Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Developed and implemented a masked loss function that enables accurate reconstruction of 3-dimensional sea temperature fields across both coastal and offshore regions.

- By leveraging daily satellite-derived SST and SSH observations, the model reconstructs long-term temperature fields and supports near-real-time nowcasting.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- The reconstructed multidecadal dataset supports analyses of long-term ocean warming, marine heatwaves, and circulation changes in marginal seas.

- Provides a computationally efficient alternative to conventional ocean reanalysis, enabling near-real-time generation of 3-dimensional sea temperature fields from daily satellite inputs and offering a practical tool for operational monitoring.

Abstract

Understanding ocean temperature structure and its spatiotemporal variability is essential for studying ocean circulation, climate, and marine ecosystems. While previous approaches using observations and numerical models have advanced our understanding, they face limitations such as sparse data coverage and computational bias. To address these issues, we developed an ensemble of data-driven neural network models trained with in situ vertical profiles and daily remote sensing inputs. Unlike previous studies that were limited to open-ocean regions, our model explicitly included coastal areas with complex bathymetry. The model was applied to the East/Japan Sea and reconstructed 31 years (1993–2023) of daily three-dimensional ocean temperature fields at 13 standard depths. The predictions were validated against observations, showing RMSE < 1.33 °C and bias < 0.10 °C. Comparisons with previous studies confirmed the model’s ability to capture short- to mid-term temperature variations. This data-driven approach demonstrates a robust alternative to traditional methods and offers an applicable and reliable tool for understanding long-term ocean variability in marginal seas.

1. Introduction

The East/Japan Sea (EJS), with an average depth of 2 km and enclosed by Korea, Japan, and Russia, is a marginal sea characterized as a semi-enclosed basin. Referred to as a “miniature ocean,” the EJS exhibits major features of global oceanic dynamics, spanning from the subpolar to subtropical seas [1,2]. Therefore, the EJS has been suggested as a testbed to facilitate the unraveling of future changes expected across the entire ocean [3,4]. For instance, the long-term warming rate in the EJS is exceptionally strong—up to eight times greater than the global mean (+0.041 °C yr-1 versus approximately +0.005 °C yr-1)—placing the EJS among the top tier of sea-surface temperature increase globally [5,6]. Additionally, as ocean temperatures rise, marine heatwaves [7] have become one of the most widely discussed consequences of ocean warming, with their frequency and severity increasing in the EJS [8,9,10].

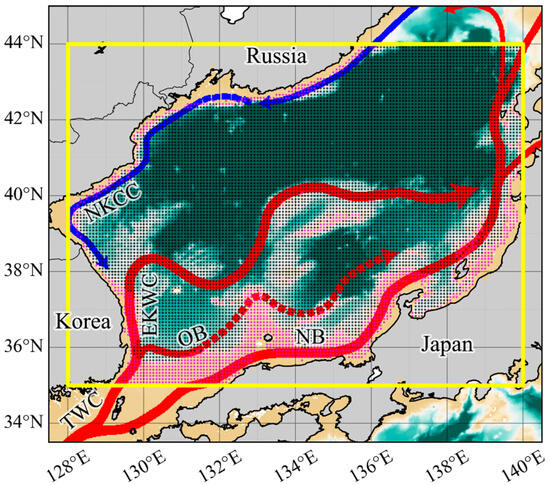

The EJS contains a variety of currents and physical phenomena, displaying characteristics that range from subpolar to subtropical seas. The EJS is influenced by the mixing of a part of the Kuroshio Current from the south and seawater from the East China Sea, which flows northward. This flow is known as the Tsushima Warm Current (TWC), which further divides into the East Korea Warm Current (EKWC), which flows northward along the eastern coast of Korea; the Nearshore Branch (NB) of the TWC, which moves northeastward along the western coast of Japan; and the Offshore Branch (OB) of the TWC, which travels eastward off the southeastern coast of Korea (Figure 1). Conversely, from the north, the North Korea Cold Current (NKCC) flows southward along the eastern coast of North Korea. The NKCC and EKWC meet at approximately 38°N, turn eastward to create the subpolar front (SF), and then meander with a significant amplitude depending on the balance of their forces [11,12,13,14]. A key physical feature that influences the temperature variation in this region is the SF, which has been migrating northward in recent decades [15], the Ulleung Warm Eddy (UWE) located south of the SF, and the Dok Cold Eddy (DCE) separated from the SF meander to the south. In addition, during summer, southerly monsoon winds blow parallel to the southeastern coast of Korea, leading to coastal upwelling that compensates for the movement of deeper waters to the surface. Consequently, this process induces cooling of the coastal surface [16,17,18]. These various physical processes always occur in the EJS.

Figure 1.

Study area and mean currents map of East/Japan Sea (KHOA, Badanuri Marine Information Service). The yellow box represents the study area and 10,812 dots (magenta: shallower than 500 m; gray: deeper than 500 m) indicate the locations for temperature estimation. The blue arrow indicates cold currents, named the North Korea Cold Current (NKCC). The red arrows show the warm currents, which comprise the offshore branch (OB) and nearshore branch (NB) of the Tsushima Warm Current (TWC) and East Korea Warm Current (EKWC).

In situ observations have traditionally played a crucial role in understanding the diverse circulation processes in this region [2,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. However, such methods require substantial human and material resources and are limited in their ability to provide regular, high-resolution spatiotemporal data. Previous studies, aided by advances in satellite observation, have made it possible to analyze ocean temperature data across various spatial and temporal scales in the EJS [26,27]. However, significant limitations remain in detecting subsurface water property changes. To address these issues, data-assimilated numerical models have been utilized. However, most of the data used for assimilation are limited to the surface, which results in subsurface errors and biases. This limitation has been reported in a previous study [28], which revealed that data-assimilated numerical models weakly simulated horizontal temperature gradient—producing cooler warm eddies, warmer cold eddies, and consequently weaker mesoscale thermal contrasts compared with observed temperature fields in the EJS.

In recent years, artificial neural network (ANN) models have emerged as promising solutions to these issues. This progress is driven by the generation of large amounts of satellite remote sensing data and the ability of ANNs to model the relationship between ocean surface and subsurface parameters [29]. Previous studies that have attempted to predict or reconstruct three-dimensional (3-D) ocean temperatures have mostly relied on estimating the correlations between remote sensing data and hydrographic profiles (e.g., temperature-salinity profiles) [30,31,32,33,34,35]. However, most of these studies have difficulties in reproducing oceanic phenomena below the mesoscale, including eddies. This is primarily ascribable to the use of monthly gridded Argo profiling float data. Although certain studies have utilized in situ data, most have excluded shallow-depth regions as their focus is primarily on the open ocean [30,31,32,33,34,35].

The coastal region considered in the study area differs significantly from the open ocean. The dynamic spatiotemporal variability of coastal ocean temperature reflects various circulation mechanisms compared with the open ocean. Owing to the presence of land boundaries, coastal upwelling occurs [36], and the NKCC moves south along the continental shelf, exhibiting the characteristic behavior of a Taylor column [37]. Moreover, nearshore areas exhibit horizontal gradients of temperature that are parallel to the coastline [38]. Most importantly, the presence of various depths distinguishes modeling in coastal regions from that in the open ocean. In this study, diverse strategies are employed, ranging from data preparation to the masked loss technique, to model the depth-changing bathymetry of coastal regions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

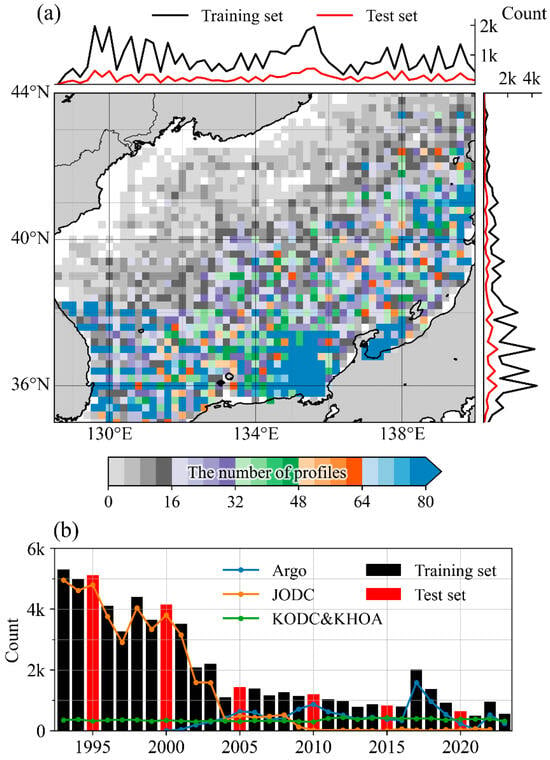

The study area encompasses the EJS, bounded by 35–44°N and 128–140°E. In situ temperature profile data were used as supervised learning targets and were obtained from the following sources (Table 1): the Korea Oceanographic Data Center (KODC; https://www.nifs.go.kr/kodc/soo_list.kodc; accessed on 3 January 2026), Korea Hydrographic and Oceanographic Agency (KHOA), Japan Oceanographic Data Center (JODC; https://www.jodc.go.jp/vpage/scalar.html; accessed on 3 January 2026), the Argo program (https://data-argo.ifremer.fr/geo/pacific_ocean; accessed on 3 January 2026), and the Circulation Research of East Asian Marginal Seas (CREAMS) studies. The 64,554 data points collected from these five institutions (or programs) during 1993–2023 exhibited spatially and temporally non-uniform distributions (Figure 2a,b). Moreover, because of the steep seabed gradient characteristics of the EJS, the depth-axis length of the data covered a wide range. In this study, the reconstruction objective was set from the surface to 500 m, where the thermocline ends and temperature variability diminishes in the EJS. Thirteen levels (10, 20, 30, 50, 75, 100, 125, 150, 200, 250, 300, 400, and 500 m) were set as the standard depths for profile prediction.

Table 1.

Summary of target and input data.

Figure 2.

(a) Spatial distribution of all available temperature profiles. The background colormap represents the total number of profiles in each 0.2° × 0.2° grid cell. The top and right-side plots show the number of profiles aggregated in the meridional and zonal directions, respectively, with separate lines for training (black) and test (red) sets. (b) Temporal distribution of profiles used in model training and testing. The black and red bars indicate the number of profiles used in the training and test sets, respectively. Colored lines represent the annual number of profiles provided by each contributing program (see main text for source details).

