Online Prototype Angular Balanced Self-Distillation for Non-Ideal Annotation in Remote Sensing Image Segmentation

Highlights

- The Online Prototype Angular Balanced Self-Distillation (OPAB) framework enhances remote sensing semantic segmentation performance under non-ideal annotation conditions, reaching 2.0% mIoU improve.

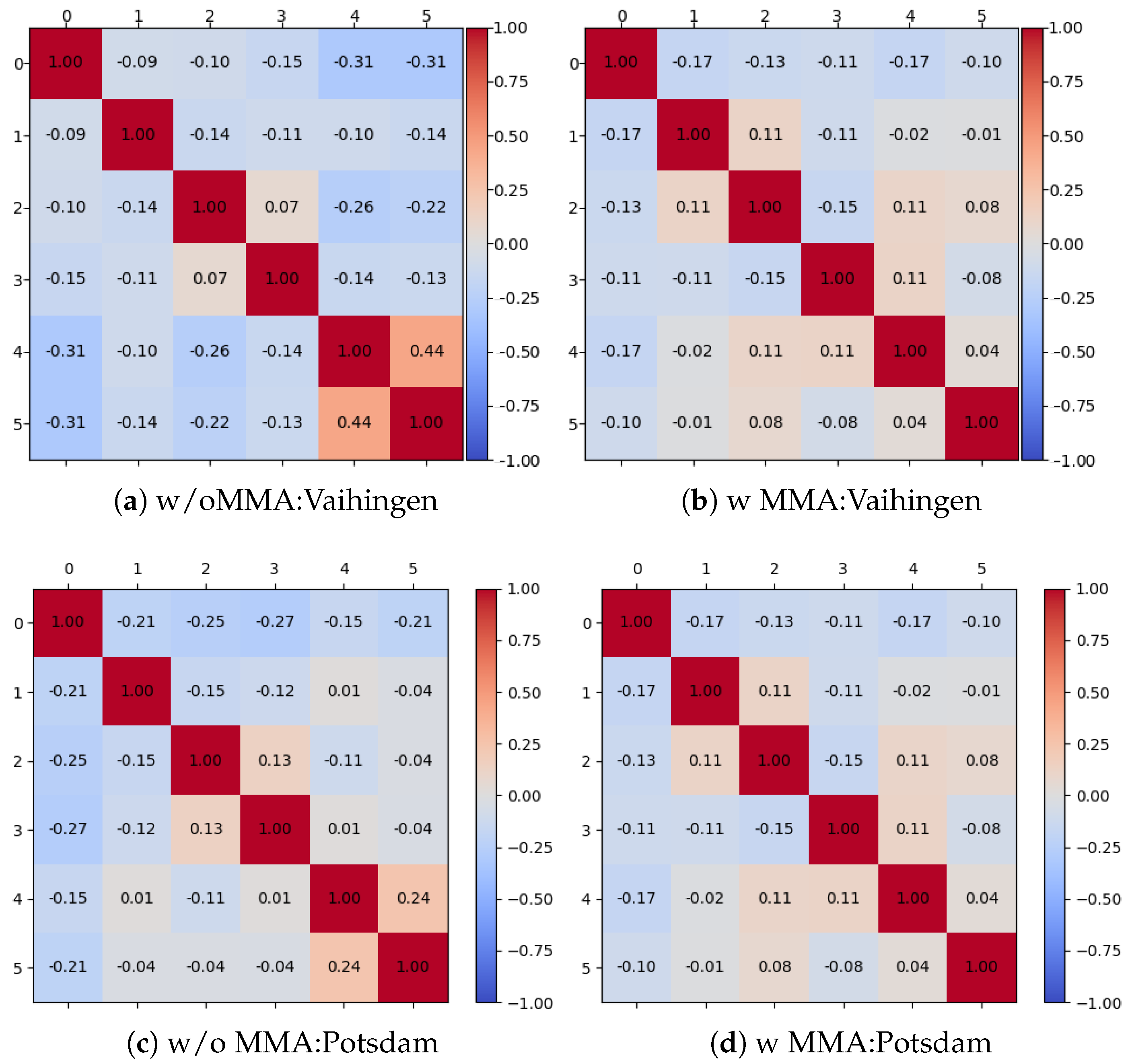

- The Bilateral-Branch Network (BBN) strategy with a cosine classifier and MMA regularization build an angular balance representation.

- Stable convergence in label count is observed during OPAB multi-round calibration, ensuring consistent performance.

- We propose an improved approach to address non-ideal data in remote sensing semantic segmentation, which enhances model generalization.

- Our modified BBN procedure prevents the performance degradation typically associated with integrating a cosine classifier into an existing code framework.

- We provide a tool for erroneous label detection and correction. It operates by monitoring the sub-class Local Intrinsic Dimensionality (LID), thereby preventing representation over-compression and the assimilation of erroneous labels in noisy settings.

