Abstract

Culinary education programs are generally designed to improve participants’ food and cooking skills, with or without consideration to influencing diet quality or health. No published methods exist to guide food and cooking skills’ content priorities within culinary education programs that target improved diet quality and health. To address this gap, an international team of cooking and nutrition education experts developed the Cooking Education (Cook-EdTM) matrix. International food-based dietary guidelines were reviewed to determine common food groups. A six-section matrix was drafted including skill focus points for: (1) Kitchen safety, (2) Food safety, (3) General food skills, (4) Food group specific food skills, (5) General cooking skills, (6) Food group specific cooking skills. A modified e-Delphi method with three consultation rounds was used to reach consensus on the Cook-EdTM matrix structure, skill focus points included, and their order. The final Cook-EdTM matrix includes 117 skill focus points. The matrix guides program providers in selecting the most suitable skills to consider for their programs to improve dietary and health outcomes, while considering available resources, participant needs, and sustainable nutrition principles. Users can adapt the Cook-EdTM matrix to regional food-based dietary guidelines and food cultures.

1. Introduction

Cooking and food skills proficiency, and frequent consumption of home-prepared meals, are factors associated with higher diet quality, meaning dietary patterns more closely aligned with food-based dietary guidelines (FBDG) [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Many countries have created FBDGs to define dietary patterns associated with good health that also consider local cultural and geographical factors [7]. Across these country-specific FBDGs, the core nutrition principles consistently promote a dietary pattern with a high proportion and variety of plant-based whole foods such as vegetables, fruits, and wholegrains, with the addition of meat or meat alternatives, and often dairy or dairy alternatives [8,9,10,11]. However, the international literature indicates dietary intakes of most populations are not consistent with their nation’s respective FBDGs [12].

Culinary education programs that teach food skills* and cooking skills* for domestic applications consider food agency* to varying degrees and are delivered in a range of settings across education and health sectors (* defined in Box 1) [13,14,15,16,17]. These programs commonly report positive outcomes such as improvements in diet quality [13,15,17,18,19], cooking confidence [3,13,17,18,19], and nutrition knowledge [13,17,18]. Culinary interventions that have incorporated food and cooking skills alongside gardening, physical activity, or shared meal experiences and preparation activities have demonstrated further positive outcomes [15,20]. Improving both food and cooking skill levels contribute to improvements in diet quality [3], with some evidence that food skills are a better predictor of diet quality compared with cooking skills [1,4]. Cooking skills may also play a role in preparing and consuming foods consistent with sustainable nutrition principles, as limited cooking skills for plant-based foods is reported as a barrier to reducing meat consumption [21]. Furthermore, improving food agency, which is associated with food and cooking skills, can lead to greater cooking frequency, including more frequent cooking from scratch, and higher intake of vegetables [22]. This evidence highlights the important role of culinary education programs in enhancing participants’ food agency and both food and cooking skills.

However, not all studies report effects of culinary education on target health outcomes, and only one review in the field performed meta-analysis, finding no significant association between culinary education programs and anthropometric or cardiometabolic outcomes [15]. Research on the effects of culinary education programs has been limited by a range of factors including availability of valid tools for process and outcome evaluation, and the variable quality of other study design characteristics [3,13,15,16,17,18,19]. Culinary education research to date is further limited by insufficient reporting on the method of developing programs and how content is selected and prioritised [3,23]. Wolfson et al. reported that culinary education programs typically focus on “discrete mechanical tasks” [24], with little information provided about how program content and cooking tasks were selected for inclusion, and whether improving diet quality and health were considered [24]. There is a need for culinary education program developers to provide a rationale for food and cooking skill selection [24].

Box 1. Definitions.

Cooking skills: include food preparation techniques such as chopping, mixing, and heating [25,26] that may or may not require kitchen equipment. Cooking requires perceptual skills to understand how various foods react when manipulated and conceptual skills to understand how different food preparation techniques impact on the taste, colour, and texture of foods [25].

Food skills: are a distinct set of non-cooking skills where knowledge is applied to plan nutritious meals and snacks; select, acquire, and store ingredients; and dispose of food-related waste [27,28].

Food agency: is a framework for understanding the act of cooking within the myriad of factors that influence one’s ability both to obtain cooking skills and execute those skills within the contexts of one’s social, physical, and economic environments [24,29].

The Cooking Education (Cook-EdTM) model was published to assist culinary education program providers with the complex task of designing, implementing, and evaluating programs that specifically aim to improve diet and health [30]. During the development of the Cook-EdTM model [30], a gap was identified in the availability of tools for culinary education program providers to assist them in selecting which food and cooking skills to teach within time-limited programs that aim to improve diet quality and health. Such a tool could help strengthen the evidence for food and cooking skill education programs, promote efficient use of program resources, and support development of programs to improve diet quality and health.

The current study addresses this gap through development of the Cook-EdTM matrix to guide selection of food and cooking skills for inclusion in culinary education programs that target improved participant diet quality and health. This paper describes a modified e-Delphi process used to construct the matrix. The final Cook-EdTM matrix is provided in Table 1, and this paper also discusses its potential applications as an applied tool that is highly recommended to be used within the context of applying the Cook-EdTM model [30].

Table 1.

The Cook-EdTM matrix to guide skill selection in culinary education programs that target improved diet quality and health.

