Highlights

What are the main findings?

- An end-to-end automated system was developed to calculate rice-lodging rates within a parcel using drone RGB imagery combined with lightweight deep-learning segmentation and geometric post-processing.

- The proposed MobileNetV1_LR-ASPP model, together with the post-processing algorithm, effectively corrected collapsed parcel boundaries and improved parcel-level mIoU to 0.966.

What are the implications of the main finding?

- The system enables objective and reproducible lodging assessment without manual intervention, supporting large-scale monitoring, insurance evaluation, and disaster-response applications.

- Its lightweight architecture and compatibility with embedded devices facilitate practical deployment in field-based smart-farming environments.

Abstract

Rice lodging, a common physiological issue that occurs during rice growth and development, is a major factor contributing to a decline in rice production. Current techniques for the extraction of rice lodging are subjective and require considerable time and labor. In this paper, we propose a fully automated method in an end-to-end format to objectively calculate the rice-lodging rate based on remote sensing data captured by a drone under field conditions. An image post-processing method was applied to enhance the semantic-segmentation results of an operable lightweight model on an embedded board. The area of interest within the parcel was preserved based on these results, and the lodging occurrence rate was calculated in a fully automated manner without external intervention. Five models were compared based on the U-Net and lite-reduced atrous spatial pyramid pooling (LR-ASPP) models with MobileNet versions 1–3 as the backbones. The final model, MobileNetV1_U-Net, performed the best with an RMSE of 11.75 and R2 of 0.875, and MobileNetV3_LR-ASPP (small) achieved the shortest processing time of 4.9844 s. This study provides an effective method for monitoring large-scale rice lodging, accurate extraction of areas of interest, and calculating lodging occurrence rates.

1. Introduction

Rice, corn, wheat, barley, and sorghum are among the five most widely produced grains worldwide [1]. Until 2020/21, rice production consistently outpaced its consumption; however, consumption began to surpass production in 2021/22 owing to poor weather conditions in major supplying countries like India and Pakistan [2]. Considering the steady increase in the world population, the food crisis must be actively responded to by introducing highly efficient mechanized farming methods and eliminating factors that reduce rice production despite the high mechanization rate of 97.8% in rice farming [3].

Rice lodging is a common physiological issue that occurs during rice growth and development. It is a major factor contributing to the decline in rice production and is closely related to cultivar characteristics, cultivation techniques, fertilizer amounts, water management, cultivation methods, planting density, pests, and weather conditions such as heavy rain or typhoons. Seed germination damage, where rice sprouts appear on rice ears because of lodging, significantly impacts the yield and quality of rice [4]. Rapid and accurate extraction of information, such as the location and area of rice lodging, is crucial for assessing rice cultivation disasters and realizing agricultural disaster insurance, government disaster management measures, and subsidy support. In addition, the government can use the analyzed rice lodging damage data as the basis for producing and supplying high-quality seeds through the seed system for rice varieties. The traditional method for analyzing rice-lodging damage typically involves dispatching investigators with extensive expertise and experience, making it subjective and requires significant time and human labor.

Recently, the entry barriers to remote sensing research have been lowered owing to the expansion of low- to mid-priced remote sensing equipment, such as drones, alongside advancements in remote sensing technology, such as the use of high-resolution multi-functional sensors, resulting in improved image quality. Consequently, various remote sensing studies have been conducted in fields such as disaster and accident analysis, military applications, and mineral exploration [5,6,7,8]; subsequently, aerial images are widely used in agricultural remote sensing research for applications such as pinewood nematode detection, prediction of cabbage production in cold regions, and recognition of rice-lodging area [9,10,11,12]. Traditionally, experts performed information analysis tasks, such as detection and prediction, manually, requiring considerable time and resources. However, research is now focusing on automation through deep learning-based image processing technologies to enhance efficiency [13].

In the field of image processing, deep learning applications are primarily categorized into three: classification, object detection, and segmentation [14,15,16]. Classification involves assigning a single value to categorize the input image. Object detection entails simultaneously identifying the category and location of multiple objects in an image. Segmentation is the task of assigning specific attributes to each pixel of an image, which is further divided into semantic and object segmentation. Semantic segmentation classifies a distinguished attribute into a specific category, whereas object segmentation, as the name suggests, corresponds to each distinguished attribute of each entity. For example, when analyzing a crowd gathered in a square, semantic segmentation involves classifying the crowd as a whole into a category of people, whereas object segmentation involves identifying each person in the crowd as a distinct object. Classification, object detection, and segmentation techniques can be used to analyze aerial images.

A technology to differentiate the parcels being analyzed is needed to effectively utilize aerial images captured by aircraft such as drones and satellites. Although each parcel can be distinguished using GPS and cadastral map information, GPS accuracy may vary depending on the aircraft type or environmental conditions; moreover, cadastral maps lack real-time capabilities and fail to account for illegally constructed buildings or reclaimed land. To address these shortcomings, features from aerial images must be utilized, particularly in the precision agriculture field.

With the widespread use of drones, sensors, and artificial intelligence, remote sensing technology is increasingly being employed in smart precision agriculture. Rajapaksa et al. [17] extracted texture features from drone images of wheat and canola planting parcels using gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM), local binary pattern, and Gabor filter, and support vector machine–based classifiers for each type of feature to determine whether a parcel was lodged or not. The GLCM features performed best, achieving prediction accuracies of 96.0% for canola and 92.6% for wheat, with qualitative visualizations illustrating spatial distributions between and within parcels. In the study by Rajapaksa et al. [17], color information is removed when gray scale is used instead of RGB scale, making it difficult to detect slight lodges. Mardanisamani et al. [18] used multispectral equipment to acquire five spectral channel orthoimages for the lodging classification of canola and wheat and proposed a deep convolutional neural network (DCNN) architecture with significantly fewer parameters but achieved comparable results to those of existing lodging analysis models. The DCNN model, which was trained on multi-channel images acquired using multispectral equipment, shows high analysis performance compared to the RGB scale, but the equipment is expensive, and the size of the DCNN model is large, making it difficult to make it lightweight for mobile use. Yang et al. [19] proposed a mobile U-Net model that integrated a lightweight neural network, depthwise separable convolution, and a U-Net model to recognize rice lodging based on RGB images acquired from uncrewed aerial vehicles (UAVs). By constructing a four-channel fusion image that included RGB with a digital surface model (DSM) and RGB with excess green (ExG), they obtained an F1-Score of 88.99%. The ExG index is one of the key indices used when analyzing crop canopies. However, because ExG is derived from RGB images, its use as input to the U-Net model is questionable. Su et al. [4] proposed a semantic image segmentation method based on a U-Net network to identify end-to-end, pixel-to-pixel rice lodging by leveraging the benefits of dense blocks, DenseNet architecture, attention mechanisms, and jump connections to process input multiband images and achieved a model accuracy of 97.30%. The applied mechanisms appear to be very effective in exploring crop lodges. When reviewing existing research, it seems necessary to consider the development direction of crop lodge detection, such as detection accuracy and model lightweighting (mobile possibility).

In previous studies, lodging characteristics are generally analyzed across entire aerial images using classification or segmentation techniques, or through manually selected subregions for detailed assessment [4,8,17,18,19]. However, these approaches inherently introduce subjective dependence in region delineation and result interpretation, thereby limiting the reproducibility and quantitative reliability of lodging analysis. In particular, existing deep-learning models often overlook the scientific challenge of spatial inconsistency arising from heterogeneous canopy textures, illumination variations, and boundary degradation between adjacent parcels. These factors cause instability in pixel-level prediction and undermine the accuracy of lodging quantification at field scale. To address these gaps, this study proposes a scientifically grounded, fully automated segmentation framework that integrates a lightweight deep neural network with a mathematical post-processing algorithm to preserve parcel boundaries. The framework improves objectivity, reproducibility, and statistical validity of lodging detection by minimizing human intervention and modeling spatial uncertainty. Furthermore, the system operates in a end-to-end architecture that directly encrypts and transmits analytical results to prevent manipulation or bias, enabling secure and unbiased lodging evaluation. This approach represents a novel methodological contribution that links algorithmic transparency and quantitative rigor to the practical implementation of precision agriculture and large-scale crop damage assessment.

Therefore, in this study, we aimed to develop a method for fully automating a rice-lodging analysis system in an end-to-end format without any external subjective intervention. We propose a fully automated, mobile-friendly method for accurately detecting and segmenting rice-lodging areas using lightweight models optimized for real-time processing on embedded boards. It addresses the challenges of boundary collapse arising from image resolution and ensures an objective end-to-end interpretation, making it practical for precision agriculture and large-scale disaster assessments.

2. Materials and Methods

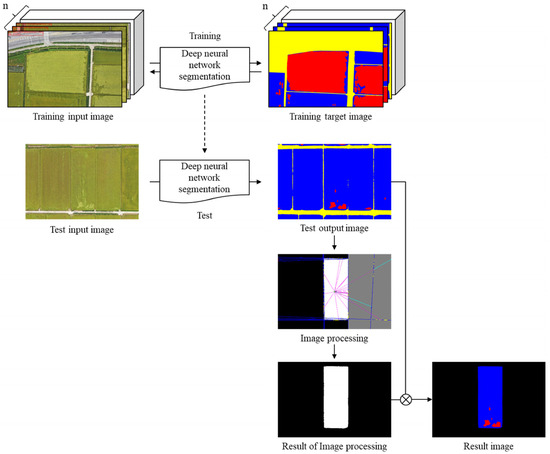

This paper introduces a drone-based, end-to-end automated rice lodging detection system, illustrated in Figure 1. The images collected by drones in various areas (rice-lodging, normal-rice, and background areas) were classified as training and test images. The images were labeled for semantic segmentation using deep learning. A deep neural network segmentation model was trained using the drone footage as input and labeled footage as output. On evaluating the deep learning algorithm trained with the test images, the boundaries between the parcels were unclear, as shown in the center of Figure 1. Only the parcel of interest was accurately segmented using an image post-processing algorithm. The image at the bottom of Figure 1 shows the result of outputting only the lodging information of the parcel of interest. The lodging rate within the parcel can be derived based on this result.

