Abstract

Little is known about socioeconomic differences in the association between the food environment and dietary behavior. We systematically reviewed four databases for original studies conducted in adolescents and adults. Food environments were defined as all objective and perceived aspects of the physical and economic food environment outside the home. The 43 included studies were diverse in the measures used to define the food environment, socioeconomic position (SEP) and dietary behavior, as well as in their results. Based on studies investigating the economic (n = 6) and school food environment (n = 4), somewhat consistent evidence suggests that low SEP individuals are more responsive to changes in food prices and benefit more from healthy options in the school food environment. Evidence for different effects of availability of foods and objectively measured access, proximity and quality of food stores on dietary behavior across SEP groups was inconsistent. In conclusion, there was no clear evidence for socioeconomic differences in the association between food environments and dietary behavior, although a limited number of studies focusing on economic and school food environments generally observed stronger associations in low SEP populations. (Prospero registration: CRD42017073587)

1. Introduction

Socioeconomic inequalities in dietary behavior are persistent and widespread [1] and are contributing to inequalities in diet-related chronic diseases [2]. Several explanatory mechanisms for these inequalities have been proposed. Individuals with lower socioeconomic position (SEP) according to educational attainment, income levels or occupation status may lack the material and psychosocial resources that generally accompany a higher SEP. Indeed, material resources such as higher food budgets and access to health-promoting goods and services [3,4] and psychosocial resources such as nutrition knowledge, cooking skills and positive attitudes towards healthy eating [5,6,7,8] are known to contribute to healthier dietary behavior.

Having fewer material and psychosocial resources may limit individuals’ capacity to resist unhealthy temptations in the food environment [9] or to take advantage of healthy options in the food environment. For example, higher educated individuals may be better able to deal with an unhealthy food environment because of their individual-level resources such as higher food budgets, better planning skills or more nutritional knowledge compared to those with lower education levels. If food environments are characterized by the availability and promotion of high-energy and ultra-processed foods—as is common in most Western countries [10]—food choices of those having fewer material and psychosocial resources are more likely to be unhealthy.

While there is some evidence that food environments are unhealthier in more deprived areas [11]—also referred to as the ‘deprivation amplification’ or the double burden of deprivation [12,13]—little is known about the differential effects of the food environment on dietary behavior in higher and lower SEP groups. Such socioeconomic inequalities in the effects of the food environment on dietary behavior could in fact provide an explanation for the weak or inconsistent associations described in the numerous systematic literature reviews summarizing the influence of the food environment on dietary behavior so far [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. If individuals with a high or low SEP respond differently to their food environments, this may confound the association between aspects of the food environment and dietary behavior in studies that do not specifically consider the role of SEP. There is indeed some evidence that the food environment impacts dietary behavior differentially across socioeconomic strata. Three UK studies indicated that having a higher SEP is protective against exposure to unhealthy food environments [25,26,27]. However, evidence for this hypothesis has not been systematically reviewed. A better understanding of how food environments impact high and low SEP groups differentially would contribute to public health strategies targeting dietary inequalities.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to systematically review the evidence for socioeconomic differences in the association between the food environment and dietary behavior. in adolescents and adults. We included studies that stratified their population on the basis of SEP and studied the food environment-diet association in these strata. In addition, we included studies that investigated a single SEP group to assess if associations between the food environment and dietary behavior are generally stronger or more consistent in either high or low SEP populations.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a systematic literature review according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines [28]. The protocol for this literature search was registered in the Prospero database, registration number CRD42017073587 (can be found via https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/).

2.1. Literature Search

Original, peer-reviewed studies that examined associations between the food environment and dietary behavior in different socioeconomic strata or in a single SEP group were included. Food environments were defined as all objective and perceived aspects of the economic and physical food environment outside the home. Dietary behavior was defined as all measures of dietary behavior of foods and food groups, dietary patterns and food purchasing behavior. Socioeconomic groups were defined as individual, household or area-level measures of education, income, occupation or receiving benefits. Only studies with a study population of adolescents or adults (aged twelve years or over) were considered, as the food choices of children younger than twelve years are less likely to be directly influenced by the food environment (but rather via their parents’ food choices). Furthermore, only studies with an observational study design (including baseline data of experimental studies) were included since we were interested in the differential response to long-term environment rather than the differential response to a (short term) change in the food environment as is the case in experiments. A detailed overview of the inclusion criteria is available in Table 1. A systematic literature search was performed in 4 electronic databases (Medline, Embase, Psycinfo and Web of Science) for studies published up to June 2018 in the English or Dutch language. The search strings can be found in Supplementary File S1. An additional manual search was performed to identify relevant articles based on the reference list of included studies.

Table 1.

Inclusion criteria.

Papers identified by the search strategy were uploaded in Rayyan for screening. Rayyan is a free web and mobile app that facilitates multi-author screening of abstracts and titles [29]. To refine the in- and exclusion criteria, the first 100 retrieved articles were screened on the basis of title and abstract. Inclusion rates were compared and if necessary, adjustments were made to the criteria. Thereafter, titles and abstracts were equally divided among five of the authors for screening of relevance according to the review inclusion criteria.

