians and Practicing Clinicians. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böttcher, S.; Schonebeck, L.J.; Drösch, L.; Plogmann, A.M.; Leineweber, C.G.; Puderbach, S.; Buhre, C.; Schmöcker, C.; Neumann, U.; Ellrott, T. Comparison of Effectiveness regarding a Culinary Medicine Elective for Medical Students in Germany Delivered Virtually versus In-Person. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ring, M.; Ai, D.; Maker-Clark, G.; Sarazen, R. Cooking up Change: DEIB Principles as Key Ingredients in Nutrition and Culinary Medicine Education. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thang, C.K.; Guerrero, A.D.; Garell, C.L.; Leader, J.K.; Lee, E.; Ziehl, K.; Carpenter, C.L.; Boyce, S.; Slusser, W. Impact of a Teaching Kitchen Curriculum for Health Professional Trainees in Nutrition Knowledge, Confidence, and Skills to Advance Obesity Prevention and Management in Clinical Practice. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maker-Clark, G.; McHugh, A.; Shireman, H.; Hernandez, V.; Prasad, M.; Xie, T.; Parkhideh, A.; Lockwood, C.; Oyola, S. Empowering Future Physicians and Communities on Chicago’s South Side through a 3-Arm Culinary Medicine Program. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charles, J.A.; Wood, N.I.; Neary, S.; Moreno, J.O.; Scierka, L.; Brink, B.; Zhao, X.; Gielissen, K.A. “Zoom”ing to the Kitchen: A Novel Approach to Virtual Nutrition Education for Medical Trainees. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, B.R.; Beals, K.A.; Burns, R.D.; Chow, C.J.; Locke, A.B.; Petzold, M.P.; Dvorak, T.E. Impact of Culinary Medicine Course on Confidence and Competence in Diet and Lifestyle Counseling, Interprofessional Communication, and Health Behaviors and Advocacy. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafto, K.; Vandenburgh, N.; Wang, Q.; Breen, J. Experiential Culinary, Nutrition and Food Systems Education Improves Knowledge and Confidence in Future Health Professionals. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domper, J.; Gayoso, L.; Goni, L.; Perezábad, L.; Razquin, C.; de la O, V.; Etxeberria, U.; Ruiz-Canela, M. An Intensive Culinary Intervention Programme to Promote Healthy Ageing: The SUKALMENA-InAge Feasibility Pilot Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Riccardi, D.; Pflanzer, S.; Redwine, L.S.; Gray, H.L.; Carson, T.L.; McDowell, M.; Thompson, Z.; Hubbard, J.J.; Pabbathi, S. Survivors Overcoming and Achieving Resiliency (SOAR): Mindful Eating Practice for Breast Cancer Survivors in a Virtual Teaching Kitchen. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanumihardjo, J.P.; Davis, H.; Zhu, M.; On, H.; Guillory, K.K.; Christensen, J. Enhancing Chronic-Disease Education through Integrated Medical and Social Care: Exploring the Beneficial Role of a Community Teaching Kitchen in Oregon. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, M.F.; Chen, P.M.; Smith-Morris, C.; Albin, J.; Siler, M.D.; Lopez, M.A.; Pruitt, S.L.; Merrill, V.C.; Bowen, M.E. Redesigning Recruitment and Engagement Strategies for Virtual Culinary Medicine and Medical Nutrition Interventions in a Randomized Trial of Patients with Uncontrolled Type 2 Diabetes. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French, M.L.; Christensen, J.T.; Estabrooks, P.A.; Hernandez, A.M.; Metos, J.M.; Marcus, R.L.; Thorpe, A.; Dvorak, T.E.; Jordan, K.C. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of a Bilingual Nutrition Education Program in Partnership with a Mobile Health Unit. Nutrients 2024, 16, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, N.; Tuason, R.; Middleton, K.R.; Ude, A.; Tataw-Ayuketah, G.; Flynn, S.; Kazmi, N.; Baginski, A.; Mitchell, V.; Powell-Wiley, T.M.; et al. Assessing Acceptability: The Role of Understanding Participant, Neighborhood, and Community Contextual Factors in Designing a Community-Tailored Cooking Intervention. Nutrients 2024, 16, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetherill, M.S.; Caywood, L.T.; Hollman, N.; Carter, V.P.; Gentges, J.; Sims, A.; Henderson, C.V. Food Is Medicine for Individuals Affected by Homelessness: Findings from a Participatory Soup Kitchen Menu Redesign. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, D.R.; Kimmel, R.; Shodahl, S.; Vargas, J.H. Examination of an Online Cooking Education Program to Improve Shopping Skills, Attitudes toward Cooking, and Cooking Confidence among WIC Participants. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ylitalo, K.R.; Janda, K.M.; Clavon, R.; Raleigh-Yearby, S.; Kaliszewski, C.; Rumminger, J.; Hess, B.; Walter, K.; Cox, W. Cross-Sector Partnerships for Improved Cooking Skills, Dietary Behaviors, and Belonging: Findings from a Produce Prescription and Cooking Education Pilot Program at a Federally Qualified Health Center. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temelkova, S.; Lofton, S.; Lo, E.; Wise, J.; McDonald, E.K. Nourishing Conversations: Using Motivational Interviewing in a Community Teaching Kitchen to Promote Healthy Eating via a Food as Medicine Intervention. Nutrients 2024, 16, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French, C.D.; Gomez-Lara, A.; Hee, A.; Shankar, A.; Song, N.; Campos, M.; McCoin, M.; Matias, S.L. Impact of a Food Skills Course with a Teaching Kitchen on Dietary and Cooking Self-Efficacy and Behaviors among College Students. Nutrients 2024, 16, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchini, C.; Biasini, B.; Giopp, F.; Rosi, A.; Scazzina, F. Promoting Nutrition and Food Sustainability Knowledge in Apprentice Chefs: An Intervention Study at The School of Italian Culinary Arts—ALMA. Nutrients 2024, 16, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenau, N.; Neumann, U.; Hamblett, S.; Ellrott, T. University Students as Change Agents for Health and Sustainability: A Pilot Study on the Effects of a Teaching Kitchen-Based Planetary Health Diet Curriculum. Nutrients 2024, 16, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daker, R.; Challamel, G.; Hanson, C.; Upritchard, J. Cultivating Healthier Habits: The Impact of Workplace Teaching Kitchens on Employee Food Literacy. Nutrients 2024, 16, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergquist, S.H.; Wang, D.; Fall, R.; Bonnet, J.P.; Morgan, K.R.; Munroe, D.; Moore, M.A. Effect of the Emory Healthy Kitchen Collaborative on Employee Health Habits and Body Weight: A 12-Month Workplace Wellness Trial. Nutrients 2024, 16, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marconi, S.; Covolo, L.; Marullo, M.; Zanini, B.; Viola, G.C.V.; Gelatti, U.; Maroldi, R.; Latronico, N.; Castellano, M. Cooking Skills, Eating Habits and Nutrition Knowledge among Italian Adolescents during COVID-19 Pandemic: Sub-Analysis from the Online Survey COALESCENT (Change amOng ItAlian adoLESCENTs). Nutrients 2023, 15, 4143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, N.; Nguyen, K.; Kalami, V.; Qin, F.; Mathur, M.B.; Blankenburg, R.; Yeh, A.M. A Specific Carbohydrate Diet Virtual Teaching Kitchen Curriculum Promotes Knowledge and Confidence in Caregivers of Pediatric Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.G.; Kundra, A.; Ho, P.; Bissell, E.; Apekey, T. Feasibility of a Community Healthy Eating and Cooking Intervention Featuring Traditional African Caribbean Foods from Participant and Staff Perspectives. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polak, R.; Finkelstein, A.; Budd, M.A.; Gray, B.E.; Robinson, H.; Silver, J.K.; Faries, M.D.; Tirosh, A. Expectations from a Home Cooking Program: Qualitative Analyses of Perceptions from Participants in “Action” and “Contemplation” Stages of Change, before Entering a Bi-Center Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fals, A.M.; Brennan, A.M. Teaching Kitchens and Culinary Gardens as Integral Components of Healthcare Facilities Providing Whole Person Care: A Commentary. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, A.; Pethan, J.; Evans, J. The Role of Agricultural Systems in Teaching Kitchens: An Integrative Review and Thoughts for the Future. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albin, J.L.; Siler, M.; Kitzman, H. Culinary Medicine eConsults Pair Nutrition and Medicine: A Feasibility Pilot. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.J.; McWhorter, J.W.; Bryant, G.; Zisser, H.; Eisenberg, D.M. Standard Patient History Can Be Augmented Using Ethnographic Foodlife Questions. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albin, J.; Wong, W.; Siler, M.; Bowen, M.E.; Kitzman, H. A Novel Culinary Medicine Service Line: Practical Strategy for Food as Medicine. NEJM Catal. Innov. Care Deliv. 2025, 6, CAT-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderweele, T.J. On the promotion of human flourishing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 8148–8156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurana, C.A.; Fritz, J.D.; Witten, A.A.; Williams, S.E.; Ellefson, K.A. Advancing flourishing as the north star of medical education: A call for personal and professional development as key to becoming physicians. Med. Teach. 2024, 46, 1539–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haramati, A. Importance of Mind-Body Medicine and Human Flourishing in the Training of Physicians. Marshall J. Med. 2024, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teaching Kitchen Preps Families for a Feast—The Children’s Inn at NIH. Available online: https://childrensinn.org/stories/teaching-kitchen/ (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- National Institutes of Health. Office of Nutrition Research Strategic Plan, Fiscal Years 2026–2030. Available online: https://dpcpsi.nih.gov/onr/onr-strategic-plan (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Lynch, C.J. A Concept for Comprehensive Food is Medicine Networks or Centers of Excellence. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 118, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HHS Demands Nutrition Education Reforms in Medical Schools | Nutrition | JAMA | JAMA Network. Available online: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/2839214 (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Secretaries Kennedy, McMahon Demand Comprehensive Nutrition Education Reforms|HHS.gov. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 27 August 2025. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/press-room/hhs-education-nutrition-medical-training-reforms.html (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Kennedy, R.F., Jr. RFK Jr.: An Apple a Day Is a Good Prescription. Wall Street Journal. 27 August 2025. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/opinion/an-apple-a-day-is-a-good-prescription-kennedy-hhs-diet-health-73227a67 (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Pang, B.; Memel, Z.; Diamant, C.; Clarke, E.; Chou, S.; Gregory, H. Culinary medicine and community partnership: Hands-on culinary skills training to empower medical students to provide patient-centered nutrition education. Med. Educ. Online 2019, 24, 1630238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magallanes, E.; Sen, A.; Siler, M.; Albin, J. Nutrition from the kitchen: Culinary medicine impacts students’ counseling confidence. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, N.I.; Fussell, M.; Benghiat, E.; Silver, L.; Goldstein, M.; Ralph, A.; Mastroianni, L.; Spatz, E.; Small, D.; Fisher, R.; et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Culinary Medicine Intervention in a Virtual Teaching Kitchen for Primary Care Residents. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2025, 40, 2668–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, A.C.; Latoff, A.; Dyer, A.; Albin, J.L.; Artz, K.; Babcock, A.; Cimino, F.; Daghigh, F.; Dollinger, B.; Fiellin, M.; et al. Virtual teaching kitchen classes and cardiovascular disease prevention counselling among medical trainees. BMJ Nutr. Prev. Health. 2023, 6, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricanati, E.H.; Golubić, M.; Yang, D.; Saager, L.; Mascha, E.J.; Roizen, M.F. Mitigating preventable chronic disease: Progress report of the Cleveland Clinic’s Lifestyle 180 program. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 8, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, K.; Hajna, S.; Joseph, L.; Da Costa, D.; Christopoulos, S.; Gougeon, R. Effects of meal preparation training on body weight, glycemia, and blood pressure: Results of a phase 2 trial in type 2 diabetes. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.V.; McWhorter, J.W.; Chow, J.; Danho, M.P.; Weston, S.R.; Chavez, F.; Moore, L.S.; Almohamad, M.; Gonzalez, J.; Liew, E.; et al. Impact of a Virtual Culinary Medicine Curriculum on Biometric Outcomes, Dietary Habits, and Related Psychosocial Factors among Patients with Diabetes Participating in a Food Prescription Program. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlueter, R.; Calhoun, B.; Harned, E.; Gore, S. A VA Health Care Innovation: Healthier Kidneys Through Your Kitchen—Earlier Nutrition Intervention for Chronic Kidney Disease. J. Ren. Nutr. 2021, 31, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritlove, C.; Capone, G.; Kita, H.; Gladman, S.; Maganti, M.; Jones, J.M. Cooking for Vitality: Pilot Study of an Innovative Culinary Nutrition Intervention for Cancer-Related Fatigue in Cancer Survivors. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenek, A.M.; Aggarwal, M.; Chung, S.T.; Courville, A.B.; Farmer, N.; Guo, J.; Mathews, A. Influence of a Virtual Plant-Based Culinary Medicine Intervention on Mood, Stress, and Quality of Life Among Patients at Risk for Cardiovascular Disease. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooler, J.A.; Morgan, R.E.; Wong, K.; Wilkin, M.K.; Blitstein, J.L. Cooking Matters for Adults Improves Food Resource Management Skills and Self-confidence Among Low-Income Participants. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2017, 49, 545–553.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, D.M.; Righter, A.C.; Matthews, B.; Zhang, W.; Willett, W.C.; Massa, J. Feasibility Pilot Study of a Teaching Kitchen and Self-Care Curriculum in a Workplace Setting. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2017, 13, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Culinary-Based Intensive Lifestyle Program for Patients with Obesity: The Teaching Kitchen Collaborative Curriculum (TKCC) Pilot Study—PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40507123/ (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Novotny, D.; Urich, S.M.; Roberts, H.L. Effectiveness of a Teaching Kitchen Intervention on Dietary Intake, Cooking Self-Efficacy, and Psychosocial Health. Am. J. Health Educ. 2023, 54, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.; Wang, D.; Berquist, S.; Bonnet, J.; Rastorguieva, K. Dietary, Cooking, and Eating Pattern Outcomes from the Emory Healthy Kitchen Collaborative. Ann. Fam. Med. 2023, 21 (Suppl. S1), 3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.A.; Cousineau, B.A.; Rastorguieva, K.; Bonnet, J.P.; Bergquist, S.H. A Teaching Kitchen Program Improves Employee Micronutrient and Healthy Dietary Consumption. Nutr. Metab. Insights 2023, 16, 11786388231159192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razavi, A.C.; Sapin, A.; Monlezun, D.J.; McCormack, I.G.; Latoff, A.; Pedroza, K.; McCullough, C.; Sarris, L.; Schlag, E.; Dyer, A.; et al. Effect of culinary education curriculum on Mediterranean diet adherence and food cost savings in families: A randomised controlled trial. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 2297–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galyean, S.; Alcorn, M.; Chavez, J.; Niraula, S.R.; Childress, A. The effect of culinary medicine to enhance protein intake on muscle quality in older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2025, 37, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).