Highlights

What are the main findings?

- A YOLOv5-based framework enables effective cross-regional detection of old landslides using high-resolution remote sensing imagery.

- A Python–GIS post-processing strategy converts detection outputs into accurately georeferenced landslide shapefiles.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- The proposed approach significantly improves the efficiency and spatial accuracy of large-area old landslide inventories.

- The framework provides a practical and transferable solution for landslide hazard investigation and risk management.

Abstract

Old landslide reactivation poses a significant risk to infrastructure and settlements in mountainous regions. Its identification and accurate localization are crucial for mitigating reactivation hazards, yet are hindered by blurred morphological signatures and vegetation cover. This study develops a cross-regional workflow for the detection and GIS-based localization of old landslides using one-meter-resolution optical imagery and an enhanced YOLOv5 model. The workflow strictly separates training and detecting areas (Wanzhou for training, Zigui for detecting) to simulate realistic, unsurveyed scenarios. A Python script converts model outputs into shapefiles with precise geographic coordinates.. The results show an F1 score of 0.96 in the training area and 0.62 (mAP@0.5 = 0.58, Precision = 0.56, Recall = 0.67) in the detecting area. The analysis identifies causes of cross-regional performance degradation, including geomorphic confusion and potential detection of previously unmapped old landslides. These results demonstrate the feasibility of cross-regional landslide detection and highlight the potential of deep learning–GIS integration for practical hazard management.

1. Introduction

Old (ancient) landslides differ from new (recent) ones by their long history, generally exceeding 100 years [1,2]. They have profoundly shaped surface morphology [3,4], often forming terraces and other characteristic landforms that appear as flat areas widely used for settlement and cultivation in mountainous regions [5]. However, old landslides remain susceptible to reactivation triggered by tectonic movement, extreme rainfall, or human activity [6,7]. Such reactivation can lead to catastrophic losses, as exemplified by the Vajont [8,9] and Abbotsford [10] landslides. Typically, large and deep-seated, old landslides are difficult and costly to stabilize; for example, the Kangjiapo Landslide in the Three Gorges Reservoir area has undergone two remediation efforts yet continues to deform [11]. Therefore, accurately identifying and locating old landslides is crucial for land-use planning, site selection, and risk prevention [12,13,14].

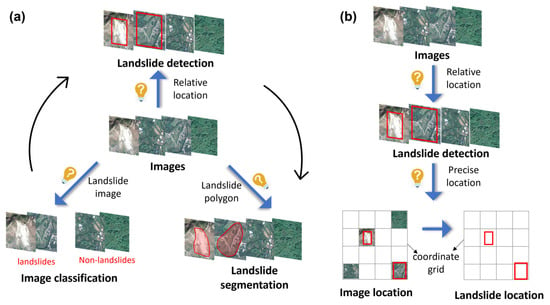

Remote sensing has become a widely adopted tool for landslide investigation due to its efficiency and cost-effectiveness [15,16,17]. Among various techniques, image-based landslide identification (IBLI) and interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR) are the most common [18,19,20]. With recent advances in computer vision, the accuracy and efficiency of IBLI have greatly improved [21,22]. In particular, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have enhanced IBLI performance, achieving accuracies above 75% [23,24,25]. IBLI approaches can generally be categorized into three levels based on output detail [26,27]: image classification, landslide detection, and landslide segmentation. Image classification distinguishes the presence or absence of landslides but cannot determine their number or precise location [22]. Detection provides both the count and approximate positions of landslides, while segmentation offers the most detailed information by outlining their actual shapes and extents. Each level builds upon the previous, offering progressively greater spatial precision for hazard management.

Despite these advances, significant challenges remain before these methods can be effectively applied to old landslide mapping [28,29,30]. Existing studies mainly focus on recent landslides, with limited success in identifying older ones [31,32,33,34]. Unlike new landslides that leave clear morphological evidence, old landslides are often obscured by vegetation, erosion, and human modification [35,36,37]. The resulting low contrast between the landslide body and its surroundings makes them difficult to detect. Previous studies have reported accuracies of only 0.53–0.54 for old landslide detection [38,39], underscoring the need for improvement. One straightforward approach is to employ high-resolution imagery, which enhances the ability to detect subtle morphological differences [21,40,41]. Another critical factor influencing detection accuracy is the input image size used during model training. Small input sizes tend to compress spatial details and often split large old landslides across multiple image patches, thereby disrupting the integrity of geomorphic features. Larger input sizes are more effective in preserving complete landslide morphologies and enhancing the detection of subtle features [42]. However, most existing studies commonly adopt relatively small input sizes ranging from 224 × 224 to 512 × 512 pixels [42,43,44], which are often insufficient to meet the requirements of old landslide detection.

Furthermore, current landslide detection techniques are not fully aligned with real-world applications [45,46]. Two key gaps remain. First, most studies perform both training and validation within the same region, which limits assessment of model generalization to unfamiliar terrain [47,48,49]. In practice, models must detect previously unknown landslides, especially in unsurveyed or “blind” regions [50,51]; same-area testing therefore has limited practical meaning. Second, many studies provide only relative or approximate locations of landslides—sometimes none at all—instead of accurate geographic coordinates [52]. To improve operational value, cross-regional detection and precise GIS-based localization are necessary, enabling not only recognition but also accurate definition of each landslide’s position and extent [44,53].

To address these challenges, this study applies the YOLOv5 (You Only Look Once, version 5) model with large input sizes and one-meter resolution imagery to enhance the precision of old landslide detection. A cross-regional strategy is implemented, where the model is trained in one area and applied to another treated as an unsurveyed region. The resulting detections are then georeferenced and converted into shapefiles containing precise geographic coordinates. This represents a pioneering effort to determine the real-world spatial positions of detected landslides. The Three Gorges Reservoir Region of China, specifically Wanzhou and Zigui Counties, serves as the case study, demonstrating the practical utility of the proposed method for old landslide identification.

2. Methodology

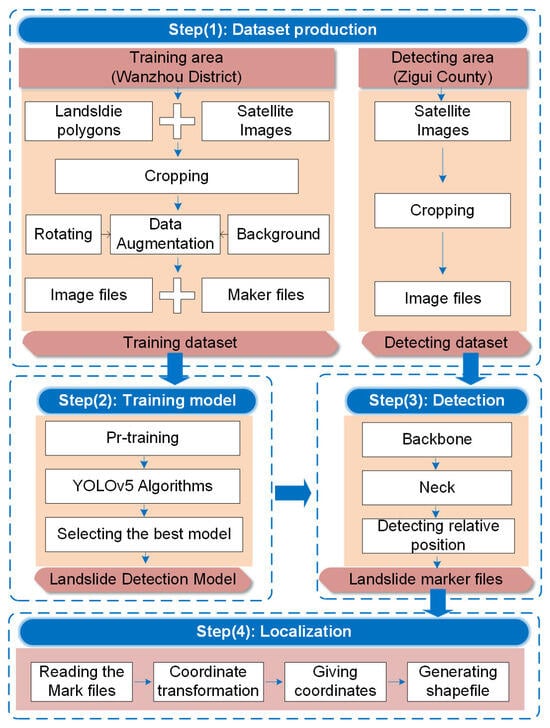

The ultimate goal of landslide recognition is to accurately detect and locate landslides in previously unsurveyed areas. Achieving this requires cross-regional landslide detection and the ability to precisely localize landslides in geographic space. To simulate a cross-regional landslide detection scenario, it is essential to clearly separate the training and detecting areas. This ensures the independence of the training and detection processes, preventing cross-interference. Moreover, the preliminary outputs generated by computer vision techniques must undergo further processing to determine the exact spatial locations of landslides. Accordingly, we developed a four-step framework for the Cross-regional detection and spatial localization of old landslides, as illustrated in Figure 1: (1) Dataset Construction, (2) Model Training, (3) Cross-regional detection, and (4) GIS Localization: The key innovation lies in Steps 3–4, where model outputs are georeferenced to generate shapefiles compatible with GIS.

