Highlights

What are the main findings?

- We propose a Spectral–Spatial Graph Transformer Network (SSGTN), a dual-branch framework for hyperspectral image classification that combines local feature extraction with global context reasoning.

- The framework builds region-level graphs from superpixels, applies lightweight spectral denoising, and introduces a parameter-free Spectral–Spatial Shift Module (SSSM) to strengthen spectral–spatial feature interaction.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- With only 1% training samples, the proposed method achieves state-of-the-art performance on three benchmark datasets (Indian Pines, WHU-Hi-LongKou, and Houston2018).

- The results suggest that combining region-level structural modeling with global reasoning is an effective and efficient strategy for hyperspectral remote sensing under scarce labels, and may benefit other spectral–spatial learning problems.

Abstract

Hyperspectral image (HSI) classification is fundamental to a wide range of remote sensing applications, such as precision agriculture, environmental monitoring, and urban planning, because HSIs provide rich spectral signatures that enable the discrimination of subtle material differences. Deep learning approaches, including Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs), and Transformers, have achieved strong performance in learning spatial–spectral representations. However, these models often face difficulties in jointly modeling long-range dependencies, fine-grained local structures, and non-Euclidean spatial relationships, particularly when labeled training data are scarce. This paper proposes a Spectral–Spatial Graph Transformer Network (SSGTN), a dual-branch architecture that integrates superpixel-based graph modeling with Transformer-based global reasoning. SSGTN consists of four key components, namely (1) an LDA-SLIC superpixel graph construction module that preserves discriminative spectral–spatial structures while reducing computational complexity, (2) a lightweight spectral denoising module based on convolutions and batch normalization to suppress redundant and noisy bands, (3) a Spectral–Spatial Shift Module (SSSM) that enables efficient multi-scale feature fusion through channel-wise and spatial-wise shift operations, and (4) a dual-branch GCN-Transformer block that jointly models local graph topology and global spectral–spatial dependencies. Extensive experiments on three public HSI datasets (Indian Pines, WHU-Hi-LongKou, and Houston2018) under limited supervision (1% training samples) demonstrate that SSGTN consistently outperforms state-of-the-art CNN-, Transformer-, Mamba-, and GCN-based methods in overall accuracy, Average Accuracy, and the coefficient. The proposed framework provides an effective baseline for HSI classification under limited supervision and highlights the benefits of integrating graph-based structural priors with global contextual modeling.

1. Introduction

Hyperspectral images (HSIs) capture the continuous reflectance spectrum of surface materials across hundreds of narrow and contiguous spectral bands. As a result, a HSI can be represented as a three-dimensional data cube that combines spatial information ( pixels) with rich spectral signatures (B bands). This dense spectral resolution enables the discrimination of subtle material differences that are difficult to observe using conventional RGB or multispectral sensors. Therefore, HSIs are valuable for precision agriculture [1], environmental monitoring [2], mineral exploration [3], and urban studies [4]. Hyperspectral image classification (HSIC) is a central task in these applications, in which each pixel is assigned a semantic land-cover or material label to support large-scale mapping and automated decision support.

Early HSIC methods largely relied on handcrafted feature engineering and shallow classifiers. Techniques such as band selection [5], spectral derivatives [6], and linear dimensionality reduction (e.g., PCA and LDA) were commonly used to alleviate spectral redundancy and the curse of dimensionality. Spatial context was often incorporated through morphological profiles [7] or heuristic filtering. Although these approaches are interpretable, they have limited adaptability to complex nonlinear spectral mixing patterns, depend heavily on domain expertise, and often generalize poorly across diverse scenes [8]. These limitations are particularly pronounced in high-dimensional, spatially heterogeneous, and label-scarce environments. Beyond classification-oriented pipelines, non-deep-learning hyperspectral image analysis has also explored noise-aware weighting and outlier removal to improve the robustness of spectral–spatial criteria for object-based processing and scale selection [9].

The advent of deep learning has dramatically reshaped the HSIC landscape. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have become a dominant paradigm in this area. In particular, 2D CNNs [10] extract spatial textures from spectral bands, and 3D CNNs [11] jointly model spectral–spatial dependencies. Hybrid architectures such as HybridSN [12] further improve efficiency by combining 2D and 3D convolutions. Despite their success, CNNs are limited by local receptive fields and fixed grid processing, which restrict their ability to capture long-range dependencies and adapt to irregular object boundaries. To mitigate these limitations, Transformers have been introduced and use self-attention to model global contextual relationships across both spatial and spectral dimensions [13,14]. More recently, state–space models (SSMs) such as Mamba [15] have emerged as efficient alternatives to Transformers by offering linear complexity with global receptive fields. However, these sequence-based models can be sensitive to spectral noise, may not preserve fine-grained local structures, and do not explicitly model irregular spatial relationships.

In parallel, graph neural networks (GNNs) have gained traction due to their ability to model non-Euclidean relationships among pixels or superpixels. Early graph convolutional networks (GCNs) [16] demonstrated promising results in semi-supervised HSIC by propagating node features over adjacency graphs. Subsequent efforts introduced multi-scale GCNs [17], cross-attention GCNs [18], and object-based graph constructions [19] to enhance feature aggregation and boundary preservation. More recently, hybrid graph state–space models such as Graph Mamba [20] have bridged graph structural learning with sequence modeling. Nevertheless, graph-based approaches still face several fundamental challenges. First, graph convolutions primarily capture local connectivity and may fail to model long-range dependencies effectively. Second, graph construction is often heuristic and scene-dependent. Third, many models lack dynamic multi-scale fusion mechanisms and do not fully integrate spatial and spectral cues. Finally, spectral noise and redundancy can degrade input quality and reduce robustness.

To address these limitations, we propose the Spectral–Spatial Graph Transformer Network (SSGTN), a unified dual-branch architecture that integrates graph-based structural modeling with Transformer-based global reasoning. The proposed framework includes four key components. First, an LDA-SLIC superpixel graph construction module combines linear discriminant analysis (LDA) for spectral compaction with Simple Linear Iterative Clustering (SLIC) for spatially homogeneous region segmentation to obtain a structurally informed and computationally efficient graph representation. Second, a lightweight spectral denoising module based on convolutions and batch normalization suppresses redundant and noisy spectral bands while preserving discriminative features. Third, a Spectral–Spatial Shift Module (SSSM) performs cyclic shifts along spectral, height, and width dimensions to enable efficient multi-scale feature interaction without introducing additional parameters. Fourth, a dual-branch GCN-Transformer block jointly models local graph topology and global dependencies, where a spatial Transformer guided by GCNs captures long-range spatial information and a spectral Transformer models cross-band correlations; the two branches are fused through a residual graph convolution.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- We propose a novel dual-branch graph–Transformer hybrid architecture that jointly models local graph structures and global spectral–spatial dependencies, effectively overcoming the limitations of conventional single-paradigm models.

- We design a dynamic Spectral–Spatial Shift Module that enables efficient multi-dimensional feature fusion through parameter-free shift operations, enhancing the model’s ability to capture contextual interactions across scales.

- We develop a superpixel-driven graph construction strategy using LDA-SLIC, which adaptively captures spatial homogeneity and spectral discriminability while maintaining computational efficiency via sparse graph representations.

- We introduce a spectral denoising module that refines input representations through lightweight convolutions and normalization, improving robustness to spectral noise and redundancy.

- We conduct comprehensive experiments and ablation studies across multiple datasets and training regimes, validating the superiority, generality, and interpretability of SSGTN in HSI classification under limited supervision.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces related work in hyperspectral remote sensing image classification. Section 3 presents the proposed SSGTN architecture. Section 4 reports experimental results on three benchmark hyperspectral datasets. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper and outlines future research directions.

2. Related Work

In this section, we systematically review the evolution of deep learning-based hyperspectral image classification (HSIC) methods, which can be broadly categorized into convolutional, attention-based, and graph-based approaches. We highlight the strengths and limitations of each paradigm, paving the way to introduce our proposed Spectral–Spatial Graph Transformer Network (SSGTN).

2.1. CNN-Based Hyperspectral Image Classification Methods

Convolutional Neural Networks have become a cornerstone in HSIC due to their strong ability to extract spatially structured features [12,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. Early work by Hu et al. [10] demonstrated that 2D CNNs can effectively leverage local spatial textures within HSI patches, significantly improving classification accuracy over purely spectral methods. To better model the spectral–spatial dependencies inherent in HSIs, Li et al. [11] extended CNNs to three dimensions and proposed 3D CNNs that jointly process spectral cubes. Further innovations led to hybrid architectures, such as the synergistic 2D/3D CNN by Yang et al. [30], which integrates spectral–spatial fusion through 3D convolutions and uses complementary 2D spatial context modeling to balance accuracy and computational efficiency. Overall, these developments reflect a progression from purely spatial 2D CNNs to more advanced 3D and hybrid architectures for comprehensive spectral–spatial integration.

Despite these advances, CNN-based methods exhibit several intrinsic limitations. Standard 2D-CNNs often disrupt spectral continuity by treating bands independently, leading to potential misclassification of spectrally similar materials. While 3D-CNNs can preserve spectral–spatial coherence, they dramatically increase model size and computational burden, creating scalability issues for high-dimensional HSIs. Moreover, the fixed receptive fields and inherently local inductive biases of convolutional kernels restrict their ability to capture long-range dependencies and multi-scale contextual information. These limitations hinder the generalization of CNN-based models in heterogeneous environments and motivate the exploration of more flexible architectures beyond convolution.

