Highlights

What are the main findings?

- A spatial–temporal enhancement strategy for radar SLAM reduced Absolute Trajectory Error by up to 55.23% compared to baseline frameworks in Canopy-Occluded routes.

- Incorporating OpenStreetMap priors with adaptive constraint weighting achieved a minimum trajectory error of 1.83 m.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- Demonstrates that integrating millimeter-wave radar sensing with spatial–temporal optimization and open-source maps substantially improves positioning robustness in real-world signal-degraded environments.

Abstract

Accurate localization in canopy-occluded, GNSS-challenged environments is critical for autonomous robots and intelligent vehicles. This paper presents a coarse-to-fine trajectory estimation framework using millimeter-wave radar as the primary sensor, leveraging its foliage penetration and robustness to low visibility. The framework integrates short- and long-term temporal feature enhancement to improve descriptor distinctiveness and suppress false loop closures, together with adaptive OpenStreetMap-derived priors that provide complementary global corrections in scenarios with sparse revisits. All constraints are jointly optimized within an outlier-robust backend to ensure global trajectory consistency under severe GNSS signal degradation. Evaluations conducted on the MulRan dataset, the OORD forest canopy dataset, and real-world campus experiments with partial and dense canopy coverage demonstrate up to 55.23% reduction in Absolute Trajectory Error (ATE) and a minimum error of 1.83 m compared with baseline radar- and LiDAR-based SLAM systems. The results indicate that the integration of temporally enhanced radar features with adaptive map constraints substantially improves large-scale localization robustness.

1. Introduction

Reliable trajectory estimation is a cornerstone for autonomous driving and mobile robotic systems, particularly in environments where GNSS signals are unavailable or severely degraded. In vegetation-covered regions, dense urban areas and adverse weather conditions, GNSS-based localization can suffer from significant errors, directly impacting navigation safety and operational stability [1,2]. In contrast to consumer-grade navigation services such as Google Maps or Apple Maps—which combine inertial sensors with continuous GPS updates for map matching—our target scenarios feature persistent GNSS outages where such methods cannot maintain reliable positioning. Conventional complementary sensors, such as cameras and LiDAR, also experience performance degradation in such scenarios: cameras are sensitive to illumination changes and motion blur [3,4], while LiDAR performance may deteriorate in rain, snow, or fog and suffer from occlusions by tree trunks or other traffic participants [5,6].

Millimeter-wave radar, leveraging FMCW technology, achieves long-range detection and strong penetration under low visibility, remaining robust to both dynamic occlusions and adverse weather. However, radar sensing also faces inherent limitations: relatively low angular resolution, high measurement noise, and reduced geometric detail in representations. Radar Cross Section (RCS) intensity images appear as elliptical spots with varying brightness, which limits descriptor distinctiveness and can lead to perception aliasing—a phenomenon that exacerbates odometry drift over time.

Existing radar SLAM approaches have explored temporal feature stacking, density-based descriptors, scan-sequence matching, and map-constrained optimization, but their integration has often followed incremental extensions without addressing the compounded challenges of GNSS-degraded scenarios with sparse and unreliable loop closures. Our work departs from these patterns by focusing explicitly on improving global consistency when GNSS is absent, and when the environment’s topology limits revisits.

Loop closure detection is essential for imposing global constraints in SLAM systems, thereby mitigating cumulative drift and enhancing trajectory consistency [7], yet its efficacy depends on the accuracy and stability of environmental feature representation, and the structural properties of the traversed routes. In radar-based SLAM, the sparsity of loop closures or incorrect matches caused by perception aliasing can severely hinder long-term consistency.

To address these challenges, we propose a coarse-to-fine millimeter-wave radar state estimation framework that integrates both short- and long-term temporal enhancements with adaptive map-based global constraints. Spatial enhancement through coarse initialization using OpenStreetMap (OSM), where radar odometry trajectories are aligned to the prior map and constraint strength is adaptively modulated based on matching confidence. Furthermore, short-term feature aggregation constructs a Temporal Density Context (TDC) descriptor that improves stability and distinctiveness while long-term temporal validation rejects false loop matches, alleviating issues from perception aliasing. Crucially, when loop closures are sparse, our adaptive map constraints act as a primary global correction mechanism, ensuring consistency without continuous GNSS or frequent revisits. These components are jointly optimized within a unified back-end framework, providing globally consistent trajectories and high-fidelity radar maps, even in dynamically changing and sensing-degraded scenarios.

The contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- Propose short- and long-term temporal enhancement strategies for radar SLAM, including TDC-based descriptor stabilization in the short term, and long-term loop closure pruning to address perception aliasing.

- Introduce spatial enhancement via adaptive map constraints, integrating OSM priors with confidence-based weight adjustment for improved global consistency, especially under sparse loop-closure conditions in GNSS-denied environments.

- Develop a coarse-to-fine radar trajectory estimation framework that fuses public maps with temporally enhanced radar odometry, validated through extensive experiments in urban and campus environments under GNSS outages and varying levels of canopy occlusion.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related work on radar SLAM, place recognition, loop closure detection, and map-assisted optimization. Section 3 details the proposed framework, with Section 3.2.1 and Section 3.2.2 introducing short- and long-term temporal enhancement modules. Section 3.3 explains adaptive map integration, and Section 4 presents experiment setups and results, followed by discussion in Section 5. Section 6 concludes the paper and outlines future directions.

2. Related Works

This chapter aims to provide an overview of the latest research advances in radar SLAM and map-based localization, with a focus on classical frameworks and their limitations. The main research emphasis of this paper is to enhance radar sensing capability and global constraints provided by OpenStreetMap to achieve consistent state estimation in canopy-occluded environments. We begin by tracing the development history of radar SLAM, followed by a discussion of place recognition and loop closure detection related to millimeter-wave radar. Finally, we review map-based localization methods and their associated shortcomings.

2.1. Radar-Based Localization and Mapping

Recently, the high penetration capability and long detection range of millimeter-wave radar have drawn increasing attention in localization and mapping research. Compared to traditional 3D radar, spinning Frequency Modulated Continuous Wave (FMCW) radar offers higher azimuth resolution and consistent environmental representation, making it suitable for vehicle ego-motion estimationin vegetated or canopy-occluded conditions. Radar SLAM frameworks often adapt approaches from laser or visual SLAM; however, the inherent structural noise in millimeter-wave radar data necessitates a strong focus on noise reduction and stable feature association. Radar feature extraction methods can generally be categorized into learning-based and non-learning-based approaches.

Learning-based approaches leverage neural networks to enhance feature extraction capabilities, making significant advancements in areas such as feature denoising [8] and feature point extraction [9,10]. For instance, Lai et al. proposed CartoRadar [11], an RF-based 3D SLAM framework that rivals vision-based methods by leveraging deep models for radar signal processing. Sie et al. introduced Radarize [12], which enhances radar SLAM with generalizable Doppler-based odometry through end-to-end learning. These methods demonstrate strong performance and represent the latest advances in radar SLAM; however, they typically require substantial training data, specialized hardware optimization, and nontrivial deployment pipelines, which can pose challenges for rapid field adaptation in GNSS-degraded, foliage-dense scenarios. However, due to the sample requirements and deployment challenges associated with learning-based methods, non-learning-based approaches are often preferred. Non-learning-based methods focus on extracting scattering features related to object size and material from millimeter-wave radar data and can be divided into three main categories: handcrafted feature-based methods [6,13,14,15], signal processing-based methods [16,17,18], and phase correlation-based methods [19,20]. Phase correlation methods typically utilize Fourier–Mellin transform (FMT) to achieve robustness against large inter-frame rotations. Handcrafted feature methods involve using threshold techniques or visual descriptors for feature extraction, such as the classic CFAR and its derivative works like CFEAR. Signal processing methods directly analyze the echo signals received at each azimuth angle, extracting peak features while preserving weak continuous features [16].

Based on the work of Cen et al. [16,17], Burnett et al. developed the Yeti radar odometry to mitigate motion distortion and Doppler effects. This system combines millimeter-wave radar scan context to create, to the best of our knowledge, the first complete open-source radar SLAM framework [10]. Hong et al. proposed a method to reduce the impact of millimeter-wave radar noise on trajectory accuracy by using spot extraction combined with ANMS for front-end pose estimation, followed by PCA and M2DP for loop closure detection. They then integrated millimeter-wave radar frame constraints with loop closure constraints to construct a pose graph optimization framework for accurate trajectory generation [6]. ORORA, aiming to reduce the probability of mismatches, introduces GNC and A-COTE to decouple rotation and translation estimation, and builds a complete SLAM system by incorporating millimeter-wave radar scan context [21]. Addressing the relatively low frame rate of millimeter-wave radar, Zhuang et al. proposed 4D iRIOM, which combines IMU pre-integration to achieve radar pose graph optimization, thus obtaining accurate velocity and pose estimates [22].

