Abstract

The olive tree (Olea europaea) and olive oil hold significant cultural and historical importance in Europe. The health benefits associated with olive oil consumption have been well documented. This paper explores the mechanisms of the anti-cancer effects of olive oil and olive leaf, focusing on their key bioactive compounds, namely oleocanthal, oleacein, and oleuropein. The chemopreventive potential of oleocanthal, oleacein, and oleuropein is comprehensively examined through this systematic review. We conducted a systematic literature search to identify eligible articles from Scopus, PubMed, and Web of Science databases published up to 10 October 2023. Among 4037 identified articles, there were 88 eligible articles describing mechanisms of chemopreventive effects of oleocanthal, oleacein, and oleuropein. These compounds have the ability to inhibit cell proliferation, induce cell death (apoptosis, autophagy, and necrosis), inhibit angiogenesis, suppress tumor metastasis, and modulate cancer-associated signalling pathways. Additionally, oleocanthal and oleuropein were also reported to disrupt redox hemostasis. This review provides insights into the chemopreventive mechanisms of O. europaea-derived secoiridoids, shedding light on their role in chemoprevention. The bioactivities summarized in the paper support the epidemiological evidence demonstrating a negative correlation between olive oil consumption and cancer risk. Furthermore, the mapped and summarized secondary signalling pathways may provide information to elucidate new synergies with other chemopreventive agents to complement chemotherapies and develop novel nutrition-based anti-cancer approaches.

Keywords:

olive oil; olive tree; Olea europaea; oleocanthal; oleuropein; oleacein; chemoprevention; cancer 1. Introduction

1.1. Global Burden of Cancer

With 9.7 million cases of cancer-related fatalities worldwide in 2022, it is the second most common cause of death overall after cardiovascular diseases [1]. Between 2020 and 2050, the worldwide economic burden of cancer is estimated at USD 25.2 trillion (using constant 2017 prices). This constitutes 0.55% of the global gross domestic product [2]. In the year 2019, it was estimated that 250 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) were due to cancer, which manifests a 16.0% increase since 2010 [3].

Novel chemopreventive techniques are therefore necessary to enhance anti-carcinogenic therapies as well as review the known mechanism to combine beneficial compounds to utilize their synergies as food supplements or functional foods. Here, we update the review of R. Fabiani focusing on both in vivo and in vitro effects of the secoiridoid content of olive oil such as oleocanthal, oleacein, and oleuropein [4]. Also, we complement here in our systematic review the narrative review of Emma RM. et al. about the preclinical effects of the most relevant secoiridoids [5].

1.2. The History and Compounds of Olive Oil

The olive tree (Olea europaea, Oleaceae) and the olive oil produced from its fruit are an integral part of European culture. Olive trees have been growing for many seasons and the oil extracted from the fruit has been used since the Neolithic age for various purposes, mainly as food [6]. The beneficial fatty acid and water-soluble components of olive oil have long been known [7]. The Seven Countries Study, begun in the 1950s, showed a negative correlation between all-cause mortality, and olive oil consumption, which was attributed to the high levels of monounsaturated fatty acids in olive oil. Speculatively, the effects were largely attributed to the main fatty acid component, oleic acid [8]. However, nowadays, a high number of health-promoting components are known in olive oil. The extra virgin olive oil is the most abundant in such molecules as triglycerides (97–99%) as well as minor compounds (1–3%). The fatty acid components of olive oil triglycerides comprise monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA, 65–83%), especially oleic acid, and in smaller quantity polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), for example linoleic acid. There are also phenolic compounds such as phenolic alcohols, tyrosol (p-hydroxyphenylethanol; p-HPEA) and hydroxytyrosol (3,4-dihydroxyphenylethanol; 3,4-DHPEA), together with their secoiridoid derivatives p-HPEA-EA (ligstroside aglycone), 3,4-DHPEA-EA (oleuropein aglycone), 3,4-DHPEA-EDA (oleacein), and p-HPEA-EDA (oleocanthal). Furthermore, tocopherols and other compounds such as hydrocarbons (for example squalene) and provitamin A compounds are worthy of mentioning [5,9].

1.3. Epidemiological Data about the Anti-Cancer Effects of Olive Oil Consumption

A study showed that olive oil consumption is associated with a reduced risk of lung cancer (OR: 0.65; p < 0.05; 95% CI: 0.42–0.99) [10]. Pelucchi et al. conducted a meta-analysis that found a significantly lower risk of breast cancer in a group who consumed a diet rich in olive oil (highest quartiles of the examined population with daily > 28.05 g intake) compared to persons with the lowest olive oil consumption (lowest quartiles with daily < 9.35 g intake) (pooled RR 0.62; 95% CI 0.44–0.88) [11]. Additionally, a case–control study demonstrated a protective effect against laryngeal cancer in persons who consumed higher amounts of olive oil (highest quartile) compared to those who consumed less (lowest quartile) (OR: 0.4; p = 0.01; 95% CI: 0.3–0.7) [12]. According to the meta-analysis of Markellos et al., the high quantity of olive oil consumption compared to the lowest quantity was associated with a 31% lower likelihood (pooled RR = 0.69) of cancer (95% CI: 0.62–0.77) [13]. Lastly, a dose-dependent reverse relationship was found between olive oil consumption and the risk of bladder cancer (lowest tertile compared to the highest tertile associated with a lower risk) (OR: 0.47, p-trend = 0.002; 95% CI: 0.28–0.78) [14].

1.4. The Relevance of Secoiridoids

Subsequent research has shown that polyunsaturated fatty acids, especially omega-3 fatty acids, play a greater role in health maintenance than monounsaturated fatty acids. These fatty acids are metabolized in the body into various prostanoids (e.g., alpha-linolenic acid to prostacyclin), which play an important role in cardiovascular prevention through their anti-inflammatory and antithrombotic effects. However, oils rich in omega-3 fatty acids appear to be less relevant for prevention. Although rapeseed oil, walnut oil, and soybean oil are significantly higher in omega-3 fatty acids than olive oil [15], their cardiovascular preventive effects are less well suggested. Other oils with a high oleic acid content similar to that of olive oil (peanuts, avocados) [15] have not been found to have similar effects to olive oil. Of course, this may be partly explained by the fact that, unlike olive oil, these oils are not consumed regularly by large populations, which makes epidemiological observations difficult, but the preclinical results with olive oil are also more favorable than with other oils. In animal experiments, feeding with olive oil resulted in decreased platelet hyperactivity and subendothelial thrombogenicity [15]. In a clinical trial, it was observed that, unlike olive oil, rapeseed and sunflower oils did not have an antithrombotic effect [16]. This suggests that other components, in addition to the fatty acids, are involved in the beneficial effects of olive oil. This hypothesis is further reinforced by the fact that no similar advantageous effects have been described for non-extra virgin olive oils with the same fatty acid composition as this extra virgin olive oil. The mentioned minor components in extra virgin olive oils are absent in other olive oils as a result of refining processes [17].

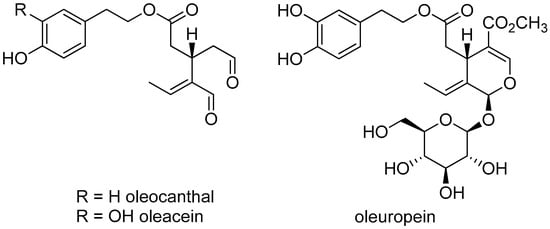

A breakthrough in understanding the mechanism of action of olive oil came with the discovery of oleocanthal (Figure 1). This secoiridoid was described in 1993 [18], but its biological importance was only later recognized. The anti-inflammatory activity of oleocanthal was documented in 2005, and this bioactivity plays an important role in antithrombotic and cardiovascular preventive effects. Interestingly, oleocanthal was identified in a study looking for a substance with a flavor similar to ibuprofen in olive oil [19].

Figure 1.

The major secoiridoids of O. europaea.

The second most quantitatively important secoiridoid in olive oil, oleacein, was identified in a bioassay-guided study to identify compounds that inhibit the angiotensin convertase enzyme [20]. Although oleocanthal is found in concentrations of approximately 300 mg/kg, oleacein is found in approximately a third of this amount in extra virgin olive oil. In non-extra virgin olive oil, the two compounds are found at an order of magnitude lower concentration [21].

Oleacein was first discovered not from olive oil but from olive leaf extract [20]. The main secoiridoid of olive leaves, oleuropein, was discovered several decades earlier [22]. Secoiridoids may not only be related to the beneficial effects of olive oil shown in epidemiological studies but may also explain the effects of olive leaf in traditional medicine. The leaves of the olive tree have been widely used in folk medicine in the Mediterranean region to reduce fever of different origin, including malaria. Among its other medicinal uses, the leaf is thought to have an antihypertensive and diuretic effect [21]. According to the monograph of the European Medicines Agency, olive leaf can be marketed as traditional herbal medicinal products to promote renal elimination of water in mild cases of water retention [23].

Oleocanthal, oleacein, and oleuropein are secoiridoids characteristic of O. europea. In addition to their anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, these compounds may also have bioactivities that may play a role in the beneficial effects observed in cell cultures, animal experiments, epidemiological or clinical studies of olive oil or olive leaf [24,25].

The aim of our work is to systematically review and summarize the literature on the mechanisms of chemopreventive effects of the main secoiridoids of O. euopaea, namely oleocanthal, oleacein and oleuropein.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

We conducted a systematic literature search to identify eligible scientific articles published between established articles up to 10 October 2023. This scoping review was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Review (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines [14]. All selected studies were imported into the automated citation checking service Zotero (https://www.zotero.org/, accessed on 10 October 2023) to identify and eliminate duplicate records.