2.2. Attention-Based Hyperspectral Image Classification Methods

To overcome the locality bias of convolutions, attention-based architectures have been introduced into HSIC to model long-range spatial–spectral dependencies [13,15,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. Representative examples include Transformers and, more recently, state–space models such as Mamba. For instance, Hong et al. [14] proposed SpectralFormer to strengthen inter-band relationships via self-attention, yielding competitive gains over convolutional baselines. Gu et al. [39] designed a multi-scale lightweight Transformer to reduce computational cost while preserving global modeling capacity. On the state–space side, He et al. [15] introduced 3DSS-Mamba, which organizes spectral–spatial tokens for efficient long-range dependency modeling. CenterMamba [38] adopts a center-scan strategy to enhance semantic representation with linear-complexity sequence processing. These designs provide two complementary approaches to scalable global spatial–spectral representation learning in HSIC.

Notwithstanding their progress, attention-based approaches still face several limitations. First, Transformer models can be computationally demanding and may struggle to reconcile global dependency modeling with fine-grained local detail, especially under high spectral dimensionality and limited labels. Second, many Transformer pipelines rely on fixed tokenization or single-scale processing, leading to insufficient dynamic multi-scale adaptation across heterogeneous scenes. Third, both Transformers and Mamba variants can be sensitive to spectral redundancy and noise, benefiting from explicit denoising or channel re-weighting to stabilize training. Finally, while Mamba/SSM models offer efficiency gains, they may suffer from slow convergence and hyper-parameter sensitivity, and by design, they do not explicitly account for irregular spatial relations. These shortcomings have spurred increasing interest in graph-based architectures, which provide a more flexible representation for non-Euclidean spatial–spectral structures.

2.3. Graph-Based Hyperspectral Image Classification Methods

Graph-based methods have recently emerged as powerful tools for HSIC because they can represent spatial–spectral relations on irregular and non-Euclidean domains [16,19,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47]. Early studies demonstrated that graph convolutional networks can capture contextual dependencies through message passing over pixels or superpixels [16]. Subsequent advances introduced more adaptive designs. For example, Wan et al. [17] proposed a multi-scale dynamic GCN that aggregates information across spatial neighborhoods, while Yang et al. [18] introduced a cross-attention-driven spatial–spectral GCN to better integrate heterogeneous features. More recently, object-based strategies such as MOB-GCN [19] have further emphasized multi-scale structural cues, improving boundary delineation and robustness to noise.

Building on these advances, researchers have extended attention mechanisms to graph formulations. Zheng et al. [48] proposed a graph Transformer that fuses spatial–spectral features via self-attention to enhance long-range dependency modeling. In parallel, Ahmad et al. [20] introduced a hybrid Graph Mamba model that tokenizes hyperspectral data into graph representations and leverages state–space modeling to balance efficiency and global context capture.

Although graph-based methods have significantly advanced hyperspectral image classification, they remain constrained by several factors. First, neighborhood aggregation in graph convolutions primarily captures local connectivity, limiting the capture of complex long-range dependencies. Second, graph construction is often heuristic and scene-dependent, reducing adaptability across diverse scenes. Third, most models process features at fixed scales, hindering their adaptability from heterogeneous spatial–spectral patterns. Fourth, spatial and spectral cues are not always effectively integrated, leading to suboptimal joint representations. Finally, redundant or noisy bands degrade input quality and reduce classification robustness, particularly under scarce supervision. These challenges highlight the need for a more integrated approach that combines the strengths of graph structural learning with dynamic multi-scale fusion and global dependency modeling.

The proposed SSGTN is designed to address the aforementioned limitations in a unified framework. Unlike CNNs, SSGTN captures long-range dependencies via Transformer blocks while preserving local structure through graph convolutions. In contrast to pure Transformers, it incorporates an LDA-SLIC superpixel graph to model non-Euclidean spatial relationships and employs a spectral denoising module to enhance input representations. Compared to existing graph-based methods, SSGTN introduces a novel Spectral–Spatial Shift Module for dynamic multi-scale feature fusion and a dual-branch GCN-Transformer architecture to jointly model local topology and global dependencies. By synergistically integrating adaptive graph priors, spectral purification, shift-based feature interaction, and Transformer-based global reasoning, SSGTN achieves expressive and efficient hyperspectral representation learning under high-dimensional and structurally complex conditions, particularly under limited supervision.

3. Materials and Methods

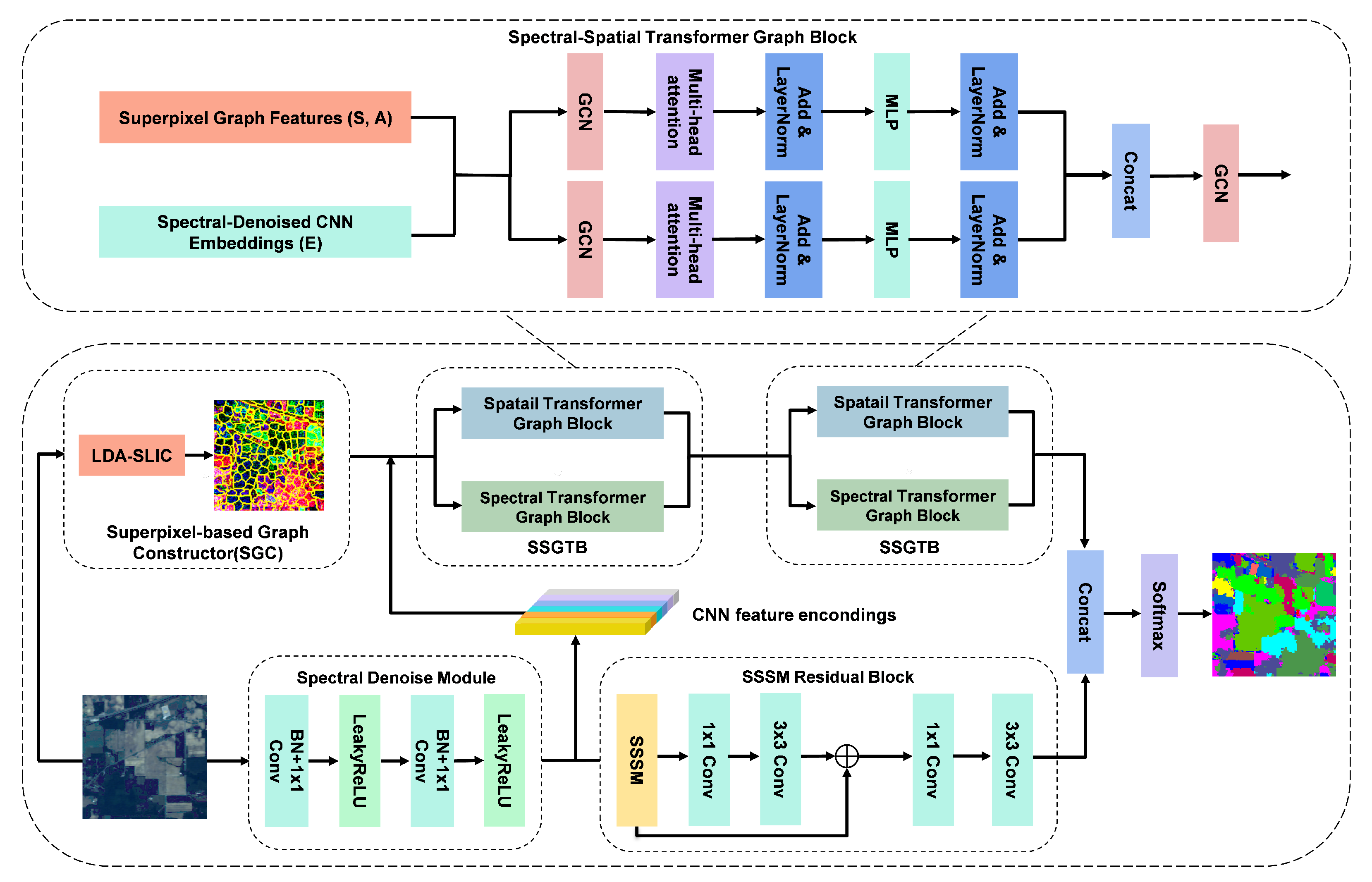

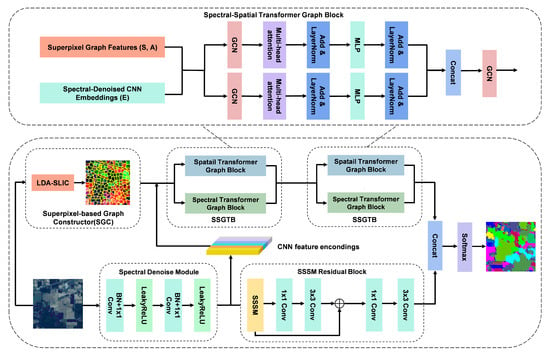

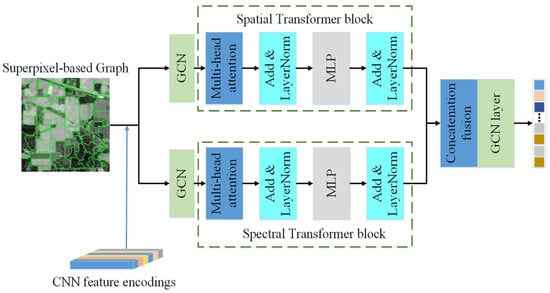

The overall architecture of the proposed SSGTN is depicted in Figure 1. This hybrid framework synergistically integrates convolutional operations for local feature extraction, graph convolutions for topological modeling, and Transformer blocks for global dependency learning. The network comprises four meticulously designed components: (1) LDA-SLIC superpixel segmentation with graph construction (inspired by the superpixel-based graph modeling paradigm in CEGCN [42]), (2) spectral denoising module, (3) Spectral–Spatial Shift Module, and (4) dual-branch spectral–spatial GCN-Transformer module. Each component addresses specific challenges in hyperspectral image classification while maintaining computational efficiency.

