Effects of Nutritional Interventions on Cardiovascular Disease Health Outcomes in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.2.1. Participants

2.2.2. Concept

2.2.3. Context

2.3. Types of Studies

2.4. Search Strategy

2.5. Selection Process

2.6. Data Charting

2.7. Critical Appraisal

2.8. Synthesis of Results

3. Results

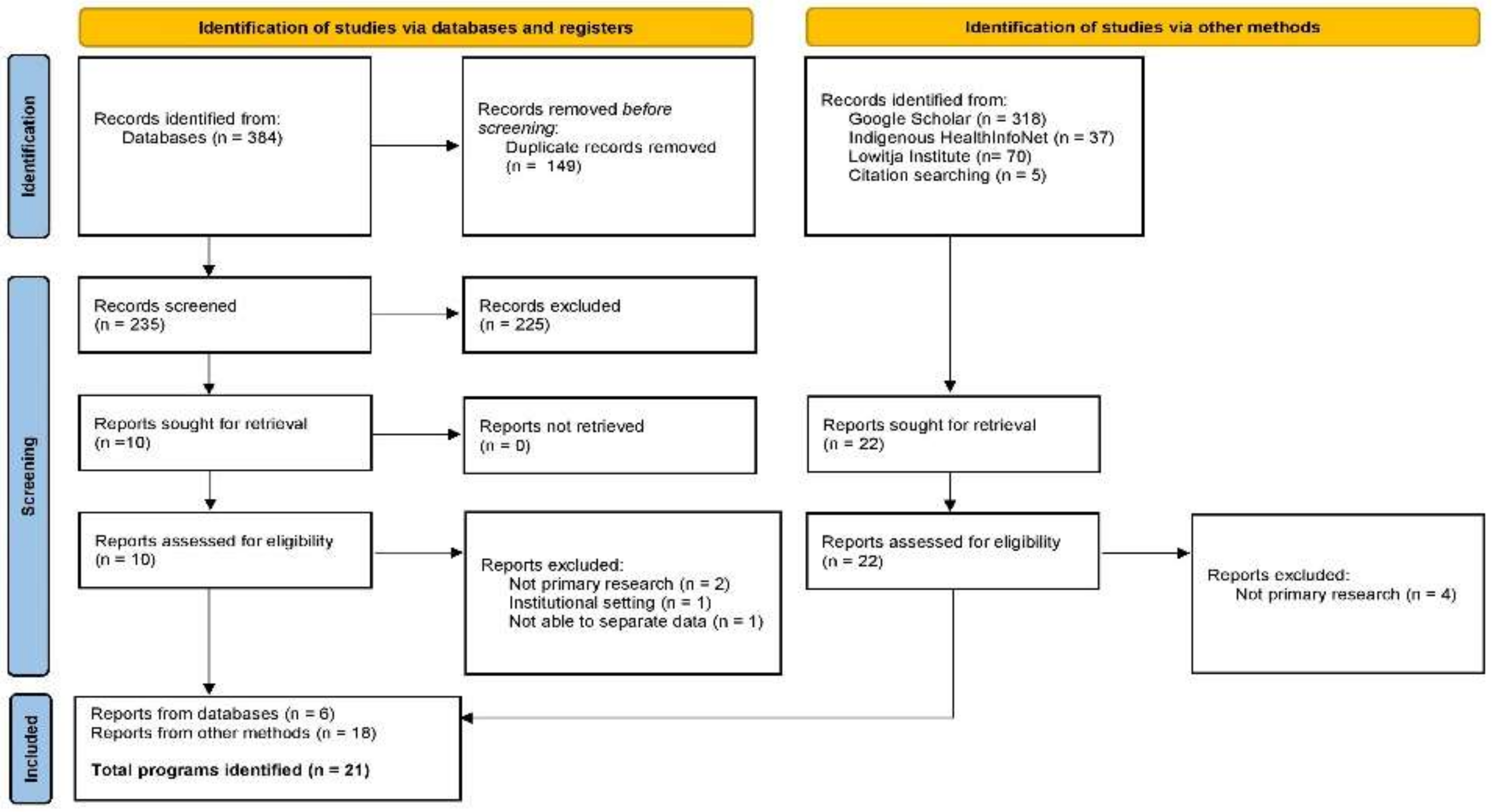

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Program Selection and Characteristics