Current radar SLAM research primarily focuses on feature extraction, with relatively less attention given to backend constraint construction and multi-source constraint integration with map priors. Due to the lower frame rate of radar compared to LiDAR, it is more prone to cumulative drift, especially in canopy-occluded environments where sparse features and signal attenuation occur, highlighting the need for further research on maintaining long-term consistency in radar SLAM systems.

2.2. Radar Loop Closure Detection

Loop closure detection is generally defined as a retrieval problem, which involves the abstraction of sensor measurements and the analysis of similarities, thereby effectively mitigating long-term drift accumulation in large-scale or foliage-occluded environments [23,24,25]. Depending on the sensors used, loop closure detection can be categorized into visual-based, LiDAR-based, and radar-based methods. Visual-based methods primarily aims to retrieve features from images captured by camera sensors and evaluate the similarity between historical image data and the current image [26]. Despite numerous visual methods being proposed, such as SIFT [27], frameSLAM [28], Gist [29], Mixvpr [30], and NetVLAD [31], these methods often suffer from limitations due to the sensitivity of cameras to lighting conditions, particularly under significant variations in illumination and viewpoint.

With the increasing use of LiDAR in autonomous driving and robotics, LiDAR-based loop closure methods has shown greater stability compared to visual-based methods due to its robustness against lighting changes and high-precision distance measurement. Recent advances in LiDAR-based loop closure detection methods include Scan Context [32], PointNetVLAD [33], Scan Context++ [34], CSSC [35], and FastLCD [36]. However, LiDAR’s performance can degrade under adverse weather conditions or in vegetated and canopy-occluded scenes, where the laser beams are severely attenuated or scattered, and dynamic obstacles can obstruct LiDAR’s view, presenting challenges for LiDAR-based loop closure detection methods.

Conversely, millimeter-wave radar demonstrates greater resilience to foliage and canopy occlusions and provides an extended sensing range, rendering it more suitable for loop closure detection beneath dense vegetation canopies or in other perception-degraded environments. Spinning FMCW radar generates polar images characterized by dense elliptical spots that depict the surrounding environment. Each azimuth may encompass multiple power returns, and the intensity of these spots is utilized to differentiate objects composed of various materials. Consequently, recent research has predominantly concentrated on loop closure detection utilizing spinning FMCW radar sensors. AutoPlace [37] has effectively utilized radial velocity and Radar Cross Section (RCS) measurements for millimeter-wave radar place recognition. Cheng et al. developed a two-stage millimeter-wave radar relocalization module that first removes dynamic targets from the scene and then performs coarse-to-fine processing [38]. Raplace [39] achieved rigidity transformation invariance by combining Radon transforms with frequency domain cross-correlation and adapted thresholds based on autocorrelation levels to find the cross-correlation result most similar to the autocorrelation score, demonstrating improved robustness in partially occluded or cluttered outdoor environments.

Although significant progress has been made in millimeter-wave radar loop closure detection, existing approaches often rely on single-frame data and overlook trajectory continuity, which is critical for maintaining localization stability under canopy-occluded conditions. To address this gap, we propose short-term and long-term temporal enhancements that leverage temporal information to improve the consistency and distinctiveness of radar feature representations.

2.3. Pose Graph Optimization with Prior Map Integration

Despite extensive efforts to reduce drift in front-end odometry, the problem of error accumulation persists without sufficient global constraints and becomes increasingly significant over time [40,41,42]. Therefore, contemporary large-scale SLAM systems often integrate loop closure detection [43,44] and GNSS [45,46,47] to ensure the long-term stability and reliability of global constraints. On the one hand, loop closures rely on revisited areas along the path, which does not guarantee the persistence of constraints. On the other hand, GNSS is often ineffective in dense urban or canopy-occluded environments, necessitating the use of additional data sources to constrain the trajectory.

Pose graph optimization is a widely used method for incorporating global constraints into SLAM frameworks. It constructs a graph structure where constraints and poses are represented as vertices and edges, respectively, enabling global pose optimization [48]. Compared to filtering methods such as EKF [49], and particle filters [50], optimization-based approaches are not limited by the Markov assumption. They can dynamically select and optimize multiple historical frames related to the current frame, improving trajectory consistency. Consequently, many SLAM algorithms use pose graph optimization for back-end trajectory refinement [45,48,51].

Pose graph construction typically relies on two types of constraints: prior constraints, which provide approximate initial poses but come with errors, and odometry-based constraints, which describe pose relationships between consecutive frames and also contain errors. Odometry errors accumulate progressively, making it challenging to maintain trajectory consistency [52]. To address this issue and enhance system stability, global constraints that remain unaffected by error accumulation can be introduced, such as loop closures [43,44], GNSS [45,46], and prior maps [53,54]. These constraints are integrated into the pose graph to improve the overall accuracy and reliability of localization.

SD-maps provide essential road network topology and geometric information, which are fundamental for navigation, especially when direct sensing is limited by foliage or canopy occlusion [55,56]. Examples of widely used SD-maps include OpenStreetMap and Google Street View. OpenStreetMap, for instance, can offer localization accuracy at approximately the ten-meter level with LiDAR, even in vegetated or canopy-occluded regions where GNSS degradation is prevalent [57]. In the field of autonomous driving localization using OpenStreetMap, probability-based and map-matching methods are commonly employed to determine the current pose. Probability-based methods typically involve extracting features and associating them with a map using either non-learning [57,58,59] or learning-based approaches [60] and then updating probability scores to derive localization results. For instance, Hong et al. developed a probabilistic model to match radar feature points with road network and semantic information in OpenStreetMap for large-scale localization. However, this approach heavily depends on the accuracy of OpenStreetMap data, which is influenced by the crowdsourced nature of the data and thus may not always be reliable. In contrast, map-matching algorithms directly map trajectory points onto OpenStreetMap, offering greater fault tolerance as they are less reliant on the correctness of the map data. Among map-matching techniques, the Hidden Markov Model (HMM) provides a robust framework by leveraging the temporal and spatial consistency of trajectories, resulting in improved alignment and reliability in dynamic environments [61].

In this paper, we use millimeter-wave odometry trajectories as input, apply HMM-based map-matching to associate the current trajectory with the map, and construct adaptive map factors based on the distances between point pairs. This approach limits the range of possible loops to maintain the efficiency of loop closure detection while providing continuous and stable global constraints for the system operating under canopy-occluded conditions.

3. Methods

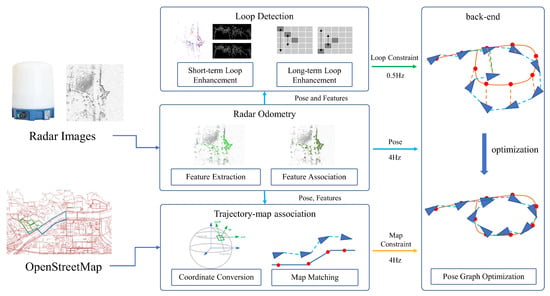

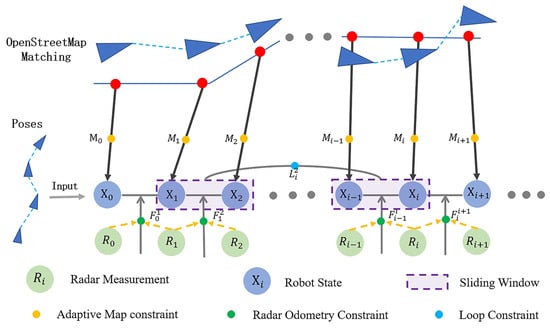

In this chapter, we present our millimeter-wave radar consistent state estimation framework designed for operation in dense foliage and canopy-occluded environments, as illustrated in Figure 1. The system comprises four main modules: radar odometry, trajectory-to-map matching, temporal-enhanced loop closure detection, and pose graph optimization with adaptive map factors. It takes spinning millimeter-wave radar polar images—often affected by high noise levels—and OpenStreetMap data as input, and outputs smooth, globally consistent trajectories and radar point cloud maps. The radar odometry module extracts stable features and estimates inter-frame poses from noisy radar polar data under severe occlusion. The trajectory-to-map matching module associates the current radar trajectory with the road network to provide coarse but stable global pose constraints, even where GNSS reception is degraded. The temporal-enhanced loop closure detection module supplies accurate constraints over extended time sequences, improving the robustness of long-term localization. Finally, the constraints generated by these three modules are integrated using pose graph optimization, ensuring both the smoothness and global consistency of the final trajectory and map outputs.

Figure 1.

An overview of our system, which takes millimeter-wave radar images and OpenStreetMap as inputs, achieves continuous and globally consistent state estimation through radar odometry, trajectory-to-map association, loop closure detection, and back-end optimization. The colored arrows represent different constraints fed into the pose graph: cyan for odometry poses, green for loop constraints, and yellow for map matching constraints.