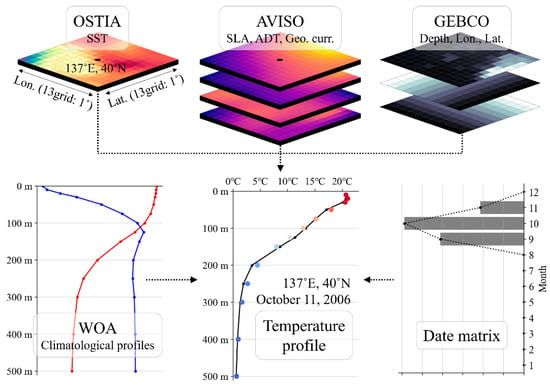

Remote sensing, bathymetry, and temperature statistics data were used to estimate target ocean temperature profiles. Sea surface temperature (SST) data were selected from the 1/20° high-resolution Operational Sea Surface Temperature and Ice Analysis (OSTIA) produced by the Group for High Resolution Sea Surface Temperature (GHRSST) project, employing satellite and in situ observation data. For the development of the ANN model, reprocessed data (https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00168; SST_GLO_SST_L4_REP_OBSERVATIONS_010_011; accessed on 3 January 2026) and analysis (near-real-time) data (https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00165; SST_GLO_SST_L4_NRT_OBSERVATIONS_010_001; accessed on 3 January 2026) were used as input.

Sea surface heights and derived data were obtained from the AVISO product with a spatial resolution of 1/4°, published by the Copernicus Marine Service. Reprocessed data (https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00145; SEALEVEL_GLO_PHY_CLIMATE_L4_MY_008_057; accessed on 3 January 2026) and near-real-time data (https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00149; SEALEVEL_GLO_PHY_L4_NRT_008_046; accessed on 3 January 2026) were employed for model building. The training features selected from the AVISO data included absolute dynamic topography (ADT), sea level anomaly (SLA), and geostrophic velocity anomalies (UGOSA and VGOSA for zonal and meridian components, respectively).

Climatological temperature data were collected from the World Ocean Atlas 2018 (WOA18; https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/world-ocean-atlas-2018/; accessed on 3 January 2026), with variables comprising 3-D fields of ocean temperature monthly mean and their anomalies (T_MA and T_AN). In addition, bathymetry (DEP) data provided by the General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans (GEBCO; https://www.gebco.net/) at a spatial resolution of 1/240° were utilized. To enhance the model’s ability to capture seasonal variation, we introduced a 1 × 12 date matrix as an input feature. Unlike typical sinusoidal encodings (e.g., sin and cos of day-of-year), this smoothed one–hot–like structure distributes seasonal cues across multiple dimensions, providing more explicit signals and improving interaction with other variables during learning.

All collected input variables were normalized using statistical values to adhere to the mean (μ) = 0 and standard deviation (σ) = 1 within the dataset, and gridded to a common spatial resolution of 1/12° to provide a unified spatial scale across datasets for CNN-based feature extraction. Because approximately 40% of the target grid points are located within a 1° by 1° convolutional window that intersects the coastline, explicit treatment of land–sea boundaries is unavoidable.

GEBCO bathymetry includes positive land elevations that can exceed +2600 m near the coast. If these values are directly used, the resulting sign and scale differences relative to ocean depths (which reach approximately −4000 m) would strongly influence convolutional filters and introduce nonphysical artifacts unrelated to subsurface temperature. To prevent this, all land elevations within the convolutional input window were uniformly replaced with a constant depth value of 20 m. This value does not represent a physical bathymetric boundary; rather, it provides a stable and neutral boundary-padding condition that avoids both confusion with shallow coastal waters and domination by extreme land elevations, allowing the CNN to clearly identify domain edges without introducing nonphysical gradients. Similarly, satellite-derived oceanic variables (e.g., OSTIA and AVISO) are undefined over land. Since convolution operations require complete local neighborhoods, these variables were extrapolated into adjacent land grid cells solely to maintain numerically well-posed convolutional inputs.

The reconstructability (predictability) of a model should ensure objectivity in its error levels. To evaluate the utility of the model results, both quantitatively and qualitatively, an additional comparative verification using two general numerical models was conducted. The comparison data comprised 3-D temperature simulations from the Hybrid Coordinate Ocean Model (HYCOM; https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2009.39; accessed on 3 January 2026) and Global Ocean Physics Reanalysis (GLORYS12V1; GLobal Ocean Reanalysis and Simulation, hereafter referred to as GLORYS; https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00021; accessed on 3 January 2026), which applied data assimilation. To align the data, the temperature values were linearly interpolated for the target locations and depths.

2.2. Construction of ANN Model

This section introduces the process of building an ANN for optimized 3-D temperature field prediction, along with related model design considerations. As mentioned above, the study area exhibits complex and diverse temperature variability across both time and space, necessitating a wide range of input data for model training. Processed data from OSTIA and AVISO have dimensions of [time, latitude, longitude, feature], while GEBCO data have dimensions of [latitude, longitude, feature]. Data from WOA18 and the date matrix are treated as scalar inputs, with temporal and depth axes disregarded, resulting in a [feature]-shaped tensor.

Figure 3 illustrates an overview of the model architecture, and a detailed schematic of the full structure is provided in Supplementary Figure S1. To optimize model configuration, we conducted 20 comparative experiments varying the temporal and spatial input settings—an approach referenced by [39], who evaluated model performance under different temporal input lengths. We tested temporal input sequences of 1-, 3-, 5-, 7-, and 9-day and spatial inputs consisting of 1, 7, 13, and 19 neighboring grids were considered, corresponding approximately to spatial ranges of 1 grid (1/12°), 0.5°, 1.0°, and 1.5°, respectively. Each target location was placed at the center of its respective square grid during these experiments. The results of these experiments are presented in Supplementary Figure S2. Based on these results, the input configuration using a 1-day length and 13-grid spatial context was selected, as it offered the best trade-off between low test-set error and minimal overfitting. Supplementary Figure S2a,b show the training and test losses (RMSE), respectively, and Figure S2c visualizes the generalization loss rate, defined as the normalized difference between test and training loss.

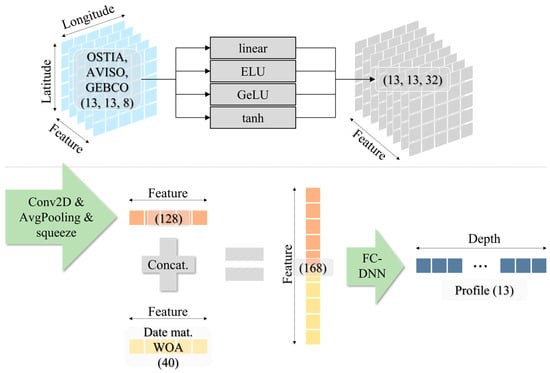

Figure 3.

Model structure for estimating temperature profile. Numbers in brackets indicate tensor dimensions. Spatial data inputs (OSTIA, AVISO, and GEBCO) undergo multiple activation functions and convolutional processing. This compressed spatial feature vector is then concatenated with auxiliary scalar inputs (e.g., WOA climatology and date matrix) and passed to a fully connected deep neural network (FC-DNN) to estimate 13-level temperature profiles. A detailed layer-by-layer architecture is provided separately in Supplementary Figure S1.

Following the approach of [40], who demonstrated improved generalization by exploring multiple activation functions, we implemented parallel dense layers with linear, ELU, GeLU, and tanh activations on the spatial inputs. Compared to models using a single activation function, this design reduced both training and test RMSE (Supplementary Table S1), indicating enhanced representational capacity and mitigation of under-fitting. Although this configuration increases the number of trainable parameters by approximately 10%, the improvement in predictive performance suggests that the added complexity is justified.

The activation outputs are then processed by multiple 2-D convolution and average pooling layers, effectively compressing the spatial dimensions. The resulting feature-only tensors are concatenated with auxiliary inputs (e.g., WOA18 and the date matrix), which provide climatological and seasonal information to the model. Specifically, WOA18 inputs include 28 features representing the local mean and anomalies near the target location across the surface (0 m) and 13 subsurface layers, matching the depth levels of the target profile. The date matrix consists of 12 features based on a smoothed one–hot–like structure to encode seasonality. Finally, the fully connected dense layers estimate a vertical temperature profile at 13 standard depth levels.

The design overview of the model, including hyperparameters, is summarized in Table 2. To assess both the nowcasting capability and the reliability of long-term reconstruction, six years (1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, 2020) were selected as test years by subsampling across the full study period. This design provides temporally independent evaluation while maintaining a commonly used training–testing ratio (~80:20). After excluding the test years, the remaining profiles were randomly partitioned at the sample level (80% training, 20% validation), independent of spatial location or season. No rebalancing or oversampling was applied to any subset of the data.

Table 2.

Summary of model setting and hyperparameter.

The model constructed with this dataset was independently trained seven times and then averaged using ensemble mean techniques, specifically bagging (bootstrap aggregating). Model ensemble techniques are widely used in various machine learning studies to mitigate issues, such as bias-induced underfitting or high variance-induced overfitting (e.g., [41,42]). Furthermore, because each ensemble member is trained on a different bootstrap-sampled configuration, the ensemble mean becomes less sensitive to localized sampling density and yields a more stable representation of the underlying temperature structure.

The target data encompass various depths across the target domain, so tensors below the observed depth at each target point should be excluded from contributing to loss updates. In general, incorporating prior knowledge into loss design has also been explored in previous work [43]. Following this idea, we adopted a masking technique that utilizes the prior knowledge of observed depth at each target location. The resulting loss function, referred to as the masked mean squared error, is further extended to incorporate not only the profile values but also their vertical gradients. The complete formulation is given as follows:

In this equation, and denote the observed and predicted temperatures at depth level in the -th profile, respectively. The terms and represent the first-order vertical differences (i.e., vertical gradients) of the true and predicted profiles. The binary mask indicates whether a valid observation exists at the corresponding depth and is used to exclude missing values (e.g., 999). For the gradient term, the mask is defined as , ensuring that vertical differences are computed only when both adjacent depth levels contain valid observations. Here, denotes the number of valid depth levels in the -th profile. Each mean squared error term is normalized by the corresponding number of valid samples— for the profile values and for the vertical gradients. The total loss is computed by averaging the sum of the two normalized MSE across all profiles. Based on sensitivity tests with the value was adopted, as it provided the most stable representation of mid-depth structures: increased mid-depth instability, while caused warm-bias amplification in the thermocline.

Figure 4 illustrates an example of temperature profile training (or estimation) at a specific location (137°E, 40°N) and date (11 October 2006). To estimate this single profile, the model receives four categories of input: (1) remote sensing-based surface data (e.g., SST, SLA, ADT), (2) geophysical fields including latitude, longitude, and bathymetry, (3) climatological temperature statistics, and (4) date encodings. All spatial inputs—including the geophysical and remote-sensing fields—are extracted from a 1° × 1° latitude–longitude grid box centered at the target location. These diverse inputs collectively help constrain the vertical structure and ensure the spatial–temporal coherence of the predicted profile.

Figure 4.