Abstract

1. Introduction

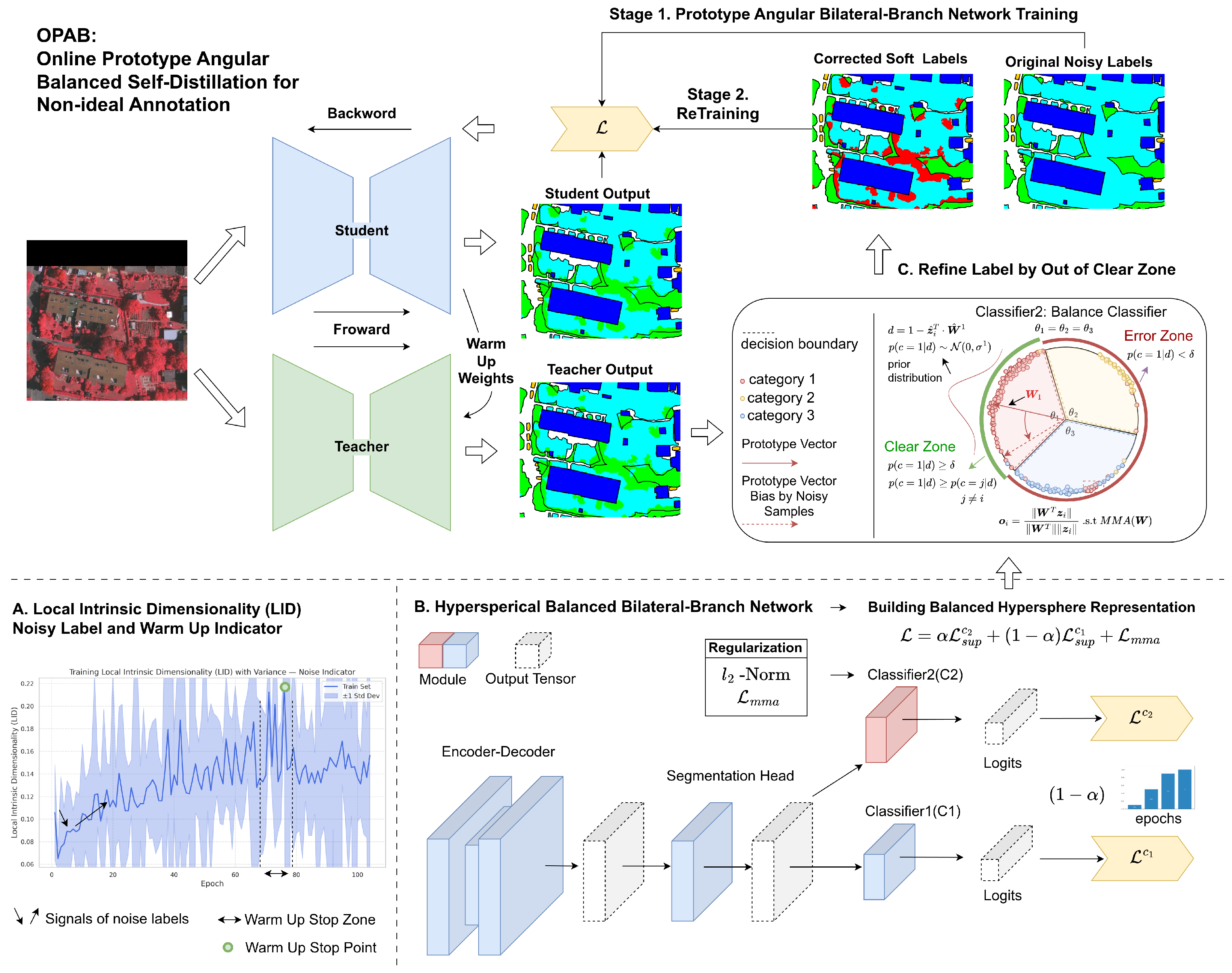

- We propose a unified teacher-student framework that leverages geometric and manifold learning principles to simultaneously handle both long-tailed distributions and noisy labels.

- We introduce balanced hyperspherical representations regularized by a Maximizing Minimal Angles (MMA) objective, along with category-level Local Intrinsic Dimensionality (LID) monitoring. This design enhances inter-class separability and enables effective detection of label noise, without reliance on potentially contaminated validation metrics.

- We develop a stopping criterion based on category-level LID trends to prevent noise memorization. By tracking changes in local manifold structure, our method overcomes the limitations of validation-loss-based stopping strategies.

- Extensive experiments on benchmark datasets demonstrate consistent performance gains. The proposed approach achieves an average improvement of 2.0% in mIoU across varying noise levels and class distributions, while showing notable robustness against representation collapse in tail classes.