3.1. Radar Odometry

Given the high noise levels in radar inputs—particularly under dense foliage and canopy occlusion, where speckle noise appears as dense elliptical spots with adjacent interference—we employ a two-step denoising prior to feature extraction. The Prewitt operator is applied in both radial and azimuth directions to suppress speckle and adjacent noise. From these denoised polar images, salient features with intensity peaks and spatial continuity are extracted using signal-processing techniques from our previous work [62]. Considering the relatively low output frequency and the Doppler effect of spinning radar sensors, motion and Doppler correction is performed for each pixel using the velocity estimated from the previous pose, as shown in (1).

where and represent the radial linear velocity (m/s) and angular velocity (rad/s), respectively; and are the original range (m) and azimuth angle (rad) measured by the FMCW radar; and correspond to the carrier frequency (Hz) and slope (Hz/s) of the modulated wave, is the frame time interval (s). The corrected features are then transformed to Cartesian coordinates:

We then use RANSAC and ICP to match noisy feature points between adjacent frames, thereby obtaining inter-frame pose estimates. The feature points extracted from the radar sensors, along with the estimated poses, are subsequently utilized for loop closure detection, map matching, and back-end processing.

3.2. Temporal Enhanced Loop Closure Detection

Radar loop closure detection leverages compact and efficient feature descriptors from radar sensors to represent the surrounding environment. However, for FMCW spinning radar, existing algorithms often overlook the variability in radar returns and their inherent temporal correlations, which can lead to decreased stability and accuracy—especially in dense foliage and canopy-occluded environments where features are frequently obscured or distorted. To address this limitation, we propose a temporal-enhanced loop closure detection algorithm. By jointly incorporating short-term dynamics and long-term temporal dependencies, our approach strengthens the robustness of radar feature representations, significantly reduces both false positives and missed detections, and supplies reliable global constraints for subsequent pose graph optimization.

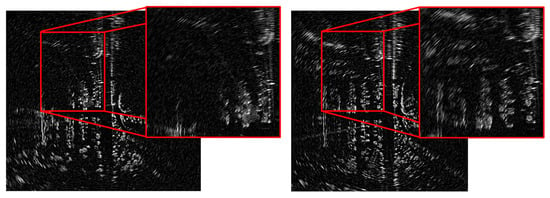

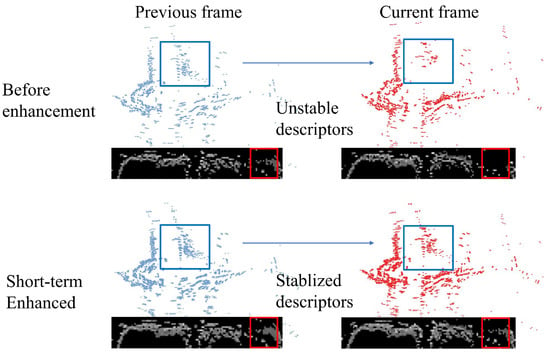

3.2.1. Short-Term Enhancement for Temporal Density Context Generation

Millimeter-wave radar sensors, due to its strong penetration capabilities and relatively low scan frame rate, often exhibits significant feature instability between adjacent frames. For example, a section of grass that is occluded by pedestrians in one frame, may become nearly fully visible in the next frame, as shown in Figure 2. This pronounced variability can lead to missed or false detection of loop closures in frames with such fluctuating features. To mitigate this problem, we propose leveraging the pose estimation results provided by radar odometry to overlay feature point clouds and construct a Temporal Density Context. This approach enhances the descriptors’ ability to characterize and stabilize the features.

Figure 2.

The difference between two adjacent raw radar data. The red boxes highlight areas with significant feature differences between frames.

We first use the pose estimation results from consecutive frames of the radar to precisely align the point cloud data of adjacent frames. This alignment helps to mitigate the effects of feature instability and constructs a local feature point cloud representing the current environmental segment, as illustrated in (3)

where and represent the aggregated point cloud for current frame t and the point cloud for single frame i. The transformation from frame i to frame t and the sliding window size are expressed as and n, respectively.

Due to the penetration capabilities of radar, multiple points may exist on the same scan line. Using radar scan context generated by occupancy grids is insufficient for capturing the complex structures and details in the environment. To address this, we have designed a short-term enhanced Temporal Density Context (TDC). This approach replaces the traditional occupancy grids with density information, providing a more continuous and detailed description of radar data. Figure 3 illustrates the process of generating Temporal Density Context (TDC). For the input point clouds from adjacent frames, we first calculate which density grid each point falls into, as shown in (4).

where represents the coordinates of the central point of the local feature point cloud, which is set to . i and j indicate the index of ring and sector of the bin. Therefore, the maximum radar detection range can be expressed as

where and represent the distance across a single ring and the number of rings, respectively. The azimuth angle covered by each bin, , can be expressed as

where denotes the number of sectors. For each bin, we encode the density of points within the sector and normalize this encoding using the radar’s distance resolution as a weight. This effectively abstracts the environment, as shown in (7)–(9).

where and represent the width of the radar ring and the distance resolution, respectively, while indicates the maximum number of feature points that a single ring can accommodate. represents the environmental weight, which can be increased or decreased depending on whether the environment is sparse or dense. denotes the count of points in each bin, is the final density weight of each bin, and I is the resulting Temporal Density Context (TDC). Finally, we enhance the efficiency of the corresponding search by computing the row average of the density matrix to obtain the ring key.

Figure 3.

The process of generating a temporal density context and the corresponding ringkey based on short-term enhancement. Point clouds of different colors correspond to distinct radar frames, while the yellow and green regions represent the partitioning based on azimuth and range, respectively.

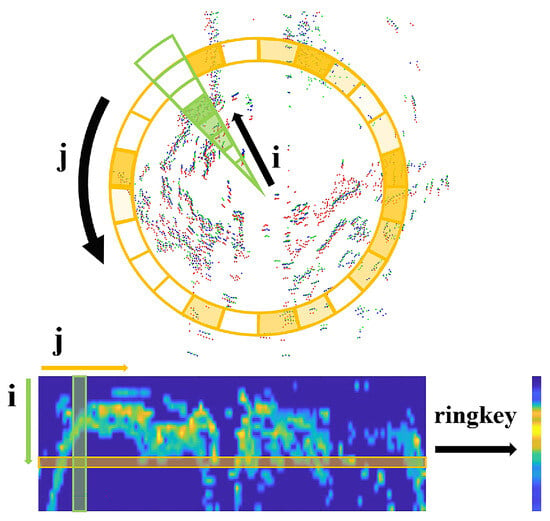

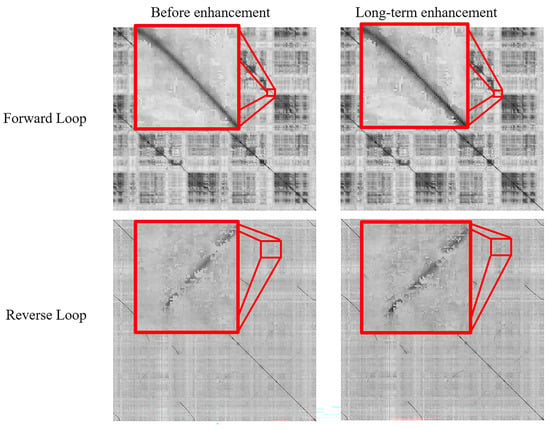

3.2.2. Long-Term Enhancement for Loop Outlier Removal

Given that the measurements from spinning radar sensors demonstrate temporal continuity, it follows that loop closures should similarly embody this attribute. In other words, isolated loop closures are often likely to be incorrect. For example, if the current frame j is related to a historical frame i, then adjacent frames to frame j should be related to adjacent frames to frame i. This can be observed as obvious similarity along the diagonal or anti-diagonal directions in the similarity matrix, as illustrated in Figure 4. Based on this observation, we propose using long-term feature enhancement to further filter the candidate loop closures.

Figure 4.

The principle of loop outlier removal based on long-term enhancement. The blue and orange gradient regions correspond to the historical (near frame i) and current (near frame j) sequences, respectively. The time axis progresses from left to right, with darker shades signifying closer temporal proximity and higher similarity.

After generating the Temporal Density Context (TDC) with short-term loop enhancement, we first use the global pose provided by the map-matching algorithm to select historical frames that are spatially close to the current pose as candidates for loop detection. This approach helps avoid the problem of increasing computational overhead associated with a growing number of historical frames. Subsequently, we filter the candidate frames by comparing the cosine similarity between the Temporal Density Context (TDC) of the current frame and that of the candidate frames, as in

where and represent the Temporal Density Context (TDC) descriptors for the candidate frame and the current frame, respectively, while and denote the column vectors at the same index. If the computed similarity is above a predetermined threshold, the candidate frame is retained. Specifically, the similarity threshold is estimated from validation sequences extracted from a dataset that contain at least one true loop closure. For each minimal sequence segment, we evaluate the Precision–Recall trade-off by sweeping threshold values, selecting the threshold that maximizes recall while keeping false positives low. This procedure ensures the selected value is grounded in representative data and tuned for diverse urban and canopy-covered scenarios, rather than being arbitrarily chosen. After processing all candidate frames, the k most similar candidates are selected from those retained for further loop outlier removal based on long-term enhancement.