2. Materials and Methods

Matrix Construction

The Cook-EdTM matrix was developed collaboratively by authors in Australia, Canada, Switzerland, United States, and the United Kingdom with consideration to the findings of the global review of FBDGs by Herforth et al. [31] to enhance its international relevance. Here the three-step process of developing the matrix and its adaptability for international use is described.

- Step 1. Developing the Structure of the Matrix

The final version of the Cook-EdTM matrix (Table 1) included 117 skill focus points spread across six sections: (1) Kitchen safety skills, (2) Food safety skills, (3) General food skills, (4) Food group specific food skills, (5) General cooking skills, (6) Food group specific cooking skills. As the key function of the matrix is to assist with improving the diet quality and health outcomes of culinary education program participants, sections four and six of the matrix include skill focus points categorised by common food groups identified in Herforth et al.’s review [31].

Herforth et al.’s review reported that over 90 countries have FBDGs developed for general populations, with 78 countries also having a “food guide” with graphic representations. However, many had caveats around the use of the FBDGs, or separate guidelines for people at a different life stage or people classified as not ‘healthy’. Across the food guides examined in the review, the most common food groups included: starchy staples, vegetables and fruits, protein sources (including meat, poultry, fish, eggs, legumes, nuts, and seeds), dairy and dairy alternatives, fats and oils, and foods and food components to limit. Therefore, columns within matrix sections four and six represent all of these food groups.

- Step 2. Identifying and Mapping Culinary-Related Skills to Include in the Matrix

Author RCA (a qualified chef, dietitian, and culinary nutrition researcher) reflected on her training and experience in kitchen and food safety, and reviewed consumer food safety guidelines [32] to draft the initial list of skill focus points in matrix sections one and two. Authors RCA and VAS (a dietitian and culinary nutrition researcher) then drafted a list of general food skill focus points, applicable to all food groups, in section three, and a list of food group-specific food skill focus points in section four based on food skills described by Fordyce-Voorham [27], McGowan et al. [3] and Lavelle et al. [33]. They also drafted a list of general cooking skill focus points in section five of the matrix and food group-specific cooking skill focus points in section six based on domestic cooking skills described by Raber et al. [34], McGowan et al. [3], Lavelle et al. [33], and Short [25,26]. In line with the purpose of the matrix, in sections three to six, only skills considered relevant to promoting diet quality and health were included. For example, healthier cooking methods such as steaming are included in the matrix, whereas less healthful methods such as deep frying are not included. Complex or specialised techniques that would not be necessary for domestic cooking e.g., sous vide, were also not included.

- Step 3. Modified e-Delphi Process

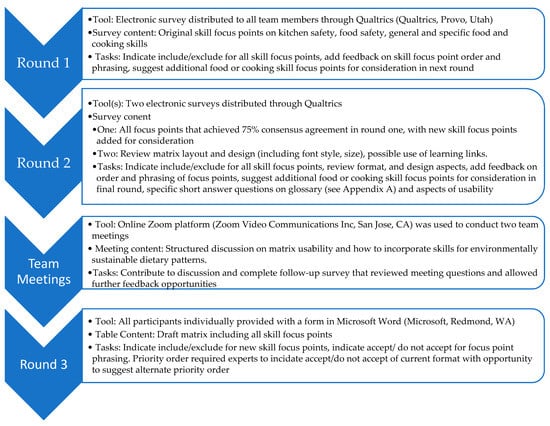

The modified e-Delphi process used in this study is shown in Figure 1. In each round, team members were asked to consider the study purpose when giving their responses. As per a traditional Delphi method, three structured feedback rounds were conducted collecting responses from all participants, blinded to each other’s responses within each round. A cut off agreement rate of 75% [35,36,37,38] was required for decisions about the matrix structure, skill focus point inclusion, order, and wording to be implemented in the matrix presented in the following round and final matrix. The modified aspect of this e-Delphi process [39] was the addition of a structured collaborative meeting in between rounds two and three that provided the opportunity for all authors to participate and share ideas (non-blinded). Several key e-Delphi studies within the field of health and nutrition [36,37,38,39] were also used to inform the modified e-Delphi methodology used in this study. Round one of the modified e-Delphi took place in September 2019. Due to the disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic, the next two rounds were postponed and completed between August and October 2021.

Figure 1.

The modified e-Delphi process used in this study.

Round one involved nine authors as participants and a fellow researcher from the University of Newcastle who could not continue to contribute due to changing work commitments (see acknowledgements). Six additional colleagues and collaborators joined the team from round two through to completion. In total, 16 team members (all are authors of this paper) completed rounds two and three. Team members have extensive experience and training in one or more of the following fields: nutrition (CEC, LC, SFV, VAS), dietetics (CEC, JS, KD, RCA, RG, SS, TJ, VAS), commercial cookery (JAW, RCA), cooking and food skill (culinary) education research and/or program development (all authors), behavioural and consumer sciences (FL, KvdH, MD, TB), public health (CEC, JAW, JS), education and curriculum review (LC, SFV, TJ), and occupational therapy (AR).

Ethical considerations: Ethical approval was not needed for this research as the participants were the authors and acted in a consultation capacity.

3. Results

The final matrix includes 117 skill focus points, including 5 kitchen safety skills, 6 food safety skills, 19 general food skills, 24 food group-specific food skills, 5 general food and cooking skills, and 58 food group specific food and cooking skills (Table 1). Working down the matrix, each column lists the order in which the skills would typically be performed when preparing food i.e., acquiring, transporting, storing, preparing, cooking, disposing, repurposing, or recycling food or its by-products. A glossary of terms used in the matrix is provided in Appendix A.