Figure 1.

Overall architecture of the proposed SSGTN. The framework integrates four key components: (1) LDA-SLIC superpixel segmentation for graph construction, (2) spectral denoising module for noise suppression, (3) Spectral–Spatial Shift Module for multi-scale feature fusion, and (4) dual-branch GCN-Transformer module for joint local and global dependency modeling.

3.1. LDA-SLIC Superpixel Segmentation Module

The LDA-SLIC module integrates Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) for spectral dimensionality reduction with Simple Linear Iterative Clustering (SLIC) for spatial superpixel segmentation, providing a compact, class-discriminative representation while producing spatially homogeneous regions that serve as graph nodes.

3.1.1. LDA-Based Spectral Dimensionality Reduction

Given an input hyperspectral image with sparse supervision , LDA projects the spectral data into a lower-dimensional subspace by maximizing inter-class separability:

where denotes the projection matrix learned by maximizing the Fisher criterion [49] , with and representing between-class and within-class scatter matrices, respectively. In practice, LDA is fitted only on the labeled training pixels (1% of the image in our low-label setting), while all unlabeled, validation, and test pixels are treated as background and excluded from the optimization, preventing any information leakage from the test set. The resulting projection reduces the spectral dimensionality from B to at most, class-discriminative components, which are then applied to the entire cube. Because LDA is a shallow linear transformation and the main model capacity resides in the subsequent CNN-GCN-Transformer modules, this supervised pre-processing acts as a light-weight spectral pre-conditioning step rather than a deep classifier, empirically yielding stable performance across different random training splits even under limited supervision.

3.1.2. SLIC Superpixel Segmentation

The dimension-reduced representation is subsequently partitioned into superpixels using the Simple Linear Iterative Clustering (SLIC) algorithm [50]. SLIC operates by iteratively optimizing a composite distance metric in the joint spectral–spatial domain:

where controls the trade-off between spectral similarity and spatial proximity, m is the compactness parameter, and is the nominal grid interval associated with the target number of superpixels K. The scale (or equivalently K) determines the expected number of pixels per superpixel and hence the granularity of the graph, while the compactness parameter governs whether regions adhere more closely to spectral boundaries (small m) or favor smoother, more spatially regular shapes (large m). We deliberately choose a moderately fine scale and balanced compactness so that mixed pixels and small objects are not overly merged, and each superpixel remains approximately homogeneous in the LDA space. It is important to note that the superpixels are used to define region-level nodes and the sparsity pattern of the graph, but final predictions are produced at the pixel level by fusing the graph branch with a parallel CNN branch. In particular, the CNN and SSSM modules operate directly on the full-resolution pixel grid and preserve fine-grained local details, while the dual-branch GCN-Transformer stack captures long-range and nonlinear spectral–spatial dependencies on the superpixel graph. As a result, LDA-SLIC provides a stable structural prior that is complemented and refined by deeper, nonlinear feature learning in the downstream network.

3.1.3. Graph Representation Learning

To capture region-level interactions while keeping computation tractable, we construct a superpixel graph where each node corresponds to a superpixel region , and edges are defined only between spatially adjacent regions. The node feature matrix is computed by averaging the LDA-projected hyperspectral features within each region. This step reduces the spectral dimensionality to a compact, class-discriminative space and substantially lowers the memory requirements of subsequent graph operations. Based on these region features, we construct an initial adjacency matrix using a Gaussian kernel constrained by spatial neighborhood:

Since each superpixel interacts only with its directly bordering regions, the resulting adjacency is naturally sparse, and the number of non-zero entries scales linearly with the number of superpixels. Graph operations therefore scale with rather than , where denotes the small node degree induced by the superpixel topology.

The kernel bandwidth is determined in a simple data-dependent way: is estimated as the median distance between each superpixel and its spatial neighbors, yielding . In practice, the Gaussian-weighted adjacency serves as a structural prior and sparsity pattern rather than the final propagation operator. Within the GCN layer, we refine the edge weights by first projecting batch-normalized node features through a linear mapping to obtain feature embeddings, computing a learned affinity matrix via a sigmoid of the pairwise inner products, and then applying the sparsity mask from . A row-wise softmax yields a stochastic propagation matrix that preserves the superpixel topology while allowing data-driven adjustment of edge strengths.

3.2. Spectral Denoising Module

The spectral denoising module is designed as a lightweight feature refinement cascade to suppress spectral noise while preserving discriminative band correlations. Given an input hyperspectral cube , the module applies two sequential stages, each consisting of batch normalization (BN) and convolution for spectral filtering and dimensionality reduction:

where denotes channel-wise batch normalization with learnable affine parameters, and represents a convolution that reduces spectral dimensionality () while acting as an adaptive spectral filter. This design effectively mitigates spectral noise and redundancy while maintaining computational efficiency.

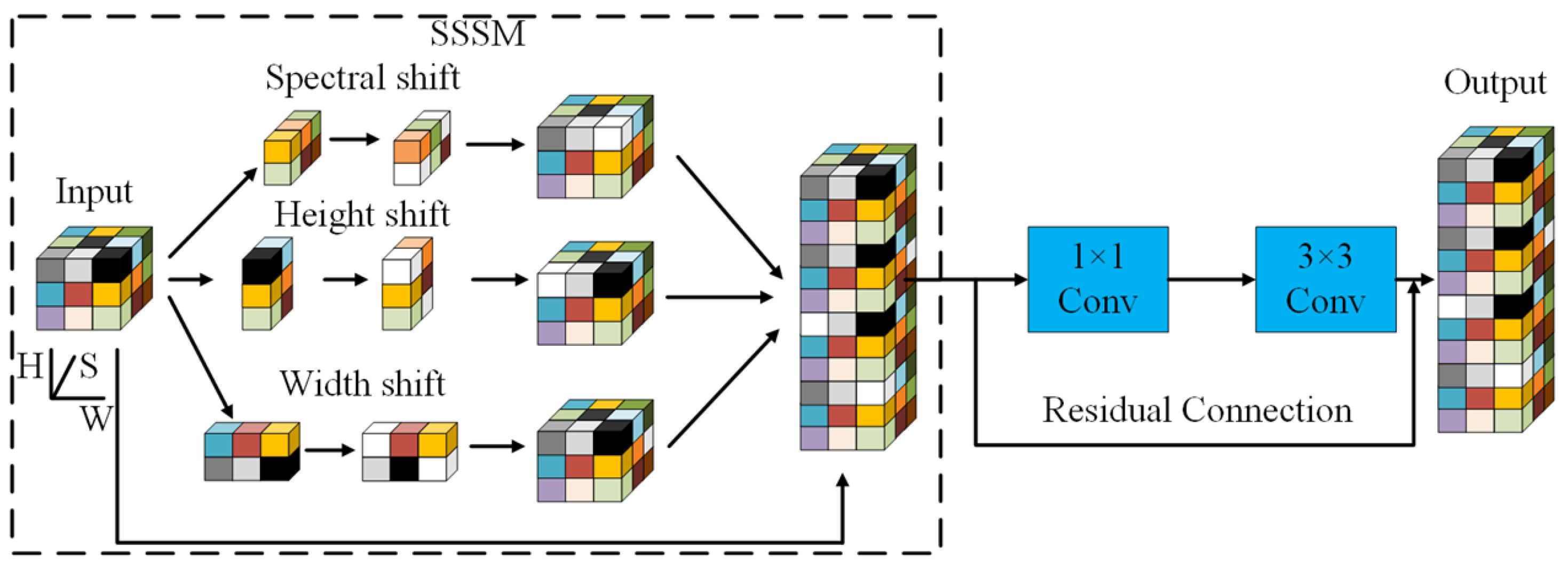

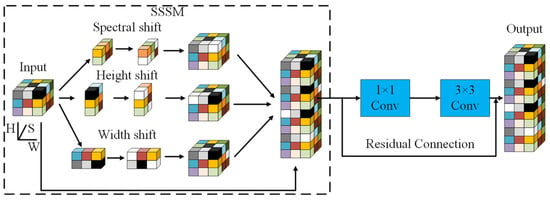

3.3. SSSM Residual Convolution Module

The SSSM module (as shown in Figure 2) enables efficient multi-dimensional feature interaction through parameter-free shift operations. For an input tensor , we define cyclic shift operators along three dimensions:

Figure 2.