3.3. Anthropometric Outcomes

3.4. Biochemical and/or Haematological Outcomes

3.5. Other Outcomes

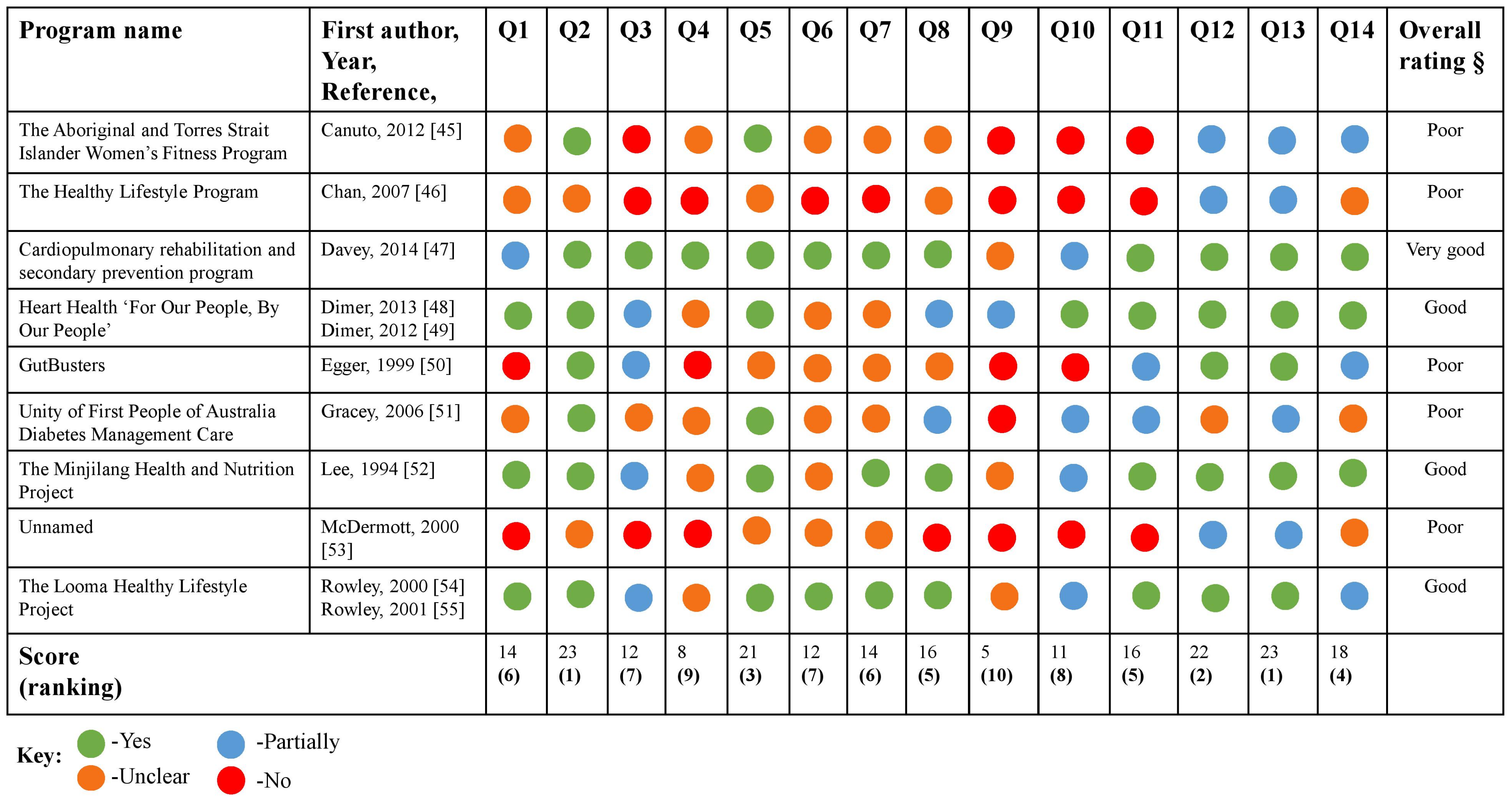

3.6. Quality Appraisal

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Australian Human Rights Commission. Bringing Them Home, Report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families. 1997. Available online: https://humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/content/pdf/social_justice/bringing_them_home_report.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Ferguson, M.; Brown, C.; Georga, C.; Miles, E.; Wilson, A.; Brimblecombe, J. Traditional food availability and consumption in remote Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory, Australia. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2017, 413, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet. Summary of Nutrition among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People. 2020. Available online: https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2020-05/apo-nid305130.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Brimblecombe, J.; Liddle, R.; O’Dea, K. Use of point-of-sale data to assess food and nutrient quality in remote stores. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 167, 1159–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brimblecombe, J.K.; Ferguson, M.M.; Liberato, S.C.; O’Dea, K. Characteristics of the community-level diet of Aboriginal people in remote northern Australia. Med. J. Aust. 2013, 1987, 380–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.J.; O’Dea, K.; Mathews, J.D. Apparent dietary intake in remote Aboriginal communities. Aust. J. Public Health 1994, 182, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandhorst, S.; Longo, V.D. Dietary Restrictions and Nutrition in the Prevention and Treatment of Cardiovascular Disease. Circ. Res. 2019, 1246, 952–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cardiovascular Disease. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/heart-stroke-vascular-diseases/cardiovascular-health-compendium (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet. Summary of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Status 2019 (Overview). 2020. Available online: https://healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au/healthinfonet/getContent.php?linkid=643680&title=Summary+of+Aboriginal+and+Torres+Strait+Islander+health+status+2019&contentid=40279_1 (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/cardiovascular-diseases/#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Trends in Cardiovascular Deaths. 2017. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/2ba74f7f-d812-4539-a006-ca39b34d8120/aihw-21213.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Coronary Heart Disease. 2020. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/coronary-heart-disease (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australian Burden of Disease Study: Impact and Causes of Illness and Death in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People 2011—Summary Report. 2016. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/burden-of-disease/illness-death-indigenous-australians-summary/contents/table-of-contents (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Australian Human Rights Commission. Social Justice Report 2005: Home. 2005. Available online: https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-social-justice/publications/social-justice-report-5 (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Australian Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Closing the Gap Report 2020. Available online: https://ctgreport.niaa.gov.au/sites/default/files/pdf/closing-the-gap-report-2020.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Wilson, S. Progressing Toward an Indigenous Research Paradigm in Canada and Australia. Can. J. Nativ. Educ. 2003, 272, 161. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Social Determinants and Indigenous Health; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, A.C.; Rosewarne, E.; Spencer, W.; McCausland, R.; Leslie, G.; Shanthosh, J.; Corby, C.; Bennett-Brook, K.; Webster, J. Indigenous Community-Led Programs to Address Food and Water Security: Protocol for a Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. What Works? A Review of Actions Addressing the Social and Economic Determinants of Indigenous Health. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/indigenous-australians/what-works-a-review-of-actions-addressing-the-social-and-economic-determinants-of-indigenous-health/contents/table-of-contents (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Australian Government Productivity Commission. Better Indigenous Policies: The Role of Evaluation. Available online: https://www.pc.gov.au/research/supporting/better-indigenous-policies (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Capwell, E.M.; Butterfoss, F.; Francisco, V.T. Why Evaluate? Health Promot. Pract. 2000, 11, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demaio, A.; Drysdale, M.; de Courten, M. Appropriate health promotion for Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities: Crucial for closing the gap. Glob. Health Promot. 