Abstract

Metabolic Syndrome (MetS) constitutes a relevant public health burden. Several studies have demonstrated the association between diet and MetS. We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to provide an estimate of the association between dietary patterns defined through a posteriori methods and MetS. A literature search on PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus databases, up to March 2019, was conducted to identify all eligible case-control, prospective, or cross-sectional studies involving adult subjects of both sexes. Random-effects models were used. Heterogeneity and publication bias were evaluated. Stratified analyses were conducted on study characteristics. Forty observational studies were included in the meta-analysis, which identified the “Healthy” and the “Meat/Western” dietary patterns. The “Healthy” pattern was associated with reduced MetS risk (OR = 0.85; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.79–0.91) and significantly decreased the risk in both sexes and in Eastern countries, particularly in Asia. Adherence to the “Meat/Western” pattern increased MetS risk (OR = 1.19; 95% CI: 1.09–1.29) and the association persisted in the stratified analysis by geographic area (Asia, Europe, America) and study design. Lifestyle is linked to risk of developing MetS. The “Healthy” and “Meat/Western” patterns are significantly associated with reduced and increased MetS risk, respectively. Nutrition represents an important modifiable factor affecting MetS risk.

1. Introduction

Metabolic Syndrome (MetS) has become a relevant public health concern [1] because of its increased prevalence partially explained by aging population and lifestyle factors, including diet [2,3].

MetS is a pathophysiological state and a cluster of interrelated factors including abdominal obesity, insulin resistance, dysglycemia, hypertension, and dyslipidemia (triglycerides and HDL-C—high-density lipoprotein cholesterol) [4]. The diagnosis of MetS requires three or more of the following criteria: (i) waist circumference >102 cm in men and >88 cm in women; (ii) HDL-C <40 mg/dL (<1.04 mmol/L) in men and <50 mg/dL (<1.29 mmol/L) in women; (iii) triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL (≥1.7 mmol/L); (iv) blood pressure ≥130/85 mmHg and (v) fasting glucose ≥110 mg/dL (≥6.1 mmol/L) [4,5]. A harmonization of the diagnostic criteria has been proposed, as the reference thresholds for abdominal obesity vary considerably among countries and international organizations [4]. In particular, the recommended waist circumference cutoff points are lower for both men and women in Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Central and South America [4].

According to literature, the consumption of specific foods or nutrients is strongly related to the risk of developing MetS [6,7,8,9]. Nutritional epidemiology currently applies dietary patterns to analyze the relation of diet with chronic diseases rather than focusing on individual foods and nutrients [10,11]. Dietary patterns provide a closer representation of the overall dietary habits of the population in study. The statistical methods identifying dietary patterns are distinguished in a priori and a posteriori methods. A priori approaches assign dietary indices and scores (i.e., glycemic index, Mediterranean score) based on current nutritional knowledge of positive and negative effects of various nutrients or foods and identify an optimal pattern, the adherence to which could maximize health benefit. The a priori approach can prove more advantageous only if important dietary factors have been clearly defined to affect the outcome under study [10,12]. Conversely, a posteriori methods identify dietary patterns (i.e., Western and Healthy patterns) based on available dietary data directly obtained from the studied population [10]. Their major limit is that the identified dietary pattern may be sample specific and influenced by subjective decisions [10,12]. The association of MetS outcomes with a priori patterns, such as the Mediterranean diet and inflammatory diet, have been analyzed. The Mediterranean diet reduced the risk of MetS, whereas the comparison of the most pro-inflammatory diet versus the most anti-inflammatory diet showed no significant association [13,14]. A recent meta-analysis [15] had evaluated the relationship between a posteriori dietary patterns and MetS and showed a risk reduction of 11% for prudent/healthy pattern and a risk increase of 16% for Western/unhealthy pattern. A previous meta-analysis [16], found that an inverse association of prudent/healthy pattern and a positive association of Western/unhealthy pattern with MetS in cross-sectional studies, but not in cohort studies. Since then several other studies have been published on this topic with contrasting results. Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis for deriving a more precise estimation of this association.

The aim of our systematic review and meta-analysis is to investigate and provide an estimate of the association between dietary patterns defined by a posteriori methods and MetS risk in adults.

2. Materials and Methods

The present meta-analysis was conducted following the MOOSE (Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines [17] and PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement [18].

2.1. Search Strategy and Data Source

We conducted a comprehensive literature search, without restrictions, up to 31 March 2019 through PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/), Web of Science (http://wokinfo.com/) and Scopus (https://www.scopus.com/) databases to identify all the original articles on the association between dietary patterns and MetS. The literature search included the following search medical subject headings (MeSH) and key words: (“Metabolic Syndrome” OR MetS) AND (“dietary pattern” OR “eating pattern” OR “food pattern” OR “dietary habit” OR “dietary score” OR “dietary index” OR "nutrient pattern” OR “diet diversity” OR “diet variety” OR “diet quality” OR “diet index” OR “diet score”) AND (“factor analysis” OR “principal component analysis” OR “cluster analysis” OR clustering OR “reduced rank regression” OR “data-driven approach” OR “a posteriori method”).

We manually examined the reference lists of selected articles and recent relevant reviews to identify possible additional relevant publications.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Articles were included if they met the following criteria: (i) evaluated the relationship between dietary patterns derived by a posteriori methods, such as principal component analysis (PCA), factor analysis (FA), and principal component factor analysis (PCFA), and by reduced rank regression (RRR, i.e., an integration of the a priori and the a posteriori approaches) and MetS in adults; (ii) used a case-control, prospective or cross-sectional study design; (iii) reported odds ratio (OR), relative risk (RR) or hazard ratio (HR) estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For each potentially included study, two investigators independently carried out the selection, data abstraction, and quality assessment. Disagreements were resolved by discussion or in consultation with the third author. Although useful to have background information, reviews and meta-analysis were excluded. No studies were excluded for weakness of design or data quality.

