Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Gray/red-brown soils and a no-tilled system presented the most challenging soil backgrounds in the detection of corn plants in different corn growth stages at both flight heights (30 and 70 m).

- The V3 and V5 were the best predicted corn growth stages for 70 m flight height using the YOLOv9-small version.

What is the implication of the main findings?

- Gray/red-brown and no-tilled soil backgrounds need more powerful models as well as hyperparameter optimization for lightweight models.

- Corn stand count and prediction can be performed at 70 m flight heights, increasing the scalability of plant count models to map larger fields.

Abstract

Accurate stand count and growth stage detection are essential for crop monitoring, since traditional methods often overlook field variability, leading to poor management decisions. This study evaluated the performance of the YOLOv9-small model for detecting and counting corn plants under real field conditions. The model was tested across three soil background types, two flight heights (30 and 70 m), and four corn growth stages (V2, V3, V5, and V6). Unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) imagery was collected from three distinct fields and cropped into 640 × 640 pixels. Datasets were split into training (70%), validation (20%), and testing (10%) datasets. Model performance was assessed using precision, recall, classification loss, and mean average precision of 50% and 50–90%. The results showed that the V3 and V5 stages yielded the highest detection accuracy, with mAP50 values exceeding 85% in conventional tillage fields and slightly lower performance in gray/red-brown conditions due to background interference. Increasing flight height to 70 m reduced accuracy by 8–12%, though precision remained high, particularly at V5, and performance was poorest for V2 and V6. In conclusion, YOLOv9-small is effective for early-stage corn detection, particularly at V3 and V5, with 30 m providing optimal results. However, 70 m may be acceptable at V5 to optimize mapping time.

1. Introduction

Corn is an important crop for both human consumption and animal feed. Its production is heavily concentrated in the United States, China, and Brazil, which together account for approximately 32%, 23%, and 10% of global corn output, respectively [1]. Despite its significance, corn production faces several limitations, particularly those related to stand quality, which directly impacts yield potential and economic returns [2,3,4]. Plant density also plays a critical role and is influenced by factors such as hybrid selection, crop maturity, weather and soil conditions, length of the growing season, management practices, and planting date [4,5]. Modifying plant density has long been employed as a strategy to increase yields [6,7,8]. However, many of these approaches do not take into account field-level spatial variability, which can lead to suboptimal outcomes, as microenvironmental differences may restrict the crop’s yield potential.

Early detection of corn growth stages and accurate stand counting are essential for supporting precision agriculture practices. These tasks enable farmers to make informed decisions regarding post-emergence herbicide applications, replanting needs, fertilizer management, and assessment of spatial field variability relative to yield maps [4,9]. However, identifying corn stages and performing stand counts remain challenging due to the limitations of conventional methods. Traditionally, stand counting involves walking through the field and sampling specific areas by measuring row spacing and manually counting plants within small plots [3,4]. This manual process is labor-intensive, time-consuming, and fails to capture variability across the entire field. In most cases, assessments are limited to field borders or isolated sample points, which may not accurately represent the true stand distribution [4].

Advancements in computer science and precision agriculture have significantly contributed to the mapping of field variability and corn stand count. Various studies have addressed this task using approaches such as Mask Region-Based Convolutional Neural Network [10], U-Net [4,11], adapted You Only Look Once (YOLO) models [12], small ground robots [13], and the integration of multispectral imagery with large-scale deep learning models [14]. However, these studies predominantly rely on complex two-stage deep learning architectures, which require extensive hyperparameter tuning and long processing times. Moreover, most experiments were conducted at very low altitudes, typically between 10 and 25 m, limiting their applicability to small, experimental plots rather than large-scale agricultural fields. Additionally, they often overlook key environmental factors such as variations in soil background color, especially under no-tillage systems, which introduce substantial challenges for accurate corn detection. These gaps highlight the need for more scalable, efficient, and robust solutions capable of operating under realistic field conditions.

The YOLO family has been widely applied to agricultural tasks for a long time. Introduced by Joseph Redmon in 2016 [15], YOLOv1 represents the first version of this family of one-stage object detectors. Subsequent versions, culminating in YOLOv3, introduced several key improvements, including multi-scale training, dimensional clustering, spatial pyramid pooling (SPP) blocks, and the Darknet-53 backbone. In 2020, Alexey Bochkovskiy proposed YOLOv4 with the CSPDarknet-53 backbone, followed by YOLOv5 developed by Glenn Joche, which incorporated anchor-free detection, a Swish-based activation function, and a PANet-style neck [16]. The Meituan Vision AI Department released YOLOv6, incorporating self-attention mechanisms to improve accuracy. Xu et al. (2022) introduced YOLOv7 with transformer components and E-ELAN re-parameterization, and Ultralytics presented YOLOv8 in 2023, leveraging Generative Adversarial Network techniques to enhance the model’s ability to handle different scenarios [16]. More recently, Wang and Liao [17] developed YOLOv9 with the PGI and GELAN modules, Wang et al. [17] introduced YOLOv10 as a non-maximum suppression-free (NMS-free) detector, Ultralytics released YOLOv11 with C3k2 and C2PSA modules in the backbone and neck, and Tian et al. [18] proposed YOLOv12 as the first attention-centric YOLO model, incorporating the R-ELAN mechanism [19].

One-stage models, such as those in the YOLO family, have significantly advanced the field of computer vision and play a fundamental role in agricultural applications. These models perform object classification and bounding box prediction simultaneously, making them well-suited for real-time tasks due to their speed and efficiency [20,21]. Recent versions, such as YOLOv9, introduce innovations like Programmable Gradient Information (PGI) and the Generalized Efficient Layer Aggregation Network (GELAN), which improve model performance by enhancing gradient flow and reducing information loss in deeper layers [20]. These innovations increase the performance and decrease the number of flops and hyperparameters, particularly in the MS COCO dataset and a lightweight version, such as the “small” model. They also contribute to high precision in heterogeneous backgrounds with multiple targets, emphasizing the use for different background and environment conditions. YOLOv9 is also available in multiple configurations: nano, small, medium, large, and X-large, allowing users to balance computational cost and detection accuracy based on the complexity of the task. As a result, YOLOv9 has seen widespread use in agriculture for diverse object detection tasks, including growth stage classification and identification in corn and disease detection [3,22,23].

Despite recent advances, applying object detection models in complex agricultural environments remains challenging, particularly in the presence of high background noise variability caused by soil color variations and management practices such as no-tillage. Furthermore, integrating these models into large-scale unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) mapping operations at higher flight altitudes continues to be a limitation, as most studies focus on ultra-low altitudes in controlled experimental plots. Both flight altitude and background complexity are known to affect model performance, and their integration into training data can improve the model’s ability to generalize across diverse field conditions [13,24]. Therefore, a highly variable dataset is needed to create robust models that can be generalized to accurately count corn plants under different soil conditions. Additionally, creating robust datasets by labeling images is a time-consuming and labor-intensive process that can contribute to poor performance for small models, since they require larger datasets to learn the pattern. Similarly, robust models such as transformers and Fast-RCNN seem to be an alternative to improve the model’s performance. However, these models demand powerful hardware, which can contribute to limited applications depending on the task.

