Enhancing Machine Learning-Based GPP Upscaling Error Correction: An Equidistant Sampling Method with Optimized Step Size and Intervals

Highlights

- Integrating geostatistical methods into the ML-based GPP upscaling correction enhances the characterization of surface heterogeneity dynamics, improves training sample representativeness, and significantly increases the accuracy of ML-based correction models.

- When using identical interval counts, the optimal-step equidistant method consistently exceeds k-means clustering in performance metrics. This approach maintains high correction accuracy with minimized computational costs through appropriate interval selection.

- Our method enables efficient and precise calibration of coarse-resolution GPP products, supplying robust data foundations for mountainous carbon flux quantification and ecological assessments.

- Systematic analysis of surface heterogeneity factor contributions elucidates their mechanistic impacts on GPP estimation accuracy.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Data Preprocessing

2.1.1. Study Area

2.1.2. Data Preprocessing

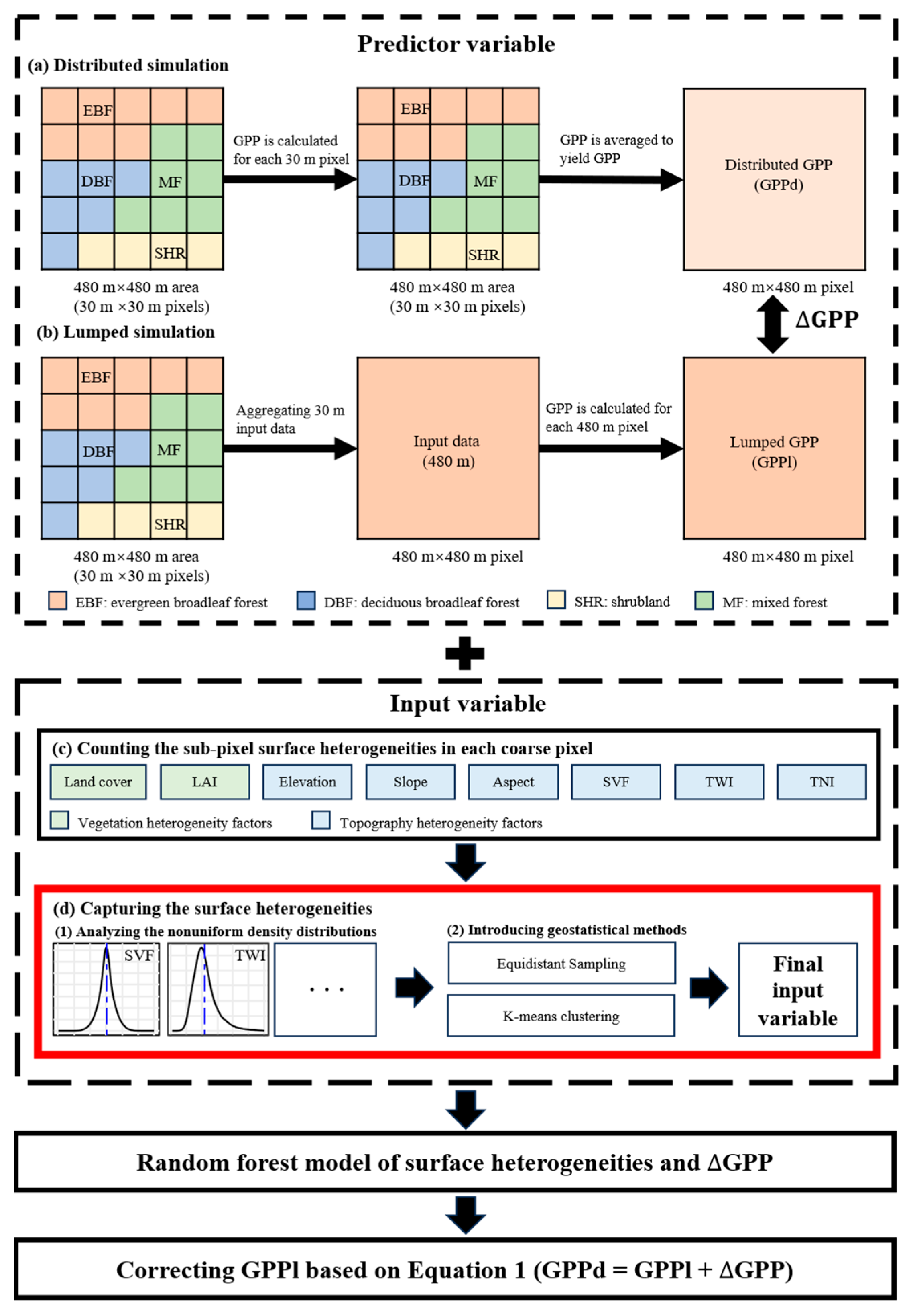

2.2. Upscaling Error Correction of GPP

2.2.1. ML-Based GPP Upscaling Error Correction

- (1)

- Using aggregated fine-resolution GPP data at coarse resolution (referred to as distributed GPP) as reference truth;

- (2)

- Establishing nonlinear relationships between surface heterogeneity features and upscaling errors through machine learning algorithms;

- (3)

- Deriving more accurate corrected results via “original coarse-resolution GPP (referred to as lumped GPP) minus predicted error” calculation.