For each of the k selected historical frames, a sliding window of length n is employed. We first compute the cosine similarity between the n frames preceding the selected frame and the n frames preceding the current frame, resulting in a forward similarity sequence. Similarly, we calculate the cosine similarity between the n frames following the selected frame and the n frames preceding the current frame, resulting in a backward similarity sequence. The difference between these two similarity sequences is then computed to form a difference sequence. Finally, a Gaussian kernel is applied to this difference sequence for weighted summation, yielding the final Symmetric Similarity Divergence (SSD). The Gaussian kernel is normalized using the Gaussian function .

where k denotes the offset from the current frame, and n represents the size of the sliding window.

where and represent the cosine similarity of the forward and reverse similarity sequences, respectively. The Symmetric Similarity Divergence (SSD) quantifies the deviation in similarity, where a higher SSD indicates a greater likelihood of a true loop closure, either forward or backward, while a lower SSD suggests a potential false detection. Finally, based on the calculated SSD, the frame with the maximum divergence is selected as the final candidate, and those with lower similarity scores are filtered out using a threshold to further reduce the loop closure false detection rate.

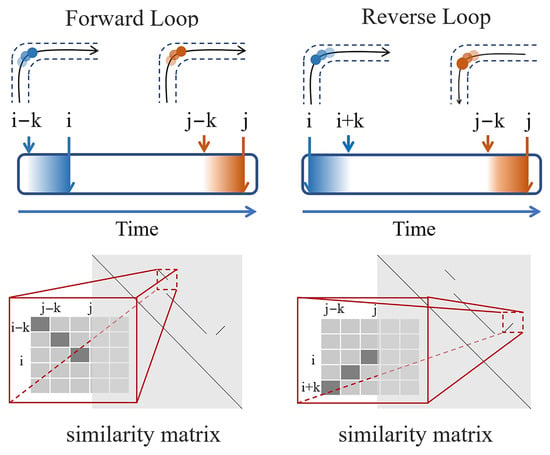

3.3. Pose Graph Optimization with Adaptive Map Factors

Loop constraints are limited by the number of revisited areas along the trajectory, making it challenging to continuously correct accumulated errors caused by fluctuated radar features. Road network from OpenStreetMap, being easily accessible and structurally simple, can readily provide coarse but global pose references for the system. Consequently, we propose an adaptive map constraint approach (see Figure 5). By regarding the state estimation problem as a maximum a posteriori (MAP) problem, we define three types of factors to optimize the state X: odometry factors, loop factors, and adaptive map factors, as illustrated in (14).

where represents the robot’s states. The odometry factor that provides the local pose relationship between frame i and frame is denoted as . The loop factor that describes the long-term pose relationship between frame i and frame j is denoted as . The adaptive map factor that provides the global constraint for frame i is denoted as . All residuals are weighted by their respective information matrices.

Figure 5.

The structure of the pose graph optimization with adaptive map factors. The blue and green circles represent robot states and radar measurements, respectively. Colored dots indicate specific constraints added to the graph: yellow for map matching, green for odometry, and cyan for loop closures.

3.3.1. Adaptive Map Factors

OpenStreetMap data is often readily available in urban road scenarios. These maps provide comprehensive road structure information and topological relationships, offering stable and reliable geometric constraints that serve as effective coarse pose priors.

Initially, we manually determine the starting point and heading on the OpenStreetMap, and construct a coarse mapping between local and global coordinates based on the WGS84 ellipsoid. Next, we convert the optimized trajectory within the time window into global coordinates using pose transformations. A Hidden Markov Model-based map matching algorithm [61] is then employed to establish the association between the local trajectory and the map. Finally, the trajectory is transformed back into local coordinates to build the pose constraints.

where and represent the pose of the frame i provided by the odometry in the local coordinate system and its corresponding position in the global coordinate system, i.e., LLA expressed as (16), respectively. and are the translation offset and the rotation offset between the local coordinate and ENU coordinate, i.e., east–north–up. denotes the transformation from the world coordinate system to the local coordinate system. Since is only related to the ellipsoid surface and the projection reference line, we can determine the offset between the reference point and the odometry origin in global coordinate by manually establishing and . The offset is then given by (17).

Thus, the world coordinate mapping of each subsequent odometry pose can be obtained as follows:

The current and historical odometry poses in world coordinates are fed into the map matching module to obtain the matched poses.

where represents the map matching function, denotes the number of historical frames involved in the matching, and represents the input from the OpenStreetMap. The results are then transformed into the local coordinate system for residual computation and factor construction.

The error function is represented in (21).

where and represent the pose of frame i in the local coordinate system and its corresponding map-matched pose, respectively, and ⊖ denotes the pose difference operator in SE(2). The residual function is then expressed in (22).

As a convention, we use the information matrix, which is the inverse of the covariance matrix, to represent the level of observation errors [21,63,64]. Given the limited accuracy of OpenStreetMap and errors from map-matching, communication delays, and initial point selection, we establish a constant error model based on prior knowledge. Translation errors are estimated using the distance between the current pose and its matched point, as well as the distance to the line l formed by two nearest historical matched points. Rotational errors are based on the orientation difference between the current and matched poses. This enables adaptive error estimation. In practice, the map-factor weight (information matrix ) is computed from the estimated planar error and heading error of matched map points. These indicators are derived using Equations (23) and (24), and their inverse-squared values scale the corresponding entries in . This formulation adaptively attenuates the influence of uncertain matches while retaining strong constraints for high-confidence associations. The thresholds used in error evaluation were tuned on validation routes to maintain consistent performance across different mapping qualities, providing sensitivity resilience against variations in OSM accuracy.

where denote the line segment formed by the poses of the frame i and frame in the local coordinate system. The function calculates the distance from a point to a line, and represents the indicator for translation error.

The rotation error indicator is given by (24).

where denotes the function for computing the angle between two lines, and represents the indicator for rotation error. Considering that the OpenStreetMap data is in 2D, only elements related to the local coordinates and yaw angle are computed in , with all other elements filled with zeros. Therefore, the adaptive map factor information matrix is given by (25).

where represents the prior accuracy information for the OpenStreetMap.

Based on the distances and orientation between trajectory points and matched points, we provide a method to evaluate the planar and heading errors of the matching points. This allows for an adaptive assessment of the confidence in map constraints, thereby mitigating the impact of false matches on the pose graph.

3.3.2. Loop Closure Factors

Loop closure factors are used to provide long-term pose constraints between non-consecutive frames i and j when the system revisits a previously mapped area. In radar SLAM, loop detection is inherently more challenging than in LiDAR or visual SLAM due to speckle noise, lower spatial resolution, and the dependency of scattering patterns on environmental conditions. To ensure robust factor construction, we adopt a two-stage process: loop-candidate generation followed by geometric verification.

Each incoming radar frame is first processed by our loop closure module (Section 3.2.1), producing a descriptor vector from the feature points. We then compare this descriptor to a database of previous frames using cosine similarity:

where and denote the descriptor vectors of frames i and j, respectively. Frames are considered loop candidates when exceeds the similarity threshold (empirically determined from validation sequences).

To avoid false positives caused by similar scattering patterns in different locations, loop candidates are further verified through scan alignment. Instead of using a phase-correlation method, we obtain an initial relative orientation from descriptor matching, then perform feature-based point correspondence extraction in Cartesian-transformed radar data.

A robust RANSAC procedure is employed to estimate a coarse rigid-body transform while eliminating outlier correspondences. This coarse transform is subsequently refined using Iterative Closest Point (ICP) registration, yielding the accurate relative pose . The alignment score is evaluated from:

where is the RMS alignment error. Loop candidates are accepted when , with tuned for balanced recall and precision across varied radar-noise conditions. For each accepted loop , the residual is computed as:

where ⊖ represents the pose difference operator in . The corresponding residual function is:

is the information matrix derived from the covariance of the scan-matching process, with diagonal entries inversely proportional to the estimated translation and rotation uncertainties. Similar to the adaptive map factor design in Section 3.3.1, the loop closure factor information matrix encodes our confidence in the relative pose constraint.

Translation uncertainty is quantified using the RMS error obtained during ICP refinement, while rotation uncertainty is indicated by the normalized descriptor similarity score . Specifically, we define:

where and are small positive constants representing the prior translation and rotation accuracy bounds, respectively. The first two entries correspond to the components in the local coordinate system, and the last non-zero entry corresponds to the yaw angle component. This design adaptively increases the loop closure weight for precise alignments (low ) and strong descriptor matches (high ), while attenuating the influence of uncertain closures.

High-confidence matches yield large values to enforce strong constraints, while uncertain matches are down-weighted to avoid distorting the graph. Unlike the odometry factor , which connects temporally adjacent frames and accumulates drift over long trajectories, leverages re-observed locations to correct accumulated errors.

Given our focus on canopy-occluded and GNSS-degraded environments, the loop closure factor is critical to achieving consistent localization when the adaptive map factors are temporarily weakened or unavailable.