2.3. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

For each selected study, we extracted the following information: first author’s last name, year of publication, country, study design, sample size (when possible, number of cases and controls; cohort size and incident cases), population characteristics (sex, age), duration of follow-up for cohort studies, MetS assessment method, dietary assessment and dietary pattern identification methods (FA, PCA and PCFA), characteristics of the dietary assessment method, name given to the dietary patterns and their characteristics, cutoff points of the different categories of adherence to the dietary pattern (dichotomy, tertile, quartile and quintile), risk estimates with 95% CIs for the different categories of adherence, p-value for trend, and confounding factors adjustment. When multiple estimates were reported in the article, we pulled out those adjusted for the most confounding factors.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The estimated overall effect-size statistic was the average of the logarithm of the observed OR (approximated to RR, when necessary) associated with the highest versus the lowest level of adherence to the different dietary patterns. We used the random-effects model to calculate the summary OR and 95% CIs. We restricted the analysis to the dietary patterns defined a posteriori. Since the labeling of the patterns is arbitrary and the dietary patterns are population-specific, we considered only those patterns sharing most foods with similar factor loadings. For the inclusion in the meta-analysis, the two most common dietary patterns with similar factor loading of principle components were identified in 38 studies (out of 40) [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. The first dietary pattern, named “Healthy”, was characterized by a high loading of vegetables and fruit, poultry, fish, and whole grains. The selected articles labeled this pattern as “Healthy” [22,24,26,27,32,36,43,51,52,54,55,58], “Healthy Japanese” [35], “Health-conscious” [44], “Prudent” [28,31,33,37,46,47,50], “Balanced” [19,25], “Fruit & vegetables” [20,57], “Vegetables, fruits, cereals, and tubers” [42], “Traditional Chinese” [56], “Minimally processed/processed” [21], “Mixed-traditional” [23], “Fruits, vegetables, nuts, and legumes” [29], “Refined Grains & Vegetables” [30], “Traditional” [34,49], “Traditional Lebanese” [38], “Balanced Korean” [39], “Fruit and dairy” [40], “Grains, vegetables, and fish” [45].

The second dietary pattern, named “Meat/Western”, had a high loading of red meat, processed meat, animal fat, eggs and sweets. The included articles labeled this pattern as “Western” [19,20,28,31,43,46,50,51,53,54,58], “Traditional and protein” [42], “Unhealthy” [36,55], “Animal food” [56], “Common Brazilian meal” [57], “Ultra-processed” [21], “Westernized” [24,32], “Mixed-modern” [23], “High-protein/cholesterol” [25], “Meat” [26,34], “Refined and Processed” [27], “Animal protein” [29], “Organ Meat & Poultry” [30], “Fat, meat and alcohol” [32], “High-fat/Western” [33], “Animal food” [35], “Southern” [37], “High-Protein” [38], “Semi-Western” [39], “Alcohol and meat” [40,45], “Processed foods” [44], “High-protein/fat” [47], “Meat and French fries” [49], “High glycemic index and high-fat” [52].

The chi-square-based Cochran’s Q statistic and the I2 statistic were used to evaluate heterogeneity in results across studies [59]. The I2 statistic yields results ranged from 0% to 100% (I2 = 0%–25%, no heterogeneity; I2 = 25%–50%, moderate heterogeneity; I2 = 50%–75%, large heterogeneity; and I2 = 75%–100%, extreme heterogeneity) [60]. Results of the meta-analysis may be biased if the probability of publication is dependent on the study results. We used the methods of Begg and Mazumdar [61] and Egger et al. [62] to detect publication bias. Both methods tested for funnel plot asymmetry, the former being based on the rank correlation between the effect estimates and their sampling variances, and the latter on a linear regression of a standard normal deviate on its precision. If a potential bias was detected, we further conducted a sensitivity analysis to assess the robustness of combined effect estimates, and the possible influence of the bias, and to have the bias corrected. We also conducted a sensitivity analysis to investigate the influence of a single study on the overall risk estimate, by omitting one study in each turn. We considered the funnel plot to be asymmetrical, if the intercept of Egger’s regression line deviated from zero, with a p-value of <0.05. The analyses were performed using the ProMeta Version 3.0 statistical program (Internovi, Via Cervese, 47522, Cesena, Italy).

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

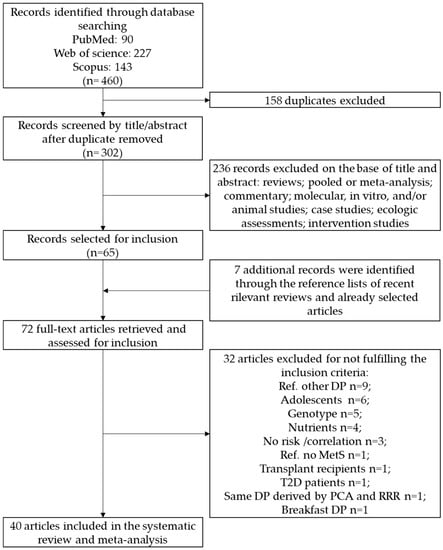

The primary literature search through PubMed (n = 90), Web of Science (n = 227) and Scopus (n = 143) databases identified a total of 460 articles. Duplicates (n = 158) were removed and the remaining 302 records were identified for title and abstract revision (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the systematic literature search on dietary patterns and MetS risk. Metabolic Syndrome (MetS).