This study aims to evaluate the performance of the YOLOv9-small model for detecting and counting corn plants at higher flight altitudes and varying soil backgrounds, mimicking conditions of large cropping areas. Specifically, the model was tested across three distinct soil background colors, two flight heights suitable for large-scale mapping (30 and 70 m), and four corn growth stages. This evaluation was guided by two formulated hypotheses. Hypothesis I: Corn plants with three or more fully developed leaves provide more favorable conditions for accurate object detection, regardless of background, whereas earlier stages are associated with higher misclassification due to greater visual similarity with the background. Hypothesis II: Higher UAV flight heights (70 m) can be used for corn plant detection across different growth stages with moderate accuracy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Location and Characterization

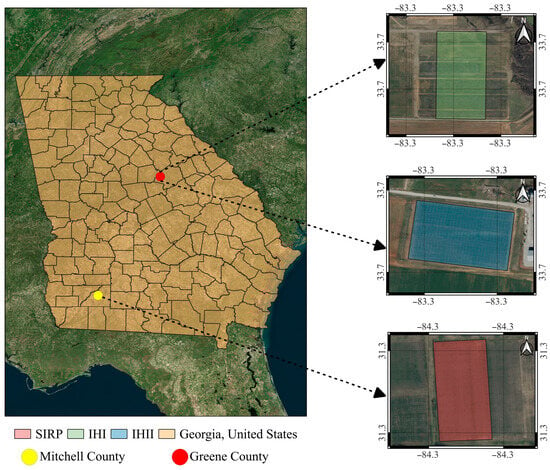

The data collection occurred at three different fields located across Georgia, USA (Figure 1). Field one was located at the Stripling Irrigation Research Park (SIRP) in Mitchell County, Georgia. Fields two and three were located at the Iron Horse Plant Sciences Research Farm, called Iron Horse I (IHI) and Iron Horse II (IHII), located in Greene County, Georgia. The fields presented different soil types and textures. The IHII presents the characteristics of Chewacla (ChA) silt loam, 0 to 2 percent slopes, frequently flooded, and Wickham sandy loam (WkB), 2 to 6 percent slopes, rarely flooded. On the other hand, the IHI has the soil characteristics of Wickham sandy loam (WkB), 2 to 6 percent slopes, rarely flooded, and the SIRP field has Lucy loamy sandy (LmB) soils, 0 to 5 percent slopes, according to the Natural Resources Conservation Services (NRCS) Web Soil Survey (https://websoilsurvey.nrcs.usda.gov/app/) (accessed on 05 August 2025).

Figure 1.

Location map showing the Stripling Irrigation Research Park (SIRP) field site in Mitchell County, GA (red polygon), and Iron Horse I (IHI) (blue polygon) and Iron Horse II (IHII) (green polygon) sites in Greene County, GA, United States. The yellow and red points in the Georgia map (orange) represent the location of the farms in Mitchell and Greene Counties, respectively.

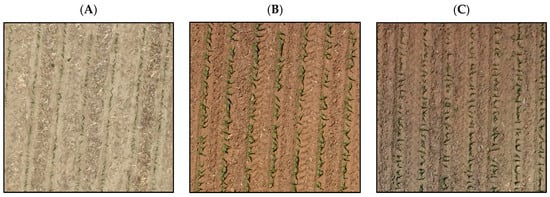

All three fields were planted with corn in 2024. At the SIRP location, corn was planted on 8 April 2024, followed by IHI on 2 May 2024, and IHII on 15 May 2024. The tillage systems varied by field. A no-tillage system was used at SIRP (Figure 2A), while IHI and IHII used a conventional tillage system. However, the IHI presents red-brown soil color (Figure 2B), while IHII has a gray/red-brown soil color (Figure 2C). The soil background was one of the key features used to train the deep learning model. Elements like straw and stones in the background can oftentimes present similar shapes and colors as the crop canopy and can affect the model’s performance. These visual similarities can either improve the model’s capabilities by making the training process more complex by introducing challenges in distinguishing between plants and backgrounds.

Figure 2.

Field images taken at 30 m flight height at the V3 corn growth stage showing the no-tillage field located in Stripling Irrigation Research Park (SIRP) in Mitchell County, GA (A), the red-brown field located in Iron Horse I (IHI) at Greene County, GA (B), and the gray/red-brown soil for Iron Horse II (IHII) located in Greene County, GA (C).

The corn hybrid used for SIRP and Iron Horse I was DKC68-78SS, while at Iron Horse II was the Integra 6641 Bayer SmartStax. The plant population adopted for SIRP and Iron Horse I was 74,000 plants, while at the Iron Horse field, the plant population was 75,000 plants per hectare. Row spacing of 0.75 m was used for Iron Horse I and Iron Horse II, and 0.90 m for SIRP.

2.2. Corn Stages

Determining the corn phenology stages depends on the weather, soil, and management conditions. Thus, the present study used the crop phenology scale developed by Ritchie and Hannway [25] and split the stages for data collection in V2, V3, V5, and V6. Each of these labels represents the vegetative stage, followed by the number of completely open leaves. For a leaf to be considered “completely open”, the leaf must present a visible collar [25,26]. Since the field conditions and sowing dates of each field were different, growth stages were monitored, and fully open leaves were manually counted to ensure that imagery of each field was collected at the same crop growth stage.

2.3. UAV Flights and Parameters

The image collection started at V2, followed by V3, V5, and V6 for every field. The V4 stage was skipped due to adverse weather conditions, which prevented image collection during this period. The UAV used was the DJI® Mavic 3M (Shenzhen, Guangdong, China), which contains five different sensors, including a 20-MP RGB sensor with a maximum resolution of 5280 × 3956 pixels, and a multispectral sensor subdivided into four sensors, Red (650 nm), Green (560 nm), Red-edge (730 nm) and near-infrared (860 nm) with 5-MP and maximum resolution of 2592 × 1944 pixels. Despite the DJI Mavic 3M having a multispectral sensor, the RGB images were selected for this study due to their higher spatial resolution. In addition, RGB sensors require simpler processing and are more affordable, which increases the developed model’s applications for growers.

The flight heights used for all fields were 30 and 70 m, and the overlap during the collection was 80% for both front and side overlap. The flight heights were selected to evaluate the performance of the corn plant-counting model while balancing detection accuracy with the speed and efficiency required for large-scale data collection [4,13,27]. All flights were performed within 2 h of solar noon between 11:00 and 15:00, only on completely sunny conditions, without the presence of clouds over the target fields.