2.2. Search Strategy

The systematic literature search was performed using Scopus, PubMed, and Web of Science databases on October 10th, 2023. The search key comprised the keywords “oleocanthal” OR “OLE6 protein” OR “Olea europaea” OR “OLE9 protein” OR “Olea europaea” OR “OLE3 protein” OR “Olea europaea” OR “olive leaf extract” OR “Olive Oil” OR “Oleocanthal” OR “Olea europaea” OR “Olive leaf extract” OR “Olive polyphenol” OR “Olive” OR “Olive oil” OR “Extra virgin olive” OR “Olive compound” OR “Olive extract” OR “Olive oil phenolic”) OR (“oleuropein” OR “10-hydroxyoleuropein” OR “Ligustrum” OR “Oleuropein” OR “Olea europaea” OR “Olive leaf extract” OR “Olive polyphenol” OR “Olive” OR “Olive oil” OR “Extra virgin olive” OR “Olive compound” OR “Olive extract” OR “Olive oil phenolic” OR “10-hydroxyoleuropein” OR “Ligustrum”) AND (“Chemoprevention” OR “Chemoprevent*” OR “Anticancer” OR “Antitumor” OR “Tumor prevent*” OR “Cancer chemoprevent*”. The detailed search strategy for each database is provided in Supplementary Material (Supplementary Information S1).

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

This review employed specific inclusion and exclusion criteria tailored to the scope of this study. Inclusion criteria encompassed in silico, in vitro, in vivo, or clinical studies involving the main secoiridoids of O. europaea, including oleocanthal, oleacein, and oleuropein focusing on their effects and mechanisms of chemoprevention, without language restriction. Exclusion criteria comprised studies reporting only cytotoxic effects against certain cell lines, investigations involving complex mixtures, such as those from olive mill wastewater or oil production waste products, studies focusing on major metabolite of oleuropein such as hydroxytyrosol, and articles such as reviews, book reviews, book chapters, conference abstracts, notes, and communication articles.

2.4. Study Selection

Two independent reviewers (IYK, MAB) screened the titles and abstracts of all articles for eligibility employing the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria using Rayyan AI software [15]. The data extraction screening included information on intervention details, study design, tissue/cell types, mechanism of action, and outcomes. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion and consensus. The full texts of potentially eligible papers were then reviewed by the same two reviewers (IYK, MAB) using the same criteria. A third reviewer (DC) was involved to solve any disagreements during the screening process. Two reviewers (IYK, HH) separately extracted the data then cross-checked by MAB and DC. Using a standardized template in Microsoft Office Excel 2019, the synthesis comprised a thematic analysis of the reported findings and a descriptive overview of the study’s characteristics (see Table 1).

Table 1.

The chemopreventive effects of oleocanthal, oleuropein, and oleacein on targeted cancer cells (in vitro, in silico, and in vivo studies).

3. Results

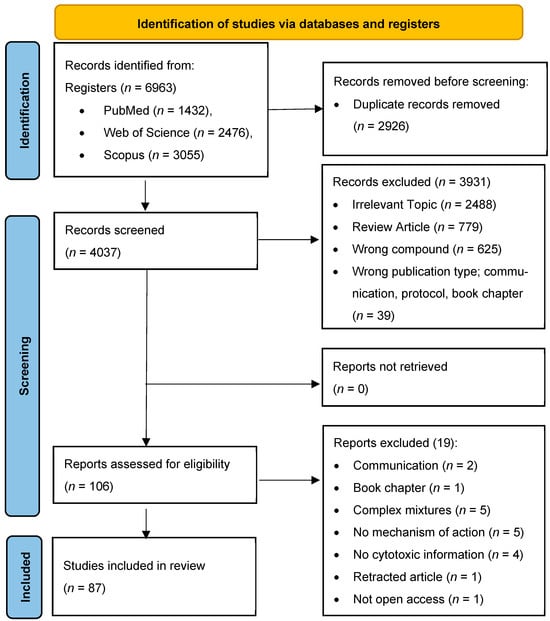

The database search revealed 6963 records for initial review, comprising 1432 from PubMed, 3055 from Scopus, and 2476 from Web of Science. Following the elimination of duplicates (n = 2924), there were 4039 articles screened based on titles and abstracts. After the exclusion of irrelevant articles (i.e., not related to the chemopreventive effects of O. europaea secoiridoids, n = 3929), a total of 110 articles were selected for a comprehensive full-text review. Ultimately, 88 articles met the previously established inclusion criteria (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram for identification of relevant studies.

3.1. Chemopreventive Mechanism of Oleocanthal, Oleuropein, and Oleacein

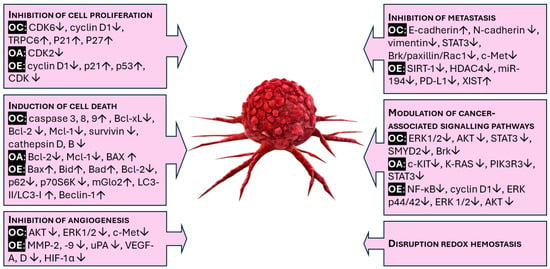

Chemoprevention by definition means the prevention of any diseases using medicines or other beneficial materials (which are mostly intaken by nutrition). Nowadays, chemoprevention refers mostly to cancer prevention, namely to hinder or delay the development, progression, or relapse of cancer. The first approved chemopreventive agent was tamoxifen, capable of diminishing the risk of developing estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. This was succeeded by the second-generation raloxifene, which proved advantageous in preventing breast cancer within high-risk populations [113]. Since then, chemoprevention has emerged as an intriguing focus and avenue for both cancer treatment and prevention. The primary mechanisms of cancer chemopreventive agents involve promoting antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities, inhibiting cell proliferation via modulating cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, necrosis, and autophagy, regulating signal transduction pathways, as well as inhibiting tumor angiogenesis and metastasis [114]. The mechanisms involved in the chemopreventive effects of oleocanthal, oleacein, and oleuropein are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The key elements of the chemopreventive effects of oleocanthal (OC), oleacein (OA), and oleuropein (OE).

3.1.1. Inhibition of Cell Proliferation (Cell Cycle Arrest)

One of the key features of a cancer cell is its ability for continuous proliferation even in the absence of growth stimuli. Cancer cells exhibit deregulated signalling cascades, allowing them operation with varying degrees of independence from proliferation signals, ultimately leading to uncontrolled growth [115]. The cell-cycle machinery exhibits abnormal activity in virtually all types of tumors, serving as a significant driving force behind tumorigenesis leading to uncontrolled proliferation [116]. Numerous chemopreventive agents are recognized for their ability to regulate cell cycle progression [117]. The primary protein regulators governing the cell cycle include cyclins, cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), and CDK inhibitors (CKIs). During mitogenesis, cells traverse a restriction point in the G1 phase before advancing into the S phase and subsequently undergoing mitosis. In the early stages of G1 phase progression, mitogenic factors enhance the expression of cyclin D1. This is followed by the binding of cyclin D1 to CDK4/6, forming cyclin/CDK complexes. Subsequently, these complexes deactivate the cell cycle restriction protein, retinoblastoma (Rb), leading to the release of E2F transcription factors, initiating the transcription of progression related genes through the S phase [118]. Upstream inhibitors, such as p21 and p27, modify the activity of the CDK-cyclin complexes.

- Oleocanthal

Oleocanthal has demonstrated a viability inhibitory effect on a wide range of cancer cells, including those associated with breast cancer [26,29,31,39,40,45], liver cancer [32,33], colon cancer [32], pancreatic cancer [26], melanoma [28], prostate cancer [27], lung cancer [38], and neuroblastoma [43]. Oleocanthal has been linked to the interruption of cancer cell progression at different stages of the cell cycle by inducing and inhibiting various protein regulators and checkpoints. For instance, in MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells, oleocanthal triggers G1/M arrest by downregulating the expression of CDK6 and cyclin D1 while upregulating p21 and p27 expression, and this is confirmed with mitosis suppression via reduction in proliferation marker (Ki-67) positive staining in the tumor tissue of the MDA-MB-231 xenograft model [39]. Oleocanthal also triggers G0/G1 phase arrest in human hepatocarcinoma cells (HCC) by suppressing cyclin D1 [33], likely via the inhibition of its transcription factor STAT3 [119]. This inhibition results in reduced STAT3 phosphorylation, impeding its nuclear translocation and DNA binding activity [33].

The role of calcium signalling in cell proliferation has been extensively documented. The recurrent calcium spikes essential for this process require the release from internal stores and influx of external calcium. Calcium signal induces resting cells (G0) to re-enter the cell cycle. Furthermore, during the G1/S transition, it may facilitate the initiation of DNA synthesis [120]. In breast cancer cells (MCF7 and MDA-MB-231), oleocanthal inhibits cell growth by decreasing transient influx of Ca2+ in a concentration-dependent manner. This is achieved through the silencing of gene expression of the Transient Receptor Potential Canonical 6 (TRPC6) channel, which is a Ca2+ transporter [31].

- b.

- Oleacein

In vitro, oleacein has shown a viability inhibitory effect on melanoma [110], neuroblastoma [111], and multiple myeloma [112]. Oleacein induces cell cycle arrest in melanoma cells at the G1/S phase transition, followed by a significant increase in the phosphorylation of Cdk2, a crucial regulator of this transition, at Tyr15. This phosphorylation event renders Cdk2 inactive, as it is typically activated when in its dephosphorylated form [110]. In multiple myeloma cells, oleacein induces cell cycle arrest by upregulating the expression of cell cycle inhibitors p27KIP1 and p21CIP1 proteins, leading to an increase in the percentage of hypodiploid cells [sub-G0 phase]. Additionally, it induces the accumulation of cells in the G0/G1 phase [112].