Full text versions of all records deemed eligible on the basis of title and abstract were searched through the four electronic data bases or alternatively searched via Google Scholar or requested by e-mail from the corresponding authors. The retrieved full texts were reviewed for inclusion.

2.2. Data Extraction

The following information was extracted from the included studies:

- Study characteristics (author, year of publication, sample size, response rate, country, study design, objective);

- Population characteristics (e.g., age group);

- Type of dietary behavior (e.g., healthy eating index, adherence to dietary guidelines, fruit and vegetable (F & V) intake);

- Aspect of food environment studied (e.g., distance to nearest supermarket);

- Indicator of SEP (e.g., education, income, social class);

- Results and conclusion.

Extracted data was summarized in tables based on type of food environment measure (e.g., perceived food environment, school food environment).

2.3. Assessment of Methodological Quality

All included studies were independently assessed for methodological quality using the 14-item NIH quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies [30]. With regard to the item ‘accuracy, objectivity, validity and reliability of the outcome measures’, studies were rated positively when using a dietary assessment tool that was validated in the population under study or when using objective information on dietary purchases. Studies were rated neutrally when using a previously validated dietary assessment tool or using a combination of self-reported and objective dietary purchase outcomes. Studies were rated negatively when using a non-validated dietary assessment tool, or when a previously validated tool was adapted without further validation. Generally, articles were rated ‘Good’ when they had ≥6 times ‘Yes’, ‘Fair’ when they had 3–5 times ‘Yes’, and ‘Poor’ when they had 0–2 times ‘Yes’, but per instruction of the quality assessment tool, an assessment of the overall quality of the article was also included in the rating.

3. Results

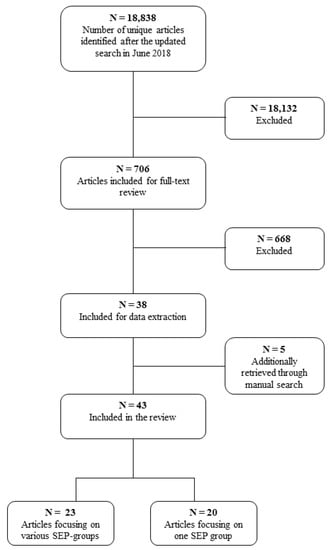

After removal of duplicates, 18,838 articles were screened on the basis of title and abstract. A total of 18,132 records were excluded after reading title and/or abstract, leaving 706 articles for full-text screening. A further 668 articles were excluded on the basis of inclusion/exclusion criteria. Based on the reference lists of the thirty-eight studies included for data extraction, five additional papers were identified. Most exclusions were done because authors did not present food environment-diet associations by SEP, but only associations between the food environment and dietary behavior adjusted for SEP as covariate. A total of forty-three papers were included in the review, of which twenty-three studied the association between aspects of the food environment and dietary behavior across different SEP strata (Table 2) and twenty studied this association in a single SEP group (Table 3). The study selection flowchart is presented in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Overview of included studies reporting on associations between aspects of the food environment and diet across different socioeconomic groups—by type of food environmental factor studied.

Table 3.

Overview of included studies reporting on associations between aspects of the food environment and diet in a single socioeconomic group – in alphabetical order.

Figure 1.

Study selection flow chart.

3.1. General Study Characteristics

General study characteristics are presented in Table 2 and Table 3. Briefly, the majority of studies were conducted in the USA (n = 27), followed by the UK (n = 5), Brazil (n = 3), Australia (n = 2) and Mexico, New Zealand, Finland, Canada, Hong Kong and France (n = 1 each). Thirty-nine out of forty-three studies had a cross-sectional design. Exceptions were two repeated cross-sectional studies by Colchero et al. [31] and Jilcott Pitts et al. [32] and two longitudinal studies by Meyer et al. [33] and Rummo et al. [34]. Thirty studies were conducted in an adult population [25,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59], seven were focused on adolescents [60,61,62,63,64,65,66] and six were conducted in a mixed age population [31,67,68,69,70,71]. Consumption or purchase of F & V were used as measure of dietary behavior in twenty-eight studies [32,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,42,43,44,46,48,49,52,53,55,56,58,60,61,63,64,66,67,68,70,71], seventeen used indicators of unhealthy dietary behavior such as intake or purchase of sugary sweetened beverages, snacks or fast food (FF) [26,31,32,33,38,40,42,48,51,53,58,62,64,65,66,69,70], and eleven used a composite index overall quality or healthfulness of the diet [25,34,38,41,44,45,47,50,54,57,59].