Among these, 236 articles were excluded as not investigating the association between dietary patterns and the outcome of interest. Sixty-five articles were subjected to full-text revision. Hand searching of reference lists of both selected articles and recent relevant reviews led to the identification of seven additional items. Subsequently, 32 papers were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria as follows: 9 studies considered a different dietary pattern as the comparison reference; 6 studies were carried out on adolescents; 5 studies reported the MetS risk combined with genotype; 4 studies derived the dietary patterns considering nutrients instead of food items; 3 studied reported the correlation instead of risk estimate; one study used a control group (no MetS) as reference; one study was carried out on transplant recipients; and one study was carried out on type 2 diabetes. Therefore, at the end of the selection process, 40 studies were enclosed for the identification of the different dietary patterns in the systematic review and meta-analysis [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58].

3.2. Study Characteristics and Quality Assessment

General characteristics of the 40 studies evaluating the association between adherence to a posteriori dietary patterns with MetS risk are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis on dietary patterns and Metabolic Syndrome.

These studies were published between 2007 and 2019. Eight studies were conducted in Korea [24,28,34,36,39,40,43,45], eight in Europe [20,22,31,32,41,44,52,53]; six in Iran [19,46,51,54,55,58]; four in the USA [29,37,49,50]; three in China [25,30,56]; two in Japan [33,35], Brazil [42,57], Samoan Islands [23,48] and Lebanon [21,38]; and one each in Thailand [26], Australia [27] and Mexico [47]. Four were cohort studies [36,50,53,54], one was a case-control study [25] and all others were cross-sectional studies. Six studies were conducted on women and men separately [24,26,30,34,39,41], three were on women only [28,43,51] and all others estimated the MetS risk on women and men together. One study did not report the parameters used to identify the MetS [29].

Thirty-one studies used a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ; 43 to 168 items) [19,20,21,22,23,25,26,28,29,31,32,33,34,36,37,38,42,43,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58] while six studies used a 24-h dietary recall [24,27,30,39,40,45] to collect dietary information. In addition, three studies used a diet history questionnaire [35], 3-day food diary [41] and 4 weeks face-to-face dietary history interview [44], respectively. One study [53] derived dietary patterns through RRR, another study [48] used a “partial least squares regression” method, while all the other studies derived dietary patterns through a posteriori methods (PCA, PCFA, and FA). Nine studies [21,31,36,41,44,51,52,53,55] reported the association of MetS risk with two different dietary patterns, 24 studies [19,20,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,34,35,37,38,39,42,43,47,48,49,50,54,56,58] considered three different dietary patterns, six studies [30,32,33,40,45,57] considered four different dietary patterns and one study [46] considered five different dietary patterns.

3.3. Meta-Analysis

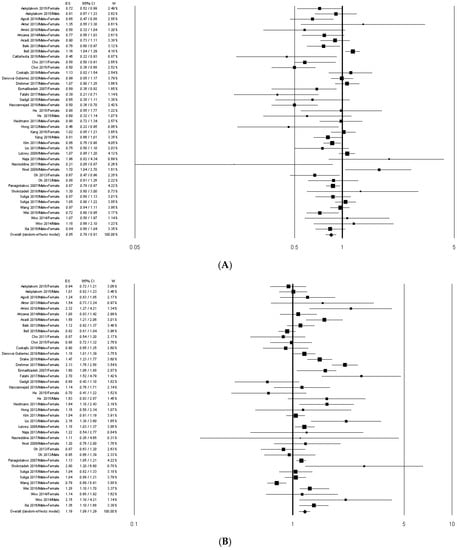

We identified two common dietary patterns with similar factor loading of principle components: “Healthy” and “Meat/Western” patterns. Thirty-eight out of 40 articles included in the systematic review were used for the overall risk estimation. Two studies [41,48] were excluded because they reported dietary patterns that could not be clearly assumed in “Healthy” nor in “Meat/Western” patterns. In the studies by Agodi et al. [31] and by Wang et al. [23], the “Healthy” dietary pattern was the only pattern identified, whereas in the study by Cattafesta et al. [42] the “Meat/Western” was the only pattern selected. The meta-analyses on the MetS risk in association with “Healthy” and “Meat/Western” dietary patterns (studies comparing the highest intake to the lowest intake) are shown in Figure 2A,B, respectively.

Figure 2.

Forest plots of the association between “Healthy” (A) and “Meat/Western” (B) dietary patterns and MetS risk. ES, effect size.

The overall analysis showed that the MetS risk significantly decreased in association with the adherence to the “Healthy” pattern (OR = 0.85; 95% CI: 0.79–0.91) and significantly increased in association with the adherence to the “Meat/Western” pattern (OR = 1.19; 95% CI: 1.09–1.29). These results did not essentially change when the studies [27,33,52] not comparing the highest vs. the lowest dietary pattern adherence values were excluded (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of stratified analysis of the Metabolic Syndrome risk estimates for the highest compared with the lowest intake categories of “Healthy” and “Meat/Western” dietary patterns a,b.

In the “Healthy” pattern meta-analysis, the stratification by study design showed a significant reduced MetS risk in the cross-sectional studies only (Table 2). Stratifying the analysis by geographic area, MetS risk decreased significantly in Eastern countries (OR = 0.78; 95% CI: 0.71–0.86), particularly in Asia (OR = 0.77; 95% CI: 0.70–0.85). The preventive effect of the “Healthy” pattern resulted statistically significant in both sexes (Table 2).