2.2.2. Introducing Geostatistical Methods to Capture Surface Heterogeneity

2.3. Experimental Design

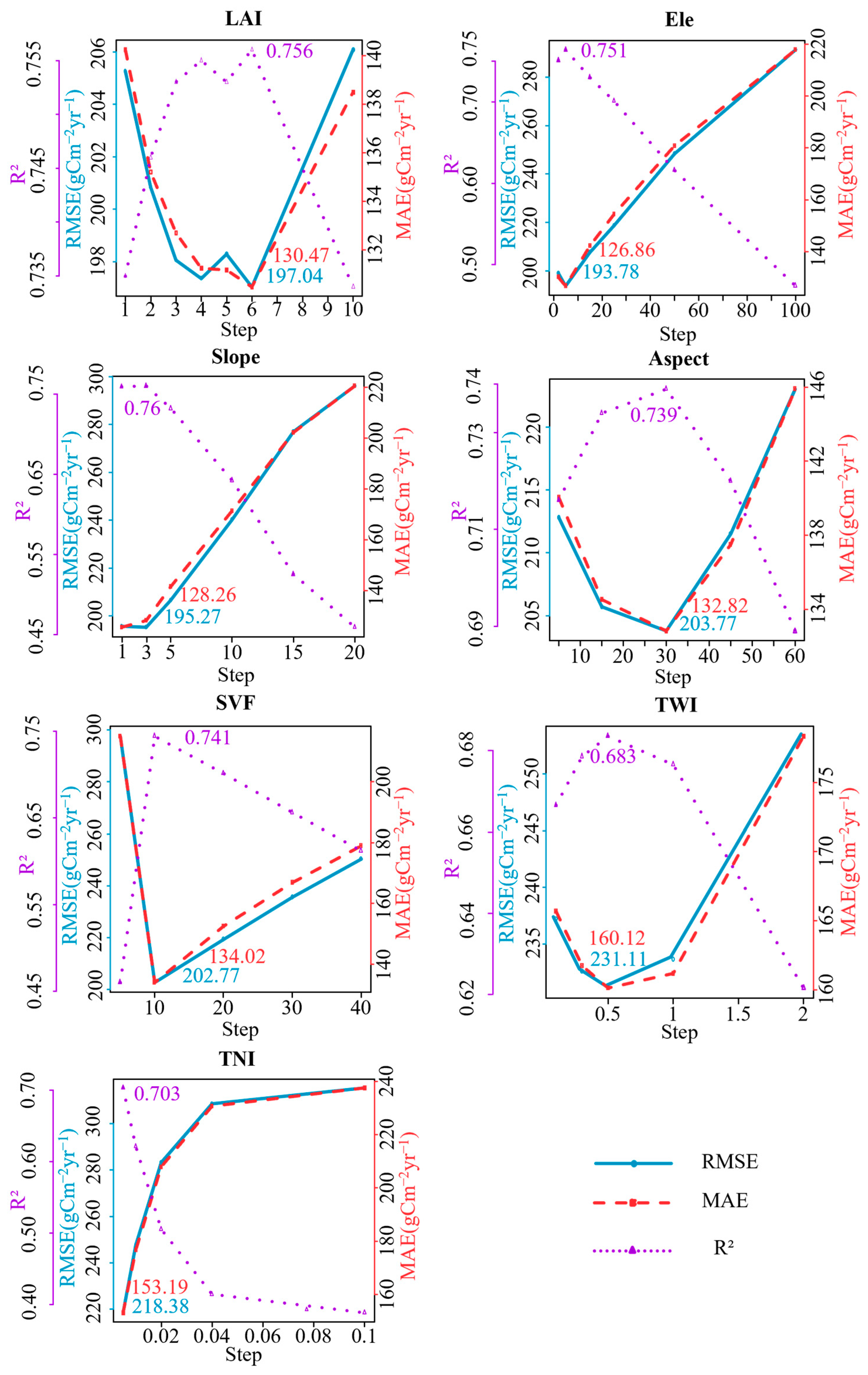

2.3.1. Parameter Setting Experiment

2.3.2. Factor Combination Experiment

2.3.3. Evaluation Index

3. Results

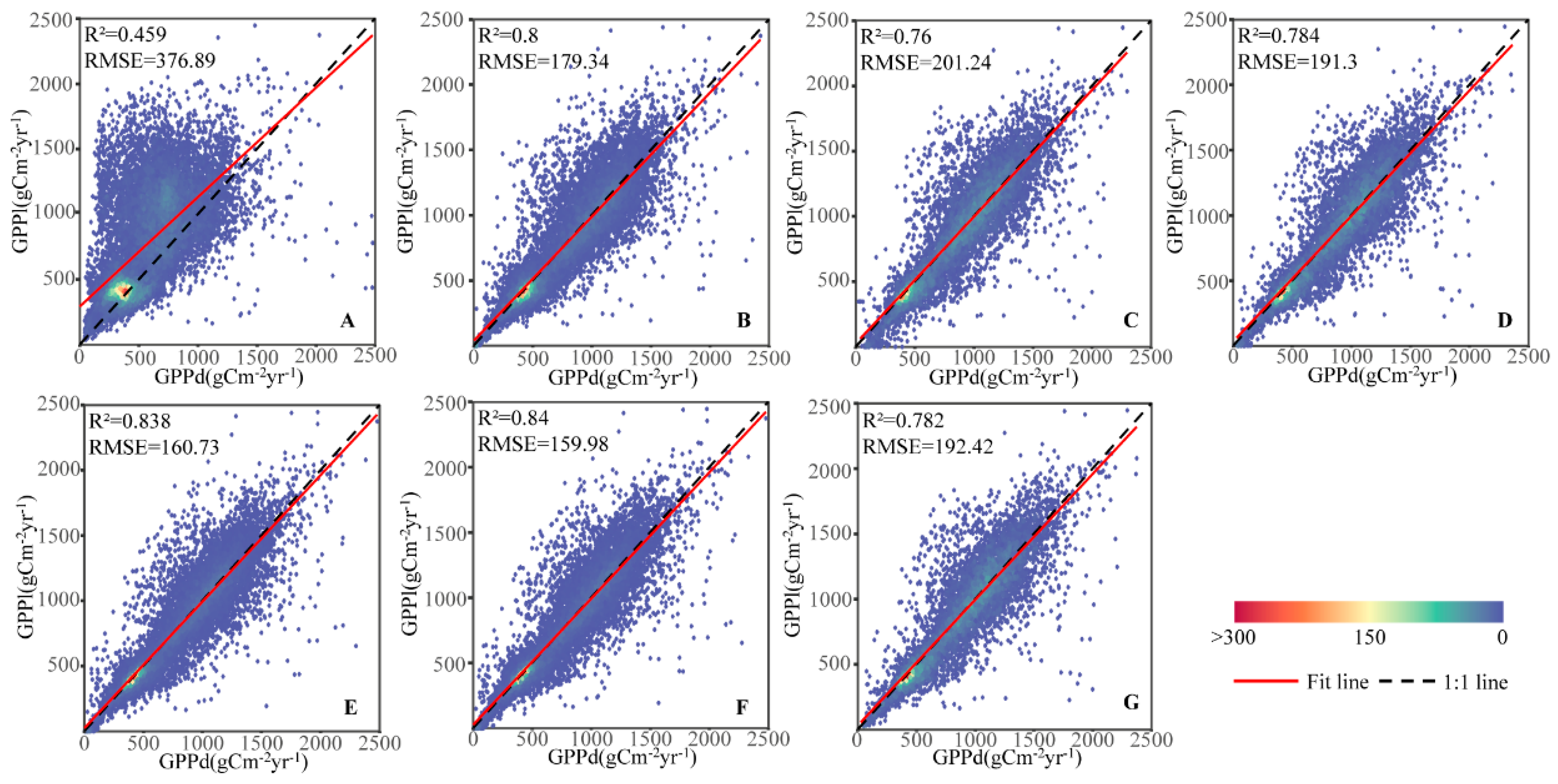