2. Related Work

2.1. Long-Tailed Semantic Segmentation

2.2. Noisy Label Learning in Remote Sensing Segmentation

3. Methods

3.1. Semantic Segmentation Framework Design Based on a Bilateral-Branch Network

3.2. Balanced Hyperspherical Representations and Max-Min Angular Regularization

3.3. Label Correction via Hyperspherical Angular Bisectors

3.4. Warm Up Strategy

3.5. Two-Stage Training Procedure

| Algorithm 1 Online Prototype Angular Balanced Self-Distillation |

|

4. Experimental Setup

4.1. Datasets and Implementation Details

4.2. Evaluation Metrics and Implementation Details

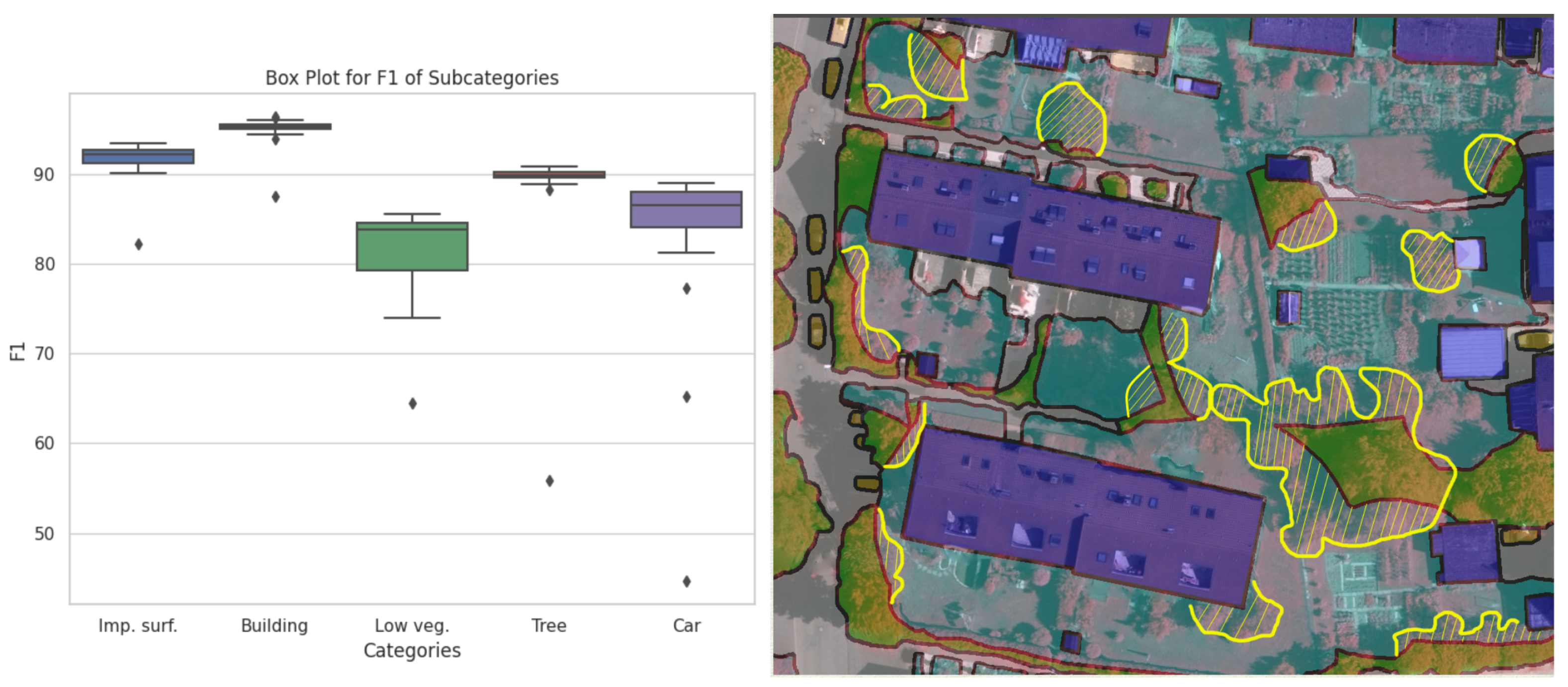

5. Results and Analysis

5.1. Results on ISPRS Dataset with OPAB Framework

5.2. Ablation

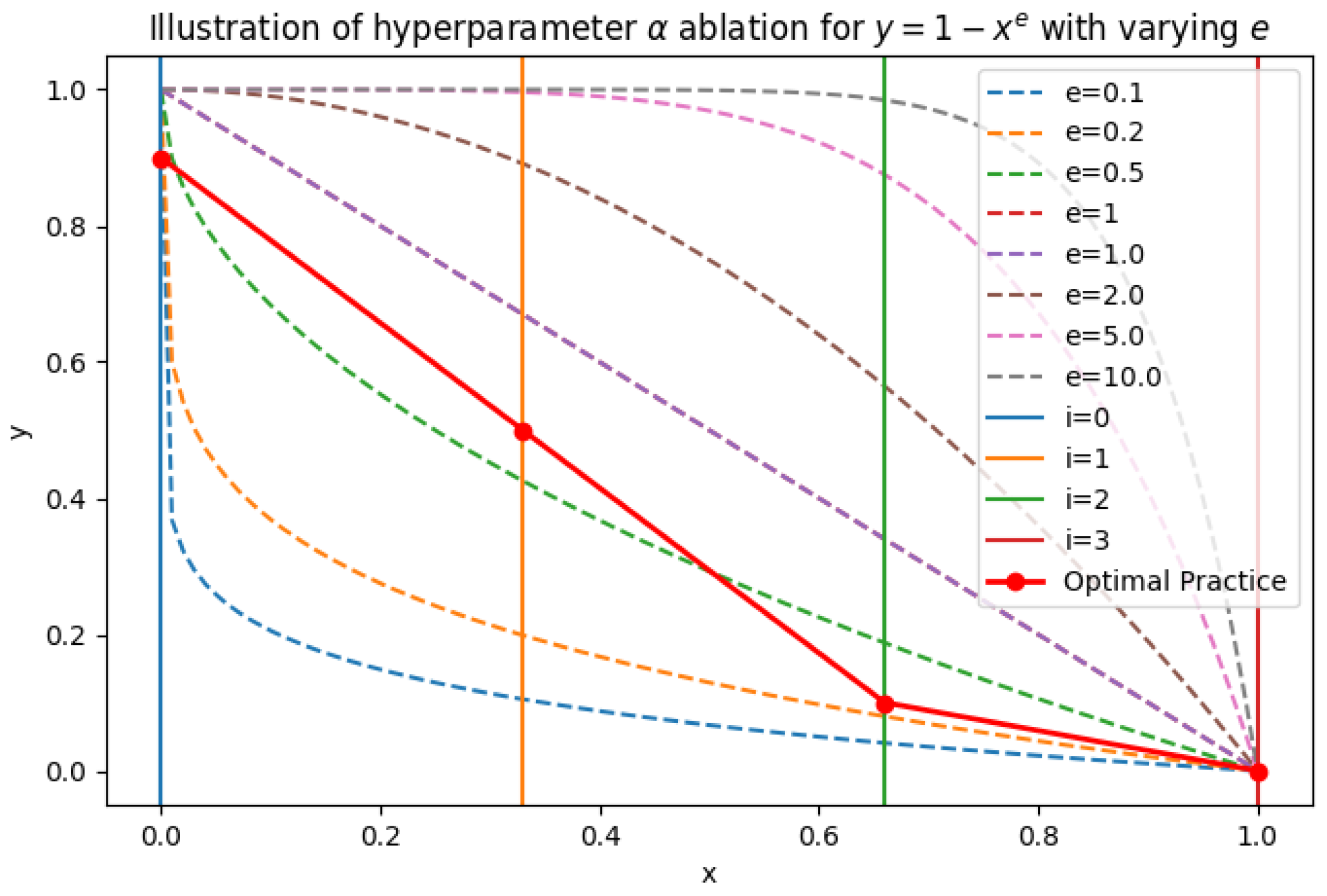

5.3. Hyperparameter Analysis

5.4. Category-Wise LID Dynamics Under Symmetric Noise Levels

5.5. Loss Curves Analysis

5.6. T-SNE Visualization

5.7. Results on Comparative on Cross-Method Comparison Under Non-Ideal Annotation

5.8. Results on (Online) Iteratively Calibration

6. Discussion

6.1. Computational Complexity and Overhead Analysis

6.2. Training Time and Efficiency Considerations

6.3. Limitations and Future Work

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pacheco-Prado, D.; Bravo-López, E.; Martínez, E.; Ruiz, L.Á. Urban Tree Species Identification Based on Crown RGB Point Clouds Using Random Forest and PointNet. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Lin, Z.; Shi, T.; Deng, D.; Chen, Y.; Pan, X.; Chen, X.; Wu, T.; Lei, J.; Li, Y. Advancing Forest Inventory in Tropical Rainforests: A Multi-Source LiDAR Approach for Accurate 3D Tree Modeling and Volume Estimation. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Zhang, X.; Halik, Ü. The Driving Mechanism and Spatio-Temporal Nonstationarity of Oasis Urban Green Landscape Pattern Changes in Urumqi. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, E.O.; Kavzoglu, T. DeepSwinLite: A Swin Transformer-Based Light Deep Learning Model for Building Extraction Using VHR Aerial Imagery. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, G.; Antonio, J.; Lazzeri, G.; Tapete, D. Airborne and Spaceborne Hyperspectral Remote Sensing in Urban Areas: Methods, Applications, and Trends. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Yoon, D.; Kim, S.; Jeon, M. N Segment: Label-specific Deformations for Remote Sensing Image Segmentation. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2025, 22, 8003405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Sun, K.; Li, W.; Li, W.; Gao, S.; Miao, S.; Tan, Y.; Gui, W.; Duan, Y. Cross-Visual Style Change Detection for Remote Sensing Images via Representation Consistency Deep Supervised Learning. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Shu, X.; Wu, S.; Ding, S. Semi-Supervised Change Detection with Data Augmentation and Adaptive Thresholding for High-Resolution Remote Sensing Images. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Xia, K.; Yin, J.; Deng, S.; Feng, H. FFPNet: Fine-Grained Feature Perception Network for Semantic Change Detection on Bi-Temporal Remote Sensing Images. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, M.; Gao, X.; Shi, W. Advances and challenges in deep learning-based change detection for remote sensing images: A review through various learning paradigms. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ding, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, Z.; Yang, X.; Chen, Z. ACOC-MT: More Effective Handling of Real-World Noisy Labels in Remote Sensing Semantic Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 4708318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liang, D.; Li, S.; Chen, S.; Huang, S.J. Handling noisy annotation for remote sensing semantic segmentation via boundary-aware knowledge distillation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 4408720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.; Han, K.; Ding, J.; Lyu, C.; Yuan, Z.; Chen, J.; Liu, Z. Adaptive label correction for robust medical image segmentation with noisy labels. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.12218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, C.; Duan, C.; Su, J.; Wang, L.; Atkinson, P.M. Multiattention network for semantic segmentation of fine-resolution remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 5607713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, C.; Duan, C.; Wang, L.; Atkinson, P.M. ABCNet: Attentive bilateral contextual network for efficient semantic segmentation of fine-resolution remotely sensed imagery. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 181, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, R.; Wang, D.; Duan, C.; Wang, T.; Meng, X. Transformer meets convolution: A bilateral awareness network for semantic segmentation of very fine resolution urban scene images. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, R.; Zhang, C.; Fang, S.; Duan, C.; Meng, X.; Atkinson, P.M. UNetFormer: A UNet-like transformer for efficient semantic segmentation of remote sensing urban scene imagery. Isprs J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2022, 190, 196–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, R.; Duan, C.; Zhang, C.; Meng, X.; Fang, S. A novel transformer based semantic segmentation scheme for fine-resolution remote sensing images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 3065, 6506105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.; Saoud, L.S. Semantic labeling of high-resolution images using EfficientUNets and transformers. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 4402913. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Hou, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Cheng, M.M.; Yang, J.; Li, X. Large selective kernel network for remote sensing object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tom, B.; Ravanbakhsh, M.; Demir, B. On the effects of different types of label noise in multi-label remote sensing image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Tao, D. Classification with noisy labels by importance reweighting. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2015, 38, 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Huang, W.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, X.; Jiao, J.; Ye, Q. Long-tailed distribution adaptation. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Virtual Event, China, 20–24 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Iliopoulos, F.; Kontonis, V.; Baykal, C.; Menghani, G.; Trinh, K.; Vee, E. Weighted distillation with unlabeled examples. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 7024–7037. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, K.; Wu, J. Probabilistic end-to-end noise correction for learning with noisy labels. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, G.; Awadallah, A.H.; Dumais, S. Meta label correction for noisy label learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Online, 2–9 February 2021; Volume 35. [Google Scholar]