2.4. Dataset Preparation

The dataset preparation process included labeling and data augmentation. Initially, ten random images were selected, then cropped to a size of 640 × 640 pixels. From these, a total of 1920 images were generated for each corn growth stage (V2, V3, V5, and V6) at both 30 m and 70 m flight height. The dataset was organized by field location, flight height, and corn stage. Using the Roboflow® tool (Des Moines, IA, USA), the images were annotated with bounding boxes, marking 50 plants per image, resulting in a total of 96,000 annotated instances across all corn phenology stages. The dataset was then split into training (70%), testing (20%), and validation (10%) datasets. For the training set, data augmentation techniques such as brightness adjustment, rotation, and contrast variation were applied to increase image variability. Finally, the dataset was exported into the data.yaml format for use in model training.

2.5. You Only Look Once (YOLO) Model

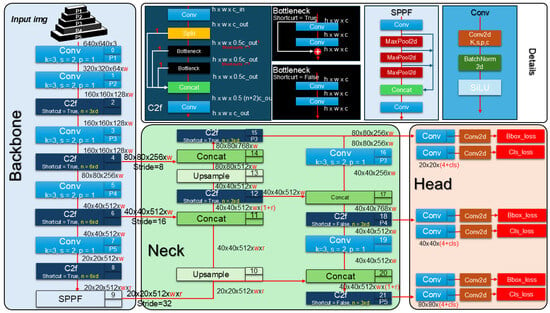

Deep learning models have been frequently applied for object detection tasks. These models present different characteristics, performance, and architecture that can contribute to the object detection task. You Only Look Once models (Figure 3) represent one family of one-shot models with high speed and accuracy in detecting objects [16,22]. The one-shot model, such as YOLO, works by dividing the image into small grids and making predictions in each grid [16,22]. This process is different from conventional convolutional neural networks (CNNs) that present heavy training and test steps. Thus, lightweight models such as YOLO can be applied to camera sensors and smartphones, highlighting their efficiency and enhancing the model’s capability for real-time applications on limited devices [22,28,29].

Figure 3.

You Only Look Once (Yolo) version 9 architecture model used to train, validate, and test the different soil background colors. The network consists of three main components: Backbone (blue), Neck (green), and Head (red). The Backbone extracts hierarchical features at multiple scales (P1–P5) through successive Conv and C2f blocks. The Neck implements a Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) combined with a Path Aggregation Network (PAN) to fuse multi-scale features via Upsample and Concat operations. The Head performs bounding box regression (Bbox_loss) and classification (Cls_loss) at three detection scales: P3 (80 × 80, stride 8), P4 (40 × 40, stride 16), and P5 (20 × 20, stride 32), enabling detection of small, medium, and large objects, respectively. Conv: Convolution block comprising Conv2d, BatchNorm2d, and SiLU activation; Conv2d: two-dimensional convolution operation parameterized by k (kernel size), s (stride), p (padding), and c (number of output channels); C2f: Cross Stage Partial block with two convolutions and n Bottleneck modules. Bottleneck: residual block with optional shortcut connection. SPPF: Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fast module for multi-scale receptive field aggregation. MaxPool2d: max pooling operation with 5 × 5 kernel applied sequentially within SPPF to capture contextual information at multiple scales without increasing computational cost. Concat: channel-wise concatenation operation that merges feature maps from different layers along the channel dimension to combine semantic and spatial information. Upsample: bilinear interpolation for spatial upsampling. For YOLOv8-small, the depth multiplier is 0.33, and the width multiplier is 0.50. Notation: h × w × c denotes height × width × channels. w: indicates the width scaling factor applied to the number of channels. d: indicates the depth scaling factor determining the number of repeated blocks. r: denotes the channel expansion ratio used in the Neck to adjust feature map dimensions after concatenation operations. The shortcuts at C2f represent the bottleneck layers (black box), with the option to use true or false in the shortcut to regulate the function.

The YOLO model has different variations from the original model. In the present study, the YOLOv9-small was selected and used to train each dataset. This model presents the PGI and GELAN functions. Both techniques increase model performance and avoid the information bottlenecks, where features can be lost as data propagate through deep network layers [21,30]. The implementation of YOLO v9 follows the Roboflow® tool (Des Moines, IA, USA) API model. The number of epochs used to train the model was 500 epochs. However, the patience parameter was set to 70 epochs, meaning that if the model did not detect any changes in the loss values in the training step after 70 epochs, it would be stopped. The image size input used was 640 × 640 pixels, the batch size was 8 images, and the number of data workers was 8. The optimizer SGD (Stochastic Gradient Descendent) was used to train the model with a learning rate starting at 0.001 and reaching the best at 0.0168 and a momentum of 0.5. The parameters were selected following the limitations imposed for the small video plate used in the present study. To adapt YOLOv9-small to the specific characteristics of the UAV imagery, a hyperparameter tuning was performed using the Ultralytics Tuner v8.3.239 (Ultralytics, Frederick, MD, USA). This procedure implements an evolutionary search over optimization and data-augmentation hyperparameters, including initial learning rate, learning-rate decay, loss weights, and mosaic/scale/color jitter probabilities. In each iteration, a candidate set of hyperparameters is obtained by mutating the best configuration found. A YOLOv9-small model is trained on the dataset for a reduced number of epochs, and a composite fitness score based on the validation dataset computes the precision, recall, and mAP. The process is repeated for multiple iterations, and the configuration with the highest fitness is stored in a best_hyperparameters.yaml file, which is then used to train the final YOLOv9-small model.

2.6. Performance Metrics

The metrics used to assess the model’s performance in each dataset were the mean average precision of 50% (mAP50) (Equation (1)) and 50–95% (mAP50–95) (Equation (2)), followed by Precision (Equation (3)) and Recall (Equation (4)). The results from each model were also compared using the confusion matrix, comparing the true positive, negative, and false positive and negative.

mAP50 represents the mean average precision of intersection over union 50% (IoU 50%). N refers to the number of samples, and AP represents the average precision values.

mAP50-95 represents the mean average precision of intersection over union between 50% to 95% representing a IoU 75%. N refers to the number of samples, and AP represents the average precision values.

Precision refers to the proportion of correct detections made by the model over all detections made by the model. TP represents the true positives; FP represents the false positives.

Recall represents the proportion of correct objects detected by the model over the total of correct objects in the image or dataset. The FN refers to the false negative samples that were calculated. Nevertheless, the models were evaluated using the Train and Validation Classification Loss (Val_cls_loss and Train_cls_loss). Both metrics represent the model’s performance on validation and training datasets across the epochs used to train the models. After training and validation, the model for each corn growth stage, flight height, and field was implemented in one image to compare the results.

2.7. Video Plate and Software

Large models such as YOLOv9 have a wide number of hyperparameters (7.2 million) that need to be trained. These parameters represent convolutional filters and layers and use many mathematical operations that have a significant time cost. To address this cost, Python 3.12 (Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA) associated with Pytorch (Meta AI, Menlo Park, CA, USA) and CUDA 11.4 were installed before running the model on an NVIDIA GTX 1660 GPU (6 GB) (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA). All the models were analyzed using Python 3.12 and the graphs plotted using the software RStudio 4.3 (Boston, MA, USA).