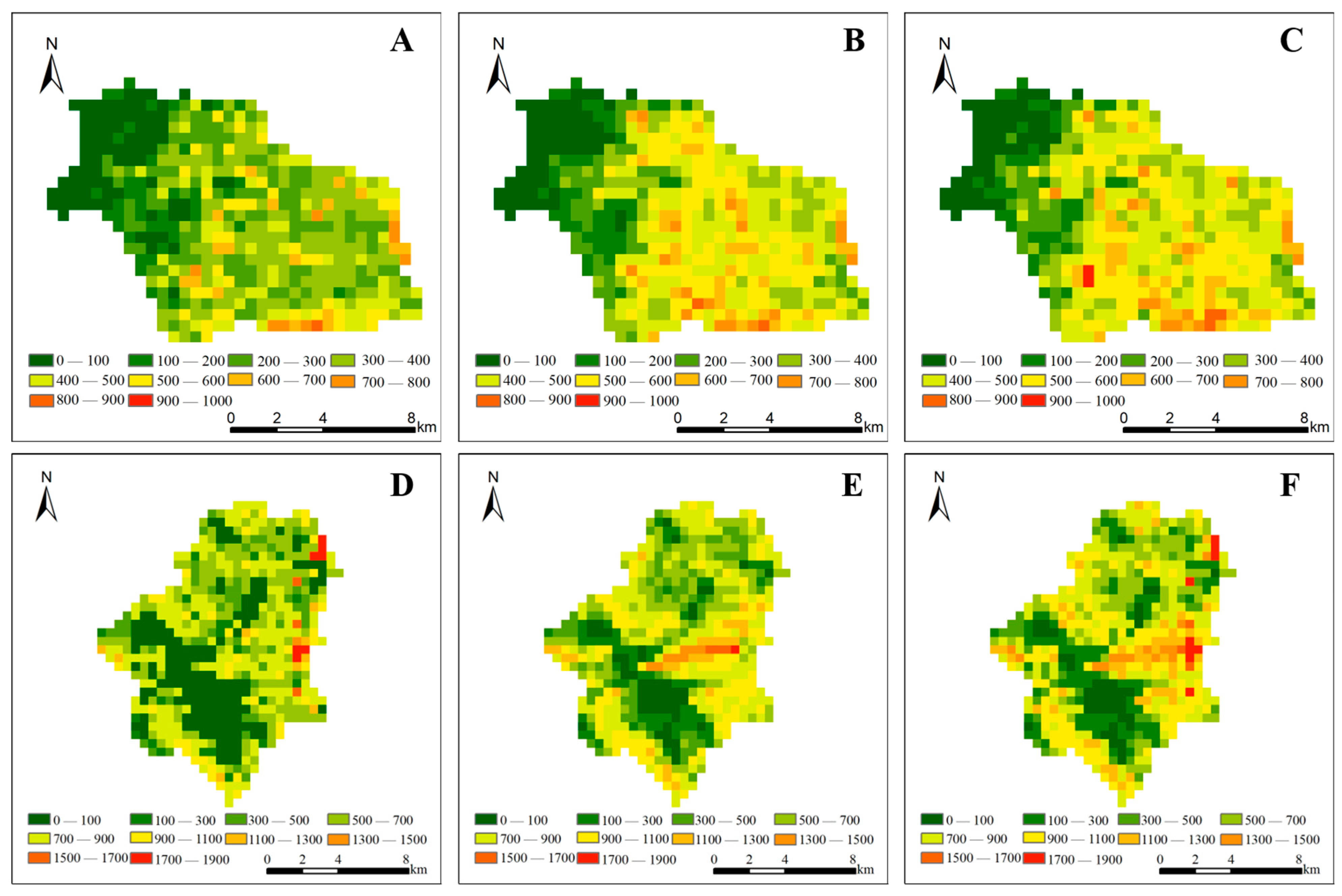

3.1. Correction Effect Using the Equidistant Sampling Method

3.2. Correction Effect Using the K-Means Clustering Method

3.3. Correction Effect Using the Superior Method

4. Discussion

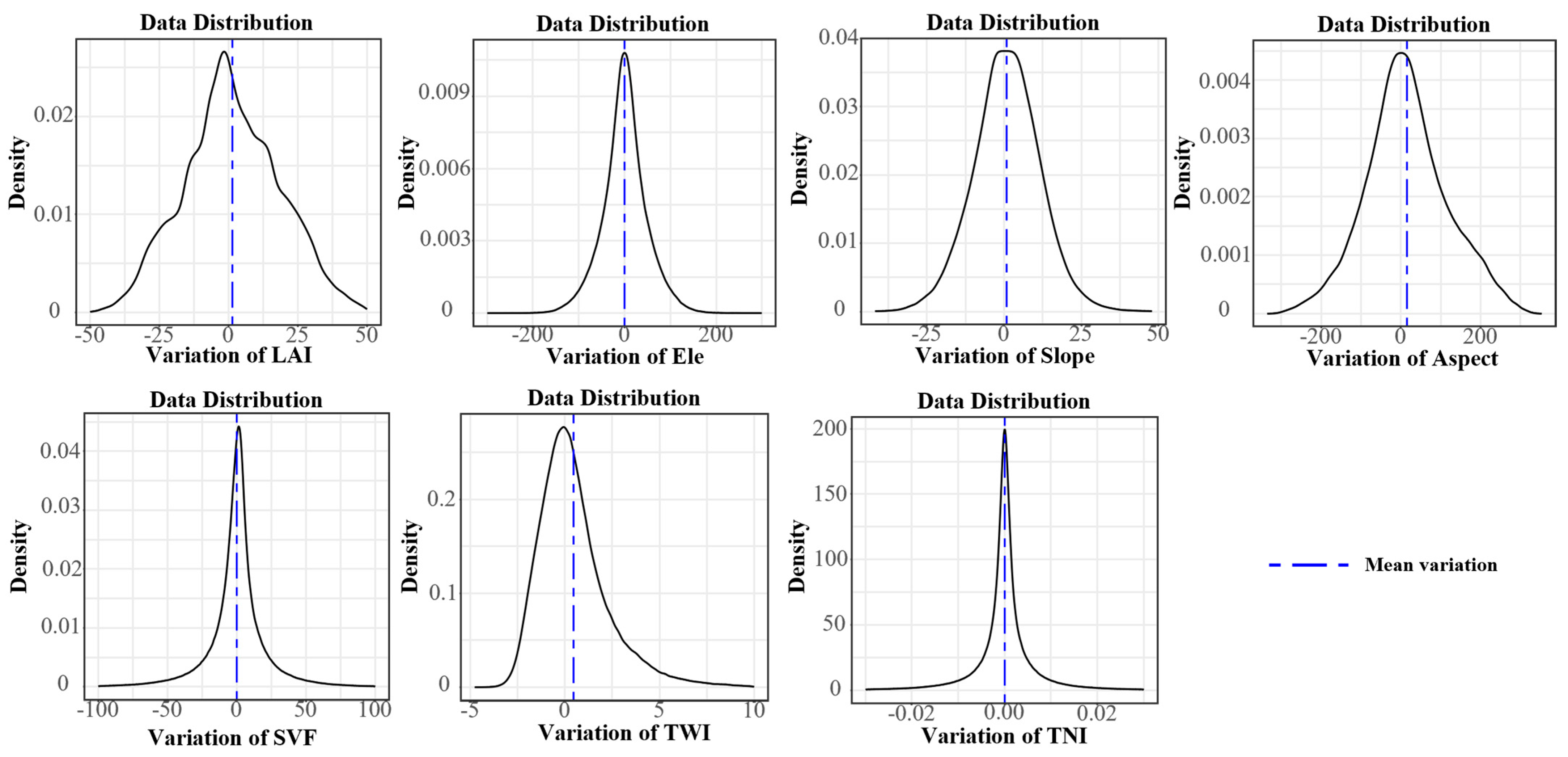

