Abstract

Patients with Behçet’s disease often use complementary and alternative medicine for treating their symptoms, and herbal medicine is one of the options. This systematic review provides updated clinical evidence of the effectiveness of herbal medicine for the treatment of Behçet’s disease (BD). We searched eleven electronic databases from inception to March 2020. All randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi-RCTs of BD treatment with herbal medicine decoctions were included. We used the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions to assess the risk of bias and the grading of recommendations assessment, development and evaluation (GRADE) approach to assess the certainty of evidence (CoE). Albatross plot was also used to present the direction of effect observed. Eight studies were included. The risk of bias was unclear or low. The methodological quality was low or very low. Seven RCTs showed significant effects of herbal medicine on the total response rate (Risk ratio, RR 1.26, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.45, seven studies, very low CoE). Four RCTs showed favorable effects of herbal medicine on the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) level compared with drug therapy. Herbal medicine favorably affected the ESR (MD −5.56, 95% CI −9.99 to −1.12, p = 0.01, I2 = 96%, five studies, very low CoE). However, herbal medicine did not have a superior effect on CRP. Two RCTs reported that herbal medicine significantly decreased the recurrence rate after three months of follow-up (RR 0.23, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.63, two studies, low CoE). Our findings suggest that herbal medicine is effective in treating BD. However, the included studies had a poor methodological quality and some limitations. Well-designed clinical trials with large sample sizes are needed.

1. Introduction

Behçet’s disease (BD), also called Behçet’s syndrome or Silk Road disease, is a multisystem chronic inflammatory disease characterized by painful mouth sores, genital ulcers, eye inflammation, and arthritis [1,2]. It frequently occurs in Turkey, Iran, Japan, and Korea. The incidence is relatively higher in East Asia than in the Mediterranean region (1–10 per 10,000 population). The incidence of BD is significantly elevated among young men [2,3].

Current BD therapies include colchicine, corticosteroids, immunosuppressive drugs, and antitumor necrosis factor-alpha (anti-TNF-alpha) agents. Western medicines help reduce symptoms and prevent complications. However, long-term treatment for BD can cause several adverse drug reactions, including osteoporosis, weight gain, fatigue, increased appetite, and increased blood pressure [4,5]. Therefore, patients are interested in complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), especially herbal medicine [6].

Clinical research studies have shown that herbal medicine may relieve BD symptoms [7]. Herbal medicine improves symptoms through cytokine modulation and significantly reduces the production of TNF-alpha, interleukin-1-beta (IL-1-beta), and interferon-gamma (INF-gamma) [8,9,10,11]. That is, herbal medicine enhances immunity by removing impurities from the body and activating blood circulation.

Recently, three systematic reviews were published on this topic [12,13,14]. Three reviews showed that herbal medicine was significantly better than drug therapy for the improvement of BD according to the clinical treatment effect, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C-reactive protein (CRP) level. However, the three previous reviews did not publish a transparent protocol, and they reported insufficient details pertaining to the included studies. Moreover, they are outdated.

This review aims to provide updated evidence of the efficacy and safety of herbal medicine for the treatment of BD.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Registration and Protocol Information

This review was registered at PROSPERO 2018 CRD4201808493 (Available from http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42018085493), and the protocol was published [15].

2.2. Data Sources

We searched for RCTs reporting the effects of herbal medicine on BD published since the inception of the databases until March 2020. We searched 11 electronic databases: PubMed, EMBASE, and CENTRAL; three Chinese databases (CNKI, Wanfang, and VIP); and five Korean databases (OASIS, DBpia, Research Information Service System (RISS), the Korean Studies Information Service System (KISS), and Korea Med). We restricted our searches to studies published in English, Chinese, and Korean. The search terms included “BD” OR “Behçet’s syndrome” OR “Behçet’s disease” AND “herbal medicine” OR “herb”. The detailed search terms are shown in Supplement 1.

2.3. Study Selection

2.3.1. Types of Studies

All randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi-RCTs comparing herbal medicine with Drug therapy were included. Master’s or doctoral theses were included. Case reports, case series, uncontrolled trials, and reviews were excluded.

2.3.2. Types of Participants

Participants of both sexes and any age with clinically diagnosed BD were included. The studies had to meet the following criteria: the International Study Group (ISG) criteria [16]; the International Criteria for BD (ICBD) [17]; and the Standard for Disease in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) diagnostic criteria.

2.3.3. Types of Interventions and Comparison

The intervention group received only herbal medicine decoctions. Studies involving herbal medicines in pill, capsule, and powder forms were excluded. The control group received conventional medicine, no treatment, or a placebo.