3.1. Modified e-Delphi Consensus and Refinement of Food and Cooking Skill Focus Points

Table 2 details changes in the number of skill focus points in each section of the matrix during the modified e-Delphi process. Throughout the e-Delphi process, new skill focus points were created and some skill focus points were merged. There were 13 skill focus points that did not reach the ≥75% consensus required for inclusion, and these were removed. Skill focus points did not achieve consensus on the basis of: (1) skills were deemed as beyond what is required to achieve a healthy dietary pattern, (i.e., butterfly meats or prepare dough) or (2) concepts that required a high level of existing nutrition knowledge, which were therefore out of the scope of achieving a healthy dietary pattern in the general population (e.g., understanding the functional properties of foods). Comments made by the participants during round three of the modified e-Delphi further highlighted the need to refine skill focus points to contain a verb statement constructed as a learning objective. Using Blooms Taxonomy [40], the majority of skill focus points were rephrased as a learning objective with an embedded safety, food, or cooking skill.

Table 2.

Kitchen safety, food safety, food skill, and cooking skill focus points: Selection and categorisation throughout modified e-Delphi rounds.

3.2. Modified e-Delphi Team Meetings

While the initial focus of the matrix was to identify food and cooking skills necessary to achieve a healthy dietary pattern, as discussions progressed, the importance of including food and cooking skills to support sustainable dietary patterns for human and planetary health emerged [41,42]. This resulted in existing skill focus points (Table 1) being reviewed to incorporate sustainable nutrition principles where practical and relevant, e.g., emphasising the importance of and practical ways of improving legume consumption (skill focus point 4.3.4), the concept of recycle, reuse, and reduce (3.19), and in developing processes to use the complete food source (6.1.2). These skill focus points were then reviewed in round three of the e-Delphi for inclusion or exclusion and optimal phrasing.

3.3. Using the Cook-EdTM Matrix Together with the Cook-EdTM Model to Determine Priority Food and Cooking Skills

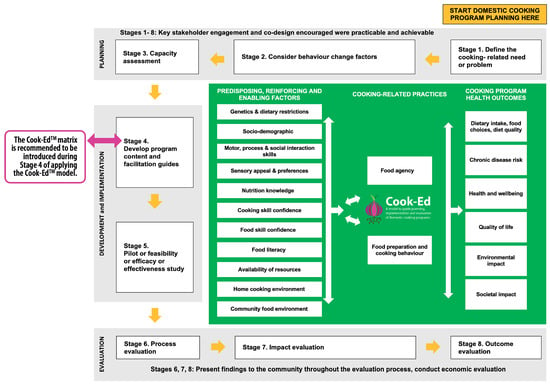

Where applicable, food and cooking skills specific to each of the common food groups are outlined in sections four and six of the matrix to ensure the necessary skills required to select, prepare, and ultimately consume a wide variety of foods from each of these groups can be achieved. While the matrix can be used on its own as an applied programming tool to guide content and learning materials, it is highly recommended that program providers use it within the context of applying the Cook-EdTM model [30] (as shown in Figure 2). The Cook-EdTM model has been created to assist program providers in tailoring culinary education programs to the needs of specific groups and guide them through all steps of program creation from conception and development to evaluation [30]. The selection and structure of culinary education program activities, such as food and cooking skill instruction, should align with the program aims and objectives as well as participant’s learning goals and needs [43,44]. Once program aims and objectives have been defined using the model (see Cook-EdTM model [30] Stage 4—“Develop program content and facilitation guides”), culinary education program providers can use the matrix (Table 1) to select and prioritise food and cooking skills to teach based on the needs and characteristics of the target audience and information gathered in program planning (see Cook-EdTM model [30] Stages 1 to 3—“Define the cooking-related need or problem”, “Consider behavior change factors”, and “Capacity assessment”).

Figure 2.

Illustration showing where to introduce the Cook-EdTM matrix when applying the Cook-EdTM model [30].

Health and safety principles should underpin food and cooking skill education programs to any audience and be a common thread integrated throughout the program. These are listed within section one and two of the Cook-EdTM matrix (Table 1). Throughout a cooking program, participants should receive appropriate information about health and safety, applicable to the demonstration kitchen and also the home setting where learned skills will be applied. This may include information on the safe handling of knives, electrical equipment, hot surfaces, slip or trip hazards in the kitchen, and appropriate kitchen attire. This is in addition to general food safety knowledge and practices to minimise microbial and other contamination of food.

Program providers without nutrition and dietetic expertise are encouraged to consult with such qualified professionals in the planning phases to ensure that program content aligns with current dietary advice and nutrition principles.

When determining skills to include, life stage, cognitive and motor skills of participants also need to be considered, e.g., culinary education programs for younger children need to teach food and cooking skills that are developmentally appropriate [45]. For people with cognitive and/or physical impairments, the demands of the skills selected need to consider an individual’s capacity to perform the skill and the availability of helpful modifications (e.g., assistive technology). Consultation with an occupational therapist is suggested to support efficient and effective skill development and/or adaptation to the environment or activity to enable participant engagement.

The Cook-EdTM matrix has been designed to support practical application of learning theory by program providers. The matrix assists with the selection of appropriate activities and can therefore support matching of both food and cooking skill development needs with the current skill levels of program participants. Evaluation data gathered may also be used to modify future programs in an iterative manner.