4.1. Improvement of Correction Accuracy by Considering Nonuniform Density Distributions of Surface Heterogeneities

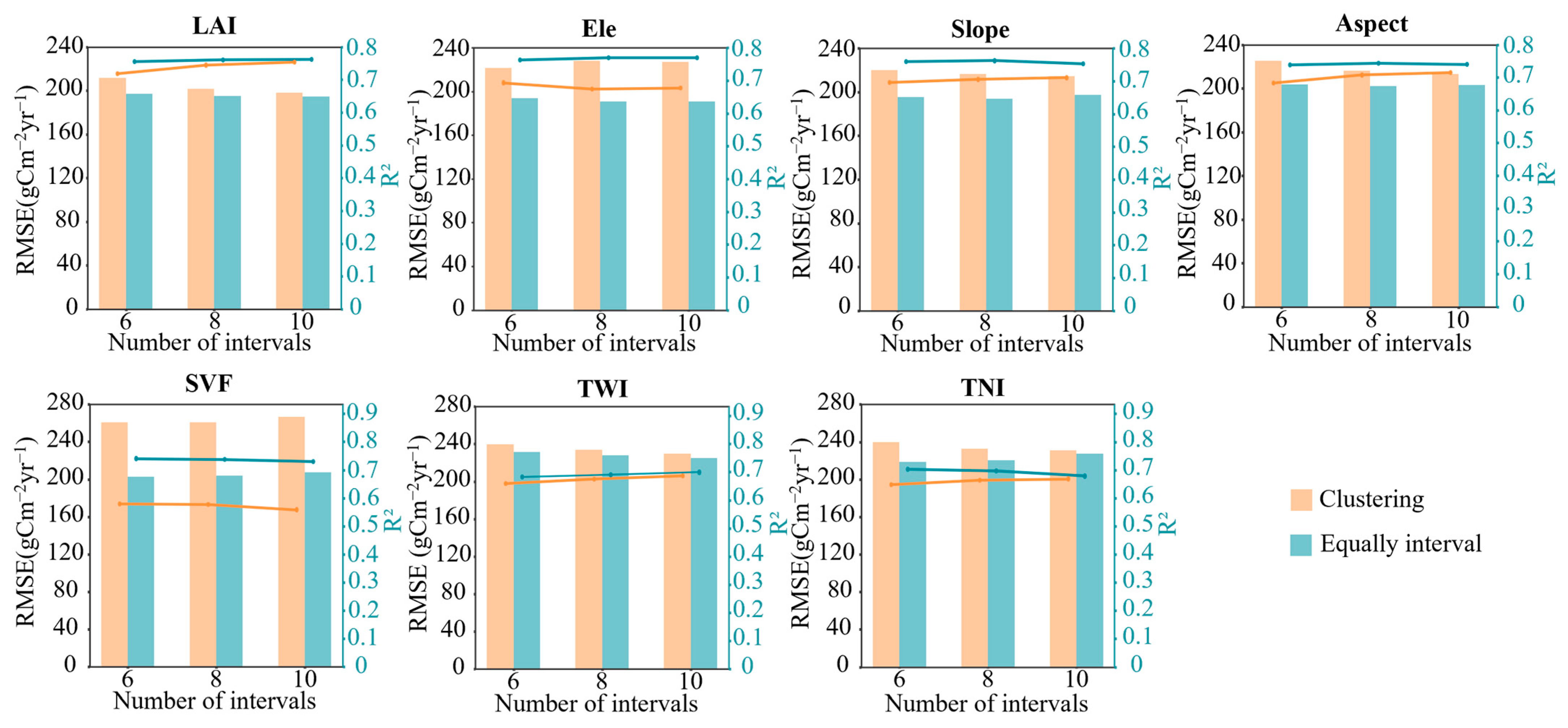

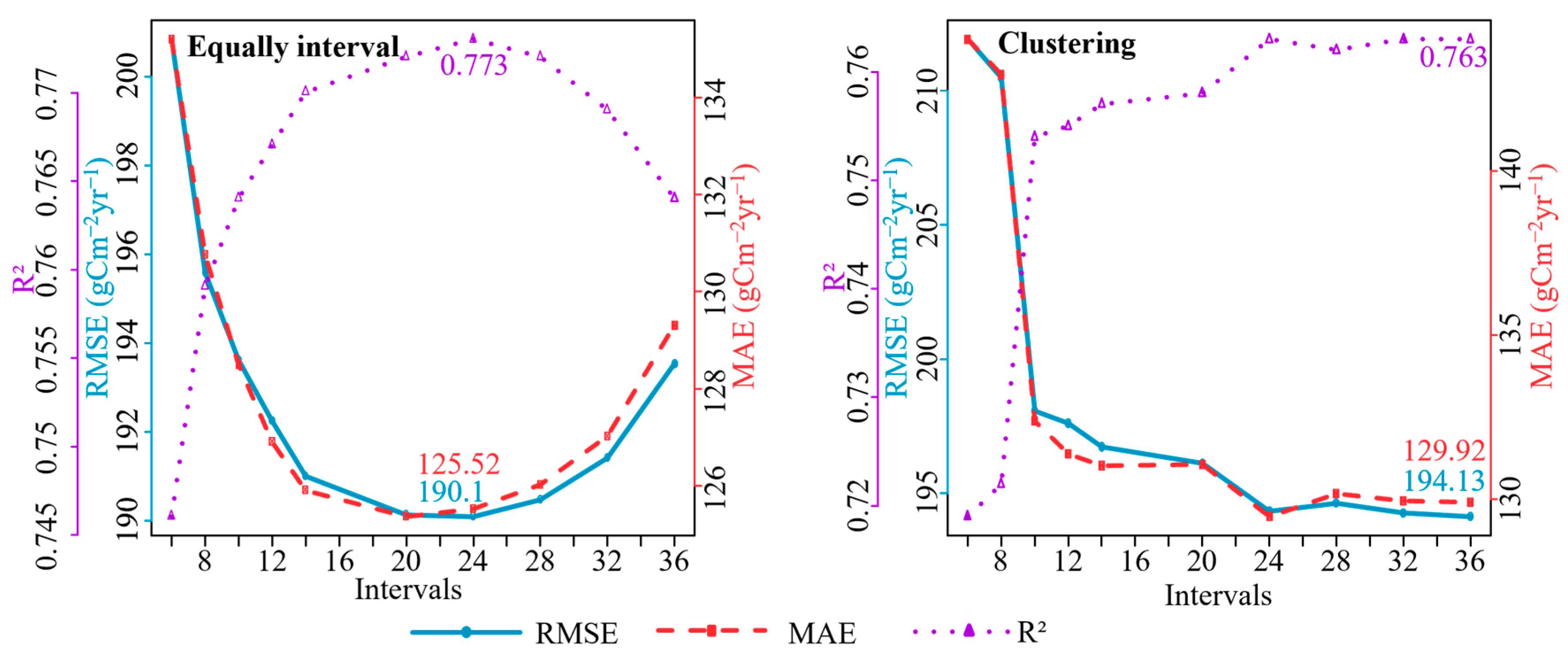

4.2. Influence of Interval Number on the Correction Accuracy of the Equidistant Sampling Method and K-Means Clustering Method