2.3.4. Types of Outcome Measurements

Primary Outcome

- -

- The total RR: (recovery + marked improvement + improvement)/total number of cases * 100%;

- -

- Recovery rate: clinical cure/total number of cases * 100%;

- -

- Recurrence rate.

Secondary Outcome

- -

- Changes in CRP level and the ESR in laboratory studies;

- -

- Symptom score (oral ulcer, genital ulcer, eye inflammation, skin lesions, arthralgia);

- -

- Adverse events (AEs).

2.4. Data Extraction and Risk of Bias Assessment

2.4.1. Data Extraction

Two authors (J.H.J. and T.Y.C.) independently searched 11 electronic databases and read all eligible studies in full to determine the extent to which they met the eligibility criteria. Disagreements were resolved by HWL. Two authors (J.H.J. and T.Y.C.) extracted the data from the included studies. The data extraction form collected the first author, year of publication, diagnosis, sample size, duration of treatment, intervention group, control group, the main outcome, results, and AEs. Disagreements were resolved by a third author (H.W.L).

2.4.2. Risk of Bias

Two evaluators (J.H.J. and T.Y.C.) assessed the studies using the risk of bias assessment tool from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [18]. The following seven domains were assessed: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other biases. We evaluated the risk of bias as “L” (low risk of bias), “H” (high risk of bias), and “U” (risk of bias is uncertain). Disagreements were resolved by M.S.L. We used the online version of the grading of recommendations assessment, development, and evaluation (GRADE) to assess the certainty of the evidence (CoE). The following seven categories were assessed: (1) number of studies, (2) study design, (3) risk of bias, (4) inconsistency, (5) indirectness, (6) imprecision and (7) other considerations [19].

2.4.3. Data Analysis

Data analyses were performed using Review Manager (Ver. 5.3) software. For dichotomous data, we used the treatment effect as the risk ratio (RR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). For continuous data, we present the treatment effect as the mean difference (MD) with 95% CI. The chi-squared test and Higgins I2 test were used to assess heterogeneity. To supplement the results for the meta-analysis of available effects, albatross plots of each included study sample size against respective p-values were used to provide a visual extension of effect direction for the primary and secondary outcomes using STATA/SE v.16.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

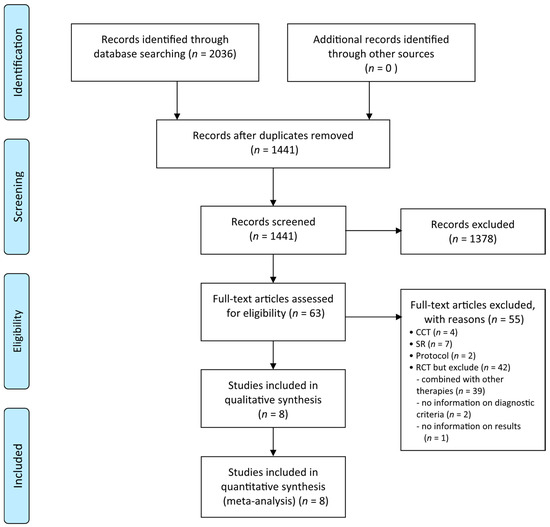

3.1. Description of the Included Trials

The searches identified 2036 potentially relevant studies, of which eight [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27] studies met our inclusion criteria (Figure 1). The key data from all included RCTs are summarized in Table 1. The RCTs published in Chinese included three master theses. The sample size ranged from 30 to 180. The duration of treatment ranged from three weeks to three months. The included studies used different disease criteria. Five RCTs [21,22,24,26,27] diagnosed BD according to the 1989 ISG criteria, two RCTs [20,23] used the 1989 ISG criteria plus the Standard for Disease in Traditional Chinese Medicine diagnostic criteria, and one RCT [25] used the 2005 ICBD criteria plus the Standard for Disease in Traditional Chinese Medicine diagnostic criteria.

Figure 1.

Flow chart. CCT: controlled clinical trials; RCT: randomized controlled trials; SR: systematic review.

Table 1.

Summary of randomized controlled trials of herbal medicine for Behçet’s disease.

For the control group treatment, three RCTs [20,21,22] used prednisone, two RCTs [23,24] used thalidomide, and three RCTs used prednisone plus thalidomide [25], loxoprofen sodium plus thalidomide [26], and interferon α-2b injection [27]. Seven RCTs used oral administration, and another RCT used injections.