4. Results

In this section, we validate the performance of our proposed method through both qualitative and quantitative experiments. The evaluation includes comparisons of trajectory accuracy and a comprehensive ablation study, covering GNSS-challenged scenarios such as canopy-occluded urban neighborhoods and campus environments. We first describe our experiment setup, including platform, datasets, and comparative frameworks in Section 4.1, followed by qualitative and quantitative comparisons of trajectories with existing SLAM systems based on millimeter-wave radar and LiDAR in Section 4.2. This assessment aims to evaluate the effectiveness of our system in delivering accurate and consistent state estimation under partial and dense vegetation coverage. In Section 4.4, we conduct ablation studies on the three proposed optimizations to assess their impact on the system and analyze the underlying reasons for their effects.

4.1. Experimental Setup

To evaluate the accuracy and consistency of the proposed system under various environmental conditions, we selected three scenarios from the MulRan dataset. Additionally, we conducted real-world experiments on a campus to further evaluate the effectiveness of our framework. All experiments were conducted on an Intel i7-12700H laptop running Ubuntu 20.04 with 32 GB of RAM. Our system, implemented in C++, utilizes GTSAM (v4.0.3) [65] and iSAM2 (https://borglab.github.io/gtsam/isam2/, accessed on 14 November 2025) [66] for pose graph optimization.

To quantify the accuracy of our system, we employed the established approach of aligning the trajectories of all methods with the ground truth and assessing them using Absolute Trajectory Error (ATE) [67]. The methods included in our comparison are SC-LeGO-LOAM [68], Yeti [14], radarSLAM [6], SC-ORORA [69], and LSRL [59]. Additionally, the assessment of OSM road networks against ground truth data has been conducted using the transverse Mercator projection. The experiments rely on three major datasets or collection platforms: the MulRan dataset [70], our real-world radar-based campus collection platform, and the OORD dataset [71] for canopy suitability testing.

Given the focus of our study on GNSS-challenged urban environments with partial and dense canopy obstruction, we selected three representative canopy-influenced scenarios from the MulRan dataset for our experiments: DCC, KAIST, and Riverside. These routes traverse neighborhoods, campuses, and riverside areas with varying levels of vegetation coverage, where tree canopies and roadside foliage periodically block or attenuate satellite signals. Such conditions not only degrade GNSS performance but also pose challenges for radar, LiDAR, and vision-based localization, making them ideal for evaluating the effectiveness of loop closure mechanisms and integration of map constraints under canopy-occluded conditions. MulRan dataset: Data were acquired using a ground vehicle equipped with a horizontally mounted 3D LiDAR (OS1-64, Ouster, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) and a horizontal millimeter-wave radar (CIR204-H, Navtech Radar Ltd., Ardington, UK), offering and resolution, a 360° field of view, and a detection range up to at . OORD dataset: To evaluate the system’s applicability in dense forest canopy environments, we employed the twolochs sequence from the oord dataset. This route includes mixed terrain such as tree-covered tarmac, gravel mountain tracks, and lochside roads, providing diverse surface conditions and canopy densities. For our experiments, we selected an approximately section with continuous and dense canopy coverage to simulate persistent GNSS signal attenuation. This subset was used to assess the localization performance and robustness of the proposed method under sustained forest canopy obstruction.

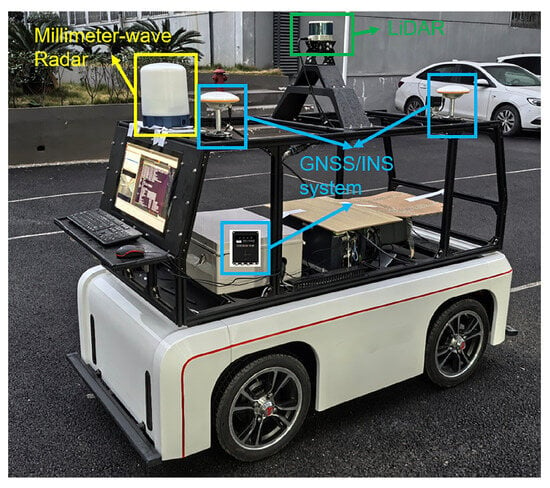

Real-world collection platform: Hardware includes an integrated navigation device (CGI430, CHC Navigation, Shanghai, China), a computational unit (Orin, NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with RAM, and a horizontally mounted mm-wave radar (RAS-3, Navtech Radar Ltd., Ardington, UK) with range resolution, angular resolution, maximum detection range, and scan frequency, which is illustrated in Figure 6. Multimodal spatiotemporal synchronization was achieved using engineering drawing-based spatial calibration and GPS+PPS hardware clock synchronization to ensure data validity. Ground-truth trajectories were obtained via GNSS/INS integrated navigation post-processing in unobstructed or weakly occluded zones, and through matching with high-definition maps in densely occluded or GNSS-degraded zones.

Figure 6.

Our platform for real-world experiments.

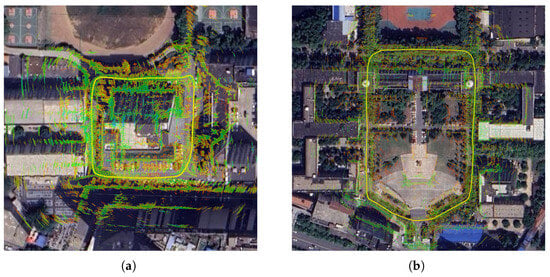

During the data acquisition process, the platform moved at an average speed of approximately 1.5 m per second. We selected two distinct scenarios for data collection on campus that offer different types and densities of canopy obstruction. The first sequence is a 220-m-long route navigating around the Starlake building, which involves sparse occlusions caused by roadside trees. The second sequence is a 430-m-long route traversing Youyi Square, containing alternating regions of dense canopy cover and open corridors with sparse vegetation, which cause varying levels of GNSS signal obstruction. Such canopy occlusion characteristics make this scenario particularly suitable for evaluating positioning performance under forest-like conditions. The ground truth trajectories were obtained through tightly coupled GNSS/INS integration, further refined via alignment with a high-definition map to compensate for incomplete RTK availability under dense canopy conditions (see Figure 7a,b).

Figure 7.

Real-world GNSS-challenged scenarios used for evaluating spatial-temporal enhancements on radar SLAM system. The small triangles and associated images indicate the viewing direction and the corresponding real-world scenes, respectively, illustrating the level of canopy occlusion. (a) The Starlake building (sparse canopy cover). (b) The Youyi Square (dense and sparse canopy cover).

4.2. Trajectory Evaluation

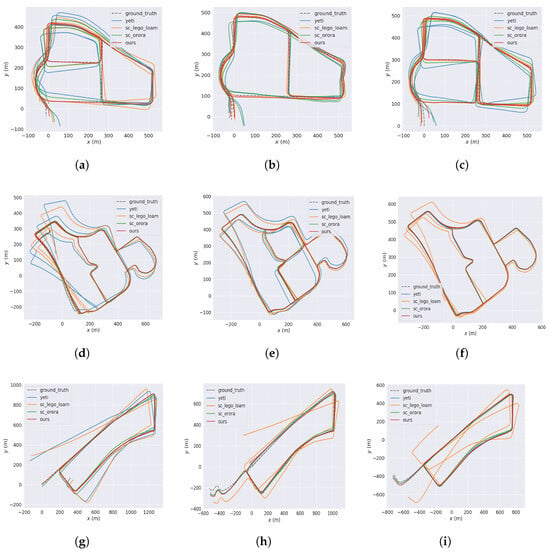

We first conducted a qualitative analysis of our system’s trajectory consistency by comparing the trajectories generated by our system with those produced by current leading LiDAR and millimeter-wave radar algorithms that incorporate loop closure, as well as the road network from the OpenStreetMap.

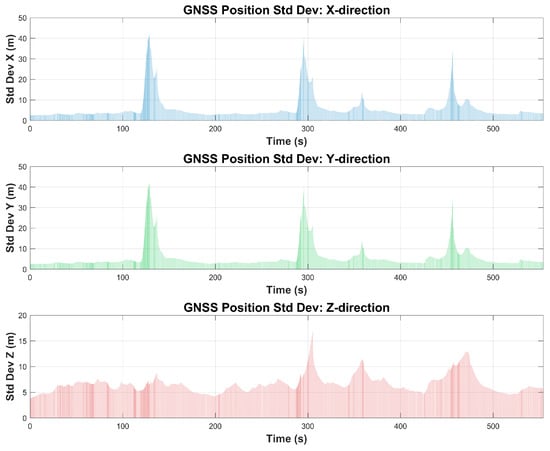

Figure 8 illustrates the geometric consistency between our trajectory and the satellite map within the neighborhood containing dense canopy-occlusion. To highlight the challenges in this environment, a GNSS covariance bar chart for the DCC01 sequence is provided in Figure 9, showing the variation of GNSS position standard deviation (X, Y, Z) over time and indicating periods of degraded precision. Finally, Figure 10 compares our trajectory with those of other methods, using pure GNSS positioning results as a reference.