Figure 1.

Workflow for cross-regional detection and spatial localization of old landslides.

2.1. Dataset Production

In this workflow, the training and detecting areas are clearly distinguished. The training area refers to regions where landslide locations and boundaries have been previously surveyed and identified, and it is used for model development. In contrast, the detecting area simulates unsurveyed regions—areas where no prior knowledge of landslides exists—and is used to evaluate the model’s ability to detect unknown landslides. This setup implies that a complete landslide detection dataset consists of both a training set and a detecting set. The training dataset serves as the input for the deep learning model, while the detecting dataset is used to identify and localize landslides in an independent target area. Consequently, the methods for generating these two datasets, as well as the file structures they involve, differ significantly in order to enhance the practical applicability of landslide detection.

2.1.1. Training Dataset

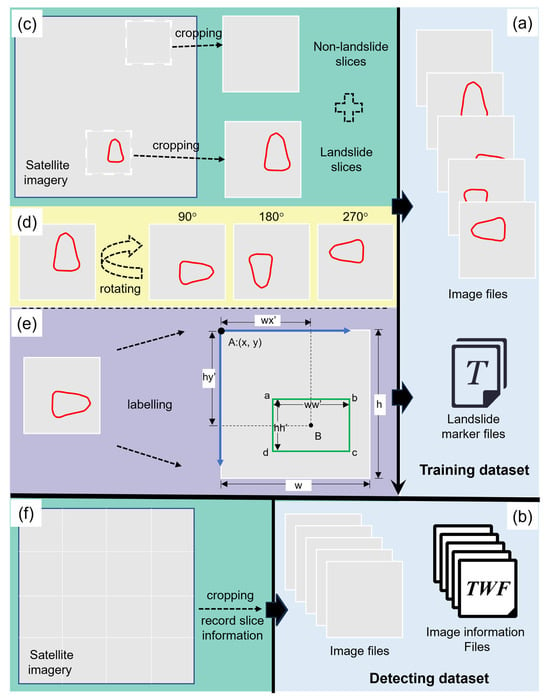

The training dataset consists of image files and landslide marker files (Figure 2a). Initially, remote sensing images of landslide areas are cropped into sub-images of a predefined size, which serves as the standard input size for the model (Figure 2c), since object detection models cannot process entire images at once [42,43]. These sub-images are often referred to as “slices” in the context of object detection. Each landslide corresponds to a slice, except for extremely large landslides. Each slice is designed to contain as much of the landslide as possible, enhancing the contrast between the landslide and the background, thereby enabling the algorithm to learn the overall features of landslides. If a landslide exceeds 1280 m in length or width, it cannot be fully contained within a single slice and must be divided into two or more sub-images with a 50% overlap to mitigate boundary truncation effects. Some data augmentation techniques, such as adding background slices and applying rotation, are necessary to increase the number of slices. Landslide-free areas, accounting for 10% of the total number of slices, are selected as background slices. Their images should also be cropped to the same size for consistency. Then, all slices are rotated by 90°, 180° and 270° effectively, which is used to expand the number of slices (Figure 2d). The sliding direction of landslides exhibits significant randomness in remote sensing imagery, primarily trending toward the river in the study areas. By rotating the landslide slices, both the number and diversity of slices can be increased. Finally, landslide slices and background slices are combined into image files for further analysis.

Figure 2.

Production of the dataset: The dataset consists of two parts: (a) the training dataset and (b) the detecting dataset. The training dataset is generated through (c) cropping satellite imagery, (d) rotating images within the training area, and (e) labeling landslide locations. The detecting dataset is created by (f) cropping satellite imagery in the detecting area.

The landslide marker files consist of a series of text files. To generate these files, we utilize an automated data labeling tool (Annotation Tools in the ArcGIS Pro Deep Learning Toolbox) to create a landslide annotation file in a specified format for each slide. The annotation data is recorded within these text files, where each slice corresponds to a separate text file, except for background slices. Each row in a text file represents a single bounding box for a landslide. The number of rows in an annotation file corresponds to the total number of landslide bounding boxes within the slice. Each row comprises five columns: category code, x′, y′, w′, and h′. x′ and y′ represent the coordinates of the center point of the detection box (point B in Figure 2e) relative to the upper-left corner of the slice (point A in Figure 2e). Specifically, x′ is the ratio of the horizontal distance from the center of the detection box to the upper-left corner of the slice to the slice width (w), while y′ is the ratio of the vertical distance from the center of the detection box to the upper-left corner of the slice to the slice height (h). w′ and h′ characterize the width and height of the detection box. w′ represents the ratio of the detection box width to the slice width (w), and h′ represents the ratio of the detection box height to the slice height ().

2.1.2. Detecting Dataset

The detecting dataset consists of image files and image information files (Figure 2b). Its construction process is fundamentally different from that of the training dataset. Unlike the training dataset, which must include landslide information, the detecting dataset contains no prior information about landslides. The only requirement for generating the detecting dataset is to divide the remote sensing imagery of the detecting area into uniformly sized slices, with dimensions identical to those used in the training dataset (Figure 2f). These slices collectively form the detecting dataset. During the tiling process, it is also necessary to record key information about each slice—such as its width, height, resolution, and the real-world coordinates of its upper-left corner. This information is essential for converting the model’s output into georeferenced results with actual spatial locations. The file that stores this information is commonly formatted using the ArcView World Coordinates with the file extension “.TWF”. Each image slice requires a corresponding file to store its information.