In the “Meat/Western” pattern meta-analysis, the stratification by study design showed a significantly higher MetS risk in both cohort and cross-sectional studies (Table 2). Similarly, when stratifying the analysis by the geographic area the MetS risk significantly increased in Asia, America and Europe, and in Eastern and Western countries (Table 2). No significant association was found when stratifying by sex (Table 2).

The high heterogeneity in the pooled analysis of both “Healthy” and “Meat/Western” patterns was slightly reduced in the stratification by geographic area.

Sensitivity analyses suggested that the estimates were not substantially modified by any single study. Small changes were found in the risk estimates after removal of the outlier studies by Naja et al. [38] (OR = 0.84; 95% CI: 0.78–0.91) and by Nasreddine et al. [21] (OR = 0.85; 95% CI: 0.79–0.92) in the “Healthy” pattern analysis, and by Shokrzadeh et al. [55] (OR = 1.20; 95% CI: 1.09–1.32) and by Gadgil et al. [29] (OR = 1.23; 95% CI: 1.11–1.35) in the “Meat/Western” pattern analysis.

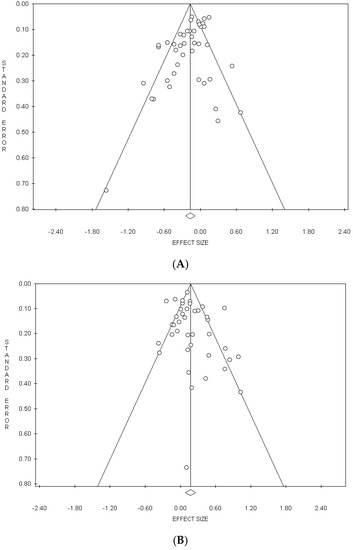

In the meta-analysis on the “Healthy” pattern, a significant publication bias was detected by the Egger’s test in the overall analysis (p = 0.005) and in cross-sectional studies (p = 0.016), but not by the Begg’s method (Table 2). In the analysis performed excluding the studies by Bell et al. [27], by Arisawa et al. [33] and by Panagiotakos et al. [52], the publication bias, although reduced, remained significant (p = 0.011) (Table 2). In the meta-analysis on “Meat/Western” pattern, a significant publication bias was detected by Egger’s method in the Eastern countries (p = 0.021) and by the Begg’s test in men (p = 0.042) (Table 2).

The funnel plots of the meta-analyses on the “Healthy” pattern and on the “Meat/Western” pattern are shown in Figure 3A,B, respectively.

Figure 3.

Funnel plots of the meta-analyses on the Healthy” (A) and “Meat/Western” (B) dietary patterns.

4. Discussion

Our systematic review and meta-analysis investigated the effect of dietary patterns extracted via a posteriori methods on MetS risk. According to literature, several different health outcomes are associated with unhealthy and healthy dietary patterns. In particular, the Western/unhealthy pattern increases the risk of cancer in different sites [63,64,65,66,67,68] and the risk of low bone mineral density and osteoporotic fracture [69]. Moreover, the prudent/healthy pattern is associated with lower risk of cardiovascular disease and coronary heart disease [70], diabetes mellitus [71,72], and cognitive decline and dementia [73].

Considering the 40 included articles, we identified two prevalent dietary patterns: “Healthy” and “Meat/Western”. The “Healthy” pattern was associated with a lower MetS risk and significantly decreased the risk in both sexes and in Eastern countries, particularly in Asia. Adherence to the “Meat/Western” pattern was positively associated with MetS risk and this association persisted in the stratified analysis by geographic area and study design. Similarly, the recent meta-analyses by Shab–Bidar et al. [15] and Rodríguez–Monforte et al. [16] showed that a Western/unhealthy pattern significantly increased MetS risk, whereas a prudent/healthy pattern significantly lowered MetS risk. In our study, MetS risk through unhealthy dietary patterns increased by 19%, while it increased by 22% in the study by Shab–Bidar et al. [15] and by 28% in the study by Rodríguez–Monforte et al. [16]. Healthy dietary patterns significantly decreased MetS risk by 15% in our analysis, by 11% in the meta-analysis by Shab–Bidar et al. [15] and by 17% in the meta-analysis by Rodríguez–Monforte et al. [16]. It should be noted that the meta-analysis of Shab–Bidar et al. [15] was performed on cross-sectional studies only and that Rodríguez–Monforte et al. [16] selected 31 studies including those which identified the dietary patterns via cluster analysis (a priori method).