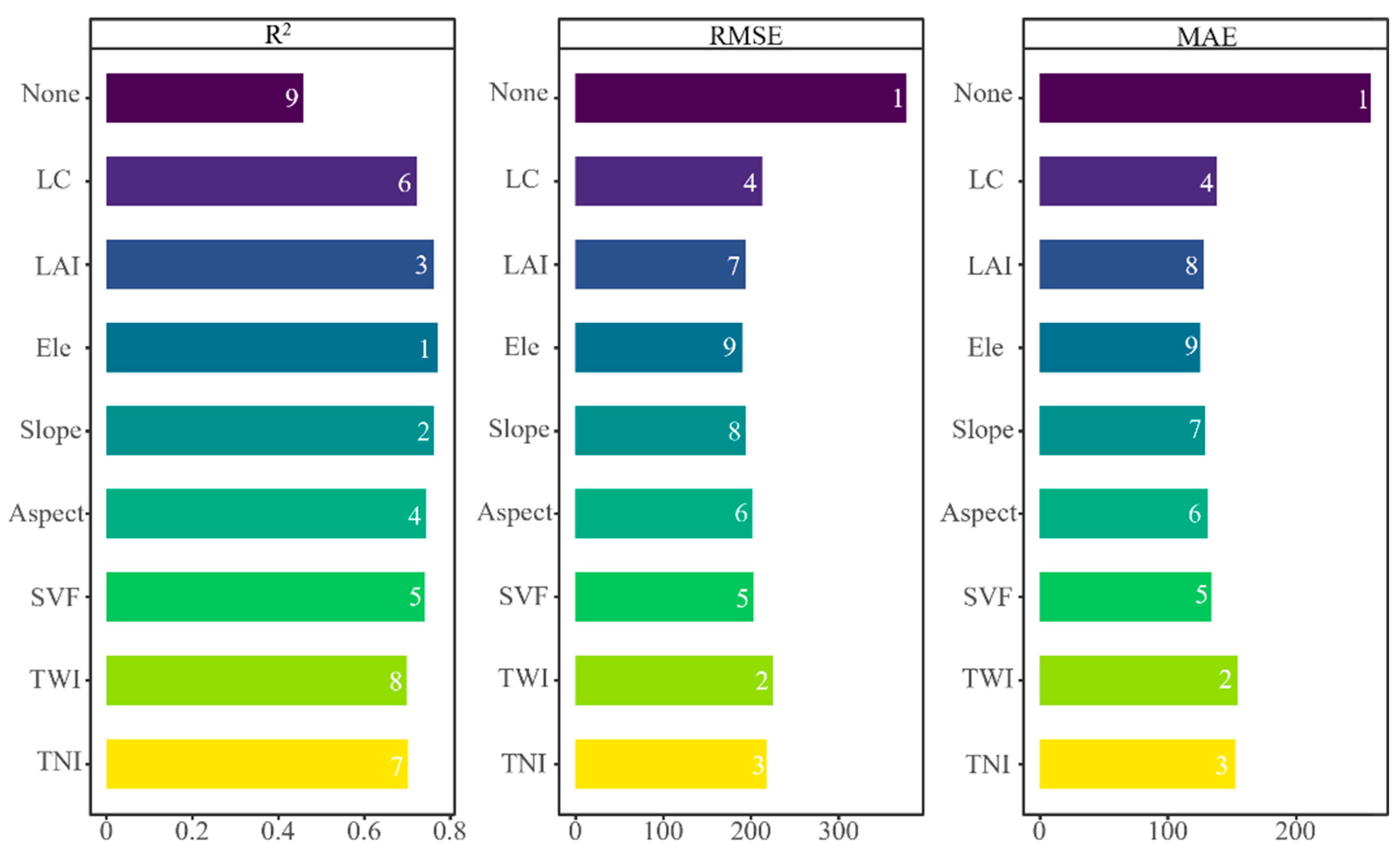

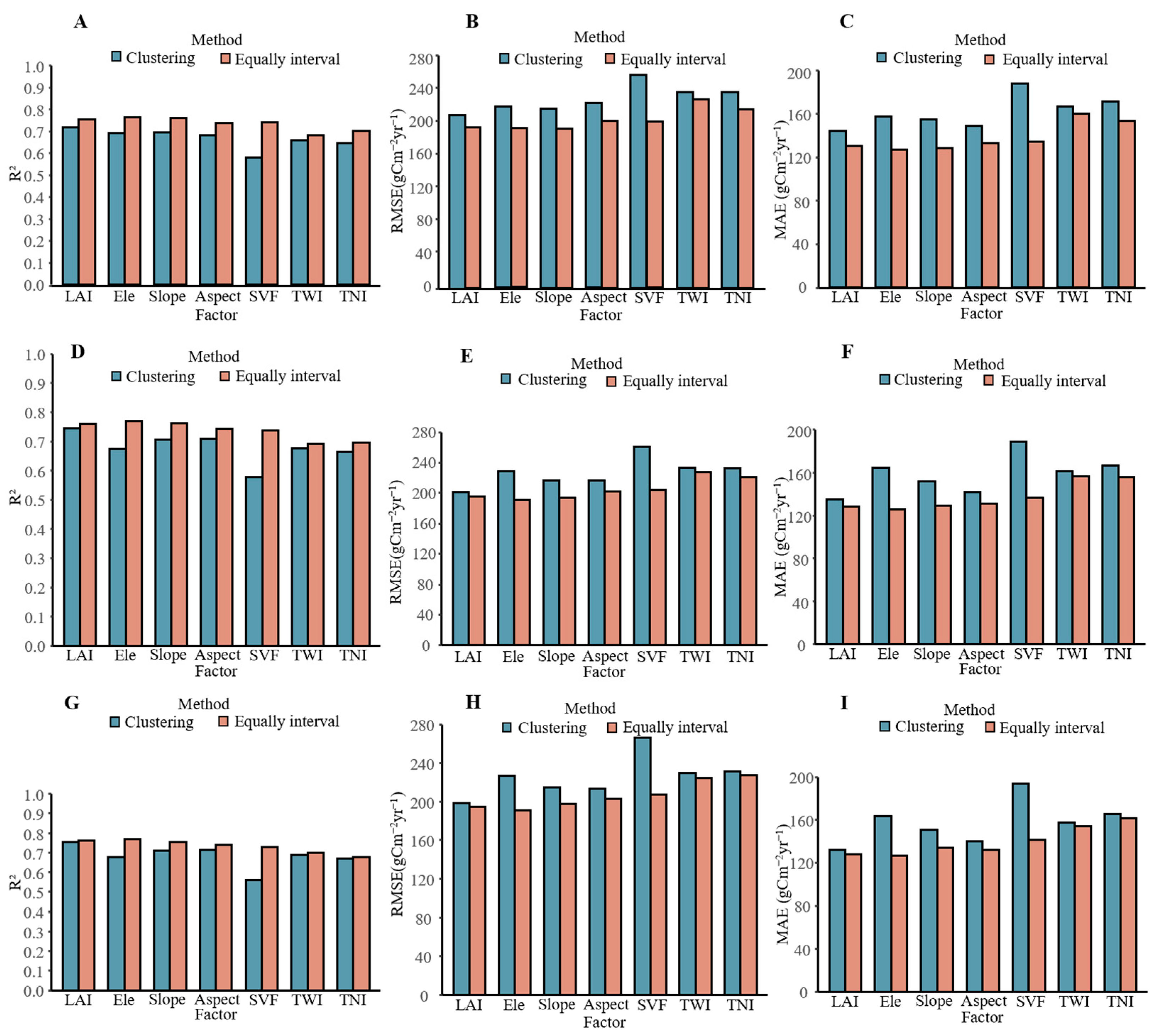

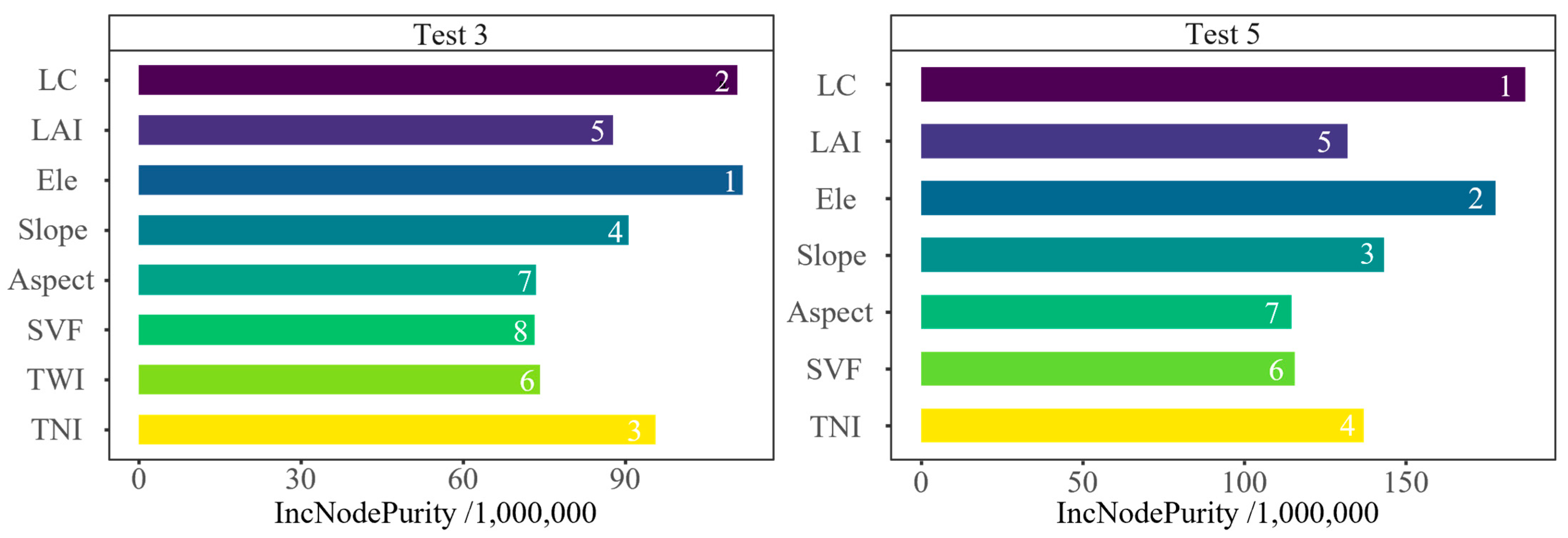

4.3. Contribution of Heterogeneity Factors in Correction

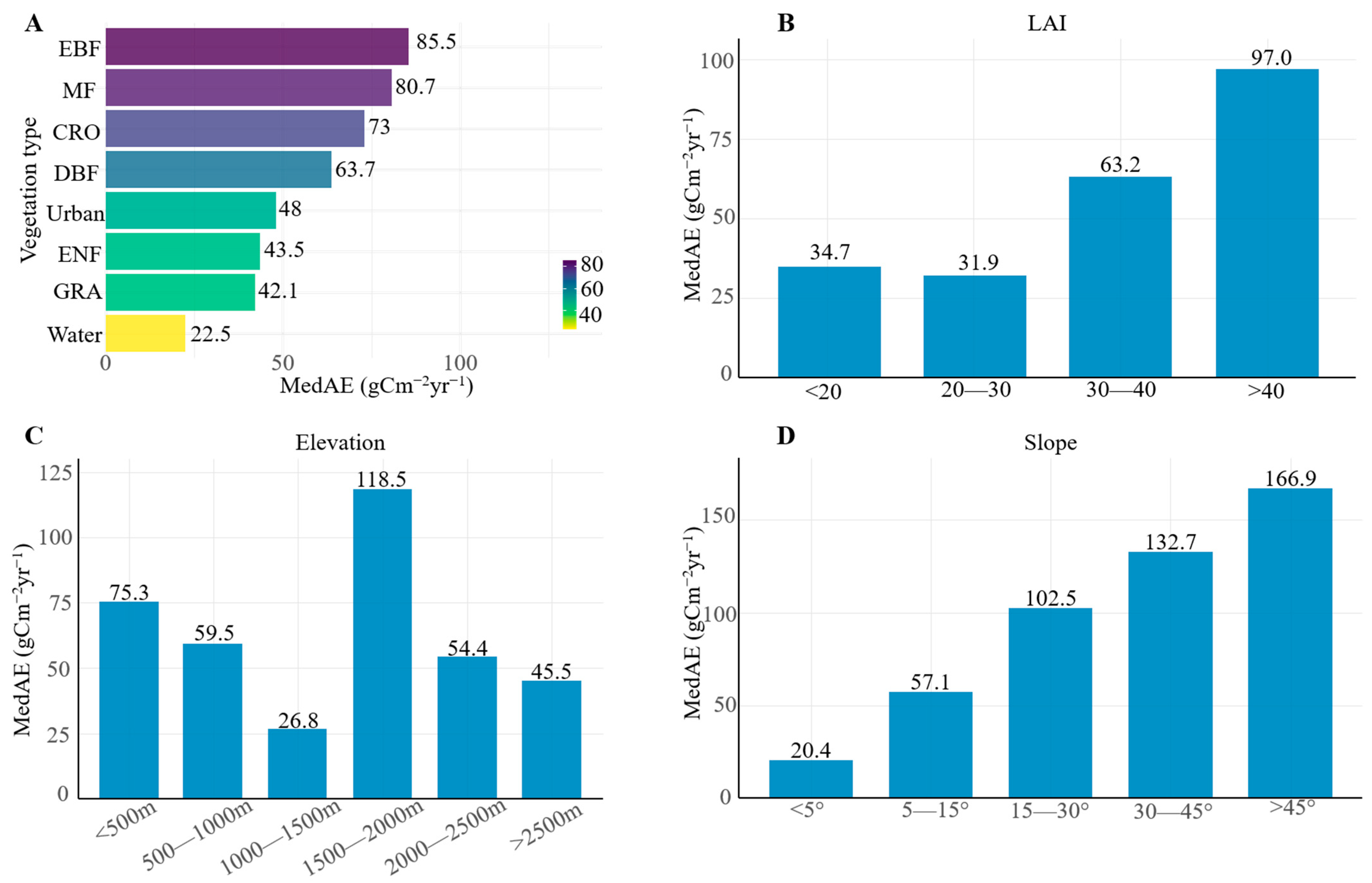

4.4. Residual Correction Error Analysis

5. Summary

- (1)

- Compared with conventional approaches using elevation alone for error correction (R2 of 0.48 and RMSE of 285 gCm−2yr−1), the implementation of the equidistant sampling method with optimal step size and intervals improved R2 by 0.27 and decreased RMSE by 91.22 gCm−2yr−1. Similarly, the application of the K-means clustering method enhanced R2 by 0.21 and reduced RMSE by 63.54 gCm−2yr−1.

- (2)

- When employing an identical number of statistical intervals, the equidistant sampling method with optimal step size consistently outperforms the k-means clustering approach. Using LAI calibration as an example, only when the number of intervals reaches 24 can the k-means clustering method match the accuracy of the optimal-step equidistant sampling method, with R2 values of 0.763 vs. 0.773 and RMSE values of 194.33 and 190.10 gCm−2yr−1, respectively. The optimal-step equidistant sampling method, paired with appropriate interval selection, offers an efficient solution that maintains high correction accuracy while minimizing computational costs.