Detailed structure of the Spectral–Spatial Shift Module. The module performs cyclic shifts along spectral (S), height (H), and width (W) dimensions, followed by concatenation and convolutional fusion. The residual connection preserves gradient flow and stabilizes training. Shift operations enable efficient cross-dimensional interaction without introducing additional parameters.

These shifted features are concatenated with the original input along the channel dimension:

The concatenated features are then processed by a convolution followed by a convolution for effective feature fusion and extraction, producing . A residual connection is employed to enhance representation capacity and alleviate gradient vanishing as follows:

This design facilitates comprehensive spectral–spatial interaction without introducing additional parameters, making it computationally efficient for high-dimensional HSI data.

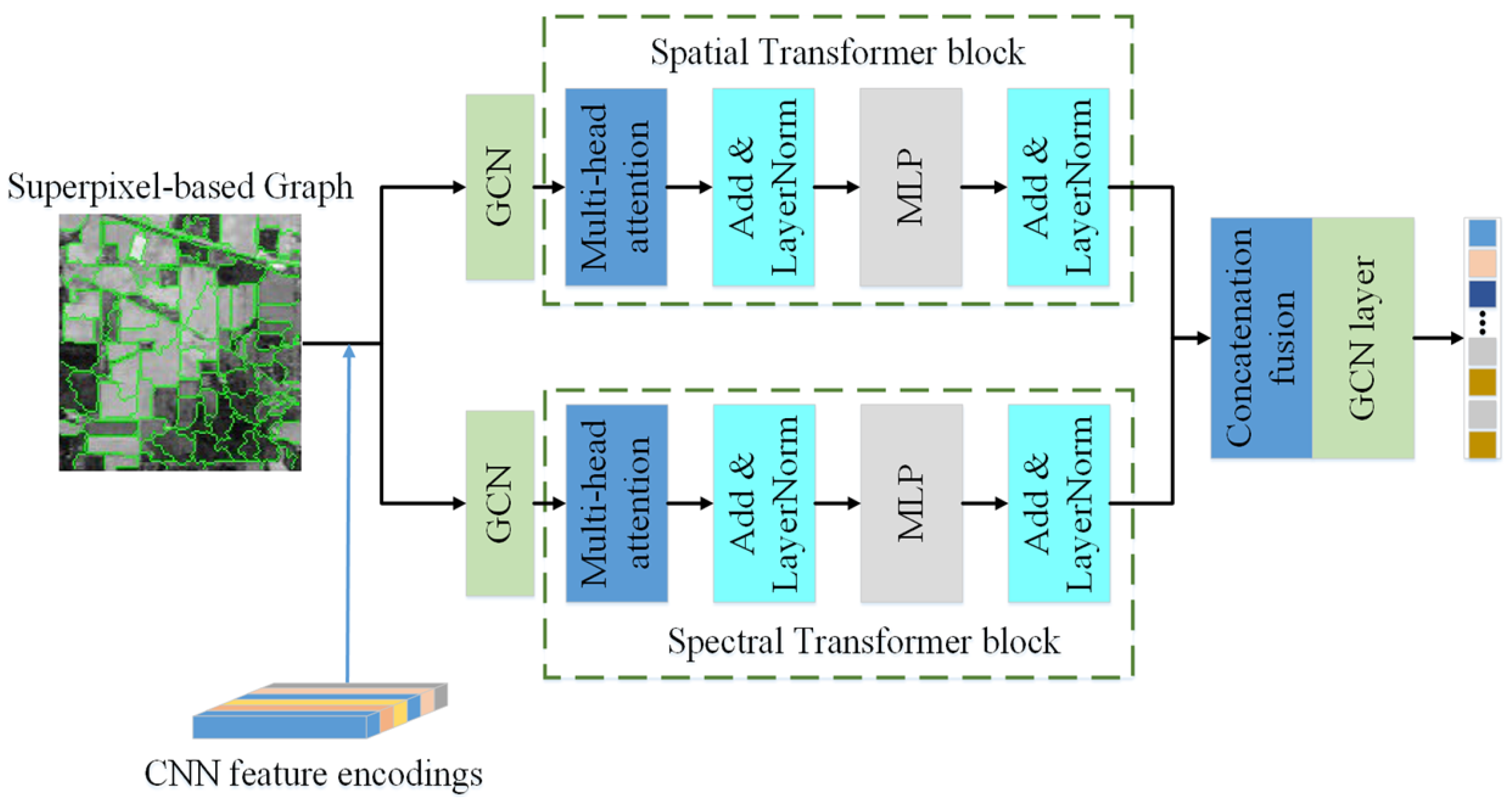

3.4. Dual-Branch Spectral–Spatial GCN-Transformer

The dual-branch module constitutes the core of SSGTN (as shown in Figure 3), designed to jointly model local graph structures and global dependencies. We initialize the node embeddings as , where denotes learnable positional encodings. The superpixel-level features are obtained by aggregating pixel representations after the spectral denoising and SSSM modules using the normalized assignment matrix :

which averages pixel features within each superpixel to form node descriptors for the dual-branch graph–Transformer module, as shown in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 Dual-Branch Spectral–Spatial GCN-Transformer (SSGTB) |

| Require: Superpixel node features ; adjacency matrix ; positional encodings ; layer number L; dropout rate p Ensure: Final node features

|

Figure 3.

Architecture of the dual-branch spectral–spatial Graph Transformer block. The spatial path (top) processes graph-convolved features through multi-head self-attention to capture long-range spatial dependencies. The spectral path (bottom) employs similar mechanisms for cross-band correlation modeling. Both branches are fused via concatenation and graph convolution, with layer normalization and residual connections applied throughout.

3.4.1. Spatial Path

The spatial path captures long-range spatial dependencies through graph-contextualized self-attention:

where denotes the normalized adjacency matrix with self-loops [51], MHSA represents multi-head self-attention [52], LN is layer normalization, and FFN is a position-wise feed-forward network.

3.4.2. Spectral Path

The spectral path focuses on cross-band correlations through spectral attention mechanisms:

3.4.3. Feature Fusion and Propagation

The outputs from both paths are integrated through concatenation and graph-convolutional fusion:

After L layers, the final node representations are projected back to pixel space using the assignment matrix for classification:

This architecture enables SSGTN to capture complementary information: graph convolutions encode local structural priors, while self-attention mechanisms model long-range spatial and spectral dependencies, resulting in a comprehensive representation for hyperspectral image classification.

4. Results

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed SSGTN framework, we conduct extensive experiments on three benchmark hyperspectral datasets with diverse spatial resolutions, spectral configurations, and land-cover characteristics.

4.1. Datasets

4.1.1. Indian Pines

The Indian Pines dataset was acquired by the Airborne Visible/Infrared Imaging Spectrometer (AVIRIS) sensor over an agricultural area in Northwestern Indiana. The dataset comprises pixels with 224 spectral bands in the wavelength range of 400–2500 nm. After removing noisy and water-absorption bands, 200 spectral bands are retained for analysis. The spatial resolution is 20 m per pixel, and the scene contains 16 distinct land-cover classes, primarily consisting of various crop types, forests, and natural vegetation. This dataset presents challenges due to its moderate spatial resolution and significant spectral similarities between different crop species.

4.1.2. WHU-Hi-LongKou

The WHU-Hi-LongKou dataset was collected by a Headwall Nano-Hyperspec imaging sensor mounted on a DJI Matrice 600 Pro UAV platform. The imagery covers pixels with 270 spectral bands spanning the visible to near-infrared spectrum (400–1000 nm). With a high spatial resolution of 0.463 m, this dataset captures detailed agricultural patterns in Longkou, Hubei, China. It encompasses nine land-cover classes including various crop types (corn, cotton, and rice) and water bodies, totaling 204,542 labeled pixels. The high spatial resolution and rich spectral information make this dataset suitable for evaluating fine-grained classification performance.

4.1.3. Houston2018

The Houston2018 dataset was provided as part of the 2018 IEEE GRSS Data Fusion Contest, covering an urban–rural area in Houston, Texas. The dataset consists of pixels with 50 spectral bands in the 380–1050 nm range at 2.5 m spatial resolution. It includes 20 land-cover classes with significant class imbalance, ranging from abundant categories like healthy grass (9799 samples) to rare classes such as synthetic turf (684 samples). The total of 504,856 labeled pixels and the complex urban landscape make this dataset particularly challenging for classification algorithms.

4.2. Experimental Setup

4.2.1. Evaluation Metrics

We employ four standard evaluation metrics to comprehensively assess classification performance from different perspectives. Overall Accuracy (OA) measures the global classification correctness:

where N is the total number of test samples, and denote the true and predicted labels, respectively, and is the indicator function.

Average Accuracy (AA) computes the mean of per-class accuracies, providing a balanced performance assessment across classes:

where C is the number of classes, and and represent true positives and false negatives for class i.