3. Results

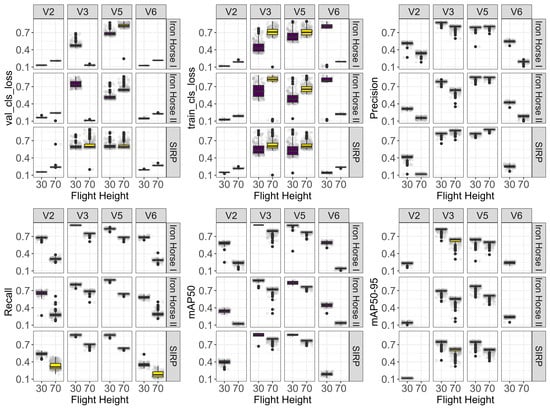

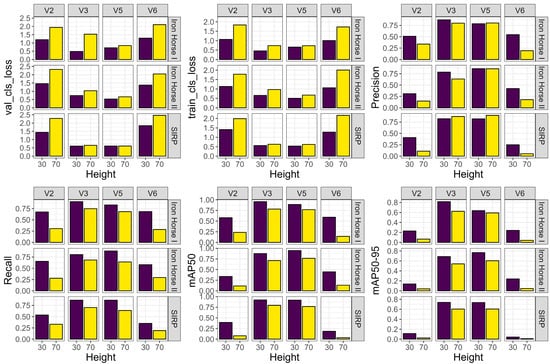

Figure 4 summarizes the training and validation metrics across epochs using box plots. For each metric, the central horizontal line inside the box represents the median value, while the bottom and top edges of the box correspond to the 25th (Q1) and 75th (Q3) percentiles, respectively. The whiskers extend to the minimum and maximum values, and points plotted beyond the whiskers (black dots) are considered outliers. Values closer to the top of the box and whiskers indicate better performance for the corresponding metric (precision, recall, mAP50 and mAP50-95). This representation provides a clear way to visualize the variability of each metric over the training epochs and directly compares the distributions between training and validation sets. The highest variation was observed in the Val_cls_loss and Train_cls_loss metrics. The training and validation classification losses (Val_cls_loss and Train_cls_loss) represent the difference between the true values and those predicted by the model, with lower values indicating better model performance. During the initial stages of training, these values are typically high, but as the model adjusts its weights, the losses decrease. Consequently, higher values can be seen early in training, especially at the V2 and V6 growth stages, which exhibited greater variability compared to V3 and V5, except for val_cls_loss at 70 m for IHII and II. This suggests that, regardless of flight height, the model struggles more to identify plants at the V2 and V6 stages, likely due to difficulty in distinguishing corn plants from the background at V2 and misidentifying individual plants at V6 due to increased leaf overlap between plants. Conversely, the model demonstrated a more consistent performance for Precision and Recall at V3 and V5, regardless of background conditions. This indicates that for these two stages, both 30- and 70 m flight heights yielded similar results in terms of Precision and Recall. However, when analyzing mAP50 and mAP50–95, the model showed significantly higher reliability at the 30 m flight height, highlighting its superior performance.

Figure 4.

Boxplot analysis comparing the training and validation model metrics variability for classification losses (Train_cls_loss and Val_cls_loss), mean average of 50 and 50–95 (mAP50 and mAP 50–95), Precision, and Recall (primary y-axis) at 30- and 70 m flight heights (primary x-axis) for the Stripling Irrigation Research Park (SIRP), Iron Horse I (IHI) and Iron Horse II (IHII) fields (secondary y-axis) at different growth stages (secondary x-axis).

The initial results revealed the mean values obtained for each corn growth stage at different flight altitudes and across various fields (Figure 5). In all cases, the 30 m flight height outperformed the 70 m height. Notably, the V3 and V5 growth stages consistently showed the highest detection performance, even when the background varied between fields. This trend was also reflected in the Precision, Recall, mAP50, and mAP50–95 metrics. At 70 m, the mAP50 values for the V2 and V6 stages were the lowest. However, at 30 m, these values nearly doubled, increasing from 0.25 to 0.50. Although mAP50 values improved with the lower flight height, the mAP50–95 values for V2 and V6 decreased to approximately 0.2, indicating limited model effectiveness in detecting these stages. Furthermore, while Precision and Recall were highest for the V3 and V5 stages, performance still varied by location, with IHI achieving the best results and the SIRP field showing the lowest.

Figure 5.

Bar graphics results comparing the models’ mean values for the metrics training and validation classification losses (Train_cls_loss and Val_cls_loss), mean average of 50 and 50–95 (mAP50 and mAP 50–95), Precision and Recall (primary y-axis) at 30- and 70 m flight heights represented by the purple and yellow color bars for the Stripling Irrigation Research Park (SIRP), Iron Horse I (IHI) and Iron Horse II (IHII) fields (secondary y-axis) at different growth stages (secondary x-axis).

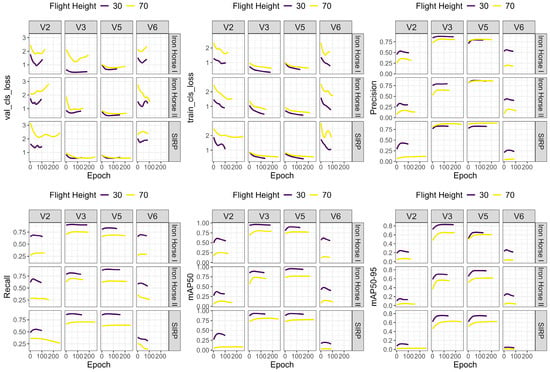

Figure 6 supports the results obtained using YOLOv9-small for detecting corn plants across different growth stages, flight heights, and backgrounds. The most detectable stages, V3 and V5, showed variability in the number of epochs required to train the model. At the lowest flight height (30 m), the model converged more quickly, as indicated by lower initial loss values and a reduced number of training epochs. In contrast, the SIRP field required nearly 300 epochs for model convergence at 70 m, and this setting also resulted in the highest Val_cls_loss values. Correspondingly, the 70 m flight height yielded the lowest performance in mAP50, mAP50–95, and Recall across all growth stages. With the exception of SIRP (V3 and V5), IHI (V5), and IHII (V5), the 70 m flight height generally resulted in higher Precision values. Precision measures the accuracy of model predictions, indicating how many predicted objects are correct. Therefore, at V3 and V5, in complex backgrounds like at the SIRP field or at IHI and IHII fields, the 70 m flight may offer more accurate predictions. However, when analyzing the Recall metric, the 30 m flight height consistently produced better results. This indicates that although the model detected objects at 70 m, many were likely false positives, as evidenced by the lower Recall scores. Recall reflects how well the model detects all objects in the image. Thus, high Recall means fewer missed detections, which is expected from images with higher spatial resolution.

Figure 6.