3.4. Consdering Appropriate Skill Level of Cook-EdTM Matrix Items

To enhance usability of the Cook-EdTM matrix, the concept of tiered learning opportunities (See Box 2) for some skill focus points was raised in the e-Delphi. For example, skills focus points could be further broken down into basic, intermediate, and advanced skills. The basic level is suitable to achieve a healthy dietary pattern, with intermediate and advanced levels offering enhanced skills to expand food and cooking skill development opportunities. This concept would allow program providers to select the level of the skill focus point that is best suited to the abilities and needs of their participants and adapt teaching as their skills increase, allowing them to build on skills previously acquired.

Box 2. Example of a tiered learning opportunity for skills focus point 6.3.1.

Original: prepare legumes, and minimally processed/whole food alternatives

Basic: identify low/no sodium tin/canned legume varieties, drain, and rinse for use

Advanced: purchase dried legumes and prepare using pressure cooker to reduce cooking time, freeze excess for use in other dishes.

4. Discussion

The Cook-EdTM matrix is a comprehensive set of safety, food, and cooking skills specific to common food groups in FBDGs. To our knowledge, the matrix is the first tool available, generated through expert consensus, to guide researchers and culinary education program providers in selecting skills to improve diet and health outcomes. The skill focus points aim to promote development of skills required to achieve healthy dietary patterns that align with FBDGs for a general population and incorporate sustainable nutrition principles. It is recommended that the Cook-EdTM matrix be used in the context of applying the Cook-EdTM model [30], as illustrated in Figure 2, so that it guides culinary education program providers to select the most suitable skill focus points based on participants’ available resources and needs.

Limitations of cooking research to date include weak study designs, a high degree of heterogeneity in outcome measures and study populations, and poor reporting of program development activities, including selection of program content [3,16,17,18,19]. When used together (Figure 2), the Cook-EdTM model [30] and the Cook-EdTM matrix (Table 1) provides researchers and culinary education program providers with resources to strengthen the evidence for culinary nutrition education programs and their influence on diet quality and health.

Consideration of other factors influencing cooking behaviour should be recognised. Healthy cooking behaviour is complex, and a myriad of personal, socioeconomic, cultural, and environmental factors can interact to influence cooking behaviour and diet quality [4,5]. Factors other than food and cooking skills, such as socio-demographic characteristics, nutrition knowledge, and psychological wellbeing are key influences on diet quality [4]. In a nationally representative sample of adults in the USA, Wolfson et al., [6] reported that cooking frequency does not influence diet quality equally across socio-economic groups, suggesting additional factors such as food provision may be more pertinent considerations for culinary nutrition education program providers when working with different groups. As recommended in the Cook-EdTM model [30], conducting an assessment of these factors before developing program content, and iteratively through program implementation, can inform education sessions focused on highest priority skills. Examples of prioritising skills in a culinary nutrition education program after assessment of the target audience can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Example of prioritising skills in a culinary nutrition education program.

Complimentary activities such as shared meal preparation, sitting down to a shared meal at the close of a practical session, and taste testing may be considered, and are frequently associated with, positive outcomes [46,47,48,49]. These can enrich culinary learning programs and enhance learning experiences by encouraging group discussion, family food preparation and meal planning discussion beyond the program and provide participants with opportunities to try new recipes and unfamiliar foods and flavours [46,48,49]. Developing an appreciation of new flavours, tastes and foods, and increased preference for fruit and vegetables can support dietary intakes that align more closely with FBDGs [46,48]. Similarly, program providers may consider other social and physical activities, such as gardening, grocery store tours, or physical activity sessions that can enhance program outcomes [15].

Incorporating sustainable nutrition principles was not an a priori aim of the matrix. However, it was an important consideration raised by participants during the e-Delphi process who recognize that culinary education researchers, program providers, and consumers all have a key role to play in achieving environmentally sustainable nutrition goals that can also be compatible with achieving higher dietary quality and favourable health outcomes [42,50]. Informed by the growing evidence on healthy diets from sustainable food systems, the e-Delphi participants acknowledged that foods consistent with sustainable nutrition principles (e.g., unprocessed plant-based food) can require greater time, effort, and skill to prepare, and they must taste good and be culturally appropriate [42,50]. With the current developments towards sustainable nutrition, the complexity of food skills to be taught in interventions is increasing substantially, and therefore sustainable nutrition principles were considered an important element to consider when developing skill focus points in the matrix.

The Cook-EdTM matrix may have other applications beyond dedicated culinary education programs. For example, many of the food skill components of the matrix could be used to guide the content of nutrition education sessions in health-related programs (e.g., in chronic disease prevention or treatment programs reviewing local nutrition recommendations for different stages of life and health needs, or investigating the nutrient profiles of each core food group, their functions, and roles), which may not always have the facilities, resources, or time allocation to practically teach cooking skills). Other examples include learning to recognise key nutrition and culinary terms, planning a menu to meet personal and household needs, and accompanying shopping/grocery list. Furthermore, with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, a transition to virtual education modes to deliver culinary education programs has been more common with programs facilitated outside the traditional kitchen space [51,52].