The prescriptions used in the intervention group were different. The constituents of the herbal medicines used in each included study are listed in detail in Table 2. There were 8 prescriptions collected, among which 3 were set prescriptions [20,22,26], 2 were modified set prescriptions [24,25], 2 were pattern identification (PI) prescriptions [23,27], and 1 prescription was formulated based on personal experience [21]. There were 72 herbs in total. The most commonly used herbs for BD were Glycyrrhizae Radix et Rhizoma, Angelicae Sinensis Radix, Paeoniae Radix Alba, Asparagi Radix, and Glycyrrhizae Radix et Rhizoma Praeparata.

Table 2.

Composition of the herbal medicines for Behçet’s disease.

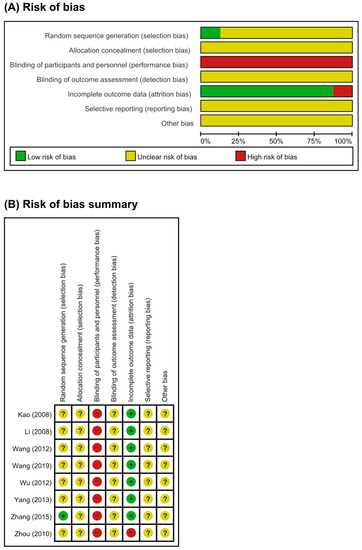

3.2. Risk of Bias

The risk of bias is presented in Figure 2. The risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool. Only one RCT [25] used the random number method for random sequence generation. Seven RCTs [20,21,22,23,24,26,27] did not report the random sequence generation method. Among the eight included RCTs [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27], herbal medicine decoctions, and drug therapy were compared; thus, blinding could not be applied to participants and personnel. None of the RCTs described the method of allocation concealment or blinding of outcome measurement. One RCT [22] did not provide the reasons for patient drop-out and withdrawal. None of the RCTs published or registered their protocol, and they all had an unclear risk of bias with regard to selective outcome reporting.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias. (A) Risks of bias of graph: review authors’ judgments about each item’s risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies. (B) Risks of bias summary: review authors’ judgments about each item’s risk of bias for each included study. +: low risk of bias; −: high risk of bias; ?: unclear.

3.3. Certainty of Evidence

The CoE for each outcome was either low or very low (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of findings.

3.4. Outcome Measurements

3.4.1. Primary Outcomes

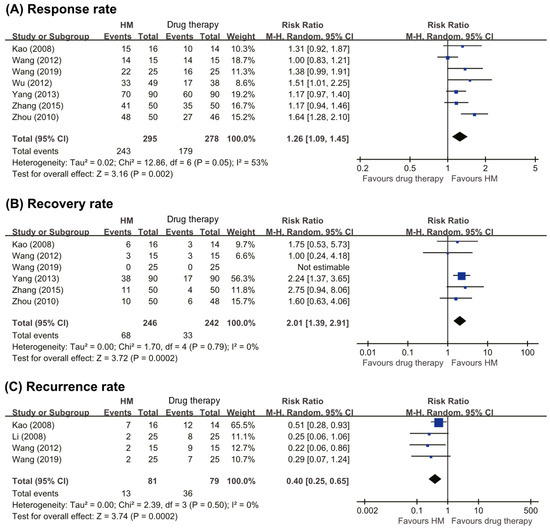

Total Response Rate

Seven RCTs [20,22,23,24,25,26,27] compared the effect of herbal medicine with that of drug therapies. One RCT [22] showed favorable effects of herbal medicine on the total RR compared with drug therapies, and the other six RCTs [20,23,24,25,26,27] reported equivalent effects. The meta-analysis showed favorable effects of herbal medicine on the total response rate (RR 1.26, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.45, seven trials, n = 573, p < 0.002, I2 = 53%, Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Forest plots of (A) total response rate, (B) recovery rate, and (C) recurrence rate. HM: herbal medicine.

Recovery Rate

Six RCTs [20,22,23,24,25,26] compared the effect of herbal medicine with that of drug therapies. One RCT [24] reported that no patients recovered in either group, while another RCT [26] reported that herbal medicine was a more effective therapy. The remaining four RCTs [20,22,23,25] showed equivalent effects in the two groups. The meta-analysis showed favorable effects of herbal medicine on the patient recovery rate (RR 2.01, 95% CI 1.39 to 2.91, six trials, n = 488, p < 0.0002, I2 = 0%, Figure 3B).