Schematic of temperature profile estimation at 137°E, 40°N on 11 October 2006. The black line indicates the observed temperature profile, while the colored dots represent the model-estimated values. To predict this target profile, the model utilizes surrounding spatial data within a 1° × 1° latitude–longitude grid box, along with climatological inputs and the date information. Detailed data sources and input features are described in the main text and Table 1 and Table 2.

This model, once trained and validated as described above, is not limited to retrospective reconstruction but can also be applied for near-real-time nowcasting of 3-D temperature fields. By processing daily satellite-derived SST (from OSTIA) and SSH-based products (from AVISO) through the trained network weights, the system is capable of generating updated 3-D subsurface temperature estimates for the entire EJS on a daily basis. These satellite inputs are available in near-real-time and are interpolated to the 1/12° model grid in a manner consistent with the preprocessing used during training, ensuring that operational predictions remain fully aligned with the training conditions. Such capability demonstrates the model’s practical applicability for operational ocean monitoring, enabling continuous temperature field updates with minimal latency. In this nowcasting mode, only the satellite-driven variables (SST, SLA, ADT, and geostrophic currents) are updated daily, whereas static inputs such as GEBCO bathymetry and climatological fields (e.g., WOA18) remain unchanged and are retrieved according to the target date and location. The complete model configuration and pretrained weight files are openly available via the project’s Git repository (https://github.com/EJLee58/EJS-temp-ANN; accessed on 3 January 2026).

2.3. Feature Importance (FI) Test

ANN models are designed to focus on finding correlations between input and target data. However, the most common issue arising from this characteristic is overfitting. Overfitting can be described as the state where the model memorizes noise in addition to learning patterns from the data. When a model is overfitted, it performs well on the training data but fails to generalize new data. To address overfitting in machine learning, various methods and modules have been proposed, and their common mechanism is to reduce the capacity (complexity) of the model (e.g., weight decay [44] and dropout [45]). The complexity of the model increases with the number of hidden layers and nodes, as well as the number of features in the input data. Therefore, to control overfitting in our model, we performed feature importance tests for each training feature (variable) using the following equation during the optimization process.

Here, ) denotes the feature importance of the variable , defined as the increase in RMSE when only the values of are replaced with their mean, while all other variables remain unchanged. Depending on the analysis, the corresponds to a single input feature or a subset of multiple variables. denotes the RMSE operator, and and represent the true values and the values computed by the model, respectively. Since all input variables were standardized prior to training, signifies the variability removed input, i.e., almost zero, and denotes the result passed through the trained model. Thus, is the RMSE of the optimized model using the original input , while is the RMSE derived from results distorted by the averaged input data. Since FI is computed as the RMSE difference between the original and consistency models, it naturally inherits the unit of RMSE (°C). A large ) (thus, an increase in ) implies that the variability of the corresponding variable significantly influences the trained model (has the large weights). Moreover, in some cases, the of the test set is significantly smaller than the training set’s or even negative. This means that the model has overfitted to the training set by resembling memorization, which suggests that removing such variables would improve the fit.

In the optimization process, we used FI as a criterion and removed 19 out of the initial 30 variables due to their low importance or their role causing overfitting. Since the completed model training through this process minimizes overfitting. Additionally, the FI test conducted after the optimization process was utilized to analyze the input variables that have a crucial role in modeling the vertical temperature profile in the EJS. A detailed description and visualization of the retained 11 variables are provided in Section 3.2.1.

3. Results

3.1. Validation for Reconstruction and Prediction

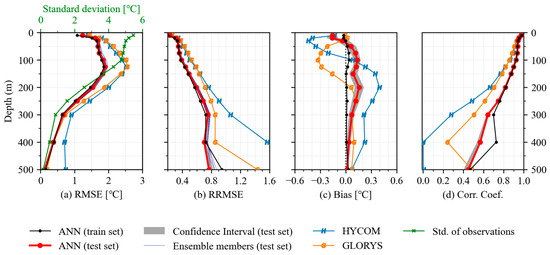

Our long-term 3-D temperature reconstruction ANN model achieved better performance compared to data-assimilated numerical models such as HYCOM (1.73 °C) and GLORYS (1.65 °C), with a depth-averaged RMSE of 1.33 °C for the test set (Table 3). The ANN also showed the lowest errors across all 13 individual depth levels (Figure 5). Among these, the highest errors were observed around 125 m. In order to minimize overfitting, the model configuration was fixed through the optimization procedure described in Section 2. As a result, the RMSE for the training set was 1.29 °C, indicating a small difference between training and test performance across training years and independent test years.

Table 3.

Depth-averaged validation metrics for three models. Bias values represent the average of absolute bias over all depth levels.

Figure 5.

Depth-wise validation of four metrics—(a) root mean squared error (RMSE), (b) relative RMSE (RRMSE), (c) mean error (bias), and (d) correlation coefficient—for three models in the EJS. The black line represents the ensemble mean of the proposed ANN model, averaged across 7 members. Thin navy lines show the results of individual ensemble members, while the shaded gray band indicates the 99% confidence interval derived from 1000 bootstrap samples. Blue and orange lines indicate HYCOM and GLORYS, respectively. The green line means the standard deviation of observations. In the bias panel, the dashed vertical line denotes zero bias.

Moreover, the ensemble mean showed superior performance compared to any single ANN member. As shown in Figure 5, the ensemble mean consistently yielded lower RMSE and RRMSE values than individual members. To further assess the robustness of the ensemble prediction, a 99% confidence interval was derived using 1000 bootstrap samples. The depth-averaged RMSE of the ensemble mean (1.33 °C) not only lies below the full range of the individual ensemble members (1.36–1.39 °C) but also falls within the narrow 99% confidence interval (1.33–1.35 °C). This demonstrated enhanced predictive stability across varying depths and temporal conditions.

Relative RMSE (RRMSE) was computed by normalizing the RMSE at each depth with the corresponding standard deviation of in situ temperatures, thereby allowing depth-wise comparison of model errors relative to the natural variability of the ocean. Similar to RMSE, the proposed ANN consistently exhibited the lowest RRMSE among the three models. RMSE peaked near the thermocline, whereas RRMSE remained moderate. The thermocline band is generally characterized by strong natural temperature variability. Below the mixed layer, temperature variability sharply decreases, and all three models struggled to simulate such weak gradients. Notably, HYCOM exhibited high RRMSE at depths greater than 300 m, occasionally exceeding the standard deviation of the observed temperature, suggesting difficulties in representing the deep-water thermal structure.

In the bias profile, the two reanalysis models, HYCOM and GLORYS, showed notable depth-dependent deviations. HYCOM exhibited a cold bias in surface layers and a warm bias at depth, while GLORYS showed a strong cold bias in the mid-depth range (~75–200 m). In contrast, the proposed ANN model maintained consistently low bias across all depths, with only minor deviations near the thermocline. In terms of the correlation coefficient, the ANN showed the highest correlation with observations across all depths, particularly in the upper and thermocline layers. By contrast, HYCOM displayed relatively weaker agreement, with correlation coefficients dropping below 0.5 at depths of 250 m and below.

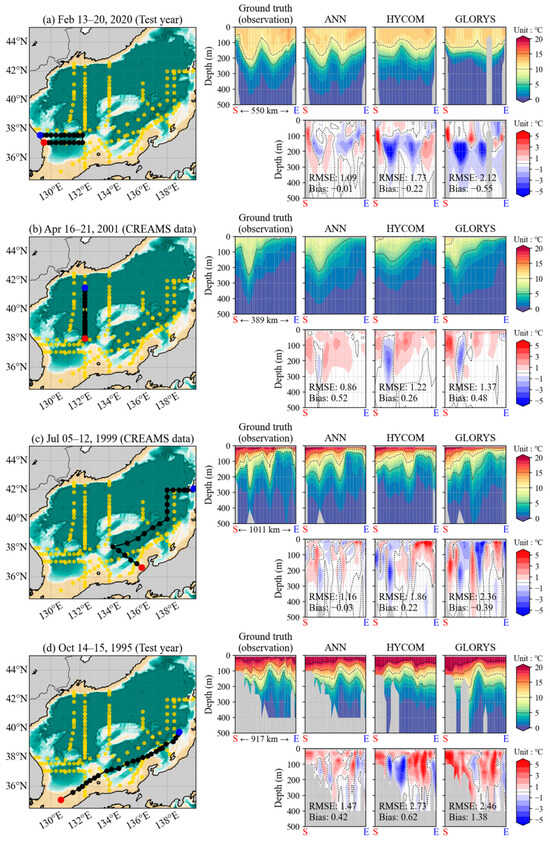

Further validation of our ANN model’s performance was conducted using seasonal vertical temperature sections (Figure 6a–d). The black dots on the left panels of each subfigure indicate the observation locations along the selected section, with red and blue dots marking the section’s starting and ending points, respectively. Yellow dots represent the inclusion of other transects not discussed in the main text, and detailed results for the remaining seven sections were provided in Supplementary Figure S3a–g. These sections were derived from specific years excluded from training or from independent in situ CREAMS data, ensuring that the test data were entirely separate from those used during model training.

Figure 6.

Comparison of season vertical temperature sections between observation, ANN, HYCOM, and GLORYS. For each panel (a–d), the left subpanel shows the geographical location of the transect (black dots), with red and blue markers indicating the start and end points, respectively. Yellow dots indicate additional observation transects, including seven Supplementary Sections illustrated in Figure S3a–g. Top subpanels show observed temperatures and corresponding model outputs. Bottom subpanels show temperature differences between the models and observations, and dashed contours indicate the zero-difference line. The four transects were chosen from years excluded from ANN training or from independent CREAMS data: (a) 13–20 February 2020 (test year), (b) 16–21 April 2001 (CREAMS), (c) 5–12 July 1999 (CREAMS), and (d) 14–15 October 1995 (test year).

For each season, representative sections were selected to evaluate the model’s ability to capture distinct hydrographic features across seasonal variability in the EJS. In winter (Figure 6a), the ANN effectively simulated the vertical and horizontal structure of the UWE near 131°E, 37°N, whereas HYCOM and GLORYS did not adequately capture its warm-core intensity and depth structure. In spring (Figure 6b), the ANN captured the transition from the well-mixed winter profile to a stratified structure. In summer (Figure 6c), when thermal stratification is strongest, the ANN showed superior spatial consistency along the extended 1011 km transect and better reproduced deep heat penetration below 200 m, which the numerical models did not adequately represent. In autumn (Figure 6d), the ANN more accurately reproduced the thermocline structure and horizontal gradients, enabling realistic simulation of the meandering TWC and the associated warm–cold–warm pattern between 131°E and 137°E.