Smooth line graphics results comparing the metrics for training and validation classification losses (Train_cls_loss and Val_cls_loss), mean average of 50 and 50–95 (mAP50 and mAP 50–95), Precision and Recall (primary y-axis) at 30- and 70 m flight heights and the number of epochs (primary x-axis) for the Stripling Irrigation Research Park (SIRP), Iron Horse I (IHI), and Iron Horse II (IHII) fields (secondary y-axis) at different growth stages (secondary x-axis).

The interaction between background, corn growth stages, and flight height was further analyzed using the confusion matrix (Figure 7). The confusion matrix was used to understand the misclassification of the corn growth stages and flight height. The X-axis represents the true label, i.e., the real label created manually, while the Y-axis represents the predicted label, i.e., the label created by the model. Thus, the true negative (top-left cell) is the background, correctly classified as background, while the true positive (bottom-right cell) is the plants correctly classified as plants. The false positive (top-right cell) represents the true background (x-axis) predicted as a plant (Y-axis), while the false negative (bottom-left cell) represents the corn plants the model failed to detect.

Figure 7.

Confusion Matrix used to evaluate the model’s performance at different corn growth stages (V2, V3, V5, and V6) and flight height (30 and 70 m). The primary y-axis represents the predicted values by the model, and the x-axis represents the observed values (True), while the secondary x-axis represents the flight height (30 and 70 m).

At the V2 growth stage with a 30 m flight height, 67% of background pixels were misclassified as corn at V2. This misclassification rate was also observed at the field level, with 44%, 51%, and 51% of predictions being incorrectly identified as corn for SIRP, IHI, and IHII, respectively. However, when using the 70 m flight height at the same V2 stage, the misclassification significantly increased, especially at the SIRP and IHII fields, where 95% and 51% V2 corn plants were misclassified as background, respectively.

The confusion matrix also highlighted the highest model performance at 30 m for the following combinations: SIRP field at the V5 stage, IHI at V3, and IHII at V5. These results indicate the V3 and V5 stages as more favorable for accurate plant count. Nonetheless, even at the most suitable stages, increasing flight height can lead to a decrease in model performance. The SIRP field, for example, which features a no-tillage background, an increase in flight height to 70 m resulted in a 26% decrease in model accuracy for detecting the V5 growth stage. Other results showed that flying the UAV at 70 m can reduce accuracy by approximately 24% to 36% depending on background conditions.

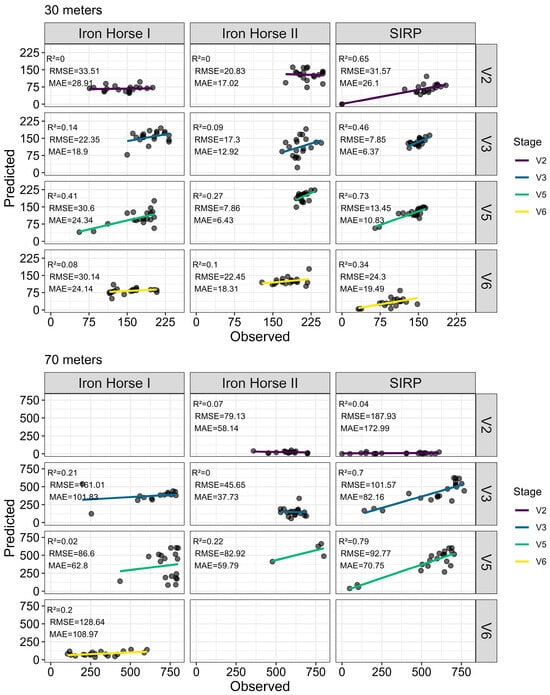

Model validation was also performed on 20 images collected from each field (Figure 8). The 70 m flight height presented no successful detections for the V2 growth stage at IHI and for V6 at the SIRP and IHII fields. Additionally, the best performance on the validation dataset was observed for V5 at both 30 and 70 m, reaching R2 values of 0.73 and 0.79 with errors varying between 18 plants for 30 m to 168 plants for 70 m at the SIRP field. IHI presented the best performance for V5 at 30 m with R2 0.41 and an error of 75 and 68 plants for RMSE and MAE, respectively. IHII showed the worst performance with a maximum R2 of 0.27 found at the V5 corn stage for 30 m and an error of 21 and 15 plants for RMSE and MAE.

Figure 8.

Scatter plots comparing observed (manual counting) (primary x-axis) versus predicted (YOLOv9s model) corn plant counts (primary y-axis) across three experimental fields: Iron Horse I, Iron Horse II, and Stripling Irrigation Research Park (SIRP) (secondary x-axis). Results are presented for two unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) flight altitudes (30 and 70 m) and four corn growth stages (V2, V3, V5, and V6) (secondary y-axis). Each panel displays the coefficient of determination (R2), root mean square error (RMSE), and mean absolute error (MAE). Colored lines represent linear regression fits for each growth stage. Missing panels at 70 m indicate combinations where data acquisition was not performed or model predictions were not feasible due to image resolution constraints.

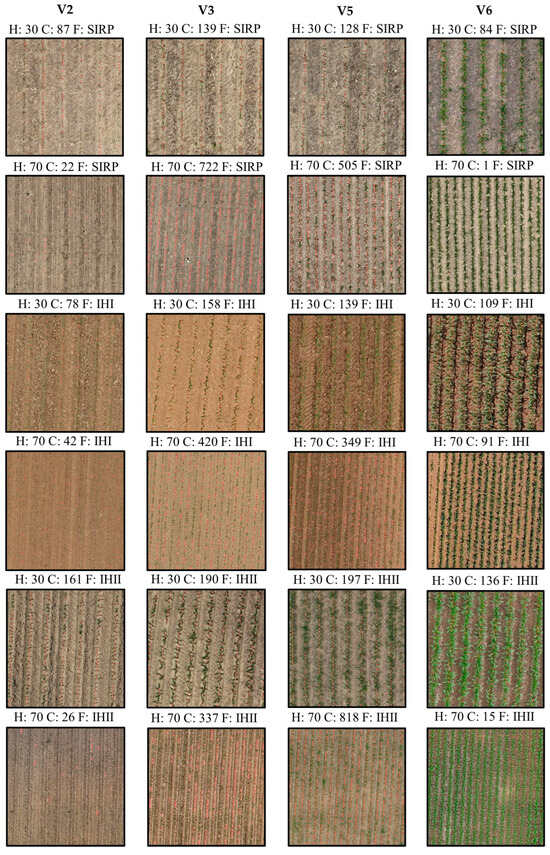

The models’ performance can also be observed in Figure 9, in which the number of counted plants for V3 and V5 stages, represented by the red dots, is shown for 30- and 70 m flight heights. The comparison results across all stages and field conditions validate that soil contrast represents one of the most important factors influencing model accuracy, especially at a flight height of 70 m. At this height, if the soil–plant contrast, caused by the soil color background, was high, the model accurately counted the corn plants, as observed for IHII, V5 stage, where 818 corn plants were identified, and for SIRP, V3 stage, in which 722 corn plants were identified. Soil color is another important factor. Gray soils or dark-hue conditions led to better detection performance for YOLOv9-small model, even for higher flights, such as at 70 m, highlighting the model’s feasibility for larger-scale field mapping.