3.2. Associations of the Food Environment and Dietary Behaviours across Different SEP Strata

Of the twenty-three studies that considered the association between the food environment and dietary behavior interacting with or stratified according to SEP (Table 2), six papers focused on economic aspects of the food environment, namely objective measures of food prices [31,33,44,45,46,61]; twelve papers considered objectively measured aspects of the food environment such as access, proximity and quality of the food environment [25,26,34,47,48,49,50,51,52,69,70,71]; four studies focused specifically on the school food environment [62,63,64,65]; and one study studied the perceived availability of foods [66]. Half of the studies were conducted in the USA. SEP indicators used to investigate moderating effects were (household) income [31,34,44,48,63], (parental) education [25,26,51,65], household poverty/deprivation [45,64,66], employment status [70], public versus private schools [62], area level deprivation [49], receiving benefits [69] and a combination of multiple indicators [33,46,47,50,52,61,71].

Overall, studies that considered the association between economic aspects of the food environment and dietary behavior found differential associations on the basis of SEP. In five studies, objectively measured higher food prices of unhealthy foods were associated with either lower consumption of unhealthy foods or higher consumption of healthier foods, and higher prices of F & V were associated with lower consumption of F & V [31,33,44,46,61]. Four of these studies found that low SEP groups were more responsive to food prices [30,32,45,60]. One study did not find differential effects by SEP when linking fast food prices to fast food consumption but did observe that higher F & V prices were only associated with higher F & V consumption in a low SEP group [44]. The authors speculated that other, unmeasured, competing factors may have led to this unexpected finding [44]. Finally, one study found that a higher SEP group was more responsive to price promotions, most notably price promotions on healthier foods [45].

Studies that examined objectively measured access, proximity and quality of the food environment often did not find significant associations with dietary behavior, nor interactions by SEP [47,49,70,71]. Most studies focused on access and proximity of food retailers in the neighborhood. Three studies found associations between these aspects of the food environment and dietary behavior, but without any indication of moderation by SEP [50,52,71]. Four studies reported that associations between access, proximity and quality of the food environment were more strongly associated with dietary behavior in the socioeconomically disadvantaged subgroup compared to the higher socioeconomic groups [25,34,51,69], of which three studies focused on the neighborhood food environment and one on the in-store food environment. That is, these studies showed that less healthful in-store supermarket environments, poorer food environments, a higher proportion of convenience stores and shopping at supercenters or convenience stores were associated with a lower diet quality or unhealthier dietary behavior among those with low SEP, but this association was weaker, non-significant or in the opposite direction among those with high SEP. The authors suggested that fewer individual or neighborhood-level material and psychosocial resources make individuals with low SEP more vulnerable to availability and marketing of unhealthier foods [25,34,51,69]. Finally, one study observed that dietary inequalities between low and high income individuals were only present in neighborhoods with a low density of supermarkets and fresh produce markets [48] and one study reported that educational inequalities in fast food consumption were stronger in areas with higher fast food outlet exposure than in areas with lower fast food exposure [26].

All four studies examining socioeconomic differences in the association between the school food environment and dietary behavior showed interaction by SEP, although not all in the same direction. Two studies showed that low SEP adolescents benefitted more from healthy options in the school food environment than high SEP adolescents [63,64], one study showed that high SEP adolescents benefitted more from healthy options in the school food environment than low SEP adolescents [62] and one study showed that a fast food outlet or grocery store close to school was associated with irregular eating habits (described as an undesirable behavior) in low SEP adolescents only [65].

Finally, one study considered the perceived food environment and found that perceived availability of FF outlets, restaurants and convenience stores close to home was associated with unhealthy intakes, with larger effect sizes in adolescents from less affluent families than in adolescents from more affluent families [66].

3.3. Associations of the Food Environment and Dietary Behaviours in a Single SEP Group

All but one of the twenty studies that reported on the association between the food environment and dietary behavior in a single SEP group (Table 3) focused on a socioeconomically disadvantaged group in terms of receiving benefits, living in a deprived area, having low income, being low educated or having food insecurity status. The exception was the study by Leischner et al. which focused on university college students, thereby focusing on higher educated young adults [41]. Sixteen out of the twenty studies were conducted in the USA. Most of these twenty studies considered more than one aspect of the food environment: fourteen papers considered availability and quality of stores in the neighborhood [32,35,38,39,40,41,42,43,53,56,57,59,67,68]; ten papers studied access, distance or time taken to travel to stores [32,36,37,40,43,57,58,59,60,67,68]; and seven papers studied economic aspects of the food environment such as objective food cost and/or perceived affordability [32,43,53,54,55,56,67].

In the studies conducted among a socioeconomically disadvantaged group that considered availability and quality of stores in the neighborhood [32,35,38,39,40,41,42,43,53,56,57,59,67,68], five studies observed that perceived [39,40,56] and objective [36,41,42,57] availability of stores selling healthier products was associated with healthier dietary behavior and two studies observed that availability or use of stores selling unhealthier products was associated with unhealthier dietary behavior [42,60]. Six studies found no association between availability in food stores and dietary behavior [32,35,38,43,59,60]. One study showed that perceived food store access was not associated with F & V intake, while having both a supercenter and convenience store nearby was [35]. Another study showed that F & V and SSB consumption was higher in specific food shopping locations [53] but provided no explanation for this finding.