3.2. Error Analysis

3.2.1. Feature Importance and Key Drivers

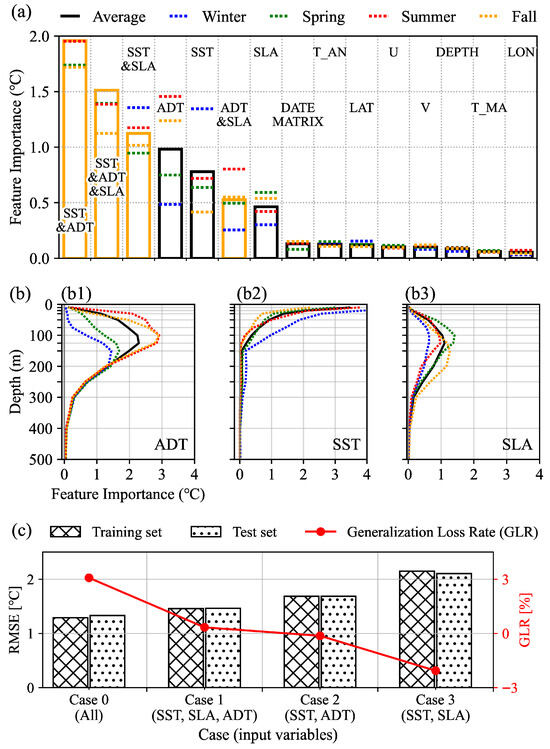

To identify the key factors governing 3-D temperature reconstruction, feature importance (FI) tests were conducted. A high FI indicates that variability in the corresponding input variable strongly influences the trained model output. Figure 7a presents the depth-averaged FI values for all input variables, averaged over the entire analysis period as well as by season. Among all input variables, ADT, SST, and SLA exhibit the highest depth-averaged FI values (Figure 7a), with magnitudes of 0.98 °C, 0.78 °C, and 0.46 °C, respectively. In contrast, the remaining variables show substantially lower FI values, ranging from 0.05 to 0.13 °C. The orange bars in Figure 7a represent results from multi-variable FI tests using combinations of SST, SLA, and ADT, indicating that these dominant predictors jointly contribute to subsurface temperature estimation.

Figure 7.

Feature contribution and model sensitivity analysis. All subplots share the same legend and abbreviations: absolute dynamic topography (ADT), sea surface temperature (SST), sea level anomaly (SLA), date matrix, monthly climatological temperature mean and their anomalies (T_MA and T_AN), geostrophic velocity anomalies (U, V), longitude (LON), latitude (LAT), and bathymetry (DEPTH). (a) Depth-averaged FI for all input features, along with seasonal averages (dotted lines: winter—blue, spring—green, summer—red, fall—brown). Orange bars indicate the results of multivariable tests. (b) FI profiles for the three most influential variables ((b1): ADT, (b2): SST, (b3): SLA), showing both overall and seasonal variability. Figure 7b shares the same legend and abbreviations as Figure 7a. (c) Model performance comparison using different combinations of the top three variables: full model (Case 0), top-three-only model (Case 1), and ablations without SLA (Case 2) and ADT (Case 3). Generalization loss rate (GLR) is calculated as the ratio of the RMSE difference between the test and training sets to the training RMSE; values greater than zero indicate overfitting, while values less than zero indicate underfitting.

Seasonal and depth-dependent variations are evident in the FI profiles of the three dominant predictors (Figure 7b). Distinct differences appear across depth and season, reflecting changes in the relative contribution of surface-related variables under varying stratification conditions. These profiles provide a depth-resolved view of how the dominant predictors influence the reconstructed temperature fields throughout the water column.

To further assess the role of the dominant predictors, a simplified model using only ADT, SST, and SLA as inputs was trained (Case 1 in Figure 7c). The performance of this reduced-input configuration remains comparable to that of the fully optimized model (Case 0), confirming that these variables account for the majority of the reconstruction skill. In contrast, ablation experiments excluding either SLA (Case 2) or ADT (Case 3) exhibit degraded test performance and generalization loss rates below zero, indicating underfitting relative to the full configuration.

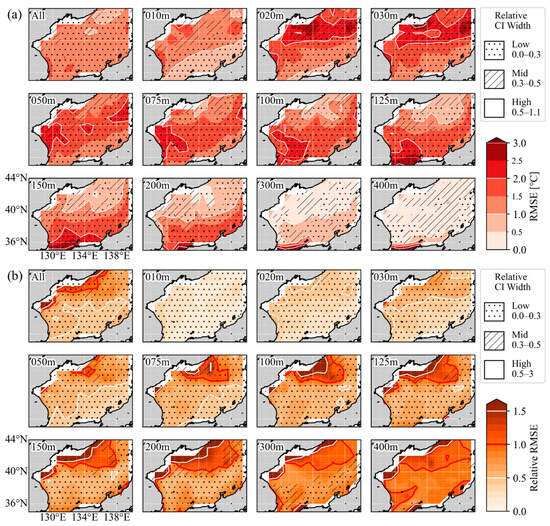

3.2.2. Influence of Target Data Distribution

Post-model completion error (or weights) analysis can provide insights into the limitations of the ANN model. Model error was evaluated using all available data, encompassing both training and test sets. Figure 8a,b present the RMSE and relative RMSE (RRMSE) of the ANN model, respectively, while the corresponding standard deviation (STD) and the number of observations used in the calculations are shown in Supplementary Figures S4a,b. To visualize statistical variability in the spatially scattered data, the results were aggregated into 10 (latitude) by 12 (longitude) groups at 1° intervals. For each metric, the 95% confidence interval (CI) was computed: RMSE and RRMSE used the t-distribution, while STD employed the chi-square distribution, considering their respective statistical properties. To facilitate spatial comparison, the CI band width in all panels was normalized by the local value at each grid point (i.e., RMSE, RRMSE, or STD). The resulting relative CI width is classified into three categories—low (0.0–0.3), mid (0.3–0.5), and high (>0.5)—and is shown with overlaid hatching. The top-left panels summarize vertically averaged values across depths, while the rest of the subpanels present horizontal slices at standard depth levels from 10 m to 400 m.

Figure 8.

Depth-specific temperature estimation errors of the ANN model. (a) Root mean squared error (RMSE) and (b) relative RMSE (RRMSE). The 95% confidence interval (CI) width, calculated using the t-distribution, is visualized with hatching patterns. All statistics were computed within 1° × 1° grid-cells groups. RRMSE was scaled by the standard deviation of observed temperatures in each grid. For reference, the corresponding standard deviation and the number of temperature profiles used in the analysis are shown in Supplementary Figure S4a,b. A more detailed explanation is provided in the main text.

According to the analysis, the model’s local performance was found to be largely governed by two factors: (1) the intrinsic variability of the observed temperature and (2) the spatial distribution (or density) of the target data, which give rise to distinct spatial and depth-dependent error patterns in the evaluation metrics. The model’s ability to reconstruct temperature values that deviate significantly from the central tendency of the data distribution tends to decrease. For example, areas such as sea water subduction (around 134°E, 42°N at 20–30 m; [46]), the location of eastward separation of the EKWC (around 130°E, 35°N at 125–150 m; [12]), and internal wave propagation (around 132°E, 35°N at 125–150 m; [47,48,49]) exhibit strong variability across a wide range of temporal scales, from daily to interannual.

Most of the readily available observations are concentrated in the southern EJS region (Figure 2 and Figure S4b). This spatial imbalance in data availability may lead to reduced model performance in the northern EJS. While this issue is not clearly visible in the RMSE map, it becomes apparent in the RRMSE map. At depths greater than 50 m, certain regions exhibit RRMSE values greater than 1 (outlined by red contour lines), indicating that the variability in error exceeds that of the temperature field itself. Additionally, the wide CIs of both RRMSE and standard deviation further suggest that model generalization is more challenging in the northern region, particularly at deeper layers.

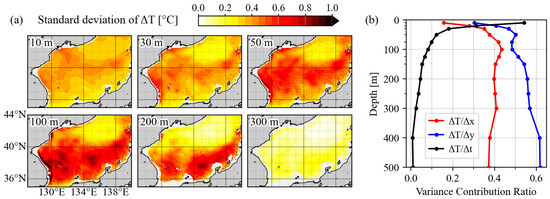

3.3. Spatiotemporal Continuity of the Reconstructed Field

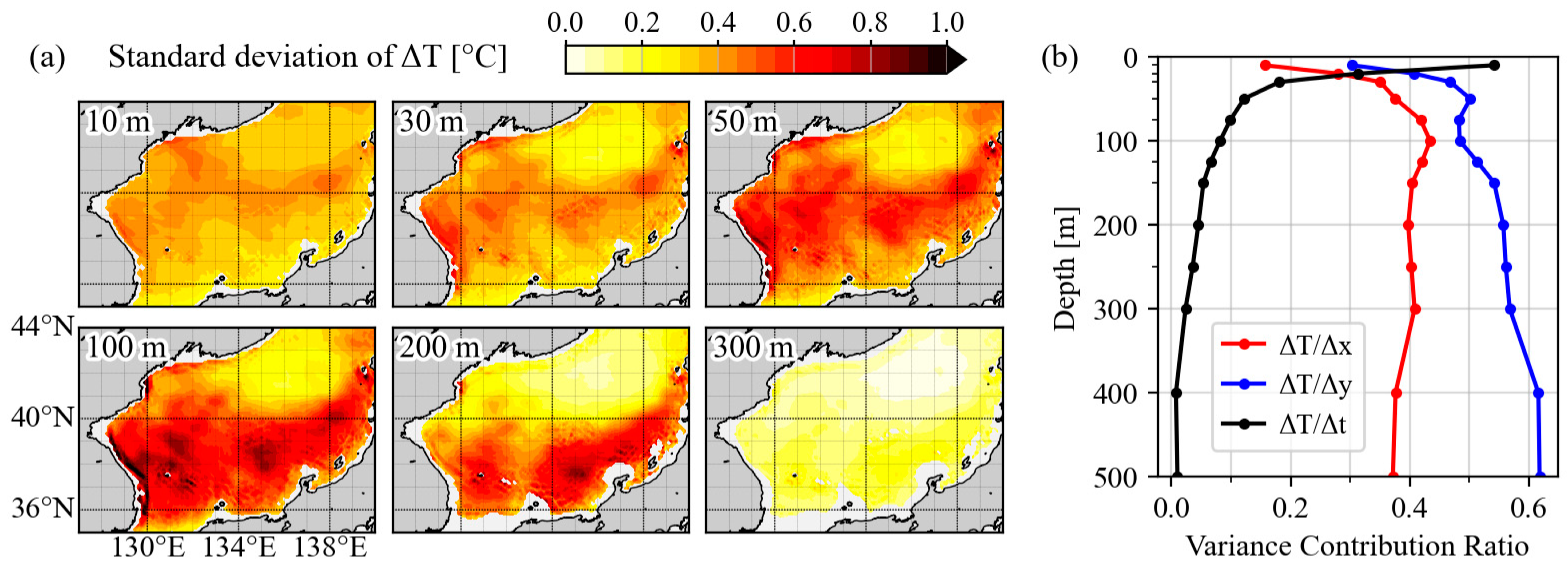

Although the ANN model predicts each temperature profile independently in both time and space (i.e., 10,812 points per day across the EJS), the outputs are concatenated to construct a four-dimensional (4-D) temperature field. This design raises concerns about potential discontinuities in the spatiotemporal domain. To assess the robustness of the reconstructed field, we quantified its continuity by analyzing temperature change variability (ΔT). Directional differences were first computed along longitude (ΔT/Δx), latitude (ΔT/Δy), and time (ΔT/Δt), representing zonal, meridional, and temporal variability, respectively. These were summed, and the standard deviation of the combined differences was used as a metric of spatiotemporal variability (Figure 9a). This analysis assumes that variability magnitudes across the three directions are of comparable order, which justifies using a simple summation. The maps display the standard deviation of total ΔT at six representative depths. The resulting patterns exhibit smoothness and depth-dependent structure across the EJS.