- (3)

- Land cover, elevation, slope, and TNI were identified as the most influential factors, followed by LAI, whereas aspect, SVF, and TWI exhibited comparable importance.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reichstein, M.; Camps-Valls, G.; Stevens, B.; Jung, M.; Denzler, J.; Carvalhais, N.; Prabhat. Deep learning and process understanding for data-driven Earth system science. Nature 2019, 566, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schimel, D.; Pavlick, R.; Fisher, J.B.; Asner, G.P.; Saatchi, S.; Townsend, P.; Miller, C.; Frankenberg, C.; Hibbard, K.; Cox, P. Observing terrestrial ecosystems and the carbon cycle from space. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 21, 1762–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.; Shi, H.; Cheng, K.; Wang, Y.-P.; Piao, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xia, J.; Zhou, L.; Yuan, W.; et al. Joint structural and physiological control on the interannual variation in productivity in a temperate grassland: A data-model comparison. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 2965–2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Lin, S.; Wang, X. Progress of studies on satellite-based terrestrial vegetation production models in China. Progress. Phys. Geogr.-Earth Environ. 2022, 46, 889–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.Y.; Li, A.N.; Chen, J.M.; Guan, X.B.; Leng, J.Y. Quantifying Scaling Effect on Gross Primary Productivity Estimation in the Upscaling Process of Surface Heterogeneity. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2022, 127, e2021JG006775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, D.M.; Fisher, R.A.; Koven, C.D.; Oleson, K.W.; Swenson, S.C.; Bonan, G.; Collier, N.; Ghimire, B.; van Kampenhout, L.; Kennedy, D.; et al. The Community Land Model Version 5: Description of New Features, Benchmarking, and Impact of Forcing Uncertainty. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2019, 11, 4245–4287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfa, T.K.; Leung, L.-Y.R. Exploring new topography-based subgrid spatial structures for improving land surface modeling. Geosci. Model Dev. 2017, 10, 873–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.M.; Chen, X.; Ju, W. Effects of vegetation heterogeneity and surface topography on spatial scaling of net primary productivity. Biogeosciences 2013, 10, 4879–4896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Chen, J.M.; Gong, P.; Li, A. Spatial Scaling of Gross Primary Productivity Over Sixteen Mountainous Watersheds Using Vegetation Heterogeneity and Surface Topography. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2021, 126, e2020JG005848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, C.Y.; Shao, Z.F.; Huang, X.; Qian, J.X.; Cheng, G.; Ding, Q.; Fan, Y.W. Assessment of the importance of increasing temperature and decreasing soil moisture on global ecosystem productivity using solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 2066–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stocker, B.D.; Zscheischler, J.; Keenan, T.F.; Prentice, I.C.; Seneviratne, S.I.; Peñuelas, J. Drought impacts on terrestrial primary production underestimated by satellite monitoring. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoy, P.C.; Mauder, M.; Foken, T.; Marcolla, B.; Boegh, E.; Ibrom, A.; Arain, M.A.; Arneth, A.; Aurela, M.; Bernhofer, C.; et al. A data-driven analysis of energy balance closure across FLUXNET research sites: The role of landscape scale heterogeneity. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2013, 171–172, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorcroft, P.R.; Hurtt, G.C.; Pacala, S.W. A Method for Scaling Vegetation Dynamics: The Ecosystem Demography Model (ED). Ecol. Monogr. 2001, 71, 557–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Hu, B.; Li, Y. Easy-to-use spatial random-forest-based downscaling-calibration method for producing precipitation data with high resolution and high accuracy. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 25, 5667–5682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirboga, K.K.; Kucuksille, E.U.; Naldan, M.E.; Isik, M.; Gulcu, O.; Aksakal, E. CVD22: Explainable artificial intelligence determination of the relationship of troponin to D-Dimer, mortality, and CK-MB in COVID-19 patients. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2023, 233, 107492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathololoumi, S.; Firozjaei, M.K.; Biswas, A. Improving spatial resolution of satellite soil water index (SWI) maps under clear-sky conditions using a machine learning approach. J. Hydrol. 2022, 615, 128709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammady, M.; Pourghasemi, H.R.; Amiri, M. Land subsidence susceptibility assessment using random forest machine learning algorithm. Environ. Earth Sci. 2019, 78, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songlin, C.; Tianxing, W. Comparison Analyses of Equal Interval Method and Mean-standard Deviation Method Used to Delimitate Urban Heat Island. J. Geo-Inf. Sci. 2009, 11, 145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Van Arkel, Z.; Kaleita, A.L. Identifying sampling locations for field-scale soil moisture estimation using K-means clustering. Water Resour. Res. 2015, 50, 7050–7057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, J.M.; Cihlar, J.; Chen, W. Net primary productivity distribution in the BOREAS region from a process model using satellite and surface data. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1999, 104, 27735–27754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, J.Y.; Chen, J.M.; Li, W.Y.; Luo, X.Z.; Xu, M.Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, R.; Rogers, C.; Li, B.L.; Yan, Y.L. Global datasets of hourly carbon and water fluxes simulated using a satellite-based process model with dynamic parameterizations. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 16, 1283–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.M.; Chen, X.Y.; Ju, W.M.; Geng, X.Y. Distributed hydrological model for mapping evapotranspiration using remote sensing inputs. J. Hydrol. 2005, 305, 15–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Wang, J.; Yu, L.; Zhao, Y.C.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Liang, L.; Niu, Z.G.; Huang, X.M.; Fu, H.H.; Liu, S.; et al. Finer resolution observation and monitoring of global land cover: First mapping results with Landsat TM and ETM+ data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2013, 34, 2607–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.Y.; Chen, Y.; Shen, M.G.; Chen, J.; Zhou, J.; Wang, C.; Yang, W. A simple method to improve the quality of NDVI time-series data by integrating spatiotemporal information with the Savitzky-Golay filter. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 217, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Yang, W.; Zhu, X.L.; Chen, J.; Chen, X.H.; Yang, L.Q.; Helmer, E.H. An Improved Flexible Spatiotemporal DAta Fusion (IFSDAF) method for producing high spatiotemporal resolution normalized difference vegetation index time series. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 227, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, F.; Chen, J.M.; Plummer, S.; Chen, M.Z.; Pisek, J. Algorithm for global leaf area index retrieval using satellite imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2006, 44, 2219–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zyl, J.J. The Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM): A breakthrough in remote sensing of topography. Acta Astronaut. 2001, 48, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, R.; Zinko, U.; Seibert, J. On the calculation of the topographic wetness index: Evaluation of different methods based on field observations. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2006, 10, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaksek, K.; Ostir, K.; Kokalj, Z. Sky-View Factor as a Relief Visualization Technique. Remote Sens. 2011, 3, 398–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutengs, C.; Vohland, M. Downscaling land surface temperatures at regional scales with random forest regression. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 178, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Duan, S.-B.; Li, A.; Yin, G. A practical method for reducing terrain effect on land surface temperature using random forest regression. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 221, 635–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macqueen, J. Some Methods for Classification and Analysis of MultiVariate Observations. In Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 1967; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Celebi, M.E.; Kingravi, H.A.; Vela, P.A. A comparative study of efficient initialization methods for the k-means clustering algorithm. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2013, 40, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govind, A.; Chen, J.M.; Margolis, H.; Ju, W.; Sonnentag, O.; Giasson, M.-A. A spatially explicit hydro-ecological modeling framework (BEPS-TerrainLab V2.0): Model description and test in a boreal ecosystem in Eastern North America. J. Hydrol. 2009, 367, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Maayar, M.; Chen, J.M. Spatial scaling of evapotranspiration as affected by heterogeneities in vegetation, topography, and soil texture. Remote Sens. Environ. 2006, 102, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, D.; Bisht, G.; Huang, M.; Ma, P.-L.; Tesfa, T.; Lee, W.-L.; Gu, Y.; Leung, L.R. Impacts of Sub-Grid Topographic Representations on Surface Energy Balance and Boundary Conditions in the E3SM Land Model: A Case Study in Sierra Nevada. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2022, 14, e2021MS002862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Zhao, C.; Xie, Z. An End-to-End Satellite-Based Gpp Estimation Model Devoid of Meteorological and Land Cover Data. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2023, 331, 109337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Zhao, W.; Yin, G.; Fu, H.; Wang, X. Divergent Ecological Restoration Driven by Afforestation Along the North and South Banks of the Yarlung Zangbo Middle Reach. Land Degrad. Dev. 2025, 36, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, X.; Xu, K.; Zhao, P.; Wang, X.; Han, H. Influence of Mountain Shadows on Forest-Dominant Tree Species Mapping and Its Response to Topographic Corrections. For. Sci. 2025, 71, 625–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Chen, J.M.; Guo, Z.; Miao, G.; Zeng, H.; Wang, R.; Huang, Z.; Wang, Y. Improving UAV-Based LAI Estimation for Forests Over Complex Terrain by Reducing Topographic Effects on Multispectral Reflectance. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, K.; Ohta, T.; Nakai, T.; Kuwada, T.; Daikoku, K.I.; Iida, S.I.; Yabuki, H.; Kononov, A.V.; Molen, M.K.V.D.; Kodama, Y. Energy consumption and evapotranspiration at several boreal and temperate forests in the Far East. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2008, 148, 1978–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielis, S.; Etzold, S.; Zweifel, R.; Eugster, W.; Haeni, M.; Buchmann, N. NEP of a Swiss subalpine forest is significantly driven not only by current but also by previous year’s weather. Biogeosciences 2014, 11, 1627–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, M.; Pavelka, M.; Montagnani, L.; Kutsch, W.; Lindroth, A.; Juszczak, R.A.; Janouš, D. Soil surface CO2 efflux measurements in Norway spruce forests: Comparison betweenfour different sites across Europe—From boreal to alpine forest. Geoderma 2013, 192, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindauer, M.; Schmid, H.P.; Grote, R.; Mauder, M.; Steinbrecher, R.; Wolpert, B. Net ecosystem exchange over a non-cleared wind-throw-disturbed upland spruce forest—Measurements and simulations. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2014, 197, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcolla, B.; Pitacco, A.; Cescatti, A. Canopy Architecture and Turbulence Structure in a Coniferous Forest. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 2003, 108, 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagnani, L.; Manca, G.; Canepa, E.; Georgieva, E.; Acosta, M.; Feigenwinter, C.; Janous, D.; Kerschbaumer, G.; Lindroth, A.; Minach, L. A new mass conservation approach to the study of CO2 advection in an alpine forest. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2009, 114, D07306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, B.; Guenther, A.; Greenberg, J.; Goldstein, A.; Fall, R. Canopy fluxes of 2-methyl-3-buten-2-ol over a ponderosa pine forest by relaxed eddy accumulation: Field data and model comparison. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1999, 104, 26107–26114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arain, M.A.; Restrepo-Coupe, N. Net ecosystem production in a temperate pine plantation in southeastern Canada. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2005, 128, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.L.; Sun, O.J.; Law, B.E. Disturbance and net ecosystem production across three climatically distinct forest landscapes. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2004, 18, GB4017.1–GB4017.11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond-Lamberty, B.; Wang, C.; Gower, S.T. A global relationship between the heterotrophic and autotrophic components of soil respiration? Glob. Change Biol. 2004, 10, 1756–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthoni, P.M.; Unsworth, M.H.; Law, B.E.; Irvine, J.; Moore, D. Seasonal differences in carbon and water vapor exchange in young and old-growth ponderosa pine ecosystems. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2002, 111, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruehr, N.K.; Martin, J.G.; Law, B.E. Effects of water availability on carbon and water exchange in a young ponderosa pine forest: Above- and belowground responses. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2012, 164, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, L.P.; Keenan, T.F.; Burns, S.P.; Huxman, T.E.; Monson, R.K. Climate controls over ecosystem metabolism: Insights from a fifteen-year inductive artificial neural network synthesis for a subalpine forest. Oecologia 2017, 184, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubinet, M.; Chermanne, B.; Vandenhaute, M.; Longdoz, B.; Yernaux, M.; Laitat, E. Long term carbon dioxide exchange above a mixed forest in the Belgian Ardennes. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2001, 108, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzold, S.; Ruehr, N.K.; Zweifel, R.; Dobbertin, M.; Zingg, A.; Pluess, P.; Häsler, R.; Eugster, W.; Buchmann, N. The Carbon Balance of Two Contrasting Mountain Forest Ecosystems in Switzerland: Similar Annual Trends, but Seasonal Differences. Ecosystems 2011, 14, 1289–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, D.-X.; Wu, J.-B.; Zhao, X.-S.; Han, S.-J.; Yu, G.-R.; Sun, X.-M.; Jin, C.-J. CO2 fluxes over an old, temperate mixed forest in northeastern China. Agr. Forest Meteorol. 2006, 137, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Experiment | Parameter Setting | Experimental Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Equidistant sampling | I | The step: the value incremented from 0 (e.g., set the step to 10, 20, 30, 40, respectively). The number of intervals: 6. |