Of the ten papers that studied access, distance or time taken to travel to stores [32,36,37,40,43,57,58,59,60,67,68], six found non-significant associations [32,37,43,58,59,67,68] and seven observed positive significant associations [32,36,37,43,57,59,68]. For example, Rose et al. found that having ‘easy access’ to a supermarket was associated with higher daily fruit use, while perceived travel time was not. No studies reported unexpected associations.

Of the six papers that studied the role of economic aspects of the food environment for dietary behavior [32,43,53,54,55,56], two found no significant associations with objective food prices or perceived costs [32,56], and three found a negative association, such that higher objective food prices, higher perceived food costs and lower self-reported affordability were associated with lower diet quality or lower intake of healthy foods [43,54,55]. One study did not find an association between objective prices of F & V and F & V consumption but did find that higher SSB prices were associated with higher consumption of SSBs [53], which is an unexpected direction of the association. The authors suggested that this finding may be due to insufficient variation in SSB prices or misreporting of SSB consumption [53].

3.4. Quality Assessment

Of the forty-three included studies, twenty-six received a ‘good’ rating, fifteen received a ‘fair’ rating and two received a ‘poor’ rating (Table 4). Most studies scored poorly on the sample size justification and most studies did not use a validated tool to measure dietary behavior or used a previously validated tool but did not validate it in their study population. The two studies that received a ‘poor’ rating additionally did not describe their population clearly.

Table 4.

Quality Assessment of included articles.

3.5. Results by Study Characteristics

Finally, we assessed whether we found evidence for socioeconomic differences in the association between aspects of the food environment and dietary behavior in subsamples of the included studies. Taking into account study characteristics, different associations between the food environment and dietary behavior across SEP groups were observed in: Seven out of seven studies conducted among adolescents only [60,61,62,63,64,65,66], ten out of fifteen studies conducted outside the USA [25,31,36,45,51,55,60,62,65,66], three out of four non-cross-sectional studies [31,33,34], and fourteen out of twenty-six studies rated as having ‘good’ quality [25,31,33,34,36,40,42,44,46,54,55,57,63,65,69].

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to systematically review the literature on socioeconomic differences in the association between the food environment and dietary behavior of adolescents and adults. We included studies that stratified their population on the basis of SEP as well as studies that considered the association between the food environment and dietary behavior in a single SEP group (e.g., only low-income groups). The included studies were diverse in their measures of the food environment and dietary behavior, indicators of SEP, and their findings.

We hypothesized that the food environment would have a stronger effect on dietary behavior in those with lower SEP, and that associations between the food environment and diet would be more consistent if only one socioeconomic group was considered. We found some evidence to support the first hypothesis: In the studies that focused on economic (n = 6) and school food (n = 4) environments, associations with dietary behavior tended to be stronger in the socioeconomically disadvantaged subgroups. However, this was not the case for studies focusing on objectively measured access, proximity and quality of the food environment (n = 12). Only one study focused on perceived food environments, therefore little can be concluded about the strength of evidence for socioeconomic differences in these types of studies. We did not find strong evidence for the second hypothesis since associations in specific socioeconomic groups (mostly in low SEP groups) were inconsistent, with about half of the studies finding non-significant associations. Studies among adolescents (n = 7) and non-cross-sectional studies (n = 4) generated most consistent results.

The more consistent evidence for the interaction by SEP for economic and school food environments may be due to the fact that these aspects of the food environment are more delimited and that ‘exposure’ to these aspects of the food environment is easier to define compared to aspects of availability and accessibility in the overall food environment. The significant amount of time (‘exposure’) adolescents spend at school may explain why this type of environment has a relatively consistent influence on dietary behavior. It may be speculated that adolescents with a high SEP have a healthier home food environment, while low SEP with unhealthier home food environments may therefore benefit more from a healthy school food environment [72]. The results for economic aspects of the food environment echo the findings from studies demonstrating a stronger response to tax and subsidy policies from those with lower SEP [73,74]. Future studies could examine the pathways through which these socioeconomic differences arise; we speculated that both material and psychosocial resources may play a role, but literature on these pathways is scarce [75].

In the studies considering a single SEP group, predominantly focused on socioeconomically disadvantaged populations, evidence for an association of the availability and quality of stores, access, distance or time taken to travel to stores, and (perceived) food costs with dietary behavior was inconsistent. About half of the studies found significant associations in the expected direction, a few found significant associations in an unexpected direction, and the remainder found no significant associations. This is comparable to the findings of systematic literature reviews on the association between the food environment and dietary behavior across socioeconomically diverse populations [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24], providing little evidence that associations are more consistent when a more socioeconomically homogeneous population is considered. Many of the studies that focused on socioeconomically disadvantaged populations defined their population on the basis of community-level deprivation or income. This may leave room for socioeconomic variability within these communities, particularly if those with higher SEP were more likely to participate in the study. As such, the studies focusing on one specific SEP group may not truly have resulted in studies conducted in a socioeconomically homogeneous group. Additionally, on the basis of this literature review, little can be concluded about the role of the food environment for dietary behavior in a high SEP population, as we only identified one study that focused on such a population.