- Sukhbaatar, S.; Bruna, J.; Paluri, M.; Bourdev, L.; Fergus, R. Training convolutional networks with noisy labels. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1406.2080. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Wang, Y.; Houle, M.E.; Zhou, S.; Erfani, S.; Xia, S.; Wijewickrema, S.; Bailey, J. Dimensionality-driven learning with noisy labels. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, Q.; Wu, X.; Xu, C.; Zuo, W.; Meng, Z. On better detecting and leveraging noisy samples for learning with severe label noise. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 136, 109210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, X.; Chen, Z.; Luo, Y.; Yi, J.; Bailey, J. Symmetric cross entropy for robust learning with noisy labels. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, S.; Lee, H.; Anguelov, D.; Szegedy, C.; Erhan, D.; Rabinovich, A. Training deep neural networks on noisy labels with bootstrapping. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6596. [Google Scholar]

- Han, B.; Yao, Q.; Yu, X.; Niu, G.; Xu, M.; Hu, W.; Tsang, I.; Sugiyama, M. Co-teaching: Robust training of deep neural networks with extremely noisy labels. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2018, 31, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, S.; Li, X. Unsupervised Noise-Resistant Remote-Sensing Image Change Detection: A Self-Supervised Denoising Network-, FCM_SICM-, and EMD Metric-Based Approach. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.I.; Akhter, S.; Hong, C.S.; Huh, E.N. Single teacher, multiple perspectives: Teacher knowledge augmentation for enhanced knowledge distillation. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations, Singapore, 24–28 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Lu, Z.; Nie, C.; Wen, G.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, X. Noisy node classification by bi-level optimization based multi-teacher distillation. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 25 February–4 March 2025; Volume 39. [Google Scholar]

- Kaito, T.; Takahashi, T.; Sakata, A. The effect of optimal self-distillation in noisy gaussian mixture model. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.16226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Yang, E.; Han, B.; Yang, Y.; Li, J.; Mao, Y.; Niu, G.; Liu, T. Understanding and improving early stopping for learning with noisy labels. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 24392–24403. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Wu, Z.; Lian, L.; Yu, S.X. Debiased learning from naturally imbalanced pseudo-labels. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Prechelt, L. Early stopping-but when? In Neural Networks: Tricks of the Trade; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; pp. 55–69. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Albrecht, C.M.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhu, X.X. AIO2: Online correction of object labels for deep learning with incomplete annotation in remote sensing image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5613917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin, H.; Xie, Y.; Xu, C. Learning with noisy labels via clean aware sharpness aware minimization. Sci. Rep. 2022, 15, 1350. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, R.; Liu, W.; Liu, Z.; Feng, C.; Yu, Z.; Rehg, J.M.; Xiong, L.; Song, L. Regularizing neural networks via minimizing hyperspherical energy. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, B.; Li, Y.; Xie, S.; Yuan, Z.; Feng, J. Exploring balanced feature spaces for representation learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Vienna, Austria, 4 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan, N.; Dhillon, I.S.; Ravikumar, P.K.; Tewari, A. Learning with noisy labels. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2013, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Cui, Q.; Wei, X.S.; Chen, Z.M. Bbn: Bilateral-branch network with cumulative learning for long-tailed visual recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Xiang, C.; Zou, W.; Xu, C. Mma regularization: Decorrelating weights of neural networks by maximizing the minimal angles. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 19099–19110. [Google Scholar]