Figure 8.

Visualization of the DCC01 sequence overlaid on a satellite map background. The yellow line represents the vehicle trajectory obtained by our method, while the colored points denote the mmWave feature point cloud. Point colors correspond to echo intensity, with warmer colors (towards red) indicating stronger returns and cooler colors indicating weaker returns.

Figure 9.

GNSS position standard deviation in X, Y, and Z directions over time for the DCC01 sequence. Periods of increased variance correspond to degraded GNSS precision.

Figure 10.

Trajectories on Mulran Dataset generated from methods including ground truth, Yeti, sc-lego-loam, sc-orora and our method for qualitative evaluation. The comparisons are performed on sequences: (a) DCC01, (b) DCC02, (c) DCC03, (d) KAIST01, (e) KAIST02, (f) KAIST03, (g) Riverside01, (h) Riverside02, (i) Riverside03.

To quantify the overall trajectory consistency performance of our proposed system, we calculated the Absolute Trajectory Error (ATE) by comparing our system-generated trajectories with the ground truth provided by the MulRan dataset and compared the results with other algorithms. Table 1 presents the ATE results for six different SLAM frameworks (SC-LEGO-LOAM, Yeti, SC-ORORA, radarSLAM, LSRL and ours) on the MulRan dataset. The ATE value represents the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of the positional difference between the algorithm’s trajectory and the ground truth, given temporal alignment. Lower values indicate better algorithm performance.

Table 1.

Absolute trajectory error (ATE) of different systems on the MulRan Dataset. All values are root mean square error (RMSE) in meters (m). The symbols “-” and “NA” denote cases where data was not provided in the original paper and where the system failed to complete the sequence, respectively. In the latter case, this indicates that the error exceeded 100 m. Bold values indicate the best accuracy. Pure GNSS errors are shown in italics to illustrate signal fluctuations in these scenarios, noting that neither the proposed method nor the comparison methods utilize GNSS as an input.

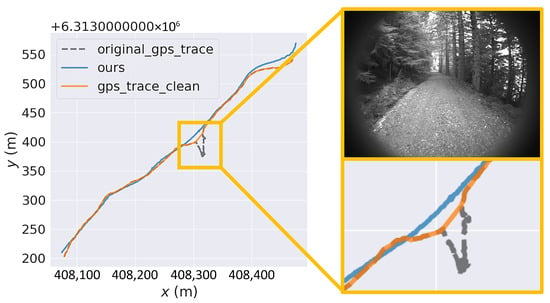

In the Twolochs forest region, characterized by dense canopy occlusion, irregular terrain, and the absence of distinct road geometry, GNSS signals suffer severe degradation, leading to pronounced trajectory drifting in raw GNSS data. In contrast, as illustrated in Figure 11, our method generates a smooth and stable trajectory estimate, achieving an Absolute Trajectory Error of 6.75 m relative to the reference path. These results demonstrate the applicability of the proposed framework to unstructured and topologically ambiguous environments, where conventional map-matching and GNSS-based solutions typically fail.

Figure 11.

Trajectory comparison under dense forest canopy in the Twolochs region (OORD dataset), including our method (blue solid line), GNSS data with outlier removal (orange solid line), and raw GNSS data (dashed line).

4.3. Real World Experiments

In our real-world experiments, we conducted both qualitative and quantitative evaluations. For the qualitative evaluation, we overlaid the estimated trajectories and radar-derived feature points onto satellite imagery, enabling direct visual inspection of their spatial alignment with the road network and the surrounding environment, which is shown in Figure 12. This approach verifies the consistency between the reconstructed trajectories, the radar point features, and the underlying map. For the quantitative evaluation, we computed the Absolute Trajectory Error (ATE) against ground truth to measure positioning accuracy. As shown in Table 2, our framework achieved an ATE of 0.55 m in the Starlake building sequence with sparse canopy occlusion, and 2.08 m in the Youyi Square loop containing a mix of dense and sparse canopy segments.

Figure 12.

The trajectory of our system in two scenes in our real world experiments. The yellow line represents the estimated trajectory. The mmWave feature points are colored by echo intensity, with warmer colors (red) indicating stronger returns. (a) The Starlake building. (b) The Youyi Square.

Table 2.

Absolute trajectory error (ATE) of our system on real world dataset. All values are given in meters (m).

4.4. Ablation and Real-Time Performance Analysis

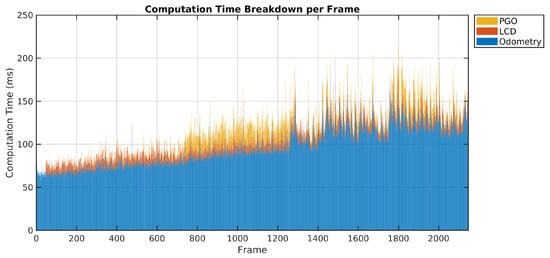

In addition to accuracy evaluation, we also analyze the runtime performance of the proposed system to verify its suitability for real-time operation. The major processing modules include millimeter-wave radar odometry, loop closure detection, and back-end pose graph optimization. The map-matching module is executed asynchronously at a low frequency and does not require real-time processing, hence it is excluded from this analysis. Given the rotational millimeter-wave radar operates at 4 Hz, a per-frame computation time below 250 ms satisfies the real-time criterion.

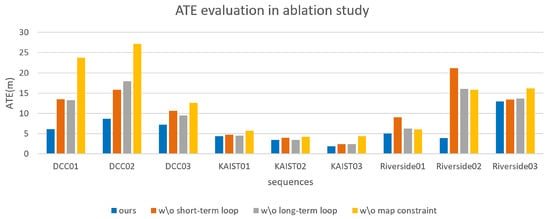

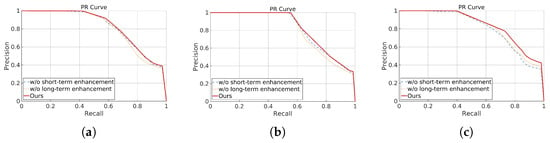

We introduced short-term and long-term loop closure enhancements along with adaptive map constraints to develop our coarse-to-fine algorithm for consistent state estimation. To validate the effectiveness of these improvements, we conducted comprehensive ablation experiments. Figure 13 displays the Absolute Trajectory Error (ATE) results after each component was removed, with qualitative and quantitative differences summarized in the following subsections. We also utilize Precision-Recall (PR)-curve to represent the contribution of each module, which in shown in Figure 14.

Figure 13.

The ATE results for evaluating the contribution of our proposed enhancement on the global accuracy.

Figure 14.

Precision-Recall evaluation for three scenes in the ablation study. Loop detection accuracy decreases when short-term and long-term enhancements are removed. (a) Precision–Recall Analysis for DCC01. (b) Precision–Recall Analysis for KAIST01. (c) Precision–Recall Analysis for Riverside01.

Figure 15 shows the stacked per-frame computation time during processing. After an initial fluctuation stage, the odometry module stabilizes at approximately 110 ms per frame. The back-end optimization time begins to increase slightly after around 800 frames, but the overall average per-frame processing time converges to about 130 ms. This corresponds to an effective processing frequency exceeding 4 Hz, satisfying our real-time criterion while maintaining stable performance over extended trajectories.

Figure 15.

Computation time breakdown per frame for major modules: millimeter-wave radar odometry (blue), loop closure detection (orange), and back-end pose graph optimization (yellow).

4.4.1. Short-Term Enhancement

To mitigate the negative impact of millimeter-wave radar feature fluctuations on loop closure detection, we propose a short-term loop closure enhancement method. This method constructs short-term features using inter-frame pose transformations provided by the radar odometry, which are then used as inputs for loop closure detection for the generation of Temporal Density Context (TDC). We first validated the impact of this enhancement on overall trajectory accuracy by performing experiments with and without the enhancement. We then conducted a statistical analysis of the loop closure detection results before and after removing the enhancement (Figure 16), investigating both the performance shifts and the corresponding input characteristics.

Figure 16.

Visualization of feature points and Temporal Density Context (TDC) for two adjacent frames before and after short-term loop-closure enhancement.The red and blue squares highlight corresponding regions of drastic inter-frame feature fluctuation in the point clouds and descriptors, respectively, demonstrating the improved stability.

As shown in Figure 13, removing the short-term loop closure enhancement resulted in a noticeable decrease in overall trajectory accuracy, with a smaller reduction compared to map constraints, but with a greater decline in accuracy for neighborhood and bridge scenarios compared to campus scenarios. As shown in Figure 14, after the removal, loop detection accuracy decreased, particularly in Riverside, likely due to obvious occlusions and repetitive features. However, incorporating features from short-term sequences increased correctly detected loop closures, enhancing the feature representation of spinning radar sensors.