On the basis of previous literature reviews [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24] we speculated that observed null associations in a socioeconomically diverse sample may be due to opposing associations in higher and lower SEP groups, but many studies did not find significant differences between SEP groups. It is likely that the inconsistencies observed in this literature review have similar causes as the inconsistencies observed in general literature reviews on associations between the availability and accessibility of the food environment and diet. Namely: That similar measures of the food environment are difficult to compare between different contexts; that food environments are often simplified to metrics of single types of food retailers (i.e., proximity to supermarkets, or availability of F & V in convenience stores), while the food environment encompasses a broad range of interacting factors (e.g., an interplay of proximity, availability, marketing, labelling, etc.); and that researchers make many assumptions about the places and ways in which food environments influence dietary behavior [20,22]. This may be reflected in our finding that SEP differences were most consistent for studies focusing on economic and school food environments, which represent much more narrow aspects of the food environment than access, availability and quality of food retailers. In general, adherence to reporting guidelines on food environment studies such as the Geo-FERN reporting checklist [76] would facilitate the comparison of such studies in systematic reviews.

Strengths and Limitations

This is the first systematic literature review that examined socioeconomic differences in the association between the food environment and dietary behavior. Strengths of this study were the broad definition of food environment variables in order to capture all relevant literature; the use of four search engines; the performance of a rigorous quality assessment of the included studies; and the fact that screening, data extraction and quality assessment was performed by at least two researchers each. However, although systematic literature reviews occupy a top position in the hierarchy of evidence, they, including this one, suffer from a number of limitations. Although we piloted the screening process, the involvement of multiple authors in the screening process and the high number of potentially relevant articles in general may have led to the erroneous exclusion of relevant articles. Furthermore, the heterogeneous nature of the included studies prevented us from performing a meta-analysis of the findings, and this hampers the assessment of publication bias: Authors may not have reported non-significant interaction terms with SEP, which may have led to an overestimation of the SEP-differences in this review. The classification of studies into categories of food environment measures may also be noted as a limitation: As studies in single SEP groups examine different aspects of the food environment than studies stratified by SEP we were unable to use the same classification for both types of studies. Finally, whilst there was no limitation for language during the search strategy, our review consists entirely of articles published in English. This could be due to the fact that other relevant articles may not have been indexed in the electronic databases used for this review.

5. Conclusions

Evidence for socioeconomic differences in association between the food environment and dietary behavior was inconsistent, although a limited amount of studies focusing on economic and school food environments generally observed stronger associations in low SEP populations than in high SEP populations. Studies on the association between food environment and dietary behavior in a single SEP group were no more consistent than studies in a mixed population observed in previous literature reviews. As such, it is unlikely that the inconsistencies in the association between the food environment and diet that have been observed thus far are attributable to a differential response to food environments from high and low SEP groups.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/11/9/2215/s1, File S1: Search strings used for the systematic review on ‘A systematic review on socioeconomic differences in the association between the food environment and dietary behaviors’.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.G.M.N. and M.N.; methodology, J.D.M., K.G.M.N., S.C.D., M.P.P., J.G.D., J.B.L., M.N.; formal analysis, J.D.M., K.G.M.N.; data curation, J.D.M., K.G.M.N., J.B.L., M.N.; writing—original draft preparation, J.D.M., K.G.M.N., M.N.; writing—review and editing, J.D.M., K.G.M.N., S.C.D., M.P.P., J.G.D., J.B.L., M.N.; supervision, M.N.