- c.

- Oleuropein

Oleuropein induces cell cycle arrest on a wide range of cancer cells, including those associated with breast cancer [48,51,60,81], liver cancer [108], cervical cancer [94], pancreatic cancer [67], lung cancer [80,85], and neuroblastoma [76]. In breast cancer cells, oleuropein triggers the accumulation of cells in the S phase of the cell cycle, suggesting a delay occurring during DNA replication [48,60]. This cell cycle arrest is facilitated by the downregulation of cyclin D1 and the upregulation of p21, which is a cyclin D-dependent kinase inhibitor [48]. InHepG2 cells, oleuropein prompts sub-G1 and G2/M phase arrest, linked to the upregulation of p53-a potent tumor suppressor gene, which is important in apoptosis signalling; it also activates p21, which acts as an inhibitor of G2/M phase-related proteins. Meanwhile, there is a notable reduction in CDK1 and cyclin B1 levels [108].

3.1.2. Induction of Cell Death (Apoptosis, Autophagy, and Necrosis)

The initiation and progression of all cancers are linked to the deregulation of cell proliferation and the inhibition of cell death, particularly apoptosis. In cancer, the insufficient occurrence of apoptosis results in positive selection via increased proliferation of malignant cells. Many chemopreventive substances are acknowledged for their capacity to induce cell death, effectively suppressing tumor growth. Apoptosis is typically carried out via two primary pathways: the death receptor-mediated extrinsic pathway and the mitochondria-mediated intrinsic pathway that leads to caspase activation [121]. In addition to necrosis and apoptosis, autophagy represents another form of programmed cell death relevant in cancer, among others. Autophagy, derived from Greek words meaning “self-eating”, plays a role in the extensive breakdown of long-lived cytosolic proteins and organelles. It serves as an important intracellular process for maintaining health by degrading the damaged or malignantly transformed cells, including cells with premalignant signal transduction [122].

- Oleocanthal

Oleocanthal triggers apoptosis in a broad spectrum of cancer cells [29,32,33,36,43,44,46]. Oleocanthal induces apoptosis via activation of caspase-8, -9 and -3 followed by the cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) in hepatocellular carcinoma [33], hematopoietic tumor cells [29], and breast cancer [39]. Furthermore, using Z-VAD-FMK, a pan-caspase inhibitor, oleocanthal was confirmed to induce apoptosis partially via caspase-dependent apoptosis in melanoma cells (A375) [44] and completely via caspase-dependent apoptosis in breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231) [39]. Oleocanthal activates a mitochondrial-mediated intrinsic pathway via the upregulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and mitochondrial membrane depolarization [29,32]. Moreover, oleocanthal downregulates the expression of antiapoptotic protein such as Bcl-xL, Mcl-1, Bcl-2, survivin in melanoma and hepatocarcinoma cells [28,33,44]. This results in heightened mitochondrial permeability, leading to the release of cytochrome c into the cytoplasm [123] and subsequently triggering the activation of caspase-3 through the formation of the apoptosome [124]. Interestingly, the apoptosis-inducing effect of oleocanthal extends beyond its ability to modulate antiapoptotic proteins. Oleocanthal in 20 µmol concentration also triggers lysosome-dependent cell death across various cancer cell lines, namely PC3 human prostate cancer cells, MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells, N134 murine PNET cancer cells, and BxPC3 pancreatic cancer cells. In contrast, the viability of normal cells, such as HEK293T human kidney cells, MCF10A human breast cancer cells, and BJ-hTERT human fibroblast cells, were not afflicted [26,36]. It induces lysosomal membrane permeabilization marked by robust galectin-3 translocation to lysosomes [26], leading to the release of degradative enzymes from lysosomes, such as cathepsins (cathepsin D and B), into the cytosol [26,125]. Depending on the degree of lysosomal membrane permeabilization, it can induce both apoptotic and non-apoptotic cell death [126]. A low level of lysosomal membrane permeabilization triggers apoptotic death, whereas a high level leads to rapid and direct cell death, resembling a form of necrosis.

- b.

- Oleacein

Oleacein demonstrated an increase in internucleosomal DNA fragmentation in melanoma cells, indicating proapoptotic effects. This effect was accompanied by an elevation in proapoptotic BAX mRNA levels and a significant reduction in the expression of antiapoptotic proteins BCL-2 and MCL-1 genes. Interestingly, the modulation of pro and antiapoptotic gene expression occurred through the regulation of miRNAs capable of post-transcriptionally regulating gene expression. This regulation included a significant decrease in miR-214-3p, which targets BAX, as well as a significant upregulation of miR-34a-5p and miR-16-5p, both targeting BCL2, and miR-193a-3p, targeting MCL-1 [110]. In endothelial cells, oleacein notably increased the number of cells showing fragmented DNA (subG1 population), a characteristic event linked with the induction of apoptosis, followed by the activation of caspase-7 and -3 [109]. Oleacein induces apoptosis in neuroblastoma cells via upregulating BAX and downregulating BCL-2 protein expression [111].

- c.

- Oleuropein

Oleuropein induces apoptosis in several cancer cells via activation of an intrinsic mitochondrial pathway through upregulation of a pro-apoptotic Bax protein while the levels of antiapoptotic proteins such as BCL2 and survivin decrease leading to the activation of apoptosis machinery [48,60,63,71,76,80,85,91]. Seçme et al. indicated that the mRNA expression of p53 increases in cells treated with oleuropein. Additionally, the mRNA expression of proapoptotic genes Bax, Bid, and Bad is elevated, while the mRNA expression of the antiapoptotic gene Bcl-2 is decreased [76]. In MCF7 cells, oleuropein induces cell cycle arrest at the G1 phase, which aligns with previous findings [51]. The increase in the sub-G1 phase after oleuropein treatment was also observed in lung cancer cells (A549 and H1299) followed by increased cleaved-PARP protein [80,85]. Oleuropein is also linked to another apoptosis inducer, Glyoxalase 2 (Glo2), an ancient enzyme categorized within the glyoxalase system, which demonstrates significant proapoptotic effects [127]. Antognelli et al. reported that oleuropein induces apoptosis in NSCLC cells by upregulating mGlo2, mediated by the superoxide anion and the Akt signalling pathway. Furthermore, they demonstrated that the proapoptotic effect of mGlo2 is due to the interaction of mGlo2 with the proapoptotic Bax protein [89].

Oleuropein induces autophagy in neuroblastoma cells through the Ca2+-CAMKKβ–AMPK axis. This leads to a swift release of Ca2+ from the SR stores, subsequently activating CAMKKβ. This activation results in the phosphorylation and activation of AMPK, leading to the inhibition of phospho-mTOR immunoreactivity and reduced levels of phosphorylated mTOR substrate p70 S6K [62]. In triple-negative breast cancer, oleuropein inhibits cell migration and invasion induced by HGF through autophagy by upregulation of LC3-II/LC3-I and Beclin-1, as well as downregulation of p62 [68].

3.1.3. Inhibition of Angiogenesis

Angiogenesis, which involves the creation of new blood vessels from pre-existing vasculature, plays a crucial role in the later phases of carcinogenesis. It enables tumors to expand beyond a diameter of 1–2 mm, infiltrate surrounding tissues, and ultimately metastasize [128]. Numerous chemopreventive agents, both natural and synthetic, currently under development or in clinical use, demonstrate the inhibition of new blood vessel formation.

- Oleocanthal

Oleocanthal hinders vascularization in the chorioallantoic membrane [129] of fertilized chicken eggs, exerting an inhibitory effect on angiogenesis [109]. Additionally, oleocanthal decreases viability, migratory capacity, invasive potential, and the formation of tubular-like structures of endothelial cells and human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVEC) [40,44,109]. HUVECs are commonly employed as a model system for investigating the regulation and development of angiogenesis. Moreover, at the molecular level, this inhibitory effect is likely mediated through the suppression of the phosphorylation of AKT, ERK1/2 [109], and c-Met kinase [40].

- b.

- Oleacein

Oleacein inhibits a crucial step in angiogenesis, activating proliferation in quiescent endothelial cells, which supports blood vessel formation. Additionally, oleacein suppresses the migratory and invasive capabilities of endothelial cells and the formation of tubular-like structures by these cells. Moreover, in vivo CAM assays demonstrate that treatment with oleacein leads to reduced and impaired vascularization beneath the disc and surrounding area [109].

- c.

- Oleuropein

Oleuropein disrupts the formation of melanoma tubes by inducing cell rounding and inhibiting tube retraction. Furthermore, it disrupts the organization of actin filaments within cells, thereby affecting the cytoskeleton [52]. Additionally, in vivo studies have revealed that oleuropein inhibits the high-fat diet-induced accumulation of adipocytes and M2-MΦs, as well as the expression of VEGF-A, -D, and HIF-1α in tumor tissues. Consequently, this suppresses tumor angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis in melanoma-bearing obese mice [103]. The senescent fibroblast’s SASP generates a vasculogenic environment that promotes the formation of vessels by endothelial progenitor cells [130]. Oleuropein inhibits the tube formation and migration of endothelial cells, which are dependent on fibroblast SASP, by modulating the secretion of pro-angiogenic factors in the cellular microenvironment such as MMP-2, MMP-9, and uPA [101].