Figure 9.

(a) Horizontal maps of the standard deviation of ΔT (°C), where ΔT was calculated as the sum of directional differences in predicted 4-D temperature across longitude (ΔT/Δx), latitude (ΔT/Δy), and time (ΔT/Δt). (b) Variance contribution ratio for each directional component—ΔT/Δx (red), ΔT/Δy (blue), and ΔT/Δt (black)—as a function of depth. Each component was calculated over the entire EJS domain and normalized to sum to one at each depth.

To further examine the structure of variability, Figure 9b presents the variance contribution ratio as a function of depth. Each directional component—ΔT/Δx, ΔT/Δy, and ΔT/Δt—was computed across the entire EJS domain and experimental period, then normalized so that the sum equals one at each depth. Temporal variability dominates in the surface layers but declines sharply with depth. Conversely, the relative importance of spatial components gradually increases, particularly the meridional direction, reflecting suppressed high-frequency variability and an increasing significance of horizontal gradients in deeper waters. These depth-dependent transitions are consistently observed across the domain.

These vertical patterns are further elucidated in the spatial distribution of variance contributions shown in Figure S5, which presents the three directional components as depth-resolved horizontal maps. Consistent with the vertical profiles in Figure 9b, temporal variability dominates near the surface, whereas spatial variability, particularly in the meridional direction, becomes increasingly prominent in subsurface layers. Additionally, distinct spatial structures emerge in regions with complex bathymetry. For instance, elevated spatial gradients often appear as bands aligned with continental shelf and slope boundaries, indicating strong horizontal transitions. In other areas, such as the basin edge near 131°E, 37°N and the plateau boundary around 135°E, 40°N, wave-like patterns in variance contributions are observed.

3.4. Results of Long-Term Reconstruction

The verified ANN model weights, validated through various performance metrics (e.g., RMSE, RRMSE, and correlation), were applied to reconstruct daily 3-D temperature fields in the EJS over a 31-year period (1993–2023). The spatial domain spans from 35° to 44°N and 128° to 140°E, with a 1/12° resolution and 13 standard depth levels. Excluding land areas, each daily field includes 10,812 effective grid cells, resulting in over 100 million individual temperature profiles.

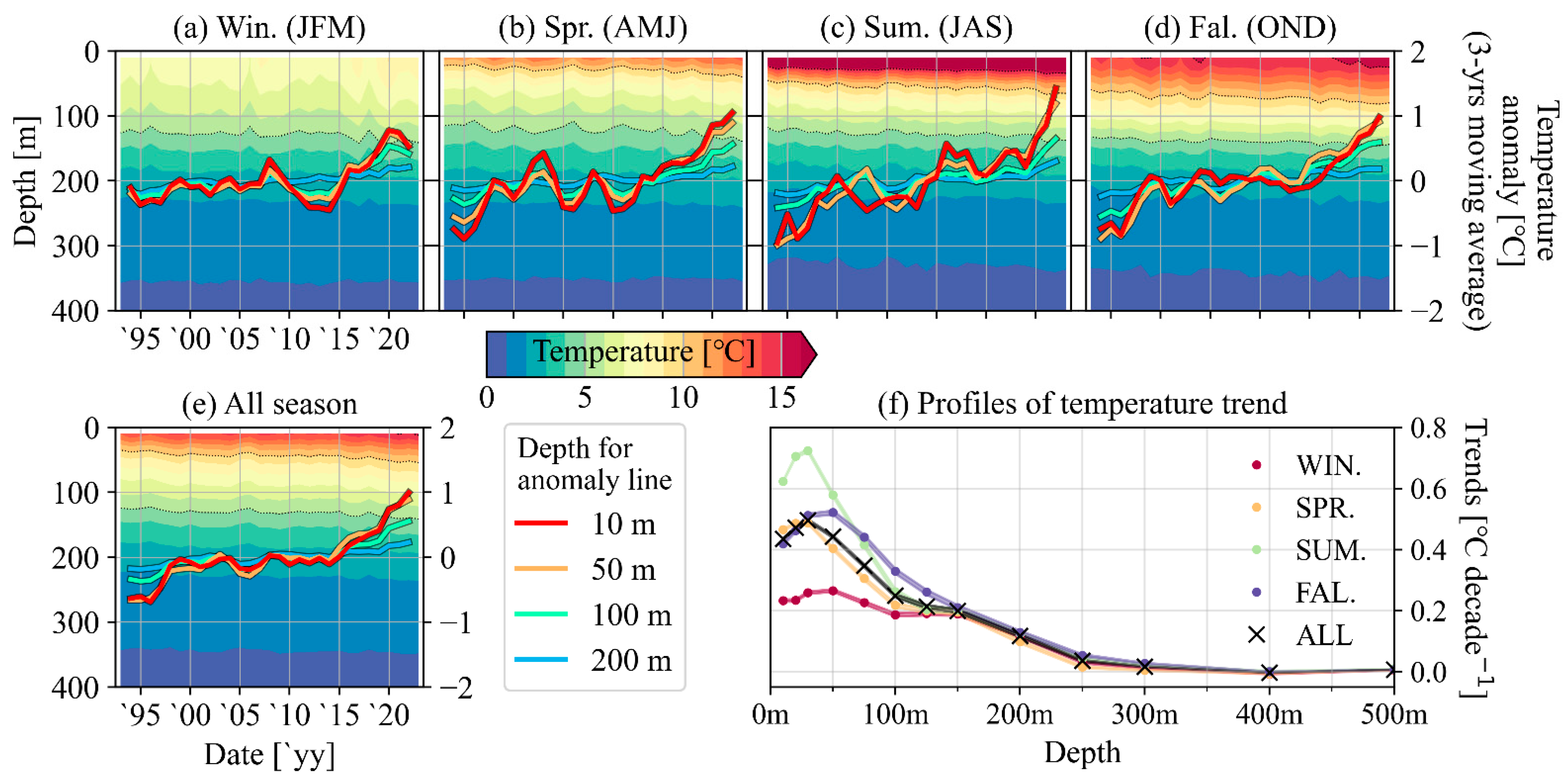

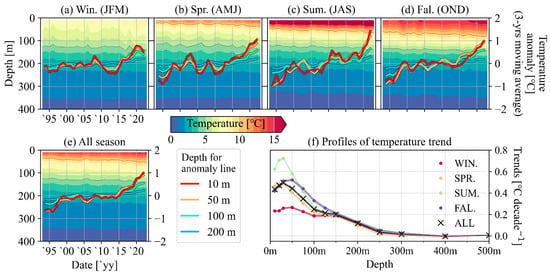

Figure 10 presents long-term changes in vertically resolved temperatures across the entire EJS from 1993 to 2023. The ANN model successfully captured both the seasonal variability and long-term trends for temperature in the sub-surface ocean. For example, ref. [28] demonstrated a strengthening of summer warmth and a weakening of winter cold based on long-term SST data, which is consistently revealed in our results (Figure 10a,c). Moreover, ref. [9] associated with wintertime marine heatwaves in the northwestern part of the EJS with the Arctic Oscillation, and the observed SST fluctuating trend in the reported study area is similarly reconstructed in the upper layer (up to 100 m) of our study region (Figure 10a). Additionally, there was a slowdown in the rate of temperature increase during the period known as the global warming hiatus (1998–2013) in the EJS (Figure 10e), consistent with the findings of [50]. Additionally, our model not only captures long-term trends but also specific events at certain times. A notable example is the increase in ocean temperature in the EJS due to the intensification of the EKWC reported by [51] during the summer of 2021.

Figure 10.

Seasonal and annual ocean temperature variability and trends in the EJS over the period 1993–2023. (a–e) show seasonal (JFM) and annual mean, respectively. Contours represent temperature distribution by depth, while overlaid lines show 3-year moving average temperature anomalies at depths of 10, 50, 100, and 200 m. (f) Vertical profiles of seasonal and annual temperature trends over 31 years. Symbols and colors indicate different seasons, and shaded areas represent 99% confidence intervals.

Reconstructed temperatures showed an upward trend over the past three decades across all seasons and depths (Figure 10f), as seen in the three-year moving average temperature anomaly. However, the increase rates varied seasonally and across different layers, with interannual variability. The trend of temperature demonstrates stronger warming in summer compared to winter, and at subsurface depths than near the surface. For instance, while the rate of temperature increase at the 10 m level during summer is 0.62 °C/decade, it is 13% higher at 20 m and 16% higher at 30 m, calculated as 0.71 °C/decade and 0.72 °C/decade, respectively.