Funding

JDM’s work was funded by an Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) VENI grant on “Making the healthy choice easier—role of the local food environment” (grant number 451-17-032). MPP’s work was funded by the NWO-MaGW Innovational Research Incentives Scheme Veni with the project ‘Geographies of Food consumption’ (grant number 451-16-029).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Giskes, K.; Avendano, M.; Brug, J.; Kunst, A.E. A systematic review of studies on socioeconomic inequalities in dietary intakes associated with weight gain and overweight/obesity conducted among European adults. Obes. Rev. 2010, 11, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrovic, D.; de Mestral, C.; Bochud, M.; Bartley, M.; Kivimäki, M.; Vineis, P.; Mackenbach, J.; Stringhini, S. The contribution of health behaviors to socioeconomic inequalities in health: A systematic review. Prev. Med. (Baltim.) 2018, 113, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braveman, P.; Egerter, S.; Barclay, C. Exploring the Social Determinants of Health; Income, Wealth and Health: San Fransisco, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Drewnowski, A.; Specter, S.E. Poverty and obesity: The role of energy density and energy costs. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 79, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinnon, L.; Giskes, K.; Turrell, G. The contribution of three components of nutrition knowledge to socio-economic differences in food purchasing choices. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 1814–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inglis, V.; Ball, K.; Crawford, D. Why do women of low socioeconomic status have poorer dietary behavior than women of higher socioeconomic status? A qualitative exploration. Appetite 2005, 45, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caraher, M.; Dixon, P.; Lang, T.; Carr-Hill, R. The state of cooking in England: The relationship of cooking skills to food choice. Br. Food J. 1999, 101, 590–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.S.; Winett, R.A.; Wojcik, J.R. Self-regulation, self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and social support: Social cognitive theory and nutrition behavior. Ann. Behav. Med. 2007, 34, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Panetta, G.; Leung, C.M.; Ging Wong, G.; Wang, J.C.K.; Chan, D.K.C.; Keatley, D.A.; Chatzisarantis, N.L.D. Chronic inhibition, self-control and eating behavior: Test of a resource depletion model. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e768888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Moubarac, J.C.; Cannon, G.; Ng, S.W.; Popkin, B. Ultra-processed products are becoming dominant in the global food system. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischhacker, S.E.; Evenson, K.R.; Rodriguez, D.A.; Ammerman, A.S. A systematic review of fast food access studies. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, e460–e471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macintyre, S.; Maciver, S.; Sooman, A. Area, class and health; should we be focusing on places or people? J. Soc. Policy 1993, 93, 213–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, H.; Gama, A.; Mourao, I.; Marques, V.R.; Padez, C. Pathways to childhood obesity: A deprivation amplification model and the overwhelming role of socioeconomic status. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2014, 191, 1697–1708. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J.; Scarborough, P.; Mattheews, A.; Cowburn, G.; Foster, C.; Roberts, N.; Rayner, M. A systematic review of the influence of the retail food environment around schools on obesity-related outcomes. Obes. Rev. 2014, 15, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engler-Stringer, R.; Le, H.; Gerrard, A.; Muhajarine, N. The community and consumer food environment and children’s diet: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Horst, K.; Oenema, A.; Ferreira, I.; Wendel-Vos, W.; Giskes, K.; van Lenthe, F.; Brug, J. A systematic review of environmental correlates of obesity-related dietary behaviors in youth. Health Educ. Res. 2007, 22, 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamba, R.J.; Schuchter, J.; Rutt, C.; Seto, E.Y.W. Measuring the food environment and its effects on obesity in the United States: A systematic review of methods and results. J. Commun. Health 2015, 40, 464–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobb, L.K.; Appel, L.J.; Franco, M.; Jones-Smith, J.C.; Nur, A.; Anderson, C.A.M. The relationship of the local food environment with obesity: A systematic review of methods, study quality, and results. Obesity 2015, 23, 1331–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustafson, A.; Hankins, S.; Jilcott, S. Measures of the consumer food store environment: A systematic review of the evidence 2000–2011. J. Commun. Heal. 2012, 37, 897–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, G.; Robinson, E.; Cameron, A.J. Issues in measuring the healthiness of food environments and interpreting relationships with diet, obesity and related health outcomes. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2019, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, N.; Story, M. A Review of Environmental Influences on Food Choices. Ann. Behav. Med. 2009, 38, S56–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bivoltsis, A.; Cervigni, E.; Trapp, G.; Knuiman, M.; Hooper, P.; Ambrosini, G.L. Food environments and dietary intakes among adults: Does the type of spatial exposure measurement matter? A systematic review. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2018, 17, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chennakesavalu, M.; Gangemi, A. Exploring the relationship between the fast food environment and obesity rates in the US vs. abroad: A systematic review. J. Obes. Weight Loss Ther. 2018, 8, 366. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi, C.E.; Sorensen, G.; Subramanian, S.V.; Kawachi, I. The local food environment and diet: A systematic review. Health Place 2012, 18, 1172–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, C.; Ntani, G.; Inskip, H.; Barker, M.; Cummins, S.; Cooper, C.; Moon, G.; Baird, J. Education and the Relationship Between Supermarket Environment and Diet. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 51, e27–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgoine, T.; Forouhi, N.G.; Griffin, S.J.; Brage, S.; Wareham, N.J.; Monsivais, P. Does neighborhood fast-food outlet exposure amplify inequalities in diet and obesity? A cross sectional study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 1540–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgoine, T.; Mackenbach, J.D.; Lakerveld, J.; Forouhi, N.G.; Griffin, S.J.; Brage, S.; Wareham, N.J.; Monsivais, P. Interplay of socioeconomic status and supermarket distance is associated with excess obesity risk: A UK cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, T.P. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIH (National Heart Lung and Blood Institute) Study Quality Assessment Tools. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 27 March 2019).