3.1.4. Inhibition of Metastasis

The term “metastasis” describes the migration of cancer cells from the original tumor to adjacent tissues and distant organs, constituting the foremost factor contributing to cancer-related morbidity and mortality [131]. During the early stages of metastasis, cancer cells penetrate the basement membrane and traverse the tumor stroma [132]. In this step, the epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) becomes a crucial factor. EMT is a biological process in which epithelial cells transform, leading to the loss of their cell polarity and cell–cell adhesion. These cells acquire invasive and migratory characteristics, transforming into mesenchymal stem cells [133].

- Oleocanthal

Oleocanthal suppresses epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in human hepatocellular carcinoma and breast cancer [33,34]. It has been observed that oleocanthal enhances the expression of the epithelial marker E-cadherin while simultaneously reducing the expression of mesenchymal markers N-cadherin and vimentin. This modulation of proteins associated with epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) occurs through the downregulation of twist transcription factors. The downregulation is achieved by diminishing the binding between STAT3 and the twist gene promoter, thereby inhibiting the activity of the twist promoter. Moreover, oleocanthal demonstrates the inhibition of IL6-induced activation of STAT3 in HEPG2 cells [33]. In an in vivo investigation using breast cancer orthotopic xenograft tumors, the administration of oleocanthal exhibited the capacity to stabilize E-cadherin while concurrently reducing vimentin expression in recurrent tumors derived from both BT-474 and MDA-MB-231. Additionally, oleocanthal also resulted in a decrease in the phosphorylation levels of both MET and HER2 in recurrent tumors originating from animals inoculated with BT-474 [34]. Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) is recognized for its role in promoting the development and progression, including metastasis, of breast carcinoma [134]. HGF stimulates cell migration in breast cancer cells and oleocanthal attenuates this effect by suppressing the phosphorylation of Brk, paxillin, Rac1, and c-Met. This suggests that inhibition, at least in part, occurs through the suppression of the Brk/paxillin/Rac1 and the c-Met signalling pathway [39].

- b.

- Oleacein

One of the key characteristics of metastatic cancer cells is their capacity to adhere to extracellular matrices. Notably, oleacein effectively suppressed the adhesion of neuroblastoma cells to collagen I-coated wells. Furthermore, oleacein also hindered cell migration in these models [111].

- c.

- Oleuropein

Oleuropein inhibits breast cancer cells migration and invasion ability [52]. In MCF-7 breast cancer cells, oleuropein inhibits the migration ability of cells by suppressing EMT through increasing the expression of p53, which increases miR43a expression that leads to the downregulation of sirtuin-1 (SIRT1), resulting in the downregulation of mesenchymal markers (for example, matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 (MMP-2 and MMP-9)), downregulation of the EMT inducer (ZEB1), and upregulation of the epithelial marker (E-CAD) [92,135]. Interestingly, it has been reported that SIRT1 forms a complex with ZEB1 at the E-CAD promoter, deacetylating histones H4K16 and H3K9, which reduces RNA Pol II binding to the E-CAD promoter and subsequently suppresses its transcription [136]. Interestingly, oleuropein in N2a cells downregulated p53 and upregulated SIRT1 [137]. The difference is caused by the presence of estrogen receptors: in MCF-7 cells, the oleuropein bonds to the mentioned receptors, while estrogen receptors in N2a cells are missing [138].

Moreover, oleuropein reduces invasiveness of MCF-7 cells via dose-dependently reducing the expression of the epigenetic factor HDAC4 [82]. Additionally, in triple-negative breast cancer cells (TNBCs), oleuropein modulates the miR-194/XIST/PD-L1 loop by decreasing PD-L1 and miR-194 levels while upregulating XIST, thereby contributing to its ability to reduce the migration capacity of MDA-MB-231 cells [75].

3.1.5. Modulation of Cancer-Associated Signaling Pathways

Ever since the initial identification of oncogenes such as BRAF, MYC, KIT, and RAS, along with tumor suppressor genes like BRCA1, TP53, and PTEN, genetic abnormalities associated with cancer have been extensively documented [139]. Presently, signalling pathways and molecular networks are acknowledged for their crucial roles in governing vital pro-survival and pro-growth cellular processes. Consequently, they are primarily implicated not only in the initiation of cancer but also in its potential treatment [140]. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR and RAF/MEK/ERK pathways commonly undergo activation and dysregulation across nearly all types of neoplasms, often exhibiting alterations in their various components. These RAF/MEK/ERK signalling cascades facilitate the transmission of signals from the cell surface to the nucleus, thereby modulating gene expression, cell cycle progression, and apoptosis [141,142].

- Oleocanthal

Oleocanthal inhibits the ERK1/2 and AKT oncogenic pathways in both melanoma and endothelial cells [28,109]. This inhibition leads to the downregulation of the antiapoptotic protein BCL-2, consequently reducing the viability of melanoma cells [28]. Furthermore, it demonstrates an antiangiogenic effect by suppressing endothelial cell proliferation, invasion, and tube formation [109]. According to molecular modelling studies, it has been suggested that oleocanthal demonstrates nine out of ten crucial binding interactions akin to those observed with a potent natural inhibitor of dual PIK3-γ/mTOR. Remarkably, the administration of oleocanthal resulted in a notable reduction in phosphorylated mTOR within the metastatic breast cancer cell line (MDA-MB-231) [37]. Interestingly, oleocanthal inhibits the upstream signalling of mTOR and MAPK, particularly targeting SMYD2, which plays a crucial role in prostate cancer proliferation and recurrence [27]. Another signalling pathway playing a significant role in cancer progression is STAT-3, which regulates numerous cellular processes such as the cell cycle, cell proliferation, cellular apoptosis, and tumorigenesis. Persistent activation of STAT-3 has been observed in various cancer types, and a high level of phosphorylation of STAT-3 may be linked to a poor prognosis in cancer [143]. Oleocanthal inhibits the phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of STAT3 in melanoma [44] and hepatocellular carcinoma [33]. Oleocanthal has also demonstrated the ability to inhibit the Brk/Paxillin/Rac1 pathway by suppressing Brk phosphorylation, subsequently leading to the downregulation of Rac1 and paxillin phosphorylation. These inhibitory effects have contributed significantly to the suppression of migration and invasion abilities in HGF-induced breast cancer cells [39].

- b.

- Oleacein

Oleacein in melanoma cells reduces the mRNA expression of c-KIT, K-RAS, and PIK3R3, which are crucial effectors responsible for heightened mTOR activation. When hyperactivated, mTOR signalling facilitates cell proliferation and metabolism, which contribute to both tumor initiation and progression [144]. Interestingly, oleacein counters the expression of these genes by inducing an increase in the expression of miR-34a-5p, miR-193a-3p, miR-193a-5p, miR-16-5p, and miR-155-5p [110]. These microRNAs serve as regulatory elements capable of decreasing the transcriptional levels of the target genes (c-KIT, K-RAS, and PIK3R3) [145,146,147]. In endothelial cells, oleacein hampers the PI3K/AKT and ERK/MAPK signalling pathways, which may contribute to its antiangiogenic effect [109]. In neuroblastoma cells, oleacein decreases the phosphorylation of STAT3, which may be associated with the observed increasing expression level of Bax and P53 genes as well as the decrease in Bcl-2, ultimately leading to apoptosis induction in these cells [111].

- c.

- Oleuropein

The NFκB signalling pathway plays a central role in the development and progression of cancer, exerting extensive involvement. NFκB facilitates tumor cell survival, proliferation, and angiogenesis by regulating the expression of target genes such as cyclin D1, IL6, BCLXL, BCL2, XIAP, and VEGF [148]. In breast cancer cells, oleuropein downregulates NFκB and concurrently suppresses cyclin D1, which is one of the most important targets of NFκB [48].

Another crucial signalling pathway in cancer is the MAPKs. The involvement of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) in the initiation and progression of cancer have become more and more recognized. They have critical roles in cell differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis. The MAPK family comprises extracellular signal-regulated kinase p38 MAPK, (ERK p44/42) and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) [149,150]. In lung cancer, the A549 and H1299 cells exhibited an increase in the phosphorylation of the p38MAPK protein in response to oleuropein, but oleuropein did not activate JNK [80,85]. Subsequently, this resulted in the activation of the ATF-2 via phosphorylation, which is a downstream factor of p38MAPK. Notably, in the cells treated with oleuropein, activation of the p38MAPK pathway induced apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner, with the maximum concentration of 200 μM [80,85]. Additionally, oleuropein inhibits the E2-dependent activation of ERK1/2 in breast cancer [54] and thyroid cancer cells [78].

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR (PAM) signalling pathway constitutes a profoundly conserved signal transduction network within eukaryotic cells, fostering cell survival, growth, and progression through the cell cycle. Dysfunctions within this pathway, such as PI3K hyperactivity, PTEN loss of function, and AKT gain of function, are notorious catalysts of treatment resistance and cancer progression [129]. In glioma cells, oleuropein attenuates AKT signalling, leading to the upregulation of BAX and the downregulation of BCL-2, resulting in reduced cell viability and induction of apoptosis [88]. Oleuropein in a concentration of 100 μM and 500 μM in a dose-dependent manner also suppresses AKT signalling by inhibiting pAkt (Ser473) and Akt (Thr308) in LNcaP and DU145 prostate cancer cell lines and BPH-1 non-malignant cells; however, in the DU145 cells, AKT activity is generally higher. Furthermore, the oleuropein increased the intracellular quantity of the protective thiol group and reduced the ROS activity in the examined cell lines, but in DU145 cells, the oleuropein in 500 μM concentration paradoxically decreased thiol group quantity and increased the measured ROS activity [61]. Moreover, oleuropein hinders mTOR signalling pathways and induces autophagy in TgCRND8 mice [62].