Recurrence Rate

Four RCTs [20,21,23,24] compared the recurrence rates between patients taking herbal medicine and drug therapies. Three RCTs reported that herbal medicine lowered the recurrence rate compared with conventional drugs [20,21,23,24], while one RCT found recurrence rates between the two groups after 12 months of follow-up [24]. The meta-analysis showed favorable effects of herbal medicine on the recurrence rate (RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.65, four trials, n = 160, p = 0.0002, I2 = 0%, Figure 3C).

3.4.2. Secondary Outcomes

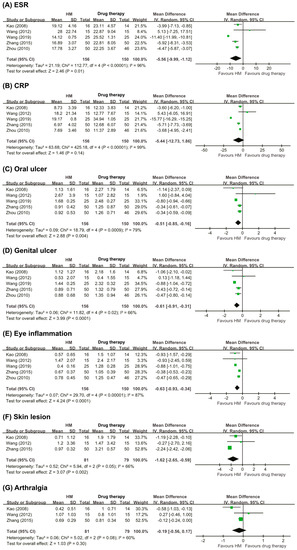

ESR and CRP

Five RCTs [20,22,23,24,25] compared the effects of herbal medicine and drug therapies on the ESR and CRP levels. Four RCTs [20,22,24,25] showed favorable effects of herbal medicine compared to drug therapies, and one RCT [23] showed inferior effects of herbal medicine. The meta-analysis showed a favorable effect of herbal medicine on the ESR (MD −5.56, 95% CI −9.99 to −1.12, five trials, n = 306, p = 0.01, I2 = 96%, Figure 4A), but failed to do so regard to the CRP level (MD −5.44 95% CI −12.73 to 1.86, five trials, n = 306, p = 0.14, I2 = 99%, Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Forest plots of symptoms score (A) ESR, (B) CRP, (C) oral ulcer, (D) genital ulcer, (E) Eye inflammation, (F) skin lesions, and (G) arthralgia. CRP: C-reactive protein; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HM: herbal medicine.

Symptom Score

Oral Ulcers

Six RCTs [20,21,22,23,24,25] assessed the symptom score for oral ulcers. Three RCTs [22,24,25] reported superior effects of herbal medicine compared with drug therapies, while the other three RCTs [20,21,23] showed inferior results. Only five RCTs [20,22,23,24,25] were applicable for meta-analysis. The results of the meta-analysis showed a superior effect of herbal medicine to that of drug therapy on the symptom score for oral ulcers (MD −0.51, 95% CI −0.85 to −0.16, five trials, n = 306, p = 0.004, I2 = 79%, Figure 4C).

Genital Ulcers

Six RCTs [20,21,22,23,24,25] assessed the symptom score for genital ulcers. Three RCTs [22,24,25] reported that the effects of herbal medicine were superior to those of drug therapies; however, three RCTs showed inferior results. Only five RCTs [20,22,23,24,25] were included in the meta-analysis. The result of the meta-analysis showed a greater effect of herbal medicine than of drug therapies on the symptom score for genital ulcers (MD −0.61, 95% CI −0.91 to −0.31, five trials, n = 306, p < 0.0001, I2 = 66%, Figure 4D).

Eye Inflammation

Six RCTs [20,21,22,23,24,25] reported the symptom scores for eye inflammation. Three RCTs [20,22,25] reported that herbal medicine had superior effects to those of drug therapy, while three RCTs showed [21,23,24] similar effects. Only five RCTs [20,22,23,24,25] were included in the meta-analysis. The result of the meta-analysis showed favorable effects of herbal medicine with regard to reducing eye inflammation compared with drug therapy (MD −0.63, 95% CI −0.93 to −0.34, five trials, n = 306, p < 0.0001, I2 = 87%, Figure 4E).

Skin Lesions

Four RCTs [20,21,23,25] assessed the symptom scores for skin lesions. Two RCTs [20,25] reported that the effects of herbal medicine were superior to those of drug therapies, while two RCTs [21,23] showed equivalent effects between the intervention group and the control group. Only three RCTs [20,23,25] were applicable for meta-analysis. The result of the meta-analysis showed a favorable effect of herbal medicine with regard to reducing skin lesions (MD −1.62, CI −2.65 to −0.59, three trials, n = 160, p = 0.002, I2 = 66%, Figure 4F).

Arthralgia

Four RCTs [20,21,23,25] reported the symptom scores for arthralgia. One RCT [20] reported that the effects of herbal medicine were superior to those of drug therapies, while three RCTs [21,23,25] showed equivalent effects between the two groups. Only three RCTs [20,23,25] were applicable for meta-analysis. The results of the meta-analysis showed no significant difference between the two groups (MD −0.19, 95% CI −0.56 to 0.17, three trials, n = 160, p = 0.30, I2 = 60%, Figure 4G).