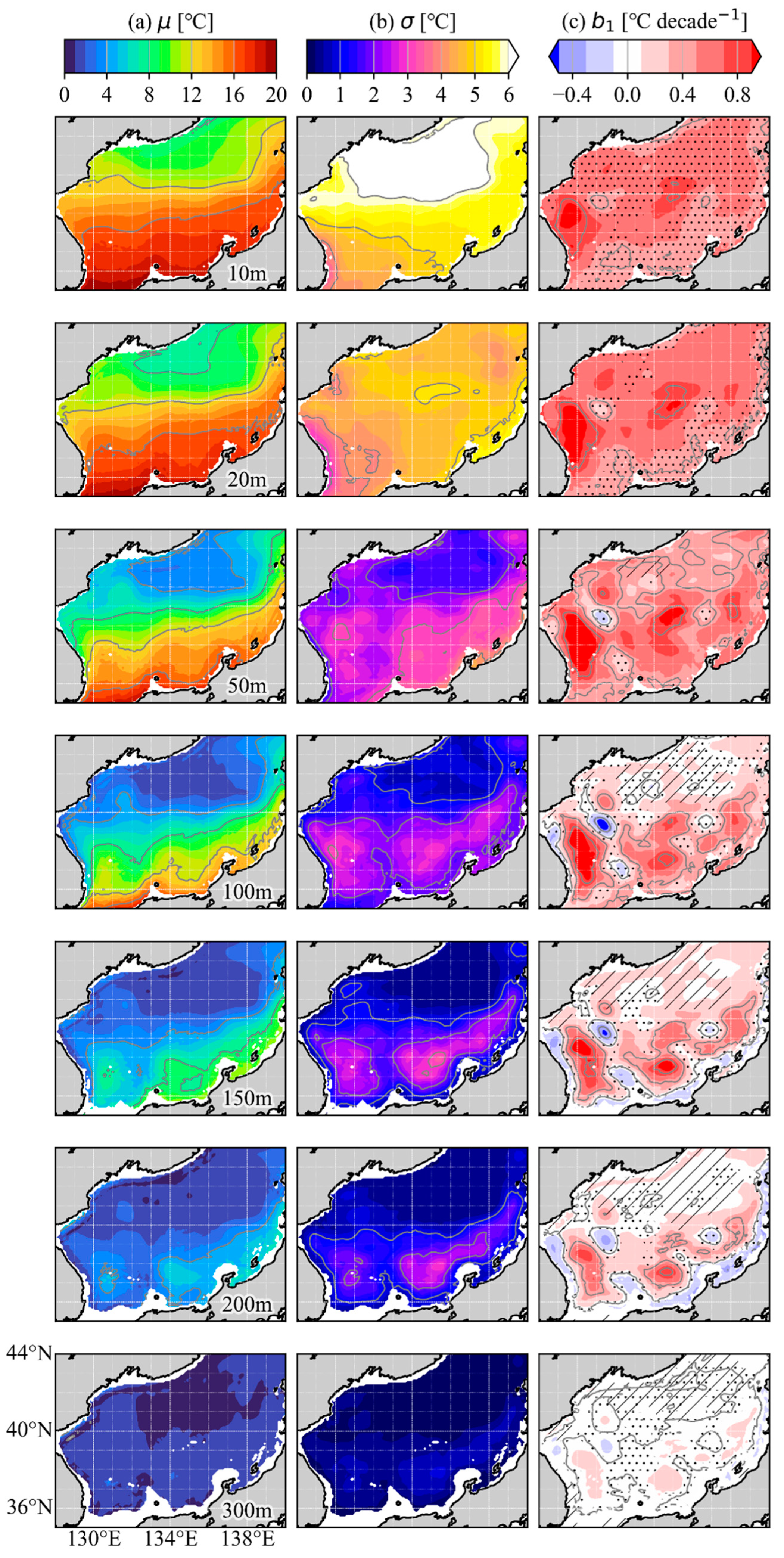

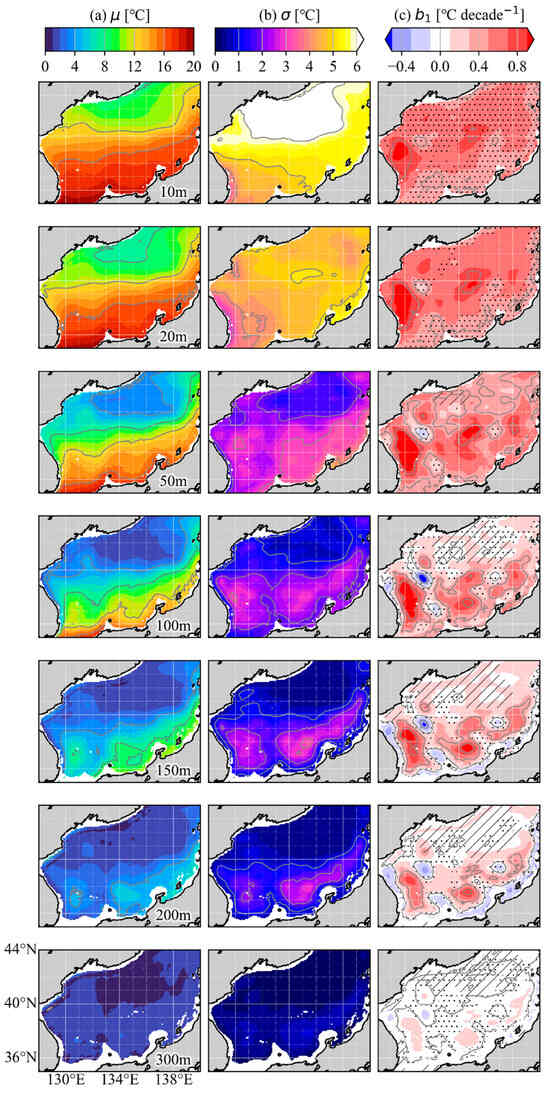

The 31-year mean temperature fields revealed clear depth-dependent spatial patterns in the EJS (Figure 11a). Near the surface, horizontally aligned isotherms dominate, while deeper layers exhibit increasingly complex spatial patterns. Distinct spatial contrasts between basin interiors and continental slope regions are evident with depth. The spatial patterns of standard deviation (σ) exhibit depth-dependent changes in the temperature field (Figure 11b). In the surface layers (10 m), meridionally aligned isotherms dominate, reflecting the large-scale thermal structure maintained by atmospheric forcing and boundary currents. At depths below 100 m, the standard deviation patterns closely resemble those of the mean field, with elevated variability observed in the Ulleung and Yamato Basins. This suggests that the southern EJS generally exhibits higher temperatures and greater variability than the northern EJS. Additionally, regions along the eastern coast of Korea exhibit lower variability, indicative of stable intermediate water behaving akin to Taylor columns along the continental shelf [37,52].

Figure 11.

Spatial distribution of 31-year ocean temperature statistics. (a) mean temperature (μ), (b) standard deviation (σ), and (c) linear temperature trend (b1). Dotted hatching indicates grid points with non-significant trends (p-value > 0.05), and dashed hatching denotes regions where relative RMSE exceeds 1, indicating high uncertainty.

The linear trend at each grid point was estimated using monthly mean data (372 months) (Figure 11c). The significance of these trends is indicated using hatching; the dotted hatching denotes regions with p-values greater than 0.05, while dashed hatching indicates areas where the relative RMSE (RRMSE) exceeds 1. An RRMSE above 1 means that the reconstruction error is larger than the natural variability at that grid point. Accordingly, the trends in these regions carry lower confidence and should be viewed with caution.

4. Discussion

4.1. Overall Performance and Generalization

The validation results demonstrate that the proposed ANN model achieves stable and consistent performance across both training and independent test years, indicating robust temporal generalization rather than simple interpolation within the training period (Figure 5; Table 3). Although the highest reconstruction errors occur around 125 m—likely due to increased intrinsic variability and limited observational constraints at this depth—the training RMSE (1.29 °C) remains close to the test RMSE (1.33 °C), suggesting that the model does not exhibit strong temporal overfitting. This stability is particularly important given that the test set consists of six years subsampled across the full 31-year period. The consistent error levels across these temporally separated years indicate that the ANN successfully captures persistent statistical relationships between surface forcing, circulation-related variables, and subsurface temperature structure, rather than memorizing specific temporal patterns. As a result, the reconstructed temperature fields are suitable for long-term physical analysis in the EJS, including variability and trend assessments.

The ensemble strategy further enhances temporal robustness. Compared to individual ANN members, the ensemble mean consistently exhibits lower RMSE and RRMSE values (Figure 5), reflecting reduced sensitivity to initialization and sampling variability. While ensemble averaging may suppress some fine-scale or extreme features, it effectively mitigates discontinuities arising from independently trained models, yielding temporally smoother and more stable reconstructions.

Depth-dependent error characteristics provide additional insight into temporal generalization. Although absolute RMSE peaks near the thermocline, relative RMSE (RRMSE) remains moderate at these depths, indicating that large errors are largely due to high natural variability rather than systematic model failure (Figure 5a,b). At greater depths, where temperature variability sharply decreases, all models—including HYCOM and GLORYS—struggle to reproduce weak gradients, with HYCOM exhibiting particularly high RRMSE values below 300 m. In contrast, the ANN maintains comparatively stable performance across depths, suggesting improved generalization in subsurface layers.

The superior performance of the ANN relative to data-assimilated numerical models can be attributed to its region-specific, data-driven design. While HYCOM and GLORYS are optimized for global applicability and rely on dynamical smoothing to maintain numerical stability, their ability to represent subsurface temperature in the EJS is constrained by limited assimilated observations below the surface. By contrast, the proposed ANN is explicitly trained on EJS-specific observations spanning multiple decades, enabling it to generalize learned vertical temperature relationships across untrained years and evolving climatic conditions.

Taken together, the consistent agreement between training and test performance (Table 3; Figure 5), the stable error characteristics across independent test datasets (Figure 6), and the ensemble-based uncertainty estimates demonstrate that the proposed ANN achieves robust temporal generalization beyond the training period. The physical meaning of this performance and the sources of uncertainty are discussed in the following sections.

4.2. Physical Interpretation of Key Predictors

The feature importance (FI) analysis provides physical insight into how the proposed ANN reconstructs subsurface temperature structure in the EJS and why it achieves robust performance across depths and seasons. Among all input variables, absolute dynamic topography (ADT), sea surface temperature (SST), and sea level anomaly (SLA) consistently exhibit the highest depth-averaged FI values (Figure 7a), indicating that variability in these surface-related predictors plays a dominant role in estimating subsurface thermal structure. In contrast, the remaining predictors contribute relatively weakly, suggesting that the reconstruction skill primarily emerges from a limited set of physically meaningful drivers rather than from high-dimensional input complexity, reducing the risk of spurious correlations (overfitting).

The particularly high importance of ADT—exceeding that of SST despite SST being a direct temperature measurement—highlights the role of large-scale dynamical constraints in shaping subsurface temperature variability in the EJS (Figure 7a). Previous studies have shown that dynamic height integrates information about the vertical density structure and can serve as an effective proxy for subsurface thermal variability in this region [53,54]. The strong contribution of ADT therefore suggests that the ANN implicitly exploits geostrophic balance and circulation-related signals encoded in sea surface height to infer temperature structure below the surface. Seasonal and depth-dependent FI profiles further clarify the physical mechanisms underlying model performance (Figure 7b). When averaged across all seasons, FI values for SST peak in the mixed layer and upper thermocline, reflecting the strong coupling between surface heating and near-surface temperature variability. During winter (JFM), when stratification weakens and the mixed layer deepens, the influence of SST extends to greater depths, consistent with enhanced vertical mixing [55]. This seasonal behavior aligns with the depth-dependent error characteristics observed in the validation results, where near-surface layers exhibit relatively low RMSE and RRMSE despite strong intrinsic variability (Figure 5).