2012, 192, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Government Productivity Commission. Indigenous Evaluation Strategy. Available online: https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/indigenous-evaluation#report (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Harfield, S.; Pearson, O.; Morey, K.; Kite, E.; Canuto, K.; Glover, K.; Gomersall, J.S.; Carter, D.; Davy, C.; Aromataris, E.; et al. Assessing the quality of health research from an Indigenous perspective: The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander quality appraisal tool. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2020, 20, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 81, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 1810, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harfield, S.; Pearson, O.; Morey, K.; Kite, E.; Glover, K.; Canuto, K.; Streak, G.J.; Carter, D.; Davy, C.; Aromataris, E.; et al. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Quality Appraisal Tool: Companion Document. Adelaide, Australia: South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute. 2018. Available online: https://create.sahmri.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Aboriginal-and-Torres-Strait-Islander-QAT-Companion-Document.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Laycock, A.; Walker, D.; Harrison, N.; Brands, J. Supporting Indigenous Researchers: A Practical Guide for Supervisors, Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health, Darwin. 2009. Available online: https://www.lowitja.org.au/content/Document/Lowitja-Publishing/supervisors_guide1_0.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Martin, K.; Mirraboopa, B. Ways of knowing, being and doing: A theoretical framework and methods for indigenous and indigenist research. J. Aust. Stud. 2003, 2776, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.T. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, 3rd ed.; Zed Books: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Queensland Health. 2005 Evaluation of the Healthy Weight Program; Queensland Government: Brisbane, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Life! Aboriginal Road to Good Health. 2016. Available online: https://www.lifeprogram.org.au/about-the-life-program/about-the-program/aboriginal-road-to-good-health (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Dimer, L.; Shilton, T.; Hayes, A.; Hayes, S.; Heard, M.; Turangi, G.; Hamilton, S. Listen to the Voice of the People: Culturally specific consultation and innovation in establishing an Aboriginal health program in the west Pilbara. In Proceedings of the 14th National Rural Health Conference; Heart Foundation WA: Cairns, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Advocacy Institute of Western Australia. The West Australian Indigenous Storybook. Fremantle: Public Health Advocacy Institute of Western Australia. 2018. Available online: https://www.phaiwa.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/TheWAIndigenousStorybook_9thEd_E.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Zask, A.; Rodgers, L.; Dietrich, U. Healing Program 2003–2004 Evaluation Report; NSW Helath Department, Ed.; North Coast Area Health Service: Lismore, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, S. Cooking Healthy and Physical Activity (CHAPA) Project. Chronicle 2009, 121, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Heart Foundation. Steps to Running Your Own Koori Cook Off. 2017. Available online: http://www.gdcbj.com/images/uploads/main/Heart_Foundation_-_Koori_Cook_Off_Toolkit.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Hamill, L.; Clark, K. My Heath for Life: An Innovative, Evidence-Based Preventative Health Program for Tackling Chronic Disease in Queensland. In Program Design and Delivery Overview; Queensland Government, Ed.; Diabetes Queensland: Brisbane, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wurli-Wurlinjang Health Service. Gudbinji Chronic Conditions Care. Available online: https://www.wurli.org.au/clinical-services/gudbinji-chronic-conditions-program/ (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Green, M.; Dangerfield, F. “Urimbirra Geen”—To Take Care of Your Heart. Aborig. Isl. Health Work. J. 2000, 24, 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Biles, B. ‘Strong Men’: Aboriginal Community Development of a Cardiovascular Exercise and Health Education Program. Ph.D Thesis, Charles Sturt University, Bathurst, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, D.; Longstreet, D.; Malouf, P.; Hussey, L.; Elston, J.; Panaretto, D. “Walkabout Together” A lifestyle intervention program developed for Townsville’s overweight Indigenous people. Touch PHAA Newsl. 2006, 23, 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ski, C.; Vale, M.; Thompson, D.; Jelinek, M.; Scott, I.; Le Grande, M. The Coaching Patients on Achieving Cardiovascular Health (COACH) Programme: Reducing the Treatment Gap Between Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Australians. Heart Lung Circ. 2017, 26, S336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Canuto, K.; Cargo, M.; Li, M.; D’Onise, K.; Esterman, A.; McDermott, R. Pragmatic randomised trial of a 12-week exercise and nutrition program for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women: Clinical results immediate post and 3 months follow-up. BMC Public Health 2012, 121, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, L.C.K.; Ware, R.; Kesting, J.; Marczak, M.; Good, D.; Shaw, J.T.E. Short term efficacy of a lifestyle intervention programme on cardiovascular health outcome in overweight Indigenous Australians with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus: The healthy lifestyle programme (HELP). Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2007, 751, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, M.; Moore, W.; Walters, J. Tasmanian Aborigines step up to health: Evaluation of a cardiopulmonary rehabilitation and secondary prevention program. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 141, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimer, L.; Dowling, T.; Jones, J.; Cheetham, C.; Thomas, T.; Smith, J.; McManus, A.; Maiorana, A.J. Build it and they will come: Outcomes from a successful cardiac rehabilitation program at an Aboriginal Medical Service. Aust. Health Rev. 2013, 371, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimer, L.; Jones, J.; Dowling, T.; Cheetham, C.; Maiorana, A.; Smith, J. Heart Health for Our People by Our People: A Culturally Appropriate WA CR Program. Heart Lung Circ. 2012, 2110, 651–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, G.; Fisher, G.; Piers, S.; Bedford, K.; Morseau, G.; Sabasio, S.; Taipim, B.; Bani, G.; Assan, M.; Mills, P. Abdominal obesity reduction in indigenous men. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 1999, 236, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gracey, M.; Bridge, E.; Martin, D.; Jones, T.; Spargo, R.M.; Shephard, M.; Davis, E.A. An Aboriginal-driven program to prevent, control and manage nutrition-related “lifestyle” diseases including diabetes. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 152, 178–188. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, A.J.; Bailey, A.P.; Yarmirr, D.; O’Dea, K.; Mathews, J.D. Survival tucker: Improved diet and health indicators in an aboriginal community. Aust. J. Public Health 1994, 183, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, R.; Rowley, K.G.; Lee, A.J.; Knight, S.; O’Dea, K. Increase in prevalence of obesity and diabetes and decrease in plasma cholesterol in a central Australian aboriginal community. Med. J. Aust. 2000, 17210, 480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, K.G.; Daniel, M.; Skinner, K.; Skinner, M.; White, G.A.; O’Dea, K. Effectiveness of a community-directed “healthy lifestyle” program in a remote Australian aboriginal community. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2000, 242, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, K.G.; Su, Q.; Cincotta, M.; Skinner, M.; Skinner, K.; Pindan, B.; White, G.A.; O’Dea, K. Improvements in circulating cholesterol, antioxidants, and homocysteine after dietary intervention in an Australian Aboriginal community. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 744, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.-C.; Lee, C.-C.; Liu, S.-C.; Tseng, P.-J.; Chien, K.-L. Combined healthy lifestyle factors are more beneficial in reducing cardiovascular disease in younger adults: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, W.J.; Kang, S.J. Interventions to Reduce the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease among Workers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 177, 2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbuzi, V.; Fulbrook, P.; Jessup, M. Effectiveness of programs to promote cardiovascular health of Indigenous Australians: A systematic review. Int. J. Equity Health 2018, 17, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G.F.; Audrey, S.; Barker, M.; Bond, L.; Bonell, C.; Hardeman, W.; Moore, L.; O’Cathain, A.; Tinati, T.; Wight, D.; et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ Br. Med. J. 2015, 350, h1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marmot, M.P.; Friel, S.P.; Bell, R.P.; Houweling, T.A.J.P.; Taylor, S.P. Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet 2008, 3729650, 1661–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, K.M.; Abbott, G.; Bowe, S.J.; Ward, J.; Milte, C.; McNaughton, S.A. Diet quality indices, genetic risk and risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality: A longitudinal analysis of 77 004 UK Biobank participants. BMJ Open 2021, 114, e045362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Program Name, Reference, Year | Aims | Intervention Summary | Timeframe (Duration/Time to Follow-up) | Target Population | Setting | Anthropometric Measurements | Biochemical and/or Haematological Biomarkers | Other Outcomes | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Living Strong (formerly known as the Healthy Weight Program) [32] 2005 | To help Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples maintain a healthy weight and prevent lifestyle diseases | Total participants (n = 432) Follow up (n = 34) QLD government-initiated weight management and healthy lifestyle program designed to teach lifestyle skills relating to nutrition, PA and self-esteem Delivery: In-person and group-based Education: Healthy weight and weight loss; behaviour change; low fat cooking; budgeting for healthy meals; shopping tour; self-esteem; benefits of exercise; diabetes awareness | 3 months/ 0, 8, 12 wks (baseline, mid, post program) | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults | QLD (Program held across 8 communities; Chermside, Rockhampton, Mount Morgan, Blackwater, Gehgre, Woorabinda, Toowoomba, Wynnum) | ↓ Weight (in >50% of participants) ↓ WC (in >50% of participants) | N/A | ↑ Proportion of participants eating at least two daily servings of fruit ↑ Proportion of participants eating five daily servings of vegetables ↑ Reading NIP ↑ Water ↑ Using reduced fat foods ↑ PA (planned and incidental) | Active |