Figure 9.

Prediction results using the training model for each flight height, field, and corn growth stage. H—height (meters); C—corn plant count; F—field location. SIRP—Stripling Irrigation Research Park; IHI—Iron Horse I; IHII—Iron Horse II.

4. Discussion

The first hypothesis states that corn plants with three or more fully developed leaves provide more favorable conditions for accurate object detection, regardless of background, whereas earlier stages with fewer than three fully developed leaves are associated with higher misclassification due to greater visual similarity with the background. This pattern can be explained by the observed interaction between flight height and background conditions. Corn development begins at emergence (VE) and progresses through vegetative (Vn) and reproductive (Rn) stages. The V1 stage, characterized by one fully open leaf, represents one of the earliest growth stages, where the cotyledonary leaf is still predominant. With each accumulation of approximately 66 growing degree days, the corn plant develops a new leaf [26]. By the time the plant reaches V3, its lower leaves are larger and more structurally defined, making them easier for detection models to identify from higher flight altitudes. At the V2 stage, the smaller leaf size and denser background, particularly in no-tillage systems, reduce detection accuracy, even at lower flight heights such as 30 m. In no-tillage systems, such as the SIRP field, the background interference is a major challenge for early-stage detection. However, contrasting soil characteristics can influence model performance. In fields like IHII, where light to dark-gray soil colors enhance visual contrast between plants and background, detection accuracy is high, even at the 70 m flight height. This suggests that soil color and texture play a role in optimizing detection outcomes. Overall, the transition stages between V3–V4 and V5–V6 are the most effective for corn stand counting and detection, regardless of background or flight height [31,32]. In a study evaluating different backgrounds, flight heights, and model types for corn density estimation, Jia et al. [3] found that a flight height of 20 m yielded the best performance. However, such low altitudes have trade-offs, including increased data acquisition time and larger data volumes for processing.

Following the second hypothesis, lower UAV flight altitudes (30 m) resulted in higher corn plant detection accuracy across growth stages, particularly V3 and V5, by reducing background influence and enhancing model convergence. It was observed that the higher resolution increases the model performance in detecting the corn plants, mainly at the V3 and V5 stages, while also decreasing the time for convergence. This means that a lower flight height does not necessarily need powerful models with high hyperparameters and complex layers, i.e., the high resolution contributed to models’ performance with the highest mAP50, mAP50–95, Precision, and Recall [3,10,31]. Conversely, increased flight heights (70 m) allow for faster field mapping, but more powerful models with higher parameters are required to detect subtle differences in the background. These findings align with those observed by Pang et al. [33] that at a flight height of 30 m, the Mask-CNN model exhibited 87% accuracy, and when changed to heights of 40, 50, and 60 m, the average precision dropped to 79.4%, 75.5%, and 68.1%, respectively. Although lower flight heights improve model training efficiency and performance, allowing the use of small models, the applications for large-scale fields remain a limitation. Higher flight heights, as presented in this study, facilitate faster decision-making by the farmers, with reduced processing time and storage, unlike other studies [3,10,31], which, despite achieving higher performance, have limited applicability in large-scale fields.

YOLO models have significantly transformed one-stage object detection tasks, offering a balance between speed and accuracy that contrasts with more complex models such as Mask R-CNN and Faster R-CNN. While these two-stage detectors often achieve higher accuracy, their implementation is limited due to the large number of hyperparameters and high computational demand. In this study, YOLOv9-small was evaluated for its effectiveness in corn detection tasks, introducing two innovative architectural components: PGI and the GELAN. PGI helps preserve gradient flow across layers, minimizing information loss during training, while GELAN efficiently aggregates features using multiple computational blocks, including CSPBlocks, ResBlocks, and DarkBlocks, ensuring effective multiscale feature extraction and representation [20]. This efficiency has been demonstrated in other applications, with YOLOv9 achieving up to 94% mAP50 in coffee plant detection using various sensors [34,35]. Previous research with Mask R-CNN on corn at the V4–V5 stage and 30 m flight height also reported high performance (mAP50 = 94%), while segmentation models such as U-Net achieved Recall and Precision values of 0.95 and 0.96 at ultra-low flight heights of 10 m [4]. Similarly, Lu et al. [34] reported mAP50 values of 82% at the V3 stage and 86.3% at V7 using YOLOv5 at 12 m. Under conditions of high weed infestation, improved YOLOv5 models reached mAP50 scores of 93% and 89% at 15 and 30 m, respectively [33]. However, what distinguishes the present study is the ability to achieve high performance metrics (85% mAP50, Precision, and Recall) even at a flight height of 70 m, using a lightweight model like YOLOv9-small, as observed for the fast convergence in initial stages (Figure 6). This is a significant advancement, as most previous studies relied on either more complex models or lower flight altitudes to obtain similar results. Moreover, the use of RGB cameras in this study underscores the practical and cost-effective nature of the approach. Unlike multispectral or modified sensors, which are expensive and require specialized expertise, RGB cameras are affordable, user-friendly, and easily integrated into UAV systems. This makes the proposed method highly suitable for scalable, real-world agricultural applications.

YOLOv9 achieved high accuracy at both corn growth stages (V3 and V5), and its performance in this study is consistent with results reported in the literature for agricultural applications. Wang et al. [32] reported high precision and mAP scores (precision = 89.30%, mAP0.5 = 94.60%, mAP0.5–0.95 = 64.60%) when comparing YOLOv5, YOLOv7, and YOLOv8 for coffee detection and counting. Additionally, Sharma et al. [36] showed that YOLOv9 outperforms YOLOv11, YOLOv10, YOLOv8, and Faster R-CNN in terms of mAP0.5, mAP0.5–0.95, precision, and recall, although at the cost of longer inference time. Similarly, in an orchard scenario using ground-based cameras for apple fruit detection and counting, Sapkota et al. [16] reported that YOLOv9-GELAN-E achieved higher mAP0.5 than YOLOv10, YOLOv8, YOLOv11, and YOLOv12 and obtained precision (0.903 versus 0.908) and recall (0.899 versus 0.900) values comparable to YOLOv10x and YOLOv12l, while YOLOv12 was approximately three times faster in terms of inference speed. Overall, these studies indicate that agricultural tasks require fast, real-time, and robust object detection, demanding models that balance accuracy and speed, as is characteristic of the YOLO family [37]. At the same time, agricultural environments involve substantial field variability and therefore require large, diverse datasets and careful fine-tuning. This was also observed in the present study, despite the high precision and recall achieved by YOLOv9-small. Its higher latency and lower inference speed may limit its applicability in strict real-time conditions, especially for autonomous robotics or UAV-based imagery. Thus, modified versions using improved functions [38,39,40], different optimizers [27], and adding transfer learning [15,41] or pre-processing steps [15] could be a solution to creating powerful models with a balance between precision, accuracy and hardware requirements.