Figure 1.

The process of parcel segmentation using aerial images.

The end-to-end automated system process is shown in Figure 1; a deep neural network segmentation model was adopted to be processed as a computational resource for an embedded board. To ensure detailed structuring, the U-Net [20] and lite reduced atrous spatial pyramid pooling (LR-ASPP) models were used with MobileNets [21,22,23], a lightweight deep neural network designed by Google for efficient computation in resource-constrained environments such as mobile devices and embedded boards, as the backbone. MobileNets are lightweight convolutional neural networks (CNNs) that utilize depthwise separable convolution and inverted residual structures, and are representative backbones designed for mobile and embedded environments. MobileNets are widely used in various applications as the backbone of lightweight semantic segmentation models [24,25,26]. In addition, it has been reported in several benchmarks and on-device experiments that the TFLite/PyTorch model of the MobileNet series is capable of real-time inference at the level of tens of frames per second on ARM-based edge devices such as Raspberry Pi [27,28], and is evaluated as a stable choice in terms of latency even in actual embedded environments.

The model parameters were adjusted to align with the research objective, allowing the entire input image size of 1920 × 1280 pixels to be processed at once without splitting it despite the standard 224 × 224 pixels input size of the existing deep neural network segmentation model. In this section, the data collection environment used for the experiment to verify the proposed method, data pre-processing method, detailed structure of the deep learning–semantic-segmentation method used to detect rice-lodging areas, detailed description of the image post-processing algorithm that accurately detects only the parcel of interest based on the results of the semantic segmentation, and detailed description of the evaluation method is presented.

2.1. Data Collection

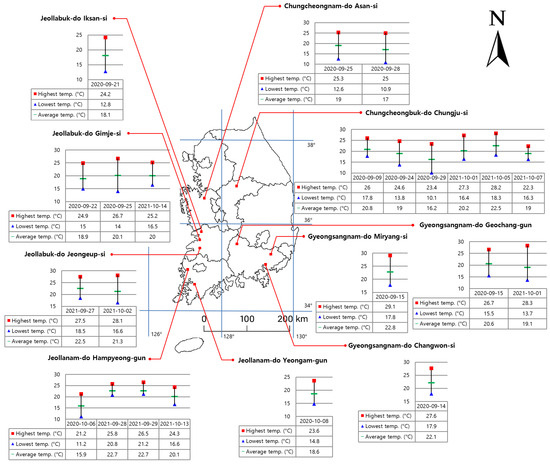

Approximately 70% of the Korean peninsula is mountainous; however, the study areas were distributed at an elevation of approximately 50 m or less (Figure 2; Geochang-gun, Gyeongsangnam-do is an exception, with an elevation of approximately 200 m) and are located at approximately 36°00′N and 127°50′E. The climate is continental, with hot summers and cold winters. The average temperature in summer (August) on the Korean peninsula is around 25 °C, and the daily highest temperature is over 30 °C, which is comparable to that in the tropics; the temperature in winter (January) ranges from −20 °C to 0 °C, making the region extremely cold, similar to the polar region [29]. The average precipitation is 500–1700 mm, and the national average is 1190 mm. As of 2023, 384,000 households out of 999,000 total farm households (38%) were involved in rice production, and 764,000 ha out of 1,512,000 ha of total cultivated land (50.5%) were engaged in paddy farming because of the distinct weather of the four seasons and high rainfall [30,31]. In addition to rice, the major food crops in Korea include barley, wheat, corn, soybean, and sorghum [32].

Figure 2.

Details of parcel segmentation data collection using aerial images.

The following typhoons occurred on the Korean peninsula during 2020–2021 between late summer and early fall: No. 5 ‘Jangmi,’ No. 8 ‘Bavi,’ No. 9 ‘Maysak,’ and No. 10 ‘Haishen’ (in 2020) and No. 3 ‘Lupit,’ No. 12 ‘Omais,’ and No. 12 ‘Chanthu’ (in 2021) [33,34]. Several typhoons accompanied by strong winds and rain affected the occurrence of rice lodging. Researchers assessed rice lodging damage by capturing aerial images at multiple angles and heights ranging from 20 to 135 m over farmland in Jeolla-do, Gyeongsang-do, and Chungcheong-do during August and September of 2020 and 2021. The raw data was collected as an RGB image with a width of 5472 pixels and a height of 3078 pixels. Table 1 and Figure 2 detail the collected data. Because it was not possible to record cultivar information for all fields where data were collected, information on representative cultivated cultivars was entered in Table 1. The study gathered 335 data points from Jeollabuk-do, 34 from Jeollanam-do, 112 from Gyeongsangnam-do, 143 from Chungcheongbuk-do, and 74 from Chungcheongnam-do locations. Across the data collection period, the lowest temperature was 10.1 °C, the highest temperature was 29.1 °C, and the average temperature was 19.9 °C, showing a wide daily temperature range. On the Korean Peninsula, rice is a single crop, and the harvest season for all rice plants is from September to October. All rice plants included in the data are in the fruiting period.

Table 1.

Aerial image data collection information.

South Korea, located between latitudes 33 and 39 degrees, has an annual rice cultivation area of approximately 700,000 hectares, with production reaching approximately 3.07 million tons (Table 2). Data collection areas, including Jeolla-do (Jeollabuk-do + Jeollanam-do), Gyeongsangbuk-do, and Chungcheong-do (Chungcheongbuk-do + Chungcheongnam-do), encompass the Honam Plain and Gimhae Plain, and account for approximately 68% of the total rice cultivation area and 69% of total production. Approximately 84% of South Korea’s rice cultivation area and production falls below a latitude of 37 degrees. Considering the characteristics of crops, which are significantly influenced by latitude [35], it can be concluded that these data collection areas are highly representative and correlated with South Korea’s rice production.

Table 2.

Rice production by province in South Korea.

2.2. Data Pre-Processing

2.2.1. Image Labeling

To train the deep learning model for the semantic-segmentation method, each class to be estimated must be assigned to each pixel of the image. In the collected images, there were differences in color depending on the environment and growth conditions, such as the growth stage of the rice, time zone, and weather. Furthermore, the areas damaged by lodging are also presented differently depending on the degree of damage and parcel characteristics. In addition, depending on the location and height of the drone that captured the image, various terrains such as roads, greenhouses, and houses other than farmland were included. Terrain features with low visibility owing to resolution limitations, especially rice field ridges corresponding to the boundaries of parcels, were also captured. Therefore, to clearly distinguish the boundaries between the fields, labeling was performed using red, blue, and yellow as the lodged, normal, and background areas, respectively, as shown in the training target image at the top of Figure 1. A total of 698 images were collected, and the labeling was completely performed on these images; thus, an equivalent of 1,693,286,400 pixels was labeled.

2.2.2. Image Augmentation

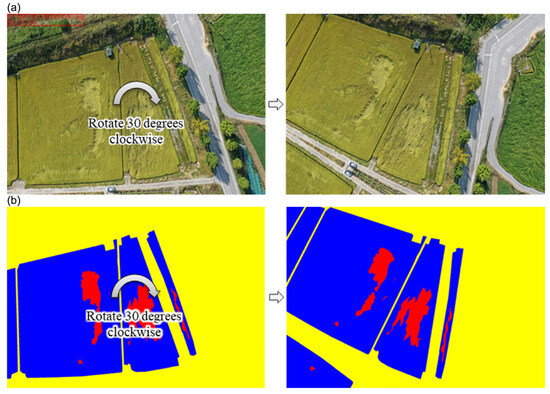

Deep learning models show optimal performance when trained using high-quality large data; however, the number of collected data points was 698, which is insufficient to train and optimize a model and can lead to overfitting. To address these issues, we applied a transfer learning method that trains the weights of MobileNets using ImageNet open data to extract the features of the filter and a method that randomly reconfigures the order of the training data at each epoch to prevent overfitting. Because the drone captured the images from a vertical perspective at the horizon, the images from up, down, left, or right directions did not differ. Therefore, as shown in Figure 3, data augmentation was performed to rotate the image to an arbitrary angle using the rotation operation, and the empty space was filled using the reflection operation. The original image in Figure 3 shows that the data augmentation did not place the rice fields, which were the target images for training, out of position, whereas roads and similar terrains were modified into a different form.

Figure 3.

Example of image augmentation using rotation. (a) before and after rotation of the original RGB image; (b) before and after rotation transformation of labeled image.

2.3. Semantic-Segmentation Model Construction

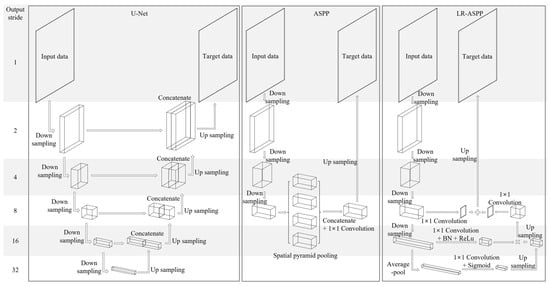

In the estimation of rice-lodging area and shape, errors owing to the diversity of the surrounding environment must be minimized. A model that ensures high performance while being light must be configured to end-to-end the proposed system using an embedded board. In this study, we compared and analyzed the computational speed, number, and performance of the U-Net and LR-ASPP models using MobileNets as the backbone network. In this section, we present the structure of MobileNets and its three versions, 1–3; the U-Net, a semantic-segmentation model; and the LR-ASPP model in detail.