The Kappa coefficient () quantifies classification agreement beyond chance:

Per-class accuracy provides detailed insights into individual class performance:

4.2.2. Implementation Details

All experiments are conducted on a computational platform equipped with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPU and Intel Xeon Silver 4310 CPU. To rigorously evaluate model performance under limited supervision, we adopt only 1% of labeled pixels per class (minimum one sample per class) for training, with an additional 1% for validation and the remaining 98% for testing. The validation set is used exclusively for early stopping and checkpoint selection (patience = 100), and the checkpoint with the best validation performance is used for final testing. The model is implemented using PyTorch 2.9.1 and trained for 600 epochs with the Adam optimizer, employing an initial learning rate of with cosine annealing scheduling. No external pretraining, data augmentation, or other additional training techniques are used, and no extra pre-processing beyond what is described in this manuscript is applied. The superpixel graph construction uses superpixels for Indian Pines and WHU-Hi-LongKou, and for Houston2018, with compactness parameter unless otherwise specified.

4.2.3. Benchmark Methods

We compare SSGTN against twelve state-of-the-art methods spanning four representative paradigms:

- CNN-based methods: CNN-2D [10] extracts spatial features through cascaded 2D convolutions; SSRN [12] employs 3D convolutional layers for joint spectral–spatial modeling; HybridSN [12] integrates 2D and 3D convolutions for hierarchical feature extraction.

- Transformer-based methods: SSFTT [31] utilizes spectral–spatial feature tokenization for sequence modeling; MorphFormer [33] incorporates morphological operations with Transformer architecture.

- Mamba-based methods: Mamba-HSI adapts state–space models for hyperspectral imaging; MFormer [15] combines Mamba with Transformer components for long-range dependency modeling.

- GCN-based methods: GCN [16] operates on superpixel-based graphs; CEGCN [42] enhances graph representations with CNN features; GraphMamba [20] integrates graph structures with state–space models.

For a fair comparison, all baseline methods are trained and evaluated using the training protocol as described in the previous subsection, while method-specific hyperparameters are set following the recommendations in the original papers or official repositories, and all other common settings are kept identical across methods.

4.3. Ablation Studies

4.3.1. Impact of Spectral–Spatial Graph Parameters

In the LDA-SLIC superpixel construction, the scale and compactness parameters jointly determine the granularity and regularity of the induced superpixel graph. The parameter study in Table 1 and Table 2 reveals a consistent trade-off: overly fine segmentation tends to generate small, fragmented regions whose descriptors are more vulnerable to spectral noise and mixed pixels, whereas overly coarse segmentation increases region heterogeneity and blurs class boundaries, weakening the homogeneity assumption underlying region-level graph reasoning. The compactness parameter further mediates boundary adherence versus spatial regularity; moderate compactness typically preserves meaningful object contours while avoiding irregular, elongated superpixels that may distort adjacency relations. Notably, the sensitivity to these parameters is dataset-dependent: scenes with clearer object extents and higher spatial resolution exhibit a wider feasible range, while coarse-resolution agricultural scenes with high inter-class spectral similarity require a more careful balance to reduce mixed superpixels. Overall, these observations motivate selecting a moderately fine graph granularity together with boundary-aware superpixels to best support subsequent graph propagation and global reasoning.

Table 1.

Comprehensive parameter analysis on the Indian Pines dataset: performance metrics (OA, AA, in %) across different combinations of superpixel scale and compactness parameters with 1% training ratio. Optimal performance is achieved at scale = 30 and compactness = 0.05.

Table 2.

Parameter sensitivity analysis on the WHU-Hi-LongKou dataset: performance metrics (OA, AA, in %) across scale and compactness configurations. The model maintains robust performance with OA consistently above 99.4%.

4.3.2. Component-Wise Analysis

We conduct component-wise ablation studies on the Houston2018 dataset to examine the contribution of each module in SSGTN (Table 3). Overall, the results indicate that the modules address different failure modes in low-label HSIC and thus provide complementary benefits. The Spectral Denoising Module (SDM) improves the reliability of region descriptors and affinity estimation by suppressing band redundancy and sensor noise prior to graph construction, which helps mitigate error propagation during subsequent message passing. The Spectral–Spatial Shift Module (SSSM) introduces an explicit yet parameter-free spectral–spatial interaction prior on the pixel grid before region aggregation, enhancing robustness to mixed pixels and local boundary perturbations. Building upon these strengthened low-level representations, the Spatial Transformer Branch captures long-range spatial context over the superpixel topology, whereas the Spectral Transformer Branch emphasizes non-local cross-band correlations that are not fully recovered by local propagation alone; their joint use therefore integrates spatial continuity with spectral correlation into a unified representation. Importantly, the additional overhead remains controlled because SSSM introduces no learnable parameters and attention operates on a compact superpixel graph rather than the full pixel lattice.

Table 3.

Comprehensive ablation study on the Houston2018 dataset evaluating individual contributions of Spectral Denoising Module (SDM), Spectral–Spatial Shift Module (SSSM), Spatial Transformer Branch (SpaT), and Spectral Transformer Branch (SpeT) (mean ± std over five seeds).

4.3.3. Training Ratio Analysis

To assess robustness under limited supervision, we vary the training sample ratio from 1% to 5% across all datasets (Table 4). The results highlight strong label efficiency: SSGTN benefits noticeably from small increases in supervision and exhibits diminishing returns as the annotation budget grows, which is consistent with the model’s ability to exploit structural priors and global context when labels are scarce. The improvement pattern also differs across datasets. For WHU-Hi-LongKou, the accuracy saturates rapidly due to clearer object extents and higher spatial resolution, suggesting that structural regularity and strong spatial cues allow effective learning with very few labels. In contrast, Indian Pines and Houston2018 require more supervision to stabilize class-balanced performance, which can be attributed to stronger spectral confusion, mixed pixels, and class imbalance that make minority categories harder to learn. Overall, this analysis indicates that SSGTN is particularly suitable for low-label settings, while further gains in highly imbalanced scenes are more likely to be constrained by data scarcity in rare classes rather than representation capacity alone.

Table 4.

OA, AA, and kappa (%) of SSGTN on three datasets under different training ratios. (mean ± std over five seeds).

4.3.4. Computational Complexity

To complement the performance-oriented ablations, we further report a per-image complexity comparison on the WHU-Hi-LongKou dataset in terms of FLOPs and model parameters (Table 5). A key observation is that the FLOPs are dominated more by the token/region granularity than by the parameter count. Patch-based 3D CNN/Transformer pipelines typically operate on dense spectral–spatial patches or long token sequences on the full pixel lattice, which leads to – G FLOPs per image. In contrast, superpixel-graph methods (GCN, CEGCN, and SSGTN) compress the image into a much smaller set of region nodes and perform message passing/attention on a sparse adjacency, substantially reducing computation while still leveraging contextual aggregation. Importantly, G-Mamba does not adopt superpixel segmentation and thus incurs high FLOPs despite being categorized as a graph/SSM hybrid, since its global modeling is still carried out at a much finer granularity. Meanwhile, the notably low FLOPs of MambaHSI are largely attributed to its tile-based processing strategy, which reduces the effective sequence length and computation per forward pass compared to patch-based tokenization used by several Transformer-style baselines. We note that peak GPU memory consumption is also strongly implementation-dependent (e.g., batch size, precision, and activation storage), and therefore we report FLOPs/parameters as hardware-agnostic indicators while providing qualitative discussion of memory trends through token/region granularity. Overall, SSGTN provides a favorable computation–capacity trade-off with a clear advantage in FLOPs, while its parameter size is comparatively larger and remains a noticeable drawback.

Table 5.

Per-image complexity comparison on the WHU-Hi-LongKou dataset. FLOPs are reported in G, and parameters are reported in MB.