AEs

Three RCTs [21,23,27] reported Es, whereas five RCTs [20,22,24,25,26] did not report AEs (Table 1). One RCT [27] did not report the detailed symptoms of AEs. Two RCTs [20,23] reported Es in the intervention group, including diarrhea. The other RCT [23] reported AEs in the control group, including insomnia, dizziness, and constipation.

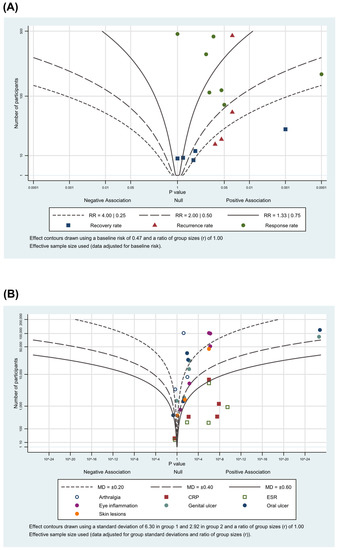

3.5. Albatross Plot

The albatross plots for the included studies are shown in Figure 5. Albatross plots were performed by illustrating contours that showed the effect direction and effect sizes range using p-values and given sample sizes. Different plotting colors correspond to the outcome subgroups. Looking at the albatross plot for dichotomous data (Figure 5A), the points scattered across different contour lines. However, most of the points clustered to the right side of the plot, showing that herbal medicine was more favorable for the treatment of BD. For the albatross plot of continuous data (Figure 5B), the points were less scattered. Although the points were clustered to the right, many points were positioned around the null line, implicating non-significant effects. Both albatross plots had points that were completely isolated, reflecting the possibility of sampling error.

Figure 5.

Albatross plot for (A) primary outcomes; (B) secondary outcomes.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of the Main Results

The aim of this systematic review was to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of herbal medicine for the treatment of BD. Eight studies [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27] evaluating the effect of herbal medicine on BD showed the following results. Herbal medicine reduces the ESR, reduces the symptom scores (oral ulcers, genital ulcers, eye inflammation, skin lesions), decreases the recurrence rate and improves the total clinical effective rate, although some studies have not provided evidence of the superiority of herbal medicine in terms of the symptom score for arthralgia and the CRP. Three RCTs [21,23,27] reported Es, but these Es were generally mild, and the patients spontaneously recovered. Overall, the results showed that herbal medicine decoctions might be useful in the treatment of BD.

4.2. Overall, Completeness and Applicability of the Evidence

This review shows that herbal medicine can be used to improve clinical symptoms in BD patients and that there are fewer Es associated with its use than with drug therapies. Despite the positive results, the included studies had small sample sizes and generally poor methodological quality; furthermore, they were too heterogeneous to allow any firm conclusions to be drawn regarding the different types of herbal prescriptions.

4.3. Quality of the Evidence

The CoE was low and very low for all outcomes (Table 3). Among the included RCTs, none reported the randomization methods, allocation concealment, or blinding of information. They did not publish their protocols, and it was not clear whether the planned result indicators were reported accurately. Therefore, they were downgraded one level in the risk of bias domain. The heterogeneity was substantial; thus, they were downgraded one or two levels. The included studies were PICO (patient, intervention, comparison, outcomes) studies, and it was determined that there was insufficient direct evidence of an effect. All outcomes had wide CIs that crossed the assumed threshold of the minimal clinically important difference; thus, they were downgraded one level for imprecision. Furthermore, the number of trials and total sample sizes included in our analysis was not sufficient to enable us to draw firm conclusions.

4.4. Potential Biases in the Review Process

This review has several limitations. First, the included studies used different herbal prescriptions, the effectiveness of which for the treatment of BD was not well known. Therefore, future studies should analyze studies using similar herbal prescriptions. Second, the evidence of improvements in symptoms varied according to the herbal decoction, possibly due to the varying compositions and dosages of the herbs. This review shows that herbal medicine has effects that are superior to those of drug therapy according to the composition of herbs, but the effects of dosages were unclear. Therefore, future studies should focus on the detailed composition and dosages of herbs. Third, all included studies were conducted in China, where no negative studies have been reported [28]. Furthermore, the albatross plots also showed scattered points across contour lines, with a few points being isolated from the other point clusters. As the sample sizes of the included studies were relatively small, this would likely reflect possible sampling bias.