We adopted the semantic-segmentation model instead of the instance-segmentation model for segmenting the rice-lodging area because we needed to quantify the occurrence rate of a specific symptom called lodging within the field. Because semantic segmentation is classified into only three classes (lodging, normal, and background areas), it can efficiently handle lodging areas that may either form small particle clusters or occur in large chunks; thus, it is easy to calculate the lodging occurrence rate.

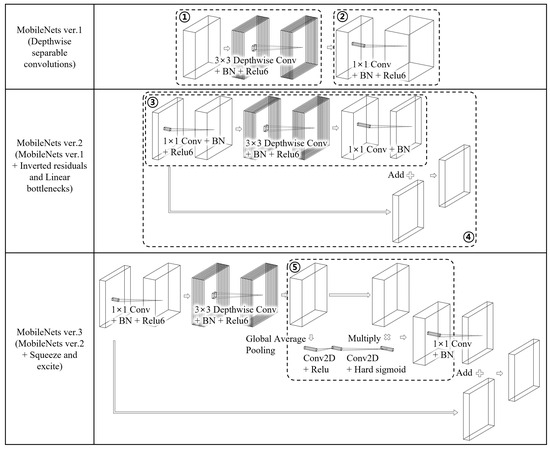

2.3.1. MobileNets Model

MobileNets is a lightweight deep neural network designed for efficient computation in resource-constrained environments, such as mobile devices and embedded boards. It was developed by Google in 2017 [21,22,23]. MobileNet is widely used for various computer vision tasks, including image classification, object detection, and semantic segmentation. MobileNets has been developed up to the third version, and its main block structure is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Block structure for all versions of MobileNets. MobileNets ver. 1: a structure based on depthwise separable convolutions; MobileNets ver. 2: a structure that introduces the concepts of inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks to depthwise separable convolutions; and MobileNets ver. 3: the concepts of squeeze and excitation module, network search, and nonlinearity are added to MobileNet ver. 2. BN indicates batch normalization.

Early MobileNet models employed depthwise separable convolutions, significantly lowering parameter count and computational demand versus standard CNNs. This enabled their deployment in resource-constrained environments. Depthwise separable convolutions are based on the idea that the number of learning weights can be drastically reduced by separating the spatial and dimensionality of the filters. The standard convolution operation applies a convolution kernel of size to an input tensor of size , which performs convolutions in both channel and spatial directions simultaneously, producing an output tensor of size , with the following computational cost:

Here, represents the height of the tensor, is the width of the tensor, is the depth of the tensor, is the width and height of the kernel, is the input tensor index, and is the output tensor index. Conversely, depthwise separable convolutions sequentially perform depthwise convolution in the spatial direction, as shown in ① in Figure 4, and pointwise convolution in the channel direction, as shown in ② in Figure 4. The computational costs for depthwise and pointwise convolutions are calculated as follows.

Because the depthwise and pointwise convolutions of depthwise separable convolutions operate independently, the computational cost of MobileNetV1 is as follows:

The computational cost is reduced by rearranging Equations (1) and (4).

The second version of MobileNets introduced the concepts of inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks to the depthwise separable convolutions of the first version. When an image is input into a deep neural network that has completed training, the features of the input image are activated in a specific low-dimensional region, and the features of the image are extracted. As high-dimensional data are compressed into a low-dimensional region, specific information is mapped to a certain low-dimensional region, called a manifold, and the region where similar features are mapped is called the “manifold of interest.” When the input image, embedded into a low-dimensional region, is projected again, the manifold of interest, which is a crucial part of the input, can be transferred to the low-dimensional region through the layer. If the layering is transformed linearly, the information is assumed to be preserved [22]. Therefore, a linear bottleneck structure that removes the nonlinear ReLU function from the bottleneck would show better performance than the existing bottleneck structure, and this was proven through experiments using the CIFAR dataset. The structure of linear bottlenecks is shown in ③ of Figure 4. After the bottleneck process of expansion, depthwise convolution, and projection, the nonlinear ReLU operation is removed at the last layer to maintain the manifold of interest. The existing bottleneck structure has a narrow structure, in which the number of channels of the feature map located in the center is less than the number of channels of the input and output at both ends of the block. This structure is commonly used because deep neural networks, such as AutoEncoder, divide the encoding and decoding structures based on the center of a narrow bottleneck [36]. The residual network structure was designed to add values before an operation is performed in block units to address problems such as gradient vanishing and overfitting in deep neural networks. The blocks of the existing residual network use a bottleneck structure with a narrow center [37,38]. However, MobileNetV2 is based on the assumption that only the necessary information is compressed and stored in the low-dimensional layer and has an expansion structure in which the number of feature map channels located at the center is greater than the number of input and output channels of the block, as shown in ④ of Figure 4, contrary to the existing bottleneck structure. The inverted residuals perform internal block operations with an expansion bottleneck structure, and the validity of the modified structure has been verified through experiments [22]. The computational cost of MobileNetV2, which includes depthwise separable convolutions, inverted residuals, and linear bottlenecks, when the input tensor of size is used with the expansion factor and kernel of size to generate an output tensor of size is as follows.

Comparing Equations (4) and (9), MobileNetV2 appears to require a greater number of computations than MobileNetV1 because it has an additional convolution layer corresponding to the expansion factor . However, because the number of channels of the input and output tensors of MobileNetV2 ( and , respectively) is less than that of MobileNetV1, and the computational cost of MobileNetV2 is lower.

The last version of MobileNet introduces three concepts into the second version of MobileNet: the squeeze and excitation module, network search, and nonlinearity. The squeeze and excitation module is designed to be placed after the depthwise filter with a structure as shown in ⑤ of Figure 4, so that attention can be applied to the largest expanded representation. When the squeeze and excitation module generates an output tensor of size using size l of the intermediate filter on the input tensor of size , it has the following computational cost:

Using the squeeze and excitation module is advantageous as it is almost cost-free compared to the computational cost and latency associated with depthwise separable convolutions, inverted residuals, and linear bottleneck modules. Network search has proven to be a powerful tool for discovering and optimizing network architectures [39,40,41,42]. In the case of MobileNetV3, Platform-Aware NAS is used to search for a global network structure that optimizes each network block to minimize latency and maximize accuracy. The NetAdapt algorithm is then used to determine the number of filters in each layer. Consequently, MobileNetV3 has different structures for each layer, unlike previous versions, where the network structure and number of filters are simple and uniform. Furthermore, a nonlinearity called Swish was introduced as a replacement for the ReLU activation function, which greatly improved the accuracy of the neural network [43,44,45].

Although this nonlinearity helps improve accuracy, the sigmoid operation included in the formula is expensive. To overcome this limitation, we introduce squeeze and excitation modules with hard-sigmoid and hard-swish operations, respectively, which can reduce the number of memory accesses in the final parts of the network and considerably reduce latency costs.

2.3.2. U-Net Model

U-Net, an image segmentation model using deep learning, belongs to an encoder–decoder-based model, such as an autoencoder. In the encoding stage, the autoencoder usually increases the number of channels and reduces the size of the image to capture the features of the input image, whereas, in the decoding stage, it reduces the number of channels and increases the size of the image using only the low-resolution encoded information to restore the high-resolution image. When reducing the size during encoding, much of the image object’s detailed features are lost. Since decoding only relies on low-resolution data, these features cannot be restored. The basic idea of U-Net is to extract the features of an image not only under low-resolution conditions but also by using high-resolution information. To this end, a concatenation method combines the features obtained from each layer of the encoding stage into each layer of the decoding stage, as shown in the first part of Figure 5. The original U-Net extracts image features by performing a 3 × 3 convolution operation and a 2 × 2 max-pooling operation in each layer.

Figure 5.

The basic structure of U-Net, atrous spatial pyramid pooling (ASPP), and lite residual ASPP (LR-ASPP); BN stands for batch normalization.

2.3.3. Lite R-ASPP

Another network that uses MobileNets as a backbone is LR-ASPP. The atrous spatial pyramid pooling (ASPP) module [24,25,46], which has the same structure as shown in the second part of Figure 5, uses atrous convolution. ‘Àtrous’ means ‘having a hole,’ which is made to maintain the resolution of the kernel of spatial pyramid pooling. In [22], the residual ASPP (R-ASPP) architecture was proposed, which introduces inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks into the spatial pyramid pooling module. The Lite R-ASPP (LR-ASPP) architecture, which similarly distributes global average pooling to that by the squeeze-and-excitation module, is an improvement over R-ASPP [23]. In LR-ASPP, a large pooling kernel with a large stride (to save computational amount) and single 1×1 convolutions are used. In addition, atrous convolution is applied to the last block to extract denser features, and skip connections are added to low-level features to capture more detailed information.

2.3.4. Proposed Semantic-Segmentation Model

The proposed semantic-segmentation models were defined as five models, as shown in Table 3. Each model consists of a backbone that extracts features and a segmentation head that uses these features to perform the actual desired task, semantic segmentation. ‘MobileNetV1-UNet’ consists of a U-Net segmentation head and a MobileNetV1 backbone, ‘MobileNetV1-LR-ASPP’ consists of a LR-ASPP segmentation head and a MobileNetV1 backbone, ‘MobileNetV2-LR-ASPP’ consists of a LR-ASPP segmentation head and a MobileNetV2 backbone, ‘MobileNetV3-LR-ASPP (small)’ consists of a LR-ASPP segmentation head and a MobileNetV3 (small) backbone, and ‘MobileNetV3-LR-ASPP (large)’ consists of a LR-ASPP segmentation head and a MobileNetV3 (large). The network structures of each model are shown in Appendix A. The U-Net segmentation head structure was applied only to MobileNetV1 because we experimentally confirmed that convergence did not occur when the U-Net segmentation head was applied to the structural characteristics of MobileNetV2 or MobileNetV3.

Table 3.

Proposed semantic-segmentation models.