- Amsaleg, L.; Chelly, O.; Furon, T.; Girard, S.; Houle, M.E.; Kawarabayashi, K.I.; Nett, M. Estimating local intrinsic dimensionality. In Proceedings of the 21th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 10–13 August 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.X.; Wei, T.; Xiang, Y.; Li, Y.F. How re-sampling helps for long-tail learning? Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 75669–75687. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Feng, Z.; Yang, S. Semi-supervised object detection framework with object first mixup for remote sensing images. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium IGARSS, Brussels, Belgium, 11–16 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, X.; Liu, L.; Yang, R.; Yin, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, X. A review of data augmentation methods of remote sensing image target recognition. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Zhou, Z.; Leung, T.; Li, L.J.; Li, F.F. Mentornet: Learning data-driven curriculum for very deep neural networks on corrupted labels. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.; Liu, H.; Liu, T.; Niu, G.; Sugiyama, M.; Liu, Y. To smooth or not? when label smoothing meets noisy labels. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.04149. [Google Scholar]

- Lukasik, M.; Bhojanapalli, S.; Menon, A.; Kumar, S. Does label smoothing mitigate label noise? In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Virtual, 13–18 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ryota, H.; Yoshida, S.; Muneyasu, M. Confidentmix: Confidence-guided mixup for learning with noisy labels. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 58519–58531. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Cisse, M.; Dauphin, Y.N.; Lopez-Paz, D. Mixup: Beyond empirical risk minimization. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1710.09412. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.; Sun, X.; Diao, W.; Li, J.; Gao, X. Double similarity distillation for semantic image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 30, 5363–5376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Song, Y.; Cao, L.; Luo, J.; Li, L.J. Learning from noisy labels with distillation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, R.; Huang, Y.; Guan, Q.; Pu, M.; Zhang, R. Learning from pixel-level label noise: A new perspective for semi-supervised semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 31, 623–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arazo, E.; Ortego, D.; Albert, P.; O’Connor, N.; McGuinness, K. Unsupervised label noise modeling and loss correction. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Bai, B.; Zhao, S.; Bai, K.; Wang, F. Uncertainty-aware learning against label noise on imbalanced datasets. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Online, 22 February–1 March 2022; Volume 36. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Yang, X.; Meng, D.; Cao, X. An adaptive noisy label-correction method based on selective loss for hyperspectral image-classification problem. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ramanathan, V.; Xu, T.; Martel, A.L. Detecting Noisy Labels with Repeated Cross-Validations. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Marrakesh, Morocco, 6–10 October 2024; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ilya, L.; Hutter, F. Decoupled weight decay regularization. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.05101. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Lucas, J.; Ba, J.; Hinton, G.E. Lookahead optimizer: K steps forward, 1 step back. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2019, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Olaf, R.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Takumi, K. T-vMF similarity for regularizing intra-class feature distribution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Sabuncu, M. Generalized cross entropy loss for training deep neural networks with noisy labels. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2018, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ishida, T.; Yamane, I.; Sakai, T.; Niu, G.; Sugiyama, M. Do we need zero training loss after achieving zero training error? arXiv 2020, arXiv:2002.08709. [Google Scholar]

| Backbone | Training | Dataset | Vaihingen | Potsdam | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OA (%) | mIoU (%) | mF1 (%) | OA (%) | mIoU (%) | mF1 (%) | |||

| UNet [65] | Default [17] | Original | 92.1 | 80.9 | 89.2 | 91.4 | 84.4 | 89.9 |

| OPAB-stage1 | 92.1 | 81.1 | 89.3 | 91.7 | 84.9 | 90.2 | ||

| Distillation [57] | Refine | 92.6 | 81.3 | 89.4 | 91.9 | 88.2 | 93.7 | |

| OPAB (ours) | 93.9 | 84.6 | 91.5 | 93.9 | 88.7 | 92.7 | ||

| BANet [16] | Default [17] | Original | 90.5 | 81.4 | 89.6 | 91.0 | 86.3 | 92.5 |

| OPAB-stage1 | 92.9 | 83.2 | 90.6 | 91.5 | 86.6 | 92.7 | ||

| Distillation [57] | Refine | 93.7 | 85.1 | 91.8 | 92.7 | 89.1 | 94.2 | |

| OPAB (ours) | 94.7 | 86.8 | 92.8 | 93.0 | 89.5 | 94.4 | ||

| DC-Swin [18] | Default [17] | Original | 91.6 | 83.2 | 89.8 | 92.0 | 87.5 | 93.2 |

| OPAB-stage1 | 93.4 | 84.6 | 91.5 | 91.9 | 87.2 | 93.0 | ||

| Distillation [57] | Refine | 94.6 | 85.2 | 91.8 | 93.3 | 90.0 | 94.7 | |

| OPAB (ours) | 95.1 | 87.8 | 93.4 | 93.4 | 90.2 | 94.8 | ||

| UNetformer [17] | Default [17] | Original | 91.0 | 82.7 | 90.4 | 92.8 | 86.8 | 91.3 |