4.4.2. Long-Term Enhancement

Given the continuous nature of vehicle trajectories, we propose a long-term loop closure enhancement algorithm. This algorithm amplifies the similarity differences between adjacent frames in forward and reverse loop closures to accurately eliminate loop closure outliers, thereby further ensuring the stability of loop closure constraints. Similar to the short-term loop closure enhancement algorithm, we evaluated the effectiveness of this algorithm by comparing changes in overall trajectory accuracy and differences in loop closure detection results before and after removing the enhancement, as illustrated in Figure 17.

Figure 17.

Comparison of the effects of long-term loop closure enhancement on forward and reverse loops before and after enhancement, showing significantly increased similarity for true forward and reverse loops compared with surrounding non-loop regions, thereby improving loop-closure robustness.

As shown in Figure 13, the removal of the long-term loop closure enhancement also led to a noticeable decrease in overall trajectory accuracy. The magnitude and trend of this decrease across most sequences are similar to those observed in the ablation experiments for the short-term enhancement. Precision–Recall analysis also showed a reduction in loop closure accuracy (Figure 14).

4.4.3. Adaptive Map Factors

OpenStreetMap typically exhibits relatively low single-point accuracy but high accuracy in topological relationships and geometric consistency. We leverage these characteristics to provide reliable prior pose information for our framework. When this module is removed, we observe varying degrees of accuracy degradation across different sequences, with the neighborhood and bridge scenarios experiencing the most significant impacts, while the campus scenario was less affected, which is shown in Figure 13.

To further investigate the robustness of our approach to potential inaccuracies in OSM geometry, we conducted a sensitivity analysis on the DCC01 sequence by introducing varying levels of artificial horizontal noise into the map-matching results. The noise levels were set to no noise, +5 m, +10 m, +20 m, and +50 m random displacement of matched positions, simulating different magnitudes of map geometry error. As shown in Table 3, the Absolute Trajectory Error (ATE) increased when noise was added, but our adaptive map-factor weighting maintained reasonable accuracy even at significant noise levels.

Table 3.

Sensitivity of trajectory accuracy to map-matching geometry errors (DCC01 sequence). All values are in meters (m).

5. Discussion

This section presents a thorough examination and reasoned discussion of the experimental outcomes, aiming to interpret the observed performance patterns, compare them across different scenarios, and assess their significance in validating the effectiveness of the proposed approach.

5.1. Analysis of Trajectory Accuracy and Consistency

The qualitative results indicate that our algorithm demonstrates good trajectory consistency and overall stability. During the trajectory generation process, we observed that the prior map information and the temporal enhanced loop constraints continuously adjusted the current trajectory. This was particularly evident in bridge scenarios, where the repeated roadside trees causing both GNSS and LiDAR-based odometry to struggle with maintaining accurate orientation. In these cases, the coarse but consistently stable map constraints and intermittent but high-precision loop closure constraints collectively ensured sufficient consistency between the trajectory and the ground truth. In contrast, other algorithms exhibited noticeable deviations in trajectories within the bridge scenarios, particularly those based on LiDAR, such as SC-LeGO-LOAM. This could be attributed to the relatively limited detection range of LiDAR, with LiDAR concentrating features on repetitive roadside objects like lamp posts and tree trunks, and struggling to reliably capture distant building features obscured by trees, leading to significant perceptual aliasing.

We observe in the quantitative results that, across most neighborhood, campus, and bridge scenarios, our algorithm achieves the highest ATE accuracy, with an average ATE of 5.93 m, and even reaches an error level of 1.83 m in the KAIST03 sequence. This suggests, to some extent, the overall effectiveness of our algorithm. Regarding the higher accuracy in the KAIST03 sequence, we attribute this to the presence of sufficient correct loop closures in the KAIST campus scenario, which helps maintain trajectory consistency. We also note that other algorithms, such as SC-ORORA and radarSLAM, performed better in the three KAIST campus sequences compared to the other two scenarios, which aligns with the trend observed in our algorithm. This trend may be due to the KAIST sequence having the most loop closures, which helps maintain the trajectory’s geometric integrity. Nevertheless, sustained high-accuracy localization remains challenging in our evaluation datasets due to two intrinsic factors: (i) the routes are relatively long (often larger than 1 km in the MulRan dataset) and involve numerous turns and U-turns, which compound drift accumulation; and (ii) the angular resolution of the current rotating millimeter-wave radar, which is approximately 0.9 degree, limits the precision of fine-scale geometric constraints. We performed optimization trials adjusting loop-closure thresholds and motion-model parameters, but the lower bound of 1.83 m persists, indicating that the limitation is primarily due to sensor and dataset characteristics rather than algorithmic design.

The bridge scenarios present a challenge due to their overall lack of distinctive features and repetitive features. LiDAR algorithms performed inconsistently in these scenarios, whereas millimeter-wave radar algorithms, despite potential end-point error increase, generally ensured better trajectory consistency. This could be due to the longer detection range and higher penetration of millimeter-wave radar, which allows it to capture a greater number of geometric structural features that are occluded by roadside trees. We observed a notable increase in error levels for our algorithm in the Riverside03 sequence. The trajectory plot reveals a deviation in the final orientation, which may be attributed to differences in vehicle movement trajectories and the geometric layout of the Riverside03 map compared to the other sequences. These differences likely caused deviations in the constraints. Similarly, LSRL experiences problems in Riverside03, which are attributed to outdated map data [59]. Despite these challenges, our observations indicate that, although the algorithm’s performance is influenced by map accuracy, it still maintains overall geometric consistency, demonstrating its fault tolerance.

Furthermore, the GNSS position variance analysis (Figure 9) in the DCC01 sequence shows that our method is capable of maintaining trajectory stability during periods of markedly increased GNSS standard deviation in all spatial dimensions. This illustrates the framework’s ability to compensate for degraded satellite positioning through radar odometry, loop-closure constraints, and adaptive map factors, thereby limiting drift accumulation despite highly variable GNSS precision. In the Twolochs forest canopy experiment (Figure 11), the dense, continuous canopy combined with irregular terrain and lack of distinct road geometry caused severe GNSS degradation and significant trajectory drift in raw GNSS data. Our system produced a smooth and stable estimation with an ATE of 6.75 m relative to the reference path, without reliance on structured road features. This confirms the applicability of the proposed framework to unstructured, topologically ambiguous environments where conventional GNSS and map-matching approaches fail.

5.2. Generalization in Complex Real-World Scenarios

From Figure 12, it can be observed that, regardless of canopy density, our system consistently produces trajectories geometrically aligned with the satellite road network while maintaining coherent radar feature point clouds. The fact that the positioning accuracy in these canopy-occluded scenarios remains close to that obtained on public datasets demonstrates the effectiveness and generalization capability of the proposed radar–OpenStreetMap fusion framework under forest-like GNSS-challenged conditions.

Comparative analysis with the Twolochs region in the OORD dataset (representing dense forest canopy conditions in the field) reveals notable differences in trajectory accuracy. While the millimeter-wave radar range resolution remained identical across the experiments, the campus scenarios were recorded with a shorter sensor detection range. Nevertheless, the average trajectory error in the campus canopy-occlusion dataset was consistently lower than that observed under dense forest canopy conditions. Specifically, in the Starlake Building area (sparse canopy cover), the trajectory error ratio was approximately 0.25%, and in the Youyi Square area (dense canopy cover), approximately 0.48%. In contrast, in the Twolochs region (dense forest canopy in unstructured environments), the trajectory error ratio rose to approximately 1.23%. These results indicate that trajectory error increases moderately with canopy density in campus environments, but rises more substantially in unstructured forest settings. We attribute this to the relative scarcity of regular geometric landmarks in the field, which reduces the availability of fine-scale geometric constraints and thereby contributes to higher error levels. In campus environments, abundant man-made structures such as planar building facades, orthogonal road intersections, cylindrical lamp posts, and even spherical decorative elements provide distinctive radar signatures that help stabilize trajectory estimation. In contrast, unstructured forest terrain is dominated by irregularly shaped vegetation and uneven ground surfaces, which lack consistent geometric patterns and thus offer fewer reliable constraints for precise localization.

5.3. Impact of Modules and Computational Efficiency

The short-term loop closure enhancement improves feature stability between adjacent radar frames, which is particularly beneficial in environments containing occlusions or repetitive structures, such as Riverside. By augmenting loop closure inputs with short-term sequences, the algorithm increases the number of correctly detected loop closures and enhances the representation capacity of spinning radar sensors.

The long-term enhancement contributes significantly to loop closure reliability by distinguishing forward and reverse loops, thereby reducing the number of false positives. In campus scenarios such as KAIST, the accuracy drop upon removal of this enhancement is less severe than in other sequences, suggesting that these environments inherently produce fewer erroneous loop closures. In the campus scenario, we observed that the reduction in accuracy after removing long-term loop closure enhancement was less significant compared to the reduction observed after removing short-term loop closure enhancement. This may be attributed to the relatively low number of erroneous loops in the KAIST scenario. Furthermore, the decrease in loop closure accuracy is more significant when long-term enhancements are removed, as shown in Figure 14. This also demonstrates the effectiveness of temporal enhancements in loop closure detection.