A strength of this study is that the authors contributing to the development of the matrix are an international team, but it needs to be highlighted that this expertise is focused across countries with similar food and cooking cultural requirements. The Cook-EdTM matrix has broad international relevance, but culinary education providers should consider the items in the matrix within the context of their own FBDGs, food and cooking culture and practices, and food availability and adapt the matrix accordingly. Additional food and cooking skills may need to be considered for the matrix to be applied to programs for other cultural groups and countries with eating patterns other than a Western diet. Similarly, additional food and cooking skills may need to be considered for non-domestic culinary education programs (e.g., commercial cookery programs), or programs where skills to improve diet quality and health are not the primary aim. A limitation of the matrix is that it is not a comprehensive list of all food and cooking skills that could be included in culinary programs

A further strength is that the design of the matrix and skill focus point selection process, via a modified e-Delphi process with three rounds, permitted independent and deep analysis to develop the final skill focus points shown in the matrix in Table 1. It is acknowledged that while the use of the Herforth et al review of FBDG provided a structured approach for linking the matrix learning objectives with dietary quality outcomes, the approach to incorporating sustainable nutrition principles was less structured [31].

5. Conclusions

The Cook-EdTM matrix presented is an evidence-based applied tool to assist in the selection and prioritisation of food and cooking skills for inclusion in culinary nutrition education programs to improve diet quality and health of participants. The matrix can be used in a variety of global settings by adapting outcomes to meet country-specific FBDGs. By detailing the process of developing the matrix and publishing it here as a freely available tool in an open access journal, cooking program providers in a variety of settings will be able to use the Cook-EdTM matrix as a program development tool. To assist with tracking the application and impact of the Cook-EdTM matrix, we encourage users to acknowledge when and how the matrix was used in their projects. When used together with the Cook-EdTM model [30], the Cook-EdTM matrix supports program providers in selecting and prioritising food and cooking skills relevant to their participant group based on program goals, nutrition recommendations for different life stages, and participant skill development needs and preferences. Further research is needed to examine the application of the matrix as an applied tool to guide program content development across a wide range of settings and target groups.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.A.S. and C.E.C.; methodology, R.C.A., T.J., C.E.C. and V.A.S.; formal analysis, T.J. and V.A.S.; investigation, R.C.A., T.J., F.L., J.A.W., A.R., T.B., M.D., K.D., K.v.d.H., S.S., J.S., L.C., R.G., S.F.-V., C.E.C. and V.A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.C.A., T.J., C.E.C. and V.A.S.; writing—review and editing, R.C.A., T.J., F.L., J.A.W., A.R., T.B., M.D., K.D., K.v.d.H., S.S., J.S., L.C., R.G., S.F.-V., V.A.S. and C.E.C.; supervision, V.A.S. and C.E.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

R.C.A. and T.J. are supported by King and Amy O’Malley Trust postgraduate scholarships. V.A.S. is supported by a Hunter Medical Research Institute grant (HMRI Grant: 1664). T.B. is supported by the Australian Research Council (Grant G1901512). J.A.W. was supported by the National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (Award #K01DK119166). CEC is supported by an NHMRC Investigator Grant (APP2009340).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as the international experts acted in a consultation capacity and all are authors, or acknowledgment is noted for contributions.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The complete dataset generated from this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Tracy Burrows (Participated in the first e-Delphi round), Grace Manning (Assisted with the matrix design and layout, Figure 2, and graphical abstract).

Conflicts of Interest

No author conflicts of interest or funding conflicts have been identified in the production of this research.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Glossary of key terms within the Cook-EdTM matrix.

Table A1.

Glossary of key terms within the Cook-EdTM matrix.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Kitchen & Food Safety | |

| Cross-contamination | Unintended movement of micro-organisms, contaminants, or allergens from between foods e.g., from raw food to cooked food [53]. |

| Microbial contamination | Unintended introduction of potentially harmful microorganisms (e.g., bacteria, mould, fungi, yeast) into food. |

| Personal hygiene | The practice of maintaining a standard of cleanliness of one’s body. Personal hygiene required for food preparation can include hand and body washing, cough and sneeze etiquette, maintenance of hair and nails, clothing. |

| Food & Nutrition Terminology | |

| Beans | A type of legume, examples include red kidney beans, black beans, borlotti beans. |

| Chickpeas | A type of legume. |

| Convenience food | Food that requires little preparation or cooking prior to consumption. Often refers to commercially prepared food such as TV dinners, ready-meals, frozen meals. |

| Cooking skills | Include a range of food preparation techniques such as chopping, mixing, and heating [25,26] that may or may not require kitchen equipment. Cooking requires perceptual skills to understand how various foods react when manipulated and conceptual skills to understand how different food preparation techniques impact on the taste, colour, and texture of foods [25]. |

| Core foods | The Australian Dietary Guidelines definition “foods that form the basis of a healthy diet, based on or developed with reference to recommended daily intakes (RDIs)” [8]. |

| Core food groups (within the Cook-EdTM matrix) | Vegetables and Fruits, Grains, Meat and Alternatives (e.g., legumes, nuts, seeds, tofu), Dairy and Alternatives. |

| Dietary fibre | Edible part of plant food that resists digestion in the small intestine and may be fermented to varying degrees in the large intestine. Includes soluble and insoluble fibre and resistant starches. |

| Dietary pattern | Refers to the variety, amount, and combination of food and drinks in the diet and the frequency with which they are habitually consumed. |

| Fats & Oils | Edible fats and oils occurring naturally in food, used in food manufacturing or cooking. May also be referred to as dietary fat. Dietary fats can be classified as saturated fat, trans fat, polyunsaturated fat, and monounsaturated fat. Edible fats and oils typically contain a combination of the different dietary fat. |