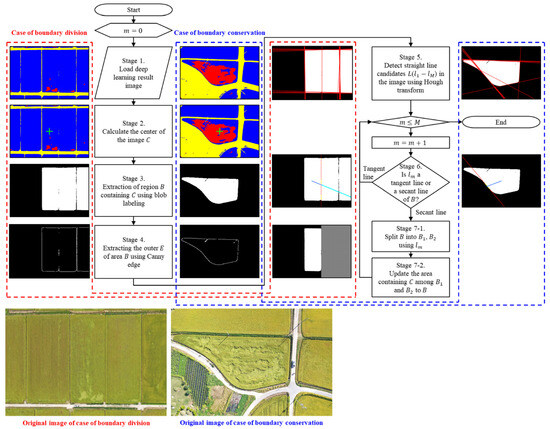

2.4. Post-Processing of Segmented Results

Remote sensing technology has advanced to enable the acquisition of high-resolution aerial images. However, owing to the nature of aerial images that cover a wide area, especially that of images captured using UAVs such as general-purpose drones, the captured images do not have a resolution that includes all the ground features. Accordingly, even with the use of high-performance deep learning technology, instances where the limitations of the image prevent precise analysis can occur. For the task of lodging occurrence rate calculation using aerial images, the ultimate goal is to automate the process. Because most farmlands are located in areas suitable for farming, parcels are formed with ridges between rice paddies as the boundary; however, owing to resolution issues, the certainty of parcel boundaries in aerial images is often low. Therefore, in this study, we used an image post-processing method, as shown in Figure 6, to clearly divide the parcel of interest and background area in the deep neural network segmentation results, thereby improving the performance of measuring the lodging occurrence rate per parcel.

Figure 6.

Flowchart for the post- processing of deep learning segmentation result.

Figure 6 shows the image processing protocol for segmenting the parcels of interest using a flowchart, along with two examples each from cases where the corresponding process is segmented in the form of an image and where the corresponding process is preserved. In Stage 1 of Figure 6, the deep neural network segmentation result image is loaded. When segmenting the boundary line, the left boundary line of the parcel of interest is divided from the background and parcels; however, the right boundary is not clearly segmented from the right side of the parcel because of incomplete deep neural network segmentation. In this study, we collected data from the center of the image as the parcel of interest. We designated the center of the image as the point of interest as shown in Stage 2 of Figure 6. An option for selecting a point of interest can be added based on the user’s choice. In Stage 3 of Figure 6, connected component labeling [47] distinguishes the normal, overgrown, and background areas corresponding to the parcel. Even when the background is excluded, other parcels captured in the surrounding and parcels of interest are included.

After the connected component labeling process, blobs are formed with different labels for each background area and segmented parcel. The label number of all pixels in the entire image, which is the same as the label value of pixel is converted to a true value (indicated as the white area in Stage 3 of Figure 6 representing a parcel candidate blob); otherwise, it is converted to a false value (indicated as the black area in Stage 3 of Figure 6 representing a background area), and the parcel candidate blob is identified. Through , we could verify again that deep neural network segmentation does not always accurately segment parcels. As a pre-processing step to find straight lines surrounding , edge of is searched using Canny edge detection [48], as shown in Stage 4 of Figure 6. The searched components of are applied to the Hough transform [49] to detect the straight lines surrounding where is the number of straight lines . The two examples of segmenting and preserving the boundary in Stage 5 of Figure 6 are the results of drawing on . Straight lines (named as secant lines for convenience) that divide the area of actual interest and other areas can be observed along with straight lines that do not exist together among all the straight lines L in the left image. In the right image, straight lines that do not divide can be seen along with straight lines (named as tangent lines for convenience) that divide but do not participate in the division because the area that is being divided is the actual area of interest. Stage 6 in Figure 6 explains how to divide into the tangent and secant lines.

- The intersection pixels of the pixel components forming straight line and the pixel components forming are identified.

- The intersection pixels are sorted by the position value, and the pixel with the middle value is set as the representative pixel .

- The straight-line distance between and is estimated.

- The straight-line distance from to the outermost point of , passing through , is estimated.

- Using Equation (14), the tangent probability is calculated. If the is greater than or equal to 0.9, it is considered a tangent; otherwise, it is considered a secant.

As shown in Stage 7 of Figure 6, if is a secant, is divided by into and . Finally, the area including in and is updated to . Stages 6 and 7 are repeated for all straight lines included in .

2.5. Evaluation Indicators

To ensure that the system evaluation is consistent with the goal of this study, four aspects of evaluation indices were examined to optimize the accuracy-latency balance of mobile devices. First, the segmentation performances of the semantic-segmentation models described in Section 2.3 were compared categorically for evaluation using precision, recall, F1-score, and intersection over union (IoU) [4]. The following formulae were used.

where stands for true positive, which refers to the number of cases where the actual true values were correctly predicted as true by the segmentation model, TN stands for true negative, indicating the number of cases where the actual false values were correctly predicted as false, FP stands for false positive, representing the number of cases where the actual false values were incorrectly predicted as true, and FN stands for false negative, indicating the number of cases where the actual true values were incorrectly predicted as false by the segmentation model. Next, overall accuracy (OA) and mean intersection over union (mIoU) were used to compare the performances of the image post-processing algorithms using model [4]. The following formulae were used.

where denotes the number of categories. Third, to evaluate the reliability of the final output of semantic segmentation and image post-processing, the root mean squared error (RMSE) and R2 score were used, and the following equation were used.

where is the actual output, is the predicted output, and is the mean of , is an evaluation index that intuitively explains the model error as the average Euclidean distance between the actual and predicted outputs. R2 score is an index that shows how well independent variables explain the dependent variable in the regression model.

Finally, latency and params were used as evaluation indexes to compare the speed of each semantic-segmentation model on the embedded board. Latency is the time taken to analyze one rice-lodging image. Params is the number of parameters, such as weights and biases, used to train the model.

2.6. Experimental Environment

A DJI Mavic 2 Pro (DJI, Shenzhen, China) drone was used for aerial image shooting. The drone is equipped with a 1-inch CMOS sensor (20 MP, Hasselblad L1D-20c, Gothenburg, Sweden) and a variable aperture lens (f/2.8–f/11). The drone supports 4K video (3840 × 2160) and 20 MP still image acquisition in both JPEG and RAW formats. It provides a maximum flight time of approximately 31 min and a maximum speed of 72 km/h under calm conditions. The total takeoff weight is 907 g, and the system includes omnidirectional obstacle detection sensors.

The raw data were collected as RGB images (width = 5472 pixel and height = 3078 pixel) and downsampled to a size of 1920 × 1280 that maintained the 16:9 ratio for training. Downsampling inevitably resulted in data loss as it would be impossible to learn while maintaining a mini-batch of appropriate size if the training environment maintained the original size of the aerial image.

The computing environment used to train the semantic-segmentation model was a CPU Intel Xeon(r) 6230R 2.10GHz, memory 128 GB, GPU NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3080 2x, and the development environment was Python 3.7.7, OpenCV 4.10.0, Tensorflow 2.7.0, and Keras 2.7.0. The embedded device for the mobile end-to-end automated system was a Raspberry Pi 4 model B with an ARM Cortex-A72 1.5 GHz CPU, 4 GB LPDDR4 memory, and Broadcom VideoCore VI 500 MHz GPU, and the development environments included Python 3.9.2, OpenCV 4.10.0, Tensorflow 2.16.1, and Keras 3.3.3.

2.7. Parameter Setting for Training

A class imbalance problem was identified because the ratios of the lodging, normal, and background regions in the data were unbalanced. To solve this issue, back-propagation was used with output loss weights of 5:2:2 for lodging, normal, and background regions, reflecting their pixel ratios in the dataset.

The models were trained using the Adam algorithm, with a learning rate of 0.001 for MobileNetV1-UNet and 0.00005 for MobileNetV1-LR-ASPP, MobileNetV2-LR-ASPP, MobileNetV3-LR-ASPP (small), and MobileNetV3-LR-ASPP (large). The batch size was set to 2, and number of epochs for training was set to 200. After each training epoch, the loss and accuracy were calculated, and the weights were updated and saved. After training the model for 200 epochs, the model with the lowest validation loss was selected as the final.

To increase data efficiency, six-fold validation was performed [50]. Based on the number of data points collected by region in Table 1, fold 1 included 112 data points collected from Gyeongsangnam-do; fold 2 included 108 data points collected from Jeollanam-do and Chungcheongnam-do; folds 3 to 5 included the data collected from Jeollabuk-do (112, 112, and 111 points, respectively); and fold 6 included 143 data points collected from Chungcheongbuk-do. Thus, the number of data points for each fold was adjusted.

3. Results

3.1. Experimental Results

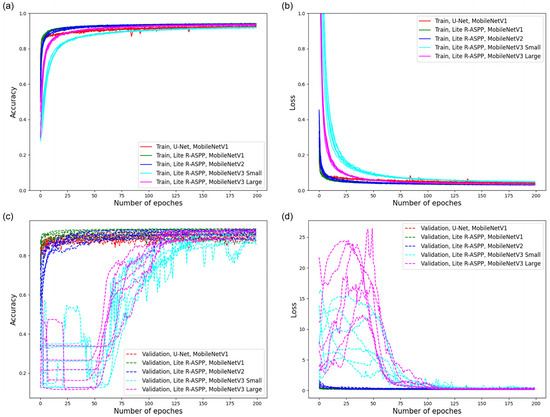

3.1.1. Rice-Lodging Recognition with Different Models

Figure 7 shows the changes in the pixel accuracy and loss function values of the training and validation sets of the five models according to the training epoch. Figure 7a,b show the changes in the pixel accuracy and loss function values of the training set, respectively. The pixel accuracy of each model improved sharply, and the loss function values decreased sharply in the early epochs. As the network training continued, the network gradually stabilized. Figure 7c,d show the changes in the pixel accuracy and loss function values, respectively, of the validation set that did not participate in the training. Unlike during training, each model exhibited distinct sections where accuracy increased, or the loss function values sharply decreased during validation. Generally, the models gradually stabilized at approximately 100 epochs, and 200 epochs was a sufficient number of repetitions for model training.