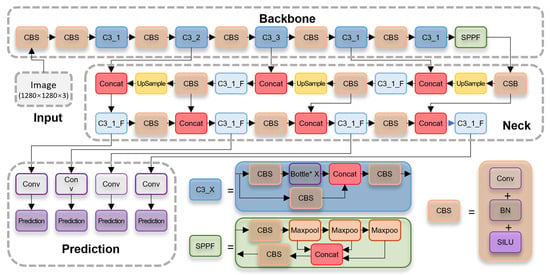

2.2. YOLOv5

The YOLO (You Only Look Once) series model has shown superior performance in various landslide identification studies [54,55]. For the detecting old landslides, it is crucial to employ a model capable of capturing extensive landslide features while preserving detailed information. This necessitates maximizing the input image size while maintaining a constant resolution. In this study, we utilized the YOLOv5 [56] with the largest input image size of 1280 × 1280 pixels. The 1280 × 1280 input size allows the model to capture the complete morphological structure of an old landslide while maintaining high-resolution spatial information, thereby improving detection accuracy and boundary recognition. The YOLOv5 code was sourced from GitHub (https://github.com/ultralytics/yolov5, accessed on 15 November 2021). Figure 3 illustrates the network structure of YOLOv5 used in this study, which consists of four main components: Input, Backbone, Neck, and Prediction. Each component consists of fundamental modules serving specific functions: (1) Input: Manages image input and preprocessing tasks, including data augmentation and automatic image size adjustment; (2) Backbone: Responsible for feature extraction, Constructed by stacking several CBS modules (each composed of a Convolutional Layer (Conv2d), Batch Normalization Layer (BN), and SILU activation function (SILU)), C3_x modules (each comprising three CBSs and ‘x’ number of Bottleneck blocks), and a Spatial Pyramid Pooling-Fast (SPPF) module; (3) Neck: Enhances feature fusion to effectively utilize features extracted by the backbone network, employing modules such as Concat, C3_x_F, Upsample, and CBS; (4) Prediction: Utilizes Conv2d layers for classification and optimization of the detection box.

Figure 3.

The network structure of YOLOv5 used in this study. The model consists of four main components: Input (image preprocessing), Backbone (feature extraction), Neck (feature fusion), and Prediction (classification and bounding box regression). Key modules such as CBS, C3_x, and SPPF enhance detection performance.

2.3. Cross-Regional Detection and Spatial Localization of Old Landslides

2.3.1. Cross-Regional Detection

The set of weight parameters that achieves the best performance on the training dataset is adopted as the final model for old landslide detection. Once the model is finalized, the image files from the detecting dataset are fed into the trained detection model to identify potential old landslides. As output, the model generates a series of landslide marker files, each corresponding to a detected landslide feature. These marker files share the same format as those used in the training dataset—plain text files containing relative positional information. The number of marker files produced is equal to the number of old landslide features detected. Each marker file specifies the relative position of a detected old landslide within its corresponding image slice.

2.3.2. GIS Localization

Spatial location is a basic property of landslide inventories and is one of the key pieces of information that must be obtained from landslide detection analyses. However, object detection methods in the field of computer vision do not prioritize geographic coordinates, nor do landslide identification studies based on these methods emphasize the precise spatial location of landslides [29,52]. The output of the YOLO algorithm also lacks accurate spatial coordinates; so, post-processing is necessary to determine the spatial position of landslides.

Based on the position of each image slice and the relative location of the detected landslide within it, the precise spatial coordinates of each landslide can be determined. First, the image information file of the detecting dataset is read using Python 3.6.8 to extract key information for each slice, including its width, height, resolution, and the coordinates of the upper-left corner. Similarly, the detection results are read to obtain the relative positions of the detected old landslides within their corresponding slices. Then, using Equation (1), the coordinates of the bounding box vertices are calculated, enabling accurate geolocation of the detection results. Finally, the ArcPy module in ArcGIS 10.4 is used to convert the vertex coordinates into a shapefile with geographic coordinates. Each vertex is assigned an identifier indicating which bounding box it belongs to. The vertices of each bounding box are then connected to form polygons, resulting in the final detection box with precise spatial positioning.

where a, b, c, and d represent the four vertices of the detection box (Figure 2e), and their actual coordinates are inside (); x and y denote the actual coordinates of the upper-left corner of the image; w and h denote the width and height of the image, with a value of 1280 pixels in this paper; r stands for the ground resolution of the image, which is set to 1.0 m in this paper. x, y, w, h, and r are saved during the cropping process and recorded in the ArcView World Coordinates with the file extension “.TWF”. x′, y′, w′, and h′ are used to represent the center coordinates and the width and height of the detecting box. Please note that the parameters used in this step do not have explicit physical units. The length units may be either meters or degrees, depending on the coordinate system of the original data. This does not affect the localization results, as the coordinates obtained by this method are fully consistent with the original data’s spatial reference. If the original data use a projected coordinate system, all length units are expressed in meters. In this study, the coordinate system is the Chinese Geodetic Coordinate System (CGCS2000) with Gauss–Krüger projection.

2.4. Evaluation of Detection Accuracy

The model’s performance was evaluated in a detecting area independent of the training region. After spatial localization, the detection results were compared with mapped landslide boundaries in a GIS environment. Because old landslides often show blurred geomorphic features, a detection was considered valid when its bounding box overlapped more than 50% of a mapped landslide (IoU > 0.5); otherwise, it was regarded as invalid. Model accuracy was assessed using precision, recall, and F1-score, which measure the proportions of correct, missed, and false detections. Given the large size and indistinct boundaries of old landslides, multiple boxes may correspond to one landslide. Accordingly, precision (P) is defined as the ratio of valid boxes to all detections, recall (R) as the ratio of detected to total landslides, and F1 as their harmonic mean, balancing omission and commission errors.

where VB is the number of the valid boxes; IB is the number of the invalid boxes; DL is the number of the detected landslides; UL is the number of the undetected landslides.

3. Study Areas and Data Sources

3.1. Training and Detecting Areas in the TGRA

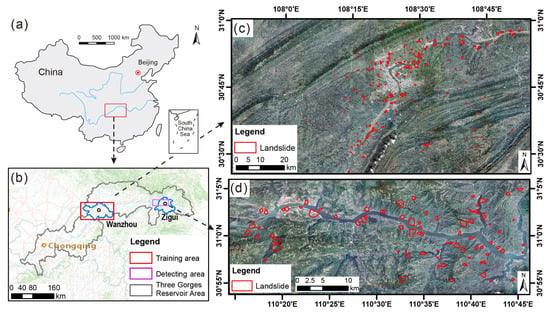

In order to effectively demonstrate the usability and practical applicability of the proposed method, two areas within the Three Gorges Reservoir Area (TGRA) in China were selected for cross-regional landslide detection: Wanzhou District in Chongqing Municipality and Zigui County in Hubei Province, as shown in Figure 4. A large number of old landslides are developed in Wanzhou District and Zigui County [57,58]. The two areas are clearly separated into a training area and a detecting area, which can be used for a variety of applications. The training area encompasses the entire Wanzhou District, with coordinates ranging from 107°48′54″E to 108°55′8″E and 30°20′N to 31°0′7″N, covering an area of approximately 7.3 × 103 km2. The detecting area is located near Zigui County, with coordinates ranging from 110°15′32″E to 110°47′17″E and 30°53′38″N to 31°6′50″N, covering an area of approximately 1.3 × 103 km2. These two study areas are located 130 km apart from each other. The geomorphology of the study areas was shaped by significant tectonic events, specifically the Yanshan orogeny during the late Jurassic period, which created the topographic skeleton of the mountains. Over time, the Yangtze River eroded and incised the area, resulting in the current moderate-to-low altitude mountain and river valley landscapes [59,60,61]. The surface materials consist primarily of sedimentary strata and their weathering deposits, mainly sandstone, mudstone, limestone, and sandstone interbedded with mudstone layers.