4.4. Experimental Results

4.4.1. Comparative Performance Analysis

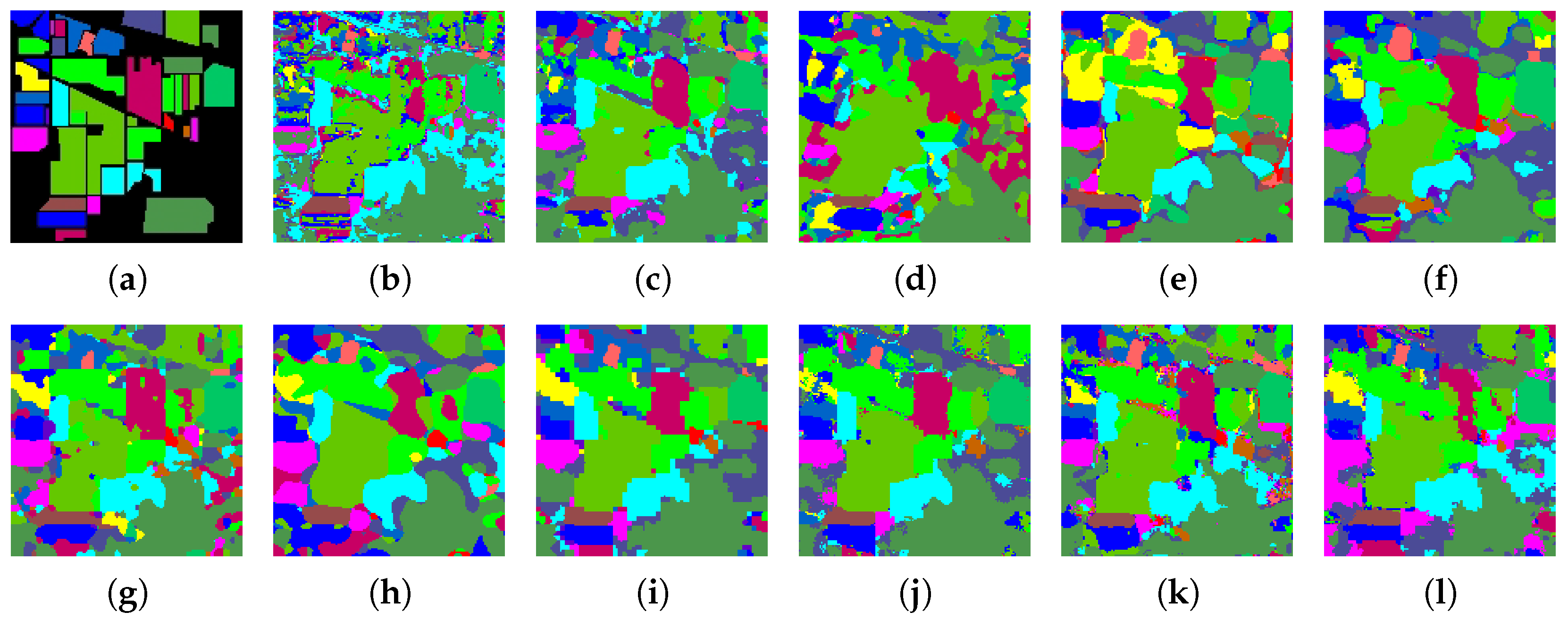

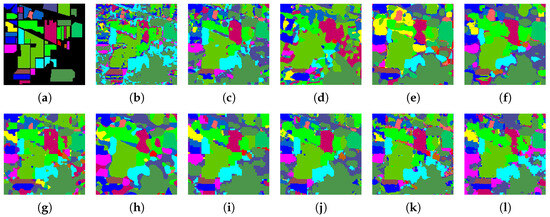

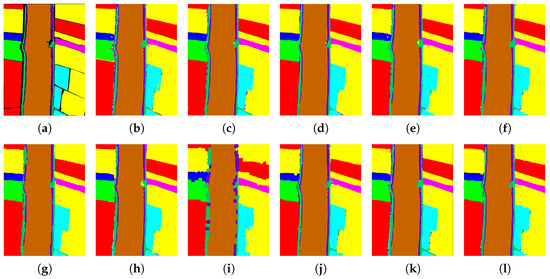

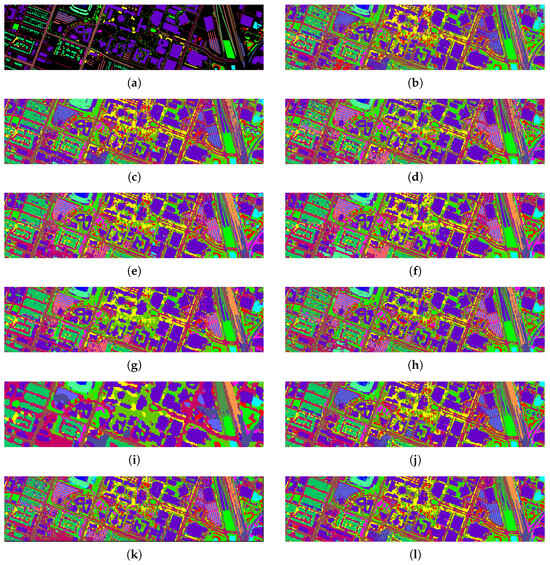

Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8 and Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 indicate that SSGTN provides consistent improvements across three representative benchmarks under the 1% per-class protocol. We additionally report a classical support vector machine (SVM) baseline as a non-deep-learning reference. Across all three datasets, SVM yields noticeably lower OA and compared with deep models, and its large variance on Indian Pines indicates limited robustness under scarce supervision and strong spectral confusion. With Indian Pines, the dominant challenge is the combination of coarse spatial resolution, strong spectral similarity among crop types, and extreme class imbalance. In this regime, methods that rely heavily on local neighborhoods tend to be more affected by mixed pixels and scarce supervision for minority categories. The region-level structural prior and global reasoning in SSGTN improve spatial consistency and overall robustness, while class-balanced performance remains constrained by the lack of samples in rare classes. In WHU-Hi-LongKou, the scene exhibits clearer object extents and higher spatial resolution, and superpixel regions align well with meaningful structures. Consequently, region-level graph modeling becomes highly effective and most competitive methods approach saturation, with SSGTN maintaining clean boundaries and fewer spurious fragments in the prediction maps. In Houston2018, the urban environment introduces high intra-class variability and pronounced imbalance. In this setting, combining graph-regularized spatial coherence with global contextual modeling is particularly beneficial for complex man-made structures, whereas residual errors are mainly concentrated in rare categories, suggesting that data imbalance is a primary bottleneck for further gains.

Table 6.

Results on the Indian Pines dataset with 1% training samples (mean ± std over five seeds).

Table 7.

Results on the WHU-Hi-LongKou dataset with 1% training samples (mean ± std over five seeds).

Table 8.

Results on the Houston2018 dataset with 1% training samples (mean ± std over five seeds).

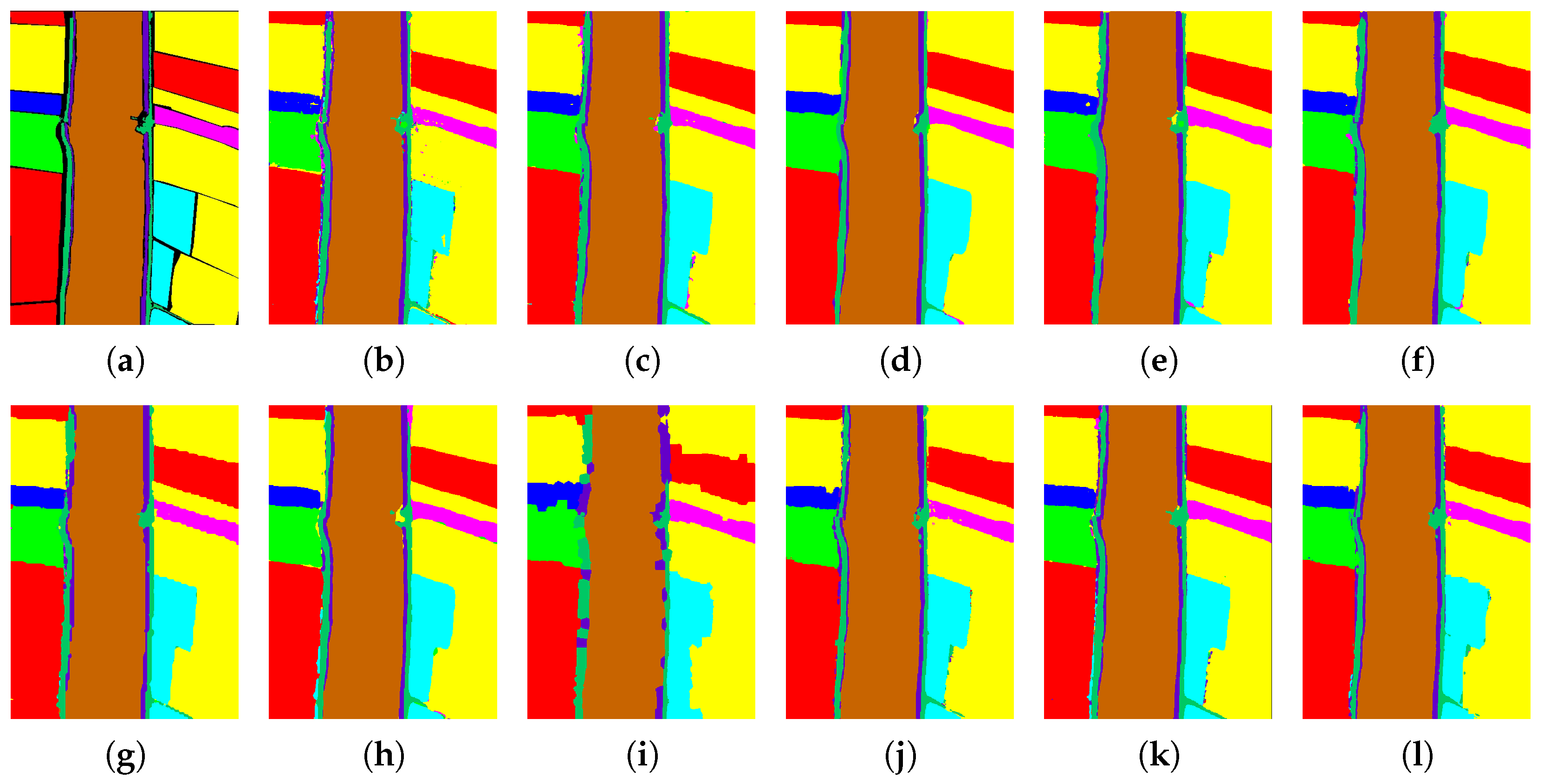

Figure 4.