3.1.6. Disruption of Redox Hemostasis and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress

An imbalance between the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the cell’s natural antioxidant defenses leads to oxidative stress, which has been connected to the emergence of cancer. ROS disrupts redox homeostasis, leading to the initiation of abnormal signalling networks that foster tumorigenesis and promote tumor formation [151]. Reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as superoxide radicals (O2−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radicals (OH), are chemically active molecules that play a crucial role in the biological functions of tumor cells. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) demonstrate paradoxical effects on cancers. At mild or even in low concentration, they promote tumorigenesis and facilitate the progression of cancer cells. Conversely, an excessive concentration results in cell death but depends on the source and type of ROS, too [152].

- Oleocanthal

The administration of oleocanthal induced the expression of γH2AX, a marker indicating DNA damage, and provoked a dose-dependent increase in intracellular ROS production. Additionally, it led to mitochondrial depolarization, resulting in the inhibition of colony formation capacity in hepatocellular carcinoma and colorectal carcinoma cells [32]. In another study, oleocanthal was found neurotoxic through oxidative stress in neuroblastoma cells by decreasing their viability, while in BMDN cells, the cytotoxicity was negligible. Notably, there was a significant rise in neuroblastoma cells in the immunoreactivity of i-NOS and e-NOS, which serve as indicators for evaluating oxidative stress [43]. The generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) observed triggers the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. This, combined with the swift cleavage and activation of initiator caspases, constitutes pivotal components of the intrinsic apoptosis pathway [153].

- b.

- Oleuropein

Oleuropein exhibits beneficial effects as an anticancer agent in the N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU)-induced brain tumor model in Wistar rats through redox control mechanisms involving endogenous non-enzymatic and enzymatic antioxidant defense systems. These effects are dependent on the gender of the animals: namely the gene expression and activity of catalase enzymes were increased in male rats [66]. Jamshed et al. reported that oleuropein possesses potent free radical scavenging properties and effectively inhibits the formation of 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine (8-OH-dG) in tamoxifen-induced oxidative DNA damage in Balb/c mice [105]. In thyroid cancer cells, oleuropein has the capability to decrease the proliferation, and this effect is linked to a reduction in H2O2-induced ROS levels [78]. Interestingly, at elevated doses, oleuropein impedes the growth and viability of ovarian cancer cells by increasing the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and levels of LIP. Consequently, this disrupts the S-phase of the cell cycle and initiates apoptosis [90].

4. Discussion

The well-documented health benefits associated with the Mediterranean diet, with extra virgin olive oil as a cornerstone, are strongly supported by extensive epidemiological research. Secoiridoids from O. europaea such as oleocanthal, oleuropein, and oleacein exhibit broad therapeutic potential, adeptly addressing a variety of health concerns ranging from inflammatory and neurodegenerative conditions to cancer. To the best of our knowledge, this systematic review provides the first comprehensive summary of the chemopreventive potential of oleocanthal, oleuropein, and oleacein. Our findings not only corroborate the chemopreventive efficacy of these compounds but also reveal new insights into their mechanism of action across different cancer cell lines. Compared to the previous review by Fabiani. [4], which focused primarily on the in vivo anti-cancer activities of secoiridoid phenols, and the narrative review by Emma et al. [5], which provided a critical analysis of preclinical studies, our review offers a detailed mechanistic analysis and includes the latest studies up to 10 October 2023. This review highlights the pleiotropic effects of secoiridoids across different tissue types, emphasizes their role in modulating various pathways involved in cancer progression, and comprehensively combines in vitro and in vivo studies examining the use of these compounds to treat inflammation and various types of cancer. Also, in our systematic review, we complement the narrative review of Emma et al. about the preclinical effects of the most relevant secoiridoids by providing novel insights into the specific mechanisms of action and detailed chemopreventive effects of oleocanthal, oleacein, and oleuropein across different cancer cell lines.

The three compounds are chemically related, and although their mechanisms of action are somehow different, the key elements are overlapping. The ability to inhibit cell proliferation and induce cell cycle arrest is essential, addressing one of the hallmarks of cancer cells: the capacity to grow continuously even in the absence of external stimuli. Moreover, the role of secoiridoids in inducing apoptosis offers a direct mechanism to increase the survival of patients with cancer. Apoptosis is a natural barrier to cancer progression, which is often circumvented or suppressed in tumor cells. The anti-angiogenic and anti-metastatic activities of these compounds further expand their therapeutic potential. By inhibiting angiogenesis, secoiridoids prevent tumors from developing new blood vessels needed for oxygen and nutrient supply, thus effectively starving the tumor and limiting its growth and spread. Similarly, by suppressing epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT), oleocanthal and related compounds inhibit the ability of cancer cells to invade surrounding tissues and metastasize to distant organs, a critical step in the progression of cancer. Moreover, their impact on redox homeostasis and induction of oxidative stress in cancer cells taps into the balance between ROS production and antioxidant defense, driving cancer cells towards apoptosis through oxidative damage without harming the normal cells. For the sake of completeness, we need to mention that it is virtually contradicting that oleuropein in breast cancer cells decreases the SIRT1 level and in gastric adenocarcinoma cells it increases the KRAS while oleacein in 501Mel cells decreases the KRAS and mTOR expression but all mechanisms lead to chemopreventive effects [91,92,109]. This is explained by the fact that secondary signal transducers correlated to tumor suppressors (such as SIRT1) or potential oncogens (for example, mTOR, and KRAS) behave pleiotropically depending on the tissue or cell type. For example, both SIRT1 and P53 contribute to the effects of chemopreventive agents if examined in a stand-alone experiment. Practically, their balanced activity contributes to maintaining cell homeostasis regarding proliferation [154]. Increasing p53 gene expression generally exerts tumorsuppressor effects, while the same is true on SIRT1 through its mTOR and NFκB inhibiting effect, but SIRT1 and p53 can cross-regulate each other [92,155], namely the deacethylase activity of SIRT1 can deactivate p53. Hence, oleuropein exerts pleiotropic effects on intracellular signal transduction, namely that estrogen receptor is needed for oleuropein to increase p53 activity.

Both olive oil and olive leaf are chemically complex matrices that comprise a variety of chemical substances. Secoiridoids are important in the effects of these plant compounds, reducing the risk of various chronic diseases including cancer, even though they are not the most important constituents quantitatively. Their role in the chemopreventive effects of olive oil and leaf is unquestionable, and the mechanisms of their effects are confirmed in several experiments, as summarized in our review. The synergies of the mentioned chemopreventive mechanisms are obvious in smaller doses, too, since the in vitro literature mentions 500 μM concentrations of oleuropein as maximal effective doses. To reach such a quantity in vivo, however, consumption of approximately 35 kg of extra virgin olive oil is required. On the other hand, a 20 µmol concentration of oleocanthal was also mentioned as an effective in vivo dose.

This review highlights the distinct anticancer mechanisms of oleocanthal, oleacein, and oleuropein, despite their shared structural features. Oleocanthal primarily induces apoptosis through lysosomal membrane permeabilization, leading to cellular toxicity and reduced tumor burden. Oleacein, on the other hand, is notable for its anti-angiogenic and anti-metastatic effects, which prevent tumor spread and the formation of new blood vessels. Oleuropein exhibits a more variable profile; it can either decrease levels of tumor suppressors like SIRT1 or alter oncogene expressions such as KRAS and mTOR, depending on the cancer type. While all three compounds share common mechanisms, such as cell cycle arrest and modulation of redox homeostasis, their individual pathways contribute uniquely to their chemopreventive activities. This detailed comparison underscores the diverse mechanisms through which these secoiridoids exert their anticancer effects, enhancing their potential as therapeutic agents in cancer treatment.

5. Conclusions

In summary, the beneficial effects of secoiridoid intake, for example, in an increased dose utilizing food supplements is underpined. The clinical significance of the chemopreventive effects is supported by the negative correlation between olive oil consumption and cancer risk according to epidemiological studies. Compared to their counterparts, oleacein was the least explored and was only studied in four articles. Notably, none of these studies reported its activity in disrupting redox hemostasis and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Consequently, further investigations are warranted to unravel additional chemopreventive mechanisms attributed to oleacein. Moreover, given the documented chemopreventive properties of oleocanthal, oleuropein, and oleacein, it becomes imperative to substantiate their efficacy through robust randomized clinical trials. Such trials are essential to provide concrete clinical evidence supporting the incorporation of these compounds into mainstream clinical practices, thereby adding treatment strategies to prevent cancer or improve the life quality of patients with cancer by hindering progradiation and supporting chemoterapeutical medicines.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nu16162755/s1, Supplementary Information S1: Description of search strategies applied for PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science databases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.C. and F.B.; methodology, M.A.B. and I.Y.K.; software, H.H. and I.Y.K.; validation, D.C., M.A.B. and F.B.; formal analysis, I.Y.K. and H.H.; investigation, I.Y.K., M.A.B. and H.H.; resources, D.C.; data curation, M.A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, I.Y.K., H.H. and M.A.B.; writing—review and editing, D.C. and F.B.; visualization, D.C.; supervision, D.C.; funding acquisition, D.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Innovation and Technology of Hungary from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund, financed under the TKP2021-EGA funding scheme, project No. TKP2021-EGA-32.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- WHO. Global Cancer Burden Growing, Amidst Mounting Need for Services; WHO: Lyon, France; Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/01-02-2024-global-cancer-burden-growing--amidst-mounting-need-for-services (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Chen, S.; Cao, Z.; Prettner, K.; Kuhn, M.; Yang, J.; Jiao, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Geldsetzer, P.; Bärnighausen, T.; et al. Estimates and Projections of the Global Economic Cost of 29 Cancers in 204 Countries and Territories from 2020 to 2050. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocarnik, J.M.; Compton, K.; Dean, F.E.; Fu, W.; Gaw, B.L.; Harvey, J.D.; Henrikson, H.J.; Lu, D.; Pennini, A.; Xu, R.; et al. Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived with Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years for 29 Cancer Groups from 2010 to 2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. JAMA Oncol. 2022, 8, 420–444. [Google Scholar]