|

| II | The step: the optimal step identified in experiment I. The number of intervals: 6, 8, 10, respectively. | Analyzing the calibration accuracy of increasing intervals appropriately. | |

| K-means clustering | III | The categories: 6, 8, 10, respectively (the corresponding intervals are 6, 8, 10). |

|

| Equidistant sampling/K-means clustering | IV | K-means clustering method: the categories are set from 6 to 36 (the corresponding intervals are from 6 to 36). Equal interval method: the step is set to the optimal step, and the number of intervals is set from 6 to 36. | Testing the performance of the two methods when a sufficient or an excessive number of intervals is set. |

| Test Group | Description | Factor Combination |

|---|---|---|

| Control group | — | None |

| Test 1 | Vegetation heterogeneities | LC + LAI |

| Test 2 | Topographic heterogeneities | Ele + Slope + Aspect + SVF + TWI + TNI |

| Test 3 | All surface heterogeneities | LC + LAI + Ele + Slope + Aspect + SVF + TWI + TNI |

| Test 4 | Without TWI and TNI | LC + LAI + Ele + Slope + Aspect + SVF |

| Test 5 | Without TWI | LC + LAI + Ele + Slope + Aspect + SVF + TNI |

| Test 6 | Without TNI | LC + LAI + Ele + Slope + Aspect + SVF + TWI |

| Accuracy | LAI | Ele | Slope | SVF | TWI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR | TW | PR | TW | PR | TW | PR | TW | PR | TW | |

| R2 | 0.57 | 0.756 | 0.48 | 0.751 | 0.5 | 0.76 | 0.57 | 0.741 | 0.45 | 0.683 |

| RMSE (gCm−2yr−1) | 259 | 197 | 285 | 193.8 | 280 | 195.3 | 259 | 202.8 | 294 | 231.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Zuo, J.; Yong, Z.; Xie, X. Enhancing Machine Learning-Based GPP Upscaling Error Correction: An Equidistant Sampling Method with Optimized Step Size and Intervals. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010023

Wang Z, Zuo J, Yong Z, Xie X. Enhancing Machine Learning-Based GPP Upscaling Error Correction: An Equidistant Sampling Method with Optimized Step Size and Intervals. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010023

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zegen, Jiaqi Zuo, Zhiwei Yong, and Xinyao Xie. 2026. "Enhancing Machine Learning-Based GPP Upscaling Error Correction: An Equidistant Sampling Method with Optimized Step Size and Intervals" Remote Sensing 18, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010023

APA StyleWang, Z., Zuo, J., Yong, Z., & Xie, X. (2026). Enhancing Machine Learning-Based GPP Upscaling Error Correction: An Equidistant Sampling Method with Optimized Step Size and Intervals. Remote Sensing, 18(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010023