Figure 4.

Map of the two study areas. (a) Location of Three Gorges Reservoir Area, (b) Location of the two study areas, (c) Landslide inventory map of training area in Wanzhou District, and (d) Landslide inventory map of detecting area in Zigui County.

The geological environment of the TGRA is intricate and fragile, particularly in the Wanzhou and Zigui regions, where unfavorable geological conditions prevail. These areas are recognized as having a high susceptibility to landslides [62,63]. Additionally, reservoir operations and human migration have triggered the reactivation of more than 670 old landslides in the TGRA [64], including notable cases like the Huangtupo landslide [65], Shuping landslide [66], Baishuihe landslide [67], Liangshuijing landslide [68], and so on. Managing these old landslides is extremely challenging due to their typically large and deep-seated characteristics. For example, the Kangjiapo landslide, an old landslide in the Three Gorges Reservoir area, has undergone treatment twice and continues to experience deformation. The combination of precipitation and reservoir water level fluctuations significantly increases the risk of these landslides causing further damage. It is a matter of significant concern that numerous old landslides remain undiscovered, particularly in mountainous regions where the scarcity of flat land has led to the establishment of many settlements atop these unstable sites. Detecting old landslide areas is crucial for mitigating landslide risk in the TGRA.

3.2. Data Sources

3.2.1. Remote Sensing Imagery

For this study, optical remote sensing imagery of the study areas was obtained from Google Earth, with a spatial resolution of 1 m/pi × 1 m/pi. Most images were acquired between 2017 and 2020, primarily during the dry season to minimize the effects of vegetation and illumination differences. Landslide data—mainly the mapped boundaries—were provided by the Chongqing Institute of Geological Environment Monitoring. For the old landslides used in this study, comprehensive field verification was conducted in Wanzhou District, while in Zigui County, all landslides were verified using remote sensing interpretation, with a subset further validated through field investigation. Two datasets were constructed from these data: a training dataset and a detecting dataset. Each image tile has a size of 1280 × 1280 pixels, corresponding to an actual ground coverage of 1280 × 1280 m.

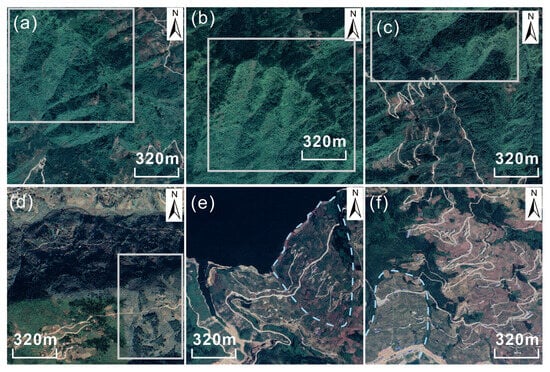

The study areas have experienced geological processes and human activities that have made many landslides indistinguishable by remote sensing images. Figure 5 shows some remote sensing image of landsides in the study areas. It illustrates that the morphological characteristics of old landslides have been changed by some factors. In comparison with new landslides, the color, tone, texture and shadow characteristics of old landslides appear more blurred in remote sensing images, making them more difficult to distinguish from the surrounding environments.

Figure 5.

Image comparison of old landslides and new landslides in the study areas.

3.2.2. Landslide Inventory

A total of 305 old landslides were identified in Wanzhou District and Zigui County through data collection and field surveys. These landslides share similar geomorphic settings and morphological characteristics. Among them, 223 old landslides located in Wanzhou District were used for training the detection model (Figure 4c). As shown in Table 1, landslides in the training area are generally large in scale, with an average area of 1.25 × 105 m2 and an average length of 330 m. To evaluate the model’s performance, 82 known old landslides in Zigui County (Figure 4d) were used for validation by comparing them with the model’s detection results. Landslides in the detecting area are also large, with an average area of 3.28 × 105 m2 and an average length of 620 m. Across both regions, the largest landslide reaches an area of 1.64 × 106 m2 and a length of 1610 m, while even the smallest landslides exceed 1000 m2.

Table 1.

Landslide statistics in the study areas.

In summary, old landslides in the study areas are generally large in scale. However, only eight landslides (2.6% of the total) have lengths exceeding 1280 m, meaning that 97.4% of the landslides can be fully contained within a single image slice. This is favorable for the effective extraction of landslide features during detection. The training dataset was constructed using remote sensing imagery and mapped landslide boundaries of the 223 landslides in Wanzhou. For the detecting dataset, the remote sensing imagery of Zigui was uniformly divided into 946 slices, each measuring 1280 × 1280 m. This process treated the detecting area as a blind zone, without incorporating any prior landslide information—known landslides in the detecting area were used for result evaluation.

4. Results

4.1. Training Results

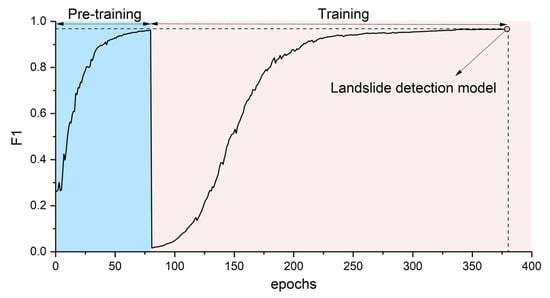

All experiments were conducted on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3080 Ti GPU (12 GB VRAM), Intel i9 CPU, and 64 GB RAM, running Ubuntu 20.04 with CUDA 11.3. Firstly, an open-source object detecting dataset [69] was inputted to the YOLOv5 algorithm, which has a pre-training of 80 epochs. Then, the training dataset was inputted to the algorithm that has undergone pre-training to train the detection model. The minimum batch size is 8 images, the number of training epochs is 300, and other parameters are kept as default. Figure 6 illustrates that the F1 value of the validation set, which constitutes 20% of the total images automatically divided for model evaluation, reached the maximum value of 0.96 after 300 training epochs. Therefore, the weighting parameters from the final epoch were selected as the optimal model for landslide detection in the detecting area.

Figure 6.

Validation set accuracy.