ADT and SLA show complementary depth-dependent roles. While both variables are derived from sea surface height, their FI profiles indicate that they are not redundant. SLA, which represents short-term deviations from the mean dynamic topography, exhibits elevated importance in capturing anomalous subsurface structures associated with mesoscale variability and transient processes. In contrast, ADT appears to encode more stable, large-scale signals related to mean circulation pathways and spatial positioning. This distinction is further supported by ablation experiments (Figure 7c): removing either ADT or SLA degrades performance and results in underfitting, demonstrating that both variables contribute uniquely to subsurface temperature reconstruction.

The comparable performance of the reduced-input model using only ADT, SST, and SLA (Case 1) relative to the full model (Case 0) reinforces the interpretation that these predictors form the physical core of the reconstruction framework (Figure 7c). Rather than relying on numerous auxiliary inputs, the ANN primarily leverages physically interpretable surface forcing and circulation-related variables to generalize subsurface temperature structure across depths and seasons. Although nonlinear interactions among these predictors complicate direct attribution—particularly for SLA—the FI analysis confirms that their combined use enables the model to capture both mean-state and anomalous thermal features in the EJS.

Overall, the FI results suggest that the ANN’s reconstruction skill arises from its ability to integrate surface thermal forcing (SST), large-scale dynamical constraints (ADT), and transient sea level variability (SLA) in a physically consistent framework. This synergy explains the model’s stable performance across stratified and weakly stratified regimes and provides a mechanistic basis for the temporal generalization discussed in Section 4.1.

4.3. Uncertainty, Regional Limitations, and Coherence of the Reconstructed Field

Building on the performance and physical interpretation discussed above, the reliability of the reconstructed temperature field varies systematically with depth and region. Overall, the ANN reconstruction shows the highest confidence in the upper and mid-depth layers, particularly within the southern EJS, where observational coverage is dense and temperature variability is relatively well constrained (Figure 5 and Figure 8). In these regions, both absolute RMSE and relative RMSE remain low, and the confidence intervals derived from bootstrap analysis are narrow, indicating stable performance across independent test years. The consistency between training and test errors (Table 3) further supports the reliability of the reconstructed fields for long-term physical analysis in these well-observed layers.

At greater depths and in regions with sparse observations, uncertainty increases. The error analysis demonstrates that local reconstruction performance is primarily governed by two factors: the intrinsic variability of the observed temperature field and the spatial distribution of the target data (Figure 8; Figure S4). Regions characterized by strong mesoscale and submesoscale variability—such as areas of cold-water subduction (around 134°E, 42°N at 20–30 m; [46]), current separation of the EKWC (around 130°E, 35°N at 125–150 m; [12]), and internal wave propagation (around 132°E, 35°N at 125–150 m; [47,48,49])—exhibit elevated RMSE despite relatively moderate RRMSE values. This behavior reflects the tendency of the ANN to regress toward the central tendency of the data distribution when trained with a single global loss function, particularly in environments where temperature variability spans multiple temporal scales. In addition, aliasing between the daily model resolution and sub-daily observational variability may further contribute to localized errors in these dynamically active regions.

Data sparsity introduces an additional source of uncertainty, most clearly expressed in the northern EJS and at depths below approximately 300 m. While this limitation is not always evident in absolute RMSE, it becomes pronounced in the RRMSE distribution, where values exceeding unity indicate that reconstruction errors surpass the natural variability of the temperature field itself (Figure 8b). The wide confidence intervals associated with both RRMSE and temperature standard deviation in these regions suggest reduced generalization capability under limited observational constraints. Consequently, long-term trends inferred in such areas should be interpreted with caution.

Despite these regional and depth-dependent limitations, multiple lines of evidence indicate that the reconstructed temperature field retains strong spatiotemporal coherence at the basin scale. The continuity diagnostics reveal smooth and physically plausible patterns of temperature variability across longitude, latitude, and time, even though individual profiles are predicted independently (Figure 9a). The vertical distribution of variance contributions shows a gradual transition from temporally dominated variability near the surface to increasingly important spatial gradients at depth (Figure 9b), a structure that is consistent with established physical understanding of ocean stratification and circulation. Additional spatial maps of variance contributions further demonstrate that localized variability near complex bathymetry does not disrupt the overall coherence of the reconstructed field (Figure S5).

This coherence arises from several interacting factors. The remote sensing inputs inherently provide smooth and correlated spatiotemporal information, encouraging neighboring grid points to produce similar outputs. In addition, the ANN architecture and training strategy emphasize regularization, reducing the likelihood of generating spurious extremes or discontinuities. Static predictors such as bathymetry further constrain the spatial organization of temperature structures, particularly along continental shelves and basin boundaries. Although the resulting coherence reflects statistical rather than dynamical consistency—the model does not enforce conservation laws or governing equations—it is sufficient to support analyses of variability, trends, and large-scale circulation patterns.

Taken together, these results suggest that the reconstructed temperature fields are most suitable for basin-scale and regional analyses of long-term variability and trends, especially in the upper and mid-depth layers and in observation-rich regions of the EJS. In contrast, interpretations focused on deep layers or data-sparse regions should explicitly account for the elevated uncertainty quantified in the error and confidence interval analyses. Within these bounds, the ANN-based reconstruction provides a statistically consistent and physically interpretable representation of the evolving thermal structure of the EJS.

5. Conclusions

This study aims to estimate 3-D ocean temperature fields, including coastal areas, addressing the limitations of previous studies with low spatiotemporal resolution data or focusing solely on the ocean characteristics. To achieve this, we built a novel model that develops a masked loss function for learning various depths and a parallel model structure to consider data from multiple dimensions. Additionally, we employed an ensemble technique to enhance model stability. Overfitting was minimized, as evidenced by consistent performance between the training and test sets, ensuring reliable long-term ocean temperature reconstruction.

Validation was conducted for both long-term temperature reconstruction and short-term temperature prediction over three days. In both cases, the model exhibited successful temperature estimation, with RMSE of 1.33 °C or less, bias of 0.10 °C or less, and correlation of 0.82 or above on the test set. These results demonstrated that our ANN model was well-optimized for the EJS, rather than simply outperforming existing data-assimilated reanalysis models such as HYCOM and GLORYS. Furthermore, the ensemble approach demonstrated its effectiveness in enhancing model stability during the validation phase.

Beyond conventional performance metrics, identifying the model’s limitations is essential for practical applications of the reconstructed data. Therefore, we evaluated spatial errors across the entire EJS, including deeper layers. This analysis enabled us to infer the localized causes of error from the target data perspective. The first primary cause of large regional errors was the high intrinsic variability of temperature within the region, while the second was the uneven spatial distribution of observational data. Additionally, our continuity test for the reconstructed field confirmed that the model provided spatially and temporally smooth temperature predictions across the EJS.

Based on the validation and error analyses, the reconstructed temperature fields are most reliable in the upper and mid-depth layers (approximately 0–200 m), particularly in regions with dense observations in the southern EJS, where the model consistently shows low RMSE, low bias, and high correlation with independent data. In contrast, increased uncertainty is observed in the northern EJS and at deeper layers (below approximately 300 m), where observational coverage is sparse and intrinsic variability is high. In these regions, elevated relative RMSE and wider confidence intervals indicate that the reconstructed values, especially long-term trends, should be interpreted with caution.

Utilizing the validated model, this study reconstructed and analyzed a 3-decade (1993 to 2023) temperature field across 13 standard depths in the EJS. The reproduced field not only followed well with temperature trends revealed in previous studies in the EJS but also successfully captured oceanic events. Furthermore, spatial temperature variations over the 31 years exhibited different patterns locally as well as across the entire region. Particularly, near the surface layers influenced by the TWC and EKWC showed strong variability and a warming trend around 130°E, while a cooling trend at the deeper layer was calculated in the continental shelf region, including the eastern coast. These trends are consistent with a long-term reduction in the mass of intermediate water, potentially modifying the patterns of circulation and marine heatwaves in the EJS. It should be noted that the reconstructed fields exhibit statistical coherence rather than strict dynamical consistency, as the ANN does not impose physical conservation laws. Nevertheless, the reconstruction provides physically interpretable spatial–temporal patterns that are well suited for variability, trend, and circulation-related analyses.

The modeling framework developed in this study may be further extended for broader applications. Specifically, similar methods could be applied to reconstruct 3-D ocean salinity fields, including coastal regions, or to expand the temperature estimation range into the deep ocean. Such developments would enhance the completeness of the data product and broaden its relevance for climate-scale analyses. In terms of application, the reconstructed temperature field offers strong potential for investigating a wide range of oceanographic and climate-related phenomena. These include the structure and variability of ocean circulation across both coastal and interior regions, the influence of long-term climate forcing on the EJS, changes in upper ocean heat content, and extreme climate events such as marine heatwaves. In addition, the long-term consistency and vertical resolution of the data product make it well suited for practical integration into data assimilation systems in numerical ocean circulation models.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/rs18020246/s1, Table S1. Training and test RMSE of ANN models with different activation function configurations; Figure S1. Detailed architecture of the ANN model used to predict 13-level vertical temperature profiles, corresponding to the schematic overview in Figure 3. The leftmost column of boxes outlines the sequential model flow. Each box contains two rows: the first row shows the layer type and activation function, and the second row displays the TensorFlow layer name. Additional implementation details, including input composition and layer configuration, are described in the main text; Figure S2. Comparison of model performance under varying spatiotemporal input configurations. (a) RMSE for the training set, and (b) RMSE for the test set; colors indicate depth-averaged values. (c) Generalization loss rate is calculated as the ratio of the RMSE difference between the test and training sets to the training RMSE, with higher values indicating greater overfitting. The red box indicates the selected configuration: 1-day temporal input and a 13-grid spatial context (equivalent to 1°); Figure S3. Additional vertical temperature section comparisons between observation, ANN, HYCOM, and GLORYS. All sections were excluded from ANN training: (a) 1–4 July 1999 (CREAMS data), (b) 4–6 July 1999 (CREAMS data), (c) 7–11 August 1999 (CREAMS data), (d) 4–7 August 1999 (CREAMS data), (e) 3–7 November 2000 (Test year), (f) 3–7 November 2000 (Test year), (g) 10–14 May 2007 (CREAMS). (CREAMS). All other descriptions follow those in Figure 6; Figure S4. Supplementary maps supporting Figure 8. (a) Standard deviation of observed temperatures and (b) the number of observations used in the RMSE and RRMSE computations. All values were computed within grouped 1° × 1° grid cells. The 95% confidence interval (CI) width, computed using the chi-square distribution for (a), is visualized using three relative categories (low: 0.0–0.3, mid: 0.3–0.5, high: >0.5) shown as overlaid hatching. Color shading in (b) indicates the log-scaled number of observations per grid cell. Further explanation is provided in the main text; Figure S5. Spatially resolved variance contribution ratios of directional temperature differences: (a) zonal (ΔT/Δx), (b) meridional (ΔT/Δy), and (c) temporal (ΔT/Δt) components. These maps provide the spatial expansion of the vertical profiles shown in Figure 7b. All contributions were normalized at each depth so that the sum of three directions equals one.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.-J.L. and J.-H.P.; methodology, E.-J.L. and Y.-T.K.; software, E.-J.L.; validation, E.-J.L. and Y.H.; investigation, Y.H. and J.-H.P.; resources, Y.-T.K. and S.N.; data curation, E.-J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, E.-J.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.H., Y.-T.K., S.N. and J.-H.P.; visualization, E.-J.L.; supervision, J.-H.P.; project administration, J.-H.P.; funding acquisition, J.-H.P. and Y.-T.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government. (MSIT) (RS-2025-02263830).