- Fabiani, R. Anti-Cancer Properties of Olive Oil Secoiridoid Phenols: A Systematic Review of in Vivo Studies. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 4145–4159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emma, M.R.; Augello, G.; Stefano, V.; Azzolina, A.; Giannitrapani, L.; Montalto, G.; Cervello, M.; Cusimano, A. Potential Uses of Olive Oil Secoiridoids for the Prevention and Treatment of Cancer: A Narrative Review of Preclinical Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiles, J.L.; Ramírez-Tortosa, M.C.; Yaqoob, P. Olive Oil and Health; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Albini, A.; Albini, F.; Corradino, P.; Dugo, L.; Calabrone, L.; Noonan, D.M. From Antiquity to Contemporary Times: How Olive Oil by-Products and Waste Water Can Contribute to Health. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1254947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keys, A.; Mienotti, A.; Karvonen, M.J.; Aravanis, C.; Blackburn, H.; Buzina, R.; Djordjevic, B.S.; Dontas, A.S.; Fidanza, F.; Keys, M.H.; et al. The Diet and 15-Year Death Rate in the Seven Countries Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1986, 124, 903–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Lopez, C.; Carpena, M.; Lourenço-Lopes, C.; Gallardo-Gomez, M.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Barba, F.J.; Prieto, M.A.; Simal-Gandara, J. Bioactive Compounds and Quality of Extra Virgin Olive Oil. Foods 2020, 9, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortes, C.; Forastiere, F.; Farchi, S.; Mallone, S.; Trequattrinni, T.; Anatra, F.; Schmid, G.; Perucci, C.A. The Protective Effect of the Mediterranean Diet on Lung Cancer. Nutr. Cancer 2003, 46, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelucchi, C.; Bosetti, C.; Negri, E.; Lipworth, L.; La Vecchia, C. Olive Oil and Cancer Risk: An Update of Epidemiological Findings through 2010. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2011, 17, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosetti, C.; La Vecchia, C.; Talamini, R.; Negri, E.; Levi, F.; Maso, L.D.; Franceschi, S. Food Groups and Laryngeal Cancer Risk: A Case-control Study from Italy and Switzerland. Int. J. Cancer 2002, 100, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markellos, C.; Ourailidou, M.-E.; Gavriatopoulou, M.; Halvatsiotis, P.; Sergentanis, T.N.; Psaltopoulou, T. Olive Oil Intake and Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0261649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinkman, M.T.; Buntinx, F.; Kellen, E.; Dongen, M.C.; Dagnelie, P.C.; Muls, E.; Zeegers, M.P. Consumption of Animal Products, Olive Oil and Dietary Fat and Results from the Belgian Case–Control Study on Bladder Cancer Risk. Eur. J. Cancer 2011, 47, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, M.; Bai, Y.; Tian, H.; Zhao, X. The Chemical Composition and Health-Promoting Benefits of Vegetable Oils—A Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 6393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De La Cruz, J.P.; Villalobos, M.A.; Carmona, J.A.; Martín-Romero, M.; Smith-Agreda, J.M.; de la Cuesta, F.S. Antithrombotic Potential of Olive Oil Administration in Rabbits with Elevated Cholesterol. Thromb. Res. 2000, 100, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, L.F.; Jespersen, J.; Marckmann, P. Are Olive Oil Diets Antithrombotic? Diets Enriched with Olive, Rapeseed, or Sunflower Oil Affect Postprandial Factor VII Differently. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 70, 976–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorzynik-Debicka, M.; Przychodzen, P.; Cappello, F.; Kuban-Jankowska, A.; Marino Gammazza, A.; Knap, N.; Wozniak, M.; Gorska-Ponikowska, M. Potential Health Benefits of Olive Oil and Plant Polyphenols. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montedoro, G.; Servili, M.; Baldioli, M.; Selvaggini, R.; Miniati, E.; Macchioni, A. Simple and Hydrolyzable Compounds in Virgin Olive Oil. 3. Spectroscopic Characterizations of the Secoiridoid Derivatives. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1993, 41, 2228–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, G.K.; Keast, R.S.; Morel, D.; Lin, J.; Pika, J.; Han, Q. Phytochemistry: Ibuprofen-like Activity in Extra-Virgin Olive Oil. Nature 2005, 437, 45–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, K.; Adsersen, A.; Christensen, S.B.; Jensen, S.R.; Nyman, U.; Smitt, U.W. Isolation of an Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitor from Olea Europaea and Olea Lancea. Phytomedicine 1996, 2, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-García, I.; Ortíz-Flores, R.; Badía, R.; García-Borrego, A.; García-Fernández, M.; Lara, E.; Martín-Montañez, E.; García-Serrano, S.; Valdés, S.; Gonzalo, M.; et al. Rich Oleocanthal and Oleacein Extra Virgin Olive Oil and Inflammatory and Antioxidant Status in People with Obesity and Prediabetes. The APRIL Study: A Randomised, Controlled Crossover Study. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 42, 1389–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HMPC. Assessment Report on Olea Europaea L., Folium; European Medicines Agency: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano-Castellón, J.; López-Yerena, A.; Rinaldi De Alvarenga, J.F.; Romero Del Castillo-Alba, J.; Vallverdú-Queralt, A.; Escribano-Ferrer, E.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Health-Promoting Properties of Oleocanthal and Oleacein: Two Secoiridoids from Extra-Virgin Olive Oil. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 2532–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, L.; Molnar, R.; Tomesz, A.; Deutsch, A.; Darago, R.; Varjas, T.; Ritter, Z.; Szentpeteri, J.L.; Andreidesz, K.; Mathe, D.; et al. Olive Oil Improves While Trans Fatty Acids Further Aggravate the Hypomethylation of LINE-1 Retrotransposon DNA in an Environmental Carcinogen Model. Nutrients 2022, 14, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goren, L.; Zhang, G.; Kaushik, S.; Breslin, P.A.S.; Du, Y.-C.N.; Foster, D.A. (−)-Oleocanthal and (−)-Oleocanthal-Rich Olive Oils Induce Lysosomal Membrane Permeabilization in Cancer Cells. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddique, A.B.; Ebrahim, H.Y.; Tajmim, A.; King, J.A.; Abdelwahed, K.S.; Abd Elmageed, Z.Y.; El Sayed, K.A. Oleocanthal Attenuates Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Progression and Recurrence by Targeting SMYD2. Cancers 2022, 14, 3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fogli, S.; Arena, C.; Carpi, S.; Polini, B.; Bertini, S.; Digiacomo, M.; Gado, F.; Saba, A.; Saccomanni, G.; Breschi, M.C.; et al. Cytotoxic Activity of Oleocanthal Isolated from Virgin Olive Oil on Human Melanoma Cells. Nutr. Cancer 2016, 68, 873–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastorio, C.; Torres-Rusillo, S.; Ortega-Vidal, J.; Jiménez-López, M.C.; Iañez, I.; Salido, S.; Santamaría, M.; Altarejos, J.; Molina, I.J. (−)-Oleocanthal Induces Death Preferentially in Tumor Hematopoietic Cells through Caspase Dependent and Independent Mechanisms. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 11334–11341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayoub, N.M.; Siddique, A.B.; Ebrahim, H.Y.; Mohyeldin, M.M.; El Sayed, K.A. The Olive Oil Phenolic (−)-Oleocanthal Modulates Estrogen Receptor Expression in Luminal Breast Cancer in Vitro and in Vivo and Synergizes with Tamoxifen Treatment. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 810, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diez-Bello, R.; Jardin, I.; Lopez, J.J.; El Haouari, M.; Ortega-Vidal, J.; Altarejos, J.; Salido, G.; Salido, S.; Rosado, J. (−)-Oleocanthal Inhibits Proliferation and Migration by Modulating Ca2+ Entry through TRPC6 in Breast Cancer Cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Mol. Cell Res. 2019, 1866, 474–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusimano, A.; Balasus, D.; Azzolina, A.; Augello, G.; Emma, M.R.; Di Sano, C.; Gramignoli, R.; Strom, S.C.; Mccubrey, J.A.; Montalto, G.; et al. Oleocanthal Exerts Antitumor Effects on Human Liver and Colon Cancer Cells through ROS Generation. Int. J. Oncol. 2017, 51, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, T.; Meng, Q.; Han, J.; Sun, H.; Li, L.; Song, R.; Sun, B.; Pan, S.; Liang, D.; Liu, L. (−)-Oleocanthal Inhibits Growth and Metastasis by Blocking Activation of STAT3 in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 43475–43491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, A.B.; Ayoub, N.M.; Tajmim, A.; Meyer, S.A.; Hill, R.A.; El Sayed, K.A. (−)-Oleocanthal Prevents Breast Cancer Locoregional Recurrence After Primary Tumor Surgical Excision and Neoadjuvant Targeted Therapy in Orthotopic Nude Mouse Models. Cancers 2019, 11, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, D.N.S.; Mamat, T.H.T.; Surien, O.; Taib, I.S.; Masre, S.F. Pre-Initiation Effect of Oleuropein towards Apoptotic and Oxidative Stress Levels on the Early Development of Two-Stage Skin Carcinogenesis. J. Krishna Inst. Med. Sci. Univ. 2019, 8, 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- LeGendre, O.; Breslin, P.A.; Foster, D.A. (−)-Oleocanthal Rapidly and Selectively Induces Cancer Cell Death via Lysosomal Membrane Permeabilization. Mol. Cell. Oncol. 