4.5. Agreements and Disagreements with Other Studies or Review

We found three previous systematic reviews [12,13,14] on the use of herbal medicine for BD. These studies reported that herbal medicine was better than drug therapy for the treatment of BD. We identified two new RCTs [24,25] and extracted evidence from them. The results and evidence levels were similar to those of the studies included in the three previous systematic reviews. Moreover, the authors of those reviews expressed concern regarding the small sample sizes and the poor quality of the included studies. Future well-designed RCTs with large sample sizes are thus warranted.

4.6. Potential Mechanism of Action

In spite of the comparative absence of compelling evidence toward herbal medicines for BD, the potential features that may be related point towards benefits. These properties include anti-inflammation, immunoregulation, and antioxidation with chronic autoimmune disease and the studies focusing on the fusion of medicinal plants and cytokine activity effects. Since the disparity in the expression of innate immunity-related cytokines cannot only play a crucial role in BD pathogenesis but can also be pivotal in the level of severity of the disease [29]. Further, the disease activity score and clinical activity index may also be influenced by the levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines [30,31]. The herbal prescriptions mostly used Glycyrrhizae Radix et Rhizoma and Angelicae Sinensis Radix, which have anti-inflammatory effects [32,33]. The biological of herbal medicines linked with BD were not focused on in the present review. However, herbal medicines’ properties used to treat BD must be researched further.

The therapeutic effects of herbal medicine possibly rely on the obtainability and quantity of the different components in the production. The applicable data are sometimes not included in many publications. The daily prescribed quantity of the trials included in the study is diverse across the included studies-in their condition severity and traditional diagnosis type. However, no research has been conducted on the prime dose to reduce BD symptoms. In the present study, when we analyzed the result direction and dosage, treatment time, dosage and time, and the type of results, no direct links with dose and the treatment time for relevant changes of various results. The variety in trials does not present clear relations. Different herbal medicines were compared and examined with drug therapies using several methods. The contrasts in significance may result from the type of herbal medicines and dosage in treatments. The quantity and frequency of herbal medicines utilized in the trials included in the study may be inadequate to create a noteworthy effect in biochemical variables. Thus, it is required to conduct studies ranging in doses and comparing a variety of herbal medicines to various outcomes to answer such questions.

4.7. Implications for Nutrients

The applicability of the present review could be questioned in the fields of nutrients. Herbal materials are derived from plants, and many such substances are part of both food supplements and nutraceuticals as well as medicinal products [34,35,36,37]. In the US, regulatory bodies such as FDA governing plant-based medicines usually regard them as dietary supplements [35]. Dietary recommendations refer to herb usage as an outstanding source of antioxidants in Australia [34,38]. Furthermore, in Traditional East Asian Medicine, such medicines are consumed in the form of herbal tea or supplemental food. With the increase of the presence of herbs in diets owing to their health advantages, utilization of herbal medicines for BD may be possible in the capacity of a herbal supplement, in addition to the main diet containing functional foods or nutraceuticals per respective regulatory systems across countries [35,39,40,41]. However, such supplements for BD should ensure avoidance of any side effects by undergoing quality testing and safety protocols taken for dietary supplements and functional foods.

4.8. Implications for Practice

BD is a chronic inflammatory disease in which ulceration occurs repeatedly. Herbal medicine is associated with a lower rate of recurrence and is relatively safer than drug therapies. It appears useful in clinical practice. However, the included studies had only short-term treatment periods and used various forms of prescriptions. Thus, long-term clinical research and standardized prescriptions should be implemented in future studies.

4.9. Implications for Research

This review has several limitations with regard to the research process. First, the risk of bias in this review was unclear. The majority of trials did not report randomization procedures, and all of them lacked information on blinding. None of them reported the randomization and allocation methods, published their protocols, or registered at PROSPERO. Thus, future studies should be described in detail or registered at PROSPERO. Second, rigorous RCTs should be carried out to analyze the effectiveness of herbal medicine for the treatment of BD. Adequate data on the clinical outcomes of BD treated with herbal medicine could guide clinical decision-making. Future studies should be comprehensively reported according to the CONSORT reporting guidelines [42].