| Life! Aboriginal Road to Good Health [33] 2016 | To reduce the risk of developing T2DM and CVD in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples | Total participants (unspecified) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander healthy lifestyle program, supported by the Victorian government, within the “Life! Program”. The program is run by Aboriginal health workers and Aboriginal health services and included dietitians, diabetes educators and personal trainers. Culturally appropriate supporting resources were used to assist in topic delivery including facilitator manuals, participant workbook material including recipes and healthy eating and exercise books/posters Delivery: six sessions delivered in-person as a group course (telephone health coaching service or the group course via zoom available during the coronavirus pandemic) Education: healthy eating; maintaining a healthy weight; food label reading; purchasing healthy/cost effective foods; benefits of exercise; diabetes prevention; cessation of smoking | 6 wks/nil | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals, families and community groups. Eligibility >18 and diagnosed with one or more of the following: (heart disease or stroke, gestational diabetes, high cholesterol, BP, BGL, polycystic ovarian syndrome) | VIC (Melbourne) | N/A | N/A | ↑ Engagement Feedback (the flexible, fun, family-friendly approach in addition to a passionate facilitator were key factors to its success) | Active |

| Pilbara Aboriginal Heart Health Program [34,35] 2017/2018 | To provide comprehensive, coordinated, integrated and culturally appropriate health education services to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples | Total participants (unspecified) Program developed in collaboration with the Heart Foundation and Karratha Central Healthcare. Incorporates culturally relevant strategies including yarning to support positive behaviour change. The program is committed to the following principles: community control, holistic approach, cultural safety, equality, reciprocity and inclusion, best practice, building community capacity, accountability, sustainability. Delivery: group-based, in-person activities and meetings tailored to each community. Education: healthy eating; heart health; accessing health services; benefits of exercise | Unspecified | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples | WA (3 communities in the Pilbara region: Karratha, Onslow and Roebourne) | N/A | N/A | ↑ Self-esteem ↑ Knowledge (healthy eating) ↑ PA ↑ CVD health knowledge | Active |

| Healthy Eating Activities and Lifestyles for Indigenous Groups (HEALInG) [36] 2007 | To provide realistic and practical information on healthy eating and lifestyle activities to support weight loss | Total participants (n = 11) Goonellabah (n = 3) GurgunBulahnggelah (n = 6 to 8) Program adapted from QLD Health’s Healthy Weight Program. Delivery: in-person and group-based. One hr exercise class, followed by an education session on healthy eating and/or lifestyle topics Education: dietary guidelines; food groups; serving sizes; reducing fat, salt and sugar intake; food budgeting and label reading; benefits of exercise. Information was also provided on CVD, diabetes and stroke prevention | 10 wks/ 0,10 wks | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women | NSW (Northern Rivers region including Goonellabah and GurgunBulahnggelah) | N/A | N/A | ↑ Knowledge and skills relating to: cooking healthy and budget conscious meals; achieving daily PA targets; food label reading; fats, sugar, and salt content within foods; chronic diseases; and the positive effects of diet and exercise | Completed |

| Cooking Healthy and Physical Activity (CHAPA) Project [37] 2009 | To encourage active self-management for people with T2DM and/or heart disease | Total participants (unspecified) Group 1 (n = 15) Program is one of four programs from Healthy Active Australia “Community and School Grants Program”. Multidisciplinary team including dietitians, exercise physiologists and psychologists. Delivery: in-person and group-based Education: goal setting; healthy eating and cooking; benefits PA | 10 wks/nil (four groups, over 12 months) | People with heart disease and/or T2DM | NT (greater Darwin region) | N/A | N/A | Anecdotal remarks were made on improvements in health, fitness, weight, BP and functional strength | Completed |

| Koori Cook Off Program [38] 2017 | To improve heart health outcomes through nutrition education and increase confidence, knowledge and skills of healthy cooking and eating | Total participants (unspecified) A cooking challenge program developed by and for Aboriginal communities in collaboration with the Heart Foundation. Using healthy foods, groups cook healthy meals for a panel of judges (local Elders) Delivery: in-person and group-based, four teams, each with four people Education: culinary skills; creating healthy meals using basic ingredients; portion sizes; practical ways to increase FV consumption; healthier oils; reducing salt; choosing mainly water | nil/nil | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples | NSW (Communities throughout the Illawarra and Shoalhaven regions) | N/A | N/A | Anecdotal feedback suggested that the program was popular with the community | Active |

| My Health for Life (MH4L) [39] 2016 | To decrease participants’ risk of developing conditions such as T2DM, heart disease, stroke, high cholesterol and high BP | Total participants (unspecified) Initiated by QLD government, now run by a NGO partnership including Diabetes QLD, National Heart Foundation, Stroke Foundation and others. Participants must complete a health check to participate. A culturally appropriate tailored version of the program was available for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples Delivery: six-session program delivered either remotely via telephone or group-based and in-person. This followed by a six-month online maintenance program Education: healthy eating; benefits of exercise; weight management; consuming safe levels of alcohol; smoking cessation | 6 months/nil | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples at risk of developing T2DM, heart disease, stroke, high cholesterol and high BP | QLD (statewide) | N/A | N/A | N/A | Active |

| Gudbinji Chronic Disease Program [40] N/A | To improve heart health and heart health risk factors | Total participants (unspecified) A one-day heart health focused program that is part of a larger 10 wk chronic disease (including CVD) program Delivery: In-person Education: Healthy eating and cooking with dietitians; benefits of exercise | 1 day/nil | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples | NT (Katherine, Wurli-Wurlinjang Aboriginal Health Service) | N/A | N/A | N/A | Active |

| Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heart Care Project “Urimbirra Geen” [41] 2000 | To improve heart disease risk factors and other factors affecting the health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders | Total participants (unspecified) This multi-faceted project is a partnership between government and NGOs addressing heart health issues within the local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community Delivery: Through involvement with a variety of different community initiatives including: youth athletics carnival; “Yandarra”—a healthy lifestyle partnership project; Wagga Wagga Elders Physical Activity Group; culturally appropriate educational materials distributed by the Greater Murray Area Health Service Education: depend on the community initiative involved but was centred around healthy eating; packing healthy lunches and snacks; PA; tobacco and alcohol | N/A | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples | NSW (Wagga Wagga) | N/A | N/A | N/A | Unclear |

| Strong Men [42] 2020 | To decrease CVD risk factors in Aboriginal men aged 35–80 yrs and understand the experience of Aboriginal men who participated in the exercise and health education program | Total participants (n = 10) A short program focused on cardiovascular exercise and health education. Program was developed with local Aboriginal community input Delivery: in-person and group-based Education: nutrition and healthy eating; social and emotional well-being; PA | 10 wks/10 wks | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men (35–80 yrs) | NSW (Albury Wodonga) | ↓ WC **‡ ∆ 123.5 cm (24.9) to 114.5 cm (17.5) ↓ Weight *‡ ∆ 106.7 kg (37.7) to 104.6 kg (33.0) ↓ BMI | ↓ TC ↓ HDL-C *‡ ∆ 1.25 mmol/L (0.45) to 1.10 mmol/L (0.27) ↓ LDL-C ↓ TG No change HbA1c ↓ BGL **‡ ∆ 5.58 mmol/L (3.45) to 5.25 mmol/L (1.67) ↓ SBP **‡ ∆ 140 mmHg (19.0) to 132 mmHg (19.2) ↑DBP ‡ | ↑ 6 min walk test **‡ ∆ 360 m (40) to 400 m (75) ↑ Squats/1 min **‡ ∆ 29.0 (7.7) to 45.5 (12.2) ↑ Incline push ups/1 min **‡ ∆ 28.5 (5.5) to 39.5 (8.0) ↑ Shoulder press/1 min **‡ ∆ 44.5 (22.0) to 68.5 (30.7) ↑ Step ups/1 min **‡ ∆ 24.0 (9.5) to 36.5 (13.0) | Completed |

| Walkabout Together [43] 2006 | To address high community levels of chronic disease (including hypertension and diabetes) via a nutrition and PA lifestyle program | Total participants (n = 150) Follow up (n = 126) Townsville Aboriginal and Islanders Health Services developed this lifestyle modification program to reduce impact of chronic disease in the community Delivery: in-person and group-based weekly support sessions. Patients had access to GPs, dietitians and health workers for regular check-ups. Regular recreational walks were encouraged Education: unspecified | 1 yr/1 yr | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (overweight; BMI > 25 kg/m2) | QLD (Townsville Aboriginal and Islanders Health Service) | ↓ Weight ↓ WC | ↓ BGL ↓ TC ↑ HDL-C ↓ TG ↓ DBP No change to SBP and HbA1c | Food/Nutrient intake: ↑ Participants consuming the recommended food group serves from AGHE PA: ↑ Participants performing moderate and vigorous PA >2 two days/wk ↑ Steps Correlation* between daily steps and moderate and vigorous PA ↓ Sedentary behaviours Other: ↑ Wellbeing * | Completed |

| Coaching Patients on Achieving Cardiovascular Health (COACH) Program [44] 2017 | To reduce CVD risk | Total participants (n = 492) (included both Indigenous and non-Indigenous) distributed through the QLD Health Contact Centre, this program is the first standardized coaching program targeting CVD risk factors via telephone and mail outs Delivery: five coaching sessions by trained health professionals over 6 months, in form of telehealth (phone calls) and mail outs Education: lifestyle modification; goal setting; disease management | 6 months/unspecified | Patients with CHD and/or T2DM | Australia wide | N/A | ↓ TC *** ↓ LDL-C * | ↑ PA *** | Active |

| Program Name, Reference, Year | Aims | Intervention Summary | Timeframe (Duration/Time to Follow-up) | Target Population | Setting | Anthropometric Measurements | Biochemical and/or Haematological Biomarkers | Other Outcomes | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women’s Fitness Program [45] 2012 | To evaluate the impact of the program on WC, weight and biomarkers from baseline (T1) to immediately post program (T2) and to assess if outcomes were maintained at 3 month follow-up (T3) | Randomised Controlled Trial, Total participants (n = 100) Significant lost to follow up and missing data. An exercise and nutrition program. The cohort was split between an active group and a waitlisted group (control) Delivery: in-person and group-based. Two one-hr cardiovascular and resistance training classes per wk and four nutrition education workshops Education: food label reading; recipe modification; cooking demonstration | 12 wks/ 12 wks (T2) and 3 months (T3) | Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women aged 18 to 64 yrs Participants must have had a WC >80 cm Pregnant or breastfeeding (excluded) | SA (Adelaide) | Association between active group and control, adjusting for all potential confounders and T2DM (T2) ↓ Weight *β ∆1.65 kg ↓ BMI *β ∆ 0.66 kg/m2 ↓ Waist and hip measurements (T3) ↓ Weight *β ∆ 2.50 kg ↓ BMI **β ∆ 1.03 kg/m2 ↓ Waist and hip measurements | Association between active group and control, adjusting for all potential confounders and T2DM (T2) ↓ SBP ↓ DBP ↓ HbA1c ↓Glucose ↓Insulin TC (no change) ↑TG ↑ LDL-C ↓ HDL-C ↓ CRP (T3) ↓ SBP ↓ DBP ↓ HbA1c ↓Glucose ↑Insulin ↓ TC ↓ TG ↑LDL-C ↓ HDL-C ↓ CRP | N/A | Completed |