Data Availability Statement

The training data used in this study include both publicly available datasets and in situ observational data, some of which are not publicly accessible. The reconstructed 3-D sea temperature fields generated in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and temporarily accessible via Google Drive (https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/133pZ95cbms1rY1EWPk_a0k6d7yofpzNu?usp=sharing; accessed on 3 January 2026). The estimation model codes and configuration scripts for the near-real-time sea temperature field generation are openly available on GitHub (https://github.com/EJLee58/EJS-temp-ANN; accessed on 3 January 2026). 1. Temperature profiles: Korea Oceanographic Data Center: https://www.nifs.go.kr/kodc/soo_list.kodc (accessed on 3 January 2026). Korea Hydrographic and Oceanographic Agency: not publicly available due to institutional policy restrictions. Japan Oceanographic Data Center: https://www.jodc.go.jp/vpage/scalar.html (accessed on 3 January 2026). Argo program: https://data-argo.ifremer.fr/geo/pacific_ocean (accessed on 3 January 2026). CREAMS: The CREAMS data used in this study are available on request. 2. Remote Sensing: OSTIA: https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/product/SST_GLO_SST_L4_NRT_OBSERVATIONS_010_001 (analysis; accessed on 3 January 2026) and https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/product/SST_GLO_SST_L4_REP_OBSERVATIONS_010_011 (reprocessed; accessed on 3 January 2026). AVISO: https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/product/SEALEVEL_GLO_PHY_L4_NRT_008_046 (near real time; accessed on 3 January 2026) and https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/product/SEALEVEL_GLO_PHY_L4_MY_008_047 (reprocessed; accessed on 3 January 2026). 3. Additional Input and Validation Data: World Ocean Atlas: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/world-ocean-atlas-2018/ (accessed on 3 January 2026). GEBCO: https://www.gebco.net/ (accessed on 3 January 2026). HYCOM: https://www.hycom.org/dataserver (accessed on 3 January 2026). GLORYS12V1: https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/product/GLOBAL_MULTIYEAR_PHY_001_030 (accessed on 3 January 2026).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the project titled “Study on Improving the Prediction Accuracy of Surface Currents and Sea Temperature Field around the Korean Peninsula Based on Artificial Intelligence (I)” funded by the Korea Hydrographic and Oceanographic Agency (KHOA). The authors also acknowledge the KHOA for providing valuable in situ profiles datasets used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 3-D/4-D | Three-/Four-Dimensional (Reconstructed Fields) |

| ADT | Absolute Dynamic Topography |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| Corr. Coef. | Correlation Coefficient |

| DEP | Depth (Bathymetry) |

| EJS | East/Japan Sea |

| FI | Feature Importance |

| GLR | Generalization Loss Rate |

| MDT | Mean Dynamic Topography |

| MLD | Mixed Layer Depth |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| RRMSE | Relative Root Mean Squared Error |

| SLA | Sea Level Anomaly |

| SST | Sea Surface Temperature |

| T_MA/T_AN | Monthly mean temperature and their anomalies |

| UGOSA | Zonal Geostrophic Velocity Anomaly |

| VGOSA | Meridional Geostrophic Velocity Anomaly |

References

- Takashi, I.; Kenzo, T. Mesoscale eddies in the Japan Sea. La mer 1988, 26, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Danchenkov, M.; Lobanov, V.; Riser, S.; Kim, K.; Takematsu, M.; Yoon, J.-H. A history of physical oceanographic research in the Japan/East Sea. Oceanography 2006, 19, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Kim, K.R.; Min, D.H.; Volkov, Y.; Yoon, J.H.; Takematsu, M. Warming and structural changes in the East (Japan) Sea: A clue to future changes in global oceans? Geophys. Res. Lett. 2001, 28, 3293–3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.O.; Kim, K.; Kim, Y.G.; Kim, K.R. Diagnosing long-term trends of the water mass properties in the East Sea (Sea of Japan). Geophys. Res. Lett. 2004, 31, L20306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkin, I.M. Rapid warming of large marine ecosystems. Prog. Oceanogr. 2009, 81, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.-H.; Breaker, L.C.; Tseng, Y.-H.; Yeh, S.-W. A temporal multiscale analysis of the waters off the east coast of South Korea over the past four decades. Terr. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. 2014, 25, 415–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobday, A.J.; Alexander, L.V.; Perkins, S.E.; Smale, D.A.; Straub, S.C.; Oliver, E.C.J.; Benthuysen, J.A.; Burrows, M.T.; Donat, M.G.; Feng, M.; et al. A hierarchical approach to defining marine heatwaves. Prog. Oceanogr. 2016, 141, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xu, T.; Fang, G.; Jiang, S.; Wang, G.; Wei, Z.; Wang, Y. Characteristics of marine heatwaves in the Japan/East Sea. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.-Y.; Kim, Y.-J.; Lee, E.-J.; Yeh, S.-W.; Park, J.-H.; Park, Y.-G. Wintertime sea surface temperature variability modulated by Arctic Oscillation in the northwestern part of the East/Japan Sea and its relationship with marine heatwaves. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1198418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saranya, J.S.; Nam, S. Subsurface evolution of three types of surface marine heatwaves over the East Sea (Japan Sea). Prog. Oceanogr. 2024, 222, 103226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.I.; Teague, W.J.; Lyu, S.J.; Perkins, H.T.; Lee, D.K.; Watts, D.R.; Kim, Y.B.; Mitchell, D.A.; Lee, C.M.; Kim, K. Circulation and currents in the southwestern East/Japan Sea: Overview and review. Prog. Oceanogr. 2004, 61, 105–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talley, L.; Min, D.-H.; Lobanov, V.; Luchin, V.; Ponomarev, V.; Salyuk, A.; Shcherbina, A.; Tishchenko, P.; Zhabin, I. Japan/East Sea water masses and their relation to the sea’s circulation. Oceanography 2006, 19, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teague, W.J.; Ko, D.S.; Jacobs, G.A.; Perkins, H.T.; Book, J.W.; Smith, S.R.; Chang, K.-I.; Suk, M.-S.; Kim, K.; Lyu, S.J.; et al. Currents through the Korea/Tsushima Strait. Oceanography 2006, 19, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Park, K.-A.; Park, J.-E.; Choi, B.-J.; Lee, S.-H.; Shin, H.-R.; Lee, S.-R.; Byun, D.-S.; Kang, B.; Lee, E. Schematic maps of ocean currents in the yellow sea and the East China Sea for science textbooks based on scientific knowledge from oceanic measurements (in Korean). J. Korean Soc. Oceanogr. 2017, 22, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Ji, R.; Park, H.J.; Feng, Z.; Jang, J.; Lee, C.l.; Kang, Y.-H.; Kang, C.-K. Impact of shifting Subpolar Front on phytoplankton dynamics in the western margin of East/Japan Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 790703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seung, Y.H. A dinamic consideration on the temperature distribution in the east coast of Korea in august. J. Oceanol. Soc. Korean 1974, 9, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Choi, J.-G.; Park, J.; Kwon, J.-I.; Kim, M.-H.; Jo, Y.-H. Upwelling processes driven by contributions from wind and current in the Southwest East Sea (Japan Sea). Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1165366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Chae, J.-Y.; Park, J.-H.; Kim, Y.T.; Kang, B.; Shin, C.-W.; Ha, H.K. Remote impacts of low-latitude oceanic climate on coastal upwelling in a marginal sea of the Northwestern Pacific. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2024, 69, 103344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Kim, K.-R.; Kim, Y.-G.; Cho, Y.-K.; Kang, D.-J.; Takematsu, M.; Volkov, Y. Water masses and decadal variability in the East Sea (Sea of Japan). Prog. Oceanogr. 2004, 61, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.A.; Kim, K.R. Unprecedented coastal upwelling in the East/Japan Sea and linkage to long-term large-scale variations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2010, 37, L09603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, D.-Y.; Choi, H.-W. A comparison of spatio-temporal variation pattern of sea surface temperature according to the regional scale in the south sea of Korea (in Korean). J. Korean Assoc. Geogr. Inf. Stud. 2011, 14, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shin, J.W.; Park, J.; Choi, J.G.; Jo, Y.H.; Kang, J.J.; Joo, H.; Lee, S.H. Variability of phytoplankton size structure in response to changes in coastal upwelling intensity in the southwestern East Sea. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2017, 122, 10262–10274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.T.; Chang, K.I.; Nam, S.; Rho, T.; Kang, D.J.; Lee, T.; Park, K.A.; Lobanov, V.; Kaplunenko, D.; Tishchenko, P.; et al. Re-initiation of bottom water formation in the East Sea (Japan Sea) in a warming world. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, I.-S.; Lee, J.-S. Change the annual amplitude of sea surface temperature due to climate change in a recent decade around the Korean peninsula. J. Korean Soc. Mar. Environ. Saf. 2020, 26, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. Long-term variability of the East Sea intermediate water thickness: Regime shift of intermediate layer in the mid-1990s. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 923093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Park, M.S.; Kwon, M.; Park, Y.G.; Kim, Y.H.; Choi, N. Rapidly changing East Asian marine heatwaves under a warming climate. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2023, 128, e2023JC019761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.-Y.; Park, K.-A. Change in the recent warming trend of sea surface emperature in the East Sea (Sea of Japan) over decades (1982–2018). Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Seo, S.; Jeon, C.; Park, J.-H.; Park, Y.-G.; Min, H.S. Evaluation of temperature and salinity fields of HYCOM reanalysis data in the East Sea. Ocean Polar Res. 2016, 38, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Peng, S.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Hou, Z.; Zhong, G. Applications of deep learning in physical oceanography: A comprehensive review. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1396322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Feng, Y.; Zhao, X.; Sun, C.; Hong, F.; Liu, C. A convolutional neural network using surface data to predict subsurface temperatures in the Pacific Ocean. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 172816–172829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardelli, B.B. A deep learning network to retrieve ocean hydrographic profiles from combined satellite and in situ measurements. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Yan, C.; Zhuang, W.; Zhang, W.; Yan, X.-H. Reconstruction of three-dimensional temperature and salinity fields from satellite observations. J. Geophys. Res. 2021, 126, e2021JC017605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]