2015, 2, e1006077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanfar, M.A.; Bardaweel, S.K.; Akl, M.R.; El Sayed, K.A. Olive Oil-Derived Oleocanthal as Potent Inhibitor of Mammalian Target of Rapamycin: Biological Evaluation and Molecular Modeling Studies. Phytother. Res. 2015, 29, 1776–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, A.B.; Kilgore, P.; Tajmim, A.; Singh, S.S.; Meyer, S.A.; Jois, S.D.; Cvek, U.; Trutschl, M.; El Sayed, K.A. (−)-Oleocanthal as a Dual c-MET-COX2 Inhibitor for the Control of Lung Cancer. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akl, M.R.; Ayoub, N.M.; Mohyeldin, M.M.; Busnena, B.A.; Foudah, A.I.; Liu, Y.Y.; Sayed, K.A.E. Olive Phenolics as C-Met Inhibitors: (−)-Oleocanthal Attenuates Cell Proliferation, Invasiveness, and Tumor Growth in Breast Cancer Models. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnagar, A.Y.; Sylvester, P.W.; El Sayed, K.A. (−)-Oleocanthal as a c-Met Inhibitor for the Control of Metastatic Breast and Prostate Cancers. Planta Med. 2011, 77, 1013–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qusa, M.H.; Abdelwahed, K.S.; Siddique, A.B.; El Sayed, K.A. Comparative Gene Signature of (−)-Oleocanthal Formulation Treatments in Heterogeneous Triple Negative Breast Tumor Models: Oncological Therapeutic Target Insights. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajmim, A.; Siddique, A.B.; El Sayed, K. Optimization of Taste-Masked (−)-Oleocanthal Effervescent Formulation with Potent Breast Cancer Progression and Recurrence Suppressive Activities. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünsal, Ü.; Mete, M.; Aydemir, I.; Duransoy, Y.K.; Umur, A.; Tuglu, M.I. Inhibiting Effect of Oleocanthal on Neuroblastoma Cancer Cell Proliferation in Culture. Biotech. Histochem. 2020, 95, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y.; Wang, J.; Peng, L. (−)-Oleocanthal Exerts Anti-Melanoma Activities and Inhibits STAT3 Signalling Pathway. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 37, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karousi, P.; Kontos, C.K.; Papakotsi, P.; Kostakis, I.K.; Skaltsounis, A.L.; Scorilas, A. Next-Generation Sequencing Reveals Altered Gene Expression and Enriched Pathways in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells Treated with Oleuropein and Oleocanthal. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2023, 23, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossio, S.; Perri, A.; Malivindi, R.; Giordano, F.; Rago, V.; Mirabelli, M.; Salatino, A.; Brunetti, A.; Greco, E.A.; Aversa, A. Oleuropein Counteracts Both the Proliferation and Migration of Intra- and Extragonadal Seminoma Cells. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visioli, F.; Bellosta, S.; Galli, C. Oleuropein, the Bitter Principle of Olives, Enhances Nitric Oxide Production by Mouse Macrophages. Life Sci. 1998, 62, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamin, M.H.; Daghestani, M.H.; Omer, S.A.; Elobeid, M.A.; Virk, P.; Al-Olayan, E.M.; Hassan, Z.K.; Mohammed, O.B.; Aboussekhra, A. Olive Oil Oleuropein Has Anti-Breast Cancer Properties with Higher Efficiency on ER-Negative Cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 53, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Przychodzen, P.; Wyszkowska, R.; Gorzynik-Debicka, M.; Kostrzewa, T.; Kuban-Jankowska, A.; Gorska-Ponikowska, M. Anticancer Potential of Oleuropein, the Polyphenol of Olive Oil, With 2-Methoxyestradiol, Separately or in Combination, in Human Osteosarcoma Cells. Anticancer Res. 2019, 39, 1243–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzzolini, J.; Peppicelli, S.; Andreucci, E.; Bianchini, F.; Scardigli, A.; Romani, A.; La Marca, G.; Nediani, C.; Calorini, L. Oleuropein, the Main Polyphenol of Olea Europaea Leaf Extract, Has an Anti-Cancer Effect on Human BRAF Melanoma Cells and Potentiates the Cytotoxicity of Current Chemotherapies. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Talorete, T.P.; Yamada, P.; Isoda, H. Anti-Proliferative and Apoptotic Effects of Oleuropein and Hydroxytyrosol on Human Breast Cancer MCF-7 Cells. Cytotechnology 2009, 59, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamdi, H.K.; Castellon, R. Oleuropein, a Non-Toxic Olive Iridoid, Is an Anti-Tumor Agent and Cytoskeleton Disruptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 334, 769–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioti, K.; Papachristodoulou, A.; Benaki, D.; Aligiannis, N.; Skaltsounis, A.L.; Mikros, E.; Tenta, R. Assessment of the Nutraceutical Effects of Oleuropein and the Cytotoxic Effects of Adriamycin, When Administered Alone and in Combination, in MG-63 Human Osteosarcoma Cells. Nutrients 2021, 13, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirianni, R.; Chimento, A.; Luca, A.; Casaburi, I.; Rizza, P.; Onofrio, A.; Iacopetta, D.; Puoci, F.; Andò, S.; Maggiolini, M.; et al. Oleuropein and Hydroxytyrosol Inhibit MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cell Proliferation Interfering with ERK1/2 Activation. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2010, 54, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamy, S.; Ouanouki, A.; Béliveau, R.; Desrosiers, R.R. Olive Oil Compounds Inhibit Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor-2 Phosphorylation. Exp. Cell Res. 2014, 322, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, Y.; Sumiyoshi, M. Olive Leaf Extract and Its Main Component Oleuropein Prevent Chronic Ultraviolet B Radiation-Induced Skin Damage and Carcinogenesis in Hairless Mice. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 2079–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Ahn, K.S.; Shanmugam, M.K.; Wang, H.; Shen, H.; Arfuso, F.; Chinnathambi, A.; Alharbi, S.A.; Chang, Y.; Sethi, G.; et al. Oleuropein Induces Apoptosis via Abrogating NF-κB Activation Cascade in Estrogen Receptor-Negative Breast Cancer Cells. J. Cell Biochem. 2019, 120, 4504–4513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.M.; Chai, E.Q.; Cai, H.Y.; Miao, G.Y.; Ma, W. Oleuropein Induces Apoptosis via Activation of Caspases and Suppression of Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Protein Kinase B Pathway in HepG2 Human Hepatoma Cell Line. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 11, 4617–4624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzekaki, E.E.; Geromichalos, G.; Lavrentiadou, S.N.; Tsantarliotou, M.P.; Pantazaki, A.A.; Papaspyropoulos, A. Oleuropein Is a Natural Inhibitor of PAI-1-Mediated Proliferation in Human ER-/PR- Breast Cancer Cells. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2021, 186, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messeha, S.S.; Zarmouh, N.O.; Asiri, A.; Soliman, K.F.A. Gene Expression Alterations Associated with Oleuropein-Induced Antiproliferative Effects and S-Phase Cell Cycle Arrest in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanella, L.; Acquaviva, R.; Di Giacomo, C.; Sorrenti, V.; Galvano, F.; Santangelo, R.; Cardile, V.; Gangia, S.; D’Orazio, N.; Abraham, N.G. Antiproliferative Effect of Oleuropein in Prostate Cell Lines. Int. J. Oncol. 2012, 41, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigacci, S.; Miceli, C.; Nediani, C.; Berti, A.; Cascella, R.; Pantano, D.; Nardiello, P.; Luccarini, I.; Casamenti, F.; Stefani, M. Oleuropein Aglycone Induces Autophagy via the AMPK/mTOR Signalling Pathway: A Mechanistic Insight. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 35344–35357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Z.K.; Elamin, M.H.; Omer, S.A.; Daghestani, M.H.; Al-Olayan, E.S.; Elobeid, M.A.; Virk, P. Oleuropein Induces Apoptosis via the P53 Pathway in Breast Cancer Cells. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2014, 14, 6739–6742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Z.K.; Elamin, M.H.; Daghestani, M.H.; Omer, S.A.; Al-Olayan, E.M.; Elobeid, M.A.; Virk, P.; Mohammed, O.B. Oleuropein Induces Anti-Metastatic Effects in Breast Cancer. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2012, 13, 4555–4559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giner, E.; Recio, M.C.; Ríos, J.L.; Cerdá-Nicolás, J.M.; Giner, R.M. Chemopreventive Effect of Oleuropein in Colitis-Associated Colorectal Cancer in C57bl/6 Mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, 60, 242–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Expósito, M.J.; Carrera-González, M.P.; Mayas, M.D.; Martínez-Martos, J.M. Gender Differences in the Antioxidant Response of Oral Administration of Hydroxytyrosol and Oleuropein against N-Ethyl-N-Nitrosourea (ENU)-Induced Glioma. Food Res. Int. 2021, 140, 110023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldsmith, C.D.; Bond, D.R.; Jankowski, H.; Weidenhofer, J.; Stathopoulos, C.E.; Roach, P.D.; Scarlett, C.J. The Olive Biophenols Oleuropein and Hydroxytyrosol Selectively Reduce Proliferation, Influence the Cell Cycle, and Induce Apoptosis in Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.Y.; Zhu, J.S.