Limitations and Future Research

This study investigated the influence of flight height and field background on the accuracy of counting corn plants at different growth stages using a YOLO-based object detection model. While this study tested a higher flight height to increase the scalability of plant stand count to larger fields, limitations remain when applying these models to very large commercial crop fields at early growth stages. Results showed a lower plant stand count accuracy in the very early stages of corn development (V2). Acquiring additional training data, focused specifically on early corn growth stages, combined with lower flight altitudes, can enhance YOLO performance and support early field decisions. Nonetheless, UAV operational constraints, such as limited battery life, flight time, and legal restrictions, create a trade-off between flight height, ground sampling distance, and field coverage. Another limitation is related to the cost of hardware and software needed to perform this task. This work focused on using compact models, such as YOLOv9-small, which allow large numbers of image tiles to be processed with moderate computational resources. Future work exploring edge computing, local farm servers, and model compression strategies to reduce inference time and hardware requirements could further improve plant count accuracy.

Environmental factors such as wind, dust, crop residue, and heterogeneous soil moisture can also degrade image quality and lead to missed or false detections, reinforcing the need for multi-temporal acquisitions, UAV image quality control, and fine-tuning with field-specific data. The data used in this study focused on comparing the model’s accuracy at different soil background colors. However, the soil background color was used only as a visual reference. Future studies considering the soil color histogram or classification under controlled conditions, while also measuring the residues and brightness, might add valuable information for the model’s performance.

It is worth noting that the light-hue soil colors can challenge the model in recognizing patterns and counting plants, sometimes reducing confidence values to less than 0.1 [42,43]. Another approach would be to increase the dataset with images reflecting field variability, especially in no-till and gray/red-brown colors, which can contribute to model optimization. A third approach would be to apply different augmentation strategies or generative approaches, such as Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), to expand the dataset and simulate diverse environments considering soil background colors. Additionally, large datasets that include soil moisture, different illumination levels, brightness, soil background color, and a no-tillage system could support the training of highly robust and accurate models.

Models that account for the overlap between the leaves and the dense canopy at the V6 corn growth stage, combining YOLO-based and segmentation models, could be a feasible application to enhance the model’s performance at high flight heights. Although heavier models often achieve higher accuracy, their deployment using affordable devices remains challenging due to their large size, increasing the cost of developing the hardware and software and limiting their use in large-scale field applications. Thus, creating efficient models and hardware can help support extension professionals, growers, consultants, and other stakeholders to make confident, data-driven management decisions by monitoring the field variability and crop development.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that both background conditions and flight height affect object detection performance in corn. The highest model accuracy was observed at stages V3 and V5, with mAP50 = 0.85, mAP50–95 = 0.75, and Precision and Recall near 0.80, highlighting the strong potential for early-stage detection. Performance was low at the V2 stage due to small plant size and background interference, and at V6 due to leaf overlap. Complex backgrounds in no-tillage fields reduced the model’s accuracy, while red-brown soils enhanced contrast and improved model performance. Lower flight heights enabled effective detection even with lightweight models, whereas higher altitudes (70 m) reduced detection at V2 and V6, indicating the need for more advanced models under these conditions.

From an operational perspective, these results highlight a clear trade-off between spatial resolution, model complexity, and field coverage. Low-altitude flights are more preferable when precise per-plant counts are required in sample plots, whereas higher altitudes are more suitable for large-scale monitoring of intermediate growth stages, where timely decisions and reduced data volume are priorities. The study also has limitations that suggest directions for future research. Soil background was treated as a visual reference in RGB imagery, and detailed soil properties (standardized color scales, residue cover, structure, and moisture) were not measured systematically. Future work should combine UAV imagery with in situ measurements of soil and residue properties, expand the dataset to include a wider range of soil backgrounds, illumination conditions, and no-tillage systems, and explore advanced augmentation or generative approaches (such as GANs) to better represent challenging backgrounds and early growth stages.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.N.L. and A.F.d.S.; methodology, T.O.C.B., L.N.L. and A.F.d.S.; software, T.O.C.B.; validation, E.K.B., L.N.L. and A.F.d.S.; formal analysis, T.O.C.B.; investigation, T.O.C.B. and L.N.L.; resources, L.N.L., A.F.d.S. and G.V.; data curation, T.O.C.B., E.K.B., L.N.L. and A.F.d.S.; writing—original draft preparation, T.O.C.B. and L.N.L.; writing—review and editing, L.N.L., A.F.d.S., E.K.B. and G.V.; visualization, T.O.C.B. and L.N.L.; supervision, L.N.L.; project administration, A.F.d.S. and L.N.L.; funding acquisition, L.N.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Georgia Commodity Commission for Corn grant number [CR2409] and by the USDA Foreign Agricultural Service grant number [6000028574].

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the following Brazilian agencies: National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education (CAPES), Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG). Also, the authors acknowledge and thank the University of Georgia for its support during the project development and the Lacerda Research Group (LRG) for its support during the data collection and processing. The authors extend the acknowledgments to the Extension and Research Group in Digital Agriculture (GEPAD) undergraduate students from Federal University of Lavras (UFLA) for the labor-intensive label creation process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IHI | Iron Horse I |

| IHII | Iron Horse II |

| SIRP | Stripling Irrigation Research Park |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

References

- United States Department of Agriculture. Corn Explorer; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2025.