4.2. Detection and Localization Results

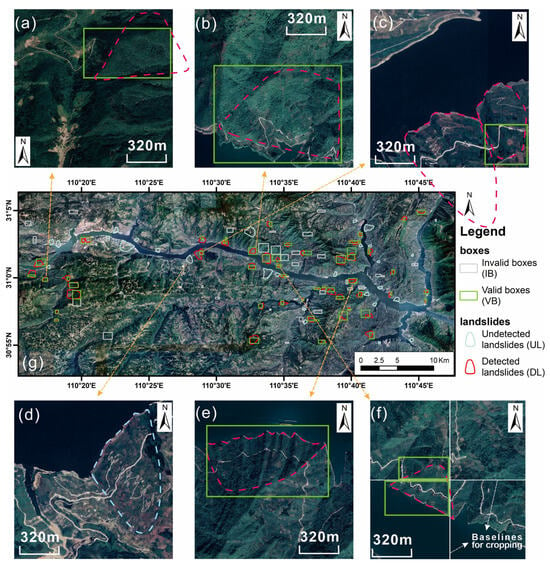

4.2.1. Localization and Visualization of Detection Results

The detecting dataset is sequentially put into the trained landslide detection model to obtain landslide detection results without actual geographic location, some of which are shown in Figure 7a–f. To accurately represent the spatial location of landslides, a Python-based coordinate conversion script was used to transform the detection boxes into shapefiles with actual geographic coordinates. The script comprises two main components: the first calculates the precise coordinates of each detection box vertex using predefined Equation (1), while the second utilizes ArcPy module developed in ArcGIS 10.4 to convert coordinate text into shapefiles. By adding the detection box shapefile to the landslide map in GIS, the location relationship between the detection boxes and the landslide boundaries can be displayed.

Figure 7.

Landslide detection results: (a–f) different types of detection outcomes and (g) the spatial distribution of detected landslides. (a) Local Bounding Box, (b) and (e) Full Bounding Boxes, (c) Multiple Local Bounding Box, (d) an undetected landslide, and (f) a landslide detected by multiple bounding boxes.

By overlaying the vectorized detection boxes and mapped landslide boundaries onto the remote sensing imagery in ArcGIS 10.4, the spatial relationship between the detection results and the actual landslide locations can be visualized, as shown in Figure 7g. The results show that the landslide detection model tends to mark areas with large variations in tones, shadows, and textures in remote sensing images as landslides, especially when these variations are presented as closed blocks or cirque. As in Figure 7a, the model detects an area with a dark shade boundary. The dark shade boundary is uniform in tone both inside and outside showing dark green and it is black. In addition, the landslide detection model also focuses on small gullies, fractures, ridges, river boundaries or local uplifts and other topographic abrupt changes where they are also the areas with large changes in remote sensing image features. Figure 7a–f all have different degrees of variation in remote sensing image at the boundary of the detection boxes and they correspond to certain landform types. The dark shade boundary in Figure 7a are ridges, which is realized as transverse ridges, minor and main scarps of the landslide. The small gullies or crevices and the Yangtze River boundary on both sides of Figure 7b,e,f form a closed cirque-like shape. In conclusion, the majority of detection boxes are distributed on both sides of the Yangtze River and its gullies, and a few of them are located far from the Yangtze River.

4.2.2. Types of Detection Boxes

The positional relationship between landslides and detection boxes is analyzed, categorizing all possible detection outcomes in the detecting area into five types (Table 2). Local Bounding Boxes mean that a box detects a local feature of a landslide. Local features, such as steep minor or main scarps, are identified by the detector. Full Bounding Boxes mean that a box detects a complete landslide. The landslide areas exhibit significantly different from the surrounding environment, and the model can detect the whole landslide. Multiple Local Bounding Boxes mean that multiple boxes (more than one) detect multiple local features of a landslide. The landslide has many distinct features that are not adjacent to each other and they are detected separately by the detector. Multi-landslide Bounding Boxes mean that a box detects several adjacent landslides. The two landslides are so close that they share transverse ridges. Non-landslide Bounding Boxes mean that the model either labels non-landslide areas as landslides or misses the actual landslides (Table 2).

Table 2.

Al types of the detection results.

If the same landslide is detected by multiple bounding boxes, all of these boxes are regarded as correct provided that each overlap with the landslide by more than 50% of its area (i.e., IoU > 0.5). In this case, the number of valid boxes (VB) increases accordingly. However, since these boxes collectively identify a single landslide, the number of detected landslides (DL) increases by only one. As shown in Table 2, Local Bounding Boxes and Full Bounding Boxes indicate that one detection box detected a landslide; so, both VB and DL increase 1. Multiple Local Bounding Boxes indicate that two detection boxes identify a single landslide; so, VB increases by 2, while DL increases by 1. Multi-landslide Bounding Boxes indicate that one detection box detected two landslides; so, VB increases by 1, while DL increases by 2. If the detection results are Non-landslide Bounding Boxes, neither VB nor DL increases.

4.2.3. Detection Performance on the Detecting Area

After counting, the number of different types of detection boxes is shown in Table 3. A total of 93 detection boxes were obtained, which are classified into different categories, as shown in Table 2. Of these, there are 53 valid detection boxes and 41 invalid detection boxes. Among the valid boxes, the number of Local Bounding Boxes is 27, the largest number, accounting for 55.2% of the total valid boxes. Multiple Local Bounding Boxes and Multi-landslide Bounding Boxes are rare in the detecting area, with 6 detection boxes each. 14 detection boxes detected the whole landscape of the landslides, which accounted for 14.89% of the total number of boxes. In total, 55 landslides were detected in the detecting area and 28 landslides were missed. Consequently, precision (P) is calculated as 0.564, recall (R) as 0.671, and the F1 score as 0.62.

Table 3.

Statistics for different types of detection boxes.

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of Detection Patterns

To better understand the model’s detection behavior, we analyzed the spatial characteristics and types of generated bounding boxes. Among the valid detections, only 14 were classified as Full Bounding Boxes, capturing complete landslide extents and accounting for 32.6% of all valid results. Most boxes corresponded to localized geomorphic features, indicating that the model primarily recognizes partial morphological traits rather than entire landslide bodies. This behavior can be explained by two factors. First, old landslides have undergone long-term geomorphic evolution, which erodes or obscures their original boundaries—leaving only partial features such as main scarps, bulging toes, or concave slopes visible in imagery. Second, the detecting area represents a true “blind zone,” where the absence of prior labels and the image-slicing process often divide a single landslide into multiple tiles. This fragmentation leads to multiple detections of the same feature and limits the model’s ability to reconstruct complete boundaries. Overall, the model exhibits a localized detection tendency, which has both advantages and constraints. It enhances sensitivity to characteristic terrain elements, making it useful for preliminary screening, but it also restricts large-scale spatial completeness necessary for detailed inventory mapping.

Figure 8 illustrates typical false detections (Figure 8a–d) and missed landslides (Figure 8e,f). Two principal error sources were identified: (1) geomorphic confusion in rugged terrain such as ridges, gullies, or slope transitions, and (2) tonal or textural heterogeneity that mimics landslide signatures. Although treated as false positives, some of these detections may represent previously unrecorded old landslides, thus offering valuable leads for future validation. Most missed landslides occur in areas extensively modified by engineering, agriculture, or urbanization, where anthropogenic alteration obscures natural geomorphic evidence. These areas often coincide with densely populated zones, underscoring the need for enhanced monitoring and field verification.