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, W.J.; Jiang, S.; Long, Y.F.; Wu, B.; Ding, T.; Huan, F.; Wang, S.-L. Hydroxytyrosol and Oleuropein Inhibit Migration and Invasion of MDA-MB-231 Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cell via Induction of Autophagy. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2019, 19, 1983–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junkins, K.; Rodgers, M.; Phelan, S.A. Oleuropein Induces Cytotoxicity and Peroxiredoxin Over-Expression in MCF-7 Human Breast Cancer Cells. Anticancer Res. 2023, 43, 4333–4339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aktas, H.G.; Ayan, H. Oleuropein: A Potential Inhibitor for Prostate Cancer Cell Motility by Blocking Voltage-Gated Sodium Channels. Nutr. Cancer 2021, 73, 1758–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgharzade, S.; Sheikhshabani, S.H.; Ghasempour, E.; Heidari, R.; Rahmati, S.; Mohammadi, M.; Jazaeri, A.; Amini-Farsani, Z. The Effect of Oleuropein on Apoptotic Pathway Regulators in Breast Cancer Cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 886, 173509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezcan, G.; Aksoy, S.A.; Tunca, B.; Bekar, A.; Mutlu, M.; Cecener, G.; Egeli, U.; Kocaeli, H.; Demirci, H.; Taskapilioglu, M. Oleuropein Modulates Glioblastoma miRNA Pattern Different from Olea Europaea Leaf Extract. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2019, 38, 1102–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdeno, A.; Sánchez-Hidalgo, M.; Rosillo, M.A.; de la Lastra, C.A. Oleuropein, a Secoiridoid Derived from Olive Tree, Inhibits the Proliferation of Human Colorectal Cancer Cell through Downregulation of HIF-1α. Nutr. Cancer 2013, 65, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkdoğan, M.K.; Koçyiğit, A.; Güler, E.M.; Özer, F.; Demir, K.; Uğur, H. Oleuropein Exhibits Anticarcinogen Effects against Gastric Cancer Cell Lines. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 9099–9105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, M.M.; Handoussa, H.; Hussein, N.H.; Eissa, R.A.; Abdel-Aal, L.K.; El Tayebi, H.M. Oleuropin Controls miR-194/XIST/PD-L1 Loop in Triple Negative Breast Cancer: New Role of Nutri-Epigenetics in Immune-Oncology. Life Sci. 2021, 277, 119353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seçme, M.; Eroğlu, C.; Dodurga, Y.; Bağcı, G. Investigation of Anticancer Mechanism of Oleuropein via Cell Cycle and Apoptotic Pathways in SH-SY5Y Neuroblastoma Cells. Gene 2016, 585, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepporta, M.V.; Fuccelli, R.; Rosignoli, P.; Ricci, G.; Servili, M.; Fabiani, R. Oleuropein Prevents Azoxymethane-Induced Colon Crypt Dysplasia and Leukocytes DNA Damage in A/J Mice. J. Med. Food 2016, 19, 983–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulotta, S.; Corradino, R.; Celano, M.; Maiuolo, J.; D’Agostino, M.; Oliverio, M.; Procopio, A.; Filetti, S.; Russo, D. Antioxidant and Antigrowth Action of Peracetylated Oleuropein in Thyroid Cancer Cells. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2013, 51, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abtin, M.; Alivand, M.R.; Khaniani, M.S.; Bastami, M.; Zaeifizadeh, M.; Derakhshan, S.M. Simultaneous Downregulation of miR-21 and miR-155 through Oleuropein for Breast Cancer Prevention and Therapy. J. Cell Biochem. 2018, 119, 7151–7165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Li, X.; Zhu, X.; Wang, Q.; Cao, S.; Du, L. Mitochondria-Mediated Apoptosis Was Induced by Oleuropein in H1299 Cells Involving Activation of P38 MAP Kinase. J. Cell Biochem. 2019, 120, 5480–5494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Przychodzen, P.; Kuban-Jankowska, A.; Wyszkowska, R.; Barone, G.; Bosco, G.L.; Celso, F.L.; Kamm, A.; Daca, A.; Kostrzewa, T.; Gorska-Ponikowska, M. PTP1B Phosphatase as a Novel Target of Oleuropein Activity in MCF-7 Breast Cancer Model. Toxicol. Vitr. 2019, 61, 104624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansouri, N.; Alivand, M.R.; Bayat, S.; Khaniani, M.S.; Derakhshan, S.M. The Hopeful Anticancer Role of Oleuropein in Breast Cancer through Histone Deacetylase Modulation. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 17042–17049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherif, I.O.; Al-Gayyar, M.M.H. Oleuropein Potentiates Anti-Tumor Activity of Cisplatin against HepG2 through Affecting proNGF/NGF Balance. Life Sci. 2018, 198, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemi Sheikhshabani, S.; Amini-Farsani, Z.P.; Rahmati, S.; Jazaeri, A.; Mohammadi-Samani, M.; Asgharzade, S. Oleuropein Reduces Cisplatin Resistance in Ovarian Cancer by Targeting Apoptotic Pathway Regulators. Life Sci. 2021, 278, 119525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Zhu, X.; Du, L. P38 MAP Kinase Is Involved in Oleuropein-Induced Apoptosis in A549 Cells by a Mitochondrial Apoptotic Cascade. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 95, 1425–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.; Lu, Y.; Liu, B.; Ran, C.; Lei, X.; Wang, M.; Wu, S.; Yang, Y.; Wu, H. Glycolysis, a New Mechanism of Oleuropein against Liver Tumor. Phytomedicine 2023, 114, 154770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassir, A.M.; Ibrahim, I.A.A.; Md, S.; Waris, M.; Tanuja; Ain, M.R.; Ahmad, I.; Shahzad, N. Surface Functionalized Folate Targeted Oleuropein Nano-Liposomes for Prostate Tumor Targeting: Invitro and Invivo Activity. Life Sci. 2019, 220, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wang, J.; Huang, B.; Chen, A.; Li, X. Oleuropein Inhibits the Proliferation and Invasion of Glioma Cells via Suppression of the AKT Signalling Pathway. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 36, 2009–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antognelli, C.; Frosini, R.; Santolla, M.F.; Peirce, M.J.; Talesa, V.N. Oleuropein-Induced Apoptosis Is Mediated by Mitochondrial Glyoxalase 2 in NSCLC A549 Cells: A Mechanistic Inside and a Possible Novel Nonenzymatic Role for an Ancient Enzyme. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 8576961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scicchitano, S.; Vecchio, E.; Battaglia, A.M.; Oliverio, M.; Nardi, M.; Procopio, A.; Costanzo, F.; Biamonte, F.; Faniello, M.C. The Double-Edged Sword of Oleuropein in Ovarian Cancer Cells: From Antioxidant Functions to Cytotoxic Effects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini-Farsani, Z.; Hashemi Sheikhshabani, S.; Shaygan, N.; Asgharzade, S. The Impact of Oleuropein on miRNAs Regulating Cell Death Signalling Pathway in Human Cervical Cancer Cells. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2023, 71, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choupani, J.; Alivand, M.R.; Derakhshan, S.M.; Zaeifizadeh, M.; Khaniani, M.S. Oleuropein Inhibits Migration Ability through Suppression of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Synergistically Enhances Doxorubicin-Mediated Apoptosis in MCF-7 Cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 9093–9104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barzegar, F.; Zaefizadeh, M.; Yari, R.; Salehzadeh, A. Synthesis of Nano-Paramagnetic Oleuropein to Induce KRAS Over-Expression: A New Mechanism to Inhibit AGS Cancer Cells. Medicina 2019, 55, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Wu, J.; Yang, X.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Du, L. Oleuropein Induced Apoptosis in HeLa Cells via a Mitochondrial Apoptotic Cascade Associated with Activation of the C-Jun NH2-Terminal Kinase. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 125, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.Y.; Zhu, J.S.; Xie, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, J.; Jiang, S.; Shen, W.-J.; Wu, B.; Ding, T.; Wang, S.-L. Hydroxytyrosol and Oleuropein Inhibit Migration and Invasion via Induction of Autophagy in ER-Positive Breast Cancer Cell Lines (MCF7 and T47D. Nutr. Cancer 2021, 73, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Liu, X. Oleuropein Inhibits Invasion of Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck through TGF-Β1 Signalling Pathway. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahdavi Niyaki, Z.; Salehzadeh, A.; Peymani, M.; Zaefizadeh, M. Exploring the Therapeutic Potential of Fe3O4@Glu-Oleuropein Nanoparticles in Targeting KRAS Pathway-Regulating lncRNAs in Colorectal Cancer Cells. Biol. Trace Element Res. 2023, 202, 3073–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.Y.; Park, S.; Yun, J.; Jang, W.; Rethineswaran, V.K.; Van, L.T.H.; Giang, L.T.T.; Choi, J.; Lim, H.J.; Kwon, S.-M. Oleuropein Induces Apoptosis in Colorectal Tumor Spheres via Mitochondrial Fission. Mol. Cell. Toxicol. 2023, 19, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]