| OPAB-stage1 | 93.5 | 84.7 | 91.5 | 92.8 | 87.0 | 91.6 | ||

| Distillation [57] | Refine | 94.2 | 85.4 | 92.0 | 93.1 | 89.7 | 94.5 | |

| OPAB (ours) | 95.7 | 89.0 | 94.1 | 93.7 | 89.9 | 94.6 | ||

| Vaihingen | - | F1 (%) | Metrics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methods | Classifier> | Imp.surf | Building | Lowveg | Tree | Car | OA (%) | mIoU (%) | mF1 (%) |

| baseline [17] | linear | 92.7 | 95.3 | 84.9 | 90.6 | 88.5 | 91 | 82.7 | 90.4 |

| MMA [46] | linear | 96.9 | 95.8 | 84.7 | 89.9 | 87.8 | 93.4 | 83.9 | 91.0 |

| BBN [45] | linear->linear | 96.6 | 95.3 | 84.4 | 89.9 | 87.9 | 93 | 83.6 | 90.8 |

| BBN w MMA | linear->linear | 96.8 | 95.5 | 84.7 | 90.1 | 88.5 | 93.2 | 83.8 | 91.0 |

| cosine [66] | cosine | 96.1 | 95.5 | 84.2 | 90.0 | 50.0 | 92.6 | 74.4 | 83.2 |

| cosine w MMA | cosine | 96.6 | 95.5 | 84.7 | 90.2 | 78.4 | 93.1 | 81.0 | 89.1 |

| OPAB w/o MMA | linear->cosine | 97.0 | 95.8 | 85.0 | 90.1 | 88.7 | 93.5 | 84.3 | 91.3 |

| OPAB (ours) | linear->cosine | 96.9 | 95.6 | 85.4 | 90.3 | 89.4 | 93.5 | 84.7 | 91.5 |

| Potsdam | - | F1 (%) | Metrics | ||||||

| Methods | Classifier | Imp.surf | Building | Lowveg | Tree | Car | OA (%) | mIoU (%) | mF1 (%) |

| baseline [17] | linear | 93.6 | 97.2 | 87.7 | 88.9 | 96.5 | 92.8 | 86.5 | 91.3 |

| MMA [46] | linear | 93.7 | 96.3 | 87.5 | 89.1 | 96.2 | 92.6 | 86.5 | 91.5 |

| BBN [45] | linear->linear | 93.7 | 95.9 | 87.0 | 89.2 | 96.5 | 92.5 | 86.2 | 91.1 |

| BBN w MMA | linear->linear | 94.0 | 96.3 | 87.3 | 89.6 | 96.3 | 92.7 | 86.6 | 91.3 |

| cosine [66] | cosine | 93.9 | 96.2 | 87.6 | 89.0 | 95.9 | 92.5 | 86.3 | 91.3 |

| cosine w MMA | cosine | 94.0 | 96.3 | 87.5 | 89.1 | 96.2 | 92.6 | 86.5 | 91.3 |

| OPAB w/o MMA | linear->cosine | 93.9 | 96.3 | 87.5 | 89.3 | 96.5 | 92.7 | 86.6 | 91.4 |

| OPAB (ours) | linear->cosine | 94.2 | 96.6 | 87.6 | 89.3 | 96.5 | 92.8 | 87.0 | 91.6 |

| Vaihingen | F1 (%) | Metrics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imp. Surf. | Building | Low | Tree | Car | OA (%) | mIoU (%) | mF1 (%) | |

| 0.1 | 96.8 | 95.7 | 84.7 | 90.1 | 88.6 | 93.3 | 84.1 | 91.2 |

| 0.2 | 96.8 | 95.4 | 84.6 | 90.3 | 88.6 | 93.3 | 84.1 | 91.2 |

| 0.5 | 96.9 | 95.7 | 84.6 | 90.1 | 89.0 | 93.4 | 84.3 | 91.3 |

| 1 | 96.9 | 95.6 | 84.6 | 90.2 | 89.4 | 93.3 | 84.4 | 91.3 |

| 2 | 96.8 | 95.4 | 84.7 | 90.1 | 89.3 | 93.3 | 84.2 | 91.2 |

| 5 | 96.9 | 95.5 | 84.6 | 90.1 | 89.5 | 93.3 | 84.4 | 91.3 |

| 10 | 96.9 | 95.6 | 84.6 | 90.2 | 89.4 | 93.3 | 84.4 | 91.3 |

| Opt. Prac. | 96.9 | 95.6 | 85.4 | 90.3 | 89.4 | 93.5 | 84.7 | 91.5 |

| Vaihingen | F1 (%) | Metrics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | Imp.Surf. | Building | Low | Tree | Car | OA (%) | mIoU (%) | mF1 (%) |