Map constraints from OpenStreetMap are especially critical in scenarios with sparse or unreliable loop closures, e.g., neighborhood and bridge environments. Without these constraints, accumulated pose estimation errors cannot be sufficiently corrected, leading to notable degradation in global trajectory accuracy. In contrast, campus scenarios benefit less from map constraints. This is likely because the campus scenario has a lower number of false loop closures. Even in the absence of reliable prior map information, the global constraints provided by these loop closures are sufficient to maintain overall trajectory consistency. In contrast, the neighborhood and bridge scenarios have fewer available loop closures. As a result, the absence of map constraints leads to accumulating errors that are not adequately corrected by the existing loop closures, resulting in noticeable accuracy degradation. To further examine the robustness of our mapping constraints module, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by introducing controlled horizontal noise into the OSM-matching outputs in the DCC01 sequence (Section 4.4.3). While the Absolute Trajectory Error gradually increased with larger injected noise levels (Table 3), the adaptive map factor weighting mechanism sustained reasonable accuracy even under severe geometric perturbations (up to 50 m displacement). This result suggests that the proposed framework can tolerate moderate map geometry errors without catastrophic performance loss, which is particularly relevant when using publicly available, crowd-sourced map data in areas where surveyed high-precision maps are unavailable.

Overall, the ablation study demonstrates that each enhancement contributes to the global accuracy, with the map constraint module providing the most pronounced improvements in challenging GNSS-denied and canopy-occluded environments.

6. Conclusions

This work proposes a spatial–temporal enhancement framework for millimeter-wave radar SLAM, combining open-source map priors from OpenStreetMap with a coarse-to-fine radar trajectory estimation pipeline. The spatial component employs map-based initialization with confidence-adaptive constraints, while the temporal component enhances radar odometry through short-term feature aggregation and long-term loop closure pruning. Together, these strategies yield geometrically consistent trajectories in GNSS-degraded urban environments.

Extensive experiments across neighborhoods, campuses, and bridge routes demonstrate that the proposed system improves trajectory accuracy and robustness under challenging conditions such as vegetation-induced signal loss. The framework achieves up to 55.23% reduction in Absolute Trajectory Error compared to baseline methods and reaches a minimum error of 1.83 m in canopies-occluded campus scenarios, confirming its capability to maintain precise localization during extended GNSS outages.

While the results are promising, certain limitations remain. The construction of the Temporal Density Context depends on radar feature quality and odometry estimates, which may vary with sensor models and algorithms. Furthermore, the current evaluation has been limited to urban and campus routes, and its behavior in large-scale environments featuring prolonged GNSS outages has yet to be confirmed. Future work will focus on extending and testing the framework in large-scale dense forest canopy conditions, where multipath effects, foliage attenuation, and extremely sparse radar landmarks pose additional challenges. Such scenarios would enable validation of the system’s long-term localization stability and broaden its applicability for autonomous navigation and mapping in natural GNSS-challenged terrains. In addition, future work will explore the use of higher-resolution radar sensors and the integration of inertial measurement units (IMU) or other complementary modalities, to provide tighter motion constraints and further enhance trajectory accuracy in GNSS-degraded conditions.

Author Contributions

Visualization, Y.T.; Investigation, Y.T.; Software, Y.T. and J.Z.; Validation, Y.T. and M.Y.; Writing—original draft preparation, Y.T.; Writing—review and editing, Y.T. and H.Z.; Supervision, J.Z.; Methodology, J.Z.; Project administration, J.Z.; Resources, B.L.; Data curation, M.Y. and S.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the State Key Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 52332010), the Key Research and Development Projects in Hubei Province (grant no. 2024BAB078) and the Major Program (JD) of Hubei Province (grant no. 2023BAA02604). The numerical calculations in this article were performed on the supercomputing system at the Supercomputing Center of Wuhan University.

Data Availability Statement

Data available in a publicly accessible repository “https://github.com/carbo-T/ROTE” (accessed on 14 November 2025).

Acknowledgments

We want to acknowledge Kai Liu for his help in data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Haoran Zhong and Shuiyun Jiang were employed by the China Ship Development and Design Center. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Zheng, S.; Wang, J.; Rizos, C.; Ding, W.; El-Mowafy, A. Simultaneous localization and mapping (slam) for autonomous driving: Concept and analysis. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Kaartinen, H.; Hakala, T.; Hyyppä, J.; Kukko, A.; Chen, R. Performance analysis of standalone UWB positioning inside forest canopy. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 9511214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Qi, S.; Zhou, J.; Tang, Y.; Yang, J.; Xin, J. High-precision positioning, perception and safe navigation for automated heavy-duty mining trucks. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024, 9, 4644–4656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Shang, G.; Ji, A.; Zhou, C.; Wang, X.; Xu, C.; Li, Z.; Hu, K. An overview on visual slam: From tradition to semantic. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Kaartinen, H.; Hakala, T.; Hyyti, H.; Kukko, A.; Hyyppa, J.; Chen, R. Comparative Analysis of Ultra-Wideband and Mobile Laser Scanning Systems for Mapping Forest Trees under A Forest Canopy. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2025, X-G-2025, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.; Petillot, Y.; Wallace, A.; Wang, S. RadarSLAM: A robust simultaneous localization and mapping system for all weather conditions. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2022, 41, 519–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liang, X.; Campos, M.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y. Benchmarking of Laser-Based Simultaneous Localization and Mapping Methods in Forest Environments. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5706221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, D.; Weston, R.; Posner, I. Masking by Moving: Learning Distraction-Free Radar Odometry from Pose Information. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.03752. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, D.; Posner, I. Under the radar: Learning to predict robust keypoints for odometry estimation and metric localisation in radar. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Paris, France, 31 May 2020–31 August 2020; pp. 9484–9490. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett, K.; Yoon, D.J.; Schoellig, A.P.; Barfoot, T.D. Radar odometry combining probabilistic estimation and unsupervised feature learning. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.14152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.; Zheng, Z.; Zhao, M. CartoRadar: RF-Based 3D SLAM Rivaling Vision Approaches. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking (ACM MobiCom ’25), Hong Kong, China, 4–8 November 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sie, E.; Wu, X.; Guo, H.; Vasisht, D. Radarize: Enhancing Radar SLAM with Generalizable Doppler-Based Odometry. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM International Conference on Mobile Systems, Applications, and Services (ACM MobiSys ’24), Tokyo, Japan, 3–7 June 2024; pp. 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolfsson, D.; Magnusson, M.; Alhashimi, A.; Lilienthal, A.J.; Andreasson, H. Lidar-Level Localization With Radar? The CFEAR Approach to Accurate, Fast, and Robust Large-Scale Radar Odometry in Diverse Environments. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2022, 39, 1476–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, K.; Schoellig, A.P.; Barfoot, T.D. Do we need to compensate for motion distortion and doppler effects in spinning radar navigation? IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohling, H. Radar CFAR thresholding in clutter and multiple target situations. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 1983, AES-19, 608–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, S.H.; Newman, P. Precise ego-motion estimation with millimeter-wave radar under diverse and challenging conditions. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 21–25 May 2018; pp. 6045–6052. [Google Scholar]

- Cen, S.H.; Newman, P. Radar-only ego-motion estimation in difficult settings via graph matching. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 May 2019; pp. 298–304. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Duan, Y.; Fan, X.; Meng, C.; Ji, J.; Zhang, Y. MAROAM: Map-based Radar SLAM through Two-step Feature Selection. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.13797. [Google Scholar]

- Checchin, P.; Gérossier, F.; Blanc, C.; Chapuis, R.; Trassoudaine, L. Radar scan matching slam using the fourier-mellin transform. In Proceedings of the Field and Service Robotics: Results of the 7th International Conference, Cambridge, MA, USA, 14–16 July 2009; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 151–161. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.S.; Shin, Y.S.; Kim, A. Pharao: Direct radar odometry using phase correlation. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Paris, France, 31 May–31 August 2020; pp. 2617–2623. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, H.; Jeon, J.; Myung, H. UV-SLAM: Unconstrained line-based SLAM using vanishing points for structural mapping. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 1518–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Wang, B.; Huai, J.; Li, M. 4D iRIOM: 4D imaging radar inertial odometry and mapping. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 3246–3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Mo, H.; Tang, S.; Zhang, X.; Li, Q. Backpack LiDAR-based SLAM with multiple ground constraints for multistory indoor mapping. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5705516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Xue, H.; Si, S.; Xiao, L.; Zhao, D.; Zhu, Q.; Nie, Y.; Dai, B. R2SCAT-LPR: Rotation-Robust Network with Self-and Cross-Attention Transformers for LiDAR-Based Place Recognition. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Zhou, J.; Li, B.; Dong, Z.; Tang, Y.; Xiao, J. RoCalib: Large-Scale Autonomous Geo-Calibration for Roadside Lidar with High-Definition Map. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 13734–13749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, S.; Neubert, P.; Garg, S.; Milford, M.; Fischer, T. Visual place recognition: A tutorial. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2023, 31, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]