5. Conclusions

This review showed that herbal medicine decoctions might be useful in the treatment of BD. However, the quality of the current evidence was low, the small effect size reduced the clinical significance, and the small number of rigorous studies prevented us from drawing firm conclusions. Well-designed RCTs are needed to determine whether herbal medicine is a viable option for the treatment of BD.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/13/1/46/s1, Supplement 1. Search strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: J.H.J., T.Y.C., M.S.L.; data curation: J.H.J., T.Y.C., H.W.L.; formal analysis: J.H.J., T.Y.C., L.A.; investigation: J.H.J., T.Y.C.; methodology: T.Y.C., H.W.L., M.S.L.; supervision: M.S.L.; validation: T.Y.C., L.A., H.W.L.; writing—original draft: J.H.J., M.S.L.; writing—review and editing: T.Y.C., H.W.L., L.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from Integrative Medicine Research Project through Wonkwang University Jangheung Integrative Medical Hospital, funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number:1465025215) and the Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine (G17250, KSN2013210).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable for studies not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable for studies not involving humans.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Jagdish, R.N.; Robert, J.M. Behcet’s disease. Clin. Med. 2017, 17, 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Yazici, H.; Seyahi, E.; Hatemi, G.; Yazici, Y. Behçet syndrome: A contemporary view. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2018, 14, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kural, S.E.; Fresko, I.; Seyahi, N.; Ozyazgan, Y.; Mat, C.; Hamuryudan, V.; Yurdakul, S.; Yazici, H. The long-term mortality and morbidity of Behçet syndrome: A 2-decade outcome survey of 387 patients followed at a dedicated center. Medicine 2003, 82, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mat, C.; Yurdakul, S.; Uysal, S.; Gogus, F.; Ozyazgan, Y.; Uysal, O.; Fresko, I.; Yazici, H. A double-blind trial of depot corticosteroids in behcet’s syndrome. Rheumatology 2005, 45, 348–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nava, F.; Ghilotti, F.; Maggi, L.; Hatemi, G.; Del Bianco, A.; Merlo, C.; Filippini, G.; Tramacere, I. Biologics, colchicine, corticosteroids, immunosuppressants and interferon-alpha for Neuro-Behçet’s Syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Onakpoya, I.J.; Posadzki, P.; Eddouks, M. The safety of herbal medicine: From prejudice to evidence. Evid. Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 316706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.G.; Jin, L.; Wu, J.L.; Cao, C.H. Progress in traditional chinese medicine treatment of behcet’s disease. Hunan J. TCM 2018, 34, 170–171. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.S.; Kim, S.O.; Lim, W.K.; Lee, J.M.; Hwang, C.Y.; Cho, K.H.; Kim, H.M. Novel effects of on-chung-eum, the traditional plant medicine, on cytokine production in human mononuclear cells from behçet’s. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2003, 25, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchers, A.T.; Sakai, S.; Henderson, G.L.; Harkey, M.R.; Keen, C.L.; Stern, J.S.; Terasawa, K.; Gershwin, M.E. Shosaiko-to and other Kampo (Japanese herbal) medicines: A review of their immunomodulatory activities. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2000, 73, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Chung, H.S.; Lee, J.G.; Lim, W.K.; Hwang, C.Y.; Lee, E.J.; Cho, K.H.; Wi, D.H.; Kim, H.M. Inhibition of cytokine production by the traditional oriental medicine, ‘Gamcho-Sasim-Tang’ in mitogen-stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells from Adamantiades-Behçet’s patients. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002, 83, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.G.; Ahn, K.S. Experimental studies on the kinds of sasim-tang in behcet’s disease symptoms in ICR mice. Korean J. Orient. Physiol. Pathol. 2004, 18, 1061–1070. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.R.; Xu, J.L.; He, D.Q.; Tian, J.H. Effectiveness of Chinese medicine in the treatment of behcet’s disease: A meta- analysis. J. Basic Chin. Med. 2015, 21, 872–874. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.J.; Du, B.; Huang, S.P. Meta-analysis of clinical efficancy of chinese medicine in the treatment of behcet’s disease. Rheum. Arthritis 2017, 6, 42–45, 62. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.R.; He, D.Q.; Du, H.L.; Tian, J.W. Traditional medicine and integrative medicine for behcet’s disease: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Sandong Med. 2014, 54, 91–94. [Google Scholar]

- Jun, J.H.; Choi, T.Y.; Zhang, J.; Ko, M.M.; Lee, M.S. Herbal medicine for Behcet’s disease: A protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2018, 97, e0165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Study Group for Behcet’s Disease. Criteria for diagnosis of Behcet’s disease. Lancet 1990, 335, 1078–1080. [Google Scholar]