Classification maps of different models on the Indian Pines dataset with 1% samples per class as the training set. (a) Ground truth; (b) CNN-2D; (c) SSRN; (d) HybridSN; (e) SSFTT; (f) MorphFormer; (g) MambaHSI; (h) MFormer; (i) GCN; (j) CEGCN; (k) Graph-Mamba; (l) SSGTN (ours).

Figure 5.

Classification maps of different models on the WHU-Hi-LongKou dataset with 1% samples per class as the training set. (a) Ground truth; (b) CNN-2D; (c) SSRN; (d) HybridSN; (e) SSFTT; (f) MorphFormer; (g) MambaHSI; (h) MFormer; (i) GCN; (j) CEGCN; (k) Graph-Mamba; (l) SSGTN (ours).

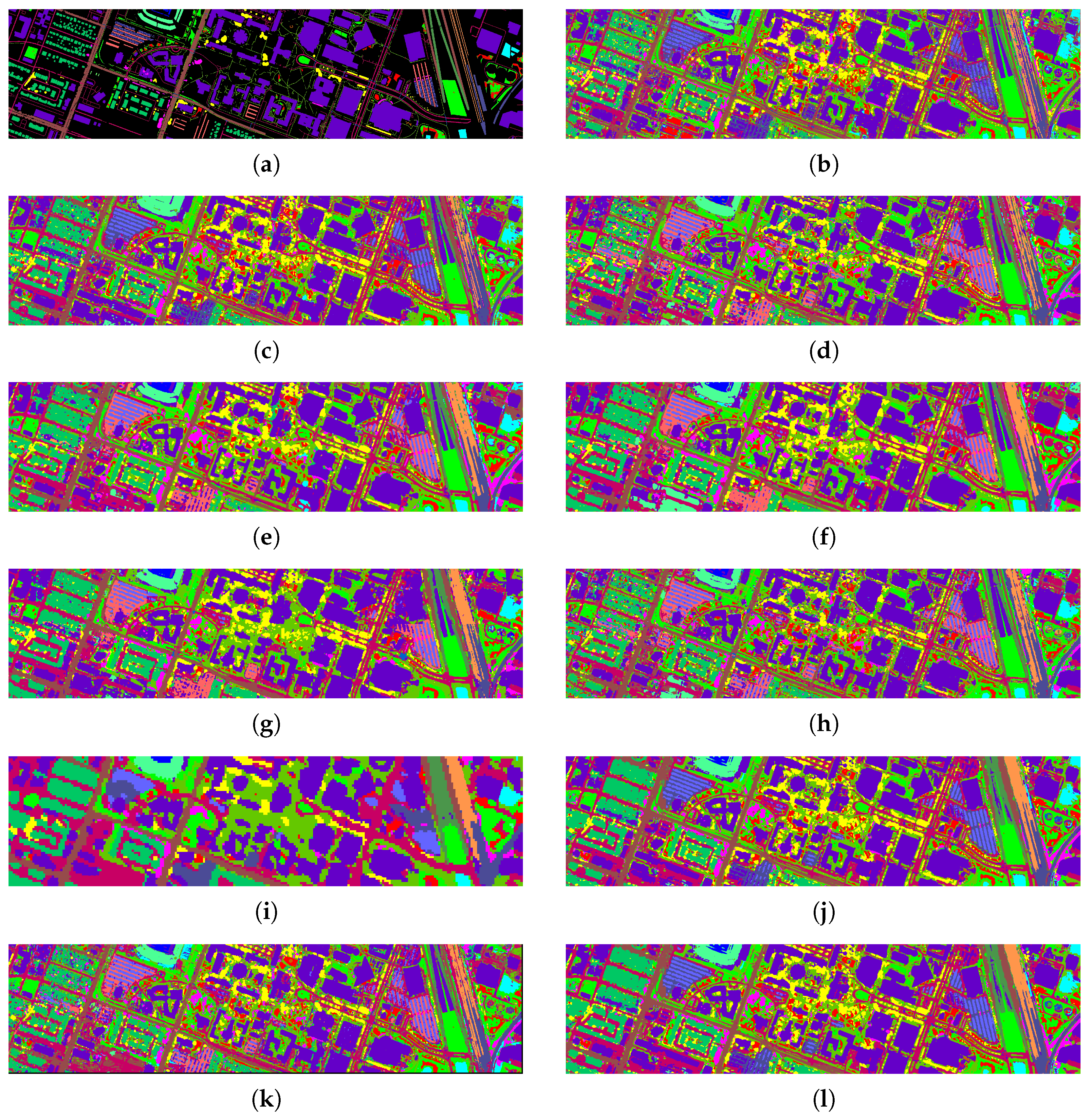

Figure 6.

Classification maps of different models on the Houston2018 dataset with 1% samples per class as the training set. (a) Ground truth; (b) CNN-2D; (c) SSRN; (d) HybridSN; (e) SSFTT; (f) MorphFormer; (g) MambaHSI; (h) MFormer; (i) GCN; (j) CEGCN; (k) Graph-Mamba; (l) SSGTN (ours).

4.4.2. Qualitative Results and Visual Analysis

Classification maps in Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 are examined from three complementary perspectives, i.e., intra-region homogeneity, boundary adherence, and robustness to sparse supervision. Compared with CNN-based baselines, which tend to produce fragmented predictions around mixed pixels, and purely global models, which may introduce scattered misclassifications when local structure is ambiguous, SSGTN yields spatially coherent regions while preserving class transitions at object boundaries. This behavior is consistent with the intended role of the superpixel graph in enforcing structural regularity and the Transformer branch in compensating for long-range contextual dependencies, thereby mitigating both salt-and-pepper noise and excessive over-smoothing.

On Indian Pines (Figure 4), where small agricultural parcels and spectrally similar crop types often induce local confusion, SSGTN reduces isolated mislabeled pixels and maintains more continuous field patterns, indicating improved handling of mixed pixels under scarce labels. On WHU-Hi-LongKou (Figure 5), the dominant challenge is aligning predictions with elongated field boundaries; SSGTN better follows these boundaries and suppresses cross-field label leakage, reflecting effective region-level regularization. On the urban Houston2018 scene (Figure 6), fine-grained man-made structures and strong material similarity can cause boundary blur or sporadic errors; SSGTN preserves sharper transitions between adjacent classes and produces cleaner structural layouts, suggesting that combining graph-based locality with attention-driven context is beneficial for discriminating spectrally close categories.

5. Discussion

The experimental results demonstrate that SSGTN effectively addresses key challenges in hyperspectral image classification under limited labeled data through its novel architectural design. The dual-branch framework successfully leverages complementary strengths: the graph-based branch preserves discriminative spectral patterns in homogeneous regions, while the Transformer branch captures long-range dependencies essential for complex landscapes.

However, SSGTN exhibits limitations in handling severely underrepresented classes, as evidenced by the poor performance on Class 12 in Houston2018. This limitation stems from graph sparsity in rare classes and attention bias toward dominant categories. Future work should explore topology-aware graph sampling and attention regularization to improve minority class representation.

Compared to CNN-based methods, SSGTN achieves superior spatial coherence through graph-structured regularization. Relative to pure GCN approaches, the Transformer branch mitigates oversmoothing in heterogeneous scenes. The computational complexity of joint graph-attention learning necessitates careful hardware considerations for large-scale deployments, though the sparse graph construction provides significant efficiency gains.

The consistent performance advantage across diverse datasets and low-label training regimes demonstrates that SSGTN is a robust and generalizable framework for hyperspectral image classification, particularly in practical scenarios where labeled data are limited and computational efficiency is critical.

6. Conclusions

This paper has presented the SSGTN, a novel dual-branch architecture that advances hyperspectral image classification under limited supervision. The proposed framework integrates four key innovations: an LDA-SLIC superpixel graph construction module that preserves discriminative spectral–spatial features, a spectral denoising module for noise suppression, a parameter-efficient Spectral–Spatial Shift Module for multi-dimensional feature interaction, and a dual-branch GCN-Transformer that jointly models local topology and global dependencies. Extensive experiments on three benchmark datasets demonstrate that SSGTN consistently outperforms state-of-the-art methods under limited supervision conditions while maintaining computational efficiency through sparse graph representations and optimized module design.

Future research will focus on enhancing SSGTN’s capability to handle severe class imbalance through advanced graph sampling strategies and attention regularization techniques. We will also explore self-supervised pretraining approaches to further improve sample efficiency and investigate adaptive graph construction mechanisms for better boundary preservation in heterogeneous landscapes. These developments aim to extend the framework’s applicability to more complex real-world scenarios while addressing current limitations in computational scalability and minority class representation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.S. and Z.L.; methodology, H.S.; investigation, H.S., Z.L., Y.M., G.Z. and X.D.; editing, H.S. and Z.L.; writing—review, H.S., Z.L., Y.M., G.Z. and X.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was jointly supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) under Grant 62403155; the Guangzhou Basic and Applied Basic Research Topics under Grant 2024A04J2081; the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Fund under Grant 2023A1515011850; the Guangzhou Science and Technology Planning Project under Grant 2024A03J0460; and the College Students’ Science and Technology Innovation Cultivation Project of Guangdong Province, China under Grant pdjh2024a293.