According to our findings, the “Meat/Western” pattern significantly increased MetS risk of 20% in Asia, 15% in Europe and 33% in America. In dietary patterns derived a posteriori, the factor loadings indicate the most commonly consumed foods, reflecting the cultural influence on food consumption [74,75]. It is noteworthy that the usual diet of European populations, especially in Mediterranean countries, tend to include the consumption of healthy foods, such as seafood, vegetables, and fruit, whereas American populations mostly adhere to Westernized dietary patterns, containing high pro-inflammatory foods [76]. As reported in the study by Calton et al. [77], other pre-defined representative dietary patterns exist worldwide, such as the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet, which is characterized by high intake of fruit, vegetables, whole grains and dairy [78], and the Northern Europe dietary pattern, which is characterized by high intake of fruit, vegetables, legumes, low-fat dairy, fatty fish, oats, barley and almonds [79]. These patterns can affect MetS risk and should be evaluated when investigating the effect of the dietary patterns on developing MetS, as culture and society influence adherence to healthy or unhealthy dietary pattern [77]. Our study combined dietary patterns derived a posteriori from world countries with very different eating habits, in particular, traditional dietary patterns from Eastern Asian countries (Japan [33,35], China [25,30,56], Korea [24,28,34,36,39,40,43,45]), from Western Asian countries (Iran [19,46,51,54,55,58]), from the Mediterranean area (Greece [52], Lebanon [21,38]), from Northern Europe (Sweden [53]), from Middle Europe (Germany [44], Czech Republic [31] and Poland [20,22,32]), from North America (USA [29,37,49,50]), from South America (Brazil [42,57]), and from Australia [27]. Indeed, the traditional dietary pattern in Asian countries is characterized by high intake of rice and/or kimchi, fish and sea food, soybean and soybean products, mushrooms, vegetables, and fruit [24,28,34,39,40,43,56], in Poland by red meat, fish, potatoes, soup, refined grains and sugars, and high-fat milk [20,22], and in Iran by refined grains, nuts, eggs, vegetables and legumes, potatoes, and hydrogenated fats [51,58].

Despite the influence of sex-related factors on MetS [80], we observed no sex-related difference on the association of dietary pattern with MetS, but, notably, the “Healthy” pattern showed a stronger protective effect in women.

The “Meat/Western” pattern, characterized by high intake or red and processed meat, eggs, refined grains, and sweets, resulted associated with an increased (+19%) MetS risk. These foods plausibly represent the main cause of the observed effect on MetS risk, particularly meat [81,82], since refined carbohydrates, red and processed meats, and fried foods have pro-inflammatory properties and can increase inflammatory cytokines [83]. Indeed, although the meta-analysis by Namazi et al. [14] found no significant association between the most pro-inflammatory diet and MetS, inflammatory factors are involved in insulin resistance and lipid disorders [83].

Our results showed the association of the “Healthy” pattern with a lower (−15%) MetS risk. The healthy patterns are characterized by the consumption of foods with high content of vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, fiber, MUFA and n-3 fatty acids, which could contribute to explain the protective effect of the “Healthy” pattern on MetS. Indeed, higher adherence to healthy dietary patterns is associated with a lower risk of glucose intolerance, weight gain, inflammation, insulin resistance and a higher level of HDL cholesterol [84].

Limitations

The main limitation of our study is that the risk of developing MetS could be associated with dietary patterns other than the two (“Healthy” and “Meat/Western”) discussed in this meta-analysis. Differences in the populations in study and in the referral values for MetS diagnosis represent another study limitation and result in heterogeneity. Indeed, the high heterogeneity may be related to the wide variability in dietary data collection and analysis, in the various and not uniformly adjusted confounding factors, and in the identification of the dietary patterns. Heterogeneity is more evident in the analysis on “Meat/Western” pattern, as a possible consequence of the difficulty in characterizing this pattern across the selected studies. Another limitation is that pooled data were directly driven by the included studies, presenting their own weaknesses in study design. Moreover, the cross-sectional nature of many included studies precludes causal inference and the dietary pattern may represent a post hoc event. Only the OR of the highest and the lowest quantile of healthy or unhealthy dietary patterns were included in our analysis, limiting the evaluation of the presence of any trend. Finally, some studies reported risk estimates for quintiles, others for quartiles, and others for tertiles. As dietary intakes are influenced by sex, race/ethnicity, and societal factors, our findings should be considered in the different geographic contexts. Thus, these aspects may have affected the reproducibility of the association between dietary patterns and MetS.

To further advance this field of research, future studies are needed to examine the association between dietary patterns in geographic context not yet described and MetS, and to evaluate the impact of dietary patterns on the determinants of MetS.