| Food-based dietary guidelines | The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations definition (also known as dietary guidelines) are intended to establish a basis for public food and nutrition, health and agricultural policies, and nutrition education programmes to foster healthy eating habits and lifestyles. They provide advice on foods, food groups, and dietary patterns to provide the required nutrients to the general public to promote overall health and prevent chronic diseases” [7]. |

| Food skills | Include meal planning, shopping, budgeting, resourcefulness, and interpreting food labels and nutrition information panels [27,33]. Lavelle et al. 2019 used psychometric testing to delineate food skills as a distinct set of non-cooking skills that enable individuals to apply knowledge about food to then prepare meals and snacks that are nutritionally appropriate within the available resources [33]. |

| Food waste | The Food and Agricultural Organization definition “the decrease in quantity or quality of food resulting from decisions and actions made by retailers, food service providers and consumers” [54]. |

| Grains | Commonly referred to as cereals or cereal grains and which are the edible seeds of specific grasses [8]. |

| Legumes | Plant in the Leguminosae (Fabeceae) family. The term legume may also be used to refer to the edible seed or pod (e.g., beans, lentils, peas, and chickpeas). Legumes come in a variety of shapes, sizes, and colours. |

| Lentils | A type of legume, examples include yellow lentils, brown lentils, red lentils. |

| Meat alternatives | Can include a range of wholefood items such as nuts, seeds, legumes and mushrooms, or minimally processed foods made from combinations of these. |

| Menu plan | A detailed list of dishes and/or recipes for a specific meal, day, or week. |

| Minimally processed | NOVA classification definition “natural foods altered by methods that include removal of inedible or unwanted parts, and also processes that include drying, crushing, grinding, powdering, fractioning, filtering, roasting, boiling, non-alcoholic fermentation, pasteurisation, chilling, freezing, placing in containers, and vacuum packaging…methods and processes … designed to preserve natural foods, to make them suitable for storage, or else to make them safe or edible or more pleasant to consume” [55]. |

| Non-core food | Foods that do not fit within the definition of ‘core foods’ (refer to core foods). |

| Non-core food group (within the Cook-EdTM matrix) | Extras (also called energy dense, nutrient poor foods, discretionary or junk). |

| Nutrient dense foods | A good source of essential macro and micronutrients. |

| Peas | A type of legume, examples include chickpeas, black-eyed peas, split peas. |

| Plant-based | A meal or dietary pattern that focuses on including mostly core foods that come from vegetable, fruit, nuts, seeds, legumes, and wholegrain groups. |

| Pulse | The edible, dried seed of a legume (e.g., beans, lentils, peas, chickpeas). The term legume is used to describe pulses within the matrix. |

| Processed products | Made by adding salt, oils, sugar or items used to prepare and/or season food. Using preservation methods such as canning, bottling, and in some cases using non-alcoholic fermentation processes [55]. |

| Shelf life | The expected length of time a food will maintain its best quality [53]. |

| Shelf stable | Does not require refrigeration. |

| Staple food | Food item(s) that are eaten frequently and form the basic components of a usual dietary pattern [53]. |

| Storage life | Time in which a food item can be safely kept in the fridge, freezer, or pantry to maintain quality and remain edible. |

| Sustainable eating | Selecting foods that are healthful for the environment and that support human health. |

| Vegan | A meal or dietary pattern that includes only foods from plant-based origin. |

| Vegetarian | A meal or dish that focuses on including mostly core foods that come from vegetable, fruit, nuts, seeds, legumes, and wholegrain foods with variation that can include some dairy, seafood, and eggs. |

| Ultra-processed | NOVA classification definition “formulations of ingredients, mostly of exclusive industrial use, made by a series of industrial processes, many require sophisticated equipment and technology…colours, flavours, emulsifiers and other additives … to make the product palatable or hyper-palatable” [55]. |

| Culinary terms | |

| Absorption method | Wholegrains like rice or quinoa, place in cool water, bring the water to the boil, simmer for a short period and then turn off heat and cover with pot lid for the remainder of the cooking time to allow grain to absorb liquid and finishing cooking for a drier, fluffy result. |

| Baking | Cook food in dry heat in an oven. |

| Blanch | To subject food to boiling water by plunging into boiling water and removing after a few seconds. |

| Blend (puree) | Using a mini blender/stick blender/bar mix or hot blender (e.g., ThermomixTM) to produce a finely mashed, smooth, or liquid consistency. |

| Boil | Cook food submerged in a boiling liquid, or food being cooked at boiling point. |

| Dice/cube | To cut even pieces in the rough shape of a dice or cube, size of dice/cube dependent upon the dish being prepared. |

| Grate | Using a vegetable/box grater, run the food item down and up or along the grater, being mindful of having the grater set securely on a cutting board or large plate/bowl and to keep fingers at a safe distance. |

| Grill | Cook food by radiant heat. May also be referred to as broiling or barbequing. |

| Pan fry | Cook food in a small amount of fat/oil. May also be referred to as shallow frying or sauté. |

| Poach | Cook food in a liquid that is below boiling point. |

| Roast | Cook food in dry heat in the presence of fat/oil. |

| Sauté | Cook food in a small amount of fat/oil. May also be referred to as pan frying or sauté or gently fry. |

| Scratch cooking | Cook food from raw or minimally processed ingredients. |

| Simmer | Cook food submerged in a liquid that is just below boiling point but bubbling. |

| Slice | To cut thin pieces either along or across the food item depending on the dish being prepared. |