Data Availability Statement

The hyperspectral datasets used in this study are publicly available. The Indian Pines dataset is available at https://www.ehu.eus/ccwintco/index.php/Hyperspectral_Remote_Sensing_Scenes#Indian_Pines, accessed on 28 November 2025. The WHU-Hi-LongKou dataset is part of the WHU-Hi hyperspectral benchmark and is available at https://rsidea.whu.edu.cn/e-resource_WHUHi_sharing.htm, accessed on 28 November 2025. The Houston2018 dataset was released as part of the 2018 IEEE GRSS Data Fusion Contest, jointly provided by the National Center for Airborne Laser Mapping (NCALM) and the University of Houston; detailed information and access are available at https://machinelearning.ee.uh.edu/2018-ieee-grss-data-fusion-challenge-fusion-of-multispectral-lidar-and-hyperspectral-data/, accessed on 28 November 2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Mahlein, A.K. Plant disease detection by imaging sensors–parallels and specific demands for precision agriculture and plant phenotyping. Plant Dis. 2016, 100, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, K.; Ma, W.; Chen, L.; Wang, H.; Du, Q.; Du, P.; Yan, B.; Liu, R.; Li, H. Estimating the distribution trend of soil heavy metals in mining area from HyMap airborne hyperspectral imagery based on ensemble learning. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 401, 123288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Meer, F.D.; Van der Werff, H.M.; Van Ruitenbeek, F.J.; Hecker, C.A.; Bakker, W.H.; Noomen, M.F.; Van Der Meijde, M.; Carranza, E.J.M.; De Smeth, J.B.; Woldai, T. Multi- and hyperspectral geologic remote sensing: A review. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2012, 14, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, D. Design and Analysis of Spaceborne Hyperspectral Imaging System for Coastal Studies. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.L.; Esquerre, C.; Sun, D.W. Methods for performing dimensionality reduction in hyperspectral image classification. J. Near Infrared Spectrosc. 2018, 26, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; He, M.; Fowler, J.E.; Du, Q. Hyperspectral image classification based on spectra derivative features and locality preserving analysis. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE China Summit & International Conference on Signal and Information Processing (Chinasip), Xi’an, China, 9–13 July 2014; pp. 138–142. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, K.; Li, E.; Du, Q.; Du, P. Hyperspectral image classification using band selection and morphological profiles. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2013, 7, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, T.; Zhang, Z.; Crabbe, M.J.C. Few-Shot Hyperspectral Remote Sensing Image Classification via an Ensemble of Meta-Optimizers with Update Integration. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, P.D.; Mantripragada, K.; He, Y.; Qureshi, F.Z. Improving hyperspectral image segmentation by applying inverse noise weighting and outlier removal for optimal scale selection. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 171, 348–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Huang, Y.; Wei, L.; Zhang, F.; Li, H. Deep convolutional neural networks for hyperspectral image classification. J. Sens. 2015, 2015, 258619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Shen, Q. Spectral–spatial classification of hyperspectral imagery with 3D convolutional neural network. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.K.; Krishna, G.; Dubey, S.R.; Chaudhuri, B.B. HybridSN: Exploring 3-D–2-D CNN feature hierarchy for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2019, 17, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Chen, Y.; Lin, Z. Spatial-spectral transformer for hyperspectral image classification. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.; Han, Z.; Yao, J.; Gao, L.; Zhang, B.; Plaza, A.; Chanussot, J. SpectralFormer: Rethinking hyperspectral image classification with transformers. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 5518615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Tu, B.; Liu, B.; Li, J.; Plaza, A. 3DSS-Mamba: 3D-spectral-spatial mamba for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5534216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.; Gao, L.; Yao, J.; Zhang, B.; Plaza, A.; Chanussot, J. Graph convolutional networks for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 59, 5966–5978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; Gong, C.; Zhong, P.; Du, B.; Zhang, L.; Yang, J. Multiscale dynamic graph convolutional network for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 58, 3162–3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.Y.; Li, H.C.; Hu, W.S.; Pan, L.; Du, Q. Adaptive cross-attention-driven spatial–spectral graph convolutional network for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2021, 19, 6004705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.A.; Hy, T.S.; Dao, P.D. MOB-GCN: A Novel Multiscale Object-Based Graph Neural Network for Hyperspectral Image Classification. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.16289. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, M.; Butt, M.H.F.; Usama, M.; Mazzara, M.; Distefano, S.; Khan, A.M.; Hong, D. Hybrid State-Space and GRU-based Graph Tokenization Mamba for Hyperspectral Image Classification. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.06427. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Ye, Y.; Li, X.; Lau, R.Y.; Zhang, X.; Huang, X. Hyperspectral image classification with deep learning models. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2018, 56, 5408–5423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhatib, M.Q.; Al-Saad, M.; Aburaed, N.; Almansoori, S.; Zabalza, J.; Marshall, S.; Al-Ahmad, H. Tri-CNN: A three branch model for hyperspectral image classification. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Khan, A.M.; Mazzara, M.; Distefano, S.; Ali, M.; Sarfraz, M.S. A fast and compact 3-D CNN for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2020, 19, 5502205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.; Cao, G.; Li, X.; Fu, P. Hyperspectral image classification method based on 2D–3D CNN and multibranch feature fusion. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 5776–5788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, A.; Zhou, X.; Miao, F. Innovative hyperspectral image classification approach using optimized CNN and ELM. Electronics 2022, 11, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Han, R.; Song, M.; Liu, C.; Chang, C.I. Feedback attention-based dense CNN for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 5501916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, R.; Li, Z.; Liu, Q.; Ghamisi, P.; Bhattacharyya, S.S. Hyperspectral image classification with attention-aided CNNs. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 59, 2281–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakite, A.; Jiangsheng, G.; Xiaping, F. Hyperspectral image classification using 3D 2D CNN. IET Image Process. 2021, 15, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munishamaiaha, K.; Kannan, S.K.; Venkatesan, D.; Jasiński, M.; Novak, F.; Gono, R.; Leonowicz, Z. Hyperspectral image classification with deep CNN using an enhanced elephant herding optimization for updating hyper-parameters. Electronics 2023, 12, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, X.; Ye, Y.; Lau, R.Y.; Lu, S.; Li, X.; Huang, X. Synergistic 2D/3D convolutional neural network for hyperspectral image classification. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zhao, G.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, Z. Spectral–spatial feature tokenization transformer for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5522214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Cao, W.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, Y. Hyperspectral image transformer classification networks. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5528715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.K.; Deria, A.; Shah, C.; Haut, J.M.; Du, Q.; Plaza, A. Spectral–spatial morphological attention transformer for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5503615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, M.; Chang, S. Spatial and Spectral Structure-Aware Mamba Network for Hyperspectral Image Classification. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Lin, K.; Liu, H. HS-Mamba: Full-Field Interaction Multi-Groups Mamba for Hyperspectral Image Classification. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.15612. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, C.; Teng, X.; Chu, M.; Hao, Y.; Qin, S.; Li, X.; Yu, X. LDBMamba: Language-guided Dual-Branch Mamba for hyperspectral image domain generalization. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 280, 127620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jin, X.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Y.; Tu, L. EchoMamba: A new Mamba model for fast and efficient hyperspectral image classification. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0330678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Xuan, C.; Cheng, F.; Tang, Z.; Gao, X.; Song, Y. CenterMamba: Enhancing semantic representation with center-scan Mamba network for hyperspectral image classification. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 287, 127985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Luan, H.; Huang, K.; Sun, Y. Hyperspectral image classification using multi-scale lightweight transformer. Electronics 2024, 13, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, A.; Shang, Z.; Tian, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Tang, Y.Y. Spectral–spatial graph convolutional networks for semisupervised hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2018, 16, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, L.; Lu, X.; Li, X.; Zhu, X.X. Nonlocal graph convolutional networks for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 58, 8246–8257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Xiao, L.; Yang, J.; Wei, Z. CNN-enhanced graph convolutional network with pixel-and superpixel-level feature fusion for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 59, 8657–8671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Xu, Y. Pixel-level graph neural networks based on optimized feature representation for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 140830–140846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, R.; Zhu, K.; Chang, H.; Zhang, W.; Feng, J.; Xu, S. Hyperspectral image classification based on mixed similarity graph convolutional network and pixel refinement. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 170, 112657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.; Cao, J.; Huang, J.; Ju, H.; Liu, G.; Cao, H.; Ding, W. Global-local graph convolutional broad network for hyperspectral image classification. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 170, 112723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, D.; Zhi-li, Z.; Xiao-feng, Z.; Wei, C.; Fang, H.; Yao-ming, C.; Cai, W.W. Deep hybrid: Multi-graph neural network collaboration for hyperspectral image classification. Def. Technol. 2023, 23, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, S.; Xu, M.; Jia, X. Graph-in-graph convolutional network for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 35, 1157–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Debbagh, M.; Zhou, X.; Sun, S.; Huang, Y. Graph-Transformer with spatial-spectral features fusion for hyperspectral image classification. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 264, 125962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.A. The use of multiple measurements in taxonomic problems. Ann. Eugen. 1936, 7, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achanta, R.; Shaji, A.; Smith, K.; Lucchi, A.; Fua, P.; Süsstrunk, S. SLIC superpixels compared to state-of-the-art superpixel methods. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2012, 34, 2274–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.02907. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 600–610. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.