5. Conclusions

A protective effect on MetS is attributed to adherence to the “Healthy” pattern, which is characterized by high consumption of fruit, vegetables, whole grains, poultry, fish, nuts, legumes, and low-fat dairy products, whereas the “Meat/Western” pattern is positively associated with MetS. Nutrition is one of the most important modifiable factors affecting health. Public health efforts should aim to adopt healthy dietary patterns and to reduce the burden of MetS, providing guidance for nutritional intervention. For further advance in research, more prospective studies are needed to investigate the association between dietary patterns and MetS in each gender and in different geographic context.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Initiated by R.F., agreed by all other authors M.C. and G.N.; Methodology: from literature search to meta-analysis, R.F., M.C. and G.N.; Formal analysis: meta-analysis, R.F.; Data curation: M.C. and G.N.; Writing—original draft preparation, R.F., M.C. and G.N.; Writing—review and editing, R.F., M.C. and G.N.; Supervision, M.C.; Project administration, R.F.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- Saklayen, M.G. The Global Epidemic of the Metabolic Syndrome. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2018, 20, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scuteri, A.; Najjar, S.S.; Morrell, C.H.; Lakatta, E.G. The metabolic syndrome in older individuals: Prevalence and prediction of cardiovascular events: The cardiovascular health study. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 882–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberopoulos, E.N.; Mikhailidis, D.P.; Elisaf, M.S. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome in obesity. Obes. Rev. 2005, 6, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberti, K.G.M.M.; Eckel, R.H.; Grundy, S.M.; Zimmet, Z.P.; Cleeman, J.I.; Donato, K.A.; Fruchart, J.-C.; James, W.P.; Loria, C.M.; Smith, S.C., Jr. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: A joint interim statement of the international diabetes federation task force on epidemiology and prevention; National heart, lung, and blood institute; American heart association; World heart federation; International. Circulation 2009, 120, 1640–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) Final Report. Circulation 2002, 106, 3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julibert, A.; Bibiloni, M.D.M.; Mateos, D.; Angullo, E.; Tur, J.A. Dietary Fat Intake and Metabolic Syndrome in Older Adults. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Martínez, P.; Mikhailidis, D.P.; Athyros, V.G.; Bullo, M.; Couture, P.; Covas, M.I.; de Koning, L.; Delgado-Lista, J.; Díaz-López, A.; Drevon, C.A.; et al. Lifestyle recommendations for the prevention and management of metabolic syndrome: An international panel recommendation. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasaki, Y.; Arisawa, K.; Katsuura-Kamano, S.; Uemura, H.; Tsukamoto, M.; Kadomatsu, Y.; Okada, R.; Hishida, A.; Tanaka, K.; Hara, M.; et al. Associations of nutrient patterns with the prevalence of metabolic syndrome: Results from the baseline data of the Japan multi-institutional collaborative cohort study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutt, S.J.; Jokelainen, J.; Sebert, S.; Auvinen, J.; Järvelin, M.; Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi, S.; Herzig, K. Vitamin D Status and Components of Metabolic Syndrome in Older Subjects from Northern Finland (Latitude 65° N). Nutrients 2019, 11, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.B. Dietary pattern analysis: A new direction in nutritional epidemiology. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2002, 13, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michels, K.B.; Schulze, M.B. Can dietary patterns help us detect diet-disease associations? Nutr. Res. Rev. 2005, 18, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacques, P.F.; Tucker, K.L. Are dietary patterns useful for understanding the role of diet in chronic disease? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 73, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godos, J.; Zappalà, G.; Bernardini, S.; Giambini, I.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet is inversely associated with metabolic syndrome occurrence: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 68, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namazi, N.; Larijani, B.; Azadbakht, L. Dietary Inflammatory Index and its Association with the Risk of Cardiovascular Diseases, Metabolic Syndrome, and Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta—Analysis. Horm. Metab. Res. 2018, 50, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shab-Bidar, S.; Golzarand, M.; Hajimohammadi, M.; Mansouri, S. A posteriori dietary patterns and metabolic syndrome in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 1681–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Monforte, M.; Sánchez, E.; Barrio, F.; Costa, B.; Flores-Mateo, G. Metabolic syndrome and dietary patterns: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 56, 925–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroup, D.F.; Berlin, J.A.; Morton, S.C.; Olkin, I.; Williamson, G.D.; Rennie, D.; Moher, D.; Becker, B.J.; Sipe, T.A.; Thacker, S.B.; et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: A proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000, 283, 2008–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asadi, Z.; Shafiee, M.; Sadabadi, F.; Maryam, S.; Susan, D.; Maryam, T.; Hamideh, G.; Alireza Heidari, B.; Mohsen, M.; Habibollah, E.; et al. Association of dietary patterns and the risk of metabolic syndrome among Iranian population: A cross-sectional study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2019, 13, 858–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czekajło, A.; Rózańska, D.; Zatońska, K.; Szuba, A.; Regulska-Ilow, B. Association between dietary patterns and metabolic syndrome in the selected population of Polish adults—Results of the PURE Poland Study. Eur. J. Public Health 2019, 29, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, L.; Tamim, H.; Itani, L.; Nasrallah, M.P.; Isma’eel, H.; Nakhoul, N.F.; Abou-Rizk, J.; Naja, F. A minimally processed dietary pattern is associated with lower odds of metabolic syndrome among Lebanese adults. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suliga, E.; Kozieł, D.; Cieśla, E.; Rębak, D.; Głuszek, S. Dietary patterns in relation to metabolic syndrome among adults in Poland: A cross-sectional study. Nutrients 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Hawley, N.L.; Thompson, A.A.; Lameko, V.; Reupena, M.S.; McGarvey, S.T.; Baylin, A. Dietary Patterns Are Associated with Metabolic Outcomes among Adult Samoans in a Cross—Sectional Study. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 628–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.; Kim, J. Gender difference on the association between dietary patterns and metabolic syndrome in Korean population. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016, 55, 2321–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Y.; Gu, Y.; Yu, F.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, L.; Meng, G.; Wu, H.; Du, H.; Shi, H.; Guo, X.; et al. Association between dietary patterns and metabolic syndrome in Chinese adults: A propensity score-matched case-control study. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aekplakorn, W.; Satheannoppakao, W.; Putwatana, P.; Taneepanichskul, S.; Kessomboon, P.; Chongsuvivatwong, V.; Chariyalertsak, S. Dietary Pattern and Metabolic Syndrome in Thai Adults. J. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, L.K.; Edwards, S.; Grieger, J.A. The relationship between dietary patterns and metabolic health in a representative sample of adult Australians. Nutrients 2015, 7, 6491–6505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.H.; Woo, H.D.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, J. Dietary Patterns and Risk for Metabolic Syndrome in Korean Women. Medicine 2015, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadgil, M.D.; Anderson, C.A.; Kandula, N.R.; Kanaya, A.M. Dietary Patterns Are Associated with Metabolic Risk Factors in South Asians Living in the United States. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 1211–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.H.; Zhu, X.H.; Yang, M.; Ma, X.G.; Huang, L.C.; Huang, E.S.; Gu, W.; Zhu, Y.B.; Zhao, D.; Zhu, X.H.; et al. Dietary patterns associated metabolic syndrome in Chinese adults. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2015, 28, 370–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agodi, A.; Maugeri, A.; Kunzova, S.; Sochor, O.; Bauerova, H.; Kiacova, N.; Barchitta, M.; Vinciguerra, M. Association of dietary patterns with metabolic syndrome: Results from the kardiovize brno 2030 study. Nutrients 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suliga, E.; Kozieł, D.; Cieśla, E.; Głuszek, S. Association between dietary patterns and metabolic syndrome in individuals with normal weight: A cross-sectional study. Nutr. J. 2015, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arisawa, K.; Uemura, H.; Yamaguchi, M.; Nakamoto, M.; Hiyoshi, M.; Sawachika, F.; Katsuura-Kamano, S. Associations of dietary patterns with metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance: A cross-sectional study in a Japanese population. J. Med. Investig. 2014, 61, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, H.D.; Shin, A.; Kim, J. Dietary patterns of korean adults and the prevalence of metabolic syndrome: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akter, S.; Nanri, A.; Pham, N.M.; Kurotani, K.; Mizoue, T. Dietary patterns and metabolic syndrome in a Japanese working population. Nutr. Metab. 2013, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baik, I.; Lee, M.; Jun, N.R.; Lee, J.Y.; Shin, C. A healthy dietary pattern consisting of a variety of food choices is inversely associated with the development of metabolic syndrome. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2013, 7, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Hickson, D.A.; Musani, S.K.; Talegawkar, S.A.; Carithers, T.C.; Tucker, K.L.; Fox, C.S.; Taylor, H.A. Dietary patterns, abdominal visceral adipose tissue, and cardiometabolic risk factors in African Americans: The Jackson heart study. Obesity 2013, 21, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naja, F.; Nasreddine, L.; Itani, L.; Adra, N.; Sibai, A.M.; Hwalla, N. Association between dietary patterns and the risk of metabolic syndrome among Lebanese adults. Eur. J. Nutr. 2013, 52, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.Y.; Kim, M.K.; Lee, M.; Kim, Y.O. Macronutrient Composition and Sodium Intake of Diet Are Associated with Risk of Metabolic Syndrome and Hypertension in Korean Women. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Song, Y.; Lee, K.H.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, M.; Jee, S.H.; Joung, H. A fruit and dairy dietary pattern is associated with a reduced risk of metabolic syndrome. Metabolism 2012, 61, 883–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.; Dallongeville, J.; Haas, B.; Ruidavets, J.B.; Amouyel, P.; Ferrières, J.; Simon, C.; Arveilera, D. Sedentary behaviour, physical activity and dietary patterns are independently associated with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Metab. 2012, 38, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cattafesta, M.; Salaroli, L.B. Diets high in vegetables, fruits, cereals, and tubers as a protective factor for metabolic syndrome in bank employees. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2018, 11, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.A.; Kim, J.; Cho, E.R.; Shin, A. Dietary patterns and the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Korean women. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2011, 21, 893–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidemann, C.; Scheidt-Nave, C.; Richter, A.; Mensink, G.B.M. Dietary patterns are associated with cardiometabolic risk factors in a representative study population of German adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 106, 1253–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Jo, I. Grains, Vegetables, and Fish Dietary Pattern Is Inversely Associated with the Risk of Metabolic Syndrome in South Korean Adults. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2011, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amini, M.; Esmaillzadeh, A.; Shafaeizadeh, S.; Behrooz, J.; Zare, M. Relationship between major dietary patterns and metabolic syndrome among individuals with impaired glucose tolerance. Nutrition 2010, 26, 986–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denova-Gutiérrez, E.; Castañón, S.; Talavera, J.O.; Gallegos-Carrillo, K.; Flores, M.; Dosamantes-Carrasco, D.; Willett, W.C.; Salmerón, J. Dietary Patterns Are Associated with Metabolic Syndrome in an Urban Mexican Population. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 1855–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiBello, J.R.; McGarvey, S.T.; Kraft, P.; Goldberg, R.; Campos, H.; Quested, C.; Laumoli, T.S.; Baylin, A. Dietary Patterns Are Associated with Metabolic Syndrome in Adult Samoans. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 1933–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noel, S.E.; Newby, P.K.; Ordovas, J.M.; Tucker, K.L. A Traditional Rice and Beans Pattern Is Associated with Metabolic Syndrome in Puerto Rican Older Adults. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 1360–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutsey, P.L.; Steffen, L.M.; Stevens, J. Dietary intake and the development of the metabolic syndrome: The atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Circulation 2008, 117, 754–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaillzadeh, A.; Kimiagar, M.; Mehrabi, Y.; Azadbakht, L.; Hu, F.B.; Willett, W.C. Dietary patterns, insulin resistance, and prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 910–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagiotakos, D.B.; Pitsavos, C.; Skoumas, Y.; Stefanadis, C. The Association between Food Patterns and the Metabolic Syndrome Using Principal Components Analysis: The ATTICA Study. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2007, 107, 979–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drake, I.; Sonestedt, E.; Ericson, U.; Wallström, P.; Orho-Melander, M. A Western dietary pattern is prospectively associated with cardio-metabolic traits and incidence of the metabolic syndrome. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 119, 1168–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassannejad, R.; Kazemi, I.; Sadeghi, M.; Mohammadifard, N.; Roohafza, H.; Sarrafzadegan, N.; Talaeig, M.; Mansourian, M. Longitudinal association of metabolic syndrome and dietary patterns: A 13-year prospective population-based cohort study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2018, 28, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shokrzadeh, F.; Aslani, Z.; Rahimi-Foroushani, A.; Shab-Bidar, S. Interaction between a variant of vitamin D receptor gene and a posteriori dietary patterns on metabolic syndrome and its components: A nutrigenetic observational study. Nutr. Food Sci. 2018, 48, 780–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.Y.; Liu, J.J.; Zhan, X.M.; Feng, H.M.; Zhang, Y.Y. Dietary patterns and the risk of metabolic syndrome in Chinese adults: A population-based cross-sectional study. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 2409–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drehmer, M.; Odegaard, A.O.; Schmidt, M.I.; Duncan, B.B.; Cardoso, L.d.; Matos, S.M.A.; Molina, M.d.B.; Barreto, S.M.; Pereira, M.A. Brazilian dietary patterns and the dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet-relationship with metabolic syndrome and newly diagnosed diabetes in the ELSA—Brasil study. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2017, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falahi, E.; Anbari, K.; Ebrahimzadeh, F.; Roosta, S. Dietary patterns associated with metabolic syndrome: The Khorramabad Study. J. Nutr. Food Secur. 2017, 2, 201–212. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begg, C.B.; Mazumdar, M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994, 50, 1088–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egger, M.; Smith, G.D.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, S.F.; Cantwell, M.M.; Cardwell, C.R.; Velentzis, L.S.; Woodside, J.V. Dietary patterns and breast cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 1294–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magalhães, B.; Peleteiro, B.; Lunet, N. Dietary patterns and colorectal cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2012, 21, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Larsen, V.; Morton, V.; Norat, T.; Moreira, A.; Potts, J.F.; Reeves, T.; Bakolis, I. Dietary patterns derived from principal component analysis (PCA) and risk of colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 73, 366–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, P.-Y.; Shu, L.; Shen, S.-S.; Chen, X.-J.; Zhang, X.-Y. Dietary Patterns and Pancreatic Cancer Risk: A Meta—Analysis. Nutrients 2017, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Li, Z.; Han, J. A Healthy Dietary Pattern Reduces Lung Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta—Analysis. Nutrients 2016, 8, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabiani, R.; Minelli, L.; Bertarelli, G.; Bacci, S. A Western Dietary Pattern Increases Prostate Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta—Analysis. Nutrients 2016, 8, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabiani, R.; Naldini, G.; Chiavarini, M. Dietary Patterns in Relation to Low Bone Mineral Density and Fracture Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta—Analysis. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Monforte, M.; Flores-Mateo, G.; Sánchez, E. Dietary patterns and CVD: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 114, 1341–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEvoy, C.T.; Cardwell, C.R.; Woodside, J.V.; Young, I.S.; Hunter, S.J.; McKinley, M.C. A Posteriori Dietary Patterns Are Related to Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: Findings from a Systematic Review and Meta—Analysis. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 114, 1759–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jannasch, F.; Kröger, J.; Schulze, M.B. Dietary Patterns and Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta—Analysis of Prospective Studies. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 1174–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Rest, O.; Berendsen, A.A.; Haveman-Nies, A.; de Groot, L.C. Dietary Patterns, Cognitive Decline, and Dementia: A Systematic Review. Adv. Nutr. 2015, 6, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devine, C.M. A life course perspective: Understanding food choices in time, social location, and history. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2005, 37, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousar, R.; Burns, C.; Lewandowski, P. A culturally appropriate diet and lifestyle intervention can successfully treat the components of metabolic syndrome in female Pakistani immigrants residing in Melbourne, Australia. Metabolism 2008, 57, 1502–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghsoudi, Z.; Azadbakht, L. How dietary patterns could have a role in prevention, progression, or management of diabetes mellitus? Review on the current evidence. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2012, 17, 694–709. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Calton, E.K.; James, A.P.; Pannu, P.K.; Soares, M.J. Certain dietary patterns are beneficial for the metabolic syndrome: Reviewing the evidence. Nutr. Res. 2014, 34, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadbakht, L.; Mirmiran, P.; Esmaillzadeh, A.; Azizi, T.; Azizi, F. Beneficial Effects of a Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Eating Plan on Features of the Metabolic Syndrome. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 2823–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamsson, V.; Reumark, A.; Cederholm, T.; Vessby, B.; Risérus, U.; Johansson, G. What is a healthy Nordic diet? Foods and nutrients in the NORDIET study. Food Nutr. Res. 2012, 56, 18189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucci, G.; Alcidi, R.; Tap, L.; Battista, F.; Mattace-Raso, F.; Schillaci, G. Sex-and gender-related prevalence, cardiovascular risk and therapeutic approach in metabolic syndrome: A review of the literature. Pharmacol. Res. 2017, 120, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadbakht, L.; Esmaillzadeh, A. Red Meat Intake Is Associated with Metabolic Syndrome and the Plasma C—Reactive Protein Concentration in Women. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nettleton, J.A.; Steffen, L.M.; Mayer-Davis, E.J.; Jenny, N.S.; Jiang, R.; Herrington, D.M.; Jacobs, D.R., Jr. Dietary patterns are associated with biochemical markers of inflammation and endothelial activation in the Multi—Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 83, 1369–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, F.E.; Shivappa, N.; Tang, Y.; Mann, J.R.; Hebert, J.R. Association between diet-related inflammation, all-cause, all-cancer, and cardiovascular disease mortality, with special focus on prediabetics: Findings from NHANES III. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 56, 1085–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, T.T.; Willett, W.C.; Stampfer, M.J.; Manson, J.E.; Hu, F.B. Dietary patterns and the risk of coronary heart disease in women. Arch. Intern. Med. 2001, 161, 1857–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).