Figure 7.

Graphs depicting the changes in accuracy and loss during training and validation as the number of epochs increased. (a) the changes in the pixel accuracy values of the training set; (b) the changes in the loss function values of the training set; (c) the changes in the pixel accuracy values of the test set; (d) the changes in the loss function values of the test set.

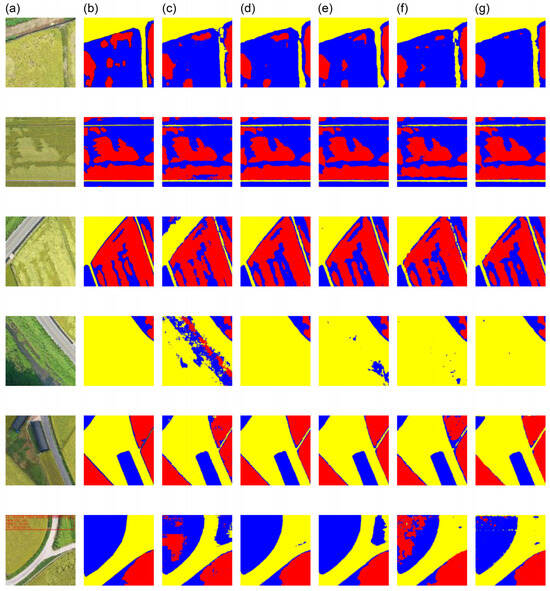

The effect of each proposed model on rice parcel segmentation was evaluated using the validation set. Figure 8 presents a visualization of the segmentation results for the validation sets of the five models. The lodged, normal, and back-ground regions were labeled using red, blue, and yellow colors, respectively. The original images, ground truth images, and the images processed by the MobileNetV1_U-Net, MobileNetV1_LR-ASPP, MobileNetV2_LR-ASPP, MobileNetV3_LR-ASPP (small), and MobileNetV3_LR-ASPP (large) models are presented. The first to third rows of Figure 8 show the results comparing whether each model classifies the normal and lodging areas well, and whether it represents the segmentation results of the ridges corresponding to the boundaries between parcels among the background areas well. During the classification of normal and lodging areas, the performances of MobileNetV1_U-Net and MobileNetV3_LR-ASPP (small) were sluggish, whereas the other models performed well. As for the parcel boundaries, the segmentation by MobileNetV2_LR-ASPP and MobileNetV3_LR-ASPP models was satisfactory. In the first row of Figure 8, where the colors of parcels and boundary are similar in light green, we can observe that the parcel boundary of MobileNetV1_U-Net, MobileNetV1_LR-ASPP, and MobileNetV3_LR-ASPP (small) have collapsed, and the left and right parcels have partially merged. For the third row of Figure 8, which has a right parcel and an unclear parcel boundary, MobileNetV1_U-Net and MobileNetV3_LR-ASPP (small) show a partially collapsed right parcel boundary. The third to fifth rows of Figure 8 show a comparison of how well each model distinguishes between artificial structures and natural elements belonging to the background category and normal and lodging areas belonging to the parcel category. In the third row of Figure 8, we observe that all models except MobileNetV1_U-Net successfully segment the background and lodging areas. For the fourth row of Figure 8, MobileNetV1_LR-ASPP and MobileNetV3_LR-ASPP (large) produced clean segmentation results, but the remaining models failed to segment the background and lodging areas well, and, in particular, MobileNetV1_U-Net showed very poor segmentation results. As shown in the fifth row of Figure 8, artificial structures such as buildings and roads are well classified as background objects in all models. The last row of Figure 8 presents the experimental results used to assess how the part of the image displaying shooting information, such as the date and height as a watermark in the upper left corner, affects the segmentation outcomes. The watermark had a negative effect on the classification results in all models except for the MobileNetV1_LR-ASPP and MobileNetV2_LR-ASPP models.

Figure 8.

Visualization of the segmentation results for the validation sets of the five models. (a) a subset of the validation set; (b) ground truth images; images processed by the (c) MobileNetV1_U-Net, (d) MobileNetV1_LR-ASPP, (e) MobileNetV2_LR-ASPP, (f) MobileNetV3_LR-ASPP (small), and (g) MobileNetV3_LR-ASPP (large) models.

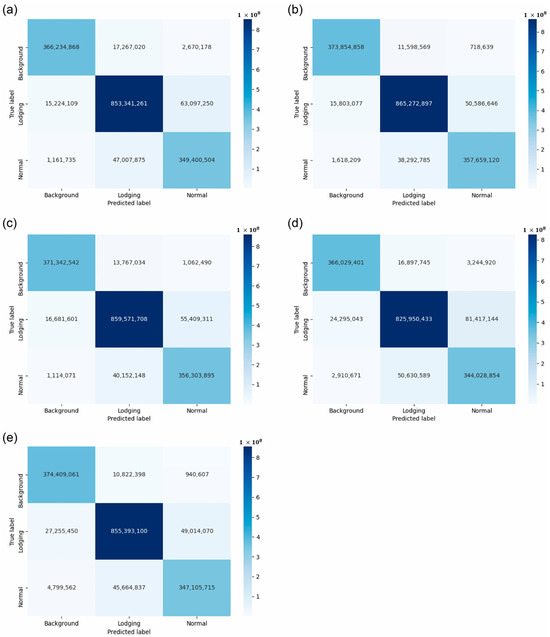

Figure 9 shows the confusion matrix results for the five models. The MobileNetV1_LR-ASPP model exhibited the highest segmentation performance in the lodging and normal areas (Figure 9b), and the MobileNetV2_LR-ASPP (large) model exhibited the highest segmentation performance in the background area (Figure 9e). The estimated precision, recall, F1-score, and IoU values that reflect the accuracies of the models are shown in Table 4. All evaluation indices were high for the MobileNetV1_LR-ASPP model except for two indices. All the evaluation indices were high for the MobileNetV1_LR-ASPP model except for two indices. The precision value for the classification in the background area was highest for the MobileNetV1_U-Net model, and the recall value for the classification in the background area was highest for the MobileNetV3_LR-ASPP (large) model. Thus, MobileNetV1_LR-ASPP was the most reliable model for evaluating the segmentation performance for all categories.

Figure 9.

Confusion matrix diagrams of (a) MobileNetV1_U-Net; (b) MobileNetV1_LR-ASPP; (c) MobileNetV2_LR-ASPP; (d) MobileNetV3_LR-ASPP (small); and (e) MobileNetV2_LR-ASPP (large) models.

Table 4.

Comprehensive evaluation of different models.

3.1.2. Image Post-Processing for Parcel Division

To determine the performance of the proposed aerial image parcel segmentation technology, the results of deep neural network segmentation and additional post-processing were evaluated and compared. A total of 698 data points were collected and labeled in advance, and deep learning was performed and evaluated using six-fold validation method by classifying them as training and validation data. Thus, the reliability of the experiment, even when using all 698 data points to evaluate the post-processing algorithm, was verified.

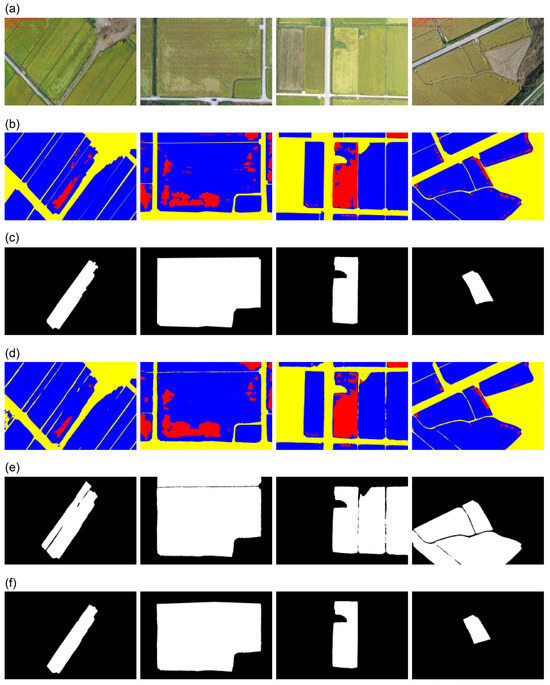

Figure 10 shows examples of image post-processing algorithm for rice-lodging fields. Figure 10a shows the original aerial images, Figure 10b shows the ground truth labeling results, Figure 10c shows the images in which the parcels of interest were extracted from the ground truth labeling results, and Figure 10d shows the deep neural network segmentation result by MobileNetV1_LR-ASPP, which showed the best performance in Table 4. Figure 10e shows the result of detecting candidate parcels from the center of the image using connected-component labeling [51] in Figure 10d. Unlike Figure 10c, due to the imperfect segmentation performance of the deep neural network segmentation, the parcel boundary collapses, and the central parcel is merged with surrounding parcels. Finally, Figure 10f shows the parcels of interest identified using the post-processing algorithm. The first column of Figure 10 shows that, compared to the original image (the first column of Figure 10a), the parcel of interest is relatively narrow, has a similar overall color to the adjacent parcel in the upper left, and the parcel boundary is difficult to distinguish with the naked eye. Consequently, the connected-component labeling result (the first column of Figure 10e) merges the parcel of interest with the adjacent parcel in the upper left. The result of applying the proposed image post-processing algorithm (the first column of Figure 10f) confirms that the parcels of interest are similar to the ground truth. The second and third columns of Figure 10 show cases where parcels are hollowed out to check whether the Hough transform applied to the image post-processing algorithm can cause problems in its principle of finding straight lines. Similarly to the first column of Figure 10, the parcels of interest in the second and third columns of Figure 10e are merged with the surrounding parcels due to the resolution of the image and unclear parcel boundaries. As a result of applying the image post-processing algorithm (the second and third columns of Figure 10f), we can see that the hollowed-out part of the parcel of interest is not affected by the image post-processing algorithm, and the parcel of interest is separated from the surrounding parcels. The fourth column of Figure 10 shows the segmentation results in a complex, unorganized land. The fourth column of Figure 10d shows that the deep neural network segmentation results performed fairly well despite the complex shapes of the parcels. However, the connected-component labeling results (the fourth column of Figure 10e) also confirm that the central parcel has been merged with adjacent parcels. However, the image post-processing algorithm results confirm that all parcels except the parcel of interest have been cleanly removed.