| Stew/Slow cook | Cook food at a long temperature for an extended period of time in a sufficient amount of liquid; the food and cooking liquid are typically served together. |

| Steam | Cook food in steam/vapour. |

| Shallow fry | Cook food in a small amount of fat/oil. May also be referred to as pan frying or sauté. |

| Stir fry | Cook food in a small amount of oil, often at a high heat for a short period of time while stirring constantly. Stir frying is often performed in a wok (bowl shaped pan). |

| Key: the section headings and subheadings appear as bolded text | |

References

- Lavelle, F.; Bucher, T.; Dean, M.; Brown, H.M.; Rollo, M.E.; Collins, C.E. Diet quality is more strongly related to food skills rather than cooking skills confidence: Results from a national cross-sectional survey. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 77, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavelle, F.; Spence, M.; Hollywood, L.; McGowan, L.; Surgenor, D.; McCloat, A.; Mooney, E.; Caraher, M.; Raats, M.; Dean, M. Learning cooking skills at different ages: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McGowan, L.; Caraher, M.; Raats, M.; Lavelle, F.; Hollywood, L.; McDowell, D.; Spence, M.; McCloat, A.; Mooney, E.; Dean, M. Domestic cooking and food skills: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 2412–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGowan, L.; Pot, G.K.; Stephen, A.M.; Lavelle, F.; Spence, M.; Raats, M.; Hollywood, L.; McDowell, D.; McCloat, A.; Mooney, E.; et al. The influence of socio-demographic, psychological and knowledge-related variables alongside perceived cooking and food skills abilities in the prediction of diet quality in adults: A nationally representative cross-sectional study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mills, S.; White, M.; Brown, H.; Wrieden, W.; Kwasnicka, D.; Halligan, J.; Robalino, S.; Adams, J. Health and social determinants and outcomes of home cooking: A systematic review of observational studies. Appetite 2017, 111, 116–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfson, J.A.; Leung, C.W.; Richardson, C.R. More frequent cooking at home is associated with higher Healthy Eating Index-2015 score. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 2384–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-based-dietary-guidelines (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian Dietary Guidelines; National Health and Medical Research Council: Canberra, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health England. Government Dietary Recommendations; Public Health: London, UK, 2016.