- Tang, B.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, C.; Pan, Y.; Lu, Y.; Liu, C.; Ma, K.; Sun, X.; Zhang, R.; Gu, X. Using UAV-based multispectral images and CGS-YOLO algorithm to distinguish maize seeding from weed. Artif. Intell. Agric. 2025, 15, 162–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Fu, K.; Lan, H.; Wang, X.; Su, Z. Maize tassel detection with CA-YOLO for UAV images in complex field environments. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 217, 108562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vong, C.H.; Conway, L.S.; Zhou, J.; Kitchen, N.R.; Sudduth, K.A. Early corn stand count of different cropping systems using UAV-imagery and deep learning. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 186, 106214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangoi, L. Understanding plant density effects on maize growth and development: An important issue to maximize grain yield. Ciência Rural 2001, 31, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, J.A.; Nafziger, E.D.; Abendroth, L.J.; Thomison, P.R.; Elmore, R.W.; Zarnstorff, M.E. Agronomic responses of corn to stand reduction at vegetative growth stages. Agron. J. 2011, 103, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanger, T.F.; Lauer, J.G. Optimum plant population of Bt and non-Bt corn in Wisconsin. Agron. J. 2006, 98, 914–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roekel, R.J.V.; Coulter, J.A. Agronomic Responses of Corn to Planting Date and Plant Density. Agron. J. 2011, 103, 1464–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, E.E.; Baio, F.H.R.; Kolling, D.F.; Júnior, R.S.; Zanin, A.R.A.; Neves, D.C.; Fontoura, J.V.P.F.; Teodoro, P.E. Variable-rate in corn sowing for maximizing grain yield. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitano, B.T.; Mendes, C.T.; Geus, A.R.; Oliveira, H.C.; Souza, J.R. Corn Plant Counting Using Deep Learning and UAV Images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2019, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xiang, L.; Tang, L.; Jiang, H. A Convolutional Neural Network-Based Method for Corn Stand Counting in the Field. Sensors 2021, 21, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Kayacan, E.; Thompson, B.; Chowdhary, G. High precision control and deep learning-based corn stand counting algorithms for agricultural robots. Auton. Robot. 2020, 44, 1289–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, M.; Hu, J.; Wang, J.; Shu, M.; Liu, Y.; Guo, W.; Qiao, H.; Niu, Q.; et al. Mapping Maize Planting Densities Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, Multispectral Remote Sensing, and Deep Learning Technology. Drones 2024, 8, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, M. What Is YOLOV9: An In-Depth Exploration of the Internal Features of the Next-Generation Object Detector. In Computer Science, Computer Vision and Pattern Recognizition; Cornell University: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Akdogan, C.; Ozer, T.; Oguz, Y. PP-YOLO: Deep learning based detection model to detect apple and cherry trees in orchard based on Histogram and Wavelet preprocessing techniques. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 232, 110052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, R.; Meng, Z.; Churuvija, M.; Du, X.; Mab, Z.; Karkee, M. Comprehensive Performance Evaluation of YOLOv12, YOLO11, YOLOv10, YOLOv9 and YOLOv8 on Detecting and Counting Fruitlet in Complex Orchard Environments. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2407.12040. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Yeh, I.; Liao, H.M. YOLOv9: Learning What You Want to Learn Using Programmable Gradient Information. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.13616. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Ye, Q.; Doermann, D. YOLOv12: Attention-Centric Real-Time Object Detectors. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.12524. [Google Scholar]

- Alif, M.A.R.; Hussain, M. Yolov1 to Yolov10: A Comprehensive Review of Yolo Variants and Their Application in the Agricultural Domain. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.10139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, A.; Vairavasundaram, S. YOLO-based Object Detection Models: A Review and its Applications. Multimed Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 83535–83574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Bagavathiannan, M.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yu, J. A comparative evaluation of convolutional neural networks, training image sizes, and deep learning optimizers for weed detection in alfalfa. Weed Technol. 2023, 36, 512–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhou, J.; Costa, M.; Kaeppler, S.M.; Zhang, Z. Plot-Level Maize Early Stage Stand Counting and Spacing Detection Using Advanced Deep Learning Algorithms Based on UAV Imagery. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, S.W.; Hanway, J.J. How a Corn Plant Develops; Iowa State University of Science and Technology, Cooperative Extension Service: Ames, IA, USA, 1982; Special Report No. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X.; Li, A.; Meng, Z.; Yin, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, W.; Qi, L. A Dynamic Detection Method for Phenotyping Pods in a Soybean Population Based on an Improved YOLO-v5 Network. Agronomy 2022, 12, 3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nleya, T.; Chungu, C.; Kleinjan, J. Chapter 5: Corn growth and development. In SDSU Extension Corn: Best Management Practices; South Dakota State University: Brookings, SD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, T.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Song, X.; Yang, G.; Yao, Z.; Wu, W.; Liu, T.; Sun, C.; et al. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle-Scale Weed Segmentation Method Based on Image Analysis Technology for Enhanced Accuracy of Maize Seedling Counting. Agriculture 2024, 14, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.Q.; Zheng, P.; Xu, S.T.; Wu, X. Object Detection with Deep Learning: A Review. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2019, 30, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soviany, P.; Ionescu, R.T. Optimizing the Trade-Off between Single-Stage and Two-Stage Deep Object Detectors using Image Difficulty Prediction. In Proceedings of the 20th International Symposium on Symbolic and Numeric Algorithms for Scientific Computing (SYNASC), Timisoara, Romania, 20–23 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.L.; Zhang, Z. The YOLO Framework: A Comprehensive Review of Evolution, Applications, and Benchmarks in Object Detection. Computers 2024, 13, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Su, W.H.; Wang, X.Q. Quantitative Evaluation of Maize Emergence Using UAV Imagery and Deep Learning. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota-Delfin, C.; López-Canteñs, G.d.J.; López-Cruz, I.L.; Romantchik-Kriuchkova, E.; Olguín-Rojas, J.C. Detection and Counting of Corn Plants in the Presence of Weeds with Convolutional Neural Networks. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 4892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, C.; Qiang, Z.; Liu, C.; Wei, X.; Cheng, F. A Coffee Plant Counting Method Based on Dual-Channel NMS and YOLOv9 Leveraging UAV Multispectral Imaging. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Gao, S.; Jiang, F.; Veeranampalayam-sivakumar, A.; Thompson, L.; Luck, J.; Liu, C. Improved crop row detection with deep neural network for early-season maize stand count in UAV imagery. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 178, 105766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Nnadozie, E.; Camenzind, M.P.; Hu, Y.; Yu, K. Maize plant detection using UAV-based RGB imaging and YOLOv5. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 14, 1274813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, A.; Zhou, J.; Vories, E.; Sudduth, K.A. Evaluation of Cotton Emergence Using UAV-Based Imagery and Deep Learning. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 177, 105711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kumar, V.; Longchamps, L. Comparative performance of YOLOv8, YOLOv9, YOLOv10, YOLOv11 and Faster R-CNN models for detection of multiple weed species. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 9, 100648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badgujar, C.H.; Poulose, A.; Gan, H. Agricultural object detection with You Only Look Once (YOLO) Algorithm: A bibliometric and systematic literature review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 223, 109090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Nie, C.; Wang, H.; Cheng, M.; Liu, S.; Yu, X.; Shao, M.; Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; Tuohuti, N.; et al. A fast and robust method for plant count in sunflower and maize at different seedling stages using high-resolution UAV RGB imagery. Precis. Agric. 2022, 23, 1720–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.; Yan, X.; Yan, W.; Sun, L.; Xu, J.; Yuan, H. Precise extraction of targeted apple tree canopy with YOLO-Fi model for advanced UAV spraying plans. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 226, 109425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, H.H.; Yang, M.D.; Saminathan, R.; Hsu, Y.C.; Yang, C.Y.; Wu, D.H. Rice Seedling Detection in UAV Images Using Transfer Learning and Machine Learning. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulibaly, S.; Foguem, B.K.; Kmissoko, D.; Traore, D. Deep neural networks with transfer learning in millet crop images. Comput. Ind. 2019, 108, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Dong, D.; Jia, X.; Guo, J.; Yu, X. Sugarcane-YOLO: An Improved YOLOv8 Model for Accurate Identification of Sugarcane Seed Sprouts. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Zhang, K.; Zhong, H.; Xie, J.; Xue, X.; Yan, M.; Wu, W.; Li, J. Efficient Tobacco Pest Detection in Complex Environments Using an Enhanced YOLOv8 Model. Agriculture 2024, 14, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.