Figure 10.

Detailed outcomes of each step in the post-processing experiment. (a) Land images captured by a drone; (b) the labeling results of the land image (red and blue areas are the parcels, and yellow areas are terrain regions outside the parcels, including roads, parcel boundaries, and buildings); (c) ground truth images of the parcels; (d) deep learning segmentation results of MobileNetV1_LR-ASPP; (e) the result of extracting parcels of interest using connected-component labeling from deep learning segmentation results; (f) image post-processing results for the parcels.

We used OA and mIoU as evaluation indices to compare the deep learning results for each model with the results of the image post-processing algorithm (Table 5). Among the deep learning results, the MobileNetV1_U-Net and MobileNetV1_LR-ASPP models exhibited the highest OA and mIoU values, respectively. For image post-processing, the MobileNetV1_LR-ASPP model showed the best results in terms of both OA and mIoU. The OA for deep learning exceeded 0.9 only for very few models; however, the OA of all models improved to over 0.98 for image post-processing; similarly, mIoU also did not exceed 0.9 for any of the models for deep learning, but the corresponding values of all models improved to over 0.9 for image post-processing.

Table 5.

Evaluation indices for all models for deep learning and image post-processing.

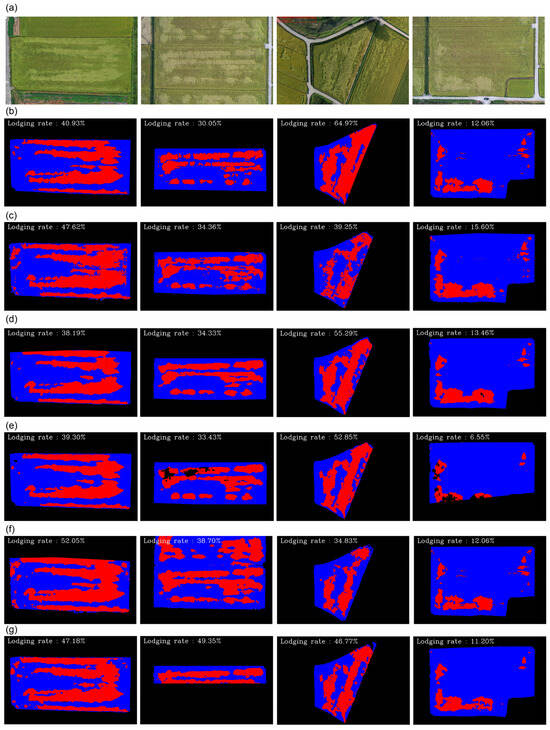

3.1.3. Fully Automated Calculation of Rice-Lodging Within a Parcel

Table 6 presents the RMSE values and R2 scores for rice-lodging ratio calculation within the parcel using a fully automated method for each model. The MobileNetV1_U-Net model showed the best result, with the lowest RMSE of 11.75 and highest R2 score of 0.875. Figure 11 shows the lodging occurrence rates calculated within a parcel by removing the background area and leaving only the lodging and normal areas. Lodged in parcel of interest, normal in parcel of interest, and other regions were labeled using red, blue, and black colors, respectively. Despite the satisfactory results, outliers were observed in some cases. Figure 11a shows the original aerial photographed image, and Figure 11b shows the ground truth image for calculating the lodging occurrence rate within a parcel. Figure 11c–g show the calculated lodging occurrence rates within the parcel using the models MobileNetV1_U-Net, MobileNetV1_LR-ASPP, MobileNetV2_LR-ASPP, MobileNetV3_LR-ASPP (small), and MobileNetV3_LR-ASPP (large), respectively. The calculated rates of lodging within the field are shown in the upper left corners of Figure 11b–g.

Table 6.

Evaluation indices for the calculated lodging occurrence rates.

Figure 11.

Calculation of the lodging occurrence rates within a parcel. (a) Land images captured by a drone; (b) ground truth images; and the results from (c) MobileNetV1_U-Net, (d) MobileNetV1_LR-ASPP, (e) MobileNetV2_LR-ASPP, (f) MobileNetV3_LR-ASPP (small), and (g) MobileNetV3_LR-ASPP (large) models.

The first column of Figure 11 shows parcels with a typical rectangular shape; all models performed parcel detection well, and the MobileNetV2_LR-ASPP model (Figure 11e) exhibited the highest accuracy. The second column of Figure 11 shows parcels of the same rectangular shape but with different segmentation results depending on the model. The MobileNetV2_LR-ASPP model (Figure 11e) had many parts (black) that were evaluated as not being part of the parcels, and the MobileNetV3_LR-ASPP (large) model (Figure 11g) exhibited an error in dividing the parcels because the image post-processing algorithm mistook parts that were not parcel boundaries as parcel boundaries for the same reason. In contrast, the MobileNetV3_LR-ASPP (small) model (Figure 11f) failed to divide the parcel boundaries clearly, and the results merged with the adjacent parcels. The third column of Figure 11 shows parcels with irregular shapes, and all models divide the parcel boundaries well. However, the shadow of the tree cast at 1 o’clock in the center of the picture interferes with the segmentation, and the upper right corner of the parcel was cut off when analyzed by most models. The fourth column in Figure 11 represents a parcel shape with a wavy bottom right corner in a rectangle. Most models identified the parcel boundary well and produced good analysis results. However, the MobileNetV2_LR-ASPP model (Figure 11e) indicated that the parcel was not within the parcel, and an error was introduced by the post-processing algorithm, resulting in an incorrect parcel boundary based on the wavy boundary.

3.1.4. Measurement in Mobile Environment

To determine the mobile operation potential of the developed methodology, we compared the required number of parameters for each of the five models and measured the corresponding latency value, which is the processing time per image, on the embedded board, Raspberry Pi 4. Table 7 presents the results for the number of parameters recorded for each model. The MobileNetV1_U-Net model with the U-Net structure had an overwhelmingly larger number of parameters than other models. All five models were trained six times by appropriate data modification for six-fold validation. Table 8 presents the average latency values for all five models. All five models were loaded on the CPU of the Raspberry Pi 4, and the analysis results were produced on the embedded board. Table 8 presents the latency values of all models in the embedded environment. Among the five models, the MobileNetV3_LR-ASPP (small) model had the shortest processing time of 4.9844 s.

Table 7.

Number of parameters for different models.

Table 8.

Data processing speed on an embedded board.

4. Discussion

This study proposed a fully automated, end-to-end rice lodging analysis framework that integrates lightweight deep-learning segmentation and an image post-processing algorithm to objectively quantify lodging occurrence within a parcel. In an embedded-board environment, drone-captured images were segmented into rice-lodging, normal-rice, and background areas using a deep learning–semantic-segmentation method. Subsequently, based on the segmentation information, only the target parcels were precisely detected from the entire image using an image post-processing method, and the rice-lodging rate within the parcel was derived. We collected 698 data points by capturing aerial images of farmlands in Jeolla-do, Gyeongsang-do, and Chungcheong-do for two years from 2020 to 2021 and labeled them for the experiment. To increase data efficiency, six-fold validation was performed, as performed, and the number of data points per fold was adjusted to minimize the mixing of data from different regions within each fold. Five models were trained based on the U-Net and LR-ASPP structure models with MobileNet versions 1–3 as the backbones: MobileNetV1_U-Net, MobileNetV1_LR-ASPP, MobileNetV2_LR-ASPP, MobileNetV3_LR-ASPP (small), and MobileNetV3_LR-ASPP (large). The U-Net segmentation head structure was applied exclusively to MobileNetV1, as experiments demonstrated that convergence failed to occur when applied to MobileNetV2 and MobileNetV3 owing to their structural characteristics.

The developed system demonstrated high accuracy and stability under real-world field conditions, providing scientific and practical contributions to precision agriculture in three key aspects. First, to ensure a end-to-end interpretation on the embedded board, we explored the most suitable mobile model for rice-lodging segmentation by training the U-Net [20] and LR-ASPP [23] models using the four versions of MobileNet, namely, the first version [21], second version [22], and the small and large forms of the third version [23], as backbone networks. Second, this study addressed the problem of boundary collapse between parcels that may occur owing to image resolution issues through image post-processing to detect accurate target parcels. Third, we verified the possibility of a mobile end-to-end automated system by operating the segmentation algorithm in an embedded-board environment.

4.1. Comparison of Semantic-Segmentation Models

All five semantic-segmentation models were trained for 200 epochs with six-fold cross-validation, and the model exhibiting the lowest validation loss in each fold was selected as the final model. Figure 8 shows that all models effectively identified both lodging and non-lodging areas, although their performance varied with illumination and background complexity. Among the deep-learning models, the MobileNetV1_LR-ASPP achieved the highest segmentation performance, with an overall accuracy (OA) of 0.9176 and an mIoU of 0.8134, followed by MobileNetV2_LR-ASPP (mIoU = 0.7695) and MobileNetV1_U-Net (mIoU = 0.7660). The LR-ASPP module enhanced feature extraction and spatial consistency through atrous convolution and skip connections, resulting in improved delineation of lodging boundaries compared with the conventional U-Net structure.