Figure 8.

Image slices of invalid detection boxes and missed landslides. (a–d) Invalid landslide detection boxes. (e,f) Undetected landslides.

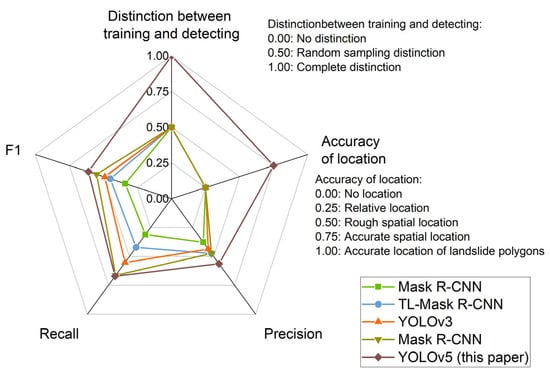

5.2. Comparison Analysis with Previous Studies

While deep learning–based landslide detection has advanced rapidly, research explicitly targeting old landslides remains limited. Compared with previous optical-image studies [38,70], the present model achieves substantially improved cross-regional generalization. As shown in Figure 9, existing approaches such as Mask R-CNN, TL-Mask R-CNN, and YOLOv3 typically achieved F1 ≈ 0.5 under same-region validation, which likely overestimates true performance. In contrast, our YOLOv5 model achieved F1 = 0.62 under strict spatial separation—while maintaining high precision and recall—demonstrating stronger transferability to previously unseen terrain.

Figure 9.

Comparison of performance of old landslide detection based on optical remote sensing. (The results of old landslide detection came from the works conducted by Jiang et al. [38]. and Ju et al. [70].).

A further distinction lies in spatial localization accuracy. Prior studies often reported only relative or pixel-level positions without geographic coordinates [43,44]. Our workflow integrates a Python-based georeferencing module that records slice metadata (resolution, origin coordinates) and converts detections into shapefiles with real-world coordinates (Figure 10). The resulting GIS-ready products enable direct integration into hazard inventories, zoning, and risk-management systems—bridging the gap between research and operational application.

Figure 10.

Comparison of methods: (a) a summary of the methods in other papers; (b) the method proposed in this paper.

5.3. Practical Implications

The proposed workflow offers strong practical value due to its efficiency, simplicity, and GIS compatibility.

- (1)

- Computational efficiency: model training (24.8 h) is the most time-intensive step, whereas cross-regional detection completes in about 5 min, enabling large-scale regional screening.

- (2)

- GIS integration: shapefile outputs with embedded geographic coordinates can be directly visualized in ArcGIS or QGIS for hazard mapping, land-use planning, or risk assessment.

- (3)

- Realistic transferability: strict spatial separation between training and detection areas simulates real-world conditions in which labeled data are unavailable in the target region. This design highlights the model’s generalization capability and adaptability to new geographic contexts.

5.4. Research Limitations

Although the proposed method demonstrates strong performance in detecting old landslides, particularly in terms of spatial localization, several limitations should be acknowledged to guide future improvements.

- (1)

- Dependence on preserved visual features: The model performs best for old landslides that retain clear and recognizable geomorphic signatures, such as scarps, bulges, and concave slope geometries. In contrast, landslides whose surfaces have been significantly modified or obscured by vegetation recovery, erosion, or human activities (e.g., construction) are more difficult to detect using optical imagery alone. Integrating auxiliary information, such as DEM-derived terrain attributes (e.g., slope and curvature) and geological data, could help alleviate this limitation and improve detection performance in visually degraded areas.

- (2)

- Focus on detection and localization, not activity assessment: The current framework identifies and localizes old landslides but cannot evaluate their activity state. The detected features primarily represent preserved geomorphic signatures of past landslide events, and their current kinematic state (active or stable) cannot be determined using single-date optical imagery alone. Future work should integrate multi-temporal optical images or InSAR time-series data to detect reactivation and slow deformation.

- (3)

- Cross-regional performance degradation: The notable decrease in F1 score from 0.96 in the training area to 0.62 in the detecting area highlights the inherent challenges of cross-regional domain transfer. This performance degradation can be mainly attributed to three factors. First, differences in geomorphological settings and illumination conditions between the training and detecting areas lead to variations in surface texture, landslide morphology, and spectral–textural patterns, which reduces feature consistency across regions. Second, the limited diversity of training samples restricts the model’s ability to generalize to heterogeneous terrains with distinct geomorphic characteristics. Third, some detected landslide-like features may correspond to previously unmapped old landslides, which are counted as false positives due to the absence of ground-truth labels, rather than representing true model misdetections.

6. Conclusions

This study enhances the detection and localization of old landslides by integrating one-meter-resolution optical imagery with an advanced YOLOv5 model using larger input images. The spatial precision of the results was further improved by converting detection outputs into GIS-compatible shapefiles containing geographic coordinates. The strict separation between training and detecting areas closely simulates real-world cross-regional detection scenarios, substantially improving the method’s practical usability compared with previous approaches.

- (1)

- Detecting the complete boundaries of old landslides remains challenging due to blurred geomorphic features; the model primarily captures their local morphological characteristics.

- (2)

- The proposed model achieved an F1 score of 0.96 in the training area and successfully identified 90 old landslides in the detecting area, including 60 previously mapped and several newly recognized ones, demonstrating transferability to unsurveyed “blind zones”.

- (3)

- This study introduces a position conversion method that transforms YOLOv5 detection outputs into georeferenced coordinates, significantly enhancing the practical application value of image-based landslide detection.