| The Healthy Lifestyle Programme (HELP) [46] 2007 | To determine the effectiveness of lifestyle intervention on improving diabetes and cardiovascular risk factors | Cohort study, total participants (n = 101) Follow up (n = 80) A community-based, culturally appropriate, lifestyle intervention to improve cardiovascular risk factors. Included: Self-monitoring of BGLs and PA Delivery: unspecified Education: unspecified | 2 yrs/6 months (during intervention) | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, overweight, >20 yrs, ±T2DM | QLD (North Stradbroke Island and Redland Bay) | ↓ WC **† ∆3.1 cm ↓ BMI ↓WHR | ↓ DBP **† ∆ 4.6 mmHg ↓SBP ↓ MABP *† ∆ 4.2 mmHg ↓ TC **† ∆ 0.26 mmol/L ↓ TG *† ∆ 0.18 mmol/L ↓ HDL-C ***† ∆ 0.09 mmol/L ↓LDL-C ↑ HbA1c *** † ∆ 0.31% ↑ Fasting BGL | ↑ Steps | Completed |

| Cardiopulmonary rehabilitation and secondary prevention program [47] 2014 | To improve health outcomes of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders with diagnosed CVD and/or associated risk factors | Cohort study, total participants (n = 92) Follow up (n = 72) Cardio-pulmonary programs (n = 13) developed and delivered under an Aboriginal community-controlled health service. It had two components: education and exercise Delivery: in-person and group-based. Two one-hr exercises and one one-hr education session per wk Education: CVD; benefits of exercise; shopping; cooking and eating healthy food; medication usage; risks of smoking; stress reduction techniques | 8 wks/ 8 wks | Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islanders with a diagnosis of COPD, IHD or CHF, and at least two cardiovascular risk factors (smoking, obesity, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia) | TAS (Launceston and Hobart) | Participants with risk factors ↓ Weight ∆ 0.8 kg (ES = 0.04) ↓ BMI ∆ 0.3 kg/m2 (ES = 0.03) ↓ WC ∆ 3.0 cm (ES = 0.17) | N/A | Participants with risk factors ↑ Six-min walk distance † ∆ 43.6 m (ES = 0.10) ↓ Dyspnoea ↓ Fatigue ↑ Quality of life | Completed |

| Heart Health—For Our People, by Our People [48,49] 2013/2012 | To evaluate the uptake and effects on lifestyle, and cardiovascular risk factors, of cardiac rehabilitation at an AMS | Cross sectional study, total participants (n = 120), 18 months since program commencement A culturally appropriate cardiac rehabilitation program focused on improving cardiovascular health through nutrition, PA and lifestyle Delivery: in-person and group-based. Weekly education sessions utilising yarning and PA Education: healthy eating; heart health risk factor modification; diabetes; management of medications; healthy tucker; healthy weight; oral health; stress and emotion management; PA | Unspecified/8 wk snapshot data of 28 participants (20 female) | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with or at risk of chronic disease | WA (Derbarl Yerrigan Health Service, Perth) | ↓ BMI *† ∆ 34.0 kg/m2 (5.1) to 33.3 kg/m2 (5.2) ↓ WC **† ∆ 113 cm (14) to 109 cm (13) ↓ Weight | ↓ SBP *† ∆ 135 mmHg (20) to 120 mmHg (16) ↓ DBP *† ∆ 78 mmHg (12) to 72 mmHg (5) | ↑ 6 min walk distance ** ∆ 296 m (115) to 345 m (135) | Active |

| Gut Busters [50] 1999 | To promote long-term lifestyle changes and enable community ownership and continuation | Cohort study, total participants (n = 57) Follow-up (n = 47) An NSW Health program developed in 1991, adapted for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men. A “waist loss” program that made sustainable lifestyle changes across the community through the recruitment of Indigenous male leaders Delivery: in-person and group-based Education: reducing fat intake; increasing dietary fibre; increasing daily movement; changing ‘obesogenic’ habits | 12 months/2, 6 and 12 months (during intervention) | Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander men | NT (4 island groups in the Torres Strait region of Northern Australia) | ↓ Weight ***† ∆ 107 kg (18.2) to 103 kg (18.1) ↓ WC ***† ∆ 118 cm (13.6) to 114 cm (13.9) ↓ BMI ***† ∆ 34.7 kg/m2 (5.4) to 33.6 kg/m2 (5.4) ↓ WHR ***† ∆ 1.05 (0.05) to 0.98 (0.05) ↓ Fat mass ***† ∆ 36.7 kg (12.2) to 32.8 kg (12.5) ↓ Body Fat (%) ∆ 34 (4.9) to 32 (5.6) ***† | N/A | N/A | Unclear (may still be active in the community) |