- Swiss Society for Nutrition SGE. Swiss Food Pyramid. Available online: https://www.sge-ssn.ch/ich-und-du/essen-und-trinken/ausgewogen/schweizer-lebensmittelpyramide/ (accessed on 24 February 2022).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025; U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- GDP 2017 Diet Collaborators. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019, 393, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asher, R.C.; Shrewsbury, V.A.; Bucher, T.; Collins, C.E. Culinary medicine and culinary nutrition education for individuals with the capacity to influence health related behaviour change: A scoping review. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 35, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downer, S.; Berkowitz, S.A.; Harlan, T.S.; Olstad, D.L.; Mozaffarian, D. Food is medicine: Actions to integrate food and nutrition into healthcare. BMJ 2020, 369, m2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, B.; Thompson, W.G.; Almasri, J.; Wang, Z.; Lakis, S.; Prokop, L.J.; Hensrud, D.D.; Frie, K.S.; Wirtz, M.J.; Murad, A.L.; et al. The effect of culinary interventions (cooking classes) on dietary intake and behavioral change: A systematic review and evidence map. BMC Nutr. 2019, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersch, D.; Perdue, L.; Ambroz, T.; Boucher, J.L. The Impact of Cooking Classes on Food-Related Preferences, Attitudes, and Behaviors of School-Aged Children: A Systematic Review of the Evidence, 2003–2014. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2014, 11, 140267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Taylor, R.M.; Wolfson, J.A.; Lavelle, F.; Dean, M.; Frawley, J.; Hutchesson, M.J.; Collins, C.E.; Shrewsbury, V.A. Impact of preconception, pregnancy, and postpartum culinary nutrition education interventions: A systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 2020, 79, 1186–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reicks, M.; Kocher, M.; Reeder, J. Impact of Cooking and Home Food Preparation Interventions Among Adults: A Systematic Review (2011–2016). J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2018, 50, 148–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reicks, M.; Trofholz, A.C.; Stang, J.S.; Laska, M.N. Impact of Cooking and Home Food Preparation Interventions Among Adults: Outcomes and Implications for Future programs. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2014, 46, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Farmer, N.; Touchton-Leonard, K.; Ross, A. Psychosocial Benefits of Cooking Interventions: A Systematic Review. Health Educ. Behav. 2018, 45, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Neff, R.A.; Edwards, D.; Palmer, A.; Ramsing, R.; Righter, A.; Wolfson, J. Reducing meat consumption in the USA: A nationally representative survey of attitudes and behaviours. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 1835–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wolfson, J.A.; Lahne, J.; Raj, M.; Insolera, N.; Lavelle, F.; Dean, M. Food Agency in the United States: Associations with Cooking Behavior and Dietary Intake. Nutrients 2020, 12, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Begley, A.; Gallegos, D.; Vidgen, H. Effectiveness of Australian cooking skill interventions. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 973–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wolfson, J.A.; Bostic, S.; Lahne, J.; Morgan, C.; Henley, S.C.; Harvey, J.; Trubek, A. A comprehensive approach to understanding cooking behavior: Implications for research and practice. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 1147–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, F. Domestic cooking skills: What are they? J. Home Econ. Inst. Aust. 2003, 10, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Short, F. Domestic cooking practices and cooking skills: Findings from an English study. Food Serv. Technol. 2003, 3, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fordyce-Voorham, S. Identification of Essential Food Skills for Skill-based Healthful Eating Programs in Secondary Schools. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2011, 43, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fordyce-Voorham, S. Essential food skills required in a skill-based healthy eating program. J. Home Econ. Inst. Aust. 2009, 16, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Trubek, A.B.; Carabello, M.; Morgan, C.; Lahne, J. Empowered to cook: The crucial role of ‘food agency’ in making meals. Appetite 2017, 116, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asher, R.C.; Jakstas, T.; Wolfson, J.A.; Rose, A.J.; Bucher, T.; Lavelle, F.; Dean, M.; Duncanson, K.; Innes, B.; Burrows, T.; et al. Cook-Ed(TM): A Model for Planning, Implementing and Evaluating Cooking Programs to Improve Diet and Health. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herforth, A.; Arimond, M.; Álvarez-Sánchez, C.; Coates, J.; Christianson, K.; Muehlhoff, E. A Global Review of Food-Based Dietary Guidelines. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 590–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- NSW Government Food Authority. Safe Food, Clear Choices NSW Food Authority. Available online: https://www.foodauthority.nsw.gov.au/ (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Lavelle, F.; McGowan, L.; Hollywood, L.; Surgenor, D.; McCloat, A.; Mooney, E.; Caraher, M.; Raats, M.; Dean, M. The development and validation of measures to assess cooking skills and food skills. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raber, M.; Chandra, J.; Upadhyaya, M.; Schick, V.; Strong, L.L.; Durand, C.; Sharma, S. An evidence-based conceptual framework of healthy cooking. Prev. Med. Rep. 2016, 4, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dalkey, N.C. The Dephi Method: An Experimental Study of Group Opinion; Rand: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Mete, R.; Kellett, J.; Bacon, R.; Shield, A.; Murray, K. The P.O.S.T Guidelines for Nutrition Blogs: A Modified e-Delphi Study. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, 1219–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, J.; Charlton, K.; Tapsell, L.; Truby, H. Using the Delphi process to identify priorities for Dietetic research in Australia 2020–2030. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 77, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevelyan, E.G.; Robinson, P.N. Delphi methodology in health research: How to do it? Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2015, 7, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasson, F.; Keeney, S.; McKenna, H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J. Adv. Nurs. 2000, 32, 1008–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anderson, L.W.; Krathwohl, D.R. A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives; Longman: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Papier, K.; Fensom, G.K.; Knuppel, A.; Appleby, P.N.; Tong, T.Y.N.; Schmidt, J.A.; Travis, R.C.; Key, T.J.; Perez-Cornago, A. Meat consumption and risk of 25 common conditions: Outcome-wide analyses in 475,000 men and women in the UK Biobank study. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case-Smith, J.; O’Brien, J.C. Occupational Therapy for Children and Adolescents; Elsevier: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zoltan, B. Vision, Perception, and Cognition: A Manual for the Evaluation and Treatment of the Adult with Acquired Brain Injury, 4th ed.; SLACK: Thorofare, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, M.; O’Kane, C.; Issartel, J.; McCloat, A.; Mooney, E.; Gaul, D.; Wolfson, J.A.; Lavelle, F. Guidelines for designing age-appropriate cooking interventions for children: The development of evidence-based cooking skill recommendations for children, using a multidisciplinary approach. Appetite 2021, 161, 105125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham-Sabo, L.; Lohse, B. Impact of a school-based cooking curriculum for fourth-grade students on attitudes and behaviors is influenced by gender and prior cooking experience. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2014, 46, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulkerson, J.A.; Rydell, S.; Kubik, M.Y.; Lytle, L.; Boutelle, K.; Story, M.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Dudovitz, B.; Garwick, A. Healthy Home Offerings via the Mealtime Environment (HOME): Feasibility, acceptability, and outcomes of a pilot study. Obesity 2010, 18 (Suppl. 1), S69–S74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Herbert, J.; Flego, A.; Gibbs, L.; Waters, E.; Swinburn, B.; Reynolds, J.; Moodie, M. Wider impacts of a 10-week community cooking skills program—Jamie’s Ministry of Food, Australia. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- West, E.G.; Lindberg, R.; Ball, K.; McNaughton, S.A. The Role of a Food Literacy Intervention in Promoting Food Security and Food Literacy-OzHarvest’s NEST Program. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Koerber, K.; Bader, N.; Leitzmann, C. Wholesome Nutrition: An example for a sustainable diet. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2017, 76, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Poulton, G.; Antono, A. A Taste of Virtual Culinary Medicine and Lifestyle Medicine-An Online Course for Medical Students. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2022, 16, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silver, J.K.; Finkelstein, A.; Minezaki, K.; Parks, K.; Budd, M.A.; Tello, M.; Paganoni, S.; Tirosh, A.; Polak, R. The Impact of a Culinary Coaching Telemedicine Program on Home Cooking and Emotional Well-Being during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnett-Fell, B.; Stuchbury, K. Food Technology in Action, 2nd ed.; Jacaranda Press: Milton, Australia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Food Loss and Food Waste. Available online: https://www.fao.org/food-loss-and-food-waste/ (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Lawrence, M.; Costa Louzada, M.L.; Pereira Machado, P. Ultra-Processed Foods, Diet Quality, and Health Using the NOVA Classification System; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).