Author Contributions

X.X. contributed to data curation, investigation, methodology and writing—original draft. D.L. contributed to methodology, writing—review and editing, and funding acquisition. X.L. contributed to writing—review and editing, data curation, visualization. Q.C. contributed to formal analysis and writing—original draft. K.Y. contributed to writing—review and editing, and supervision. F.M. contributed to project administration and validation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the project “Geological Disasters Quantitative Hazard Prediction and Dynamic Risk Evaluation of on Random Slopes”, which is financed by the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2023YFC3007203). Additional support was provided by the postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (GZC20250295).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during this study are publicly available on Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15578864. The datasets include the delineated boundaries of old landslides in Wanzhou District and Zigui County, as well as the Python scripts used for georeferencing YOLOv5 detection results.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Wanzhou Geo-Environmental Inspection Station and the Chongqing Institute of Geological Environment Monitoring for providing the landslide data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Varnes, D. Landslide Types and Processes. Landslides Eng. Pract. 1958, 24, 20–47. [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Eeckhaut, M.; Poesen, J.; Govers, G.; Verstraeten, G.; Demoulin, A. Characteristics of the size distribution of recent and historical landslides in a populated hilly region. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2007, 256, 588–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, S.; Siddle, H. Landslide research in the South Wales Coalfield. Eng. Geol. 1996, 43, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ren, S.; Liu, X.; Guo, C.; Li, J.; Bi, J.; Ran, L. Reactivation mechanism of old landslide triggered by coupling of fault creep and water infiltration: A case study from the east Tibetan Plateau. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2023, 82, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ost, L.; Van Den Eeckhaut, M.; Poesen, J.; Vanmaercke-Gottigny, M. Characteristics and spatial distribution of large landslides in the Flemish Ardennes (Belgium). Z. Geomorphol. 2003, 47, 329–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronchetti, F.; Borgatti, L.; Corsini, A.C.; Cervi, F. Hydro-mechanical features of landslide reactivation in weak clayey rock masses. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2010, 69, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Xu, Q.; Yang, H.; Li, S.; Iqbal, J.; Fu, X.; Huang, X.; Cheng, W. Activity law and hydraulics mechanism of landslides with different sliding surface and permeability in the Three Gorges Reservoir Area, China. Eng. Geol. 2019, 260, 105212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veveakis, E.; Vardoulakis, I.; Toro, G. Thermoporomechanics of creeping landslides: The 1963 Vaiont slide, northern Italy. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2007, 112, F03026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykes, A.; Bromhead, E. New, simplified and improved interpretation of the Vaiont landslide mechanics. Landslides 2018, 15, 2001–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancox, G. The 1979 Abbotsford Landslide, Dunedin, New Zealand: A retrospective look at its nature and causes. Landslides 2008, 5, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Li, D.; Miao, F.; Yan, L.; Leo, C.; Sun, Y. The Kangjiapo landslide in Wanzhou District, Chongqing City: Reactivation of a deep-seated colluvial landslide in the Three Gorges Reservoir. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2023, 82, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzetti, F.; Carrara, A.; Cardinali, M.; Reichenbach, P. Landslide hazard evaluation: A review of current techniques and their application in a multi-scale study, Central Italy. Geomorphology 1999, 31, 181–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fell, R.; Corominas, J.; Bonnard, C.; Cascini, L.; Leroi, E.; Savage, W. Guidelines for landslide susceptibility, hazard and risk zoning for land use planning. Eng. Geol. 2008, 102, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichenbach, P.; Rossi, M.; Malamud, B.D.; Mihir, M.; Guzzetti, F. A review of statistically based landslide susceptibility models. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2018, 180, 60–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casagli, N.; Cigna, F.; Bianchini, S.; Hölbling, D.; Füreder, P.; Righini, G.; Del Conte, S.; Friedl, B.; Schneiderbauer, S.; Iasio, C.; et al. Landslide mapping and monitoring using radar and optical remote sensing: Examples from the EC-FP7 project SAFER. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2016, 4, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Lu, Z. Remote sensing of landslides—A review. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Wang, F.; Xu, Q.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, F.; Li, W.; Dong, X.; Yang, J.; Guo, D.; He, W. Identification, distribution, and mechanisms of large landslides in the upper reaches of the Jinsha River. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2025, 84, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C. Preparation of earthquake-triggered landslide inventory maps using remote sensing and GIS technologies: Principles and case studies. Geosci. Front. 2015, 6, 825–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Feng, G.; Zhao, Y.; Xiong, Z.; He, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.; An, Q. A deep-learning-based algorithm for landslide detection over wide areas using InSAR images considering topographic features. Sensors 2024, 24, 4583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, T.; Wu, L.; Hayakawa, Y.S.; Yin, K.; Gui, L.; Jin, B.; Guo, Z.; Peduto, D. Advanced integration of ensemble learning and MT-InSAR for enhanced slow-moving landslide susceptibility zoning. Eng. Geol. 2024, 331, 107436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Liu, Y.; Gao, P.; Chen, W.; Li, H.; Hou, Y.; Nuremanguli, T.; Ma, H. Landslide mapping with remote sensing: Challenges and opportunities. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2020, 41, 1555–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, A.; Singh, A.K.; Kumar, B.; Dwivedi, R. Review on remote sensing methods for landslide detection using machine and deep learning. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 2021, 32, e3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, T.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, Z.; Li, S.; Liu, S.; Nandi, A. Landslide inventory mapping from bitemporal images using deep convolutional neural networks. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2019, 16, 982–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanzadeh, O.; Shahabi, H.; Crivellari, A.; Homayouni, S.; Blaschke, T.; Ghamisi, P. Landslide detection using deep learning and object-based image analysis. Landslides 2022, 19, 929–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Li, S.; Bi, X.; Qiao, H.; Duan, Z.; Sun, Y.; Guo, J.; Li, X. Automatic landslide identification by dual graph convolutional network and GoogLeNet model: A case study for Xinjiang Province, China. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1248340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voulodimos, A.; Doulamis, N.; Doulamis, A.; Protopapadakis, E. Deep learning for computer vision: A brief review. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2018, 2018, 7068349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Oerlemans, A.; Lao, S.; Wu, S.; Lew, M. Deep learning for visual understanding: A review. Neurocomputing 2016, 187, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaioni, M.; Longoni, L.; Melillo, V.; Papini, M. Remote sensing for landslide investigations: An overview of recent achievements and perspectives. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 9600–9652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casagli, N.; Intrieri, E.; Tofani, V.; Gigli, G.; Raspini, F. Landslide detection, monitoring and prediction with remote-sensing techniques. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novellino, A.; Pennington, C.; Leeming, K.; Taylor, S.; Alvarez, I.; McAllister, E.; Arnhardt, C.; Winson, A. Mapping landslides from space: A review. Landslides 2024, 21, 1041–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Eeckhaut, M.; Poesen, J.; Verstraeten, G.; Vanacker, V.; Moeyersons, J.; Nyssen, J.; van Beek, L. The effectiveness of hillshade maps and expert knowledge in mapping old deep-seated landslides. Geomorphology 2005, 67, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, S.; Tong, L.; Guo, Z. A comprehensive remote sensing identification model for ancient landslides in the Dadu River Basin on the eastern margin of the Tibet Plateau. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1268826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhao, B.; Dai, K.; Dong, X.; Li, W.; Zhu, X.; Yang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Wang, X.; Huang, J.; et al. Remote sensing for landslide investigations: A progress report from China. Eng. Geol. 2023, 321, 107156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Xi, J.; Li, Z.; Ge, D.; Guo, Z.; Yu, J.; Wu, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, J. Optimal and multi-view strategic hybrid deep learning for old landslide detection in the Loess Plateau, Northwest China. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Eeckhaut, M.; Poesen, J.; Verstraeten, G.; Vanacker, V.; Nyssen, J.; Moeyersons, J.; van Beek, L.; Vandekerckhove, L. Use of LiDAR-derived images for mapping old landslides under forest. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2006, 32, 754–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo-García, F.; Alcántara-Ayala, I.; Ardizzone, F.; Cardinali, M.; Fiorucci, F.; Guzzetti, F. Satellite stereoscopic pair images of very high resolution: A step forward for the development of landslide inventories. Landslides 2015, 12, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudý, F.; Slámová, M.; Tomaštík, J.; Prokešová, R.; Mokroš, M. Identification of micro-scale landforms of landslides using precise digital elevation models. Geosciences 2019, 9, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Xi, J.; Li, Z.; Zang, M.; Chen, B.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Z.; Gao, S.; Zhu, W. Deep learning for landslide detection and segmentation in high-resolution optical images along the Sichuan–Tibet Transportation Corridor. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Peng, Y.; Lu, Z.; Li, W.; Yu, J.; Ge, D.; Xiang, W. Feature-fusion segmentation network for landslide detection using high-resolution remote sensing images and digital elevation model data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandric, I.; Chitu, Z.; Ilinca, I.; Irimia, R. Using high-resolution UAV imagery and artificial intelligence to detect and map landslide cracks automatically. Landslides 2024, 21, 2535–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Qi, W.; Xu, C.; Shao, X. Exploring deep learning for landslide mapping: A comprehensive review. China Geol. 2024, 7, 330–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ouyang, C.; Xu, Q.; Wang, D.; Zhao, B.; Luo, Y. CAS landslide dataset: A large-scale and multisensor dataset for deep learning-based landslide detection. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, G.; Guo, L.; Zhao, T.; Han, J.; Li, H.; Fang, J. Automatic landslide detection from remote-sensing imagery using a scene classification method based on BoVW and pLSA. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2013, 34, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, B.; Chen, G.; Pan, L.; Kou, R.; Wang, L. GAN-based Siamese framework for landslide inventory mapping using bi-temporal optical remote sensing images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2021, 18, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Stumpf, A.; Kerle, N.; Casagli, N. Object-oriented change detection for landslide rapid mapping. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2011, 8, 701–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macciotta, R.; Hendry, M. Remote sensing applications for landslide monitoring and investigation in Western Canada. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantar, B.; Pradhan, B.; Naghibi, S.A.; Motevalli, A.; Mansor, S. Assessment of the effects of training data selection on landslide susceptibility mapping: A comparison between support vector machine (SVM), logistic regression (LR), and artificial neural networks (ANN). Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2018, 9, 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Chen, T.; Niu, R.; Plaza, A. Landslide detection mapping employing CNN, ResNet, and DenseNet in the Three Gorges Reservoir, China. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 11417–11428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Fang, Z.; Li, Y.; Fu, B. A novel DynaHead-YOLO neural network for the detection of landslides with variable proportions using remote sensing images. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 10, 1077153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.Y.; Li, C.D.; Yao, W.M. Landslide susceptibility assessment through TrAdaBoost transfer learning models using two landslide inventories. Catena 2023, 222, 106799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Qiu, H.; Wei, Y.; Huangfu, W.; Yang, D. A proposed method for landslide detection based on transfer learning and graph neural network. Geosci. Front. 2025, 16, 102171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amatya, P.; Kirschbaum, D.; Stanley, T.; Tanyas, H. Landslide mapping using object-based image analysis and open source tools. Eng. Geol. 2021, 282, 106000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.; Rosser, N.; Kincey, M.; Benjamin, J.; Oven, K.; Densmore, A.; Milledge, D.; Robinson, T.; Jordan, C.; Dijkstra, T. Satellite-based emergency mapping using optical imagery: Experience and reflections from the 2015 Nepal earthquakes. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 18, 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Li, J.; Duan, P.; Wang, M. A small attentional YOLO model for landslide detection from satellite remote sensing images. Landslides 2021, 18, 2751–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Liu, R.; Li, G.; Gou, J.; Lei, Y. Landslide detection methods based on deep learning in remote sensing images. In Proceedings of the 2022 29th International Conference on Geoinformatics, Beijing, China, 15–18 August 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Liu, M.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, X.; Huang, Y.; Jiang, X. Landslide detection based on improved YOLOv5 and satellite images. In Proceedings of the 2021 4th International Conference on Pattern Recognition and Artificial Intelligence (PRAI), Yibin, China, 20–22 August 2021; pp. 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Yin, K.; Huang, J.; Gui, L.; Wang, P. Landslide susceptibility mapping based on self-organizing-map network and extreme learning machine. Eng. Geol. 2017, 223, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Segoni, S.; Fan, W.; Yin, K.; Deng, L.; Xiao, T.; Barbadori, F.; Casagli, N. Integration of effective antecedent rainfall to improve the performance of rainfall thresholds for landslide early warning in Wanzhou District, China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 119, 105317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Wang, H.; Gao, Y.; Li, X. Real-time monitoring and early warning of landslides at relocated Wushan Town, the Three Gorges Reservoir, China. Landslides 2010, 7, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Yin, K.; Cao, Y.; Ahmed, B.; Li, Y.; Catani, F.; Pourghasemi, H.R. Landslide susceptibility modeling applying machine learning methods: A case study from Longju in the Three Gorges Reservoir area, China. Comput. Geosci. 2018, 112, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Liu, S.; Macciotta, R.; Du, J.; Jiang, J.; Liu, Q.; Yin, K.; Hu, J.; Zhang, H. Spatial heterogeneity in landslide response to a short-duration intense rainfall event on 12 July 2024 in Pengshui County, Chongqing, China. Landslides 2025, 22, 3935–3952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Fu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Tang, H.; Yan, J.; Gong, W.; Yao, W.; Criss, R. Susceptibility of reservoir-induced landslides and strategies for increasing slope stability in the Three Gorges Reservoir Area: Zigui Basin as an example. Eng. Geol. 2019, 261, 105279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Du, J.; Yin, K.; Macciotta, R.; Liu, S.; Jiang, J.; Yang, H. Slope-specific rainfall thresholds for regional landslide early warning systems. Eng. Geol. 2025, 355, 108249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Wasowski, J.; Juang, C.H. Geohazards in the Three Gorges Reservoir Area, China—Lessons learned from decades of research. Eng. Geol. 2019, 261, 105267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Zhu, Z.; Cui, Z.; Wang, X. Mass rock creep and landsliding on the Huangtupo slope in the reservoir area of the Three Gorges Project, Yangtze River, China. Eng. Geol. 2000, 58, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, G.; Sassa, K.; Takeuchi, A.; Araiba, K. Displacement monitoring and physical exploration on the Shuping landslide reactivated by impoundment of the Three Gorges Reservoir, China. In Landslides: Risk Analysis and Sustainable Disaster Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Yin, K.; Leo, C. Analysis of Baishuihe landslide influenced by the effects of reservoir water and rainfall. Environ. Earth Sci. 2010, 60, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xie, X.; Jin, B.; Chen, L.; Liang, X.; Yin, K. Comprehensive risk management of reservoir landslide–tsunami hazard chains: A case study of the Liangshuijing landslide in the Three Gorges Reservoir area. Landslides 2024, 22, 671–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Yu, D.; Shen, C.; Li, W.; Xu, Q. Landslide detection from an open satellite imagery and digital elevation model dataset using attention-boosted convolutional neural networks. Landslides 2020, 17, 1337–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.; Xu, Q.; Jin, S.; Li, W.; Su, Y.; Dong, X.; Guo, Q. Loess landslide detection using object detection algorithms in Northwest China. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.