| 0.1 | 96.9 | 95.5 | 84.7 | 90.2 | 89 | 93.4 | 84.3 | 91.3 |

| 0.3 | 96.9 | 95.5 | 84.9 | 90.3 | 88.7 | 93.4 | 84.3 | 91.3 |

| 0.5 | 96.9 | 95.7 | 84.9 | 90.1 | 88.7 | 93.4 | 84.3 | 91.3 |

| 0.7 | 96.9 | 95.7 | 84.8 | 90.1 | 88.8 | 93.4 | 84.3 | 91.3 |

| 0.9 | 96.9 | 95.6 | 84.7 | 90.1 | 89.2 | 93.4 | 84.4 | 91.3 |

| Val-Set Metrics (%) | Calibration Accuracy (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noise (%) | Method | OA | mIoU | mF1 | Train Set | Test Set |

| 0 | baseline [17] | 91.0 | 82.7 | 90.4 | – | – |

| OPAB-stage1 | 93.5 | 84.7 | 94.1 | – | – | |

| 10 | baseline [17] | 90.8 | 82.0 | 89.8 | 88.9 | 86.3 |

| OPAB-stage1 | 93.5 | 84.1 | 91.2 | 90.4 | 87.0 | |

| 20 | baseline [17] | 90.6 | 81.4 | 89.5 | 89.0 | 86.1 |

| OPAB-stage1 | 93.4 | 84.0 | 91.1 | 90.1 | 86.9 | |

| 30 | Baseline [17] | 90.7 | 81.9 | 89.8 | 89.0 | 86.2 |

| OPAB-stage1 | 93.5 | 84.1 | 91.2 | 90.3 | 86.9 | |

| Backbone | Vaihingen | Potsdam | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UnetFormer | OA (%) | mIoU (%) | mF1 (%) | OA (%) | mIoU (%) | mF1 (%) |

| baseline [17] | 91.0 | 82.7 | 90.4 | 92.8 | 86.8 | 91.3 |

| gce [67] | 93.2 | 83.5 | 90.8 | 92.2 | 85.7 | 90.7 |

| sce [30] | 93.4 | 83.4 | 90.8 | 92.5 | 86.2 | 91.3 |

| focal [68] | 93.3 | 83.7 | 90.9 | 92.2 | 85.8 | 91.0 |

| ema [40] | 93.3 | 83.5 | 90.8 | 92.2 | 85.9 | 91.0 |

| flooding [69] | 93.4 | 83.5 | 90.8 | 92.4 | 86.1 | 91.1 |

| mixup [55] | 86.7 | 77.5 | 90.4 | 92.1 | 85.7 | 90.9 |

| OPAB-stage1 | 93.5 | 84.7 | 91.5 | 92.8 | 87.0 | 91.6 |

| Vaihingen | F1 (%) | Metrics | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Round | Training | Dataset | Imp.Surf. | Building | Low Veg. | Tree | Car | OA (%) | mIoU (%) | mF1 (%) | Pixel Change |

| - | origin | origin | 92.7 | 95.3 | 84.9 | 90.6 | 88.5 | 91.0 | 82.7 | 90.4 | - |

| r[0] | OPAB | origin | 96.8 | 95.8 | 85.3 | 90.7 | 89.1 | 93.5 | 84.7 | 91.5 | 0.00% (+0.00%) |

| r[1] | OPAB | by-r[0] | 96.9 | 95.7 | 92.0 | 96.8 | 89.1 | 95.7 | 89.0 | 94.1 | 4.12% (+4.12%) |

| r[2] | OPAB | by-r[1] | 96.8 | 95.7 | 92.1 | 97.1 | 88.8 | 95.7 | 89.1 | 94.1 | 4.29% (+0.17%) |

| r[3] | OPAB | by-r[2] | 96.9 | 95.7 | 92.6 | 97.2 | 88.9 | 95.8 | 89.3 | 94.2 | 4.29% (+0.00%) |

| r[4] | OPAB | by-r[3] | 96.9 | 95.9 | 92.5 | 97.3 | 89.2 | 95.9 | 89.5 | 94.3 | 4.26% (−0.03%) |

| r[5] | OPAB | by-r[4] | 96.9 | 95.7 | 92.6 | 97.3 | 89.0 | 95.8 | 89.4 | 94.3 | 4.26% (−0.00%) |

| r[6] | OPAB | by-r[5] | 96.9 | 95.7 | 92.3 | 97.2 | 88.8 | 95.8 | 89.3 | 94.2 | 4.24% (−0.02%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liang, H.; Zheng, H.; Huang, J.; Ma, H.; Liang, Y. Online Prototype Angular Balanced Self-Distillation for Non-Ideal Annotation in Remote Sensing Image Segmentation. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010022

Liang H, Zheng H, Huang J, Ma H, Liang Y. Online Prototype Angular Balanced Self-Distillation for Non-Ideal Annotation in Remote Sensing Image Segmentation. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiang, Hailun, Haowen Zheng, Jing Huang, Hui Ma, and Yanyan Liang. 2026. "Online Prototype Angular Balanced Self-Distillation for Non-Ideal Annotation in Remote Sensing Image Segmentation" Remote Sensing 18, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010022

APA StyleLiang, H., Zheng, H., Huang, J., Ma, H., & Liang, Y. (2026). Online Prototype Angular Balanced Self-Distillation for Non-Ideal Annotation in Remote Sensing Image Segmentation. Remote Sensing, 18(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010022