When compared with previous studies, the performance of the proposed model is comparable to or exceeds that of existing lightweight architectures. Yang et al. [19] developed a Mobile U-Net model for wheat lodging detection using RGB and DSM fusion data, reporting an F1-score of 88.99% and an mIoU of 80.70%. The model in that study adopted a similar lightweight convolutional structure but relied on digital surface model (DSM) data to compensate for spectral limitations in RGB imagery. In contrast, our MobileNetV1_LR-ASPP model achieved a comparable mIoU (0.8134) using only RGB inputs, demonstrating that efficient feature extraction through the LR-ASPP architecture can achieve similar spatial segmentation performance without the need for additional DSM information. These results confirm that the proposed lightweight segmentation framework ensures high accuracy and robustness under variable field conditions while maintaining computational efficiency suitable for real-time or onboard applications in precision agriculture.

4.2. Analysis of Image Post-Processing Results

The image post-processing algorithm significantly improved the accuracy and spatial consistency of all models. As shown in Table 5, the OA of each model increased from approximately 0.89–0.92 to over 0.98, while the mIoU rose by more than 0.15 after applying post-processing. The most substantial improvement was observed in the MobileNetV1_LR-ASPP model, whose mIoU increased from 0.8134 to 0.9663. This confirms that the proposed geometric refinement process effectively restored parcel boundaries and eliminated the fragmented edges commonly observed in deep-learning outputs. The superior performance of the proposed method can be attributed to its combination of semantic segmentation and mathematical image refinement. The LR-ASPP architecture provided multi-scale contextual features, while the post-processing algorithm corrected residual misclassifications at parcel boundaries using structural geometry and shape continuity. As a result, the model achieved both high segmentation precision and strong spatial coherence within and across crop parcels. When compared with previous studies, the performance enhancement achieved through post-processing is noteworthy.

However, concerns remain about the inaccurate segmentation of post-processing algorithms for irregular boundaries. In South Korea, the mechanization rate of modern rice farming is 99.3%, a result of the high rate of land consolidation. Of the 698 datasets used in the paper, 41, or 5.87%, have curved boundaries. These data are either unconsolidated land or, even if consolidated, are adjacent to roads. Outlying parcels are not considered candidates for post-processing by the segmentation algorithm, and even for unconsolidated parcels, extreme boundary formation is impossible for mechanized rice farming. Therefore, the possibility of problems arising from the geometric post-processing algorithms associated with high-performance segmentation algorithms is very low.

Su et al. [4] proposed LodgeNet, a DenseNet-based semantic segmentation framework that incorporated attention and dilated convolutions, achieving an F1-score of approximately 0.94, an overall accuracy of 0.9532, and an mIoU of 0.9009 using multispectral UAV imagery. Despite relying solely on RGB images, the MobileNetV1_LR-ASPP model in this study achieved an mIoU of 0.9663 after post-processing. This demonstrates that integrating a mathematical correction mechanism can compensate for spectral limitations and outperform more complex multispectral models.

Moreover, the algorithm’s improvement is not limited to overall accuracy; it also enhances objectivity and reproducibility by removing observer bias from manual boundary delineation. The consistent enhancement across multiple model backbones (MobileNetV1, V2, and V3) further confirms that the post-processing framework is model-agnostic and robust to varying network architectures. In summary, the image post-processing stage plays a crucial role in bridging the gap between deep-learning predictions and field-level interpretability. By refining the segmentation boundaries through geometric correction, the proposed system provides an objective, reproducible, and scalable approach for lodging assessment in precision agriculture.

4.3. Fully Automated End-to-End Rice-Lodging Analysis System

The proposed framework was developed as a fully automated end-to-end rice-lodging analysis system integrating lightweight deep-learning segmentation, geometric post-processing, and secure data management. Once UAV imagery is acquired and orthorectified, the system automatically performs segmentation and parcel-level lodging quantification without any manual intervention. This end-to-end automation ensures that the analysis process remains objective, reproducible, and free from operator bias.

Although the same image post-processing algorithm was applied to all segmentation models, MobileNetV1_LR-ASRP performed best in segmentation (Table 4), while MobileNetV1_U-Net performed best in final lodging calculation (Table 6). This suggests that better pixel-level segmentation does not necessarily translate into better end-to-end system performance. Whether this is a limitation of the currently available data or a general phenomenon requires further investigation through extended experiments.

To evaluate the computational efficiency of the proposed models, the number of trainable parameters was used as an architecture-independent indicator of model complexity. As summarized in Table 7, the MobileNetV1_U-Net model contained 11.05 million parameters, comparable to Yang et al.’s [19] Mobile U-Net (9.49 million) while yielding higher predictive accuracy. More notably, the MobileNetV1_LR-ASPP model required only 1.76 million parameters, representing an 81% reduction compared with Yang et al. [19] and a 93% reduction compared with Su et al. [4] (24.39 million parameters). Despite this significant reduction in model size, the LR-ASPP structure achieved similar or higher segmentation accuracy, demonstrating superior parameter efficiency and scalability for real-time agricultural applications.

The end-to-end architecture also enhances security and transparency across the entire workflow. Analytical outputs are automatically encrypted and transmitted to a local or remote database, preventing intermediate manipulation and ensuring that all stakeholders receive identical and verifiable results. This closed-loop mechanism supports objective and standardized lodging assessments, which are essential for policy-driven applications such as government disaster compensation, agricultural insurance evaluation, and large-scale lodging monitoring.

5. Conclusions

This study proposed a fully automated end-to-end rice-lodging analysis system that integrates lightweight deep-learning segmentation and an image post-processing algorithm to achieve objective and reproducible lodging quantification at the parcel level. A total of 698 aerial images collected from rice fields across Jeolla-do, Gyeongsang-do, and Chungcheong-do from 2020 to 2021 were used to train and validate the proposed models under real field conditions. The experimental results confirmed that the MobileNetV1_LR-ASPP model provided the most effective balance between accuracy and computational efficiency among the five tested architectures. The model achieved a mIoU of 0.8134 before and 0.9663 after image post-processing, demonstrating that the proposed geometric correction method effectively refined parcel boundaries and eliminated spatial inconsistencies. Compared with previous studies, the proposed model achieved comparable or higher segmentation performance while requiring only 1.76 million parameters, corresponding to an approximate 93% reduction in model complexity compared with similar studies on lodging detection using larger backbone networks.

These findings demonstrate that the proposed framework can achieve high segmentation accuracy and computational efficiency simultaneously, even when operating on lightweight embedded hardware. The system’s end-to-end automated design ensures objectivity, security, and transparency by automatically encrypting and transmitting results, enabling its application to governmental damage assessment, agricultural insurance compensation, and large-scale monitoring systems. Future research will focus on expanding the model’s generalizability by incorporating additional environmental conditions and multi-year datasets. Furthermore, integration with real-time UAV control systems and on-device inference optimization will be pursued to establish a practical foundation for next-generation smart-farming applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.J., H.K., H.-G.A. and K.P.; software, S.J. and K.P.; validation, S.K., D.K., K.S.P. and K.P.; formal analysis, J.C. and S.K.; investigation, H.K., K.S.P. and K.P.; resources, S.J., J.C., S.K., D.K. and K.P.; data curation, S.J., S.K., D.K. and H.-G.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.J., J.C. and K.P.; writing—review and editing, S.J., J.C. and K.P.; visualization, K.P.; supervision, K.P.; project administration, K.P.; funding acquisition, H.K. and K.S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture, and Forestry (IPET) and the Korea Smart Farm R&D Foundation (KosFarm) through the Smart Farm Innovation Technology Development Program, funded by the Ministry of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Affairs (MAFRA) and the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT), Rural Development Administration (RDA) (RS-2025-02315577).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to a lack of access to an online database, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Specifications for MobileNetV1-UNet.

Table A1.

Specifications for MobileNetV1-UNet.

| Name | Input Size | Operator | s | Output Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conv2D | 1920 × 1280 × 3 | Convolution 2D | 2 | 960 × 640 × 32 |

| DSConv1 | 960 × 640 × 32 | Depthwise separable convolution | 1 | 960 × 640 × 64 |

| DSConv2 | 960 × 640 × 64 | Depthwise separable convolution | 2 | 480 × 320 × 128 |

| DSConv3 | 480 × 320 × 128 | Depthwise separable convolution | 1 | 480 × 320 × 128 |

| DSConv4 | 480 × 320 × 128 | Depthwise separable convolution | 2 | 240 × 160 × 256 |

| DSConv5 | 240 × 160 × 256 | Depthwise separable convolution | 1 | 240 × 160 × 256 |

| DSConv6 | 240 × 160 × 256 | Depthwise separable convolution | 2 | 120 × 80 × 512 |

| DSConv7~11 | 120 × 80 × 512 | Depthwise separable convolution | 1 | 120 × 80 × 512 |

| DSConv12 | 120 × 80 × 512 | Depthwise separable convolution | 2 | 60 × 40 × 1024 |

| DSConv13 | 60 × 40 × 1024 | Depthwise separable convolution | 1 | 60 × 40 × 1024 |

| TConv1 | 60 × 40 × 1024 | Transposed Convolution | 2 | 120 × 80 × 512 |

| Concat1 | 120 × 80 × 512 × 2 | Concatenate (DSConv11, TConv1) | - | 120 × 80 × 1024 |

| TConv2 | 120 × 80 × 1024 | Transposed Convolution | 2 | 240 × 160 × 256 |

| Concat2 | 240 × 160 × 256 × 2 | Concatenate (DSConv5, TConv2) | - | 240 × 160 × 512 |

| TConv3 | 240 × 160 × 512 | Transposed Convolution | 2 | 480 × 320 × 128 |

| Concat3 | 480 × 320 × 128 × 2 | Concatenate (DSConv3, TConv3) | - | 480 × 320 × 256 |

| TConv4 | 480 × 320 × 256 | Transposed Convolution | 2 | 960 × 640 × 64 |

| Concat4 | 960 × 640 × 64 × 2 | Concatenate (DSConv1, TConv4) | - | 960 × 640 × 128 |

| TConv5 | 960 × 640 × 128 | Transposed Convolution | 2 | 1920 × 1280 × 3 |

s is the stride size.