- Colchero, M.A.; Salgado, J.C.; Unar-Munguia, M.; Hernández-Ávila, M.; Rivera-Dommarco, J.A. Price elasticity of the demand for sugar sweetened beverages and soft drinks in Mexico. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2015, 19, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jilcott Pitts, S.B.; Wu, Q.; McGuirt, J.T.; Sharpe, P.A.; Rafferty, A.P. Impact on dietary choices after discount supermarket opens in low-income community. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2018, 50, 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, K.A.; Guilkey, D.K.; Ng, S.W.; Duffey, K.J.; Popkin, B.M.; Kiefe, C.I.; Steffen, L.M.; Shikany, J.M.; Gordon-Larsen, P. Sociodemographic differences in fast food price sensitivity. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rummo, P.E.; Meyer, K.A.; Boone-Heinonen, J.; Jacobs, D.R.J.; Kiefe, C.I.; Lewis, C.E.; Steffen, L.M.; Gordon-Larsen, P. Neighborhood availability of convenience stores and diet quality: Findings from 20 years of follow-up in the coronary artery risk development in young adults study. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, e65–e73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustafson, A.A.; Sharkey, J.; Samuel-Hodge, C.D.; Jones-Smith, J.; Folds, M.C.; Cai, J.; Ammerman, A.S. Perceived and objective measures of the food store environment and the association with weight and diet among low-income women in North Carolina. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 1032–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menezes, M.C.; Costa, B.V.; Oliveira, C.D.; Lopes, A.C. Local food environment and fruit and vegetable consumption: An ecological study. Prev. Med. Rep. 2016, 3, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, D.; Richards, R. Food store access and household fruit and vegetable use among participants in the US Food Stamp Program. Public Health Nutr. 2004, 7, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho-Rivera, M.; Rosenbaum, E.; Yama, C.; Chambers, E. Low-income housing rental assistance, perceptions of neighborhood food environment, and dietary patterns among Latino adults: The AHOME study. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2017, 4, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gase, L.N.; Glenn, B.; Kuo, T. Self-efficacy as a mediator of the relationship between the perceived food environment and healthy eating in a low income population in Los Angeles. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2016, 18, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jilcott Pitts, S.B.; Wu, Q.; Demarest, C.L.; Dixon, C.E.; Dortche, C.J.; Bullock, S.L.; McGuirt, J.; Ward, R.; Ammerman, A.S. Farmers’ market shopping and dietary behavior among Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program participants. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2407–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leischner, K.; McCormack, L.A.; Britt, B.C.; Heiberger, G.; Kattelman, K. The healthfulness of Entrées and Students’ Purchases in a University Campus Dining Environment. Healthcare 2018, 22, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, C.A.; Collins, R.; Ghosh-Dastidar, M.; Beckman, R.; Dubowitz, T. Does where you shop or who you are predict what you eat? The role of stores and individual characteristics in dietary intake. Prev. Med. (Baltim.) 2017, 100, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.; Ball, K.; Crawford, D. Why do some socioeconomically disadvantaged women eat better than others? An investigation of the personal, social and environmental correlates of fruit and vegetable consumption. Appetite 2010, 55, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beydoun, M.A.; Powell, L.M.; Wang, Y. The association of fast food, fruit and vegetable prices with dietary intakes among US adults: Is there modification by family income. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 66, 2218–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, R.; Surcke, M.; Jebb, S.A.; Pechey, R.; Almiron-Roig, E.; Marteau, T.M. Price promotions on healthier compared with less healthy foods: A hierarchical regression analysis of the impact on sales and social patterning of responses to promotions in Great Britain. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 806–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, L.M.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Y. Food prices and fruit and vegetable consumption among young American adults. Health Place 2009, 15, 1064–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrisinger, B.W.; Kallan, M.J.; Whiteman, E.D.; Hillier, A. Where do US householdse purchase healthy foods? An analysis of food-at-home purchases across different types of retailers in a nationally representative sample. Prev. Med. (Baltim.) 2018, 112, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duran, A.C.; De Almeida, S.L.; Latorre, M.D.R.D.; Jaime, P.C. The role of the local retail food environment in fruit, vegetable and sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in Brazil. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jack, D.; Neckerman, K.; Schwartz-Soicher, O.; Lovasi, G.S.; Quinn, J.; Richards, C.; Bader, M.; Weiss, C.; Konty, K.; Arno, P.; et al. Socio-economic status, neighborhood food environments and consumption of fruits and vegetables in New York City. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 1197–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInerney, M.; Csizmadi, I.; Friedenreich, C.M.; Uribe, F.A.; Nettel-Aguirre, A.; McLaren, L.; Potestio, M.; Sandalack, B.; McCormack, G.R. Associations between the neighborhood food environment, neighborhood socioeconomic status, and diet quality: An observational study. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, C.; Lewis, D.; Ntani, G.; Cummins, S.; Cooper, C.; Moon, G.; Baird, J. The relationship between dietary quality and the local food environment differs according to level of educational attainment: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenk, S.N.; Lachance, L.L.; Schulz, A.J.; Mentz, G.; Kannan, S.; Ridella, W. Neighborhood Retail Food Environment and Fruit and Vegetable Intake in a Multiethnic Urban Population. Am. J. Health Promot. 2009, 23, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jilcott Pitts, S.B.; Wu, Q.; Sharpe, P.A.; Rafferty, A.P.; Elbel, B.; Ammerman, A.S.; Payne, C.R.; Hopping, B.N.; McGuirt, J.T.; Wall-Bassett, E.D. Preferred Healthy Food Nudges, Food Store Environments, and Customer Dietary Practices in 2 Low-Income Southern Communities. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2016, 48, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, S.; Wimer, C.; Seligman, H. Moderation of the relation of county-level cost of living to nutrition by the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 2064–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bihan, H.; Méjean, C.; Castetbon, K.; Faure, H.; Ducros, V.; Sedeaud, A.; Galan, P.; Le Clésiau, H.; Péneau, S.; Hercberg, S. Impact of fruit and vegetable vouchers and dietary advice on fruit and vegetable intake in a low-income population. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 66, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blitstein, J.L.; Snider, J.; Evans, W.D. Perceptions of the food shopping environment are associated with greater consumption of fruits and vegetables. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 1124–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubowitz, T.; Zenk, S.N.; Ghosh-Dastidar, B.; Cohen, D.A.; Beckman, R.; Hunter, G.; Steiner, E.D.; Collins, R.L. Healthy food access for urban food desert residents: Examination of the food environment, food purchasing practices, diet and BMI. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2220–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gase, L.N.; DeFosset, A.R.; Smith, L.V.; Kuo, T. The association between self-reported grocery store access, fruit and vegetable intake, sugar-sweetened beverage consumption, and obesity in a racially diverse, low-income population. Front. Public Health 2014, 11, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Angelo, H.; Suratkar, S.; Song, H.J.; Stauffer, E.; Gittelsohn, J. Access to food source and food source use are associated with healthy and unhealthy food-purchasing behavior among low-income African-American adults in Baltimore City. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 1632–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, L.D.; McNaughton, S.A.; Crawford, D.; MacFarlane, A.; Ball, K. Correlates of dietary resilience among socioeconomically disadvantaged adolescents. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 65, 1219–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, L.M.; Han, E. The costs of food at home and away from home and consumption patterns among U.S. adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2011, 48, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeredo, C.M.; de Rezende, L.F.; Canella, D.S.; Claro, R.M.; Peres, M.F.; Luiz Odo, C.; Franca-Junior, I.; Kinra, S.; Hawkesworth, S.; Levy, R.B. Food environments in schools and in the immediate vicinity are associated with unhealthy food consumption among Brazilian adolescents. Prev. Med. (Baltim.) 2016, 88, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longacre, M.R.; Drake, K.M.; Titus, L.J.; Peterson, K.E.; Beach, M.L.; Langeloh, G.; Hendricks, K.; Dalton, M.A. School food reduces household income disparities in adolescents’ frequency of fruit and vegetable intake. Prev. Med. (Baltim.) 2014, 69, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Vericker, T.C. Limited evidence that competitive food and beverage practices affect adolescent consumption behaviors. Heal. Educ. Behav. 2012, 40, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virtanen, M.; Kivimaki, H.; Ervasti, J.; Oksanen, T.; Pentti, J.; Kouvonen, A.; Halonen, J.I.; Kivimaki, M.; Vahtera, J. Fast-food outlets and grocery stores near school and adolescents’ eating habits and overweight in Finland. Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 650–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, S.Y.; Wong, B.Y.; Lo, W.S.; Mak, K.K.; Thomas, G.N.; Lam, T.H. Neighbourhood food environment and dietary intakes in adolescents: Sex and perceived family affluence as moderators. Int. J. Pediatr. Obes. 2010, 5, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, K.L.; Zastrow, M.; Zdorovtsov, C.; Quast, R.; Skjonsberg, L.; Stluka, S. Do SNAP and WIC programs encourage more fruit and vegetable intake? A household survey in the Northern Great Plains. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2015, 36, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strome, S.; Johns, T.; Scicchitano, M.J.; Shelnutt, K. Elements of access: The effects of food outlet proximity, transportation, and realized access of fresh fruit and vegetable consumption in food deserts. Int. Q. Commun. Health Educ. 2016, 37, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustafson, A. Shopping pattern and food purchase differences among Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) households and Non-supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program households in the United States. Prev. Med. Rep. 2017, 7, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macdonald, L.; Ellaway, A.; Ball, K.; Macintyre, S. Is proximity to a food retail store associated with diet and BMI in Glasgow, Scotland? BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, J.; Hiscock, R.; Blakely, T.; Witten, K. The contextual effects of neighborhood access to supermarkets and convenience stores on individual fruit and vegetable consumption. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2008, 62, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranjit, N.; Wilkinson, A.V.; Lyttle, L.M.; Evans, A.E.; Saxton, D.; Hoelscher, D.M. Socioeconomic inequalities in children’s diet: The role of the home food environment. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thow, A.M.; Downs, S.; Jan, S. A systematic review of the effectiveness of food taxes and subsidies to improve diets: Understanding the recent evidence. Nutr. Rev. 2014, 72, 551–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornelsen, L.; Green, R.; Turner, R.; Dangour, A.D.; Shankar, B.; Mazzocchi, M.; Smith, R.D. What happens to patterns of food consumption when food prices change? Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis of food price elasticities globally. Health Econ. 2015, 24, 1548–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackenbach, J.D.; Lakerveld, J.; Generaal, E.; Gibson-Smith, D.; Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Beulens, J.W.J. Local fast-food environment, diet and blood pressure: The moderating role of mastery. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkins, E.L.; Morris, M.A.; Radley, D.; Griffiths, C. Using Geographic Information Systems to measure retail food environments: Discussion of methodological considerations and a proposed reporting checklist (Geo-FERN). Health Place 2017, 44, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).