| Unity of First People of Australia Diabetes Management Care Program (UFPA) [51] 2006 | To prevent chronic diseases, including CVD, T2DM and obesity | Cohort Study, total participants (unspecified) Population of sum for the four communities (n = 1350) An Aboriginal-run screening and intervention program designed to increase awareness of chronic disease; promote healthier living; increase screening; advocate for early treatment; increase medication compliance; reduce further health complications Delivery: community-based and in-person. Group and individual level intervention. Education: diabetes education; PA; diet and nutrition; lifestyle; self-management; weight reduction; health education | Unspecified, “many months to 3 yrs in the different communities”/Unspecified | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders of all ages | WA (4 communities Gibson Desert in Pilbara, Fitzroy Valley West Kimberley, and two communities inEast Kimberley) | Findings reported for one Kimberly community (better findings reported for diabetic rather than non-diabetic persons): ↓ Weight ↓ BMI ↓ WC | Findings reported for one Kimberly community: ↓ HbA1c ↓ TC ↓ LDL-C ↑ HDL-C | ↑ PA | Completed |

| The Minjilang Health and Nutrition Project [52] 1994 | To measure nutritional status of adults at Minjilang and describe community dietary intake, and use data for planning, implementing, and monitoring and evaluation of intervention | Cohort study, total participants Minjilang (n = 154) Control community (n = 310) (during intervention period) Program included health screening (voluntary), intervention and evaluation against a comparison community Delivery: community-delivered via Minjilang Clinic Education: encouraged FV intake and lean meats similar to traditional bush foods; discourage T/A and sugary foods; exercise was encouraged | 12 months/3, 6, 9, 12 (during intervention) | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders adults | NT (Minjilang, Croker Island) | ↓ BMI *** | ↓ DBP *** ↓ SBP *** ↓ TC ***† ∆12.3% ↓ Fasting TG (nondiabetics only) ↑ RBC ↑ Serum folate ↑ Serum B6 ↑ Plasma B-carotene ↑ Plasma ascorbic acid | ↑ FV ↓ Sugar ↑ low sugar drinks ↓ T/A food ↑ Wholemeal bread ↓ %E from total and saturated fat MUFA and PUFA oils replaced other oils ↓ %E from sugars ↑ Dietary density of ascorbic acid, b-carotene, thiamine, folate, calcium ↑ Fibre | Unclear (may still be active in the community) |

| Unnamed [53] 2000 | To raise community awareness of diabetes and CVD | Total participants (1987 n = 348, 1991 n = 331, 1995 n = 305) Community-based nutrition awareness healthy lifestyle program Delivery: unspecified Education: diabetes awareness; healthy food-buying | 2 yrs/3,8 yrs | Aboriginal community members > 15 yrs | Central Australia | At 8 yr follow up ↑ Obesity (OR: 1.84) Women (change over time) ↑ BMI ***† ↑ WC ***† | 8 yr follow-up ↑ Dislipidemia (OR: 4.54) ↓ HC (OR: 0.29) Men (change over time) ↓ HDL-C ***† ↓ TC *† ↑TG **† Women (change over time) ↓ HDL-C ***† ↓ TC ***† ↑ TG ***† | Food/Nutrient intake: ↓ % E from fat and saturated fat ↓ % E from sugar ↑ Complex CHO intake Store turnover method: ↓ FV ↓ Sugar ↑ Flour and bread | Completed |

| The Looma Healthy Lifestyle Project [54,55] 2000/2001 | To reduce CHD through dietary modification | Cross-sectional study, total participants (n = 49) (32 intervention, 17 control) Cross-sectional community samples (baseline n = 200, two-yrs n = 185, four yrs n = 132) Delivery: in-person and group-based. Education: healthy cooking techniques; sources of refined CHO; importance of FV; store tours; benefits of exercise | 2 yrs/ 2, 6, 12, 18, 24 months (during intervention) | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders at high risk of developing diabetes and CHD | WA (Looma Aboriginal community, in the remote Kimberley region) | ↓ BMI *** at 6 months | ↓ Fasting plasma glucose *† but returned to baseline at 12 months ∆ 0.9 mmol/L ↓ 2-hr plasma glucose **† but returned to baseline at 12 months ∆ 1.6 mmol/L ↓ Fasting insulin **† at 18 months Cross-sectional survey data between 1993–1997, on wider community: ↓ TC (15–34 yrs) ↓ HC *** (age-adjusted prevalence at baseline (31%), 2 (21%) and 4-yrs (15%) ↑ Plasma α-tocopherol ↑ Plasma lutein and zeaxanthin ↑ cryptoxanthin ↑ β-carotene | ↓ Total and Saturated fat ↑ FV ↑PA | Unclear (may still be active in the community) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Porykali, B.; Davies, A.; Brooks, C.; Melville, H.; Allman-Farinelli, M.; Coombes, J. Effects of Nutritional Interventions on Cardiovascular Disease Health Outcomes in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4084. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13114084

Porykali B, Davies A, Brooks C, Melville H, Allman-Farinelli M, Coombes J. Effects of Nutritional Interventions on Cardiovascular Disease Health Outcomes in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: A Scoping Review. Nutrients. 2021; 13(11):4084. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13114084

Chicago/Turabian StylePorykali, Bobby, Alyse Davies, Cassandra Brooks, Hannah Melville, Margaret Allman-Farinelli, and Julieann Coombes. 2021. "Effects of Nutritional Interventions on Cardiovascular Disease Health Outcomes in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: A Scoping Review" Nutrients 13, no. 11: 4084. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13114084

APA StylePorykali, B., Davies, A., Brooks, C., Melville, H., Allman-Farinelli, M., & Coombes, J. (2021). Effects of Nutritional Interventions on Cardiovascular Disease Health Outcomes in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: A Scoping Review. Nutrients, 13(11), 4084. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13114084