Table A2.

Specifications for MobileNetV1-LR-ASPP.

Table A2.

Specifications for MobileNetV1-LR-ASPP.

| Name | Input Size | Operator | s | Output Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conv2D | 1920 × 1280 × 3 | Convolution 2D | 2 | 960 × 640 × 32 |

| DSConv1 | 960 × 640 × 32 | Depthwise separable convolution | 1 | 960 × 640 × 64 |

| DSConv2 | 960 × 640 × 64 | Depthwise separable convolution | 2 | 480 × 320 × 128 |

| DSConv3 | 480 × 320 × 128 | Depthwise separable convolution | 1 | 480 × 320 × 128 |

| DSConv4 | 480 × 320 × 128 | Depthwise separable convolution | 2 | 240 × 160 × 256 |

| DSConv5 | 240 × 160 × 256 | Depthwise separable convolution | 1 | 240 × 160 × 256 |

| DSConv6 | 240 × 160 × 256 | Depthwise separable convolution | 2 | 120 × 80 × 512 |

| DSConv7~11 | 120 × 80 × 512 | Depthwise separable convolution | 1 | 120 × 80 × 512 |

| Branch1 | 120 × 80 × 512 | Convolution 2D (DSConv11) | 1 | 120 × 80 × 128 |

| Branch2_1 | 120 × 80 × 512 | Average Pooling 2D (DSConv11) | 16, 20 | 4 × 2 × 512 |

| Branch2_2 | 4 × 2 × 512 | Convolution 2D | 1 | 4 × 2 × 128 |

| Branch2_3 | 4 × 2 × 128 | Resize (120 × 80) | - | 120 × 80 × 128 |

| Branch3 | 240 × 160 × 256 | Convolution 2D (DSConv5) | 1 | 240 × 160 × 3 |

| Merge1_1 | 120 × 80 × 128 × 2 | Multiply (Branch1, Branch2_3) | - | 120 × 80 × 128 |

| Merge1_2 | 120 × 80 × 128 | Resize (240 × 160) | - | 240 × 160 × 128 |

| Merge1_3 | 240 × 160 × 128 | Convolution 2D | 1 | 240 × 160 × 3 |

| Merge2_1 | 240 × 160 × 3×2 | Add (Branch3, Merge1_3) | - | 240 × 160 × 3 |

| Merge2_2 | 240 × 160 × 3 | Resize (1920 × 1280) | - | 1920 × 1280 × 3 |

Table A3.

Specifications for MobileNetV2-LR-ASPP.

Table A3.

Specifications for MobileNetV2-LR-ASPP.

| Name | Input Size | Operator | s | exp | Output Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conv2D | 1920 × 1280 × 3 | Convolution 2D | 2 | - | 960 × 640 × 32 |

| IR0 | 960 × 640 × 32 | Inverted residual | 1 | 1(32) | 960 × 640 × 16 |

| IR1 | 960 × 640 × 16 | Inverted residual | 2 | 6(96) | 480 × 320 × 24 |

| IR2 | 480 × 320 × 24 | Inverted residual | 1 | 6(144) | 480 × 320 × 24 |

| IR3 | 480 × 320 × 24 | Inverted residual | 2 | 6(144) | 240 × 160 × 32 |

| IR4~5 | 240 × 160 × 32 | Inverted residual | 1 | 6(192) | 240 × 160 × 32 |

| IR6 | 240 × 160 × 32 | Inverted residual | 2 | 6(192) | 120 × 80 × 64 |

| IR7~9 | 120 × 80 × 64 | Inverted residual | 1 | 6(384) | 120 × 80 × 64 |

| IR10 | 120 × 80 × 64 | Inverted residual | 1 | 6(384) | 120 × 80 × 96 |

| IR11~12 | 120 × 80 × 96 | Inverted residual | 1 | 6(576) | 120 × 80 × 96 |

| Branch1 | 120 × 80 × 96 | Convolution 2D (IR12) | 1 | - | 120 × 80 × 128 |

| Branch2_1 | 120 × 80 × 96 | Average Pooling 2D (IR12) | 16, 20 | - | 4 × 2 × 96 |

| Branch2_2 | 4 × 2 × 96 | Convolution 2D | 1 | - | 4 × 2 × 128 |

| Branch2_3 | 4 × 2 × 128 | Resize (120 × 80) | - | - | 120 × 80 × 128 |

| Branch3 | 240 × 160 × 32 | Convolution 2D (IR5) | 1 | - | 240 × 160 × 3 |

| Merge1_1 | 120 × 80 × 128 × 2 | Multiply (Branch1, Branch2_3) | - | - | 120 × 80 × 128 |

| Merge1_2 | 120 × 80 × 128 | Resize (240 × 160) | - | - | 240 × 160 × 128 |

| Merge1_3 | 240 × 160 × 128 | Convolution 2D | 1 | - | 240 × 160 × 3 |

| Merge2_1 | 240 × 160 × 3×2 | Add (Branch3, Merge1_3) | - | - | 240 × 160 × 3 |

| Merge2_2 | 240 × 160 × 3 | Resize (1920 × 1280) | - | - | 1920 × 1280 × 3 |

exp is the expansion rate.

Table A4.

Specifications for MobileNetV3-LR-ASPP (small).

Table A4.

Specifications for MobileNetV3-LR-ASPP (small).

| Name | Input Size | Operator | s | exp | SE | NL | Output Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conv2D | 1920 × 1280 × 3 | Convolution 2D | 2 | - | - | HS | 960 × 640 × 16 |

| IR0 | 960 × 640 × 16 | Inverted residual | 2 | 1(16) | √ | RE | 480 × 320 × 16 |

| IR1 | 480 × 320 × 16 | Inverted residual | 2 | 4.5(72) | - | RE | 240 × 160 × 24 |

| IR2 | 240 × 160 × 24 | Inverted residual | 1 | 3.66(88) | - | RE | 240 × 160 × 24 |

| IR3 | 240 × 160 × 24 | Inverted residual | 2 | 4(96) | √ | HS | 120 × 80 × 40 |

| IR4~5 | 120 × 80 × 40 | Inverted residual | 1 | 6(240) | √ | HS | 120 × 80 × 40 |

| IR6 | 120 × 80 × 40 | Inverted residual | 1 | 3(120) | √ | HS | 120 × 80 × 48 |

| IR7 | 120 × 80 × 48 | Inverted residual | 1 | 3(144) | √ | HS | 120 × 80 × 48 |

| Branch1 | 120 × 80 × 48 | Convolution 2D (IR7) | 1 | - | - | RE | 120 × 80 × 128 |

| Branch2_1 | 120 × 80 × 48 | Average Pooling 2D (IR7) | 16, 20 | - | - | - | 4 × 2 × 48 |

| Branch2_2 | 4 × 2 × 48 | Convolution 2D | 1 | - | - | S | 4 × 2 × 128 |

| Branch2_3 | 4 × 2 × 128 | Resize (120 × 80) | - | - | - | - | 240 × 160 × 128 |

| Branch3 | 240 × 160 × 24 | Convolution 2D (IR2) | 1 | - | - | - | 240 × 160 × 3 |

| Merge1_1 | 120 × 80 × 128 × 2 | Multiply (Branch1, Branch2_3) | - | - | - | - | 120 × 80 × 128 |

| Merge1_2 | 120 × 80 × 128 | Resize (240 × 160) | - | - | - | - | 240 × 160 × 128 |

| Merge1_3 | 240 × 160 × 128 | Convolution 2D | 1 | - | - | - | 240 × 160 × 3 |

| Merge2_1 | 240 × 160 × 3×2 | Add (Branch3, Merge1_3) | - | - | - | - | 240 × 160 × 3 |

| Merge2_2 | 240 × 160 × 3 | Resize (1920 × 1280) | - | - | - | S | 1920 × 1280 × 3 |

SE indicates whether the squeeze and excitation were performed within a block, NL indicates the type of nonlinearity, HS indicates hard sigmoid activation function, RE indicates rectified linear unit activation function, S indicates sigmoid activation function, and √ indicates it was used.

Table A5.

Specifications for MobileNetV3-LR-ASPP (large).

Table A5.

Specifications for MobileNetV3-LR-ASPP (large).

| Name | Input Size | Operator | s | exp | SE | NL | Output Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conv2D | 1920 × 1280 × 3 | Convolution 2D | 2 | - | - | HS | 960 × 640 × 16 |

| IR0 | 960 × 640 × 16 | Inverted residual | 1 | 1(16) | - | RE | 960 × 640 × 16 |

| IR1 | 960 × 640 × 16 | Inverted residual | 2 | 4(64) | - | RE | 480 × 320 × 24 |

| IR2 | 480 × 320 × 24 | Inverted residual | 1 | 3(72) | - | RE | 480 × 320 × 24 |

| IR3 | 480 × 320 × 24 | Inverted residual | 2 | 3(72) | √ | RE | 240 × 160 × 40 |

| IR4~5 | 240 × 160 × 40 | Inverted residual | 1 | 3(120) | √ | RE | 240 × 160 × 40 |

| IR6 | 240 × 160 × 40 | Inverted residual | 2 | 6(240) | - | HS | 120 × 80 × 80 |

| IR7 | 120 × 80 × 80 | Inverted residual | 1 | 2.5(200) | - | HS | 120 × 80 × 80 |

| IR8~9 | 120 × 80 × 80 | Inverted residual | 1 | 2.3(184) | - | HS | 120 × 80 × 80 |

| IR10 | 120 × 80 × 80 | Inverted residual | 1 | 6(480) | √ | HS | 120 × 80 × 112 |