- International Team for the Revision of the International Criteria for Behcet’s Disease. The International Criteria for Behcet’s Disease (ICBD): A collaborative study of 27 countries on the sensitivity and specificity of the new criteria. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2014, 28, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeks, J.J.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G. Chapter 10: Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In Cochrane handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 2nd ed.; Higgins, J.P.T., Thomas, J., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 214–284. [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt, G.; Oxman, A.D.; Akl, E.A.; Kunz, R.; Vist, G.; Brozek, J.; Norris, S.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Glasziou, P.; DeBeer, H.; et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, X.L. Clinical observation on 16 cases of behcet’s disease treted by yiqi tuodu decoction. J. TCM 2008, 49, 329. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.T.; Kong, D.J. Clinical obervation of behcet’s disease treated by traditional chinese medicine. J. Qiqihar Med. Coll. 2008, 29, 1671–1673. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y. Clinical Study of Gan Chi Soup Medicine on Behcet’s Disease. Master’s Thesis, Hebei University, Hebei, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.L. Clinical Reserch on Behcet’s Disease TCM Treatment Based on Combination of Disease and Syndrome. Master’s Thesis, Sandong University, Sandong, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.T. Clinical Obsevation on the Treatment of Stagnated Qi Transforming into Fire Behcet’s Disease with Jiawei Xiaoyao San. Master’s Thesis, Heilongjiang University, Heilongjiang, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.R.; He, Z.Q.; Liu, B.Y.; Chen, Y.F. 50 cases of behcet’s syndrome treated with gancao xiexin decoction and sanhuang. TCM Res. 2015, 28, 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M. Clinical observation on 90 cases of behcet’s disease treated with bushen huoxue yuyang decoction. J. Sichan TCM 2013, 31, 92–93. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.Q.; Gao, F.Y.; Yu, H.M.; Zhang, Y.P.; Hna, Z.Z. Observation on the therapeutic effect of treating behcet’s disease. J. Sichan TCM 2012, 30, 108–109. [Google Scholar]

- Vickers, A.; Goyal, N.; Harland, R.; Rees, R. Do certain countries produce only positive results? a systematic review of controlled trials. Control. Clin. Trials 1998, 19, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholijani, N.; Ataollahi, M.R.; Samiei, A.; Aflaki, E.; Shenavandeh, S.; Kamali-Sarvestani, E. An elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines profile in Behcet’s disease: A multiplex analysis. Immunol. Lett. 2017, 186, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, J.J.; Zhao, L.; Taylor, E.W.; Spelman, K. The influence of traditional herbal formulas on cytokine activity. Toxicology 2010, 278, 140–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.Z.; Zhang, S.N. Herbal compounds for rheumatoid arthritis: Literatures review and cheminformatics prediction. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-F.; Lin, S.-S.; Liao, P.-H.; Young, S.-C.; Yang, C.-C. The Immunopharmaceutical Effects and Mechanisms of Herb Medicine. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2008, 5, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.P.; Zhang, D.-D.; Ke, Y.; Bian, K. The vasodilatory effects of anti-inflammatory herb medications: A comparison study of four botanical extracts. Evid. Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2017, 2017, 1021284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, S.M.; Youssef, A.M. Potential application of herbs and spices and their effects in functional dairy products. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, M. Food–Herbal Medicine Interface. In Encyclopedia of Food and Health; Caballero, B., Finglas, P.M., Toldrá, F., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Marković, T.; Emerald, M.; Dey, A. Herbs: Composition and Dietary Importance. In Encyclopedia of Food and Health; Caballero, B., Finglas, P.M., Toldrá, F., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wu, F.; Yuan, W.; Ding, Q.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Xing, J.; Wang, S. Systematic Review of Herbal Tea (a Traditional Chinese Treatment Method) in the Therapy of Chronic Simple Pharyngitis and Preliminary Exploration about Its Medication Rules. Evid -Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2019, 2019, 9458676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapsell, L.C.; Hemphill, I.; Cobiac, L.; Patch, C.S.; Sullivan, D.R.; Fenech, M.; Roodenrys, S.; Keogh, J.B.; Clifton, P.M.; Williams, P.G.; et al. Health benefits of herbs and spices: The past, the present, the future. Med. J. Aust. 2006, 185, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruffell, M.J. Nutrition and health claims for food: Regulatory controls, consumer perception, and nutrition labeling. In Encyclopedia of Food and Health; Caballero, B., Finglas, P.M., Toldrá, F., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, A.; Cammarata, S.M.; Capone, G.; Ianaro, A.; Tenore, G.C.; Pani, L.; Novellino, E. Nutraceuticals: Opening the debate for a regulatory framework. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 84, 659–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santini, A.; Novellino, E. Nutraceuticals—Shedding light on the grey area between pharmaceuticals and food. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 11, 545–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, K.F.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D. CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2010, 63, 834–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).